Abstract

Experimental evolution of bacteriophage provides a powerful means of studying the genetics of adaptation, as every substitution contributing to adaptation can be identified and characterized. Here, I use experimental evolution of MS2, an RNA bacteriophage, to study its adaptive response to a novel environment. To this end, three lines of MS2 were adapted to rapid growth and lysis at cold temperature for a minimum of 50 phage generations and subjected to whole-genome sequencing. Using this system, I identified adaptive substitutions, monitored changes in frequency of adaptive mutations through the course of the experiment, and measured the effect on phage growth rate of each substitution. All three lines showed a substantial increase in fitness (a two- to threefold increase in growth rate) due to a modest number of substitutions (three to four). The data show some evidence that the substitutions occurring early in the experiment have larger beneficial effects than later ones, in accordance with the expected diminishing returns relationship between the fitness effects of a mutation and its order of substitution. Patterns of molecular evolution seen here—primarily a paucity of hitchhiking mutations—suggest an abundant supply of beneficial mutations in this system. Nevertheless, some beneficial mutations appear to have been lost, possibly due to accumulation of beneficial mutations on other genetic backgrounds, clonal interference, and negatively epistatic interactions with other beneficial mutations.

EXPERIMENTAL evolution, or the study of adaptation in laboratory populations, provides a means of following adaptation in real time and in minute detail. Microbial systems, in particular, offer an opportunity to rigorously test theoretical models of adaptive evolution, as in these systems beneficial mutations can be readily observed and their effects measured in a controlled environment. Recent work in this area has addressed such questions as whether theory can accurately predict the distribution of fitness effects among beneficial alleles (Sanjuan et al. 2004; Rokyta et al. 2005; Barrett et al. 2006; Kassen and Bataillon 2006) and how interference alters this distribution among fixed beneficial alleles (Hegreness et al. 2006).

Lenski and Travisano (1994) pioneered another kind of experimental evolution approach, which focuses on describing patterns of evolution in evolving lines. One generality that has emerged from these studies is that evolving populations tend to increase in fitness rapidly upon introduction to a new environment, but more slowly later (Elena and Lenski 2003). This slowdown in the rate of increase in mean fitness may be due to one of two causes or some mixture of the two. First, as a population approaches an optimal phenotype, the supply of beneficial mutations may become exhausted, and adaptation may be limited by an increasingly smaller mutation supply (Silander et al. 2007). Second, the rate of adaptation may slow if, as expected, mutations with large benefits tend to be fixed earlier than those with small benefits.

Several population genetic and physiological factors may act together to ensure that large-effect mutations are fixed before mutations with small effects, particularly in large asexual populations. First, because these mutations with big benefits have shorter sweep times than other mutations, they will tend to be among the first mutations fixed (Kimura and Ohta 1969; Gerrish and Lenski 1998; Kim and Orr 2005). This is especially true in large populations, where an abundant mutation supply offers opportunity for competition between beneficial mutations (Gerrish and Lenski 1998; Kim and Orr 2005). Second, large-effect mutations have lower probabilities of stochastic loss (Haldane 1927; Gillespie 1991; Orr 2002), and correspondingly shorter waiting times until a successful mutation occurs, than small-effect mutations. This may be particularly true in asexual populations, where successful mutations may need to have benefits large enough to overcome the effects of linked deleterious mutations (Johnson and Barton 2002). Third, diminishing returns epistasis may be common: the same beneficial mutation may have a larger effect if it occurs early in the course of adaptation rather than later (Hartl et al. 1985; Bull et al. 2000). Finally, later substitutions may be largely compensating for deleterious pleiotropic effects of earlier substitutions, and compensatory mutations may have smaller benefits on average than the mutations for which they compensate (Otto 2004). To date, only one experiment has directly examined whether or not earlier substitutions have larger benefits than later ones, independent of any reduction in the supply of beneficial mutations, with somewhat mixed results (Holder and Bull 2001).

Here, I use experimental evolution to study adaptation in large populations of an RNA phage with a high mutation rate, MS2. MS2 is a single-stranded RNA bacteriophage of the family Leviviridae (reviewed in van Duin and Tsareva 2004). Like other phage of this family, MS2 has a small genome, consisting of ∼3.6 kb and four genes (Fiers et al. 1976). As a result, repeated whole-genome sequencing can be used to determine both the identity and the order of each adaptive substitution. In this experiment, I expose MS2 to a new environment—one that selects for rapid growth and lysis in Escherichia coli growing at a colder than usual temperature—and examine its response by determining the identity and fitness effects of each substitution. Results may differ from similar studies in DNA phage (Holder and Bull 2001) due to the more abundant supply of mutations in an RNA phage. Further, the data collected here allow the investigation of patterns of evolution associated with a combination of a large population size and high mutation rates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Phage and host strains:

Phage in the genus Levivirus (family Leviviridae) consist of a single protein-coding RNA strand encapsulated by a virion coat. The coliphage of this group, including MS2, infect F+ E. coli cells through the pilus encoded by the F-plasmid. MS2 reproduces in host cells, using both its own gene products and host factors, and then lyses the host cell to release progeny phage. The small (3569 nucleotides) genome of MS2 includes four protein-coding genes: the maturase, coat, lysis, and replicase genes. The maturase gene is involved in infection and lysis; the coat protein dimerizes to form the repeating subunit that constitutes the virion's protein coat; the lysis protein aids in lysis of the host cell; and the replicase combines with host factors to form the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase that copies the viral genome (van Duin and Tsareva 2004). In addition, the MS2 genome contains regulatory regions controlling the timing of translation of the coding regions; this regulation is mediated by the secondary structure of the single-stranded RNA chromosome (Klovins et al. 1997).

For this experiment, a stock designated “MS2 ancestor” (kindly provided by J. Bollback) was obtained from a laboratory strain of MS2 (kindly provided by J. van Duin), by propagating the strain for ∼20 phage generations at 37° to preadapt it to laboratory conditions. A single plaque from this population was isolated and grown for 3 hr at 37°. The MS2 ancestor is thus clonally derived from a single phage and is expected to be largely genetically homogenous (among three sequenced genomes, 1 silent and 0 replacement differences were found; data not shown).

Phage were grown on TOP 10 F′ E. coli cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in standard Luria–Bertania medium supplemented with 14 μg/ml tetracycline (Sigma, St. Louis) to maintain the presence of the F-plasmid.

Serial passages:

Three MS2 lines were independently propagated from the MS2 ancestor stock through a minimum of 50 serial passages at 30° (cold temperature). Serial passages consisted of infection of a host culture, followed by 130 min of phage growth, and extraction of the phage from the culture. The scheme used here was designed to allow tight control of population size (phage were bottlenecked every generation), to limit host–phage coevolution (naive hosts were provided for each passage), and to limit phage–phage coevolution [interaction between phage was limited by a low multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼1 phage/100 host cells].

Each serial passage was performed as follows: uninfected E. coli cultures were grown at 37° to an optical density of 0.25–0.5 (OD measured at 600 nm, corresponding to a density of ∼2.5 × 108–5.0 × 108 cells/ml). Two 5-ml subsamples of this cell culture were physiologically adapted to growth in a 30° water bath for 20 min. One of these was infected with ∼1 × 107 phage (2.0 × 106 /ml) from the previous passage, and the other was grown alongside the infected culture and checked to confirm the absence of contaminate phage. The cultures were grown for 130 min at 30°, then E. coli cells were pelleted and removed by centrifuging for 20 min, and phage were extracted by removing the liquid lysate. Portions of this lysate were used (i) to measure the concentration of phage to determine the amount of lysate necessary for infecting the next passage, (ii) to infect the next serial passage, and (iii) to maintain a frozen “fossil record” of the evolving lines by archiving lysate in 10% DMSO at −80°. Phage concentration was estimated from the number of plaque-forming units (PFUs) in an appropriate dilution plated on host cells using a soft agar overlay method and grown overnight at 37°.

Growth assays:

I measured the growth rate of clonal phage populations containing each putatively adaptive mutation on the genetic background on which it occurred (i.e., the substitution of interest plus previous substitutions). To confirm that assayed phage had the genotype of interest with no additional mutations, I isolated and sequenced the genomes of phage from single plaques. One mutation, C3056U, could not be obtained in isolation and so was measured along with the next likely substitution, U1756A. To measure the fitness effect of each substitution, I performed ∼10 replicate growth assays under conditions that mimicked passaging conditions as closely as possible. To control for environmental variation, I used a paired design for the assays: each replicate includes a measurement of the growth rate of both MS2 ancestor and the genotype of interest taken at the same time and using the same host culture. Briefly, a single 60-ml E. coli culture was grown at 37° in a 250-ml flask to an OD of 0.25–0.5 and divided into two 25-ml cultures in 150-ml flasks, with an additional 5-ml culture used as a negative control. One of the 25-ml cultures was infected with MS2 ancestor, and the other was infected with phage of the genotype of interest. Cultures were then grown and phage extracted as in serial passages, with two exceptions. First, initial phage densities were lower (∼100 phage/ml), although in both cases phage were grown in a large excess of host cells. Second, phage were extracted using a 2-μm cellulose acetate spin filter (Costar, Cambridge, MA); in both cases, only phage outside host cells were extracted. Both changes to the protocol allowed for more accurate determination of phage numbers.

After each assay, initial (N0) and final phage numbers (Nt) were determined from the initial and final phage concentration as detailed above, except that PFU counts were replicated (one to three independent dilutions plated four to six times each). Absolute fitness is estimated from absolute growth rates,  , calculated from

, calculated from  (where t is time). Since growth rate is measured over a single cycle of phage growth (t = 1, data not shown), relative fitness is estimated as the ratio of the absolute growth rates (w or 1 + s; Crow and Kimura 1970, p. 7; Bull et al. 2000).

(where t is time). Since growth rate is measured over a single cycle of phage growth (t = 1, data not shown), relative fitness is estimated as the ratio of the absolute growth rates (w or 1 + s; Crow and Kimura 1970, p. 7; Bull et al. 2000).

RNA extraction, PCR, and sequencing:

RNA was extracted using a standard phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol protocol and precipitated in 95% ethanol with 30 mm NaOAc. This RNA was used as a template for a reverse transcription reaction [SuperScript II from Invitrogen or iScript from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA)], and the resulting cDNA was used in a PCR that amplified the genome in two overlapping fragments. PCR fragments were sequenced directly using internal primers, and sequences were analyzed using Sequencher (Genecodes). Data are deposited in the GenBank database under accession nos. FJ799467–FJ799712. All primer sequences are available upon request.

Consensus sequences, representing the whole phage population, were obtained by sequencing RNA extracted from the phage lysate of the final serial passage of each evolved line. These “whole genome” sequences include >95% of the genome, including the entire coding region (approximately from GenBank reference sequence NC%20001417, positions 94–3521). For sites where the final consensus sequence differed from the ancestral sequence, I monitored changes in allele frequency through time. To this end, I sequenced the region surrounding the sites of interest in isolates of 9–24 archived phage clones from intervals of ∼10 passages. For these sequences, which did not encompass the whole genome, plaques, representing individual phage from the evolving population, were isolated by plating as above and sequenced in one direction.

Analyses:

In this study, a substitution is defined as a mutation that occurs in passage 50 and is increasing to a frequency of 8/10, apparently, in the process of being fixed. In lines 2 and 3, the experiment was continued beyond generation 50 so that the fates of the mutations in that passage could be determined. An arbitrary cutoff of this kind was necessary due to the turnover of alleles seen in these populations (see results). Counting substitutions is complicated by two other factors: some substitutions occur in more than one line, and some occur in regions of the genome with overlapping genes. For clarity, I identify the numbers used for each calculation. The order in which each substitution was fixed was determined from the order in which mutations changed the ancestral genotype to the final genotype. This differed from the actual order of substitution due to recurrent mutation in one case (A1599G in line 2). Statistical analyses were performed using JMP IN v.5.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). MFOLD version 3.1.2 (http://mobyle.pasteur.fr/cgi-bin/MobylePortal/portal.py?form=mfold) was used to compare RNA secondary structures (Zuker 2003), using the default parameters but with the temperature set to 30°.

RESULTS

Substitutions:

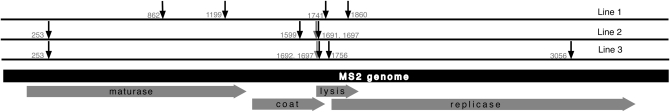

A modest number of substitutions—3 or 4—were fixed in each line of MS2 during the time course of this experiment (Figure 1). Across all three lines, a total of 11 substitutions were fixed or nearly fixed. These substitutions occurred at nine sites, with two sites experiencing parallel substitutions (253 and 1697 in lines 2 and 3). Substitutions occurred in all four MS2 genes.

Figure 1.—

Locations of substitutions and high-frequency mutations in the MS2 genome. All four genes are shown, with the direction of translation indicated by the shaded arrows. Substitutions are indicated with black arrows and high-frequency mutations with gray arrows.

Ten of the 11 substitutions fixed in these lines caused amino acid changes in at least one gene (Table 1). Two substitutions and two high-frequency mutations occurred in regions of the genome in which genes overlap. These overlapping regions have reading frames that are shifted relative to one another and thus code for different amino acid sequences (Beremand and Blumenthal 1979; Kastelein et al. 1982). Three of these mutations result in a replacement change in one gene and a silent change in the other; the remaining substitution results in a replacement change in both genes.

TABLE 1.

Major haplotypes appearing in population samples through time

| Line 1

|

Line 2

|

Line 3

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site

|

Site

|

Site

|

||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||

| 8 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 0 | ||||

| 6 | 9 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | ||||

| Passage | 2 | 9 | 1 | 0 | Frequency | 3 | 9 | 1 | 7 | Frequency | 3 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Frequency |

| MS2anc | U | A | U | A | G | A | U | A | G | C | A | G | U | U | U | A | C | |||

| 10 | . | . | . | . | 1.00 | . | . | . | . | 0.50 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.11 |

| (n = 11) | C | . | . | . | 0.50 | C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.89 | |||||

| (n = 18) | (n = 9) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | . | . | . | . | 0.64 | . | . | . | . | 0.06 | C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.40 |

| C | . | . | . | 0.36 | C | . | . | . | 0.75 | C | . | . | . | C | . | . | . | . | 0.10 | |

| (n = 11) | C | . | C | . | 0.13 | C | . | . | . | . | . | C | . | . | 0.50 | |||||

| . | . | . | G | 0.06 | (n = 10) | |||||||||||||||

| (n = 16) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | . | . | . | . | 0.21 | C | . | . | G | 0.22 | C | . | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.13 |

| C | . | . | . | 0.43 | C | . | C | . | 0.44 | C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.13 | |

| C | . | C | . | 0.36 | C | G | . | G | 0.22 | C | . | . | . | C | . | . | . | . | 0.50 | |

| (n = 14) | C | G | C | . | 0.11 | C | . | . | . | . | . | C | . | . | 0.25 | |||||

| (n = 9) | (n = 8) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 35 | . | . | . | . | 0.13 | — | — | |||||||||||||

| C | . | . | . | 0.13 | ||||||||||||||||

| C | G | C | . | 0.63 | ||||||||||||||||

| C | G | C | C | 0.13 | ||||||||||||||||

| (n = 8) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 40 | C | . | . | . | 0.09 | C | . | C | . | 0.25 | C | . | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.33 |

| C | G | C | . | 0.45 | C | G | . | G | 0.50 | C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.33 | |

| C | G | C | C | 0.45 | C | G | C | . | 0.25 | C | U | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.22 | |

| (n = 11) | (n = 8) | C | . | G | . | . | A | . | . | U | 0.11 | |||||||||

| (n = 9) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 45 | C | . | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.375 | ||||||||||

| C | U | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.5 | |||||||||||

| C | . | G | . | . | . | . | G | . | 0.13 | |||||||||||

| (n = 8) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 50 | C | G | C | . | 0.18 | C | . | C | . | 0.22 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.06 |

| C | G | C | C | 0.82 | C | G | . | G | 0.56 | C | U | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.53 | |

| (n = 11) | C | G | C | . | 0.22 | C | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.12 | |||||

| (n = 9) | C | . | G | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0.12 | ||||||||||

| C | . | G | . | . | A | . | . | U | 0.18 | |||||||||||

| (n = 17) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 60 | — | C | . | C | . | 0.17 | C | . | . | . | . | . | C | . | . | 0.20 | ||||

| C | G | . | G | 0.83 | C | . | . | . | . | . | C | . | U | 0.10 | ||||||

| (n = 12) | C | . | G | . | . | . | . | . | U | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| C | . | G | . | . | A | . | . | U | 0.60 | |||||||||||

| (n = 10) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 70 | — | — | C | . | G | . | . | A | . | . | U | 0.38 | ||||||||

| C | . | G | U | . | . | . | G | . | 0.63 | |||||||||||

| (n = 8) | ||||||||||||||||||||

Genotypes of phage at sites with high-frequency variants are shown. Numbers across the top of the table indicate the location of each site relative to GenBank reference sequence NC%20001417. The passage number indicates the number of serial passages since the experiment was initiated. Plaques isolated from the passage indicated were sequenced, representing an individual phage in the evolving population. Haplotypes shown here include only sites where mutations were fixed or occurred at high frequencies; variation in the entire sequenced region, including sites with low-frequency variants, is shown in the supplemental materials.

Substitution dynamics:

Regions of the genome that harbored substitutions were sequenced from a sample of clones from archived passages, allowing the frequency trajectories of the substitutions to be tracked through time (Figure 2). The trajectories show most substitutions increasing rapidly and at least partly independently in frequency, consistent with each having a beneficial effect. Most of the substitutions also overlap substantially, with the next substitution beginning to sweep before the previous substitution has reached fixation (Table 1). For example, in line 1, U862C begins to displace the wild-type background at around passage 20. Then U1741C, A1199G, and A1860C accumulate in rapid succession on the U862C background, and all four mutations are fixed or nearly fixed by passage 50.

Figure 2.—

Frequencies of mutations vs. passage number for (A) line 1, (B) line 2, and (C) line 3. Only mutations counted as substitutions and those that reached high frequencies are shown. Frequencies were determined by sequencing ∼10 single plaques, with each plaque representing an individual phage from the evolving populations. The identity of the mutation represented is indicated by the site number; the full sequenced region and exact sample sizes are shown in the supplemental tables.

The substitution dynamics in lines 2 and 3 are complex. In addition to overlapping sweeps as seen in line 1, line 2 showed evidence of either recurrent mutation or recombination, as mutation at site 1599 appeared on two different backgrounds at passages 40 and 50. Further, both lines 2 and 3 show the loss of high-frequency mutations (at site 1691 in line 2 and 1692 in line 3; note that the U1756A–C3056U combination may also have been in the process of being lost when the experiment ended). In each of those cases, the haplotype containing the mutation that is ultimately lost is displaced by a new haplotype, containing a different mutation (e.g., in line 2, the haplotype with mutations at sites 253-1599-1691 is displaced by 253-1599-1697; Table 1).

Fitness increase and diminishing returns:

Phage carrying all substitutions fixed in a line showed a significant improvement in fitness vs. the ancestor, as did each intermediate genotype (Table 2). The fitness of the final genotype was approximately two to three times that of the ancestral phage; thus, the average improvement per mutation ranged from 25 to 66% of the fitness of the ancestral phage.

TABLE 2.

Effect of substitutions on protein sequence and phage growth

| AGR

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Substitution | AA change | Ancestor | Derived | RGR (mean ± SE) | ||

| Anc | 81.96 | 74.17 | P = 0.2533 (n = 10) | 1.010 ± 0.146 | |||

| Line 1 | 1 | U862C | Mat: S → L | 77.10 | 120.00 | P = 0.0049 (n = 10) | 1.545 ± 0.134 |

| 2 | U1741C | Lys: F → L | 94.87 | 182.33 | P < 0.0001 (n = 10) | 1.975 ± 0.156 | |

| 3 | A1199G | Mat: H → R | 88.76 | 172.57 | P = 0.0041 (n = 10) | 2.183 ± 0.304 | |

| 4 | A1860C | Lys: E → D Rep: S → R | 68.96 | 149.58 | P = 0.0087 (n = 11) | 1.209 ± 0.285 | |

| Lines 2 and 3 | 1 | G253C | Mat: G → R | 92.82 | 152.22 | P = 0.0003 (n = 20) | 2.016 ± 0.304 |

| 2 | A1697G | Lys: Q → R Coat: silent | 73.17 | 154.93 | P < 0.0111 (n = 10) | 2.346 ± 0.267 | |

| Line 2 | 3 | A1599G + A1697G | Coat: I → V | 104.50 | 241.72 | P = 0.0006 (n = 10) | 2.899 ± 0.631 |

| — | A1599G + U1691C | 74.13 | 215.52 | P < 0.0001 (n = 10) | 3.458 ± 0.444 | ||

| Line 3 | 3 + 4 | U1756A + C3056T | Lys: Y → H Rep: silent | 98.51 | 145.16 | P = 0.0309 (n = 13) | 1.797 ± 0.397 |

| — | C1692U | Lys: silent Coat: P → S | 78.16 | 270.29 | P = 0.0002 (n = 10) | 3.833 ± 0.475 | |

The effect of substitutions and high-frequency mutations on protein sequence and growth rate is shown. Mutations are identified by ancestral nucleotide state, the location, and the derived state. Some mutations did not occur in the absence of other mutations and so are shown together. Also indicated is the gene affected and the change in amino acid sequence, if any; as MS2 has overlapping genes, some mutations affect more than one gene. Absolute growth rates (AGR) of ancestral (control) phage and phage with the specified genotype shown were compared using paired t-tests. Relative growth rates (RGR) correspond to fitness as described in the text. Note that the value for relative growth rate given is the mean across replicates of AGR-derived/AGR-ancestral and thus is not equal to the ratio of the mean absolute growth rates.

To test for a relationship between the fitness effect of a substitution and its order of substitution, I measured the effect of each substitution on the genetic background on which it occurred and investigated the relationship between the number of substitutions in a genotype and the fitness of that genotype, using data from all three lines (Figure 3). For this analysis, data from the convergent substitutions between lines 2 and 3 were used only once, and the final genotype from line 3 was considered to have four substitutions, although substitutions at sites 1756 and 3056 may have not been independent.

Figure 3.—

(A) Fitness plotted against substitution number. Each point represents the mean of ≥10 replicate growth assays performed on a single genotype. “Substitution number” is the order in which a mutation that is ultimately fixed appears. The straight line shows the best fit of a linear regression model; the curve is the best fit of a hypergeometric model [y = x0 + (a × x)/(x + b), where x0 = 1 and a and b are estimated]. (B) The magnitude of fitness “jumps” plotted against the order in which they occur. The categories on the x-axis indicate which fitness jump is measured, e.g, the first data point is the difference in fitness between the first substitution and the ancestor.

If there are diminishing returns, with each additional substitution conferring a smaller fitness benefit, a hyperbolic model should fit the fitness data better than a linear model. The number of substitutions and mean relative fitness show a positive linear relationship (with wanc constrained to one, P = 0.0004). The hyperbolic model fits the data well (Figure 3A): The Akaike information criterion (AIC) suggests that it is close to four times more likely than the linear model [AICc (linear) = −7.9371, AICc (hyperbolic) = −10.6135, ΔAICc = −2.6763, evidence ratio = 0.26232], and a standard F-test suggests that the hyperbolic model is a significantly better fit (F = 9.0646, P = 0.01964). I performed an additional test for an effect of substitution number on the magnitude of fitness jumps; under diminishing returns, each new substitution should result in a smaller fitness increase. Linear regression shows the expected negative relationship between substitution number and fitness increase (Figure 3B; r2 = 0.7250, P = 0.0073). This remains true even if the effects of the later substitutions were constrained to be equal to zero (the measured effect was slightly negative, but not significantly different from zero; r2 = 0.6413, P = 0.0169).

Phenotypic basis of adaptation:

A disproportionate number of substitutions occur in the lysis gene. Although this gene comprises <7% of the MS2 genome, it experienced roughly half of all substitutions and high-frequency mutations (6/11) (Yates-corrected χ2 = 35.18, d.f. = 1, P < 0.0001, comparison between the lysis gene and the rest of the genome).

DISCUSSION

Substitutions and high-frequency mutations are adaptive:

While the growth assays performed show that all genotypes were substantially and significantly fitter than the ancestral genotype, the data from these assays are too noisy to show that each individual substitution improves fitness. However, most substitutions do appear adaptive: with one exception, all increase rapidly and independently in frequency, as expected if they are being fixed by directional selection (Figure 2). The exception is one of the pair of mutations (U1756A and C3056U), which are nearly always found together; it may be that only one of these is beneficial, and the other is a neutral “hitchhiking” mutation. However, neither one is an especially likely candidate for the neutral mutation, as U1756A appears to have a beneficial phenotypic effect (see below), and C3056U occurs on more than one background (Table 1). Consistent with the hypothesis that the substitutions are adaptive, many are parallel with substitutions or polymorphic mutations in other lines: two substitutions were shared between lines 2 and 3, and eight of the nine sites that experienced substitutions in one line were polymorphic in another line (supplemental tables).

Diminishing returns between fitness and substitution number:

I investigated the possibility that large-effect beneficial mutations tend to be fixed earlier than those with smaller effects, a factor that might contribute to the general observation that fitness increases become smaller later in adaptation (Elena and Lenski 2003). For the three lines in this experiment, large-effect beneficial mutations did appear to be fixed earlier than those with smaller effects. Holder and Bull (2001) also found a diminishing returns relationship between mean fitness and substitution order in one of two DNA phage species investigated (results from the other were complicated by an environmental change). Although the results from these previous experiments are not entirely conclusive, they suggest a trend for diminishing returns on fitness gains per beneficial substitution, independent of any change in beneficial substitution rate.

Several factors probably play a role in ensuring that small-effect mutations are not among the first fixed. Since these populations are large and mutation rates are high, more than one copy of a particular mutation is likely to occur each generation. Stochastic loss of every copy of a mutation thus probably affects only mutations with small beneficial effects (and correspondingly high probabilities of loss), as other mutations recur frequently enough in the first few generations to overcome their probabilities of loss (Wahl and Krakauer 2000). Even if there are many more mutations of small than of large effects, so that some small-effect mutations are among the first to overcome stochastic loss, competition between mutations ensures that the first mutation fixed is of relatively large effect (Gerrish and Lenski 1998; Kim and Orr 2005; Hegreness et al. 2006).

Role of clonal interference:

As discussed above, clonal interference probably plays a role in causing the loss of mutations with small beneficial effects, at least when competing with large-effect mutations. It may also cause the loss of mutations that had large enough benefits to reach high frequencies before their subsequent loss, as seen in both lines 2 and 3 (Table 1). In all cases, the lost mutations were displaced by another mutation in complete negative linkage disequilibrium. Such a pattern suggests competition between the mutations, which might be due to clonal interference (Fisher 1930; Muller 1932; Gerrish and Lenski 1998), but can also be caused by negative epistasis. Negative epistasis, in which the double mutant is not fixed because it is not beneficial, has been implicated in the loss of mutations in other experiments (Lehman and Joyce 1993; Holder and Bull 2001). This kind of interaction is particularly likely to be implicated in competition between one pair of mutations, U1691C and A1697G, as these mutations appear to have redundant functional effects (see below).

Because these populations have large Nu, recurrent mutation may play a role similar to recombination, allowing sweeps of beneficial mutations that overlap and allowing beneficial mutations that would otherwise be lost due to clonal interference to instead be fixed (Kim and Orr 2005; Bollback and Huelsenbeck 2007; Desai et al. 2007). Consistent with the dynamics expected in a high Nu population (Kim and Orr 2005; Desai et al. 2007), almost all of the sweeps seen here overlap, with multiple beneficial mutations accumulating in a genotype before it becomes fixed (Figure 1). Similarly, recurrent mutation apparently occurred in one case, allowing fixation of a beneficial mutation that might have been otherwise lost (line 2, site 1599; Table 1). Although formally possible, it is unlikely that this event reflects recombination (see calculations in Bollback and Huelsenbeck 2007, and note that the rate of co-infection in the present experiment is lower). Further, this site clearly experiences recurrent mutation in line 3, where two different versions appear (A1599C and A1599G; supplemental Table 3).

Overall, the substitution dynamics seen here suggest that while some low-frequency mutations are lost via clonal interference, promoting a diminishing returns relationship between substitution order and fitness effect, clonal interference is probably not the cause of the loss of mutations with large benefits. Instead, it seems that beneficial mutations in this system likely recur frequently enough to compensate for the lack of recombination (Kim and Orr 2005; Desai et al. 2007).

Paucity of hitchhiking:

One interesting finding is that these lines fixed few hitchhiking mutations: with the high mutation rate characteristic of RNA phage, it would seem reasonable to expect that a genome carrying a successful beneficial mutation might also carry a suite of hitchhiking neutral mutations. Note that, with a mutation rate of u = 1.5 × 10−3 and a genome size of L = 3569, an average of 5.4 mutations are expected per replication per genome. Moreover, some sweeps do not begin until late in the experiment, at which point they may have had as many as 30 generations to accumulate neutral mutations. If any substantial fraction of these mutations are neutral [or even somewhat deleterious (Johnson and Barton 2002)], it would seem that hitchhiking mutations would be common.

Inspection of the genotyping data, however, reveals few potential cases of hitchhiking, with the possible exception of U1756A or C3560T discussed previously (Table 1). One explanation is that the viral genome is highly constrained, so that few mutations are neutral or mildly deleterious, which is not unreasonable given MS2's compact genome and the functional role played by RNA secondary structure. Simple calculations reveal that another factor probably contributes to the lack of hitchhiking, at least for the initial substitutions: given the large population size and high mutation rate, the observed sweeps probably consist of multiple occurrences of the beneficial mutation on independent backgrounds, so that no single set of neutral mutations hitchhikes to fixation [i.e., these are “soft sweeps” (Pennings and Hermisson 2006)]. Even under conservative assumptions (where all other mutations are lethal), there are multiple independent occurrences of each beneficial mutation; with N = 107 and u and L as before, ∼70 occurrences of each beneficial mutation are expected to occur on a “clean” background every generation (Charlesworth et al. 1993).

It is tempting to argue that either N or u is overestimated, and high levels of constraint constitute the sole explanation for the lack of hitchhiking. Consider, though, that to render soft sweeps unlikely, N would have to be overestimated by almost two orders of magnitude, although population size in this experiment was tightly controlled (phage were bottlenecked to 107 every generation). Further, with high levels of constraint, a smaller mutation rate increases the probability of soft sweeps, as in that case more beneficial mutations occur on deleterious mutation-free backgrounds (e.g., with u = 0.00015, ∼880 copies occur). In addition, the rapid rise in frequency of the initial substitutions also suggests soft sweeps. Using standard population genetic equations (Haldane 1924), I estimated the fitness value required to explain the observed rate of increase: starting with multiple copies of the favorable allele, the required fitness values for U862C and G253C are 1.76 and 2.11, respectively, close to the measured values of 1.55 and 2.02 (Table 2). If the mutations instead start from one initial copy, the necessary fitness values are much higher, 5.50 and 6.46.

Conditions for soft sweeps also seem likely to persist beyond the initial substitutions. Because sweeps overlap in this system, with later sweeps starting before earlier substitutions are fixed, later mutations must occur in the effectively smaller population already containing the first substitution. Nevertheless, later mutations still seem likely to recur frequently enough to also yield soft sweeps; in line 1, for example, with U862C at a frequency of 30%, at least 20 occurrences of U1741C on a deleterious mutation-free background are expected. Conditions for soft sweeps may not be favorable throughout the entire experiment, however, as eventually the accumulation of deleterious mutations may lower Ne enough so that the probability of soft sweeps declines (Johnson and Barton 2002).

If mutations recur frequently, however, it is difficult to explain why U862C was the first mutation fixed in line 1. The mutation at site 253 should have occurred several times, is not likely to have been lost stochastically, and should have displaced U862C due its apparent stronger fitness effect (Gerrish and Lenski 1998). One possibility is that the mutation at G253C was displaced by a combination of U862C and another mutation (e.g., U862C + U1741C has fitness similar to that of G253C). Data from site 253 were not captured in the genotyping frequencies in line 1; it may be that G253C occurred at high frequency in passages 10–20, but was displaced by the combination of U862C + U1741C starting in passage 30 (Figure 2A). This kind of scenario has been studied theoretically by Desai et al. (2007) and found to be plausible for large Nu populations.

Phenotypic basis of adaptation:

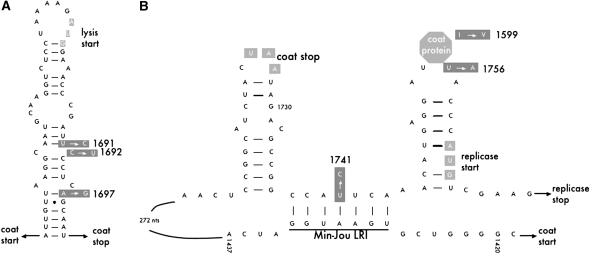

In MS2, gene expression is intricately regulated at the translational level in a manner that ensures that coat protein is expressed early and at a high level relative to the other three proteins. Expression of the lysis gene is controlled by an RNA secondary structure, so that it is coupled to coat protein translation, delaying lysis until after substantial levels of coat protein have accumulated. This structure acts by blocking ribosome binding to the lysis start; however, it can be physically disrupted by ribosomes reaching the coat gene's stop codon and scanning backward toward the lysis start. In this way, ∼5% of ribosomes translating the coat gene also translate the lysis gene (Min Jou et al. 1972; Kastelein et al. 1982; Berkhout et al. 1985, 1987). Less stable versions of the RNA secondary structure yield earlier lysis; more stable versions block lysis expression altogether (Schmidt et al. 1987).

Three mutations in this experiment affected this secondary structure region (U1691C, C1692U, and A1697G). Two (U1691C and A1697G) disrupt stem pairs, yielding lower stability structures and thus likely increasing lysis expression (MS2 ancestor, ΔG = −117.13; U1691C, ΔG = −114.85; A1697G, ΔG = −116.83 for the region from GenBank accession no. NC001417 from positions 1427 to 1744 from Klovins et al. 1997). Interestingly, the predicted structure of the double mutant is much less stable (U1691C + A1697G: ΔG = −114.75), possibly yielding a structure that would result in cell lysis before sufficient numbers of progeny phage have been formed. Consistent with the double mutant being deleterious, the two mutations never occur together in the same individual, although both reach high frequencies (Table 1). The remaining mutation (C1692T) occurs only on the A1697G background and does not appear to further affect stability (A1697G + C1692U: ΔG = −116.83), but perhaps compensates for some effect of A1697G.

The regulation of the replicase gene also appears to have been affected by mutations that increase expression, in at least two ways (Figure 4B). First, as in the lysis gene, ribosomes are prevented from binding to the replicase start by an RNA secondary structure (reviewed in Lodish 1976), and one mutation (U1741C) disrupts a base pair in this inhibitory secondary structure. Previous experimental work shows that similar mutations significantly elevate replicase expression (van Himbergen et al. 1993). Second, the replicase gene is inhibited by high levels of coat protein via coat protein binding that stabilizes an inhibitory hairpin RNA structure upstream of the replicase gene (Lodish 1976). This protein–RNA interaction is a model for protein–aptamer binding and thus has been extraordinarily well studied (e.g., Lim and Peabody 1994; Valegard et al. 1994; Grahn et al. 2000). One mutation in this experiment (U1756A) occurs in the RNA hairpin region and reduces coat protein binding, shown via both protein crystallography experiments and binding assays (Lim et al. 1994). A second mutation may have a similar effect: A1599G is a radical amino acid change in the coat protein at a residue lying between two amino acids directly involved in RNA binding (Peabody 1993) and thus may weaken binding via conformational effects in the protein. Hence, all three mutations (U1741C, U1756A, and A1599G) appear likely to elevate replicase expression through either cis- or trans-acting mechanisms.

Figure 4.—

Mutations in regulatory regions of MS2. (A) Three mutations in the region containing the RNA secondary structure regulating lysis expression. This structure overlaps coding regions of both the coat and the lysis genes and in its folded state prevents ribosomes from binding to the lysis start. The structure can be disrupted, however, allowing lysis translation, by ribosomes translating the coat gene. The three adaptive mutations in this region are indicated by arrows pointing from the ancestral nucleotide to the derived state. (B) Two nucleotide mutations and one amino acid mutation in regions involved in regulation of the replicase gene. Two local RNA secondary structures, the coat protein (which translationally represses replicase) and a long-range RNA interaction (the Min-Jou LRI) are shown. The RNA structures initially prevent ribosomes from binding to the replicase start, but ribosomes translating the coat gene disrupt the structure shown, causing the region to reform into a different configuration that allows translation of the replicase gene. As coat protein concentration increases, it binds to the rightmost secondary structure shown here, stabilizing the inhibitory conformation of the region and preventing further replicase translation. (See text for citations.)

The mutations for which phenotypic effects can be inferred, then, appear to affect MS2's fitness through altering regulation of the lysis and replicase genes. The expression level of both the lysis and the replicase genes is ordinarily likely to be under stabilizing selection, with optimal expression at an intermediate level. In the case of the lysis gene, an optimal lysis time allows phage to balance the definite benefits of linear growth inside the host with the possibility of exponential growth through infection of new hosts (Bull et al. 2000; Abedon et al. 2003). Similarly, phage growth is maximized when replicase is expressed at an intermediate level, probably because excess replicase protein inhibits coat gene translation and may poison host cells (van Himbergen et al. 1993). In this experiment, selection for increased expression of both genes appears to be because the period of phage growth in each serial passage was shorter than the wild-type lysis time (growth curves of the ancestor phage show lysis occurring after 130 min for seven of nine replicates, data not shown). As phage trapped still inside the host cells were discarded at the end of a passage, there was strong selection on phage to replicate quickly and lyse cells early.

Summary:

In this work, I investigated adaptation in a laboratory population of the RNA phage MS2. In the short time course of the experiment (50–70 phage generations), substantial adaptation occurred, involving a modest number of substitutions. These substitutions were almost entirely replacement changes and collectively increased fitness two- to threefold. The data show a trend for substitutions with larger fitness effects to be substituted earlier than those with smaller effects. Several patterns observed here, including a lack of hitchhiking neutral mutations associated with the adaptive substitutions, are likely due to the high mutation rate of RNA phage. Finally, I was able to identify some likely effects of the adaptive substitutions, including rapid lysis and higher replicase expression.

Acknowledgments

I thank C. Aquadro, N. Barton, J. Bollback, S. Collins, A. Cutter, K. Dyer, J. Fry, Y. Kim, J.P. Masly, N. Phadnis, D. Presgraves, J. Welch, and K. Zeng for helpful discussions of this work. J. Fry and C. Haag provided valuable help with the statistics, and J. Bollback provided invaluable help in the laboratory. I thank the members of the Hoekstra lab at University of California, San Diego, for their technical help and patience during the sequencing phase of this project. I thank N. Barton for pointing out the possibility of soft sweeps occurring in this system. I am especially grateful to J. Huelsenbeck for early encouragement with this work and to my Ph.D. advisor, H. A. Orr, for guidance and support. This work was funded in part by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant MCB-0075404 to John Huelsenbeck, in part by a Packard Foundation and National Institutes of Health grant GM51932 to H.A. Orr, and in part by Messersmith and Caspari Fellowships from the University of Rochester and a Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant from the NSF to A.J.B.

References

- Abedon, S. T., P. Hyman and C. Thomas, 2003. Experimental examination of bacteriophage latent-period evolution as a response to bacterial availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 7499–7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, R. D. H., R. C. Maclean and G. Bell, 2006. Mutations of intermediate effect are responsible for adaptation in evolving Pseudomonas fluorescens populations. Biol. Lett. 2 236–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beremand, M. N., and T. Blumenthal, 1979. Overlapping genes in RNA phage: a new protein implicated in lysis. Cell 18 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, B., M. H. De Smit, R. A. Spanjaard, T. Blom and J. van Duin, 1985. The amino terminal half of the MS2-coded lysis protein is dispensable for function: implications for our understanding of coding region overlaps. EMBO J. 4 3315–3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhout, B., B. F. Schmidt, A. van Strien, J. van Boom, J. van Westrenen et al., 1987. Lysis gene of bacteriophage MS2 is activated by translation termination at the overlapping coat gene. J. Mol. Biol. 195 517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollback, J. P., and J. P. Huelsenbeck, 2007. Clonal interference is alleviated by high mutation rates in large populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1397–1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull, J. J., M. R. Badgett and H. A. Wichman, 2000. Big-benefit mutations in a bacteriophage inhibited with heat. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17 942–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth, B., M. T. Morgan and D. Charlesworth, 1993. The effect of deleterious mutations on neutral molecular variation. Genetics 134 1289–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow, J. F., and M. Kimura, 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. Harper & Row, New York.

- Desai, M. M., D. S. Fisher and A. W. Murray, 2007. The speed of evolution and maintenance of variation in asexual populations. Curr. Biol. 17 385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elena, S. F., and R. E. Lenski, 2003. Evolution experiments with microorganisms: the dynamics and genetic bases of adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4 457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiers, W., R. Contreras, F. Duerinck, G. Haegeman, D. Iserentant et al., 1976. Complete nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage MS2 RNA: primary and secondary structure of replicase gene. Nature 260 500–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R. A., 1930. The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Gerrish, P. J., and R. E. Lenski, 1998. The fate of competing beneficial mutations in an asexual population. Genetica 102–103 127–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, J. H., 1991. The Causes of Molecular Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Grahn, E., N. J. Stonehouse, C. J. Adams, K. Fridborg, L. Beigelman et al., 2000. Deletion of a single hydrogen bonding atom from the MS2 RNA operator leads to dramatic rearrangements at the RNA-coat protein interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 4611–4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane, J. B. S., 1924. A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 23 19–41. [Google Scholar]

- Haldane, J. B. S., 1927. A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection, part V: selection and mutation. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 28 838–844. [Google Scholar]

- Hartl, D. L., D. E. Dykhuizen and A. M. Dean, 1985. Limits of adaptation: the evolution of selective neutrality. Genetics 111 655–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegreness, M., N. Shoresh, D. Hartl and R. Kishony, 2006. An equivalence principle for the incorporation of favorable mutations in asexual populations. Science 311 1615–1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder, K. K., and J. J. Bull, 2001. Profiles of adaptation in two similar viruses. Genetics 159 1393–1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, T., and N. H. Barton, 2002. The effect of deleterious alleles on adaptation in asexual populations. Genetics 162 395–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassen, R., and T. Bataillon, 2006. Distribution of fitness effects among beneficial mutations before selection in experimental populations of bacteria. Nat. Genet. 38 484–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastelein, R. A., E. Remaut, W. Fiers and J. van Duin, 1982. Lysis gene expression of RNA phage MS2 depends on a frameshift during translation of the overlapping coat protein gene. Nature 295 35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y., and H. A. Orr, 2005. Adaptation in sexuals vs. asexuals: clonal interference and the Fisher–Muller model. Genetics 171 1377–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, M., and T. Ohta, 1969. The average number of generations until fixation of a mutant gene in a finite population. Genetics 61 763–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klovins, J., N. A. Tsareva, M. H. De Smit, V. Berzins and J. van Duin, 1997. Rapid evolution of translational control mechanisms in RNA genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 265 372–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman, N., and G. F. Joyce, 1993. Evolution in vitro: analysis of a lineage of ribozymes. Curr. Biol. 3 723–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenski, R. E., and M. Travisano, 1994. Dynamics of adaptation and diversification: a 10,000-generation experiment with bacterial populations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91 6808–6814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, F., and D. S. Peabody, 1994. Mutations that increase the affinity of a translational repressor for RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 22 3748–3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, F., M. Spingola and D. S. Peabody, 1994. Altering the RNA binding specificity of a translational repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 269 9006–9010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodish, H. F., 1976. Translational control of protein synthesis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 45 39–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Jou, W., G. Haegeman, M. Ysebaert and W. Fiers, 1972. Nucleotide sequence of the gene coding for the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein. Nature 237 82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, H. J., 1932. Some genetic aspects of sex. Am. Nat. 66 118–138. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, H. A., 2002. The population genetics of adaptation: the adaptation of DNA sequences. Evol. Int. J. Org. Evol. 56 1317–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto, S. P., 2004. Two steps forward, one step back: the pleiotropic effects of favoured alleles. Proc. Biol. Sci. 271 705–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peabody, D. S., 1993. The RNA binding site of bacteriophage MS2 coat protein. EMBO J. 12 595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennings, P. S., and J. Hermisson, 2006. Soft sweeps II—molecular population genetics of adaptation from recurrent mutation or migration. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 1076–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokyta, D. R., P. Joyce, S. B. Caudle and H. A. Wichman, 2005. An empirical test of the mutational landscape model of adaptation using a single-stranded DNA virus. Nat. Genet. 37 441–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanjuan, R., A. Moya and S. F. Elena, 2004. The distribution of fitness effects caused by single-nucleotide substitutions in an RNA virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 8396–8401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B. F., B. Berkhout, G. P. Overbeek, A. van Strien and J. van Duin, 1987. Determination of the RNA secondary structure that regulates lysis gene expression in bacteriophage MS2. J. Mol. Biol. 195 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silander, O. K., O. Tenaillon and L. Chao, 2007. Understanding the evolutionary fate of finite populations: the dynamics of mutational effects. PLoS Biol. 5 e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valegard, K., J. B. Murray, P. G. Stockley, N. J. Stonehouse and L. Liljas, 1994. Crystal structure of an RNA bacteriophage coat protein-operator complex. Nature 371 623–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duin, J., and N. A. Tsareva, 2004. Single-stranded RNA phages, pp. 175–196 in The Bacteriophages, edited by R. Calender. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- van Himbergen, J., B. van Geffen and J. van Duin, 1993. Translational control by a long range RNA-RNA interaction; a basepair substitution analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 21 1713–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, L. M., and D. C. Krakauer, 2000. Models of experimental evolution: the role of genetic chance and selective necessity. Genetics 156 1437–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuker, M., 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]