Abstract

CO dehydrogenase from the Gram-negative chemolithoautotrophic eubacterium Oligotropha carboxidovorans OM5 is a structurally characterized molybdenum-containing iron-sulfur flavoenzyme, which catalyzes the oxidation of CO (CO + H2O → CO2 + 2e- + 2H+). It accommodates in its active site a unique bimetallic [CuSMoO2] cluster, which is subject to post-translational maturation. Insertional mutagenesis of coxD has established its requirement for the assembly of the [CuSMoO2] cluster. Disruption of coxD led to a phenotype of the corresponding mutant OM5 D::km with the following characteristics: (i) It was impaired in the utilization of CO, whereas the utilization of H2 plus CO2 was not affected; (ii) Under appropriate induction conditions bacteria synthesized a fully assembled apo-CO dehydrogenase, which could not oxidize CO; (iii) Apo-CO dehydrogenase contained a [MoO3] site in place of the [CuSMoO2] cluster; and (iv) Employing sodium sulfide first and then the Cu(I)-(thiourea)3 complex, the non-catalytic [MoO3] site could be reconstituted in vitro to a [CuSMoO2] cluster capable of oxidizing CO. Sequence information suggests that CoxD is a MoxR-like AAA+ ATPase chaperone related to the hexameric, ring-shaped BchI component of Mg2+-chelatases. Recombinant CoxD, which appeared in Escherichia coli in inclusion bodies, occurs exclusively in cytoplasmic membranes of O. carboxidovorans grown in the presence of CO, and its occurrence coincided with GTPase activity upon sucrose density gradient centrifugation of cell extracts. The presumed function of CoxD is the partial unfolding of apo-CO dehydrogenase to assist in the stepwise introduction of sulfur and copper in the [MoO3] center of the enzyme.

Oligotropha carboxidovorans OM5 is an aerobic, Gram-negative member of the α-subclass of proteobacteria (1, 2). It utilizes CO as a sole source of carbon and energy under chemolithoautotrophic conditions (carboxidotrophy). The 133-kbp circular DNA megaplasmid pHCG3 of O. carboxidovorans has been completely sequenced (3), and the annotated genome sequence of the chromosome has been reported (4). The plasmid carries the gene clusters cox, cbb, and hox, which assemble the functions required for the utilization of CO, CO2, or H2, respectively (3). The three clusters form a 51.2-kb chemolithoautotrophy module. Transcription of the cox gene cluster (Fig. 1A) requires the presence of CO (3, 5, 6). CO dehydrogenase is the key enzyme in the utilization of CO {CO + H2O → CO2 + 2e- + 2H+} (7). It is a molybdenum- and copper-containing iron-sulfur flavoenzyme. The subunit structure is a dimer of heterotrimers, which are encoded by the genes coxMSL (3, 5, 6). The L subunit (CoxL, 88.7 kDa) is a molybdo-copper protein. It accommodates the catalytic site, which is buried ∼17 Å below the solvent-accessible surface of CO dehydrogenase (8-10). CO is oxidized at a unique [CuSMoO2] cluster.

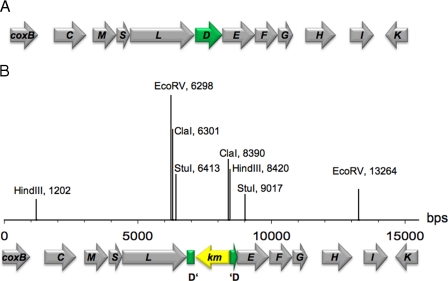

FIGURE 1.

Genetic organization of the cox gene cluster of O. carboxidovorans OM5 (A) and mutation of the coxD gene by insertion of a kanamycin resistance cassette (B). A, the 14.5-kb cox gene cluster is located on the megaplasmid pHCG3 of O. carboxidovorans OM5. The cluster is composed of nine accessory genes coxBCDEFGHIK and the structural genes coxMSL, which encode the CO dehydrogenase flavoprotein, iron protein, and Mo/Cu protein. Arrows indicate the direction of CO-dependent transcription. B, a kanamycin resistance cassette was inserted into coxD. A KIXX-probe for kanamycin resistance and a D-probe for coxD were employed to identify the mutated gene by Southern blotting. The approximate cleavage sites of restriction endonucleases are also indicated.

The molybdenum ion is coordinated by the molybdopterin cytosine dinucleotide cofactor (7, 8, 11). The copper ion is coordinated by the cysteine residue 388 of the active site loop VAYRCSFR (5, 6).

The M-subunit (CoxM, 30.2 kDa) is a flavoprotein accommodating the flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)4 cofactor. Binding of FAD to the flavoprotein requires the heterotrimeric enzyme complex (8, 12). The S-subunit (CoxS, 17.8 kDa) is an iron-sulfur protein that contains one [2Fe-2S] center proximal to the [CuSMoO2] cluster and another distal one. These cofactors establish an intramolecular electron transport that delivers the electrons generated through the oxidation of CO at the [CuSMoO2] cluster to [2Fe-2S] I, [2Fe-2S] II, and finally to FAD, from where they are fed into a CO-insensitive respiratory chain to generate a membrane potential (13).

O. carboxidovorans synthesizes CO dehydrogenase in two forms: as the catalytically active enzyme species and as a properly assembled apo-enzyme, which does not oxidize CO (10). Usually, both mature and immature species of the enzyme co-exist in the bacterial cell. Other than the functional enzyme, which contains the [CuSMoO2] cluster, the apo-enzyme lacks the copper ion and/or the sulfur connecting the two metals (10, 14). The immature [MoO3] form of the CO dehydrogenase active site can be reconstructed in vitro to yield the catalytically active [CuSMoO2] cluster, through the supply of sulfide first and subsequently of Cu(I) under reducing conditions (14). coxD is first in the subcluster coxDEFG, which locates transcriptional downstream of the CO dehydrogenase structural genes coxMSL. The CoxD protein of O. carboxidovorans (ORF 135 (3), formerly orf4 (6)) has a predicted molecular mass of 33.367 kDa, comprises 295 amino acids, carries the putative nucleotide binding site 43GEAGVGKT50, is devoid of transmembranous helices, and has no known functions up to now (5). Here we report the requirement of the CoxD function for the biogenesis of the [CuSMoO2] cluster in the active site of apo-CO dehydrogenase.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Organisms, Cultivation, and Heterologous Expression of CoxD—O. carboxidovorans strain OM5 D::km is a mutant defective in the coxD gene function. It has been produced by insertional mutagenesis of the wild-type strain O. carboxidovorans OM5 (DSM 1227, ATCC 49405 (15, 16)). Wild-type and mutant strains were grown in 70-liter fermentors (model Biostat, Braun Melsungen, Germany) in a mineral medium (16). Fermentors were supplied with a gas mixture of 5% CO2, 30% CO, 30% H2, and 35% air. Bacteria, harvested in the late exponential growth phase, were stored frozen at -80 °C until use.

Escherichia coli K38 pGP1-2/pETMW2 is a construct containing coxD under the control of the lac-repressor and a heat-inducible T7 RNA polymerase. A coxD-containing 0.98-kb NdeI-BamHI fragment (6) was cloned into the vector pET11a (Novagen, Heidelberg, Germany) yielding pETMW2, which subsequently was transformed into E. coli K38 pGP1-2 (17). The construct E. coli K38 pGP1-2/pETMW2 was cultivated aerobically at 30 °C in a fermentor supplied with 20 liters of LB medium (18) supplemented with ampicillin (200 μgml-1) and kanamycin (100 μg ml-1). Induction was with 1 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside.

Insertional Mutagenesis of coxD—The plasmid pETMW2 is a recombinant construct of vector pET11a (Novagen, Heidelberg, Germany), which carries the coxD sequence. The kanamycin resistance cassette was isolated from plasmid pUC4KIXX (Amersham Biosciences) of E. coli DH5α (19). For mutagenesis of coxD, pETMW2 was isolated from E. coli DH5α, and the kanamycin resistance cassette was inserted into the coxD sequence and transformed into E. coli DH5α. The recombinant plasmid is referred to as pETMW2km. The coxD::km sequence isolated from pETMW2km was cloned into the suicide plasmid pSUP 201-1 isolated from E. coli S-17-1 (20). The resulting plasmid pSUPD::km was transformed into E. coli S-17-1, and coxD::km was transferred from E. coli S-17-1 to O. carboxidovorans OM5 by conjugation (Fig. 1B). Mutagenesis was checked by Southern blotting employing a KIXX-probe directed against the kanamycin resistance cassette and a D-probe for coxD. The KIXX-probe was produced by isolating the 1.2-kb KIXX fragment from the plasmid pUC4KIXX followed by labeling with digoxigenin. For the D-probe, the plasmid pCDH1 was isolated from E. coli DH5α, restricted with BsiWI and NotI, resulting in fragments that were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis. A 0.4-kb fragment corresponding to the 5′ terminus of coxD was eluted from the gel and labeled with digoxigenin. For Southern blotting, plasmid-DNA was isolated from wild-type und mutant O. carboxidovorans OM5 and restricted with ClaI, EcoRV, HindIII, or StuI and with ClaI/HindIII, EcoRV/HindIII, or StuI/HindIII. The fragments were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and blotted onto a nylon membrane (Hybond-N, Amersham Biosciences). Restriction was performed as such that, if coxD::km was inserted correctly, the DNA fragments of the coxD mutant included areas that were not transferred by conjugation. A 3.6-kb EcoRV fragment of pETMW2km was included as a positive control.

Transcriptional Analysis of coxD—O. carboxidovorans OM5 or its mutant D::km were grown under conditions suitable to induce the biosynthesis of CO dehydrogenase (mineral medium, gas mixture composed of 5% CO2, 30% H2, 30% CO, and 35% air). Isolation of total RNA from the bacteria and slot blotting were performed as detailed previously (5, 21).

Purification and Assay of CO Dehydrogenase—The protocol described previously for the purification of the catalytically active CO dehydrogenase from O. carboxidovorans OM5 (8, 12) was adopted here to prepare the non-functional enzyme from the mutant OM5 D::km. Monitoring purification involved native PAGE (7.5% acrylamide, 50 mm Tris, 384 mm glycine, pH 8.5), staining for protein with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250, and quantitation of the CO dehydrogenase band by video densitometry with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/). Purified preparations were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C until use. CO dehydrogenase activity was assayed photometrically with CO as substrate and 1-phenyl-2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium chloride as electron acceptor (22). One unit of CO dehydrogenase activity is defined as 1 μmol of CO oxidized per min at 30 °C. Protein estimation followed published procedures (23, 24). The purity of CO dehydrogenase preparations was examined by SDS-PAGE (25) employing 7.5% acrylamide-stacking gels and 15% acrylamide-running gels. The concentration of purified CO dehydrogenase was determined employing a millimolar extinction coefficient (ε450) of 72 mm-1 cm-1 (26). UV-visible spectra were recorded on a spectrophotometer (Uvikon model 941, Kontron, Eching, Germany) as described previously (9).

Analysis of Cyanolysable Sulfur and Metals—Sulfane sulfur was determined by treating samples of CO dehydrogenase with potassium cyanide followed by colorimetric analysis of the resulting thiocyanate as FeSCN (10). Copper was determined by flame atomic absorption spectroscopy (PerkinElmer Life Sciences, model 1100 B). For that purpose 50 μl of CO dehydrogenase solution (2 mg/ml) in 50 mm Hepes/NaOH (pH 7.2) was injected. Calibration was with 4-50 μm CuSO4 in the same buffer. Molybdenum was assayed after oxidative wet ashing of samples of CO dehydrogenase with 96% sulfuric acid containing 30% H2O2 and colorimetric analysis at 680 nm of Mo(VI) as the dithiol complex (27).

Reconstitution of Apo-CO Dehydrogenase—Sulfur was introduced into apo-CO dehydrogenase (2.4 mg/ml) from 5 mm Na2S in the presence of 5 mm sodium dithionite in 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8.2) under anoxic conditions (pure nitrogen) as detailed previously (14). Assays were kept for 10 h at 36 °C, and the small molecular weight fraction was removed from the protein by anoxic gel filtration (Sephadex G-25, PD10, Amersham Biosciences). Cu(I) was introduced into resulfurated CO dehydrogenase (2.4 mg/ml) employing 125 μm Cu[SC(NH2)2]3Cl in 50 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8.2) followed by anoxic incubation at 36 °C. Small molecular weight compounds were removed by anoxic gel filtration.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy (XAS)—CO dehydrogenase (75 μl containing 230 mg/ml protein in 50 mm Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.2) was transferred to XAS cuvettes covered with Kapton windows, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80 °C until use. XAS data were collected at Deutsches Elektronen Synchroton (Hamburg, Germany) at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory bending magnet EXAFS beamline D2 using an Si (311) double monochromator for measurements at the Mo-K-edge. For measurements, the samples were cooled by a helium-closed-cycle cryostat with a temperature of 20 K. The experiments, data reduction, and analysis were performed as described before (10).

EPR Spectroscopy—X-band EPR spectra were recorded on a Bruker EMX spectrometer equipped with an ESR 900 helium cryostat (Oxford Instruments, Oxon, UK) as previously described (12). Spectra were recorded at 16 K, 50 K, and 120 K applying a microwave frequency of 9.47 GHz, 1-millitesla modulation amplitude, and 10-milliwatt microwave power. The magnetic field was calibrated with a diphenylpicrylhydrazine sample. CO dehydrogenase purified from the mutant D::km or the wild type (11.6 mg/ml in 50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.2) were made anoxic with pure argon and then reduced with 5 mm sodium dithionite or sparged with pure CO for 60 min and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

Miscellaneous Methods—Homogeneous recombinant CoxD was prepared by solubilizing inclusion bodies with 1.5% N-lauroylsarcosine followed by gel filtration on Sephacryl S-200 and denaturing PAGE. Protein bands were blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) and used for antibody production in rabbits (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). IgG antibodies directed against CoxD were purified from antisera employing chromatography on protein A-Sepharose. Samples for analysis on SDS-PAGE were prepared by boiling for 4 min in 160 mm tris-hydroxymethylaminomethane (Tris, pH 6.8) containing 1% SDS and 2.5% mercaptoethanol.

Sucrose density gradient centrifugation was performed in tubes containing 75 ml of 30-80% (w/v) sucrose in Tris buffer. Cell extract (5 ml) was layered on top of the gradient and centrifuged for 42 h at 100,000 × g at 4 °C (Uvikon, Kontron, Eching, Germany). The fraction volume was 1.7 ml. NTPases were assayed through the determination of inorganic phosphate released from Na2ATP or Na2GTP (28).

Chemicals—All chemicals employed were of analytical grade and purchased from the usual commercial sources.

RESULTS

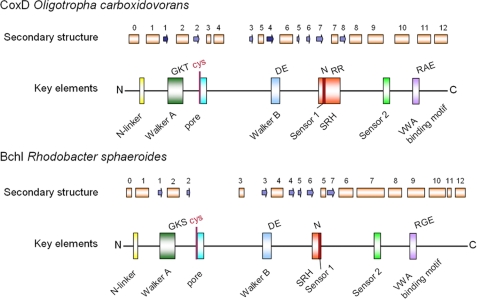

Bioinformatic Observations Group CoxD with the Chaperone-like “ATPase Associated with Various Cellular Activities” (AAA) Family of ATPases—CoxD displays 13 putative α-helices and 8 β-strands and is devoid of transmembranous helices (Fig. 2). Using a combination of methods for iterative database searching and multiple sequence alignment, CoxD is predicted as a new addition to the superfamily of AAA+ ATPases (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S1). The family comprises P-loop NTPases with oligomeric (mostly hexameric) ring structure that are able to induce conformational changes in a wide range of substrate proteins (29, 30). The N terminus of CoxD contains the N-linker in the loop connecting the helices α0 and α1 and shows the characteristic motif consisting of a hydrophobic amino acid (Ala17) and glycine (Gly18). In CoxD the P-loop of the Walker-A motif lies between strand β1 and helix α2 and contains the consensus G43X4G48KT50, whereas V130 LLIDE135 on β4 of CoxD is the Walker-B motif (X4DE), which interacts with ATP. The loop between β2 and α3 is the suggested pore loop of CoxD. The conserved YVG motif (aromatic-hydrophobic-glycine) of AAA+ ATPases (30) is modified in CoxD to CYE71G (SH-aromatic-acidic-glycine). The second region of homology (SRH) is considered to coordinate nucleotide hydrolysis and conformational changes between subunits (30). SRH of CoxD (amino acids 175-189) consists of part of β7 and all of α7 and contains sensor 1 (Asn177) and arginine fingers (Arg188-Arg189) at the end of α7. Sensor 2 of CoxD starts in the C-terminal end of α9 and extends into the loop connecting α9 and α10.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of structural motifs on BchI of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, which is an AAA+ ATPase chaperone, with CoxD of O. carboxidovorans. α-Helices are presented in orange and β-strands in blue; the gaps are represented by loops. α-Helices and β-strands are numbered starting from the N terminus. SRH, second region of homology; VWA, von Willebrand Factor A (integrin I).

CoxD gives the highest BLAST score (71% identity and 83% similarity) with a sequence of Bradyrhizobium sp. BTAi1, which is predicted as a MoxR-like AAA+ ATPase (National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The latter have been proposed to function with von Willebrand factor A (VWA, same as integrin I)-domain containing proteins to form a chaperone system that is important for the folding/activation of proteins and protein complexes by primarily mediating the insertion of metal cofactors into the substrate molecules (29). Within the MoxR AAA+ ATPases, which comprise at least seven subfamilies, CoxD groups with the APE2220 subfamily. Very frequently the genes of this family are in close proximity (typically adjacent) to genes encoding VWA proteins belonging to the CoxE COG3552 (NCBI Clusters of Orthologous Groups) (29). Indeed, coxD and coxE group together in the cluster coxDEFG of O. carboxidovorans and are separated by only two nucleotides (3, 5). The members of APE2220 and their associated VWA proteins have been considered important for proper metal cofactor insertion in CO dehydrogenases, xanthine dehydrogenases, and other enzymes of the molybdenum hydroxylase family (29).

CoxD shares characteristic features with the BchI component in the Mg2+-chelatase complex of Rhodobacter sphaeroides (Fig. 2). Particularly, both proteins combine an AAA+ module with a VWA binding motif in their C terminus and contain in their N terminus a pore loop, which is uniquely preceded by a cysteine. In the Mg2+-chelatase complex, BchI cooperates with BchD and BchH in the ATP-dependent insertion of Mg2+ into protoporphyrin IX (31, 32). In the functional cycle of Mg2+-chelatase a double-ring structure involving BchI and BchD is formed, blocking the ATPase activity of BchI (32). In the presence of Mg2+, this complex binds to BchH (33).

Mutation of the coxD Gene—The KIXX-probe, which is specific for the kanamycin resistance cassette, hybridized with all restriction fragments of the mutant strain O. carboxidovorans OM5 D::km (supplemental Fig. S2). The signal was not apparent in the wild-type strain. The coxD probe hybridized with all restriction fragments of the mutant and also with the wild-type strain (supplemental Fig. S2, A and B). The hybridization signals of plasmid DNA from the mutant with the KIXX-probe and the D-probe were indistinguishable, and the fragments had the right sizes, which indicate the successful insertion of the kanamycin resistance cassette into the coxD gene (Fig. 1).

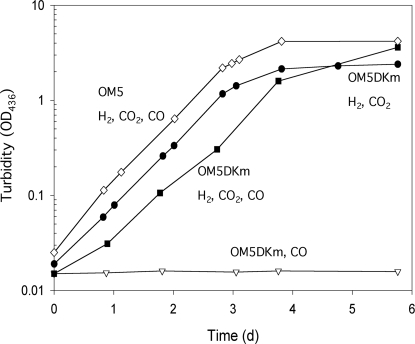

Inactivation of the coxD Gene Disables O. carboxidovorans OM5 D::km to Grow on CO—Growth with pyruvate or nutrient broth of the D::km mutant of O. carboxidovorans or the wild-type strain was the same (generation time ∼6 h), indicating that the inactivation of coxD does not affect the chemoorganoheterotrophic metabolism. Other than wild-type O. carboxidovorans, the D::km mutant was not able to utilize CO, whereas growth of the mutant with H2 plus CO2 was not impaired (Fig. 3). Obviously, the coxD function is specifically required in the chemolithoautotrophic metabolism of CO, particularly in the biosynthesis of CO dehydrogenase, and not in the assimilation of CO2 in the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle or any other essential metabolic route.

FIGURE 3.

Chemolithoautotrophic growth of the mutant O. carboxidovorans OM5 D::km. Bacteria were cultivated in a 70-liter fermentor supplied with a mineral medium and one of the following gas mixtures (all values are in v/v): 45% CO, 5% CO2, 50% air (▿); 40% H2, 10% CO2, 50% air (•); and 30% H2, 5% CO2, 30% CO, 35% air (▪). Growth of the wild-type strain O. carboxidovorans OM5 with H2 plus CO2 in the presence of CO (30% H2, 5% CO2, 30% CO, 35% air (□)) is shown for comparison. For further details see “Experimental Procedures.”

The entire cluster of cox genes is specifically and coordinately transcribed under chemolithoautotrophic conditions in the presence of CO (5). To properly induce CO dehydrogenase biosynthesis in the D::km mutant, the bacteria were cultivated under chemolithoautotrophic conditions with H2 plus CO2 and in the presence of CO as an inducer (Fig. 3). The generation time of ∼9 h (compared with ∼16 h with CO as sole energy source) indicates that, under these conditions H2 is the energy source and that growth of the D::km mutant is not impaired by the presence of CO (Fig. 3). This excludes a probable function of coxD in the metabolic insensitivity of O. carboxidovorans toward CO.

Transcription of cox Genes—In the wild-type strain of O. carboxidovorans growing with H2 plus CO2 and with CO as an inducer, the cox genes M, S, L, D, E, F, and G are properly transcribed (supplemental Fig. S2C). Under these conditions the D::km mutant did not show a coxD transcript, whereas all other cox genes examined were readily transcribed. These data indicate that the mutation has specifically inactivated coxD, does not exert a polar effect on neighboring genes, and that the coxD mutant is not leaky.

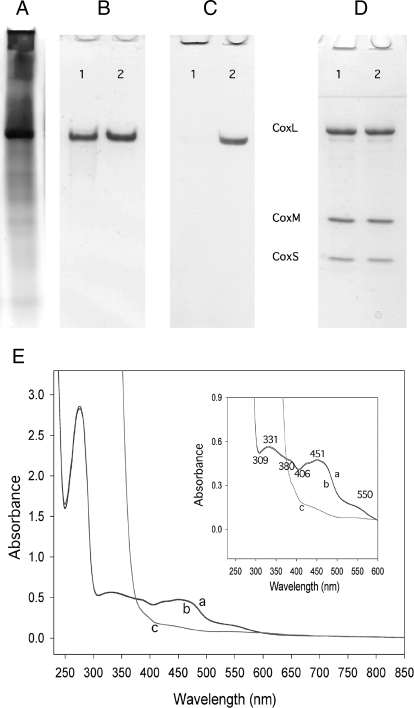

CO Dehydrogenase Purified from the D::km Mutant—In agreement with the inability to utilize CO as a growth substrate, cell-free extracts prepared from the induced D::km mutant could not catalyze the oxidation of CO, although on native PAGE a protein band was visible, which corresponds to the catalytically active CO dehydrogenase from wild-type O. carboxidovorans (Fig. 4A). Apo-CO dehydrogenase was purified 17-fold with a yield of ∼44% (supplemental Table S1). The absence of major contaminating protein bands on native PAGE shows that the apo-enzyme was obtained with reasonable purity (Fig. 4B, lane 1). The enzyme amounted to ∼6% of the total cell protein and ∼11% of the cytoplasmic fraction. The mobilities of apo- and wild-type CO dehydrogenase upon native PAGE were indistinguishable (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 and 2), suggesting the same quaternary structure. Activity staining indicated that the CO dehydrogenase purified from the mutant cannot oxidize CO (Fig. 4C, lanes 1 and 2). In addition, the specific CO-oxidizing activity of the apo-enzyme was below the detection limit of the photometric assay (0.02 unit/mg).

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of CO dehydrogenase purified from O. carboxidovorans OM5 D::km. A, cell-free crude extract (15 μg) of O. carboxidovorans OM5 D::km grown with H2, CO2, CO, and air (as detailed in the legend to Fig. 3) was analyzed on native PAGE. B, native PAGE stained for protein with Coomassie Brilliant Blue of CO dehydrogenase purified from the mutant (lane 1) or from wild-type bacteria (lane 2). C, native PAGE stained for CO oxidizing activity with CO and 1-phenyl-2-(4-iodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium chloride of CO dehydrogenase purified from the mutant (lane 1) or from wild-type bacteria (lane 2). D, denaturing PAGE stained for protein of CO dehydrogenase purified from the mutant (lane 1) or from wild-type bacteria (lane 2). Each lane contained 15 μg of CO dehydrogenase. CoxL, CoxM, and CoxS are the CO dehydrogenase subunits. E, UV-visible absorption spectra of apo-CO dehydrogenase: air-oxidized, trace a; reduced with pure CO for 30 min, trace b; reduced with 650 μm dithionite under N2 for 4 min, trace c. The inset shows the visible part of the spectra, including characteristic wavelengths (in nanometers). For experimental details refer to the “Experimental Procedures.”

The polypeptides CoxM, CoxS, and CoxL from apo- and wild-type CO dehydrogenase showed the same electrophoretic mobilities and stoichiometries (Fig. 4D, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that the apo-enzyme has the right subunit structure. The identity of the apo-enzyme as CO dehydrogenase was also apparent from the right N-terminal amino acid sequences of its subunits (CoxM, MIPGSFDYHR; CoxS, -AKAHIELTIN; and CoxL, -NIQTTVEPTS). In summary, these data indicate that the coxD function is related to the proper biosynthesis of a catalytically competent CO dehydrogenase and not to the translation, folding, or proper assembly of the CoxMSL polypeptides.

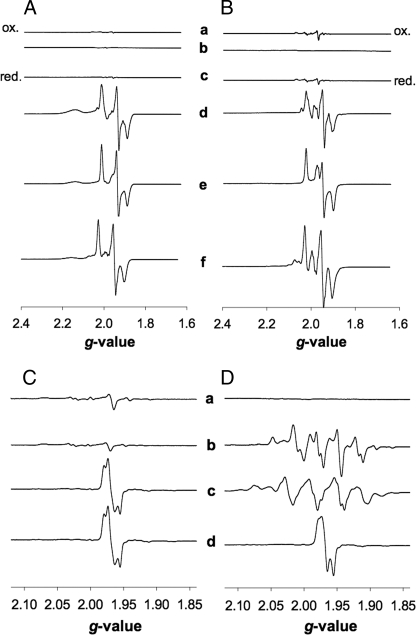

The air-oxidized or dithionite-reduced absorption spectra of CO dehydrogenase from wild-type (data not shown) or mutant were indistinguishable (Fig. 4E). This indicates the presence of redox-active FAD and iron-sulfur clusters in the apo-enzyme. The apo-enzyme was not bleached in the presence of CO (Fig. 4E), which indicates that neither the iron-sulfur centers nor the flavin cofactors were reduced. That the iron-sulfur centers in apo-CO dehydrogenase do not receive electrons from CO is also apparent from EPR spectroscopy (Fig. 5). Reduction of the apo-enzyme with CO at 16 K or 50 K did not produce the rhombic paramagnetic signals characteristic of the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 5, A and B, traces c and d), although dithionite was able to generate them (Fig. 5, A and B, traces e and f). These data suggest that the apo-CO dehydrogenase is complete in the intramolecular electron transport but impaired in the oxidation of CO.

FIGURE 5.

Analysis by EPR of iron-sulfur (A and B) and molybdenum (C and D) in CO dehydrogenase from mutant and wild type. Samples in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, contained 11.6 mg of protein/ml. Microwave frequency, modulation amplitude, and microwave power were 9.47 GHz, 1 millitesla, and 10 milliwatts, respectively. Spectra were recorded at 16 K (A), 50 K (B), and 120 K (C and D). A and B: traces a and b, air-oxidized; c and d, CO-reduced; e and f, reduced with 5 mm sodium dithionite; traces a, c, and e, CO dehydrogenase D::km; b, d, and f, wild-type CO dehydrogenase 23 units/mg. C, apo-CO dehydrogenase and wild-type (D). Traces a, air-oxidized; b, CO-reduced; c, reduced with 5 mm sodium dithionite; d, treated with 5 mm KCN for 24 h to remove cyanolysable sulfur and then reduced with 5 mm sodium dithionite.

Active Site Structure of Apo-CO Dehydrogenase—At this stage of our research the [CuSMoO2] cluster became the prime target for the analysis of the coxD function. The apo-CO dehydrogenase was complete in molybdenum (2.04 ± 0.20 mol per mol of enzyme), but deficient in copper (0.01 ± 0.01 per mol of enzyme) and deficient in the μ2 sulfur bridging molybdenum and copper (0.13 ± 0.02 mol of cyanolysable sulfur per mol of apo-enzyme). In the air-oxidized state apo- and wild-type CO dehydrogenase showed no paramagnetic molybdenum EPR signal (Fig. 5, C and D, trace a). The characteristic complex EPR spectrum generated by CO from the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 5D, trace b) was not apparent in the apo-enzyme, which remained EPR silent (Fig. 5C, trace b). Apparently, CO is not capable to reduce Mo(VI) to Mo(V) in the catalytic site of apo-CO dehydrogenase. Dithionite generated a paramagnetic Mo(V) signal in the apo- (Fig. 5C, trace c) as well as the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 5D, trace c). The “desulfo”-type signal elicited by the apo-enzyme (Fig. 5C, trace c) refers to an MoO3 ion (Fig. 5D, trace d) in place of a functional [CuSMoO2] center (Fig. 5D, trace c).

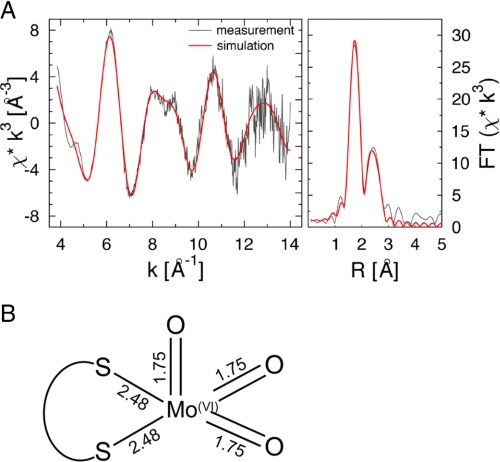

XAS of apo-CO dehydrogenase showed an [MoO3] site with minor contributions of an [MoO2S] site (Fig. 6, A and B). Molybdenum is coordinated by five ligands: 2.6 O at a distance of 1.75 Å, two S at 2.48 Å, and 0.4 S at a distance of 2.34 Å (Fig. 6B and supplemental Table S2). Chemical analysis of the enzyme batch employed for XAS revealed a cyanolysable sulfur content of 0.19 ± 0.07 mol S per mol of molybdenum and no copper. About 60% or 80-93% of the molybdenum in apo-CO dehydrogenase is formed as a [MoO3] center based on XAS or chemical analysis, respectively. The assignment of a third sulfur with long distance and low occupancy can be challenged by the interpretation of two short oxygen and one longer hydroxy/water ligand, because such a “labile” oxygen might be imagined as the point of sulfur transfer during the maturation of the binuclear cluster. However, the refinement of the apo-CO dehydrogenase EXAFS spectra does not support this idea. The fit index of 2.2921 for the long sulfur model is much better than 2.7428 of the long hydroxy model. In addition, the Debye-Waller parameter for the oxo-groups of 2σ2 = 0.0026(4) Å is smaller than the one observed in wild-type CO dehydrogenase (10), whereas the Debye-Waller parameter for the sulfur ligands of 2σ2 = 0.012(2) Å is more than twice the one of the wild-type enzyme. We feel confident that such an asymmetric disorder within the first shell is not very likely.

FIGURE 6.

Mo-K-edge EXAFS and corresponding Fourier transforms of CO dehydrogenase purified from O. carboxidovorans OM5 D::km. Experimental data are shown by black lines; calculated spectra are shown by red curves (A). Bond lengths are in Å (B).

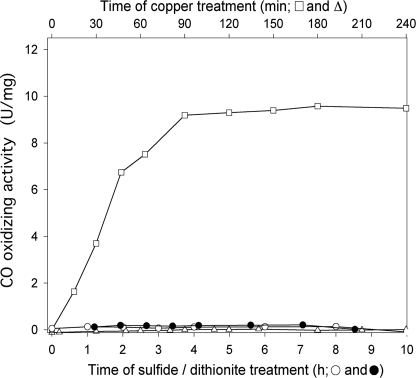

The catalytically competent [CuSMoO2] cluster could be reconstructed from the [MoO3] site in the apo-enzyme through resulfuration followed by introduction of copper, which rescued the CO oxidizing activity of the enzyme (Fig. 7). Treatment with copper first and then with sulfide or with copper exclusively did not restore enzyme activity (Fig. 7). The chemistry of cluster reconstruction suggests that the sulfur must go in first, followed by the copper ion. It is apparent that the coxD gene product is required for the maturation of the [CuS-MoO2] cluster, particularly to allow for the introduction of the μ2 S and the copper.

FIGURE 7.

Functional reconstruction of the non-functional [MoO3]-center in CO dehydrogenase D::km. Apo-CO dehydrogenase (2.4 mg/ml) was subjected to the following treatments: ○, sodium sulfide and sodium dithionite (5 mm each); •, 125 μm Cu+-thiourea first and then with sulfide plus dithionite; ▵, 125 μm Cu+-thiourea; and □, sodium sulfide and dithionite (5 mm each) followed by 125 μm Cu+-thiourea.

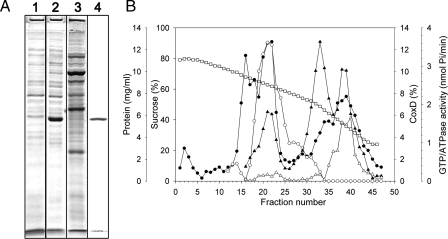

Properties of CoxD—We have achieved the heterologous expression of CoxD in E. coli K38 pGP1-2/pETMW2 at 38% of the total cell protein (Fig. 8A). The considerably high expression level has apparently hindered the formation of soluble CoxD, and the recombinant protein appeared entirely in inclusion bodies. The molecular mass of the recombinant CoxD polypeptide (34 kDa) apparent from SDS-PAGE (Fig. 8A) is similar to 33.5 kDa deduced from the sequence. CoxD resides in the cytoplasmic membrane of O. carboxidovorans and is absent from the cytoplasm (Fig. 8, A and B). The occurrence of CoxD in membranes coincided with GTPase activity, whereas ATPase activity in membranes was insignificant (Fig. 8B). NTPase (ATP and GTP) activity was present in crude preparations of recombinant CoxD solubilized from inclusion bodies with N-lauroylsarcosine. No CoxD-specific immunological signals could be detected in membranes or cytoplasm of O. carboxidovorans grown with H2 or pyruvate, or in the CO-induced mutant D::km. Because CoxD has not been purified in a functional state, speculations about its role as an AAA+ ATPase chaperone and other possible functions are mainly confined to knowledge of its primary sequence.

FIGURE 8.

Recombinant CoxD of E. coli K38 pGP1-2/pETMW2 and subcellular localization of CoxD in O. carboxidovorans. A, formation of recombinant CoxD in E. coli K38 pGP1-2/pETMW2 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE of crude extracts (lanes 1 and 2). Bacteria grown for 210 min to A600 of 0.75 (lane 1; 20 μg of protein) were supplied with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside and grown for further 55 min at 30 °C. Then, T7 RNA polymerase was induced by raising the temperature to 42 °C for 90 min, and bacteria (A600 = 3.95) were analyzed for the formation of recombinant CoxD polypeptide (lane 2; 30 μg of protein). Cytoplasmic membranes of O. carboxidovorans (60 μg per lane) grown with H2, CO2, and CO were stained for protein on SDS-PAGE (lane 3) and analyzed for the presence of CoxD employing anti-CoxD IgG antibodies (lane 4). For details refer to the methods section. B, cell-free crude extracts of O. carboxidovorans were centrifuged in a sucrose density gradient (□) and analyzed for protein employing the Biuret-reaction (•), for CoxD by Western blotting (○), and for ATPase (▵) or GTPase (▴) activity by quantitation of inorganic phosphate.

DISCUSSION

Biogenesis of the [CuSMoO2] Cluster—The CO dehydrogenase of the coxD mutant suggests that the [CuSMoO2] cluster is assembled stepwise at the catalytic site of an apoenzyme, which is completely folded, fully assembled, and contains all relevant cofactors except the bimetallic cluster. This situation is contrasted by other enzyme systems where the metal cofactor is separately formed in a multistep process outside of its target protein. For example, the FeMo-cofactor of dinitrogenase is first assembled outside of the enzyme by specialized biosynthetic machinery and then incorporated into the cofactor-deficient apo-enzyme generating the catalytically competent dinitrogenase (34). FeMo-cofactor biosynthesis involves (i) formation of an Fe-S core, (ii) rearrangement of the core to an entity that is topologically similar to the metal-sulfur core of FeMo-cofactor, (iii) insertion of molybdenum and attachment of homocitrate, and (iv) trafficking of FeMo-cofactor or its precursors among the various sites at which these events occur (35). The process employs molecular scaffolds (NifU, NifB, and NifEN) where FeMo-cofactor is stepwise assembled, metallocluster carrier proteins (NifX and NafY) that carry FeMo-cofactor precursors between assembly sites in the pathway, and enzymes (NifS, NifQ, and NifV) that provide sulfur, molybdenum, and homocitrate for cofactor synthesis (34, 35).

The CO dehydrogenase-related xanthine dehydrogenase from wild-type Rhodobacter capsulatus or mutants defective in Mo-cofactor biosynthesis did not co-migrate upon electrophoresis, which led the authors to conclude that the conformation of the immature enzyme has been altered and that the complete Mo-cofactor, including the sulfur, is put together before the assembly and correct folding of the enzyme (36). In the maturation of Rhodobacter xanthine dehydrogenase, the XdhC protein entails binding of the molybdenum cofactor and its insertion into the XdhB subunit of the enzyme. XdhC promotes the exchange of one of the two equatorial oxygen ligands of the molybdenum by a sulfur through interaction with the l-cysteine desulfurase NifS4. The latter transfers the sulfur from cysteine to molybdenum cofactor-bound XdhC, before its insertion into the enzyme (37-39). A significant homologue of xdhC is apparently absent from the cox gene cluster or the entire megaplasmid pHCG3 of O. carboxidovorans. The chromosome of O. carboxidovorans reveals three potential xdhC genes: one is clustered with predicted xanthine dehydrogenase structural genes (xdhA and xdhB), and the other two are grouped with a potential molybdopterin-binding protein. In contrast to Rhodobacter xanthine dehydrogenase, the same mobilities of CO dehydrogenase and apo-CO dehydrogenase upon native PAGE (Fig. 4) suggest unchanged conformations. Other than with external cofactor biosynthesis, the assembly of the [CuSMoO2] cluster presumably involves apo-CO dehydrogenase as an internal molecular scaffold for the insertion of sulfur and copper. This paper identifies CoxD as another principal player in the assembly of the bimetallic cluster. Predictions from the amino acid sequence, which are consistent with the available information, support the hypothesis that CoxD serves as an AAA+ ATPase chaperone to partially unfold the large subunit (CoxL) in an NTP (presumably GTP)-dependent manner, thereby making the buried [MoO3] center accessible to the sequential introduction of sulfur and copper. CoxD is particulate and apo-CO dehydrogenase is cytoplasmic, which suggests that the maturation of CO dehydrogenase proceeds at the inner aspect of the cytoplasmic membrane. All AAA+ ATPases are usually found in various multimeric states (40). It would not be surprising if, in analogy to BchI of Mg2+-chelatase, CoxD also forms a hexameric ring complex (41). Furthermore, the VWA binding site on CoxD and the VWA/MIDAS domain present on CoxE would allow for higher complex formation and functional cooperation of the two proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Vitali Svetlitchnyi (Microbiology, University of Bayreuth) for assistance with EPR spectroscopy. One of us (A. P.) thanks Marcus Resch (Microbiology, University of Bayreuth) for advice with respect to chemical reconstitution.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2, Tables S1 and S2, and references.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; VWA, von Willebrand Factor A; XAS, X-ray absorption spectroscopy; ORF, open reading frame; SRH, second region of homology; MIDAS, metal ion dependent adhesion site; Xdh, xanthine dehydrogenase; OD, optical density.

References

- 1.Auling, G., Busse, J., Hahn, M., Hennecke, H., Kroppenstedt, R., Probst, A., and Stackebrandt, E. (1988) Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 10 264-272 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer, O. O. (2005) in Bergey′s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (Garrity, G. M., ed) pp. 468-471, vol. 2, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuhrmann, S., Ferner, M., Jeffke, T., Henne, A., Gottschalk, G., and Meyer, O. (2003) Gene (Amst.) 322 67-75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul, D., Bridges, S., Burgess, S. C., Dandass, Y., and Lawrence, M. L. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190 5531-5532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santiago, B., Schübel, U., Egelseer, C., and Meyer, O. (1999) Gene (Amst.) 236 115-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schübel, U., Kraut, M., Mörsdorf, G., and Meyer, O. (1995) J. Bacteriol. 177 2197-2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meyer, O., Frunzke, K., Mörsdorf, G., Murrel, J. C., and Kelly, D. P. (eds) (1993) Microbial Growth on C1 Compounds, Intercept, Andover, MA, pp. 433-459

- 8.Dobbek, H., Gremer, L., Meyer, O., and Huber, R. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 8884-8889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobbek, H., Gremer, L., Kiefersauer, R., Huber, R., and Meyer, O. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 15971-15976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gnida, M., Ferner, R., Gremer, L., Meyer, O., and Meyer-Klaucke, W. (2003) Biochemistry 42 222-230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, J. L., Rajagopalan, K. V., and Meyer, O. (1990) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 283 542-545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gremer, L., Kellner, S., Dobbek, H., Huber, R., and Meyer, O. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 1864-1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer, O., Frunzke, K., Gadkari, D., Jacobitz, S., Hugendieck, I., and Kraut, M. (1990) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 87 253-260 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Resch, M., Dobbek H., and Meyer, O. (2005) J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 10 518-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer, O., Stackebrandt, E., and Auling, G. (1993) Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 16 390-395 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer, O., and Schlegel, H. G. (1983) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37 277-310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russel, M., and Model, P. (1984) J. Bacteriol. 159 1034-1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F., and Maniatis, T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY

- 19.Santiago, B., and Meyer, O. (1997) J. Bacteriol. 197 6053-6060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon, R., Priefer, U., and Pühler, A. (1983) Biol. Technol. 1 7784-7790 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arps, P. J., and Winkler, M. E. (1986) J. Bacteriol. 169 1061-1070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kraut, M., Hugendieck, I., Herwig, S., and Meyer, O. (1989) Arch. Microbiol. 152 335-341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradford, M. M. (1976) Anal. Biochem. 72 248-254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beisenherz, G., Boltze, H. J., Bücher, T. R., Czok, K., Garbade, H., Meyer-Arendt, E., and Pfleiderer, G. (1953) Z. Naturforschg. 8 555-577 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer, O., and Rajagopalan, K. V. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259 5612-5617 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cardenas, J., and Mortenson, L. E. (1974) Anal. Biochem. 60 372-381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chifflet, S., Torriglia, A., Chiesa, R., and Tolosa, S. (1988) Anal. Biochem. 168 1-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snider, J., and Houry, W. A. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 156 200-209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanson, P. I., and Whiteheart, S. W. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6 519-529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fodje, M. N., Hansson, A., Hansson, M., Olsen, J. G., Gough, S., Willows, R. D., and Al-Karadaghi, S. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 311 111-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibson, L. C. D., Jensen, P. E., and Hunter, C. N. (1999) Biochem. J. 337 243-251 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo, M., Weinstein, J. D., and Walker, C. J. (1999) Plant Mol. Biol. 41 721-731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dos Santos, P. C., Dean, D. R., Hu, Y., and Ribbe, M. W. (2004) Chem. Rev. 104 1159-1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rubio, L. M., and Ludden, P. W. (2008) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 62 93-111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leimkühler, S., and Klipp, W. (1999) J. Bacteriol. 181 2745-2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumann, M., Stöcklein, W., Walburger, A., Magalon, A., and Leimkühler, S. (2007) Biochemistry 46 9586-9595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neumann, M., Stöcklein, W., and Leimkühler, S. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 28493-28500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schumann, S., Saggu, M., Möller, N., Anker, S. D., Lendzian, F., Hildebrandt, P., and Leimkühler, S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 16602-16611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vale, R. D. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150 F13-F19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Willows, R. D., Hansson, A., Birch, D., Al-Karadaghi, S., and Hansson, M. (2004) J. Struct. Biol. 146 227-233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.