Abstract

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the major obstacles for successful cancer chemotherapy. Over-expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters such as MRP1/ABCC1 has been suggested to cause MDR. In this study, we explored the distribution frequencies of four common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of MRP1/ABCC1 in a mainland Chinese population and investigated whether these SNPs affect the expression and function of the MRP1/ABCC1. We found that the allelic frequencies of Cys43Ser (128G>C), Thr73Ile (218C>T), Arg723Gln (2168G>A) and Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) in mainland Chinese were 0.5%, 1.4%, 5.8% and 0.5%, respectively. These four SNPs were recreated by site-directed mutagenesis and tested for their effect on MRP1/ABCC1 expression and MDR function in HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells lines. We found that none of these mutations had any effect on MRP1/ABCC1 expression and trafficking, but that Arg723Gln mutation significantly reduced MRP1/ABCC1-mediated resistance to daunorubicin, doxorubicin, etoposide, vinblastine and vincristine. The Cys43Ser mutation did not affect all tested drugs resistance. On the other hand, the Thr73Ile mutation reduced resistance to methotrexate and etoposide while the Arg1058Gln mutation increased the response of two anthracycline drugs and etoposide in HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells as well as vinblastine and methotrexate in CHO-K1 cells. We conclude that the allelic frequency of the Arg723Gln mutation is relatively higher than other SNPs in mainland Chinese population and therefore this mutation significantly reduces MRP1/ABCC1 activity in MDR.

Keywords: ABC transporter, MDR, Multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1), drug resistance, genetic polymorphism

Introduction

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the major obstacles in cancer chemotherapy. Over-expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, such as P-glycoprotein (Pgp/MDR1/ABCB1) and multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1), have been shown to cause MDR in model cell lines and in clinical settings [1-3]. The ABC transporters comprise a superfamily with members that have a wide variety of substrates [4]. Human has 49 members of the superfamily that are grouped into 7 subfamilies from ABCA to ABCG (http://nutrigene.4t.com/humanabc.htm).

Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1) which was cloned in 1992 is the first member of the ABCC subfamily [5]. MRP1/ABCC1 can transport a number of different anticancer drugs including vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, and methotrexate [1, 2]. Human MRP1/ABCC1 is a 190-kDa protein consisting of 1,531 amino acids with three membrane-spanning domains (MSDs) and two nucleotide-binding domains (NBDs) [6]. While the NBDs of MRP1/ABCC1 function as ATPase to hydrolyze ATP and provide energy for the transport activity, the MSD provides support for drug binding, putative drug transport channel, dimerization and trafficking [7-9].

Patients often respond to drugs differently because of polymorphisms in their drug-metabolizing enzymes [10]. The importance of membrane drug transporters in determining the variability of drug response is beginning to be recognized [11]. Many polymorphisms have been identified in MRP1/ABCC1 gene and most of them are located in intronic sequences and non-coding regions [12] that do not affect the sequence or function of MRP1/ABCC1 proteins. Only 14 nonsynonymous genetic variants of human MRP1/ABCC1 have been identified to date [13] and these SNPs occur with different frequencies in different populations similar to nonsynonymous SNPs in other genes. However, many of their allelic frequencies in the general population are lower than 1%, especially in Asian populations [12, 14-16]. The four most common nonsynonymous SNPs in the Asian population are Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln mutations [15, 17]. While Cys43Ser (128G>C) is located in the first TM, Thr73Ile (218C>T), Arg723Gln (2168G>A) and Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) are located in the first intracellular loop, the first NBD, and the 7th intracellular loop, respectively (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1. Location and conservation of the amino acid residues with polymorphisms in MRP1/ABCC1.

(A) Location of Cys43Ser, Thr73lle, Arg723Gln and Arg1058Gln in the schematic model of MRP1/ABCC1. The polymorphic amino acids are shown in grey boxes. (B) Conservation of the four polymorphic amino acids. The alignment was performed using Clustal X 1.81 with human MRP1/ABCC1 (P33527), monkey MRP1/ABCC1 (Q864R9), bovine MRP1/ABCC1, (Q8HXQ5), Dog MRP1/ABCC1 (Q6UR05), Mouse MRP1/ABCC1 (O35379), Rat MRP1/ABCC1 (Q8CG09), and chicken MRP1/ABCC1 (Q5F364). The asterisks indicate the polymorphic amino acids.

To date, only three naturally occurring mutations of MRP1/ABCC1 (Gly671Val, Arg433Ser and Cys43Ser) have been fully investigated for their effects on MRP1/ABCC1-mediated MDR [18-20]. The other nonsynonymous SNPs of MRP1/ABCC1 were investigated only for the transport of methotrexate [13]. Some mutations have been proven to affect the function of MRP1/ABCC1. For example, the substitution of highly conserved Arg433 by Ser significantly decreased the transport of LTC4 and oestrone sulphate, but increased doxorubicin resistance [18].

Until now, no allelic frequency of the common SNPs of MRP1/ABCC1 in large samples of Chinese populations has been reported. To provide a basis for further clinical studies of this protein and its influence on drug resistance profiles in Chinese patients, we determined the allelic frequency of the four common SNPs in Chinese mainland populations and further studied their effect on MRP1/ABCC1 expression and function using cell lines that recreated these mutations.

Materials and methods

Materials

Vincristine, etoposide (VP-16), cisplatin, methotrexate, doxorubicin, vinblastine, daunorubicin and paclitaxel were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, Missouri, USA). The antibody against β-actin was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, California, USA). Cell culture media and reagents were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, California, USA). All other reagents were of molecular biology grade and from Sigma or Amresco (Solon, Ohio, USA).

Subjects

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Xiang-Ya School of Medicine, Central South University and written informed consents in compliance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) were obtained before this study was initiated. A total of 208 healthy volunteers (age: 23.4 ± 1.8 years, 72 females and 136 males) (mean ± SD) from mainland China were recruited to participate in this study. All the subjects were of Chinese Han nationality. Healthy volunteer status was ascertained through medical history, physical examination, routine clinical laboratory tests, and electrocardiography. All subjects were nonsmokers and free of prescription drugs, traditional medicines, and herbal supplements for at least 2 weeks before entry into the study. Subjects abstained from coffee and alcohol for a week before the study and had no prior or current history of substance abuse or dependence.

Genotyping for MRP1/ABCC1 polymorphisms

Five mLs of venous blood was collected in a sterile tube containing EDTA and stored at −80 °C. Genomic DNA was isolated from leukocytes using the Wizard Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) and stored at 4 °C until use. All of the genotypes of the candidate polymorphisms were determined using PCR–restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) assay as previously described [11] and all mutations were verified by sequencing analyses. The complete sequences of the primers, annealing temperature, restriction endonuclease, and other details are located in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers and PCR condition for determining polymorphisms.

| Polymorphisms | Oligonucleotide primes | Annealing temperature | Restriction enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cys43Ser (128G>C) | F: GGTCCTCGTGTGGGTGCCAT | 57.5°C | Nla III |

| R: TAGAAGAAGGAACTTAGGGTCAACT | |||

| Thr73Ile (218C>T) | F: TCAGATGACACCTCTCAACAGAA | 56.7°C | Hinf I |

| R: CCAGTTTTCACCTCCCACATTAT | |||

| Arg723Gln (2168G>A) | F: GCCTGGATTCAGAATGATTCTCTTC | 52°C | Taq I |

| R: TACTGACCTTCTCGCCAATCTCTGT | |||

| Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) | F: TCTGCATTGTGGAGTTTT | 53°C | Pst I |

| R: GACGAAGAAGTAGATGAGGC |

Site-directed mutagenesis

For site mutagenesis, cassettes containing various domains of MRP1/ABCC1 cDNA were first released from the full-length cDNA by double digestion (Not I/BamH I for Cys43Ser and Thr73Ile mutation; EcoN I/BsmB I for Arg723Gln mutation; BsmB I/EcoR I for Arg1058Gln mutation), cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA), followed by site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, California, USA) with the following primers (the substituted nucleotides are italicized): 5’-TCGTGTGGGTGCCTTGTTTTTACCTCTGGGC-3’ (Cys43Ser); 5’-GATGACACC TCTCAACAAAACCAAAACTGCCTTGGGATTTT-3’ (Thr73lle); 5’-GGATTCAGAATGATTCTCTCCAAGAAAACATCCTTTTTGGATG-3’ (Arg723Gln); 5’-GCACAGCATCCTGCGGTCACCCATGAGCT-3’ (Arg1058Gln). The cassettes containing the mutations were then subcloned back into the full-length MRP1/ABCC1 cDNA in pcDNA3.1 and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Cell culture and transfections

HEK293 cells were maintained in DMEM medium while CHO-K1 cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium, both supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and with 200 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. For transient transfection, 10 μg of vector control, pcDNA3.1(-)-MRP1/ABCC1WT, MRP1/ABCC1Cys43Ser, MRP1/ABCC1Thr73lle, MRP1/ABCC1Arg723Gln, and MRP1/ABCC1Arg1058Gln were transfected into HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells in a 100 mm dish using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested and stored as cell pellets at −80°C until needed. For stable transfection, 4 μg of vector control, pcDNA3.1(-)-MRP1/ABCC1WT, MRP1/ABCC1Cys43Ser, MRP1/ABCC1Thr73lle, MRP1/ABCC1Arg723Gln, and MRP1/ABCC1Arg1058Gln were transfected into HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells in 6-well plates using Lipofectamine 2000, respectively. Forty-eight hours following transfection, cells were re-plated in 100 mm plates and selected with G418 (Amresco, Solon, Ohio, USA) at 400 μg/ml (CHO-K1) or 500 μg/ml (HEK293) for 2 weeks. The G418 resistant cell colonies were selected using cloning cylinders and maintained in 300 μg/ml (CHO-K1) or 350 μg/ml (HEK293) G418. The MRP1/ABCC1 expression in stable cell lines was detected by real-time PCR or Western blot.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR analysis

The cells were harvested and total RNA was isolated using a Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). 1 μg of the total RNAs was reverse transcribed using Reverse Transcription System Kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The real-time PCR were carried out in a Stratagene Mx3000p Multiplex Quantitative PCR System (Stratagene, La Jolla, California, USA) using SYBR GreenER qPCR Supermix Universal Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The pimers used for MRP1/ABCC1 were 5’-CAACGGGACTCAGGAGCACA-3’(forward) and 5′-CGGCCATGGAGTAGCCAAAC-3’(reverse); and for β-actin control were 5’-TGGCACCCAGCACAATGAA-3’(forward) and 5’-CTAAGTCATAGTCCGCCTAGAAGCA-3’(reverse). The Ct value was defined as the PCR cycle number at which the reporter fluorescence crosses the threshold. The Ct value of each product was determined and normalized against that of the internal control, β-actin.

Lysate preparation and Western Blot

Cell lysate was prepared by lysis in RIPA buffer (50mM Tris (pH 7.4), 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1mM sodium orthovanadate, 100μg/ml PMSF) at 4°C for 30 min followed by centrifugation at 10,000g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration of the lysates was determine using the method of BCA (bicinchoninic acid). Cell lysates were then separated using 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, Massachusetts, USA). The membrane was then blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk overnight and probed with monoclonal antibody QCRL-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA). The reaction was detected by HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody and visualize using a SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA).

MTT assay

The effect of mutations on MRP1/ABCC1-mediate drug resistance was determined using MTT (methyl thiazolyl tetrazlolium) assay. Briefly, CHO-K1 and HEK293 cells stably transfected with vector control, wild-type, or mutant MRP1/ABCC1 were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured for 24 hrs before the anticancer drugs were added to different concentrations. Following continued incubation for additional 1−5 days, the culture medium was removed and 3-[4,5-dimehyl-2-thiazolyl]-2, 5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA) was added to each well to form a final concentration of 1 mg/ml. The incubation was continued for 6 hrs at 37°C. The formazan was solubilized by adding Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, USA) and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm in a Multiskan Ascent 354 microplate reader (Thermo Labsystems, Helsinki, Finland). The absorption value was determined by Ascent Software™ and IC50 values were obtained from the dose-response curves. A relative resistance factor was obtained by dividing the IC50 of the cells stably transfected with wild-type or mutant MRP1/ABCC1 by the IC50 values of the cells stably transfected with the vector controls from at least six independent experiments.

Confocal microscopy imaging

Confocal microscopy imaging was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, 5 × 105 CHO-K1 or HEK293 cells were seeded on a glass coverslip in a six-well tissue culture plate the day before transfection. The cells were then transiently transfected with 2.5 μg of the vector control, pcDNA3.1(-)-MRP1/ABCC1WT, MRP1/ABCC1Cys43Ser, MRP1/ABCC1Thr73lle, MRP1/ABCC1Arg723Gln, and MRP1/ABCC1Arg1058Gln. Three days following transfection, the cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and fixed with acetone/methanol (1:1) at room temperature for 10 minutes and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with blocking solution (1% BSA in PBS). The cells were then probed with primary antibody MRPr1 (Kamiya Biomedical Company, 2.5 μg/ml) for 1 hr at 4°C followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated donkey anti-rat IgG F(ab’)2 fragment (Jackson ImmunoReseach) (14 μg/ml) at 4°C for another 1 hr. The cells were then washed three times with blocking solution and the cell nuclei were counter stained with propidium iodide (25 μg/mL) for 10 min. The coverslips were then mounted on the slides before viewing with a confocal microscope.

Statistical analysis

Handy-Weinberg equilibrium was assessed with a χ2-square test in the study sample. The IC50 of different groups were analyzed by standardized Student's t test. The real-time PCR data were analyzed by a two-sample Student's t test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant in the study. All statistical analysis was performed in SPSS (version 11.5 for Windows, SPSS Inc, Illinois, USA).

Results

Location and conservation of the four amino acid residues with SNPs in the human MRP1/ABCC1 gene

The four SNPs investigated in this study are located in exon 2, exon 17, and exon 23, respectively. While the Cys43Ser mutation is located in the first TM helix, the other three are located in the intracellular loops or the nucleotide-binding domain (Figure 1A). It is interesting to note that the Arg723Gln mutation is located between the Walker A and Walker B motives in NBD1 which is important for the ATPase activity of MRP1/ABCC1 to provide energy for substrate transport. These four amino acid residues are also highly conserved among MRP1/ABCC1 from different species (Figure 1B).

The distribution of polymorphisms in Chinese population

In the 208 volunteers, genotyping of the Arg723Gln mutation identified 185 GG homozygotes, 22 GA heterozygotes and 1 AA homozygote. The frequencies of A and G alleles for the Arg723Gln mutation were 5.8% and 94.2%, respectively. Genotyping for the Thr73Ile mutation identified 202 CC homozygotes and 6 CT heterozygotes. The frequencies of T and C alleles of the SNP for the Thr73Ile mutation were 1.4 % and 98.6 %, respectively. The remaining two SNPs are rare polymorphisms in the population and we found only 2 heterozygotes in each of these two SNPs. The frequencies of C alleles for the SNP of Cys43Ser and A alleles for the SNP of Arg1058Gln were both about 0.5%. Genotyping frequencies for all SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The genotyping and allelic frequencies of SNPs for Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln mutations are shown in Table 2. The distribution of these SNPs in different populations and their comparison are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Genotyping and allelic frequencies of MRP1/ABCC1 polymorphisms.

| SNPs (Nucleic acid substitution) | Allele | Allelic frequency | Genotype | Genotype frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cys43Ser (128G>C) | G | 0.995 (414) | GG | 0.990 (206) |

| C | 0.005 (2) | GC | 0.010 (2) | |

| CC | 0 (0) | |||

| Thr73Ile (218C>T) | C | 0.014 (410) | CC | 0.971 (202) |

| T | 0.986 (6) | CT | 0.029 (6) | |

| TT | 0 (0) | |||

| Arg723Gln (2168G>A) | G | 0.942 (392) | GG | 0.889 (185) |

| A | 0.058 (24) | GA | 0.106 (22) | |

| AA | 0.005 (1) | |||

| Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) | G | 0.995 (414) | GG | 0.990 (206) |

| A | 0.005 (2) | GA | 0.010 (2) | |

| AA | 0 (0) |

Table 3.

Comparison of distributive frequencies of MRP1/ABCC1 Cys43Ser, Thr73lle, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln polymorphisms in different ethnic populations.

| SNPs (Nucleic acid substitution) | Allelic frequency |

Population | References | NCBI SNP ID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | w | ||||

| Cys43Ser (128G>C) | 0.010(1/96) | 0.990(95/96) | Japanese | [16] | rs41395947 |

| 0(0/26) | 1(26/26) | Japanese | [14] | ||

| 0.005(2/416) | 0.995(414/416) | Chinese | This study | ||

| Thr73Ile (218C>T) | 0.010(1/96) | 0.990(95/96) | Japanese | [16] | rs41494447 |

| 0(0/26) | 1(26/26) | Japanese | [14] | ||

| 0.037(2/54) | 0.963(52/54) | Chinese | [17] | ||

| 0.014(1/72) | 0.986(71/72) | Chinese | [15] | ||

| 0.029(2/70) | 0.971(68/70) | Malay | [15] | ||

| 0(0/70) | 1(70/70) | Indian | [15] | ||

| 0(0/72) | 1(72/72) | Caucasian | [15] | ||

| 0.014(6/416) | 0.986(410/416) | Chinese | This study | ||

| Arg723Gln (2168G>A) | 0.073(7/96) | 0.927(89/96) | Japanese | [16] | rs4148356 |

| 0.038(1/26) | 0.962(25/26) | Japanese | [14] | ||

| 0.056(3/54) | 0.944(51/54) | Chinese | [17] | ||

| 0(0/72) | 1(72/72) | Chinese | [15] | ||

| 0.029(2/70) | 0.971(68/70) | Malay | [15] | ||

| 0(0/70) | 1(70/70) | Indian | [15] | ||

| 0(0/72) | 1(72/72) | Caucasian | [15] | ||

| 0.058(24/416) | 0.942(392/416) | Chinese* | This study | ||

| Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) | 0.010(1/96) | 0.990(95/96) | Japanese | [16] | rs41410450 |

| 0(0/26) | 1(26/26) | Japanese | [14] | ||

| 0.005(2/416) | 0.995(414/416) | Chinese | This study | ||

P<0.05 compared with Caucasian population

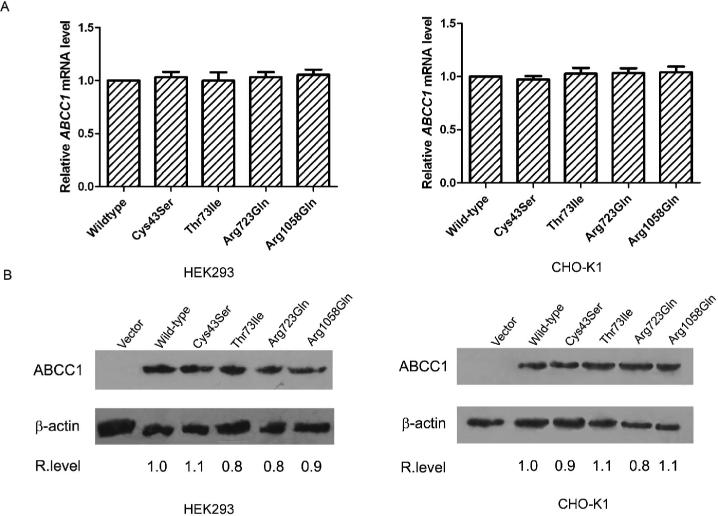

mRNA and protein expression levels of MRP1/ABCC1 mutants

To determine if these SNPs affect MRP1/ABCC1 expression, Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln mutations were recreated in MRP1/ABCC1 cDNA by site-directed mutagenesis and transiently transfected into HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells. The expression levels of the wild-type and mutant MRP1/ABCC1 were determined by Real-Time RT-PCR and Western blot for comparison. As shown in Figure 2, there are no significant differences in expression at the mRNA and protein levels between the wild type and mutant MRP1/ABCC1 in both cell types used. We have also performed similar studies using Cos-7 and HEK293T cells and observed similar results (data not shown). Thus, the mutations of these four amino acids do not affect the expression level of the MRP1/ABCC1 protein.

Figure 2. Effect of mutations on MRP1/ABCC1 expression.

HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells were transiently transfected with vector control or wild-type, Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln and Arg1058Gln mutant MRP1/ABCC1 followed by preparation of RNAs for quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis of MRP1/ABCC1 mRNA level (A), or preparation of cell lysates for Western blot analysis of MRP1/ABCC1 protein level (B). The relative mRNA level shown with means ± standard deviation is the average of five independent experiments. β-actin was used as a loading control for the Western blot analysis. The relative expression level of MRP1/ABCC1 (as indicated below the blots) was determined based on the density of MRP1/ABCC1 and the β-actin bands measured using BandScan software.

Subcellular localization of wildtype and mutant MRP1/ABCC1

To further determine if Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln mutations influence the trafficking of MRP1/ABCC1 to the cell surface, we detected the subcellular localization of wildtype and mutant MRP1/ABCC1 in transiently-transfected HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells through the process of immunostaining. As shown in Figure 3, strong plasma membrane staining was observed with all cells that are transfected with either wild type or mutant MRP1/ABCC1, but not in the vector-transfected control cells. It appears that the mutations do not affect the subcellular localization and, thus, it is possible that there is no effect on the trafficking of human MRP1/ABCC1 to plasma membranes.

Figure 3. Effect of mutations on subcellular localization of MRP1/ABCC1.

HEK293 (A) and CHO-K1 (B) cells were transiently transfected with vector control or wild-type, Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln and Arg1058Gln mutant MRP1/ABCC1, followed by fixation and immunostaining of MRP1/ABCC1 using MRPr1 antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody. Nuclei were counter stained with propidium iodide.

Drug resistance profiles of wild type and mutant MRP1/ABCC1

Previously, these SNPs have been studied for their effect primarily on methotrexate resistance [13]. However, it is not known if they affect MRP1/ABCC1-mediated MDR or drug substrate specificity. To further determine if these SNPs affect substrate specificity of MRP1/ABCC1 and, thus, MRP1/ABCC1-mediated MDR, we established stable cell lines using CHO-K1 and HEK293 cells with over-expression of wild type and mutant MRP1/ABCC1. In order to generate a comprehensive profile, we chose several different types of anticancer drugs. Cisplatin and paclitaxel, which are not substrates of MRP1/ABCC1, were also included to determine if the mutations may create a functional gain. The results are shown in Figures 4 and 5 and are summarized in Tables 4 and 5. It appears that all cells expressing wild type MRP1/ABCC1 have substantially higher IC50 or higher resistance to all drugs except cisplatin and paclitaxel when compared to the vector-transfected control cells. All mutations appeared to have no effect on the IC50 of or resistance to cisplatin and paclitaxel, suggesting that the mutation does not cause any functional gain.

Figure 4. Effect of mutations on MRP1/ABCC1-mediated MDR in HEK293 cells.

HEK293 cells stably transfected with vector, wild-type, or Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln mutant MRP1/ABCC1 were exposed to cisplatin, paclitaxel, etoposide, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, methotrexate, vinblastine and vincristine at various concentrations for 72 hrs at 37°C followed by MTT assay and determination of IC50. The results shown were from six replicate determinations (* p<0.05).

Figure 5. Effect of mutations on MRP1/ABCC1-mediated MDR in CHO-K1 cells.

CHO-K1 cells stably transfected with vector, wild-type, or Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln, and Arg1058Gln mutant MRP1/ABCC1 were exposed to cisplatin, paclitaxel, etoposide, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, methotrexate, vinblastine, and vincristine at various concentrations for 72 hrs at 37°C followed by MTT assay and determination of IC50. The results shown were from six replicate determinations (* p<0.05).

Table 4.

Resistance factors of transfected HEK293 cells to chemotherapeutic agents.

| Resistance factorsa |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | WT-MRP1/ABCC1 | Cys43Ser (128G>C) | Thr73lle (218C>T) | Arg723Gln (2168G>A) | Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) |

| Cisplatin | 0.95±0.24 | 0.95±0.14 | 0.83±0.18 | 0.76±0.20 | 1.10±0.10 |

| Paclitaxel | 1.14±0.09 | 0.99±0.16 | 0.99±0.21 | 1.10±0.22 | 1.04±0.16 |

| Daunorubicin | 17.82±3.15 | 17.27±2.37 | 19.73±1.98 | 9.09±1.68 | 8.73±2.62 |

| Doxorubicin | 14.38±0.75 | 15.13±0.91 | 14.63±1.52 | 3.63±1.20 | 2.38±1.03 |

| Etoposide | 12.65±2.09 | 11.51±1.92 | 13.08±1.84 | 4.41±0.67 | 6.65±1.05 |

| Methotrexate | 10.80±1.33 | 10.50±1.58 | 6.70±0.95 | 6.20±0.90 | 10.70±1.26 |

| Vinblastine | 5.44±1.36 | 5.72±1.60 | 5.64±1.04 | 2.80±1.26 | 5.44±1.62 |

| Vincristine | 11.35±3.11 | 11.17±2.91 | 8.89±2.40 | 3.76±1.15 | 11.18±2.82 |

Resistance factors=IC50 of wild-type or mutant MRP1/ABCC1 transfected cells/IC50 of empty vector control transfected cells.

Table 5.

Resistance factors of transfected CHO-K1 cells to chemotherapeutic agents.

| Resistance factora |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs | WT-MRP1/ABCC1 | Cys43Ser (128G>C) | Thr73lle (218C>T) | Arg723Gln (2168G>A) | Arg1058Gln (3173G>A) |

| Cisplatin | 0.94±0.05 | 0.98±0.12 | 0.89±0.04 | 0.99±0.09 | 0.89±1.10 |

| Paclitaxel | 0.94±0.11 | 0.88±0.10 | 0.96±0.05 | 1.00±0.07 | 0.96±0.06 |

| Daunorubicin | 12.97±2.76 | 13.09±2.68 | 13.07±2.81 | 2.96±0.58 | 4.81±1.01 |

| Doxorubicin | 15.44±1.37 | 15.84±0.91 | 15.44±1.95 | 6.46±0.90 | 7.22±0.86 |

| Etoposide | 16.57±1.91 | 16.44±1.95 | 4.84±0.51 | 3.56±0.36 | 4.77±0.56 |

| Methotrexate | 3.78±1.07 | 3.70±1.01 | 3.60±1.39 | 3.75±1.08 | 1.67±0.53 |

| Vinblastine | 10.35±1.61 | 10.32±1.70 | 10.27±1.66 | 5.73±0.87 | 8.50±1.32 |

| Vincristine | 6.93±1.13 | 6.78±1.18 | 6.79±1.04 | 2.27±0.34 | 6.85±1.14 |

Resistance factors=IC50 of wild-type or mutant MRP1/ABCC1 transfected cells/IC50 of empty vector control transfected cells.

The Cys43Ser mutation does not appear to have any effect on the activity of MRP1/ABCC1 in conferring resistance to all the drugs tested in either of the cell lines used (Figs. 4 and 5, Tables 4 and 5). In HEK293 cells, Arg723Gln confers lower resistance to all drugs compared with wild-types. In CHO-K1 cells, Arg723Gln also significantly decreased resistance to all drugs except cisplatin, paclitaxel and methotrexate when compared with wild-type MRP1/ABCC1. The Arg1058Gln mutant caused a significant decrease in resistance to anthracyclines and etoposide in HEK293 cells. In CHO-K1 cells, the Arg1058Gln mutant also conferred lower resistance to vinblastine, methotrexate, anthracyclines and etoposide. In HEK293 cells, the Thr73Ile mutation was also found to cause less resistance to vincristine and methotrexate (Tables 4, 5 and Figure 4). However, in CHO-K1 cells, this mutation only caused changes in resistance to etoposide.

Discussion

In this study, we identified the allelic frequencies of Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile, Arg723Gln and Arg1058Gln in a mainland Chinese population. These allelic frequencies are not very high in Chinese and these mutations do not appear to affect the expression level and trafficking of MRP1/ABCC1. However, the study discovered that Arg723Gln can diminish the resistance activity of MRP1/ABCC1 to daunorubicin, doxorubicin, etoposide, vinblastine and vincristine. In addition, Arg1058Gln can reduce drug resistance of etoposide, daunorubicin, and doxorubicin. Thus, patients with these polymorphisms may respond to chemotherapy differently.

This study shows for the first time the frequencies of nonsynonymous mutations, Cys43Ser, Thr73lle, Arg723Gln and Arg1058Gln, in a large sample of healthy volunteers from mainland China. In the 208 Chinese subjects enrolled in this study, few had Cys43Ser, Thr73Ile and Arg1058Gln polymorphisms. Their allelic frequencies were 0.5%, 1.4% and 0.5%, respectively. These results indicate that these three SNPs are rare polymorphisms in the Chinese population. However, we found 22 heterozygotes and 1 homozygote in the 208 subjects for Arg723Gln. All of these frequencies observed in the Chinese population are similar to those in the Japanese population [12, 16]. Our observation is also consistent with data reported from other populations in Asia, including Malay and Indian populations [15] (Table 3). However, the frequencies of the Arg723Gln A allele and the Thr73Ile T allele in the Chinese population were higher than the Caucasians (P<0.05) of whom these alleles have not been found. In contrast, Arg723Gln has the highest frequency in Asian populations. Thus, it is likely that there is a difference in the distribution of MRP1/ABCC1 polymorphisms between Asian and Caucasian populations. It has also been reported that Gly671Val and Arg433Ser mutations were found in Caucasian, but not in Asian populations [15, 18, 19].

Previously, the mutations of some amino acid residues by site-directed mutagenesis have been found to affect the expression of MRP1/ABCC1 [22]. Using transient transfection in four different cell lines, we found that none of the four SNP mutations affect the expression of MRP1/ABCC1. Therefore, these four amino acids may not be essential to the stability of MRP1/ABCC1 mRNA and protein, consistent with a study by Letourneau et al. [13].

The four SNPs (Cys43Ser, Thr73lle, Arg723Gln and Arg1058Gln) studied here are located in various domains of human MRP1/ABCC1. Although the location of SNPs in protein has not always been an accurate predictor of phenotypic change in the expression or function of the protein [18, 19], the location of Arg723Gln in the NBD1 suggests that this mutation likely would affect the function of the protein by affecting the ATPase activity of MRP1/ABCC1. Indeed, we found that Arg723Gln mutation decreased the cell's resistance to nearly all drugs tested in HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells (see also discussion in the last paragraph). Interestingly, Arg723Gln is also the most commonly found nonsynonymous SNP of the four SNPs in Chinese and other Asian populations. It will be interesting to determine in future studies if this SNP affects the responses of cancer patients to cancer chemotherapy in Asian populations.

Sequence comparison among MRP1/ABCC1s of different species showed that Arg1058 and Cys43 are the most conserved residues of the four residues with SNPs studied here. Nonetheless, their drug resistance profiles were rather different: Arg1058Gln mutation decreased resistance to several anticancer drugs, whereas Cys43Ser mutation did not significantly affect resistance to any drugs tested. Thus, the degree to which the mutated amino acid is conserved in MRP1/ABCC1 is not an accurate predictor of functional change. In a previous study, however, the Cys43Ser mutation did appear to cause a decrease in resistance to vincristine in HeLa cells [20]. The reason for the difference between these two studies is not known, however, considering that different cell lines may have different impacts on the effect of mutations on MRP1/ABCC1 function (see also discussion in the next paragraph), it is tempting to speculate that HeLa cells behave differently than HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells regarding the effect of Cys43Ser mutation on MRP1/ABCC1 function.

The Arg1058Gln mutation can increase the response of two anthracyclines and etoposides in HEK293 and CHO-K1 cells as well as vinblastine and methotrexate in CHO-K1 cells. This amino acid is located in the 7th cytoplasmic loop between TM13 and TM14. The selective effect on drug resistance also exists for the Thr73Ile mutation in the first cytoplasmic loop. It reduced methotrexate resistance in HEK293 cells and etoposide resistance in CHO-K1 cells. The selective effect of these SNPs on resistance to different drugs suggests that these loops may play important roles in drug substrate specificity as previously suggested [7, 23, 24].

It is also noteworthy that the effect of some of the mutations on the function of MRP1/ABCC1 is different in the two cell lines tested in this study. For example, the Thr73Ile mutation decreased vinblastine resistance in CHO-K1 cells, but not in HEK293 cells. Currently, it is not known what causes this difference. However, we speculate that different cells may have different factors that can affect the function of mutant MRP1/ABCC1. It is possible that HEK293 cells are able to suppress the Thr73Ile mutation-induced changes in both MRP1/ABCC1 structure and activity. These observations also implicate that different SNPs in different cancers may cause different changes in responses to the same chemotherapeutic drugs. We will address these hypotheses in future studies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 30572230 and 30873089, the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China grant 08JJ3058, and by the National Institutes of Health grants CA113384 (JTZ) and CA120211 (JTZ). Professional editorial proof reading by Jeff Russ is appreciated.

References

- 1.Breuninger LM, Paul S, Gaughan K, Miki T, Chan A, Aaronson SA, et al. Expression of multidrug resistance-associated protein in NIH/3T3 cells confers multidrug resistance associated with increased drug efflux and altered intracellular drug distribution. Cancer Res. 1995;55(22):5342–5347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stride BD, Grant CE, Loe DW, Hipfner DR, Cole SP, Deeley RG. Pharmacological characterization of the murine and human orthologs of multidrug-resistance protein in transfected human embryonic kidney cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52(3):344–353. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conseil G, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Polymorphisms of MRP1 (ABCC1) and related ATP-dependent drug transporters. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(8):523–533. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000167333.38528.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruh GD, Belinsky MG. The MRP family of drug efflux pumps. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7537–7552. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cole SP, Bhardwaj G, Gerlach JH, Mackie JE, Grant CE, Almquist KC, et al. Overexpression of a transporter gene in a multidrug-resistant human lung cancer cell line. Science. 1992;258(5088):1650–1654. doi: 10.1126/science.1360704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins CF, Linton KJ. The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(10):918–926. doi: 10.1038/nsmb836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deeley RG, Cole SP. Substrate recognition and transport by multidrug resistance protein 1 (ABCC1). FEBS Lett. 2006;580(4):1103–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeGorter MK, Conseil G, Deeley RG, Campbell RL, Cole SP. Molecular modeling of the human multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1). Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Liu Y, Dong Z, Xu J, Peng H, Liu Z, et al. Regulation of function by dimerization through the amino-terminal membrane-spanning domain of human ABCC1/MRP1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(12):8821–8830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700152200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu ZQ, Zhu B, Tan YF, Tan ZR, Wang LS, Huang SL, et al. O-Dealkylation of fluoxetine in relation to CYP2C19 gene dose and involvement of CYP3A4 in human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300(1):105–111. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, He YJ, Gan Z, Fan L, Li Q, Wang A, et al. OATP1B1 polymorphism is a major determinant of serum bilirubin level but not associated with rifampicin-mediated bilirubin elevation. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34(12):1240–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito S, Iida A, Sekine A, Miura Y, Ogawa C, Kawauchi S, et al. Identification of 779 genetic variations in eight genes encoding members of the ATP-binding cassette, subfamily C (ABCC/MRP/CFTR. J Hum Genet. 2002;47(4):147–171. doi: 10.1007/s100380200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Letourneau IJ, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Functional characterization of non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene encoding human multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1). Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(9):647–657. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000173484.51807.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moriya Y, Nakamura T, Horinouchi M, Sakaeda T, Tamura T, Aoyama N, et al. Effects of polymorphisms of MDR1, MRP1, and MRP2 genes on their mRNA expression levels in duodenal enterocytes of healthy Japanese subjects. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25(10):1356–1359. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Sew PH, Ambrose H, Ryan S, Chong SS, Lee EJ, et al. Nucleotide sequence analyses of the MRP1 gene in four populations suggest negative selection on its coding region. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito S, Ieiri I, Tanabe M, Suzuki A, Higuchi S, Otsubo K. Polymorphism of the ABC transporter genes, MDR1, MRP1 and MRP2/cMOAT, in healthy Japanese subjects. Pharmacogenetics. 2001;11(2):175–184. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Hao B, Zhou K, Chen X, Wu S, Zhou G, et al. Linkage disequilibrium and haplotype architecture for two ABC transporter genes (ABCC1 and ABCG2) in Chinese population: implications for pharmacogenomic association studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2004;68(Pt 6):563–573. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2003.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conrad S, Kauffmann HM, Ito K, Leslie EM, Deeley RG, Schrenk D, et al. A naturally occurring mutation in MRP1 results in a selective decrease in organic anion transport and in increased doxorubicin resistance. Pharmacogenetics. 2002;12(4):321–330. doi: 10.1097/00008571-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conrad S, Kauffmann HM, Ito K, Deeley RG, Cole SP, Schrenk D. Identification of human multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1) mutations and characterization of a G671V substitution. J Hum Genet. 2001;46(11):656–663. doi: 10.1007/s100380170017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leslie EM, Letourneau IJ, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Functional and structural consequences of cysteine substitutions in the NH2 proximal region of the human multidrug resistance protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1). Biochemistry. 2003;42(18):5214–5224. doi: 10.1021/bi027076n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Y, Chen Q, Zhang JT. Structural and functional consequences of mutating cysteine residues in the amino terminus of human multidrug resistance-associated protein 1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(46):44268–44277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Situ D, Haimeur A, Conseil G, Sparks KE, Zhang D, Deeley RG, et al. Mutational analysis of ionizable residues proximal to the cytoplasmic interface of membrane spanning domain 3 of the multidrug resistance protein, MRP1 (ABCC1): glutamate 1204 is important for both the expression and catalytic activity of the transporter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(37):38871–38880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403832200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noguchi T, Ren XQ, Aoki S, Igarashi Y, Che XF, Nakajima Y, et al. MRP1 mutated in the L0 region transports SN-38 but not leukotriene C4 or estradiol-17 (beta-D-glucuronate). Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70(7):1056–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conseil G, Deeley RG, Cole SP. Role of two adjacent cytoplasmic tyrosine residues in MRP1 (ABCC1) transport activity and sensitivity to sulfonylureas. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69(3):451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]