Abstract

Motivation: In most quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping studies, phenotypes are assumed to follow normal distributions. Deviations from this assumption may affect the accuracy of QTL detection and lead to detection of spurious QTLs. To improve the robustness of QTL mapping methods, we replaced the normal distribution for residuals in multiple interacting QTL models with the normal/independent distributions that are a class of symmetric and long-tailed distributions and are able to accommodate residual outliers. Subsequently, we developed a Bayesian robust analysis strategy for dissecting genetic architecture of quantitative traits and for mapping genome-wide interacting QTLs in line crosses.

Results: Through computer simulations, we showed that our strategy had a similar power for QTL detection compared with traditional methods assuming normal-distributed traits, but had a substantially increased power for non-normal phenotypes. When this strategy was applied to a group of traits associated with physical/chemical characteristics and quality in rice, more main and epistatic QTLs were detected than traditional Bayesian model analyses under the normal assumption.

Contact: runqingyang@sjtu.edu.cn; dengh@umkc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

In experimental line crosses, most parametric methods for mapping quantitative trait locus (QTL) fall into one of three types of approaches, least-squares, maximum likelihood or Bayesian approach. A common characteristic of these methods is that they all assume normally distributed phenotypes. However, many traits do not follow normal distributions, this may arise by non-normal traits, such survival time, and others may be the result of human measurement error. This deviation from the normality assumption by phenotypes can render many QTL mapping approaches inappropriate, in senses of less accuracy and effectiveness in QTL detection (Coppieters et al., 1998), and unstable results due to outliers (Pinheiro et al., 2001).

To improve the robustness, various approaches have been developed to deal with non-normal phenotypes in QTL mapping. A simple approach is to adopt parametric methods known for their robustness. However, their robustness for non-normal phenotypes is difficult to establish (e.g. Coppieters et al., 1998; Hackett, 1997; Jansen, 1992; Rebaï, 1997). A second approach is to convert non-normal traits into approximately normal variables through mathematical transformation (Sokal and Rohlf, 1995; Yang et al., 2006). Distribution-free non-parametric methods were also developed for mapping non-normal traits for various population structures (Coppieters et al., 1998; Elsen et al., 1999; Kruglyak and Lander, 1995; Zou et al., 2003). Yet another approach is to replace the normal assumption about the data with other distributions to better fit the trait data (Diao et al., 2004; Feenstra and Skovgaard, 2004; Jansen, 1992; Symons et al., 2002).

When the data is non-normal, assuming that the distributions of random effects and of residuals of Gaussian distributions makes inferences vulnerable to the presence of outliers (Pinheiro et al., 2001). To accommodate these outliers, some symmetric and long-tailed distributions, such as the Student's-t distribution (Dempster et al., 1980; Lange et al., 1989; Rogers and Tukey, 1972), have been suggested for robust estimation. The normal/independent distributions (Andrews and Mallows, 1974; Lange and Sinsheimer, 1993) are a class of symmetric and long-tailed distributions and are used in linear regression models, within a Bayesian framework (Liu, 1996). Fernandez and Steel (1998) applied the method of inverse scaling of the probability density function on the left and on the right side of a non-normal distribution to a symmetric heavy-tailed distribution and have simultaneously captured heavy tails and skewness. Rohr and Hoeschele (2002) have incorporated the Fernandez and Steel's approach into a Bayesian QTL mapping, developing a robust Bayesian QTL mapping method, which allows for non-normal, continuous distributions of phenotypes within QTL genotypes in single QTL models.

The genetic architecture of quantitative traits includes the number and locations of QTL and their main and epistatic effects. In particular, the unknown number of QTL and possible huge epistatic effects make the dissection for genetic architecture of quantitative traits extremely complex. Fortunately, with a computationally efficient Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm, Bayesian model selection frameworks have been developed for identifying epistatic QTL for complex traits (Yi et al., 2005, 2007). However, normal distributions were assumed for these approaches. The effects of deviation from this assumption have not been fully addressed.

In this article, we developed a Bayesian robust analysis strategy for studying the genetic architecture of quantitative trait, by combining the flexibility of Bayesian approach in modeling multiple QTL and their interactions and the better phenotypic fitting of symmetric and long-tailed distributions in characterizing non-normal traits. We investigated the robustness of the proposed method by a series of simulations, and applied it to a real dataset in rice. Our method showed an improved power in mapping QTLs with non-normal phenotypes.

2 METHOD

2.1 Genetic model

For simplicity, we consider a mapping population with only two segregating genotypes, e.g., a backcross, double haploid lines (DHLs) or recombinant inbred lines (RILs). However, the method can be applied to other experimental designs, such as F2 design. The phenotypes and molecular marker data were collected on n individuals. Assuming that there are q QTLs responsible for a trait of interest, the phenotypic value yi of individual i can be then described by the following multiple interacting QTL model:

| (1) |

where μ is the population mean; αj for j=1, 2,…q is the additive effect of the j-th QTL; δjk is the epistatic effect between j-th QTL and k-th QTL for j=1, 2,…, q; k=j+1, j+2,…, q. Variable xij is a genotype indicator variable for individual i at locus j and is defined as 1 for one genotype and −1 for the other genotype, and zijk=xijxik; γ• is a binary variable for each genetic effect (additive or epistatic), indicating whether the corresponding effect is included (γ•=1) or excluded (γ•=0) from model (1). Through inferring the γ•, we shall adopt Bayesian model selection to MCMC sampling in a reduced model space; and ɛi is a random environmental error.

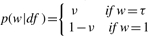

To cover outliers from non-normal distributed phenotypes, we introduce the normal/independent distributions to describe random environmental errors, denoted by  , where ei∼N(0, σ2) and wi is a positive random variable with density p(w|df.) with df being a scalar parameter. The type of normal/independent distributions depends on the distribution of w. For instance, if w is taken to be Gamma(df/2, df/2), the normal/independent distribution becomes a t-distribution; p(w|df)=dfwdf−1 results in a slash distribution (Lange and Sinsheimer, 1993; Rogers and Tukey, 1972); and the contaminated normal distribution arises when

, where ei∼N(0, σ2) and wi is a positive random variable with density p(w|df.) with df being a scalar parameter. The type of normal/independent distributions depends on the distribution of w. For instance, if w is taken to be Gamma(df/2, df/2), the normal/independent distribution becomes a t-distribution; p(w|df)=dfwdf−1 results in a slash distribution (Lange and Sinsheimer, 1993; Rogers and Tukey, 1972); and the contaminated normal distribution arises when  with 0≤v<1 and 0<τ<1, where vand τ are scalar parameters (Little, 1988). These three distributions are the most common long-tailed distributions for robust inference. Apparently, the normal model is a special case by taking wi=1, for all i.

with 0≤v<1 and 0<τ<1, where vand τ are scalar parameters (Little, 1988). These three distributions are the most common long-tailed distributions for robust inference. Apparently, the normal model is a special case by taking wi=1, for all i.

2.2 Likelihood function

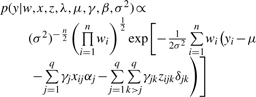

The probability distribution of the phenotype data conditional on all parameters is called the likelihood. Based on model (1), the conditional density of all phenotypes, given the parameters, is

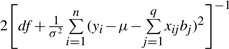

|

Where y={yi}, λ={λj},β={αj δjk}, γ={γjγjk} and w={wi}, for i=1, 2,…, n, j=1, 2,…, q and k=j+1, j+2,…, q.

2.3 Prior distribution

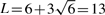

As described by Yi et al. (2005), we take L, the maximal number of QTLs as  , where l0 is the prior expected number of all QTLs including main-effect and epistatic QTLs that is determined based on traditional methods. The binary indicator γ has an independent prior p(γ)=∏p•γ•(1−p•)(1−γ•), where p•is the prior inclusion probability for a certain QTL effect and equals to a predetermined hyper-parameter pm for main effect or pe for epistatic effect.

, where l0 is the prior expected number of all QTLs including main-effect and epistatic QTLs that is determined based on traditional methods. The binary indicator γ has an independent prior p(γ)=∏p•γ•(1−p•)(1−γ•), where p•is the prior inclusion probability for a certain QTL effect and equals to a predetermined hyper-parameter pm for main effect or pe for epistatic effect.

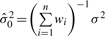

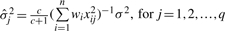

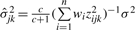

The population mean μ is assumed to have a prior p(μ)∝ constant. A hierarchical mixture model is proposed as the prior distribution for each genetic effect, denoted by αj|(γj, σ2, x•j)∼N(0, γjc(∑i=1nwixij2)−1σ2) for additive effects and δjk|(γjk, σ2, z•jk)∼N(0, γjkc(∑i=1nwizijk2)−1σ2) for the epistatic effects, where c takes a value such that the prior variance of each QTL effect stays approximately the same as n increases. Here, we let c=n.

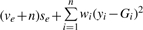

A scaled inverse-χ2 distribution with hyper-parameters ve and se will be adopted as prior for σ2, i.e.

The prior for scalar parameter df is specified based on the type of normal/independent distributions for residual error. The detailed specification of the prior is given in Appendix A.

The prior for position of the j-th QTL is p(λj)=1/dj, where dj is the length of the marker or adjoining QTLs interval where the j-th QTL resides.

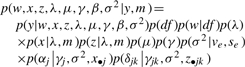

2.4 Posterior distribution and MCMC sampling

The joint posterior density of all unknown parameters is then:

|

(2) |

where m is the known marker information; forj=1, 2,…, q.

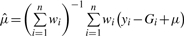

In order to implement Bayesian estimation via the MCMC, the marginal posterior distributions of all parameters need to be derived from the above joint posterior density (2) by fixing other parameters. For convenience, we first let

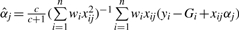

The fully conditional posterior density of the population mean μ, given all other parameters, can be shown to be a normal distribution with mean  , and variance

, and variance .

.

Conditionally on all other parameters, the QTL effects are mutually independent. In particular, the density of the fully conditional posterior distribution of αj is normal with mean  , and variance

, and variance  . Likewise, the conditional posterior distribution of δjk corresponds to the normal with mean

. Likewise, the conditional posterior distribution of δjk corresponds to the normal with mean  and variance

and variance  , for j=1, 2,…, q and k=j+1, j+2,…, q.

, for j=1, 2,…, q and k=j+1, j+2,…, q.

For the residual variance σ2, the corresponding fully conditional distribution is a scaled inverse χ2 with parameters ve+n and  .

.

So far, we note that wi can be interpreted as a ‘weight’. The specific forms of the posterior for wi depend on the normal/independent distribution adopted, and the posterior for degree of freedom df depend on the form of corresponding prior distribution (detailed in Appendix B).

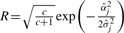

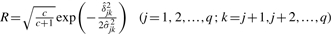

The marginal posterior distribution of γ• is Bernoulli with a probability

where, p•=pm and  for the additive effect; p•=pe and

for the additive effect; p•=pe and  for the epistatic effect. If γ• is sampled to be zero, corresponding α or δ=0. Otherwise, α or δ is drawn from its conditional posterior.

for the epistatic effect. If γ• is sampled to be zero, corresponding α or δ=0. Otherwise, α or δ is drawn from its conditional posterior.

Only the position of QTL, where corresponding γ•=1 for either main or epistatic effect, will be sampled. Since the genotype of QTL (x) depends on the QTL position (λ), we decide to sample {λj, xj} jointly as a block but proceed with the sampling wit one locus at a time. Each locus is sampled from a variable interval (Wang et al., 2005; Zhang and Xu, 2005) whose boundaries are the positions of adjoining QTLs. The prior distribution of λj can be written as

where λj−1 and λj+1 are the positions of the left and the right QTL. Let λj(t) be the current position of the locus of interest and xj(t)=[x1j … xnj]T be the genotype array of all individuals at the locus. We first sample a new position for the QTL called the proposed position and denoted by λj*=λj+δ, where δ is sampled from U(−s, s) and s is a small positive number (tuning parameter), such as 1 cM. For the new position, we simulate the genotypes for all individuals, denoted by xj*. We then use the M–H rule to decide whether λj* should be accepted or not. If λj* is accepted, we update both the position and the genotype using λj(t+1)=λj* and xj(t+1)=xj*. Otherwise, the old values of λj and xj are carried over so that λj(t+1)=λj(t) and xj(t+1)=xj(t). Detailed formula of the M–H acceptance rule can be found in (Wang et al., 2005) and Zhang and Xu (2005).

Genotypes of missing markers were generated randomly in each iteration on the basis of the probability inferred jointly from the nearest non-missing flanking markers and the phenotype. The probability from the markers is treated as the prior probability. After incorporation of the marker (QTL) effects through the phenotype, the probability becomes the posterior probability, which is used to generate the missing marker genotype. See, (Wang et al., 2005) for details.

In summary, the MCMC process is described in the following steps:

Initialize all variables with some legal values or values sampled from their prior distributions.

Update population mean μ.

Update the binary indicators γ.

Update the additive QTL effects αj corresponding that γj=1.

Update the epistatic QTL effects δ jk corresponding that γjk=1.

Update the residual variance σ2.

Update the degree of freedom df in the t-distribution or Slash distribution, or v in the contaminated normal distribution.

Update the ‘weight’ wi (i=1, 2,…, n).

Update the QTL position λj corresponding that γ•=1 and the genotypes for those QTLs.

Impute the genotypes of missing markers.

Repeat steps (2)–(10) until the Markov chain reaches a desirable length.

2.5 Post-MCMC analysis

The posterior sample can be used to infer the genetic architecture of a quantitative trait. Prior to doing this, we need to monitor the mixing behavior and convergence rates of MCMC algorithms by visually inspecting trace plots of the sample values of scalar quantities of interest or by using formal diagnostic methods provided in the package R/coda (Plummer et al., 2004). Model averaging accounts for model uncertainty and provides more robust inference compared with a single optimal model approach (Ball, 2001; Raftery et al., 1997; Sillanpää and Corander, 2002). Therefore, we employ the model averaging to assess characteristics of the genetic architecture by averaging over possible models weighted by their posterior probabilities. We can use various methods to graphically and numerically summarize and interpret the posterior samples. The posterior inclusion probability for each locus is estimated as its frequency in the posterior samples. Taking the prior probability into consideration, we use Bayes factors (BFs) to show evidence for inclusion against exclusion of each locus or effect. The BF for a locus or effect is defined as the ratio of the posterior odds to the prior odds for inclusion against exclusion of the locus or effect within each chromosomal interval of 1–2 cM (Kass and Raftery, 1995). Generally, a threshold of BF is empirically determined as 3, or 2logBF=2.1, for declaring statistical significance for each locus or effect (Kass and Raftery, 1995).

3 SIMULATION STUDIES

For convenience of programming, we simulated 61 equally spaced co-dominant markers on a single large chromosome of a length 500 cM for a backcross population with sample sizes of 150 and 300. We simulated the four QTLs, two pairs of which are assumed to mutually interact. The total genetic variance contributed by all main-effect and epistatic QTLs was 45.06, where the proportion of phenotypic variance contributed by an individual QTL ranged from 0.95% to 11.63%. The population mean and the residual variance were set at μ=5.0 and σ2=3.0.

We use non-Bayesian and Bayesian methods to analyze the simulated data. Non-Bayesian mapping is implemented with EM algorithm through two dimensional scan. Detected QTL effects are estimated using multiple QTL imputation. The critical values at significance level of 5% are 3.9 for main effect and 6.7 for epistatic effect, which are obtained with 1000 permutations.

In all Bayesian mapping analysis, we set the prior number of main-effect QTL at three and the prior expected number of epistatic QTL at three, then the upper bound of the number of QTL,  . The actual values for the hyper-parameters take ve=0 and se=1; a=1 and b=0.01. The initial values of all variables are sampled from their prior distributions. The MCMC is run for 6000 cycles as burn-in period (deleted) and then for additional 100 000 cycles after the burn-in. Note that here the length of the burn-in is judged by visually inspecting the plots of some posterior samples across rounds. The chain is then thinned to reduce serial correlation by saving one observation in every 40 cycles. The posterior sample contains 2500 observations for the post-MCMC analysis. Considering each simulation is more time consuming, the simulation experiment was replicated 50 times for statistical power evaluation.

. The actual values for the hyper-parameters take ve=0 and se=1; a=1 and b=0.01. The initial values of all variables are sampled from their prior distributions. The MCMC is run for 6000 cycles as burn-in period (deleted) and then for additional 100 000 cycles after the burn-in. Note that here the length of the burn-in is judged by visually inspecting the plots of some posterior samples across rounds. The chain is then thinned to reduce serial correlation by saving one observation in every 40 cycles. The posterior sample contains 2500 observations for the post-MCMC analysis. Considering each simulation is more time consuming, the simulation experiment was replicated 50 times for statistical power evaluation.

In order to demonstrate the flexibility of the Bayesian robust mapping proposed here, we use residual errors drawn from t-distribution with df=3 to generate the two samples of different size, according to model (1). Those data were analyzed by adopting the Bayesian robust mapping with a t-distribution, slash distribution and contaminated normal distribution for residuals, traditional Bayesian and non-Bayesian mapping procedures with normal residuals, respectively. The statistical powers of all the methods for QTL detection are given in Table 1. In general, Bayesian robust mapping has higher statistical powers for QTL detection than traditional Bayesian and non-Bayesian mapping if the residual error is subject to heavy-tailed distribution. The estimates for positions and effects of QTL detected by all methods are fairly close to true parameter values. As expected, the model is more robust with increased heritability and sample size (Tables 2 and 3). Statistical power of QTL detection increases as sample size and genetic contribution proportion increase. The type I error rates of all methods are <6%. On the whole, as statistical power rises, error rate falls.

Table 1.

Statistical power of QTL detection (%) and type I error rate (%, in the last column) obtained by various mapping methods

| Sample size | Distribution | QTL no. |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |||

| 150 | t | 70 | 100 | 48 | 92 | 56 | 36 | 2 |

| Slash | 62 | 92 | 26 | 90 | 20 | 20 | 4 | |

| Contaminated | 60 | 80 | 30 | 84 | 20 | 16 | 4 | |

| Normal | 36 | 74 | 8 | 80 | 6 | 2 | 6 | |

| Non-Bayesian | 16 | 28 | 0 | 32 | 4 | 0 | 6 | |

| 300 | t | 100 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 84 | 64 | 0 |

| Slash | 96 | 100 | 74 | 100 | 84 | 54 | 2 | |

| Contaminated | 76 | 100 | 42 | 100 | 36 | 34 | 2 | |

| Normal | 50 | 90 | 36 | 80 | 20 | 30 | 4 | |

| Non-Bayesian | 44 | 70 | 30 | 78 | 20 | 18 | 4 | |

Table 2.

Mean estimates and SDs (in parentheses) of QTL positions detected by various mapping methods

| Sample size | Distribution | QTL no. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 150 | True position | 56 | 148 | 267 | 359 | 56×267 | 148×359 |

| t | 55.3 (5.1) | 148.9 (2.4) | 268.2 (5.6) | 358.9 (3.5) | 57.8 (11.0)×267.9 (8.8) | 151.3 (7.7)×356.9 (6.3) | |

| Slash | 54.2 (4.8) | 148.4 (3.4) | 268.4 (3.0) | 358.7 (4.9) | 58.1 (8.9)×265.7 (9.2) | 150.1 (7.0)×358.2 (7.7) | |

| Contaminated | 56.2 (5.9) | 147.9 (4.3) | 269.0 (7.5) | 359.8 (3.9) | 57 (13.3)×263.8 (12.7) | 148.0 (6.8)×360.9 (9.2) | |

| Normal | 52.6 (4.2) | 148.1 (4.9) | 258.0 (9.8) | 359.4 (3.6) | 56.1 (13.0)×264.6 (15.2) | 143.0 (–)×360.0 (–)) | |

| Non-Bayesian | 55.7 (6.9) | 150.2 (5.4) | – | 361.3 (5.8) | 61.2 (15.1)×268.6 (18.4) | – | |

| 300 | t | 57.6 (2.9) | 148.3 (3.1) | 266.4 (3.5) | 357.5 (2.7) | 58.4 (5.3)×265.4 (7.8) | 149.8 (4.5)×359.3 (3.9) |

| Slash | 55.9 (3.1) | 149.4 (2.5) | 266.3 (4.6) | 357.9 (2.4) | 57.4 (3.8)×266.2 (7.3) | 150.6 (4.8)×359.0 (5.1) | |

| Contaminated | 56.0 (3.5) | 146.4 (2.9) | 264.3 (3.5) | 357.8 (3.0) | 57.7 (8.8)×269.0 (9.9) | 149.0 (3.5)×359.2 (5.4) | |

| Normal | 57.4 (3.9) | 147.9 (2.4) | 264.0 (6.1) | 359.4 (3.2) | 52.4 (10.1)×270.5 (10.5) | 145.0 (8.0)×358.4 (8.1) | |

| Non-Bayesian | 57.1 (4.1) | 149.5 (3.3) | 266.1 (7.3) | 359.0 (3.4) | 54.4 (13.6)×268.2 (10.1) | 151.7 (9.1)×360.8 (7.4) | |

Table 3.

Mean estimates and SDs (in parentheses) of QTL effects detected by various mapping methods

| Sample size | Distribution | QTL no. |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 150 | True Effect | 0.45 | 0.70 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.30 | 0.20 |

| t | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.73 (0.10) | 0.35 (0.06) | 0.57 (0.14) | 0.25 (0.09) | 0.23 (0.10) | |

| Slash | 0.51 (0.10) | 0.77 (0.13) | 0.38 (0.04) | 0.54 (0.09) | 0.23 (0.10) | 0.27 (0.13) | |

| Contaminated | 0.51 (0.12) | 0.76 (0.14) | 0.39 (0.17) | 0.62 (0.10) | 0.37 (0.12) | 0.26 (0.14) | |

| Normal | 0.56 (0.20) | 0.74 (0.22) | 0.46 (0.29) | 0.63 (0.14) | 0.39 (0.20) | 0.31 (–) | |

| Non-Bayesian | 0.81 (0.52) | 1.04 (0.44) | – | 0.87 (0.43) | 0.68 (0.48) | – | |

| 300 | t | 0.46 (0.07) | 0.70 (0.08) | 0.33 (0.13) | 0.57 (0.08) | 0.26 (0.07) | 0.23 (0.08) |

| Slash | 0.45 (0.09) | 0.72 (0.09) | 0.35 (0.07) | 0.56 (0.08) | 0.25 (0.09) | 0.25 (0.09) | |

| Contaminated | 0.45 (0.09) | 0.70 (0.12) | 0.39 (0.18) | 0.60 (0.14) | 0.35 (0.09) | 0.25 (0.12) | |

| Normal | 0.52 (0.19) | 0.72 (0.14) | 0.41 (0.28) | 0.61 (0.18) | 0.36 (0.18) | 0.28 (0.17) | |

| Non-Bayesian | 0.78 (0.41) | 0.89 (0.30) | 0.58 (0.38) | 0.83 (0.35) | 0.64 (0.42) | 0.51 (0.29) | |

We further generated normally distributed phenotypes by sampling residuals from normal distribution and analyzed them with both the Bayesian robust mapping and traditional Bayesian mapping. Results (provided in Section 1 of Supplementary Material) indicated that applying the Bayesian Robust analysis for data being normally distributed had similar powers as using traditional Bayesian mapping methods.

4 REAL DATA ANALYSIS

A 162 F10 RILs derived from the hybrids of Dasanbyeo (a Korean tongil type rice) × TR22183 (a Chinese japonica variety) had been designed for mapping QTL for traits associated with physical/chemical characteristics and quality of rice. On the basis of the population, we have constructed the framework linkage map of 1437.5 cM long using 208 SSR and STS markers. This map consists of the 16 linkage groups (LGs) for each parental map. We analyzed the data with the Bayesian robust mapping with different type of distributions and traditional Bayesian mapping procedure with normal residuals, respectively.

In all Bayesian analyses, based on results from the interval non-epistatic mapping (Lander and Botstein, 1989) and two-dimensional genome scan, the prior number of main-effect QTL was set at lm=3 and the prior expected number of all QTL (l0) was taken to be lm+5. The upper bound of the number of QTL, L, was then 16. The initial value of each unknown parameter took the same one as in simulation study. The MCMC was run for 200 000 cycles after the burn-in of 6000 cycles. It was found that the mapping results from 13 of 21 traits of interest support the Bayesian robust mapping procedure. Herein, we take the peak viscosity (PKV) as an example trait to compare the mapping results based on different residual distributions.

The estimates for positions and genetics effects of QTL detected with the Bayesian robust mapping and the traditional bayesian mapping method are listed in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Apparently, the results from different distributions are comparable: three main-effect QTLs and seven pairs of epistatic QTLs, covering all QTL detected by other methods, are identified with Bayesian robust mapping with a t-distribution, and followed by one main-effect QTL and four pairs of epistatic QTLs with slash distribution for residuals, one main-effect QTL and three with contaminated normal distribution for residuals and one main-effect QTL and two pairs of epistatic QTL with normal distribution for residuals, whereas only one main effect QTL on seventh LG with non-Bayesian method. This implies that Bayesian robust analysis has higher power than traditional Bayesian model selection and non-Bayesian method. Most of the main-effect and epistatic QTLs increase the PKV in rice, except for a third main-effect QTL and ninth pair of QTLs. All three different cases of two QTLs that involve the epistatic effects are found: (1) both QTLs are the main, as fourth and eighth pairs of QTL; (2) both QTLs are not the main, as seventh pair of QTL and the rest are that only one QTL is the main. Figures 1 and 2 (in Section 2 of supplementary data) plot the one-dimensional profiles of BFs for main effects and two-dimensional profiles of BFs for epistatic effects obtained from Bayesian robust mapping with a t-distribution for residuals, respectively. They intuitively illustrate the results from Bayesian robust analysis for genetic architecture of quantitative traits.

Table 4.

Estimated QTL positions (LG-position) obtained from Bayesian robust mapping with different distribution for residual on PKV in rice

| QTL no. | Distribution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | Slash | Contaminated | Normal | |

| 1 | 1-438.7 | – | – | – |

| 2 | 7-327.6 | 7-320.9 | 7-326.2 | 7-322.7 |

| 3 | 16-164.5 | – | – | – |

| 4 | (1-435.9)×(16-162.8) | (1-440.8)×16-183.6) | (1-439.2)×(16-175.2) | – |

| 5 | (1-309.4)×(12-11.5) | (1-302.1)×(12-13.2) | – | – |

| 6 | (1-443.2)×(6-23.8) | (1-447.5)×(6-33.2) | (1-436.2)×(6-32.6) | (1-450.8)×(6-30.7) |

| 7 | (1-65.6)×(1-253.2) | – | – | – |

| 8 | (7-327.6)×(16-164.5) | – | – | – |

| 9 | (4-24.8)×(16-160.8) | – | (4-28.3)×(16-162.1) | – |

| 10 | (9-27.3)×(16-168.7) | (9–25.9)×(16-175.1) | – | (9–28.4)×(16-162.1) |

Table 5.

Estimated QTL effects obtained from Bayesian robust mapping with different distribution for residual on PKV in rice

| QTL no. | QTL type | Distribution |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | Slash | Contaminated | Normal | ||

| 1 | Main Effect | 0.46(1.96) | – | – | – |

| 2 | Main Effect | 10.05(5.65) | 9.54(4.38) | 9.82(5.13) | 9.61(2.46) |

| 3 | Main Effect | −4.77(2.77) | – | – | – |

| 4 | Epistatic | 13.46(9.03) | 13.98(7.56) | 12.95(8.78) | – |

| 5 | Epistatic | 9.00(5.13) | 10.36(6.13) | – | – |

| 6 | Epistatic | 7.07(4.29) | 7.45(5.82) | 7.56(5.13) | 7.31(4.69) |

| 7 | Epistatic | 8.06(3.17) | – | – | – |

| 8 | Epistatic | 2.73(3.45) | – | – | – |

| 9 | Epistatic | −5.46(3.18) | – | −4.98(3.89) | – |

| 10 | Epistatic | 3.04(2.55) | 3.95(2.41) | – | 2.59(4.02) |

The numbers in parentheses are the 2logBF values.

5 DISCUSSION

Within the framework of Bayesian model selection for mapping genome-wide interacting QTLs, we develop a Bayesian robust mapping strategy for analyzing continuous non-normal quantitative traits, by replacing the normal distribution for residuals in multiple QTL model with the normal/independent distributions. Compared with Bayesian mapping for normal data, the Bayesian robust mapping strategy additionally sample ‘weight’ Wi and the robustness parameter df with the Gibbs sampler or Metropolis/Hastings algorithm in the MCMC process. Although computations for the robust models may be more than for their normal counterparts, the flexibility of the Bayesian robust mapping for either non-normal or normal data is enough to compensate for the cost. Of course, if the robustness parameter is assumed to be known, e.g. simply fixed at a small value (Gelman et al., 1995), the implementation of the Bayesian robust mapping will be even easier. In practice, however, unless there is a strong reason to believe in the adequacy of the normality assumption for residuals, it may be safer to use a robust model (Rosa et al., 2003, 2004).

Except for the three common normal/independent distributions discussed in this study, other distributions can also be considered, such as the Laplace and the double exponential distributions. Which distribution is optimal for fitting residuals depends on peculiarities of the dataset, such as the proportion of outliers and how far these are from the ‘center’ of the distribution. The t-distribution is the most commonly used thick-tailed distribution for robust inference, and is often a good alternative to a normal distribution. The contaminated normal distribution is the most flexible among the three robust distributions, but at the expense of an additional parameter. The slash distribution, although not often encountered in the literature, is the easiest one to implement in hierarchical modeling, because all conditional posterior distributions have closed forms.

Rohr and Hoeschele (2000) first implemented a robust Bayesian method for mapping QTL. Their study was different from ours in that: (1) their mapping analysis aimed at outbred population whereas ours at linecross; (2) their proposed method was based on a single QTL model whereas ours was based on a multiple QTL model; and (3) they used skewed Student's t-distributions to describe phenotypic residuals in the analysis whereas we adopted a student's t-distribution. In the single QTL model, it may be reasonable to assume that residuals follow skewed Student's t-distributions, because the ‘skewness’ may absorb the effects of other QTLs on phenotypes. However, no ‘skewness’ is necessary for the multiple QTL model.

A complete Bayesian mapping requires the sampling of genotypes for QTL and missing markers and aggravates the computational cost of Bayesian robust analyses. To alleviate this problem, we evenly partition the entire genome into small intervals by a number of points and restrict putative QTL to these fixed points, as proposed by (Yi et al., 2005). This strategy greatly reduces computational time by estimating all expected values of indicator variables for putative QTL by using conditional probability of their genotypes on two flanking markers before the MCMC procedure starts. Other ways to improve the efficiency of analyzing many QTL effects with Bayesian model selection include specifying prior inclusion probability for epistasis and using Metropolis/Hastings algorithm to perform fast sampling for binary indicator (Yi et al., 2007).

Funding: National Institutes of Health (R01 AR050496-01, R21 AG027110, R01 AG026564, and P50 AR055081, partial); Dickson/Missouri Endowment (to H.W.D.) the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grant 30471236 to R.Y.)

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A

Specification of prior for degree of freedom df in normal/independent distributions

In the t-distribution, we adopt a flat prior for df as df−1, yielding p(df)∝df−2 (Liu, 1996); A Gamma(a, b) distribution with small positive values of a and b (b≪a)can be adopted as a prior for df in the slash distribution; and the prior for df of contaminated normal distribution involves two parameters, i.e. df=(v τ). Herein, a Uniform (0, 1) distribution is used as a prior for τ and an independent Beta (a, b) is adopted as prior a for v.

Appendix B

Forms of posteriors for w and degree of freedom df in normal/independent distributions

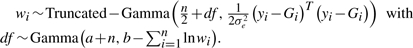

For a t-distribution, the fully conditional posterior density for each element of w is a Gamma distribution with parameters  and

and  , corresponding conditional posterior density of df is

, corresponding conditional posterior density of df is

which does not have an explicit form but a Metropolis/Hastings or rejection sampling step (Ripley, 1987) can be embedded in the MCMC scheme to obtain draws for df.

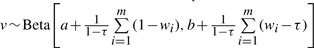

For slash distribution,

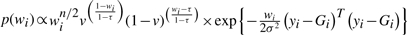

For contaminated normal distribution, the fully conditional posterior density for wi is also non-closed form:  with

with  .

.

REFERENCES

- Andrews DF, Mallows CL. Scale mixtures of normal distributions. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1974;36:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ball RD. Bayesian methods for quantitative trait loci mapping based on model selection: approximate analysis using the Bayesian information criterion. Genetics. 2001;159:1351–1364. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.3.1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppieters W, et al. A rank-based nonparametric method for mapping quantitative trait loci in outbred half-sib pedigrees: Application to milk production in a granddaughter design. Genetics. 1998;149:1547–1555. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster AP, et al. Iteratively reweighted least squares for linear regression when errors are normal/independent distributed. In: Krishnaiah PR, editor. Multivariate Analysis. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Diao G, et al. Mapping quantitative trait loci with censored observations. Genetics. 2004;168:1689–1698. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.023903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsen JM, et al. Alternative models for QTL detection in livestock. I. General introduction. Genet. Sel. Evol. 1999;31:213–224. [Google Scholar]

- Feenstra B, Skovgaard IM. A quantitative trait locus mixture model that avoids spurious LOD score peaks. Genetics. 2004;167:959–965. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.025437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez C, Steel M. On Bayesian modeling of fat tails and skewness. J. Am. Statist. Assoc. 1998;93:359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, et al. Bayesian Data Analysis. New York: Chapman & Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett CA. Model diagnostics for fitting QTL models to trait and marker data by interval mapping. Heredity. 1997;79:319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen RC. A general mixture model for mapping quantitative trait loci by using molecular markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1992;85:252–260. doi: 10.1007/BF00222867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1995;90:773–795. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak L, Lander ES. A nonparametric approach for mapping quantitative trait loci. Genetics. 1995;139:1421–1428. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.3.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander ES, Botstein D. Mapping Mendelian factors underlying quantitative traits using RFLP linkage maps. Genetics. 1989;121:185–199. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange K, Sinsheimer JS. Normal/independent distributions and their applications in robust regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993;2:175–198. [Google Scholar]

- Lange KL, et al. Robust statistical modelling using the t-distribution. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1989;84:881–896. [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. Bayesian robust multivariate linear regression with incomplete data. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1996;435:1219–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA. Robust estimation of the mean and covariance matrix from data with missing values. Applied Statistical. 1988;37:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro JC, et al. Efficient algorithms for robust estimation in linear mixed-effects models using the multivariate t distribution. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2001;10:249–276. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer MN, et al. Output analysis and diagnostics for MCMC, v. 0.9–5. 2004 Available at http://www-fis.iarc.fr/coda/(last accessed date March 2006) [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE, et al. Bayesian model averaging for linear regression models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1997;92:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rebaï A. Comparison of methods for regression interval mapping in QTL analysis with non-normal traits. Genet. Res. 1997;69:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley B. Stochastic Simulation. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers WH, Tukey JW. Understanding some long-tailed distributions. Stat. Neerl. 1972;26:211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Rohr PV, Hoeschele I. Bayesian QTL mapping using skewed Student-t distributions. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2002;34:1–21. doi: 10.1186/1297-9686-34-1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa GJM, et al. Robust linear mixed models with Normal/Independent distributions and Bayesian MCMC implementation. Biom. J. 2003;5:573–590. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa GJM, et al. Bayesian longitudinal data analysis with mixed models and thick-tailed distributions using MCMC. J. Appl. Stat. 2004;7:855–873. [Google Scholar]

- Sillanpää MJ, Corander J. Model choice in gene mapping: what and why. Trends Genet. 2002;18:301–307. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02688-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry: The Principles and Practice of Statistics in Biological Research. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Symons RC, et al. Multiple genetic loci modify susceptibility to plasmacytoma-related morbidity in Eμ-v-abl transgenic mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:11299–11304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162566999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, et al. Bayesian shrinkage estimation of quantitative trait loci parameters. Genetics. 2005;170:465–480. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.039354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R, et al. Box–Cox transformation for QTL mapping. Genetica. 2006;128:133–143. doi: 10.1007/s10709-005-5577-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi N, et al. Bayesian model selection for genome-wide epistatic quantitative trait loci analysis. Genetics. 2005;170:1333–1344. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.040386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi N, et al. Bayesian mapping of genomewide interacting quantitative trait loci for ordinal traits. Genetics. 2007;176:1855–1864. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.071142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YM, Xu S. Advanced statistical methods for detecting multiple quantitative trait loci. Recent Res. Devel. Genet. Breed. 2005;2:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zou F, et al. Rank-based statistical methodologies for quantitative trait locus mapping. Genetics. 2003;165:1599–1605. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.