Abstract

The knee joint consists of multiple interacting tissues that are prone to injury- and disease-related degeneration. Although much is known about the structure and function of the knee's constituent tissues, relatively little is known about their cellular origin and the mechanisms governing their segregation. To investigate the origin and segregation of knee tissues in vivo we performed lineage tracing using a Col2a1-Cre/R26R mouse model system and compared the data obtained with actual Col2a1 expression. These studies demonstrated that at E13.5 the interzone at the presumptive joint site forms when cells within the Col2a1-expressing anlagen cease expression of Col2a1 and not through cellular invasion into the anlagen. Later in development these interzone cells form the cruciate ligament and inner medial meniscus of the knee. At E14.5, after interzone formation, cells that had never expressed Col2a1 appeared in the joint and formed the lateral meniscus. Furthermore, cells with a Col2a1-positive expression history combined with the negative cells to form the medial meniscus. The invading cells started to express Col2a1 1 week after birth, resulting in all cells within the meniscus synthesizing collagen II. These findings support a model of knee development in which cells present in the original anlagen combine with invading cells in the formation of this complex joint.

Keywords: Col2a1, joint formation, knee, lineage tracing, meniscus

Introduction

The mature knee joint is a complex multi-tissued organ in which the distinct tissues interact to mechanically stabilize the joint and allow smooth movement. The outer part of the joint consists of a strong fibrous capsule and synovial membrane that completely encases it. Within this, the two femoral condyles abut the tibial plateaus, all of which are covered in and cushioned by articular cartilage. These two areas of contact are separated by the cruciate ligament, which connects the femur and tibia and stabilizes the joint in combination with the outer collateral ligaments. In addition to the ligaments, the knee is stabilized by the wedge shaped menisci. The menisci are semilunar fibrocartilaginous structures that largely consist of the fibrous-tissue collagen, collagen I (encoded by the Col1a1 and Col1a2 genes), but also the major cartilage collagen, collagen II (encoded by the Col2a1 gene). The menisci form a ring around the two condyles and connect with the cruciate ligament in the centre of the knee, and as a result can be divided into the medial and lateral meniscus. The meniscus is also often discussed in terms of inner and outer areas; the inner part being the thin end of the wedge-shaped tissue closest to the abutting condyles and the outer, the thick end of the wedge (see Fig. 1).

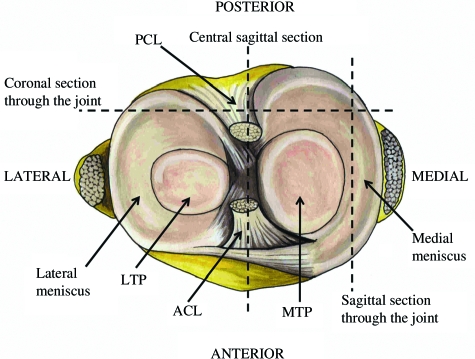

Fig. 1.

A transverse view of the knee joint demonstrating how the meniscus forms a complete circle around the two condyles, joining with the cruciate ligament in the centre of the joint. The meniscus is divided into two halves, the lateral and medial menisci. The planes of sagittal and coronal sections are represented. Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), lateral tibial plateau (LTP), medial tibial plateau (MTP).

The knee is a joint site frequently affected by trauma and disease and hence its component tissues have been a focus of research aimed at understanding their structure and function in both normal and diseased states (Rath & Richmond, 2000; Frank, 2004; Duthon et al. 2006; Goldring & Goldring, 2007). However, relatively little is known about the origin of the cells which constitute the multiple tissues of the knee or the mechanisms whereby these distinct tissues are formed. Recently, lineage tracing has provided new insights into the origin and distinction of joint-forming cells (Rountree et al. 2004; Koyama et al. 2008) and particularly the origin of articular chondrocytes (Hyde et al. 2007). A detailed understanding of the cellular origin of these tissues is crucial for the successful development of novel regenerative/tissue engineering approaches for the treatment of joint-related pathologies.

The long bones of the limbs form during embryogenesis from an initial, continuous Col2a1-expressing anlagen that is subsequently subdivided into the future skeletal elements by joint formation (for a review of joint formation see Khan et al. 2007). Joint formation first becomes morphologically detectable when cells in the presumptive joint region flatten. The region where this occurs is termed the interzone, and it consists of three layers of differing cellular density: two chondrogenic outer layers and a central intermediate zone containing the flattened cells. Interzone formation is also detectable due to the loss of Col2a1 expression and the expression of Col1a1 by the flattened central intermediate zone cells (Craig et al. 1987; Nalin et al. 1995; Archer et al. 2003).

As well as being detectable morphologically and by changes in collagen expression, the interzone can be identified due to the expression of joint markers. One example is the TGF-β super-family member Gdf5, which is expressed across the interzone (Storm & Kingsley, 1996; Francis-West et al. 1999). Lineage tracing using Gdf5-Cre transgenic mice revealed that the cells which have expressed Gdf5 form the articular cartilage and other joint structures such as the synovial lining and capsule tissue (Rountree et al. 2004; Koyama et al. 2008). Our lineage studies using Matn1-Cretransgenic mice demonstrated that articular chondrocytes never express the extracellular matrix protein, matrilin-1, and are therefore distinct from transient chondrocytes (which do express the gene and represent the majority of the anlagen) by E13.5, when the Matn1 gene is first expressed. In addition, a band of matrilin-1-negative, collagen II-positive, spherical cells could be identified from E13.5 onwards, which upon cavitation formed the articular chondrocytes (Hyde et al. 2007). The fact that chondrocytes with an articular phenotype were identifiable at E13.5 suggests that the articular cartilage is not formed from a dispersal of the flattened intermediate zone cells of the interzone but by a sub-population of chondrocytes adjacent to them – although it is possible that some of the flattened cells incorporate into the superficial layers of the developing articular cartilage.

One theory as to the origin of the flattened intermediate zone cells is that they have reverted from their chondrogenic phenotype as characterized by a loss of collagen II expression and the expression of collagen I (Craig et al. 1987; Nalin et al. 1995; Archer et al. 2003). However it has also been suggested that cellular invasion into the joint occurs during development (Pacifici et al. 2006). An invasion of Col2a1-negative, Col1a1-expressing cells into the Col2a1-expressing anlagen would explain the loss of Col2a1observed, and this may be a mechanism by which the intermediate zone and some joint tissues form.

To determine if the tissues of the knee joint develop from the Col2a1-positive anlagen or if cells from outside the anlagen invade into the joint during development, we carried out lineage tracing using the Col2a1-Cre(Sakai et al. 2001) and ROSA26 LacZreporter (R26R) (Mao et al. 1999) mouse strains. Col2a1-Cre/R26R knees were analysed and expression history compared to actual Col2a1expression. The lineage tracing revealed conclusively that it is the resident cells of the anlagen that switch off expression of collagen II to form the interzone at E13.5. However, following interzone formation, cells that have not previously expressed Col2a1 invade the developing knee joint and form the lateral and outer medial meniscus. Incorporating these findings and previously published lineage tracing data, a refined model for knee joint development is proposed.

Materials and methods

Transgenic mouse strains

The ROSA26 LacZ reporter strain (Mao et al. 1999) was maintained as a homozygous line. The Col2a1-Cre mouse line (Sakai et al. 2001) was genotyped via PCR using the Extract N AMP tissue PCR kit (Sigma). The following primers were used to genotype Col2a1-Cre mice and were designed to amplify an ~350-bp fragment from the Cre gene: Forward primer: 5-TCCAATTTACTGACCGTACA-3, Reverse primer: 5-AAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT-3.

Detection of β-galactosidase (LacZ) activity

β-galactosidase activity was detected as previously described, (Hyde et al. 2007). Once-stained mouse embryos were dissected as follows; heads and tails were removed and the embryo cut in half across the stomach to separate the hind- and forelimbs. Internal organs were removed and the limbs splayed out. Tissue samples were compressed between two foam biopsy pads prior to dehydration and wax embedding using a Microm STP 120 processor and a Microm EC 350–1/2 embedder. Embedded limbs were sectioned using a Microm HM 355S and sections were dried overnight at 37 °C prior to been counterstained with eosin.

In situ hybridization

Murine limbs were fixed in 4% (w/v) para-formaldehyde (PFA) (Sigma) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma) for 24 h at 4 °C. Postnatal mouse limbs which had been fixed in preparation for paraffin embedding were decalcified in 20% (w/v) EDTA, 4% (w/v) PFA in PBS at 4 °C. Decalcification was carried out for between 3 days and 2 weeks, depending upon the size of the limbs. Once fixed and decalcified embryo dissection, embedding and sectioning was carried out as described above. The Col2a1 probe was synthesized from I.M.A.G.E. clone #735113 (purchased from the geneservice I.M.A.G.E. consortium). The clone consisted of an ~600-bp fragment that included a 3′ region of the Col2a1cDNA in the pT7T3 vector (Pharmacia). In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Hyde et al. 2007).

Results

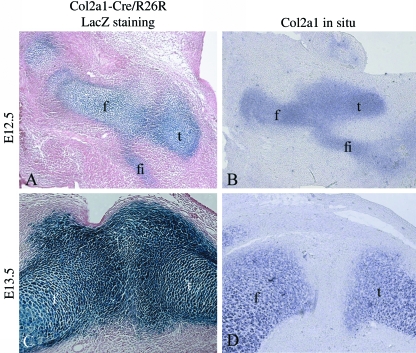

Cessation of Col2a1 expression and not cellular invasion occurs during interzone formation

To determine if cells invade into the presumptive joint during interzone formation, E12.5 and E13.5 Col2a1-Cre/R26Rmouse knee sections were prepared and the pattern of β-galactosidase activity (indicative of previous collagen II gene expression) was compared with the pattern of current Col2a1 expression in equivalent wild-type sections. At E12.5 a continuous Y-shaped anlagen was observed when analysing both β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 2A) and the presence of the Col2a1 transcript (Fig. 2B). By E13.5, the interzone had formed and most cells in this region no longer expressed Col2a1 (Fig. 2D). However, cells in this region remained positive for β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 2C) clearly indicating that at this stage of development, all of the cells in the interzone were derived from cells that had expressed Col2a1. Had cells outside the original anlagen invaded into the joint to form the interzone, they would not have stained for β-galactosidase.

Fig. 2.

A comparison of Col2a1expression history with current Col2a1 expression. Sagittal sections through the knees of E12.5 and E13.5 Col2a1-Cre/R26R mouse embryos. The blue staining indicates β-galactosidase activity and occurs in cells that have expressed Col2a1(A + C). In situ hybridization detecting current Col2a1expression in comparable E12.5 and E13.5 murine knee sections (B + D). Femur (f), tibia (t), fibula (fi).

Col2a1-negative cells invade into the developing joint between E13.5 and E14.5 to form the lateral meniscus

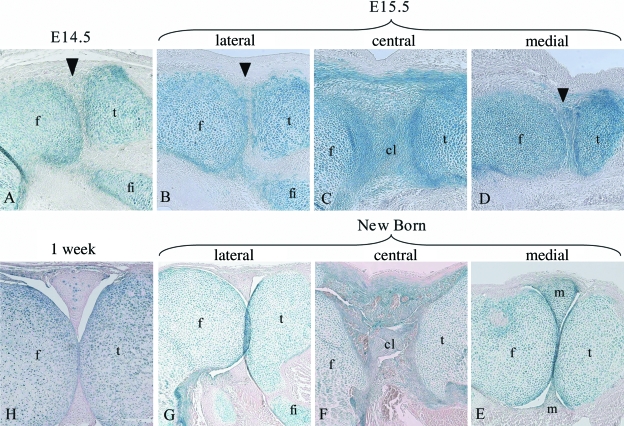

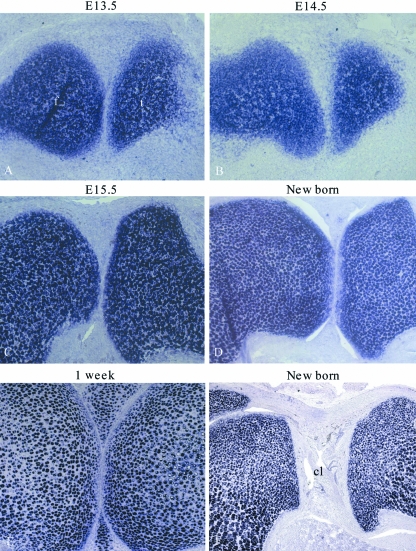

To determine if cells migrate from outside the β-galactosidase-positive anlagen into the developing joint after E13.5 when the interzone has formed, sagittal sections through Col2a1-Cre/R26R mouse knees were prepared at E14.5, E15.5, new born and 1-week age points. At E14.5 β-galactosidase-negative cells had appeared in the developing joint (Fig. 3A); these cells must have originated from outside of the original anlagen due to their lack of β-galactosidase staining. By E15.5 it was apparent that these cells were forming the lateral meniscus (the fibula joins the tibia at the lateral side of the joint; the presence of the fibula in the sagittal section therefore identifies the lateral meniscus) (Fig. 3B). However, the medial meniscus and the cruciate ligament were forming from β-galactosidase-positive cells (Fig. 3C,D). By birth, cavitation of the joint had occurred and the medial meniscus and ligament were again positive for β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 3E,F). The lateral meniscus did not contain β-galactosidase-positive cells but was directly adjacent to the positive articular and epiphyseal cartilage, suggesting that the lack of staining was unlikely to be due to low β-galactosidase-substrate penetration into this area of the joint (Fig. 3G). The pattern of β-galactosidase staining showed that the medial meniscus and cruciate ligament has developed from cells that have previously expressed Col2a1, but that the lateral meniscus has formed from cells that had not. By 1 week of age the lateral meniscus had some β-galactosidase-positive cells included within it (Fig. 3H), indicating that these meniscal cells had begun to express Col2a1 (and hence the Col2a1-driven cre recombinase).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of Col2a1expression history in E14.5, E15.5, new born and 1-week murine knee joints. A sagittal section through the lateral meniscus of an E14.5 Col2a1-Cre/R26R knee (A). Sagittal sections through E15.5 (B–D) and new born Col2a1-Cre/R26R (E–G) murine knees: through the lateral meniscus (B + G), through the developing cruciate ligament (C + F) and through the medial meniscus (D + E). A section through the lateral meniscus of a 1-week Col2a1-Cre/R26R knee (H). Blue staining indicates β-galactosidase activity and occurs in cells that have expressed Col2a1. Arrowheads indicate the developing meniscus. Femur (f), tibia (t), fibula (fi), cruciate ligament (cl), meniscus (m).

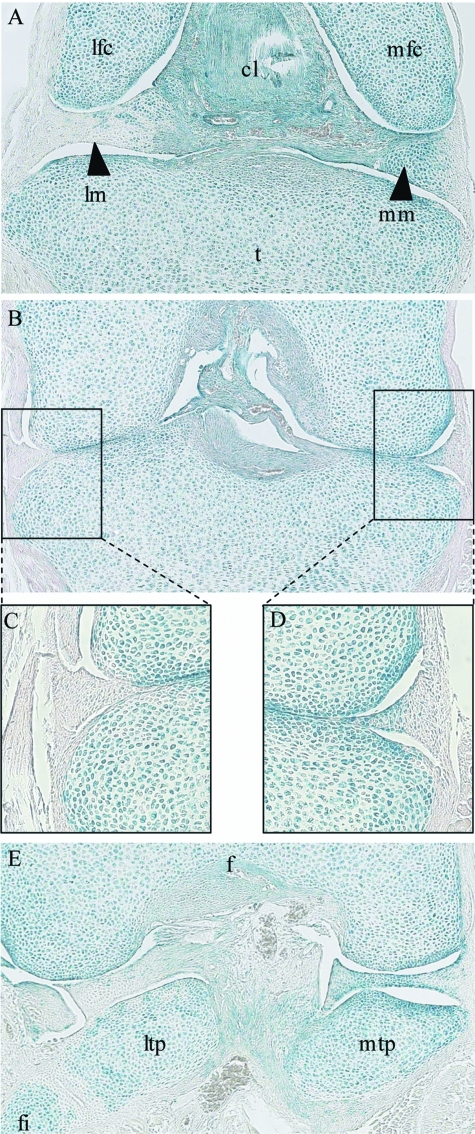

To confirm the conclusions made from sagittal sections through the joint, and to get a better 3-dimensional understanding of joint formation, coronal sections through new born Col2a1-Cre/R26R knees were prepared and counterstained. Coronal sections are perpendicular to sagittal sections and therefore generate a series along the anterior/posterior axis of the joint (see Fig. 1). In these coronal sections both the lateral and medial menisci are visible on the same section. As coronal sections were cut through the anterior of the joint, the meniscus and cruciate ligament completely separated the two femoral condyles from the tibia. However, the medial meniscus consisted largely of β-galactosidase-positive cells and the lateral of mainly β-galactosidase-negative cells (Fig. 4A). Towards the centre of the joint the femoral and tibial condyles come into contact and the meniscus appears as a wedge shape at the periphery of the joint. Consistent with previous observations, the lateral meniscus was β-galactosidase negative and the medial positive (Fig. 4B–D). However, it should be noted that it was only the inner part of the medial meniscus that was β-galactosidase-positive, the outer region was negative (Fig. 4D). Towards the posterior of the joint the meniscus again separated the tibia and femur, and the medial meniscus was β-galactosidase-positive and the lateral negative (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Coronal sections through a new born Col2a1-Cre/R26R mouse knee. A section through the anterior of the knee (A). A section through the middle of the knee where the two femoral condyles are in contact with the tibial plateau (B), magnifications of the lateral (C) and medial (D) menisci. A section through the posterior of the knee (E). Blue staining indicates β-galactosidase activity and occurs in cells that have expressed Col2a1. Tibia (t), cruciate ligament (cl), lateral meniscus (lm), medial meniscus (mm), lateral femoral condyle (lfc), medial femoral condyle (mfc), femur (f), lateral tibial plateau (ltp) and medial tibial plateau (mtp), fibula (fi).

The meniscus does not express Col2a1 between E13.5 and 1 week of age

Up to 1 week of age, the lateral and outer medial menisci are β-galactosidase negative in the Col2a1 lineage tracing analysis (Figs 3 and 4). These cells have therefore never expressed Col2a1 and must have invaded into the developing joint from outside of the original Col2a1-positive anlagen. However, the ligament and inner medial meniscus have developed from cells that have expressed Col2a1. To determine the expression pattern of Col2a1 in these tissues during development, in situ hybridization was performed. The medial meniscus did not express Col2a1 between E13.5 and birth (Fig. 5A–D). However, at 1 week of age the meniscus had turned on expression of the gene (Fig. 5E). By in situ hybridization, the cruciate ligament did not express Col2a1 during development or upon joint maturity (Fig. 5F). Nevertheless, the presence of β-galactosidase activity in the ligament and medial meniscus demonstrates that these tissues have formed from cells in the original anlagen that had expressed Col2a1prior to interzone formation at E13.5. It should be noted that although the lateral and outer medial menisci form from cells that are β-galactosidase negative and that have migrated into the developing joint, many of these cells subsequently express collagen II from around 1 week of age and subsequently will become β-galactosidase positive in the Col2a1-Cre/R26Rmouse (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Col2a1 expression in the developing medial meniscus. In situhybridization against Col2a1on E13.5 (A), E14.5 (B), E15.5 (C), new born (D), and 1-week-old (E) sagittal knee sections through the medial meniscus. In situhybridization against Col2a1 on a new born sagittal knee section through the cruciate ligament (F). Femur (f), tibia (t) and cruciate ligament (cl).

Discussion

During skeletal development the first overt sign of joint development is the formation of an interzone within the cartilaginous anlagen. Previous studies have shown that cells participating in interzone formation appear to switch from collagen II to collagen I expression as they flatten. This change in gene expression pattern could be accounted for either by resident cells changing their expression as they flatten (Craig et al. 1987; Nalin et al. 1995; Archer et al. 2003) or by cells migrating into the joint to form the flattened cell layer of the interzone. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we compared E13.5 Col2a1-Cre/R26Rknee joint sections with the actual expression of Col2a1 in equivalent sections (Fig. 2). This comparison demonstrated that although many cells in the presumptive joint interzone region did not express Col2a1 at E13.5, all the cells in this zone were derived from resident anlagen cells that had previously expressed collagen II, as indicated by their β-galactosidase activity. The interzone could not therefore have formed as the result of a recent migration of cells into the presumptive joint from outside the anlagen because these cells would have been negative for β-galactosidase activity.

To determine the origin of cells in the developing knee joint at subsequent stages of development, sagittal sections through E14.5, E15.5, new born and 1-week-old Col2a1-Cre/R26R knees were analysed. As development progressed it was clear that the medial meniscus and cruciate ligament were forming from β-galactosidase-positive cells that had therefore expressed Col2a1 at some point in their lineage. However, the cells that formed the lateral meniscus were β-galactosidase negative in all ages examined up to 1 week postnatally, with the exception of a few β-galactosidase-positive cells that appeared at 1 week of age (Fig. 3H). The appearance of cells negative for β-galactosidase activity at E14.5 means that these cells must have migrated into the developing knee joint from outside of the original Col2a1-positive anlagen during the preceding 24 h (Figs 2C and 3A). To confirm this evaluation, coronal sections were cut through new born Col2a1-Cre/R26R knees. Consistent with the interpretation of the sagittal section data, the lateral meniscus was β-galactosidase negative and the medial positive. Not only was the lateral meniscus β-galactosidase negative in the centre of the joint where the femur and tibia meet, but also at the anterior and posterior of the joint where the meniscus connects with the cruciate ligament (Fig. 4A,E). Furthermore, from coronal sections it was apparent that although the inner part of the medial meniscus was β-galactosidase positive, the outer part was negative (Fig. 4D), demonstrating that the outer medial meniscal cells also developed from cells that are not derived from the original Col2a1-positive anlagen. In addition to the knee joint, interphalangeal joints from the Col2a1-Cre/R26R mice were examined. However, all cells were positive for β-galactosidase in these joints (data not shown), indicating that the cellular invasion into the joint seen in the knee may be a specialized process associated with meniscus formation.

As the cells of the lateral meniscus were negative for β-galactosidase activity up to 1 week of age, it is known that they have never expressed the Col2a1 gene. The cells of the cruciate ligament and inner medial meniscus were positive for β-galactosidase activity, demonstrating that at some point they have expressed the Col2a1 gene. However, by in situ hybridization, neither the medial meniscus nor the cruciate ligament cells expressed the Col2a1 gene between E13.5 and birth, and therefore these cells must have acquired their β-galactosidase expression prior to E13.5. These lineage tracing data clearly indicate that the cruciate ligament and medial meniscus develop from the cells of the central interzone that expressed Col2a1 and were β-galactosidase-positive at E12.5 but that had ceased expression of Col2a1 by E13.5 (Fig. 2). The ligament cells do not subsequently express Col2a1 (Fig. 5F), whereas the meniscal cells do, approximately 1 week postnatally (Fig. 5C,D). In the case of the inner medial meniscal cells, this is a re-expression of Col2a1, whereas for the rest of the meniscal cells this represents the first time they have expressed the gene.

Previously, the distinction between the inner and outer meniscal areas has been due to the heterogeneity of the tissue. The inner part of the menisci is more cartilage-like and expresses higher levels of collagen II, whereas the outer part is more fibrous and expresses more collagen I (Kambic & McDevitt, 2005). The two areas have further differences in gene expression, including the presence of aggrecan in the inner region and expression of the matrix-metalloproteinases 2 and 3 in the outer region (Upton et al. 2006). In addition, it was observed many years ago that the outer meniscus, but not the inner meniscus, is vascularized. The vascularization of the outer region has long been thought to be the reason why the outer region spontaneously repairs, unlike the avascular inner region. However, it has recently been suggested that the difference in repair potential may also be due to the differing cellular composition of the meniscus (Kobayashi et al. 2004; Mauck et al. 2007). This was proposed after it was observed that the different regions of the meniscus retain differing healing potentials in an organ culture system, when no active blood supply is present (Kobayashi et al. 2004). Furthermore, it has been shown that meniscal fibrochondrocytes have differing multi-lineage potential depending on the region of the meniscus they have been isolated from, with those from the outer region being the most plastic (Mauck et al. 2007).

The data presented here demonstrate that the meniscus develops from a combination of cells of different origins, some from the Col2a1-expressing anlagen and some that invade into the developing joint from outside the anlagen. These findings may explain some of the differences in gene expression, cellular plasticity and repair potential of the various meniscal regions. That the outer meniscal cells are less chondrogenic is consistent with their developmental origin from cell lineages that arose outside the original anlagen and subsequently migrated into the forming joint. The distinct developmental origin may also explain why the outer meniscal cells retain greater plasticity than their inner meniscal equivalents. However, most studies which compare the properties of the outer and inner meniscus pool cells from both the lateral and medial menisci. It would be interesting to test whether the cells from the inner medial and lateral meniscus (which develop from the Col2a1-positive anlagen and Col2a1-negative cells, respectively) retain distinct properties due to their differing origins.

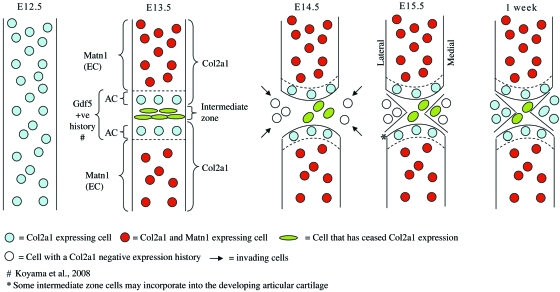

We have previously demonstrated that articular chondrocytes are present when the interzone is first morphologically detectable at E13.5 (Hyde et al. 2007). They are distinguishable from epiphyseal chondrocytes based on the differential expression of extracellular matrix protein matrilin-1 (encoded on the Matn1 gene), which is expressed by transient epiphyseal chondrocytes but not by articular chondrocytes. A combination of the matrilin-1 and Gdf5 (Koyama et al. 2008) lineage tracing and the data presented in this paper, allows the presentation of a refined model of knee formation (Fig. 6). In this model of knee development, articular chondrocytes become distinguishable – due to Col2a1 expression but not Matn1 expression – as the central intermediate zone cells cease Col2a1 expression at E13.5. The cells of the central intermediate zone go on to form the cruciate ligament and inner medial meniscus, which both have a Col2a1-positive expression history but no longer express the gene. At E14.5, post-interzone formation, cells from outside the anlagen and therefore negative for β-galactosidase activity in the Col2a1-Cre/R26R mouse, invade into the developing knee, and form the lateral and outer medial meniscus. The meniscal cells begin to express the Col2a1 gene postnatally, but the ligament cells do not.

Fig. 6.

A refined model of knee development in the mouse. Between E12.5 and E13.5 the Col2a1-positive anlagen is interrupted when the intermediate zone cells turn off expression of Col2a1. At the same time, epiphyseal chondrocytes begin to express Matn1, distinguishing them from articular chondrocytes and other skeletal tissues. By E14.5, cells with a Col2a1-negative expression history have invaded the joint and form the lateral and outer medial meniscus. The cells which have ceased Col2a1 expression form the cruciate ligament and the inner medial meniscus. By 1 week a mature joint is almost formed and the meniscal cells begin to express or re-express Col2a1. The cells of the cruciate ligament which previously turned off Col2a1 expression do not turn it back on. Articular chondrocytes (AC), epiphyseal chondrocytes (EC).

Here we propose that the intermediate zone cells, which have ceased Col2a1 expression, form the cruciate ligament and inner medial meniscus of the knee. However, this raises the question of what happens to these cells in joints that do not possess these tissues. In the knee, it is possible that some of the intermediate zone cells incorporate into the developing articular cartilage, forming the more superficial zones, and this may be the predominant destination of intermediate zone cells in joints other than the knee.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust and the Arthritis Research Campaign.

References

- Archer CW, Dowthwaite GP, Francis-West P. Development of synovial joints. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2003;69:144–155. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig FM, Bentley G, Archer CW. The spatial and temporal pattern of collagens I and II and keratan sulphate in the developing chick metatarsophalangeal joint. Development. 1987;99:383–391. doi: 10.1242/dev.99.3.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duthon VB, Barea C, Abrassart S, Fasel JH, Fritschy D, Menetrey J. Anatomy of the anterior cruciate ligament. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:204–213. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0679-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis-West PH, Abdelfattah A, Chen P, et al. Mechanisms of GDF-5 action during skeletal development. Development. 1999;126:1305–1315. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CB. Ligament structure, physiology and function. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2004;4:199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldring MB, Goldring SR. Osteoarthritis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:626–634. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde G, Dover S, Aszodi A, Wallis GA, Boot-Handford RP. Lineage tracing using matrilin-1 gene expression reveals that articular chondrocytes exist as the joint interzone forms. Dev Biol. 2007;304:825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambic HE, McDevitt CA. Spatial organization of types I and II collagen in the canine meniscus. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IM, Redman SN, Williams R, Dowthwaite GP, Oldfield SF, Archer CW. The development of synovial joints. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;79:1–36. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)79001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Fujimoto E, Deie M, Sumen Y, Ikuta Y, Ochi M. Regional differences in the healing potential of the meniscus – an organ culture model to eliminate the influence of microvasculature and the synovium. Knee. 2004;11:271–8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2002.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama E, Shibukawa Y, Nagayama M, et al. A distinct cohort of progenitor cells participates in synovial joint and articular cartilage formation during mouse limb skeletogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;316:62–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH. Improved reporter strain for monitoring Cre recombinase-mediated DNA excisions in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5037–5042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauck RL, Martinez-Diaz GJ, Yuan X, Tuan RS. Regional multilineage differentiation potential of meniscal fibrochondrocytes: implications for meniscus repair. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2007;290:48–58. doi: 10.1002/ar.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalin AM, Greenlee TK, Jr, Sandell LJ. Collagen gene expression during development of avian synovial joints: transient expression of types II and XI collagen genes in the joint capsule. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:352–362. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici M, Koyama E, Shibukawa Y, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of synovial joint and articular cartilage formation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1068:74–86. doi: 10.1196/annals.1346.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rath E, Richmond JC. The menisci: basic science and advances in treatment. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:252–257. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.34.4.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rountree RB, Schoor M, Chen H, et al. BMP receptor signaling is required for postnatal maintenance of articular cartilage. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e355. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai K, Hiripi L, Glumoff V, et al. Stage- and tissue-specific expression of a Col2a1-Cre fusion gene in transgenic mice. Matrix Biol. 2001;19:761–767. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00122-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm EE, Kingsley DM. Joint patterning defects caused by single and double mutations in members of the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family. Development. 1996;122:3969–3979. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upton ML, Chen J, Setton LA. Region-specific constitutive gene expression in the adult porcine meniscus. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:1562–1570. doi: 10.1002/jor.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]