Abstract

Objectives To elucidate current trends and geographical patterns in the sex ratio at birth and in the population aged under 20 in China and to determine the roles played by sex selective abortion and the one child policy.

Design Analysis of household based cross sectional population survey done in November 2005.

Setting All of China’s 2861 counties.

Population 1% of the total population, selected to be broadly representative of the total.

Main outcome measure Sex ratio defined as males per 100 females.

Results 4 764 512 people under the age of 20 were included. Overall sex ratios were high across all age groups and residency types, but they were highest in the 1-4 years age group, peaking at 126 (95% confidence interval 125 to 126) in rural areas. Six provinces had sex ratios of over 130 in the 1-4 age group. The sex ratio at birth was close to normal for first order births but rose steeply for second order births, especially in rural areas, where it reached 146 (143 to 149). Nine provinces had ratios of over 160 for second order births. The highest sex ratios were seen in provinces that allow rural inhabitants a second child if the first is a girl. Sex selective abortion accounts for almost all the excess males. One particular variant of the one child policy, which allows a second child if the first is a girl, leads to the highest sex ratios.

Conclusions In 2005 males under the age of 20 exceeded females by more than 32 million in China, and more than 1.1 million excess births of boys occurred. China will see very high and steadily worsening sex ratios in the reproductive age group over the next two decades. Enforcing the existing ban on sex selective abortion could lead to normalisation of the ratios.

Introduction

In the absence of intervention, the sex ratio at birth is consistent across populations at between 103 and 107 boys born for every 100 girls.1 2 Higher early mortality among boys ensures a ratio of close to 100 in the all important reproductive years. However, in many countries, mainly in South and East Asia, the sex ratio deviates from this norm because of the tradition of preference for sons.3 Historically, preference for sons has been manifest postnatally through female infanticide and the neglect and abandonment of girls.4 Where this persists, it mainly consists of failure to access necessary medical care.5 6 However, since the early 1980s selection for males prenatally with ultrasonographic sex determination and sex selective abortion has been possible. This technology has become widely available in many countries, leading to high sex ratios from birth.5 The highest sex ratios are seen in countries with a combination of preference for sons, easy access to sex selective technology, and a low fertility rate, as births of girls must be prevented to allow for the desired number of sons within the family size.7 In the era of the one child policy the fact that the problem of excess males in China seems to outstrip that of all other countries is perhaps no surprise.6 8

Some of the evidence for this sex imbalance in China has been challenged, because accurate population based figures have been difficult to obtain.9 10 Births classified as “illegal,” violating the one child policy, may be concealed to avoid penalties.11 12 Under-reporting of births of girls may be more common in this context, leading to spuriously high sex ratios at birth.13 14 However, if girls are not reported at birth, they are likely to filter into the statistics later, as registration is necessary for immunisation or to start school.15 Therefore, examining the sex ratio across different age bands provides a more accurate picture.

The objectives of this study were to elucidate current trends and geographical patterns in the sex ratio at birth and in the population under the age of 20 in China and to explore the role played by sex selective abortion and the one child policy in the sex imbalance.

Methods

We analysed data from the intercensus survey of 2005, which was carried out on a representative 1% of the total population in November 2005 and is the most recent national population survey. It used the same basic organisation, procedures, and questionnaire as the fifth census of 2000, but the mode of implementation took into account acknowledged deficiencies of the 2000 census, which led to under-numeration of the population by an estimated 1.8%, mostly in the youngest age groups, resulting in possible inaccuracies in the sex ratio.16 Specific measures were therefore incorporated into this survey to solve problems of under-numeration, and quality control methods were used to minimise sampling bias. These are described in detail elsewhere.16 The survey covered all of China’s 2861 counties, using a three stage cluster sampling method at township, village, and enumeration district level, with probability proportionate to estimated size, and is hence broadly representative of the total population. The minimal sampling unit was the enumeration district, which consisted of the village committee in rural areas and the neighbourhood committee in urban areas. The survey was carried out in households by staff specifically trained in census techniques. Only data for the under 20 age group are reported here.

Analysis—The major outcome variable is the sex ratio, defined as males per 100 females. We derived 95% confidence intervals for the sex ratios by using the 95% confidence interval for the proportion of female births (pf) with a variance of pf(1-pf). We calculated the excess of males for all age groups by using an average of the mean sex ratios from 13 countries that have normal secondary sex ratios and little or no sex preference.17 These were 105 for the 1-9 age group and 104 for the 10-19 age group.

Results

The survey counted 4 764 512 people under the age of 20: 1 073 229 (22%) urban residents, 813 386 (17%) town residents, and 2 877 897 (60%) rural inhabitants. In the 12 months before the study 161 109 births were reported: 23% in urban areas, 17% in towns, and 60% in rural areas. First order births accounted for 63% of the total, second order for 32%, third order for 4.3%, and fourth or higher order for 1%.

Under 20 sex ratio

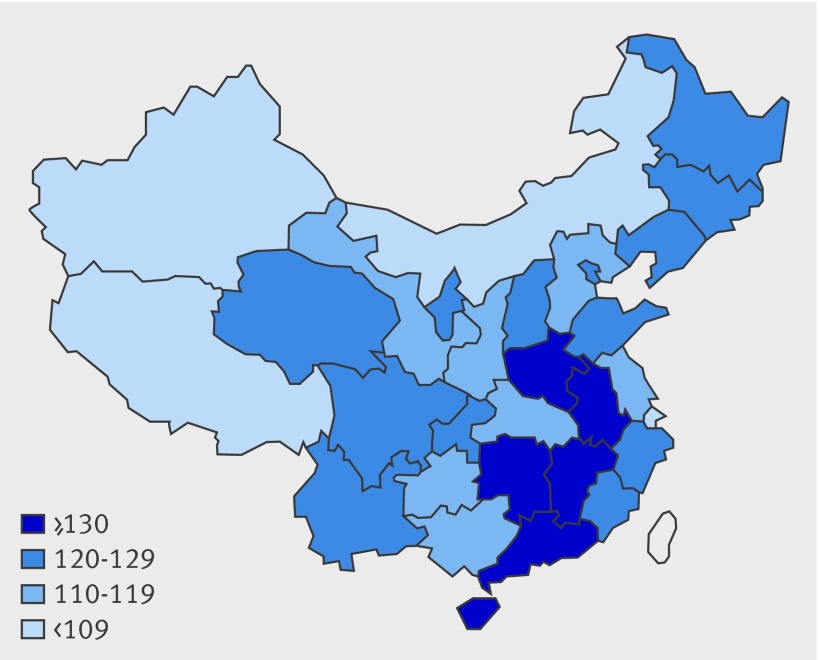

Table 1 shows the sex ratio by age group and type of residency. Sex ratios were consistently higher than normal across residency type and all age groups except for urban 15-19 year olds. Sex ratios peaked in the 1-4 age group; the highest was 126 (95% confidence interval 125 to 126) in rural areas. Table 2 shows the sex ratio by age group for all provinces. Only two provinces, Tibet and Xinjiang, had sex ratios within normal limits across the age range. Two provinces, Jiangxi and Henan, had ratios of over 140 in the 1-4 age group; four provinces—Anhui, Guangdong, Hunan, and Hainan—had ratios of over 130; and seven provinces had ratios between 120 and 129. The provinces with the highest sex ratios are clustered together in the central-southern region (fig 1). Notably, sex ratios were high into the teenage groups in Hainan and Guangxi. The excess of males increased from 5.1% (n=142 634) in the cohort born between 1986 and 1995 to 9.4% (n=184 970) in the cohort born between 1996 and 2005 across the whole country. A marked rise occurred in the percentage of excess males between the two cohorts in all provinces except Xinjiang.

Table 1 .

Sex ratio (95% confidence interval) by age and residence, under 20 year olds

| Residence | No (%) | Age (year of birth) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year (2004-5) (n=182 393) | 1-4 years (2000-4) (n=724 709) | 5-9 years (1995-9) (n=1 060 664) | 10-14 years (1990-4) (n=1 353 263) | 15-19 years (1985-9) (n=1 443 483) | ||

| All | 4 764 512 | 119 (119 to 120) | 124 (123 to 124) | 119 (119 to 120) | 114 (113 to 114) | 108 (108 to 109) |

| Urban* | 1 073 229 (23) | 114 (112 to 115) | 116 (115 to 117) | 116 (115 to 117) | 112 (111 to 114) | 101 (100 to 103) |

| Town† | 813 386 (17) | 117 (115 to 119) | 122 (120 to 124) | 121 (120 to 122) | 116 (115 to 117) | 109 (107 to 111) |

| Rural‡ | 2 877 897 (60) | 122 (121 to 122) | 126 (125 to 126) | 120 (120 to 121) | 114 (113 to 114) | 111 (110 to 111) |

*Area with more than 100 000 non-agricultural population.

†Population of at least 20 000, where non-agricultural population exceeds 10%.

‡More than 90% agricultural workers.

Table 2.

Sex ratios (95% confidence intervals) by age group and province, and excess males

| Region and province (population in millions) | No | Age group | Excess males <10 years (%) | Excess males 10-20 years (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 year | 1-4 years | 5-9 years | 10-14 years | 15-19 years | ||||

| All | 4 764 512 | 119 (119 to 120) | 124 (123 to 124) | 119 (119 to 120) | 114 (114 to 115) | 108 (107 to 108) | 9.4 | 5.1 |

| North: | ||||||||

| Beijing (14) | 35 657 | 114 (102 to 127) | 112 (105 to 118) | 110 (106 to 115) | 104 (100 to 109) | 111 (108 to 115) | 5.4 | 4.1 |

| Tianjin (10) | 29 170 | 114 ( 100 to 130) | 118 (111 to 126) | 115 (109 to 122) | 110 (106 to 115) | 99 (96 to 103) | 7.5 | 1.7 |

| Hebei (65) | 250 933 | 120 (116 to 125) | 122 (120 to 125) | 115 (113 to 117) | 111 (109 to 113) | 104 (102 to 105) | 8.4 | 3.2 |

| Shanxi (32) | 131 763 | 116 (110 to 123) | 112 (109 to 116) | 109 (107 to 111) | 109 (107 to 111) | 106 (104 to 108) | 5.1 | 3.6 |

| Inner Mongolia (23) | 76 693 | 114 (107 to 122) | 107 (103 to 111) | 109 (106 to 113) | 110 (107 to 113) | 107 (104 to 109) | 4.3 | 4.0 |

| Northeast: | ||||||||

| Liaoning (42) | 118 018 | 113 (106 to 120) | 114 (111 to 117) | 111 (108 to 114) | 110 (108 to 113) | 106 (103 to 108) | 5.6 | 3.7 |

| Jilin (26) | 81 133 | 113 (105 to 121) | 112 (108 to 116) | 113 (110 to 117 | 110 (107 to 113) | 107 (104 to 109) | 5.9 | 3.8 |

| Heilongjiang (38) | 112 057 | 109 (103 to 116) | 111 (108 to 115) | 107 (104 to 110) | 108 (105 to 110) | 107 (105 to 109) | 4.1 | 3.4 |

| East: | ||||||||

| Shanghai (17) | 37 406 | 117 (106 to 128) | 109 (103 to 115) | 111 (105 to 116) | 108 (103 to 113) | 98 (95 to 101) | 4.9 | 0.4 |

| Jiangsu (71) | 230 997 | 125 (120 to 131) | 123 (120 to 126) | 121 (119 to 124) | 118 (116 to 120) | 105 (103 to 106) | 10 | 5.0 |

| Zhejiang (43) | 150 125 | 114 (109 to 119) | 113 (111 to 116) | 113 (111 to 116) | 113 (111 to 116) | 108 (106 to 110) | 6.3 | 5.0 |

| Anhui (61) | 256 350 | 131 (126 to 137) | 138 (135 to 141) | 124 (122 to 127) | 115 (114 to 117) | 107 (106 to 109) | 12.9 | 5.5 |

| Fujian (33) | 129 146 | 122 (116 to 129) | 119 (116 to 122) | 124 (121 to 127) | 118 (116 to 121) | 101 (99 to 103) | 9.8 | 4.2 |

| Jiangxi (41) | 186 198 | 129 (121 to 137) | 143 (140 to 146) | 130 (128 to 133) | 118 (116 to 120) | 114 (112 to 116) | 14.8 | 7.6 |

| Shandong (91) | 303 287 | 114 (110 to 118) | 116 (114 to 118) | 116 (114 to 118) | 115 (114 to 117) | 106 (105 to 108) | 7.4 | 4.5 |

| Central: | ||||||||

| Henan (95) | 386 594 | 122 (118 to 126) | 142 (140 to 144) | 131 (129 to 133) | 119 (118 to 121) | 110 (109 to 111) | 14.4 | 6.7 |

| Hubei (58) | 208 230 | 128 (122 to 135) | 129 (126 to 133) | 129 (126 to 132) | 120 (118 to 121) | 118 (117 to 120) | 12.6 | 8.7 |

| Hunan (64) | 232 938 | 122 (117 to 127) | 133 (130 to 136) | 122 (120 to 124) | 115 (113 to 117) | 112 (110 to 113) | 11.6 | 6.1 |

| Guangdong (70) | 384 845 | 119 (115 to 123) | 133 (131 to135) | 127 (126 to 129) | 115 (113 to 116) | 96 (95 to 97) | 12.3 | 2.2 |

| Guangxi (46) | 199 776 | 121 (116 to 126) | 122 (120 to 125) | 127 (125 to 130) | 122 (120 to 124) | 123 (121 to 125) | 11.0 | 10.2 |

| Hainan (7.5) | 36 427 | 123 (111 to 136) | 134 (127 to 141) | 135 (129 to141) | 120 (113 to 127) | 123 (118 to 128) | 6..2 | 9.3 |

| Southwest: | ||||||||

| Chongqing (31) | 100 070 | 112 (104 to 120) | 119 (115 to 123) | 117 (114 to 120) | 113 (110 to 115) | 114 (111 to 117) | 7.9 | 6.2 |

| Sichuan (84) | 311 530 | 115 (110 to 119) | 116 (114 to 118) | 114 (112 to 116) | 111 (110 to 113) | 108 (106 to 109) | 6.8 | 4.6 |

| Guizhou (37) | 178 547 | 128 (112 to 134) | 127 (124 to 130) | 115 (113 to 117) | 112 (110 to 114) | 119 (117 to 122) | 9.0 | 7.2 |

| Yunnan (41) | 189 774 | 113 (108 to 118) | 115 (113 to117) | 112 (110 to 114) | 112 (110 to 114) | 112 (110 to 114) | 6.2 | 5.9 |

| Tibet (3) | 13 764 | 102 (88 to 120) | 104 (96 to113) | 105 (98 to 112) | 102 (95 to 108) | 105 (98 to 112) | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| Northwest: | ||||||||

| Shaanxi (36) | 141 904 | 134 (126 to 143) | 125 (121 to 129) | 123 (120 to 126) | 117 (115 to 119) | 112 (110 to 114) | 10.9 | 6.6 |

| Gansu (25) | 112 399 | 116 (109 to 124) | 120 (117 to 124) | 116 (113 to 119) | 109 (107 to 111) | 106 (104 to 109) | 3.8 | 0.1 |

| Qinghai (5) | 23 483 | 117 (103 to 133) | 111 (105 to 118) | 109 (104 to 115) | 104 (98 to 110) | 100 (95 to 106) | 5.0 | 0.1 |

| Ningxia (5) | 27 373 | 107 (96 to 119) | 112 (106 to 119) | 108 (103 to 113) | 106 (101 to 110) | 104 (99 to 109) | 4.5 | 2.3 |

| Xinjiang (17) | 87 919 | 105 (99 to 112) | 106 (102 to 109) | 104 (101 to 107) | 106 (103 to 108) | 107 (104 to 110) | 2.2 | 3 |

Fig 1 Sex ratio in 1-4 year age group: all China’s provinces

Sex ratio at birth

The total sex ratio at birth for the 12 months to October 2005 was 120 (119 to 121) for the whole sample (table 3), with a gradient between urban (115, 113 to 117), town (120, 118 to 122), and rural (123, 121 to 124) areas. This equates to 11 320 excess boys born for the year for the whole sample. The total sex ratio at birth was over 130 in three provinces (Shaanxi, Anhui, and Jiangxi) and over 120 in 14 provinces. These overall figures conceal dramatic differences in sex ratio at birth by birth order. The sex ratio at birth for first order births was slightly high in cities and towns but was within normal limits in rural areas. However, the ratio rose very steeply for second and higher order births in cities 138 (132 to 144), towns 137 (131 to 143), and rural areas 146 (143 to 149), although the numbers of second order births in cities were low. These rises were consistent across all provinces, except Tibet, with very high figures for second births in Anhui (190, 176 to 205) and Jiangsu (192, 174 to 212). For third births, the sex ratio rose to over 200 in four provinces, although third births accounted for only 4.3% of the total.

Table 3.

Sex ratios at birth by birth order for November 2004 to October 2005

| No | Total (n=161 109) | First order (n=101 399) | Second order (n=51 017) | Third order (n=6996) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 161 109 | 120 (119 to 121) | 108 (107 to 110) | 143 (141 to 146) | 157 (149 to 164) |

| City* | 36 882 | 115 (113 to 117) | 110 (107 to 113) | 138 (132 to 144) | 146 (127 to 168) |

| Town† | 27 254 | 120 (118 to 122) | 111 (108 to 115) | 137 (131 to 143) | 165 (143 to 190) |

| Rural‡ | 96 973 | 123 (121 to 124) | 107 (105 to 108) | 146 (143 to 149) | 157 (148 to 165) |

| Beijing | 1 207 | 118 (105 to 131) | 115 (102 to 128) | 123 (92 to 155) | 275 (85 to 1071) |

| Tianjin | 887 | 120 (104 to 136) | 110 (94 to 128) | 155 (119 to 192) | 101 (47 to 414) |

| Hebei | 10 774 | 119 (115 to 124) | 110 (105 to 116) | 134 (126 to 143) | 147 (118 to 185) |

| Shanxi | 4 641 | 117 (110 to 125) | 109 (101 to 117) | 128 (116 to 142) | 160 (119 to 209) |

| Inner Mongolia | 2 781 | 117 (108 to 117) | 113 (103 to 122) | 134 (113 to 156) | 94 (54 to 187) |

| Liaoning | 3 772 | 109 (103 to 115) | 104 (97 to 112) | 126 (111 to 143) | 123 (71 to 199) |

| Jilin | 2 639 | 109 (101 to 118) | 107 (97 to 117) | 112 (98 to 128) | 160 (87 to 278) |

| Heilongjiang | 3 659 | 110 (104 to 117) | 113 (105 to 122) | 101 (88 to 115) | 164 (107 to 295) |

| Shanghai | 1 427 | 120 (108 to 132) | 111 (99 to 123) | 176 (136 to 220) | 113 (34 to 292) |

| Jiangsu | 8 139 | 126 (121 to 131) | 111 (106 to 117) | 192 (174 to 211) | 188 (138 to 268) |

| Zhejiang | 6 048 | 113 (108 to 119) | 109 (102 to 115) | 122 (111 to 134) | 170 (117 to 241) |

| Anhui | 8 583 | 132 (127 to 138) | 107 (101 to 113) | 190 (176 to 205) | 227 (178 to 304) |

| Fujian | 4 551 | 126 (119 to 134) | 113 (105 to 121) | 168 (149 to 188) | 148 (100 to 234) |

| Jiangxi | 6 337 | 137 (131 to 144) | 108 (101 to 116) | 178 (164 to 194) | 206 (168 to 257) |

| Shandong | 12 951 | 113 (110 to 117) | 109 (105 to 114) | 120 (112 to 127) | 163 (127 to 206) |

| Henan | 10 992 | 126 (121 to 131) | 104 (99 to 110) | 166 (156 to 177) | 129 (108 to 154) |

| Hubei | 6 034 | 128 (122 to 135) | 113 (107 to 120) | 170 (154 to 185) | 184 (132 to 270) |

| Hunan | 7 910 | 128 (122 to 134) | 112 (106 to 118) | 155 (144 to 168) | 181 (146 to 226) |

| Guangdong | 11 164 | 120 (116 to 125) | 108 (103 to 113) | 146 (136 to 157) | 167 (141 to 201) |

| Guangxi | 7 505 | 120 (115 to 125) | 105 (99 to 111) | 137 (126 to 148) | 160 (137 to 190) |

| Hainan | 1 364 | 122 (110 to 135) | 111 (97 to 126) | 138 (117 t o 157) | 142 (98 to 212) |

| Chongqing | 2 448 | 111 (103 to 120) | 108 (97 to 120) | 115 (101 t o 130) | 127 (89 to 177) |

| Sichuan | 9 076 | 116 (112 to 121) | 106 (101 to 112) | 129 (120 to 139) | 141 (121 to 163) |

| Guizhou | 5 771 | 128 (121 to 135) | 102 (95 to 109) | 168 (152 to 185) | 208 (171 to 255) |

| Yunnan | 7 633 | 113 (108 to 118) | 106 (100 to 113) | 119 (110 to 187) | 137 (115 to 166) |

| Tibet | 509 | 105 (88 to 123) | 105 (81 to 129) | 101 (69 to 131) | 119 (75 to 185) |

| Shaanxi | 3 689 | 132 (124 to 141) | 117 (108 to 127) | 168 (149 to 194) | 185 (126 to 297) |

| Gansu | 3 215 | 116 (109 to 125) | 99 (91 to 109) | 147 (130 to 166) | 139 (107 to 188) |

| Qinghai | 812 | 117 (102 to 133) | 107 (90 to 125) | 124 (98 to 150) | 188 (108 to 368) |

| Ningxia | 1 078 | 111 (99 to 126) | 106 (90 to 122) | 128 (105 to 152) | 95 (64 to 139) |

| Xinjiang | 3 514 | 109 (102 to 117) | 102 (94 to 111) | 120 (105 to 136) | 127 (104 to 156) |

*Area with more than 100 000 non-agricultural population.

†Population of at least 20 000, where non-agricultural population exceeds 10%.

‡More than 90% agricultural workers.

Discussion

The findings paint a discouraging picture of very high and increasing sex ratios in the reproductive age group in China for the next two decades. The sex ratio increased steadily from 108 (108 to 109) in the cohort born between 1985 and 1989 to 124 (123 to 124) in the 2000 to 2004 cohort. However, the ratio then declined to 119 (119 to 120) for the 2005 cohort, perhaps indicating the beginning of a reduction in sex ratios for the future. Sex ratios were outside the normal range for almost all age groups in almost all provinces. The sex ratios rose dramatically between first and second order births, with very high sex ratios for the very few higher order births. Tibet and Xinjiang were the notable exceptions. The highest ratios were seen in the centre and south of the country, in the highly populous provinces of Henan, Jiangxi, Anhui, Guangdong, and Hainan. Extrapolating from this 1% sample to the whole country, we estimate that an excess of 1 132 000 boys were born in the 12 months to October 2005 and that an excess of 32 706 400 males under the age of 20 existed in the whole of China at that time, 18 497 000 of them under the age of 10.

This is the most recent nationwide demographic survey in China, a country undergoing rapid socioeconomic change, where timely data are of particular importance. The survey used specific measures to attempt to ensure coverage of the target group, in order to more accurately estimate the sex ratio.16 A very large survey aiming to represent 1% of the total population obviously has some limitations. Complete coverage of households and inhabitants is clearly impossible on such a large scale. Furthermore, extrapolation to the whole population from a 1% sample should be done with caution. The small sample size at provincial level in some age bands and for second and higher order births leads to wide confidence intervals, illustrating the uncertainty around these figures. However, the overall credibility of the data is increased by the high sex ratios in older age groups, for which concealment and under-reporting of girls would be difficult, and by the number of births counted for the 12 months to October 2005 (161 109), which matches the estimate of 16 million births a year from other sources.18 The findings increase our understanding of the roles of sex selective abortion and the influence of the one child policy in the sex imbalance in China and have clear policy implications.

Role of sex selective abortion

The precise role of sex selective abortion in the sex imbalance has been unclear, not least because the practice is illegal in China and obtaining reliable figures is therefore difficult. Some small rural studies have made estimates for proportions of sex selective abortions from hospital based and community birth records.19 20 21 Two concluded that sex selective abortion was the major cause of the sex imbalance; however, local circumstances vary hugely in China, so wider inferences need to be made with caution. The findings of this survey help to elucidate the role of sex selective abortion in the high sex ratio at the national level.

Firstly, if under-registration of girls, rather than sex selective abortion, accounted for most of the excess births of boys, then sex ratios would fall from birth through early childhood, as girls are required to be registered for immunisation and school entry.15 Our finding that the sex ratios for the 1-4 year old cohort are higher than those at birth and in infancy tends to refute this hypothesis, suggesting that the rise in the 1-4 age group is a cohort effect—that is, it reflects the higher sex ratio at birth in this cohort. To further investigate the role of under-registration, comparison can be made between each cohort specific sex ratio and the corresponding sex ratio at birth from previous census data.22 23 This shows that with only one exception, the 15-19 year old cohort born between 1985 and 1989, the sex ratio at birth was higher or very close to the sex ratio of the corresponding birth cohort in the 2005 survey: the age 1-4 cohort had a sex ratio of 124 and a sex ratio at birth of 120, the 5-9 cohort had a sex ratio of 119 and a sex ratio at birth of 118, the corresponding ratios for the 10-14 cohort were 114 and 112, and those for the 15-19 cohort were 108 and 111. This lends support to the assertion that under-registration of girls is not a major contributor to high sex ratios at birth. Infanticide is of course another possible explanation for girls missing at birth, but this is widely acknowledged to be very rare now.24 25 26 27

Secondly, the dramatic increase in sex ratio with second births that our data document, shows that couples are selecting to ensure a boy, the so called “at least one son practice.”15 In urban areas where few couples are allowed a second child, the high sex ratio for first order births (110, 95% confidence interval 107 to 113) suggests some sex selection occurring with the only child. This pattern of dramatic increases in sex ratios for second children is not unique to China. In both South Korea and parts of India, where overall sex ratios are high, the sex ratio increases dramatically for second and higher order births, which has been attributed to sex selective abortion, as couples try to ensure the birth of male offspring while limiting their family size.7 28

Thirdly, the steady rise in sex ratios across the birth cohorts since 1986 mirrors the increasing availability of ultrasonography over that period. The first ultrasound machines were used in the early 1980s; they reached county hospitals by the late 1980s and then rural townships by the mid-1990s.21 29 Since then, ultrasonography has been very cheap and available even to the rural poor. Termination of pregnancy is also very available, in line with the one child policy.26 Although sex selective abortion is illegal, proving that an abortion has been carried out on sex selective as opposed to family planning grounds is often difficult when abortion itself is so readily available.21

Role of one child policy

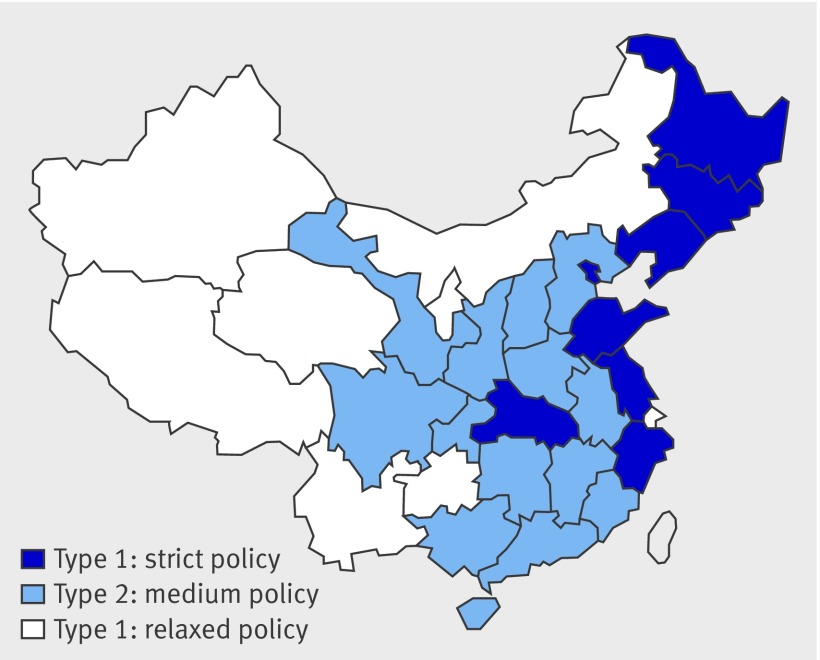

The relation between the sex ratio and the one child policy is a complex one. This study covers births taking place after the policy was instigated, so the increase in sex ratio that we document across age cohorts born in the past 20 years cannot be blamed on the policy in itself. However, the policy is implemented differently across the country (fig 2), and our data do suggest that the sex ratio is related to the way in which the policy is implemented.15 Whereas in most cities only one child is allowed, three main variants of the policy exist in rural areas. Type 1 provinces are most restrictive—around 40% of couples are allowed a second child but generally only if the first is a girl. In type 2 provinces everyone is allowed a second child if the first is a girl or if parents with one child experience “hardship,” the definition of which is open to interpretation by local officials. Type 3 provinces are most permissive, allowing couples a second child and sometimes a third, irrespective of sex. Our data show that the type 2 variant, which allows couples a second child after a girl, results in the highest sex ratios for second order births and the overall highest sex ratios, as seen in Henan, Anhui, Jiangxi, Hunan, Guangdong, and Hainan. These are largely more traditional, predominantly agricultural provinces, where bearing sons is still seen as necessary for long term security.21 29

Fig 2 Variation in implementation of the one child policy15

Medium sex ratios were most common in the strict type 1 provinces. However, these provinces are also wealthier, levels of education are higher, especially among women, traditional values of preference for sons are changing, and more people have pensions making them less dependent on sons to provide security in old age.30 A study in 2001 showed that more than 50% of women of reproductive age in such provinces express no preference for a son.31 The lowest (most normal) ratios are seen in the type 3, most permissive, provinces, such as Tibet, Xinjiang, and Ningxia. However, these provinces are also sparsely populated and poor, inhabited partly by ethnic groups who are generally less inclined to prefer sons and less accepting of abortion.29

This analysis is inevitably simplistic, given intra-provincial diversity, but the findings do point to the tendency for the type 2 variant of the policy to result in high sex ratios. The policy implications are clear: changing the regulations in force in type 2 provinces, which permit most couples a second child after a female birth, could help to reduce the sex ratio. Indeed, some commentators have gone further: now that the fertility rate is below replacement, some have recommended that all couples should be allowed two children irrespective of sex,30 31 32 and relaxation of the policy is expected over the next decade.

Although some imaginative and extreme solutions have been suggested,33 34 nothing can be done now to prevent this imminent generation of excess men. The government is very aware of the problem and has openly expressed concerns about the consequences of large numbers of excess men for societal stability and security.22 As early as 2000 the government launched a range of policies to specifically counter the sex imbalance, the “care for girls” campaign. This includes changes in laws in areas such as inheritance by females, as well as an educational campaign to promote gender equality. These measures have had some success, with reports of lower sex ratios at birth in targeted localities.22 This shows that change is occurring. In addition, the finding that the sex ratio at birth did not increase between 2000 and 2005, and that the ratio for the first (and usually only) birth in many urban areas is within normal limits, means that the sex ratio may fall in the foreseeable future.

What is already known on this topic

The reported sex ratio (males per 100 females) in China is high, but accurate population based figures for actual sex ratios have been notoriously difficult to obtain

The role of sex selective abortion and the influence of the one child policy on the sex imbalance have been unclear

What this study adds

China will see very high and steadily worsening sex ratios in the reproductive age group for the next two decades

Sex selective abortion accounts for almost all the excess males

One particular variant of the one child policy leads to the highest sex ratios

Contributors: All the authors participated in the analysis and in preparing the tables and saw and approved the final version of the paper. ZWX is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded through a China-UK excellence fellowship for TH from the Department of Innovation, Universities and Skills.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b1211

References

- 1.James WH. The human sex ratio. Part 1: a review of the literature. Human Biology 1987;59:721-5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teitelbaum M. Factors affecting the sex ratio in large populations. J Bio Sci 1970:2:61-71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Arnold F. The effect of son preference on fertility and family planning: empirical evidence. Popul Bull UN 1987;23:44-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klasen S, Wink C. A turning point in gender bias in mortality? An update on the number of missing women. Popul Dev Rev 2002;28:285-312. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen A. Missing women revisited. BMJ 2003;327:1297-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hesketh T, Zhu WX. Abnormal sex ratios in human populations: causes and consequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:13271-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park CB, Cho NH. Consequences of son preference in a low fertility society: imbalance of the sex ratio at birth in Korea. Popul Dev Rev 1995;21:59-84. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu B, Roy K. Sex ratio at birth in China, with reference to other areas in East Asia: what we know. Asia Pac Popul J 1995;10:17-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Short SE, Zhai FY. Looking locally at China’s one-child policy. Stud Fam Plan 1998;29,4:373-87. [PubMed]

- 10.Merli MG, Raftery AE. Are births underreported in rural china? Manipulation of statistical records in response to China’s population policies. Demography 2000;37:109-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Banister J. Shortage of girls in China today. J Popul Res 2004;21:19-45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson S, Nygren O. The missing girls of China: a new demographic account. Popul Dev Rev 1991;17:35-51. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng Y, Tu P, Gu B, Xu L, Li B, Li Y. Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birth in China. Popul Dev Rev 1993;19:283-302. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coale A. Excess female mortality and the balance of the sexes in the population: an estimate of the number of missing females. Popul Dev Rev 1991;17:518. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attane I. China’s family planning policy: an overview of its past and future. Stud Fam Plan 2002;33:103-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang W, Li X, Cui H. China’s intercensus survey in 2005. Beijing: China Population Publishing House, 2007.

- 17.Ulizzi L, Astolfi P, Zonta LA. Sex ratio at reproductive age: changes over the last century in the Italian population. Hum Biol 2001;73:121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.China-Profile. Facts, figures, and analyses. www.china-profile.com.

- 19.Wu Z, Viisainen K, Hemminki E. Determinants of high sex ratio among newborns: a cohort study from rural Anhui Province. Reprod Health Matters 2006;14:172-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lofstedt P, Luo SS, Johansson A. Abortion patterns and reported sex ratio in rural Yunnan, China. Reprod Health Matters 2004;12:86-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu JH. Prenatal sex determination and sex-selective abortion in rural central China. Popul Dev Rev 2001;27:259-81. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S. Imbalanced sex ratio at birth and comprehensive intervention in China. Presentation at 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health and Rights, Hyderabad, 29-31 October 2007. Available at www.unfpa.org/gender/docs/studies/china.pdf.

- 23.China Population Information and Research Centre. Basic population data of China: 1949-2000. www.cpirc.org.cn.

- 24.Hesketh T, Zhu WX. The one child family policy: the good, the bad and the ugly. BMJ 1997;314:1685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu ZC, Viisainen K, Wang Y, Hemminki E. Perinatal mortality in rural China: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2003;327:1319-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hemminki E, Wu ZC, Cao GY. Illegal births and legal abortions—the case of China. Reprod Health Matters 2005;2:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Zhu C, Feldman M. Gender differences in child survival in contemporary rural China: a county study. J Biosoc Sci 2004;36:83-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jha P, Kumar R, Vasa P, Dhingra N. Thirichelvam D, Moineddan R. Low male to female sex ratio of children born in India: national survey of 1.1 million households. Lancet 2006:367:211-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Li R. An analysis of the sex ratio at birth in impoverished areas in China. Chin J Popul Sci 1998;10:65-73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Winkler EA. Chinese reproductive policy at the turn of the millennium: dynamic stability. Popul Dev Rev 2002;28:379-418. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qu JD, Hesketh T. Family size, sex ratio and fertility preferences in the era of the one child family policy: results from the national family planning and reproductive health survey. BMJ 2006;333:371-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng Y. Options for fertility policy transition in China. Popul Dev Rev 2007;33:215-46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuljapurkar S, Li N, Feldman MW. High sex ratios in China’s future. Science 1995;267:874-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hudson V, Den Boer AM. A surplus of men, a deficit of peace: security and sex ratios in Asia’s largest states. Int Secur 2002;4:5-38. [Google Scholar]