Abstract

Human 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase type 1 (3β-HSD1) is a critical enzyme in the conversion of DHEA to estradiol in breast tumors and may be a target enzyme for inhibition in the treatment of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Human 3β-HSD2 participates in the production of cortisol and aldosterone in the human adrenal gland in this population. In our recombinant human breast tumor MCF-7 Tet-off cells that express either 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2, trilostane and epostane inhibit the DHEA-induced proliferation of MCF-7 3β-HSD1 cells with 12-to 16- fold lower IC50 values compared to the MCF-7 3β-HSD2 cells. The compounds also competitively inhibit purified human 3β-HSD1 with 12- to 16-fold lower Ki values compared to the noncompetitive Ki values measured for human 3β-HSD2. Using our structural model of 3β-HSD1, trilostane or 17β-acetoxy-trilostane was docked in the active site of 3β-HSD1, and Arg195 in 3β-HSD1 or Pro195 in 3β-HSD2 was identified as a potentially critical residue (one of 23 nonidentical residues in the two isoenzymes). The P195R mutant of 3β-HSD2 were created, expressed and purified. Kinetic analyses of enzyme inhibition suggest that the high-affinity, competitive inhibition of 3β-HSD1 by trilostane and epostane may be related to the presence of Arg195 in 3β-HSD1 vs Pro195 in 3β-HSD2.

Keywords: 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, breast cancer, MCF-7 tumor cell, enzyme inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

In human breast cancer, circulating dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) from the adrenal gland is converted by steroid sulfatase, 3β-HSD1, aromatase and 17β-HSD in the tumors and the surrounding normal mammary gland tissue to produce estradiol-17β. In addition, estrone-sulfate is converted to estradiol-17β by steroid sulfatase and 17β-HSDs (Labrie et al., 1992; Pasqualini & Chetrite, 2002; Reed & Purohit, 1997; Ghosh & Vihko, 2002). Inhibitors specific for 3β-HSD1 in mammary gland and breast tumors may inhibit tumor cell growth without affecting the activity of 3β-HSD2 in the adrenal gland (Gingras et al., 1999; Thomas et al., 2004, 2005). To test that hypothesis, we have developed two recombinant (genetically engineered) human breast tumor MCF-7 cell lines that express either human 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 as well as each of the other enzymes required for the biosynthesis of estradiol from DHEA-S. As the first aim of this study, the efficacies of inhibitors of 3β-HSD1 and aromatase are compared as blockers of MCF-7 cell proliferation.

The introduction of aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole) has improved the prognosis of many breast cancer patients (Santen et al., 1997, Winer et al., 2004). Because aromatase inhibitors produce increased fractures in 60% of the treated breast cancer victims (Eastell & Hannon, 2005), it is important to evaluate other enzymes as targets for inhibition in the biosynthetic pathway of estradiol in breast tumors that may result in a lower incidence of bone loss. Primary human osteoblast cells were shown to be unable to metabolize DHEA to estradiol (Kasperk et al, 1997), suggesting that 3β-HSD is not a key enzyme, like aromatase, in the production of estradiol in bone.

A second aim of this study is to determine the functional significance of a non-identical amino acid in the active site of the isoenzymes- Arg195 in 3β-HSD1 vs Pro195 in 3β-HSD2. Docking studies of trilostane with our structural model of human 3β-HSD1 predicts that the 17β-hydroxyl group of the 3β-HSD inhibitor, trilostane (2α-cyano-4α,5α-epoxy-17β-ol-androstane-3-one), may interact with the Arg195 residue of 3β-HSD1. An analog of trilostane with a modified 17β-hydroxyl group, 17β-acetoxy-trilostane, has been synthesized, and docking of this analog with 3β-HSD1 has also been performed. To test this prediction for the role of Arg195, the Pro195Arg mutation of 3β-HSD2 (P195R-2) has been created, expressed and purified for kinetic analyses of enzyme inhibition by trilostane and 17β-acetoxy-trilostane.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S), androstenedione, estradiol, estrone, 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO); reagent grade salts, chemicals and analytical grade solvents from Fisher Scientific Co. (Pittsburg, PA). The cDNA encoding human 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and aromatase was obtained from J. Ian Mason, Ph.D., Univeristy of Edinburgh, Scotland. Trilostane was obtained as gift from Gavin P. Vinson, DSc PhD, School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary University of London. Epostane was obtained from Sterling-Winthrop Research Institute (Rensselaer, NY). Letrozole was obtained from Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland). Glass distilled, deionized water was used for all aqueous solutions.

Western blots of the MCF-7 cells

Homogenates of the MCF-7 cells were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide (12%) gel electrophoresis, probed with our anti-3β-HSD polyclonal antibody (Thomas et al., 1998), anti-aromatase or anti-steroid sulfatase polyclonal antibody (both obtained from Dr. Debashis Ghosh, Hauptmann-Woodward Medical Research Instititute, Buffalo, NY) or anti-17β-HSD1 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and detected using the ECL western blotting system with anti-rabbit or anti-goat peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) of the recombinant MCF-7 cells

Total RNA was isolated from the untransfected and recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off cell lines using the RNeasy Mini Kit, followed by Deoxyribonuclease I treatment (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Single-strand cDNA was prepared from 2 ug of total RNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 primers and probes were used because of 93% sequence homology. Primers and probes specific for human 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and aromatase used in these qRT-PCR studies were described previously (Havelock et al., 2006). 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and 18s rRNA quantification were performed using Applied Biosystems TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix. For aromatase quantification, SYBR Green I was used with Applied Biosystems Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix. The cDNA product from 40 ng total RNA was used as template. Plasmids containing human cDNA for 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and aromatase were used as template to generate standard curves for absolute quantification of the respective mRNA transcripts by qRT-PCR. The identity of each clone was confirmed by sequence analysis. All qRT-PCR were performed in triplicate in 30 ul reaction volume in 96-well optical reaction plates using the Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR system and the dissociation protocol. The qRT-PCR were carried out in two steps: Step 1: 50°C for 2 min followed by 95°C for 10 min, one cycle. Step 2: 95°C for 15 s, followed by 60°C for 60 s, 40 cycles. All samples were normalized with 18s rRNA as internal standard using the following protocol. The untransfected Clontech MCF-7 Tet-off cells were used to isolate total RNA, then reverse transcriptase was used to obtain cDNA as the control 18s rRNA real-time PCR template to generate standard curves for absolute quantification of 18s rRNA. Human 18s rRNA primers and probe from Pre-Developed TaqMan Assay Reagents (Applied Biosystems) were used. Each gene mRNA expression level was calculated using the formula: ((attograms of gene mRNA measured by qRT-PCR relative to the cDNA standard curve)/(gene mRNA molecular weight))/(μg of control 18s rRNA) = attomoles of gene mRNA per μg 18s rRNA in Table 1.

Table 1.

Levels of 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and aromatase mRNA in our recombinant human breast tumor MCF-7 Tet-off cells.

| MCF-7 cell line | 3β-HSD11 am/μg RNA | 3β-HSD2 am/μg RNA | Aromatase am/μg RNA |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 Tet-off | 27 | 2 | 2 |

| MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 | 150219 | 11 | 1 |

| MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 Aromatase | 108804 | 3 | 43186 |

| MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 Aromatase Dox | 5780 | 3 | 43405 |

| MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 | 35 | 138511 | 2 |

| MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 Aromatase | 9 | 220804 | 40098 |

| MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 Aromatase Dox | 30 | 2693 | 40693 |

Primers and probes specific for human 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and aromatase were used in these qRT-PCR studies. The mRNA level for each gene was normalized as attomoles (am)/μg of control 18s rRNA as described in Experimental Procedures. The qRT-PCR measurements were performed in triplicate.

Proliferation assays using the MCF-7 cells

The Clontech MCF-7 Tet-Off cells transfected with the Tet-Off expression vector allows controlled expression of the human 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2. The Clontech response plasmid, pTRE2hyg, containing cDNA encoding 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 was transfected into the MCF-7 Tet-Off cells, and transfected clones were selected by incubation with hygromycin. In this stably transfected expression system, human 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 is produced in the MCF-7 cells, and the levels of 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 expression are maximal in the absence of doxycycline. In addition, the cDNA encoding human aromatase was cloned into the pCMVzeo mammalian expression vector, and the MCF-7 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 cells were stably tranfected with the aromatase gene, and transfected clones were selected by incubation with zeocin. These recombinant MCF-7 cells are plated in 96-well dishes (2000 cells/well) using RPMI medium without phenol red containing 10% charcoal dextran stripped FBS (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA).

Stimulation of the growth of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells by the 3β-HSD substrate, DHEA (0.2 pM-2.0 μM), and by the steroid sulfatase substrate, DHEA-S (0.3 nM-5.0 μM) was measured in the presence (dox) and absence (no dox) of doxycycline (10 ng/ml). In addition, estrone and estradiol (each at 0.2 pM-2.0 μM) were incubated with the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells to compare proliferation rates. The ER-antagonist, 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (0.1–10.0 nM), was also used in DHEA-stimulated (5 nM) proliferation assays of the recombinant MCF-7 cells. To measure inhibition of 3β-HSD, the substrate, DHEA (5.0 nM, EC50), and the 3β-HSD inhibitor, trilostane (0–2.5 μM) or epostane (0–20.0 μM), are added to the cultures. To measure inhibition of aromatase, the substrate steroid, DHEA (5.0 nM), and the aromatase inhibitor (letrozole, 0–20.0 nM) are added to the cultures. For each of these procedures, the hormones are introduced 48 h after the plates are seeded with the cells. After 4 days, the treatments and media are refreshed. On day 10 after cell plating, the MTT dye is added to measure a viable cell count by colorimetric assay (absorbance at 595 nm). Our standard curves determined that an increase or decrease in 0.1 absorbance units at 595 nm measures an increase or decrease of 8,000 MCF-7 cells in each well of the 96-well plate that hold 20,000 MCF-7 cells at confluency. Each value reported is the mean of 4 independent determinations ± SD.

Bioinformatics/Computational Biochemistry/Graphics

As described previously (Pletnev et al., 2006), a three dimensional model of human 3β-HSD1 has been developed based upon X-ray structures of two related enzymes: the ternary complex of E-coli UDP-galactose 4-epimerase (UDPGE) with an NAD+ cofactor and substrate (PDB AC: 1NAH) (Thoden et al., 1996) and residues 154-254 of the ternary complex of human 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD1) with NADP and androstenedione (PDB AC: 1QYX) [Shi & Lin, 2004].

Using this PDB file for 3β-HSD1 in Autodock 3.0 (The Scripps Research Institute, http://autodock.scripps.edu), the steroid ligand was removed, leaving the NAD+ co-factor in the binding site. All docking experiments were carried out on Autodock 3.0 using the Genetic Algorithm with Local Searching. Independent runs (256) were carried out and the docking results were then analyzed by a ranked cluster analysis. Compounds were identified that had the lowest overall binding energy. The three-dimensional images of the enzyme docked with trilostane or 17β-acetoxy-trilostane in Figures 8 and 9 were created using the DeepView/Swiss-Pdb Viewer (http://www.exspasy.org/spdbv/).

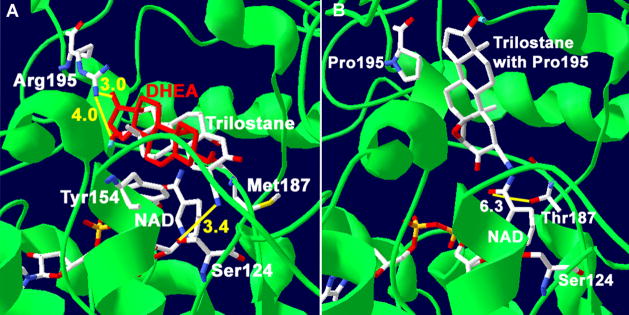

Figure 8.

(A) Docking of trilostane with our structural model of human wild-type 3β-HSD1 shows the predicted interactions between the 17β-hydroxyl group of trilostane (4.0 Å in yellow) and the 17-keto of DHEA (3.0 Å) with Arg195 and between the 2α-cyanogroup of trilostane and Ser124 residue of the wild-type enzyme (3.4 Å). The overlapping of DHEA (red) and trilostane is consistent with a competitive mode of inhibition. The catalytic Tyr154 and Met187 of 3β-HSD1 are also shown. (B) Docking of trilostane with the P195R mutant of 3β-HSD1 (with Pro195) reveals a binding shift for trilostane. In addition, the interaction between the nicotinamide carbonyl of NAD+ and Thr187 of the M187T mutant enzyme (6.3 Å) is shown. The protein backbone (green), carbon (white), oxygen (red) and nitrogen (blue) atoms are indicated.

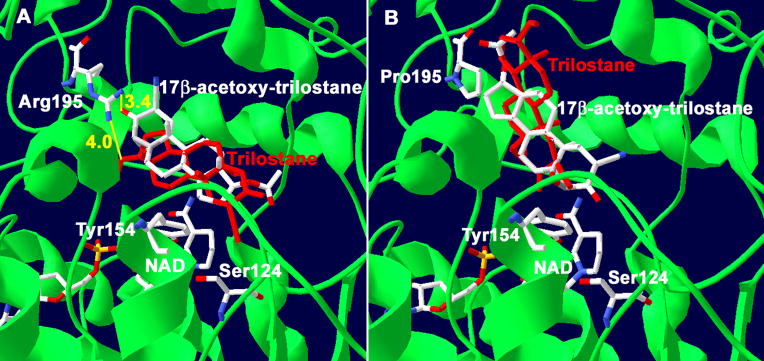

Figure 9.

(A) Docking of 17β-acetoxy-trilostane with our structural model of human wild-type 3β-HSD1 shows the predicted interactions between the 3-keto group of 17β-acetoxy-trilostane (3.4 Å in yellow) with Arg195. 17β-Acetoxy-trilostane is flipped 180° relative to trilostane (red). The catalytic Tyr154 and Ser124 of 3β-HSD1 are also shown. (B) Docking of 17β-acetoxy-trilostane with the P195R mutant of 3β-HSD1 (with Pro195) reveals that 17β-acetoxy-trilostane is not flipped 180° and aligns with trilostane. The protein backbone (green), carbon (white), oxygen (red) and nitrogen (blue) atoms are indicated.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Using the Advantage cDNA PCR kit (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and pGEM-3βHSD1 as template (Thomas et al., 2002), double-stranded PCR-based mutagenesis was performed with the primers listed below to create the cDNA encoding the P195R-2 mutant of human 3β-HSD2. The forward and reverse primers (mutated codons underlined) used to produce the P195R-2 mutant cDNA were: 5′-AGGAGGCCGATTCCTTTCTGCCAG-3′; 5′-AAGGAATCGGCCTCCTTCCCCATA-3′, respectively. The presence of the mutated codon and integrity of the entire mutant 3β-HSD cDNA were verified by automated dideoxynucleotide DNA sequencing using the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Expression and purification of the mutant and wild-type enzymes

The mutant P195R-2, wild-type 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 cDNA was introduced into baculovirus and expressed in Sf9 cells as previously described (Thomas et al., 1998). Recombinant baculovirus was added to 1.5 × 109 Sf9 cells (1L) at a multiplicity of infection of 10 for expression of each mutant enzyme. The expressed mutant and wild-type enzymes were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide (12%) gel electrophoresis, probed with anti-3β-HSD polyclonal antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) and detected using the ECL western blotting system with anti-goat, peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ). Each expressed enzyme was purified from the 100,000 g pellet of the Sf9 cells (4 L) by our published method (Thomas et al., 1989) using Igepal CO 720 (Rhodia, Inc., Cranbury, NJ) instead of the discontinued Emulgen 913 detergent (Kao Corp, Tokyo). Each expressed, purified mutant and wild-type enzyme produced a single major protein band (42.0 kDa) on SDS-polyacrylamide (12%) gel electrophoresis that co-migrated with the purified human 3β-HSD1 control enzyme. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method using bovine serum albumin as the standard (Bradford, 1976).

Synthesis of the trilostane analog

17β-Acetoxy-trilostane was synthesized by reacting trilostane with acetic anhydride using pyridine as a catalyst in ethanol as previously described (Thomas et al., 1990). Silica gel thin-layer chromatography (benzene-ethyl acetate, 92:8, v/v) gave a single spot (Rf = 0.33) that migrated farther than the starting steroid, trilostane (Rf = 0.09). Infrared (IR) spectroscopy (KBr) verified the loss of the 17β-hydroxyl group (3400 cm−1) and gain of the 17β-acetoxy group (1730 cm−1). These values plus the presence of the 2α-cyano group (2200 cm−1) and 3-keto group (2200 cm−1) were identical to those as previously reported for trilostane and its analogs (Christiansen et al. 1984). Trilostane (2α-cyano-4α,5α-epoxy-17β-ol-androstane-3-one) was obtained as gift from Gavin P. Vinson, DSc PhD, School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary University of London.

Kinetic studies

Michaelis-Menten kinetic constants for the 3β-HSD substrate were determined for the purified mutant and wild-type enzymes in incubations containing dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA, 2–100 μM) plus NAD+ (0.2 mM) and purified enzyme (0.03 mg) at 27°C in 0.02 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4,. The slope of the initial linear increase in absorbance at 340 nm per min (due to NADH production) was used to determine 3β-HSD1 activity. Kinetic constants for the isomerase substrate were determined at 27°C in incubations of 5-androstene-3,17-dione (20–100 μM), with or without NADH (0.05 mM) and purified enzyme (0.02 mg) in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. Isomerase activity was measured by the initial absorbance increase at 241 nm (due to androstenedione formation) as a function of time. Blank assays (zero-enzyme, zero-substrate) assured that specific isomerase activity was measured as opposed to non-enzymatic, “spontaneous” isomerization (Thomas et al., 1989). Changes in absorbance were measured with a Varian (Sugar Land, TX) Cary 300 recording spectrophotometer. The Michaelis-Menten constants (Km, Vmax) were calculated from Lineweaver-Burke (1/S vs. 1/V) plots and verified by Hanes-Woolf (S vs. S/V) plots. The kcat values (min−1) were calculated from the Vmax values (nmol/min/mg) and represent the maximal turnover rate (nmol product formed/min/nmol enzyme dimer).

Kinetic constants for the 3β-HSD cofactor were determined for the purified mutant and wild-type enzymes in incubations containing NAD+ (10–200 μM), DHEA (100 μM) and purified enzyme (0.03 mg) in 0.02 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, at 27°C using the spectrophotometric assay at 340 nm. Kinetic constants for the isomerase cofactor as an allosteric activator were determined in incubations of NADH (0–50 μM), 5-androstene-3,17-dione (100 μM) and purified enzyme (0.02 mg) in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 at 27°C using the spectrophotometric assay at 241 nm. Zero-coenzyme blanks were used as described above for the substrate kinetics.

Inhibition constants (Ki) were determined for the inhibition of the 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and R195P-2 activities by trilostane and 17β-acetoxy-trilostane using conditions that were appropriate for each enzyme species based on substrate Km values. For 3β-HSD1, the incubations at 27 °C contained sub-saturating concentrations of DHEA (4.0 μM or 8.0 μM), NAD+ (0.2 mM), purified human type 1 enzyme (0.03 mg) and trilostane (0–0.75 μM) or 17β-acetoxy-trilostane (0–10.0 μM) in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. For 3β-HSD2, similar incubations contained DHEA (8.0 μM or 20.0 μM) and trilostane (0–10.0μM) or 17β-acetoxy-trilostane (0–10.0 μM). For R195P-2, similar incubations contained DHEA (8.0 μM or 20.0 μM) and trilostane (0–1.0 μM) or 17β-acetoxy-trilostane (0–7.5 μM). Dixon analysis (I versus 1/V) was used to determine the type or mode of inhibition (competitive, noncompetitive) and calculate the inhibition constant (Ki) values. The Ki value represents the inhibitor concentration that reduces maximal enzyme activity by 50% and is considered a measure of the affinity of the enzyme for the inhibitor. A decrease in Ki indicates an increase in affinity (Segel, 1993).

Our triplicate determinations of the kinetic constants used highly purified mutant and wild-type enzymes to produce very reliable results with little variation between the values. The standard deviations reported for the mean values in the kinetic tables show that the variation between triplicates is 5% – 9%. With such low variation in the kinetic determinations, the observed differences of 2- to 16-fold between the kinetic constants of mutant and wild-type enzymes for substrates, cofactors and inhibitor analogs are interpreted to represent real differences.

RESULTS

Western blots of the recombinant MCF-7 cells and the P195R-2 mutant of 3β-HSD2

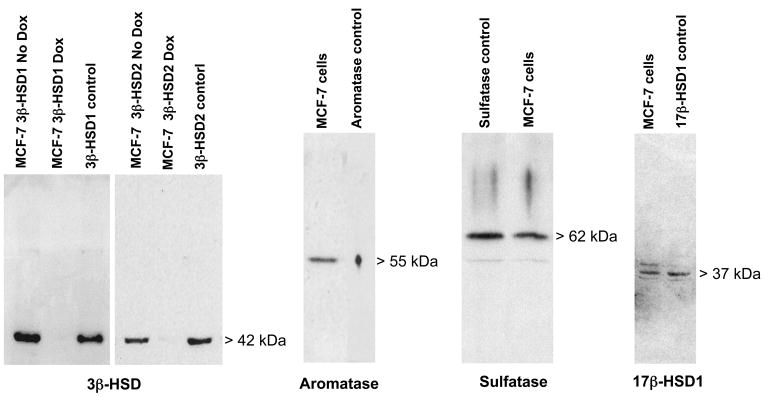

The outcome of transfecting the Clontech MCF-7 Tet-off cells with pTRE2hyg-3βHSD1 or pTRE2hyg-3βHSD2 and pCMVzeo-aromatase were evaluated using our polyclonal antibodies that recognize human 3β-HSD or aromatase (Figure 1). There is a positive protein band of the correct molecular size for each of these enzymes, which indicates that 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 and aromatase are present in the stably transfected MCF-7 cell homogenates. Doxycycline turns off the expression of transfected 3β-HSD as expected. Using our anti-steroid sulfatase and anti-17β-HSD1 antibodies, human steroid sulfatase and 17β-HSD1 were also determined to be present as endogenous enzymes in the MCF-7 cells (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Western blots show that our MCF-7 cell homogenates (20 ug) express 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2 and aromatase proteins in the transfected MCF-7 Tet-off cells and express endogenous steroid sulfatase and 17β-HSD1 in the untransfected MCF-7 Tet-off cells. Doxycycline (Dox, 10 ng/ml) suppresses the expression of the transfected 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2. The MCF-7 cell homogenates were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide (12 %) gel electrophoresis. The protein band of each enzyme was detected using antibodies specific for human 3β-HSD, aromatase, steroid sulfatase or 17β-HSD1 as described in the text.

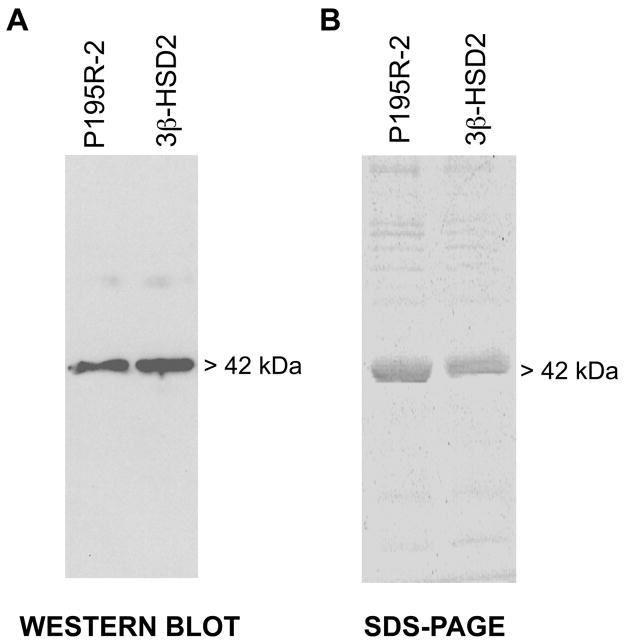

As shown by the western blot in Figure 2A, the baculovirus system successfully expressed a single protein of the P195R mutant of 3β-HSD2 (P195R-2) that co-migrates with the parent wild-type 3β-HSD2 in the Sf9 cells. The expressed P195R-2 mutant enzyme (42 kDa monomer) was highly purified (90–95%) according to protein bands visible in SDS-PAGE (Figure 2B) using our published method (Thomas et al., 1989).

Figure 2.

(A) Western blots of the expressed P195R-2 mutant and wild-type enzyme. The Sf9 cell homogenates (4.0 μg) containing P195R-2 or the purified control wild-type 3β-HSD2 (0.05 μg) were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide (12%) gel electrophoresis. The 42.0 kDa band of the enzyme monomer was detected using anti-3β-HSD antibody as described in the text. (B) SDS-Polyacrylamide (12%) gel electrophoresis of the purified P195R-2 and wild-type enzyme. Each lane was overloaded with 4.0 μg of purified protein, and the bands were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining.

qRT-PCR of enzyme levels in the recombinant MCF-7 cells

The key to measuring the specificity of inhibitors for 3β-HSD1 in proliferation assays using our recombinant MCF-7 cells is validation that our MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells express no human 3β-HSD2 and the MCF-7 tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells express negligible endogenous human 3β-HSD1. Our qRT-PCR results shown in Table 1 provide definitive evidence that our recombinant MCF-7 cells meet these criteria. In addition, doxycycline (Dox) turns off (56- to 82-fold decrease) the expression of 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 (as expected for stable transfection using the Clontech Tet-off response plasmid, pTRE2hyg). Table 1 also shows that the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 cell lines have been stably transfected with human aromatase, which is not affected by Dox as expected for stable transfection with pCMVzeo-aromatase. As shown by the qRT-PCR results in Table 1, the Clontech Tet-off MCF-7 cells express no endogenous aromatase mRNA and required transfection with pCMVzeo-aromatase to provide this enzyme activity.

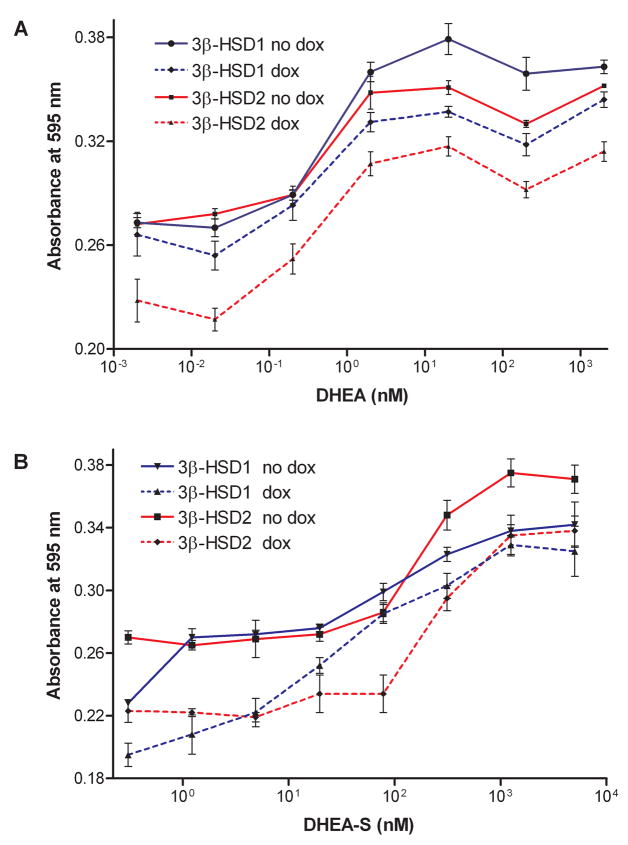

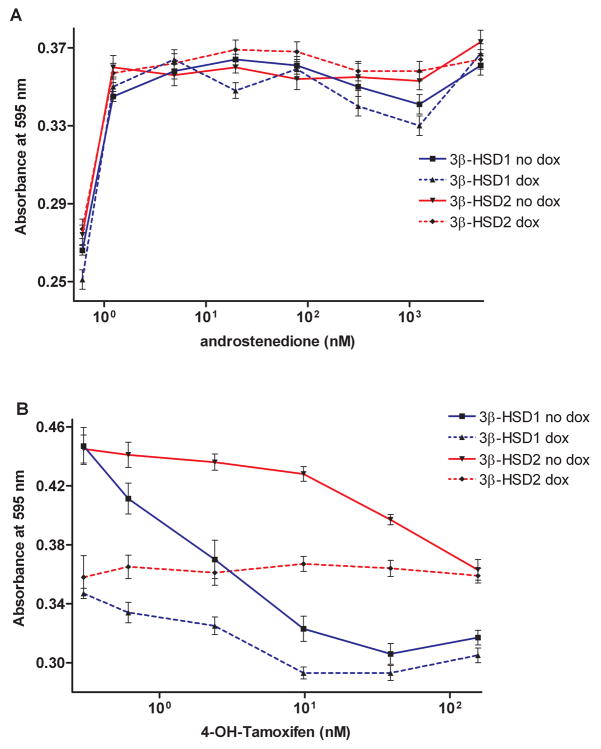

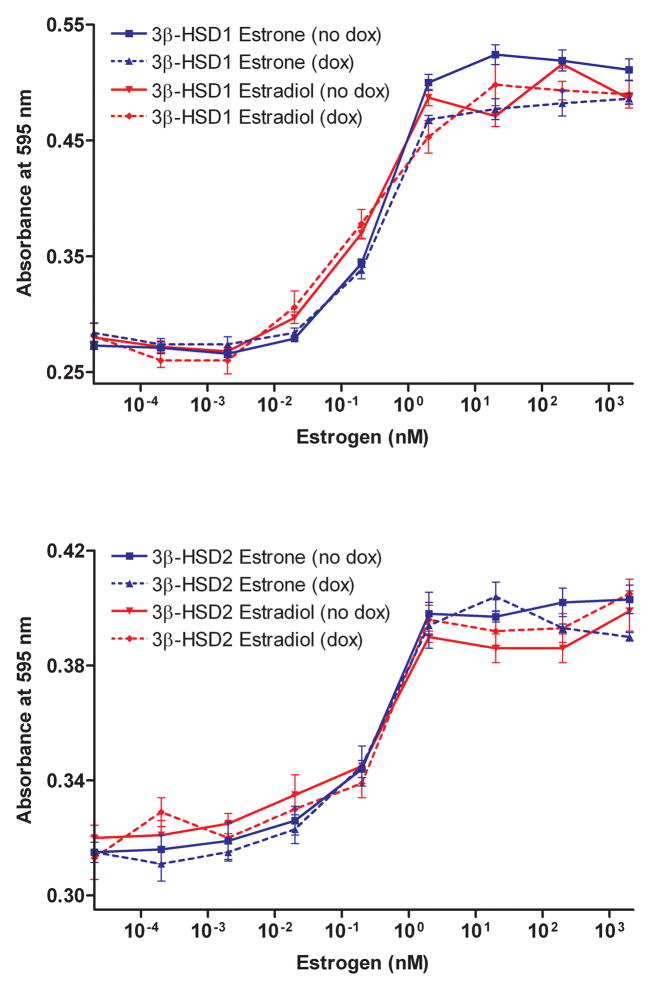

DHEA, DHEA-S, estrone and estradiol stimulate proliferation of the recombinant MCF-7 cells

As shown in Figure 3A, the growth of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells are stimulated by the 3β-HSD substrate, DHEA, in a concentration-dependent manner when 3β-HSD expression was turned on (no Dox), and the growth response was less dramatic when 3β-HSD expression was turned off (Dox). In Figure 3B, the growth of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells are stimulated by the steroid sulfatase substrate, DHEA-S, in a concentration-dependent manner. Androstenedione also stimulates the proliferation of both recombinant MCF-7 cell lines, and the addition of doxycycline does not affect the rate of proliferation as expected for the MCF-7 cells stably transfected with pCMVzeo-aromatase (Figure 4A). Stimulation of cell growth by the appropriate substrates supports the presence of active 3β-HSD1, 3β-HSD2, aromatase and steroid sulfatase in the MCF-7 Tet-off cells. The ER-antagonist, 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen, decreases the DHEA-stimulated proliferation of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that estradiol is produced in the recombinant cells (Figure 4B). The presence of doxycycline decreases antagonism of DHEA-stimulated growth in both cells, which is consistent with the expression of 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2 being turned-off by this tetracycline (Figure 4B). In addition, estrone (EC50 = 0.39 nM) or estradiol (EC50 = 0.24 nM) stimulates growth of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase and of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells (estrone EC50 = 0.34 nM; estradiol EC50 = 0.32 nM)) at very similar rates, which indicates that endogenous 17β-HSD reductase activity is present in the parent Clontech MCF-7 Tet-off cells (Figure 5). As expected, the presence of doxycycline had no effect on the proliferation of the MCF-7 Tet-off cells by either of the estrogens.

Figure 3.

(A) DHEA (0.2 pM-2.0 μM) stimulates the proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ●, solid line) and presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line) and of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line) as described in Experimental Procedures. (B) The steroid sulfatase substrate, DHEA-S (0.3 nM- 5.0 μM) stimulates the proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) and presence of doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line) and of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line). Each value is the mean of 4 independent determinations ± SD.

Figure 4.

(A) Androstenedione (1.2 pM-5.0 μM) stimulates the proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) and presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line) and of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line) as described in Experimental Procedures. (B) The estrogen receptor antagonist, 4-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4-OH-Tamoxifen, 0–156 nM) was incubated with DHEA (5 nM) to measure its effect on the DHEA-stimulation of growth of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) and presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line) and of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line) as described in Experimental Procedures. Each value is the mean of 4 independent determinations ± SD.

Figure 5.

(A) Estrone (0.2 pM-2.0 μM) stimulates the proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) and presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line), and estradiol (0.2 pM-2.0 μM) stimulates the growth of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line). (B) Estrone (0.2 pM-2.0 μM) stimulates the proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) and presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line), and estradiol (0.2 pM-2.0 μM) stimulates the growth of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line) as described in Experimental Procedures. Each value is the mean of 4 independent determinations ± SD.

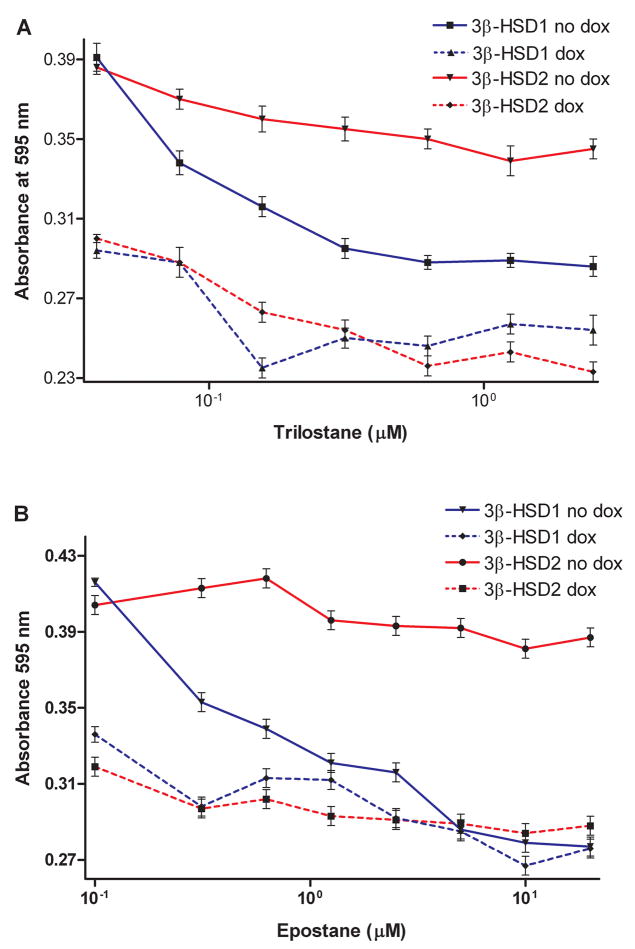

Inhibition of 3β-HSD1 or aromatase slows the growth of the MCF-7 cells

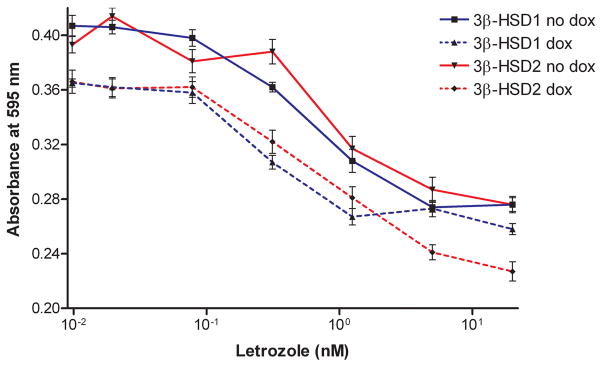

As shown in Figure 6A, the 3β-HSD inhibitor, trilostane, slows the proliferation of our MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells (IC50= 0.3 μM) with a 16-fold higher affinity compared to the MCF7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells (IC50= 4.9 μM). In Figure 6B, the related 3β-HSD inhibitor, epostane, also selectively inhibits the growth of our MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells (IC50= 0.2 μM) with a 12-fold higher affinity relative to the MCF7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells (IC50= 2.4 μM). When doxycycline (dox) is present to turn-off the expression of 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2, the basal stimulation of proliferation by substrate (DHEA at 5.0 nM, mean EC50 measured in Figure 3) is substantially reduced, and the inhibition of the growth of both MCF-7 cell lines by trilostane is greatly attenuated. These results mirror the inhibition of 3β-HSD1 by trilostane or epostane with 12- to 16-fold higher affinity than 3β-HSD2 that was measured with the purified isoenzymes as well as in homogenates of our recombinant MCF-7 3β-HSD1 and MCF-7 3β-HSD2 cells (Thomas et al. 2004, 2005, 2008). In Figure 7, the aromatase inhibitor, letrozole, inhibits the DHEA-stimulated proliferation of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase (IC50= 0.6 nM) and MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase (IC50= 0.9 nM) cell lines at similar rates, as expected for the inhibition of aromatase in these cells. Neither trilostane, epostane nor letrozole stimulated the proliferation of the MCF-7 cells in the absence of DHEA substrate, so none of these compounds has ER-agonist activity in our breast tumor cell model.

Figure 6.

(A) The 3β-HSD inhibitor, trilostane (0–2.5 μM) slows the DHEA-stimulated (5 nM) proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) and presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line) and recombinant MCF7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) and presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line). (B) The related 3β-HSD inhibitor, epostane (0–20.0 μM), inhibits the DHEA-stimulated (5 nM) proliferation of our recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) and presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line) and recombinant MCF7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ●, solid line) and presence of doxycycline (dox, ■, broken line). For both 3β-HSD inhibitors, the presence of doxycycline turns-off the expression of 3β-HSD1 or 3β-HSD2. Assays are conducted as described in Experimental Procedures. Each value is the mean of 4 independent determinations ± SD.

Figure 7.

The aromatase inhibitor, letrozole (0–20.0 nM), decreases the DHEA-stimulated (5 nM) proliferation of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells in the absence (no dox, ■, solid line) or presence of 10 ng/ml doxycycline (dox, ▲, broken line) and of the recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD2 aromatase cell lines in the absence (no dox, ▼, solid line) or presence of doxycycline (dox, ◆, broken line) as described in Experimental Procedures. Each value is the mean of 4 independent determinations ± SD.

Prediction of the function the Arg195 residue in 3β-HSD1 by docking analysis

Predictions of the functions of Arg195/Pro195 of 3β-HSD1/3β-HSD2 are based on the docking results obtained with our structural model of human 3β-HSD1, which has 51% homology of the Rossmann-fold domain and 40% identity of the key fingerprint residues that interact with bound substrate and cofactor compared to the crystallographic structures of E. coli UDP-galactose-4-epimerase and human 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (Pletnev et al., 2006). Site-directed mutagenesis has confirmed the function of the catalytic residues and key substrate and cofactor binding residues as predicted by the structural model (Thomas et al., 2002, 2005, 2007). In the current study, trilostane or DHEA was docked in the active site of our structural model of human 3β-HSD1 using Autodock 3.0. As shown in Figure 8A, the 17β-hydroxyl group of trilostane (4.0 Å) and the 17-keto group of DHEA (3.0 Å) are positioned to interact with the amino R groups of Arg195 of wild-type 3β-HSD1. Docking suggests that Pro195 in 3β-HSD2 does not function as a recognition residue for the 17β-hydroxyl group of trilostane (Figure 8B). In addition, 17β-acetoxy-trilostane docked with wild-type 3β-HSD1 containing Arg195 is flipped 180° relative to docked trilostane (Figure 9A), and the 3-keto group of 17β-acetoxy-trilostane appears to interact with Arg195 (3.4 Å). In Figure 9B, 17β-acetoxy-trilostane docked with the R195P mutant of 3β-HSD1 (containing Pro195) is not flipped 180° and aligns with docked trilostane outside of the active site (indicated by the catalytic Tyr154). To test these predictions, the P195R-2 mutant of 3β-HSD2 was created, expressed and purified. The P195R mutant of 3β-HSD2 (P195R-2) was produced because the introduction of Arg195 is a single “gain of function” mutation in 3β-HSD2 that may enhance the ability of this isoenzyme to bind trilostane as a definitive test of the role of Arg at this position.

Kinetic analyses of the inhibition of P195R-2, 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 by the trilostane analogs

Dixon analyses of the inhibition of the P195R-2 mutant, wild-type 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 by trilostane and 17β-acetoxy-trilostane produced a profile of Ki values and inhibition modes that clarifies the structural basis for the inhibition of 3β-HSD1 by trilostane with a 16-fold higher-affinity than 3β-HSD2 (Table 2). Trilostane inhibits 3β-HSD1 (Ki= 0.10 μM) in a competitive manner but inhibits 3β-HSD2 (Ki= 1.60 μM) noncompetitively. The P195R-2 mutation shifts the low affinity, noncompetitive inhibition profile of 3β-HSD2 to a high affinity (Ki= 0.19 μM), competitive inhibition profile similar to that of 3β-HSD1 containing Arg195. The inhibition kinetics in Table 2 also support the docking prediction that 17β-acetoxy-trilostane is flipped 180° relative to trilostane with an interaction between the 3-keto group and Arg195. The relatively low Ki value and competitive mode of inhibition of both the P195R-2 mutant of 3β-HSD2 and 3β-HSD1 for 17β-acetoxy-trilostane is consistent with the predicted interaction. Moreover, when Pro195 is present in 3β-HSD2 instead of Arg195, both trilostane and 17β-acetoxy-trilostane have low affinity, non-competitive inhibition profiles, possibly due to the lack of the Arg195 interaction with the steroids.

Table 2.

Comparison of inhibition constants of trilostane and 17β-acetoxy-trilostane for the purified human P195R-2 mutant, 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2.

| Inhibitor Ki values (μM)1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme | trilostane | 17β-acetoxy-trilostane |

| P195R-2 | 0.19 ± 0.02 (C) | 0.39 ± 0.03 (C) |

| 3β-HSD1 | 0.10 ± 0.01 (C) | 0.43 ± 0.03 (C) |

| 3β-HSD2 | 1.60 ± 0.10 | 1.59 ± 0.10 |

For P195R-2, 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2, incubations at 27 °C contained two subsaturating concentrations of DHEA, NAD+, purified enzyme and trilostane or 17β-acetoxy-testosterone in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, as described in Experimental Procedures. Dixon analysis (I versus 1/V) was used to determine the type of inhibition and calculate the Ki values. Ki values are means of triplicate determinations ± standard deviations. (C) denotes a competitive mode of inhibition, and no notation indicates a non-competitive mode.

Kinetic analyses of substrate and cofactor utilization by P195R-2, 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2

As shown in Table 3, the P195R-2 mutation shifts the low-affinity kinetic profile for the substrate (DHEA) of wild-type 3β-HSD2 (Km= 47.3 μM) to a 3.6-fold higher affinity profile (Km= 13.3 μM for P195R-2), which is similar to that of wild-type 3β-HSD1. The R195R-2 mutant enzyme has Km and kcat values for isomerase substrates that remain similar to those of wild-type 3β-HSD2. The Km values for the coenzymes of 3β-HSD (NAD+) and isomerase (NADH) measured for the P195R-2 mutant are also similar to those measured for wild-type 3β-HSD2 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Substrate kinetics for the 3β-HSD and isomerase activities for purified human P195R-2, 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2.

| 3β-HSD1 | Isomerase2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Km μM | kcat min−1 | kcat/Km min−1 μM−1 | Km μM | kcat min−1 | kcat/Km min−1 uM−1 |

| P195R-2 | 13.3 ± 2.5 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 0.71 ± 0.05 | 119 ± 5.0 | 131 ± 9.8 | 1.10 ± 0.09 |

| 3β-HSD1 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 0.89 ± 0.04 | 27.9 ± 1.1 | 50.2 ± 2.0 | 1.80 ± 0.08 |

| 3β-HSD2 | 47.3 ± 2.9 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 88.4 ± 5.7 | 81.4 ± 6.0 | 0.92 ± 0.06 |

Kinetic constants for the 3β-HSD substrate were determined in incubations containing DHEA, NAD+ and purified enzyme in 0.02 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, as described in Experimental Procedures.

Kinetic constants for the isomerase substrate were determined in incubations of 5-androstene-3,17-dione, NADH and purified enzyme in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, as described in Experimental Procedures. All values are the means of triplicate determinations ± standard deviations.

Table 4.

Cofactor kinetics for the 3β-HSD and isomerase activities for purified human P195R-2, 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2

| 3β-HSD1 | Isomerase2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Km μM | kcat min−1 | kcat/Km min−1 uM−1 | Km μM | kcat min−1 | kcat/Km min−1 uM−1 |

| P195R-2 | 56.4 ± 3.2 | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 0.25 ± 0.02 | 10.0 ± 0.2 | 89.5 ± 5.8 | 8.9 ± 0.7 |

| 3β-HSD1 | 34.1 ± 1.7 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.10 ± 0.005 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 45.0 ± 1.8 | 9.8 ± 0.4 |

| 3β-HSD2 | 86.3 ± 5.6 | 7.1 ± 0.6 | 0.08 ± 0.005 | 12.6 ± 0.9 | 99.1 ± 6.4 | 7.9 ± 0.5 |

Kinetic constants for the 3β-HSD cofactor were determined in incubations containing NAD+, dehydroepiandrosterone and purified enzyme in 0.02 M potassium phosphate, pH 7.4, as described in Experimental Procedures.

Kinetic constants for the isomerase cofactor were determined in incubations of NADH, 5-androstene-3,17-dione and purified enzyme in 0.02 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, as described in Experimental Procedures. All values are the means of triplicate determinations ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Human 3β-HSD1 has been overlooked as a target enzyme for inhibition in the treatment of breast cancer (Pasqualini, 2004). That is most likely due to the presence of two isoforms in the human female. 3β-HSD1 is expressed in mammary gland, breast tumors, placenta and skin, while 3β-HSD2 is expressed in the adrenal gland and ovary (Simard et al., 1996). Because the inhibition of adrenal 3β-HSD2 would block the production of cortisol and aldosterone in postmenopausal women, these unwanted effects tend to overshadow the value of inhibiting 3β-HSD1 in breast tumors to block estradiol production. However, we have shown that the classic 3β-HSD inhibitors, trilostane and epostane, competitively inhibit purified human 3β-HSD1 with 12- to 16-fold higher affinity compared to the noncompetitive inhibition of human 3β-HSD2 by these compounds (Thomas et al., 2002, 2005, 2008). To determine if this high-affinity inhibition of purified 3β-HSD1 translates into the selective inhibition of the growth of human breast tumors, we developed recombinant MCF-7 Tet-off breast tumor cells that express either 3β-HSD1 or 3B-HSD2 as well as the other enzymes required to produce estradiol from DHEA-S. As shown in Figure 6, trilostane and epostane inhibit the DHEA-induced proliferation of MCF-7 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells with 12- to 16- fold lower IC50 values compared to the MCF-7 3β-HSD2 aromatase cells. These results correlate well with the results obtained for inhibition of the purified isoenzymes and suggest that the development of more highly selective 3β-HSD1 inhibitors may produce effective treatments for hormone-sensitive breast cancer. The 3β-HSD inhibitors produce significant decreases in the proliferation of the MCF-7 Tet-off 3β-HSD1 aromatase cells (Figure 6) that equal the effects of the aromatase inhibitor, letrozole, on MCF-7 cell proliferation (Figure 7).

Using our well-tested structural model (Pletnev at al., 2006), docking analyses have identified three key residues in human 3β-HSD that may interact with trilostane. In a recent study (Thomas et al., 2008), Ser124 in both 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 was shown to interact with the 2α-cyanoketone group of trilostane by docking analyses, and this prediction was supported by site-directed mutagenesis followed by characterization of the purified S124T mutant enzyme. In this same study using the M187T mutant of 3β-HSD1, Thr187 (in wild-type 3β-HSD2) was shown to interact with the carbonyl group on the nicotinamide moiety of enzyme-bound NAD+ (Figure 8B), which indirectly participates in the low-affinity, noncompetitive inhibition of 3β-HSD2 by trilostane compared to the high-affinity, competitive inhibition of 3β-HSD1 containing Met187 at this position. In the current study, docking has identified Arg195 in 3β-HSD1 and Pro195 in 3β-HSD2 as a critical difference in the two isoenzymes. Figure 8 shows the interactions of Arg195, Thr187 and Ser124 with the side-chains of trilostane or NAD+. The inhibition kinetics of the P195R-2 mutant of 3β-HSD2 strongly support an interaction between the Arg195 residue in human 3β-HSD1 and the 17β-hydroxyl group of trilostane that may be a major structural factor responsible for the high-affinity, competitive inhibition of human 3β-HSD1 compared to the low-affinity, noncompetitive inhibition of 3β-HSD2 (containing Pro195). Substrate and cofactor kinetic data obtained with the P195R-2 mutant enzyme suggest that Arg195 interacts with the 3β-HSD substrate steroid, DHEA, but not with the isomerase substrate, 5-androstene-3,17-dione, or with the coenzymes for 3β-HSD and isomerase. There are 23 non-identical residues in the primary amino acid sequences of human 3β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD2 (Thomas et al., 2002). Based on the inhibition of 3β-HSD mutants by trilostane analogs as reported in this study, development of new 3β-HSD1 inhibitors that exploit one or more of these structural differences in the two human isoenzymes may lead to a new treatment for hormone-dependent breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant CA114717 (JLT). We thank Gavin P. Vinson, DSc PhD, School of Biological Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, for the providing the trilostane and for helpful comments.

The abbreviations are

- HSD

hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- ER

estrogen receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen RG, Neumann HC, Salvador UJ, Bell MR, Schane HP, Jr, Creange JE, Potts GO, Anzalone AJ. Steroidogenesis Inhibitors. 1 Adrenal Inhibitory and Interceptive Activity of Trilostane and Related Compounds. J Med Chem. 1984;27:928–931. doi: 10.1021/jm00373a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastell R, Hannon R. Long-term effects of aromatase inhibitors on bone. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;95:151–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh D, Vihko P. Molecular mechanism of estrogen recognition and 17-keto reduction by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1. Chemico-Biol Interactions. 2002;130–132:637–650. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras S, Moriggi R, Groner B, Simard J. Induction of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ5-Δ4 isomerase type 1 gene transcription in human breast cancer cell lines and in normal mammary epithelial cells by interleukin-4 and interleukin-13. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:66–81. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.1.0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havelock JC, Rainey WE, Bradshaw KD, Carr BR. The post-menopausal ovary displays a unique pattern of steroidogenic enzyme expression. Human Reprod. 2006;21:309–317. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasperk CH, Wakley GK, Hierl T, Ziegler R. Gonadal and adrenal androgens are potent regulators of human bone cell metabolism in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:464–471. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.3.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie F, Simard J, Luu-The V, Pelletier A, Belanger A, Lachance Y, Zhoa HF, Labrie C, Breton N, de Launoit Y, Dumont M, Dupont E, Rheaume E, Martel C, Couet J, Trudel C. Structure and tissue-specific expression of 3β-hydroxysteroid/5-ene-4-ene isomerase genes in human and rat classical and peripheral steroidogenic tissues. J Steroid Biochem Molec Biol. 1992;41:421–435. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(92)90368-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini JR, Chetrite GS. The Selective Estrogen Enzyme Modulators in Breast Cancer. In: Pasqualini JR, editor. Breast Cancer. Prognosis, Treatment and Prevention. Marcel Dekker; New York: 2002. pp. 187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini JR. The selective estrogen enzyme modulators in breast cancer: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1654:123–43. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pletnev VZ, Thomas JL, Rhaney FL, Holt LS, Scaccia LA, Umland TC, Duax WL. Rational Proteomics V: Structure-based mutagenesis has revealed key residues responsible for substrate recognition and catalysis by the dehydrogenase and isomerase activities in human 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase type 1. J Steroid Biochem Molec Biol. 2006;101:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MJ, Purohit A. Breast cancer and the role of cytokines in the regulating estrogen synthesis: an emerging hypothesis. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:701–715. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.5.0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen RJ, Santner SJ, Pauley RJ, Tait L, Kaseta J, Demers LM, Hamilton C, Yue W, Wang JP. Estrogen production via the aromatase enzyme in breast carcinoma: which cell type is responsible. J Steroid Biochem Molec Biol. 1997;61:267–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segel IH. Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-State Enzyme Systems. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1993. pp. 109–111. [Google Scholar]

- Shi R, Lin SX. Cofactor hydrogen bonding onto the protein main chain is conserved in the short chain dehydrogenase/reductase family and contributes to nicotinamide orientation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16778–16785. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313156200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard J, Durocher F, Mebarke F, Turgeon C, Sanchez R, Labrie Y, Couet J, Trudel C, Rheaume E, Morel Y, Luu-The V, Labrie F. Molecular biology and genetics of the 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/Δ5-Δ4 isomerase gene family. J Endocrinol. 1996;150:S189–S207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoden JB, Frey PA, Holden HM. Crystal structures of the oxidized and reduced forms of UDP-galactose 4-epimerase isolated from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2557–2566. doi: 10.1021/bi952715y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Myers RP, Strickler RC. Human placental 3β-hydroxy-5-ene-steroid dehydrogenase and steroid 5-4-ene-isomerase: purification from mitochondria and kinetic profiles, biophysical characterization of the purified mitochondrial and microsomal enzymes. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;33:209–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90296-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Myers RP, Rosik LO, Strickler RC. Affinity alkylation of human placental 3β-hydroxy-5-ene-steroid dehydrogenase and steroid 5-4-ene-isomerase by 2α-bromoacetoxyprogesterone: evidence for separate dehydrogenase and isomerase sites on one protein. J Steroid Biochem. 1990;36:117–123. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Evans BW, Blanco G, Mercer RW, Mason JI, Adler S, Nash WE, Isenberg KE, Strickler RC. Site-directed mutagenesis identifies amino acid residues associated with the dehydrogenase and isomerase activities of human type I (placental) 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase. J Steroid Biochem Molec Biol. 1998;66:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(98)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Mason JI, Brandt S, Spencer BR, Norris W. Structure/function relationships responsible for the kinetic differences between human type 1 and type 2 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and for the catalysis of the type 1 activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42795–42801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Umland TC, Scaccia LA, Boswell EL, Kacsoh B. The higher affinity of human type 1 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD1) for substrate and inhibitor steroids relative to human 3β-HSD2 is validated in MCF-7 tumor cells and related to subunit interactions. Endocrine Res. 2004;30:935–941. doi: 10.1081/erc-200044164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Boswell EL, Scaccia LA, Pletnev V, Umland TC. Identification of key amino acids responsible for the substantially higher affinities of human type 1 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/isomerase (3β-HSD1) for substrates, coenzymes and inhibitors relative to human 3β-HSD2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21321–21328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501269200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Huether R, Mack VL, Scaccia LA, Stoner RC, Duax WL. Structure/function of human type 1 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: an intrasubunit disulfide bond in the Rossmann-fold domain and a Cys residue in the active site are critical for substrate and coenzyme utilization. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2007;107:80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Mack VL, Glow JA, Moshkelani D, Bucholtz KM. Structure/function of the inhibition of human 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and type 2 by trilostane. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.04.007. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer EP, Hudis C, Burstein HJ, Wolff AC, Pritchard KI, Ingle JN, Chlebowski RT, Gelber R, Edge SB, Gralow J, Cobleigh MA, Mamounas EP, Goldstein LJ, Whelan TJ, Powles TJ, Bryant J, Perkins C, Perotti J, Braun S, Lange AS, Browman GP, Somerfield MR. ASCO technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]