Abstract

UV-sensitive syndrome (UVSS) is a recently-identified autosomal recessive disorder characterized by mild cutaneous symptoms and defective transcription-coupled repair (TC-NER), the subpathway of nucleotide excision repair (NER) that rapidly removes damage that can block progression of the transcription machinery in actively-transcribed regions of DNA. Cockayne syndrome (CS) is another genetic disorder with sun sensitivity and defective TC-NER, caused by mutations in the CSA or CSB genes. The clinical hallmarks of CS include neurological/developmental abnormalities and premature aging. UVSS is genetically heterogeneous, in that it appears in individuals with mutations in CSB or in a still-unidentified gene. We report the identification of a UVSS patient (UVSS1VI) with a novel mutation in the CSA gene (p.trp361cys) that confers hypersensitivity to UV light, but not to inducers of oxidative damage that are notably cytotoxic in cells from CS patients. The defect in UVSS1VI cells is corrected by expression of the WT CSA gene. Expression of the p.trp361cys-mutated CSA cDNA increases the resistance of cells from a CS-A patient to oxidative stress, but does not correct their UV hypersensitivity. These findings imply that some mutations in the CSA gene may interfere with the TC-NER-dependent removal of UV-induced damage without affecting its role in the oxidative stress response. The differential sensitivity toward oxidative stress might explain the difference between the range and severity of symptoms in CS and the mild manifestations in UVsS patients that are limited to skin photosensitivity without precocious aging or neurodegeneration.

Keywords: Cockayne syndrome, DNA repair, transcription-coupled repair, ultraviolet radiation

Nucleotide excision repair (NER) is a versatile DNA repair system that removes a wide range of structurally-unrelated lesions, including UV photoproducts, which result in “bulky” local distortions of the DNA helix. NER operates through 2 subpathways in the early stages of damage recognition, depending on whether the damage is located anywhere throughout the genome [global genome repair (GG-NER)] or in an actively-transcribed gene [transcription-coupled repair (TC-NER)]. GG-NER begins with recognition of the damage by the XPC-RAD23B-cen2 complex, aided in some cases by the UV-damaged DNA binding activity (UV-DDB) that includes the subunits DDB1 and DDB2/XPE. The mechanisms for TC-NER are not completely understood; a current model postulates that the pathway is initiated by the arrest of RNA polymerase II at a lesion on the transcribed strand of an active gene, in a process that requires several factors including the CSA, CSB, and XAB2 proteins (1, 2). The recognition events in GG-NER and TC-NER are followed by a common pathway involving the unwinding of the damaged DNA, dual incisions in the damaged strand, removal of the damage-containing oligonucleotide, repair synthesis in the resulting gap, and ligation of the repair patch to the contiguous parental DNA strand. These steps require the coordinated action of several factors and complexes, including the repair/transcription complex TFIIH, and the repair factors XPA, XPG, and ERCC1-XPF in addition to those required for repair replication and ligation.

Defects in NER are associated with 3 major autosomal recessive disorders, namely xeroderma pigmentosum (XP), Cockayne syndrome (CS), and trichothiodystrophy (TTD). At the clinical level XP is characterized by a highly increased incidence of tumors in sun-exposed areas of the skin (reviewed in ref. 3). In contrast, CS and TTD are cancer-free disorders characterized by developmental and neurological abnormalities and premature aging, associated in TTD with typical hair abnormalities (reviewed in ref. 4). Seven NER-deficient complementation groups have been identified in XP (designated XP-A to XP-G). The XP-C and XP-E groups are specifically defective in GG-NER, whereas the remaining groups are defective in both NER subpathways. The 2 genes identified so far as responsible for the NER-defective form of CS (CSA and CSB) are specifically involved in TC-NER. In addition, rare cases have been described showing a complex pathological phenotype with combined symptoms of XP and CS (XP/CS) that have been associated with mutations in the XPB, XPD, or XPG genes (4). An eighth complementation group, the XP variant, is caused by defective translesion DNA synthesis (3).

NER defects have been reported in association with another disorder, designated UV-sensitive syndrome (UVSS). Initially described in 1994 by Itoh et al. (5), this condition currently comprises 1 Israeli (UVSTA24 or TA-24) and 5 Japanese (Kps2, Kps3, UVS1KO, XP24KO, and CS3AM) individuals. The patients exhibit photosensitivity and mild skin abnormalities; their growth, mental development, and life span are normal, and no skin or internal cancers have been reported to date. However, it must be noted that the oldest known UVSS patient is ≈40 years old. At the cellular level, UVSS and CS cells exhibit similar responses to UV irradiation: increased sensitivity to the cytotoxic effects of UV light, reduced recovery of RNA synthesis (RRS) after UV irradiation, and normal capability to perform UV-induced DNA repair synthesis (5, 6). Like CS cells, UVSS cells show normal GG-NER and are deficient in TC-NER of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPD) (7).

Two complementation groups have been identified among UVSS patients, defined by mutations in an as-yet-unidentified gene in 4 cases and in the CSB gene in 2 individuals (reviewed in ref. 8). In the latter cases, the mutation results in a severely truncated protein; however, no CSB protein was detected by Western blot analysis, and it has been proposed that the total absence of the CSB protein may be less deleterious than the truncated or abnormal counterparts found in CS-B patients (9). However, this hypothesis is not supported by recent investigations on 2 severely affected CS patients with undetectable levels of CSB protein and mRNA (10). Moreover, a mild form of CS with late onset of symptoms has been described in a 47-year-old individual with a mutation that results in a stop codon at amino acid position 82. No CSB polypeptide could be detected in extracts from this individual's cells (11), a situation reminiscent of that described by Horibata et al. (9), mentioned above. They raised the possibility that UVSS patients with mutations that result in very short, undetectable CSB protein might develop CS-like symptoms as they age (11).

We report here the description, genetic analysis, and cellular characteristics of a recently-identified UVSS patient (UVSS1VI) with a novel mutation in the CSA gene; this French patient may represent a third complementation group of UVSS. We show that UVSS1VI cells do not display the increased cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress typical of CS-A and CS-B fibroblasts. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the ectopic expression of the CSA gene cloned from UVSS1VI does not restore the altered response to UV of CS-A cells, but it does increase their resistance to oxidative stress. These findings support the hypothesis that the striking differences between the pathological phenotypes of CS and UVSS are caused by defective processing of oxidative DNA damage in CS but not in UVSS patients.

Results

Description of the UVSS1VI Patient.

The patient UVSS1VI, born in 1994, is the fourth child of healthy parents, who claimed the absence of consanguinity but were born in the same region of France; she has 3 healthy brothers. She presented sun sensitivity at the age of 4 months with easy sun burning and erythema. She has been monitored by the Dermatology Department of the University Hospital of Lille for extreme sun sensitivity since she was 8 years old. She presents numerous freckles on her face and exposed areas of the neck but she has no history or evidence of cutaneous tumors (Fig. 1); she wears sun protection when outdoors. She is now 15 years old, her school performance is normal, and she has not exhibited any developmental problems. Results from all recent neurological tests, which included MRI of the brain and audiogram, have been within normal ranges; computed tomography (CT) brain scans or nerve conduction studies were not carried out. Other clinical parameters, including detailed ophthalmologic examinations, yielded normal results. Routine laboratory tests showed no abnormalities except hypercholesterolemia at 2.4 g/dL. Blood levels of protoporphyrin and coproporphyrin were all within the normal limits, thus excluding the possibility that sun sensitivity could be related to high levels of porphyrin derivatives.

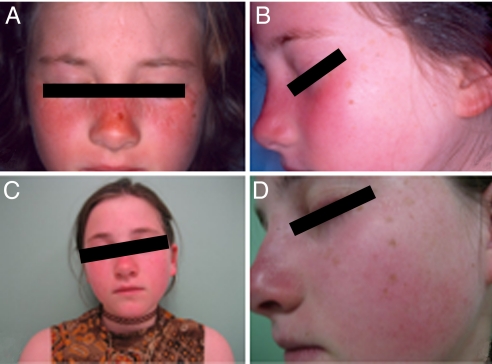

Fig. 1.

Patient UVSS1VI is shown at age 8 (A and B) and age 13 (C and D) presenting extreme sun sensitivity with erythema and freckling. No cutaneous tumors have been observed to date.

Cellular Response to UV.

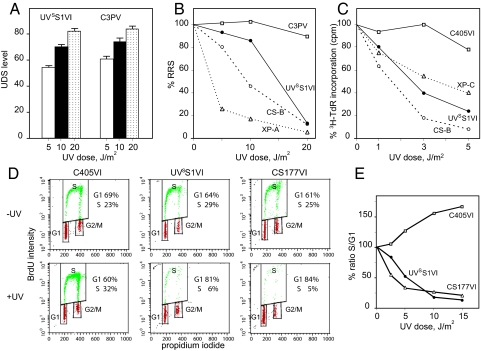

UVSS1VI primary fibroblasts exhibited normal capacity to perform UV-induced DNA repair synthesis (Fig. 2A), partially reduced RRS (Fig. 2B), and hypersensitivity to the lethal effects of UV (Fig. 2C). Caffeine had no further effect on UV sensitivity (Fig. S1), indicating normal capacity to carry out translesion DNA synthesis past UV-induced CPD, thus excluding the variant form of XP (12). The cell cycle in unirradiated UVSS1VI cells was similar to that in normal and CS-B cells, whereas a major block in G1/S was detected after UV irradiation (Fig. 2D). The blockage in early S phase was comparable in UVSS1VI and CS-B primary fibroblasts and extremely severe, as indicated by the very low number of cells in S phase compared with those in G1 (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

Response to UV irradiation. Fibroblast strains were from 2 normal donors (C3PV and C405VI; □) or patients UVSS1VI (●), XP11PV (XP-A) and XP202VI (XP-C) (dotted lines), and CS177VI and CS1PV (CS-B) (dashed lines). (A) UV-induced DNA repair synthesis (UDS) expressed as mean number of autoradiographic grains/nucleus. Bars indicate the SE. (B) RRS 24 h after UV irradiation. The mean numbers of autoradiographic grains per nucleus in irradiated samples are expressed as percentages of those in unirradiated cells. (C) Sensitivity to the lethal effects of UV light in proliferating fibroblasts labeled with 3H-thymidine 48 h after irradiation. Incorporation values in irradiated samples are expressed as percentages of those in unirradiated cells. The values in B and C were calculated from at least 2 independent experiments with SE <10% in all cases. (D) Cell cycle analysis by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) of fibroblasts from patient UVSS1VI, normal donor C405VI, and CS-B patient CS177VI. Dot plots of exponentially growing fibroblasts 24 h after exposure to 0 or 10 J/m2 of UV. Cells were pulse-labeled with 30 μM BrdU for 3 h, as described in Materials and Methods. (E) Quantitative assessment of the percentage of cells in S as compared with G0/G1 at the indicated UV doses.

The overall results from DNA repair investigations in UVSS1VI indicated defective capacity to repair UV-induced damage on the transcribed strand of active genes (i.e., TC-NER), but normal ability to remove lesions from the overall genome (i.e., GG-NER) and carry out translesion DNA synthesis, bypassing pyrimidine dimers on damaged DNA. Thus, the UV-induced cellular response of patient UVSS1VI was similar to that typically observed in CS-A and CS-B fibroblasts, although the alterations in RRS and survival were less severe than those commonly observed in CS fibroblasts at lower UV doses.

Characterization of the Gene Responsible for the NER Defect in UVSS1VI.

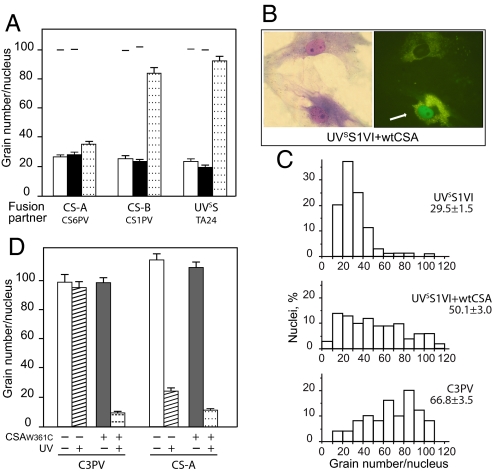

Genetic analysis of the DNA repair defect in UVSS1VI cells was carried out by evaluating the RRS after UV in classical complementation tests based on somatic cell hybridization (Fig. 3A). RNA synthesis levels in the heterodikaryons obtained after fusion of UVSS1VI cells with cells from CS-B patient CS1PV or UVSS patient TA24 were higher than those in the corresponding homodikaryons, indicating the presence of different genetic defects in the fusion partners. Conversely, fusions with CS-A cells from patient CS6PV did not result in increased RNA synthesis levels in the heterodikaryons compared with those in the homodikaryons. These results indicate that the activity of the CSA protein is impaired in UVSS1VI cells.

Fig. 3.

Genetic analysis of the repair defect in patient UVSS1VI by complementation and response to UV of normal and CS-A cells expressing the EGFP-CSAtrp361cys fusion protein. (A) Complementation analysis in heterodikaryons obtained by fusion of UVSS1VI fibroblasts with cells representative of different excision repair-deficient groups (CS-A, CS6PV; CS-B, CS1PV; UVSS, TA24). The partners in each fusion were labeled with latex beads of different sizes, and the RRS 24 h after UV was analyzed 73 h after fusion. The columns indicate the mean number of autoradiographic grains per nucleus in homodikaryons (patient, white column; reference strain, black column) and in heterodikaryons (dotted column). The bars indicate SE. The horizontal lines indicate the grain number per nucleus in the corresponding unirradiated samples analyzed in parallel. (B) RRS after UV irradiation in UVSS1VI primary fibroblasts after transfection with the plasmid pEGFP-CSA. Nuclear accumulation of the green fluorescent signal of the ectopic CSA protein (cell indicated by the white arrow, Right) is paralleled by a substantial increase in the number of autoradiographic grains, i.e., in the RRS levels, compared with nontransfected cells (Left). (C) RRS after UV irradiation in C3PV, UVSS1VI, and UVSS1VI expressing the EGFP-CSA fusion protein. The frequency distributions of nuclei with different grain numbers and the mean values of RRS ± SE are shown. (D) RRS after UV irradiation in normal (C3PV) and CS-A (CS3BR) primary fibroblasts after transfection with the plasmid pEGFP-CSAtrp361cys. The columns indicate the mean number of autoradiographic grains per nucleus in cells before (unirradiated: white columns; irradiated: shaded columns) and after transfection with the plasmid pEGFP-CSAtrp361cys (unirradiated: black columns; irradiated: dotted columns). The bars indicate SE.

To directly confirm that the partial DNA repair deficiency in UVSS1VI was caused by mutations in the CSA gene, we measured the RRS after UV irradiation in primary fibroblasts transiently transfected with a construct expressing the normal CSA protein tagged with EGFP (Fig. 3 B and C). A substantial increase in the RRS level was observed in cells exhibiting nuclear accumulation of the green fluorescent signal of the CSA chimera, compared with that in the nontransfected cells (Fig. 3B). In UVSS1VI fibroblasts expressing the EGFP-CSA fusion protein, the mean number of grains per nucleus increased from 29.5 ± 1.5 to 50.1 ± 3.0 grains per nucleus, with >70% of cells showing RRS levels in the normal range (Fig. 3C). The lack of restoration to normal levels of RRS in all of the transfected cells is not unexpected in assays for correction of DNA repair defects after microinjection or transfection of the WT gene (13, 14); it can probably be attributed to failure of the ectopic protein to be expressed under the optimal physiological conditions necessary to fully complement the repair defect in all of the cells. Overall, these results point to CSA as the gene responsible for the UV hypersensitivity in patient UVSS1VI.

Sequencing the CSA Gene.

Complete sequencing of the CSA cDNA in UVSS1VI cells revealed the presence, in the entire amplified population, of a G to T transversion at position 1083 (c.1083G>T), resulting in a trp361cys substitution (Fig. S2A). No other mutations were observed, suggesting that this alteration is responsible for the pathological phenotype of patient UVSS1VI. Sequencing of the genomic DNA confirmed that the patient was homozygous for this mutation (Fig. S2B), whereas the mother was heterozygous for the same mutation (Fig. S2C). Paternal material was not available. Therefore, patient UVSS1VI is either homozygous or a functional hemizygous for c.1083G>T.

Effect of Expression of the CSA Gene Containing the 1083G>T Mutation on DNA Repair.

To directly confirm that the mutation found in the CSA gene of patient UVSS1VI affects the cellular response to UV, we analyzed the RRS after UV irradiation in primary normal and CS-A fibroblasts transiently transfected with a construct expressing the trp361cys mutated CSA protein. No effect was observed in the basal levels of RNA synthesis, whereas both normal and CS-A fibroblasts failed to recover normal RNA synthesis levels at late times after UV irradiation, indicating that the trp361cys change results in defective function of the CSA gene (Fig. 3D).

Cellular Sensitivity to Oxidative Stress in UVSS1VI Cells.

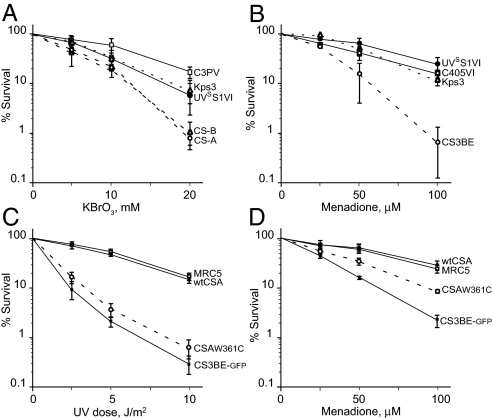

Primary fibroblasts from CS patients mutated in the CSA or CSB gene are hypersensitive to oxidants, and several lines of evidence indicate that the CS proteins are involved in the repair of biologically-diverse oxidative DNA lesions (ref. 15 and references therein). Comparative evaluation of the response to potassium bromate, a specific inducer of oxidative damage, showed that the cellular sensitivity of UVSS1VI was similar to that of UVSS patient Kps3 and approached that of normal primary fibroblasts, whereas CS-A and CS-B cells were characterized by a 2-fold increase in sensitivity (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Sensitivity to the lethal effects of oxidative stress. (A) Response of primary fibroblasts from patient UVSS1VI (●), normal donor C3PV (□), UVSS patient Kps3 (dotted line, ▵), and 2 CS patients (dashed lines; CS7PV: CS-A, ○; CS1AN: CS-B, △) to KBrO3 treatment. Survival values in treated samples are expressed as percentages of those in untreated cells. The reported values are the mean of at least 2 independent experiments. The bars indicate SE. (B) Response of SV40-transformed fibroblasts from patient UVSS1VI (●), normal donor C405VI (□), CS-A patient CS3BE (○), and UVSS patient Kps3 (△) to menadione treatment. Clonogenic survival is expressed as percentage of that for untreated cells. (C and D) Response of SV40-transformed CS3BE cells stably expressing WT CSA (●), the mutated CSAtrp361cys protein (○), or GFP alone (■) to UV irradiation (C) or menadione treatment (D). Survival values in treated samples are expressed as percentages of those in untreated cells. The reported values are the mean of at least 3 independent experiments.

In addition, treatment of SV40-transformed derivatives of UVSS1VI, CS3BE (CS-A), Kps3 (UVSS), and WT fibroblasts with menadione, a form of vitamin K that induces reactive oxygen species, resulted in a significant reduction in the clonogenic survival of CS3BE cells, whereas UVSS1VI cells exhibited survival similar to that of WT and UVSS Kps3 cells (Fig. 4B).

The effect of the mutated CSA trp361cys protein on responses to DNA-damaging agents was further investigated by analyzing the sensitivity to UV and menadione in isogenic cell lines isolated from SV40-transformed CS3BE (CS-A) cells, which had been stably transfected with a construct expressing either the normal or the mutated (trp361cys) CSA protein tagged with EGFP. The expression of WT CSA was associated with increased survival levels after both treatments (Fig. 4 C and D). In contrast, CS3BE cells ectopically expressing the CSAtrp361cys protein were still sensitive to UV (Fig. 4C), whereas their sensitivity to menadione was intermediate between those of the isogenic cell lines stably expressing either WT CSA or EGFP alone (Fig. 4D); as mentioned above, partial complementation is not unusual when expressing ectopic genes. Overall, these findings indicate that the trp361cys change in the CSA protein hampers the removal of UV-induced DNA lesions, while it does not substantially affect the removal of cytotoxic oxidative DNA lesions.

Discussion

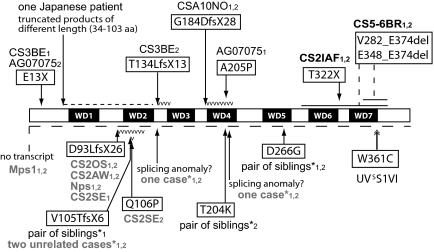

The patient described in this article carries a mutation in the CSA gene that is associated with the mild clinical outcome diagnostic for UVSS. This mutation, which had not been described previously to our knowledge, is predicted to cause a trp361cys substitution. Mutational patterns in the 20 CS-A patients reported in the literature (16–23) indicate that most of the mutations result in severely-truncated polypeptides because of stop codons, frameshifts, splice abnormalities or deletions (Fig. 5). Missense mutations resulting in the changes gln106pro, tyr204lys, and ala205pro have been found in the heterozygous state in single patients or affected members from the same family, whereas the asp266gly substitution was observed in the homozygous state in a pair of Brazilian siblings (16). Despite the paucity of clinical data and DNA repair investigations, the clinical outcome and the cellular features of these cases do not differ from those typically reported in other CS patients with severe inactivating mutations in CSA.

Fig. 5.

CSA protein and inactivating amino acid changes caused by the mutations found in 20 patients with CS, 8 of which are affected by the classical form of CS (code in black), and 3 by the severe form of CS (code in black bold). The clinical form of CS is not reported in the remaining 9 cases (code in gray). The diagram shows the CSA protein with the 7 WD repeats (black boxes). The amino acid changes are shown boxed, with the change in black on white. The numbers 1 and 2 after the patient code denote the different alleles. The change on the second CSA allele of the patient CS3BE refers to our unpublished observations; the mutation reported in Ridley et al. (23) is present on the genomic DNA and at the transcript level results in the deletion of exon 5 (c. 400_481del). The 8 Brazilian patients studied by Bertola et al. (16) are marked by *. Mutation nomenclature follows the format indicated at www.hgvs.org/mutnomen and refers to the cDNA sequence NM_000082.3 and protein sequence NP_000073.1. For cDNA numbering, +1 corresponds to the A of the ATG translation initiation codon in the reference sequence. The initiation codon is codon 1.

The mutation found in patient UVSS1VI is predicted to cause a substitution of the next to last amino acid within the last putative WD (W = tryptophane, D = aspartic acid) repeat of the CSA protein. According to its primary sequence, CSA contains 5 WD repeats (18); 2 additional WD repeats (namely, WD3 and WD6 in Fig. 5) have been predicted by sequence alignment with structural templates by using the COBLATH method (24). WD repeats are structural motifs capable of forming β-sheets. As a common functional theme, WD repeats form stable platforms coordinating sequential and/or simultaneous interactions involving several sets of proteins. Accordingly, it has been shown that CSA, through an interaction with DDB1, is integrated into a multisubunit complex, designated the CSA core complex, which displays E3-ubiquitin ligase activity. This activity is silenced immediately after UV irradiation by the rapid association of the CSA core complex with the COP9/signalosome (CSN), a protein complex with ubiquitin isopeptidase activity (25). By a mechanism dependent on CSB, TFIIH, chromatin structure, and transcription elongation (26), the CSA core/CSN complex translocates to the nuclear matrix where it colocalizes with the hyperphosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II engaged in transcription elongation (27). In cooperation with CSB, CSA then participates in recruitment of chromatin remodeling and repair factors to the arrested RNA polymerase II (28, 29). It has been suggested that once the repair complex has assembled the RNA polymerase II might be released, whereas CSB probably helps reposition the repair complex (30). The CSA-associated ubiquitin ligase activity, silenced by CSN at the beginning of the repair process, becomes active at later stages and degrades CSB, a key event for postrepair transcription recovery (ref. 31 and reviewed in ref. 1).

Evidence that the CSA protein has additional functions beyond its role in TC-NER has been provided by showing that CS-A primary skin cells, similar to CS-B cells, are hypersensitive to the lethal effects of oxidizing agents (15). The involvement of CS proteins in the removal of oxidative damage has been invoked to explain the neurological and aging features typical of CS, which cannot be explained by the persistence of UV-induced lesions. This notion has been supported by several independent observations (reviewed in refs. 32 and 33) that include a recent study of eye pathology in CS mouse models, implicating accumulation of endogenous oxidative DNA lesions in the retina in pigmentary retinopathy, a feature of CS-specific premature aging (34).

It is intriguing that the patient reported here, despite being mutated in the CSA gene, exhibits the mild phenotype and normal cellular sensitivity to oxidative stress typical of UVSS. This observation suggests a causal contribution of unrepaired oxidative damage to the aging and neurological degeneration at the organismal level typical of CS. Furthermore, it implies that the substitution trp361cys, resulting from the CSA mutation detected in UVSS1VI, affects the function of CSA in UV-induced TC-NER but does not interfere substantially with the role of CSA in the removal of cytotoxic oxidative DNA lesions. This finding has at least 2 relevant implications. First, the trp361cys change does not disrupt or strongly destabilize the overall structure of the CSA protein, events that would result in the complete loss of all CSA functions. Second, the CSA interactions implicated in the removal of cytotoxic oxidative DNA lesions do not completely overlap those relevant for TC-NER function.

Regions/sites of the CSA protein relevant for its multiple interactions have not yet been fully elucidated. Nevertheless, it has been shown that the ala205pro change found in CS patient AG07075 (17), and the changes lys174ala and arg217ala generated in the laboratory, abolish binding of CSA to DDB1 (35). Residue 361 is located in the C-terminal region of the protein and, as already mentioned, resides within the last putative WD repeat. The codon mutated in UVSS1VI encodes cysteine, an amino acid frequently present in β-sheets, although it has never been found next to the last amino acid (i.e., in the fifth position of the third strand) of the WD repeat in a nonredundant set of 776 WD repeats found in 123 WD-repeat proteins in SWISS-PROT/TrEMBL) (http://bmerc-www.bu.edu/projects/wdrepeat/).

There is another activity whose alteration interferes with the removal of UV-induced DNA damage by TC-NER without affecting the cellular sensitivity toward oxidative agents (36). This function is impaired in UVSS patients Kps2, Kps3, and TA24, who belong to the UVSS complementation group whose underlying gene has not yet been identified (reviewed in ref. 8). Thus, investigations on UVSS patients, despite the rarity of this disorder, indicate that defects in TC-NER alone cause mild cutaneous alterations and provide further evidence that the additional features present in CS patients, namely precocious aging and deficiencies in mental and physical development, reflect additional roles of the CSA and CSB proteins in the removal of oxidative damage. By demonstrating that the trp361cys change in the CSA protein results in reduced cell survival after UV but not after oxidative stress, the present study also suggests that the roles of the CSA protein in the removal of UV-induced damage and oxidative lesions may be uncoupled.

Materials and Methods

See SI Text for detailed procedures.

Cells.

Dermal fibroblasts from patient UVSS1VI were cultured from a skin biopsy taken from the right unexposed buttock at the age of 9 years. Primary fibroblasts were from normal donors (GM00038, C198VI, C405VI, and C3PV); CS-A donors [CS3BE (GM01856, Coriell Cell Repository, Camden, NJ), CS6PV, and CS7PV]; CS-B donors [CS1AN (GM00739, Coriell Cell Repository), CS177VI, and CS1PV]; UVSS donors (Kps3 and TA24); XPV donors (XP546VI and XP865VI); XP-A donor (XP11PV); and XP-C donor (XP202VI). The MRC5 cell line was a gift of A. Lehmann, University of Sussex, Sussex, U.K. The SV40-transformed fibroblast strains were from the Coriell Cell Repository (CS-A CS3BE.S3.G1), graciously provided by the late M. Yamaizumi, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan (UVSS Kps3SV13.3), or generated for this study (WT C405VI-SV, UVSS1VI-SV) as described (37). Cells were grown in minimal essential medium (Sigma) or HAM F10 medium (Cambrex) with 10% FCS (Euroclone) and antibiotics at 5% CO2, 37 °C.

Chemicals.

Potassium bromate (Sigma/Aldrich) stock solution (0.5 M) in PBS was stored at room temperature and warmed to 37 °C to dissolve before use. Menadione (Sigma/Aldrich) stock solutions (100 mM) in water were stored at 4 °C protected from light. 3H-thymidine (NET-027X; 1.0 mCi/ml, specific activity 20 Ci/mmol) and 3H-uridine (NET-174; 1.0 mCi/ml, specific activity 22.6 Ci/mmol) were from PerkinElmer.

Plasmid Preparation and Transfection of SV40-Transformed CS3BE Cells.

Full-length CSA cDNA from UVSS1VI cells was amplified by PCR using Pfu DNA polymerase by standard procedures. The identity of the CSA cDNA was confirmed by DNA sequencing. SV40-CS3BE cells were transfected with the pEGFP-CSAtrp361cys construct using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

DNA Repair Assays.

Responses to UV irradiation in primary fibroblasts were evaluated by unscheduled DNA synthesis (UDS) and RRS as described (38–41). Cell survival after UVC irradiation was carried out as described (12). Cell cycle analysis by FACS after UVC irradiation and determination of cell survival after UV, KBrO3 or menadione treatment were determined by standard assays.

Characterization of the Gene Responsible for the Disease.

Complementation analysis was performed by measuring RRS in hybrids obtained by fusing the patient's cells with CS reference strains as described (41).

Complementation of DNA repair capacity in primary fibroblasts transfected with plasmids expressing the normal or mutated (trp361cys) CSA protein tagged with EGFP was assessed by measuring RRS after UV irradiation as detailed in SI Text.

Molecular Analysis of the CSA Gene.

Extraction of total RNA with RNeasy (Qiagen) and reverse transcription using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) were carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. The procedures and primer sequences are given in SI Text.

Genomic DNA was isolated from fibroblasts by using the blood and cell culture DNA mini kit (Qiagen). Genomic DNA amplification was carried out as detailed in SI Text. Gel-purified PCR products were directly sequenced with the primer AS2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank members of the laboratory of Dr. J. C. Weill (University of Paris V, Paris) for sequencing of the POL eta and iota genes in the UVSS1VI cells and Mrs. D. Pham (Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France) for the UDS and RRS analysis. This work was supported by European Community Contract LSHM-CT-2005-512117, grants from the Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro, the Fondazione Cariplo, and the Istituto Superiore Sanità-Programma Malattie Rare (to M.S.), National Cancer Institute Grant CA91456 (to P.C.H.), and grants from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche and Ligue Contre le Cancer (Paris) and Association de Recherche sur le Cancer (Villejuif, France) (to A. Sarasin).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902113106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hanawalt P, Spivak G. Transcription-coupled DNA repair: Two decades of progress and surprises. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:958–970. doi: 10.1038/nrm2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarasin A, Stary A. New insights for understanding the transcription-coupled repair pathway. DNA Repair. 2007;6:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stefanini M, Kraemer KHK. Xeroderma pigmentosum. In: Ruggieri M, Pascual-Castroviejo I, Di Rocco C, editors. Neurocutaneous Diseases. NewYork: Springer; 2008. pp. 771–792. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehmann AR. DNA repair-deficient diseases, xeroderma pigmentosum, Cockayne syndrome, and trichothiodystrophy. Biochimie. 2003;85:1101–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoh T, Ono T, Yamaizumi M. A new UV-sensitive syndrome not belonging to any complementation groups of xeroderma pigmentosum or Cockayne syndrome: Siblings showing biochemical characteristics of Cockayne syndrome without typical clinical manifestations. Mutat Res. 1994;314:233–248. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(94)90068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiwara Y, Ichihashi M, Kano Y, Goto K, Shimizu K. A new human photosensitive subject with a defect in the recovery of DNA synthesis after ultraviolet-light irradiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;77:256–263. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12482447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spivak G, et al. Ultraviolet-sensitive syndrome cells are defective in transcription-coupled repair of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers. DNA Repair. 2002;1:629–643. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spivak G. UV-sensitive syndrome. Mutat Res. 2005;577:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horibata K, et al. Complete absence of Cockayne syndrome group B gene product gives rise to UV-sensitive syndrome but not Cockayne syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15410–15415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404587101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laugel V, et al. Deletion of 5′ sequences of the CSB gene provides insight into the pathophysiology of Cockayne syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:320–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hashimoto S, et al. Adult-onset neurological degeneration in a patient with cockayne syndrome and a null mutation in the CSB gene. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1597–1599. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broughton BC, et al. Molecular analysis of mutations in DNA polymerase eta in xeroderma pigmentosum-variant patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:815–820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022473899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Botta E, et al. Reduced level of the repair/transcription factor TFIIH in trichothiodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:2919–2928. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.23.2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapic-Otrin V, et al. True XP group E patients have a defective UV-damaged DNA binding protein complex and mutations in DDB2 which reveal the functional domains of its p48 product. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1507–1522. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Errico M, et al. The role of CSA in the response to oxidative DNA damage in human cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:4336–4343. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bertola DR, et al. Cockayne syndrome type A: Novel mutations in eight typical patients. J Hum Genet. 2006;51:701–705. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao H, Williams C, Carter M, Hegele RA. CKN1 (MIM 216400): Mutations in Cockayne syndrome type A and a new common polymorphism. J Hum Genet. 2004;49:61–63. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henning KA, et al. The Cockayne syndrome group A gene encodes a WD repeat protein that interacts with CSB protein and a subunit of RNA polymerase II TFIIH. Cell. 1995;82:555–564. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleppa L, Kanavin ØJ, Klungland A, Strømme P. A novel splice site mutation in the Cockayne syndrome group A gene in two siblings with Cockayne syndrome. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1397–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komatsu A, Suzuki S, Inagaki T, Yamashita K, Hashizume K. A kindred with Cockayne syndrome caused by multiple splicing variants of the CSA gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;128:67–71. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDaniel LD, Legerski R, Lehmann AR, Friedberg EC, Schultz RA. Confirmation of homozygosity for a single nucleotide substitution mutation in a Cockayne syndrome patient using monoallelic mutation analysis in somatic cell hybrids. Hum Mutat. 1997;10:317–321. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:4<317::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ren Y, et al. Three novel mutations responsible for Cockayne syndrome group A. Genes Genet Syst. 2003;78:93–102. doi: 10.1266/ggs.78.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridley AJ, Colley J, Wynford-Thomas D, Jones CJ. Characterization of novel mutations in Cockayne syndrome type A and xeroderma pigmentosum group C subjects. J Hum Genet. 2005;50:151–154. doi: 10.1007/s10038-004-0228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou H-X, Wang G. Predicted structures of two proteins involved in human diseases. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2001;35:35–47. doi: 10.1385/CBB:35:1:35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groisman R, et al. The ubiquitin ligase activity in the DDB2 and CSA complexes is differentially regulated by the COP9 signalosome in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2003;113:357–367. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saijo M, et al. Functional TFIIH is required for UV-induced translocation of CSA to the nuclear matrix. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2538–2547. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01288-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamiuchi S, et al. Translocation of Cockayne syndrome group A protein to the nuclear matrix: Possible relevance to transcription-coupled DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:201–206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012473199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fousteri M, Vermeulen W, van Zeeland AA, Mullenders LH. Cockayne syndrome A and B proteins differentially regulate recruitment of chromatin remodeling and repair factors to stalled RNA polymerase II in vivo. Mol Cell. 2006;23:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fousteri M, Mullenders LH. Transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells: Molecular mechanisms and biological effects. Cell Res. 2008;18:73–84. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lainé JP, Egly JM. When transcription and repair meet: A complex system. Trends Genet. 2006;22:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Groisman R, et al. CSA-dependent degradation of CSB by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway establishes a link between complementation factors of the Cockayne syndrome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1429–1434. doi: 10.1101/gad.378206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bohr VA, Ottersen OP, Tønjum T. Genome instability and DNA repair in brain, ageing and neurological disease. Neuroscience. 2007;145:1183–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyng KJ, Bohr VA. Gene expression and DNA repair in progeroid syndromes and human aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:579–602. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorgels TG, et al. Retinal degeneration and ionizing radiation hypersensitivity in a mouse model for Cockayne syndrome. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1433–1441. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01037-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin J, Arias EE, Chen J, Harper JW, Walter JC. A family of diverse Cul4-Ddb1-interacting proteins includes Cdt2, which is required for S phase destruction of the replication factor Cdt1. Mol Cell. 2006;23:706–721. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spivak G, Hanawalt PC. Host cell reactivation of plasmids containing oxidative DNA lesions is defective in Cockayne syndrome but normal in UV-sensitive syndrome fibroblasts. DNA Repair. 2006;5:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keriel A, Stary A, Sarasin A, Rochette-Egly C, Egly JM. XPD mutations prevent TFIIH-dependent transactivation by nuclear receptors and phosphorylation of RARα. Cell. 2002;109:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00692-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasquier L, et al. Wide clinical variability among 13 new Cockayne syndrome cases confirmed by biochemical assays. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:178–182. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.080473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarasin A, et al. Prenatal diagnosis in a subset of trichothiodystrophy patients defective in DNA repair. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:485–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb14845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stefanini M, et al. DNA repair investigations in nine Italian patients affected by trichothiodystrophy. Mutat Res. 1992;273:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(92)90073-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stefanini M, Fawcett H, Botta E, Nardo T, Lehmann AR. Genetic analysis of UV hypersensitivity in twenty-two patients with Cockayne syndrome. Hum Genet. 1996;97:418–423. doi: 10.1007/BF02267059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.