Abstract

Objectives

Administering outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting (CoPAT) is becoming more common with the increasing emphasis on controlling costs. However, few controlled trials have evaluated this treatment modality.

Methods

Using data from a recent randomized trial comparing daptomycin with standard therapy (semi-synthetic penicillin or vancomycin, each with initial low-dose gentamicin) for Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and infective endocarditis (SAB/IE), patient characteristics and outcomes were evaluated. Patients receiving their full course of therapy in the hospital setting were compared with those who received some portion outside of the hospital (CoPAT).

Results

Among the 200 patients, 51.5% received CoPAT. These patients were generally younger (median age 50 versus 54 years, P = 0.028). In the CoPAT group, there tended to be fewer patients with endocardial involvement (8.7% versus 18.6%, P = 0.061) and pre-existing valvular heart disease (7.8% versus 15.5%, P = 0.120). CoPAT patients received longer therapy courses (mean 25.4 versus 13.5 days, P < 0.001) and had higher rates of therapy completion (90.3% versus 45.4%, P < 0.001) and clinical success (86.4% versus 55.7%, P < 0.001). Persisting or relapsing S. aureus was less frequent in the CoPAT group (3.9% versus 15.5%, P = 0.007) and there were fewer deaths (3.9% versus 18.6%, P = 0.001) 6 weeks after the end of therapy. Hospital readmission occurred for 18 of the 103 (17.5%) CoPAT patients. Clinical success rates were similar for CoPAT patients receiving daptomycin (90.0%) or standard therapy (83.0%).

Conclusions

With proper monitoring, stable patients can complete treatment for SAB/IE as outpatients in the community setting. Daptomycin is an appropriate option for this setting.

Keywords: outcomes, hospital readmission, OPAT, vancomycin, semi-synthetic penicillin

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (SAB) is a serious infection associated with significant complications, including infective endocarditis (IE) and other metastatic deep tissue infections as well as high rates of mortality.1–5 Rates of infection caused by methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) are increasing,6 and MRSA infections are associated with a greater risk of complications than are those due to methicillin-susceptible isolates. The mortality risk is approximately two to three times greater in patients with MRSA bacteraemia than in those with methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) bacteraemia.3,4

Patients with SAB/IE are likely to receive intravenous (iv) antimicrobial therapy for up to 4–6 weeks. An increasing focus on hospital costs and pressure to free up expensive hospital beds have motivated clinicians to seek alternative therapeutic approaches, including community-based outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (CoPAT). Numerous reports describing the use of CoPAT in a broad cross-section of patient populations support the notion that selected patients with SAB/IE—in particular, those who have stabilized in the hospital—may be candidates for the completion of therapy in a community setting.7–10 Typical community-based settings involve home treatment as well as treatment at nursing facilities, assisted-living facilities and rehabilitation centres. Although most studies of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) involve registries, or are otherwise retrospective in nature, the available data show that cure rates are generally >90% for bacterial infections of all kinds.8,9,11

While OPAT studies are plentiful, there is a paucity of data from controlled clinical trials. The recently completed prospective, randomized trial comparing daptomycin with standard therapy for SAB/IE captured detailed data on patients treated both inside and outside the hospital setting. In this study, standard therapy, against which daptomycin treatment was compared, consisted of a semi-synthetic penicillin or vancomycin, each with 4 days of initial low-dose gentamicin [1 mg/kg every 8 h, adjusted as appropriate for creatinine clearance (CLCR)].12

The unique database generated during the course of the randomized trial provides an opportunity to assess the impact of treatment setting on patients being treated for a serious infection. Therefore, we conducted a further analysis of the data to examine the clinical course of patients who completed their antibiotic therapy in the hospital compared with those who received some portion in the CoPAT setting.

Methods

Using data from the open-label, randomized, controlled trial of daptomycin versus standard therapy (semi-synthetic penicillin or vancomycin, each with initial low-dose gentamicin) for SAB/IE,12 the characteristics and outcomes of patients were evaluated based on treatment setting during administration of iv antimicrobial therapy. The randomized clinical trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00093067). The protocol, approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site, was consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients or their authorized representatives provided written informed consent. While the trial was conducted in several countries, this analysis was limited to patients treated in the USA because of differences in outpatient antimicrobial treatment approaches outside of the USA. Data included patient location during treatment with the study drug, including any changes in level of care (Table 1), and treatment outcome. Comparisons were made to elucidate the impact of changes in level of care.

Table 1.

Demographics, diagnosis and treatment characteristics by treatment location

| Characteristic | CoPAT (n = 103) | IPAT (n = 97) | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study drug | |||

| daptomycin | 50 (48.5%)b | 50 (51.5%) | 0.687c |

| vancomycind | 30 (29.1%) | 23 (23.7%) | |

| SSPd | 23 (22.3%) | 24 (24.7%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| median | 50.0 | 54.0 | 0.028e |

| range | 21–90 | 24–91 | |

| Male | 60 (58.3%) | 59 (60.8%) | 0.774 |

| Race | |||

| white | 66 (64.1%) | 55 (56.7%) | 0.070c |

| black | 30 (29.1%) | 25 (25.8%) | |

| other | 7 (6.8%) | 17 (17.5%) | |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| median | 81.7 | 78.2 | 0.493e |

| range | 49.9–129.0 | 53.5–131.4 | |

| MRSA | 37 (35.9%) | 39 (40.6%)f | 0.560 |

| CLCR (mL/min) | |||

| median | 92.1 | 86.0 | 0.064e |

| range | 29.4–277.0 | 17.9–200.8 | |

| CLCR <50 mL/min | 12 (11.7%) | 12 (12.4%) | >0.999 |

| Evidence of endocardial involvement | 9 (8.7%) | 18 (18.6%) | 0.061 |

| Injection drug use | 26 (25.2%) | 22 (22.7%) | 0.741 |

| Pre-existing valvular heart disease | 8 (7.8%) | 15 (15.5%) | 0.120 |

| Fever on day 4 | 10 (9.7%) | 18 (18.8%)g | 0.101 |

| Completed treatment | 93 (90.3%) | 44 (45.4%) | <0.001 |

| Duration of treatment (days) | |||

| mean (SD) | 25.4 (12.34) | 13.5 (9.49) | <0.001h |

| range | 9–74 | 1–43 | |

| Days inpatient during treatment | |||

| mean (SD) | 10.5 (7.27) | 13.5 (9.49) | 0.014h |

| range | 2–38 | 1–43 | |

| Days outpatient during treatment | |||

| mean (SD) | 14.9 (10.08) | 0 | NA |

| range | 1–49 | — | |

| Experienced ≥1 SAE | 48 (46.6%) | 52 (53.6%) | 0.396 |

CoPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting; IPAT, patients receiving their full course of therapy in the hospital setting; SSP, semi-synthetic penicillin; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; NA, not applicable; SAE, serious adverse event.

aFisher's exact test, unless otherwise specified.

bNo. (%), unless otherwise specified.

cOverall Fisher's exact test for characteristic.

dWith or without concomitant gentamicin.

eWilcoxon's rank sum test.

fn = 96 for MRSA.

gn = 96 for fever (inpatient): fever on day 4 was possible but not definitive on day 4 for six patients in the inpatient group who were considered to have not had a fever.

ht-test.

To be enrolled in the SAB/IE study, patients had to be at least 18 years of age and have had at least one blood culture growing S. aureus within 2 days before the first administration of the study drug. Exclusion criteria included CLCR <30 mL/min and the presence of known osteomyelitis, polymicrobial bacteraemia or pneumonia. Patients were evaluated at the end of therapy and 42 days after the end of therapy to determine treatment success and rule out relapse.12 Patients with persisting/relapsing S. aureus infection, death or clinical failure within 6 weeks of the end of therapy were considered clinical failures. This analysis did not consider administrative reasons for failure that were included in the primary efficacy analysis of the original study, such as discontinuation caused by an adverse event, administration of a potentially effective non-study drug and no blood culture drawn at test-of-cure visit.12

The protocol allowed completion of therapy in community care settings. The decision to pursue CoPAT was based on the investigators' assessment of patients' clinical stability, including the absence of surgical indications.13 Psychosocial characteristics and the availability of appropriate community care services were also considered. Patients receiving their full course of antimicrobial therapy in the hospital setting, categorized as inpatient antimicrobial therapy (IPAT), were compared with those receiving some portion of antimicrobial therapy outside of the hospital, categorized as CoPAT. For the purposes of this analysis, IPAT was defined as all care in one or more of the following locations: (i) hospital intensive care unit; (ii) hospital step-down unit; and (iii) general hospital ward. CoPAT was defined as initial inpatient treatment followed by care in one or more of the following locations: (i) skilled nursing facility; (ii) assisted-living setting, nursing home or rehabilitation centre; (iii) at-home treatment with assistance; and (iv) at-home treatment without assistance. Escalation of care was defined as any transfer to a location providing a higher level of care, as ordered above, for example, from ward to intensive care unit or home to ward.

iv access for CoPAT was selected by individual physicians and established prior to hospital discharge. Antibiotics were pre-mixed by an infusion pharmacy and delivered every 48 h. Vancomycin was administered as an infusion over at least 1 h; daptomycin and semi-synthetic penicillin doses were infused over 30 min. Vancomycin and daptomycin infusions were administered by nurses in all settings. Patients receiving semi-synthetic penicillins at home were treated via an ambulatory infusion pump programmed by home care nurses to deliver doses at 4 h intervals around the clock. Nurses monitored patients' overall status and vital signs daily during CoPAT; physicians were notified of changes in conditions. Except for end of therapy and test-of-cure visits, physician office follow-up was not standardized. Per study protocol, blood chemistries, complete blood counts and creatine phosphokinase levels were obtained weekly in all care settings.

Patient characteristics and outcomes were analysed using Fisher's exact test for categorical data and a two-sample t-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous data. All tests were two-sided. All analyses were performed using SAS® software, Version 9.1.

Results

Patient characteristics

Two hundred US patients were included in this analysis, with 103 (51.5%) receiving part of their treatment outside of the hospital setting (CoPAT). The majority of CoPAT patients (69/103, 67.0%) were discharged home without assistance and two others (1.9%) went home with assistance. Nineteen of the 103 CoPAT patients (18.4%) were discharged to a skilled nursing facility, while 13/103 (12.6%) were treated in an assisted-living setting, nursing home or rehabilitation centre. The study database did not systematically record the types of venous access devices used to deliver CoPAT. In general, peripherally inserted central catheters were the preferred means of securing venous access.

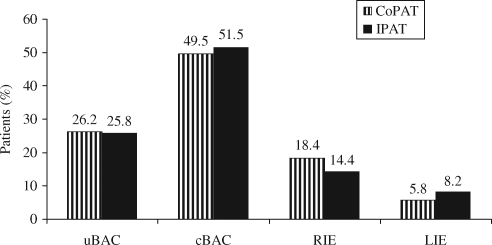

Compared with patients who received all care in the hospital, CoPAT patients were younger (median age 50 versus 54 years, P = 0.028) and tended to have fewer cases of endocardial involvement (8.7% versus 18.6%; P = 0.061) as well as less pre-existing valvular heart disease (7.8% versus 15.5%, P = 0.120). The two groups had a similar distribution of diagnoses (Figure 1) and a similar distribution of study medications. Baseline demographic, diagnostic and treatment characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Final diagnosis by CoPAT or IPAT treatment. CoPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting; IPAT, patients receiving their full course of therapy in the hospital setting; uBAC, uncomplicated bacteraemia; cBAC, complicated bacteraemia; RIE, right-sided infective endocarditis; LIE, left-sided infective endocarditis.

Other differences between the treatment groups included a trend towards higher baseline CLCR in the CoPAT patients (median 92.1 versus 86.0 mL/min, P = 0.064) and a trend towards a lower percentage of CoPAT patients with fever at day 4 of treatment (9.7% versus 18.8%, P = 0.101). Among CoPAT patients, baseline characteristics were similar for those receiving either daptomycin or comparator treatment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic, diagnosis and treatment characteristics by treatment group among CoPAT patients

| Characteristic | Daptomycin (n = 50) | Comparatora (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| median | 46.5 | 52.0 |

| range | 21–81 | 25–90 |

| Gender | ||

| male | 31 (62.0%)b | 29 (54.7%) |

| Race | ||

| white | 26 (52.0%) | 40 (75.5%) |

| black | 19 (38.0%) | 11 (20.8%) |

| other | 5 (10.0%) | 2 (3.8%) |

| Weight (kg) | ||

| median | 82.1 | 80.0 |

| range | 55.0–129.0 | 49.9–124.8 |

| MRSA | 18 (36.0%) | 19 (35.8%) |

| CLCR (mL/min) | ||

| median | 108.1 | 86.4 |

| range | 29.4–246.9 | 31.0–277.0 |

| CLCR <50 mL/min | 4 (8.0%) | 8 (15.1%) |

| Evidence of endocardial involvement | 4 (8.0%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| Injection drug use | 14 (28.0%) | 12 (22.6%) |

| Pre-existing valvular heart disease | 3 (6.0%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| Fever on day 4 | 3 (6.0%) | 7 (13.2%) |

| Completed treatment | 46 (92.0%) | 47 (88.7%) |

| Duration of treatment (days) | ||

| mean (SD) | 25.9 (13.31) | 25.0 (11.46) |

| range | 11–74 | 9–57 |

| Days inpatient during treatment | ||

| mean (SD) | 10.7 (7.06) | 10.3 (7.52) |

| range | 5–38 | 2–35 |

| Days outpatient during treatment | ||

| mean (SD) | 15.2 (10.08) | 14.7 (10.18) |

| range | 2–46 | 1–49 |

| Final diagnosis | ||

| uBAC | 10 (20.0%) | 17 (32.1%) |

| cBAC | 27 (54.0%) | 24 (45.3%) |

| RIE | 11 (22.0%) | 8 (15.1%) |

| LIE | 2 (4.0%) | 4 (7.5%) |

| Experienced ≥1 SAE | 23 (46.0%) | 25 (47.2%) |

CoPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; uBAC, uncomplicated bacteraemia; cBAC, complicated bacteraemia; RIE, right-sided infective endocarditis; LIE, left-sided infective endocarditis; SAE, serious adverse event.

aComparator treatment was semi-synthetic penicillin/gentamicin or vancomycin/gentamicin.

bNo. (%), unless otherwise specified.

Patient outcomes

Among CoPAT patients, clinical success rates were similar regardless of study medication, with 45/50 (90.0%) daptomycin patients and 44/53 (83.0%) comparator patients experiencing clinical success. For IPAT patients, clinical success was observed in 26/50 (52.0%) daptomycin patients and 28/47 (59.6%) comparator patients. Thus, it is justified to combine the treatment groups for analysis of outcomes.

CoPAT patients received longer courses of study antibiotics with a mean of 25.4 days (range 9–74 days) compared with 13.5 days (range 1–43) in the IPAT group (P < 0.001), and a higher proportion of CoPAT patients completed therapy as part of the study (90.3% versus 45.4%, P < 0.001). CoPAT patients received a mean of 14.9 days of therapy outside the hospital setting (Table 1). The shorter duration of study treatment for IPAT patients was influenced by early discontinuations: there were 53 (54.6%) versus 10 (9.7%) in the CoPAT group. The most common reason for discontinuation was adverse events, which accounted for 25/53 (47.2%) IPAT and 8/10 (80.0%) CoPAT patient discontinuations. The adverse events responsible for discontinuation, including rash, infection, renal failure and creatine phosphokinase elevation, are listed in Table 3. IPAT patients whose study participation was terminated prior to the end of therapy received subsequent antibiotic therapy as appropriate, but specific information regarding types and duration of additional therapy was not part of the study database.

Table 3.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation

| CoPAT (n = 8)a | IPAT (n = 25)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Anaphylactic reaction | 0 | 1 |

| Skinb | 4 | 4 |

| Red man syndrome | 0 | 1 |

| Diabetic gastroparesis | 1 | 0 |

| Vomiting not otherwise specified | 0 | 1 |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 1 | 2 |

| Cardiovascularc | 0 | 4 |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 1 |

| Infectiond | 0 | 3 |

| Fever | 0 | 2 |

| Renal failure | 2 | 3 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 2 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 1 |

aNumber of discontinuations due to an adverse event.

bSkin includes dermatitis bullous, dermatitis medicamentosa, erythematous rash, vesicular rash and rash not otherwise specified.

cCardiovascular includes cardiac arrest (two patients), cerebrovascular accident and circulatory collapse.

dInfection includes osteomyelitis not otherwise specified, staphylococcal pneumonia and staphylococcal bacteraemia.

A higher rate of clinical success at the test-of-cure visit was observed among CoPAT patients (89/103, 86.4%) compared with that among IPAT patients (54/97, 55.7%) (P < 0.001). Four of the 103 CoPAT patients (3.9%) experienced persisting or relapsing S. aureus infection, compared with 15/97 IPAT patients (15.5%, P = 0.007). Fewer deaths occurred in the CoPAT group (4/103, 3.9%) compared with those in the IPAT group (18/97, 18.6%; P = 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical outcomes for CoPAT patients versus IPAT patients

| Clinical outcome 6 weeks after end of therapy | CoPATa (n = 103) | IPAT (n = 97) | Pb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical success | 89 (86.4%)c | 54 (55.7%) | <0.001 |

| Failure | 10 (9.7%) | 26 (26.8%) | |

| Non-evaluable | 4 (3.9%) | 17 (17.5%) | |

| Death | 4 (3.9%) | 18 (18.6%) | 0.001 |

CoPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting; IPAT, patients receiving their full course of therapy in the hospital setting.

aInpatients who were partly treated outside a hospital.

bFisher's exact test.

cNo. (%).

Escalation of care

Twice as many CoPAT patients (22/103, 21.4%) were transferred to a higher level of care during their course of treatment compared with those transferred among IPAT patients (10/97, 10.3%), a difference that reached statistical significance (P = 0.036) (Table 5). Hospital readmission was required for 18 of the 103 (17.5%) CoPAT patients. As shown in Table 6, the reasons for hospital readmission were diverse. Four patients (22.2% of the readmissions and 3.9% of CoPAT patients) were readmitted for reasons related to their initial infection, including osteomyelitis or relapsed SAB. Problems related to provision of treatment in the post-acute care setting led to the readmission of three patients, two of whom relapsed with iv drug use (IVDU) and one of whom developed Clostridium difficile colitis. Other medical conditions leading to readmission included pneumonia in three patients and a myriad of other conditions, including unknown reasons, which were each experienced by a single patient. Of the 18 CoPAT patients readmitted to the hospital during the study, half subsequently returned to treatment in the CoPAT setting.

Table 5.

Escalation of care and patient location at last dose of study drug

| Characteristic | CoPAT (n = 103) | IPAT (n = 97) |

|---|---|---|

| Transferred to higher level of care at any time during treatment | 22 (21.4%)a–c | 10 (10.3%) |

| No. times readmitted to hospital to complete treatment with study drug | ||

| one | 17 (16.5%) | NA |

| two | 1 (1.0%) | NA |

| Returned to outpatient care after readmission | 9 (50.0%)d | NA |

| Reasons readmitted | ||

| factors relating to initial infection | 4 (22.2%) | NA |

| other conditionse | 11 (61.1%) | NA |

| issues relating to provision of treatment at home | 3 (16.7%)f | NA |

| Location for last dose of study drug | ||

| for patients who completed treatment | 93 (90.3%) | 44 (45.4%) |

| in hospital setting | 8 (7.8%)g | 44 (45.4%) |

| as an outpatient | 85 (82.5%) | 0 |

| for patients who prematurely discontinued treatment | 10 (9.7%) | 53 (54.6%) |

| in hospital setting | 2 (1.9%)g | 53 (54.6%) |

| as an outpatient | 8 (7.8%) | 0 |

CoPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting; IPAT, patients receiving their full course of therapy in the hospital setting; NA, not applicable.

aNo. (%).

bP = 0.036, Fisher's exact test.

cOne patient had increased level of care within post-acute care but was not readmitted to hospital. Three patients had escalation of inpatient care prior to post-acute care.

dBased on the 18 patients who were readmitted to hospital.

eUnderlying disease or new problems not related to the initial infection. See Table 6.

fOne patient was readmitted twice for the same problem related to delivery of treatment at home. See Table 6.

gPatients readmitted to hospital.

Table 6.

Patient status and factors related to hospital readmission among CoPAT patients

| Characteristic | CoPAT patients (n = 103) |

|---|---|

| No. of post-acute care patients readmitteda | 18/103 (17.5%)b |

| Reasons for readmission | |

| Factors relating to initial infection (n = 4) | |

| osteomyelitis | 2/18 (11.1%) |

| relapsed S. aureus bacteraemia | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| embolic stroke | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| Other conditions (n = 11) | |

| pneumonia | 3/18 (16.7%) |

| urinary tract infection | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| fever of unknown origin | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| gout | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| seizures (history of seizure disorder) | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| sarcoid | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| gastroparesis | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| left against medical advice | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| unknown | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| Issues relating to receipt of treatment at home (n = 3) | |

| drug use | 2/18 (11.1%) |

| C. difficile colitis | 1/18 (5.6%) |

| Study drug | |

| daptomycin | 9/50 (18.0%) |

| vancomycin | 4/30 (13.3%) |

| semi-synthetic penicillin | 5/23 (21.7%) |

| Final diagnosis | |

| uBAC | 2/27 (7.4%) |

| cBAC | 10/51 (19.6%) |

| RIE | 6/19 (31.6%) |

| LIE | 0/6 |

| Intravenous drug user | |

| no | 11/77 (14.3%) |

| yes | 7/26 (26.9%) |

CoPAT, outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy in the community setting; uBAC, uncomplicated bacteraemia; cBAC, complicated bacteraemia; RIE, right-sided infective endocarditis; LIE, left-sided infective endocarditis.

aOne patient was readmitted twice for reasons relating to treatment at home.

bNo. (%).

IVDU was associated with an increased risk of hospital readmission for CoPAT patients, with 7/26 (26.9%) IVDU patients requiring readmission, compared with 11/77 (14.3%) non-IVDU patients requiring readmission. The use of iv drugs during therapy was documented in two of the seven readmitted IVDU patients. Also of note was the fact that a higher proportion of patients with right-sided IE (6/19, 31.6%), though not statistically significant, required hospital readmission compared with those with other final diagnoses (Table 6). Five of the six readmitted patients with right-sided IE were iv drug users (four complicated right-sided IE and one uncomplicated right-sided IE).

Discussion

Numerous publications have described clinical experiences with OPAT in various countries, in some cases over extended periods of time, showing it to be generally safe, effective, convenient and economically beneficial when properly administered.8,11,14–18 These publications typically draw data from local or national OPAT registries or from the databases of hospitals or other facilities offering outpatient iv antimicrobial therapy services and that describe the experience of tens of thousands of patients. However, despite the voluminous data on OPAT, the availability of data from controlled clinical trials is meagre, especially among patients treated for MRSA infection,19,20 and it is poorer still in patients with SAB/IE.

Limited published data on outpatient iv antimicrobial therapy for various kinds of bacterial infections (not limited to S. aureus) indicate a hospital readmission rate of ∼8% to 30%,21,22 a range that includes the 17.5% rate observed in the present study. It should be noted that these data are based on a variety of different infections—including prosthetic infections, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis and soft tissue infections—that may be expected to have lower rates of readmission than SAB.

Of additional interest are the results from a recently published UK study by Matthews et al.,14 which compared ‘self-administered’ OPAT (i.e. parenteral antibiotic therapy administered by patients, relatives or caretakers) with OPAT administered by community-based healthcare workers. This study, which analysed data collected over 13 years and included 2059 patients, found no significant difference between the two approaches in either hospital readmissions (10.5% versus 12.6%, P = 0.3) or complications.14 It should be noted that 39% and 26.3%, respectively, of patients whose therapy was self-administered or given by healthcare workers were being treated for S. aureus infections.14

In 1992, it was estimated that ∼300 000 Americans are treated annually with outpatient iv antimicrobial therapy;23 it is likely that the number of courses of therapy has increased since then. The savings associated with outpatient treatment in such a large number of patients could be significant, since hospital stay represents ∼60% to 90% of the total cost of treating serious infections.24,25 Data from the present study support findings from previous studies of decreased length of hospital stay, which has been shown to reduce costs and would also likely reduce the risk of nosocomial infection.16,18 Detailed economic analysis of this study is ongoing.

Previous experience with OPAT suggests that success is most likely in patients with uncomplicated infections and in situations where appropriate agents and means of delivery are available.26,27 While there is a certain variability in the requirements for managing IE with outpatient therapy, guidelines created by the American Heart Association and endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) list the following minimal conditions for treatment in the home setting:27 reliable caretaker support and easy access to a hospital; regular visits by a home infusion nurse; and regular consultation (e.g. weekly) with a physician for assessment of clinical status. In the case of S. aureus IE, more stringent guidelines have been suggested. These include: hospitalization during the initial 2 week critical period (and possibly for a continuation phase of up to 2–4 weeks), patient education regarding potential complications as well as methods of contacting medical staff, proximity to the hospital, and biweekly office visits or home visits from the healthcare team.13

The optimal approach to outpatient treatment of SAB/IE for patients with a history of IVDU remains unclear. iv drug users typically respond well to treatment and have a similar, and possibly lower, mortality rate compared with other bacteraemia patients.28–30 The high cure rate among iv drug users with endocarditis has been partly attributed to the majority of infections involving the tricuspid valve, which responds particularly well to antimicrobial therapy as opposed to those involving the aortic or mitral valves.31 Among iv drug users, the rate of complications does not appear to be higher overall compared with other patients, although limited data suggest a higher rate of vascular events.28 The decision to discharge iv drug users to community settings is complicated by the potential for relapse of IVDU and suboptimal adherence to recommendations. These concerns may lead physicians to choose treatment settings with greater levels of supervision and structure. In this study, the rate of hospital readmission among iv drug users on CoPAT was nearly double that of CoPAT patients who were not iv drug users. It is worth noting that of the seven iv drug users readmitted to the hospital, two were found to have resumed use of iv drugs. Caution should be exercised in the selection and management of iv drug users who are candidates for CoPAT, as active drug use leads to safety and efficacy problems.

The current IDSA guidelines emphasize that when CoPAT therapy is considered, the antimicrobial agent selected should be effective against the causative pathogen, preferably dosed once daily, have a minimal adverse event profile, limited therapeutic drug monitoring and be stable in dosing formulations.32 The clinical trial upon which this analysis was based compared standard therapy (semi-synthetic penicillins or vancomycin with initial low-dose gentamicin) for SAB/IE with daptomycin, the first of a new class of cyclic lipopeptide antimicrobials.12 The standard treatment options may pose logistical challenges when used for CoPAT. Semi-synthetic penicillins are considered standard therapy for SAB/IE caused by MSSA but may be difficult to administer in the outpatient setting because of the need for multiple daily doses (up to six times per day), as well as tolerability issues such as rash and diarrhoea.8,33,34 Vancomycin is considered by many to be standard treatment for SAB/IE caused by MRSA, but it requires infusion over at least 1 h and therapeutic drug monitoring. In addition, a growing body of literature suggests inconsistent vancomycin efficacy because of changes in S. aureus susceptibility.35–38 Alternative agents such as daptomycin, which are conducive to use in the outpatient setting, are needed, particularly for MRSA infections.8,31,39–42 Daptomycin is an effective alternative to standard therapy,12,42 and its dosing schedule (once every 24 h for patients with a CLCR ≥30 mL/min or once every 48 h when the creatinine is <30 mL/min) is convenient for CoPAT. After reconstitution and dilution in iv solution, daptomycin is stable under refrigeration for 48 h per the current FDA-approved package insert.43

Limitations

The comparison of clinical outcomes between patients treated in the CoPAT and IPAT settings must be understood in the context of the patients' severity of illness. Candidates for outpatient antimicrobial therapy typically are stable patients at low risk of developing complications. The lower clinical success rate observed in the IPAT group in this study would be expected because of the greater severity of illness in these patients. One strength of this analysis is that it is based on data from a randomized, controlled clinical trial. However, the trial was not prospectively designed to assess outpatient versus inpatient care, and the retrospective nature of the current analysis may result in bias. In addition, as patients were followed only while receiving the study drug, treatment after study drug discontinuation was not captured.

It should be noted that outpatient antimicrobial therapy was provided at no cost as part of the trial, thereby potentially limiting the cost-related biases typically inherent in studies comparing inpatient with outpatient treatment. This aspect of the trial does not reflect real-life practice, where reimbursement for outpatient therapy varies depending on an individual's insurance coverage, and this may limit generalization of the study results. Furthermore, in analysing data only from US centres participating in the trial, the results draw on a smaller patient population than that of the original study, and may apply primarily in the USA.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates that stable patients with SAB/IE can successfully complete iv antibacterial therapy in the outpatient setting. Proper monitoring of these patients is necessary, as changes in their conditions may necessitate an escalation of care. This study further demonstrates that daptomycin is an appropriate treatment option for patients with SAB/IE who are completing therapy in the outpatient setting. Additional research is warranted to define selection criteria for patients with SAB/IE who may be candidates for outpatient therapy.

Funding

The randomized clinical trial from which this study is derived was sponsored and funded by Cubist Pharmaceuticals Inc., Lexington, MA, USA. This sub-analysis was supported by Cubist Pharmaceuticals. The decision to submit this sub-analysis for publication was made by Cubist Pharmaceuticals and the investigators of the primary study. No financial support or honoraria were given to the non-Cubist Pharmaceuticals authors for the development of this manuscript. The Cubist Pharmaceuticals authors were not awarded any additional support outside of their salary for their participation in this study. Phase Five Communications Inc. (New York), who provided assistance in preparing and editing the manuscript, were supported by Cubist Pharmaceuticals.

Transparency declarations

S. R. is on the speaker's bureau for Cubist and Wyeth, has served on advisory panels for Cubist and Pfizer and has participated in clinical research sponsored by Cubist. M. C. is an employed consultant for Cubist and owns Cubist stock. She provides consultation to Dyax Corp., Aeris Therapeutics, and Cowen and Company; last year, she also consulted for Shire Human Genetic Therapies. D. E. K. was a full-time employee of Cubist. R. R. is a full-time employee of Cubist and owns Cubist stock. H. W. B. serves or has served (in the past 2 years) as an advisor/consultant to Astellas/Theravance, Basilea, Cubist, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer and Targanta, and as a speaker for Cubist and Novartis; and had owned but has sold shares of Pfizer and Cubist. She has not been on any speakers bureaus since December 2007.

The statistical analyses were performed by M. C., a consultant for Cubist, under the direction of the authors. The funding source reviewed the data in the manuscript for accuracy. The authors had full access to the data in the study, interpreted the data, prepared the manuscript and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Phase Five Communications Inc. (New York) provided assistance in preparing and editing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the authors, the following US investigators participated in the trial: E. Abrutyn (deceased), R. Akins, H. Albrecht, M. Barron, J. M. Bernstein, M. Bessesen, H. R. Brodt, C. H. Cabell, P. Carson, H. F. Chambers, P. Cook, G. R. Corey, S. E. Cosgrove, D. Fierer, S. G. Filler, M. Foltzer, G. N. Forrest, V. G. Fowler Jr, M. Gareca, D. Goodenberger, K. High, B. Hirsch, C. Hsiao, A. W. Karchmer, H. Lampris, T. P. Le, D. Levine, M. Levinson, A. S. Link, J. Parsonnet, D. Pitrak, C. S. Price, J. P. Quinn, J. Ramirez, P. A. Rice, M. E. Rupp, J. Segreti, J. Stone, B. Suh, J. Tan (deceased), F. P. Tally (deceased), Z. Temesgen, A. Tice and M. Zervos.

References

- 1.Hill EE, Herijgers P, Claus P, et al. Infective endocarditis: changing epidemiology and predictors of 6-month mortality: a prospective cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:196–203. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Remadi JP, Habib G, Nadji G, et al. Predictors of death and impact of surgery in Staphylococcus aureus infective endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:1295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cosgrove SE, Sakoulas G, Perencevich EN, et al. Comparison of mortality associated with methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:53–9. doi: 10.1086/345476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blot SI, Vandewoude KH, Hoste EA, et al. Outcome and attributable mortality in critically ill patients with bacteremia involving methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2229–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.19.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boucher HW, Corey GR. Epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S344–9. doi: 10.1086/533590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:1763–71. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martone WJ, Lindfield KC, Katz DE. Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy with daptomycin: insights from a patient registry. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1183–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01824.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wynn M, Dalovisio JR, Tice AD, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy for infections with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. South Med J. 2005;98:590–5. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000145300.28736.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graninger W, Presterl E, Wenisch C, et al. Management of serious staphylococcal infections in the outpatient setting. Drugs. 1997;54(Suppl 6):21–8. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199700546-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rehm SJ. Outpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy for endocarditis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998;12:879–901. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito S, Noviello S, Leone S, et al. Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) in different countries: a comparison. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;24:473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fowler VG, Jr, Boucher HW, Corey GR, et al. Daptomycin versus standard therapy for bacteremia and endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:653–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andrews MM, von Reyn CF. Patient selection criteria and management guidelines for outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy for native valve infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:203–9. doi: 10.1086/321814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matthews PC, Conlon CP, Berendt AR, et al. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT): is it safe for selected patients to self-administer at home? A retrospective analysis of a large cohort over 13 years. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60:356–62. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chary A, Tice AD, Martinelli LP, et al. Experience of infectious diseases consultants with outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy: results of an emerging infections network survey. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1290–5. doi: 10.1086/508456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher DA, Kurup A, Lye D, et al. Outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy in Singapore. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2006;28:545–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nathwani D, Li JZ, Balan DA, et al. An economic evaluation of a European cohort from a multinational trial of linezolid versus teicoplanin in serious Gram-positive bacterial infections: the importance of treatment setting in evaluating treatment effects. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004;23:315–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wai AO, Frighetto L, Marra CA, et al. Cost analysis of an adult outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy (OPAT) programme. A Canadian teaching hospital and Ministry of Health perspective. Pharmacoeconomics. 2000;18:451–7. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200018050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gesser RM, McCarroll KA, Woods GL. Evaluation of outpatient treatment with ertapenem in a double blind controlled clinical trial of complicated skin/skin structure infections. J Infect. 2004;48:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poretz DM. Treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections utilizing an outpatient parenteral drug delivery device: a multicenter trial. HIAT Study Group. Am J Med. 1994;97:23–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoffman-Terry ML, Fraimow HS, Fox TR, et al. Adverse effects of outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy. Am J Med. 1999;106:44–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00362-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shrestha NK, Rehm SJ, Isada CM, et al. Abstracts of the Thirty-ninth Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, San Francisco, 2001. Arlington, VA, USA: Infectious Diseases Society of America; Rehospitalization after discharge on community-based parenteral anti-infective therapy (CoPAT) Abstract 816. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winters RW, Parver AK, Sansbury JD. Home Infusion Therapy: A Service and Demographic Profile: A Report for the National Alliance for Infusion Therapy. Washington, DC: National Alliance for Infusion Therapy; 1992. pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine MJ, Pratt HM, Obrosky DS, et al. Relation between length of hospital stay and costs of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2000;109:378–85. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calderone RR, Garland DE, Capen DA, et al. Cost of medical care for postoperative spinal infections. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:171–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monteiro CA, Cobbs CG. Outpatient management of infective endocarditis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2001;3:319–27. doi: 10.1007/s11908-001-0068-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation. 2005;111:e394–434. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.165564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruotsalainen E, Sammalkorpi K, Laine J, et al. Clinical manifestations and outcome in Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis among injection drug users and nonaddicts: a prospective study of 74 patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers HF, Miller RT, Newman MD. Right-sided Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in intravenous drug abusers: two-week combination therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:619–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-8-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korzeniowski O, Sande MA. Combination antimicrobial therapy for Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in patients addicted to parenteral drugs and in nonaddicts: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:496–503. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-4-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Small PM, Chambers HF. Vancomycin for Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in intravenous drug users. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1227–31. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tice AD, Rehm SJ, Dalovisio JR, et al. Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1651–72. doi: 10.1086/420939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dahlgren AF. Adverse drug reactions in home care patients receiving nafcillin or oxacillin. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1997;54:1176–9. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/54.10.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rehm SJ, Weinstein AJ. Home intravenous antibiotic therapy: a team approach. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:388–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-99-3-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soriano A, Marco F, Martínez JA, et al. Influence of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration on the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:193–200. doi: 10.1086/524667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Howden BP, Ward PB, Charles PG, et al. Treatment outcomes for serious infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:521–8. doi: 10.1086/381202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakoulas G, Moise-Broder PA, Schentag J, et al. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:2398–402. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2398-2402.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lodise TP, Graves J, Evans A, et al. Relationship between vancomycin MIC and failure among patients with MRSA bacteremia treated with vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3315–20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00113-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang FY, MacDonald BB, Peacock JE, Jr, et al. A prospective multicenter study of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: incidence of endocarditis, risk factors for mortality, and clinical impact of methicillin resistance. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;82:322–32. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000091185.93122.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fowler VG, Jr, Kong LK, Corey GR, et al. Recurrent Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: pulsed-field gel electrophoresis findings in 29 patients. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1157–61. doi: 10.1086/314712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine DP, Fromm BS, Reddy BR. Slow response to vancomycin or vancomycin plus rifampin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:674–80. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-9-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rehm SJ, Boucher H, Levine D, et al. Daptomycin versus vancomycin plus gentamicin for treatment of bacteraemia and endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus: subset analysis of patients infected with methicillin-resistant isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:1413–21. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cubicin® (daptomycin for injection) current prescribing information. http://cubicin.com/pdf/PrescribingInformation.pdf. (26 January 2009, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]