Abstract

Background

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) is a risk factor for atrial fibrillation (AF), but the atrial cellular electrophysiological mechanisms in humans are unclear.

Objective

To investigate whether LVSD in patients who are in sinus rhythm (SR) is associated with atrial cellular electrophysiological changes which could predispose to AF.

Methods

Right atrial myocytes were obtained from 214 consenting patients in SR who were undergoing cardiac surgery. Action potentials or ion currents were measured using the whole-cell-patch clamp technique.

Results

The presence of moderate or severe LVSD was associated with a shortened atrial cellular effective refractory period, ERP (209±8 ms; 52 cells, 18 patients vs 233±7 ms; 134 cells, 49 patients; P<0.05); confirmed by multiple linear regression analysis. The LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was markedly lower in patients with moderate or severe LVSD (36±4%, n=15) than in those without LVSD (62±2%, n=31; P<0.05). In cells from patients with LVEF≤45%, the ERP and action potential duration at 90% repolarisation were shorter than in those from patients with LVEF>45%, by 24 and 18%, respectively. The LVEF and ERP were positively correlated (r=0.65, P<0.05). The L-type calcium ion current, inward rectifier potassium ion current, and sustained outward ion current was unaffected by LVSD. The transient outward potassium ion current was decreased by 34%, with a positive shift in its activation voltage, and no change in its decay kinetics.

Conclusion

LVSD in patients in SR is independently associated with a shortening of the atrial cellular ERP, which may be expected to contribute to a predisposition to AF.

Keywords: Human, Left ventricular systolic dysfunction, Ejection fraction, Sinus rhythm, Atrial fibrillation, Electrophysiological remodelling, Isolated myocyte, Effective refractory period, Action potential duration, Ion current

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and congestive heart failure (CHF) frequently co-exist, and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) may increase AF risk.1 The mechanisms of this predisposition to AF likely involve interacting adaptational changes, or remodelling, of atrial structure and electrical, mechanical, metabolic and neurohumoral activities. AF generation and maintenance may each involve atrial reentrant and non-reentrant electrical activity. Reentry is promoted by a shortening of the wavelength, due to a reduction in either the effective refractory period (ERP), conduction velocity, or both. Atrial cellular electrical remodelling in patients with persistent AF features a shortening of the ERP, which is considered to facilitate reentry in these patients.2 It is conceivable that, in patients who are in sinus rhythm (SR), a predisposition to AF in those with LVSD might involve an associated reduction in the atrial cellular ERP. However, the available data are scarce and conflicting, and often compounded by variability in patients’ disease states and drug treatments.3 In atrial cells isolated from patients with CHF, the action potential duration at 90% repolarisation (APD90), an important determinant of ERP, was either increased,4 unchanged5,6 or, when recorded at relatively high stimulation rate, shortened.5 A shortening,6 or no change,4 in atrial cell APD50 were also reported. However, the ERP has not been measured in atrial cells from patients with CHF or LVSD,3 and also remains to be correlated with the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), an important index of LVSD and predictor of AF.7 Furthermore, the pattern of ionic remodelling in CHF or LVSD in human atrium also is presently unclear.3 For example, the L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) was either decreased8,9 or unchanged,5,10 with either slowed5 or unchanged8 kinetics, and had either an increased9 or decreased8,10 response to β-adrenergic stimulation. Studies of human atrial K+ currents have shown increased transient outward current (ITO), with no change in its voltage-dependence or decay, but with enhanced reactivation;6 a decreased inward rectifier (IK1);4 and an unchanged ultra-rapid delayed rectifier.6

The aims of this study, therefore, were two-fold. First, to investigate whether LVSD and reduced LVEF in patients who were in SR and undergoing cardiac surgery correlate with a shortening of atrial cellular ERP, which could contribute to a predisposition to AF. Second, to clarify the pattern of any accompanying ionic remodelling, by comparing various ion currents and their voltage- and time-dependent characteristics between patients with and without LVSD.

Methods

Right atrial appendage tissue was obtained from 214 consenting patients who were in SR and undergoing cardiac surgery. Procedures were approved by the institutional research ethics committee. Atrial cells were isolated as described previously.2 Action potentials and ion currents were recorded using the whole-cell-patch clamp technique. Cells were superfused at 35-37°C with a physiological solution containing (mM): NaCl (130), KCl (4), CaCl2 (2), MgCl2 (1), glucose (10) and HEPES (10); pH 7.4, with Cd2+ (0.2 mM) added for some cells, to block ICaL when recording K+ currents. Either the perforated or conventional ruptured patch configuration was used. The proportion of cells in which the perforated patch was used (64%) was not different between the groups under comparison. The constituents of the pipette solutions used for the different types of recordings are as detailed previously.11 Action potentials were stimulated with 5 ms current pulses of 1.2x threshold, at 75 beats/min (bpm) while injecting a small, constant current (set at the start of threshold measurement to clamp the maximum diastolic potential (MDP) to -80 mV, 1-2 min after attaining whole-cell).2,11-13 The cellular ERP was then measured using a standard S1-S2 protocol. Ion currents were recorded by voltage-clamping. IK1 was stimulated with linear voltage ramps from -120-+50 mV at 24 mV/s, or with 500 ms pulses (0.2 Hz) increasing from -120-+50 mV in 10 mV steps, from a holding potential (HP) of -50 mV. ITO and the sustained outward current, ISUS, were stimulated with 100 ms pulses (0.33 Hz), from -40-+60 mV, from a -50 mV HP. ISUS was measured as end-pulse current, and ITO as peak outward minus end-pulse current. ICaL was stimulated with 250 ms pulses (0.33 Hz), from -30-+60 mV, from an HP of -40 mV.

Details of each patient’s clinical characteristics and drug treatments were obtained from the medical records, post-surgery. All patients were in SR on the day of surgery, confirmed from a pre-surgery 12 lead ECG. An ECG was also available for the preceding day in 206 of 214 patients, and all confirmed SR. Patients were excluded if they had a documented episode of AF at any time pre-surgery, if they were taking digoxin or a non-β1-selective β-blocker, or if their β1-blocker-treatment had started later than 7 days pre-surgery. Each patient was designated as having either “no LVSD”, “mild LVSD”, “moderate LVSD” or “severe LVSD”, from qualitative reports of assessments in the patient’s case record. The LVEF was obtained, in a subset of 58 patients, from either echocardiography (52%), radionuclide ventriculography (26%) or contrast ventriculography (22%).

Statistical methods

Univariate measurements were compared between pairs of various subgroups of patients using 2-sided, 2-sample unpaired Student’s t-tests. Categorical data were compared using a χ2-test. All univariate electrophysiological data are expressed as cell means±1 standard error (SE), unless otherwise stated. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to further investigate relationships between the presence of LVSD and various electrophysiological measures, adjusted in a mixed effects linear model with the subject as a random effect, according to 10 covariates. Analyses were performed retrospectively, using “SAS PROC MIXED” in SAS 9.1.3 software (SAS Inst, USA). The group of patients with moderate or severe LVSD (19% of total) was used for statistical comparisons of cellular electrophysiology against patients with no LVSD whenever patient n permitted and unless otherwise stated, to maximise analysis sensitivity. All available information was incorporated. Therefore, the tables and statistical models are sometimes based on different numbers of subjects, reflecting some missing data for some covariates. P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

The patients’ clinical characteristics and drug treatments are shown in Table 1. The majority (91%) suffered from angina and underwent CABG surgery. Valve surgery (AVR or MVR) was performed with or without CABG in 15% of patients. 36% of patients had mild, moderate or severe LVSD, and 19% had moderate or severe LVSD. The majority of patients with LVSD had a history of MI and were taking an ACEI or ARB.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

| LVSD none | LVSD any | LVSD mod/sev | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Patient details | ||||||

| Total | 138 | - | 76 | - | 40 | - |

| Male | 97 | 70 | 62 | 82 | 33 | 83 |

| Age (years) | 63±1 | - | 62±1 | - | 63±2 | - |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 63±1 | - | 64±2 | - | 64±2 | - |

| Drug | ||||||

| Beta1-blocker | 90 | 65 | 52 | 68 | 28 | 70 |

| ACEI or ARB | 63 | 46 | 51 | 67* | 29 | 73* |

| CCB | 58 | 42 | 27 | 36 | 14 | 35 |

| Statin | 111 | 80 | 66 | 87 | 33 | 83 |

| Disease | ||||||

| Angina | 124 | 90 | 70 | 92 | 36 | 90 |

| History of MI | 38 | 28 | 51 | 67* | 31 | 78* |

| History of HT | 81 | 59 | 38 | 50 | 18 | 45 |

| Diabetes | 14 | 10 | 13 | 17 | 7 | 18 |

| Operation | ||||||

| CABG only | 114 | 83 | 66 | 87 | 34 | 85 |

| AVR only | 11 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 4 | 10 |

| CABG + AVR | 8 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| MVR only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| CABG + MVR | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ASDR only | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VSDR only | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Values are numbers of patients (n, and % of total) with selected clinical characteristics, except for age and heart rate (means±SE), in groups of patients with and without LVSD. “Any”=mild, moderate or severe. ACEI=angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor. ARB=angiotensin receptor blocker. CCB=calcium channel blocker. MI=myocardial infarction. HT=hypertension. CABG=coronary artery bypass graft surgery. AVR=aortic valve replacement. MVR=mitral valve replacement. ASDR=atrial septal defect repair. VSDR=ventricular septal defect repair.

P<0.05 vs LVSD none.

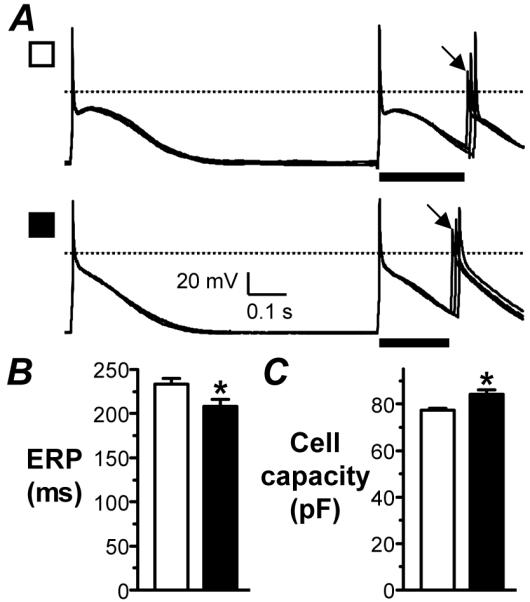

Changes in atrial cellular ERP and capacity associated with LVSD

Atrial cells from patients with moderate or severe LVSD had a significantly shorter ERP than those from patients without LVSD (Figure 1A). The resting potential (Vm) before current-clamp was similar in patients with moderate or severe LVSD to no LVSD (-20±2 vs -17±1 mV, P>0.05). During current-clamp, the holding current and MDP (taken during ERP-recording) also were similar between these groups (0.72±0.05 vs 0.68±0.03 pA/pF, and -82±1 vs -81±0 mV, respectively; P>0.05 for each). There were no significant differences in other action potential measurements. In a sub-group of 37 patients for whom left atrial (LA) size was available, the LA was larger in patients with LVSD (4.4±0.2 cm, n=7) than in those without (3.8±0.1 cm, n=30; P<0.05). The ERP was similar in cells from patients with LA size≤ 4 cm (clinically recognised as normal14), at 245±22 ms, to those with LA>4 cm, at 256±36 ms (P>0.05), and there was no significant correlation between LA size and ERP (P>0.05). The right atrial (RA) size was not available, though RA cell capacity was increased in LVSD (Figure 1C). The incidence of chronic β1-blocker use (which is associated with ERP-prolongation11,12) in patients from whom ERP was recorded, was 67% in those with moderate or severe LVSD vs 59% in those without LVSD (P>0.05). ERP-shortening associated with LVSD was maintained when patients were sub-analysed by chronic β1-blockade. In non-β-blocked patients, ERP was 179±13 ms in 27 cells from 8 patients with mild, moderate or severe LVSD vs 212±9 ms in 47 cells from 20 patients with no LVSD (P<0.05). Furthermore, in patients who underwent CABG-only (excludes all AVR, MVR, ASDR & VSDR), the magnitude of change in ERP and capacity associated with moderate or severe LVSD was largely maintained: ERP=213±10 vs 241±8 ms, P>0.05 (0.053); capacity=85±2 vs 77±1 pF, P<0.05). Finally, ERP-shortening associated with LVSD was confirmed by multiple linear regression analysis, adjusting for 10 covariates considered to be of particular importance (Table 2).

Figure 1. Change in ERP and capacity of atrial cells from patients with LVSD.

A. Representative, superimposed action potentials stimulated by the 7th and 8th of a train of current pulses, S1, followed by responses to a premature, S2, in a cell from a patient with no LVSD (upper trace) and moderate/severe LVSD (lower). ERP (bar)=longest S1-S2 which failed ( ) to produce an S2 response of amplitude>80% of S1. Mean±SE ERP (B) and capacity (C) of cells from patients with no LVSD (□; n=134 cells, 49 patients for ERP, and 535 cells, 135 patients for capacity) and moderate/severe LVSD (■; n=52 cells, 18 patients for ERP, and 152 cells, 38 patients for capacity). *=P<0.05 vs □.

) to produce an S2 response of amplitude>80% of S1. Mean±SE ERP (B) and capacity (C) of cells from patients with no LVSD (□; n=134 cells, 49 patients for ERP, and 535 cells, 135 patients for capacity) and moderate/severe LVSD (■; n=52 cells, 18 patients for ERP, and 152 cells, 38 patients for capacity). *=P<0.05 vs □.

Table 2. Multiple linear regression analysis of atrial cellular electrophysiology.

| EP variable | Patient n | Estimated change in EP with LVSD mod/sev | 95% confidence interval | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVSD none | LVSD mod /sev | ||||

| ERP | 49 | 18 | -26 ms | -49--3 | 0.027 |

| APD90 | 54 | 21 | -20 ms | -49-+9 | 0.17 |

| APD50 | 54 | 21 | +4 ms | -5-+13 | 0.36 |

| dV/dtmax | 54 | 21 | +4 V/s | -20-+28 | 0.76 |

| ITO | 40 | 6 | -3.2 pA/pF | -7.5-+1.0 | 0.14 |

| ITO Vact50 | 39 | 5 | +5 mV | -2-+13 | 0.15 |

| ICaL | 73 | 19 | -0.1 pA/pF | -1.6-+1.5 | 0.92 |

| IK1 | 40 | 10 | +0.4 pA/pF | -0.9-+1.7 | 0.57 |

| Capacity | 135 | 38 | +6 pF | -1-+13 | 0.074 |

Estimated changes in electrophysiological (EP) variables associated with LVSD, adjusting for the covariates: age, sex, β-blocker-treatment, ACEI/ARB-treatment, CCB-treatment, history of MI, history of HT, valve replacement surgery, diabetes, and heart rate.

Correlation between LVEF and atrial cellular electrophysiology

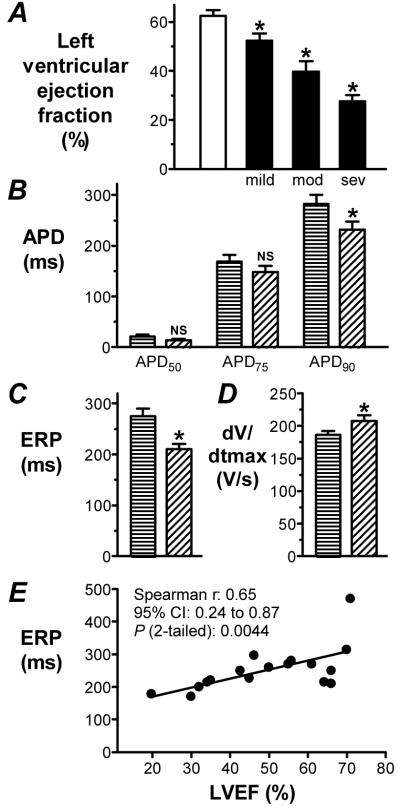

Within the sub-group of 58 patients whose LVEF was available, the qualitative assessment of increasing severity of LVSD was associated with a progressive and significant reduction in LVEF, compared with that recorded in patients without LVSD (Figure 2A). In patients with LVEF≤ 45% (a clinically accepted threshold for LVSD14), the APD90, but not APD75 or APD50, was significantly shorter than in patients with LVEF>45%, by 18% (Figure 2B), and the ERP was significantly shorter, by 24% (Figure 2C). Furthermore, the action potential maximum upstroke velocity (dV/dtmax) was significantly greater in patients with LVEF≤ 45%, by 11%, than in patients with LVEF>45% (Figure 2D). The holding current was similar between these groups (0.67±0.06 vs 0.60±0.04 pA/pF, P>0.05), and there were no significant differences in other action potential measurements. There was a significant correlation (Spearman rank correlation test) between patients’ atrial cellular ERP and LVEF, with ERP shortening with decreasing LVEF (Figure 2E). However, there was no significant correlation between dV/dtmax and LVEF with this test (P>0.05). There was also no correlation between LVEF and holding current (P>0.05), nor between ERP and dV/dtmax (P>0.05, n=49 cells).

Figure 2. Associations and correlations between LVEF, LVSD and atrial cellular electrophysiology.

A. Mean±SE LVEF in patients with no LVSD (□; n=31) vs mild (n=12), moderate (n=11) and severe (n=4) LVSD (■). Comparison of APD at 50, 75 and 90% repolarisation (B), ERP (C) and dV/dtmax (D) between patients with LVEF>45% (horizontal stripes; n=27-38 cells, 10-13 patients) and ≤45% (diagonal stripes; n=22-26 cells, 7-8 patients). *=P<0.05; NS=not significant, vs LVEF>45%. E. Correlation between LVEF and ERP. Points are means of cell data from individual patients (n=49 cells, 17 patients).

Changes in atrial K+ currents associated with LVSD

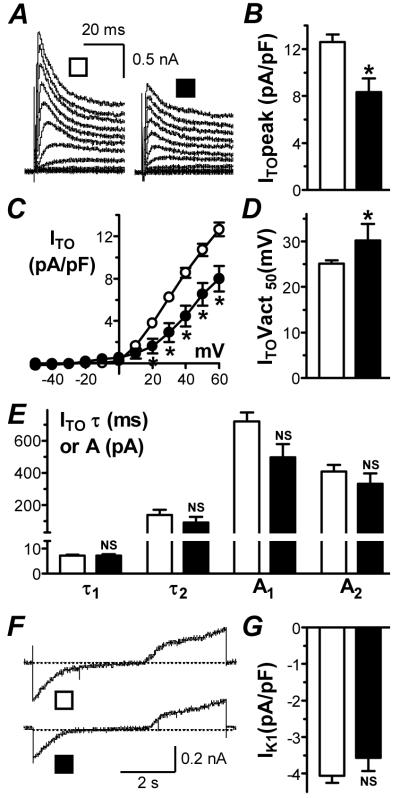

Atrial cells from patients with LVSD had a significantly lower peak ITO density (at +60 mV) than patients without LVSD, by 34% (Figure 3A&B). This reduction was maintained when patients were sub-analysed by chronic β1-blockade (itself associated with ITO-decrease12). In β1-blocked patients, ITO was 7.4±1.0 pA/pF in 15 cells from 9 patients with LVSD of any designation vs 10.0±0.6 pA/pF in 38 cells from 23 patients with no LVSD (P<0.05). LVSD was associated with significant ITO-reduction at all voltages between +20 and +60 mV (Figure 3C). Furthermore, the voltage of half-maximal activation (Vact50), assessed from Boltzmann relations, was significantly more positive, by 5 mV, in patients with LVSD (Figure 3D). The-time course of ITO inactivation was bi-exponential. There was no significant difference in the time constant (τ) or amplitude (A) of either phase of inactivation, measured at +60 mV, between patients with and without LVSD (Figure 3E). Peak ISUS was similar in cells from patients with LVSD (9.1±1.3 pA/pF; n=15 cells, 8 patients) to those without (10.3±0.6 pA/pF; n=72 cells, 31 patients, P>0.05). Peak IK1 was not significantly different between patients with and without LVSD (Figure 3F&G). This pattern of K+ current changes was maintained in the sub-group of CABG-only patients: ITO=8.3±1.2 vs 12.7±0.7 pA/pF, P<0.05; Vact50=30±4 vs 25±1 mV, P<0.05; with ISUS and IK1 again unaltered (P>0.05).

Figure 3. Changes in atrial K+ currents associated with LVSD.

ITO recordings (A), peak density (B), current-voltage relationships (C), Vact50 (D) and decay kinetics (E) in no LVSD (□; n=72-81 cells, 38-40 patients) and moderate/severe LVSD (■; n=11-12 cells, 5-6 patients). IK1 recordings (F) and density at -120 mV (G) in no LVSD (□; n=99 cells, 40 patients) and moderate/severe LVSD (■; n=20 cells, 10 patients).

Atrial ICaL characteristics associated with LVSD

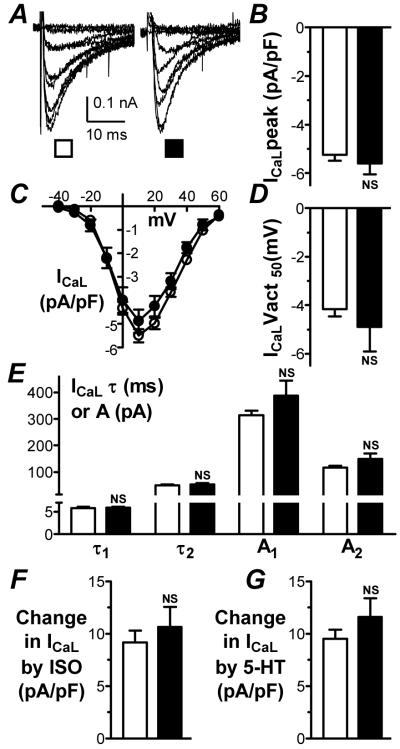

Peak ICaL density (at +10 mV) was similar in cells from patients with and without LVSD (Figure 4A&B). This similarity was maintained in the CABG-only sub-group: -6.0±0.5 vs -5.4±0.3 pA/pF, P>0.05. ICaL also was not significantly different between patients with LVEF≤ 45% (-4.7±0.5 pA/pF; n=51 cells, 13 patients) and >45% (-5.7±0.5 pA/pF; n=54 cells, 15 patients, P>0.05). ICaL was not different at any voltage, between patients with and without LVSD (Figure 4C), and Vact50 also was similar (Figure 4D). ICaL decay was bi-exponential, and both time constants and amplitudes of decay, measured at +10 mV, were similar between patients with and without LVSD (Figure 4E). In a sub-group of cells, the magnitude of increase in peak ICaL in response to acute superfusion with either isoproterenol or 5-hydroxytryptamine at near-maximally effective concentrations13,15 was assessed. There was no significant difference between cells from patients with and without LVSD in the response to either drug (Figure 4F&G).

Figure 4. ICaL characteristics in atrial cells from patients with and without LVSD.

ICaL recordings (A), peak density (B), current-voltage relations (C), Vact50 (D) and decay kinetics (E) in no LVSD (□; n=167-222 cells, 61-73 patients) and moderate/severe LVSD (■; n=36-65 cells, 12-19 patients). Comparison of stimulatory effects on ICaL of isoproterenol (ISO; 50 nM) (F) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; 10 μM) (G) between no LVSD (□; n=45 cells, 19 patients for ISO; 37 cells, 23 patients for 5-HT) and moderate/severe LVSD (■; n=12 cells, 6 patients for ISO; 10 cells, 5 patients for 5-HT).

Discussion

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients who were in SR was independently associated with shortening of their atrial isolated cellular ERP. Previous reports of associations between atrial cell APD, an important determinant of ERP, and human CHF or LVSD are equivocal, likely due to differing experimental conditions and/or clinical characteristics of patients studied.3,4,6 For example, APD90 was longer in cells from explanted, than from donor, hearts,4 but not different6 or shortened5 between LVEF<45% and >60%, despite action potential plateau depression.4,6 A comparison of the present data with those studies is difficult, however, since they included cells with resting potentials of -50 mV or more positive4,6 which would have relatively slow responses, or patients with chronic AF.4 Furthermore, whilst AF accompanies a number of pathologies, the present cohort was dominated by coronary artery disease. In a single clinical study, CHF was associated with a moderate (≤ 10%) atrial ERP-lengthening at rates ≥ 100 bpm, but lower, physiological, rates were not studied.16 The relevance of the measurement of the ERP and APD90 in isolated cells is supported by the demonstration that human chronic AF was associated with shortening of either, or both parameters in atrial isolated cells,2,15,17 as in atrial isolated tissues,17,18 and RA appendages in-vivo.19 The present ERP-shortening associated with LVSD may be expected, therefore, to contribute to a shortened atrial ERP in-vivo, and consequently, a shortened reentrant wavelength. On the other hand, LVSD was associated with an increase in dV/dtmax, which might oppose wavelength-shortening, by increasing conduction velocity. However, the dV/dtmax increase was smaller (11%) than the ERP decrease (24%) and, moreover, should increase conduction velocity by only 4%, according to a mathematical model of a cardiac fibre.20 The combined observed ERP and dV/dtmax changes should, therefore, shorten the wavelength by ~20%.

The consequence of such wavelength-shortening, in the atria of patients in SR with LVSD, would be an increased propensity to reentry. Consistent with that, atrial wavelength-shortening that was produced either by drugs21 or chronic AF,22 increased the vulnerability to induction of AF. Furthermore, CHF or LVSD may cause additional atrial electrophysiological changes that may predispose to AF, particularly in the presence of a shortened wavelength. CHF promoted afterdepolarisations in canine atrial cells,23,24 possibly from [Ca2+]i-overload24 and enhanced Na+/Ca2+ exchanger current,25 which might produce triggered activity in-vivo and facilitate the initiation of reentry. Elevated sympathetic tone, which may accompany CHF, could promote such activity. However, the present experiments with isoproterenol suggest that this would not involve an altered ICaL response to β-stimulation. CHF also causes fibroblasts and collagen to accumulate between fibres or cells of both atria,26 associated with disturbed local conduction, perhaps facilitating microreentry.26 Any associated cellular uncoupling may be expected to have a greater influence on conduction velocity than the present change in dV/dtmax,20 which would result in a correspondingly greater reduction in wavelength and predisposition to AF. Furthermore, atrial fibrosis and susceptibility to AF may persist in CHF after the reversal of ionic remodelling.27

The ionic changes we found in LVSD and which might, therefore, have contributed to the atrial ERP-shortening, were a reduction in ITO, in line with the shift in its activation voltage. Previous reports of changes in human atrial ITO associated with cardiac disease include a reduction with atrial dilation28 and an increase with LVSD.6 However, the latter may have been compounded by the lower proportion of patients treated with β-blockers in the LVSD group,6 since such treatment is associated with decreased ITO in human atrium.12 A decreased atrial ITO is also a consistent feature of the canine model of CHF.25,29 However, it is unknown what effect a reduction in ITO might have on the human atrial action potential, due to a lack of availability of specific ITO blockers. Mathematical modelling suggested either a shortening or lengthening of APD90, depending on which of two human atrial models (which had differing baseline ITO) was studied.30 Furthermore, either shortening or lengthening of atrial APD90 occurred in a canine model, depending on the initial level of ITO.31 In that model, in support of a link between the present reduction in ITO and APD90, a complex coupling of ITO with ICaL was reported such that ITO reduction shortened APD90 by reducing the driving force and amplitude of ICaL, secondary to phase 1 suppression.31 The absence of change in IK1 was consistent with studies of CHF in dogs,25,29 although a decrease was reported in 3 patients with CHF.4 Furthermore, the absence of change in ISUS was consistent with both a human6 and canine25 study. The lack of change in ICaL was consistent with two reports of human LVSD,5,10 although a decrease was also reported, in two others.8,9 In the more recent study,9 ICaL decrease was independently associated with both decreased LV function and mitral valve disease. However, a comparison with the present data is difficult due to differing overall clinical characteristics of the patients between the two studies (e.g., a higher incidence of valvular disease in the Dinanian study9), and is also potentially compounded by the differing recording temperatures and [Ca2+]i-buffering conditions used. The unaltered ICaL voltage-dependence and decay were in line with the majority of reports.5,8 The action potential dV/dtmax depends predominantly on Na+ conductance, determined by Na+ current (INa) availability, in turn dependent on Na+ channel characteristics and diastolic voltage.20 INa was not measured here, so the mechanism of dV/dtmax increase associated with LVSD is unknown. However, any contributory changes in INa availability potentially arising from altered density or time- or voltage-dependence of activation or inactivation would have been independent of diastolic voltage, since this was ~-80 mV in all cells. Increased dV/dtmax could arise from the ITO reduction, since it has been suggested32 that this current’s rapid activation may oppose INa during phase 0.

The resolution of the ionic mechanisms of the action potential and ERP changes will require measurement of additional currents, as well as [Ca2+]i-handling characteristics,3 in future studies. Nevertheless, we demonstrate here that the overall pattern of atrial ionic remodelling associated with LVSD is clearly different from that already associated with human chronic AF,3 in which both ICaL and ITO were markedly decreased, and IK1 was increased. In line, a disparate pattern of atrial ionic remodelling was also demonstrated in dogs between chronic ventricular tachypacing (VTP)-induced CHF and chronic atrial tachypacing.29 Furthermore, the present work highlights species- and/or ventricular pathology-dependent differences in atrial ionic remodelling, and the importance of obtaining clinical data. In particular, ICaL was clearly unchanged in the present study, yet moderately decreased in canine VTP-induced CHF.25,29 The slow delayed rectifier (IKS) also was decreased in canine CHF,25,29 perhaps contributing to an increase in APD or ERP in some studies of that model23,24,29 (though ERP was unchanged in others26,33), yet the contribution of IKS to human atrial ERP may be negligible.

Limitations of the study

1: The enzymatic isolation of myocytes from atrial appendage tissue is recognised to depolarise Vm. We current-clamped Vm to overcome this and prevent INa inactivation. However, whilst un-clamped Vm was similar in patients with and without LVSD, Vm in-vivo may vary with pathology, with the potential to affect ERP in clamped cells. 2: LV function was assessed qualitatively or quantitatively, rather than uniformly for all patients. 3: The possibility of asymptomatic AF having been missed cannot be excluded.

Clinical implications

The clinical implications of the present data are that the treatment of patients who have LVSD and are in SR, with drugs that prolong ERP, might be expected to attenuate an atrial cellular electrophysiological predisposition to AF. In support, amiodarone and dofetilide, the only anti-arrhythmic agents currently recommended for maintenance of SR in patients with AF and CHF,1 each prolong ERP, including in electrically-remodelled atria.34,35 Furthermore, amiodarone reduces the occurrence of new-onset AF in CHF.1 Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors also reduce new-onset AF in CHF, as may β-blockers.1 RAAS inhibitors may inhibit conduction abnormalities caused by structural remodelling, rather than altering ERP,33 but the effect of β-blockers may involve atrial ERP-prolongation, as demonstrated in atrial cells from patients in SR.11,12 Furthermore, in patients with LVSD post-MI, the non-selective β-blocker carvedilol exerted a powerful atrial anti-arrhythmic effect, even in patients already taking an ACEI.36

Conclusion

The present work contributes to the understanding of the pattern of atrial cellular electrophysiological changes associated with, and potentially caused by, LVSD in patients who underwent cardiac surgery. The cellular ERP-shortening, which might contribute to a predisposition to AF, may represent a potential therapeutic target for maintaining SR in patients with LVSD.

Acknowledgement of all sources of financial support

British Heart Foundation (BHF) Basic Science Lectureship Renewal: BS/06/003 (AJW); BHF project grant: PG/04/084/17400 (DP); BHF Clinical PhD Studentship: FS/02/036 (CJR); BHF Clinical PhD Studentship: FS/04/087 (GEM); BHF Chair holder’s Award (JAR).

Acknowledgements

The British Heart Foundation for financial support, and Glasgow Royal Infirmary cardiac surgical operating teams for providing atrial tissue.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

No author has a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Neuberger H-R, Mewis C, Van Veldhuisen DJ, et al. Management of atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2568–2577. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC. The contribution of ionic currents to changes in refractoriness of human atrial myocytes associated with chronic atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:226–235. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Workman AJ, Kane KA, Rankin AC. Cellular bases for human atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:S1–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koumi S, Arentzen CE, Backer CL, et al. Alterations in muscarinic K+ channel response to acetylcholine and to G protein-mediated activation in atrial myocytes isolated from failing human hearts. Circulation. 1994;90:2213–2224. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schreieck J, Wang YG, Kalra B, et al. Differential rate dependence of action potentials, calcium inward and transient outward current in atrial myocytes of patients with and without heart failure. Circulation. 1998;98:611. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schreieck J, Wang Y, Overbeck M, et al. Altered transient outward current in human atrial myocytes of patients with reduced left ventricular function. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:180–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsang TSM, Gersh BJ, Appleton CP, et al. Left ventricular diastolic dysfunction as a predictor of the first diagnosed nonvalvular atrial fibrillation in 840 elderly men and women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1636–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02373-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouadid H, Albat B, Nargeot J. Calcium currents in diseased human cardiac cells. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1995;25:282–291. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199502000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinanian S, Boixel C, Juin C, et al. Downregulation of the calcium current in human right atrial myocytes from patients in sinus rhythm but with a high risk of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1190–1197. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng TH, Lee FY, Wei J, et al. Comparison of calcium-current in isolated atrial myocytes from failing and nonfailing human hearts. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996;157:157–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00227894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Workman AJ, Pau D, Redpath CJ, et al. Post-operative atrial fibrillation is influenced by beta-blocker therapy but not by pre-operative atrial cellular electrophysiology. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2006;17:1230–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00592.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Workman AJ, Kane KA, Russell JA, et al. Chronic beta-adrenoceptor blockade and human atrial cell electrophysiology: evidence of pharmacological remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;58:518–525. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redpath CJ, Rankin AC, Kane KA, et al. Anti-adrenergic effects of endothelin on human atrial action potentials are potentially anti-arrhythmic. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;40:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grubb NR, Newby DE, editors. Churchill’s pocketbook of cardiology. Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pau D, Workman AJ, Kane KA, et al. Electrophysiological and arrhythmogenic effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine on human atrial cells are reduced in atrial fibrillation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanders P, Morton JB, Davidson NC, et al. Electrical remodeling of the atria in congestive heart failure. Electrophysiological and electroanatomic mapping in humans. Circulation. 2003;108:1461–1468. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000090688.49283.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dobrev D, Graf E, Wettwer E, et al. Molecular basis of downregulation of G-protein-coupled inward rectifying K+ current (IK,ACh) in chronic human atrial fibrillation: decrease in GIRK4 mRNA correlates with reduced IK,ACh and muscarinic receptor-mediated shortening of action potentials. Circulation. 2001;104:2551–2557. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wettwer E, Hala O, Christ T, et al. Role of IKur in controlling action potential shape and contractility in the human atrium: influence of chronic atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2004;110:2299–2306. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145155.60288.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu WC, Lee SH, Tai CT, et al. Reversal of atrial electrical remodeling following cardioversion of long-standing atrial fibrillation in man. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:470–476. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Ionic mechanisms of propagation in cardiac tissue. Roles of the sodium and L-type calcium currents during reduced excitability and decreased gap junction coupling. Circ Res. 1997;81:727–741. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rensma PL, Allessie MA, Lammers WJEP, et al. Length of excitation wave and susceptibility to reentrant atrial arrhythmias in normal conscious dogs. Circ Res. 1988;62:395–410. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.2.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wijffels MCEF, Kirchhof CJHJ, Dorland R, et al. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation. 1995;92:1954–1968. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.7.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stambler BS, Fenelon G, Shepard RK, et al. Characterization of sustained atrial tachycardia in dogs with rapid ventricular pacing-induced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:499–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeh Y-H, Wakili R, Qi X-Y, et al. Calcium-handling abnormalities underlying atrial arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in dogs with congestive heart failure. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2008;1:93–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.754788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D, Melnyk P, Feng J, et al. Effects of experimental heart failure on atrial cellular and ionic electrophysiology. Circulation. 2000;101:2631–2638. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li D, Fareh S, Leung TK, et al. Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs. Atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation. 1999;100:87–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cha TJ, Ehrlich JR, Zhang L, et al. Dissociation between ionic remodeling and ability to sustain atrial fibrillation during recovery from experimental congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:412–418. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109501.47603.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le Grand B, Hatem S, Deroubaix E, et al. Depressed transient outward and calcium currents in dilated human atria. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:548–556. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.4.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cha TJ, Ehrlich JR, Zhang L, et al. Atrial ionic remodeling induced by atrial tachycardia in the presence of congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;110:1520–1526. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000142052.03565.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang H, Garratt CJ, Zhu J, et al. Role of up-regulation of IK1 in action potential shortening associated with atrial fibrillation in humans. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;66:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenstein JL, Wu R, Po S, et al. Role of the calcium-independent transient outward current Ito1 in shaping action potential morphology and duration. Circ Res. 2000;87:1026–1033. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nattel S, Burstein B, Dobrev D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and implications. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2008;1:62–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.754564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li D, Shinagawa K, Pang L, et al. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on the development of the atrial fibrillation substrate in dogs with ventricular tachypacing-induced congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2608–2614. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li D, Benardeau A, Nattel S. Contrasting efficacy of dofetilide in differing experimental models of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2000;102:104–112. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shinagawa K, Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Schram G, et al. Effects of antiarrhythmic drugs on fibrillation in the remodeled atrium: insights into the mechanism of the superior efficacy of amiodarone. Circulation. 2003;107:1440–1446. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055316.35552.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMurray J, Kober L, Robertson M, et al. Antiarrhythmic effect of carvedilol after acute myocardial infarction: results of the Carvedilol Post-Infarct Survival Control in Left Ventricular Dysfunction (CAPRICORN) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]