Abstract

We provide a representation for the scaling limit of the d = 2 critical Ising magnetization field as a (conformal) random field by using Schramm–Loewner Evolution clusters and associated renormalized area measures. The renormalized areas are from the scaling limit of the critical Fortuin–Kasteleyn clusters and the random field is a convergent sum of the area measures with random signs. Extensions to off-critical scaling limits, to d = 3, and to Potts models are also considered.

Keywords: continuum scaling limit, critical Ising model, FK clusters, SLE, CLE

The Ising model in d = 2 dimensions is perhaps the most studied statistical mechanical model and has a special place in the theory of critical phenomena since the groundbreaking work of Onsager (1). Its scaling limit at or near the critical point is recognized to give rise to Euclidean (quantum) field theories. In particular, the scaling limit of the lattice magnetization field should be a Euclidean random field and, at the critical point, the simplest reflection-positive conformal field theory Φ0 (2, 3). As such, there have been a variety of representations in terms of free fermion fields (4) and explicit formulas for correlation functions (see, e.g., refs. 5 and 6 and references therein). In this article, we provide a construction of Φ0 in terms of random geometric objects associated with Schramm–Loewner Evolutions (SLEs) (7) (see also refs. 8–11) and Conformal Loop Ensembles (CLEs) (12, 13)—namely, a gas (or random process) of continuum loops and associated clusters and (renormalized) area measures.

Two such loop processes arise in the results announced by Smirnov [see refs. 14 and 15, references therein, and also the work of Riva and Cardy (16)—in particular, sections 6 and 7] that the full scaling limit of critical Ising spin cluster boundaries (respectively, FK random cluster boundaries) is given by the (nested version of) CLE with parameter κ = 3 (resp., κ = 16/3). One can try to associate with each continuum cluster Cj* in the scaling limit (or with the outer boundary loop Lj* of Cj* —see section 1) a finite area measure μj* representing the rescaled number of sites in the corresponding lattice cluster (where * is SP for the spin case and FK for the random cluster case). We can in fact do this for the FK case and expect it to also be valid for the spin case.

Although one might try to represent the Euclidean field Φ0 by using spin clusters and a sum , where the χk's are + 1 or − 1 depending on whether CkSP corresponds to a + or − spin cluster, this does not seem to work. Instead, we use the FK clusters, which leads to , where the ηj's are independent random signs. The (countable) family {μjFK} is a “point” process with each μjFK a “point” and where distinct “points” should be orthogonal measures.

For a bounded Λ ⊂ ℝ2 with nonempty interior, one expects that . This would follow from the scaling covariance expected for {μjFK} and described at the end of this section. The same happens for the corresponding measures in independent percolation that count so-called “one-arm” sites, as follows from the work of Garban, Pete, and Schramm, reported in ref. 17. Nevertheless, for any ɛ > 0 only finitely many μjFK's will have support that intersects Λ and has diameter greater than ɛ. Furthermore, with probability one, , which leads to convergence (at least in L2) of the sum with random signs . We note that divergence of means that is not a signed measure; i.e., even restricted to a bounded Λ, it is not the difference of two positive finite measures. For negative results of a similar sort, but in the context of Gaussian random fields, see ref. 18.

In the next section, we set up notation for the Ising model on the square lattice and its FK representation and review how the scaling limit of FK cluster boundaries may be viewed as a process of noncrossing continuum loops LjFK and associated continuum clusters CjFK. We then show why the natural scaling for the Ising spin variables at criticality to obtain a Euclidean (random) field Φ0 leads to natural rescaled area measures μjFK supported on CjFK and to the representation of Φ0 in terms of those measures. We also discuss why area measures μkSP for spin clusters are not appropriate for representing Φ0 by using an example taken from the infinite temperature Ising model on the triangular lattice, 𝕋.

In section 2, we use (see Proposition 2.1) and then discuss how to verify a decay property of the critical Ising 2-point correlation or equivalently the FK connectivity function. Another essential ingredient in our analysis is a bound (see Proposition 2.2) on the number of macroscopic FK clusters. Although we focus on critical Ising-FK percolation on ℤ2, similar arguments can be applied to other lattices and to independent (and, in principle, Ising spin) percolation. The case of independent percolation is discussed at the end of section 2. In section 3, we review the general conclusions of our work and discuss extensions to off-critical (or, as they are sometimes called, near-critical) scaling limits, either as temperature T → Tc, the critical temperature, with magnetic field h = 0, or else as h → 0 with T = Tc. Finally, we propose that a cluster area measure representation should also be valid for the d = 3 Ising model and for the d = 2 q-state Potts model with q = 3 or 4.

Before concluding this section, we wish to emphasize that this article is meant to serve as an introduction, readable by both mathematicians and physicists, to a representation for the Ising scaling limit field Φ0 in terms of the limit rescaled area measures {μjFK}. We hope this will prove useful in providing a general conceptual framework for field-based scaling limits as Aizenman and Burchard (19) did for connectivity-based ones. Although detailed explanations and proofs are provided in this article for certain issues, others are avoided. In particular, although the next 2 sections of the article provide arguments for the existence of both Φ0 and {μjFK} as (subsequence) limits of the corresponding lattice quantities, they do not provide the tools needed to prove that the limits are unique or that they have the expected conformal invariance, including that for α > 0,α1/8Φ0(αz) and {α−15/8μjFK(d(αz))} are equidistributed with Φ0(z) and {μjFK(dz)}.

1. Ising (Euclidean) Field

We consider the standard Ising model on the square lattice ℤ2 with Hamiltonian

where the first sum is over nearest neighbor pairs in ℤ2 (or bonds b = {x,y}), the spin variables Sx are (±1)-valued, and the external field h is in ℝ.

When there is a unique infinite volume Gibbs distribution for some value of h and inverse temperature β = 1/T, we denote by 〈·〉β,h its expectations. There is a critical βc such that nonuniqueness occurs only for h = 0 and β >β c. In particular, the critical Gibbs measure is unique and in that case we use the notation 〈·〉c = 〈·〉βc,0. By translation invariance, the 2-point correlation 〈SxSy〉β,h is a function only of y − x, which in the critical case we denote by τc(y − x).

We want to study the random field associated with the spins on the rescaled lattice aℤ2 in the scaling limit a → 0. More precisely, for test functions f(z) of bounded support on ℝ2, we can define for the critical model

|

with an appropriate choice of the scale factor Θa. Since Φa(f) is a random variable with zero mean, it is natural to choose Θa so that 〈[Φa(f)]2〉c is bounded away from 0 and ∞ as a → 0. Choosing Θa so that this second moment is exactly one when f is the indicator function of the unit square [0,1]2 yields

|

where ΛL,a = [0,L]2 ∩ aℤ2 and ΛL = ΛL,1 = [0,L]2 ∩ ℤ2.

One way to formulate the FK representation of the Ising model (for h = 0 and β ≤ βc) is that coexisting with the (±1) -valued spin variables Sx on the sites x of ℤ2 are {0,1} -valued occupation variables nb on the bonds b = {x,y} of ℤ2. The occupied or open (nb = 1) FK bonds determine FK clusters, Ci, which are the sets of sites x in ℤ2 connected to each other by paths of open FK bonds. One can generate the Sx's from the nb's by assigning independent symmetric ±1 random signs ηi to the Ci's and then setting Sx = ηi for every x in Ci. If we write xy to denote that x and y are in the same FK cluster, it is immediate that the FK connectivity function at criticality is simply given by

Denoting by Ec expectation in the critical system, by Ĉia the restriction of the cluster aCi in aℤ2 to [0,1]2, and by |Ĉia| the number of aℤ2 sites in Ĉia, we have

|

By the definition of Θa we see that the rescaled areas Wia = Θa|Ĉia| are uniformly square summable in the sense that for all a. We would like to argue that, at least along subsequences of a's tending to zero, {Wia} has a nontrivial limit in distribution. This is already partly clear—i.e., no Wia can diverge to +∞. But what prevents them all from tending to zero as a → 0 ? It turns out that this uses the following hypothesis about τc(y − x) (where is the appropriate constant for the lattice ℤ2)—roughly speaking, that it decays like ||y − x||−2θ with θ < 1, where ||·|| denotes the Euclidean norm or that ∑||x||≤r τc(x) diverges as a power when r → ∞. It also uses that the crossing probability of an annulus is bounded away from one as a → 0 — see Eq. 10 and Proposition 2.2. In section 2, we will show that our hypothesis about the decay of τc, like Proposition 2.2, can be verified by using certain bounds of Russo–Seymour–Welsh (RSW) type (20, 21).

Hypothesis 1.1. For some fixed θ < 1, there are constants K1 > 0 and K2 < ∞ such that for any small ɛ > 0 and then for any x ∈ ℤ2 with large ||x||,

for any xɛ ∈ ℤ2 with ||xɛ − ɛx|| ≤ .

As we will discuss, the clusters {Cia = aCi} on the rescaled lattice aℤ2 will converge in the scaling limit to full plane continuum clusters {CjFK} in ℝ2. In that limit most of the lattice clusters disappear because they are not of macroscopic size. The importance of the lower bound on τc(x) in Eq. 4 is that it guarantees (see Proposition 2.1) that the rescaled areas of the microscopic clusters are negligible (at least in a square summable sense). That is, the contribution to coming from clusters Cia, whose intersection with the unit square has small macroscopic diameter, is negligible. A corresponding statement is true for the clusters that contribute to the field Φa(f) for more general test functions f of bounded support. The significance of the upper bound on τc(x) in Eq. 4 is that, together with the lower bound, it easily implies that 〈[Φa(f)]2〉c is bounded away from 0 and ∞ as a → 0.

In a series of articles, the authors constructed a certain process of loops in the plane (22) and proved convergence to it in the scaling limit of the collection of boundaries of all (macroscopic) clusters for critical independent site percolation on the triangular lattice (ref. 23, see also ref. 24). In the limit there is no self-crossing or crossing of different loops but there is self-touching and touching between different loops. Moreover, the loops are locally SLE6 curves.

Similar results for the 2D critical Ising model on the square lattice have been announced by Smirnov (see refs. 14 and 15 and references therein). There one considers either the boundaries between plus and minus spin clusters, or the loops in the medial lattice that separate FK from dual FK clusters (see Fig. 1). We will focus on those loops that separate FK clusters in the original ℤ2 lattice on their inside from dual FK clusters in the dual lattice on their outside. In the scaling limit of spin cluster boundaries one would obtain simple loops that do not touch each other and locally are SLE3-type curves. In the case of FK cluster boundaries, there would instead be self-touching and touching between different loops (but no crossing), like in the percolation case. Now, however, the loops would locally be SLE16/3-type curves.

Fig. 1.

Example of an FK bond configuration in a rectangular region and the associated loops in the medial lattice. Black dots represent sites of ℤ2, black horizontal and vertical edges represent open FK bonds, and the lighter (green) loops are on the medial lattice.We focus on those loops that have ℤ2 sites immediately on their inside.

In the FK case, each loop Lia that we consider on the medial lattice of aℤ2 is the outer boundary of a rescaled FK cluster Cia. The inner boundary of Cia is made of “daughter” loops Li,ka corresponding to the “holes” in Cia. In the scaling limit a → 0, one can analogously identify a continuum cluster CjFK as the closed set left after removing from ℝ2 the (open) exterior of the loop LjFK and the (open) interiors of its daughter loops Lj,nFK (with interiors and exteriors defined by using winding numbers). We remark that because the scaling limit is only a limit in distribution and no special effort was made to coordinate indexing for clusters in the lattice and in the continuum, we use different letters, i and j, for the 2 indices. We denote by {μjFK} the finite measures supported on {CjFK} corresponding to the limit of the rescaled areas {Wia} as a → 0, in the sense, e.g., that {μjFK([0,1]2)} is the scaling limit of the rescaled areas {Wia}. The existence and nontriviality of {μjFK([0,1]2)} [or of for more general test functions f(z) of bounded support] will follow from Hypothesis 1.1 (see Proposition 2.1) and Proposition 2.2, as noted above. The collection {μjFK} ought to be a functional of {LjFK} as has recently been proved in the independent percolation context by Garban, Pete, and Schramm (see ref. 17).

Letting {ηj} denote i.i.d. symmetric (±1)-valued variables, one obtains the following representation of the Euclidean field Φ0: for test functions f(z) of bounded support,

|

To be more precise, the sums in Eq. 5 should first be restricted to clusters with diameter greater than ɛ and then convergence (in L2) as the cutoff ɛ → 0 will follow from the square summability discussed earlier.

As noted in the introduction, one might be tempted to represent the Euclidean field by using spin clusters and hence SLE 3-type loops. If we use {μkSP+} and {μk′SP−} to denote the limits of appropriately rescaled areas of plus and minus spin clusters, respectively, then on a formal level, by decomposing the right-hand side of Eq. 1 into the contribution from plus and minus clusters, one might expect that Φ0 of Eq. 5 would also be given by (with some resummation needed to handle the differences of 2 presumably divergent series) as an alternative to . This appears not to be so, as can be understood by considering the simple situation of the Ising model on the triangular lattice 𝕋 at β = 0.

The latter is a noncritical Ising model and the correct Euclidean field obtained by using the noncritical FK clusters (which are just isolated sites since β = 0) and the β = 0 version of Eq. 2 is 2-dimensional Gaussian white noise. But, if one considers the Ising spin clusters, this is critical independent site percolation on , besides the resummation issue, seems unrelated to white noise. For example, even if applying and then removing a cutoff, as explained after Eq. 5, yielded convergence to some limit, there seems to be no reason it would be the physically correct one.

2. Area Measure

In the previous section we gave a representation of the Ising Euclidean spin field in terms of rescaled counting measures that give the “areas” of macroscopic Ising-FK clusters. In this section we first explain how to use Hypothesis 1.1 to get the existence of nontrivial limits in distribution of these area measures, at least along subsequences of a's tending to zero. We then explain how to verify Hypothesis 1.1, first, for critical Ising-FK percolation on ℤ2, and then, for critical independent site or bond percolation on 𝕋 or ℤ2. Using the notation introduced in section 1 and denoting by diam(Ĉia) the Euclidean diameter of Ĉia, we have the following proposition.

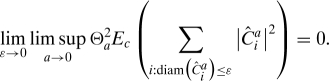

Proposition 2.1. Hypothesis 1.1 implies that

|

The usefulness of Proposition 2.1 is based on the additional result that, for every fixed ɛ, in the scaling limit there will only be finitely many FK clusters with diameter larger than ɛ that intersect [0,1]2; this important feature of the scaling limit will be discussed below—see Proposition 2.2. Once one has Proposition 2.2, it then follows from Proposition 2.1 that the collection {Θa|Ĉia|} has nontrivial subsequential limits; i.e., it is not possible that all Θa|Ĉia|'s scale to zero as a → 0. Said more physically, Proposition 2.1 implies that there is a negligible contribution to the magnetization from FK clusters whose linear size is small on a macroscopic length scale while Proposition 2.2 says that there are only finitely many larger clusters touching any bounded region. Together, they lead to the representation of Eq. 5.

Proof of Proposition 2.1: Using Hypothesis 1.1, we can compare for small ɛ′ as r → ∞ to by using the second inequality of Eq. 4 to compare each τc(z′) to the τc(z)'s with ɛ′z in the unit length square centered on z′ (so that we may take z′ as zɛ′). Since there are approximately (1/ɛ′)2 such z sites, we have that

|

By using this lower bound (with r = 1/2a and ɛ′ = 2ɛ) and Eq. 3, we have that

|

The proposition follows from the observation that the last expression in Eq. 6 tends to zero as ɛ → 0 since θ < 1.

The next 2 lemmas will be used to verify Hypothesis 1.1. Let Bx(r) denote {y ∈ ℤ2 : ||y − x|| ≤ r}, and denote its ℤ2 boundary by ∂Bx(r). If the subscript is omitted, we refer to the disc centered at the origin 0. We denote by P∂B(r)W (W for wired) the critical FK measure inside B(r) with wired (i.e., everything connected) boundary condition on ∂B(r). The next lemma is based on the FKG inequalities.

Lemma 2.1.

|

Proof of Lemma 2.1:

|

where in the last step we have used FKG.

The next lemma uses RSW bounds (20, 21), namely, that the probability pFKa(x;r1,r2) that there is an open FK aℤ2 circuit in an (r1,r2)-annulus centered at x is bounded away from zero and one as a → 0 by constants that depend only on r1/r2. In fact, we only need a lower bound; i.e.,

|

This is not immediate in the Ising case, because there is not currently a direct proof of RSW for critical FK percolation (as opposed to the independent percolation case). However, as we explain after the proof of the lemma, RSW follows from announced results about the scaling limit of spin cluster boundaries (see refs. 14 and 15 and references therein), combined with the Brownian loop soup representation of CLE3 (13, 25, 26); also, the lower bound of Eq. 7 for some r1,r2 implies both upper and lower bounds for all r1,r2.

Lemma 2.2. Assuming Eq.7, there exists a constant K > 0 such that

Before giving the proof, we state an immediate consequence of this lemma, the preceding one and the fact that P∂B(r)W(0∂B(r)) ≥ P(0∂B(r)).

Corollary 2.1. Assuming Eq.7, P(0∂B(||x − y||/3)) and P∂B(||x−y||/3)W(0∂B(||x − y||/3)) are comparable (up to constants) as ||x − y||→∞.

Proof of Lemma 2.2: Let A(x,r) denote the intersection of ℤ2 and the annulus with outer radius r and inner radius r/2 centered at x and let circFK(A(x,r)) denote the event that there is an open FK circuit in Bx(r) surrounding Bx(r/2). Let F(x,r) be the event that circFK(A(x,r)) occurs and the outermost open FK circuit contained in Bx(r) and surrounding Bx(r/2) is connected to x by an open FK path. We have

|

where the second inequality follows from FKG and the constant K″ > 0 follows from RSW. We then note that

|

Inserting this bound into Eq. 8 concludes the proof.

2.1. RSW for FK Percolation on ℤ2.

To get RSW, we will use 2 results that have been announced, but not yet with detailed proofs provided. The first (see refs. 14 and 15 and references therein) is that the “full” scaling limit of the Ising model converges to (the nested version of) CLE3. We then use the representation of CLEκ in terms of the Brownian loop soup (13, 25, 26), including the result that κ = 3 corresponds to a density of the Brownian loop soup below its critical density. This last statement follows from a combination of propositions 2.1 and 3.1 of ref. 13 (see also section 4.3 of ref. 26) and the Sheffield-Werner result that the critical density corresponds to κ = 4 (see ref. 13).

A single Brownian loop has positive probability of “surrounding” a disc of fixed radius r1 centered at the origin. Let γ be such a loop and consider its loop-cluster, built recursively from the (countably many) Brownian loops by saying that any 2 loops that touch (and thus cross, with probability one) are in the same loop-cluster. Given that the density of the Brownian loop soup is below the critical one, the loop-cluster of γ is contained with probability one inside a sufficiently large disc. Thus, for some r2 > r1, there is strictly positive probability that the (r1,r2) -annulus centered at the origin contains a CLE3 circuit. Back on the lattice aℤ2, this gives a positive probability, bounded away from zero as a → 0, that the external boundary of an Ising spin cluster provides such a circuit, but this in turn implies the same for a closed (dual) FK circuit, and hence by self-duality at the critical point, the same for an open FK circuit.

To conclude the discussion of RSW, we note that it is not difficult to show that one can use FKG to obtain from open circuits contained in overlapping (r1,r2)-annuli a “necklace” structure that provides open crossings of rectangles of arbitrary aspect ratio. The rectangle crossings can then be used, once again with the help of FKG, to obtain circuits inside arbitrary annuli with probability bounded away from zero. By self-duality one also has closed (dual) crossings of rectangles and these can be used to bound the probability of open circuits away from one.

Proposition 2.2. For z ∈ ℝ2, let Na(z,r1,r2) denote the number of distinct clusters Cia that include sites in both {y ∈ aℤ2 : ||y − z|| < r1} and {y ∈ aℤ2 : ||y − z|| > r2}. Assuming Eq.7, for any 0 < r1 < r2 < ∞, there exists λ ∈ (0,1) such that for all z ∈ ℝ2 and all small a > 0 and any k = 1,2,… ,

It follows that for any bounded Λ ⊂ ℝ2 and ɛ > 0, the number of distinct clusters Cia of diameter > ɛ touching Λ is bounded in probability as a → 0.

Proof of Proposition 2.2: The proof is by induction on k. For k = 1, the result follows from RSW since Na(z,r1,r2) ≥ 1 is equivalent to the absence of a closed (dual) circuit in the (r1,r2)-annulus about z, which by self-duality at the critical point has the same probability as absence of an open circuit, which in turn is bounded away from one as a → 0. Now suppose Na(z,r1,r2) ≥ k − 1. Then one may do an exploration of the Cia's that touch {y ∈ aℤ2 : ||y − z|| < r1} until k − 1 are found that reach {y ∈ aℤ2 : ||y − z|| > r2}, making sure that all cluster explorations have been fully completed without obtaining information about the outside of the clusters. At that point, the complement D of some random finite Dc ⊂ aℤ2 remains to be explored and the (conditional) FK distribution in D is P∂DF with a free boundary condition on the boundary (or boundaries) between D and Dc. By RSW, the P∂DF probability of an open crossing in D of the (r1,r2)-annulus is bounded above by the original P(Na(z,r1,r2) ≥ 1). Thus we have

|

The last claim of the proposition follows from Eq. 9 because one may choose O([diam(Λ)/ɛ]2) points zℓ in ℝ2 so that any Cia of diameter > ɛ touching Λ will be counted in Na(zℓ,ɛ/4,ɛ/2) for at least one zℓ.

We next explain how to verify Hypothesis 1.1 for critical Ising-FK percolation and for independent percolation; we do not have a verification for Ising spin percolation, although we expect it to be true in that case also. It may be of interest to note that for critical independent percolation, one can obtain a representation like Eq. 5, but with the SLE 16/3-based measures μjFK replaced by SLE6-based ones μjIN, for the scaling limit of the lattice “divide-and-color” model (27). (Here and below we use the letters IN to distinguish independent from FK percolation.) The original divide-and-color model, and the one most analogous to the FK representation of the (h = 0) Ising model, takes the open clusters of independent bond percolation, e.g., on ℤ2, and colors them with random ±1 signs to define the divide-and-color spin variables. In section 3, we will consider this model as the density p of open bonds approaches its critical value (we note that in ref. 28 a different phase transition is studied). For independent site percolation, e.g., on 𝕋, with say probability p and 1 − p for white and black sites, the option for defining the divide-and-color spin variables that we will use is to “color” both the white and black clusters with random signs. It is unclear whether the scaling limit of the critical (p = 1/2 on 𝕋) divide-and-color model corresponds to some known conformal field theory. Note that the limit, in terms of boundaries between clusters of different colors, is a sort of “dilute CLE6” and is conformally invariant, but is not itself described by a CLE since the divide-and-color model lacks the “domain Markov property.”

Hypothesis 1.1 for FK Percolation on ℤ2.

In this case, the behavior of the 2-point function is known exactly along the (1,1) direction from Ising calculations, which yield τc(y − x) ∼ K||x − y||−1/4 (e.g., ref. 29, referred to in ref. 30, and chapter 11 of ref. 5). Using Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2 one obtains that, up to constants, the 2-point function has the same behavior in all directions. Hypothesis 1.1 is then satisfied with 2θ = 1/4.

Hypothesis 1.1 for Independent Percolation.

From the analogues of Lemmas 2.1 and 2.2 for independent percolation, we know that τcIN(z) is comparable (up to constants) with [P(0∂B(||z||/3))]2. This immediately gives the desired upper bound for τcIN(x). For the lower bound, it suffices to show that P(0∂B(r)) ≥ K″′(ɛ′)θP(0∂B(ɛ′r)) for some constant K″′ > 0. Using FKG, we have

|

where ≥ from RSW, and P(∂B(ɛ′r/2)∂B(r)) ≥ (ɛ′)θ with θ = α − δ for any δ > 0, and α denoting the one-arm exponent.

For site percolation on the triangular lattice, α has been proved to be 5/48 by using SLE computations (31). For other percolation models (e.g., bond percolation on the square lattice), the 5-arm exponent is known to be equal to 2 (see lemma 2 of ref. 32, corollary A.8 of ref. 33 and section 5.2 of ref. 34), since it can be derived via a general argument that does not use SLE. Using this and the BK inequality (35), we obtain an upper bound of 2/5 for α. We note, as pointed out to us by P. Nolin, that a more elementary argument from ref. 35 is available showing that α ≤ 1/2 without use of the 5-arm exponent—see equation 2.5 of ref. 36.

3. Discussion

In this article, we provided a representation (see Eq. 5) for the scaling limit Euclidean random field Φ0 associated with the d = 2 Ising model at its critical point (T = Tc, h = 0). This field, one of the basic objects of conformal field theory, is the scaling limit of the magnetization field Φa (see Eq. 1) on aℤ2 as a → 0. Φ0 is represented as a sum with random signs ηj and finite measures μjFK that are the limits of rescaled area measures associated with the macroscopic Ising-FK clusters. These measures are supported on continuum clusters whose outer boundaries are described by CLEκ loops with κ = 16/3. A key to the representation is that natural field strength rescaling (see Eqs. 2 and 3) ensures that for bounded Λ ⊂ ℝ2, and hence is convergent (in L2).

We explained, at the end of section 1, why the limits μjSP of area measures for Ising spin clusters do not appear useful for representing Φ0. We also noted, toward the end of section 2, that a field can be constructed by using critical clusters from independent in place of FK percolation, but that its physical significance is unclear. We next discuss how the representation Eq. 5 could be extended to off-critical models.

Independent percolation, p ≠ pc Here, the percolation density p (say of the white sites on 𝕋) converges to the critical density, pc (= 1/2), appropriately as a → 0. In this case, the representation of the near-critical field should involve area measures from the near-critical modification of CLE6 obtained by the approach of refs. 37 and 38 and the results of Garban, Pete, and Schramm reported in ref. 17. A feature of that work, which might also be valid in the FK-Ising context, is a natural probabilistic coupling, based on a Poissonian marking of certain pivotal locations, so that the one-parameter family of near-critical models parametrized by the strength of the off-critical perturbation lives on a single probability space. The appropriate speed at which p → pc is such that the correlation length is bounded away from zero and infinity. Since it is proved in ref. 39 (and ref. 34, see theorem 26) that crossing probabilities and multiarm probabilities are comparable (up to constants and up to distances of the order of the correlation length) to those of the critical system, RSW still holds and both Hypothesis 1.1 and Proposition 2.2 can be verified. One of the area measures μjIN, corresponding to the unique infinite cluster (white for p ↓ pc and black for p↑pc), will now have unbounded support and infinite mass over ℝ2, but its mass in any bounded region Λ will be finite and will be convergent (in L2, at least for a bounded Λ not chosen in a way that depends on {ηj}). We note that for bond percolation on ℤ2 with p the density of open bonds, it will only be in the p↓pc near-critical model that some μjIN has infinite mass.

FK percolation, T ≠ Tc. Here, one keeps h = 0 in the Ising model, but lets T → Tc appropriately as a → 0, which is the analogue of p → pc in independent percolation. It is natural to expect that the claims made above for independent percolation still hold in this case. Since one is now considering bond (FK) percolation, only for T↑Tc (the analogue of p↓pc in independent percolation) will there be an infinite mass μjFK with unbounded support in ℝ2. Including a random sign ηj for the infinite mass μjFK means one is taking the scaling limit of the symmetric mixture of the plus and minus Gibbs measures.

FK percolation, h ≠ 0. Here one sets T = Tc with h ≠ 0 and then as a → 0 lets h → 0 appropriately [e.g., so that h/(TcΘa) → λ in (0,∞) ]. Intuitively, in the scaling limit, this should involve formally multiplying the measure describing the critical continuum system by a factor proportional to exp(λ ∫ℤ2 Φ0(z)dz). According to Eq. 5 the critical Euclidean field is given by the sum of all the ηjμjFK. Let νFK denote the marginal distribution of the process {ηjμjFK} of finite signed measures in the plane, 1L denote the indicator function of the L × L square in ℝ2, , and finally dνLλ = (ZL)−1exp(λΦ0(1L))dνFK. We ask: does νLλ converge to some νλ as L →∞ and is Φλ0, obtained from νλ as the sum of its individual signed measures, the physically correct near-critical Euclidean field? Heuristically, the correct normalization to obtain a nontrivial near-critical scaling limit is such that the correlation length ξ remains bounded away from zero and infinity. Since ξ ∼ h−8/15 for small h, this gives h ∼ a15/8, which coincides with the normalization needed to obtain a nontrivial Euclidean field, as can be seen from Eq. 2 and the asymptotic behavior of τc. By using this observation and the d = 2 Ising critical exponent δ = 15 for the magnetization (i.e., M ∼ h1/15), the rough computation (where denotes the sum over x in ΛL/a),

|

suggests a positive answer to the previous questions.

We conclude this section with brief discussions of the applicability of our approach to higher dimensions, d > 2, and to q-state Potts models with q > 2. Although the d = 2 scaling limit Ising magnetization field Φ0 should be conformal with close connections to CLE16/3, as we have indicated, very little conformal or SLE machinery was actually used in our analysis. Basically, the two main ingredients were (see Hypothesis 1.1) that τc(y − x) behaves at long distance like ||y − x||−ψ with ψ < d and (see Proposition 2.2) that as a = 1/L′→ 0,

Although such decay of τc should be valid for all d ≥ 2, the crossing probability bound Eq. 10 is a different matter and presumably fails above the upper critical dimension (see appendix A of ref. 40). When it fails, there can be infinitely many FK clusters with diameter greater than ɛ in a bounded region and so Proposition 2.1 would not preclude Φ0 from being a Gaussian (free) field. But it appears that at least for d = 3, both Eq. 10 and a representation of Φ0 as a sum of finite measures with random signs ought to be valid.

An analogous representation for the scaling limit magnetization fields of q -state Potts models also ought to be valid, at least for values of q such that for a given d, the phase transition at Tc is second order. The phase transition is believed to be first order for integer q ≥ 3 when d ≥ 3 and for q > 4 when d = 2 —see ref. 41; this leaves, besides the Ising case, d = 2 and q = 3 and 4. We denote the states or colors by 1,2,…,q and recall that in the FK representation on the lattice, all sites in an FK cluster have the same color while the different clusters are colored independently with each color equally likely. In the scaling limit, there would be finite measures {μjFK,q} and the magnetization field in the color- k direction would be with the ηjk's taking the value +1 with probability 1/q (for the color k) and the value −1/(q − 1) with probability (q − 1)/q (for any other color). For a fixed k the ηjk's would be independent as j varies, but for a fixed j they would be dependent as k varies because .

Acknowledgments.

We thank the Centre de Recherches Mathématiques, Montréal, for hospitality during August 2008 and the Institut Henri Poincaré − Centre Emil Borel, as well as Univ. Paris Sud (C.M.N.) and École Normale Supérieure (F.C.), for hospitality in Paris during October and November, 2008. C.M.N. thanks the department of mathematics of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam for its hospitality during a visit in 2007, when the present work was started and during a visit in 2008. F.C. thanks the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences for its hospitality during two visits in 2008. We thank Douglas Abraham for communications concerning critical Ising two-point functions; John Cardy for suggesting the consideration of Potts models; Michael Aizenman, Vincent Beffara, Oscar Lanford, Pierre Nolin, Oded Schramm, Stas Smirnov, and Alan Sokal for useful conversations; Christophe Garban for discussions about his work with Pete and Schramm; Wouter Kager for providing Fig. 1; and John Cardy and Senya Shlosman for their careful reading of the paper. This work was supported in part by a Veni grant of the Dutch Organization for Scientific Research and by the National Science Foundation Grants DMS-06-06696 and OISE-07-30136.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Onsager L. Crystal statistics. I. A two-dimensional model with an order-disorder transition. Phys Rev. 1944;65:117–149. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belavin AA, Polyakov AM, Zamolodchikov AB. Infinite conformal symmetry in two-dimensional quantum field theory. Nuclear Phys B. 1984;241:333–380. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardy J. Conformal field theory and statistical mechanics. Exact Methods in Low-Dimensional Statistical Physics and Quantum Computing—Les Houches July 2008 Summer School Lectures. 2008;arXiv 0807.3472v1 [cond-mat.stat-mech] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz TD, Mattis DC, Lieb EH. Two-dimensional Ising model as a soluble problem of many fermions. Rev Mod Phys. 1964;36:856–871. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCoy BM, Wu TT. The Two-Dimensonal Ising Model. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmer J. Planar Ising Correlations. Boston: Birkhuser; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schramm O. Scaling limits of loop-erased random walks and uniform spanning trees. Israel J Math. 2000;118:221–288. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardy J. SLE for theoretical physicists. Ann Phys. 2005;318:81–118. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kager W, Nienhuis B. A guide to stochastic Lwner evolution and its applications. J Phys A. 2004;115:1149–1229. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawler GF. Conformally Invariant Processes in the Plane. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society; 2005. Mathematical Surveys and Monographs 114. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Werner W. Lectures on Probability Theory and Statistics. Vol. 1840. Berlin: Springer; 2004. Random planar curves and Schramm-Loewner evolutions; pp. 107–195. Lecture Notes in Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheffield S. Exploration trees and conformal loop ensembles. 2006;arXiv math0609167v2 [math. PR] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werner W. SLEs as boundaries of clusters of Brownian loops. C R Math Acad Sci Paris. 2003;337:481–486. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smirnov S. Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians. Vol. 2. Zurich: European Mathematical Society; 2006. Towards conformal invariance of 2D lattice models; pp. 1421–1451. Madrid 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smirnov S. Conformal invariance in random cluster models. I. Holomorphic fermions in the Ising model. 2007;arXiv 0708.0039v1 [math-ph] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riva V, Cardy J. Holomorphic parafermions in the Potts model and stochastic Loewner evolution. J Stat Mech. 2006 P12001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garban C. Processus SLE et Sensibilit aux Perturbations de la Percolation Critique Plane. Paris: Univ Paris Sud; 2008. Doctoral thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colella P, Lanford O. Appendix: Sample field behavior for the free Markov random field. In: Velo G, Wightman A, editors. Constructive Quantum Field Theory. Vol. 25. Berlin: Springer; 1973. pp. 44–70. Lecture Notes in Physics. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aizenman M, Burchard A. Hlder regularity and dimension bounds for random curves. Duke Math J. 1999;99:419–453. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russo L. A note on percolation. Z Wahrsch Ver Geb. 1978;43:39–48. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seymour PD, Welsh DJA. Percolation probabilities on the square lattice. In: Bollobs B, editor. Advances in Graph Theory. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1978. pp. 227–245. Annals of Discrete Mathematics 3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camia F, Newman CM. Continuum nonsimple loops and 2D critical percolation. J Stat Phys. 2004;116:157–173. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Camia F, Newman CM. Two-dimensional critical percolation: The full scaling limit. Commun Math Phys. 2006;268:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Camia F, Newman CM. SLE6 and CLE6 from critical percolation. In: Pinsky M, Birnir B, editors. Probability, Geometry and Integrable Systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008. pp. 103–130. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawler G, Werner W. The Brownian loop soup. Probab Theory Relat Fields. 2004;128:565–588. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner W. Some recent aspects of random conformally invariant systems. In: Bovier A, Dunlop F, van Enter A, den Hollander F, Dalibard J, editors. Mathematical Statistical Physics—Les Houches July 2005 Summer School Lectures. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2005. pp. 57–99. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Häggström O. Coloring percolation clusters at random. Stoch Proc Appl. 2001;96:213–242. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bálint A, Camia F, Meester R. Sharp phase transition and critical behaviour in 2D divide and color models. 2007;arXiv 0708.3349v1 [math.PR] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu TT. Theory of Toeplitz determinants and the spin correlations of the two-dimensional Ising model. I. Phys Rev. 1966;149:380–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tracy C. Asymptotics of a τ -function arising in the two-dimensional Ising model. Commun Math Phys. 1991;142:297–311. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawler G, Schramm O, Werner W. One arm exponent for critical 2D percolation. Electr J Probab. 2002;7 paper 2. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kesten H, Sidoravicius V, Zhang Y. Almost all words are seen in critical site percolation on the triangular lattice. Electr J Probab. 1998;3 paper 10. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schramm O, Steif J. Quantitative noise sensitivity and exceptional times for percolation. 2007;arXiv math/0504586v2 [math.PR] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nolin P. Near-critical percolation in two dimensions. Electr J Probab. 2008;13:1562–1623. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van den Berg J, Kesten H. Inequalities with applications to percolation and reliability. J Appl Probab. 1985;22:556–569. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chayes L, Nolin P. Large scale properties of the IIIC for 2D percolation. 2007;arXiv 0705.3570v1 [math.PR] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Camia F, Fontes LR, Newman CM. The scaling limit geometry of near-critical 2D percolation. J Stat Phys. 2006;125:1155–1171. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Camia F, Fontes LR, Newman CM. Two-dimensional scaling limits via marked nonsimple loops. Bull Braz Math Soc. 2006;37:537–559. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kesten H. Scaling relations for 2D-percolation. Commun Math Phys. 1987;109:109–156. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aizenman M. On the number of incipient spanning clusters. Nuclear Phys B. 1997;485:551–582. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu FY. The Potts model. Rev Mod Phys. 1982;54:235–268. [Google Scholar]