Abstract

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) are ligand-gated ion channels that belong to the superfamily of Cys loop receptors. Valuable insight into the orthosteric ligand binding to nAChRs in recent years has been obtained from the crystal structures of acetylcholine-binding proteins (AChBPs) that share significant sequence homology with the amino-terminal domains of the nAChRs. α-Conotoxins, which are isolated from the venom of carnivorous marine snails, selectively inhibit the signaling of neuronal nAChR subtypes. Co-crystal structures of α-conotoxins in complex with AChBP show that the side chain of a highly conserved proline residue in these toxins is oriented toward the hydrophobic binding pocket in the AChBP but does not have direct interactions with this pocket. In this study, we have designed and synthesized analogues of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L], by introducing a range of substituents on the Pro6 residue in these toxins to probe the importance of this residue for their binding to the nAChRs. Pharmacological characterization of the toxin analogues at the α7 nAChR shows that although polar and charged groups on Pro6 result in analogues with significantly reduced antagonistic activities, analogues with aromatic and hydrophobic substituents in the Pro6 position exhibit moderate activity at the receptor. Interestingly, introduction of a 5-(R)-phenyl substituent at Pro6 in α-conotoxin ImI gives rise to a conotoxin analogue with a significantly higher binding affinity and antagonistic activity at the α7 nAChR than those exhibited by the native conotoxin.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs)6 belong to the superfamily of Cys loop ligand-gated ion channels, which also includes serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT3), γ-aminobutyric acid type A, and glycine receptors (1). As presynaptic heteroreceptors, nAChRs regulate the release of several important neurotransmitters, including dopamine, glutamate, and γ-aminobutyric acid. Postsynaptic nAChRs are crucial mediators of the fast excitatory cholinergic neurotransmission in the central and peripheral nervous systems, which also influence the activity in several other important neurotransmitter systems (2, 3). The nAChRs are pentameric complexes composed of combinations of α1-10, β1-4, δ, and ε/γ subunits, each consisting of an extracellular ligand binding domain, four transmembrane helices, and an extended intracellular region arranged around a central cation-conducting pore (2). Muscle-type nAChRs are composed of two α1-subunits and β1-, δ-, and ε/γ-subunits, whereas neuronal nAChRs are either heteromeric combinations of α2-6- and β2-4-subunits, α9α10 complexes, or homomeric complexes consisting exclusively of α7- or α9-subunits (4). The different nAChR subtypes are involved in a wide range of distinct physiological functions, and the vast multitude of different subunit combinations underlines the importance of developing subtype-specific ligands for nAChRs as tools for studying cholinergic neurotransmission and for determining the involvement of specific nAChR subtypes in pathological states.

α-Conotoxins are peptide neurotoxins isolated from the venom of carnivorous marine snails, and several of these have been identified as potent and selective inhibitors of specific nAChR subtypes (Table 1) (5). They are competitive antagonists acting at the orthosteric site (i.e. the binding site for the endogenous agonist) of the nAChR. Several α-conotoxins have shown promising therapeutic potential, the most prominent example being α-conotoxin Vc1.1 (also known as ACV1), which is currently undergoing clinical development for the treatment of neuropathic pain (6, 7). Structurally, α-conotoxins are relatively small in size (12-19 amino acid residues), and each peptide exhibits a well defined consensus fold containing a 310 helical region stabilized by two disulfide bonds giving rise to two loops of intervening amino acid residues denoted m and n, respectively (Fig. 1, A and B). The diversity of the amino acid residues within the m and n loops gives rise to the unique selectivity profiles displayed by the different α-conotoxins at the various nAChR subtypes. Another important structural feature of the α-conotoxins is the presence of a proline residue at a conserved position in the m loop (Table 1). In the majority of the α-conotoxins, this is the sixth residue, which we refer to as Pro6 in this study. Pro6 exists in the trans conformation and is conserved in nearly all α-conotoxins, the most notable exception being α-conotoxin ImII, which contains an arginine residue at this position. Pro6 is believed to induce the 310 helical turn in the peptide backbone exhibited by all α-conotoxins isolated to date (8). In support of this role, substitutions of the residue with amino acids such as alanine have been found to lead to a dramatic loss of the nAChR activities of the α-conotoxins (9-14). Extensive mutational studies of amino acid residues in α-conotoxins, as well as in nAChRs, have identified residues important for receptor/ligand interactions (2, 15, 16). However, the understanding of the structural basis of α-conotoxin binding to nAChRs has increased considerably in recent years with the published x-ray crystal structures of acetylcholine-binding proteins (AChBPs) in complex with various α-conotoxins ligands, including ImI and PnIA[A10L,D14K] (17-19). Additionally, AChBP was used to aid in the discovery of α-conotoxin TxIA, and a co-crystal structure of its more potent analogue TxIA[A10L] has been reported recently (20).

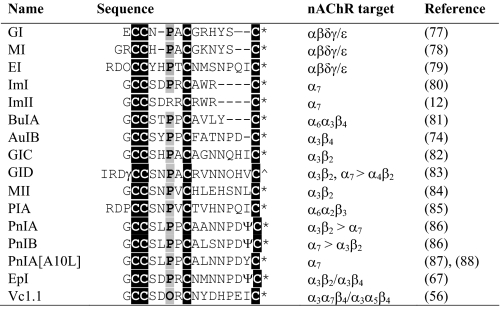

TABLE 1.

Selected α-conotoxins targeting neuronal nAChRs

For all α-conotoxins, the disulfide connectivity is 1-3, 2-4. O is

4-(R)-hydroxyproline; γ is γ-carboxyglutamic acid; ϕ

is sulfated tyrosine. * denotes C-terminal carboxamide;

denotes C-terminal

carboxylic acid.

denotes C-terminal

carboxylic acid.

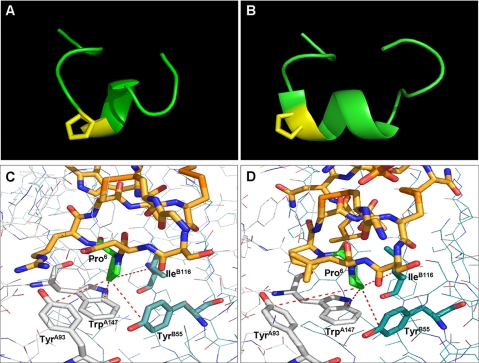

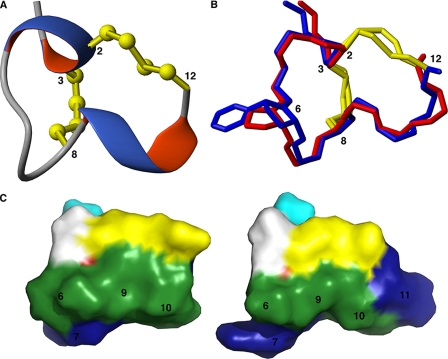

FIGURE 1.

A, three-dimensional NMR structure of α-conotoxin ImI (75); B, x-ray crystal structure of α-conotoxin PnIA (76) showing the consensus fold of α-conotoxins. The Pro6 residue is highlighted in yellow. C, three-dimensional crystal structure of α-conotoxin ImI; D, [A10L]-PnIA bound to Ac-AChBP showing the interactions of these ligands to AChBP. The conotoxins are shown in yellow, and the two chains of AChBP are shown in gray and blue, respectively. Residues that form the hydrophobic binding pocket are indicated.

AChBPs are water-soluble proteins isolated from various aquatic snails, and x-ray crystal structures of AChBPs from Lymnaea stagnalis (Ls-AChBP) (21), Bulinus truncatus (22), and Aplysia californica (Ac-AChBP) (23) have been reported. AChBPs display significant amino acid sequence homology with the amino-terminal ligand binding domain of nAChRs, and AChBPs form stable pentameric complexes characterized by binding affinities for nAChR ligands comparable with those exhibited by the homomeric α7 nAChR, hence they serve as good models for this receptor (24, 25), as well as other members of the Cys loop ligand-gated ion channel family (26-30). Interestingly, nAChR ligands have been shown to display different binding affinities for AChBPs from different species. For instance, α-conotoxin ImI exhibits a 16,000-fold greater affinity for the Ac-AChBP over Ls-AChBP (23).

α-Conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] are subtype-selective antagonists of the α7 nAChR, and for this reason both were selected for this study. Each differ in the number of amino acids in their m loop, with α-conotoxin ImI containing four and three amino acids, respectively, whereas α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] contains four and seven residues in each respective loop. X-ray crystal structures of the two conotoxins complexed to Ac-AChBP indicate that the ligands inhibit α7 nAChR signaling via binding to the orthosteric sites at the interfaces of two subunits in the pentameric receptor complex, with the central α-helical region of the peptide protruding deep into the ligand-binding site (Fig. 1, C and D) (17-19). A closer examination of the Ac-AChBP-α-conotoxin complexes reveals an open C loop and a cluster of hydrophobic residues consisting of Tyr93A and Trp147A in one subunit and Tyr55B and Ile116B in the adjacent subunit that forms the core of the ligand-binding site. Although α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] forms primarily hydrophobic contacts in the binding pocket, α-conotoxin ImI forms an important salt bridge between Arg7 of α-conotoxin ImI and Asp197A in the primary subunit of the receptor (31). In contrast to most other nicotinic ligands, α-conotoxins do not form hydrogen bonds or cation/π interactions with Trp147A, and they protrude less deeply into the pocket in comparison with ligands such as nicotine, lobeline, and methylcaconitine (MLA) (18). The aromatic cluster of the binding pocket is in close proximity to the conserved Pro6 residue, yet the proline residue does not appear to make any specific contacts in this area (Fig. 1, C and D).

This study investigates the structure-activity relationships of two series of analogues of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] containing substituted proline derivatives in position 6 to gain further insights into the importance of the Pro6 residue in the two conotoxins with respect to their binding to nAChRs. After examination of the binding mode of α-conotoxins to the AChBPs, we hypothesize that additional interactions between α-conotoxins and the residues in the hydrophobic binding pocket of the nAChR could be achieved by incorporating a substituent into Pro6. In turn, this could result in α-conotoxin analogues with higher binding affinities and improved antagonistic potencies at the α7 nAChR. Furthermore, we have investigated the structural effects of various substituents on different positions on the Pro6 side chain and their impact on conformational and folding patterns of α-conotoxins by circular dichroism and NMR spectroscopy. Finally, we evaluated these observations in a structural context by generating a homology model of the orthosteric ligand-binding site of α7 nAChR and docking the α-conotoxin analogues into this model.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Fmoc-4-(R)-(tert-butyl-hydroxy)proline, Fmoc-4-(R)-phenylproline, Fmoc-4-(S)-phenylproline, Fmoc-5-(R)-phenylproline, Fmoc-4-(R)-benzylproline, Fmoc-4-(R)-2-naphthylmethylproline, and Fmoc-4-(S)-fluoroproline were purchased from NeoMPS (Strasbourg, France), Fmoc-3-(S)-phenylproline and Fmoc-4-(R)-fluoroproline were purchased from Anaspec (San Jose, CA). Fmoc-4-(R)-(Boc-amino)proline and Fmoc-4-(S)-(Boc-amino)proline were synthesized from Cbz-4-(R)-hydroxyproline (Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland) according to the method of Tamamura et al. (32). Fmoc-4-(R)-(bis-Boc-guanidino)proline was synthesized according to the method of Tamaki et al. (33).

The HEK293 cell lines stably expressing rat α3β4 and α4β4 nAChRs were obtained from Drs. Xiao and Kellar (34, 35), and the stable α4β2-HEK293 cell line was from Dr. Steinbach (36). The GH3 cell line stably expressing human α7 nAChR was a kind gift from Dr. Feuerbach (37). The construction of the α7/5-HT3A chimera has been described previously (38).

Chemistry

General—LC-MS spectrometry was performed using an Agilent 1200 series solvent delivery system equipped with an auto injector coupled to an Agilent 6410 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source. Gradients of 10% aqueous acetonitrile + 0.05% formic acid (buffer A) and 90% aqueous acetonitrile + 0.046% formic acid (buffer B) were employed with a flow rate of 0.75 ml/min. A Zorbax C18 column (2.1 × 0.50-cm inner diameter, 2 μm) was used. Preparative RP-HPLC was performed using an Agilent 1100 series system using a Zorbax preparative RP-HPLC column (C18, 250 × 21.2 mm, 7 μm). Crude peptide dissolved in 2 ml of buffer A (10% aqueous acetonitrile + 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid) was injected and eluted with a linear gradient from 0 to 50% buffer B (90% aqueous acetonitrile + 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid) over 50 min with a flow rate of 20 ml/min. Fractions were collected manually and analyzed by LC-MS to assess purity. Fractions found to contain pure peptide were pooled together and lyophilized. CD spectra were recorded on an OLIS-RSM1000 spectrometer (OLIS, Bogart, GA) between 185 and 260 nm at 20 °C. Samples were dissolved in 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at a concentration of 30 μm.

Peptide Synthesis—Peptides were assembled using Nα-Fmoc protection with 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU)-mediated couplings with Rink-amide polystyrene resin (Multisyntech, Witten, Germany). For each conotoxin, the carboxyl-terminal region was assembled using a Liberty microwave peptide synthesizer (CEM, Matthews, NC) to the point of the Pro6 mutation. The peptide-resin was then split into equal portions, and the remainder of the peptides was assembled in parallel using a mini-block (Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH). Cleavage from the resin was performed in parallel by stirring the resin (∼100 mg) in a mixture of trifluoroacetic acid/H2O/triisopropylsilane/ethanedithiol (87.5:5:5:2.5) for 2 h at room temperature. The resin was filtered from the mixture, the solvent evaporated in vacuo, and the peptide precipitated with diethyl ether. The ether was triturated and the peptide dissolved in 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and lyophilized.

Assembly of betainamidyl analogues was performed by Boc-SPPS using methylbenzhydrylamine-resin (Peptides International, Louisville, KY). Fmoc-4-(RS)-(Boc-amino)proline was incorporated at position 6, and then betaine was coupled using HBTU, following deprotection of the 4-amino group with trifluoroacetic acid. The Nα-Fmoc protecting group was then removed using 20% piperidine, and assembly of the remaining peptide sequence was continued using Boc-SPPS. Cleavage was performed using HF/p-cresol/p-thiocresol (18:1:1) for 2 h at 0 °C using an HF cleavage apparatus (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan). Following cleavage, the HF was evaporated in vacuo, and the peptide was precipitated with cold diethyl ether, filtered, washed with additional ether, filtered again, dissolved away from the resin with buffer A, and then lyophilized.

Oxidation and folding were achieved by dissolving the reduced peptide in a mixture of 0.1 m NH4HCO3 (pH 8.2) containing 50% 2-propanol to a concentration of ∼0.5 mm and stirring in an open vessel for 2 days at room temperature. The oxidation was monitored by LC-MS to ensure complete oxidation. The oxidation mixture was quenched by adjusting the solution to pH 2 with trifluoroacetic acid, and half the solvent was evaporated and lyophilized, and the oxidized product was purified by preparative RP-HPLC.

Disulfide Bond Connectivity Determination—A modified reduction/alkylation strategy based on the method of Gray (39) was used. Partial reduction was achieved by incubating the peptide (50 μg) in 0.2 m citrate buffer (pH 3, 50 μl) with 50 eq of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride at 25 °C for 5 min, after which it was injected onto RP-HPLC (Zorbax C18 column, 2.1 × 0.50-cm inner diameter, 2 μm) and fractionated using a linear gradient. Fractions were analyzed by LC-MS, and those containing the partially reduced conotoxin (+2 atomic mass units) were pooled, lyophilized, dissolved in 50 mm N-phenylmaleimide in n-propyl alcohol (50 μl), and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h to alkylate the free thiol groups on cysteine residues. The partially reduced/alkylated conotoxin was then isolated by RP-HPLC, and the remaining disulfide bonds were reduced by treatment with 50 eq of tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride in 0.2 m citrate for 16 h at 37 °C. The reduced/alkylated peptide was analyzed by tandem LC/MS to identify location of the two alkylated cysteine residues in the amino acid sequence.

Structure Determination by NMR—NMR data for ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] was recorded on a sample dissolved in 90% H2O, 10% D2O at pH 3.5 using a Bruker ARX 600-MHz spectrometer. Two-dimensional NMR experiments included double quantum-filtered-correlation spectroscopy, E-correlation spectroscopy, total correlation spectroscopy, and nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy, with all spectra recorded at 280-290 K. Peak intensities from a nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy spectrum with a mixing time of 200 ms at 290 K were used to determine distance restraints. Backbone dihedral restraints were determined from 3JHN-Hα coupling constants, and ϕ angles were restrained to -60 ± 30o for 3JHN-Hα < 5.8 Hz (Cys2, Cys3, Ser4, Arg7, Trp10, Arg11, and Cys12) and -120 ± 30o for 3JHN-Hα > 8.0 Hz (Cys8). Intra-residue nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy and 3JHα-Hβ coupling patterns were used in assigning χ1 angle restraints of some side chains (Cys2, Cys3, Cys5, and Cys8).

Initial structures were generated using Cyana software (40), and the final structure calculations were performed using a simulated annealing protocol with CNS (41) as described previously (42). Fifty structures were calculated, and the 20 with the lowest overall energies were retained for analysis. Structures were visualized using MOLMOL (43) and analyzed with PROMOTIF (44) and PROCHECK_NMR (45).

Pharmacology

Cell Culture—The cell lines used in this study were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The tsA-201 cells were maintained in culture medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with penicillin (100 units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 10% fetal bovine serum). The stable α4β2-, α3β4-, and α4β4-HEK293 cell lines were maintained in culture medium supplemented with 1 mg/ml G-418 and the stable α7-GH3 cell line in culture medium supplemented with 0.1 mg/ml G-418.

[3H]Methyllycaconitine Binding Assay—[3H]Methyllycaconitine ([3H]MLA) competition binding experiments with tsA-201 cells transiently transfected with the α7/5-HT3A chimera were performed essentially as described previously (38). 2 × 106 tsA-201 cells were split into a 10-cm tissue culture plate and transfected the following day with 8 μg of α7/5-HT3A-pCDNA3 using Polyfect as a DNA carrier according to the protocol by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The day after the transfection the culture medium on the cells was changed, and the following day the [3H]MLA binding assay was performed. Briefly, the cells were scraped into 30 ml of assay buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.2)), homogenized using a Polytron for 10 s, and centrifuged for 20 min at 50,000 × g. The resulting pellet was homogenized in 30 ml of assay buffer and centrifuged again. The cell pellet was then resuspended in the assay buffer, and the membranes were incubated with 0.5 nm [3H]MLA and various concentrations of the test compounds. The total reaction volume was 600 μl, and nonspecific binding was determined in reactions with 5 mm (S)-nicotine. The assay mixtures were incubated for 2.5 h at room temperature while shaking. GF/C filters were pre-soaked for 1 h in a 0.2% polyethyleneimine solution, and binding was terminated by filtration through these filters using a 48-well cell harvester and washing three times with 4 ml of ice-cold isotonic NaCl solution. Following this, the filters were dried; 3 ml of Opti-Fluor™ (Packard Instrument Co.) was added, and the amount of bound radioactivity was determined in a scintillation counter. The fraction of specifically bound radioligand was always <5% of the total amount of radioligand. The binding experiments were performed in duplicate at least three times for each compound.

[3H]Epibatidine Binding Assay—[3H]Epibatidine competition binding experiments with the stable α4β2-, α3β4-, and α4β4-HEK293 cell lines were performed essentially as described previously (38). Briefly, cells were harvested at 80-90% confluency and scraped into assay buffer (140 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm Mg2SO4, 25 mm HEPES (pH 7.4)), homogenized using a Polytron for 10 s, and centrifuged for 20 min at 50,000 × g. Cell pellets were resuspended in fresh assay buffer, homogenized, and centrifuged at 50,000 × g for another 20 min. Then the cell pellets were resuspended in the assay buffer, and the cell membranes were incubated with 25 pm [3H]epibatidine in the presence of various concentrations of compounds in a total assay volume of 1500 μl. Nonspecific binding was determined in reactions with 5 mm (S)-nicotine. The reactions were incubated for 4 h at room temperature while shaking. Whatman GF/C filters were pre-soaked for 1 h in a 0.2% polyethyleneimine solution, and binding was terminated by filtration through these filters using a 48-well cell harvester and washing three times with 4 ml of ice-cold isotonic NaCl solution. Following this, the filters were dried; 3 ml of Opti-Fluor™ (Packard Instrument Co.) was added, and the amount of bound radioactivity was determined in a scintillation counter. The binding experiments were performed in duplicate at least three times for each compound.

Fluo-4/Ca2+ Assay—The antagonistic properties of the α-conotoxin analogues were characterized at a α3β4-HEK293 cell line (34) and at a stable α7-GH3 cell line (37) in the fluorescence-based Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay. The cell lines were split into poly-d-lysine-coated black 96-well plates with a clear bottom (BD Biosciences), and the assay was performed 16-24 h later (in the case of the α3β4-HEK293 cell line) or 64-72 h later (in the case of the α7-GH3 cell line). The medium was aspirated, and the cells were incubated in 50 μl of loading buffer (Hanks' buffered saline solution containing 20 mm HEPES, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, and 2.5 mm probenecid (pH 7.4), supplemented with 6 mm Fluo-4/AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR)) at 37 °C for 1 h. The loading buffer was aspirated, and the cells were washed once with 100 μl of assay buffer (Hanks' buffered saline solution containing 20 mm HEPES, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, and 2.5 mm probenecid (pH 7.4)), and then 100 μl of assay buffer containing various concentrations of α-conotoxin analogues was added to the wells. For the experiments with α7-GH3 cell line, the assay buffer was supplemented with 100 μm genistein. Following a 30-min incubation at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator, the 96-well plate was assayed in a NOVOstar™ microplate reader (BMG Labtechnologies, Offenburg, Germany) measuring emission (in fluorescence units) at 520 nm caused by excitation at 485 nm before and up to 60 s after addition of 33 μl of agonist solution (the agonists were dissolved in assay buffer). The compounds were characterized in duplicate at least three times at the two nAChR subtypes, and EC80-EC90 concentrations were used as assay concentrations of agonists (30 μm ACh for the α7-GH3 cell line and 300 nm epibatidine for the α3β4-HEK293 cell line).

Computational Chemistry

Homology Modeling—A homology model of the α7 nAChR dimer in complex with α-conotoxin ImI was built using Modeler 9 version 3 (46). The ligand binding domain of the mouse nAChR α1 subunit (PDB code 2qc1) and the Ac-AChBP in complex with α-conotoxin ImI (PDB code 2byp, chain A and B) served as templates. In regions of structural similarity between the templates both templates were used. The binding site of 2qc1 contains a Trp-to-Arg mutation, which may affect the local structure, and this part was disregarded as template. The C loop was only modeled from 2byp, and α-conotoxin ImI was incorporated into the model as a rigid body. Further details regarding alignment can be found in the supplemental material. 100 models were generated using default settings. Model evaluation was performed with the discrete optimized protein energy potential (47) incorporated in Modeler, and the best scoring model was selected for further refinement. The rotamers of side chains Lys145A and Asp197A were adjusted to those seen in the 2byp crystal structure. Tightly bound water molecules within 5 Å of α-conotoxin ImI were inserted using GRID molecular interaction field calculations and treated as part of the receptor (48). The calculation was performed on the selected homology model using the OH2 probe with 5 grid points/Å. The GRID utilities Minim and Filmap were used to identify and populate the minima, respectively, using interpolation with an energy cutoff of -12 kcal/mol. The protein preparation workflow in Maestro (49) was used to thoroughly sample the water molecule orientations and refine the whole complex to optimize hydrogen bonds and relieve steric clashes using an r.m.s.d. cutoff of 0.3 Å on all heavy atoms.

Docking—Input structures with the proline substituents in a pseudo equatorial and a pseudo axial orientation were constructed by adding the unnatural proline substituents to the native and Pro6 ring flipped structure of α-conotoxin ImI present in the 2byp x-ray crystal structure followed by an energy minimization within MacroModel (50, 51) using the MMFFs force field and an aqueous solvation model. The structure of the suggested bioactive conformation of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] closely resembles the structural ensemble determined by NMR with r.m.s.d. for backbone atoms around 0.5 Å. Flexible induced fit docking was performed using the Schrödinger Glide (52, 53) and Prime Tools as implemented in the induced fit docking protocol (54, 55). Tyr93A was mutated to Ala during the initial docking step. After reinsertion, the orientation of side chains Tyr93A, Trp149A and Leu119B all within 5 Å of the Pro6 side chain were sampled and minimized. Receptor and ligand scaling were set to 1.0 and 0.7, respectively. In a more flexible docking protocol, α-conotoxin ImI and the 3-(S)-phenyl α-conotoxin ImI analogue were docked with default scaling of protein and ligand after removal of water molecules. Tyr93A was mutated to alanine during the initial docking step, and all residues within 5 Å of the ligand poses were sampled and energy-minimized after reinsertion of Tyr93A. Three-dimensional structure diagrams were generated using PyMol visualization software (DeLano Scientific, San Francisco, CA).

RESULTS

Design and Synthesis of α-Conotoxin Analogues—Substituted proline derivatives used in the synthesis of the α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues were selected based on expected interactions with the hydrophobic binding pocket in the nAChR (Fig. 2). Both (S)- and (R)-substituted derivatives at the 4-position of the proline ring were examined to gain information on the optimal orientation of substituents into the binding pocket. Peptide analogues were synthesized using HBTU-mediated Fmoc SPPS with Rink-amide polystyrene resin.

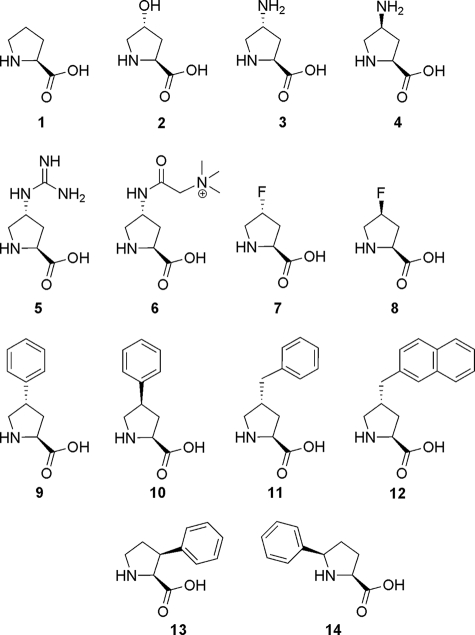

FIGURE 2.

Proline derivatives used in this study. 1, l-proline; 2, 4-(R)-hydroxy-l-proline, [4-(R)-OH]; 3, 4-(R)-amino-l-proline, [4-(R)-NH2]; 4, 4-(S)-amino-l-proline, [4-(S)-NH2]; 5, 4-(R)-guanidino-l-proline, [4-(R)-Gn]; 6, 4-(R)-betainamidyl-l-proline, [4-(R)-Bet]; 7, 4-(R)-fluoro-l-proline, [4-(R)-F]; 8, 4-(S)-fluoro-l-proline, [4-(S)-F]; 9, 4-(R)-phenyl-l-proline, [4-(R)-Ph]; 10, 4-(S)-phenyl-l-proline, [4-(S)-Ph]; 11, 4-(R)-1-naphthylmethyl-l-proline, [4-(R)-Nap]; 12, 4-(R)-benzyl-l-proline, [4-(R)-Bzl]; 13, 3-(S)-phenyl-l-proline, [3-(S)-Ph]; 14, 5-(R)-phenyl-l-proline, [5-(R)-Ph].

Hydroxylation of proline is a well known post-translational modification that occurs in α-conotoxin Vc1.1 (56) and other classes of conotoxins (57). It was recently reported that the introduction of hydroxyproline into α-conotoxin ImI improves its folding through cis-trans isomerization; however, it results in a complete loss of activity at the α7 nAChR (58). To further investigate the impact of introducing polar functional groups on the Pro6 residue in α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] on their nAChR activity, we incorporated 4-(R)-hydroxyproline (2, [4-(R)-OH]), 4-(R)-aminoproline [4-(R)-NH2](3, [4-(R)-NH2]), and 4-(S)-aminoproline (4, (4-(S)-NH2)) (Fig. 2). Although α-conotoxin ImII, which possesses an arginine residue instead of the highly conserved Pro6 residue, also targets α7 nAChRs, it has been shown to bind to a different site at the receptor compared with the binding site of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] (59). In a previous study, substitution of Pro6 in α-conotoxin ImI with Arg and substitution of Arg6 in α-conotoxin ImII with Pro have been found to result in a loss of nAChR activity for both analogues (12). To investigate the activities and binding modes of α-conotoxin analogues with positively charged proline derivatives in position 6 to the nAChRs, we have also included ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues containing 4-(R)-guanidinoproline (5, [4-(R)-Gn]) in this study.

The endogenous agonist for nAChRs, ACh contains a charged quaternary ammonium group that interacts with the binding pocket through a cation/π interaction as shown in the x-ray crystal structure of carbamoylcholine-Ls-AChBP complex (60). Therefore, a derivative consisting of betaine (N,N,N-trimethylglycine) coupled directly onto the amino group of 4-aminoproline during the course of SPPS was used to give 4-(R)-betainamidylproline (6, [4-(R)-Bet]).

Although the trans conformation of Pro6 is preferred in α-conotoxins, electronegative substituents on the 4-position have been shown to influence the conformation of proline residues in other classes of peptide such as collagen (61). The resultant conformational isomerization can potentially disrupt the native structure and lead to misfolding in disulfide-rich peptides (62). We have incorporated both 4-(R)-fluoroproline (7, [4-(R)-F]) and 4-(S)-fluoroproline (8, [4-(S)-F]) (Fig. 2) to determine the stereo electronic effects of Pro6 conformation on α-conotoxin folding, in addition to their effect on its nAChR activity.

The x-ray crystal structure of cobratoxin-Ls-AChBP shows Phe29 in cobratoxin interacting with residues in the hydrophobic binding pocket of Ls-AChBP (63). It was hypothesized that the phenyl moieties on 4-(R)-phenylproline (9, [4-(R)-Ph]) and 4-(S)-phenylproline (10, [4-(S)-Ph]) could interact in a similar way through a π-stacking. We synthesized ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues where additional aromatic side chains, including 4-(R)-benzylproline (11, [4-(R)-Bzl]) and 4-(R)-1-naphthylmethylproline (12, [4-(R)-Nap]) substituents, had been introduced. Furthermore, ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues containing 3-(S)-phenylproline (13, [3-(S)-Ph]) and 5-(R)-phenylproline (14, [5-(R)-Ph]) at Pro6 residues were also synthesized to determine the specific orientation of the phenyl substituents to gain optimal interaction with the binding pocket. We expected that steric factors contributed by substituents in the 3- and 5-positions would influence the proline conformation, particularly at the 5-(R)-position which would be expected to adopt the trans conformation.

Conformational Studies—The conformation of each α-conotoxin and their analogues was analyzed by CD spectroscopy (Fig. 3). α-Conotoxin analogues possessing a similar consensus fold to the native conotoxin exhibit distinct CD spectra with characteristic minima occurring at ∼200 nm (64, 65). Their helical content was also estimated by measuring their molar ellipticity at 222 nm (Fig. 3) (66).

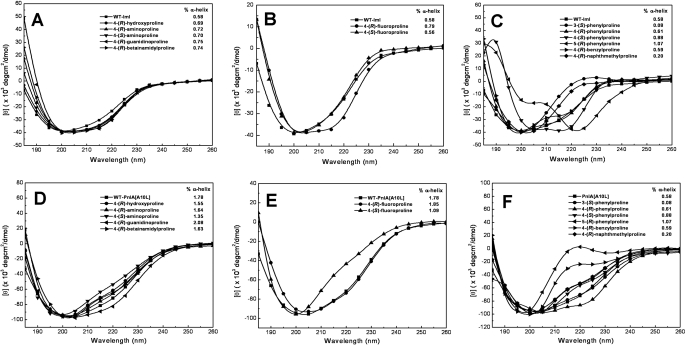

FIGURE 3.

Circular dichroism spectra of α-conotoxin Pro6 analogues. The % helix is indicated in the legend and was estimated as described by Woody (66). A, ImI analogues incorporating polar substituents; B, ImI analogues incorporating electronegative substituents on Pro6; C, ImI analogues incorporating aromatic substituents; D, PnIA[A10L] analogues incorporating polar substituents; E, PnIA[A10L] analogues incorporating electronegative substituents on Pro6; F, PnIA[A10L] analogues incorporating aromatic substituents.

Polar and charged substituents appear to have a minor effect on conformation, with α-conotoxin ImI analogues displaying slightly more helical structure compared with the native, whereas α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] analogues displayed less helical structure, with the exception of PnIA[A10L,P6/4-(R)-Gn]. Interestingly, the fluoro substituent on PnIA[A10L,P6/4-(S)-F] appeared to induce slightly more helix into the structure than in the corresponding 4-(R)-fluoro analogue. Although ImI[P6/4-(S)-F] displayed comparable CD-spectra to WT α-conotoxin ImI, ImI[P6/4-(R)-F] displayed significantly more helical conformation.

Incorporating aromatic substituents in the proline side chain appeared to have a more profound effect on conotoxin folding compared with other substituents. The CD spectra of ImI[P6/4-(R)-Ph] and ImI[P6/4-(R)-Bzl] analogues each resembled the native conotoxin; however, more significant changes were observed for the same analogues of α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L]. The 4-(S)-phenylproline analogues are similar to wild-type α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L]; however, the α-conotoxin ImI analogue structure appears significantly distorted. ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph] displayed a dramatic loss of helical content compared with the native conotoxin, whereas the same substitution in α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] exhibited a near identical CD curve to the native conotoxin. Interestingly, PnIA[A10L/4-(R)-Nap] exhibits a near identical CD spectrum compared with WT-PnIA[A10L]; however, ImI[P6/4-(R)-Nap] demonstrates an apparent random coil conformation, with a dramatic decrease in helical content.

The 5-(R)-phenyl substitution exhibited a more random coil conformation in α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L], yet significantly more helix was observed in α-conotoxin ImI. Furthermore, the CD spectra of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] differs considerably from all other CD spectra for analogues in this study.

Considering that the ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] and ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph] analogues displayed distinctly different CD spectra when compared with the native conotoxin, their disulfide bond connectivity was determined using a modified reduction/alkylation procedure described by Gray (39). The ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph] analogue, which exhibited a random coil-type structure possessed a ribbon (1-4, 2-3) connectivity. Interestingly, the 5-(R)-phenyl analogue of ImI possessed the native (1-3, 2-4) disulfide connectivity.

Structure Determination by NMR—An NMR solution structure of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] was determined to rationalize the differences observed in the CD spectra. NMR spectra were recorded at 290 K and showed single spin systems for each residue. The spectra were assigned, and chemical shift analysis indicated that the secondary shift values for ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] were comparable with those of the published values for native ImI indicating that the structures were similar. ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] exhibited a series of negative secondary shift values for residues 7-11, which is indicative of helical character and consistent with the conserved α-conotoxin framework. Observation of a nuclear Overhauser effect cross-peak between Asp5-Hα and P6/5-(R)-Ph-Hδ confirmed that the Asp-P6/5-(R)-Ph bond was in the trans configuration.

There were sufficient nuclear Overhauser effects to calculate a three-dimensional structure using a simulated annealing protocol in CNS (41). A set of 50 structures was calculated with 32 distance restraints consisting of 26 sequential, 4 medium range, and 2 long range restraints. Ten ϕ angle restraints were included and 4 χ1 angle restraints. The 20 lowest energy structures were chosen to represent the structure of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph], and this ensemble is shown in supplemental Fig. 1. Structural statistics for this NMR ensemble are provided in supplemental Table 1, and the structural data have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank. A relatively well defined structure was obtained, as shown by the r.m.s.d. over residues 1-12 of 0.33 ± 0.14 Å for the backbone atoms and 1.12 ± 0.44 Å for heavy atoms. Analysis of the structures with PROMOTIF (44) identified two 310 helices between residues 2-4 and residues 9-11, which is illustrated by the ribbon depiction in Fig. 4A.

FIGURE 4.

Three-dimensional structure of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph]. A, ribbon representation of the mean structure of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] showing the two 310 helical regions and the two disulfides (Cys2-Cys8 and Cys3-Cys12) in ball and stick representation. B, comparison of the peptide backbone conformation of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] (blue) and WT-ImI (PDB ID 1im1) (red) (68). The side chains at position 6 are also shown to illustrate the extension of the hydrophobic phenyl ring in ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph]. C, surface representations of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] (left) and WT-ImI (right). Hydrophobic residues are shown in green, polar in white, positively charged in blue, negatively charged in red, cystines in yellow, and glycine in cyan. Selected residue numbers are also shown. It is clear that the hydrophobic patch of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] is significantly increased in size compared with WT-ImI.

A comparison of the ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] structure with WT α-conotoxin ImI (PDB ID 1im1) (68) in Fig. 4B shows that there is a high degree of similarity between the peptide backbones of the two molecules. The r.m.s.d. of the backbone atoms of the mean structures from the two ensembles is only 0.819, and most of this difference is a result of minor variations in the backbones around positions 11 and 12. Fig. 4B also illustrates the conformation of the side chains at position 6 of the two peptides. As is expected the proline rings adopt a similar orientation with the phenyl ring extending from the proline core in ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph]. This phenyl ring at Pro6 in ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] results in the expansion of the hydrophobic surface of this analogue compared with that of native ImI as depicted in Fig. 4C.

Pharmacological Characterization of the α-Conotoxin Analogues—The binding affinities of the α-conotoxin analogues at heteromeric neuronal nAChR subtypes α4β2, α3β4, and α4β4 were determined in a [3H]epibatidine competition binding assay, and the α7 nAChR affinities of the analogues were determined in a [3H]MLA binding assay to an α7/5-HT3A chimera consisting of the amino-terminal domain of the rat α7 nAChR and the transmembrane domain of the mouse 5-HT3A receptor (Table 2) (38). We and others have previously demonstrated that the binding characteristics of these α4β2, α3β4, and α4β4 cell lines in the [3H]epibatidine binding assay are in excellent agreement with those reported for the recombinant receptors in other studies (36, 38, 69), and the binding characteristics of the α7/5-HT3A chimera in the [3H]MLA binding assay have been shown to be in concordance with those displayed by recombinantly expressed full-length α7 nAChRs and by native α7 receptors (38). The functional properties of the synthesized α-conotoxins as nAChR antagonists were determined at the α7-GH3 and α3β4-HEK293 cell lines in a fluorescence-based functional assay, the Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay (Table 3). In this assay, the two nAChRs display functional profiles in good agreement with those reported for the receptors in electrophysiological recordings (34, 35, 37).7

TABLE 2.

Binding affinities of α-conotoxin analogues to the α7/5-HT3A chimera and to the rat α3β4 nAChR subtype

The Ki values are from [3H]MLA (α7/5-HT3A) and [3H]epibatidine (α3β4) binding experiments. The Ki values are the means of 3-5 experiments and are given in μm with pKi ± S.E. values in parentheses. None of the α-conotoxin analogues displayed significant binding to the α4β2 and α4β4 nAChR subtypes at concentrations up to 100 μm. In contrast, (S)-nicotine displayed Ki values of 0.013 μm (7.88 ± 0.04) and 0.10 μm (6.99 ± 0.05) at α4β2 and α4β4, respectively.

| Compounds | α7/5-HT3A | α3β4 |

|---|---|---|

| Reference ligands | ||

| MLA | 0.0012 (8.92 ± 0.04) | NDa |

| (S)-Nicotine | 40 (4.39 ± 0.03) | 0.21 (6.67 ± 0.04) |

| ImI Pro6 analogues | ||

| WT | 1.2 (5.92 ± 0.05) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Hydroxy | ∼100 (∼4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Amino | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(S)-Amino | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Guanidino | ∼100 (∼4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Betainamidyl | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Fluoro | 6.6 (5.18 ± 0.05) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(S)-Fluoro | 8.9 (5.05 ± 0.03) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Phenyl | 7.0 (5.1 ± 0.03) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(S)-Phenyl | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Benzyl | ∼30 (∼4.5) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Naphthylmethyl | 8.0 (5.10 ± 0.06) | 11 (4.95 ± 0.05) |

| 3-(S)-Phenyl | 6.5 (5.2 ± 0.05) | >100 (<4) |

| 5-(R)-Phenyl | 0.19 (6.73 ± 0.05) | 3.5 (5.45 ± 0.03) |

| PnIA[A10L] Pro6 analogues | ||

| WT | 0.26 (6.58 ± 0.03) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Hydroxy | ∼30 (∼4.5) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Amino | ∼100 (∼4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(S)-Amino | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Guanidino | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Betainamidyl | ∼100 (∼4) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Fluoro | 3.6 (5.44 ± 0.05) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(S)-Fluoro | 3.7 (5.43 ± 0.02) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Phenyl | 1.7 (6.6 ± 0.04) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(S)-Phenyl | 7.6 (6.6 ± 0.04) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Benzyl | 8.9 (5.05 ± 0.04) | >100 (<4) |

| 4-(R)-Naphthylmethyl | 3.0 (5.53 ± 0.03) | >100 (<4) |

| 3-(S)-Phenyl | ∼100 (∼4) | >100 (<4) |

| 5-(R)-Phenyl | >100 (<4) | >100 (<4) |

ND means not determined.

TABLE 3.

Functional properties of α-conotoxin analogues at the human α7 and the rat α3β4 nAChRs

The IC50 values are from Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay at human α7-GH3 and rat α3β4-HEK293 cell lines using EC80-EC90 values of the agonist (30 μm ACh for human α7-GH3 and 300 nm epibatidine for rat α3β4-HEK293). The IC50 values are the means of 3-5 experiments and are given in μm with pIC50 ± S.E. values in parentheses.

| Compounds | α7 | α3β4 |

|---|---|---|

| Reference ligands | ||

| ACh EC50 | 15 (4.82 ± 0.04) | NDa |

| Epibatidine EC50 | ND | 0.071 (7.14 ± 0.04) |

| MLA | 0.0056 (8.25 ± 0.04) | ND |

| ImI Pro6 analogues | ||

| WT | 2.6 (5.58 ± 0.04) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Hydroxy | ∼100 (∼4) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Amino | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(S)-Amino | ∼300 (∼3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Guanidino | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Betainamidyl | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Fluoro | 30-100 (4.5-4) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(S)-Fluoro | 30-100 (4.5-4) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Phenyl | 14 (4.85 ± 0.05) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(S)-Phenyl | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Benzyl | 30-100 (4.5-4) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Naphthylmethyl | 30 (4.52 ± 0.05) | 19 (4.71 ± 0.05) |

| 3-(S)-Phenyl | 11 (4.94 ± 0.04) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 5-(R)-Phenyl | 0.70 (6.15 ± 0.04) | 3.7 (5.43 ± 0.05) |

| PnIA[A10L] Pro6 analogues | ||

| WT | 0.51 (6.18 ± 0.02) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Hydroxy | ∼300 (∼3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Amino | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(S)-Amino | ∼300 (∼3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Guanidino | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Betainamidyl | ∼300 (∼3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Fluoro | ∼100 (∼4) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(S)-Fluoro | 30-100 (4.5-4) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Phenyl | 26 (4.5 ± 0.05) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(S)-Phenyl | 33 (4.6 ± 0.04) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 4-(R)-Benzyl | 30-100 (4.5-4) | ∼100 (∼4) |

| 4-(R)-Naphthylmethyl | 30-100 (4.5-4) | ∼100 (∼4) |

| 3-(S)-Phenyl | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

| 5-(R)-Phenyl | >300 (<3.5) | >300 (<3.5) |

ND means not determined.

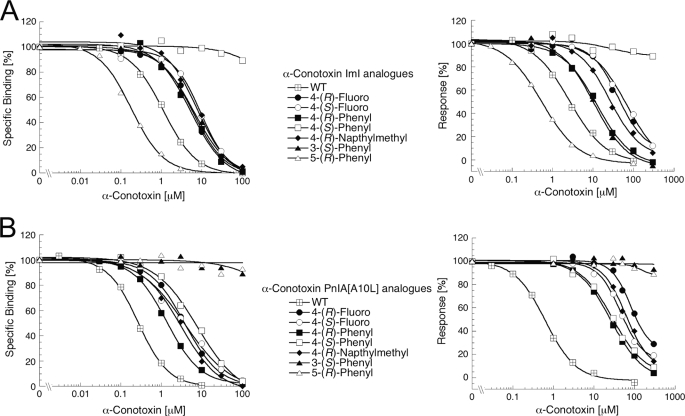

The WT α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] displayed low micromolar and high nanomolar binding affinities, respectively, to the α7/5-HT3A chimera in the [3H]MLA binding assay, whereas neither of the toxins displayed any significant binding to the heteromeric neuronal nAChR subtypes α4β2 (Table 2), α3β4, and α4β4 at concentrations up to 100 μm. Furthermore, in the Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] inhibited α7 nAChR signaling in the α7-GH3 cell line with IC50 values similar to those reported for the respective toxins at the receptor in previous studies (59, 70, 71), whereas neither of the conotoxins inhibited α3β4 nAChR signaling in the same assay at concentrations up to 300 μm (3). Thus, the previously reported α7 nAChR selectivity of the two conotoxins confirmed in both binding and functional assays.

The majority of the synthesized α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues have (S)- or (R)-substituted derivatives at the 4-position of the Pro6 residue. As can be seen from Tables 2 and 3, substitutions of the Pro6 residue in α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] with amino acids with polar and charged substituents on Pro6 are clearly not tolerated, because none of the 4-(R)-amino, 4-(S)-amino, 4-(R)-guanidino, and 4-(R)-betainamidyl analogues displayed any significant binding to the α7/5-HT3A chimera or any antagonistic effects at the α7-GH3 cell line in concentration ranges tested (Tables 2 and 3). PnIA[A10L,P6/4-(R)-OH] demonstrated only modest binding affinity to the α7/5-HT3A chimera (∼30 μm) in the binding assay. Introducing aromatic substituents at the Pro6 position in α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] resulted in analogues with modest α7 nAChR activities compared with the native toxins. However, the reductions in activity observed for these analogues were far less pronounced than for the analogues with polar and charged substituents (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5). The 4-(R)-phenylproline Pro6 analogues of both ImI and PnIA[A10L] displayed the highest activities at the α7 nAChR of all the analogues substituted at the 4-position. Interestingly, all α7 nAChR activity of ImIP6/[4-(S)-Ph] was eliminated, and PnIA[A10L,P6/4-(R)-Ph] displayed low micromolar binding affinity to the receptor, and thus “only” displayed a 30-fold lower binding affinity than its corresponding native toxin (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Another interesting observation from the series of aromatic analogues was that the 4-(R)-benzylproline analogues of both α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] displayed significantly lower binding affinities to the α7/5-HT3A chimera than the corresponding 4-(R)-naphthylmethylproline analogues (Table 2). Finally, the 4-(R)-fluoroproline and 4-(S)-fluoroproline analogues of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] displayed 5-15-fold reduced binding affinities to the α7/5-HT3A chimera and markedly impaired antagonistic properties at the α7 nAChR compared with those of their respective lead toxins (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Pharmacological properties of selected α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues. A, concentration-inhibition curves for WT α-conotoxin ImI and selected analogues at the α7/5-HT3A chimera in [3H]MLA binding assay (left) and at the human α7-GH3 cell line in the Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay (right). B, concentration-inhibition curves for WT α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] and selected analogues at the α7/5-HT3A chimera in [3H]MLA binding assay (left) and at the human α7-GH3 cell line in the Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay (right). The binding and functional experiments were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” In the binding assay, a tracer concentration of 0.5 nm [3H]MLA was used. In the Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay, an assay concentration of 30 μm ACh was used as agonist, and the assay was performed in the presence of 100 μm genistein. The figure depicts data from single representative experiments, and error bars are omitted for reasons of clarity.

Four α-conotoxin analogues, where the substituents had been introduced in the 3- and 5-positions of the proline ring, displayed interesting pharmacological properties. PnIA[A10L,P6/3-(S)-Ph] showed dramatically reduced α7 nAChR activity compared with WT-PnIA[A10L], whereas the corresponding ImI analogue only displayed an ∼5-fold impairment in its binding affinity and functional antagonistic potency compared with WT α-conotoxin ImI (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5). Furthermore, although the α7 nAChR activity was completely eliminated in PnIA[A10L,P6/5-(R)-Ph], the corresponding ImI analogue exhibited 6-fold higher binding affinity and 4-fold higher functional antagonistic potency than WT ImI (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5).

The vast majority of the α-conotoxin analogues characterized in this study were found to be completely devoid of activity at the heteromeric α4β2, α3β4, and α4β4 nAChR subtypes (Table 2). Interestingly, ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] and ImI[P6/4-(R)-Nap] displayed modest, but significant, activity at the α3β4 receptor, both in the [3H]epibatidine binding assay and in the Fluo-4/Ca2+ assay (Tables 2 and 3).

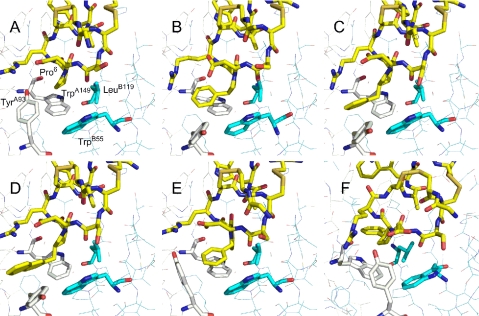

Molecular Modeling Studies—In an attempt to rationalize and explain the pharmacological properties of the α-conotoxin ImI analogues, potential binding modes of the α-conotoxin ImI analogues were evaluated by computational docking in a novel homology model of the α7 nAChR based on templates from the mouse α1 nAChR (72), Ac-AChBP co-crystallized with α-conotoxin ImI (18), and with inclusion of tightly bound water molecules as calculated by grid molecular fields. The profile based on the DOPE score for the individual residues in the model resembles that of the two templates indicating that the model and templates are of comparable quality. Furthermore, the quality of the model is confirmed by the fact that α-conotoxin ImI could be docked successfully using a flexible induced fit docking protocol; Tyr93A was mutated to alanine during the initial docking step, and after reinsertion of Tyr93A, side chains with in 5 Å of the proline ring were sampled and minimized.

The highest ranking pose based on the induced fit score (Table 4) of all docked α-conotoxin ImI analogues with binding affinity below 100 μm, except the 3-(S)-phenylproline α-conotoxin ImI analogue, adopted a binding mode with the α-conotoxin ImI backbone resembling the one observed in the AChBP co-crystallized with α-conotoxin ImI. A reasonable binding pose with a backbone conformation resembling that of WT α-conotoxin ImI was obtained for ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph] using a more flexible docking protocol. The scoring values for all docked ligands are listed in Table 4, and the suggested binding modes for α-conotoxin ImI analogues bearing aromatic substituents are shown in Fig. 6. The binding poses for WT α-conotoxin ImI and the 4-(R/S)-fluoro α-conotoxin ImI analogues resemble that of the WT α-conotoxin ImI co-crystallized with the AChBP with Tyr93A in its initial position. In the poses for the 4-(R)-phenylproline, 4-(R)-benzylproline, and 4-(R)-naphthylmethylproline α-conotoxin ImI analogues (Fig. 6, B-D), the aromatic substituents occupy the space initially occupied by Tyr93A, whereas Tyr93A has moved to a position resembling what is seen in the crystal structure of AChBP co-crystallized with lobeline. Interestingly, the binding mode suggested for ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph], which has a 10-fold increased affinity compared with the WT α-conotoxin ImI, has Tyr93A in a position resembling what is seen in the AChBP co-crystallized with a HEPES buffer molecule (PDB code 2br7) (17), allowing for a T-shaped interaction between the positive face of the 5-(R)-phenyl substituent and the center of the tyrosine ring as illustrated in Fig. 6E.

TABLE 4.

Scoring values for top scoring poses, α-Ctx-ImI analogues

| Compounds | Glide G score | IFD scorea |

|---|---|---|

| WT-ImI | −13.26 | −758.92 |

| 4-(R)-Fluoro | −13.09 | −759.24 |

| 4-(S)-Fluoro | −14.19 | −760.51 |

| 4-(R)-Phenyl | −12.67 | −755.34 |

| 4-(R)-Benzyl | −14.28 | −758.78 |

| 4-(R)-Naphthylmethyl | −15.59 | −759.95 |

| 5-(R)-Phenyl | −15.25 | −761.04 |

| 3-(S)-Phenyl | −14.72 | −766.87b |

IFD is induced fit score = Glide G-score + 0.05 × Prime energy; more negative is better.

Data are not comparable to values above due to different docking protocol. The corresponding values for WT α-conotoxin ImI are as follows: G score, − 14.03; induced fit score, − 766.19.

FIGURE 6.

The α7 nAChR homology model and top scoring docking poses. A, WT α-conotoxin ImI; B, ImI[P6/4-(R)-Ph]; C, ImI[P6/4-(R)-Bzl]; D, ImI[P6/4-(R)-Nap]; E, ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph]; F, ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph].

DISCUSSION

The high resolution of x-ray crystal structures of several AChBPs complexed with orthosteric nAChR ligands has provided considerable insight into the structure of the amino-terminal domains of nAChRs and the molecular basis for ligand binding to the receptors. In this study, we have applied the information obtained from crystal structures of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L,D14K] complexed with AChBPs in our rational design of novel α-conotoxin analogues targeting the α7 nAChR. To gain further insight into the binding mode of these toxins to the nAChR and in particular to investigate the role of the highly conserved Pro6 residue, several different substituents were introduced on Pro6 of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] based on their expected interactions with the aromatic binding pocket in the nAChR.

Impact of Pro6 Substituents on α-Conotoxin Conformations in Solution—It has been suggested that the conserved proline residue induces a helical motif into the α-conotoxin structure (14). We have examined the effect of substitutions on position, stereochemistry, and nature of the aromatic substituents on this proline on the overall conformation of the folded α-conotoxin analogues in solution by CD measurements. Although polar and charged substituents had relatively minor effects on conformation, aromatic substituents induced more significant conformational changes. This was greatly influenced by the position of the aromatic substituent on the proline side chain, where substituents on the 4-(R)-Pro6 position were found to stabilize the native conformation. Significant conformational changes were observed for the 3-(S)-phenylproline and 5-(R)-phenylproline analogues. Generally, more significant conformational changes were observed for the α-conotoxin ImI analogues compared with α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] analogues. This can be attributed to the length of the 310 helical motif in α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L], which adopts two full helical turns compared with α-conotoxin ImI that contains only a single turn (Fig. 1).

The tendency for certain analogues to adopt a random coil conformation suggests misfolding of analogues from the native “globular” isomer to the “ribbon” isomer has occurred. Perhaps even more intriguing is that several of these presumably misfolded analogues possess only a modest reduction in bioactivity compared with the native conotoxin. This is particularly evident with ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph], where the conformation in solution is shifted to a random coil, yet this analogue has retained activity at the α7 nAChR. This may not be so surprising, however, considering that the misfolded and structurally less defined ribbon isomer of α-conotoxin AuIB analogously has been shown previously to be a more potent antagonist at the α3β4 nAChR than the native globular isomer (73).

Although the CD spectra of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] differs considerably from WT-ImI, NMR structural studies confirmed that the three-dimensional conformation closely resembles the native conotoxin. We speculate that the differences observed in the CD spectra are a result of restricted conformational mobility induced by the phenyl substituent in the 5-(R)-position, where Pro6 is effectively locked into the active trans conformation in ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph]. Conversely, the phenyl substituent in the 3-(S)-position in ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph] would be expected to adopt the cis conformation, which also explains the preference for the non-native ribbon (1-4) disulfide bond isomer. We also speculate that the difference in the CD spectra and loss of activity observed for PnIA[A10L,P6/5-(R)-Ph] is the result of the adjacent Pro7 residue that is locked into the inactive conformation.

Structure-Activity Relationships for the α-Conotoxin Analogues as nAChR Antagonists—The binding and functional characteristics of the α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues listed in Tables 2 and 3 constitute an elaborate structure-activity study of the functional importance of the Pro6 residues in the two conotoxins. In this section, we will highlight interesting structure-activity findings, and in the following section the molecular basis underlying the α7 nAChR-activities of the α-conotoxin ImI analogues will be discussed based on dockings of the analogues into a homology model of the amino-terminal domain of the receptor.

Introduction of polar (hydroxyl and amino) and charged quaternary amino (guanidine and betainamidyl) groups into the 4-(R)-position of the ring of the Pro6 residues in α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] had detrimental effects on the α7 nAChR activity of the conotoxins (Tables 2 and 3). However, these analogues appeared to exhibit similar folding characteristics to the native α-conotoxins as described previously and support the observation that polar substituents aid in vitro oxidative folding (58). It has been previously shown that the Arg6 residue in α-conotoxin ImII is the major determinant of the alternative, noncompetitive binding mode of this toxin compared with those of ImI and other α-conotoxins (12). Hence, the rationale behind the synthesis of the 4-(R)-guanidinoproline and 4-(R)-betainamidylproline analogues of α-conotoxins ImII and PnIA[A10L] was to mimic the physico-chemical characteristics of the arginine residue in α-conotoxin ImII. Because these analogues neither display significant binding to the α7/5-HT3A chimera in the [3H]MLA binding assay nor significant activity at the α7 nAChR in the functional assay, it is reasonable to conclude that not only do they not bind to the orthosteric site of the receptor, they also do not inhibit receptor signaling through binding to an allosteric site. A plausible explanation for the inactivity of these analogues is the difference in the length and restricted conformational mobility of the positively charged side chain of residue 6 in these α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues compared with that of Arg6 in α-conotoxin ImII.

Another interesting finding is the α3β4 nAChR activity displayed by the ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] and ImI[P6/4-(R)-Nap], albeit both analogues display only moderate activity at this receptor subtype. In contrast to the other α-conotoxin ImI analogues, these two analogues seem to bind to the orthosteric site of this heteromeric nAChR subtype but not to those in the α4β2 and α4β4 subtypes (Tables 2 and 3). Although the α3β4 activity added to α-conotoxin ImI with these substituents is a surprising result, the molecular determinants for α-conotoxin binding to α7 versus α3β4 nAChRs may not be that different, as illustrated by the α3β4 nAChR-selective antagonism displayed by α-conotoxin AuIB (74).

The most notable finding in this study is the increased α7 nAChR activity exhibited by the ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] analogue when compared with WT α-conotoxin ImI (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5A). The pharmacological activity of the two toxins at α7 nAChR is significantly different, although the improvement compared with the WT α-conotoxin is not more than ∼5-fold. Although this increase was not detected for the same substitution in PnIA[A10L], which led to a complete loss of activity (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5B), the CD spectrum exhibited a random coil-type conformation indicative of misfolding to the ribbon isomer. Considering that all substituents introduced into the 4-position of the Pro6 ring significantly decreased the activity at the α7 nAChR, introduction of substituents in the 5-position of the proline ring may be promising for the development of even more potent α7 nAChR-selective antagonists. The increased inhibitory potency of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] is quite remarkable, as it represents one of the very few studies so far where the pharmacological properties of native α-conotoxins have been improved via medicinal chemistry. The fact that the analogue also displays some activity at the α3β4 nAChR makes it a less α7 nAChR-selective antagonist than WT α-conotoxin ImI. However, it will be most interesting to characterize the activities of future α-conotoxin ImI analogues incorporating other 5-(R)-substituted proline derivatives at Pro6 at α3β4 and α7 nAChRs, as it may be possible to develop highly selective α7 nAChR antagonists as well as selective α3β4 nAChR antagonists from the ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] analogue.

A final conclusion that can be drawn from the pharmacological properties exhibited by the α-conotoxin analogues is that the structural requirements for α7 nAChR binding of α-conotoxins ImI and PnIA[A10L] seem to be quite different, or at least the activities of the two toxins are differentially affected by different Pro6 substituents. This is reflected in the dramatic differences in the α7 nAChR activities displayed by corresponding pairs of α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] Pro6 analogues. For example, whereas 3-(S)-phenyl and 5-(R)-phenyl substituents at Pro6 have detrimental effects on the α7 nAChR activity of α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L], the corresponding α-conotoxin ImI analogues display slightly decreased activity and increased activity, respectively, at the receptor compared with WT α-conotoxin ImI (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5). Conversely, the α7 nAChR activity of WT α-conotoxin ImI is completely eliminated in the 4-(S)-phenyl Pro6 ImI analogue, whereas the corresponding PnIA[A10L] analogue has retained some of the activity of WT α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] at the receptor (Tables 2 and 3 and Fig. 5). These observed differences in the pharmacological characteristics are not surprising, considering that the two series of analogues are derived from an α4/3-conotoxin (ImI) and an α4/7-conotoxin (PnIA[A10L]), respectively. However, the differences certainly demonstrate that although the Pro6 residue in both of these toxins clearly plays an important role for their overall three-dimensional structure and nAChR activity, the structures, and ultimately the nAChR activities of the toxins, are very differently affected by the introductions of substituents at this conserved residue.

Binding Modes of the α-Conotoxin ImI Analogues to the α7 nAChR—High resolution x-ray structures of the AChBPs have revealed significant flexibility of side chains in and around the ligand binding pocket as well as large scale domain movements of the C loop known to adapt to the ligand when binding to the protein. Most docking protocols can handle ligand and side chain flexibility, whereas the large scale domain movements represent a more challenging task. To avoid dealing with various degrees of C loop closure in the docking protocol, this study was restricted to investigation of whether structure-activity relationships of the α-conotoxin ImI analogues with measurable affinity could be explained in terms of interactions with the receptor (i.e. as substitution effects on the Pro6 ring). This assumes that the backbone of the conotoxin binds essentially as displayed in the x-ray structure of the AChBP co-crystallized with α-conotoxin ImI. For this purpose, a new homology model of the α7 receptor tailored to recognize α-conotoxin ImI-like binding modes was constructed. Immediate inspection of the model revealed insufficient room for large substituents on the subunit A face of the proline ring (Fig. 6A). However, Tyr93A is known from x-ray crystal structures of the AChBP to be flexible, and several different rotameric states of this residue are seen in e.g. the structures co-crystallized with lobeline (PDB code 2bys) (18) and HEPES (PDB code 2br7) (17). To take this flexibility into account, a flexible induced fit docking protocol was employed to suggest a binding mode for the α-conotoxin ImI analogues. During the initial docking step, Tyr93A was mutated to Ala, and the side chains within 5 Å of Pro6 were subsequently sampled and minimized after reinsertion of Tyr93A to allow the binding site to adapt to the docked ligands. Using this procedure or a more flexible version of the procedure (see “Experimental Procedures”) for docking of the ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph], all ligands with affinity below 100 μm were successfully docked with a backbone conformation resembling that of the WT α-conotoxin ImI as displayed in the x-ray structure 2byp. Interestingly, Tyr93A adopts markedly different rotameric states depending on the ligand docked suggesting that Tyr93A adapts to the docked ligand as also evident from experimentally determined structures. Apparently rotation of Tyr93A results in induction of a large lipophilic pocket that can accommodate an aromatic substituent attached to α-conotoxin ImI in the Pro6 4- and 5-positions. Compared with the other compounds investigated in this study, the phenyl substituent of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] protrudes less deeply into the pocket. As a consequence Tyr93A can reside at the bottom of the pocket allowing for a near-optimal T-shaped interaction between the positive edge of the phenyl ring and the negative center of the aromatic ring of Tyr93A (Fig. 6F). This may explain the superior affinity of this compound compared with the remaining analogues investigated in this study.

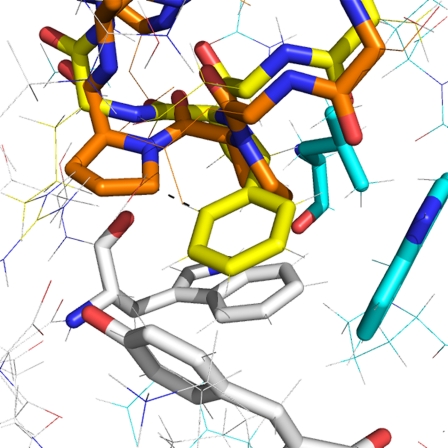

The ImI[P6/3-(S)-Ph] analogue adopts a different binding mode, still with a backbone conformation resembling that of the WT α-conotoxin ImI, but with the phenyl group pointing into a different binding pocket occupied by Leu10 of α-conotoxin-PnIA[A10L] in the x-ray crystal structure (PDB code 2br8) (17). Placing the phenyl substituent in this pocket is thus not possible for the PnIA[A10L] analogue, which may explain the lack of affinity of this compound. Similarly, superimposing the crystal structure of α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] on the α7 nAChR homology model with the docked pose of ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] (Fig. 7) indicates that the inducible aromatic pocket is already partly occupied by Pro7 of α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] and that a 5-(R)-phenyl substituent would have to distort the backbone conformation of the α-conotoxin to protrude into the pocket. This distortion of the backbone conformation is indeed evident when comparing the CD spectra of WT α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] with PnIA[A10L,P6/5-(R)-Ph] (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 7.

Superimposition of α-conotoxin PnIA[A10L] (orange) onto a homology model of α7 nAChR (ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] is shown in yellow).

Conclusion—In this study we have designed and prepared a number of α-conotoxin ImI and PnIA[A10L] analogues, inspired by x-ray crystal structures of α-conotoxins in complex with AChBPs. These x-ray crystal structures suggest that a conserved proline in the α-conotoxins, Pro6, is located near the aromatic binding pocket of the ligand binding pocket of the nAChR. However, in contrast to most small molecule nAChR ligands, the Pro6 residue does not seem to form direct interactions with residues in this pocket. We therefore hypothesized that substitutions of the Pro6 residue could lead to improved nAChR activities of the α-conotoxins provided that the substitutions could fit into the binding pocket.

Although most of the synthesized analogues displayed decreased activities at the α7 nAChR, one analogue in the series, ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph], was found to be a significantly more potent antagonist of the receptor than WT α-conotoxin ImI. Although this analogue displays a distinct CD spectrum, NMR studies confirmed a very similar three-dimensional fold to WT α-conotoxin ImI. Thus, our rational design provided an α-conotoxin with improved nAChR activity, which suggests that use of AChBP crystal structures as templates for the design of novel α-conotoxin analogues is a feasible way of optimizing the pharmacological activities of α-conotoxins. In this regard, it will be interesting to explore additional α-conotoxin ImI analogues with substituents in the 5-position of the Pro6 residue.

We applied molecular modeling to elucidate the structure-activity relationships of the active α-conotoxin ImI analogues prepared in this study in a structural context. Docking ImI[P6/5-(R)-Ph] into a homology model of the ligand binding domain of the α7 nAChR suggested this analogue interacts with a specific tyrosine residue, Tyr93A, in the ligand binding pocket in a more favorable manner than the other α-conotoxins, which could explain the improved activity of this analogue at the receptor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the generous gifts of cell lines from Drs. Xiao and Kellar (Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, D. C.), Dr. Steinbach (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO), and Dr. Feuerbach (Novartis Institutes of Biomedicinal Research, Basel, Switzerland). We thank Drs. Norelle Daly and Johan Rosengren for assistance with the NMR structure calculations.

This work was supported in part by post-doctoral grants from the Drug Research Academy, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Copenhagen (to C. A. and K. H.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. 1 and Table 1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: nAChR, nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; AChBP, acetylcholine-binding protein; ACh, acetylcholine; Ac-AChBP, Aplysia californica acetylcholine-binding protein; Ls-AChBP, Lymnaea stagnalis acetylcholine-binding protein; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl; Fmoc, fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl; HBTU, 2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293; LC-MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; [3H]MLA, [3H]methyllycaconitine; RP-HPLC, reversed phase-high performance liquid chromatography; SPPS, solid-phase peptide synthesis; WT, wild type; r.m.s.d., root mean square deviation; PDB, Protein Data Bank; 5-HT3, 5-hydroxytryptamine.

A. A. Jensen, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Sine, S. M., and Engel, A. G. (2006) Nature 440 455-463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen, A., Frølund, B., Liljefors, T., and Krogsgaard-Larsen, P. (2005) J. Med. Chem. 48 4705-4744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sher, E., Chen, Y., Sharples, T. J., Broad, L. M., Benedetti, G., Zwart, R., McPhie, G. I., Pearson, K. H., Baldwinson, T., and DeFillipi, G. (2004) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 4 283-297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lukas, R. J., Changeux, J.-P., Le Novere, N., Albuquerque, E. X., Balfour, D. J. K., Berg, D. K., Bertrand, D., Chiappinelli, V. A., Clarke, P. B. S., Collins, A. C., Dani, J. A., Grady, S. R., Kellar, K. J., Lindstrom, J. M., Marks, M. J., Quik, M., Taylor, P. W., and Wonnacott, S. (1999) Pharmacol. Rev. 51 397-401 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armishaw, C. J., and Alewood, P. F. (2005) Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 6 221-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satkunanathan, N., Livett, B., Gayler, K., Sandall, D., Down, J., and Khalil, Z. (2005) Brain Res. 1059 149-158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Livett, B. G., Sandall, D. W., Keays, D., Down, J., Gayler, K. R., Satkunanathan, N., and Khalil, Z. (2006) Toxicon 48 810-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gehrmann, J., Daly, N. L., Alewood, P. F., and Craik, D. J. (1999) J. Med. Chem. 42 2364-2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quiram, P. A., and Sine, S. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 11007-11011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobsen, R. B., DelaCruz, R. G., Gros, J. H., McIntosh, J. M., Yoshikami, D., and Olivera, B. M. (1999) Biochemistry 38 13310-13315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamthanh, H., Jegou-Matheron, C., Servent, D., Menez, A., and Lancelin, J. (1999) FEBS Lett. 454 293-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellison, M., McIntosh, J. M., and Olivera, B. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 757-764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everhart, D., Cartier, G. E., Malhotra, A., Gomes, A. V., McIntosh, J. M., and Luetje, C. W. (2004) Biochemistry 43 2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang, T. S., Radic, Z., Talley, T. T., Jois, S. D. S., Taylor, P., and Kini, R. M. (2007) Biochemistry 46 3338-3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quiram, P. A., and Sine, S. M. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 11001-11006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quiram, P. A., McIntosh, J. M., and Sine, S. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 4889-4896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Celie, P. H. N., Kasheverov, I. E., Mordintsev, D. Y., Hogg, R. C., van Nierop, P., van Elk, R., van Rossum-Fikkert, S. E., Zhmak, M. N., Bertrand, D., Tsetlin, V., Sixma, T. K., and Smit, A. B. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12 582-588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hansen, S. B., Sulzenbacher, G., Huxford, T., Marchot, P., Taylor, P., and Bourne, Y. (2005) EMBO J. 24 3635-3646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ulens, C., Hogg, R. C., Celie, P. H., Bertrand, D., Tsetlin, V., Smit, A. B., and Sixma, T. K. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 3615-3620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutertre, S., Ulens, C., Büttner, R., Fish, A., van Elk, R., Kendel, Y., Hopping, G., Alewood, P. F., Schroeder, C., Nicke, A., Smit, A. B., Sixma, T. K., and Lewis, R. J. (2007) EMBO J. 26 3858-3867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brejc, K., van Dijk, W. J., Klaasen, R. V., Schuurmans, M., van Der Oost, J., Smit, A. B., and Sixma, T. K. (2001) Nature 411 269-276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celie, P. H. N., Klaassen, R. V., van Rossum-Fikkert, S. E., van Elk, R., van Nierop, P., Smit, A. B., and Sixma, T. K. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 26457-26466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen, S. B., Talley, T. T., Radic, Z., and Taylor, P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 24197-24202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smit, A. B., Syed, N. I., Schaap, D., van Minnen, J., Klumperman, J., Kits, K. S., Lodder, H., van der Schors, R. C., Van Elk, R., Sorgedrager, B., Brejc, K., Sixma, T. K., and Geraerts, W. P. M. (2001) Nature 411 261-268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen, S. B., Radic, Z., Talley, T. T., Molles, B. E., Deerinick, T., Tsigelny, I., and Taylor, P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 41299-41302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cromer, B. A., Morton, C. J., and Parker, M. W. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27 280-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trudell, J. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1565 91-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laube, B., Maksay, G., Schemm, R., and Betz, H. (2002) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23 519-527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reeves, D. C., and Lummis, S. C. (2002) Mol. Membr. Biol. 19 11-26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Mara, M. L., Cromer, B., Parker, M. W., and Chung, S. H. (2005) Biophys. J. 88 3286-3299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dutertre, S., and Lewis, R. J. (2006) Biochem. Pharmacol. 72 661-670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamamura, H., Araki, T., Ueda, S., Wang, Z., Oishi, S., Esaka, A., Trent, J. O., Nakashima, H., Yamamoto, N., Peiper, S. C., Otaka, A., and Fujii, N. (2005) J. Med. Chem. 48 3280-3289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamaki, M., Han, G., and Hruby, V. J. (2001) J. Med. Chem. 66 3593-3596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao, Y., Meyer, E. L., Thompson, J. M., Surin, A., Wroblewski, J., and Kellar, K. J. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol. 54 322-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xiao, Y., and Kellar, K. J. (2004) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 310 98-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabey, K., Paradiso, K., Zhang, J., and Steinbach, J. H. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 55 58-66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feuerbach, D., Lingenhöhl, K., Dobbins, P., Mosbacher, J., Corbett, N., Nozulak, J., and Hoyer, D. (2005) Neuropharmacology 48 215-227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen, A. A., Mikkelsen, I., Frølund, B., Bräuner-Osborne, H., Falch, E., and Krogsgaard-Larsen, P. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64 865-875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray, W. R. (1993) Protein Sci. 2 1732-1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Güntert, P., Mumenthaler, C., and Wüthrich, K. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 273 283-298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brünger, A. T., Adams, P. D., Clore, G. M., DeLano, W. L., Gros, P., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Jiang, J. S., Kuszewski, J., Nilges, M. J., Pannu, N. S., Read, R. J., Rice, L. M., Simonson, T., and Warren, G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905-921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark, R. J., Fischer, H., Nevin, S. T., Adams, D. J., and Craik, D. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 23254-23263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koradi, R., Billeter, M., and Wüthrich, K. (1996) J. Mol. Graphics 14 51-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hutchinson, E. G., and Thornton, J. M. (1996) Protein Sci. 5 212-220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laskowski, R. A., Rullmann, J. A., MacArthur, M. W., Kaptein, R., and Thornton, J. M. (1996) J. Biomol. NMR 8 477-486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sali, A., and Blundell, T. L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 234 779-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen, M., and Sali, A. (2006) Protein Sci. 15 2507-2524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodford, P. J. (1985) J. Med. Chem. 28 849-857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schrödinger, LLC (2008) Maestro, Version 8.5, 110 Ed., Portland, OR

- 50.Mohamadi, F., Richards, N. G., Gouida, W. C., Liskamp, R., Lipton, M., Caulfield, C., Chang, T., Hendrickson, T., and Still, W. C. (1990) J. Comp. Chem. 11 440-467 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schrödinger, LLC (2008) MacroModel, Version 9.6, 110 Ed., Portland, OR

- 52.Friesner, R. A., Banks, J. L., Murphy, R. B., Halgren, T. A., Klicic, J. J., Mainz, D. T., Repasky, M. P., Knoll, E. H., Shelley, M., Perry, J. K., Shaw, D. E., Francis, P., and Shenkin, P. S. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47 1739-1749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halgren, T. A., Murphy, R. B., Friesner, R. A., Beard, H. S., Frye, L. L., Pollard, W. T., and Banks, J. L. (2004) J. Med. Chem. 47 1750-1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrödinger, LLC (2008) Prime, Version 2.0, 110 Ed., Portland, OR

- 55.Sherman, W., Day, T., Jacobson, M. P., Friesner, R. A., and Farid, R. (2006) J. Med. Chem. 49 534-553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sandall, D. W., Satkunanathan, N., Keays, D. A., Polidano, M. A., Liping, X., Pham, V., Down, J. G., Khalil, Z., Livett, B. G., and Gayler, K. R. (2003) Biochemistry 42 6904-6911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buczek, O., Bulaj, G., and Olivera, B. M. (2005) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 3067-3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Vera, E., Walewska, A., Skalicky, J. J., Olivera, B. M., and Bulaj, G. (2008) Biochemistry 47 1741-1751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ellison, M., Gao, F., Wang, H. L., Sine, S. M., McIntosh, J. M., and Olivera, B. M. (2004) Biochemistry 43 16019-16026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Celie, P. H. N., Van Rossum-Fikkert, S. E., Van Dijk, W. J., Brejc, K., Smit, A. B., and Sixma, T. K. (2004) Neuron 41 907-914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]