Abstract

Researchers have documented health disparities for African American and other youth of color in the area of mental health. In accordance with calls for the development of innovative methods for use in reducing these disparities, the purpose of this article is to describe the development of an evidence-based intervention targeting the use of psychiatric clinical care by African American families. The authors summarize current research in the areas of perceived and demonstrated bias in the provision of mental health services, the significance of the problem of low African American participation in psychiatric clinical research and care, and evidence-based approaches to conducting family-oriented research to address adolescent mental illness in this population. This discussion is followed by a description of the development of an intervention to improve familial treatment engagement and plans to test the intervention. The article is provided as a foundation for carefully defined plans to address the unmet mental health needs of depressed African American adolescents within a culturally relevant familial context.

Keywords: Racial Health Disparities, Culturally Relevant Intervention, Intervention Development, Empirically Supported Treatment, African American Youth, Psychiatric Clinical Care, Blocks, Adolescent Depression, Sociocultural Factors, Adolescent Psychiatry, Major Depression, Health & Mental Health Services

Recent research suggests that African American and other adolescents of color face grave disparities compared with their White counterparts in the burden experienced by mental illness and in the appropriateness of indicated behavioral and pharmacological treatments for psychiatric illnesses (Breland-Noble, 2004; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Specifically, recent research indicates that African American youth with mental health and behavioral problems in the foster care system, and therapeutic foster care specifically, have a greater likelihood of involvement with the juvenile justice sector and in-home counseling and crisis services. Further, recent research suggests that African American youth are significantly less likely than their White peers to receive psychotropic medications for their illnesses. The former finding reflects the disparities literature indicating that African American youth with externalizing problems receive punitive services while White youth with similar problems receive psychiatric treatment (Westendorp, Brink, Roberson, & Ortiz, 1986). The latter finding echoes published prescription patterns for African American youth (Zito, Safer, dosReis, Magder, & Riddle, 1997).

These disparities are compounded by data supporting former Surgeon General David Satcher’s suggestion that even though significant numbers of youth suffer from mental disorders, few receive mental health services. For example, using a racially diverse (African American, White, and Native American/American Indian) sample of 920 children aged 9–17, and parent-guardian pairs, Adrian Angold and colleagues (2002) found that although 21% of the families interviewed had a child with a diagnosable psychiatric illness, only 13%, including 36% of those who had actually been diagnosed, had sought clinical care in the prior 3-month period. Yeh and colleagues (2002) found similar results in their study of 3,962 youth in the San Diego, California, area, which included an even more racially diverse sample of youth. Ultimately, as reported by Satcher, the vast majority of youth with psychiatric illnesses do not receive the mental health care they need, and youth of color face alarmingly high rates of unmet need. Given the high percentage of unmet need for psychiatric illness, it is imperative that mental health researchers continue to move in the direction of identifying barriers to treatment and recognition across populations and service entities (Kazdin, Holland, & Crowley, 1997). Satcher and others concurred with this assessment and have issued a call for new and innovative approaches to addressing these disparities.

We present a rationale for and description of a new evidence-based intervention for reducing health disparities in African American adolescent participation in psychiatric clinical research and care through use of a family-based framework. Our discussion begins with an overview of the nature and significance of the problem of low African American participation in psychiatric clinical research and care. This is followed by a description of the theoretical constructs supporting the intervention, and we conclude with a detailed description of plans to test the model.

AFRICAN AMERICANS, PSYCHIATRIC CLINICAL CARE, AND RESEARCH

Mental health services researchers report that on average, African American families across socioeconomic strata make less use of traditional mental health services (i.e., specialty mental health and inpatient services) than White families (Angold et al., 2002; Song, Sands, & Wong, 2004). Various reasons have been posited for these differences, with the most popular (i.e., frequent) published rationale being differences in insurance status (Snowden & Thomas, 2000; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Scholars of color, however, have evaluated the insurance status rationale and reported that insurance status alone fails to account for differences in use patterns between African Americans and White Americans (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). They suggested instead that issues like bias are a more scientifically viable explanation (Snowden, 2003). As such issues of bias relate to African American youth, note the previously mentioned findings in which researchers suggested that African American youth are disproportionately treated via punitive services, usually in the juvenile justice sector, for the same types of behavioral problems for which White American youth receive mental health specialty treatment (Breland-Noble, 2004; Westendorp et al., 1986).

In general, research seems to support the notion that African Americans as a group make less use of psychiatric clinical care than do White Americans. We believe that the primary factors contributing to use patterns include historical barriers, provider-level barriers, and individual barriers (see Breland-Noble, 2004, for a comprehensive review). Historical factors include a culturally embedded mistrust of the medical profession in general, and the mental health profession specifically, both of which employ limited numbers of African Americans (Jones, Brown, Davis, Jeffries, & Shenoy, 1998; Maultsby, 1982). In addition, significant numbers of African Americans cite the Tuskegee syphilis experiment as a cause of mistrust for the medical community (Shavers, Lynch, & Burmeister, 2000). The effect of that experiment appears to be widely recognized by Black Americans (a term encompassing African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and immigrant Africans), such that even though it ended approximately 30 years ago, many Black Americans remain aware of and are influenced by the experiment (Shavers, Lynch, & Burmeister, 2001).

Provider-level barriers include concepts like diagnosis bias and treatment bias. The “Unequal Treatment” report of 2002 (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2002) documents these two biases in detail. In general, the report suggests that “culture counts” and that it does so by creating a cultural collision between the culture of the mental health profession and that of African American patients. The end result is that “the culture of the clinician and the larger healthcare system govern the societal response to a patient with a mental illness” (Smedley et al., p. 216). As an example, note Snowden’s well-documented work on the disparities between White Americans and African Americans in the diagnosis of schizophrenia and affective disorders. Essentially, Snowden demonstrated that African Americans with symptoms similar to those of White Americans were 1.8 times more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia and about half as likely to be diagnosed with an affective disorder (Snowden, 2001, 2003).

Individual barriers are the constellation of cultural factors within the African American community that contribute to negative perceptions of the medical and mental health professions. Primary among these factors is the importance of the Black faith community, a construct called John Henryism, and African American perceptions of psychiatric illness and stigma. Regarding perceptions of psychiatric illness, it is safe to say that many African Americans view it as a proscribed subject, with fewer African Americans than White Americans believing in genetic and dysfunctional familial precursors to psychiatric illness. Instead, many African Americans and other people of color attribute emotional and behavioral disturbance to nonpsychiatric factors (e.g., mystical beliefs and spiritual weakness; Cauce et al., 2002; Schnittker, Freese, & Powell, 2000) and choose to employ active coping strategies to address these disturbances. Evidence of such perceptions has been reported in the literature and is evident in popular culture via ethnicity-specific books like 72 Hour Hold (Campbell, 2005) and Lay My Burden Down (Poussaint & Alexander, 2000).

John Henryism, the Faith Community, and Stigma

John Henryism is a construct developed by Sherman James and derived from the African American legend of a steel driver who defeated a mechanical steel drill in a contest and died soon after from exhaustion. The concept of John Henryism, then, is a synonym for protracted physical and psychological effort to overcome obstacles, sometimes to the point of personal detriment (Bonham, Seller, & Neighbors, 2004; Sherman James, personal communication, July 8, 2005). The construct represents an African American active coping style in response to severe life stressors, which we believe is a contributing factor to limited use of clinical care for psychiatric illness. A strong body of literature on John Henryism points to the idea that the increased risk for hypertension exhibited among segments of the African American population (i.e., poor and working-class individuals) might be attributable to protracted striving against obstacles. Given this idea and its established relationship to perceived discrimination, cardiovascular disease, and stress, it seems reasonable to assume that employment of the John Henryism coping style might prevent African Americans from viewing psychiatric illnesses as necessitating treatment. As such, internalizing psychiatric disorders are to be coped with by working harder to overcome stress and sadness instead of consulting a psychiatrist or psychologist for medication or talk therapy.

The faith community

Investigators have provided solid evidence describing the relationship between the African American faith community and limited use of clinical care for psychiatric illness. In general, this literature suggests that African Americans initially consult a member of the religious community for guidance and interventions regarding behavioral and emotional problems (Blank, Mahmood, Fox, & Guterbock, 2002; Neighbors, 2000). Often, such consultation is employed in the place of other forms of mental health services, if these types of services are even considered at all. In essence, it is likely that given the present state of our mental health system—few service providers of color, limited evidence base for treatments with African Americans, and well-documented disparities in treatment—African Americans are wisely electing to pursue other means of meeting their families’ mental health needs. The utility of the church and clergy as a means of support for African American families dealing with adolescent behavioral and emotional problems is an emerging area of study incorporated into our intervention.

Stigma

With reference to the use of psychiatric clinical care by African American families for youth specifically, investigators suggest that parents are fearful of stigmatization and associated negative consequences for their children. These fears are often rooted in the reality of differential treatment for African American and White American youth with emotional and behavioral problems. African American parents have reported being fearful of their children being mislabeled, mistreated, and possibly taken away from them (McMiller & Weisz, 1996; Pastore, Juszczak, Fisher, & Friedman, 1998; Wu et al., 2001). To support this claim, note the work of McMiller and Weisz, who asked parents from African American, Latino, and White American families about their paths of entry into traditional mental health clinical care. The African American and Latino families responded by saying that they initially sought help from professionals and agencies much less frequently than their White American peers. In fact, African American and Latino families were 0.37 times as likely than White American families to seek initial help from a professional or agency (McMiller & Weisz). When coupled with the reality of demonstrated clinician diagnosis bias, which often corresponds to more punitive forms of treatment, it is not surprising that African Americans may be less likely than their White American counterparts to view traditional forms of mental health treatment as viable options for themselves or their families. With regard to depressive disorders specifically, almost no research exists that specifically addresses the relationship between depressive disorders in African American youth and clinical care of the youth and their families. Findings do, however, indicate that parental symptom recognition and perceptions of level of impairment are strong precursors of treatment-seeking behaviors. Therefore, it seems that an investigation is warranted that synthesizes understanding African American parents’ real concerns about stigmatization of their children, disorder identification, and clinical care for depressed African American adolescents within a familial context.

Psychosocial Barriers to Participation in Psychiatric Clinical Research

Though we have seen a proliferation of literature in recent years that points to the access-to-care barriers faced by African Americans regarding clinical care (with equivocal results), very little is known about African Americans’ perceptions of participation in clinical research. Of the information available, one event is salient and continues to affect African American willingness to participate in clinical research: the Tuskegee syphilis experiment. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment took place between 1932 and 1972 and followed 399 mostly impoverished African American sharecroppers in Macon County, Alabama. The men were denied treatment for syphilis and instead were told by physicians of the United States Public Health Service that they were being treated for “bad blood” (Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee, 1996). The study is cited as one of the longest nontherapeutic experiments on human beings in medical history (Heller, 1972). The effects of this study on African American trust in medical research have been well documented in recent years and provide strong empirical support for the lack of African American participation in medical research.

In 2000, Shavers and colleagues surveyed White Americans and a socioeconomically diverse group of African Americans (n=179) in the Detroit metropolitan area. They found that 81% of African Americans in the group had knowledge of the Tuskegee study. Further, they determined that knowledge of the Tuskegee study had a direct impact on the amount of trust placed in medical researchers as indicated by 51% of the African American participants in the study. Forty-six percent of African Americans reported that their knowledge of the study would affect future research participation decisions, and of that group, almost half (49%) stated that they would not be willing to participate in future medical research studies. These types of findings have been replicated by other scholars and point to the profound impact of the Tuskegee experiments on African Americans as a whole (Corbie-Smith, Thomas, Williams, & Moody-Ayers, 1999; Freimuth et al., 2001).

Other literature points to a variety of commonly held beliefs among African Americans and other Blacks regarding lack of participation in medical research. Some of the cited factors include lack of African American professionals in leadership roles in medical studies (Shavers et al., 2001); questions regarding the motives of non-African American clinicians and researchers (Mouton, Harris, Rovi, Solorzano, & Johnson, 1997); fears of exploitation (Connell, Shaw, Holmes, & Foster, 2001; Corbie-Smith et al., 1999); and lack of knowledge about the process of medical research engagement (Corbie-Smith et al., 1999). Though data exist on the psychosocial barriers to participation in clinical research for African American adults, no published literature currently exists regarding African American adolescent psychosocial barriers to participation in clinical research. Because parents are often the gatekeepers of adolescent participation in research, it is natural to assume that they alone proffer permission for youth participation. Unfortunately, no research exists (of which we are aware) that specifically delineates African American adolescents’ role in proffering their own permission for research participation.

Overall, the literature outlines a number of reasons for African American under-representation and associated disparities in mental health clinical care and research. In response, former surgeon general David Satcher has called for research to contribute to the broad priority of reducing health disparities in mental health care for diverse youth (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). As such, the need for new approaches to meet the needs of youth of color with mental illness seems clear.

During his tenure as surgeon general, Satcher cited adolescent depression as an illness of import. His report Mental Health: Culture, Race and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health identified a limited research base for children of color and detailed the great risks associated with depressive disorders for African American youth. Other research supports these findings and suggests that depression in youth is associated with increased risk of suicidal behaviors (National Institute of Mental Health, 2003). Between 1980 and 1995, the suicide rate for African American youth (ages 10–19) increased from 2.1 to 4.5 per 100,000, or 114% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998). These ideas suggest the importance of improving strategies for including African American adolescents and families in prevention and intervention studies and in obtaining clinical care. In addition, because of the morbidity and functional impairment associated with adolescent depression, including increased risk of social/interpersonal and academic/cognitive impairment (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Kovacs, Goldston, & Gatsonis, 1993), it follows that improvements in the engagement and treatment of depressed youth constitute an important public health contribution.

CURRENT INTERVENTIONS TOREDUCE BARRIERS TO CLINICAL CARE AND RESEARCH

There is an emerging body of literature regarding interventions to reduce barriers to psychiatric clinical care via school based mechanisms. In a recently published systematic review of this literature, investigators described a body of programs, including a number of promising programs that address the diagnosis and treatment of childhood psychiatric illness. The review identifies key factors related to the successful implementation and maintenance of these programs, primary among which is the inclusion of teachers, parents, and peers (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000). Unfortunately, little mention is made of the racial diversity of the youth included in the samples of the studies reviewed, so although all indications point to the utility of family-based interventions, how such interventions might work across racial groups remains unclear.

Including Family in Culturally Relevant Interventions for African Americans

That the family is the centerpiece helping individuals to establish individual high functioning and emotional well-being is a point of artifact for scholars interested in families of color (McAdoo, 1997; McGoldrick, Giordano, & Pearce, 1996). This is particularly true for African Americans, for whom the family serves as the focal point for multiple aspects of individual physical and emotional development. Of particular recent interest to investigators is the African American family’s role in multiple areas of mental health, including racial socialization, stress coping, educational self-efficacy, self-esteem, and sexual behaviors (Brody et al., 2004; Comer & Woodruff, 1998; Scott, 2004; Stevenson, Reed, Bodison, & Bishop, 1997). These investigators have provided a sound theoretical framework for, and built rigorous studies (including randomized controlled trials) upon, the idea of the importance of the African American family in ameliorating childhood problems and concerns.

The significance of family-based interventions for the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illness, especially with families of color, is also indicated in contemporary research conducted with African Americans in the Chicago area. The Chicago African American Youth Health Behavior Project Youth Project (ABAN AYA) was a randomized controlled trial conducted in 12 Chicago area schools and the communities that encompass the schools. The program consisted of two experimental conditions, both of which included a classroom-based curriculum, with one enhanced by a community intervention component and a control condition. Families were an integral part of the treatment and were included in all aspects of the intervention (i.e., parents were encouraged to review session materials and themes with their children at home). The investigators were keenly aware of the literature focused on treating psychiatric illness and behavioral concerns in African American youth, which indicates the necessity of strengthening family and community ties to ensure the youth’s success (Flay, Graumlich, Segawa, Burns, & Holliday, 2004; Hilliard, 1988). Results of the study specify that theoretically driven and culturally relevant interventions significantly improved a variety of target behaviors for African American males, with the classroom based, family-inclusive intervention generating statistically significant gains over the classroom-only curriculum.

The aforementioned findings regarding African American youth, families, and psychiatric clinical care and research raise a number of concerns, including the impact of a limited evidence base for treating psychiatric illness in youth and perceptions of psychiatric clinical research. In addition, although a growing body of literature exists to address African American participation in psychiatric clinical care, very little specifically addresses the role of the family in engaging African American youth in either clinical care or research participation.

PsychiatricTreatment Engagement: A New Intervention

We developed this psychiatric treatment engagement intervention specifically for depressed African American adolescents and their families. However, we believe that the utility of the model can be extended to other racial groups and psychiatric illnesses. Stated succinctly, the theory on which the intervention is based builds on the varied relationships that contribute to the identification of, and help-seeking behaviors for, depressed African American adolescents within the context of families. Specifically, the foundation for the intervention comes from four theoretical constructs and practices: (1) the transtheoretical model of change, (2) motivational interviewing, (2) the theory of triadic influence, and (4) the seven field principles.

The transtheoretical model of change and motivational interviewing

The transtheoretical model of change (TMOC) by Prochaska and DiClemente is a behavioral stage change model that consists of five stages: (1) precontemplation: unwillingness to change a problematic behavior; (2) contemplation: consideration of changing behavior; (3) preparation: articulating a proximal change; (4) action: engaging in behavior change; and (5) maintenance: continual monitoring of behavior change activities to avoid relapse (Johnson et al., 1998; Voorhees et al., 1996; Walcott-McQuigg & Prohaska, 2001). Success in increasing health promoting behaviors is greatest when interventions are tailored to an individual’s stage of change. The stages of change have been applied to African American and other youth to address prevention in teen pregnancy and obesity (Felton, Ott, & Jeter, 2000; Prochaska et al., 1992; Velicer & Prochaska, 1999; Voorhees et al.).

Motivational interviewing (MI) can be considered an applied version of the TMOC. The four key principles of MI are to (1) express empathy, (2) develop discrepancy, (3) roll with resistance, and (4) support self-efficacy (Martino & Hopfer, 2003). MI has proved to be efficacious with adults and youth of diverse backgrounds and for multiple disorders and behaviors (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003; Channon, Smith, & Gregory, 2003; Greenstein, Franklin, & McGuffin, 1999; Polcin, Galloway, Palmer, & Mains, 2004; Quick, 2003). MI has been used with African Americans, specifically in adult diabetes management, smoking cessation, and youth nutrition enhancement. MI is rooted in long-term psychotherapeutic interventions but has been modified for use in short-term modalities like clinical settings with non-help-seeking patients (Rollnick, Heather, & Bell, 1992). The brief approach concedes that most patients do not come to providers with a preestablished willingness to change their health behaviors. Therefore, clinician advice giving is not always welcome and can be detrimental to the clinician-patient relationship. By accounting for these ideas, the brief MI approach is an ideal framework in which to engage patients in considering health promoting behaviors, including using clinical care.

The theory of triadic influence and the seven field principles

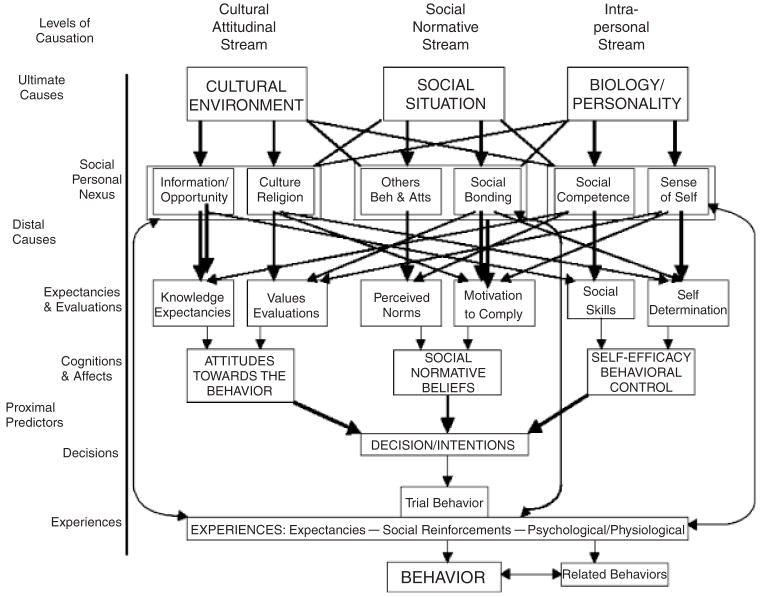

The theory of triadic influence (TTI; Figure 1) is a model of behavior change developed by Flay and Petraitis (1994). The model has five tiers of behavior causes, ranging from proximal to distal to ultimate, and three streams, including six substreams, of influence that flow through the seven tiers (Bell, Flay, & Paikoff, 2002; Flay & Petraitis). TTI provides an integration of multiple sociological and psychological theories of behavior and behavior change. Because the model is too complex for practical application, Carl Bell and colleagues have developed the seven field principles (Table 1) as an operationalized version of TTI. They believe that these principles are necessary for any successful universal health behavior intervention, particularly one focused on African Americans (Bell & McKay, 2004). In conjunction with Brian Flay and other colleagues, Bell demonstrated the utility of the seven field principles via the Chicago ABAN AYA. The project used a large (N=1153) randomized controlled trial of two behavioral interventions for low-income African American adolescents. The main outcome measures were violence, provocative behavior, school delinquency, substance use, and sexual behaviors (i.e., intercourse and condom use). Findings indicated that the field principle approach yielded positive outcomes for boys greater than those of the control and alternate behavioral model groups.

Figure 1.

Model of Theory of Triadic influence

Table 1.

Seven Field Principles

| Field Principle | Method of Actualization |

|---|---|

| Rebuilding the village | Build community collaborations to support troubled families |

| Providing access to health care | Transport evidence-based assessment and treatment to the community |

| Increasing connectedness | Create systems to connect troubled African American families and community support systems |

| Increasing social skills | Organizational/staff development |

| Increasing self-esteem | Attach stakeholders to positive, proactive community and organizational systems to create a sense of power, a sense of models, and a sense of uniqueness |

| Reestablishing the adult protective shield | Actualize quality assurance systems to monitor practices |

| Minimizing trauma | Take a systems approach to problems and ensure support for each stakeholder |

Adapted from C. Bell, personal communication June 16, 2005; used with permission.

TMOC, TTI, and improving African American treatment engagement

Fundamentally, TMOC and TTI are intentional change models; they are based on the idea that individuals decide to change their behaviors. Both models recognize that individuals are integrated into and influenced by the systems with which they interact daily, but TTI suggests that one cannot separate the individual from culture and society and emphasizes the role of society in an individual’s decision to change. MI, based on TMOC, and the seven field principles, based on TTI, each provide a mechanism of organizing and orchestrating behavior change. In the context of the proposed intervention, MI provides the tools for use in encouraging behavior change. For example, Miller and Rollnick stated that motivation to change is elicited from the patient and not imposed by the clinician. In this manner, MI reflects the tenet of TMOC, which states that change is intentional on the part of the patient. Similarly, the seven field principles provide culturally specific approaches to encouraging behavior change. For example, in using family-bonding activities in the context of a treatment session, a clinician can positively affect the social normative beliefs of the family and encourage individual behavior change in a safe setting. Stated succinctly, the theories and their mechanisms of action represent an ideal framework for developing a treatment to improve psychiatric treatment engagement among African Americans. The seven field principles in particular are useful for African Americans who culturally value family (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001) and for whom parents serve as the gatekeepers for adolescent mental health treatment engagement (McMiller & Weisz, 1996).

The Breland-Noble Motivational Interviewing (BNMI) Intervention Overview and Session Content

The Breland-Noble motivational interviewing intervention (BNMI) focuses on increasing readiness for psychiatric treatment engagement. The entire intervention can be completed in 3 weeks, during which patients complete a 20-minute phone segment and two treatment sessions lasting 75–90minutes each. We present a description of each session.

BNMI phone segment (20minutes)

A major focus of the phone segment is reducing barriers to engagement using MI and the seven field principles. The specific field principles used are “rebuilding the village” by fostering collaborations to support families; “providing access to health care” by transporting evidence-based approaches to the community; and “reestablishing the adult protective shield” by monitoring interactions with parents regarding their children’s well-being. The structure of the phone segment is akin to that of Mary McKay’s model (McKay, Stoewe, McCadam, & Gonzales, 1998). The topics of discussion in the phone segment include clarification of the youth’s need for psychiatric care for his or her depression; increasing the adolescent’s and families’ investment in treatment-engagement behaviors; identifying past experiences with mental health professionals; and, for poorly resourced families, strategizing to overcome any physical barriers to services (i.e., money, transportation). The segment concludes with scheduling for the first in-person appointment. A reminder packet is sent within 24 hours of the phone segment and includes a thank you card, an appointment reminder, and a brief description of the intervention. Families also receive a reminder call the day before the first in-person session.

In-person session 1 (70–80minutes) and session 2 (80–90 minutes)

A central goal of the in-person sessions is reduction of perceptual barriers to engagement using family intervention and MI methods. During these sessions, clinicians spend 40–50 minutes with the depressed adolescent patient to help the adolescent increase awareness of his or her depression, explore personal feelings about the depression, explore whether he or she would like to feel better, and examine the pros and cons of participating in treatment for the depression. The session begins with the administration of a brief stages-of-change measure to provide the clinician with a sense of where the patient falls on the model-of-change continuum. Subsequently, the clinician works collaboratively with the adolescent patient to consider alternatives to problems that emerge. For example, the patient and clinician might engage in an in-depth discussion of the adolescent’s main concern in not seeking treatment and the level of commitment to follow through with treatment, and review the results from a brief stages-of-change measure administered at the beginning of the first in-person session. Clinicians might also assign homework to reinforce principles.

Subsequent to the clinician-adolescent session, parents work in collaboration with clinicians in 30–40-minute sessions to gain a better understanding of the definition and course of the depression and the role of mental health professionals, resolve past negative experiences with mental health systems and professionals, and develop skills for use in encouraging treatment engagement for their adolescents. In accordance with the field principles, “increasing social skills” and “increasing self-esteem,” parents are encouraged to focus on the adolescent’s strengths and to avoid statements that indicate a lack of faith in the adolescent’s ability to cope. Parents are also asked to realize that treatment-engagement readiness takes time and is a process. Sample projects include bonding, attachment, and connectedness activities to engage parents in discussions with the adolescent on strengthening ties with family and ethnic heritage. Finally, clinicians set the appointment for session 2.

Session 2 consists of a 30-minute adolescent patient session, a 30-minute parent/guardian session, and a 30-minute joint session. The adolescent session begins with the administration of the same stages-of-change assessment previously administered to track any movement in the stage of change. Any homework from session 1 is reviewed and discussed for patient feedback on the utility (or lack thereof). Clinicians acknowledge and reinforce positive outcomes and strategize with patients on the remediation of less helpful, negative outcomes. Clinicians also attempt to elicit self-motivational statements to help patients use change talk via a discussion on problem recognition (How has not going to therapy been a problem for you?), concern (How much does not going to therapy concern you?), intent to change (What is happening in your life to make you think change is important now?), and optimism (How likely are you to engage in therapy at this point?).

The parent/guardian session includes a discussion of their and the adolescent’s readiness to engage in treatment. They hold discussions necessary to roll with parental resistance to treatment engagement. Clinicians encourage parents to pay positive attention to any of the adolescents’ efforts to engage in treatment (e.g., looking for names of therapists on the Internet, asking about what is involved in therapy). Clinicians also continue to use motivational approaches to address ambivalence in the session and readiness to change. For example, clinicians might survey parents to monitor expectations in treatment and to assess whether needs are perceived as being addressed. Parents are also encouraged to take a collaborative problem-solving approach with adolescent patients regarding any treatment interfering behaviors (e.g., refusing homework).

In the joint meeting, the clinician, parents/guardians, and adolescent patient discuss continued progress toward getting treatment for the depression, the translation of any homework into practice, plans for dealing with clinician advice, and any suggestions that the family may have regarding improving the intervention.

Exit interviews

During exit interviews, clinicians administer a consumer satisfaction survey and ask patients and their families about their experiences with and perceptions of the intervention. This includes ratings of perceived benefit and comfort with the program, whether the program would be recommended to others with similar problems, the credibility of the rationale, and similar areas. Clinicians also attempt to obtain information from treatment dropouts regarding their reasons for dropping out. This information will be used in revising the intervention as needed. In this manner, clinicians can use additional consumer input to aid in assessing treatment credibility.

Testing the Intervention

To gather data regarding the efficacy of this intervention, we have developed a systematic means for refining and testing it via a pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Intervention refinement

Though we have provided a framework for the intervention, we have also structured a means of refining the intervention based on the importance of community-based participation in conducting research with African Americans and in accordance with established research in the area of intervention development (Ammerman et al., 2003; Rounsaville, Carroll, & Onken, 2001). As a guiding body for the research, we have incorporated an advisory board structure into the research agenda. We will enlist African American clergy, school personnel, health care providers, community leaders, and community members to support a community-focused direction for our work. The board will meet quarterly to provide feedback regarding the overall research agenda, the historical relationships between area medical researchers and the African American community, a framework for social and structural issues at the interface of the medical and African American communities, and study results. By operating in this manner, we seek to offer redress for the historical exclusion of African Americans as research partners.

The first stage in refining the proposed intervention is the conduct of focus groups to solicit an in-depth understanding of African Americans’ cultural perceptions of barriers to engagement in psychiatric clinical treatment and research. We have decided to employ a qualitative focus group approach to maximize our ability to generate hypotheses in this poorly understood area. As such, we expect to generate a number of systematically derived expected themes that will differ for the adults and youth. The expected themes reflect those previously mentioned, including the lack of African American leadership in clinical research focused on African Americans and the Tuskegee syphilis study. We hope to enroll 80 participants in the focus groups and will split the focus groups into adult-only and youth-only groups. The purpose of the age specificity is to encourage openness by participants. We have planned to conduct the focus groups in local churches and community centers in accordance with best practices for community-based participatory research (CBPR). The hope is to generate community support for the research by enlisting community members as full partners. At the conclusion of the focus groups, we will analyze all data and incorporate it into the development of the BNMI. Additionally, we have planned to collaboratively disseminate findings in print and via presentations, with advisory board and community collaborators as coauthors.

The focus group data and the seven field principles model will inform development of and modifications to the BNMI and will be subject to further modifications based on our experiences in piloting the intervention, feedback from expert collaborators, and exit interviews with treated patients and families. We will develop a manual for this intervention that will provide guidelines for the implementation of the intervention but will also allow clinicians to tailor the intervention to individual patients as a means of ensuring cultural sensitivity.

Overview of the research plan

We will recruit 40 participants who meet a predetermined set of inclusion criteria (e.g. primary diagnosis of depression, between the ages of 11 and 17, African American, and so on) and assign them to the (experimental) BNMI condition or a wait list control (to account for an expected 20% attrition). Any participants recruited for the study exhibiting high readiness for treatment engagement will go directly into treatment for their depression with clinical staff at one of a predetermined set of locations with culturally competent staff. At the conclusion of the four-session intervention (including the aforementioned three sessions and an inclusion criteria phone screen), those participants exhibiting high readiness on a stages-of-change measure will go on to individual treatment at one of a predetermined set of locations with culturally competent staff.

A control group is included in the research protocol as a measure of the efficacy of the BNMI intervention. Specifically, a wait list control is the group of comparison. The individuals in this arm of the trial must exhibit low readiness for treatment (as measured by the stages-of-change measure) so as to be comparable with the experimental group. These individuals will go directly into clinical treatment, in contrast to the experimental participants, who get the BNMI intervention prior to their depression treatment. By including the wait-list control group, the investigators will have the ability to judge whether attrition from treatment is lower in the new intervention relative to not having the intervention, and whether the new intervention yields more on my primary efficacy measure (i.e., whether the experimental group experiences greater reduction in resistance to change as measured by the stages-of-change measure, as compared with wait-list-controlled participants). Finally, participants will be randomized in groups of 4 to ensure a rough balance in patient flow between conditions. That is, for every 4 participants, 2 will be randomly assigned to the experimental BNMI group, and 2 will be assigned to the wait-list control group.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The primary goal for the development of the Breland-Noble motivational interviewing intervention is to devise a means of better understanding and positively influencing psychiatric treatment engagement by depressed African American adolescents and their families. The main purpose of the associated study is to examine the feasibility of procedures and a treatment manual for potential use in a larger study and to determine estimates of the effects of the intervention over time and the variability of response that can be expected from the intervention. It is hoped that such data will be useful in computing estimates of the needed sample size for a larger efficacy study.

Various methods have been incorporated into the intervention itself and the test of the intervention to address cultural relevance for African American adolescents and families. Specifically, the intervention was designed using theories (i.e., the transtheoretical model of change and the theory of triadic influence) with particular relevance for African Americans, and it incorporates behavioral intervention approaches that also have demonstrated efficacy, utility, and adaptability to African American adolescents and families (i.e., motivational interviewing and the seven field principles). By attending to the aspects of culture deemed important by African Americans—namely, striving over obstacles, identifying and attending to individual and family perspectives on their own needs, and using a brief approach—the intervention seeks to directly address some of the individual and systemic barriers that African Americans face regarding psychiatric treatment engagement. For example, one of the barriers described in an earlier section of this manuscript identified the legitimate concerns of African American parents regarding the mislabeling (i.e., stigmatization) of their children. The proposed intervention seeks to circumvent such apprehensions by directly involving the parents in the treatment at the outset. In other words, parents are provided with an opportunity to collaborate with the clinician as treatment is recommended and initiated, instead of being told at some point after the child has experienced a negative consequence from his or her untreated or misdiagnosed depression.

Additionally, the intervention design incorporates aspects of community-based participatory research specifically to address some of the historical problems associated with African American under-representation in clinical research. Examples of these efforts include the incorporation of an advisory board and plans to hold focus group meetings in local communities.

Overall, it is hoped that the intervention to be implemented and tested can serve as a culturally relevant treatment guide for clinicians working with African American families of depressed adolescents and the adolescents themselves.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIMH Grants No. T32 65742 and No. P30 MH66386.

References

- Ammerman A, Corbie-Smith G, St George DM, Washington C, Weathers B, Jackson- Christian B. Research expectations among African American church leaders in the praise! Project: A randomized trial guided by community-based participatory research. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:1720–1727. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Erkanli A, Farmer EM, Fairbank JA, Burns BJ, Keeler G, et al. Psychiatric disorder, impairment, and service use in rural African American and White youth. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:893–901. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C, Flay B, Paikoff R. Strategies for health behavioral change. In: Chunn J, editor. The health behavioral change imperative: Theory, education, and practice in diverse populations. New York: Kluwer Academic; 2002. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- Bell C, McKay M. Constructing a children’s mental health infrastructure using community psychiatry principles. Journal of Legal Medicine. 2004;25:5–22. doi: 10.1080/01947640490361808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blank MB, Mahmood M, Fox JC, Guterbock T. Alternative mental health services: The role of the Black church in the South. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1668–1672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonham VL, Sellers SL, Neighbors HW. John Henryism and self-reported physical health among high-socioeconomic status African American men. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:737–738. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breland-Noble AM. Mental healthcare disparities affect treatment of Black adolescents. Psychiatric Annals. 2004;34:534–541. doi: 10.3928/0048-5713-20040701-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair L, et al. The strong African American families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell BM. 72 hour hold. New York: Knopf; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M, Paradise M, Cochran BN, Shea JM, Srebnik D, et al. Cultural and contextual influences in mental health help seeking: A focus on ethnic minority youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:44–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide among Black youths: United States, 1980–1995. 1998 March 20; Retrieved February 11, 2003, from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00051591.htm. [PubMed]

- Channon S, Smith VJ, Gregory JW. A pilot study of motivational interviewing in adolescents with diabetes. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2003;88:680–683. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.8.680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer JP, Woodruff DW. Mental health in schools. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 1998;7:499–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Shaw BA, Holmes SB, Foster NL. Caregivers’ attitudes toward their family members’ participation in Alzheimer disease research: Implications for recruitment and retention. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2001;15:137–145. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. Journal of General Internal Medicine September. 1999;14:537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton GM, Ott A, Jeter C. Physical activity stages of change in African American women: Implications for nurse practitioners. Nurse Practitioner Forum. 2000;11:116–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Graumlich S, Segawa E, Burns JL, Holliday MY. Effects of 2 prevention programs on high-risk behaviors among African American youth: A randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:377–384. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.4.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence: A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. In: Albrecht GS, editor. Advances in medical sociology, Vol. IV: A reconsideration of models of health behavior change. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1994. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Freimuth VS, Quinn SC, Thomas SB, Cole G, Zook E, Duncan T. African Americans’ views on research and the Tuskegee syphilis study. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;52:797–808. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00178-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein DK, Franklin ME, McGuffin P. Measuring motivation to change: An examination of the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment questionnaire (URICA) in an adolescent sample. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1999;36:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Heller J. The New York Times. 1972. July 25, Syphilis, victims in U.S. study went untreated for 40 years: Syphilis victims got no therapy; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard AG. Reintegration for education: Black community involvement with Black students in schools. Urban League Review. 1988;11(12):201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P, Johnson J, Heurich S, Curl C, Carson A, Hill S, et al. The Africentric transtheoretical model in a school-based pregnancy prevention program. Association of Black Nursing Faculty Journal. 1998;9(2):40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RT, Brown R, Davis M, Jeffries R, Shenoy U. African Americans in behavioral therapy and research: The need for cultural consideration. In: Jones RT, editor. African American mental health. Vol. 1. Hampton, VA: Cobb & Henry; 1998. pp. 413–450. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Holland L, Crowley M. Family experience of barriers to treatment and premature termination from child therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Goldston D, Gatsonis C. Suicidal behaviors and childhood-onset depressive disorders: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:8–20. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Hopfer C. An introduction to motivational interviewing; Paper presented at the Blending Clinical Practice and Research: Forging Partnerships in the Rocky Mountain States to Enhance Drug Addiction Treatment conference; Westminster, CO. 2003. Sep, [Google Scholar]

- Maultsby MC. Historical view of Blacks’ distrust of psychiatry. In: Turner SM, Jones RT, editors. Behavior therapy and black populations: Psychosocial issues and empirical findings. New York: Plenum Press; 1982. pp. 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP, editor. Black families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- McGoldrick M, Giordano J, Pearce JK. Ethnicity and family therapy. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Stoewe J, McCadam K, Gonzales J. Increasing access to child mental health services for urban children and their caregivers. Health and Social Work. 1998;23:9–15. doi: 10.1093/hsw/23.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMiller WP, Weisz JR. Help-seeking preceding mental health clinic intake among African-American, Latino, and Caucasian youths. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1086–1094. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199608000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouton CP, Harris S, Rovi S, Solorzano P, Johnson MS. Barriers to Black women’s participation in cancer clinical trials. Journal of the National Medical Association. 1997;89:721–727. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors HW. Mental health. In: Jackson JS, editor. Life in Black America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 221–237. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Depression in children and adolescents: A fact sheet for physicians. (NIH Publication No. 00-4744) 2000 October 28; Retrieved February 12, 2003, from http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/depchildresfact.cfm.

- Pastore DR, Juszczak L, Fisher MM, Friedman SB. School-based health center utilization: A survey of users and nonusers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1998;152:763–767. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.8.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Galloway GP, Palmer J, Mains W. The case for high-dose motivational enhancement therapy. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:331–343. doi: 10.1081/ja-120028494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poussaint AF, Alexander A. Lay my burden down: Unraveling suicide and the mental health crisis among African-Americans. Boston: Beacon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change: Applications to addictive behaviors. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick R. Changing community behaviour: Experience from three African countries. International Journal of Environmental Research. 2003;13(Suppl 1):S115–121. doi: 10.1080/0960312031000102877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Heather N, Bell A. Negotiating behaviour change in medical settings: The development of brief motivational interviewing. Journal of Mental Health. 1992;1:25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rones M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rounsaville BJ, Carroll KM, Onken LS. A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2001;8:133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J, Freese J, Powell B. Nature, nurture, neither, nor: Black-White differences in beliefs about the causes and appropriate treatment of mental illness. Social Forces. 2000;78:1101–1132. [Google Scholar]

- Scott LD. Correlates of coping with perceived discriminatory experiences among African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92:563–572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Factors that influence African-Americans’ willingness to participate in medical research studies. Cancer. 2001;91(Suppl 1):233–236. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010101)91:1+<233::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-8. [erratum appears in Cancer 91(6),1187] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Annals of Epidemiology. 2002;12:248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3:181–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1013172913880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR. Bias in mental health assessment and intervention: Theory and evidence. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:239–243. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden LR, Thomas K. Medicaid and African American outpatient mental health treatment. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:115–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1010161222515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song D, Sands RG, Wong YL. Utilization of mental health services by low-income pregnant and postpartum women on medical assistance. Women and Health. 2004;39:1–24. doi: 10.1300/J013v39n01_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson HC, Reed J, Bodison P, Bishop A. Racism stress management: Racial socialization beliefs and the experience of depression and anger in African American youth. Youth and Society. 1997;29:197–222. [Google Scholar]

- Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee. Report of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee. 1996 May 20; Retrieved September 23, 2001, from http://www.med.virginia.edu/hs-library/historical/apology/report.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity: A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general (Report No. 0-16-050892-4) Rockville, MD: Author, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Velicer WF, Prochaska JO. An expert system intervention for smoking cessation. Patient Education & Counseling. 1999;36:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees CC, Stillman FA, Swank RT, Heagerty PJ, Levine DM, Becker DM. Heart, body, and soul: Impact of church-based smoking cessation interventions on readiness to quit. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:277–285. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walcott-McQuigg JA, Prochaska TR. Factors influencing participation of African American elders in exercise behavior. Public Health Nursing. 2001;18:194–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2001.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp F, Brink KL, Roberson MK, Ortiz IE. Variables which differentiate placement of adolescents into juvenile justice or mental health systems. Adolescence. 1986;21(81):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Cohen P, Liu XH, Moore RE, Tiet Q, et al. Factors associated with use of mental health services for depression by children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:189–195. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh M, McCabe K, Hurlburt M, Hough R, Hazen A, Culver S, et al. Referral sources, diagnoses, and service types of youth in public outpatient mental health care: A focus on ethnic minorities. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research. 2002;29:45–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02287831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Magder LS, Riddle MA. Methylphenidate patterns among Medicaid youths. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1997;33:143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]