Adenomatoid mesothelioma of the peritoneum (AMP) is a rare benign tumor originating from mesothelial cells.1 Most frequently, AMP occurs between 26 and 55 years of age, at a mean age of 41 years.1 In contrast to diffuse malignant mesothelioma, which has been linked to asbestos exposure, the etiology of AMP has not been established.2 Only a minority of patients have symptoms related to the tumor. AMP may present local recurrence, but it has no potential for malignant transformation.3 Although there are many case reports of abdominal mesotheliomas, to date, there have been no reports of MR imaging features of AMP. In this article, we present the MR imaging features of a case of AMP with histopathological correlation.

CASE REPORT

A 25-year-old woman presented with pelvic pain. The patient had had a cesarean section 3 years before her visit and an appendectomy about 6 months earlier than her onset. Routine ultrasound exam showed an expansive pelvic lesion suggesting an adnexal origin, most likely an ovarian neoplasm, and this finding was confirmed by two other ultrasound exams, each one performed at a different facility. A pelvic-abdominal MR exam was requested for lesion characterization. Laboratory tests were within normal values, except for CA125 of 37.9 μ/ml (normal range 0.0 to 35.0 μ/ml).

Imaging Findings

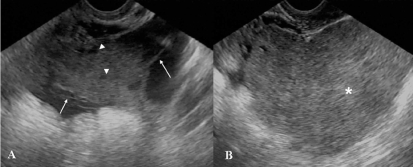

Transvaginal pelvic sonography showed a retrouterine adnexal mass extending towards the left parauterine region with a complex echotexture containing a homogeneous solid component about 5.0 cm in size and small cystic areas intermingled with linear septa. The mass measured 10.8 × 6.1 × 10.5 cm (volume of 359.7 cm3). Color Doppler imaging demonstrated vascularization of the solid area and of some septa in the cystic region, with a resistive index ranging from 0.60 to 0.70. Ovaries were identified in neither ultrasound exam. There was no sign of ascites (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transvaginal pelvic ultrasound images (A,B) showed a complex retrouterine mass with a homogeneous solid component (*, B) and cystic areas (arrowhead, A) intermingled with linear septa (arrow, A)

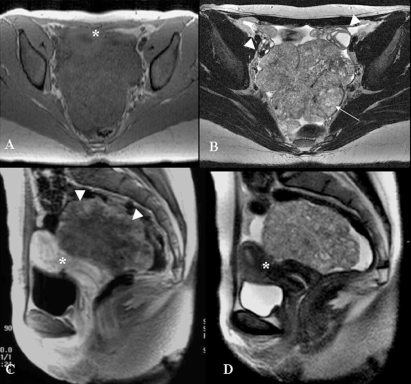

The MR images demonstrated a large, expansive, and well-delimited lesion with lobulated contours; T1-weighted images showed homogeneous signal intensity predominately with a low signal, whereas T2-weighted sequences were heterogeneous with small high intensity foci (Figure 2). There was a slightly heterogeneous enhancement in post-contrast T1-weighted images that was more evident peripherally (Figure 2). The lesion measured 9.2 × 7.2 × 8.0 cm and was located close to the ovaries, which were dislocated anterolaterally. The contours, dimensions and signal intensity of the ovaries were normal. The uterus was normal in shape, dimensions and signal intensity, and it was also dislocated anteriorly. A small amount of free fluid was present in the peritoneal cavity surrounding the lesion. The upper abdominal MR evaluation showed the extension of the free peritoneal fluid and normal anatomy of abdominal organs. Computed tomography of the pelvis without intravenous injection of contrast agent was performed to search for calcification and showed a low homogeneous coefficient of attenuation for the lesion, ranging from − 2 to +10 U.H, with no evidence of calcification (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Pelvic MR exam. Axial GRE T1-weighted (A), axial TSE 512 T2-weighted (B), sagittal post-contrast GRE T1-weighted image and (D) sagittal TSE T2-weighted images. There is a large, expansive, well-delimited lesion with lobulated contours; the T1-weighted sequence shows homogeneous signal intensity predominately with a low signal, and T2-weighted sequences are heterogeneous with small high-intensity foci (arrow). The lesion dislocated the ovaries (arrowheads, B) anterolaterally and the uterus (*, A,C and D) anteriorly. After intravenous injection of paramagnetic contrast agent, there was a heterogeneous enhancement of the lesion that was more evident peripherally (arrowheads, C)

Figure 3.

Computed tomography with no intravenous contrast agent revealed that there was no calcification within the mass (arrows)

Patient outcome

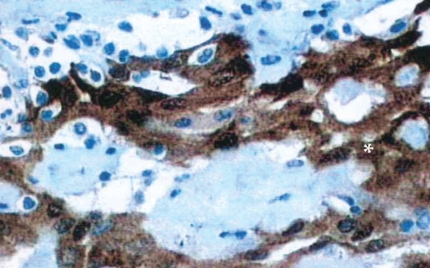

The patient was submitted to open abdominal surgical resection of the lesion, which had adherences to the rectal anterior wall but no invasion of the uterus or adnexa. Macroscopic anatomopathological examination revealed various irregular fragments of brownish, friable tissue that measured 15.0 × 12.0 × 4.0 cm and weighed 170.0 g. Microscopic analysis revealed a well-differentiated mesothelial neoplasia, which is detailed in Table 1. Immunohistochemistry evaluation was carried out in the histological sections with an immuno-peroxidase reaction via the avidin-biotin peroxidase method, with the primary antibodies calretinin + CEA- and BerEp4- (Figure 4).

Table 1.

Histopathological findings of the reported case

| Origin | Primitive |

| Histogenetic lineage | Mesothelial |

| Structural differentiation | Well-differentiated |

| Supporting tissue | Loose – vascularized |

| Predominant cell type | Medium size – Polygonal |

| Cell arrangement | Acinar – Tubular – Papilliform |

| Cytoplasm characteristics | Abundant – Microvacuolized – Basophilic |

| Nucleus characteristics | Medium volume – Round – Discrete nucleoli – Fine chromatin – Homogeneous chromatin |

| Nucleus/cytoplasm ratio | Maintained |

| Extracellular material produced | Absent |

| Mitotic index | Low (up to 1) |

| Degree of necrosis | Absent |

| Degree of atypy | Mild |

| Cytologic (nuclear) grade | 1 |

| Histological grade | I |

| Capsular limits | Absent |

| Tumor limits | Poorly defined |

| Vascularization | Abundant |

| Forms of infiltration | Absent |

| Inflammatory infiltrate | Present |

| Predominant cells | Lymphocytes – Histiocytes |

| Microcalcifications | Present – Focal |

| Desmoplasia | Absent |

| Hemorrhage | Absent |

| Vacuolar embolization | Not visualized |

| Lymphatic embolization | Not visualized |

| Perineural infiltration | Not visualized |

| Surgical safety margins | Poorly defined |

Figure 4.

The histopathologic section shows calretinin staining for well-differentiated mesothelial cells (*), which confirms the mesothelial origin of the tumor

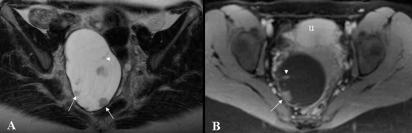

A follow-up MR exam revealed an expansive, predominantly cystic lesion with high protein content located in the posterior cul-de-sac; this lesion had shown a progressive increase in volume over 3 years and was characterized as a recurrent tumoral lesion (Figure 5). The lesion was resected surgically, and there was no sign of recurrent disease on subsequent follow-up exams. The patient is currently asymptomatic.

Figure 5.

Follow-up pelvic MR exam. Axial TSE T2-weighted (A) and post-contrast axial GRE T1-weighted (B) images show a retrouterine, large, well-delimited cystic lesion with internal post-contrast-enhanced nodules (arrows) and partial septations (arrowhead). This lesion was surgically excised and histopathologically confirmed as to be a recidivate mesothelioma (u, uterus)

DISCUSSION

Mesotheliomas are rare tumors originating from mesothelial cells of serosal membranes such as the pleura, peritoneum,4 pericardium, and tunica vaginalis.1 Simultaneous pleural and peritoneal involvement occurs in 30–45% of cases, whereas disease limited to the peritoneum occurs in 10 to 20% of the patients.5 Peritoneal mesotheliomas can be classified as benign (adenomatoid, fibrous),3,6 borderline (multicystic, well-differentiated papilliferous),1,4, 7,8 and malignant (epithelioid, sarcomatoid or biphasic/mixed),8 and their characteristics are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Features of mesothelioma-type tumors as reported in the literature

| Well-differentiated papilliferous peritoneal mesothelioma 2 | Multicystic peritoneal mesothelioma 4, 6, 7, 22–25 | Fibrous peritoneal mesothelioma 6 | Malignant peritoneal mesothelioma 16, 26 | Peritoneal adenomatoid mesothelioma [1,3,5,10–13] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean patient age | 30 to 50 years (46.1 ± 13.65 years) | 37 years and 10 months | 40 to 70 years | 26 to 55 years (average of 41 years old) | |

| Sex | Predominance in women (65.9%) | Predominance in women of reproductive age | Predominance in men, 2 to 10 times more common than in women | Predominance in men | |

| Risk factors | No established etiology | History of abdominal surgery (53% of cases), endometriosis or inflammatory pelvic disease.

No etiologic association with asbestos. |

Chronic peritoneal irritation and previous laparotomy | Exposure to asbestos (15 to 30 % of cases)

Exposure to beryllium, nuclear radiation, and chronic inflammatory diseases. |

No established etiology |

| Macroscopy | Multiple or single small nodular lesions incidentally detected during surgery (0.5 to 3 cm) | Multiple confluent translucent cysts forming a mass, without hemorrhage, fat or calcifications in their walls | Encapsulated and solid lesions | Solitary bulky lesion, usually small (2cm or less); with no capsule; may present small cystic components | |

| Clinical signs and symptoms | Asymptomatic tumor (55%)

Abdominal pain (38.3%) Ascites (33.3%) Pelvic mass (11.1%) Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (11.1%) Constipation (5.5%) |

Abdominal mass (29%) + distension/abdominal pain (46%)

Asymptomatic abdominal mass (18%) |

Abdominal pain syndrome

Ascites Abdominal mass Alterations of intestinal transit (alternating diarrhea and constipation or symptoms simulating an obstructive crisis). |

Asymptomatic (incidental finding)

Abdominal pain Weight loss Loss of appetite Nausea Ascites Pelvic mass |

|

| Survival | More than five years after diagnosis | Mean survival of 8–12 months after diagnosis (10) | |||

| Treatment | Surgical | The tumor is not sensitive to chemotherapy or radiotherapy | Surgical | Cytoreduction surgery with extensive peritonectomy and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy | Surgical |

| Location | 26% in abdominal or pelvic organs

22% in the omentum 16% on the pelvic wall 14% in the mesentery 14% in the peritoneum 8% in the Douglas cul-de-sac |

Genital tract of both sexes | |||

| Number of reported cases | 41 cases | 130 cases | 15 cases | 1–2 cases/million inhabitants/year | |

| Prognosis | Possibility of malignant transformation | Local recurrence | Local recurrence | Local recurrence | Local recurrence |

| Differential diagnosis | Serous tumor of the ovarian surface

Metastatic tumor usually of the gastrointestinal tract |

Cystic lymphangioma

Endometriosis Cystoadenoma and cystoadenocarcinoma of the ovary Teratoma Peritoneal pseudomixoma Necrotic leiomyoma - Leiomyosarcoma Peritoneal inclusion cyst |

Peritoneal tuberculosis

Peritoneal carcinomatosis Peritoneal lymphoma Metastases of an ovarian carcinoma |

Malignant mesothelioma

Mesothelial hyperplasia Well-differentiated papilliferous peritoneal mesothelioma Metastases |

Peritoneal adenomatoid mesothelioma (AMP) is a benign neoplasia9,10 of unknown etiology that primarily involves the genital tract of both sexes,9,10 occurring more frequently among males.1,3,8,11–13

We report here a case of a 25-year-old woman diagnosed with AMP that was confined to the peritoneum. Among women, adenomatoid tumors are more commonly encountered in the myometrium (posterior wall of the uterus), in the fallopian tubes, in paraovarian connective tissue,1,10–12 and rarely in the ovaries.1,9 In our patient, the uterus and ovaries were free of disease, and the lesion was confined to the peritoneum.

Among males, in most cases the tumor is detected in the inferior pole of the epididymis,9,10 but it can also involve the ejaculatory duct, sperm cord, tunica albuginea, tunica vaginalis, testicular parenchyma, prostate, and rarely the spermatic funiculus.1,9–13

Adenomatoid tumors have also been detected in the omentum, mesentery, pancreas, liver, bladder, mediastinal lymph nodes, pleura, heart, and adrenal glands.3,9,11,13 The cause of the apparent predominance in the genital tract when compared to other mesothelial locations has not been explained.3 Historically, adenomatoid tumors have always attracted interest regarding their histological origin, and several hypotheses have been proposed. Immunohistochemical studies favor mesothelial histogenesis.1,10 The “adenomatoid” designation was introduced by Golden and Ash in 19451,9,10 because of the arrangement of the cells in a cohesive manner, forming tubules and canaliculi. Four histological patterns of adenomatoid tumors have been identified and classified as adenoid, angiomatoid, solid or cystic.1,3 The histological pattern of the present case was classified as solid. The peak incidence of this tumor is between the 3rd and 5th decades of life, between 26 and 55 years (mean: 41 years), with an extremely rare occurrence in children.1,10

AMP is an uncommon tumor,3 usually asymptomatic,9 and is incidentally discovered during radiologic exams, surgeries or autopsies.3,9 It is typically a single polypoid or nodular small lesion (2.0 cm or less)1,14 that can measure up to 13 cm in diameter in a few cases.1 Adenomatoid tumors are usually solid, not encapsulated and often contain small cystic lesions (0.4 to 1.5 cm).12 When present, signs and symptoms are abdominal pain, loss of weight, loss of appetite, nausea, fluid accumulation in the peritoneal space (ascites), and a pelvic mass.8

In the present case, the tumor was 15 cm at its widest diameter on pathological examination, exceeding the size of previously reported masses. This might explain why the patient was symptomatic; additionally, after surgical resection, symptoms disappeared for a period of approximately one year. After that, the lesion recurred, and the patient was submitted to a new surgical intervention. The patient has now been free of the disease for 7 years.

Usually, surgical resection is the treatment of choice for AMP. Accurate diagnosis and staging are important because of the obvious therapeutic implications.15 Although benign, AMP is a source of great concern due to the differential diagnosis of malignant entities.10

In the present case, in view of the location of the tumor in the cul-de-sac and its histopathological characteristics (cells clustered in a papillary formation), it was necessary to establish a differential diagnosis with adenocarcinoma.1 Histology revealed medium-sized polygonal cells in an acinar, tubular and papilliform cell arrangement, a low mitotic index (up to 1), a mild grade of atypia, abundant vascularization, and absence of necrosis, suggesting an adenomatoid tumor.14

Immunohistochemistry revealed positivity for calretinin, which labels mesothelial cells in 60 to 100% of cases1,9,13 and rarely labels adenocarcinomas (0 to 28%). In addition, the cells of the neoplasia reported here were negative for BerEp4, which labels epithelial cells that are not present in mesotheliomas.2,5 The present case was negative for CEA immunoreagent, which frequently labels pulmonary and gastrointestinal carcinomas and is detected in only 0 to 35% of serous ovarian carcinomas.2,16 Thus, negativity of this marker is of no help for differentiation between adenomatoid tumors and adenocarcinomas. The possibility of the latter was ruled out due to immunohistochemistry compatible with an adenomatoid tumor, and by MRI and laparotomy findings that revealed disease-free ovaries. Another possible differential diagnosis for this case, arising from its location in a cul-de-sac, would be a metastatic tumor. However, CEA negativity and calretinin positivity do not favor this possibility, as demonstrated in Table 3. Other differential diagnoses are cysts of peritoneal inclusion, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas,12 mesothelial hyperplasia, malignant mesotheliomas,9 and well-differentiated papilliferous mesotheliomas.

Table 3.

| Adenocarcinomas (%) | Mesotheliomas (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| CEA | 90–100 | 0–10 |

| B72.3 | 81 | 0–5 |

| BEREP4 | 90–100 | 0–11 |

| CD15(LEU-M1) | 58–100 | 0–10 |

| Calretinin | 6–9 | 42–100 |

Mesothelial hyperplasia has been associated with peritoneal insults such as hernia, ectopic tubal pregnancy, and abdominal cirrhosis and tuberculosis3 and is accompanied by adherences and chronic inflammation.14 This entity rarely produces tumoral masses and does not have the tubulopapilliferous complex or the labyrinth architecture of mesotheliomas.14 The differential diagnosis with malignant mesothelioma and well-differentiated papilliferous mesothelioma is made on the basis of the distinct histological characteristics of these tumors when compared to AMP.17

MR has become a valuable noninvasive technique for evaluation of the female pelvis,18–20 with advantages over computed tomography and ultrasound for diagnosis and for staging various pathological conditions of the pelvis (leiomyoma, adenomyosis, carcinoma of the endometrium and of the uterine cervix, carcinoma of the vagina, ovarian cysts, endometriosis, teratomas, polycystic ovaries, and other ovarian masses).18,20

MR has proven to be a highly sensitive modality for characterization of pelvic masses, allowing physicians to determine whether the pelvic mass is uterine or of adnexal origin and also to characterize most adnexal masses.20 MR can also provide multiplanar information, revealing additional information when compared to CT or US. This is especially true along the pelvic walls and the presacral space.18,20 MR is also especially useful for surgical planning15 and patient follow-up. Low et al21 studied 24 patients with suspected peritoneal tumors and found that MR had higher sensitivity, specificity and accuracy than CT in the detection of tumors (84%, 87% and 86%, compared to 54%, 91% and 74%, respectively, for CT) and was superior for detection of carcinomatosis and of tumors measuring less than 1 cm in diameter (75% to 80% for MR and 22% to 33% for CT). Post-contrast T1-weighted images with fat suppression were proven to be the most sensitive MR technique for detecting peritoneal disease. MR and CT showed identical performance for detection of tumors measuring more than 2 cm and 1 to 2 cm in diameter.21

Notably, the high sensitivity of the MR exam could depict both ovaries as free of disease and was able to characterize the lesion as not having ovarian or uterine origin; this could not be achieved by ultrasound examination. Also, to date, we believe that this is the first case both to show MR findings for AMP and to correlate these findings to ultrasound and computed tomography. Descriptions of imaging findings regarding AMP are scarce in the literature. AMP seems to have no specific radiological characteristics, and it is important to establish a correlation between clinical presentation and the imaging and laboratory findings. At this point, it is necessary to reinforce that diagnosis can only be confirmed by anatomopathology and immunohistochemistry.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanada S, Okumura Y, Kaida K. Multicentric adenomatoid tumors involving uterus, ovary, and appendix. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2003;29:234–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1341-8076.2003.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoekman K, Tognon G, Risse EK, Bloemsma CA, Vermorken JB. Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma of the peritoneum: a separate entity. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:255–8. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hayes SJ, Clark P, Mathias R, Formela L, Vickers J, Armstrong GR. Multiple adenomatoid tumours in the liver and peritoneum. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:722–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.035386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong WL, Johns TA, Herlihy WG, Martin HL. Best cases from the AFIP: multicystic mesothelioma. Radiographics. 2004;24:247–50. doi: 10.1148/rg.241035068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson B. Biological characteristics of cancers involving the serosal cavities. Crit Rev Oncog. 2007;13:189–227. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v13.i3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adachi T, Sugiyama Y, Saji S. Solitary fibrous benign mesothelioma of the peritoneum: report of a case. Surg Today. 1999;29:915–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02482786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawh RN, Malpica A, Deavers MT, Liu J, Silva EG. Benign cystic mesothelioma of the peritoneum: a clinicopathologic study of 17 cases and immunohistochemical analysis of estrogen and progesterone receptor status. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:369–74. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daya D, McCaughey WT. Pathology of the peritoneum: a review of selected topics. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1991;8:277–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isotalo PA, Nascimento AG, Trastek VF, Wold LE, Cheville JC. Extragenital adenomatoid tumor of a mediastinal lymph node. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:350–4. doi: 10.4065/78.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gokce G, Kilicarslan H, Ayan S, Yildiz E, Kaya K, Gultekin EY. Adenomatoid tumors of testis and epididymis: a report of two cases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;32:677–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1014489306023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cajaiba MM, Senise SM, Osório CABdT, Pinto CAL. Adenomatoid Tumor of Myometrium: Report of Three Cases. Applied Cancer Research. 2005;25:3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghossain MA, Chucrallah A, Kanso H, Aoun NJ, Abboud J. Multilocular adenomatoid tumor of the ovary: ultrasonographic findings. J Clin Ultrasound. 2005;33:233–6. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamamatsu A, Arai T, Iwamoto M, Kato T, Sawabe M. Adenomatoid tumor of the adrenal gland: case report with immunohistochemical study. Pathol Int. 2005;55:665–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2005.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldblum J, Hart WR. Localized and diffuse mesotheliomas of the genital tract and peritoneum in women. A clinicopathologic study of nineteen true mesothelial neoplasms, other than adenomatoid tumors, multicystic mesotheliomas, and localized fibrous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1124–37. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Devine C, Szklaruk J, Tamm EP. Magnetic resonance imaging in the characterization of pelvic masses. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26:172–204. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trupiano JK, Geisinger KR, Willingham MC, Manders P, Zbieranski N, Case D, et al. Diffuse malignant mesothelioma of the peritoneum and pleura, analysis of markers. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:476–81. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhandarkar DS, Smith VJ, Evans DA, Taylor TV. Benign cystic peritoneal mesothelioma. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:867–8. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.9.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Ruth S, Bronkhorst MW, van Coevorden F, Zoetmulder FA. Peritoneal benign cystic mesothelioma: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2002;28:192–5. doi: 10.1053/ejso.2000.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szklaruk J, Tamm EP, Choi H, Varavithya V. MR imaging of common and uncommon large pelvic masses. Radiographics. 2003;23:403–24. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson MC, Posniak HV, Tempany CM, Dudiak CM. MR imaging of the female pelvic region. Radiographics. 1992;12:445–65. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.12.3.1609137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Low RN, Barone RM, Lacey C, Sigeti JS, Alzate GD, Sebrechts CP. Peritoneal tumor: MR imaging with dilute oral barium and intravenous gadolinium-containing contrast agents compared with unenhanced MR imaging and CT. Radiology. 1997;204:513–20. doi: 10.1148/radiology.204.2.9240546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bui-Mansfield LT, Kim-Ahn G, O’Bryant LK. Multicystic mesothelioma of the peritoneum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;178:402. doi: 10.2214/ajr.178.2.1780402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozgen A, Akata D, Akhan O, Tez M, Gedikoglu G, Ozmen MN. Giant benign cystic peritoneal mesothelioma: US, CT, and MRI findings. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:502–4. doi: 10.1007/s002619900387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Romero JA, Kim EE, Kudelka AP, Edwards CL, Kavanagh JJ. MRI of recurrent cystic mesothelioma: differential diagnosis of cystic pelvic masses. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;54:377–80. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soreide JA, Soreide K, Korner H, Soiland H, Greve OJ, Gudlaugsson E. Benign peritoneal cystic mesothelioma. World J Surg. 2006;30:560–6. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0639-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puvaneswary M, Chen S, Proietto T. Peritoneal mesothelioma: CT and MRI findings. Australas Radiol. 2002;46:91–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1673.2001.01002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]