Abstract

Wolbachia is a ubiquitous intracellular endosymbiont of invertebrates. Surprisingly, infection of Drosophila melanogaster by this maternally inherited bacterium restores fertility to females carrying ovarian tumor (cystocyte overproliferation) mutant alleles of the Drosophila master sex-determination gene, Sex-lethal (Sxl). We scanned the Drosophila genome for effects of infection on transcript levels in wild-type previtellogenic ovaries that might be relevant to this suppression of female-sterile Sxl mutants by Wolbachia. Yolk protein gene transcript levels were most affected, being reduced by infection, but no genes showed significantly more than a twofold difference. The yolk gene effect likely signals a small, infection-induced delay in egg chamber maturation unrelated to suppression. In a genetic study of the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction, we established that germline Sxl controls meiotic recombination as well as cystocyte proliferation, but Wolbachia only influences the cystocyte function. In contrast, we found that mutations in ovarian tumor (otu) interfere with both Sxl germline functions. We were led to otu through characterization of a spontaneous dominant suppressor of the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction, which proved to be an otu mutation. Clearly Sxl and otu work together in the female germline. These studies of meiosis in Sxl mutant females revealed that X chromosome recombination is considerably more sensitive than autosomal recombination to reduced Sxl activity.

BACTERIA of the genus Wolbachia are believed to be the most common endosymbiont in the Drosophila genus (Clark et al. 2005; Mateos et al. 2006). The intimate association between these maternally inherited gram-negative bacteria and their various arthropod hosts has even resulted in lateral transfer of part or all of the endosymbiont's genome into their hosts' chromosomes (Hotopp et al. 2007). Infection of arthropods by Wolbachia has been associated with a remarkable variety of reproductive abnormalities that facilitate transmission of the bacteria through females, often to the detriment of the hosts (recently reviewed by Werren et al. 2008). These deleterious effects include parthenogenesis, feminization, male killing, and cytoplasmic incompatibility. In some cases, however, the effects of infection can seem beneficial. For example, the wasp Asobara tabida has become “genetically addicted” (Werren et al. 2008) to Wolbachia, with infection being required for oogenesis (Dedeine et al. 2005; and see Pannebakker et al. 2007). An analogous addiction to Wolbachia was observed for Drosophila melanogaster homozygous for female-sterile “ovarian tumor” alleles of the master sex-determination gene Sex-lethal (Sxl). Infection restored the ability of these mutant females to make eggs and hence be fertile (Starr and Cline 2002). Although the initial aim of the work described here was to discover the molecular basis for the effect of Wolbachia on Sxl mutant ovaries, the study led to a better understanding of the involvement of Sxl in meiotic recombination and the functional relationship between Sxl and the gene ovarian tumor.

Sxl is the master switch gene that controls Drosophila sex determination (reviewed in Cline and Meyer 1996). Although complete loss-of-function Sxl alleles are female-specific lethal, three different partial loss-of-function point mutant alleles Sxlf4, Sxlf5, and Sxlf18 are fully viable but female sterile (Bopp et al. 1993; Starr and Cline 2002). Most developing egg chambers in the ovaries of females homozygous for these Sxlfemale-sterile alleles fail to make mature eggs. Instead they exhibit a characteristic “ovarian tumor” phenotype, filling with rampantly proliferating cystocyte-like germ cells (Salz et al. 1987; Oliver et al. 1988). Cystocytes are mitotically active, terminally differentiating germ cells that normally divide only four times. The rare eggs that are made and laid by Sxlfs females do not develop into adults. However, in Sxlfs mutant flies infected by Wolbachia, a much larger proportion of egg chambers develop into normal-appearing eggs and the females can produce progeny (Starr and Cline 2002). Fertility of these infected Sxlfs females is still very low, due in part to severe meiotic defects in the rescued eggs.

The success of Wolbachia can be attributed not only to its maternal inheritance, but also to its ability to escape the host's immune system, neither inducing nor suppressing the transcription of antimicrobial genes (Bourtzis et al. 2000). We wondered whether infection might nevertheless have effects on gene expression in wild-type Drosophila that could provide clues to the molecular nature of the Sxl–Wolbachia interaction. Toward this end we employed microarray analysis (Andrews et al. 2006) to screen for Drosophila genes whose transcript levels are affected by infection. Meaningful comparisons between infected and uninfected flies were facilitated by the fact that Wolbachia is only transmitted maternally. As a consequence, simple reciprocal crosses between infected (I) and uninfected (U) parents (I ♀ × U ♂ vs. U ♀ × I ♂) generate daughters that differ genetically only with respect to Wolbachia.

Two facts made us believe that RNA from the previtellogenic (immature) ovaries of newly eclosed wild-type females would provide the best signal-to-noise ratio for our purposes. First, the effects of Sxlfs mutations are exclusively germ cell autonomous, as shown by the fact that true reversion of these point mutations in a single germline stem cell is sufficient to restore fertility to an otherwise homozygous mutant female (see materials and methods). Hence suppression is likely to involve a process that is autonomous to the ovary itself. Second, the abnormal behavior of Sxlfs mutant germ cells that Wolbachia suppresses begins early in oogenesis, just after the differentiating daughter of a wild-type germline stem cell embarks on its last four mitotic divisions, and long before any mature eggs would be produced. Therefore by collecting ovaries from newly eclosed females that necessarily lack late-stage egg chambers and mature eggs, we would maximize the fraction of gonadal cells at the stage known to be relevant to the Sxl–Wolbachia interaction.

The molecular part of this study was followed by genetic analysis of the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction, including characterization of a spontaneous mutation that blocked it. This genetic analysis led to the discovery of an intimate functional relationship in germ cells between Sxl and the ovarian tumor (otu) gene, and to an appreciation of important differences between the Sxl–otu functional relationship and that between Sxl and Wolbachia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains and culture:

Flies were raised at 25° in uncrowded conditions on a standard cornmeal, yeast, sucrose, and molasses medium. Mutant alleles, duplications and balancers are described at FlyBase (http://flybase.org) except as indicated below. Wolbachia-infected wild-type (Canton-S) flies were from D. Presgraves.

Tissue preparation, RNA preparation, and cDNA array hybridization:

Female flies were collected 0–2 hr after eclosion and aged for 1–3 hr at room temperature before being dissected on ice. Dissected ovaries were transferred directly to TRIzol and frozen at −80° before RNA extraction. RNA preparation and cDNA labeling were as described in Drosophila Genomics Resource Center protocols (Bogart and Andrews 2006; Conaty et al. 2006) using Trizol RNA isolation, QIAGEN RNeasy cleanup, Amersham Biosciences direct labeling kit, and 20–25 μg total RNA for each sample preparation.

Array procedures:

Drosophila whole genome cDNA microarrays (Andrews et al. 2006) were used with a modified hybridization procedure employing reagents and apparatus from Agilent (Hughes et al. 2001). Hybridization was done at 65° for ∼17 hr. Arrays were read on an Axon 400B scanner and preanalyzed using GenePix 6.0.

Array analysis:

Eight replicates of dual channel arrays were performed with dye swaps using RNA extracts from five independent dissections of infected and uninfected ovaries. A total of 15,552 probes corresponding to ∼88% of the version 4.1 annotated D. melanogaster genome sequence were on the array (Andrews et al. 2006). A threshold value of 999 for the combined Cy3 and Cy5 intensity was used to determine whether a probe returned a meaningful signal. A total of 2822 probes, representing 2521 unique genes, showed above-threshold signals on no fewer than six of the eight replicate array slides and were therefore considered meaningful. To avoid bias from differences in labeling efficiency between the two dyes (Conaty et al. 2006), intensity values were processed as though they were from a single channel, with Cy3 and Cy5 signals considered independent. Ratios of intensity values for infected and uninfected samples with the same dye labeling on two concurrently processed array slides were calculated and normalized using the ratio of medians.

Real-time quantitative PCR:

First strand cDNA synthesis followed New England Biolabs' first-strand cDNA synthesis kit with (N)9 random primer. SYBR Green (Invitrogen) was added in the PCR reaction at a concentration of 0.1×. The quantitative PCR reactions were performed and analyzed on a BioRad (MJ) Opticon Engine 2 system. The PCR conditions were set at 95° 5 min, followed by 94° 30 sec, 60° 30 sec, 72° 1 min, and 78° 10 sec, Plate Read for 40 cycles. Primer pairs and sequences are listed in supplemental Table 1S.

Germline reversion of Sxlf18:

Grossly overcrowded vials of 24- to 48-hr-old larvae from a Wolbachia-infected w Sxlf18/FM3, y B let stock were exposed to 1300 rad of gamma irradiation then transferred to uncrowded conditions to complete development. In this way 18,320 homozygous Sxlf18 adult females were recovered with their Sxlf18/Y brothers and partitioned 40 females per vial. Three 4-day progeny collections were made. Fertility of the infected Sxlf18 females was very low even in the first collection (mean 19.6 progeny/vial) and declined precipitously by the second and third collections. When progeny were present from the second and/or third collections, they were pooled and used as parents for the next generation. By the second 4-day collection from that next generation, only vials that had females carrying mutations that enhanced fertility contained progeny. Four true revertants (A → G) of the Sxlf18 point mutation were recovered from an estimated 460,000 mutagenized female germ cells.

Origin and molecular nature of Sxlf24,M1:

This male-viable derivative of the dominant male-lethal allele SxlM1 was obtained in a simple genetic selection based on the fact that SxlM1 suppresses snf1621 female sterility at 18° and 25°, while snf1621 suppresses SxlM1 male lethality only at 18° (Steinmann-Zwicky 1988; T. W. Cline, unpublished data). Consequently, a y w snf1621 SxlM1 stock could be maintained easily at 18°, but at 25° produce virgins in large numbers because all sons died. In this way 4500 0- to 1-day-old virgins were collected, exposed to 3400 rad of gamma rays, and mated to wild-type males 18 hr later at 25°. A screen of 162,000 X chromosomes yielded 17 fertile y w males, all carrying loss-of-function Sxl alleles. The recessive female-specific lethal Sxlf24,M1 was one of eight hypomorphs recovered. Its CC → AT change at position 12,771 substitutes asparagine for a conserved threonine just upstream of RNP2 in the second RNA recognition motif.

Origin of SxlM6,f3:

By templated P-element excision-induced DNA gap repair (Gloor et al. 1991), the Sxlf3 lesion was transferred from SxlM1,f3 to SxlM6. The single-base-pair change in SxlM6 (Cline et al. 1999) induces a level of constitutive Sxl female pre-mRNA splicing similar to that of the 9-kb roo transposon in SxlM1 (Bernstein et al. 1995). Selecting for male-viable derivatives, first we hopped a w+-tagged P[lacW] transgene (Bier et al. 1989) into SxlM6 to generate SxlM6,P[lacW]A. Its P[lacW] in exon 2 at position 6067 was then remobilized in SxlM6,P[lacW]A/SxlM1,f3 females, and any of their SxlM6[Δ] sons that had lost the w+ transgene were tested for the increase in Sxl function expected for a replacement of P[lacW] by Sxlf3. DNA sequencing confirmed clean transposon excision and the presence of SxlM6 and Sxlf3. We discovered that Sxlf3 also carries a 1-bp frameshift deletion in exon 2 just two nucleotides upstream of the G → C substitution at position 6395 previously reported (Bernstein et al. 1995), and a 26-bp intronic deletion of nucleotides 168–193 (probably without functional consequence) present in the parental allele, SxlM1.

RESULTS

Wolbachia infection has little effect on gene expression in previtellogenic ovaries:

To generate the ovaries to be compared by microarray analysis, we cured a wild-type Canton-S line of its well-characterized YW strain of Wolbachia (Bourtzis et al. 1998; Presgraves 2000) by raising the flies for three generations on food containing tetracycline. After three more generations on food without tetracycline, we confirmed by PCR (O'Neill et al. 1992) that the line was Wolbachia free. We harvested genetically matched previtellogenic infected (I) and uninfected (U) ovaries from 1- to 5-hr-old adult females that were progeny from reciprocal crosses between the infected and the cured Canton-S lines. The strict maternal inheritance of Wolbachia ensured that all daughters of the I ♀̆♀̆ × U ♂♂ cross would be infected, while all daughters of the reciprocal U ♀̆♀̆ × I ♂♂ cross would be uninfected, but in all other respects these daughters would be genetically identical.

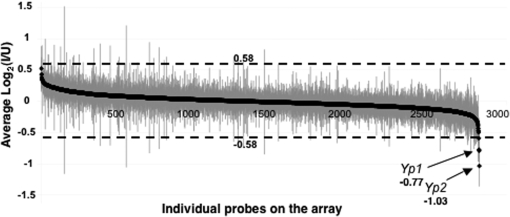

The Drosophila whole genome cDNA microarray used (Andrews et al. 2006) carried probes for 88% of the fly's genes. Probes representing 2551 unique genes gave signals above threshold for the ovarian transcripts. The expression difference for each gene was calculated as the average log2 ratio of I to U samples and presented in Figure 1 in descending order with standard errors indicated (supplemental Table 2S). For all but 4 of the probes, average log2 ratios fell between −0.58 and 0.58 (less than a 1.5-fold difference). The vast majority were close to 0 (no difference). Hence, it appears that nearly all previtellogenic ovarian gene expression, at least as inferred by this crude measure of transcript levels, is unaffected by Wolbachia infection.

Figure 1.—

Array expression intensity for infected (I) vs. uninfected (U) wild-type previtellogenic ovaries. The average log2 ratio (I/U) for each probe is plotted with solid diamonds in descending order of magnitude, with shaded vertical lines indicating standard errors (values listed in supplemental Table 2S). On the ordinate, 0.58 and −0.58 correspond to a 1.5-fold difference in log2 ratio.

Wolbachia infection reduces yolk gene expression in previtellogenic ovaries:

Although infection of wild-type ovaries had no striking effect on the level of mRNA for any gene, our attention was drawn to a modest effect on yolk gene expression not only because the major yolk protein gene Yp2 showed the largest change (twofold higher expression in U ovaries), but also because the other major yolk protein gene, Yp1, showed the third largest difference (1.7-fold higher in U ovaries).

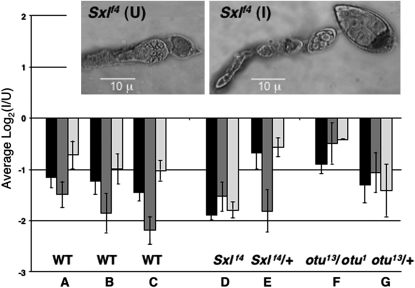

Using qRT–PCR with rp49 as the internal standard (Figure 2, A–C), we not only confirmed that infection reduces expression of Yp1 and Yp2 (P < 0.01), but also discovered that expression of the only other gene of this class, the minor yolk protein gene Yp3, was also nearly twofold higher in U ovaries. The fact that transcripts from Yp3 are much less abundant and more variable than those from the two major yolk genes (Bownes 1994) likely accounts for the failure of Yp3 to stand out in the microarray study. We could not use qRT–PCR to verify the expression difference of the second most affected gene, Vm32E (1.73-fold higher expression in U ovaries), because its structure did not lend itself to this technique. Vm32E encodes a vitellin membrane protein.

Figure 2.—

Effects of Wolbachia infection on yolk gene expression assayed by qRT–PCR. The average log2 ratios (I/U) for previtellogenic ovarian transcripts from Yp1 (solid), Yp2 (dark shading), and Yp3 (light shading), are shown, with standard errors indicated. Values were normalized against rp49 as an internal control for A–C and against Act5C for D–G (see text). (A–C) qRT–PCR confirming and extending microarray results for wild-type (Canton-S) ovaries from three independent dissections. (D and E) Effect of infection on Yp transcript levels in Sxlf4 and Sxlf4/+ ovaries, where females were daughters from reciprocally crossed (I) and (U) w cm Sxlf4 sn/Binsinscy lines. The inset shows the tumorous germline phenotype of uninfected Sxlf4 ovaries (left) and its suppression by infection with Wolbachia (right). (F and G) Effect of infection on otu13/otu1 and otu13/+ ovaries, where the I females were from (I) ctn otu1 v24/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ (U) y cv otu13 v f/Y and the U females were from (U) ctn otu1 v24/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ (I) y cv otu13 v f/Y. The (I) and (U) ctn otu1 v24/Binsinscy virgins were obtained from reciprocally crossed (I) and (U) ctn otu1 v24/Binsinscy lines.

In the microarray experiment, we purposely examined the effects of Wolbachia infection on gene expression in wild-type rather than Sxlfs mutant ovaries to avoid being swamped by the many uninformative differences in gene expression that would necessarily accompany suppression of the tumorous-ovary phenotype. However, having found an effect of infection on particular genes in the wild-type situation, we could profitably ask whether those same genes would be affected in a comparison of infected vs. uninfected Sxlfs ovaries, notwithstanding their developmental differences. Data in Figure 2D for Sxlf4 ovaries show that the effect of infection on Yp gene expression in mutant ovaries was similar in magnitude and direction to that in wild-type ovaries. For the Sxlf4 comparison, we could not use rp49 transcripts as the normalization standard, since we found that rp49 transcripts were much reduced in the tumorous situation (data not shown). Instead we used Act5C as the normalization standard for the Figure 2 genotypes D–G, after determining that the abundance of Act5C transcripts relative to those from rp49 was unaffected by infection in wild-type ovaries (supplemental Figure 1S).

Figure 2 also presents yolk gene transcript data for ovaries that are mutant for ovarian tumor (otu13/otu1). Since otu mutants are not suppressed by Wolbachia (Starr and Cline 2002), the comparison in this case (Figure 2F) was between ovaries that were both tumorous. Again, yolk gene transcript levels were reduced by infection. The nontumorous internal controls for the Sxlf4 and otu13/otu1 comparisons (Figure 2, E and G) also showed an unambiguous effect of infection on yolk gene transcript levels.

We saw no significant effect of infection on yolk gene expression at 11–13 hr and 23–25 hr posteclosion, when vitellogenesis is well underway. At these later times, yolk gene transcript levels were 10- to 15-fold higher than for the 1- to 5-hr ovaries as assessed by qRT–PCR (data not shown).

Reducing otu gene dose greatly reduces suppression of Sxlf4 by Wolbachia:

We fortuitously discovered a genetic background in which Wolbachia appeared to be unable to suppress Sxlf4 defects in oogenesis—our first encounter with a nonpermissive background for suppression in several years of studying the phenomenon. This suppressor of Wolbachia suppression of Sxlf4, designated Su(Ws), was dominant, X-linked, and strictly zygotic in its effect, as shown by data in the first four rows of Table 1. Dominance is indicated by the fact that more than half of the infected Sxlf4/Sxlf4 daughters from either reciprocal cross between one infected parent from the nonsuppressible background and the other from the suppressible background (crosses 1-1 and 1-2) could not make eggs, and of those that could, none were in either of the two highest categories (the suppressible females for comparison are those from cross 1-3, see below). Since the parental origin of Su(Ws) in the reciprocal crosses 1-1 and 1-2 had no influence on suppressibility, Su(Ws) must not have a maternal effect. X chromosome linkage was established from crosses 1-3 and 1-4 that were set up from the appropriate progeny of crosses 1-1 and 1-2 so that the autosomal complement of the females being compared would be the same. All infected daughters receiving both X chromosomes from the suppressible background made eggs, with 53% scoring in the highest category (cross 1-3), while no daughter with two X chromosomes from the nonsuppressible background could make eggs (cross 1-4).

TABLE 1.

Dominant suppression by otu− of Wolbachia suppression of Sxlf4

| Mature eggs per femaleb

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross | Genotypea | Infected? | (n) | 0 | 1–2 | 3–10 | 11–20 | 21–30 | >30 |

| % females in class | |||||||||

| 1-1c |  |

Yes | (53) | 66 | 25 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1-2c |  |

Yes | (73) | 70 | 25 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1-3d |  |

Yes | (30) | 0 | 7 | 20 | 3 | 17 | 53 |

| 1-4d |  |

Yes | (35) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2-1e |  |

Yes | (26) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 96 |

| 2-2e |  |

Yes | (73) | 77 | 15 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2-2e |  |

Yes | (19) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 95 |

| 3-1 |  |

No | (28) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 7 | 75 |

| 3-2f |  |

No | (52) | 98 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3-3f |  |

Yes | (37) | 22 | 35 | 24 | 16 | 3 | 0 |

Full genotype of crosses:

1-1: cm Sxlf4 Su(Ws)/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w cm Sxlf4sn3/Y (reciprocal of 1-2).

1-2: w cm Sxlf4sn3/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ cm Sxlf4 Su(Ws)/Y (reciprocal of 1-1).

1-3: w cm Sxlf4 sn3/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w cm Sxlf4 sn3/Y (♀̆ from cross 1-1, ♂ from 1-2).

1-4: cm Sxlf4 Su(Ws)/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ cm Sxlf4 Su(Ws)/Y (♀̆ from cross 1-2, ♂ from 1-1).

2-1: w cm Sxlf4 sn3/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w cm Sxlf4 sn3/Y; SM6,Cy/+ (data for Cy+ only).

2-2: w cm Sxlf4 sn3/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w cm Sxlf4 otu17/Y; SM6,Cy/+ (data for Cy+ only).

3-1: w Sxlf2 ct6/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w cm Sxlf4 sn3/Y.

3-2: w Sxlf2 ct6/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w cm Sxlf4 otu17/Y.

3-3: w cm Sxlf4 otu17/Binsinscy ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ w Sxlf2 ct6/Y.

The maternally derived chromosome is on top and the paternally derived below.

Stage 14 and late stage 13 eggs in 4- to 5-day-old virgins.

Crosses 1-1 and 1-2 are reciprocal.

The autosomes in crosses 1-3 and 1-4 are identical.

The fathers for crosses 2-1 and 2-2 were brothers and the mothers were sisters.

Crosses 3-2 and 3-3 are reciprocal.

Su(Ws) behaved as a simple Mendelian difference from wild type that mapped to the vicinity of otu (data not shown). Mutations in otu can generate tumorous ovaries (Storto and King 1988) that are morphologically indistinguishable from those of Sxlfs mutants but otu tumors are not suppressed by Wolbachia (Starr and Cline 2002). We constructed a Sxl+ Su(Ws) chromosome and found that homozygous Sxl+ Su(Ws) females were sterile and exhibited an ovarian phenotype characteristic of hypomorphic otu mutants. Our suspicion that Su(Ws) was a mutant otu allele was confirmed by the fact that the Sxl+ Su(Ws) chromosome failed to complement the internally deleted null allele otu17 (data not shown). Moreover, otu17 dominantly blocked suppression of Sxlf4 by Wolbachia at least as effectively as Su(Ws) (compare Table 1 cross 2-2 to the genetically matched control cross 2-1). otu17 also dominantly blocked suppression of Sxlf18, a molecularly distinct class of Sxlfs allele less suppressed by Wolbachia (data not shown).

Since we had included otu mutant ovaries in our analysis of the effect of Wolbachia infection on yolk gene expression (Figure 2) and had seen that the effect persisted in genotypes that we now knew would block suppression of Sxlf4, we could conclude that the effect of Wolbachia on yolk gene mRNA levels must not be directly related to suppressibility per se. Ironically, the one situation in which we did not observe a significant effect on yolk genes by Wolbachia was with the original Su(Ws) chromosome (data not shown), but we do not attribute significance to this exception (see discussion).

otu affects Sxl germline functioning more broadly than Wolbachia:

The dominant effect of otu− on Wolbachia's ability to suppress Sxlfs alleles could reflect a specific involvement of otu in the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction. By that model, reducing otu activity would inhibit the ability of infection to increase the effectiveness of Sxlfs alleles without otherwise affecting Sxl germline functioning. Alternatively, reducing otu activity might cause a general reduction in Sxlfs germline functioning irrespective of infection. This “general reduction” model predicts that one should see dominant enhancement by otu− of Sxl germline phenotypes in situations where Sxl germline functioning has already been compromised, regardless of whether the female carries Wolbachia. One expects dominant effects because the suppression by otu− of Wolbachia's suppression of Sxlfs alleles is dominant. In contrast, if the effects of otu nulls were more specifically related to the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction, one would not expect to see those effects in uninfected females, or on any aspect Sxl germline functioning that Wolbachia did not affect.

Sxlf2/Sxlf4 mutant females show dramatically that otu null alleles can have a dominant effect on oogenesis in uninfected Sxl mutant females, as predicted by the “general reduction” model. As Table 1 shows, when Sxlf2/Sxlf4 females were otu+, all could make eggs (cross 3-1), but when they were also otu−/+, almost none made eggs (cross 3-2). Most egg chambers in these otu−/+ females were tumorous, and the few that were not were grossly abnormal (data not shown). As expected by the general reduction model, oogenesis in these otu heterozygotes improved upon infection by Wolbachia (cross 3-3), but remained inferior to that for otu+ females.

To address the second prediction of the “general reduction” model, namely that otu would affect aspects of Sxl germline function that Wolbachia did not affect, we had to determine whether there were aspects of Sxl germline function that were unaffected by Wolbachia. Meiosis seemed likely to be such a function. In the initial characterization of Sxlfs germline tumor suppression by Wolbachia, the fact that eggs from infected Sxlf4 mutant females displayed tremendously high rates of X chromosome nondisjunction (Starr and Cline 2002) was consistent with the hypothesis that Sxl had a germline function required for proper meiotic chromosome segregation, and that Sxlf4 was defective in this function to a degree that Wolbachia could not overcome. But that failure of Wolbachia to overcome the apparent Sxlf4 meiotic defect could be either because infection had no effect on that aspect of Sxl function or because its effect was not sufficiently strong to rescue. One could only discriminate between these two possibilities in a situation where the meiotic defect was much less severe, so that even a small effect of infection would be apparent—and in either direction. Part 1 of Table 2 presents data for such a situation.

TABLE 2.

Meiotic effects in Sxl mutant females

| Effect on meiosis

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recombination

|

% nondis-junction of X | |||||||

| Cross | Relevant female genotype | Infected? | Genetic interval (chromosome) | Progeny scoreda | Observed distance (cM) | % book value | Magnitude of effect (cross/cross) | |

| 1. Absence of a Wolbachia effect | ||||||||

| A1 | SxlM6,f3/Sxlf4 | No | y-sn (X) | 4563 | 2.4 | 12 | A1/B = 16% | 1.6 |

| A2 | SxlM6,f3/Sxlf4 | Yes | y-sn (X) | 4697 | 2.3 | 11 | A2/B = 15% | 1.0 |

| B | SxlM6,f3/Sxlf4; Dp(Sxl+)/+ | No | y-sn (X) | 3953 | 14.9 | 71 | (Sxl+ control) | <0.1 |

| 2. Dominant effect of SxlM6,f3 | ||||||||

| C1 | SxlM6,f3/+ | No | y-ct (X) | 1574 | 13.5 | 68 | C1/C2 = 68% | 0.1 |

| C2 | SxlM6,f3/+; Dp(Sxl+)/+ | No | y-ct (X) | 877 | 19.8 | 99 | (Sxl+ control) | 0.1 |

| 3. Dominant synergism between Sxl and otu− | ||||||||

| D1 | SxlM1,f3/Sxlf18 | No | y-ct (X) | 3319 | 3.9 | 20 | (otu+ control) | 0.5 |

| D2 | SxlM1,f3 otu−/ Sxlf18 + | No | y-ct (X) | 2989 | 1.3 | 7 | D2/D1 = 33% | 4.2 |

| E1 | SxlM1,f3 otu−/+ + | No | y-ct (X) | 4957 | 6.5 | 33 | E1/E2 = 48% | 1.7 |

| E2 | SxlM1,f3/+ | No | y-ct (X) | 4358 | 13.6 | 68 | (otu+ control) | <0.1 |

| F | Sxlf18/+ | No | y-ct (X) | 3930 | 19.4 | 97 | <0.1 | |

| G1 | otu−/+ | No | y-ct (X) | 8497 | 11.8 | 59 | G1/G2 = 99% | 0.9 |

| G2 | +/+ | No | y-ct (X) | 6647 | 11.9 | 60 | (otu+ control) | 0.4 |

| 4. Differential sensitivity of X vs. autosome in Wolbachia-suppressed Sxlf4 | ||||||||

| H | Sxlf4/Sxlf4 | Yes | w-sn (X) | 413 | 0 | <1 | 30 | |

| sn-f (X) | 99 | 0 | <3 | |||||

| al-b-c-sp (II) | 218 | 11 | 10 | H/J2 = 11% | ||||

| 5. Sxlf24,M1 complements Sxlf4 well for fertility but poorly for meiosis | ||||||||

| J1 | Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4 | No | y-cv-f (X) | 2437 | 0.2 | 0.4 | J1/J2 = 0.5% | 24 |

| al-dp-b-pr-cn-c-px-sp (II) | 3054 | 5.0 | 5 | J1/J2 = 5% | ||||

| J2 | Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4; Dp(Sxl+)/+ | No | y-cv-f (X) | 983 | 38.5 | 68 | (Sxl+ control) | ND |

| al-dp-b-pr-cn-c-px-sp (II) | 1540 | 102.9 | 96 | (Sxl+ control) | ||||

| K1 | Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4 | No | y-cv-f (X) | 693 | 0 | <0.2 | K1/K2 = <0.4% | ND |

| ru-h-th-st-cu-sr-e (III) | 2584 | 4.4 | 6 | K1/K2 = 7% | ||||

| K2 | Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4; Dp(Sxl+)/+ | No | y-cv-f (X) | 1532 | 35.5 | 63 | (Sxl+ control) | ND |

| ru-h-th-st-cu-sr-e (III) | 987 | 62.5 | 88 | (Sxl+ control) | ND | |||

Full genotype of crosses:

A1 and A2: y w cv SxlM6,f3 ct6/w cm Sxlf4 sn3 (U) and w cm Sxlf4 sn3/y w cv SxlM6,f3 ct6 (I) ♀̆, respectively, × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. Infected and uninfected mothers were from reciprocal crosses between an infected Sxlf4 stock and uninfected SxlM6,f3 stock. Twelve mothers for each cross.

B: y w cv SxlM6,f3 ct6/w cm Sxlf4 sn; Dp(1;3)sn13a1, cm+ Sxl+ct+/+ ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. Data for 10 mothers.

C1 and C2: y w cv SxlM6,f3 ct6/w sisters without (12♀̆) and with Dp(1;3)sn13a1,Sxl+ (10♀̆), respectively, ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v /Y. Recombination value is based on daughters only.

D1: y w SxlM1,f3 ct6 sn3/w Sxlf18 g f ♀̆ and ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ y v sisA m g f/Y. Data for 17 mothers. Recombination value is based on sons only.

D2: y w SxlM1,f3 ct6 otu17/w Sxlf18 g f ♀̆ and ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ y v sisA m g f/Y. The y-ct region on the SxlM1,f3 chromosome is identical to that of the SxlM1,f3 chromosome in Cross D1. Data for 25 mothers. Recombination value is based on sons only.

E1: y w SxlM1,f3 ct6 otu17/w ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. Data based on 10 mothers.

E2: y w SxlM1,f3 ct6 sn3/w ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. The y-ct region on the SxlM1,f3 chromosome is identical to that of the SxlM1,f3 chromosome in Cross E1. Data based on 10 mothers.

F: w Sxlf18 g f/y cm ct6 ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. Data for 6 mothers.

G1: y cm ct6 otu17/w ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. Nondisjunction is based on XO only. Data for 17 mothers.

G2: y cm ct6 sn3/w ♀̆ × ♂♂ y cm ct6 sn3 v/Y. The y-ct region on the w+ chromosome is identical to that of the w+ chromosome in cross G1. Nondisjunction is based on XO only. Data for 10 females.

H: w cm Sxlf4 sn/cm Sxlf4 v f; al b c sp/+ ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ y w cm ct6 sn3/Y; al b c sp/CyO. sn-f distance based on w+sn+ sons only. Data for first 9 days of progeny from 300 mothers (50/vial).

J1 and J2: y cv cm Sxlf24,M1/cm Sxlf4 v f; al dp b pr cn c px sp/+ sisters without and with Dp(1;3)sn13a1,Sxl+, respectively, ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ +/Y; al dp b pr cn c px sp/CyO. Data for progeny of 230 mothers and 50 mothers, respectively, collected for 6 days (50/vial).

K1 and K2: y cv cm Sxlf24,M1/cm Sxlf4 v f; ru h th st cu sr e ca /+ sisters without and with Dp(1;3)sn13a1,Sxl+, respectively, ♀̆♀̆ × ♂♂ +/Y; ru h th st cu sr e ca. Data for 200 and 50 mothers, respectively, (50/vial). K1 progeny were collected for 9 days, while K2 progeny were collected over the same period, but progeny from days 3, 6, and 7 were not scored.

Progeny scored are those on which the recombination rate calculations were made. Unless otherwise stated, progeny were from the first 10 days of laying.

As a comparison between crosses A1 and B in Table 2 shows, recombination across the y-sn interval on the X chromosome of SxlM6,f3/Sxlf4 mutant females was reduced but not eliminated (the origin of SxlM6,f3 is described in materials and methods). The rate of X chromosome nondisjunction was concomitantly elevated, but not nearly to the 30% level reported previously for infected Sxlf4 females (Starr and Cline 2002). Neither of these meiotic parameters was significantly affected by Wolbachia (compare A2 with A1), whether the data for the 12 mothers in each group were pooled (P > 0.06 by χ2), or whether each female was considered individually (P > 0.3 by the Mann–Whitney test). As is typical when meiotic recombination is only partially blocked by mutations in Sxl, the observed map distance varied considerably among individual females of the same genotype. In this case the y-sn distance ranged from 4.7 to 1.0 cM for uninfected females vs. from 4.6 to 0.9 cM for infected.

Because the y-sn distance for SxlM6,f3/Sxlf4 females carrying a Sxl+ allele was significantly lower (71%) than the “book value” of 21 cM (Table 2, cross B), we wondered whether one or the other of these two Sxl mutant alleles might have a modest dominant effect on meiotic recombination. The data in part 2 of Table 2 show that SxlM6,f3 does. While the y-ct distance for SxlM6,f3/+ females (C1) was 68% of the book value—very similar to the 71% value for SxlM6,f3/Sxlf4; Dp(Sxl+)/+ females in cross B—adding another Sxl+ allele (C2) brought the value to 99% of the expected distance. The females in crosses C1 and C2 were genetically matched sisters to minimize extraneous differences in genetic background.

While Wolbachia infection had no effect on recombination, data in part 3 of Table 2 reveal that otu− did have a dominant effect in Sxl-sensitized situations, even when that sensitization was quite modest. The y-ct distance for SxlM1,f3/Sxlf18 females dropped from 3.9 cM (20% of the book value) for otu+ animals (D1) to 1.3 cM (7% of the book value) in otu−/+ animals (D2), and the rate of X chromosome nondisjunction increased eightfold (from 0.5 to 4.2%). Both effects were statistically significant (P < 0.05), whether the data for females were pooled or evaluated for individuals. Data for the genetically matched females in crosses E1 and E2 show that a dominant effect of otu− was even apparent in females that were only heterozygous for SxlM1,f3, and hence only weakly sensitized. Heterozygosity for otu− reduced the y-ct distance from 68% of the book value to 33% and increased the X nondisjuction rate from <0.1 to 1.7%. While SxlM1,f3 and SxlM6,f3 exhibited weak dominant effects on recombination, Sxlf18 (cross F) did not (97% of the book value distance). Moreover, otu− had no dominant effect on meiotic recombination in a Sxl+ genetic background, as shown in crosses G1 and G2. For reasons that are unclear, the y-ct distance for the wild-type control (G2) in this experiment was only 60% of the book value, but the distance for the genetically matched otu−/+ females (G1) was essentially identical (99%) to the distance for the control (G2).

In summary, the effect of Wolbachia on Sxl functioning appears to be specific for cystocyte proliferation and thus does not appear to reflect a general effect on Sxl germline activity. In contrast, the effect of otu− on Sxl germline functioning does appear to fit the “general reduction” model, since it dominantly interferes with both cystocyte proliferation and meiotic recombination activities of Sxl.

Recombination on the X chromosome is more sensitive than on autosomes to a reduction in Sxl activity:

The magnitude of the meiotic defect in Wolbachia-infected Sxlf4 females is shown in part 4 of Table 2 (cross H). For the X, no recombinants were recovered over the 55.2 cM (book distance) w-f interval examined, and the rate of X chromosome nondisjunction was extremely high (30%). Knowing that Wolbachia does not affect meiosis, we can conclude that these meiotic defects are due to Sxlf4 rather than some peculiarity of the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction. Recombination on chromosome II of the same animals (al-sp; 107 cM book distance) was also strongly reduced, but surprisingly the reduction was an order of magnitude less severe than that for the X.

Since Wolbachia seems to discriminate between the cystocyte proliferation and meiotic germline functions of Sxl, we wondered whether mutations in Sxl could also make that distinction. Sxlf24 seems to (the origin and molecular nature of Sxlf24,M1 are described in materials and methods). Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4 female fecundity was 30 times higher than that for Wolbachia-suppressed Sxlf4/Sxlf4 females, and indeed 23% higher than that of their sisters carrying the large Sxl+ chromosomal duplication Dp(1;3)sn13a1 (data not shown). The high fecundity of Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4 females shows that Sxlf24,M1 complements the cystocyte proliferation defect of Sxlf4, but data in part 5 of Table 2 show that it does not complement the Sxlf4 meiotic defect. Crosses J1 and K1 in Table 2 show that recombination over the y-f interval on X in Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4 females was <0.5% that of their control sisters who carried a Sxl+ allele (crosses J2 and K2), and X chromosome nondisjunction was correspondingly high (24%). Again recombination on chromosome II was also drastically reduced, but by an order of magnitude less than that on X. Crosses K1 and K2 show that meiotic recombination on chromosome III, the only other major autosome, was also less sensitive than that on X to Sxl mutations, and by approximately the same amount as chromosome II.

Like mutations in many other meiotic genes (Baker et al. 1976; Sekelsky et al. 1999; Page et al. 2000), mutations in Sxl reduce recombination in a polar fashion, with centromere-proximal recombination being affected less than centromere distal; however, this polarity effect cannot account for the greater reduction in X chromosome vs. autosome recombination described above. The al-b, b-c, and c-sp intervals together span chromosome II, with b-c spanning the centromere and hence being the most centromere proximal. Polarity is illustrated by the fact that recombination in Sxlf24,M1/Sxlf4 females over the b-c interval relative to that for their sisters carrying Sxl+ was 10.6%, in contrast to 2.5 and 2.2% for the centromere-distal al-b and c-sp intervals, respectively. The y-f interval on X, like the al-b interval on II, begins only a few hundred kilobases from the telomere and runs three-fourths of the way to the centromere; hence, polarity effects should be similar for the two segments. Nevertheless, even though the y-f segment includes slightly more (25%) DNA than the al-b segment, recombination across the y-f segment in the mutant vs. the Sxl+ control was fivefold lower than across the al-b autosomal segment. The same pattern held for chromosome III (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Since suppression of the Sxlfs mutant ovarian-tumor phenotype by Wolbachia is so striking, it is perhaps surprising that infection has so little apparent effect on gene expression in young wild-type ovaries, at least as measured by microarray analysis of transcript levels. Even the most robust effect we detected—a 50% reduction for all three yolk genes—was only apparent because we had examined RNA from very young adult ovaries that had no egg chambers older than stage 7. Yolk first becomes visible in egg chambers just a few hours later in stage 8, but by this time the level of yolk gene expression in the ovary has increased 10–15 times and effects on it by Wolbachia are no longer detectable. Of course, transcript levels are only one measure of the molecular effect this endosymbiont might have on its host, and the sensitivity of microarray analysis to changes in those levels is relatively limited.

Although the magnitude of the yolk gene effect was relatively small, we can be confident in its validity because the comparisons that revealed it were between flies whose only genetic or environmental difference was their infection status. Moreover, the effect was apparent in a variety of different genetic backgrounds, and in tumorous as well as nontumorous egg chambers. The fact that yolk gene expression in the ovary occurs only in somatic cells (Bownes 1994) helps account for the observation that the effect of Wolbachia was so similar for tumorous and nontumorous egg chambers. That similarity suggests that at least some aspects of the development and physiology of the gonadal soma at this previtellogenic stage are independent of the developmental status of the germ cells that it encloses.

This small effect of Wolbachia on early yolk gene expression seems most likely to reflect a minor metabolic load that the endosymbiont imposes on its host that slightly delays maturation of developing egg chambers. The delay may be too brief to be readily detectable by morphological criteria, yet have a relatively robust effect on yolk gene expression in previtellogenic ovaries because it occurs at a time when yolk gene expression is just beginning to increase exponentially. It seems unlikely that the effect is relevant to suppression of Sxlfs mutant alleles. If nonspecific stress could mimic suppression of Sxlfs alleles by Wolbachia, suppressors of Sxlfs mutants would be common. Although mutations that closely mimic the effect of Wolbachia on the Sxlfs phenotype can be generated, they are certainly not frequent (Bopp et al. 1999; T. W. Cline, unpublished data). If the yolk gene effect reflects only a minor delay in oocyte maturation, one could imagine that a variety of unrelated genetic changes that also caused a small delay in egg chamber maturation might be epistatic to it. Such a masking effect of undefined differences in genetic background may account for the one situation in which we failed to see a significant yolk gene effect. Subtle though it may be, the yolk gene effect does add to the list of Wolbachia phenotypes reported for D. melanogaster.

The Wolbachia–Sxl interaction proved to be specific for the earliest germline function of Sxl, that which enables terminally differentiating cystocytes to exit their proliferative growth phase. As the experiments here show, Sxl functions later to control meiotic recombination, but Wolbachia has no effect on that process. The functional specificity of the Sxl–Wolbachia interaction contrasts with that for the Sxl–otu interaction, an interaction that may involve all Sxl germline activities.

The data presented here are the first to show in a primary data article that mutation of Sxl by itself can interfere with meiosis, hence they rigorously establish a requirement for Sxl in meiotic recombination. The claim by Bopp et al. (1999) to have demonstrated such a requirement on the basis of the observation that Sxlfs mutations reduce recombination was complicated by the fact that they could only observe meiotic effects for these otherwise sterile mutant females if fertility was partially restored by suppressor mutations of unknown nature. These authors believed that because those suppressor mutations had no effect on recombination in a Sxl+ genetic background, the meiotic effects observed in an Sxlfs background must be due solely to the Sxlfs alleles. While this possibility is plausible, it is not demanded by the data in the absence of information on the molecular basis for suppression or information on whether the suppressor mutations have no meiotic effect in genetic backgrounds sensitized by mutations in other meiotic genes. As additional evidence for their conclusion, these authors cited their observation that a reduction in germline SXL immunostaining caused by mutations in the virilizer gene correlated with a meiotic effect; however, no evidence was presented to establish a causal relationship.

A surprising aspect of our results was the discovery that the meiotic effects of Sxl mutations can be at least fivefold stronger for the X chromosome than for comparable regions of the autosomes in the same individual. Interestingly, the meiotic machinery in Caenorhabditis elegans has been shown to discriminate strongly among different chromosomes (Phillips and Dernburg 2006).

Many reports have suggested that Sxl and otu may have closely related functions in the germline (reviewed by Oliver 2002; Casper and Vandoren 2006), but because the two most convincing arguments on this point in the literature have not held up, the data presented here are now the most compelling. We could not confirm the claim by Bae et al. (1994) that the gain-of-function allele SxlM1 restored fertility to otu13 mutant females whose ovaries would otherwise have been mostly tumorous. Indeed, we discovered that the SxlM1otu13 chromosome sent us by these authors did not carry otu13, but instead a much weaker allele that allowed some fertility even in a Sxl+ background (data not shown). Moreover, we saw no effect on the otu13 phenotype even by SxlM8, a fully constitutive allele much stronger than SxlM1 (data not shown). SxlM8 carries a 123-bp deletion of the Sxl male exon 3′ splice site that locks the allele into its feminizing expression mode (Barbash 1995).

A second seemingly compelling observation arguing that otu regulates Sxl in the germline was the observation that otu mutations blocked expression of female SXL protein in ovaries (Bopp et al. 1993; Oliver et al. 1993). But Hinson and Nagoshi (2002a) showed that this apparent block was due to a developmental arrest of otu mutant female germ cells at the one point in oogenesis where female SXL protein cannot be detected by in situ immunostaining even in wild-type ovaries. Stronger otu alleles that blocked germ cell development earlier did not eliminate SXL protein.

A limitation of previous studies of the regulatory relationship between Sxl and otu is that they relied on recessive effects of otu mutants measured in situations where the development of the ovary was grossly abnormal and the phenotype very sensitive to uncharacterized aspects of the genetic background (see Hinson and Nagoshi 2002b). In contrast, the effects of otu− described here are dominant and occur in situations where functional eggs are made by one or both of the two genotypes compared. The molecular nature of the Sxl–otu relationship remains to be determined, but the fact that SXL protein is apparent even in a null otu background (Hinson and Nagoshi 2002b) argues that otu+ is required for SXL product function, not for Sxl regulation (even autoregulation). Effects by otu on the transport and/or localization of Sxl RNA targets is one attractive possibility (Tirronen et al. 1995; Keyes and Spradling 1997; Goodrich et al. 2004.

Our failure to find a large effect of Wolbachia infection on the transcript level for any Drosophila gene in young adult ovaries suggests that the molecular nature of the Wolbachia–Sxl interaction is post-transcriptional rather than transcriptional. One possibility is that Wolbachia increases the level of functional SXL in young cystocytes by displacing it from microtubules through competition for similar binding sites. Vied and Horabin (2001) proposed that SXL can only function in such cells when it is freed from a protein complex bound to microtubules. Wolbachia has been shown to be associated with microtubules (Ferree et al. 2005; Serbus and Sullivan 2007).

Acknowledgments

We thank J. L. Chow and J. Wurzle for assistance with Su(Ws), M. Bell and B. Pickle for DNA sequencing, S. Weitze for help with array techniques, and the University of California, Berkeley's Functional Genomics Laboratory for array facilities. We thank B. J. Meyer and Cline lab members for comments and discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM23468 (to T.W.C.).

Array intensity data have been submitted to the NCBI gene expression data repository (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under the accession no. GSE9274.

References

- Andrews, J., K. Bogart, A. Burr and J. Conaty, 2006. Fabrication of DGRC cDNA microarrays. CGB Technical Report 2006–12. The Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

- Bae, E., K. R. Cook, P. K. Geyer and R. N. Nagoshi, 1994. Molecular characterization of ovarian tumors in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 47 151–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, B. S., J. B. Boyd, A. T. Carpenter, M. M. Green, T. D. Nguyen et al., 1976. Genetic controls of meiotic recombination and somatic DNA metabolism in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73 4140–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash, D. A., 1995. Genetic and molecular analysis of suppressors of the Drosophila melanogaster female-specific lethal mutation sisterlessA1. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

- Bernstein, M., R. A. Lersch, L. Subrahmanyan and T. W. Cline, 1995. Transposon insertions causing constitutive Sex-lethal activity in Drosophila melanogaster affect Sxl sex-specific transcript splicing. Genetics 139 631–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bier, E., H. Vaessin, S. Shepherd, K. Lee, K. McCall et al., 1989. Searching for pattern and mutation in the Drosophila genome with a P-lacZ vector. Genes Dev. 3 1273–1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart, K., and J. Andrews, 2006. Extraction of total RNA from Drosophila. CGB Technical Report 2006–10. The Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

- Bopp, D., J. I. Horabin, R. A. Lersch, T. W. Cline and P. Schedl, 1993. Expression of the Sex-lethal gene is controlled at multiple levels during Drosophila oogenesis. Development 118 797–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bopp, D., C. Schutt, J. Puro, H. Huang and R. Nothiger, 1999. Recombination and disjunction in female germ cells of Drosophila depend on the germline activity of the gene Sex-lethal. Development 126 5785–5794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K., S. L. Dobson, H. R. Braig and S. L. O'Neill, 1998. Rescuing Wolbachia have been overlooked. Nature 391 852–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourtzis, K., M. M. Pettigrew and S. L. O'Neill, 2000. Wolbachia neither induces nor suppresses transcripts encoding antimicrobial peptides. Insect Mol. Biol. 9 635–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bownes, M., 1994. The regulation of the yolk protein genes, a family of sex differentiation genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Bioessays 16 745–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper, A., and M. VanDoren, 2006. The control of sexual identity in the Drosophila germline. Development 133 2783–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. E., C. L. Anderson, J. Cande and T. L. Karr, 2005. Widespread prevalence of Wolbachia in laboratory stocks and the implications for Drosophila research. Genetics 170 1667–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline, T. W., and B. J. Meyer, 1996. Vive la différence: males vs. females in flies vs. worms. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30 637–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline, T. W., D. Z. Rudner, D. A. Barbash, M. Bell and R. Vutien, 1999. Functioning of the Drosophila integral U1/U2 protein Snf independent of U1 and U2 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles is revealed by snf+ gene dose effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 14451–14458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaty, J., K. Bogart and J. Andrews, 2006. Direct labeling and hybridization protocol. CGB Technical Report 2006–9. The Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN.

- Dedeine, F., M. Boulétreau and F. Vavre, 2005. Wolbachia requirement for oogenesis: occurrence within the genus Asobara (Hymenoptera, Braconidae) and evidence for intraspecific variation in A. tabida. Heredity 95 394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, P. M., H. M. Frydman, J. M. Li, J. Cao, E. Wieschaus et al., 2005. Wolbachia utilize host microtubules and dynein for anterior localization in the Drosophila oocyte. PLoS Pathog. 2 111–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor, G. B., N. A. Nassif, D. M. Johnson-Schlitz, C. R. Preston and W. R. Engels, 1991. Targeted gene replacement in Drosophila via P element-induced gap repair. Science 253 1110–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich, J. S., K. N. Clouse and T. Schüpbach, 2004. Sqd and Otu cooperatively regulate gurken RNA localization and mediate nurse cell chromosome dispersion in Drosophila oogenesis. Development 131 1949–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson, S., and R. N. Nagoshi, 2002. a The involvement of ovarian tumor in the intracellular localization of Sex-lethal protein. Insect Mol. Biol. 11 241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson, S., and R. N. Nagoshi, 2002. b ovarian tumor expression is dependent on the functions of the somatic sex regulatory genes transformer-2 and doublesex. Arthropod Struct. Dev. 31 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotopp, J. C. D., M. E. Clark, D. C. S. G. Oliveira, J. M. Foster, P. Fischer et al., 2007. Widespread lateral gene transfer from intracellular bacteria to multicellular eukaryotes. Science 317 1753–1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. R., M. Mao, A. R. Jones, J. Burchard, M. J. Marton et al., 2001. Expression profiling using microarrays fabricated by an ink-jet oligonucleotide synthesizer. Nat. Biotechnol. 19 342–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, L. N., and A. C. Spradling, 1997. The Drosophila gene fs(2)cup interacts with otu to define a cytoplasmic pathway required for the structure and function of germ-line chromosomes. Development 124 1419–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateos, M., S. J. Castrezana, B. J. Nankivell, A. M. Estes, T. A. Markow et al., 2006. Heritable endosymbionts of Drosophila. Genetics 174 363–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill, S. L., R. Giordano, A. M. Colbert, T. L. Karr and H. M. Robertson, 1992. 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis of the bacterial endosymbionts associated with cytoplasmic incompatibility in insects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89 2699–2702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, B., 2002. Genetic control of germline sexual dimorphism in Drosophila. Int. Rev. Cytol. 219 1–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, B., Y.-J. Kim and B. S. Baker, 1993. Sex-lethal, master and slave: a hierarchy of germ-line sex determination in Drosophila. Development 119 897–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, B., N. Perrimon and A. P. Mahowald, 1988. Genetic evidence that the sans fille locus is involved in Drosophila sex determination. Genetics 120 159–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, S. L., K. S. McKim, B. Deneen, T. L. VanHook and R. S. Hawley, 2000. Genetic studies of mei-P26 reveal a link between the processes that control germ cell proliferation in both sexes and those that control meiotic exchange in Drosophila. Genetics 155 1757–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannebakker, B. A., B. Loppin, C. P. H. Elemans, L. Humblot and F. Vavre, 2007. Parasitic inhibition of cell death facilitates symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104 213–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C. M., and A. F. Dernburg, 2006. A family of zinc-finger proteins is required for chromosome-specific pairing and synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Dev. Cell 11 817–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presgraves, D. C., 2000. A genetic test of the mechanism of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila. Genetics 154 771–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salz, H. K., T. W. Cline and P. Schedl, 1987. Functional changes associated with structural alterations induced by mobilization of a P element inserted in the Sex-lethal gene of Drosophila. Genetics 117 221–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekelsky, J. J., K. S. McKim, L. Messina, R. L. French, W. D. Hurley et al., 1999. Identification of novel Drosophila meiotic genes recovered in a P-element screen. Genetics 152 529–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbus, L. R., and W. Sullivan, 2007. A cellular basis for Wolbachia recruitment to the host germline. PLoS Pathog. 3 1930–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr, D. J., and T. W. Cline, 2002. A host-parasite interaction rescues Drosophila oogenesis defects. Nature 418 76–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky, M., 1988. Sex determination in Drosophila: the X-chromosomal gene liz is required for Sxl activity. EMBO J. 7 3889–3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storto, P., and R. King, 1988. Multiplicity of functions for the otu gene products during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev. Genet. 9 91–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirronen, M., V. P. Lahti, T. I. Heino and C. Roos, 1995. Two otu transcripts are selectively localised in Drosophila oogenesis by a mechanism that requires a function of the otu protein. Mech. Dev. 52 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vied, C., and J. I. Horabin, 2001. The sex determination master switch, Sex-lethal, responds to hedgehog signaling in the Drosophila germline. Development 128 2649–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werren, J. H., L. Baldo and M. E. Clark, 2008. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]