Abstract

The role of canonical Wnt signaling in myofibroblast biology has not been fully investigated. The C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cell line recapitulates myofibroblast differentiation in vitro and in vivo, including SM22α expression. Using this model, we find that Wnt3a upregulates SM22α in concert with TGFβ1. Wnt1, Wnt5a and BMP2 could not replace Wnt3a and TGFβ1 signals. Chromatin immunoprecipitation identified that Wnt3a enhances both genomic SM22α histone H3 acetylation and β-catenin association, hallmarks of transcriptional activation. By analyzing a series of SM22α promoter –luciferase (LUC) reporter constructs, we mapped Wnt3a-regulated DNA transcriptional activation to nucleotides −213 to −192 relative to the transcription initiation site. In gel shift assays, DNA-protein complexes assembled on this element were disrupted with antibodies to β-catenin, Smad2/3, and TCF7, confirming the participation of known Wnt3a and TGFβ transcriptional mediators. Mutation of a CAGAG motif within this region abrogated recognition by these DNA binding proteins. Wnt3a treatment increased Smad2/3 binding to this element. Mutation of the cognate within the context of the native 0.44 kb SM22α promoter resulted in a 70% decrease in transcription, and reduced Wnt3a + TGFβ1 induction. A concatamer of SM22α [−213 to −192] conveyed Wnt3a + TGFβ1 activation to the unresponsive RSV promoter. Dominant negative TCF inhibited SM22α [−213 to −192]×6 RSVLUC activation. Moreover, ICAT (inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF) decreased while TCF7L2 and β-catenin enhanced 0.44 kb SM22α promoter induction by Wnt3a + TGFβ1. RNAi “knockdown” of β-catenin inhibited Wnt3a induction of SM22α. Thus, Wnt/β-catenin signaling interacts with TGFβ/Smad pathways to control SM22α gene transcription.

Keywords: Msx2, Wnt, β-catenin, type II diabetes, myofibroblast, vascular calcification

INTRODUCTION

Intimal-medial thickening, arterial calcification, and aortic valve calcification –pathologies dependent upon the vascular myofibroblast -- are clinically significant changes induced by type II diabetes [T2DM]1 and metabolic syndrome(1). Since pericytic myofibroblasts have emerged as vascular osteoprogenitors (2–4), signals that expand the adventitial myofibroblast pool are also predicted to increase the potential for arterial calcium deposition in addition to neointima formation(2). A better understanding of the osteotropic stimuli that regulate myofibroblast cell physiology is needed to address the burgeoning aortic and arteriosclerotic disease burden of T2DM(5–7).

β-catenin – regulated transcription contributes to macrovascular phenotypic changes observed in T2DM – including osteochondrogenic differentiation of vascular myofibroblasts (8–10). In our studies of diet-induced obesity and T2DM, we identified that high fat diets typical of western societies activate an osteogenic Msx2-Wnt gene regulatory program in aortic myofibroblasts(10). This β-catenin - mediated transcriptional response promotes arterial calcification in part by upregulating bone alkaline phosphatase in CVCs [calcifying vascular cells] and mural myofibroblasts (2, 9, 11, 12). Multiple Wnt ligands that increase alkaline phosphatase via LRP5/LRP6 activation and “canonical” β-catenin signaling (13) were ectopically induced in the calcifying aorta in response to diabetes, Msx2, and inflammation(10, 14, 15). Wnt3a and Wnt7a were prominently induced, along with Wnt5a, a “non-canonical” Wnt that is constitutively expressed in the aorta at high levels(16).

Msx2 is a homeodomain transcription factor that promotes osteogenic differentiation of vascular myofibroblasts, mediated in part via the paracrine Wnt signals noted above (14, 17, 18). The TNFα- driven inflammation and oxidative stress of T2DM initiates osteogenic Msx2 signaling in the aorta (15). In previous studies, we noted that Msx2 did not uniformly suppress smooth muscle cell [SMC] phenotypic markers while promoting osteogenic differentiation; rather Msx2 upregulated early SMC genes such as SM22α (18). However, in a cell-autonomous fashion, Msx2 inhibits myocardin-dependent transcription via antagonistic protein-protein interactions that prevent SM22α transcription (19). Thus, we posited that paracrine Wnt signals elaborated by Msx2- expressing cells might mediate SM22α induction (14, 20).

In this study, we specifically examined whether SM22α expression was controlled by Wnt3a and Wnt5a, two distinct Wnt ligands upregulated by diabetes, inflammation, and Msx2 in vascular myofibroblasts (14, 15). We demonstrate that SM22α expression is augmented by Wnt3a signaling, with transcriptional regulation conveyed in part via a novel CAGAG regulatory element in the SM22α promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Cell Culture

Tissue culture plasticware was manufactured by Costar. All other cell culture reagents and custom synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides were ordered from Invitrogen. Purified basic chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mouse C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (CCL-226). C3H10T1/2 cells were passaged in basal media with 10% FBS (fetal bovine serum), 1 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin and streptomycin and transfected or treated in DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, high glucose) containing the same concentrations of FBS, L-glutamine, and penicillin-streptomycin. All experiments were done with C3H10T1/2 cells between the 15th and 22nd passage. Recombinant Wnt3a (Cat. # 1324-WN-002/CF), BMP2 (Cat. # 355-BM-010/CF), and TGFβ1 (Cat. # 240-B-010/CF), were purchased from R & D Systems and lyophilized protein was reconstituted in 1:10 BSA/PBS prior to use. Cells were treated with 15 ng/ml Wnt3a, 5 ng/ml TGFβ1, or 100 ng/ml BMP2 unless otherwise noted. Western blots were performed as previously described(21), loading 10 ug of cellular protein extracted per lane. Where indicated, analysis of digital JPEG images was used to quantify signal intensities using Kodak 1D image analysis software as previously detailed(21). Antibodies to SM22α (ab14106), β-catenin (sc-1496) and eIF2α (sc-11386) were obtained from Abcam and Santa Cruz as indicated. Recombinant Smad3 (#RP-1604; expressed in and purified from E. coli as a GST fusion protein) was purchased from Cascade Bioscience (Winchester, MA).

Real-time Fluorescence RT-PCR Analysis

To quantify relative mRNA levels, fluorescence RT-qPCR was performed as previously detailed(18). Amplimers were designed with Primer Express Software v2.0 (Applied Biosystems). Specific amplimers used were as follows: SM22α, 5′- AAG ACT GAC ATG TTC CAG ACT GTT G-3′ and 5′- TGC CAT ATC CTT ACC TTC ATA GAG G-3′; SM α-actin, 5′- CGG GAG AAA ATG ACC CAG ATT AT-3′ and 5′- GGA CAG CAC AGC CTG AAT AGC-3′; SM-MHC, 5′- AAG CCT GCA TTC TCA TGA TCA AA-3′ and 5′- TGT ACA GGT TAG GGT CAA GTT CGA G-3′; PPARγ, 5′-ACC ACT CGC ATT CCT TTG AC-3′ and 5′- TGG GTC AGC TCT TGT GAA TG-3′; necdin, 5′- CCA ATC TCC ACA CCA TGG AGT T-3′ and 5′- ATA CGG TTG TTG AGC GCC A-3′; Dlxin, 5-‘ ATG AGA CTA GCA AGA TGA AAG TGC TG-3′ and 5′- TCT TCT GAA CCT CTG CAA TGA ATC-3′; Runx2, 5′- AGG AGG GAC TAT GGC GTC AA-3′ and 5′- TCG GAT CCC AAA AGA AGC TTT-3′; and 18S, 5′-CGG CTA CCA CAT CCA AGG AA-3′ and 5′- GCT GGA ATT ACC GCG GCT-3′ ′. Real-time fluorescence analysis was performed in 96-well plates with Sybr Green as the intercalating fluorophore (Applied Biosystems). Data was collected on an ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System and the relative mRNA abundance was referenced to 18S rRNA in each sample(14, 15, 18). Taqman assays for quantifying Wnt1 [Mm00810320_s1], Wnt3a [Mm03053669_s1], Wnt5a [Mm004373347_m1] mRNA accumulation with GAPD normalization [Mm03302249_g1] were purchased from Applied Biosystems, and data collected with the ABI 7300. Results are presented as the mean and error for multiple independent replicates (n = 3 to 9).

Reporter and Expression Constructs, Transfections, and Luciferase Assays

All plasmid preparations were purified using Qiafilter Maxi prep columns (Qiagen) and were sequence verified (Big Dye v3.1, Applied Biosystems, Protein and Nucleic Acid Chemistry Lab, Washington University). The −441 to +5 region of the mouse SM22α promoter was cloned from C57/BL6 mouse whole genomic DNA into the KpnI/MluI site of the pGL2-Basic luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega) using techniques previously described(22). All of the SM22α 5′ deletion constructs were derived from this original plasmid and were also cloned into the KpnI/MluI restriction site of pGL2-Basic. The 1-, 3-, and 6- copy concatamers of the wild type −213 to −192 region of SM22α were synthesized as phosphorylated complementary single stranded oligonucleotides annealed together, and ligated upstream of the RSV minimal promoter – LUC reporter(22). All of the −213 to −192 sequence elements are in the native 5′-to-3′ orientation relative to the transcription initiation site. Expression constructs for Smad2(Δexon3), Smad3, Smad2(FL), Smad7, and ICAT were cloned by PCR from C3H10T1/2 and primary aortic SMC cDNA generated in the course of this project using methods previously detailed.(23) Each construct was ligated into the pcDNA3 expression vector (Invitrogen). The wild type TCF construct CMV-TCF4/TCF7L2 (TCF4 is TCF7L2, OMIM #602228) was purchased from Upstate-Millipore (cat. #21-174). Similarly, the dominant negative TCF construct pcDNA-dnTCF4/dnTCF7L2 was also purchased from Upstate-Millipore (cat. # 21-206). All transfections were done in 12-well tissue culture plates and each transfection experiment used either 10 μg or 12 μg of DNA per 12-well plate, (~ 1 ug/well) as previously described(24). For treatment studies, C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected in batch mode at 50% confluence using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, and luciferase assays performed 48 hours later precisely as previously detailed(22). Data are presented as the mean +/− S.E.M. luciferase activity per well (n = 6 for each treatment condition, repeated at least once in an independent experiment).

Electrophoretic mobility gel shift assays

Gel shift assays, cold competition, and immunological probing/supershift assays were carried out as previously detailed(22, 25). Antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, obtained either as “TransCruz” reagents, or concentrated 10-fold by centrifugal filtration (Centricon YM-30; final antibody concentrations all 2 ug/ul). The antibodies used were anti-β-catenin (sc-1496), anti-LEF1 (sc-8591), anti-TCF7 (sc-8589), anti-Smad2/3 (sc-6202, I-20, directed to domain shared by Smad2, Smad2Δexon3, and Smad3 residues 130–180), anti-Smad3 (sc-8332) and anti-Smad4 (sc-1909). Gamma-[32P] ATP was purchased from New England Nuclear, and used to 5′- label one of the oligonucleotide strands prior to annealing as previously detailed(25). Whole cell extracts for gel shift assay were prepared as previously described (22) obtained from C3H10T1/2 cells treated with 15 ng/ml recombinant Wnt3a for 4 hours, 20 hours, or 24 hours as indicated. DNA-protein complexes were visualized by native gel electrophoresis precisely as previously detailed(24), using 4–20% acrylamide gradient gels (Invitrogen) pre-equilibrated with 0.375X Tris – borate -EDTA buffer, pH 8.3, For cold competition experiments, lysate was incubated for 20 minutes with unlabeled duplex oligonucleotide in 45-fold or 90-fold molar excess of the radiolabeled probe. Immunological probing of DNA-protein complexes was carried out with antibody—extract pre-incubation precisely as detailed(22), evaluating 2 ul of the indicated antibody (2 ug/ul) in a 20 ul gel shift binding reaction.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

ChIP assays were performed following the novel “fast ChIP” protocol of Nelson and colleagues (26, 27), but with the addition of a brief micrococcal nuclease genomic DNA digestion (1U/ml for 20 minutes at 37 ºC in 50 mM Tris HCl pH8 with 5 mM CaCl2 and 0.5 mM DTT, followed by EDTA inactivation) just prior to the DNA sonication step. Specific antibodies used for ChIP were anti-histone H3 (Abcam #1791), anti-acetylated histone H3 (Abcam #4441), and a validated anti-β-catenin H102 (Santa Cruz, sc-7199), using normal mouse IgG (Upstate Biotechnology Inc., #12-371) as the negative control. ChIP assays utilized 4 ug/ml antibody per 100 ul of sonicate obtained from one 15 cm culture dish of C3H10T1/2 cells (~ 2 × 107 cells/1 ml of sonicate). Chelex 100 – based DNA purification and reversal of cross-links following ChIP were carried out as detailed (26, 27), followed by fluorescence PCR to quantify SM22α mouse genomic DNA in both the input and precipitate as previously described (24). The amplimer pair implemented in qPCR for SM22α promoter ChIP assays was 5′-ATG TTC TGC CAT GCA CTT GGT AGC-3′ and 5′-GAC AAA CAA GCC ACC TTC TTG CAA-3′. Data are expressed as the mean +/− standard error of the relative amount ofSM22α genomic DNA precipitated, normalized to input DNA. All ChIP assays were performed as independent replicates in duplicate (n = 4 to 8 per treatment group as indicated).

siRNA mediated RNA interference

C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected at 50% confluence with a validated double stranded siRNA targeting β-catenin message (5′-r(CUG UUG UGG UUA AAC UCC U)dTdT-3′ and 5′-r(AGG AGU UUA ACC ACA ACA G)dTdT-3′), siRNA targeting all Smad2 messages (5′-r(AUC AGC CGG UGG GUC UGG A)dTdT3′ and (21 bp) antisense strand = 5′-r(UCC AGA CCC ACC GGC UGA U)dTdT-3′), or with AllStars Negative Control siRNA (Qiagen cat #1027281) as indicated, using TransIT- TKO Transfection Reagent (Mirus, Madison, WI). Cells were washed and treated with recombinant protein 24 hours after transfection. After one day of treatment, cells were harvested and RNA was extracted, and RT-qPCR performed, using the primers listed above. Statistical analysis was carried out by ANOVA as indicated, followed by post-hoc Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons using GraphPad InStat software version 3.06 for Windows.

RESULTS

Wnt3a upregulates SM22 gene expression programs in C3H10T1/2 cell mesenchymal progenitors

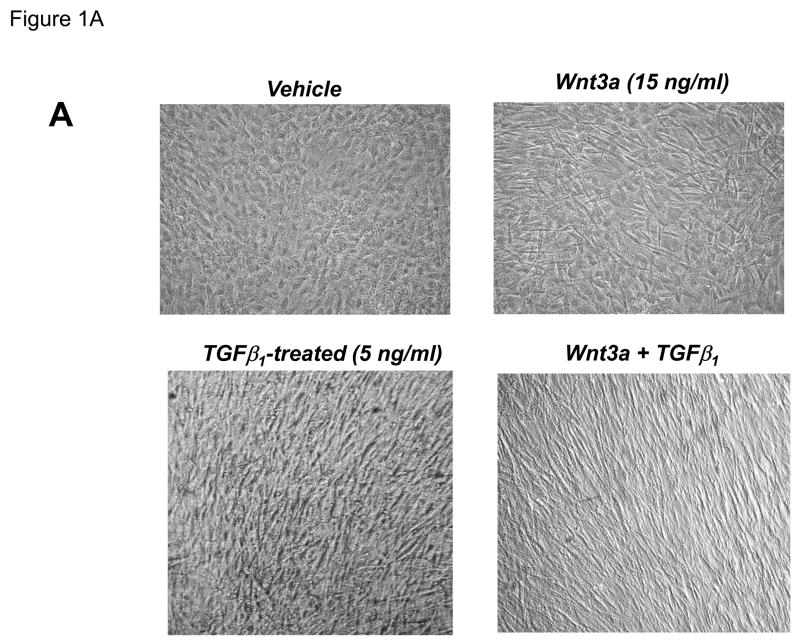

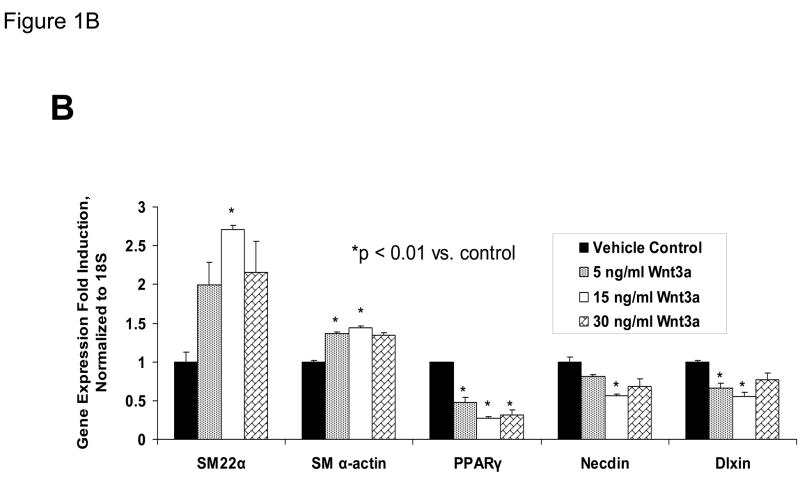

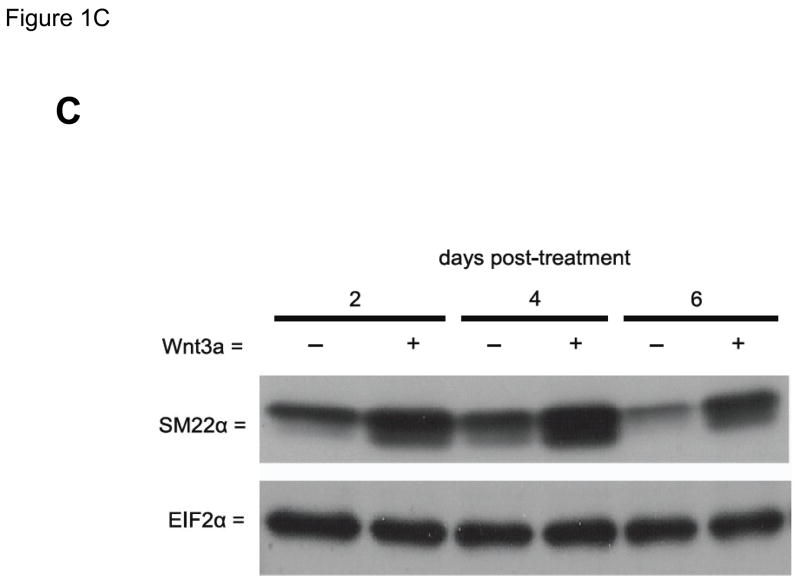

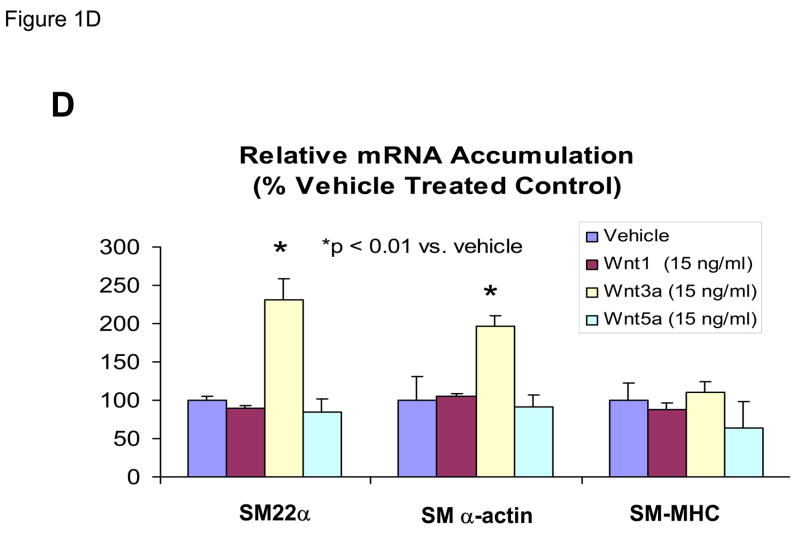

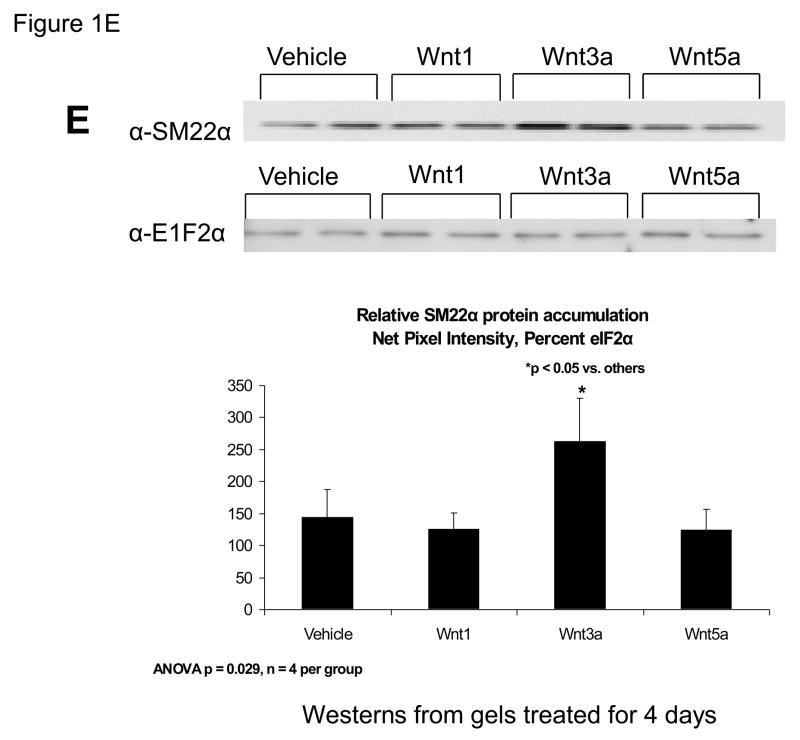

Our previous studies had indicated that Msx2-Wnt signaling controls cell fate and phenotype of aortic adventitial myofibroblasts, controlling osteogenic, adipogenic, and smooth muscle cell markers(14, 18). This included upregulation of SM22α (18), a SMC-specific marker(28) also transiently expressed during cardiomyocyte development(29). Like the aortic adventitial myofibroblast, the murine C3H10T1/2 cell line is a multipotent mesenchymal progenitor that is regulated by Msx2-Wnt signaling(14, 18, 30). We wished to better understand the effects of canonical Wnt signaling on early SMC differentiation; therefore, we examined the effects of Wnt3a on C3H10T1/2 cells as a facile, relevant cell culture model(31, 32). As shown in Figure 1A, treatment of Wnt3a causes a dramatic morphological change in C3H10T1/2 cells, inducing the formation of a spindly, myofibroblastic shape(33, 34). Wnt3a-induced morphological changes were observed in both the absence and presence of TGFβ1 (Figure 1A). RT-qPCR analysis of treated C3H10T1/2 cultures confirmed that 15 ng/ml Wnt3a consistently and significantly upregulated SM22α, a gene encoding an early myofibroblast phenotypic marker(35–38) that binds SMC α-actin (Figure 1B)(34, 39). Induction of SMC α-actin itself by Wnt3a treatment was also observed but more modest in magnitude. By contrast, expression of PPARγ, a characteristic marker and mediator of adipocyte differentiation, was not induced by Wnt3a treatment, and was in fact suppressed by Wnt3a (Figure 1B, and data not shown). The transcriptional co-regulators necdin, and Dlxin, implicated in Msx2-dependent SMC signaling(40), were not induced by Wnt3a (Figure 1B). Western blot analysis of C3H10T1/2 cell extracts confirmed that the Wnt3a-induced changes in SM22α mRNA were accompanied by increased SM22α protein accumulation (Figure 1C, see also Figures 1E & 2B with 4 day quantification), but with little change in SMC α-actin protein levels (data not shown). Unlike recombinant Wnt3a, recombinant Wnt1 and Wnt5a did not induce SM22α mRNA accumulation (Figure 1D). While induction of SM α-actin again paralleled SM22α induction, no induction of the mature VSMC marker SM-MHC (smooth muscle myosin heavy chain), was observed (Figure 1D). Moreover, upon comparison of responses between Wnt1, Wnt3a, and Wnt5a, only Wnt3a significantly increased SM22α protein accumulation (Figure 1E, p < 0.05 by one-way ANOVA). Thus, in C3H10T1/2 multipotent mesenchymal cells (14, 18, 30–32, 35, 37, 41), Wnt3a upregulates SM22α gene expression and protein accumulation, and induces shape change characteristic of the early myofibroblast phenotype.

Figure 1. Wnt3a induces spindle-shaped morphology change and upregulates SM22α mRNA accumulation in C3H10T1/2 multipotent mesenchymal cells.

Panel A, C3H10T1/2 cells were treated either with vehicle, 15 ng/ml recombinant purified Wnt3a, 5 ng/ml recombinant purified TGF-β1, or with both ligands as indicated for 7 days as indicated. Panel B, within 4 days of treatment, 15 ng/ml Wnt3a significantly upregulates SM22α mRNA accumulation. Panel C, western blot analysis confirms that Wnt3a increases SM22α protein levels as well (see also Figs. 1E and 2B). Duplicate blots are shown, representative of the 4 independent blots analyzed by digital image analysis. Unlike Wnt3a, Wnt1 and Wnt5a do not upregulate SM22α mRNA accumulation (panel D) or SM22 protein levels (panel E). All Wnt treatments were at 15 ng/ml.

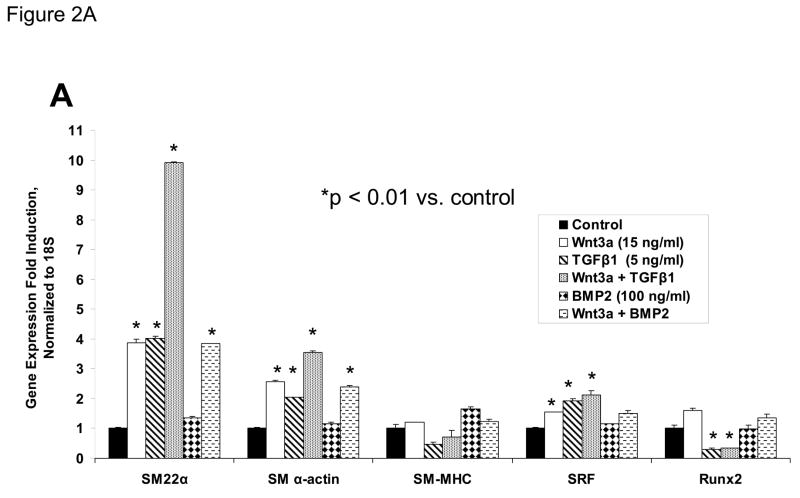

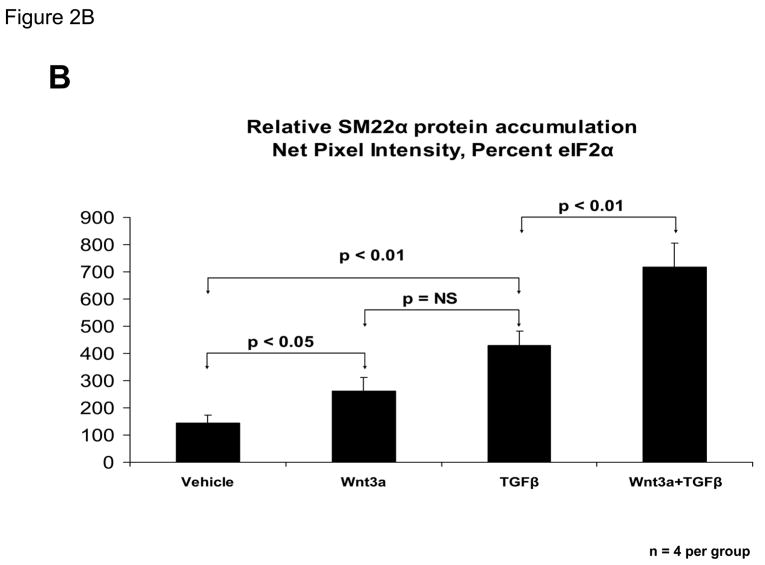

Figure 2. Wnt3a and TGFβ1 signals augment SM22α expression in C3H10T1/2 cells.

C3H10T1/2 cells were treated for 4 days with either vehicle, 15 ng/ml Wnt3a, 5 ng/ml TGFβ1, and/or 100 ng/ml BMP2 in the combinations indicated. Total cellular RNA was extracted and gene expression analyzed by RT-qPCR as described in “Materials and Methods.” Wnt5a (15 ng/ml) was unable to replace Wnt3a actions in this assay (data not shown). Panel B, quantitative western blot analysis confirms that Wnt3a is capable of significantly augmenting SM22α protein accumulation in either the presence or absence of TGFβ1. Data were obtained from quantitative image analysis of 4 independent replicates following 4 days of the indicated treatments, normalizing the SM22α signal to eIF2alpha signal in each sample.

Wnt3a converges with TGF-β1 signaling to upregulate SM22α gene expression

TGFβ is an important stimulus for myofibroblast formation(33), and promotes myofibroblast differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells(31, 35). TGFβ1 prominently induces SM22α transcription in primary myofibroblasts(31). We therefore contrasted and compared the effects of TGFβ1 and Wnt3a on SM22α gene expression. TGFβ1 upregulated SM22α mRNA accumulation in C3H10T1/2 cells, to a level equivalent to or greater than that of Wnt3a treatment alone (Figure 2A). Simultaneous treatment with both TGFβ1 and Wnt3a induced SM22 up to 10-fold (Figure 2A). By contrast, no induction of SM22α expression was observed when BMP2 treatment -- an osteogenic TGF-β superfamily member – was applied alone or in combination with Wnt3a (Figure 2A). Induction of SM α-actin exhibited a weakly additive interaction between TGFβ1 and Wnt3a -- similar to changes in the transcript for SRF (serum response factor) (Figure 2A). Moreover, the late SMC marker SM – MHC exhibited no induction with Wnt3a and TGFβ (Figure 2A) TGFβ1 inhibited induction of the osteoblast transcription factor Runx2 (42), consistent with the promotion of an early myofibroblast phenotype (33). Western blot analysis confirmed that Wnt3a was capable of further augmenting SM22α protein accumulation even in the presence of TGFβ1 (Figure 2B). Thus, Wnt3a and TGFβ1 signals interact to upregulate SM22α gene expression in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal progenitors(18, 31).

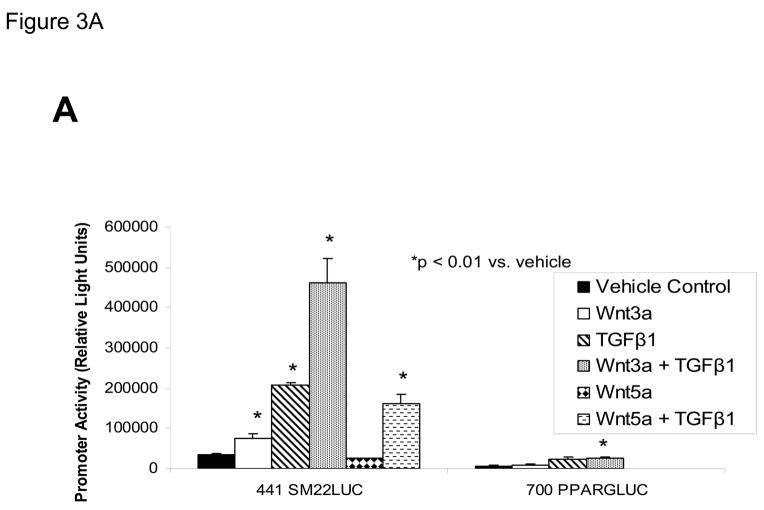

Wnt3a and TGFβ1 activate transcription driven by the SM22α promoter

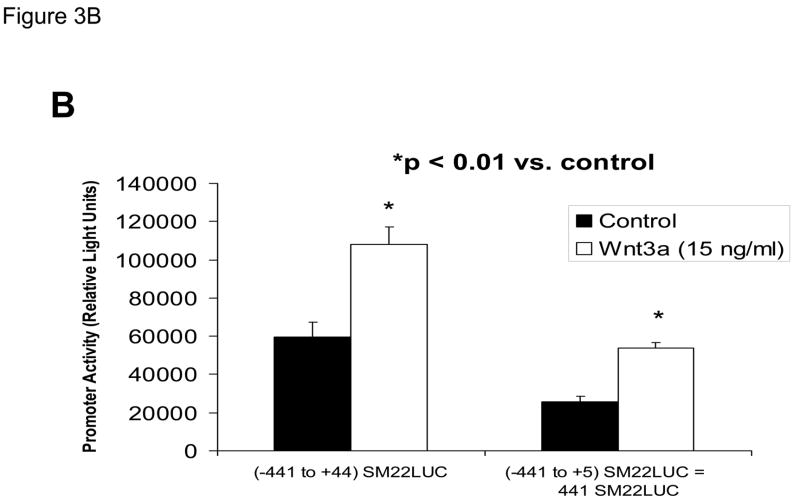

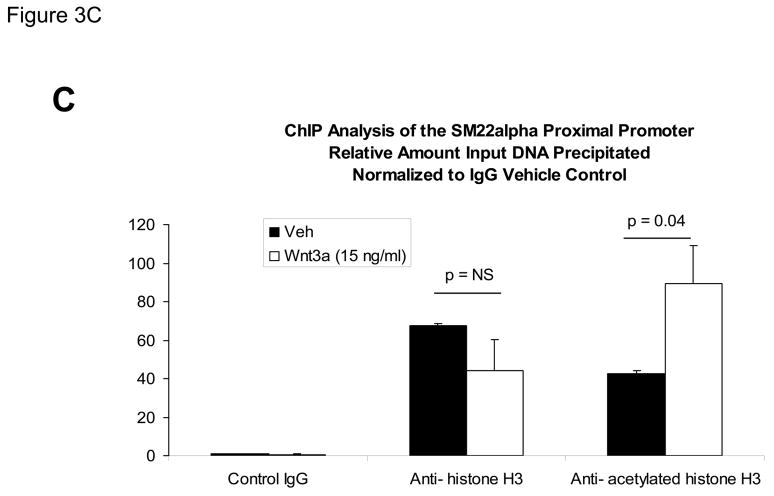

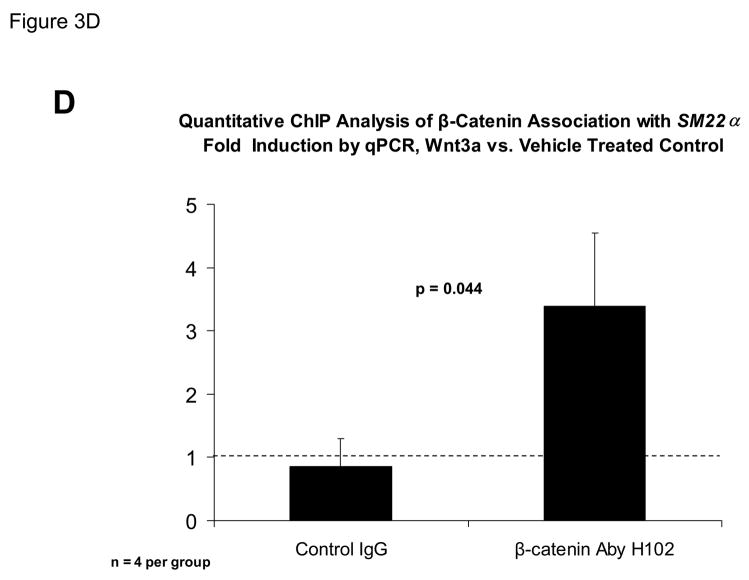

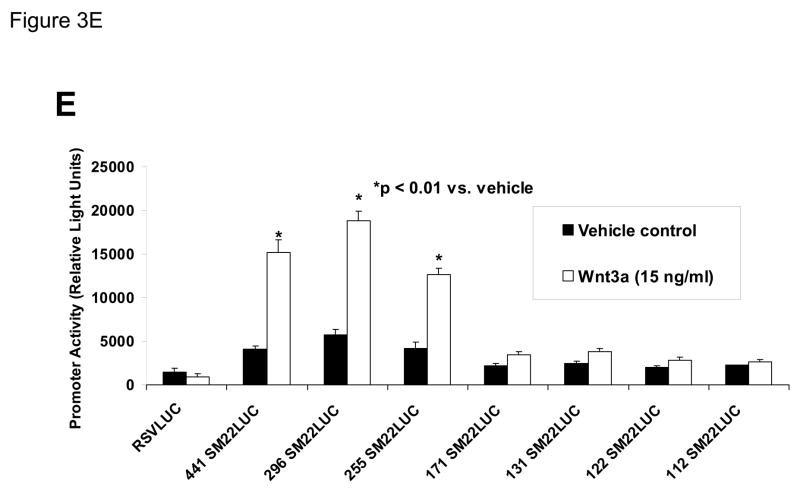

The proximal 0.44 kb of the SM22α promoter contains information necessary and sufficient for arterial SMC gene expression in transgenic mice(28, 29, 41, 43, 44); thus we transiently transfected C3H10T1/2 cells with 441 SM22LUC, a LUC (luciferase) reporter construct containing SM22α promoter nucleotides −441 to +5, and examined the effects of Wnt3a treatment. As shown in Figure 3A, Wnt3a treatment either alone or in the presence of TGFβ1 significantly upregulated transcription driven by the SM22α promoter. Once again, the effect was specific for the canonical Wnt3a ligand, since Wnt5a had no effect (Figure 3A). The transcriptional response was specific, since neither the proximal 700 bp of the PPARγ (peroxisome proliferators activated receptor) promoter (700 PPARGLUC; Figure 3A) nor that of RSVLUC (see below) were Wnt3a responsive in C3H10T1/2 cells. Of note, Wnt3a induction was independent of the critical and novel Smad regulatory element of Li et al.(29, 35, 43) recently defined as residing between +5 and +44 (Figure 3B). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays confirmed that Wnt3a activated SM22α transcription in C3H10T1/2 cells; Wnt3a treatment significantly increased both histone H3 acetylation (Figure 3C) and β-catenin association (Figure 3D) with SM22α genomic chromatin in C3H10T1/2 cells, indices of transcriptional activation via canonical Wnt signaling (38, 45).

Figure 3. Transcription driven by the 0.44 kb SM22α promoter is stimulated by Wnt3a, alone and in concert with TGFβ1.

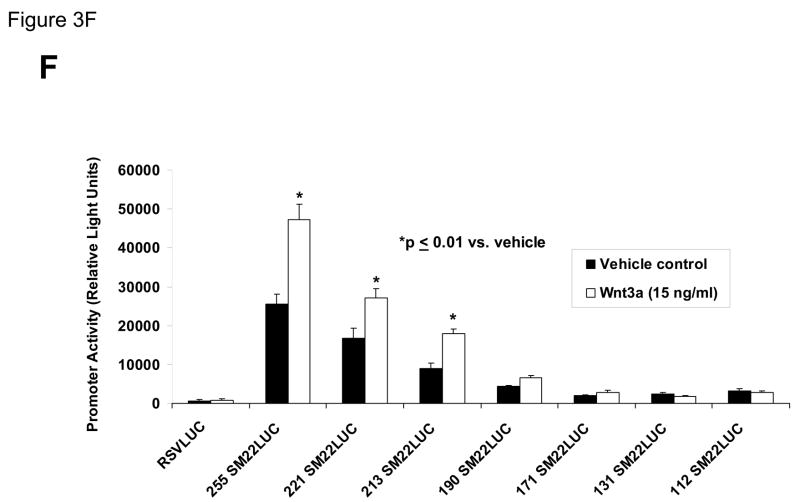

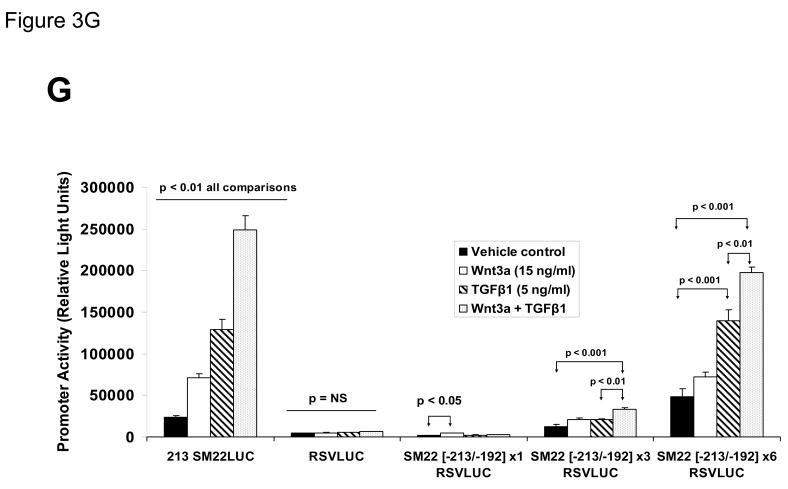

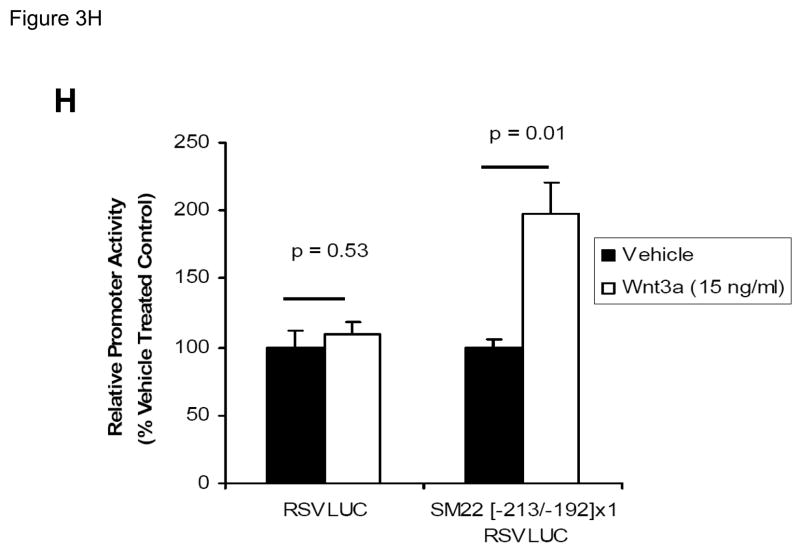

Panel A, C3H10T1/2 cells were transiently transfected with 441 SM22LUC, a construct possessing SM22α promoter region −441 to +5 upstream of the LUC reporter of plasmid pGL2, and treated with vehicle, Wnt3a (15 ng/ml), TGFβ1 (5 ng/ml) and/or Wnt5a (30 ng/ml) as indicated. Panel B, addition of nucleotide +5 to +44, encompassing although augmenting basal activity, the novel exon 1 SBE(43), increased basal activity but was not required for Wnt3a responsiveness. Wnt3a (15 ng/ml, 5 hours) treatment increased SM22α histone H3 acetylation (panel C) and β-catenin binding (panel D) in ChIP assay, confirming transcriptional activation. Panels E & F, a SM22α promoter 5′-deletion series was analyzed to map the Wnt3a response between nucleotides −213 and −190. Panel G, concatamers of 3- and 6-copy direct repeats of SM22α promoter region −213 to −192 conveyed Wnt3a + TGFβ1 responsiveness onto the unresponsive RSV minimal promoter of RSVLUC. Panel H, a single copy of SM22α[ −213/−192] can convey Wnt3a responsiveness to the RSV promoter.

To begin mapping the SM22α promoter elements conveying this Wnt3a transcriptional response, we generated and analyzed a systematic series of 5′-prime promoter deletion constructs. The Wnt3a response mapped to the SM22α promoter region −255 to −171 (Figure 3E). More refined 5′-prime mapping placed the element between −213 and −190 (Figure 3F). Furthermore, a concatemer of the SM22α promoter region −213 to −192 conveyed Wnt3a and TGFβ1 responsiveness when placed upstream of the unresponsive RSV (Rous Sarcoma Virus) minimal promoter (Figure 3G). Albeit at a low level of overall transcriptional activity, a single copy of the −213/−192 element was capable of conveying a Wnt3a response onto the RSV promoter (Figure 3H). Thus, in concert with TGFβ, Wnt3a upregulates SM22α promoter activity via a novel transcriptional element located between −213 to −192 relative to the start site of SM22α gene transcription.

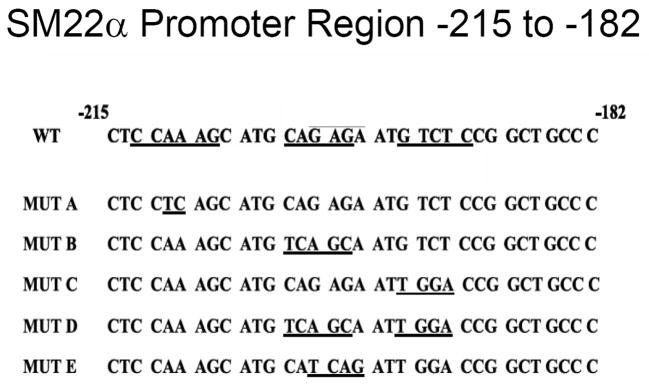

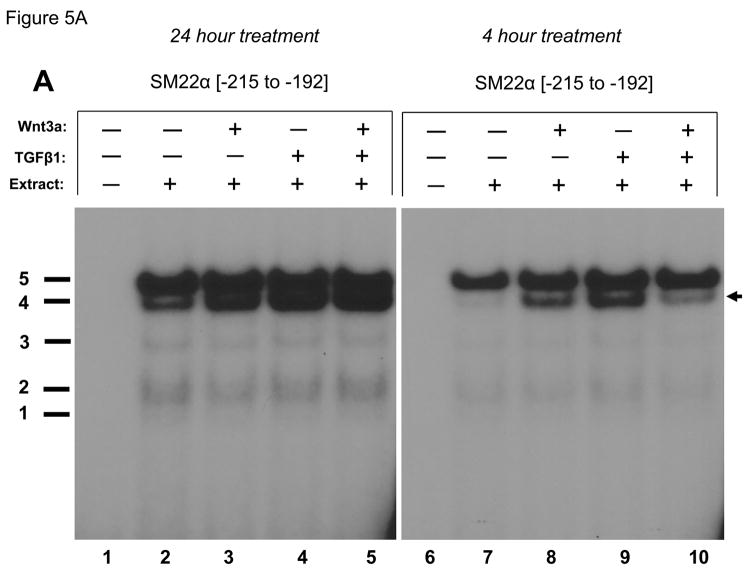

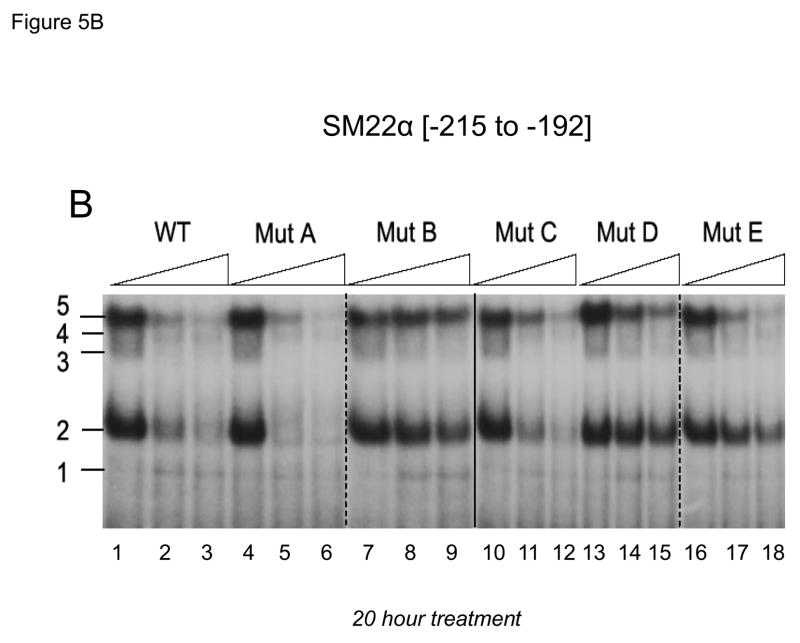

A functionally important CAGAG element in the SM22α promoter region −213 to −192 assembles complexes containing β-catenin, TCF7, and Smad2Δexon3

Previous studies have shown that members of the TCF and Smad gene families characteristically mediate responses to canonical Wnt ligands and TGFβ1, respectively(13, 46). Inspection of the DNA sequence encoded by the SM22α promoter element −213 to −192 identified a central CAGAG motif – a sequence having features of both CAAAG TCF recognition and CAGA Smad binding cognates (Figure 4). This CAGAG element is flanked by upstream CAAAG and downstream GAGAC (on bottom strand; top = GTCTC) motifs that also resemble TCF (13)and Smad (46)cognates. To begin to characterize the protein-DNA complexes assembled by this region of the SM22α promoter, we performed electrophoretic mobility gel shift assays using cell extracts prepared from vehicle and Wnt3a –treated cells. Four specific (bands 2 – 5) and one variable non- specific (band 1) DNA-protein complexes were observed to bind radiolabeled duplex oligo encoding SM22[−215/−182] (Figure 5A, lane 2 vs. lane 1). In response to treatment with either Wnt3a, TGFβ1, or both for 24 hours (Figure 5A, lanes 2–5) the relative intensity of complex 4 appeared to increase. This was confirmed in an independent experiment using extracts prepared from C3H10T1/2 cells treated for only 4 hours (Figure 5A, lanes 6–10). As compared to vehicle treated control, either Wnt3a (Figure 5A, lane 8) or TGFβ1 (Figure 5A, lane 9) increased the relative intensity of complex 4 formation on SM22[−215/−182] compared with other complexes. (All gel shift data presented are representative of results observed in 2 to 5 independent experiments; data not shown). A series of systematically altered and unlabeled duplex oligonucleotides were then tested for the capacity to compete for the formation of these complexes (cold-competition assays; see Figure 4 for sequences). Unlabeled duplex oligo SM22[−215/−182] competed for complexes 2 – 5 (Figure 5B lanes 1–3, WT). Similar results were obtained when a duplex oligo containing the disrupted upstream CAAAG motif (Figure 5B, lanes 4–6, mutA). By contrast, a duplex oligo that destroyed the central CAGAG cognate could not efficiently compete for formation of any of the 4 specific protein-DNA complexes visualized (Figure 5B, lanes 7–9, mutB). Disruption of the downstream GAGAC (GTCTC top strand) had no effect (Figure 5B, lanes 10–12, mutC), but the combination of CAGAG motif disruption with this latter alteration once again precluded activity in these cold competition assays (Figure 5B, lanes 13–15, mutD). Interestingly, a second duplex oligo that perturbed the more 3′-region of the central CAGAG cognate preferentially attenuated complex 2 formation (Figure 5B, lanes 16–18, band 2 is not fully competed away by mutE). Immunological probing subsequently identified that complexes 2, 3 and 4 contain Smad2 (see below).

Figure 4. The SM22α promoter sequence −215 to −182.

Three elements resembling known cognates for TCF/LEF and Smad recognition are underlined. A series of synthetic duplex oligonucleotides possessing alterations/mutations that disrupted these potential binding cognates were generated for gel shift competition assays.

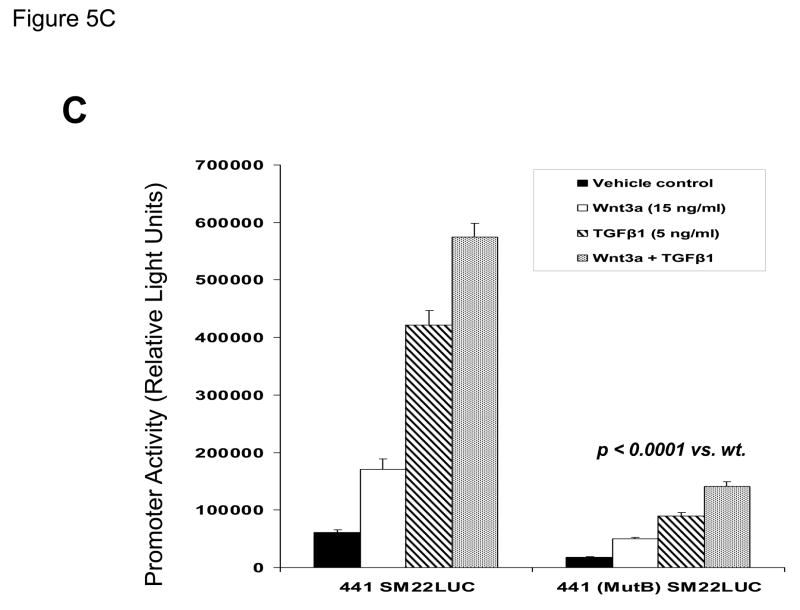

Figure 5. A CAGAG motif in the SM22α promoter region −203 to −199 assembles specific DNA-protein complexes that support basal and Wnt3a+TGFβ1 transcriptional responses.

Panel A, a radiolabeled synthetic duplex oligonucleotide of the SM22α promoter region −215 to −182 (Figure 4) was incubated with cell extracts from either vehicle, Wnt3a, TGFβ1, or Wnt3a + TGFβ1 C3H10T1/2 cultures (24 and 4 hour treatments as indicated). DNA-protein complexes were resolved by native gel electrophoresis. Five complexes are identified, one of which (complex 4) is increased by treatment with either Wnt3a (lanes 3, 8) or TGFβ1 (lanes 4, 9). All gel shift data presented are representative of results observed in 2 to 5 independent experiments. Panel B, cold competition assays using radiolabeled SM22α [−215/−182] and extracts from Wnt3a-treated C3H10T1/2 cells (20 hour treatment). See Figure 4 for mutant sequences. Panel C, the mutB alteration of the CAGAG element was introduced into the SM22α fragment −441 to +5, and the effects on basal and stimulated promoter activity evaluated. As compared to native 441 SM22LUC, 441 (mutB) SM22LUC exhibited >70% reduction in basal and stimulated activity.

To demonstrate the functional importance of the protein – DNA interactions assembled by this novel CAGAG element to SM22α promoter activity in C3H10T1/2 cells, we introduced the mutB sequence that disrupts the CAGAG element (Figure 4) into the native SM22α promoter context −441/+5, and then assessed effects on promoter regulation. As shown in Figure 5C, disruption of this element and the associated DNA-protein complexes significantly reduced basal and Wnt3a/TGFβ1 responses by > 70% (p < 0.0001 vs. wild-type promoter; compare activity of 441 (mutB) SM22LUC with that of 441 SM22LUC).

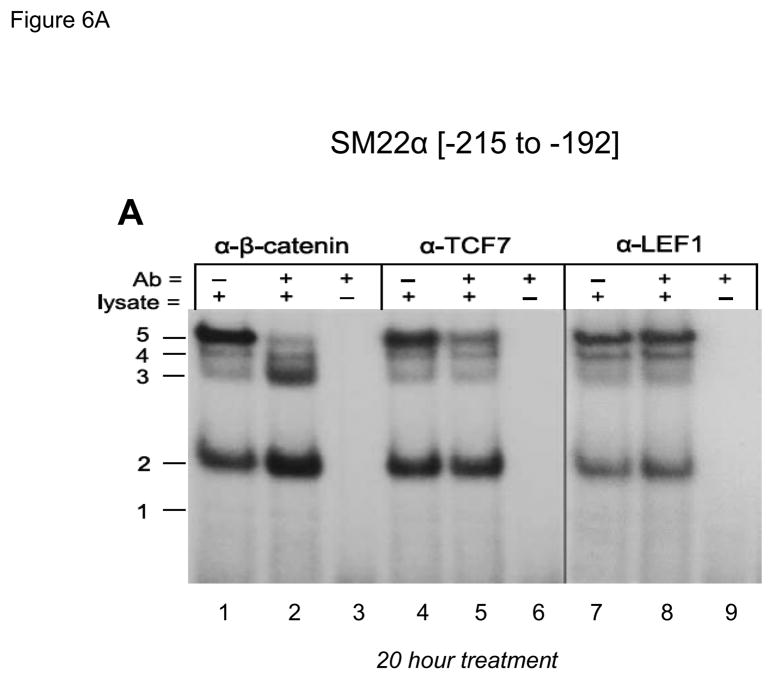

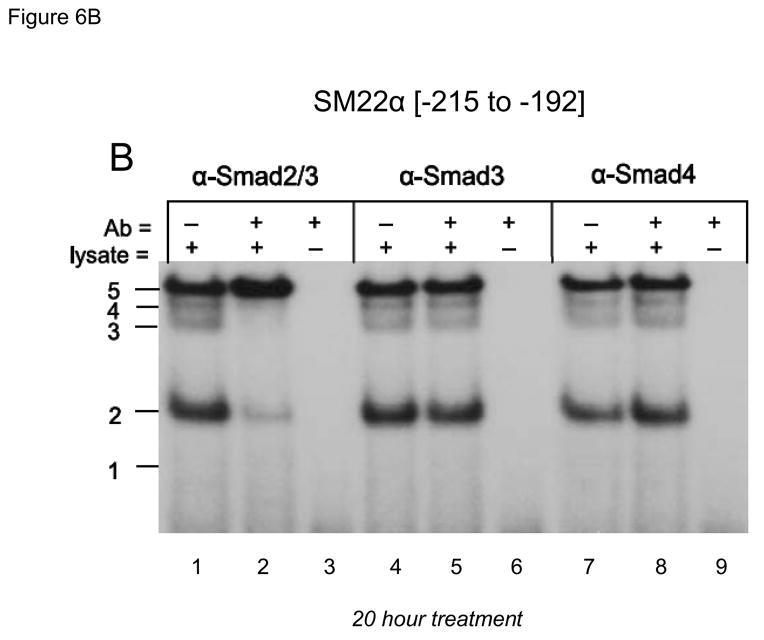

The CAGAG cognate required for protein-DNA complexes closely resembled the CAAAG and CAGA motifs necessary for TCF/β-catenin activation(13) and Smad binding (46), respectively. Therefore, we tested the ability of antibodies directed towards specific TCF, LEF (lymphoid enhancer-binding factor), Smad, and β-catenin proteins to perturb the DNA-protein complexes assembled by SM22[−215/−182]. As shown in Figure 6A, antibody to β-catenin disrupted complex 5 formation, but increased formation of complexes 2 and 3 (lane 1–3). Similar results were obtained with three other anti-β-catenin antibodies (data not shown). Like the β-catenin antibody, anti-TCF7 reduced formation of complex 5, but with little if any effect on the other complexes (Figure 6A, lanes 4–6). By contrast, anti-LEF1 antibody had no effect (Figure 6A, lanes 7–9). However, anti-Smad2/3 -- a reagent that recognizes full length Smad2(FL), Smad2Δexon3(46), and Smad3 -- inhibits formation of complexes 2, 3 and 4 (Figure 6B, lanes 1–3). The antibodies specific to Smad3 (Figure 6B, lanes 4–6) and Smad4 (Figure 6B, lanes 7–9) were without effect. All gel shift data presented are representative of results observed in 2 to 5 independent experiments (data not shown).

Figure 6. The CAGAG cognate in the SM22α promoter region −203 to −199 assembles complexes containing β-catenin, TCF7, and Smad2Δexon3.

Panel A, gel shift assays were carried out as in Figure 5B, using the indicated antibodies (Aby) to immunologically probe the protein-DNA complexes identified. Panel B, the α-Smad2/3 antibody that recognizes Smad2(FL), Smad2Δexon3, and Smad3 specifically inhibits formation of complexes 2–4 (lanes 1–2). However, antibodies specific for Smad3 (lanes 4–5) or Smad4 (7–8) did not have any effect. See Supplement Figures S1 and S2 for validation of Smad3 and Smad4 antibodies.

Because of the apparent absence of anti-Smad3 and anti-Smad4 antibody-sensitive complexes assembled by SM22[−215/−182] (Figure 6B, lanes 4 – 9) we wished to confirm the activity of the immunoreagents used in these gel shift assays. Therefore, we assessed the activities of these antibodies on complexes binding SM22[−18/+18], a fragment encompassing the developmentally important Smad3 binding element recently described(35, 43). Using either recombinant purified Smad fusion proteins or extracts obtained from TGFβ1-treated C3H10T1/2 cells, we validated activity of anti-Smad3 and anti-Smad4 antibodies (supplement, Figures S1 and S2). Thus, functionally important DNA-protein complexes containing β-catenin, TCF7, and Smad2 bind the CAGAG motif at nucleotides −203 to −199 in the SM22α promoter. Smad3- and Smad4-containing were not detected in the CAGAG DNA-protein binding complex assembled by SM22[−215/−182].

Dominant negative TCF (dnTCF) inhibits Wnt3a+TGFβ1 and Smad2Δexon3-augmented activation of transcription driven by SM22[−213/−192]-RSVLUC

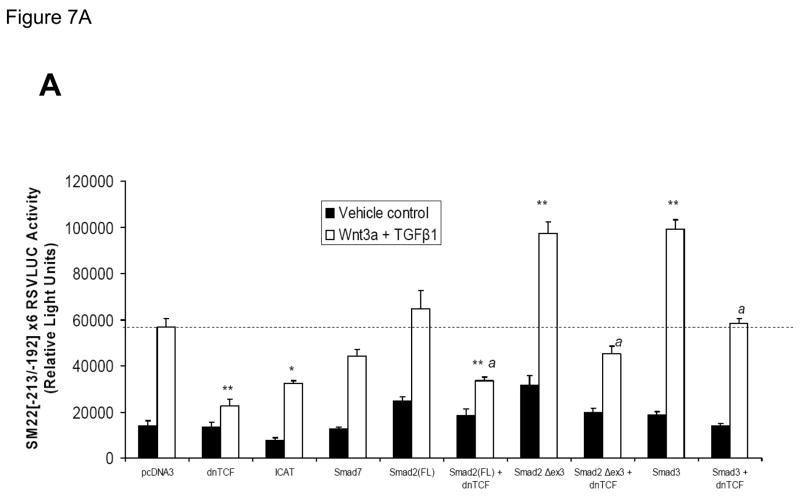

Transcription dependent upon β-catenin is directed to protein-DNA complexes via interactions with TCFs, a family of transcription regulators that bind DNA via conserved high mobility group domains(47). To provide further evidence that the complexes assembled by the SM22α promoter region −213 to −192 were dependent upon to β-catenin and TCF/LEF signaling, we examined the effect of co-expression of a commercially available dnTCF, dnTCF4/dnTCF7L2 (8), on Wnt3a+TGFβ1 activation of this novel regulatory element. As shown in Figure 7A, co-transfection of an eukaryotic expression construct encoding dnTCF significantly reduced Wnt3a+TGFβ1 induction of SM22[−213/−192]-RSVLUC by ca. 80% vs. the pcDNA3 control (p < 0.001, one way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s testing). Similarly, ICAT (inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF), an inhibitor of β-catenin activated transcription (8, 48), also significantly inhibited Wnt3a+TGFβ1 activation of this novel regulatory element. By contrast, Smad7 expression had modest if any effect. Smad2 exists in two isoforms, a full-length Smad2(FL) and as Smad2Δexon3 -- the latter arising from translation of an alternatively spliced transcript that lacks exon 3 sequences. Because of steric constraints, Smad2(FL) lacks intrinsic DNA binding activity, and the in vivo biological activity of the Smad2 locus is fully recapitulated by Smad2Δexon3(49). Therefore, we evaluated the effects of Smad2(FL) and Smad2Δexon3 expression on transcription driven by SM22[−213/−192], and the effect of dnTCF. Smad2(FL) co-expression had no significant effect on Wnt3a+TGFβ1 induction; however, co-expression of Smad2Δexon3 significantly augmented Wnt3a+TGFβ1 transcriptional activation of SM22[−213/−192]×6-RSVLUC [p < 0.001, Figure 7A]. Once again, dnTCF inhibited SM22[−213/−192]-RSVLUC activation by Smad2Δexon3 [Figure 7A]. Even though Smad3 was not detected in the cellular complexes assembled by SM22[−215/−182] [Figure 6B], similar inductive responses were observed by Smad3 coexpression, and were again inhibited by dnTCF [Figure 7A].

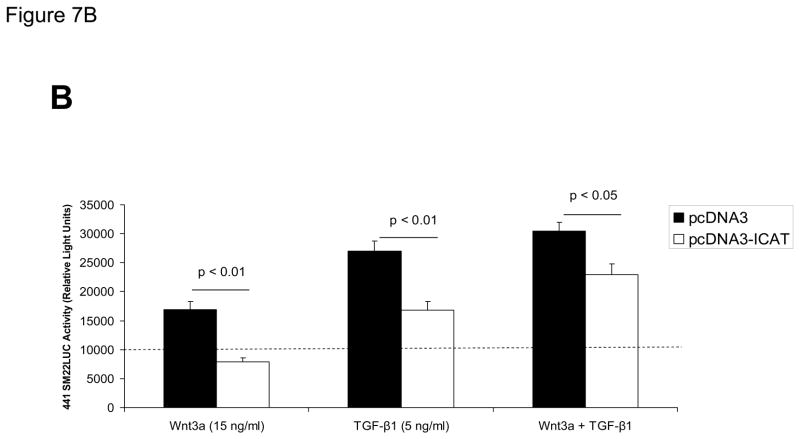

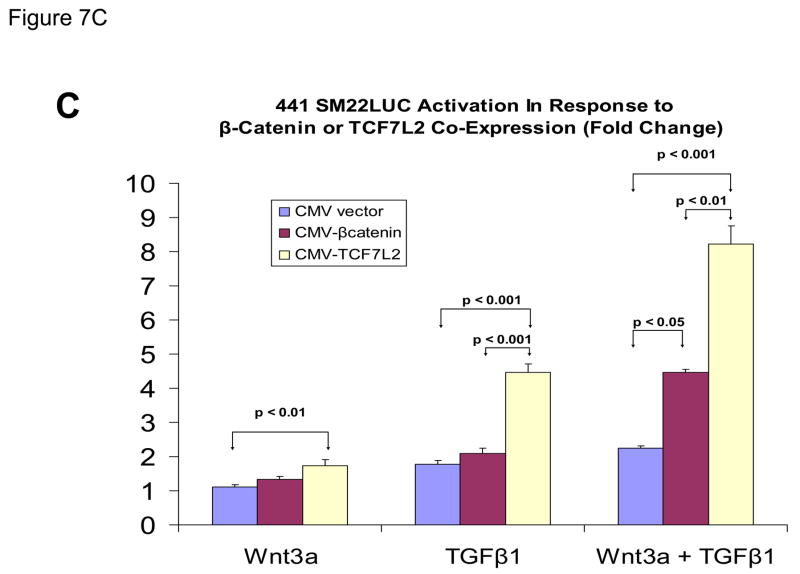

Figure 7. Intracellular antagonists and agonists of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulate transcriptional activation of SM22[−213/−192]-RSVLUC.

Panel A, expression plasmids for dominant negative TCF (dnTCF), ICAT, and Smad7 were co-transfected with SM22[−213/−192]×6-RSVLUC, and the impact on Wnt3a+TGFβ1 induction examined as done in Figure 3. Note Smad2Δexon3 and Smad3 significantly augmented Wnt3a+TGFβ1 stimulation, and that dnTCF expression consistently suppressed activation. See text for details. **, p < 0.001 vs. Wnt3a+TGFβ1 stimulated pcDNA3 control (dotted line), by post-hoc Tukey’s test following an ANOVA with p < 0.0001. *, p < 0.01 vs. Wnt3a+TGFβ1 stimulated pcDNA3 control. a, p < 0.001 vs. the corresponding Smad co-transfection that lacks dnTCF. Panel B, ICAT, the inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF, reduced Wnt3a and TGFβ1 induction of SM22α activity in the native promoter context of 441 SM22LUC. Panel C, 441 SM22LUC was upregulated by transient co-expression of either β-catenin or TCF7L2, the former observed in the presence of concomitant Wnt3a+TGFβ1 treatment.

Because ICAT expression appeared to affect primarily basal activity driven by the novel regulatory element in the heterologous promoter context of SM22[−213/−192]-RSVLUC without affecting “fold activation” [Figure 7A], we examined the impact of ICAT expression on 441 SM22LUC. Co-expression of ICAT suppressed induction of 441 SM22LUC, confirming the role of β-catenin in the transcriptional regulation of SM22α in native promoter context [Figure 7B]. Moreover, co-expression of either β-catenin or TCF7L2 enhanced 441 SM22LUC activity – but only in the presence of both Wnt3a + TGFβ1 treatment [Figure 7C]. Thus, transient co-expression studies confirm the functional importance of the Smad2Δexon3, TCF7, and β-catenin complexes identified in the regulation of SM22α gene transcription. While not detected in endogenous C3H10T1/2 cell binding complexes – due to low levels of endogenous expression(50) -- Smad3 is also capable of activating transcription via this novel regulatory motif.

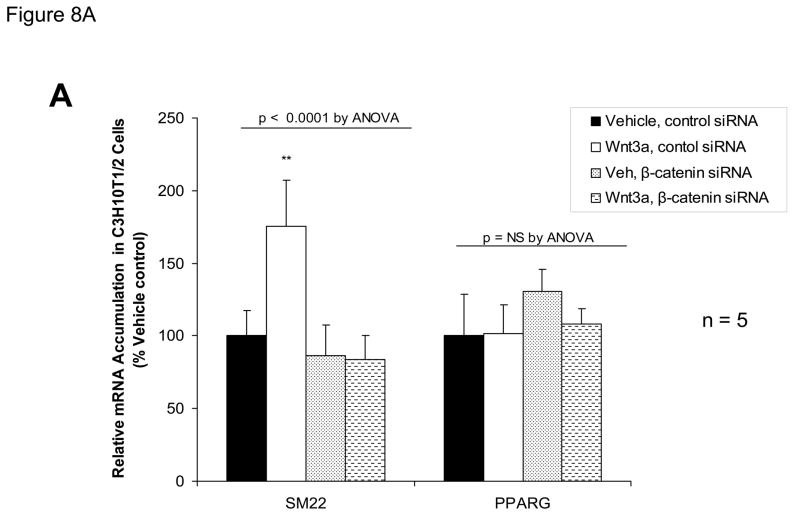

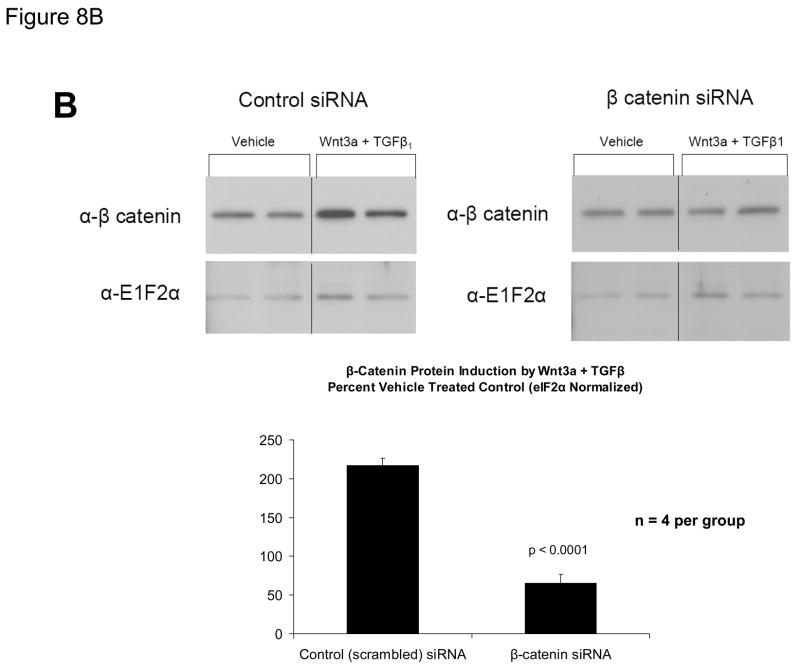

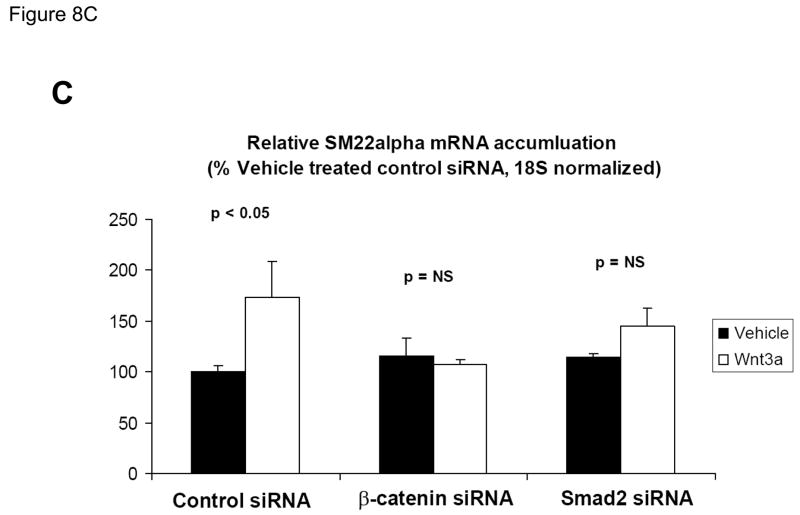

siRNA (small interfering RNA) directed to β-catenin inhibits upregulation of SM22α gene expression

ChIP assays (Figure 3C), immunologic probing of DNA-protein complexes assembled by SM22α promoter region −213/−192 (Figure 6A), and functional studies (Figure 7) indicated the contributions of β-catenin-dependent complexes to SM22α regulation. We wished to further confirm the functional importance of β-catenin signaling to Wnt3a-induced SM22α expression in native genomic context. Therefore, we examined the effect of RNAi - mediated inhibition of endogenous β-catenin induction on Wnt3a responses, using a siRNA directed towards β-catenin. As compared to expression observed following transfection of control siRNA, siRNA specific to β-catenin message completely prevented SM22α mRNA induction by Wnt3a in C3H10T1/2 cells, quantified by fluorescence RT-qPCR (Figure 8A); expression of SM22α in the presence of Wnt3a was significantly inhibited by β-catenin siRNA (p < 0.0001, from 5 independent transfections). By contract, β-catenin siRNA had no effect on PPARγ expression (p > 0.05, non-significant). Western blot followed by digital image analysis confirmed that β-catenin siRNA significantly diminished induction of β-catenin protein accumulation (Figure 8B). As observed with β-catenin siRNA, siRNA directed towards all forms of Smad2 also precluded significant Wnt3a induction of SM22α message (Figure 8C), extending and confirming our previous results (Figure 8A). Thus, β-catenin and Smad2 gene products mediate Wnt3a-dependent activation of the SM22α gene in C3H10T1/2 cells.

Figure 8. RNA interference directed towards β-catenin inhibits Wnt3a induction of SM22α gene expression.

Panel A, C3H10T1/2 cells were transfected either with control siRNA or a validated β-catenin siRNA as indicated, and then treated with either vehicle or 15 ng/ml Wnt3a for 24 hours. Total cellular RNA was extracted, and mRNA accumulation of SM22α and PPARγ quantified by RT-qPCR with normalization to 18S rRNA. Data are presented as the mean +/− error from five independent transfections and treatments was analyzed for each group. Note that siRNA to β-catenin inhibited Wnt3a induction of SM22α. **, p < 0.01 by post-hoc Tukey’s test from all other conditions. Panel B, western blot analysis confirmed that β-catenin siRNA impaired β-catenin protein induction in transfected C3H10T1/2 cells. Duplicate blots are shown, representative of the 4 independent blots analyzed by digital image analysis (separate gels indicated by the vertical black line). Data are derived from several independent gels run in parallel. Panel C, siRNA directed toward all Smad2 isoforms also inhibited induction of SM22α gene expression by Wnt3a.

DISCUSSION

The elaboration of SMC genes is controlled in a modular fashion; different regulatory elements for the same gene selectively activated for expression in specific myogenic subtypes in unique anatomic venues. Modules have been recently detailed for SM-MHC(34) and SMC α-actin(51). Likewise, the proximal SM22α promoter is capable of driving SMC gene expression in arterial, but not venous, vasculature(34, 52). Using DNAse I footprinting and transgenic reporters, Parmacek identified multiple smooth muscle cell elements (SME1 – SME6) within the proximal 0.44 kb promoter(53). Li mapped a novel SBE [Smad binding element] located at nucleotides +5 to +24 that conveys TGF-β/Smad3 dependent regulation of SM22α gene expression(35). Protein-protein interactions between myocardin and Smad3 participate in the activity of this element – but are completely independent of prototypic SRF-binding CArG box elements that also direct myocardin transactivation (19, 39). In our in vitro studies of SM22α regulation by Wnt3a, this exon 1 SBE cognate is not required [Figure 2, Figure 3]. However, the footprint for the Parmacek SM22α SME3 (53) corresponds to the Wnt3a-regulated response element.

We previously identified that paracrine Wnt signals mediate many of the procalcific actions of Msx2(14, 15). In the present work, we examined whether Wnt3a or Wnt5a – two key Wnt ligands upregulated by Msx2 in myofibroblasts – might regulate SM22α transcription as well, since Msx2 transduction increases SM22α expression in culture. We identified that Wnt3a increases this early myofibroblast marker. The additive interaction between Wnt3a and TGFβ1 was Wnt-selective; the non-canonical Wnt agonist Wnt5a (54) neither augmented nor antagonized TGFβ1 actions, and was ineffective as a stimulus for SM22α expression. Functional interactions between Wnt3a and TGFβ1 were gene – specific; the combination enhanced SM22α expression, while TGFβ1 abrogated Wnt3a induction of the osteochondrogenic Runx2 gene. Thus, vascular Wnt3a signaling (14, 15) can promote early features of the myofibroblast lineage in concert with TGFβ1.

The Smad2Δexon3 isoform we identify as recognizing the SM22αCAGAG element at −203 to −199 is widely expressed(46). The ratio of Smad2Δexon3 to Smad2(FL) ranges from 1:3 to 1:10 (46). The exon 3 domain of Smad2(FL) inhibits DNA binding by the N-terminal MH1 domain (46, 55). Thus, unlike Smad2Δexon3 and Smad3, Smad2(FL) does not exhibit intrinsic DNA binding (55, 56). Both Smad2Δexon3 and Smad3 – but not Smad2(FL) – restore embryonic viability and fertility to Smad2−/− mice(49). The specific for Smad2(FL) in mediating transcriptional responses during development is unknown.

β-Catenin is a transcriptional co-activator that lacks intrinsic DNA binding activity(13). Prototypic targets of β-catenin have emphasized elements recognized by members of the TCF/LEF family (13). However, β-catenin regulated Smad:TCF complexes have been recently reported(57) (58). Smad3 participates in a TCF4/TCF7L2: βcatenin - dependent complex that controls mesenchymal cell lineage allocation(57). These complexes form in the absence of Smad4, suggesting that “co-Smad” functions of Smad4 are provided by other constituents in the novel heterotrimer. Of note, although a single copy of the element is capable of conveying the Wnt3a response, multimerization is required to provide TGFβ1 regulation (data not shown). This likely reflects the need for multiple elements to integrate Wnt3a+ TGFβ1 signaling, as occurs in the native SM22α promoter context (supplement Figure S3) of 441 SM22LUC, and may explain the variability in the magnitude of SM22α mRNA induction observed in response to Wnt3a. Such combinatorial complexity may afford specificity and fine-tuning of gene expression and myofibroblast phenotypic modulation(58) in response to paracrine cues [supplement Figure S3]. Intriguingly, several elements similar to the cognate we mapped in SM22α are present in the SMCα-actin promoter -- including the extended “ATGCAGAG” motif (~ 1.4 kb upstream of transcription initiation). Whether any of these elements are functional cognates remains to be assessed.

Combinatorial complexity afforded by Wnt ligands is also apparent. Unlike Wnt3a, Wnt1 and Wnt5a did not upregulate SM22α. Because Wnt1 is the prototypic agonist for canonical Wnt signaling, we were surprised that Wnt1 did not also induce SM22α. However, even closely related members of the Wnt family differ remarkably in biological specificity(20, 59, 60). Wnt7a and Wnt7b share 77% identity at the amino acid level; however, while Wnt7b functions as an agonist of canonical and non-canonical signaling in most contexts, Wnt7a does not – highly dependent upon the specific Fzd (Frizzled) LRP co-receptor expressed (59, 60). We anticipate that the differences between Wnt1 and Wnt3a – proteins sharing 42% amino acid identity – must encode functionally important differences(14, 20). While normally expressed at low levels in quiescent myofibroblasts as compared to Wnt5a (supplement Figure S4), aortic Wnt3a is dramatically upregulated by diabetes and dyslipidemia (15). Inflammatory signals conveyed by TNFα mediate Wnt3a induction in aortic myofibroblasts (15) -- with evidence of “feed-forward” pathobiology via paracrine Msx2-Wnt3a signals (supplement Figure S4) (14). Vascular Dkk1 and SFRP likely play critical roles in restraining osteogenic Wnt signals in aortic disease processes(16).

During osteochondrogenic differentiation, Wnt3a simultaneously promotes osteogenic lineage allocation and proliferative expansion of early mesenchymal progenitors (9, 30, 61). In the injured adventitia, SM22α expression overlaps the proliferating, bromodeoxyuridine-labeled myofibroblasts of the adventitial-medial junction(36). We speculate that induction of adventitial myofibroblast SM22α expression in response to injury may be mediated in part by Wnt/β-catenin signaling – with concomitant allocation of adventitial progenitors to the early SMC lineage(62, 63). This notion has yet to be tested.

There are limitations to our study. Our analyses are carried out in the C3H10T1/2 culture cell system. The C3H10T1/2 multipotent mesenchymal progenitor does faithfully recapitulate many features of early mesenchymal cell differentiation, including myofibroblast differentiation in vitro (31, 32, 37, 41)and in vivo (31). Nevertheless, development of transgenic mouse promoter-reporter models will be necessary extend our ex vivo molecular studies to in vivo models of pericytic myofibroblast activation – and will integrate the other important paracrine cues provided by endothelial cells in addition to TGFβ1 (64). While mutation of the CAGAG [−203/−199] motif in the 0.44 kb SM22α promoter reduced Wnt3a+TGFβ1 induction by 70%, some residual activity remained. We speculate that the novel Smad2Δexon3 and TCF7 regulatory complex we have identified is functionally coupled by β-catenin to other SM22α DNA-protein complexes –elements that can only weakly support β-catenin activation in the absence of the cis -CAGAG box (supplement Figure S3). Regulatory elements located elsewhere in the SM22α promoter(43) likely amplify the Wnt3a signaling robustly specified by the CAGAG box. Whether myocardin (43, 65) and β-catenin cooperate or compete in SM22α promoter regulation is also unknown. Future studies will examine the functional relationships between complexes assembled at this novel element and other protein-DNA interactions (66, 67) that control vascular expression of SM22α during development and disease.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations used are: Aby, antibody; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; C3H10T1/2, murine multipotent mesenchymal cell line; dnTCF, dominant negative TCF; FBS, fetal bovine serum; HES, Hairy/enhancer of split homolog; ICAT, inhibitor of β-catenin and TCF; LacZ, bacterial β-galactosidase; LEF, lymphoid enhancer factor; LRP, LDL receptor related protein receptor; LUC, luciferase reporter gene; MEM, modified Eagle’s medium; MetS, metabolic syndrome; Msx, muscle segment homeobox gene; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PolII, RNA polymerase II; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SBE, Smad binding element; SFRP, secreted frizzled related protein; Smad2(FL), full-length Smad2 variant possessing exon 3; Smad2Δexon3, Smad2 variant lacking exon 3; siRNA, small interfering RNA; SM α-actin, smooth muscle actin Acta2; SM22α, 22 kDa transgelin; SME, smooth muscle cell element; SM-MHC, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, myh11; SRF, serum response factor; SMC, vascular smooth muscle cell; T2DM, type II diabetes mellitus; TCF, T-cell factor; TEF, transcriptional enhancer factor; Wnt, Wingless/int gene family; WT, wild-type sibling mouse; 18S, 18S ribosomal RNA.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL81138 to D.A.T., and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brohall G, Oden A, Fagerberg B. Carotid artery intima-media thickness in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2006;23:609–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collett GD, Canfield AE. Angiogenesis and pericytes in the initiation of ectopic calcification. Circ Res. 2005;96:930–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000163634.51301.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe IZ, Tintut Y, Newfell BG, Demer LL, Mendelsohn ME. Mineralocorticoid receptor activation promotes vascular cell calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:799–805. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258414.59393.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abedin M, Tintut Y, Demer LL. Mesenchymal stem cells and the artery wall. Circ Res. 2004;95:671–6. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000143421.27684.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz R, Wong ND, Kronmal R, et al. Features of the metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus as predictors of aortic valve calcification in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2006;113:2113–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.598086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozes G, Keresztury G, Kadar A, et al. Atherosclerosis in amputated legs of patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Int Angiol. 1998;17:282–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guzman RJ, Brinkley DM, Schumacher PM, Donahue RM, Beavers H, Qin X. Tibial artery calcification as a marker of amputation risk in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1967–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quasnichka H, Slater SC, Beeching CA, Boehm M, Sala-Newby GB, George SJ. Regulation of smooth muscle cell proliferation by beta-catenin/T-cell factor signaling involves modulation of cyclin D1 and p21 expression. Circ Res. 2006;99:1329–37. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253533.65446.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirton JP, Crofts NJ, George SJ, Brennan K, Canfield AE. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling stimulates chondrogenic and inhibits adipogenic differentiation of pericytes: potential relevance to vascular disease? Circ Res. 2007;101:581–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shao JS, Cai J, Towler DA. Molecular mechanisms of vascular calcification: lessons learned from the aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1423–30. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000220441.42041.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalajzic Z, Li H, Wang LP, et al. Use of an alpha-smooth muscle actin GFP reporter to identify an osteoprogenitor population. Bone. 2008;43:501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalajzic I, Kalajzic Z, Wang L, et al. Pericyte/myofibroblast phenotype of osteoprogenitor cell. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2007;7:320–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoppler S, Kavanagh CL. Wnt signalling: variety at the core. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:385–93. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao JS, Cheng SL, Pingsterhaus JM, Charlton-Kachigian N, Loewy AP, Towler DA. Msx2 promotes cardiovascular calcification by activating paracrine Wnt signals. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1210–20. doi: 10.1172/JCI24140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Aly Z, Shao JS, Lai CF, et al. Aortic Msx2-Wnt calcification cascade is regulated by TNF-alpha-dependent signals in diabetic Ldlr−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2589–96. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodwin AM, Sullivan KM, D’Amore PA. Cultured endothelial cells display endogenous activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and express multiple ligands, receptors, and secreted modulators of Wnt signaling. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:3110–20. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satokata I, Ma L, Ohshima H, et al. Msx2 deficiency in mice causes pleiotropic defects in bone growth and ectodermal organ formation. Nat Genet. 2000;24:391–5. doi: 10.1038/74231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng SL, Shao JS, Charlton-Kachigian N, Loewy AP, Towler DA. MSX2 promotes osteogenesis and suppresses adipogenic differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal progenitors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45969–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306972200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi K, Nakamura S, Nishida W, Sobue K. Bone morphogenetic protein-induced MSX1 and MSX2 inhibit myocardin-dependent smooth muscle gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:9456–70. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng SL, Shao JS, Cai J, Sierra OL, Towler DA. Msx2 exerts bone anabolism via canonical Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20505–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800851200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai CF, Seshadri V, Huang K, et al. An osteopontin-NADPH oxidase signaling cascade promotes pro-matrix metalloproteinase 9 activation in aortic mesenchymal cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:1479–89. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227550.00426.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bidder M, Shao JS, Charlton-Kachigian N, Loewy AP, Semenkovich CF, Towler DA. Osteopontin transcription in aortic vascular smooth muscle cells is controlled by glucose-regulated upstream stimulatory factor and activator protein-1 activities. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44485–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newberry EP, Latifi T, Battaile JT, Towler DA. Structure-function analysis of Msx2-mediated transcriptional suppression. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10451–62. doi: 10.1021/bi971008x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sierra OL, Cheng SL, Loewy AP, Charlton-Kachigian N, Towler DA. MINT, the Msx2 interacting nuclear matrix target, enhances Runx2-dependent activation of the osteocalcin fibroblast growth factor response element. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:32913–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Towler DA, Bennett CD, Rodan GA. Activity of the rat osteocalcin basal promoter in osteoblastic cells is dependent upon homeodomain and CP1 binding motifs. Mol Endocrinol. 1994;8:614–24. doi: 10.1210/mend.8.5.7914673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K. Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:179–85. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Sova P, Bomsztyk K. Fast chromatin immunoprecipitation assay. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e2. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solway J, Seltzer J, Samaha FF, et al. Structure and expression of a smooth muscle cell-specific gene, SM22 alpha. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13460–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Miano JM, Cserjesi P, Olson EN. SM22 alpha, a marker of adult smooth muscle, is expressed in multiple myogenic lineages during embryogenesis. Circ Res. 1996;78:188–95. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caverzasio J, Manen D. Essential role of Wnt3a-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 for the stimulation of alkaline phosphatase activity and matrix mineralization in C3H10T1/2 mesenchymal cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5323–30. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D’Amore PA. PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:805–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kale S, Hanai J, Chan B, et al. Microarray analysis of in vitro pericyte differentiation reveals an angiogenic program of gene expression. Faseb J. 2005;19:270–1. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1604fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Hinz B, Chaponnier C, Brown RA. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:349–63. doi: 10.1038/nrm809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida T, Owens GK. Molecular determinants of vascular smooth muscle cell diversity. Circ Res. 2005;96:280–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000155951.62152.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qiu P, Feng XH, Li L. Interaction of Smad3 and SRF-associated complex mediates TGF-beta1 signals to regulate SM22 transcription during myofibroblast differentiation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2003;35:1407–20. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faggin E, Puato M, Zardo L, et al. Smooth muscle-specific SM22 protein is expressed in the adventitial cells of balloon-injured rabbit carotid artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:1393–404. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.6.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kennard S, Liu H, Lilly B. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF- 1) down-regulates Notch3 in fibroblasts to promote smooth muscle gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1324–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiu P, Ritchie RP, Gong XQ, Hamamori Y, Li L. Dynamic changes in chromatin acetylation and the expression of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases regulate the SM22alpha transcription in response to Smad3-mediated TGFbeta1 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348:351–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owens GK, Kumar MS, Wamhoff BR. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:767–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunelli S, Cossu G. A role for MSX2 and necdin in smooth muscle differentiation of mesoangioblasts and other mesoderm progenitor cells. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:96–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ding R, Darland DC, Parmacek MS, D’Amore PA. Endothelial-mesenchymal interactions in vitro reveal molecular mechanisms of smooth muscle/pericyte differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2004;13:509–20. doi: 10.1089/scd.2004.13.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaur T, Lengner CJ, Hovhannisyan H, et al. Canonical WNT signaling promotes osteogenesis by directly stimulating Runx2 gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33132–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500608200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qiu P, Ritchie RP, Fu Z, et al. Myocardin enhances Smad3-mediated transforming growth factor-beta1 signaling in a CArG box-independent manner: Smad-binding element is an important cis element for SM22alpha transcription in vivo. Circ Res. 2005;97:983–91. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000190604.90049.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y, Budd RC, Kelm RJ, Jr, Sobel BE, Schneider DJ. Augmentation of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells by plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1777–83. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000227514.50065.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross S, Cheung E, Petrakis TG, Howell M, Kraus WL, Hill CS. Smads orchestrate specific histone modifications and chromatin remodeling to activate transcription. Embo J. 2006;25:4490–502. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Massague J, Seoane J, Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2783–810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clevers H, van de Wetering M. TCF/LEF factor earn their wings. Trends Genet. 1997;13:485–9. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tago K, Nakamura T, Nishita M, et al. Inhibition of Wnt signaling by ICAT, a novel beta-catenin-interacting protein. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1741–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn NR, Koonce CH, Anderson DC, Islam A, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ. Mice exclusively expressing the short isoform of Smad2 develop normally and are viable and fertile. Genes Dev. 2005;19:152–63. doi: 10.1101/gad.1243205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaps C, Hoffmann A, Zilberman Y, et al. Distinct roles of BMP receptors Type IA and IB in osteo-/chondrogenic differentiation in mesenchymal progenitors (C3H10T1/2) Biofactors. 2004;20:71–84. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gan Q, Yoshida T, Li J, Owens GK. Smooth muscle cells and myofibroblasts use distinct transcriptional mechanisms for smooth muscle alpha-actin expression. Circ Res. 2007;101:883–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.154831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu R, Ho YS, Ritchie RP, Li L. Human SM22 alpha BAC encompasses regulatory sequences for expression in vascular and visceral smooth muscles at fetal and adult stages. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1398–407. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00737.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim S, Ip HS, Lu MM, Clendenin C, Parmacek MS. A serum response factor-dependent transcriptional regulatory program identifies distinct smooth muscle cell sublineages. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2266–78. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oishi I, Suzuki H, Onishi N, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase Ror2 is involved in non-canonical Wnt5a/JNK signalling pathway. Genes Cells. 2003;8:645–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2003.00662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dennler S, Huet S, Gauthier JM. A short amino-acid sequence in MH1 domain is responsible for functional differences between Smad2 and Smad3. Oncogene. 1999;18:1643–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yagi K, Goto D, Hamamoto T, Takenoshita S, Kato M, Miyazono K. Alternatively spliced variant of Smad2 lacking exon 3. Comparison with wild-type Smad2 and Smad3. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:703–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo W, Flanagan J, Jasuja R, Kirkland J, Jiang L, Bhasin S. The Effects of Myostatin on Adipogenic Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Are Mediated through Cross-communication between Smad3 and Wnt/{beta}-Catenin Signaling Pathways. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9136–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708968200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caraci F, Gili E, Calafiore M, et al. TGF-beta1 targets the GSK-3beta/beta-catenin pathway via ERK activation in the transition of human lung fibroblasts into myofibroblasts. Pharmacol Res. 2008;57:274–82. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Carmon KS, Loose DS. Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 regulates two wnt7a signaling pathways and inhibits proliferation in endometrial cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2008;6:1017–28. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-08-0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caricasole A, Ferraro T, Iacovelli L, et al. Functional characterization of WNT7A signaling in PC12 cells: interaction with A FZD5 × LRP6 receptor complex and modulation by Dickkopf proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37024–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou H, Mak W, Zheng Y, Dunstan CR, Seibel MJ. Osteoblasts directly control lineage commitment of mesenchymal progenitor cells through Wnt signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1936–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Torsney E, Hu Y, Xu Q. Adventitial progenitor cells contribute to arteriosclerosis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:64–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoshino A, Chiba H, Nagai K, Ishii G, Ochiai A. Human vascular adventitial fibroblasts contain mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;368:305–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bostrom K, Zebboudj AF, Yao Y, Lin TS, Torres A. Matrix GLA protein stimulates VEGF expression through increased transforming growth factor-beta1 activity in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52904–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parmacek MS. Myocardin-related transcription factors: critical coactivators regulating cardiovascular development and adaptation. Circ Res. 2007;100:633–44. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259563.61091.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoshida T, Kaestner KH, Owens GK. Conditional deletion of Kruppel-like factor 4 delays downregulation of smooth muscle cell differentiation markers but accelerates neointimal formation following vascular injury. Circ Res. 2008;102:1548–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Y, Sinha S, Owens G. A transforming growth factor-beta control element required for SM alpha-actin expression in vivo also partially mediates GKLF-dependent transcriptional repression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48004–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301902200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.