Abstract

Recordings of rat hippocampal place cells have provided information about how the hippocampus retrieves memory sequences. One line of evidence has to do with phase precession, a process organized by theta and gamma oscillations. This precession can be interpreted as the cued prediction of the sequence of upcoming positions. In support of this interpretation, experiments in two-dimensional environments and on a cue-rich linear track demonstrate that many cells represent a position ahead of the animal and that this position is the same irrespective of which direction the rat is coming from. Other lines of investigation have demonstrated that such predictive processes also occur in the non-spatial domain and that retrieval can be internally or externally cued. The mechanism of sequence retrieval and the usefulness of this retrieval to guide behaviour are discussed.

Keywords: oscillation, phase precession, retrieval, entorhinal cortex

1. Introduction

The theme of this special issue is the topic of prediction. There is now strong evidence that the activity in the rodent hippocampus can reflect predictive information about potential future events and places, particularly of the order of several seconds in the future. Moreover, while animals can predict outcomes in simple conditioning tasks without a hippocampus (Corbit & Balleine 2000), the hippocampus is necessary for the predictions that involve novel sequences or temporal gaps (O'Keefe & Nadel 1978; Dusek & Eichenbaum 1998; Redish 1999), particularly when this prediction requires the integration of spatially and temporally separated information (Cohen & Eichenbaum 1993; Redish 1999). In this paper, we will review the evidence that hippocampal representations show predictive sequences during behaviours that depend on hippocampal integrity.

In a general sense, any memory could contribute to the ability to form predictions, but the memory of sequences has special usefulness. Suppose that the sequence ABC has occurred in the past. The subsequent appearance of A can serve as a cue for the recall of this sequence. To the extent that a sequence that has been observed once will tend to recur, the cued recall of BC is a prediction that BC is likely to happen next.

Research on the role of the hippocampus in memory sequences has progressed rapidly over the last decade owing to three major developments. First, it has now become standard to monitor a large number of neurons in awake, behaving rats (Wilson & McNaughton 1993; Buzsaki 2004). Second, new developments in analytical methods have enabled the study of how neural ensembles represent space on a fast time scale, thereby eliminating the need to average over long, potentially variable time frames (Brown et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1998; Johnson et al. 2008, 2009). Third, it is now clear that the hippocampus cannot be understood solely in terms of a simple rate code. Rather, important additional information is encoded by a temporal code in which cellular firing is organized by oscillations in the theta (7–10 Hz) and gamma (40–100 Hz) range.

We will begin by describing these oscillations and the way they organize information. We will then review the experimental evidence that the hippocampus retrieves memory sequences and can use this information to guide behaviour. We then turn to open questions, such as the mechanism of sequence retrieval, how far in the future the hippocampus can predict and whether there is a ‘constructive’ form of prediction about situations that have not previously occurred.

2. Theta/gamma phase code and phase precession

The oscillations of the hippocampus are easily observed in the local field potential of the rat. These oscillations depend strongly on behavioural state (Vanderwolf 1971; O'Keefe & Nadel 1978; Buzsaki 2006). During movement, the local field potential is primarily characterized by strong oscillations in the theta frequency range (7–10 Hz). At the same time, there is also a faster oscillation in the gamma frequency range (40–100 Hz; Bragin et al. 1995). These dual oscillations are shown schematically in figure 1. By contrast, during slow-wave sleep and inattentive rest, the local field potential is characterized by a broader frequency distribution and much less prominent theta and gamma. This state (termed large-amplitude irregular activity (LIA)) is punctuated by brief events called sharp waves. Although pauses characterized by inattention (eating, grooming, resting) tend to show LIA, pauses characterized by active attention (e.g. during anxiety, fear, decision making) show continued theta (Vanderwolf 1971; O'Keefe & Nadel 1978; Gray & McNaughton 2000; Johnson & Redish 2007). As we will see below, certain types of memory processes only occur during periods of theta oscillations.

Figure 1.

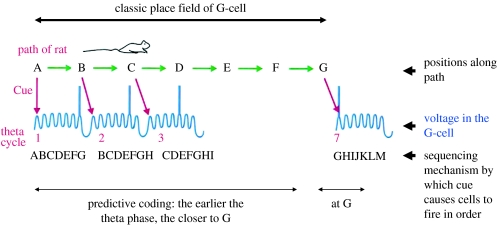

Schematic illustrating theta phase precession. The place field of the illustrated cell covers a small part of a path; this part is labelled by successive letters of the alphabet—the firing starts at A and stops when the rat moves past G. Voltage (intracellular) traces show successive theta cycles (nos. 1–7) each of which has seven gamma subcycles. Firing occurs near the peak of a gamma cycle and with earlier and earlier theta phase as the rat runs from left to right. This is termed phase precession. The precession process can be understood as resulting from a sequencing (chaining) mechanism within each theta cycle in which the cue (current position) triggers sequential readout from different cells representing successive positions (e.g. A–G) along the path. This is termed a sweep. The cell illustrated represents the position G. Firing at positions A–F is predictive of the rat being at G.

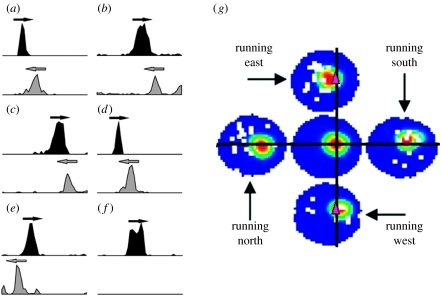

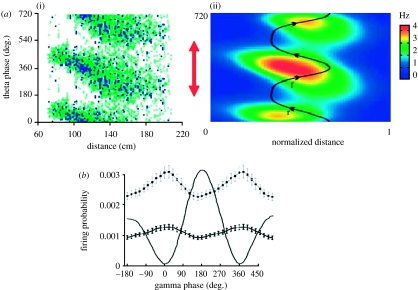

When one uses firing rate as an indicator of cell activity, that activity defines the place field of the place cell. This field is generally a relatively small fraction of the environment (middle panel, figure 3g). The place fields of different cells occur in different locations; thus, the place cells collectively code for the animal's position within an environment. Two lines of evidence, however, indicate that this description is incomplete. Place cells sometimes fire spikes outside their main place fields, for example, at feeder sites (O'Keefe & Nadel 1978; Jensen & Lisman 2000; Jackson et al. 2006) and at decision points (Johnson & Redish 2007). As will be discussed later, this additional firing (extra-field firing) may actually reflect information processing (‘thinking’) about a different location—that of the cell's main place field rather than the animal's current location. The second line of evidence relates to the aspects of neural coding that go beyond what can be accounted for by a rate code. As a rat crosses the place field of a cell, the firing shows temporal coding: spikes fire with a systematic timing (phase) relationship to ongoing theta oscillations. Moreover, this relationship changes as the rat moves through the place field, a phenomenon known as ‘phase precession’ (O'Keefe & Recce 1993; Skaggs et al. 1996; Dragoi & Buzsaki 2006; Maurer & McNaughton 2007). This phenomenon is shown in figure 2a and illustrated schematically in figure 1. If a rat moves through a place field at average velocity, firing occurs during approximately 8–12 theta cycles (i.e. a total duration of approx. 1–2 s; Maurer & McNaughton 2007). Phase precession is most clearly seen on linear tracks as the rat runs through the place field. The cell initially fires during late phases of the theta cycle, but on each successive theta cycle, firing occurs at an earlier and earlier phase. Models of phase precession have suggested that phase precession contains both retrospective and prospective (predictive) components. As we will review later, it has now been definitively shown that the phase precession has a predictive component.

Figure 3.

Predictive or retrospective aspect of place field firing. (a–f) Firing rate as a function of position for rats running leftwards or rightwards on a linear track (as indicated by arrows). (a–d) Examples of prospective coding (the position being predicted is at the overlap of the arrows and is termed the ‘true place field’). (e) Example of retrospective coding. Adapted from Battaglia et al. (2004). (g) Predictive coding is a two-dimensional environment. The size of the environment is indicated in blue and shown five times for different conditions. The central version indicates the concept of the classic place field, the rat explores the environment through motions in all directions and firing rate is indicated in a colour code (red indicates the highest). The place field is centred in the red region. Peripheral plots show firing rate computed for undirectional passage through the region. Predictive coding is illustrated by the fact that when running east, most spikes are to the left of the black line, whereas when running west, they are to the right. The cell can be thought of predicting arrival to the region marked by pink triangles. This region would constitute the ‘true place field’. Adapted from Huxter et al. (2008).

Figure 2.

Phase locking of spikes to gamma and theta oscillations. (a(i)) As a rat moves through a place field (distance), theta phase systematically changes over 360° (red arrow). Green dots, all spikes; blue dots, during high gamma power. (ii) Averaged data from many cells with colour code for rate. Phase is plotted against normalized distance through the place field. (b) During theta phase precession, spiking is gamma locked. Closed circles indicate probability of spiking as a function of gamma phase when the rat is in the place field. The gamma waveform in the field potential is plotted as a solid line. Adapted from Senior et al. (2008).

An issue that determines the information capacity of a phase code is how finely the phase of theta can be divided. Recent experimental work strongly supports the theoretical suggestion that the coding scheme used by the hippocampus is a theta/gamma discrete phase code (Lisman & Idiart 1995; Lisman 2005). According to this hypothesis, the gamma oscillations that occur during a theta cycle themselves control firing (i.e. firing can occur at only a restricted phase of a gamma cycle). Thus, there will be approximately 5–14 gamma cycles in each theta cycle (7/40–100 Hz) and this will result in a corresponding number of discrete times at which firing may occur. Consistent with this hypothesis, recent work (figure 2b) has found that the firing of hippocampal pyramidal cells is gamma modulated while the theta phase precession is occurring (Senior et al. 2008). The cells that fire during a given gamma cycle define an ensemble (i.e. a spatial code for a memory item). Overall, then, approximately 5–14 items can be coded for during a theta cycle, each in a given gamma subcycle of a theta cycle. This coding scheme provides a framework for understanding the phase precession in the hippocampus (see below), but may also be related to the capacity limits of working memory networks in cortex (Lisman & Idiart 1995).

3. Prospective coding: predicting upcoming places

Soon after phase precession was discovered, it was suggested that the phenomenon implies a process in which the represented location sweeps across positions in the direction of travel (Skaggs et al. 1996). Two early models specifically proposed that phase precession should be interpreted as a sweep ahead of the animal (Jensen & Lisman 1996; Tsodyks et al. 1996).

An important aspect of this interpretation (figure 1) is that the spatial resolution of the system is much finer than the size of the place field: the ‘true place field’ (which we designate here by a letter) is taken to be approximately one-seventh the size of the apparent place field (the entire field where rate is elevated). Thus, we can think of positions A, B, C, D, E, F and G as seven subparts of an apparent place field (with different cells representing each position and firing in different gamma cycles of the theta cycle). As will be explained in the following paragraphs, the firing of the ‘G-cell’ illustrated in figure 1 at positions A–F is actually a prediction about the distance to the true place field, G.

To further clarify this interpretation, let us first consider what happens during a single theta cycle, a phenomenon we term a ‘sweep’. Suppose that one is recording from a cell representing position G ahead of where the rat is now (position A). It might at first seem that this cell should not fire until the animal gets to G, however, in the context of a predictive process based on phase coding, firing of the G-cell at position A at late theta phases can be understood as a prediction that the rat is approaching G. The process that causes the G-cell to fire when the animal is at position A can be understood mechanistically as a chaining process that occurs within a theta cycle: if the rat is at position A, the cells representing position A are cued to fire at the beginning of the theta cycle (i.e. in the first gamma cycle). The chaining process then fires the next cells in the spatial sequence (these represent position B and fire in the second gamma cycle). This chaining process continues until the G-cell fires at the end of the theta cycle (in the last gamma cycle within the theta cycle). There is thus a sweep of activity from location A to location G during this theta cycle.

A key to understanding the phase precession is that the cue will change over time as the animal runs; this will change the character of sweeps in successive theta cycles. Thus, when the second theta cycle occurs, the rat will have proceeded farther along and so is now at B. Given that B is now the cue, the sweep that occurs in the second theta cycle will be BCDEFGH. It can be seen that whereas in the first theta cycle, the G-cell fired in the last gamma cycle, in the second theta cycle, the G-cell now fires in the next to last gamma cycle, i.e. with earlier theta phase. It thus follows that as long as the rat keeps moving, the G-cell will fire with earlier and earlier phase on each successive theta cycle.

4. Evidence for prospective coding in the hippocampus

In support of this interpretation, several experiments show that many spikes fired by place cells actually represent a position ahead of the animal. First, studies of phase precession in cells with omnidirectional place fields have shown that firing during the late components of theta (early firing in a pass through the place field, i.e. the predictive components) fire as the animal approaches a specific location from any direction. That is, as the animal approaches the position from the left, these spikes are fired to the left of the point; as the animal approaches the position from the right, these spikes are fired to the right of that point. This has been seen (figure 3) on both the cue-rich one-dimensional linear track (Battaglia et al. 2004) and in the standard two-dimensional cylinder foraging task (Huxter et al. 2008). These experiments suggests that the information about position implicated by firing of the cell (the true place field of the cell) is actually a small central point corresponding to where the rat is during the firing at early phases of the theta cycle (the central portion of the classic omnidirectional place field in two-dimensional, the later portion of the unidirectional place field in one-dimensional).

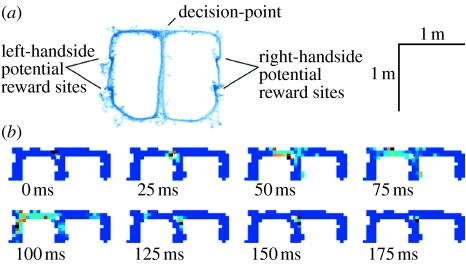

Second, Johnson & Redish (2007) found that when a rat comes to a difficult choice point on a maze and shows evidence of searching behaviour (the animal alternately looks left and right, a behaviour termed vicarious trial and error (VTE); Meunzinger 1938; Tolman 1939), neural ensembles within the hippocampus encode future positions ahead of the animal (figure 4). During these behavioural pauses, the animal appears attentive to its surroundings and the hippocampal local field potential remains in the theta state (Vanderwolf 1971; O'Keefe & Nadel 1978; Johnson & Redish 2007). Decoding represented positions from hippocampal ensembles showed that there are sweeps of firing that represent successive positions along one or the other arms of the maze. These sweeps show directionality away from the choice point (figure 4). These sweeps can be interpreted analogously to the prospective cued-chaining interpretation of phase precession reviewed in the preceding section. In the cued-chaining interpretation, the observed phase precession is a series of sweeps (ABCDEFG, BCDEFGH, etc.) in which each sweep is a predictive process that differs from the preceding one because of a changing cue. The sweeps observed by Johnson and Redish may be single instances of one of these chained sequences.

Figure 4.

Decoded hippocampal neural ensembles at a choice point shows a sweep to the left, progressing from a decision point, around a corner to a goal location through the course of 140 ms. (a) All position samples from a cued-choice task. (b) Decoded representations at fine time scales. Colour indicates posterior decoded probability. White crosses indicate location of the animal. Adapted from Johnson & Redish (2007).

Finally, on tasks with highly repeated paths (such as running back and forth on a linear track, or running around a circular track), place fields expand backwards along the direction of travel, such that on later laps within a day, the place field gains a leader region in front of the place field that was seen on the first laps. This is termed place field expansion (Blum & Abbott 1996; Mehta et al. 1997). It has now been established that place field expansion does not cause phase precession—place field expansion can be inhibited, while leaving the basic phase precession intact (Shen et al. 1997; Ekstrom et al. 2001). The effect of place field expansion is to lengthen the first part of the phase precession, which can be viewed as the learned ability to predict yet further ahead in each theta cycle (Blum & Abbott 1996; Mehta et al. 1997; Redish & Touretzky 1998; Redish 1999; Jensen & Lisman 2005). This means that as the animal repeatedly observes regular sequences, the sweeps occurring during each theta cycle reach further into the future (ABCDEFGHIJ instead of just ABCDEFG), allowing an earlier prediction of approach to a location.

5. Manipulating the spatial cue for sequence recall

The interpretation of the phase precession as reflecting a cued sequence recall process depends on the assumption that the retrieval process is cued on each theta cycle by the current position of the rat (figure 1). It follows that the phase precession should depend on the velocity of the rat. Suppose, for instance, that the rat ran so fast that by the second theta cycle it was already at G. In this case, proper prediction would imply that firing should occur only on two theta cycles and the entire change in phase (from late to early) should occur in two theta cycles. Consistent with this, systematic study of the velocity dependence of phase precession indicates that phase precession is more accurately described by spatial rather than temporal traversal (O'Keefe & Recce 1993; Skaggs et al. 1996; Geisler et al. 2007; Maurer & McNaughton 2007). At average velocity, the phase advance is equivalent to 0.5–1 gamma period per theta cycle; when the rat runs slower, the phase advance is less and when the rat runs faster, the phase advance is greater.

A further test of the importance of changing cues is to put the rat in a running wheel. If the phase precession is due to internal dynamics, to proprioceptive feedback from running, or even from some general motivational or speed-of-travel signal, phase precession should still occur. However, if phase precession is primarily driven by an updating of current position cues, then phase precession should be abolished. Recordings from Buzsaki's laboratory (Czurko et al. 1999; Hirase et al. 1999) found that under simple conditions, phase precession vanished on the running wheel—instead, individual cells fired at a set phase of theta.

6. Phase precession in the non-spatial domain

The ease with which the spatial location of the rat can be studied can lead to the impression that the rat hippocampus is uniquely processing spatial information rather than being a general purpose memory device. However, lesion experiments in rats indicate that the hippocampus is also necessary for the memory of non-spatial (odour) sequences (Fortin et al. 2002; Manns et al. 2007, but see also Dudchenko et al. 2000). This helps to bring together the rat literature with the human one, where the hippocampus clearly has a role in many non-spatial aspects of episodic memory (reviewed in Cohen & Eichenbaum 1993).

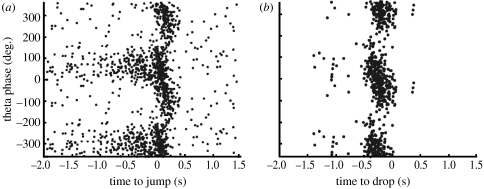

Two recent studies have demonstrated phase precession in the rat in the non-spatial domain. In the first of these studies (Lenck-Santini et al. 2008), the rat was removed from a ledge and dropped (see also Lin et al. (2005) for a non-predictive comparison). Within a certain time, the rat had to jump back on the ledge to avoid a shock. Theta oscillations and phase precession were observed after the rat was picked up (just before being dropped) and again in the short period just before the rat jumped to avoid the shock (figure 5). This non-spatial phase precession can be interpreted as a prediction of being dropped and a prediction of jumping. An alternative interpretation of the first finding that the rat was predicting where it was going to be dropped was rejected because the same firing occurred irrespective of where in the environment the rat was dropped.

Figure 5.

Phase precession in a non-spatial domain. (a) Theta firing phase varies with time before the rat jumps to avoid a shock. (b) Theta firing phase varies with time before the rat is dropped. From Lenck-Santini et al. (2008).

In the second of these studies (Pastalkova et al. 2008), a rat had to run on a running wheel for a short period during the delay period of a working memory task. When the rat was allowed to leave the running wheel, it could complete its path to a reward site that alternated between trials. During the brief period on the running wheel, phase precession occurred (compare the previous finding that no phase precession occurs if the rat is simply running indefinitely on the wheel). The phase precession in these experiments can be interpreted as using time as a cue (or, equivalently, as traversing a sequence of internally generated states; Levy 1996; Levy et al. 2005) and what is being predicted is a future event (i.e. being dropped, jumping, getting off the wheel). According to this interpretation, on each successive theta cycle, the (internal) temporal cue is advanced (just as the spatial cue is advanced during running on the linear track); thus, the chaining process on each successive theta cycle leads to earlier and earlier theta phase firing of the cells representing the event.

7. Usefulness of sequence retrieval to guide behaviour

There is now begining to be evidence that the predictions that occur during sweeps are actually used by the animal to guide behaviour. Johnson & Redish (2007) found that the direction of the sweep was strongly correlated with the direction of the animal's motion, but was not necessarily correlated with the final decision made. Johnson and Redish also found that these sweeps occurred at decision points and during error correction when animals were performing VTE-like behaviours. These behaviours are known to be hippocampally dependent (Hu & Amsel 1995), related to hippocampal activity as measured by c-fos (Hu et al. 2006) and necessary for proper decision making (Meunzinger 1938; Tolman 1939). The single sweeps observed by Johnson and Redish generally occurred during a single theta cycle and reply positions at a velocity approximately 4–15 times faster than during the actual traversal of these paths. These sweeps are thus exactly what one would predict if the animal had to rapidly recall its experience down the two arms of the maze in order to make the correct decision about which way to turn.

Additional evidence for a behavioural function of sweeps is provided by the experiments of Lenck-Santini et al. (2008), who examined hippocampal activity in the moments before the rat jumped out of the chamber to avoid a predictable shock. In such internally timed tasks, there is a strong build-up of theta activity before the animal acts (Vanderwolf 1971; O'Keefe & Nadel 1978; Terrazas et al. 1997). If this build-up of theta was disrupted, the animal often did not act. It is during this build-up that the phase precession occurred. Lenck-Santini et al. found that a well-trained rat injected with the cholinergic antagonist scopolamine sometimes failed to jump to avoid the shock. There was a strong correlation between these instances and the failure to see the build-up of theta power before the jump. Interruption of theta (and the concomitant phase precession) may have interfered with the planning of the jump.

8. Possible mechanisms of phase precession

There is now substantial evidence that sweeps (and phase precession) can be viewed as a predictive process, but the underlying mechanisms are less certain. Several models have been proposed. One class of models is the dual-oscillator model (O'Keefe & Recce 1993; Burgess et al. 2007; Hasselmo et al. 2007); we refer readers to an excellent critique of such models (Mauer & McNaughton 2007). Here, we focus on cued-chaining models.

In cued-chaining (Jensen & Lisman 1996; Tsodyks et al. 1996; Maurer & McNaughton 2007), asymmetric weights exist between the cells representing subsequent positions along the track (e.g. the synapses of A cells onto B cells, the synapses of B cells onto C cells). Thus, if after the asymmetric weights are formed, the animal subsequently comes to A, the A cells can retrieve the B–G sequence by a simple excitatory chaining process that uses these asymmetric weights. This sequence will occur during a theta cycle, thereby producing a sweep. Importantly, the processes postulated are not linked to the spatial aspects of place cells and so can be generalized to all forms of memory.

The proposition that the asymmetric weights thought to underlie the phase are learned through experience makes a strong prediction: phase precession should not occur on the first pass through a novel environment. Experimental tests of this prediction have given a somewhat mixed answer. Rosenzweig et al. (2000) reported that cells could show phase precession even on the first lap on a novel track, but this study did not attempt to quantify phase precession. In the most systematic study to date, Cheng & Frank (2008) reported that phase precession is weak on first exposure to a novel track, but rapidly becomes stronger with further experience. These results suggest that there are both learning-dependent and -independent components of the phase precession. One possibility is that the learning-independent component could be due to intrinsic single-cell biophysics (Kamondi et al. 1998; Magee 2001; Harris et al. 2002) either in the hippocampus (O'Keefe & Recce 1993) or in the entorhinal cortex (Burgess et al. 2007; Hasselmo et al. 2007) and may be related to non-predictive components (such as would occur in the dual-oscillator model; Maurer & McNaughton 2007).

Another potential mechanism of the learning-independent components of phase precession is to hypothesize that there are pre-wired directionally dependent asymmetric weights within the system (Samsonovich & McNaughton 1997). However, the connection matrix needed to implement a directionally dependent weight matrix in hippocampal place cells is very complicated owing to the remapping properties seen therein (Redish & Touretzky 1997; Maurer & McNaughton 2007). Because entorhinal cells do not remap between environments (Quirk et al. 1992; Fyhn et al. 2007), a pre-wired map could exist in the entorhinal cortex (Redish & Touretzky 1997; Redish 1999) encoded by the grid cells therein (Hafting et al. 2005). The existence of directional information within the entorhinal cortex (Hafting et al. 2008), in conjunction with a pre-existing map, could allow prediction of future locations without the animal having ever experienced the path between these locations.

The above considerations suggest that there is both a learning-dependent and a learning-independent component of the phase precession and that there are plausible mechanisms that could underlie these components. Thus, the general idea that the phase procession occurs by a chaining process that uses thase mechanisms seems plausible. However, there is an objection to this class of models that was emphasised in a recent review (Maurer & McNaughton 2007) which we will now discuss. In many environments place fields have omnidirectional fields. In these environments, place fields have omnidirectional fields. In these environments, the learning processes that drive synaptic learning should produce symmetric weights (Muller et al. 1991; Redish & Touretzky 1998). Symmetric weights should lead to excitation of both A and C when an animal is at the intermediate location B, contrary to the data showing that phase precession and sweeps produce unidirectional sequences (i.e. the sequence is either ABCD or DCBA depending on which way the rat is moving). One potential resolution to this problem would be to assume that there is a small directional component that causes cells to fire in one direction but not the other. Directionally dependent inhibitory interneurons have been found in the hippocampus (Leutgeb et al. 2000), which could selectively inhibit activity behind the animal. Alternatively, visual cues coming from the lateral entorhinal cortex (Hargreaves et al. 2005; Leutgeb et al. 2008), which would depend on which direction the rat is headed, may change the firing rates sufficiently to break the symmetry.

9. Simple retrieval or construction?

We have reviewed the evidence that the process of sequence recall can be observed in the hippocampus and that several variants can now be studied in detail. As we have argued, simple recall of sequences can be viewed as a form of prediction. To the extent that the world is governed by fixed sequences, cued sequence recall is a prediction of what will happen next. However, recall may not simply be a replay of past sequences. As noted at the beginning of this review, tasks that depend on hippocampal integrity tend to be those tasks that require integration of separate components, while simple sequence recall tends to be hippocampally independent. For example, the hippocampus is not involved in the generation of simple expectancies, as used in typical instrumental learning tasks (Corbit & Balleine 2000), but it is involved in accommodating complex changes in contingencies (as in contingency degradation tasks; Corbit et al. 2002). This ability to deal with complexity might allow the hippocampus to combine information to produce a prediction of events that never happened. From a cognitive perspective, it seems clear that both simple recall of memories and constructive processes take place. What is much less clear is where these processes take place and the particular role of the hippocampus. Perhaps the hippocampus is best described as a simple memory device: the predictive processes that occur during cued recall are a relatively faithful replay of the original events and these events are then integrated by other brain regions to construct predictions. Alternatively, the hippocampus may itself integrate information to form constructions. A recent study of patients with hippocampal damage (Hassabis et al. 2007) suggests that the role of the hippocampus is in the integration of separate components rather than the simple retrieval of memories. At this point, the electrophysiological evidence only provides support for retrieval. Whether the hippocampus can also construct never-experienced predictions is still an open question.

10. Time scales

An important limitation of the predictive process described thus far is that is it deals with a rather small temporal and spatial scale. The phase precession and sweeps discussed above are predictions about locations less than a metre from the current position and that the rat will typically come to in several seconds. Human cognitive abilities depend on the ability to predict much further in the future. Whether rats have this ability is controversial (Roberts et al. 2008).

Several mechanisms could potentially provide prediction further in the future. The experiments described in this paper were all carried out in the dorsal hippocampus, but cells in the ventral entorhinal cortex and hippocampus have much larger fields (Jung et al. 1994; Kjelstrup et al. 2008). Sweeps in these more ventral aspects could thus proceed much further in the future than those in dorsal aspects (Maurer & McNaughton 2007). Another possibility relates to the temporal scale of the hippocampal inputs through chunking (Miller 1956; Newell 1990) or the action of a working memory buffer (Jensen & Lisman 2005). It is possible that the information in each successive gamma cycle (figure 1) could represent events separated by large times. A final possibility is simply that the information at the end of a sweep could be looped back to provide the cue for another sweep, thereby extending the range of temporal associations.

11. Conclusion

The ability to electrophysiologically monitor ensembles in the hippocampus provides a way of addressing many of the open issues raised in this review. It should now be possible to study the time scales of prediction, analyse the mechanisms involved and determine the degree to which the process can be viewed as simple retrieval as opposed to construction. These questions will not only be important in their own right, but also provide a starting point for understanding how other brain regions interact with the hippocampus, e.g. by providing cues that stimulate hippocampal prediction or by using the hippocampal output to guide behaviour.

Acknowledgements

We thank Adam Johnson, Ed Richard and Matthijs Van der Meer for their helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. A.D.R. was supported by MH080318. J.L. was supported by R01 NS027337 and P50 MH060450.

Footnotes

One contribution of 18 to a Theme Issue ‘Predictions in the brain: using our past to prepare for the future’.

References

- Battaglia F.P., Sutherland G.R., McNaughton B.L. Local sensory cues and place cell directionality: additional evidence of prospective coding in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:4541–4550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4896-03.2004. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4896-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum K.I., Abbott L.F. A model of spatial map formation in the hippocampus of the rat. Neural Comput. 1996;8:85–93. doi: 10.1162/neco.1996.8.1.85. doi:10.1162/neco.1996.8.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bragin A., Jando G., Nadasdy Z., Hetke J., Wise K., Buzsáki G. Gamma (40–100 Hz) oscillation in the hippocampus of the behaving rat. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:47–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00047.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E.N., Frank L.M., Tang D., Quirk M.C., Wilson M.A. A statistical paradigm for neural spike train decoding applied to position prediction from ensemble firing patterns of rat hippocampal place cells. J. Neurosci. 1998;18:7411–7425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-18-07411.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess N., Barry C., O'Keefe J. An oscillatory interference model of grid cell firing. Hippocampus. 2007;17:801–812. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20327. doi:10.1002/hipo.20327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G. Large-scale recording of neuronal ensembles. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nn1233. doi:10.1038/nn1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2006. Rhythms of the brain. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Frank L.M. New experiences enhance coordinated neural activity in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2008;57:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.035. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen N.J., Eichenbaum H. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1993. Memory, amnesia, and the hippocampal system. [Google Scholar]

- Corbit L.H., Balleine B.W. The role of the hippocampus in instrumental conditioning. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:4233–4239. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04233.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit L.H., Ostlund S.B., Balleine B.W. Sensitivity to instrumental contingency degradation is mediated by the entorhinal cortex and its efferents via the dorsal hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10976–10984. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10976.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czurkó A., Hirase H., Csicsvari J., Buzsáki G. Sustained activation of hippocampal pyramidal cells by ‘space clamping’ in a running wheel. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:344–352. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00446.x. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00446.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragoi G., Buzsáki G. Temporal encoding of place sequences by hippocampal cell assemblies. Neuron. 2006;50:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.023. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudchenko P.A., Wood E.R., Eichenbaum H. Neurotoxic hippocampal lesions have no effect on odor span and little effect on odor recognition memory but produce significant impairments on spatial span, recognition, and alternation. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:2964–2977. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02964.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusek J.A., Eichenbaum H. The hippocampus and transverse patterning guided by olfactory cues. Behav. Neurosci. 1998;112:762–771. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.112.4.762. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.112.4.762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrom A.D., Meltzer J., McNaughton B.L., Barnes C.A. NMDA receptor antagonism blocks experience-dependent expansion of hippocampal “place fields”. Neuron. 2001;31:631–638. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00401-9. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00401-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin N.J., Agster K.L., Eichenbaum H.B. Critical role of the hippocampus in memory for sequences of events. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nn834. doi:10.1038/nn834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn M., Treves A., Moser M.-B., Moser E.I. Hippocampal remapping and grid realignment in entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2007;446:190–194. doi: 10.1038/nature05601. doi:10.1038/nature05601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler C., Robbe D., Zugaro M., Sirota A., Buzsáki G. Hippocampal place cell assemblies are speed-controlled oscillators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8149–8154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610121104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610121104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray J., McNaughton N. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2000. The neuropsychology of anxiety. [Google Scholar]

- Hafting T., Fyhn M., Molden S., Moser M.-B., Moser E. Microstructure of a spatial map in the entorhinal cortex. Nature. 2005;436:801–806. doi: 10.1038/nature03721. doi:10.1038/nature03721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafting T., Fyhn M., Bonnevie T., Moser M.-B., Moser E.I. Hippocampus-independent phase precession in entorhinal grid cells. Nature. 2008;453:1248–1252. doi: 10.1038/nature06957. doi:10.1038/nature06957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves E.L., Rao G., Lee I., Knierim J.J. Major dissociation between medial and lateral entorhinal input to dorsal hippocampus. Science. 2005;308:1792–1794. doi: 10.1126/science.1110449. doi:10.1126/science.1110449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris K.D., Henze D.A., Hirase H., Leinekugel X., Dragol G., Czurkó A., Buzsáki G. Spike train dynamics predicts theta-related phase precession in hippocampal pyramidal cells. Nature. 2002;417:738–741. doi: 10.1038/nature00808. doi:10.1038/nature00808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassabis D., Kumaran D., Vann S.D., Maguire E.A. Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1726–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610561104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0610561104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselmo M.E., Giocomo L.M., Zilli E.A. Grid cell firing may arise from interference of theta frequency membrane potential oscillations in single neurons. Hippocampus. 2007;17:1252–1271. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20374. doi:10.1002/hipo.20374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirase H., Czurkó A., Csicsvari J., Buzsáki G. Firing rate and theta-phase coding by hippocampal pyramidal neurons during ‘space clamping’. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11:4373–4380. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00853.x. doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00853.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Amsel A. A simple test of the vicarious trial-and-error hypothesis of hippocampal function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:5506–5509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5506. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.12.5506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Xu X., Gonzalez-Lima F. Vicarious trial-and-error behavior and hippocampal cytochrome oxidase activity during Y-maze discrimination learning in the rat. Int. J. Neurosci. 2006;116:265–280. doi: 10.1080/00207450500403108. doi:10.1080/00207450500403108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxter J.R., Senior T.J., Allen K., Csicsvari J. Theta phase-specific codes for two-dimensional position, trajectory and heading in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 2008;11:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nn.2106. doi:10.1038/nn.2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J.C., Johnson A., Redish A.D. Hippocampal sharp waves and reactivation during awake states depend on repeated sequential experience. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:12 415–12 426. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4118-06.2006. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4118-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O., Lisman J.E. Hippocampal CA3 region predicts memory sequences: accounting for the phase precession of place cells. Learn. Mem. 1996;3:279–287. doi: 10.1101/lm.3.2-3.279. doi:10.1101/lm.3.2-3.279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O., Lisman J.E. Position reconstruction from an ensemble of hippocampal place cells: contribution of theta phase encoding. J. Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2602–2609. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen O., Lisman J.E. Hippocampal sequence-encoding driven by a cortical multi-item working memory buffer. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.001. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Redish A.D. Neural ensembles in CA3 transiently encode paths forward of the animal at a decision point. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:12 176–12 189. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3761-07.2007. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3761-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Jackson J., Redish A.D. Measuring distributed properties of neural representations beyond the decoding of local variables: implications for cognition. In: Hölscher C., Munk M.H.J., editors. Mechanisms of information processing in the brain: encoding of information in neural populations and networks. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2008. pp. 95–119. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Fenton A.A., Kentros C., Redish A.D. Looking for cognition in the structure within the noise. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009;13:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.005. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung M.W., Wiener S.I., McNaughton B.L. Comparison of spatial firing characteristics of the dorsal and ventral hippocampus of the rat. J. Neurosci. 1994;14:7347–7356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07347.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamondi A., Acsády L., Wang X.-J., Buzsáki G. Theta oscillations in somata and dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal cells in vivo: activity-dependent phase-precession of action potentials. Hippocampus. 1998;8:244–261. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:3<244::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-J. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1998)8:3<244::AID-HIPO7>3.0.CO;2-J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjelstrup K.B., Solstad T., Brun V.H., Hafting T., Leutgeb S., Witter M.P., Moser E.I., Moser M.-B. Finite scale of spatial representation in the hippocampus. Science. 2008;321:140–143. doi: 10.1126/science.1157086. doi:10.1126/science.1157086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenck-Santini P.-P., Fenton A.A., Muller R.U. Discharge properties of hippocampal neurons during performance of a jump avoidance task. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6773–6786. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5329-07.2008. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5329-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb S., Ragozzino K.E., Mizmori S.J. Convergence of head direction and place information in the CA1 region of hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2000;100:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00258-x. doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00258-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leutgeb J.K., Henriksen E.J., Leutgeb S., Witter M.P., Moser M.-B., Moser E.I. Hippocampal rate coding depends on input from the lateral entorhinal cortex. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 2008;315:961–966. doi: 10.1038/nn.3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy W.B. A sequence predicting CA3 is a flexible associator that learns and uses context to solve hippocampal-like tasks. Hippocampus. 1996;6:579–591. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<579::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-C. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:6<579::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy W.B., Sanyal A., Rodriguez P., Sullivan D.W., Wu X.B. The formation of neural codes in the hippocampus: trace conditioning as a prototypical paradigm for studying the random recoding hypothesis. Biol. Cybern. 2005;92:409–426. doi: 10.1007/s00422-005-0568-9. doi:10.1007/s00422-005-0568-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L., Osan R., Shoham S., Jin W., Zuo W., Tsien J.Z. Identification of network-level coding units for real-time representation of episodic experiences in the hippocampus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:6125–6130. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408233102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408233102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J. The theta/gamma discrete phase code occurring during the hippocampal phase precession may be a more general brain coding scheme. Hippocampus. 2005;15:913–922. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20121. doi:10.1002/hipo.20121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman J., Idiart M.A. Storage of 7+/−2 short-term memories in oscillatory sub-cycles. Science. 1995;267:1512–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.7878473. doi:10.1126/science.7878473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee J.C. Dendritic mechanisms of phase precession in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;86:528–532. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manns J.R., Howard M.W., Eichenbaum H. Gradual changes in hippocampal activity support remembering the order of events. Neuron. 2007;56:530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.017. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer A.P., McNaughton B.L. Network and intrinsic cellular mechanisms underlying theta phase precession of hippocampal neurons. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.002. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta M.R., Barnes C.A., McNaughton B.L. Experience-dependent, asymmetric expansion of hippocampal place fields. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:8918–8921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.16.8918. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.16.8918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunzinger K.F. Vicarious trial and error at a point of choice. I. A general survey of its relation to learning efficiency. J. Genet. Psychol. 1938;53:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Miller G. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol. Rev. 1956;63:81–97. doi:10.1037/h0043158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller R.U., Kubie J.L., Saypoff R. The hippocampus as a cognitive graph. Hippocampus. 1991;1:243–246. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450010306. doi:10.1002/hipo.450010306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell A. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1990. Unified theories of cognition. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J., Nadel L. Clarendon Press; Oxford, UK: 1978. The hippocampus as a cognitive map. [Google Scholar]

- O'Keefe J., Recce M. Phase relationship between hippocampal place units and the EEG theta rhythm. Hippocampus. 1993;3:317–330. doi: 10.1002/hipo.450030307. doi:10.1002/hipo.450030307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastalkova E., Itskov V., Amarasingham A., Buzsáki G. Internally generated cell assembly sequences in the rat hippocampus. Science. 2008;321:1322–1327. doi: 10.1126/science.1159775. doi:10.1126/science.1159775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quirk G.J., Muller R.U., Kubie J.L., Ranck J.B., Jr The positional firing properties of medial entorhinal neurons: description and comparison with hippocampal place cells. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:1945–1963. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01945.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish A.D. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1999. Beyond the cognitive map: from place cells to episodic memory. [Google Scholar]

- Redish A.D., Touretzky D.S. Cognitive maps beyond the hippocampus. Hippocampus. 1997;7:15–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:1<15::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1997)7:1<15::AID-HIPO3>3.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redish A.D., Touretzky D.S. The role of the hippocampus in solving the Morris water maze. Neural Comput. 1998;10:73–111. doi: 10.1162/089976698300017908. doi:10.1162/089976698300017908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W.A., Feeney M.C., Macpherson K., Petter M., McMillan N., Musolino E. Episodic-like memory in rats: is it based on when or how long ago? Science. 2008;320:113–115. doi: 10.1126/science.1152709. doi:10.1126/science.1152709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig E.S., Ekstrom A.D., Redish A.D., McNaughton B.L., Barnes C.A. Phase precession as an experience-independent process: hippocampal pyramidal cell phase precession in a novel environment and under NMDA-receptor blockade. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 2000;26:982. [Google Scholar]

- Samsonovich A.V., McNaughton B.L. Path integration and cognitive mapping in a continuous attractor neural network model. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:5900–5920. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05900.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior T.J., Huxter J.R., Allen K., O'Neill J., Csicsvari J. Gamma oscillatory firing reveals distinct populations of pyramidal cells in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:2274–2286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4669-07.2008. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4669-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Barnes C.A., McNaughton B.L., Skaggs W.E., Weaver K.L. The effect of aging on experience-dependent plasticity of hippocampal place cells. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:6769–6782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-17-06769.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaggs W.E., McNaughton B.L., Wilson M.A., Barnes C.A. Theta phase precession in hippocampal neuronal populations and the compression of temporal sequences. Hippocampus. 1996;6:149–173. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:2<149::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:2<149::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrazas A., Gothard K.M., Kung K.C., Barnes C.A., McNaughton B.L. All aboard! What train-driving rats can tell us about the neural mechanisms of spatial navigation. Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 1997;23:506. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman E.C. Prediction of vicarious trial and error by means of the schematic sow-bug. Psychol. Rev. 1939;46:318–336. doi:10.1037/h0057054 [Google Scholar]

- Tsodyks M.V., Skaggs W.E., Sejnowski T.J., McNaughton B.L. Population dynamics and theta rhythm phase precession of hippocampal place cell firing: a spiking neuron model. Hippocampus. 1996;6:271–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:3<271::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-Q. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1996)6:3<271::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderwolf C.H. Limbic-diencephalic mechanisms of voluntary movement. Psychol. Rev. 1971;78:83–113. doi: 10.1037/h0030672. doi:10.1037/h0030672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M.A., McNaughton B.L. Dynamics of the hippocampal ensemble code for space. Science. 1993;261:1055–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.8351520. doi:10.1126/science.8351520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Ginzburg I., McNaughton B.L., Sejnowski T.J. Interpreting neuronal population activity by reconstruction: unified framework with application to hippocampal place cells. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;79:1017–1044. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]