Abstract

In the present study the effect of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) was studied on a native TRPC1 store-operated channel (SOC) in freshly dispersed rabbit portal vein myocytes. Application of diC8-PIP2, a water soluble form of PIP2, to quiescent inside-out patches evoked single channel currents with a unitary conductance of 1.9 pS. DiC8-PIP2-evoked channel currents were inhibited by anti-TRPC1 antibodies and these characteristics are identical to SOCs evoked by cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and BAPTA-AM. SOCs stimulated by CPA, BAPTA-AM and the phorbol ester phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu) were reduced by anti-PIP2 antibodies and by depletion of tissue PIP2 levels by pre-treatment of preparations with wortmannin and LY294002. However, these reagents did not alter the ability of PIP2 to activate SOCs in inside-out patches. Co-immunoprecipitation techniques demonstrated association between TRPC1 and PIP2 at rest, which was greatly decreased by wortmannin and LY294002. Pre-treatment of cells with PDBu, which activates protein kinase C (PKC), augmented SOC activation by PIP2 whereas the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine decreased SOC stimulation by PIP2. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments provide evidence that PKC-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1 occurs constitutively and was increased by CPA and PDBu but decreased by chelerythrine. These novel results show that PIP2 can activate TRPC1 SOCs in native vascular myocytes and plays an important role in SOC activation by CPA, BAPTA-AM and PDBu. Moreover, the permissive role of PIP2 in SOC activation requires PKC-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1.

In vascular smooth muscle canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channels are involved in many physiological responses including contraction, cell growth, proliferation and migration (see Large, 2002; Beech et al. 2004; Firth et al. 2007). A key question concerns the activation mechanism of TRPC channels, which are frequently described as either receptor-operated or store-operated channels (ROCs and SOCs, respectively). In freshly dispersed vascular myocytes TRPC ROCs are stimulated by G-protein-coupled agonists such as noradrenaline, angiotensin II (Ang II) or endothelin-1 (ET-1) coupled to either phospholipase C (PLC, TRPC6 in rabbit portal vein, Inoue et al. 2001; mesenteric artery, Saleh et al. 2006; TRPC3/TRPC7 in rabbit coronary artery, Peppiatt-Wildman et al. 2007) or phospholipase D (TRPC3 in rabbit ear artery, Albert et al. 2005,2006). In all these cases it seems that diacylglycerol (DAG) which is produced by phospholipase stimulation plays an important role in channel activation and may actually be the gating molecule (Albert & Large, 2006; Albert et al. 2008). SOCs are activated by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores and there is now considerable evidence that TRPC proteins also form SOCs in native vascular smooth muscle with both TRPC1 and TRPC5 as suggested components of SOCs (Xu & Beech, 2000; Xu et al. 2006; Saleh et al. 2006,2008). In vascular smooth muscle protein kinase C (PKC) appears to have an important role in activation of TRPC SOCs (Albert & Large, 2002b; Albert et al. 2007). In addition Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 has also been suggested to be involved in activating SOCs (Smani et al. 2004).

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is an important signalling molecule, which is cleaved by PLC to inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and DAG and both these products have well established cellular effects. However, recently there has been much interest in the direct actions of PIP2 on ion channels, including TRP channels (Suh & Hille, 2005; Hardie, 2007; Rohacs, 2007; Voets & Nilius, 2007; Nilius et al. 2008). In HEK293 cells PIP2 increased activity of expressed TRPC3, TRPC6 and TRPC7 channel activity (Lemonnier et al. 2008), decreased TRPC4α activity (Otsuguro et al. 2008) and produced complex effects on TRPC5 channels (Trebak et al. 2008). In freshly dispersed vascular myocytes we demonstrated that endogenous PIP2 inhibited native TRPC6 channels (Albert et al. 2008). These data indicated that PIP2 was bound to TRPC6 in unstimulated cells and following receptor stimulation by Ang II, optimal channel stimulation was produced by hydrolysis of this bound PIP2 and simultaneous activation of TRPC6 channels by DAG, possibly at the same PIP2-binding site on the channel molecule (Albert et al. 2008).

In the present study we investigated the role of PIP2 in activation of native TRPC1 SOCs in rabbit portal vein myocytes, which have characteristics of a heterotetrameric channel consisting of TRPC1/TRPC5/TRPC7 subunits (Saleh et al. 2008). These results show that PIP2 stimulates this ion channel and that there is an obligatory role for endogenous PIP2 in TRPC1 SOC activation.

Methods

Cell Isolation

New Zealand White rabbits (2–3 kg) were killed using i.v. sodium pentobarbitone (120 mg kg−1, in accordance with the UK Animals Scientific Procedures Act, 1986). Portal vein was dissected free from fat and connective tissue and enzymatically digested into single myocytes using methods previously described (Saleh et al. 2006).

Electrophysiology

Single cation currents were recorded with an HEKA EPC8 patch-clamp amplifier (HEKA Instruments Inc., Bellmore, NY, USA) at room temperature (20–23°C) using cell-attached and inside-out patch configurations (Hamill et al. 1981) and data acquisition and analysis protocols as previously described (Saleh et al. 2006). Briefly, single channel current amplitudes were calculated from idealized traces that were filtered off-line at 100 Hz with an 8-pole Bessel filter (Frequency Devices, Haverhill, MA, USA) and sampled at 1 kHz. Traces of at least 60 s in duration were used to calculate open probability and construct fitted-level amplitude histograms and events lasting for < 6.664 ms (2 × rise time for a 100 Hz, −3 db, low pass filter) were excluded from analysis using the 50% threshold method. Figure preparation was carried out using Origin 6.0 (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA, USA) where inward single channel currents are shown as downward deflections. Open probability (NPo) was calculated using the equation:

where n is number of simultaneously open channels in the patch, On is time spent at the open level for each channel (i.e. n− 1) and T is total recording time.

The relationship between NPo and PIP2 concentration ([PIP2]) for inside out patches was fitted with the Hill equation:  where ymax= maximum NPo, Kd is the apparent dissociation constant and nH is the Hill coefficient.

where ymax= maximum NPo, Kd is the apparent dissociation constant and nH is the Hill coefficient.

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting

Total cell lysate (TCL) was extracted and quantified as previously described (Saleh et al. 2008). The immunoprecipitation protocol was carried out using the Catch and Release® kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY, USA), where spin columns were loaded with 300–600 μg of cell lysates, 2–4 μg of antibody, 2 μg of β-actin antibody, and immunoprecipitated on an end-over-end stirrer for 2 h at room temperature.

Protein samples were eluted with Laemmli sample buffer and incubated at 60°C for 5 min. One-dimensional protein gel electrophoresis, semi-dry transfer and Western blot procedures were performed as previously described (Saleh et al. 2008). Whenever possible, alternative antibodies raised against different epitopes were used for immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis. Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-mouse (Sigma) and donkey anti-goat (Millipore) antibodies were added according to the host species of the primary antibody used for the Western blot and subsequently detected with ECL reagents (Saleh et al. 2008). In loading control experiments anti-β-actin antibodies (mouse monoclonal, Sigma, UK) were also added to the immunoprecipitate and immunoblot procedures to show that expression levels of β-actin did not change during the experimental conditions. Moreover immunoblot control data showed that anti-PIP2 and anti-TRPC1 antibodies did not recognize β-actin following immunoprecipitation with only anti-β-actin antibodies. Data shown represent n-values of at least three separate experiments.

Anti-TRPC1, anti-PIP2 and anti-phosphoserine/threonine antibodies

Polyclonal antibodies for TRPC1 raised against different intracellular epitopes were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Alomone Laboratories (Jerusalem, Israel). The specificity of these antibodies for their target proteins have been previously confirmed (Liu et al. 2005b; Sours et al. 2006). Mouse monoclonal PIP2 antibody generated against liposomes of human origin constituted with the phospholipid (Osborne et al. 2001) was purchased from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology and has a predicted molecular mass of 74 kDa according to the manufacturer's specifications. This anti-PIP2 antibody has previously been used in electrophysiological (Liou et al. 1999; Bian et al. 2001; Ma et al. 2002; Pian et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2008) and immunoprecipitation experiments (Asteggiano et al. 2001; Beauge et al. 2002; Yue et al. 2002) to investigate the role of PIP2 in regulating ion channels and exchangers. Anti-phosphoserine and anti-phosphothreonine antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology and both were used together in immunoprecipitation and Western blotting experiments.

Solutions and drugs

In cell-attached patch experiments the membrane potential was set to 0 mV by perfusing cells in a KCl external solution containing (mm): KCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10) and glucose (11), pH to 7.2 with 10 m KOH. Nicardipine (5 μm) was also included to prevent smooth muscle cell contraction by blocking Ca2+ entry through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Immediately prior to patch excision for inside-out recordings and within a 30 s period the bathing solution was exchanged for an intracellular solution containing (mm): CsCl (18), caesium aspartate (108), MgCl2 (1.2), Hepes (10), glucose (11), BAPTA (1), CaCl2 (0.48, free internal Ca2+ concentration approximately 100 nm as calculated using EqCal software; Biosoft, Great Shelford, UK), Na2ATP (1), NaGTP (0.2) pH 7.2 with Tris. U73122 at 2 μm and 50 nm wortmannin were also included for all experiments with diC8-PIP2 to prevent conversion of PIP2 into IP3, DAG and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3).

The patch pipette solution used for both cell-attached and inside-out patch recording (extracellular solution) was K+ free and contained (mm): NaCl (126), CaCl2 (1.5), Hepes (10), glucose (11), TEA (10), 4-AP (5), iberiotoxin (0.0002), DIDS (0.1), niflumic acid (0.1) and nicardipine (0.005), pH to 7.2 with NaOH. Under these conditions VDCCs, K+ currents, swell-activated Cl− currents and Ca2+-activated conductances are abolished and non-selective cation currents could be recorded in isolation.

DiC8-PIP2 was from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) whilst all other drugs were purchased from Calbiochem (UK), Sigma (UK) or Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK). Reagents were dissolved in distilled H2O or DMSO (0.1%) and DMSO alone had no effect on SOC activity. The values are the mean of n cells ±s.e.m. Statistical analysis was carried out using Students’ t test for paired (comparing effects of agents on the same cell) or unpaired data (comparing effects of agents between cells) with the level of significance set at P < 0.05.

Results

DiC8-PIP2 activates TRPC1 SOCs in rabbit portal vein myocytes

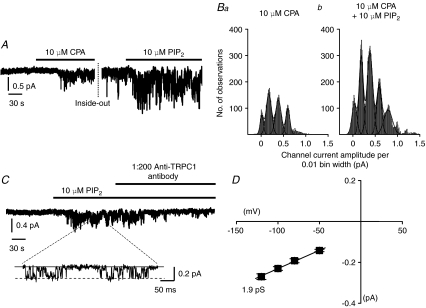

In the first series of experiments we investigated the effect of exogenous diC8-PIP2, a water-soluble form of PIP2, on cyclopiazonic acid (CPA)-evoked SOC activity in inside-out patches. In these experiments we initially evoked SOC activity by bath applying the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor CPA (10 μm) to cell-attached patches and when channel activity reached plateau levels patches were excised into the inside-out configuration. SOC activity was maintained in excised patches for periods of up to 45 min and did not run down in the presence of ATP and GTP. This configuration allowed diC8-PIP2 to be bath applied to the cytosolic surface of the patches. Figure 1A shows that bath application of 10 μm diC8-PIP2 to inside-out patches significantly increased mean open probability (NPo) of CPA-evoked SOC activity from 0.18 ± 0.05 to 0.37 ± 0.07 at −80 mV (n= 5, P < 0.05) and this effect was readily reversed following the removal of diC8-PIP2 (not shown). The bathing solution also contained 2 μm U73122 and 50 nm wortmannin (see Methods) to ensure that this was an effect of PIP2 itself and not a metabolite. Channel current amplitude histograms shown in Fig. 1B illustrate that CPA-evoked channel currents had similar peak amplitudes in the absence (Fig. 1Ba) and presence (Fig. 1Bb) of diC8-PIP2, which suggests that diC8-PIP2 increased activity of the same CPA-induced channels.

Figure 1. diC8-PIP2 activates TRPC1 SOCs in rabbit portal vein myocytes.

A, bath application of 10 μm CPA evoked SOC activity in a cell-attached patch held at −80 mV. After excision into the inside-out configuration, SOC activity was potentiated by bath application of 10 μm diC8-PIP2. B, fixed level channel current amplitude histograms of SOC activity shown in A. Histograms could be fitted by the sum of several Gaussian curves showing the presence of more than one channel in the patch. Note that the peaks of the Gaussian curves have similar values in the absence (a) and presence of diC8-PIP2 (b) indicating that this phospholipid increased the activity of the same channel. C, bath application of 10 μm diC8-PIP2 activated channel currents in a quiescent inside-out patch held at −80 mV which were inhibited by anti-TRPC1 antibodies (Santa Cruz, 1: 200 dilution). D, diC8-PIP2-induced channel currents had a slope conductance of 1.9 pS between −120 and −50 mV.

To investigate whether diC8-PIP2-induced increases in SOC activity were due to either potentiation of CPA-evoked responses or direct activation of SOCs, we studied the effect of diC8-PIP2 on quiescent inside-out patches in the presence of 2 μm U73122 and 50 nm wortmannin. Figure 1C and D shows that bath application of 10 μm diC8-PIP2 to an inside-out patch activated channel currents which had a mean NPo of 0.27 ± 0.04 (n= 16) at −80 mV and a slope conductance between −50 mV and −120 mV of 1.9 pS. These data indicate that diC8-PIP2 activates channel currents with a similar conductance to that of native TRPC SOCs previously described in portal vein myocytes (Albert & Large, 2002a; Saleh et al. 2008). TRPC1 has been previously proposed to be a component of SOCs in portal vein myocytes (Saleh et al. 2008) and Fig. 1C shows that bath application of an anti-TRPC1 antibody (1: 200 dilution) significantly inhibited diC8-PIP2-induced channel activity by 76 ± 6% at –80 mV (n= 5, P < 0.01). This inhibition was abolished when the antigenic peptide (also 1: 200 dilution) was preincubated with the antibody (n= 5, data not shown).

Effect of an anti-PIP2 antibody on SOC activity

The above results indicate that exogenous diC8-PIP2 activates ion channels with properties similar to TRPC1 SOCs previously described in portal vein myocytes (cf. Albert & Large, 2002a; Saleh et al. 2008). Therefore we investigated the role of endogenous PIP2 in activating these SOCs by studying the effect of an anti-PIP2 antibody on SOCs in inside-out patches.

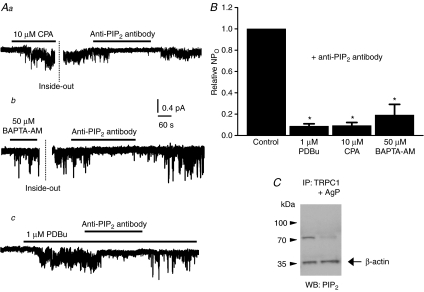

In the first experiments SOC activity was induced in cell-attached patches by CPA or BAPTA-AM and then patches were excised and anti-PIP2 antibodies were applied to the internal membrane surface of the patches. Figure 2Aa and b and B shows that mean NPo of SOC activity, initially induced by 10 μm CPA or 50 μm BAPTA-AM, was significantly inhibited by anti-PIP2 antibodies (1: 200 dilution) by 91 ± 3% (n= 7) and 82 ± 9% (n= 7), respectively. This effect was not seen when the anti-PIP2 antibody was denatured prior to application by boiling for a period of 30 min (n= 4, data not shown). In addition Fig. 2Ac and B show that anti-PIP2 antibodies also produced marked inhibition of SOC activity induced by the PKC-activating phorbol ester phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate (PDBu, 1 μm), which has been previously shown to activate SOCs in this preparation (Albert & Large, 2002b; Saleh et al. 2008). In these experiments inside-out patches were prepared from quiescent cells before application of PDBu and anti-PIP2 antibodies, which significantly reduced activity by 92 ± 2% (n= 5). Figure 2C shows that tissue lysates from portal vein immunoprecipitated with anti-TRPC1 antibodies then Western blotted with anti-PIP2 antibodies detected a band of ∼70 kDa, which is the predicted band for the PIP2 complex with this antibody (see Methods). Moreover Fig. 2C shows that preincubation of anti-TRPC1 antibodies with its antigenic peptide (AgP) reduced detection of the band with anti-PIP2 antibodies without affecting expression levels of β-actin proteins.

Figure 2. Anti-PIP2 antibodies inhibit TRPC1 SOC activity.

A, bath application of anti-PIP2 antibodies (1: 200 dilution) to the cytosolic surface of inside-out patches held at –80 mV markedly inhibited SOC activity initially induced by 10 μm CPA (a) or 50 μm BAPTA-AM (b) in cell-attached patches and 1 μm PDBu (c) applied to a quiescent inside-out patch. B, mean data showing that anti-PIP2 antibodies significantly reduced SOC activity evoked by CPA, BAPTA-AM and PDBu (*P < 0.05). C, co-immunoprecipitation experiments where tissue lysates from portal vein were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-TRPC1 antibody (Santa Cruz) and then Western blotted (WB) with an anti-PIP2 antibody. In control conditions a band of ∼70 kDa was observed (see Methods), which was absent after pre-treatment of the anti-TRPC1 antibody with its antigenic peptide (AgP). Note that bands detected with an anti-β-actin antibody were unaffected by pretreatment with the antigenic peptide.

Agents that deplete PIP2 levels inhibit SOC activity

These data suggest that endogenous PIP2 associated with TRPC1 proteins may have an important role in activating SOCs in portal vein myocytes. Therefore we investigated the effect of depleting endogenous PIP2 levels on SOC activity in cell-attached patches. To deplete PIP2 we used 20 μm wortmannin and 100 μm LY294002 which at these concentrations inhibit phosphoinositol (PI)-4-kinases leading to a reduction in generation of PIP2 and consequently a depletion of tissue PIP2 levels (Suh & Hille, 2005; Albert et al. 2008).

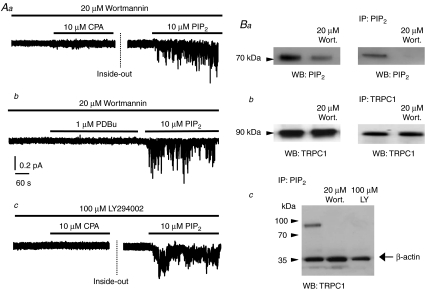

Figure 3Aa and b shows that pretreatment of portal vein myocytes with 20 μm wortmannin for 15 min almost obliterated the ability of CPA and PDBu to induce SOC activity, and mean NPo was decreased by 98 ± 1% (n= 8) and 97 ± 2% (n= 9), respectively, compared to untreated control cells (n= 6 and n= 5). Moreover Fig. 3Ac shows that pretreatment of myocytes with 100 μm LY294002 for 15 min also reduced NPo of CPA-induced SOC activity by a mean value of 99 ± 1% (n= 6) compared to control cells (n= 6). However Fig. 3Aa–c shows that in cells pretreated with wortmannin or LY294002, bath application of 10 μm diC8-PIP2 in the inside-out configuration was still able to induce SOC activity. In the presence of wortmannin mean NPo of CPA- and PDBu-induced SOC activity was significantly increased by diC8-PIP2 from, respectively, 0.02 ± 0.01 to 0.29 ± 0.07 (n= 4, P < 0.05) and 0.02 ± 0.01 to 0.51 ± 0.09 (n= 5, P < 0.05). In addition, in the presence of LY294002 the mean NPo of CPA-evoked SOC activity was significantly enhanced from 0.01 ± 0.01 to 0.12 ± 0.05 (n= 3, P < 0.05) by diC8-PIP2.

Figure 3. depletion of endogenous PIP2 inhibits SOC activity.

A, pre-treatment of portal vein tissue with 20 μm wortmannin for 15 min prevented SOC activation by 10 μm CPA (a) in cell-attached patches and 1 μm PDBu (b) in inside-out patches held at –80 mV. Pre-treatment with 100 μm LY294002 also inhibited SOC activity induced by CPA in a cell-attached patch held at –80 mV (c). Note that in inside-out patches diC8-PIP2 activated SOC activity in the presence of wortmannin (a and b) and LY294002 (c). Ba, pre-treatment of tissue lysates from portal vein with 20 μm wortmannin for 15 min reduced total PIP2 levels detected with WB (left panel) and following IP and WB (right panel) using anti-PIP2 antibodies. Bb, pre-treatment with 20 μm wortmannin had no effect on expression levels of TRPC1 detected with WB and following IP and WB using anti-TRPC1 antibodies (Santa Cruz). Bc, co-immunoprecipitation experiment showing that pre-treatment of portal vein tissue with 20 μm wortmannin and 100 μm LY294002 inhibited association of PIP2 with TRPC1 proteins following IP with anti-PIP2 and WB with anti-TRPC1 antibodies.

To confirm that wortmannin and LY294002 lowered PIP2 levels we carried out co-immunoprecipitation and Western blotting studies. Figure 3Ba shows that pretreatment of portal vein tissue with 20 μm wortmannin reduced total PIP2 levels measured with Western blotting (Fig. 3Ba left panel) and following immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3Ba right panel). In addition Fig. 3Bb illustrates that pre-treatment of portal vein tissue with 20 μm wortmannin did not alter expression levels of TRPC1 proteins, which were detected as bands at a molecular mass of ∼90 kDa (see Methods). Moreover Fig. 3Bc shows that pretreatment of portal vein tissue with either 20 μm wortmannin or 100 μm LY294002 predictably reduced association of PIP2 with TRPC1 proteins.

These results provide powerful evidence that endogenous PIP2 is obligatory for SOC activation by CPA and PDBu in portal vein myocytes. Moreover these data indicate that interactions between TRPC1 proteins and PIP2 have an important role in stimulating SOC activity.

Protein kinase C regulates diC8-PIP2-induced activation of SOCs

We have previously shown that PKC inhibitors chelerythrine and Ro 31-8220 inhibit SOCs activated by CPA, PDBu and BAPTA-AM in rabbit portal vein myocytes (Albert & Large, 2002b; Liu et al. 2005a) and in other vascular preparations (Saleh et al. 2006,2008). As the present work indicates that PIP2 is also obligatory for SOC activation we investigated whether these two pathways were dependent on one another or could activate SOCs independently.

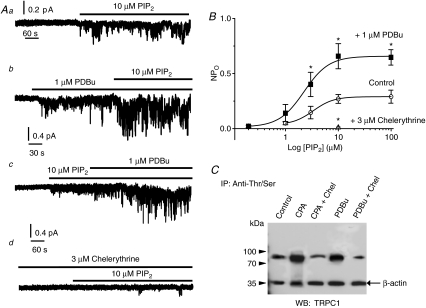

Figure 4Aa and b compares control responses to diC8-PIP2 to responses in cells pretreated with 1 μm PDBu, a PKC activator, for 15 min in inside-out patches held at –80 mV. These data show that mean NPo of SOC activity induced by 10 μm diC8-PIP2 was significantly increased from 0.27 ± 0.04 (n= 16) to 0.72 ± 0.15 (n= 5, P < 0.01) in the presence of PDBu. Figure 4Ac shows that the same experiment done in reverse, i.e. PDBu applied after PIP2, also enhanced PIP2-evoked SOC activity from 0.33 ± 0.06 to 0.86 ± 0.14 (n= 6, P < 0.01). In contrast pre-application of the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine greatly reduced the ability of 10 μm diC8-PIP2 to activate SOCs (Fig. 4Ad and B. Figure 4B shows mean concentration–response curves of diC8-PIP2-activated SOCs in control conditions and following pre-treatment with either PDBu or chelerythrine, and clearly illustrates that PDBu increased mean NPo of diC8-PIP2-induced SOC activity at all concentrations tested and produced a larger maximum response. Interestingly, the concentration–response curves of diC8-PIP2-induced SOC activity had similar nH values of 1.7 and 1.6 in the absence and presence of PDBu, respectively, whilst the EC50 values were also similar in all conditions, around 3 μm. Thus the major effect of PDBu appears to be an increase in the number of available channels in the normal concentration range of PIP2.

Figure 4. PKC-dependent phosphorylation associated with TRPC1 proteins is pivotal for activation of SOC activity by diC8-PIP2.

Aa, control response of 10 μm diC8-PIP2 applied to the internal surface of an inside-out patch. b, 1 μm PDBu greatly enhanced responses to diC8-PIP2 in patches held at –80 mV. c, a representative trace where 10 μm diC8-PIP2 was applied to an inside-out patch first and subsequent addition of PDBu potentiated channel activity. d, pre-incubation with 3 μm chelerythrine almost completely abolished the ability of diC8-PIP2 to activate SOCs. B, mean concentration–response curves of diC8-PIP2-induced SOC activity in inside-out patches held at –80 mV fitted with Hill plots (see Methods) in control conditions and in the presence of PDBu and chelerythrine. In the presence of 1 μm PDBu the diC8-PIP2-evoked increase in NPo was obtained by subtracting the value in PDBu alone from the NPo in PDBu plus diC8-PIP2. Note that the EC50 values of the concentration–response curves in control conditions and in the presence of PDBu are similar ∼3 μm. Each point is from at least n= 4, *P < 0.05. C, co-immunoprecipitation experiments showing that pre-treatment of portal vein tissue with 10 μm CPA and 1 μm PDBu increases phosphorylated serine and threonine residues on TRPC1 proteins detected on Western blots. Note that CPA- and PDBu-evoked increases in TRPC1 phosphorylation are inhibited by pre-incubation with 3 μm chelerythrine.

Protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1

These data with chelerythrine indicate that constitutive PKC activity is required for activation of SOCs by diC8-PIP2 and that increased PKC stimulation augments diC8-PIP2 induced activation of SOCs. Therefore we investigated the effect of agents that activate SOC activity on PKC-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1 proteins and also their effect on PIP2 interactions with TRPC1 proteins using immunoprecipitation methods.

Figure 4C shows that unstimulated tissue lysates from portal vein immunoprecipitated with both anti-phosphoserine and -threonine antibodies then blotted with anti-TRPC1 detected a band of ∼90 kDa. In addition Fig. 4C shows that pre-treatment of tissue lysates with 10 μm CPA and 1 μm PDBu increased intensity of the TRPC1 protein bands, which were inhibited by pre-incubation with 3 μm chelerythrine. Pre-treatment with 20 μm wortmannin had no effect on unstimulated, CPA- or PDBu-induced phosphorylation of TRPC1 proteins (data not shown). Interestingly pre-treatment of tissue lysates from portal vein with 10 μm CPA or 1 μm PDBu for 15 min did not alter the level of association between TRPC1 proteins and PIP2 (data not shown). These data indicate that TRPC1 proteins are constitutively phosphorylated and that this phosphorylation can be increased by CPA and PDBu.

These co-immunoprecipitation data together with functional studies suggest that CPA and PDBu increase PKC-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1 proteins, which promotes PIP2-mediated SOC activity.

Discussion

The results from the present study show that PIP2 activates a TRPC1 SOC in freshly dispersed rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells. In addition, evidence is presented which indicates that endogenous PIP2 is required for SOC activation in response to agents that deplete intracellular Ca2+ stores. To our knowledge these findings are the first to report that PIP2 activates a native TRPC1 SOC.

We initially found that PIP2 augmented SOC activity when applied to the cytosolic surface of patches where activity had been first induced by the Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor CPA. Subsequently we also found that PIP2 alone applied to the cytosolic surface of a quiescent inside-out patch readily activated the same 2 pS non-selective cation channel. Moreover anti-TRPC1 antibodies inhibited the PIP2-evoked channel activity as seen in previous studies where the channel was activated by CPA and BAPTA-AM (Saleh et al. 2008). These characteristics of the PIP2-evoked channel are similar to the properties of channel currents evoked by store-depletors previously described in this preparation (Albert & Large, 2002a; Liu et al. 2005a; Saleh et al. 2008). PIP2-evoked channel currents were observed in the presence of the PLC inhibitor U73122 and 50 nm wortmannin, which selectively inhibits phosphoinositol-3-kinase. Consequently PIP2, and not a metabolite, activates the ion channel, which has properties of a TRPC1/TRPC5/TRPC7 heterotetramer (Saleh et al. 2008).

Role of endogenous PIP2 in SOC stimulation

Single channel activity evoked by CPA, BAPTA-AM or PDBu was markedly inhibited by an anti-PIP2 antibody and this inhibitory effect was abolished when the antibody was denatured. Moreover, the same anti-PIP2 antibody increased TRPC6 channel activity in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes where PIP2 had an inhibitory role (Albert et al. 2008), which suggests that this is not a non-selective effect of this antibody. Treatment with high concentrations of wortmannin and LY294002, which depleted total tissue PIP2 levels, almost obliterated SOC channel activation by CPA and PDBu. However, in the same cells, in the inside-out configuration PIP2 always evoked SOC activity when applied to the internal surface of the membrane indicating that the channels functioned normally. Co-immunoprecipitation studies illustrated that TRPC1 was associated with PIP2 in portal vein tissue, whilst treatment with wortmannin or LY294002 depleted both total tissue PIP2 levels and reduced co-association between TRPC1 and PIP2. Together these results strongly indicate an obligatory role for endogenous PIP2 in activation of the TRPC1 SOC by store-depleting reagents in portal vein myocytes.

Interaction between PIP2 and PKC on TRPC1 SOC activation

We have previously shown that CPA-evoked SOCs in the portal vein are dependent on PKC for activation (Albert & Large, 2002b; Saleh et al. 2008). The present work demonstrates that agents which affect PKC activity had a profound effect on the ability of PIP2 to activate SOCs. PIP2 produced a much larger increase in channel NPo in cells pre-treated with a PKC activator compared to control cells. Interestingly there was little change in the concentration range at which PIP2 evoked channel activity. Instead in the presence of PDBu effective PIP2 concentrations produced greater channel activity with an increased maximum response. These effects were most likely to be due to an increase in the number of active channels within the patch and not to channel insertion since the experiments were carried out in the inside-out configuration. Furthermore in cells pre-treated with the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine there was marked suppression of PIP2-evoked channel activity. These data indicate that PKC-dependent phosphorylation of the SOC regulates the ability of PIP2 to activate the channel. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments provided evidence that TRPC1 is phosphorylated constitutively and that CPA and PDBu increased the levels of TRPC1 phosphorylation. Previously we have reported that the phosphatase inhibitor calyculin A induced SOC activity also suggesting constitutive phosphorylation of SOCs (Albert & Large, 2002b). Therefore our data suggest that the ability of PIP2 to evoke the SOC depends on PKC-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1 and previously it has been shown that PKCα-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1 regulates store-operated Ca2+ entry in cultured endothelial cells (Ahmmed et al. 2004). Interestingly TRPC1 co-associated with PIP2 in unstimulated cells and this interaction did not appear to be increased by CPA or PDBu. Therefore it is possible that PIP2 is tethered to TRPC1 at rest but only activates the channel when TRPC1 is phosphorylated by PKC.

Recently several studies have implicated a role for stromal interaction molecule-1 (STIM1) in the activation of SOCs composed of TRPC1 and Orai1 complexes in heterologous expression systems (Huang et al. 2006; Ong et al. 2007; Yuan et al. 2007) and cultured smooth muscle cells (Li et al. 2008). The roles of STIM-1 or Orai1 have not been assessed in native vascular preparations but it will be of future interest to see if portal vein SOCs are composed of STIM1/TRPC1/Orai1 ternary complexes and whether STIM1 can activate these channels in the absence of PIP2 or PKC phosphorylation.

Conclusions

This study shows that PIP2 activates a native SOC with TRPC1 properties in vascular myocytes. Previously we postulated that this SOC may possess a TRPC1/TRPC5/TRPC7 heteromeric structure. Moreover it appears that endogenous PIP2 is obligatory for channel activation by agents such as CPA, BAPTA-AM and PDBu. Finally PIP2 stimulation of the SOC appears to be regulated by PKC-dependent phosphorylation of TRPC1 induced by procedures that deplete internal Ca2+ stores. In physiological conditions SOCs are activated by G-protein-coupled receptor stimulation that often utilizes PLC-mediated cleavage of PIP2 to produce IP3 and DAG. It seems curious that an agonist that decreases the concentration of PIP2, which is essential for SOC activation, is able to activate these channels (Albert & Large, 2002b). It is possible that there are separate microdomains of PIP2; one pool of PIP2 may be in a complex with the pharmacological receptor and PLC while a second pool of PIP2, which is not accessible to PLC, may be linked to the TRPC1 SOC complex. Further experiments are needed to test this hypothesis. It is clear from the present work that endogenous PIP2 is required for activation of TRPC1 SOC, in contrast to its effect on TRPC6 ROC where PIP2 is an endogenous inhibitor of channel activation by DAG (Albert et al. 2008).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust.

References

- Ahmmed GU, Mehta D, Vogel S, Holinstat M, Paria BC, Tiruppathu C, Malik AB. Protein kinase Cα phosphorylates the TRPC1 channel and regulates store-operated Ca2+ entry in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20941–20949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313975200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. A Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channel activated by depletion of internal Ca2+ stores in single rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2002a;538:717–728. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. Activation of store-operated channels by noradrenaline via protein kinase C in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2002b;544:113–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.022574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Large WA. Signal transduction pathways and gating mechanisms of native TRP-like cation channels in vascular myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;570:45–51. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.096875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Piper AS, Large WA. Role of phospholipase D and diacylglycerol in activating constitutive TRPC-like cation channels in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2005;566:769–780. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.090852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Pucovsky V, Prestwich SA, Large WA. TRPC3 properties of a native constitutively active Ca2+-permeable cation channel in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;571:361–373. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.102780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Saleh SN, Large WA. Inhibition of native TRPC6 channel activity by phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate in mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2008;586:3087–3095. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.153676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert AP, Saleh SN, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Large WA. Multiple activation mechanisms of store-operated TRPC channels in smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2007;583:25–36. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.137802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asteggiano C, Berberian G, Beauge L. Phosphatidylinositol- 4,5-bisphosphate bound to bovine cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger displays a MgATP regulation similar to that of the exchange fluxes. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:437–442. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2001.01906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauge L, Asteggiano C, Berberian G. Regulation of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate bound to the bovine cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;976:288–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beech DJ, Muraki K, Flemming R. Non-selective cationic channels of smooth muscle and the mammalian homologues of Drosophila TRP. J Physiol. 2004;559:685–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian J, Cui J, McDonaild TV. HERG K+ channel activity is regulated by changes in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Circ Res. 2001;89:1168–1176. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.101375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth AL, Remillard CV, Yuan JX. TRP channels in hypertension. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC. TRP channels and lipids: from Drosophila to mammalian physiology. J Physiol. 2007;578:9–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GN, Zeng W, Kim JY, Yuan JP, Han L, Muallem S, Worley PF. STIM1 carboxyl-terminus activates native SOC, Icrac and TRPC1 channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/ncb1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Hara Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular a1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res. 2001;88:325–332. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA. Receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channels in vascular smooth muscle: a physiologic perspective. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:493–501. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier L, Trebak M, Putney JW., Jr Complex regulation of the TRPC3, 6 and 7 channel subfamily by diacylglycerol and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Cell Calcium. 2007;43:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Sukumar P, Milligan CJ, Kumar B, Ma ZY, Munsch CM, Jiang LH, Porter KE, Beech DJ. Interactions, functions, and independence of plasma membrane STIM1 and TRPC1 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2008;103:97–104. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou HH, Zhou SS, Huang CL. Regulation of ROMK1 channel by protein kinase A via a phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5820–5825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Albert AP, Large WA. Facilitatory effect of Ins(1,4,5)P3 on store-operated Ca2+-permeable cation channels in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol. 2005a;566:161–171. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Singh BB, Groscher K, Ambudkar IS. Molecular analysis of a store-operated and 2-acetyl-sn-glycerol-sensitive non-selective cation channel. Heteromeric assembly of TRPC1-TRPC3. J Biol Chem. 2005b;280:21600–21606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma HP, Saxena S, Warnock DG. Anionic phospholipids regulate native and expressed epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7641–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T. Transient receptor potential channels meet phosphoinositides. EMBO J. 2008;27:2809–2816. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong HL, Cheng KT, Liu X, Bandyopadhyay BC, Paria BC, Soboloff J, Pani B, Gwack Y, Srikanth S, Singh BB, Gill DL, Ambudkar IS. Dynamic assembly of TRPC1-STIM1- Orai1 ternary complex is involved in store-operated calcium influx. Evidence for similarities in store-operated and calcium release-activated calcium channel components. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9105–9116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608942200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne SL, Thomas CL, Gschmeissner S, Schiavo G. Nuclear PtdIns(4,5)P2 assembles in a mitotically regulated particle involved in pre-mRNA splicing. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2501–2511. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuguro K, Tang J, Tang Y, Xiao R, Freichel M, Tsvilovskyy V, Ito S, Flockerzi V, Zhu M, Zholos AV. Isoform-specific inhibition of TRPC4 channel by phosphatidylinositol 4,5- bisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10026–10036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707306200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Albert AP, Saleh SN, Large WA. Endothelin-1 activates a Ca2+-permeable cation channel with TRPC3 and TRPC7 properties in rabbit coronary artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2007;580:755–764. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pian P, Bucchi A, Robinson RB, Siegelbaum SA. Regulation of gating and rundown of HCN hyperpolarization-activated channels by exogenous and endogenous PIP2. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:593–604. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohacs T. Regulation of TRP channels by PIP2. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:753–762. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh SN, Albert AP, Peppiatt CM, Large WA. Angiotensin II activates two cation conductances with distinct TRPC1 and TRPC6 channel properties in rabbit mesenteric artery myocytes. J Physiol. 2006;577:479–495. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh SN, Albert AP, Peppiatt-Wildman CM, Large WA. Diverse properties of store-operated TRPC channels activated by protein kinase C in vascular myocytes. J Physiol. 2008;586:2463–2476. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.152157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smani T, Zakharov SI, Csutora P, Leno E, Trepakova ES, Bolotina VM. A novel mechanism for the store-operated calcium influx pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;2:113–120. doi: 10.1038/ncb1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sours S, Du J, Chu S, Ding M, Zhou XJ, Ma R. Expression of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) proteins in human glomerular mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1507–F1515. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00268.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B-S, Hille B. Regulation of ion channels by phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trebak M, Lemonnier L, Dehaven WI, Wedel BJ, Bird GS, Putney JW., Jr Complex functions of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate on regulation of TRPC5 cation channels. Pflugers Arch. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0550-1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voets T, Nilius B. Modulation of TRPs by PIPs. J Physiol. 2007;582:939–944. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.132522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie LH, Johm SA, Ribalet B, Weiss JN. Phosphatidylinositol- 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) regulation of strong inward rectifier Kir2.1 channels: multilevel positive cooperativity. J Physiol. 2008;586:18833–11848. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SZ, Beech DJ. TrpC1 is a membrane-spanning subunit of store-operated Ca2+ channels in native vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2000;88:84–87. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SZ, Boulay G, Flemming R, Beech DJ. E3-targeted anti-TRPC5 antibody inhibits store-operated calcium entry in freshly isolated pial arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H2653–H2659. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00495.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan JP, Zeng W, Huang GN, Worley PF, Muallem S. STIM1 heteromultimerizes TRPC channels to determine their function as store-operated channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:636–645. doi: 10.1038/ncb1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue G, Malik B, Yue G, Eaton DC. Phosphatidylinositol 4, 5- bisphosphate (PIP2) stimulates epithelial sodium channel activity in A6 cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:119–1969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]