Abstract

The best characterized estrogen receptors that are responsible for membrane initiated estradiol signaling are the classic estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and estrogen receptor-β (ERβ). When in the nucleus, these proteins are estradiol activated transcription factors, but when trafficked to the cell membrane, ERα and ERβ rapidly activate protein kinase pathways, alter membrane electrical properties, modulate ion flux and can mediate long-term effects through gene expression. To initiate cell signaling, membrane ERs transactivate metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) to stimulate Gq signaling through pathways using PKC and calcium. In this review, we will discuss the interaction of membrane ERα with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a (mGluR1a) to initiate rapid estradiol cell signaling and its critical roles in female reproduction – sexual behavior and estrogen positive feedback of the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. Although long considered to be regulated by long term actions of estradiol on gene transcription, new results indicate that membrane estradiol cell signaling is vital for full display of sexual receptivity. Similarly, the source of preovulatory progesterone necessary for initiating the LH surge is hypothalamic astrocytes. Estradiol rapidly amplifies progesterone synthesis through the release of intracellular calcium stores. The ERα-mGluR1a interaction is necessary for critical calcium flux. These two examples provide support for the hypothesis that membrane ERs are not themselves G protein receptors, rather they use mGluRs to signal.

Keywords: estradiol, calcium signaling, lordosis, neurosteroids, estrogen positive feedback

Introduction

The best characterized estrogen receptors are estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and estrogen receptor-β (ERβ), which were cloned in the 1980’s and 1990’s (1, 2). These molecules were thought to act exclusively as ligand-activated transcription factors whose primary function was modulation of gene expression. In the brain, the actions of steroids were also considered to mediate only long-term effects that required transcriptional regulation. Some of these actions were said to act during the perinatal period to organize the brain and then again during adulthood to activate estrogen-sensitive circuits (3). The most obvious effects of estrogens in the brain are those that regulate reproduction: sexual behaviors and the secretion of gonadotropins. These actions had long time-courses and were blocked by transcription inhibitors (e.g., actinomycin D) or translation inhibitors (e.g., cycloheximide; (4–6)). There is no doubt that such long-term estrogen actions are vital for driving reproduction, but more recent evidence suggests that along with gene regulation, estrogen also mediates more rapid cellular effects. Although rapid actions of estradiol have been observed for decades, only more recently have these actions been accepted (7–12). These membrane estrogen receptors (ERs) rapidly activate protein kinase pathways, alter membrane electrical properties and modulate ion flux (13–18), but suggestions about their physiological roles, especially in reproduction, have only recently been elucidated (12, 19–22).

In addition to the rapid timeframe of some responses to estradiol, membrane-initiated action could be mimicked with membrane-constrained estradiol conjugates. For example: 17β-estradiol 6-(O-carboxymethyl)oxime-bovine serum albumin (E2-6-BSA), 17β-estradiol-horseradish peroxidase (E2-HRP) and 17β-estradiol-biotin are all compounds that prevent estradiol from entering cells due to the large size and charge properties of the conjugated molecules, and all elicit rapid cell signaling events (17, 20, 23–25). Similarly, dialysis of estradiol into the interior of neurons did not mimic the rapid effects of estradiol even though intracellular ERs were activated (13). Finally, overexpression of ERα and ERβ were shown to be targeted to the membrane in ER naïve cells, demonstrating that the same proteins could function as membrane and nuclear receptors (26). Over the ensuing years the preponderance of evidence indicates that ERα and ERβ are the membrane receptors that activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), extracellular regulated kinase (ERK) pathways and cytoplasmic free calcium ([Ca2+]i) flux (reviewed in (10–12)).

This is not to say the question of the membrane ER has been solved. In hippocampal neurons from ERα knockout mice, estradiol induced membrane currents that were not inhibited by ICI 182, 780, suggesting a mechanism independent from the classical ER (27). Several other candidates have been proposed as membrane ERs based on sequence homology or estrogen binding: most notably ER-X, STX-binding protein and GPR30 (28–30). Thus, there may be a cornucopia of ERs or our definition of an ER is too lax. Perhaps what is needed is a minimum definition of an ER. Exactly what that those criteria should include is open to debate. To initiate the discussion, we propose that an ER should include stereospecificity and common antagonism. For the definition of an ER, we propose that an ER be antagonized by ICI 182,780, and respond to 17β-but not 17α-estradiol. If the definition were strictly enforced, ER-X would be excluded since it is not antagonized by ICI 182,780 and is not stereospecific. On the other hand its sequence homology with classic ERα and ERβ (28) make the ER-X situation similar to the opioid receptor-like protein (ORL-1), which is has a sequence homology with opioid receptors but is not antagonized by naloxone, the sine qua non of an opioid receptor (31, 32). GPR30 is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) with seven transmembrane hydrophobic domains through which estradiol induces Erk-1/-2 activation (33). ICI 182,780 binds to GPR30, but in some assays it does not antagonize the receptor ((34); but see (30)). GRP30 appears to be localized to Golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum membranes, but not the cell membrane and thus, represents a novel intracellular ER (35). Finally, an intriguing putative ER is activated by the diphenylacrylamide, STX (36). The STX receptor attenuates the outward (GIRK) current induced by the GABAB receptor agonist baclofen, mimicking estradiol (29). The STX-activity remains in ERα−/− and ERβ −/− double knockout animals where STX is antagonized by ICI 182, 780. The STX-binding protein has not been cloned nor has its structure been determined.

ERα and ERβ are present in the membrane (17), but these molecules are not seven membrane-pass, GPCR proteins. To explain how ERα and ERβ activation initiates G protein signaling two hypotheses have been proposed. The first is that ERα and ERβ are GPCRs. The second hypothesis is that membrane ERα interacts with another receptor that is a GPCR. Estradiol binding allows ER transactivation of a GPCR that in turn initiates cell signaling. Both in the periphery and in the nervous system, membrane ERα and ERβ have been shown to interact with other receptors to initiate cell signaling. The topic is well-reviewed by Mermelstein et al. in the current issue. Briefly, in the nervous system, membrane ERα and ERβ, associate with metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs; (20, 37–39)). In the present review, we discuss the effects of the ERα and mGluR1a interaction on female sexual behavior and estrogen positive feedback.

Sexual Receptivity

Integration of relevant interoceptive and exteroceptive information leading to the sexually receptive behaviors involves an extensive limbic and hypothalamic circuit (for reviews see (40, 41)). Part of this lordosis regulating circuit is the projection from the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus to the medial preoptic nucleus (MPN). Estradiol activates microcircuits in the ARH that lead to the release of β-endorphin (β-END) in the MPN. Briefly, when estradiol activates ERα in the arcuate nucleus, neuropeptide Y (NPY) is released stimulating NPY-Y1 receptors on β-END neurons that project to the MPN (42–44). The release of β-END in the MPN activates μ-opioid receptors (MORs), which modulate the display of lordosis behavior, a measure of female sexual receptivity. As with other membrane receptors, following activation the MOR is internalized (45). Internalization is a process involved in desensitization of receptors and has been used to track the activation of specific circuits by estradiol (20, 42, 44). In this case, activation of the MOR and its internalization occur rapidly (within 30 mins of estradiol treatment) and is correlated with the concurrent inhibition of lordosis. This transient, estradiol-induced inhibition is necessary for full sexual receptivity measured 30 hours after treatment. For example, pharmacologic blockade of MOR activation/internalization with MOR antagonists such as H-d-Phe-Cys-Tyr-d-Trp-Orn-Thr-Pen-Thr-NH2 (CTOP) or removing the MOR, as in MOR-KO mice, results in a greatly diminished lordosis response even in the presence of estradiol (42, 46). The time course of estradiol activation of the arcuate nucleus and subsequently the MPN suggests that these actions are mediated by cell signaling events and not by transcription-translational regulation.

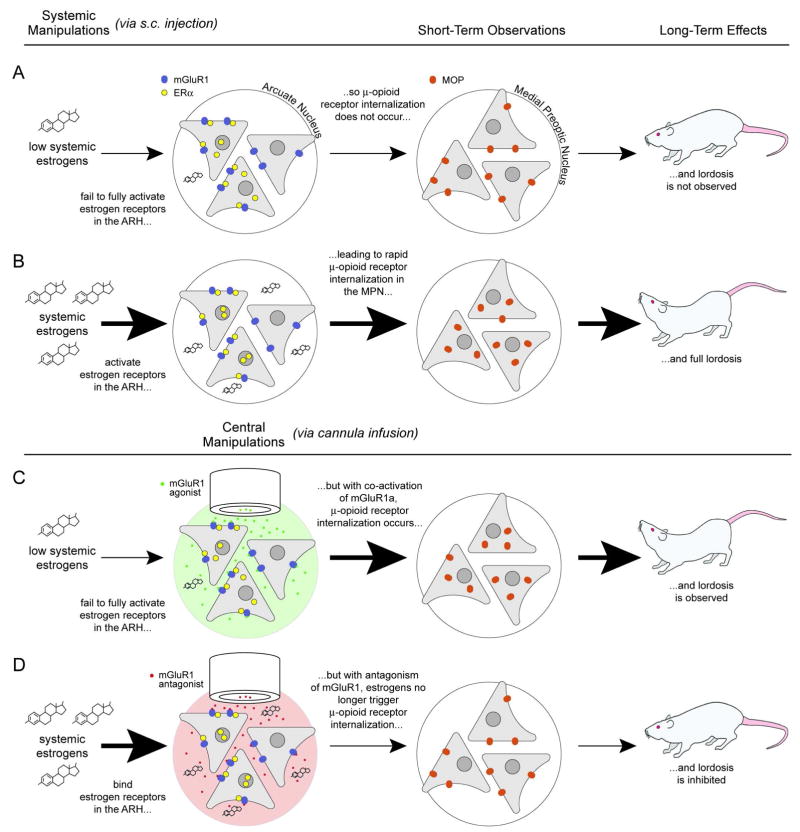

Microinfusion of estradiol-biotin into the arcuate nucleus to stimulate only membrane associated ERs results in both an increase in phosphorylated CREB (pCREB) and an increase in MOR internalization (20). Taken together, this implies that a membrane associated ER has rapid actions in the ARH that are likely mediated by a G-protein. ERα and mGluR1a are co-expressed in a population of arcuate neurons (20) and these molecules can interact in the membrane as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation using membrane fractions obtained from the arcuate nucleus. We showed that membrane initiated ERα-mediated estradiol regulation of MOR internalization and lordosis behavior was dependent on mGluR1a. Antagonizing mGluR1 with LY367385 in the arcuate nucleus prevented the estradiol induced MOR internalization and the lordosis behavior. If mGluR1a was needed for the estradiol action, activating the glutamate receptor should mimic estradiol. The selective mGluR1a agonist (S)-3, 5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) infused into the arcuate nucleus induced the activation/internalization of MOR in the medial preoptic nucleus. Rats pretreated with a dose of estradiol too low to initiate lordosis behavior alone and then supplemented with an intra-arcuate nucleus infusion of DHPG were sexually receptive. This result indicated that activation of mGluR1a was a necessary downstream event in the estradiol activation of the arcuate to MPN projection and the regulation of lordosis behavior (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. ER/mGluR signaling in the arcuate nucleus (ARH) – medial preoptic nucleus (MPN) circuit regulates female sexual receptivity. Low estradiol levels do not activate the circuit and the rat is not sexually receptive (first row). As circulating levels of estradiol increase, they stimulate ERα in the ARH, which induce the release of β-endorphin in the MPN activating and internalizing MORs, producing lordosis (second row). If mGluR1a are activated in the presence of low circulating estradiol levels, the ARH-MPN projection is activated: MOR is activated/internalized leading to lordosis behavior (third row). Conversely, antagonizing mGluR1a prevents the estradiol activation of the ARH-MPN circuit: MOR is not activated/internalized and lordosis is attenuated (fourth row). (From (12)).

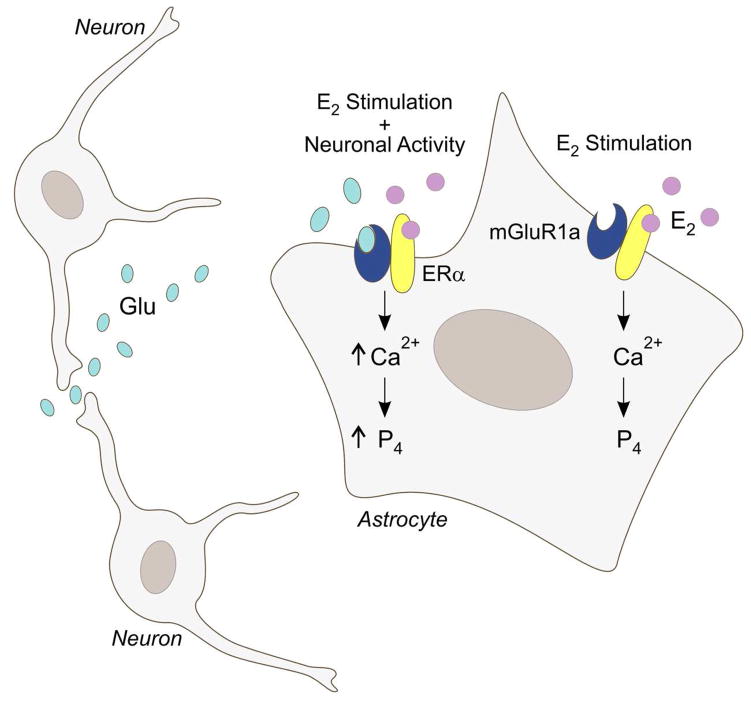

Figure 1B. A model of estradiol signaling in astrocytes and the mechanism regulating the synthesis of neuroprogesterone. Estradiol (E2), typically of ovarian origin, binds to membrane ERα and activates the mGluR1a. This increases levels of free cytoplasmic calcium (Ca2+) through the inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptor-mediated release of intracellular stores of calcium. Elevated levels of [Ca2+]i are needed for neuroprogesterone (P4) synthesis in astrocytes. When both mGluR1a and ERα are simultaneously stimulated, the resulting [Ca2+]i flux is significantly increased. This suggests that, in vivo, neural activity modulates the astrocytic response to E2: when local neural activity releases glutamate (Glu), the synthesis of progesterone is augmented. (Modified from (12)).

More recent work has begun to uncover the cell signaling activated by the ERα-mGluR1 interaction. It has been well-known that estradiol treatment can result in the activation of several different protein kinases. Using E2-6-BSA, both protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) been shown to be necessary components for rapid estradiol signaling in a number of systems (19, 47–50). Both PKC and PKA have previously been associated with estradiol’s rapid stimulation of the lordosis reflex (16, 19, 51). Also mGluR1a is primarily coupled to members of the Gq family resulting in activation of PLC and DAG, suggesting the activation of a PKC (51–53).

While the mechanisms responsible for mERα-mGluR1a mediated activation of lordosis behavior are likely to involve many players, an important role for PKC signaling has recently been elucidated (16, 38). PKCs are a family of serine/threonine kinases that have a conserved catalytic ATP-binding site and kinase domain as well as a conserved N-terminal domain for membrane targeting. The PKCs are divided into three classes based upon their method of activation: (1) conventional PKCs (α, β and γ) which require diacylglycerol (DAG) or phosphotidylserine and calcium for activation; (2) novel PKCs (δ, ε, η, μ and θ) which require only DAG or phorbol esters; and (3) atypical PKCs (ι, ζ and λ) which depend on neither DAG nor calcium for their activation although they may be activated by phosphotidylserine, inositol lipids or phosphatidic acid (54). A protein microarray targeted at cell signaling pathways, identified a number of activated signaling molecules including PKA and PKCθ. The increased phosphorylation of PKA was not confirmed by western blots of estradiol treated arcuate nucleus, but phosphoPKCθ upregulation was confirmed (38). In our experiments, the ARH-MPN portion of the limbic-hypothalamic lordosis regulating circuit was not modulated by activation of PKA. Pharmacologically antagonizing PKA activation with [N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinoline sulfonamide (H-89) did not prevent estradiol-induced lordosis, even at very high doses. We cannot conclude, however, that PKA does not regulate other parts of the CNS that modulate lordosis, such as the periaquaductial gray or ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (55) or in other estradiol activated reproductive functions in the hypothalamus (51, 56–61).

Bisindolymaleimide (BIS), a blocker of PKC activation, injected into the arcuate nucleus attenuated the estradiol-induced MOR internalization/activation and lordosis. These results were similar to those seen after antagonizing of GluR1a in the arcuate nucleus. Blocking PKC prevented MOR internalization induced by the mGluR1a agonist DHPG, suggesting that PKC activation was downstream of the activation of mGluR1a. To further test this idea, phorbol 12, 13-dibutyrate (PDBu), an activator of PKC, was used to internalize MOR in the absence of estradiol. Not only did PDBu cause internalization of MOR, but it also facilitated lordosis when the rats were treated with a subthreshold dose of estradiol. These studies along with the pathway array results strongly implicate PKCθ activation as a critical step in estradiol membrane initiated cell signaling regulating sexual receptivity.

Both nuclear initiated and membrane initiated actions of estradiol described here are vital for activation of lordosis behavior. Transcription may be activated by nuclear receptors or by membrane to nuclear signaling cascades (20, 37). The available evidence is that membrane initiated signaling is not sufficient by itself to induce sexual receptivity. Membrane ERa potentiate transcriptional events that regulate lordosis (19, 20). In spite of this fact, it is clear that the internalization of MOR in the MPN critically depends upon the interaction of ERa and mGluR1 at the membrane and that this interaction allows the phosphorylation and activation of PKC, all of which is necessary for the full display of lordosis behavior (20, 38, 42, 46). Estradiol treatment always precedes lordosis behavior by 30 hours and antagonizing mGluR1a or PKC only at the time of estradiol treatment attenuates lordosis behavior. This implies that these are rapid, transient actions of estradiol. Moreover, the membrane constrained construct estradiol-biotin, induces MOR internalization seen when free estradiol is systemically injected (20).

Estrogen Positive Feedback and Neurosteroids

Ovulation is a key event in mammalian reproduction. On the afternoon of proestrus, rising levels of estradiol from maturing ovarian follicles activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis to release a surge of luteinizing hormone (LH). Unlike the negative feedback effects of estradiol during other times of the estrous cycle, spiking levels of estradiol become stimulator. This is known as estrogen positive feedback (62). It is well established that an estrogen positive feedback mechanism is essential for induction of the LH surge that leads to ovulation and subsequent luteinization of the postovulatory ovarian follicle. In addition to elevated levels of estradiol, a pre-ovulatory rise in progesterone and progesterone receptors has been shown to be essential for the LH surge (63–68). Specifically, both transcription and activation of progesterone receptors in the hypothalamus is an obligatory event in the stimulation of the GnRH and LH surges in estradiol-primed, ovariectomized (OVX) rats (68). Furthermore, treatment with trilostane, a blocker of the enzyme 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD) that catalyzes the conversion of pregnenolone to progesterone, inhibits the LH surge, indicating that progesterone synthesis is critical for estrogen-induced positive feedback in an OVX and adrenalectomized (ADX) rats (69). Therefore, a pre-ovulatory increase in both progesterone and estradiol as well as synthesis and activation of PRs are all essential for inducing the LH surge.

Very little progesterone is detectable in the systemic circulation prior to the LH surge, indicating that pre-ovulatory progesterone needed for the LH surge may not be synthesized peripherally (70–72), but produced locally within the hypothalamus. Consistent with such an idea, ovariectomized/adrenalectomized rats injected with 17β-estradiol have been shown to produce a robust LH surge and have elevated levels of hypothalamic progesterone levels (69, 73). The importance of de novo hypothalamic progesterone synthesis was further demonstrated in gonadally intact rats. These rats had normal four-day estrous cycles, but blocking steroidogenesis in the hypothalamus with aminoglutethemide (AGT), a P450scc enzyme inhibitor, on the morning of proestrus prevented the LH surge, ovulation and luteinization (74). In these rats, peripheral steroidogenesis was not disrupted since estradiol levels in the AGT treated rats were the same as cycling controls. After several days, AGT treated rats resumed their cycles, indicating that the treatment had not damaged the estrogen positive mechanism. In hypothalamus, estradiol stimulated progesterone synthesis in astrocytes (21, 75). The mechanism of estradiol regulation of progesterone synthesis was examined using primary cultures of post-pubertal hypothalamic astrocytes.

In vitro, estradiol increases free cytoplasmic calcium levels ([Ca2+]i;; (17, 21)). The rapid estradiol action (< 30 sec) is mediated by a membrane ER, a conclusion based on results with the universal ER antagonist ICI182,780 and membrane-constrained E2-6-BSA that induced a statistically similar [Ca2+]i flux compared with estradiol. Subnanomolar doses of estradiol (ED50 = 0.15 nM) increase [Ca2+]i flux, indicating that the mER responds to physiological levels of estradiol, which are achieved during the proestrus surge in rats (76). ERα and ERβ are found in astrocytes (17, 77–79) and in astrocyte membrane fractions (17). Removing calcium from the media did not alter the estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux indicating the release of intracellular stores. Using a series of pharmacological agents, this was confirmed: membrane-initiated, estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux activated the phospholipase C/inositol trisphosphate (PLC/IP3) pathway leading to the release of IP3 receptor sensitive calcium stores (80). To demonstrate the relationship between the rapid estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux and the estradiol amplification of progesterone synthesis, thapsigargin was used to release IP3 receptor sensitive internal stores of calcium (21). Thapsigargin, a Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor that initially induces a massive release of intracellular calcium, was as effective as estradiol at inducing the de novo synthesis of progesterone (neuroprogesterone) in hypothalamic astrocytes cultured from the post-pubertal females, suggesting that the estradiol-induced progesterone synthesis involves rapid increases in [Ca2+]i flux (21).

Several lines of evidence indicate that the membrane-initiated estradiol actions utilize the same mechanism in astrocytes as does ERα in neurons (20, 37, 76). First, the selective ERα agonist, propylpyrazole triole (PPT), induced a robust [Ca2+]i flux, but the selective ERβ agonist, diarylpropionitrile (DPN), did not, supporting a role for ERα in the membrane initiation of estradiol signaling. Second, hypothalamic astrocytes express mGluR1a receptors (76). Third, ERα, but not ERβ, co-immunoprecipitates with mGluR1a, suggesting that these two receptors can directly interact. Fourth and finally, the estradiol-induced [Ca2+]i flux was blocked by LY367385, a mGluR1a antagonist, suggesting that ERs localized to the plasma membrane do not interact directly with G proteins; rather, estradiol bound mERs activate mGluRs, which then serve as the intermediate to activate G proteins (20, 37, 81).

In primary cultures of hypothalamic astrocytes, activation of the mGluR1a without estradiol induced a [Ca2+]i flux, but required a high dose of DHPG (100 nM to 50 μM). This result was consistent with our experiments in vivo where high doses of DHPG mimicked the rapid actions of estradiol on MOR internalization/activation and modulation of sexual receptivity. Interestingly, a combined treatment of estradiol and DHPG stimulated a greater [Ca2+]i flux than the maximal response of estradiol or DHPG alone (Fig. 1B), indicating that estradiol not only increases the maximal response of mGluR1a activation, but also lowers the threshold concentration of DHPG required to obtain a maximal response. These results suggest that for a subpopulation of mGluR1a optimal signaling requires an interaction with membrane ERα. One possible explanation is that the ERα associated with mGluR1a is in a conformation that does not allow optimal activation of intracellular signaling pathways. Without the estradiol bound to ERα the associated mGluR1a does not become fully stimulated and signaling is moderated. When estradiol excites the membrane ERα, the conformation change activates the mGluR1a to initiate Gq signaling. This could account for the additive effects of DHPG during estradiol stimulation and the inhibition of estradiol signaling with LY367385.

Intracellular calcium regulation and homeostasis is crucial for regulation of gene expression, development and survival in astrocytes (82). In hypothalamic astrocytes, ERa interaction with mGluR1a has been demonstrated to mediate the [Ca2+]i flux required for neuroprogesterone synthesis and critical for the LH surge and ovulation. Maximal calcium signaling in astrocytes requires both glutamate and estradiol, suggesting that estradiol may act most effectively on astrocytes that are near active glutaminergic nerve terminals. This [Ca2+]i wave can also be propagated between astrocytes (83) to extend the activation over a long distance. Further experiments are needed to define whether mERα-mGluR1a interactions can also stimulate other pathways associated with reproduction, such as DAG, PKA, PKC, CREB, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and steroid acute regulatory protein (StAR). Additionally, experiments with ER knock-out mice are currently underway to confirm the critical role of ERα in the regulation of neuroprogesterone synthesis in astrocytes.

Conclusion

Membrane initiated estradiol signaling regulates rapid cell signaling in at least two physiologically relevant mechanisms that control reproduction: the control of sexual receptivity and estrogen positive feedback regulating the LH surge. While a number of aspects remain to be verified, the general idea is that rapid estradiol signaling requires the transactivation of ERα, trafficked to the cell membrane, with mGluR1a, a GPCR. That the mGluR1a initiates Gq signaling that leads to the release on internal calcium stores in astrocytes and phosphorylation of PKCθ in neurons points to the commonality of this mechanism in nervous tissue and its importance in the physiology of estradiol signaling.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants DA013185 and HD042635. We would like to thank Dr. Galyna Bondar for providing experimental data found in this review.

References

- 1.Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, Krust A, Bornert JM, Argos P, Chambon P. Human oestrogen receptor cDNA: sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature. 1986;320:134–9. doi: 10.1038/320134a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mosselman S, Polman J, Dijkema R. ER beta: identification and characterization of a novel human estrogen receptor. FEBS Lett. 1996;392:49–53. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00782-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arnold AP, Breedlove SM. Organizational and activational effects of sex steroids on brain and behavior: a reanalysis. Horm Behav. 1985;19:469–98. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rainbow TC, Davis PG, McEwen BS. Anisomycin inhibits the activation of sexual behavior by estradiol and progesterone. Brain Res. 1980;194:548–55. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katzenellenbogen BS, Gorski J. Estrogen action in vitro. Induction of the synthesis of a specific uterine protein. J Biol Chem. 1972;247:1299–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meisel RL, Pfaff DW. RNA and protein synthesis inhibitors: effects on sexual behavior in female rats. Brain Res Bull. 1984;12:187–93. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90188-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szego CM, Davis JS. Adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate in rat uterus: acute elevation by estrogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967;58:1711–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.4.1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong M, Moss RL. Long-term and short-term electrophysiological effects of estrogen on the synaptic properties of hippocampal CA1 neurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3217–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03217.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lagrange AH, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Modulation of G protein-coupled receptors by an estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase A. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;51:605–12. doi: 10.1124/mol.51.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levin ER, Pietras RJ. Estrogen receptors outside the nucleus in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108:351–61. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly MJ, Ronnekleiv OK. Membrane-initiated estrogen signaling in hypothalamic neurons. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2008;290:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micevych PE, Mermelstein PG. Membrane estrogen receptors acting through metabotropic glutamate receptors: an emerging mechanism of estrogen action in brain. Mol Neurobiol. 2008;38:66–77. doi: 10.1007/s12035-008-8034-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mermelstein PG, Becker JB, Surmeier DJ. Estradiol reduces calcium currents in rat neostriatal neurons via a membrane receptor. J Neurosci. 1996;16:595–604. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00595.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wade CB, Robinson S, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM. Estrogen receptor (ER)alpha and ERbeta exhibit unique pharmacologic properties when coupled to activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2001;142:2336–42. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.6.8071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly MJ, Loose MD, Ronnekleiv OK. Estrogen suppresses mu-opioid- and GABAB-mediated hyperpolarization of hypothalamic arcuate neurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:2745–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02745.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kow LM, Pfaff DW. Mapping of neural and signal transduction pathways for lordosis in the search for estrogen actions on the central nervous system. Behav Brain Res. 1998;92:169–80. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaban VV, Lakhter AJ, Micevych P. A Membrane Estrogen Receptor Mediates Intracellular Calcium Release in Astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3788–3795. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foy MR, Xu J, Xie X, Brinton RD, Thompson RF, Berger TW. 17beta-estradiol enhances NMDA receptor-mediated EPSPs and long-term potentiation. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:925–9. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.2.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasudevan N, Kow LM, Pfaff D. Integration of steroid hormone initiated membrane action to genomic function in the brain. Steroids. 2005;70:388–96. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchak K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych P. Membrane estrogen receptor-alpha interactions with metabotropic glutamate receptor 1a modulate female sexual receptivity in rats. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9294–300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0592-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Micevych PE, Chaban V, Ogi J, Dewing P, Lu JK, Sinchak K. Estradiol stimulates progesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocyte cultures. Endocrinology. 2007;148:782–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1172:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng J, Ali A, Ramirez VD. Steroids conjugated to bovine serum albumin as tools to demonstrate specific steroid neuronal membrane binding sites. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 1996;21:187–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quesada I, Fuentes E, Viso-Leon MC, Soria B, Ripoll C, Nadal A. Low doses of the endocrine disruptor bisphenol-A and the native hormone 17beta-estradiol rapidly activate transcription factor CREB. Faseb J. 2002;16:1671–3. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0313fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, MacBride MM, Peterson BR, Pfaff DW, Vasudevan N. Calcium flux in neuroblastoma cells is a coupling mechanism between non-genomic and genomic modes of estrogens. Neuroendocrinology. 2005;81:174–82. doi: 10.1159/000087000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERalpha and ERbeta expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Endocrinol. 1999;13:307–19. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gu Q, Korach KS, Moss RL. Rapid action of 17beta-estradiol on kainate-induced currents in hippocampal neurons lacking intracellular estrogen receptors. Endocrinology. 1999;140:660–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.2.6500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toran-Allerand CD, Guan X, MacLusky NJ, Horvath TL, Diano S, Singh M, Connolly ES, Jr, Nethrapalli IS, Tinnikov AA. ER-X: a novel, plasma membrane-associated, putative estrogen receptor that is regulated during development and after ischemic brain injury. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8391–401. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08391.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Krust A, Graham SM, Murphy SJ, Korach KS, Chambon P, Scanlan TS, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. A G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor is involved in hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5649–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0327-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Filardo EJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation by estrogen via the G-protein-coupled receptor, GPR30: a novel signaling pathway with potential significance for breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;80:231–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00190-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reinscheid RK, Nothacker HP, Bourson A, Ardati A, Henningsen RA, Bunzow JR, Grandy DK, Langen H, Monsma FJ, Jr, Civelli O. Orphanin FQ: a neuropeptide that activates an opioidlike G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1995;270:792–4. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meunier JC, Mollereau C, Toll L, Suaudeau C, Moisand C, Alvinerie P, Butour JL, Guillemot JC, Ferrara P, Monsarrat B, et al. Isolation and structure of the endogenous agonist of opioid receptor-like ORL1 receptor. Nature. 1995;377:532–5. doi: 10.1038/377532a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filardo EJ, Quinn JA, Bland KI, Frackelton AR., Jr Estrogen-induced activation of Erk-1 and Erk-2 requires the G protein-coupled receptor homolog, GPR30, and occurs via trans-activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor through release of HB-EGF. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1649–60. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thomas P, Pang Y, Filardo EJ, Dong J. Identity of an estrogen membrane receptor coupled to a G protein in human breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146:624–32. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–30. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor that activates protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9529–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09529.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on cAMP response element-binding protein. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–78. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dewing P, Christensen A, Bondar G, Micevych P. Protein kinase C signaling in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus regulates sexual receptivity in female rats. Endocrinology. 2008;149:5934–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulware MI, Kordasiewicz H, Mermelstein PG. Caveolin proteins are essential for distinct effects of membrane estrogen receptors in neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9941–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1647-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Micevych PE, Abelson L, Fok H, Ulibarri C, Priest CA. Gonadal steroid control of preprocholecystokinin mRNA expression in the limbic-hypothalamic circuit: comparison of adult with neonatal steroid treatments. J Neurosci Res. 1994;38:386–98. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490380404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sinchak K, Micevych P. Visualizing activation of opioid circuits by internalization of G protein-coupled receptors. Mol Neurobiol. 2003;27:197–222. doi: 10.1385/MN:27:2:197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinchak K, Micevych PE. Progesterone blockade of estrogen activation of mu-opioid receptors regulates reproductive behavior. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5723–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05723.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Micevych PE, Rissman EF, Gustafsson JA, Sinchak K. Estrogen receptor-alpha is required for estrogen-induced mu-opioid receptor internalization. J Neurosci Res. 2003;71:802–10. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills RH, Sohn RK, Micevych PE. Estrogen-induced mu-opioid receptor internalization in the medial preoptic nucleus is mediated via neuropeptide Y-Y1 receptor activation in the arcuate nucleus of female rats. J Neurosci. 2004;24:947–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1366-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eckersell CB, Popper P, Micevych PE. Estrogen-induced alteration of mu-opioid receptor immunoreactivity in the medial preoptic nucleus and medial amygdala. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3967–76. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03967.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinchak K, Shahedi K, Dewing P, Micevych P. Sexual receptivity is reduced in the female mu-opioid receptor knockout mouse. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1697–700. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000181585.49130.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beyer C, Karolczak M. Estrogenic stimulation of neurite growth in midbrain dopaminergic neurons depends on cAMP/protein kinase A signalling. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:107–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Devidze N, Pfaff DW, Kow LM. Potentiation of genomic actions of estrogen by membrane actions in mcf-7 cells and the involvement of protein kinase C activation. Endocrine. 2005;27:253–8. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:27:3:253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lewis MC, Kerr KM, Orr PT, Frick KM. Estradiol-induced enhancement of object memory consolidation involves NMDA receptors and protein kinase A in the dorsal hippocampus of female C57BL/6 mice. Behav Neurosci. 2008;122:716–21. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.3.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang B, Ji Y, Traub RJ. Estrogen alters spinal NMDA receptor activity via a PKA signaling pathway in a visceral pain model in the rat. Pain. 2008;137:540–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kow LM, Pfaff DW. The membrane actions of estrogens can potentiate their lordosis behavior-facilitating genomic actions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12354–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404889101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kow LM, Brown HE, Pfaff DW. Activation of protein kinase C in the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus or the midbrain central gray facilitates lordosis. Brain Res. 1994;660:241–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91295-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Doolan CM, Harvey BJ. Modulation of cytosolic protein kinase C and calcium ion activity by steroid hormones in rat distal colon. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8763–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Redig AJ, Platanias LC. The protein kinase C (PKC) family of proteins in cytokine signaling in hematopoiesis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:623–36. doi: 10.1089/jir.2007.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Uphouse L, Maswood S, Jackson A. Factors elevating cAMP attenuate the effects of 8-OH-DPAT on lordosis behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:383–8. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watters JJ, Dorsa DM. Transcriptional effects of estrogen on neuronal neurotensin gene expression involve cAMP/protein kinase A-dependent signaling mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6672–80. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06672.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shingo AS, Kito S. Estradiol induces PKA activation through the putative membrane receptor in the living hippocampal neuron. J Neural Transm. 2005;112:1469–73. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aronica SM, Fanti P, Kaminskaya K, Gibbs K, Raiber L, Nazareth M, Bucelli R, Mineo M, Grzybek K, Kumin M, Poppenberg K, Schwach C, Janis K. Estrogen disrupts chemokine-mediated chemokine release from mammary cells: implications for the interplay between estrogen and IP-10 in the regulation of mammary tumor formation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;84:235–45. doi: 10.1023/B:BREA.0000019961.59306.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Minami T, Oomura Y, Nabekura J, Fukuda A. 17 beta-estradiol depolarization of hypothalamic neurons is mediated by cyclic AMP. Brain Res. 1990;519:301–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90092-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nabekura J, Omura T, Akaike N. Alpha 2 adrenoceptor potentiates glycine receptor-mediated taurine response through protein kinase A in rat substantia nigra neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1996;76:2447–54. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.4.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schreihofer DA, Resnick EM, Lin VY, Shupnik MA. Ligand-independent activation of pituitary ER: dependence on PKA-stimulated pathways. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3361–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.8.8333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chazal G, Faudon M, Gogan F, Laplante E. Negative and positive effects of oestradiol upon luteinizing hormone secretion in the female rat. J Endocrinol. 1974;61:511–2. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0610511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brom GM, Schwartz NB. Acute changes in the estrous cycle following ovariectomy in the golden hamster. Neuroendocrinology. 1968;3:366–77. doi: 10.1159/000121725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ferin M, Tempone A, Zimmering PE, Van de Wiele RL. Effect of antibodies to 17beta-estradiol and progesterone on the estrous cycle of the rat. Endocrinology. 1969;85:1070–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-85-6-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Labhsetwar AP, Diamond M. Ovarian changes in the guinea pig during various reproductive stages and steroid treatments. Biol Reprod. 1970;2:53–7. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod2.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rao IM, Mahesh VB. Role of progesterone in the modulation of the preovulatory surge of gonadotropins and ovulation in the pregnant mare’s serum gonadotropin-primed immature rat and the adult rat. Biol Reprod. 1986;35:1154–61. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod35.5.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mahesh VB, Brann DW. Regulation of the preovulatory gonadotropin surge by endogenous steroids. Steroids. 1998;63:616–29. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(98)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chappell PE, Levine JE. Stimulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone surges by estrogen. I. Role of hypothalamic progesterone receptors. Endocrinology. 2000;141:1477–85. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.4.7428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Micevych P, Sinchak K, Mills RH, Tao L, LaPolt P, Lu JK. The luteinizing hormone surge is preceded by an estrogen-induced increase of hypothalamic progesterone in ovariectomized and adrenalectomized rats. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;78:29–35. doi: 10.1159/000071703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feder HH, Brown-Grant K, Corker CS. Pre-ovulatory progesterone, the adrenal cortex and the ‘critical period’ for luteinizing hormone release in rats. J Endocrinol. 1971;50:29–39. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0500029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kalra SP, Kalra PS. Temporal interrelationships among circulating levels of estradiol, progesterone and LH during the rat estrous cycle: effects of exogenous progesterone. Endocrinology. 1974;95:1711–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-95-6-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Smith MS, Freeman ME, Neill JD. The control of progesterone secretion during the estrous cycle and early pseudopregnancy in the rat: prolactin, gonadotropin and steroid levels associated with rescue of the corpus luteum of pseudopregnancy. Endocrinology. 1975;96:219–26. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soma KK, Sinchak K, Lakhter A, Schlinger BA, Micevych PE. Neurosteroids and female reproduction: estrogen increases 3beta-HSD mRNA and activity in rat hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2005;146:4386–90. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Micevych P, Sinchak K. Synthesis and function of hypothalamic neuroprogesterone in reproduction. Endocrinology. 2008;149:2739–42. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sinchak K, Mills RH, Tao L, LaPolt P, Lu JK, Micevych P. Estrogen induces de novo progesterone synthesis in astrocytes. Dev Neurosci. 2003;25:343–8. doi: 10.1159/000073511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kuo J, Hariri OR, Bondar G, Ogi J, Micevych P. Membrane Estrogen Receptor-Alpha Interacts with Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 1a to Mobilize Intracellular Calcium in Hypothalamic Astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2008 doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0994. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Garcia-Segura LM, Naftolin F, Hutchison JB, Azcoitia I, Chowen JA. Role of astroglia in estrogen regulation of synaptic plasticity and brain repair. J Neurobiol. 1999;40:574–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pawlak J, Karolczak M, Krust A, Chambon P, Beyer C. Estrogen receptor-alpha is associated with the plasma membrane of astrocytes and coupled to the MAP/Src-kinase pathway. Glia. 2005;50:270–5. doi: 10.1002/glia.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Quesada A, Romeo HE, Micevych P. Distribution and localization patterns of estrogen receptor-beta and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptors in neurons and glial cells of the female rat substantia nigra: localization of ERbeta and IGF-1R in substantia nigra. J Comp Neurol. 2007;503:198–208. doi: 10.1002/cne.21358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chaban VV, Lakhter AJ, Micevych P. A membrane estrogen receptor mediates intracellular calcium release in astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3788–95. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dewing P, Boulware MI, Sinchack K, Christensen A, Mermelstein PG, Micevych P. Membrane ERα interacts with mGluR1a to modulate female sexual receptivity. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9294–300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0592-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alberdi E, Sanchez-Gomez MV, Matute C. Calcium and glial cell death. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jessen KR. Glial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1861–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]