Abstract

The transcription factor ΔFosB accumulates and persists in brain in response to chronic stimulation. This accumulation after chronic exposure to drugs of abuse has been demonstrated previously by Western blot most dramatically in striatal regions, including dorsal striatum (caudate/putamen) and nucleus accumbens. In the present study, we used immunohistochemistry to define with greater anatomical precision the induction of ΔFosB throughout the rodent brain after chronic drug treatment. We also extended previous research involving cocaine, morphine, and nicotine to two additional drugs of abuse, ethanol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC, the active ingredient in marijuana). We show here that chronic, but not acute, administration of each of four drugs of abuse, cocaine, morphine, ethanol, and Δ9-THC, robustly induces ΔFosB in nucleus accumbens, although different patterns in the core vs. shell subregions of this nucleus were apparent for the different drugs. The drugs also differed in their degree of ΔFosB induction in dorsal striatum. In addition, all four drugs induced ΔFosB in prefrontal cortex, with the greatest effects observed with cocaine and ethanol, and all of the drugs induced ΔFosB to a small extent in amygdala. Furthermore, all drugs induced ΔFosB in the hippocampus, and, with the exception of ethanol, most of this induction was seen in the dentate. Lower levels of ΔFosB induction were seen in other brain areas in response to a particular drug treatment. These findings provide further evidence that induction of ΔFosB in nucleus accumbens is a common action of virtually all drugs of abuse and that, beyond nucleus accumbens, each drug induces ΔFosB in a region-specific manner in brain.

Keywords: cocaine, morphine, ethanol, Δ9-THC, striatum, nucleus accumbens

INTRODUCTION

Acute exposure to cocaine causes the transient induction of the transcription factors c-Fos and FosB in striatal regions (Graybiel et al., 1990; Hope et al., 1992; Young et al., 1991), whereas chronic exposure to the drug results in the accumulation of stabilized isoforms of ΔFosB, a truncated splice variant of the fosB gene (Hiroi et al., 1997; Hope et al., 1994; Moratalla et al., 1996; Nye et al., 1995). Once induced, ΔFosB persists in these regions for several weeks due to the unusual stability of the protein. More recent research has shown that ΔFosB’s stability is mediated by the absence of degron domains found in the C-termini of full-length FosB and all other Fos family proteins (Carle et al., 2007) and by the phosphorylation of ΔFosB at its N-terminus (Ulery et al., 2006). In contrast, chronic drug administration does not alter the splicing of fosB premRNA into ΔfosB mRNA nor the stability of the mRNA (Alibhai et al., 2007), which further indicates that the accumulation of ΔFosB protein is the predominant mechanism involved.

Growing evidence indicates that ΔFosB induction in striatal regions, in particular, the ventral striatum or nucleus accumbens, is important in mediating aspects of addiction. Overexpression of ΔFosB in these regions of inducible bitransgenic mice, or via viral-mediated gene transfer, increases an animal’s sensitivity to the locomotor-activating and rewarding effects of cocaine and of morphine, whereas expression of a dominant negative antagonist of ΔFosB (termed Δc-Jun) has the opposite effects (Kelz et al., 1999; McClung and Nestler, 2003; Peakman et al., 2003; Zachariou et al., 2006). ΔFosB overexpression has also been shown to increase incentive motivation for cocaine (Colby et al., 2003). Moreover, ΔFosB is preferentially induced by cocaine in adolescent animals, which may contribute to their increased vulnerability to addiction (Ehrlich et al., 2002).

Despite this evidence, important questions remain. Although chronic administration of several other drugs of abuse, including amphetamine, methamphetamine, morphine, nicotine, and phencyclidine, have been reported to induce ΔFosB in striatal regions (Atkins et al., 1999; Ehrlich et al., 2002; McDaid et al. 2006b; Muller and Unterwald, 2005; Nye et al., 1995; Nye and Nestler, 1996; Pich et al. 1997; Zachariou et al., 2006), little or no information is available concerning the actions of ethanol and Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (Δ9-THC, the active ingredient in marijuana). Two prior studies showed that FosB-like immunoreactivity is induced in hippocampus and certain other brain areas during ethanol withdrawal, but it remains uncertain whether this immunoreactivity represents ΔFosB or full-length FosB (Bachtell et al., 1999; Beckmann et al., 1997). Study of ethanol and (Δ9-THC are particularly important, because these are two of the most widely used drugs of abuse in the US today (SAMHSA, 2005). Moreover, although stimulant or opiate drugs of abuse have been shown to induce ΔFosB in certain other isolated brain regions, which, in addition to nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum, include prefrontal cortex, amygdala, ventral pallidum, ventral tegmental area, and hippocampus (Liu et al., 2007; McDaid et al., 2006a,2006b; Nye et al., 1995; Perrotti et al., 2005), there has not been a systematic mapping of ΔFosB induction in brain in response to chronic drug exposure.

The goal of the present study was to use immunohistochemical procedures to map the induction of ΔFosB throughout brain after chronic administration of four prototypical drugs of abuse: cocaine, morphine, ethanol, and Δ9-THC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All experiments were conducted using male Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River, Kingston, 250–275 g). Animals were housed two per cage and habituated to the animal room conditions for one week before experiments commenced. They had free access to food and water. Experiments were conducted according to protocols reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas.

Drug treatments

Chronic cocaine

Rats (n = 6 per group) received twice-daily injections of cocaine hydrochloride (15 mg/kg i.p.; National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD) dissolved in 0.9% saline for 14 days. Control rats (n = 6 per group) received i.p. injections of 0.9% saline under the same chronic procedure. All injections were given in the animals’ home cages. This treatment regimen has been shown to produce robust behavioral and biochemical adaptations (see Hope et al., 1994).

Cocaine self-administration

Animals (n = 6 per group) were trained to press a lever for a 45 mg sucrose pellet. After this training, the animals were fed ad libitum and surgically implanted under pentobarbital anesthesia with a chronic jugular catheter (Silastic tubing, Green Rubber, Woburn, MA) as described previously (Sutton et al., 2000). The catheter passed subcutaneously to exit the back through a 22-gauge cannula (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA), embedded in cranioplastic cement, and secured with Marlex surgical mesh (Bard, Cranston, RI). Self-administration was conducted in operant test chambers (Med Associates, St. Alban, VT) that were contextually distinct from the animal’s home cage and located in a different room. Each chamber was enclosed in a sound-attenuating cubicle equipped with an infusion pump assembly consisting of a Razel Model A pump (Stamford, CT) and a 10 ml glass syringe connected to a fluid swivel (Instech, Plymouth Meeting, PA) by Teflon tubing. Tygon tubing connected the swivel to the animal’s catheter assembly and was enclosed by a metal spring. Each operant chamber contained two levers (4 × 2 cm2, located 2 cm off the floor). During self-administration training, a single 20 g lever-press on the active lever delivered an i.v. infusion of cocaine (0.5 mg/kg per 0.1 ml infusion) over a 5-s infusion interval. The infusion was followed by a 10-s time-out period, during which the house light was extinguished and responding produced no programmed consequences. Illumination of the house light signaled the end of the time-out period. Lever-press on the inactive lever produced no consequence. Animals self-administered cocaine during 14 daily 4-h test sessions (6 days/week) during their dark cycle; average daily intake was ~50 mg/kg. A group of yoked animals were handled identically only they received cocaine infusions when their self-administering counterparts received drug. A group of saline control animals were allowed to lever press for saline infusions. This treatment regimen has been shown to produce robust behavioral and biochemical adaptations (see Sutton et al., 2000).

Chronic morphine

Morphine pellets (each containing 75 mg of morphine base; National Institute on Drug Abuse) were implanted s.c. once daily for 5 days (n = 6). Control rats underwent sham surgery for 5 consecutive days (n = 6). This treatment regimen has been shown to produce robust behavioral and biochemical adaptations (see Nye and Nestler, 1996).

Δ9-THC

Δ9-THC were dissolved in a 1:1:18 solution of ethanol, emulphor, and saline. Mice were injected subcutaneously twice daily with Δ9-THC, or vehicle for 15 days. Initial dose of Δ9-THC was 10 mg/kg and the dose was doubled every three days to final dose of 160 mg/kg. We used mice for Δ9-THC, because this treatment regimen has been shown to produce robust behavioral and biochemical adaptations in this species (Sim-Selley and Martin, 2002).

Ethanol

Ethanol (from 95% stock; Aaper, Shelbyville, KY) was administered by means of a nutritionally complete liquid diet. This standard dietary ethanol procedure involves administration of 7% [weight/volume (wt/vol)] ethanol in a lactalbumin/dextrose-based diet for 17 days, during which time rats generally consume ethanol at 8–12 g/kg/day and achieve blood ethanol levels up to 200 mg/dl (Criswell and Breese, 1993; Frye et al., 1981; Knapp et al., 1998). The diet was nutritionally complete (with concentrations of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients derived from ICN Research Diets and calorically balanced (with dextrose) across ethanol-treated rats and control rats. Intake matching was achieved by giving the control diet-treated rats a volume of diet equivalent to the average intake of the ethanol diet-treated rats the day before. Both groups readily gained weight during the ethanol exposure period (not shown). This treatment regimen has been shown to produce robust behavioral and biochemical adaptations (see Knapp et al., 1998).

Immunohistochemistry

Eighteen to 24 h after their last treatment, animals were deeply anesthetized with chloral hydrate (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and intracardially perfused with 200 ml of 10 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 400 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were removed and stored overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. The next morning, brains were transferred to a 20% glycerol in 0.1 M PBS solution for cryoprotection. Coronal sections (40 µm) were cut on a freezing microtome (Leica, Bannockburn, IL) and then processed for immunohistochemistry. ΔFosB and FosB immunoreactivities were detected using two different rabbit polyclonal antisera. One antiserum, raised against the FosB C-terminus that is absent in ΔFosB (aa 317–334) recognizes full-length FosB, but not ΔFosB (Perrotti et al., 2004). The other antiserum, a “pan-FosB” antibody, was raised against an internal region of FosB and recognizes both FosB and ΔFosB (s.c.−48; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA).

FosB-like staining was revealed by use of the avidin-biotin peroxidase complex method. For this procedure, brain sections were first treated with 0.3% H2O2 to destroy endogenous peroxidases and then incubated for 1 h in 0.3% Triton X-100 and 3% normal goat serum to minimize nonspecific labeling. Tissue sections were then incubated overnight at room temperature in 1% normal goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 and pan-FosB antibody (1:5000). Sections were washed, placed for 1.5 h in 1:200 dilution of biotinylated goat-antirabbit immunoglobulin (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA), washed, and placed for 1.5 h in 1:200 dilution of avidin–biotin complex from the Elite kit (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Peroxidase activity was visualized by reaction with diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories). Coded slides were used to count the number of FosB-immunoreactive cells. The code was not broken until analysis of an individual experiment was complete.

Once FosB-like immunoreactivity was detected, double fluorescent labeling with the FosB-specific (C-terminus; 1:500) antibody and pan-FosB antibody (s.c.−48; 1:200) was conducted to determine if the induced protein was indeed ΔFosB. A published protocol was used (Perrotti et al., 2005). The proteins were visualized using CY2 and CY3 fluorophore-labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Localization of protein expression was performed on a confocal microscope (Axiovert 100; LSM 510 with META emission wavelengths of 488, 543, and 633; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY). Images presented here were captured on this system and represent a 1 µm-thick section through a Z-plane.

Statistical analysis

Significant induction of ΔFosB+ cells was assessed using t-tests or one-way ANOVAs followed by Newman-Keuls test as post hoc analysis. All analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Induction of ΔFosB in brain

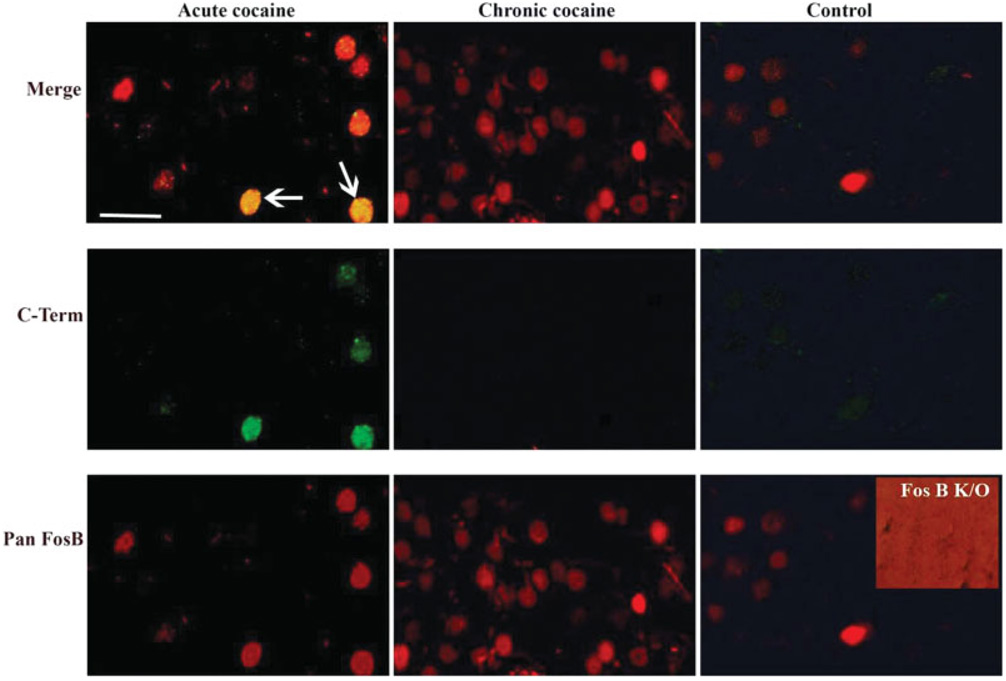

To directly compare the patterns of ΔFosB induction in brain in response to different types of drugs of abuse, we administered four prototypical drugs, cocaine, morphine, ethanol, and Δ9-THC, and examined ΔFosB expression 18–24 h after the last drug exposure. We used standard drug treatment regimens, which have been demonstrated in the literature to produce behavioral and biochemical sequelae of chronic drug exposure (see Materials and Methods section). Levels of ΔFosB were quantified by immunohistochemistry, with a focus on midbrain and fore-brain regions implicated in drug reward and addiction. This fine mapping of ΔFosB induction was performed with a pan-FosB antibody, which recognizes both ΔFosB and full-length FosB. However, we know that all of the immunoreactivity observed, for each of the drugs, is due solely to ΔFosB, since an antibody selective for full-length FosB (see Material and Methods section) detected no positive cells. Moreover, all immunoreactivity detected by the pan-FosB antibody was lost in fosB knockout mice, which confirms the specificity of this antibody for fosB gene products as opposed to other Fos family proteins. These controls are shown for cocaine in Figure 1, but were observed for all other drugs as well (not shown). These findings are not surprising, because at the 18–24 h time point used in this study all of the full-length FosB, induced by the last drug administration, would be expected to degrade, leaving the more stable ΔFosB as the only fosB gene product remaining (see Chen et al., 1995; Hope et al., 1994).

Fig. 1.

Double-labeling fluorescence immunohistochemistry using the anti-FosB (pan-FosB, Santa-Cruz) or anti-FosB (C-terminus) antibody through the nucleus accumbens of animals treated with acute or chronic cocaine and a control rat. The pan-FosB antibody stains both ΔFosB and FosB-positive nuclei (note nuclei from acute cocaine treatment stain with this antibody in green, and double stain with both antibodies “merge” row), whereas the C-terminus antibody stains FosB-positive nuclei only (note the absence of labeling in chronic cocaine tissue labeled with this antibody). All nuclei in the chronic cocaine-treated tissue are ΔFosB positive as they are stained only with the pan-FosB antibody and not with the C-terminal antibody. The inset shows a nucleus accumbens section from a fosB knockout mouse stained with the pan-FosB antibody; the lack of staining demonstrates the specificity of the antibody for fosB gene products. The background on this panel is intensified to demonstrate that no staining (brighter red) was observed. Scale bar = 50 µm.

A summary of the overall findings of this study is provided in Table I. Each of the four drugs was found to significantly induce ΔFosB in brain, although with partly distinct patterns of induction seen for each drug.

Table I.

Induction of ΔFosB in brain by drugs of abuse

| Brain region | Control | Cocaine | Morphine | Δ9-THC | Ethanol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrontal cortex | − | ++ | +++ | ++ | +++ |

| Dorsal striatum | + | +++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ |

| Nucleus accumbens | |||||

| Core | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | ++++ |

| Shell | + | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| Lateral septum | − | + | − | − | + |

| Medial septum | − | − | − | − | − |

| BNST | − | + | + | + | ++ |

| IPAC | − | ++ | + | ++ | +++ |

| Hippocampus | |||||

| Dentate gyrus | + | +++ | +++ | +++ | + |

| CA1 | − | +++ | + | + | ++ |

| CA3 | − | ++ | ++ | + | ++ |

| Amygdala | |||||

| Basolateral | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Central | − | +++ | ++ | ++ | + |

| Medial | − | + | + | + | + |

| PAG | − | + | + | − | + |

| VTA | − | + | − | − | − |

| SN | − | − | − | − | − |

A semi-quantitative analysis of levels of ΔFosB in several representative brain regions under control conditions and after chronic administration of four prototypical drugs of abuse is shown. The data were derived from the analysis of multiple tissue sections from at least four rats in each treatment group. ΔFosB levels were rated using the following scale: −, <100 ΔFosB + nuclei/mm2; +, <200 ΔFosB nuclei; ++, <300 ΔFosB + nuclei; +++, <400 ΔFosB + nuclei; ++++, ≥400 ΔFosB + nuclei. BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis; IPAC, interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure; PAG, periaqueductal gray; VTA, ventral tegmental area; SN, substantia nigra.

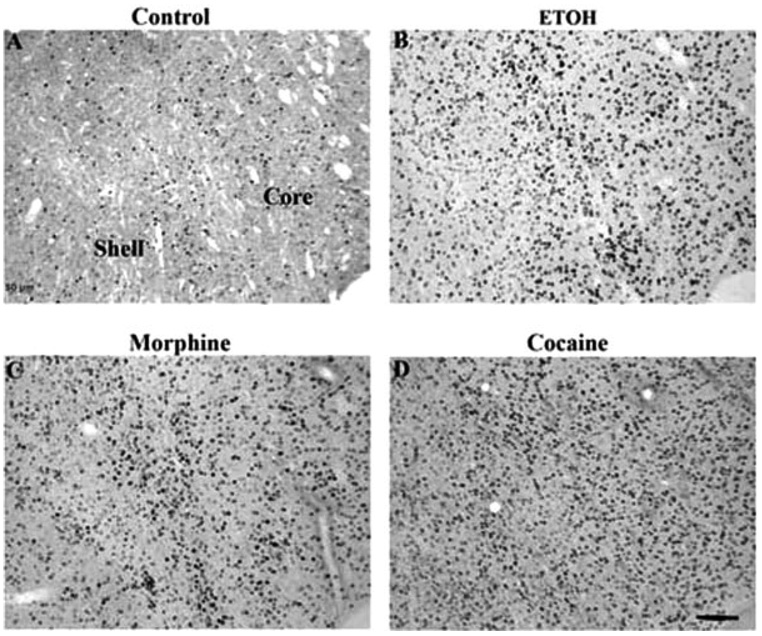

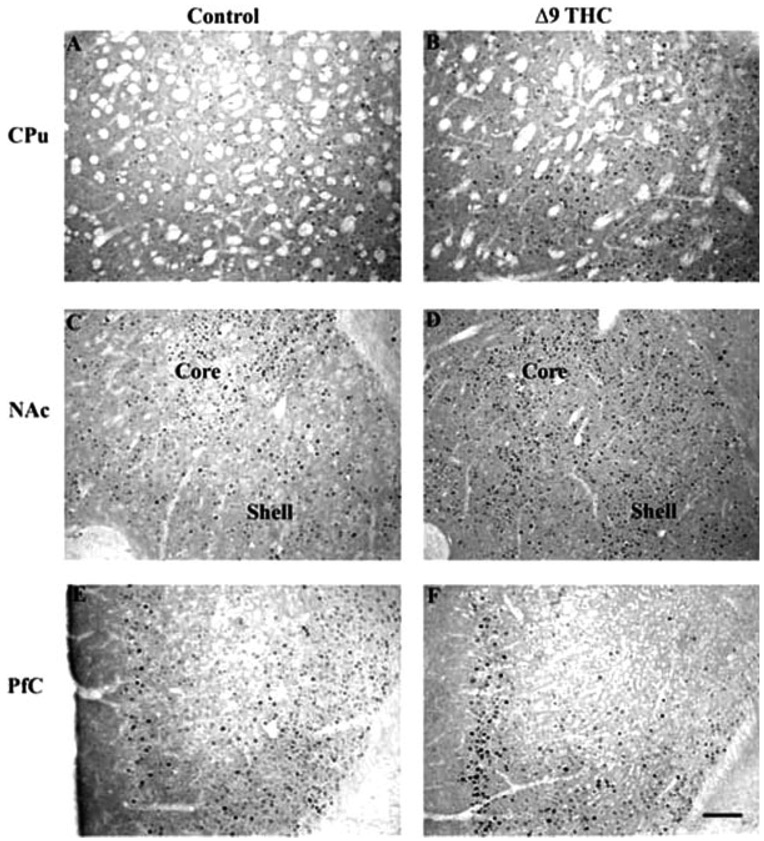

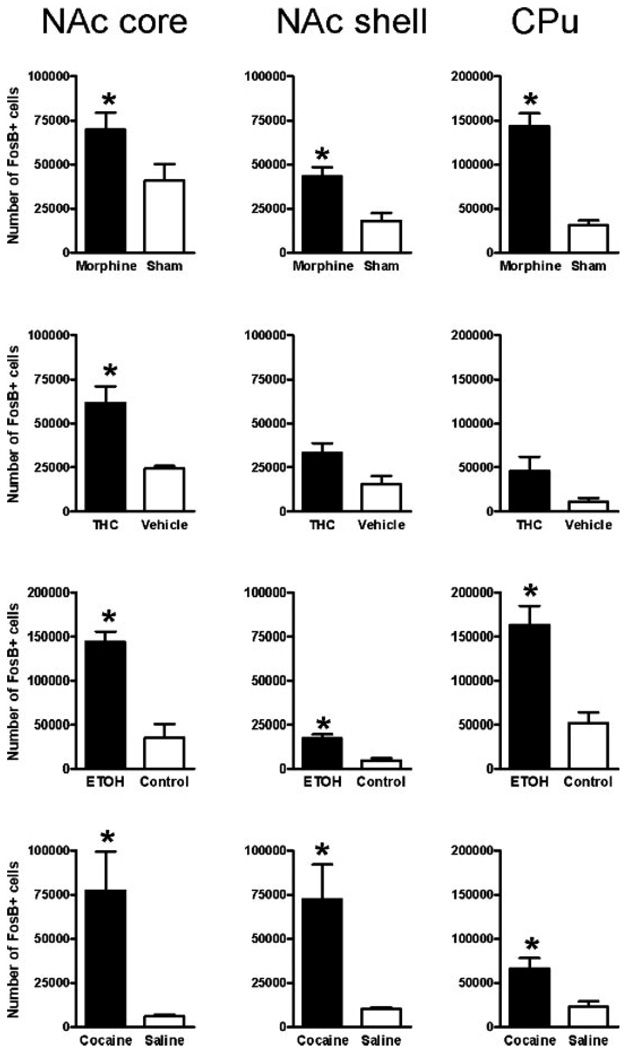

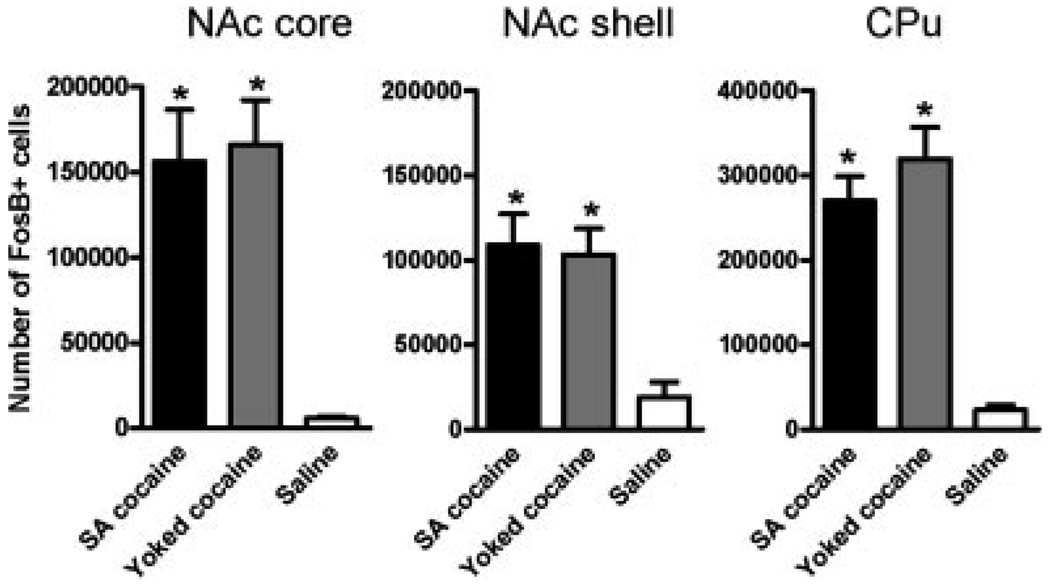

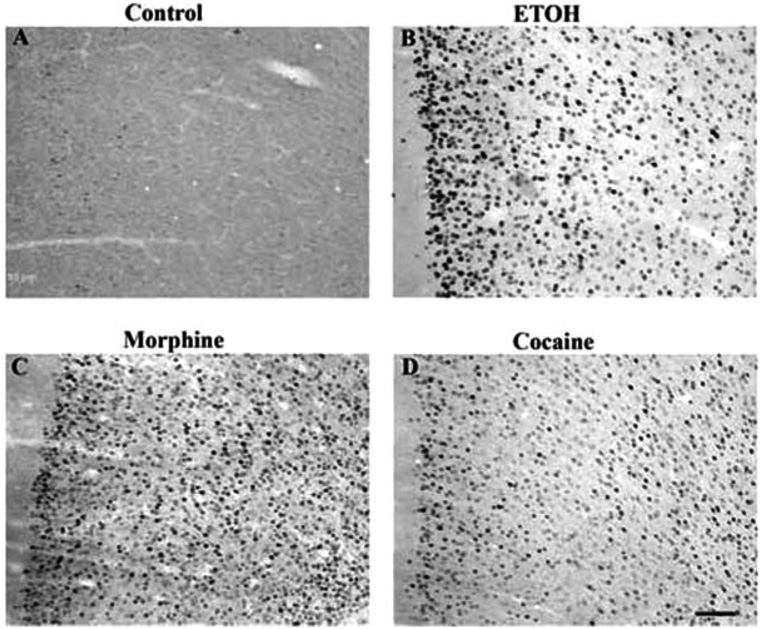

Induction of ΔFosB in striatal regions

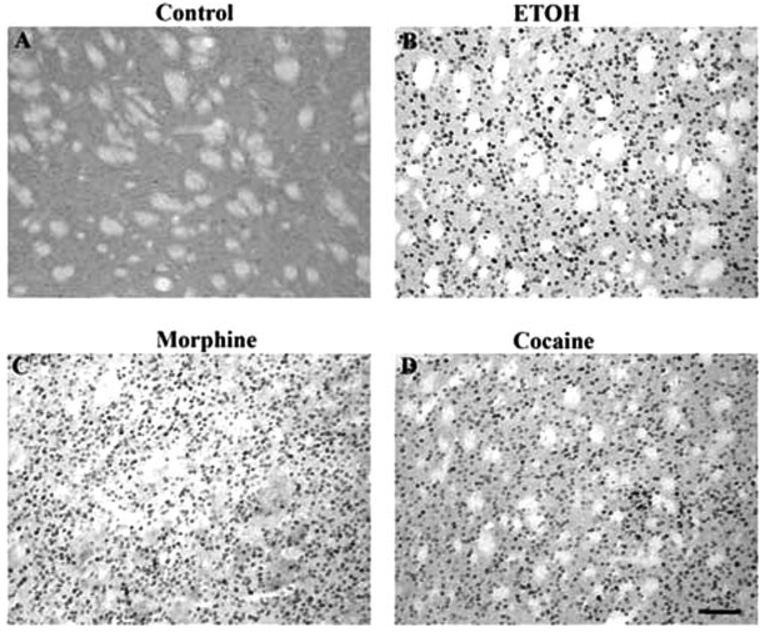

The most dramatic induction of ΔFosB was seen in the nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum (caudate/putamen), where all four drugs induced the protein (Fig. 2–Fig. 4). This is shown quantitatively in Figure 5. ΔFosB induction was seen in both the core and shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens, with marginally more induction seen in the core for most of the drugs. Robust induction of ΔFosB was also observed in the dorsal striatum for most of the drugs. An exception was Δ9-THC, which did not significantly induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens shell or dorsal striatum despite strong trends (see Fig. 4; Table I). Interestingly, ethanol produced the greatest induction of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens core compared to the other treatments.

Fig. 2.

Induction of ΔFosB in the rat nucleus accumbens in a control rat (A) or after chronic treatment with ethanol (B), morphine (C), or cocaine (D). Levels of FosB-like immunoreactivity were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using a pan-FosB antibody. Labeling with the C-terminus antibody revealed no positive cells (not shown). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Fig. 4.

Induction of ΔFosB in mouse brain after chronic Δ9-THC treatment. Levels of FosB-like immunoreactivity were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using a pan-FosB antibody in control (A, C, E) and chronic Δ9-THC (B, D, F) animals. Note that chronic Δ9-THC treatment increased FosB-like immunoreactivity in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) core and shell, caudate putamen (CPu; A, B), and prefrontal cortex (PfC; E, F). Note that ΔFosB induction in striatal regions reached statistical significance for NAc core only, despite strong trends in the NAc shell and CPu as shown in the figure (see Fig. 5). Labeling with the C-terminus antibody revealed no positive cells (not shown). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Fig. 5.

Quantification of ΔFosB induction in striatal regions after chronic morphine, Δ9-THC, ethanol, and cocaine treatments. The bar graphs show the mean number of ΔFosB+ cells in control animals and in animals subjected to chronic morphine, Δ9-THC, ethanol, or cocaine treatments in the core and shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and in the dorsal striatum (caudate-putamen, CPu). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6–10 animals in each group). *P < 0.05 by t-test.

Induction of ΔFosB by volitional versus forced drug exposure

Given the dramatic induction of ΔFosB in striatal regions, we were interested in determining whether the ability of a drug to induce the protein in these regions varied as a function of volitional versus forced drug exposure. To address this question, we studied a group of rats that self-administered cocaine for 14 days and compared ΔFosB induction in these animals to those that received yoked infusions of cocaine and those that received saline only. As shown in Figure 6, self-administered cocaine robustly induced ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens (both the core and shell sub-regions) and dorsal striatum, with equivalent degrees of induction seen for self-administered versus yoked-administered drug. The extent of ΔFosB induction seen in these two groups of animals was greater than that seen with i.p. injections of cocaine (see Fig. 5), presumably due to the much larger of amounts of cocaine in the self-administration experiment (daily doses: 50 mg/kg i.v. vs. 30 mg/kg i.p.).

Fig. 6.

Quantification of ΔFosB induction in striatal regions after chronic cocaine self-administration. The bar graphs show the mean number of ΔFosB+ cells in control animals and in animals subjected to the cocaine treatments, in the core and shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the dorsal striatum (caudate- putamen, CPu). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6–10 animals in each group). *P < 0.05 by t-test. Note no significant differences between self-administering animals and their yoked counterparts.

Induction of ΔFosB in other brain regions

Beyond the striatal complex, chronic administration of drugs of abuse induced ΔFosB in several other brain areas (see Table I). We should emphasize that the data presented in Table I are semiquantitative, and do not represent precise quantification of ΔFosB induction, as performed for striatal regions (Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). Nevertheless, we are confident of ΔFosB induction in these nonstriatal regions: ΔFosB is virtually undetectable in these regions under basal conditions, such that the consistent detection of ΔFosB after chronic drug exposure is statistically significant (P < 0.05 by χ2).

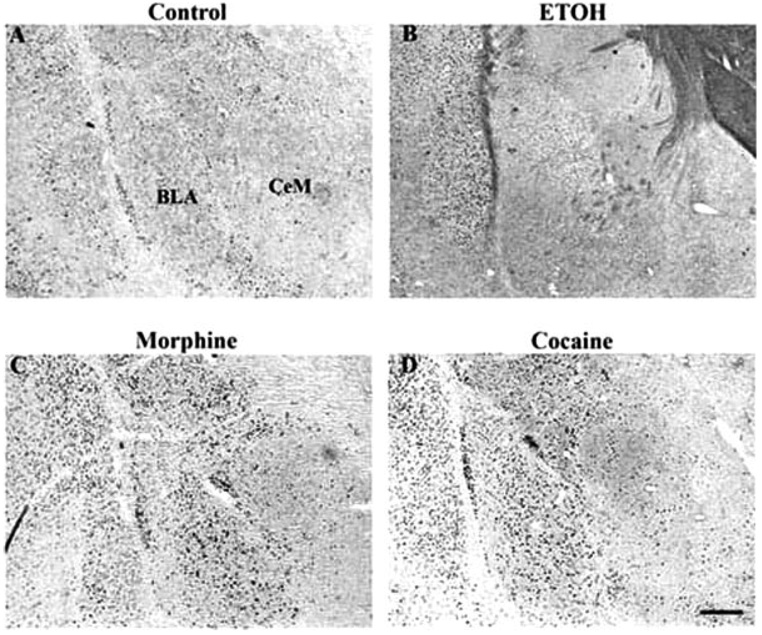

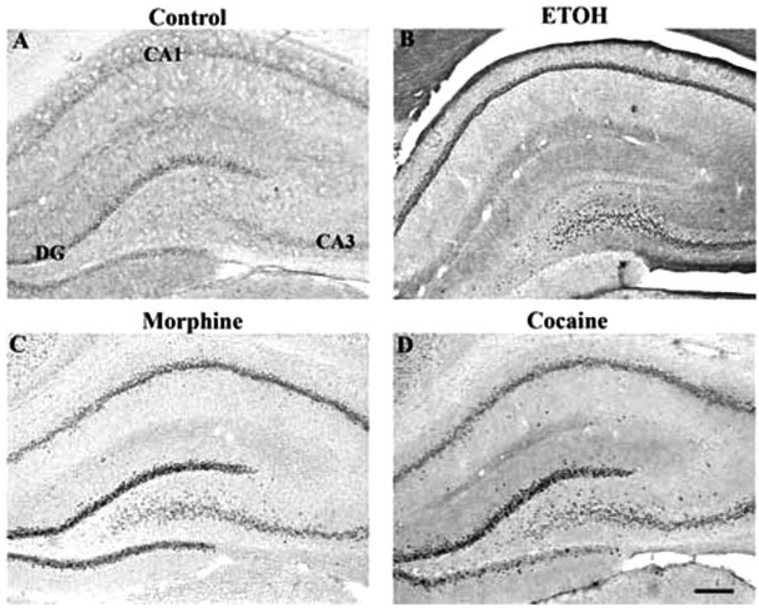

Robust induction by all drugs was seen in the prefrontal cortex, with morphine and ethanol seeming to produce the strongest effects in the most layers (Fig. 4 and Fig. 7). All four drugs also caused low levels of ΔFosB induction in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), the interstitial nucleus of the posterior limb of the anterior commissure (IPAC), and throughout the amygdala complex (Fig. 8). Additional effects, specific to particular drugs, were also observed. Cocaine and ethanol, but not morphine or Δ9-THC, appeared to induce low levels of ΔFosB in the lateral septum, with no induction seen in medial septum. All drugs induced ΔFosB in the hippocampus and, with the exception of ethanol, most of this induction was seen in the dentate gyrus (Table I and Fig. 9). In contrast, ethanol induced very little ΔFosB in dentate gyrus and instead induced high levels of the protein in the CA3-CA1 subfields. Cocaine, morphine, and ethanol, but not Δ9-THC, caused low levels of induction of ΔFosB in the periaqueductal gray, whereas only cocaine induced ΔFosB in the ventral tegmental area, with no induction seen in the sub-stantia nigra (see Table I).

Fig. 7.

Induction of ΔFosB in the prefrontal cortex in a control rat (A) or after chronic treatment with ethanol (B), morphine (C), or cocaine (D). Levels of FosB-like immunoreactivity were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using a pan-FosB antibody. Labeling with the C-terminus antibody revealed no positive cells (not shown). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Fig. 8.

Induction of ΔFosB in the basal lateral and central medial nuclei of the amygdala of a control rat (A) or in rats given chronic ethanol (B), morphine (C), or cocaine (D) treatments. Levels of FosB-like immunoreactivity were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using a pan-FosB antibody. Labeling with the C-terminus antibody revealed no positive cells (not shown). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Fig. 9.

Induction of ΔFosB in the hippocampus of a control rat (A) or in rats given chronic ethanol (B), morphine (C), or cocaine (D) treatments. Levels of FosB-like immunoreactivity were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using a pan-FosB antibody. Labeling with the C-terminus antibody revealed no positive cells (not shown). Scale bar = 50 µm.

DISCUSSION

Numerous studies have demonstrated that chronic administration of several types of drugs of abuse, including cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, morphine, nicotine, and phencyclidine, induces the transcription factor, ΔFosB, in nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum (see Introduction section for references; reviewed in McClung et al., 2004; Nestler et al., 2001). Induction of ΔFosB in striatal regions has also been observed after chronic consumption of natural rewards, such as wheel-running behavior (Werme et al., 2002). In addition, there have been several reports of lower levels of ΔFosB induction in certain other brain regions, including prefrontal cortex, amygdala, ventral pallidum, ventral tegmental area, and hippocampus (Liu et al., 2007; McDaid et al., 2006a,2006b; Nye et al., 1996; Perrotti et al., 2005), in response to some of these drugs of abuse, however, there has never been a systematic mapping of drug induction of ΔFosB in brain. Moreover, despite the investigation of most drugs of abuse, two of the most widely abused substances, ethanol and Δ9-THC, have not to date been examined for their ability to induce ΔFosB. The goal of the present study was to carry out an initial mapping of ΔFosB in brain in response to chronic administration of four prototypical drugs of abuse: cocaine, morphine, ethanol, and Δ9-THC.

The major findings of our study are that ethanol and Δ9-THC, like all other drugs of abuse, induce high levels of ΔFosB broadly within the striatal complex. These results further establish ΔFosB induction in these regions as a common, chronic adaptation to virtually all drugs of abuse (McClung et al., 2004). The pattern of induction within the striatal complex differed somewhat for the various drugs. All robustly induced ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens core, whereas all of the drugs-except for Δ9-THC-significantly induced ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens shell and dorsal striatum as well, and there were strong trends for Δ9-THC to produce similar effects in these latter regions. The nucleus accumbens core and shell are important brain reward regions, which have been shown to be critical mediators of the rewarding actions of drugs of abuse. Likewise, the dorsal striatum has been related to the compulsive or habit-like nature of drug consumption (Vanderschuren et al., 2005). Indeed, induction of ΔFosB in these regions has been shown to increase the rewarding responses to cocaine and to morphine, and to increase responses to natural rewards such as wheel-running behavior and food intake, as well (Colby et al., 2003; Kelz et al., 1999; Olausson et al., 2006; Peakman et al., 2003; Werme et al., 2003; Zachariou et al., 2006). Further work is needed to determine whether ΔFosB induction in these regions mediates similar functional adaptations in an individual’s sensitivity to the rewarding effects of other drugs of abuse.

Induction of ΔFosB in striatal regions is not a function of the volitional intake of the drug. Thus, we showed that self-administration of cocaine induced the same degree of ΔFosB in nucleus accumbens and dorsal striatum as seen in animals that received equivalent, yoked injections of the drug. These results demonstrate that ΔFosB induction in striatum represents a pharmacologic action of drugs of abuse, independent of an animal’s control over drug exposure. In striking contrast, we demonstrated recently that self-administration of cocaine induces several-fold higher levels of ΔFosB in orbitofrontal cortex compared to yoked cocaine administration (Winstanley et al., 2007). This effect was specific for orbitofrontal cortex, because equivalent levels of ΔFosB induction were seen in prefrontal cortex under these two treatment conditions. Thus, although ΔFosB induction is not related to volitional control over drug intake in striatal regions, it appears to be influenced by such motivational factors in certain higher cortical centers.

We also present semiquantitative data that all four drugs of abuse induce ΔFosB in several brain regions outside the striatal complex, although in general to a lesser extent. These other brain areas included the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, IPAC, BNST, and hippocampus. Drug induction of ΔFosB in prefrontal cortex and hippocampus may be related to some of the effects of drugs of abuse on cognitive performance, although this has yet to be investigated directly. The amygdala, IPAC, and BNST have all been implicated in regulating an individual’s responses to aversive stimuli. This raises the possibility that ΔFosB induction in these regions after chronic administration of a drug of abuse mediates drug regulation of emotional behavior well beyond reward. It will be interesting to examine these possibilities in future investigations.

The four drugs of abuse studied here also produced some drug-specific effects. Cocaine uniquely induced ΔFosB in the ventral tegmental area, as reported previously (Perrotti et al., 2005). Likewise, cocaine and ethanol uniquely induced low levels of ΔFosB in the lateral septum. Δ9-THC was unique for less dramatic effects on ΔFosB induction, compared with other drugs of abuse, in the nucleus accumbens shell and dorsal striatum, as mentioned earlier. Δ9-THC was also unique in that chronic exposure to this drug, as opposed to all of the others, did not induce low levels of ΔFosB in the periaqueductal gray. Given the role of the hippocampus and septum in cognitive function, and the role of these regions as well as the periaqueductal gray in regulating an animal’s responses to stressful situations, region- and drug-specific induction of ΔFosB in these regions could mediate important aspects of drug action on the brain.

In summary, ΔFosB induction in striatal brain reward regions has been widely demonstrated as a shared chronic adaptation to drugs of abuse. We have extended this notion by showing here that two additional and widely abused drugs, ethanol and Δ9-THC, also induce ΔFosB in these brain regions. We also identify several other areas of brain, implicated in cognitive function and stress responses, which show varying degrees of ΔFosB induction in response to chronic drug exposure. Some of these responses, like the induction of ΔFosB in striatal regions, are common across all drugs of abuse studied here, whereas responses in other brain areas are more drug-specific. These findings will now direct future investigations to characterize the role of ΔFosB induction in these other brain areas. They also help define the potential utility of antagonists of ΔFosB as a common treatment for drug addiction syndromes.

Fig. 3.

Induction of ΔFosB in the rat caudate putamen in a control rat (A) or after chronic treatment with ethanol (B), morphine (C), or cocaine (D). Levels of FosB-like immunoreactivity were analyzed by immunohistochemistry using a pan-FosB antibody. Labeling with the C-terminus antibody revealed no positive cells (not shown). Scale bar = 50 µm.

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

REFERENCES

- Alibhai IN, Green TA, Nestler EJ. Regulation of fosB and ΔfosB mRNA expression: In vivo and in vitro studies. Brain Res. 2007;11:4322–4333. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins JB, Atkins J, Carlezon WA, Chlan J, Nye HE, Nestler EJ. Region-specific induction of ΔFosB by repeated administration of typical versus atypical antipsychotic drugs. Synapse. 1999;33:118–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199908)33:2<118::AID-SYN2>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachtell RK, Wang YM, Freeman P, Risinger FO, Ryabinin AE. Alcohol drinking produces brain region-selective changes in expression of inducible transcription factors. Brain Res. 1999;847:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02019-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann AM, Matsumoto I, Wilce PA. AP-1 and Egr DNA-binding activities are increased in rat brain during ethanol withdrawal. J Neurochem. 1997;69:306–314. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69010306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carle TL, Alibhai IN, Wilkinson MB, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. Proteasome dependent and independent mechanisms for FosB destabilization: Identification of FosB degron domains and implications for ΔFosB stability. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:3009–3019. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JS, Nye HE, Kelz MB, Hiroi N, Nakabeppu Y, Hope BT, Nestler EJ. Regulation of ΔFosB and FosB-like proteins by electroconvulsive seizure (ECS) and cocaine treatments. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;48:880–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CR, Whisler K, Steffen C, Nestler EJ, Self DW. ΔFosB enhances incentive for cocaine. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2488–2493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02488.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criswell HE, Breese GR. Similar effects of ethanol and flumazenil on acquisition of a shuttle-box avoidance response during withdrawal from chronic ethanol treatment. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;110:753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13876.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich ME, Sommer J, Canas E, Unterwald EM. Periadolescent mice show enhanced ΔFosB upregulation in response to cocaine and amphetamine. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9155–9159. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09155.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye GD, Chapin RE, Vogel RA, Mailman RB, Kilts CD, Mueller RA, Breese GR. Effects of acute and chronic 1,3-butanediol treatment on central nervous system function: a comparison with ethanol. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;216:306–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graybiel AM, Moratalla R, Robertson HA. Amphetamine and cocaine induce drug-specific activation of the c-fos gene in strio-some-matrix compartments and limbic subdivisions of the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6912–6916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi N, Brown J, Haile C, Ye H, Greenberg ME, Nestler EJ. FosB mutant mice: Loss of chronic cocaine induction of Fos-related proteins and heightened sensitivity to cocaine’s psychomotor and rewarding effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:10397–10402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope BT, Kosofsky B, Hyman SE, Nestler EJ. Regulation of immediate early gene expression and AP-1 binding in the rat nucleus accumbens by chronic cocaine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:5764–5768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.13.5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope BT, Nye HE, Kelz MB, Self DW, Iadarola MJ, Nakabeppu Y, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. Induction of a long-lasting AP-1 complex composed of altered Fos-like proteins in brain by chronic cocaine and other chronic treatments. Neuron. 1994;13:1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelz MB, Chen JS, Carlezon WA, Whisler K, Gilden L, Beckmann AM, Steffen C, Zhang YJ, Marotti L, Self DW, Tkatch R, Baranauskas G, Surmeier DJ, Neve RL, Duman RS, Picciotto MR, Nestler EJ. Expression of the transcription factor ΔFosB in the brain controls sensitivity to cocaine. Nature. 1999;401:272–276. doi: 10.1038/45790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp DJ, Duncan GE, Crews FT, Breese GR. Induction of Fos-like proteins and ultrasonic vocalizations during ethanol withdrawal: further evidence for withdrawal-induced anxiety. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:481–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HF, Zhou WH, Zhu HQ, Lai MJ, Chen WS. Microinjection of M(5) muscarinic receptor antisense oligonucleotide into VTA inhibits FosB expression in the NAc and the hippocampus of heroin sensitized rats. Neurosci Bull. 2007;23:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12264-007-0001-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Nestler EJ. Regulation of gene expression and cocaine reward by CREB and ΔFosB. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1208–1215. doi: 10.1038/nn1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClung CA, Ulery PG, Perrotti LI, Zachariou V, Berton O, Nestler EJ. ΔFosB: A molecular switch for long-term adaptation in the brain. Mol Brain Res. 2004;132:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaid J, Dallimore JE, Mackie AR, Napier TC. Changes in accumbal and pallidal pCREB and ΔFosB in morphine-sensitized rats: Correlations with receptor-evoked electrophysiological measures in the ventral pallidum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006a;31:1212–1226. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaid J, Graham MP, Napier TC. Methamphetamine-induced sensitization differentially alters pCREB and Δ-FosB throughout the limbic circuit of the mammalian brain. Mol Pharmacol. 2006b;70:2064–2074. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moratalla R, Elibol R, Vallejo M, Graybiel AM. Network-level changes in expression of inducible Fos-Jun proteins in the striatum during chronic cocaine treatment and withdrawal. Neuron. 1996;17:147–156. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller DL, Unterwald EM. D1 dopamine receptors modulate ΔFosB induction in rat striatum after intermittent morphine administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;314:148–154. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.083410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Barrot M, Self DW. ΔFosB: A sustained molecular switch for addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11042–11046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191352698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye HE, Nestler EJ. Induction of chronic Fos-related antigens in rat brain by chronic morphine administration. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:636–645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye HE, Hope BT, Kelz MB, Iadarola M, Nestler EJ. Pharmacological studies of the regulation by cocaine of chronic Fra (Fos-related antigen) induction in the striatum and nucleus accumbens. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:1671–1680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Jentsch JD, Tronson N, Neve R, Nestler EJ, Taylor FR. ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens regulates food-reinforced instrumental behavior and motivation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9196–9204. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1124-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peakman MC, Colby C, Perrotti LI, Tekumalla P, Carle T, Ulery P, Chao J, Duman C, Steffen C, Monteggia L, Allen MR, Stock JL, Duman RS, McNeish JD, Barrot M, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Schaeffer E. Inducible, brain region-specific expression of a dominant negative mutant of c-Jun in transgenic mice decreases sensitivity to cocaine. Brain Res. 2003;970:73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Hadeishi Y, Barrot M, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. Induction of ΔFosB in reward-related brain structures after chronic stress. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10594–10602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2542-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Bolanos CA, Choi KH, Russo SJ, Edwards S, Ulery PG, Wallace D, Self DW, Nestler EJ, Barrot M. ΔFosB accumulates in a GABAergic cell population in the posterior tail of the ventral tegmental area after psychostimulant treatment. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2817–2824. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich EM, Pagliusi SR, Tessari M, Talabot-Ayer D, Hooft van Huijsduijnen R, Chiamulera C. Common neural substrates for the addictive properties of nicotine and cocaine. Science. 1997;275:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. O. o. A. Studies, National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information. Rockville, MD: NSDUH Series H-28; 2005. Results from the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. [Google Scholar]

- Sim-Selley LJ, Martin BR. Effect of chronic administration of R-(+)-[2,3-dihydro-5-methyl-3-[(morpholinyl)methyl]pyrrolo[1,2, 3-de]-1,4-b enzoxazinyl]-(1-naphthalenyl)methanone mesylate (WIN55,212-2) or delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol on cannabinoid receptor adaptation in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303:36–44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.035618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton MA, Karanian DA, Self DW. Factors that determine a propensity for cocaine-seeking behavior during abstinence in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:626–641. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulery PG, Rudenko G, Nestler EJ. Regulation of ΔFosB stability by phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5131–5142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Involvement of the dorsal striatum in cue-controlled cocaine seeking. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8665–8670. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0925-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werme M, Messer C, Olson L, Gilden L, Thorén P, Nestler EJ, Brené S. ΔFosB regulates wheel running. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8133–8138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-08133.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstanley CA, LaPlant Q, Theobald DEH, Green TA, Bachtell RK, Perrotti LI, DiLeone FJ, Russo SJ, Garth WJ, Self DW, Nestler EJ. ΔFosB induction in orbitofrontal cortex mediates tolerance to cocaine-induced cognitive dysfunction. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10497–10507. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2566-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ST, Porrino LJ, Iadarola MJ. Cocaine induces striatal c-fos-immunoreactive proteins via dopaminergic D1 receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1291–1295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou V, Bolanos CA, Selley DE, Theobald D, Cassidy MP, Kelz MB, Shaw-Lutchman T, Berton O, Sim-Selley LJ, DiLeone RJ, Kumar A, Nestler EJ. ΔFosB: An essential role for ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens in morphine action. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:205–211. doi: 10.1038/nn1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]