Abstract

This article provides a framework labeled ACT that aims to successfully integrate family caregivers and patients into one unit of care, as dictated by the hospice philosophy. ACT (assessing caregivers for team interventions) is based on the ongoing assessment of the caregiver background context, primary, secondary, and intrapsychic stressors as well as outcomes of the caregiving experience and subsequently, the design and delivery of appropriate interventions to be delivered by the hospice interdisciplinary team. Interventions have to be tailored to a caregiver’s individual needs; such a comprehensive needs assessment allows teams to customize interventions recognizing that most needs and challenges cannot be met by only one health care professional or only one discipline. The proposed model ensures a holistic approach to address the multifaceted challenges of the caregiving experience.

Keywords: hospice care, patient care team, caregivers, interdisciplinary communication

Introduction

Hospice care provides palliative and passionate care for people in the last phases of a terminal disease and their families, so that they may live with dignity and as fully and comfortably as possible. The number of individuals and their families receiving hospice services has grown by 162% during the past 10 years, establishing hospice care as the preferred service for terminally ill individuals in the United States.1 The philosophy of hospice care is based on the underlying principles of holistic care (the patient and their family are the unit of care2) and self-determination (it is the patient and family’s beliefs, values, culture, and lifestyle that govern decisions pertaining to care3). This framework highlights that family caregivers are essential to the delivery of hospice services. A family caregiver is a relative, friend, or other individual who is the primary caregiver of the hospice patient at home. In addition to the physical tasks associated with caregiving and the emotional support, family caregivers are often proxies for clinical decision making, given the deteriorating condition of terminal patients.4

As hospice grows, we need to address identified barriers and needs such as family caregivers’ need for emotional support and meaningful communication with hospice providers.5–7 Social and emotional support has been found to be critical in helping family caregivers cope with caring for the dying patient.8,9 Whereas clinicians tend to focus on the physical aspects of care, family caregivers and their patients experience end of life with a broader psychosocial and spiritual perception shaped by a lifetime of experiences.10 As Steinhauser et al argue, quality care at the end of life is highly individual and should be achieved through a process of clear communication and shared decision making that acknowledges the values and preferences of patients and their family caregivers.10

Caregivers often feel that there is little attention paid to their views and perceptions, which challenges their hospice experience.11 Hospice providers may fail to fully address caregivers’ own emotional, spiritual, and clinical needs as well as other characteristics that may affect their caregiving tasks. An example how caregivers’ views and fears may affect the delivery of hospice services is pain management where caregivers’ fears, beliefs, lack of assessment skills, burden, and strain are found to be barriers to family caregivers’ ability to adequately manage their loved one’s pain.12–15 In a study of caregiver perceptions of pain management and subsequent analysis of hospice team meetings, Oliver et al found that while caregivers have significant concerns and fears pertaining to pain management that can potentially affect adherence to medication regimens, the hospice teams are not addressing or even mentioning these concerns.16

Furthermore, while hospice care is based on the notion of interdisciplinary provider collaboration and federal regulations mandate hospices to hold interdisciplinary team (IDT) meetings consisting of several hospice providers (eg, medical director, nurse, social worker, and so on)17, patients and their family caregivers are currently absent from these discussions.18 As a result, some IDT members who make decisions about the care plan, may not have met the family caregiver or be unaware of their burden, fears, or preferences.

The notion that the patient and the family caregiver consist together the unit of care is intrinsically nested in the hospice philosophy. This however has not translated into specific guidelines for the inclusion of family caregivers in the decision making process or for the assessment of caregivers’ needs and preferences. Although scientific literature includes individual interventions that have been designed to address caregivers’ coping needs (eg, a coping skills intervention delivered by nurses to caregivers of cancer patients in 3 face-to-face visits,19 support phone calls made by nurses to caregivers of patients with cancer20), these initiatives are based on family caregivers’ interactions with one hospice provider only (usually the hospice nurse) and address one aspect of the caregiving experience in silo (eg, stress or coping skills). However, there is a lack of interventions that are based on an interdisciplinary holistic view of hospice and include caregivers in the ongoing decision making process of hospice services.

In the following, we describe a proposed framework for the inclusion of family caregivers in the core of hospice services and their assessment by hospice teams, which ultimately leads to customized interventions to improve the quality of hospice care and address any barriers that may challenge the integration of caregiver and patient into one unit of care. Furthermore, we highlight the benefits of the proposed framework and the practical implications for its implementation in the hospice setting.

Assessing Caregivers for Team Interventions and the Caregiving Experience

Although family caregivers are essential to the delivery of hospice services, this experience affects their own morbidity and quality of life. The impact of the anxiety resulting from the caregiving experience on the health and well being of caregivers has been described,21 and there is a growing literature on the consequences in terms of the physical and mental health of the family caregiver.22 Anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem, feelings of isolation as well as fatigue and somatic health problems have all been identified as typical symptoms for a primary caregiver of a dying relative at home.23 Kinsella and colleagues23 categorized caregiver burden into an objective form, represented by tangible costs, physical care demands, and disruptions to daily routines, and a subjective form represented by the caregiver’s appraisal of the impact of caring, the emotions aroused by caregiving, and the coping resources. In this context, Kinsella et al23 identified factors that affect the caregiving experience: personality, stressor appraisal, use of coping strategies, the availability and adequacy of social support, family functioning, and competing commitments.

The degree of anxiety occurring as a consequence of caregiving is counterbalanced by some degree of positive gains from the experience along with the degree of support and information gained from the hospice staff.24 In situations where the stress outweighs personal resources and external coping, general health and well-being deteriorates, social participation is inhibited and there are inevitable psychological complications.23,25 Due to this stress response, the use of an anxiety appraisal and coping model helps to understand the process of any intervention aimed at reducing anxiety through the provision of support and information. The most comprehensive model of stress and coping indicating the mediating factors in the process of caregiving was developed by Pearlin et al,26 which was further developed and modified by Meyers and Gray.27

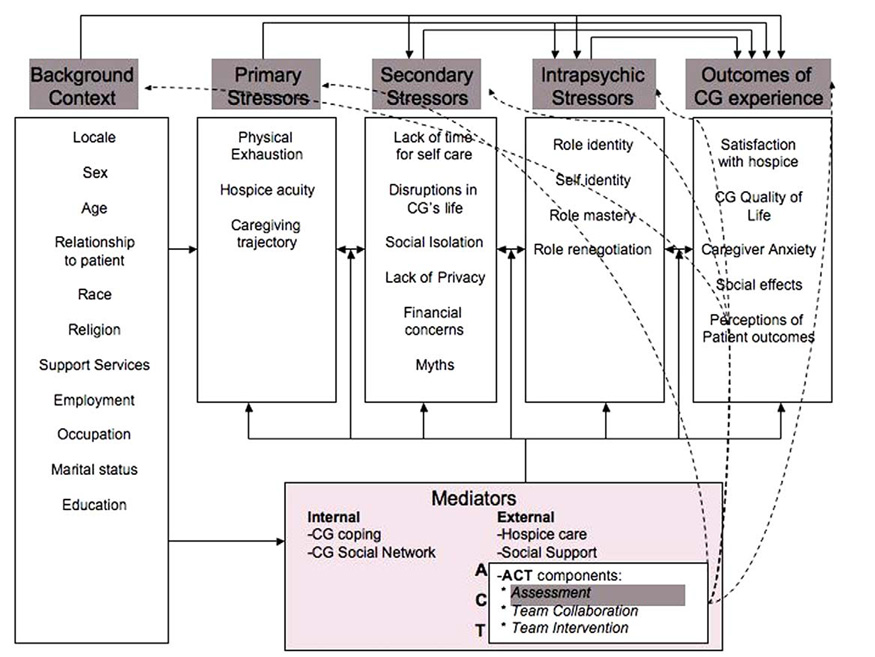

We are proposing an approach labeled Assessing Caregivers for Team Interventions (ACT) that is based on the ongoing assessment of the background context, primary, secondary, and intrapsychic stressors as well as outcomes of the caregiving experience and subsequently, the design and delivery of appropriate interventions to be delivered by the hospice team (ensuring a holistic approach to addressing the multifaceted challenges of the caregiving experience). Assessing caregivers for team interventions can therefore act as one of the mediators that can affect the overall caregiver experience and improve outcomes such as satisfaction with hospice care, reduce anxiety, and improve overall quality of care (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The ACT model as a mediator within the caregiving experience (based on a redesign and expansion of the original framework by Pearlin et al26 and its modified version by Meyers and Gra27). ACT = assessing caregivers for team interventions; CG = caregiving/caregiver.

Assessing caregivers’ background, primary, secondary, and intrapsychic stressors and tailoring a team intervention enable hospice providers to not only gain insight into the caregiving experience but to also address any stressors and provide the tools that can mediate stress responses with appropriate support and information. The background context should already be part of the patient’s chart. The assessment of primary, secondary, intrapsychic stressors, and outcomes can rely on standardized instruments as well as interactions and observations by hospice providers. The hospice team can then review findings during the IDT meetings and determine a plan of action based on identified needs and challenges and areas of expertise of the participating members.

To increase the efficiency of ACT as a model of inclusive and holistic care, it is appropriate for 1 member of the hospice team to act as the caregiver advocate who summarizes the findings of the ongoing assessment and highlights areas that need to be addressed by the team. This member can also ensure that caregivers are informed and have access to appropriate resources, and as a caregiver advocate explore ways to increase communication between the family caregiver and the IDT team and solicit caregiver’s feedback in the decision making process. Assessing caregivers for team interventions is a tool to enable the implementation of the overall theoretical premise of hospice care that dictates treating patients and their family caregiver as one unit.

Delivering Team Interventions

The IDT interventions based on the caregiver assessment can be aiming to reduce the actual caregiving tasks and/or provide support and enhance caregivers’ coping skills and education. Such empowering interventions designed by the hospice team can draw from the theoretical framework of the prepared family caregiver model,28 which indicates that training caregivers to effectively manage problems will empower them and moderate caregiving stress. The unique problem solving framework builds on the original work of Nezu et al and D’Zurilla et al, which integrated a problem solving approach with cognitive behavioral strategies.29,30 The framework advocates 2 determining processes of problem management namely, problem orientation and problem solving.31 Problem orientation represents the motivational component of the overall problem-solving process. Actual problem solving involves 4 identified skills: (1) problem definition and formulation, which involves gathering data and information, articulating the issue in clear terms, identifying the challenge, and setting realistic goals; (2) generation of alternative coping strategies; (3) decision making; and (4) solution implementation.29 The assessment of caregivers’ primary, secondary, and intrapsychic stressors as well as outcomes of the hospice process can guide the problem definition and formulation and the assignment of responsibilities among team members to ensure that different members assist with different problems or dimensions of a challenging situation but at the same time enable awareness of caregiver issues and coordination of tasks and services among all team members.

Educational interventions can target possible fears, myths, or misperceptions highlighted by the caregiver assessment. For example, Oliver et al found, when administering the Caregiver Pain Medicine Questionnaire to hospice caregivers, that the overwhelming majority expressed agreement with at least one statement on that instrument that indicates some reservations or misinformation regarding pain management or medication administration.16 In a study of hospice patient and caregiver congruence in reporting patients’ symptom intensity, McMillan and Moody15 found that family caregivers could not reliably assess patient symptom intensity and expressed in some cases little or no understanding of patient symptoms and symptom etiology. The assessment of caregivers’ stressors as part of the ACT intervention would highlight such challenges and allow the hospice team to deliver an intervention to educate caregivers on the myths of pain management, an explanation of patient symptoms, and ways to systematically assess them, in an effort to ease caregiver anxiety and fear, promote adherence to medication regimens, and overall improve pain management.

Practical Implications of ACT

Implementing ACT in the hospice setting involves several practical implications. Hospice agencies struggle to provide adequate or frequent support to caregivers as they are faced with a series of challenges. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has identified obstacles in end-of-life care32 such as problematic or infrequent communication between all involved parties and limited resources. While caregivers rate communication as essential to the support they receive and seek regular contact with hospice providers,33 it is in many cases not practical for them to attend hospice IDT meetings due to geographic constraints, lack of time, and concerns leaving a frail loved one alone. Furthermore, hospice agencies may not be able to easily increase the number of visits to the patient’s home to improve communication with patients and caregivers. Assessment of and communication with caregivers and their participation in hospice team meetings can be in many cases facilitated with the use of technology. For example, the Internet can be used to enable caregivers to access educational material or virtual support groups and to respond to ongoing surveys assessing stressors and outcomes. Furthermore, the use of regular phones, videophones, or other videoconferencing applications can be used to allow caregiver involvement in the team meetings, if so desired or required by the proposed team intervention. In previous work we recognized the potential of telehealth technologies such as videoconferencing solutions, Web applications, message boards, and online support groups for hospice caregivers.34 Similar tools can be used to enhance communication between caregivers and IDT members as part of ACT.

The implementation of ACT also requires education of the hospice staff to provide them with the skills to interpret the caregiver assessment findings and design and deliver the appropriate intervention. Training should address not only how IDT members communicate with caregivers but also with each other regarding roles and assignments to maximize the potential of interdisciplinary work.

Finally, an infrastructure needs to be in place to facilitate information exchange among team members and caregivers. A study of IDT meetings revealed challenges in the information flow during these meetings (for example, retelling of facts, lack of access to patient charts, documentation gaps, challenges in updating records).35 The efficiency of team meetings and ultimately the delivery of team interventions within ACT can be increased if a leader or facilitator and a caregiver advocate are defined. The facilitator can plan the structure and procedures of the meetings while the caregiver advocate summarizes the findings of the caregiver assessment and enables the team to recognize specific needs and areas for improvement.

ACT requires structured documentation. Documentation needs to become a priority for both the facilitator and the responsibility for the caregiver advocate before the meeting begins. In addition to specific tools that can facilitate the implementation of ACT, there are structural characteristics pertaining to the organizational nature of a hospice agency that can contribute to maximizing the efficiency of team interventions. These include manageable caseloads, an organizational culture that supports interdisciplinary collaboration and administrative support.36 Finally, the success of ACT will depend on the agency’s commitment to practically and efficiently implement the core principle hospice, namely treating patients and family caregivers as one unit of care.

Discussion

Assessing caregivers for team interventions promotes an evidence-based approach to hospice care planning. The variables that are included in the set of background context, primary, secondary, and intrapsychic stressors have been found to affect the overall caregiving experience and ultimately the outcomes of hospice care. The focus on both process variables and outcomes allows for continuous quality improvement and integration of evidence-based guidelines. Assessing caregivers for team interventions is also a translational tool as it is based on the practical implementation of a theoretical framework of the caregiving experience and translation of extensive research on stressors into concrete guidelines for the delivery of holistic hospice services.

Assessing caregivers for team interventions recognizes that the “provision of information is the primary intervention in palliative care.”37 When caregivers voice questions or concerns and perceive that these are adequately addressed, their satisfaction and quality of life are improved and fewer depressive symptoms are reported.38 Interventions have to be tailored to a caregiver’s individual needs and such a needs assessment must be a comprehensive evaluation of the individual caregiver’s psychosocial and physical profile and background. The identified needs in most cases cannot be met by only 1 health care professional or only 1 discipline37 but will need to be discussed and addressed by a multidisciplinary team.

Finally, ACT supports a bidirectional information flow between the hospice team members and the caregivers. Saltz and Schaefer39 suggest that certain process elements of team functioning can be influenced by caregiver involvement, especially assessment, care planning, and implementation of plans. Lack of caregiver input into problem solving or decision making, however, negatively affects care plans due to incorrect assumptions about the patient/family perspectives that influence the process.39 Assessing caregivers for team interventions provides a platform for caregivers to have a voice in the decision making process but also to receive feedback and guidance from the hospice team.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part by the National Cancer Institute Grant Nr. R21 CA120179 (Patient and Family Participation in Hospice Interdisciplinary Teams, Parker Oliver, PI) and the National Institute of Nursing Research Grant Nr. R21 NR010744-01 (A Technology Enhanced Nursing Intervention for Hospice Caregivers, Demiris PI).

References

- 1.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. NHPCO Facts and Figures: Hospice Care in America. [electronic version]. Available at: www.nhpco.org. Retrieved May 2008.

- 2.Jaffe C, Ehrlich C. All Kinds of Love: Experiencing Hospice. Amityville, NY: Baywood Publishing Co; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egan KA. A Patient-Family Value Based End of Life Care Model. Largo, FL: Hospice Institute of the Florida Suncoast; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapo J, Casarett D. Working to improve palliative care trials. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:395–397. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermann C, Looney S. The effectiveness of symptom management in hospice patients during the last seven days of life. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2001;3:88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kutner JS, Kassner CT, Nowels DE. Symptom burden at the end of life: hospice providers’ perceptions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:473–480. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291:88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele RG, Fitch MI. Coping strategies of family caregivers of home hospice patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinson SV, Brunk Q. Hospice family caregivers: an experience in coping. Hosp J. 2000;15:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinhauser SE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steele RG, Fitch MI. Coping strategies of family caregivers of home hospice patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1996;23:955–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry PE, Ward SE. Barriers to pain management in hospice: a study of family caregivers. Hosp J. 1995;10:19–33. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1995.11882805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Porter LS, et al. The self-efficacy of family caregivers for helping cancer patients manage pain at end-of-life. Pain. 2003;103:157–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Letizia M, Creech S, Norton E, Shanahan M, Hedges L. Barriers to caregiver administration of pain medication in hospice care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McMillan SC, Moody LE. Hospice patient and caregiver congruence in reporting patients’ symptom intensity. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:113–118. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200304000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker Oliver D, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Demiris G, Washington K, Porock D, Day M. Barriers to pain management: caregiver perceptions and pain talk by hospice interdisciplinary teams. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Health Care Financing Administration. Medicare Program Hospice Care: Final Rule (A.M.P.H.C.F.R.), Agency for Health Policy Research. Fed Regist. 1983;48:50008–50036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker Oliver D, Porock D, Demiris G, Courtney KL. Patient and Family Involvement in Hospice Interdisciplinary Teams: a brief study. J Palliat Care. 2005;21:270–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, Schonwetter R, Tittle M, Moody L, Haley WE. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2006;106:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh SM, Schmidt LA. Telephone support for caregivers of patients with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:448–453. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200312000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harding R, Higginson IJ. What is the best way to help caregivers in cancer and palliative care? A systematic literature review of interventions and their effectiveness. Palliat Med. 2003;17:63–74. doi: 10.1191/0269216303pm667oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen S, Given BA. Fatigue affecting family caregivers of cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 1991;14:181–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kinsella G, Cooper B, Picton C, Murtagh D. A Review of measurement of caregiver and family burden in palliative care. J Palliat Care. 1998;14:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton M, Bell D, Lambert S, Fearing A. Concerns of hospice patient caregivers. ABNF J. 2002;13:140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kinsella G, Cooper B, Picton C, Murtagh D. Factors influencing outcomes for family caregivers of persons receiving palliative care: toward an integrated model. J Palliat Care. 2000;16:46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers JL, Gray LN. The relationships between family primary caregiver characteristics and satisfaction with hospice care, quality of life, and burden. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:73–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houts PS, Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Bucher JA. The prepared family caregiver: a problem-solving approach to family caregiver education. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00790-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nezu A, Nezu C, Perri M. Problem Solving Therapy for Depression: Theory, Research, and Clinical Guidelines. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nezu AM, D’Zurilla T. Social problem solving and negative affective states. In: Kendall P, Watson D, editors. Anxiety and Depression: Disctinctive and Overlapping Features. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.D’Zurilla T, Nezu A. Social problem-solving in adults. In: Kendall P, editor. Advances in Cognitive-Behavioral Research and Therapy. Vol 1. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. and the Institute of Medicine. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Payne S, Smith P, Dean S. Identifying the concerns of informal carers in palliative care. Palliat Med. 1999;13:37–44. doi: 10.1191/026921699673763725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demiris G, Parker Oliver DR, Courtney KL, Porock D. Use of technology as a support mechanism for caregivers of hospice patients. J Palliat Care. 2005;21:303–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demiris G, Washington K, Parker Oliver D, Wittenberg-Lyles E. A study of information flow in hospice interdisciplinary team meetings. J Interprof Care. 2008;22:621–629. doi: 10.1080/13561820802380027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bronstein LR. A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Soc Work. 2003;48:297–306. doi: 10.1093/sw/48.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hebert RS, Schulz R. Caregiving at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1174–1187. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuael LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:451–459. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-6-200003210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saltz CC, Schaefer T. Interdisciplinary teams in health care: integration of family caregivers. Soc Work Health Care. 1996;22:59–69. doi: 10.1300/J010v22n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]