Abstract

Aldosterone produces a multitude of effects in vivo, including promotion of postmyocardial infarction adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure progression. It is produced and secreted by the adrenocortical zona glomerulosa (AZG) cells after angiotensin II (AngII) activation of AngII type 1 receptors (AT1Rs). Until now, the general consensus for AngII signaling to aldosterone production has been that it proceeds via activation of Gq/11-proteins, to which the AT1R normally couples. Here, we describe a novel signaling pathway underlying this AT1R-dependent aldosterone production mediated by β-arrestin-1 (βarr1), a universal heptahelical receptor adapter/scaffolding protein. This pathway results in sustained ERK activation and subsequent up-regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, a steroid transport protein regulating aldosterone biosynthesis in AZG cells. Also, this βarr1-mediated pathway appears capable of promoting aldosterone turnover independently of G protein activation, because treatment of AZG cells with SII, an AngII analog that induces βarr, but not G protein coupling to the AT1R, recapitulates the effects of AngII on aldosterone production and secretion. In vivo, increased adrenal βarr1 activity, by means of adrenal-targeted adenoviral-mediated gene delivery of a βarr1 transgene, resulted in a marked elevation of circulating aldosterone levels in otherwise normal animals, suggesting that this adrenocortical βarr1-mediated signaling pathway is operative, and promotes aldosterone production and secretion in vivo, as well. Thus, inhibition of adrenal βarr1 activity on AT1Rs might be of therapeutic value in pathological conditions characterized and aggravated by hyperaldosteronism.

Keywords: adrenocortical zona glomerulosa cell, G protein-coupled receptor, angiotensin II receptor type I, adrenal steroid hormones, biased agonism

Aldosterone is one of a number of hormones that can be detrimental to myocardium, and whose circulating levels are elevated in chronic heart failure (HF). It contributes significantly to HF progression after myocardial infarction (MI), and to the morbidity and mortality of the disease (1–3). Aldosterone's main actions on the post-MI heart include (but are not limited to) cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and increased inflammation and oxidative stress, all of which result in adverse cardiac remodeling and progressive loss of cardiac function and performance (2–4).

Aldosterone is a mineralocorticoid produced and secreted by the cells of the zona glomerulosa (ZG) of the adrenal cortex in response to either elevated serum potassium levels or to angiotensin II (AngII) acting through its type 1A receptors (AT1ARs), which are endogenously expressed in the adrenocortical ZG (AZG) cells (5, 6). AT1Rs belong to the superfamily of 7-transmembrane spanning G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), and, on agonist activation, couple to the Gq/11 family of G proteins (6). However, over the past few years, a number of GPCRs, including the AT1R, have been shown to also signal through G protein-independent pathways. The protein scaffolding actions of β-arrestin-1 (βarr1) and βarr2 (also known as arrestins 2 and 3, respectively), originally discovered as terminators of GPCR signaling after phosphorylation of these receptors by the GPCR kinases (GRKs), have a central role in mediating G protein-independent signal transduction by these receptors (7, 8).

We recently reported that adrenal GRK2, the major cofactor of βarr action toward receptors, is up-regulated in HF, leading through its concerted action with βarr1 to increased desensitization/down-regulation of α2-adrenoceptors, and this effect mediates the increased adrenal catecholamine output seen in HF (9). Because adrenal aldosterone production stimulated by AngII is increased in HF (1–3), and βarr1 also regulates AT1R signaling (7, 8), we hypothesized that adrenal βarr1 might mediate the signaling of AT1R to aldosterone production and secretion. To test this hypothesis in vitro, we used the human AZG cell line H295R, which endogenously expresses the AT1R, but not the AT2R (the other AngII receptor type). Importantly, these cells produce and secrete aldosterone in response to AngII stimulation (10, 11). To examine whether adrenal βarr1 influences aldosterone turnover in vivo, we used our previously developed methodology for adrenal-targeted, adenoviral-mediated gene transfer (9, 12) of wild-type full-length βarr1 in normal rats. We have uncovered a novel signaling pathway mediated by βarr1 that leads to aldosterone production by the AT1R in AZG cells in vitro, which, importantly, is also operative in vivo, because adrenal βarr1 overexpression was found to be capable of increasing circulating levels of aldosterone in vivo.

Results

The βarr1-Mediated AngII-Induced Aldosterone Production in Vitro.

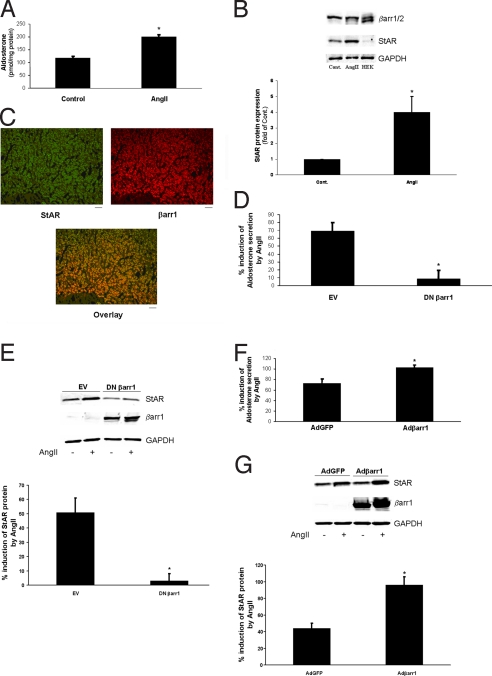

Because AngII is known to promote aldosterone production in AZG cells, we set out to explore a potential role for βarrs in this effect. In H295R cells, treatment with 10 nM AngII leads to a significant induction of aldosterone secretion, as expected (Fig. 1A). Western blotting with an antibody against both βarr isoforms in native extracts from these cells revealed that only βarr1 is expressed endogenously in significant amounts (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this finding, human adrenal glands express βarr1 robustly (Fig. S1), and, importantly, βarr1 colocalizes with the known adrenocortical protein, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), in human adrenocortical sections (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Involvement of βarr1 in AngII-induced aldosterone production and secretion in H295R cells. (A) Aldosterone secretion in response to 10 nM AngII treatment (AngII) or vehicle (Control) for 6 h in H295R cells. *, P < 0.05; n = 4 independent experiments. (B) Representative immunoblots for endogenous βarrs and StAR in protein extracts from vehicle- (Control) and AngII-treated (AngII) H295R cells, including blots for GAPDH as loading control. A lane run with extract from HEK293 cells (HEK), as a positive control for both βarr isoforms, is also shown (Upper). Densitometric analysis of StAR protein expression normalized to GAPDH levels. *, P < 0.05; n = 4 independent experiments (Lower). (C) Coimmunofluorescence in sections of human adrenal glands using antibodies specific for StAR (green) and βarr1 (red), showing colocalization of the 2 fluorescent signals (yellow), which indicates endogenous expression of βarr1 in human adrenocortical cells. (Scale bar, 100 μm.) (D) Aldosterone secretion in H295R cells transfected with EV or with a plasmid encoding for the V53D DN βarr1, and stimulated with 10 nM AngII or vehicle for 6 h. *, P < 0.05; n = 5 independent experiments. (E) Western blotting for StAR in these cells at the end of the indicated treatments. Blots for βarr1 to confirm DN βarr1 overexpression are also shown, along with GAPDH as loading control. (Upper) Representative blots; (Lower) densitometric quantification of 5 independent experiments. *, P < 0.05; n = 5. (F) Aldosterone secretion in H295R cells transfected with Adβarr1 or AdGFP, and stimulated with 10 nM AngII or vehicle for 6 h. *, P < 0.05; n = 5 independent experiments. (G) Western blotting for StAR. (Upper) Representative blots confirming the overexpression of βarr1, along with GAPDH as loading control. (Lower) Densitometric quantification of 5 independent experiments. *, P < 0.01; n = 5.

Aldosterone synthesis in AZG cells is initiated by the mitochondrial uptake of cholesterol, the precursor of all adrenal steroids (10). Mitochondrial cholesterol uptake is the rate-limiting step of this procedure, and is catalyzed by the steroid transport protein StAR, whose levels are up-regulated in response to AngII stimulation (10, 13). Consistent with this notion, we observed a large StAR up-regulation in H295R cells 6-h post-AngII stimulation (Fig. 1B).

To test whether endogenous βarr1 has a role in AngII-induced aldosterone production/secretion, we transfected H295R cells with the V53D dominant negative (DN) βarr1 mutant, which prevents βarr1 from interacting with its various intracellular nonreceptor binding partners (14, 15). As shown in Fig. 1D, DN βarr1 overexpression led to marked inhibition of AngII-induced aldosterone secretion, compared with control empty vector (EV)-transfected cells. Also, the AngII-induced StAR up-regulation normally observed in EV-transfected cells was absent in DN βarr1-transfected cells (Fig. 1E). Conversely, transfection of H295R cells with an adenovirus encoding for wild-type βarr1 (Adβarr1) led to significantly enhanced AngII-induced aldosterone secretion compared with control AdGFP-transfected cells (Fig. 1F), which was also accompanied by a marked enhancement of AngII-induced StAR up-regulation (Fig. 1G). Together, these results show that βarr1 is necessary for AngII-induced StAR up-regulation and subsequent aldosterone production in AZG cells in vitro.

The βarr1-Mediated AT1R Signaling to Aldosterone Production Involves DAG and Sustained ERK Activation.

To further dissect the signaling pathway of AngII-induced aldosterone production mediated by βarr1 in AZG cells, we focused on βarr1-promoted ERK1/2 activation. ERK1/2 have a central role in StAR up-regulation by means of inducing StAR gene transcription in response to AngII stimulation in AZG cells (13); βarrs have been shown to mediate AT1R signaling to ERKs in various heterologous cell systems in vitro (7, 8). After AngII stimulation for various times, we found that βarr1 overexpression does lead to sustained AngII-induced ERK1/2 activation in H295R cells, lasting at least 6 h and contrary to a more transient ERK1/2 activation by AngII in control AdGFP-transfected cells (Fig. 2 A and B). Conversely, inhibition of endogenous βarr1 by DN βarr1 abrogates AngII-induced ERK1/2 activation in H295R cells compared with EV-transfected cells (Fig. 2 A and B). These data indicate that βarr1 promotes a sustained AngII-induced ERK1/2 activation, which could underlie the observed βarr1-promoted StAR up-regulation and aldosterone production in response to AngII in AZG cells.

Fig. 2.

βarr1-mediated AngII signaling to aldosterone production in H295R cells. (A) Western blotting for phospho-ERK1/2 and for total ERK2 in extracts from transfected H295R cells after 10 nM AngII stimulation for the indicated times. Representative blots of 3 independent experiments are shown, including blots for βarr1 to confirm the overexpression of the transfected proteins. (B) Densitometric quantification of the 3 independent experiments performed in A. *, P < 0.05, vs. AdGFP; **, P < 0.05, vs. DN βarr1. (C and D) Western blotting in control AdGFP- or in Adβarr1-transfected H295R cells treated with vehicle or 10 nM AngII for 6 h after pretreatment with 10 μM U73122, 10 μM U73122 plus 10 μM DiC8-DAG, or 50 μM PD98059. Representative blots of 3 independent experiments for each cell line are shown, including blots for endogenous βarr1 and for total ERK1/2 and GAPDH as loading controls. (E and F) AngII-induced ERK phosphorylation and StAR up-regulation as densitometrically quantitated in the 3 independent experiments performed in C and D, respectively. Values are expressed as percentage of the AngII response of cells not pretreated with any agent (No Inhibitor). *, P < 0.05, vs. No Inhibitor; n = 3. (G) Aldosterone secretion in Adβarr1- or AdGFP-transfected cells pretreated with 10 μM U73122 or 50 μM PD98059, followed by 10 nM AngII or vehicle stimulation for 6 h. No significant differences at P = 0.05; n = 3 independent experiments. (H) Aldosterone secretion in Adβarr1- or AdGFP-transfected cells pretreated with 10 μM U73122 plus 10 μM DiC8-DAG, followed by 10 nM AngII or vehicle stimulation for 6 h. *, P < 0.05, vs. −AngII; n = 3 independent experiments.

Recently, βarr1 was shown to recruit the diacylglycerol (DAG) kinases (DGKs) to activated M1 muscarinic cholinergic receptors, which also couple to Gq proteins, like the AT1Rs, thereby catalyzing the conversion of the Gq-dependent second messenger DAG to phosphatidic acid (PA) at the cell membrane (16). PA is a potent ERK cascade activator by means of bringing together Ras and Raf1 kinase at the level of the plasma membrane to interact with each other (17). Therefore, we hypothesized that this βarr1-mediated mechanism could be at play in AngII-induced sustained ERK1/2 activation in AZG cells, as well. To test this premise, we pretreated transfected H295R cells with the phospholipase C (PLC) inhibitor U73122 (18), to suppress all DAG production before AngII stimulation. In the presence of PLC inhibition, βarr1 overexpression is unable to induce StAR up-regulation or ERK activation in response to AngII stimulation, which are also absent in control AdGFP-transfected cells, as expected (Fig. 2 D and C, respectively, and quantitation in Fig. 2 F and E, respectively). However, adding the cell-permeable DAG analog dioctanoylglycerol (DiC8-DAG) (19), which circumvents PLC inhibition and is a DGK substrate, immediately before applying AngII to the PLC inhibitor-treated cells, rescues the ability of βarr1 to mediate StAR up-regulation and ERK activation in response to AngII, both in βarr1-overexpressing and in control AdGFP-transfected cells (Fig. 2 D and C, respectively, and quantitation in Fig. 2 F and E, respectively). Importantly, in the presence of PLC inhibition, βarr1 is also incapable of promoting AngII-induced aldosterone production in H295R cells (Fig. 2G), and this capability is again rescued by the addition of DiC8-DAG (Fig. 2H). Last, application of the MAPK-ERK Kinase-1 (MEK1) inhibitor PD98059 that abolishes ERK1/2 activation led to abrogation of AngII-induced ERK activation and StAR up-regulation (Fig. 2 D and C, respectively, and quantitation in Fig. 2 F and E, respectively), as well as of AngII-induced aldosterone production (Fig. 2G) both in βarr1-overexpressing and in control AdGFP-transfected cells; thus, confirming the vital role of ERK1/2 in mediation of AngII-induced aldosterone production in AZG cells (13). Together, these results indicate that DAG is necessary for βarr1-mediated ERK1/2 activation, StAR up-regulation, and aldosterone production in AZG cells induced by AngII, probably via βarr1-recruited DGK-catalyzed conversion to PA.

The βarr1-Mediated Signaling Pathway Operates Independently of G Protein Activation.

Next, we examined whether this βarr1-mediated signaling pathway of AngII-dependent aldosterone production can proceed without the activation of the cognate AT1R G protein pathway. To this end, we took advantage of the well characterized AngII analog [Sar1,Ile4,Ile8]-AngII (SII), which is a biased AT1R agonist, in that it does not induce the coupling of AT1R to G proteins, but instead induces receptor interaction with βarrs and downstream βarr-mediated signaling (20). As shown in Fig. 3A, SII, at the relatively high concentration of 10 μM, is also able to induce aldosterone secretion from H295R cells, and this capability is enhanced in cells overexpressing βarr1 (Fig. 3A). Conversely, transfection with DN βarr1 abolishes SII-induced aldosterone secretion (Fig. 3A). Of note, 1 μM SII treatment could stimulate aldosterone secretion only in the presence of βarr1 overexpression, consistent with far less potency of this compound at stimulating βarrs compared with AngII (21). Also, 10 μM SII treatment results in ERK1/2 activation (Fig. 3B) and StAR up-regulation (Fig. 3C), which are again enhanced by βarr1 overexpression and abrogated by DN βarr1 (Fig. 3 B and C). Together, these results indicate that βarr1 is able to mediate AT1R signaling to aldosterone production in AZG cells in its own right, i.e., even without concomitant activation of G proteins by the AT1R.

Fig. 3.

SII-induced aldosterone production and secretion in H295R cells. (A) Aldosterone secretion in transfected H295R cells stimulated with 10 μM SII or vehicle for 6 h. Data are shown as the percentage induction over vehicle (basal) levels of aldosterone secretion. *, P < 0.05, vs. AdGFP or EV; n = 5 independent determinations per treatment. (B) Western blotting for phospho-ERK1/2 and for total ERK2 after 10 μM SII or vehicle. (Upper) Representative blots of 3 independent experiments are shown; and (Lower) the percentage SII-induced ERK activation (over basal), as derived by densitometric quantification. *, P < 0.05; n = 3 independent experiments. (C) Western blotting for StAR after 10 μM SII or vehicle. (Upper) Representative blots of 3 independent experiments are shown, including blots for βarr1 to confirm the overexpression of the respective constructs and for GAPDH as loading control; and (Lower) percentage of SII-induced StAR induction (over basal), as derived by densitometric quantification. *, P < 0.05; n = 3 independent experiments.

βarr1 Mediates Aldosterone Production in Vivo.

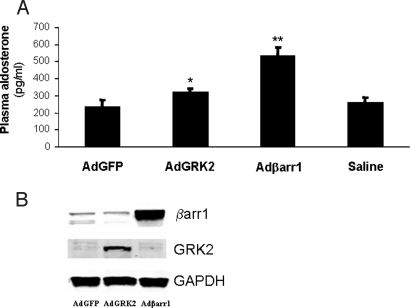

Next, we examined whether adrenal βarr1 can affect aldosterone production in vivo, as well. Adrenal gland-specific overexpression of βarr1 in normal rats via infection with Adβarr1 in vivo led to a significant increase in plasma aldosterone levels compared with control AdGFP rats (536 ± 50 pg/mL vs. 235 ± 40 pg/mL, respectively; n = 5, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4A) at 7 days after in vivo gene delivery; βarr1 was markedly overexpressed in the adrenals of Adβarr1 rats (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

In vivo adrenal-targeted βarr1 overexpression and aldosterone production in normal rats. (A) Plasma aldosterone levels in AdGFP-, AdGRK2-, or Adβarr1-treated, plus in saline-treated (Saline), normal rats at 7 days post in vivo gene transfer. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, vs. AdGFP or Saline; n = 5 rats per group. (B) Representative Western blots in protein extracts from adrenal glands from these rats, confirming the overexpression of the respective transgenes. GAPDH is also shown as loading control.

Because GRK2 is a cofactor of βarr1 activity toward receptors, we also delivered an adenovirus carrying GRK2 (AdGRK2) to normal rat adrenal glands. As shown in Fig. 4A, GRK2 overexpression resulted in a small but significant increase in plasma aldosterone at 7 days after gene delivery compared with control AdGFP-treated rats (322 ± 20 pg/mL; n = 5, P < 0.05 vs. AdGFP), indicating that increased activity/expression of GRK2 in the adrenal gland increases aldosterone production, as well. This finding is consistent with induced βarr1 acting at the plasma membrane. Fig. 4B shows the overexpression of the respective transgenes in the adrenals of normal rats. Of note, all transgenes delivered in vivo displayed adrenal-specific overexpression with no ectopic expression in any other tissue tested (12). Also, plasma aldosterone values in saline-treated rats were similar to AdGFP-treated rats (Fig. 4A), indicating the absence of any nonspecific effects of the adenoviral infection on plasma aldosterone values.

Discussion

Over the past few years, a novel role for βarr1 and 2, molecules initially discovered as terminators of G protein signaling by GPCRs, has emerged, i.e., that these 2 proteins, after uncoupling the activated receptor from its cognate G protein, actually serve as signal transducers for the receptor in their own right (7, 8). However, this novel role of βarrs has, thus, far been demonstrated almost exclusively in heterologous cell systems in vitro. The present study delineates a previously uncovered signaling pathway mediated by βarr1, which operates in vitro and in vivo, in a specialized cell type/tissue (ZG cells of the adrenal cortex), and which leads to an important physiological effect (AngII-induced aldosterone production). Also, this increased aldosterone production may then precipitate diseases that are characterized and aggravated by enhanced circulating levels of this hormone, such as post-MI HF progression (3, 4).

Also, our data strongly suggest that blocking adrenal βarr1 actions on AT1R might serve as a novel therapeutic strategy for lowering aldosterone levels in pathological conditions characterized and precipitated by elevated aldosterone levels, one of the most important of which is post-MI progression to HF.

Suppression of aldosterone production at its various sources, the most important of which physiologically is the adrenal cortex, is of particular importance, because aldosterone has been shown to exert some of its actions (its so-called “nongenomic” actions) by binding other molecular targets than the mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), the molecular target that normally mediates its cellular actions (2, 3). These MR-independent actions are of course unaffected by the currently available MR antagonist drugs, such as eplerenone and spironolactone, used in the treatment of HF. Therefore, curbing aldosterone production at its major source, i.e., the adrenal cortex, by inhibiting βarr1 actions, could presumably be more effective therapeutically than inhibiting its actions at its receptor level.

The pathway of βarr1-dependent AT1R signaling to aldosterone production appears to be initiated by the recruitment of βarr1 to the activated AT1R that scaffolds DGK(s) to the activated receptor. This action, in turn, leads to conversion of DAG to PA, a membrane phospholipid that can directly activate the ERK cascade. The resulting sustained ERK activation leads to activation of StAR gene transcription, thus, causing up-regulation of this cholesterol-transporting protein. The StAR-facilitated mitochondrial uptake of cholesterol subsequently initiates aldosterone synthesis in AZG cells. This signaling pathway is schematically represented in Fig. 5. Of note, StAR is the major regulator of the biosynthesis of all adrenal steroids throughout the adrenal cortex (10), not only of aldosterone; therefore, βarr1 is very likely to be involved in regulation of the synthesis of glucocorticoids and androgens (the other 2 categories of adrenal steroids) by the adrenal cortex, as well.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representation of the signaling pathway of AngII-induced aldosterone production mediated by βarr1. For details, see main text. PIP2, Phosphatidylinositol 4′,5′-bisphosphate; IP3, Inositol 1′,4′,5′- trisphosphate; pERK, phospho-ERK.

Although AT1R has been shown to result in sustained ERK activation via βarrs, it is the βarr2 isoform that has actually been shown to mediate this effect, whereas βarr1 has actually been shown to act in the opposite direction, i.e., rather inhibiting AT1R-induced ERK activation (22). Recently, it was shown in transfected HEK293 cells that βarr1 only inhibits AT1R signaling to ERK by classically desensitizing the receptor (i.e., uncoupling it from the G protein), and βarr2, instead, promotes the G protein-independent signaling of AT1R to ERKs, but this βarr2-mediated ERK activation produces no transcriptional effects (23). Our present findings seem to be in discordance with these studies. However, it should be emphasized here that these studies were done in transfected heterologous systems, with overexpressed receptors at supraphysiological levels, and also with recombinant (not natural) AT1Rs engineered in such a way that they cannot couple to any G proteins. Given that signaling from a given GPCR to ERKs can vary widely depending on the relative concentrations of receptor, G proteins, GRKs, and βarrs, as well as on the cellular context in general (i.e., cell type and cellular signaling machinery) (8, 23), this apparent discrepancy can be easily explained. Also, the H295R cells used in the present study do not express significant amounts of βarr2 endogenously, so βarr2 is unlikely to be involved in AngII-induced aldosterone production, at least in this system (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, it is entirely plausible that βarr2 might have different or even opposite effects on the signaling pathway leading from AT1R activation to aldosterone production in other AZG cell lines or in vivo.

The βarr-activated ERKs have been shown to be largely retained in the cytosol due to their association with receptor-arrestin complexes, thus, not being able to translocate to the nucleus to induce transcriptional effects (22, 23). However, βarr1 localizes in the cytoplasm, as well as in the nucleus by virtue of possessing a nuclear localization sequence, whereas βarr2 is excluded from the nucleus due to a nuclear export sequence present in its molecule (24). In fact, βarr1 translocates into the nucleus in response to stimulation of the μ-opioid receptor, a Gi/o-coupled receptor, wherein it interacts with the p27 and c-Fos promoters, and stimulates transcription by recruiting histone acetyltransferase p300 and enhancing local histone H4 acetylation (25, 26). Additionally, ERK1/2 not only target nuclear transcription factors, but also numerous other plasma membrane, cytoplasmic, and cytoskeletal substrates (27), some of which mediate the reportedly nontranscriptional effects of βarr-activated ERKs, such as chemotactic T and B cell migration (28, 29). However, some other ERK substrates, such as the Rsk and Mnk protein kinases, can translocate to the nucleus, and activate transcription factors; thus, producing the transcriptional effects of activated ERK1/2 indirectly (27). Indeed, the cardiac-specific overexpression of a G protein-uncoupled mutant AT1R has been reported, which induces ERK1/2 activation that promotes a histologically distinct form of cardiac hypertrophy from that caused by the wild-type receptor, with greater cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and less cardiac fibrosis (30). This finding suggests that ERK1/2 activated independently of G proteins can produce transcriptional effects from AT1R activation in vivo, albeit different from the transcriptional effects of G protein-activated ERKs. In the same vein, βarr1 was very recently shown in 3T3-L1 adipocytes to mediate ERK activation from the endogenous TNFα receptor (a cytokine receptor) through Gq/11 proteins, and this βarr1-mediated ERK activation coupled TNFα receptor activation to lipolysis, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation and inflammatory gene expression (31). Together, all these studies indicate that βarr1-activated ERK1/2 can lead to transcriptional effects, which is in complete agreement with our present findings, i.e., that βarr1-activated ERK1/2 increases StAR expression and aldosterone synthesis in AZG cells. Indeed, βarr1-activated ERK1/2 appears to increase StAR expression in H295R cells transcriptionally, via suppression of the early intermediate gene DAX-1 (13), a transcriptional repressor of the StAR gene.

The final important finding of the present study is that SII can completely recapitulate the AngII effects on aldosterone production, albeit at significantly lower concentrations, consistent with its lower potency at AT1R compared with the physiological full agonist AngII. This finding has enormous pharmacological and therapeutic ramifications, because it strongly argues for the existence of at least 2 different active conformations of the AT1R, one of which would lead only to βarr1 and not G protein activation, but which both result in aldosterone production in AZG cells. Therefore, complete blockade of both of these conformations would be warranted to achieve the most effective suppression of AngII-dependent aldosterone production. To our knowledge, the relative efficacy of the currently available AT1R antagonist drugs (the sartans) at inhibiting these 2 signaling pathways emanating from AT1R (i.e., the G protein- and the βarr-mediated) has never been tested. In fact, there have been several reports of limited efficacy of some AT1R antagonists at suppressing aldosterone in HF (32–34), despite their more or less equal capability to inhibit G protein activation by the AT1R. Thus, it would be interesting to examine whether variations in the efficacy of these agents at inhibiting AT1R-βarr coupling could account for their reduced efficacy at suppressing aldosterone. However, based on the results of the present study, the most effective AT1R antagonist at inhibiting AngII-dependent aldosterone production should be an agent that would inhibit both AT1R-G protein and AT1R-βarr1 coupling equally well.

In conclusion, the present study reports a previously undescribed, G protein-independent signaling pathway mediated by βarr1 in AZG cells that underlies aldosterone production in response to AngII in vitro and in vivo. Activity of this pathway appears to regulate adrenal aldosterone production and circulating levels of this mineralocorticoid in vivo. Thus, adrenal βarr1 activity toward the AT1R might represent a therapeutic target for reducing plasma aldosterone levels in pathological conditions where this effect is desirable, including several endocrinological disorders characterized by hyperaldosteronism and cardiovascular disease.

Materials and Methods

SII was a generous gift from P. Cordopatis (University of Patras School of Pharmacy, Patras, Greece). U73122 was from Biomol, and DiC8-DAG from Sigma-Aldrich.

In Vivo Adrenal Gene Delivery in Normal Rats.

All animal procedures and experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Thomas Jefferson University. Adrenal-specific in vivo gene delivery was done essentially as described (12), via direct delivery of adenovirus in the adrenal glands.

Construction and Purification of Adenoviruses.

Recombinant adenoviruses that encode GRK2 (AdGRK2) or rat wild-type, full-length β-arrestin1 (Adβarr1) were constructed as described previously (9). Briefly, transgenes were cloned into shuttle vector pAdTrack-CMV, which harbors a CMV-driven GFP, to form the viral constructs by using standard cloning protocols. As control adenovirus, EV that expressed only GFP (AdGFP) was used. The resultant adenoviruses were purified, as described previously, by using 2 sequential rounds of CsCl density gradient ultracentrifugation (9).

H295R Cell Culture and Transfection.

H295R cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection and cultured as previously described (35). Transfection was performed either with Adβarr1 or AdGFP, with pcDNA3.1 plasmid encoding either for the V53D DN βarr1 mutant (14), or just empty pcDNA3.1 vector (EV). Plasmid transfections were performed by using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen).

Plasma and in Vitro Aldosterone Secretion Measurements.

Rat plasma aldosterone levels and in vitro aldosterone secretion in the culture medium of H295R cells were determined by EIA (Aldosterone EIA kit; ALPCO Diagnostics), as described (34).

Western Blotting.

Western blottings to assess protein levels of StAR (sc-25806), GRK2 (sc-562; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), phospho-ERK1/2 (no. 9106), total ERK1/2 (no. 4696), and total ERK2 (no. 9108; Cell Signaling Technology), βarr1 (A1CT antibody; see ref. 16), and GAPDH (MAB374; Chemicon) were done by using protein extracts from rat adrenal glands or in H295R cell extracts, as described previously (9). Visualization of Western blotting signals was performed with Alexa Fluor 680 (Molecular Probes) or IRDye 800CW-coupled (Rockland) secondary antibodies on a LI-COR infrared imager (Odyssey).

Coimmunofluorescence.

Immunofluorescence imaging of human adrenal cross-sections was carried out as described previously (9). Briefly, human adrenal cross-sections were fixed, permeabilized, and labeled with rabbit polyclonal anti-StAR (sc-25806) and goat anti-βarr1 (sc-9182; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies, followed by the corresponding Alexa Fluor 594 anti-goat (red) and Alexa Fluor 568 anti-rabbit (green) secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Confocal images were obtained by using a 40× objective on a Leica Microsystems TCS SP laser scanning confocal microscope.

Statistical Analyses.

Data are generally expressed as mean ± SEM. Unpaired 2-tailed Student's t test and 1- or 2-way ANOVA with Bonferroni test were generally performed for statistical comparisons, unless otherwise indicated. For all tests, P < 0.05 was generally considered to be significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. R. Lefkowitz for the anti-βarr1/2 antibody and the V53D DN βarr1 mutant plasmid, Dr. M. Santangelo (University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy) for the human adrenal gland tissue, and Dr. P. Cordopatis (University of Patras, Patras, Greece) for [SII]-AngII. W.J.K. was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL56205, R01 HL085503, and P01 HL075443 (Project 2), and by Grant A75301 from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Department of Health. A.L. and G.R. were supported by Great Rivers Affiliate American Heart Association postdoctoral fellowship awards.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0811706106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Weber KT. Aldosterone in congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1689–1697. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Connell JM, Davies E. The new biology of aldosterone. J Endocrinol. 2005;186:1–20. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marney AM, Brown NJ. Aldosterone and end-organ damage. Clin Sci. 2007;113:267–278. doi: 10.1042/CS20070123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao W, Ahokas RA, Weber KT, Sun Y. ANG II-induced cardiac molecular and cellular events: Role of aldosterone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H336–H343. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01307.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganguly A, Davis JS. Role of calcium and other mediators in aldosterone secretion from the adrenal glomerulosa cells. Pharmacol Rev. 1994;46:417–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Gasparo M, Catt KJ, Inagami T, Wright JW, Unger T. International union of pharmacology. XXIII. The angiotensin II receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:415–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ. New Roles for β-Arrestins in Cell Signaling: Not Just for Seven-Transmembrane Receptors. Mol Cell. 2006;24:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of Receptor Signals by β-Arrestins. Science. 2005;308:512–517. doi: 10.1126/science.1109237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lymperopoulos A, Rengo G, Funakoshi H, Eckhart AD, Koch WJ. Adrenal GRK2 upregulation mediates sympathetic overdrive in heart failure. Nat Med. 2007;13:315–323. doi: 10.1038/nm1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rainey WE, Saner K, Schimmer BP. Adrenocortical cell lines. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2004;228:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bird IM, et al. Human NCI-H295 adrenocortical carcinoma cells: A model for angiotensin-II-responsive aldosterone secretion. Endocrinology. 1993;133:1555–1561. doi: 10.1210/endo.133.4.8404594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lymperopoulos A, Rengo G, Zincarelli C, Soltys S, Koch WJ. Modulation of Adrenal Catecholamine Secretion by In Vivo Gene Transfer and Manipulation of G Protein-coupled Receptor Kinase-2 Activity. Mol Ther. 2008;16:302–307. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osman H, Murigande C, Nadakal A, Capponi AM. Repression of DAX-1 and induction of SF-1 expression. Two mechanisms contributing to the activation of aldosterone biosynthesis in adrenal glomerulosa cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:41259–41267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206595200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson SS, et al. Role of beta-arrestin in mediating agonist-promoted G protein-coupled receptor internalization. Science. 1996;271:363–366. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5247.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krupnick JG, Santini F, Gagnon AW, Keen JH, Benovic JL. Modulation of the arrestin-clathrin interaction in cells. Characterization of beta-arrestin dominant-negative mutants. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:32507–32512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.51.32507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson CD, et al. Targeting of Diacylglycerol Degradation to M1 Muscarinic Receptors by β-Arrestins. Science. 2007;315:663–666. doi: 10.1126/science.1134562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizzo MA, Shome K, Watkins SC, Romero G. The Recruitment of Raf-1 to Membranes Is Mediated by Direct Interaction with Phosphatidic Acid and Is Independent of Association with Ras. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23911–23918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001553200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yule DI, Williams JA. U73122 Inhibits Ca2+ Oscillations in Response to Cholecystokinin and Carbachol but Not to JMV-180 in Rat Pancreatic Acinar Cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:13830–13835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maroney AC, Macara IG. Phorbol Ester-induced Translocation of Diacylglycerol Kinase from the Cytosol to the Membrane in Swiss3 T3 Fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2537–2544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahn S, Wei H, Garrison TR, Lefkowitz RJ. Reciprocal Regulation of Angiotensin Receptor-activated Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinases by β-Arrestins 1 and 2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7807–7811. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luttrell LM, et al. Activation and targeting of extracellular signal-regulated kinases by beta-arrestin scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2449–2454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041604898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MH, El-Shewy HM, Luttrell DK, Luttrell LM. Role of β-Arrestin-mediated Desensitization and Signaling in the Control of Angiotensin AT1a Receptor-stimulated Transcription. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2088–2097. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706892200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang P, et al. Subcellular localization of beta-arrestins is determined by their intact N domain and the nuclear export signal at the C terminus. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11648–11653. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J, et al. A nuclear function of beta-arrestin1 in GPCR signaling: Regulation of histone acetylation and gene transcription. Cell. 2005;123:833–847. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma L, Pei G. Beta-arrestin signaling and regulation of transcription. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:213–218. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson G, et al. Mitogen-Activated Protein (MAP) Kinase Pathways: Regulation and Physiological Functions. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLaughlin NJ, et al. Platelet-activating factor-induced clathrin-mediated endocytosis requires beta-arrestin-1 recruitment and activation of the p38 MAPK signalosome at the plasma membrane for actin bundle formation. J Immunol. 2006;176:7039–7050. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.7039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge L, Ly Y, Hollenberg M, DeFea K. A beta-arrestin-dependent scaffold is associated with prolonged MAPK activation in pseudopodia during protease-activated receptor-2-induced chemotaxis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:34418–34426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhai P, et al. Cardiac-specific overexpression of AT1 receptor mutant lacking G alpha q/G alpha i coupling causes hypertrophy and bradycardia in transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:3045–3056. doi: 10.1172/JCI25330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawamata Y, et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-1 Can Function through a Gαq/11-β-Arrestin-1 Signaling Complex. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28549–28556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Struthers AD. Aldosterone escape during ACE inhibitor therapy in chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1995;16:103–106. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/16.suppl_n.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borghi C, et al. Evidence of a partial escape of rennin-angiotensin-aldosterone blockade in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with ACE inhibitors. J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;33:40–45. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb03901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihailidou AS, Mardini M, Funder JW, Raison M. Mineralocorticoid and Angiotensin Receptor Antagonism During Hyperaldosteronemia. Hypertension. 2002;40:124–129. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000025904.23047.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pezzi V, Clyne CD, Ando S, Mathis JM, Rainey WE. Ca(2+)-regulated expression of aldosterone synthase is mediated by calmodulin and calmodulin-dependent protein kinases. Endocrinology. 1997;138:835–838. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.2.5032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.