Abstract

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that has spread rapidly throughout the U.S. and there is currently no effective treatment. Understanding the pathogenesis of WNV infection in humans is critical for development of a potent therapy. In this study, we examined the activation of primary human macrophages in response to WNV infection, and showed that WNV interacts with human macrophages at multiple levels. While infection with WNV induced production of interleukin (IL)-8, production of IL-1β, and type I interferon was inhibited. Infection with WNV interferes with the downstream JAK/STAT pathway, which is important for macrophage activation. In comparison to other related flaviviruses, the differential response of proinflammatory cytokines is distinct to WNV.

INTRODUCTION

West Nile virus (WNV) is a mosquito-borne single-stranded positive-polarity RNA FLAVI-VIRUS related to dengue, St. Louis, and Japanese encephalitis viruses (7). WNV is endemic in parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe, and it was introduced to North America in 1999. WNV has spread rapidly throughout the United States with over 4000 cases in 2006, including 161 fatalities (12), and no effective prophylactic or therapeutic measures are currently available (7). Understanding the pathogenesis of WNV infection in humans is crucial for the development of effective treatments.

Dissemination of WNV occurs before development of a full adaptive immune response, thus the innate immune response is critical for resistance to infection. The essential role of macrophages in resistance to WNV infection has been shown in mice depleted of macrophages, which show accelerated development of WNV encephalitis and a 50% increase in mortality (1). WNV has been shown to attenuate antiviral responses in certain cell lines (11,13), but it is unknown if human macrophage responses are inhibited.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To determine the responses of human macrophages upon WNV infection, we isolated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from the blood of healthy donors and cultured cells for 6-8 d, as previously described (14). Serum from these individuals indicates no prior infection with WNV as determined by ELISA and Western blot against WNV envelope protein (data not shown). To determine optimal infection conditions, we infected unstimulated monocyte-derived macrophages with WNV isolate CT-2741 at three multiplicities of infection (MOI; 0.1, 1, and 10). Culture supernatants were collected at day 0, 1, 2, and 3 post-infection and assessed for the production of IL-8, as it has been shown to be among the first cytokines to be secreted by macrophages on infection with other flaviviruses (2). IL-8 was detected at a basal level (∼2 ng/mL) from uninfected macrophages or from macrophages infected with WNV at a MOI of 0.1. The levels of IL-8 were significantly higher from cells infected with WNV at an MOI of 1, and levels increased on each of the 3 days (n = 3; day 1, 6.7 ± 1.3 ng/mL; day 2, 8.0 ± 1.3 ng/ml; day 3, 9.3 ± 2.0 ng/ml). At an MOI of 10, the IL-8 levels were strongly elevated at all time points (n = 3; day 1, 11.5 ± 2.6 ng/mL; day 2, 20.5 ± 3.0 ng/ml; day 3, 12.7 ± 2.2 ng/mL), but we observed cytopathic effects at 48 h post-infection at this MOI (data not shown). Thus, all subsequent studies with WNV and human primary macrophages were performed over the course of 3 d using an MOI of 1. The production of IL-8 after infection with WNV shows that initial steps of the proinflammatory innate immune response are intact in WNV-infected human macrophages.

RESULTS

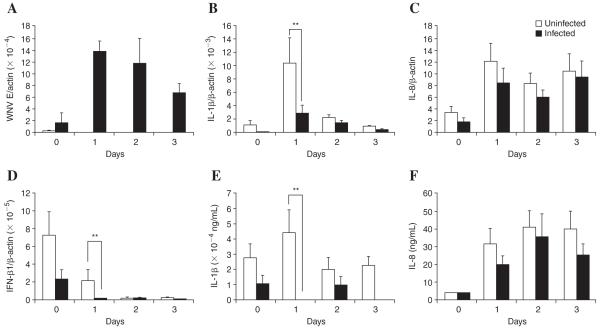

Human macrophages secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, upon encountering pathogens (9). Since other flaviviruses have been demonstrated to inhibit antiviral responses in cell lines (5,6,11,16), we postulated that WNV would downregulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines in primary human macrophages. Production of IL-1β and IFN-β from resting macrophages infected with WNV was undetectable by ELISA (data not shown). This effect may be in contrast to infection with the related dengue virus, in which infected primary macrophages produce elevated levels of IL-1β over the course of 2 wk (2). However, differences in experimental systems or different efficiencies of viral infection may also contribute to these apparent differences. To assess whether WNV inhibits the proinflammatory response of macrophages, primary macrophages were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of IFN-γ and 1μg/mL of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Activation of the cells was confirmed by RT-PCR of IFN-response gene RNase L/actin, showing a 9.2-fold increase over unstimulated cells (data not shown). WNV was able to infect activated macrophages and the majority of treated cells were infected (day 1: 86.7%; day 2: 83.6%; day 3: 97.6%), as assessed by immunofluorescent staining of fixed cells using a rabbit anti-WNV E protein antibody (4) according to our standard imaging protocols (14). This finding is consistent with earlier work showing that monocyte-derived macrophages from healthy donors are able to support WNV infection (15). The infection decreased gradually from day 1 to day 3 as shown by the level of WNV envelope (E) gene transcript (Fig. 1A). As expected, the activation of macrophages with IFN-γ and LPS significantly increased the expression of IL-1β, IL-8, and IFN-β1 (Fig. 1B, C, and D). At day 1, the IL-1β transcript level was elevated ninefold, and declined at day 2 and day 3 (Fig. 1B). The production of proinflammatory cytokines by activated macrophages, however, was significantly inhibited as a result of WNV infection. Production of IL-1β was inhibited most dramatically on day 1 post-infection, when there was a 3.7-fold and 30.4-fold reduction in IL-1β transcript and protein level, respectively, in WNV-infected activated macrophages, as compared to uninfected activated macrophages (Fig. 1B and E). The inhibitory effect of WNV was observed over the course of 3 d, albeit the difference on day 2 did not reach statistical significance. This finding provides the first evidence of an anti-inflammatory effect of WNV on activated human macrophages.

FIG. 1.

Effects of WNV infection on cytokine production by activated macrophages. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation from blood of healthy donors (14) in accordance with the regulations of the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University. PBMCs were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium containing 20% human serum (Cambrex, East Rutherford, NJ), 1000 U/mL penicillin, and 1000 μg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA). Cells were plated at 5 × 106/35 mm3 per well, or 10 × 106/60 mm3 per plate. After 2 h, non-adherent cells were removed by washing, and the cells were incubated for 6-8 d to obtain mature primary monocyte-derived macrophages. Macrophages from seven healthy blood donors were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of IFN-γ and 1μg/mL of LPS upon inoculation of WNV at an MOI of 1. At time points of day 0, 1, 2, and 3 post-infection, total mRNA was harvested and used to quantitatively determine the cytokine transcripts (17). Each expression profile is expressed as the copy number of cytokine gene transcripts/the copy number of the β-actin gene transcript for each sample; each gene assessed is 100-fold above the detection limit of the instrument. Two determinations were done in each sample and significance was determined by ANOVA. (A) The envelope gene copy of WNV. (B) IL-1β (**Day 1, p = 0.025). (C) IL-8. (D) IFN-β1 (**Day 1, p = 0.0007). Supernatants were collected and levels of secreted cytokines were determined by ELISA. Each individual sample (n = 7) was assessed in duplicate in independent ELISA assays. (E) IL-1β (**Day 1, p = 0.0013). (F) IL-8.

Interestingly, when we assessed the effect of WNV infection on the production of IL-8 by activated macrophages, there was no significant change in IL-8 at either the mRNA or protein levels at any time point examined (Fig. 1C and F). This suggests that the production of IL-8 by activated macrophages is regulated differently than IL-1β, and is not subject to viral inhibition.

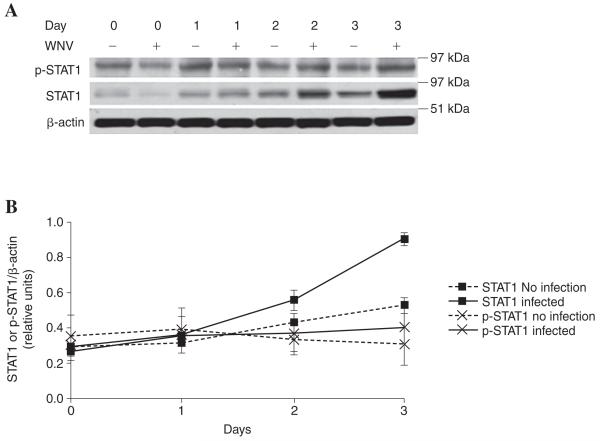

Production of proinflammatory cytokines follows phosphorylation of the signaling kinases JAK/STAT (8). WNV can inhibit the phosphorylation of STAT-1 and STAT-2 in human cell lines, including inhibiting IFN-β-dependent phosphorylation of STAT-1 (11,13). To identify a mechanism of viral inhibition of the macrophage cytokine response, we assessed the effect of WNV infection on phosphorylation of JAK/STAT in human primary macrophages. Infection with WNV led to an increase in the production of STAT-1 protein by activated macrophages over the course of 3 d (Fig. 2A). However, the increased levels of STAT-1 protein did not lead to a concomitant increase in phosphorylation (Fig. 2A and B). The decrease in the ratio of p-STAT to STAT will lead to a lower degree of activation for WNV-infected macrophages, including reduced production of IL-1β (10). Our findings of JAK/STAT inhibition by WNV in primary macrophages is consistent with previous reports in which a WNV replicon inhibited the phosphorylation of STAT-1 and STAT-2 in Vero cells, and interfered with the nuclear translocation of these transcription factors to upregulate an antiviral response (6,11,13,16).

FIG. 2.

(A) Western blot analysis of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT1. Human primary macrophages from healthy blood donors were stimulated with 10 ng/mL of IFN-γ and 1μg/mL of LPS in the absence (-) or presence (+) of WNV at an MOI of 1. Total proteins were harvested at days 0, 1, 2, and 3 post-infection, with modified RIPA lysis buffer containing 1 mM sodium vanadate (Na3VO4), 1 mM sodium fluoride (NaF), 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Equal amounts of protein lysates were electrophoresed on a 4-12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen) and processed for immunoblotting. Phosphorylated and total STAT were detected using 1:600 dilutions of rabbit anti-phospho-STAT1(Tyr701) and anti-STAT-1 antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA), respectively, and detected by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated mouse anti-rabbit antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). The immunoblot was developed using a Western Lightning chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The positions of the pre-stained molecular mass marker are indicated. The immunoblot shown represents two equivalent experiments from different blood donors. (B) Densitometric ratios show average ± SEM of p-STAT1 (X) and total STAT1 (■) to β-actin, as determined using Scion imaging software (Scion Corp., Frederick, MD).

DISCUSSION

The fact that WNV was able to upregulate the production of IL-8 in unstimulated macrophages, and that the production of this cytokine was not inhibited by WNV infection in activated macrophages, suggests that WNV may not suppress chemotaxis induced by macrophages. Although IL-8 may modulate the permeability of endothelial cells (3,17), it is unknown whether it plays a role in blood-brain barrier permeability in human cases of WNV encephalitis. These differences in host response to viruses provide important insights into understanding the human immune response toward WNV infections.

WNV inhibits the production of type I interferons in various human cell lines (6,11,16). When activated macrophages were infected with WNV, the production of IFN-β1 was dramatically reduced (Fig. 1D). On day 1 post-infection, there was a 95% reduction in the transcription of IFN-β1 by infected macrophages as compared to uninfected macrophages. As the IFN-β1 level declined over the course of infection, WNV infection consistently diminished the production of IFN-β1 (Fig. 1D).

CONCLUSION

In summary, our studies provide insight into understanding the human immune response toward WNV infection. WNV suppresses functions of human macrophages by inhibiting the production of proinflammatory and antiviral cytokines, and interfering with the JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (N01-AI-50031 and AI 070343). The authors wish to thank Feng Qian and Lin Zhang for assistance and helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ben-Nathan D, Huitinga I, Lustig S, van Rooijen N, Kobiler D. West Nile virus neuroinvasion and encephalitis induced by macrophage depletion in mice. Arch Virol. 1996;141:459–469. doi: 10.1007/BF01718310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen YC, Wang SY. Activation of terminally differentiated human monocytes/macrophages by dengue virus: Productive infection, hierarchical production of innate cytokines and chemokines, and the synergistic effect of lipopolysaccharide. J Virol. 2002;76:9877–9887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9877-9887.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coyne CB, Vanhook MK, Gambling TM, Carson JL, Boucher RC, Johnson LG. Regulation of airway tight junctions by proinflammatory cytokines. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:3218–3234. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gould LH, Sui J, Foellmer H, et al. Protective and therapeutic capacity of human single-chain Fv-Fc fusion proteins against West Nile virus. J Virol. 2005;79:14606–14613. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.23.14606-14613.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grandvaux N, tenOever BR, Servant MJ, Hiscott J. The interferon antiviral response: From viral invasion to evasion. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002;15:259–267. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo JT, Hayashi J, Seeger C. West Nile virus inhibits the signal transduction pathway of alpha interferon. J Virol. 2005;79:1343–1350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1343-1350.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayes EB, Gubler DJ. West Nile Virus: Epidemiology and clinical features of an emerging epidemic in the United States. Ann Rev Med. 2006;57:181–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Held TK, Weihua X, Yuan L, Kalvakolanu DV, Cross AS. Gamma interferon augments macrophage activation by lipopolysaccharide by two distinct mechanisms, at the signal transduction level and via an autocrine mechanism involving tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1. Infect Immun. 1999;67:206–212. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.206-212.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janeway CA, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Ann Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshi VD, Kalvakolanu DV, Chen W, et al. A role for Stat1 in the regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-1beta expression. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:739–747. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keller BC, Fredericksen BL, Samuel MA, Mock RE, Mason PW, Diamond MS, Gale M., Jr. Resistance to alpha/beta interferon is a determinant of West Nile virus replication fitness and virulence. J Virol. 2006;80:9424–9434. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00768-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsey NP, Lehman JA, Hayes EB, Nasci RS, Komar N, Petersen LR. West Nile Virus Activity-United States, 2006. JAMA. 2007;298:619–621. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Mokhonov VV, Shi PY, Randall R, Khromykh AA. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the New York 99 strain and Kunjin subtype of West Nile virus involves blockage of STAT1 and STAT2 activation by nonstructural proteins. J Virol. 2005;79:1934–1942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1934-1942.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery RR, Lusitani D, de Boisfleury Chevance A, Malawista SE. Human phagocytic cells in the early innate immune response to Borrelia burgdorferi. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1773–1779. doi: 10.1086/340826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rios M, Zhang MJ, Grinev A, et al. Monocytes-macrophages are a potential target in human infection with West Nile virus through blood transfusion. Transfusion. 2006;46:659–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scholle F, Mason PW. West Nile virus replication interferes with both poly(I:C)-induced interferon gene transcription and response to interferon treatment. Virology. 2005;342:77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Talavera D, Castillo AM, Dominguez MC, Gutierrez AE, Meza I. IL-8 release, tight junction and cytoskeleton dynamic reorganization conducive to permeability increase are induced by dengue virus infection of microvascular endothelial monolayers. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1801–1813. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19652-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]