Abstract

In this article, we investigate the contributions of actin filaments and accessory proteins to apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis in primary rabbit lacrimal acini. Confocal fluorescence and electron microscopy revealed that cytochalasin D promoted apical accumulation of clathrin, α-adaptin, dynamin, and F-actin and increased the amounts of coated pits and vesicles at the apical plasma membrane. Sorbitol density gradient analysis of membrane compartments showed that cytochalasin D increased [14C]dextran association with apical membranes from stimulated acini, consistent with functional inhibition of apical endocytosis. Recombinant syndapin SH3 domains interacted with lacrimal acinar dynamin, neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein (N-WASP), and synaptojanin; their introduction by electroporation elicited remarkable accumulation of clathrin, accessory proteins, and coated pits at the apical plasma membrane. These SH3 domains also significantly (p ≤ 0.05) increased F-actin, with substantial colocalization of dynamin and N-WASP with the additional filaments. Coelectroporation with the VCA domain of N-WASP blocked the increase in F-actin and reversed the morphological changes indicative of impaired apical endocytosis. We suggest that transient modulation of actin polymerization by syndapins through activation of the Arp2/3 complex via N-WASP coordinates dynamin-mediated vesicle fission at the apical plasma membrane of acinar epithelia. Trapping of assembled F-actin intermediates during this process by cytochalasin D or syndapin SH3 domains impairs endocytosis.

INTRODUCTION

The acinar cells of the lacrimal gland are the principal source of tear proteins released into nascent tear fluid (Fullard, 1994). Apical release of these materials from 1- to 3-μm secretory vesicles (SVs) is accelerated by activation of various signaling pathways, including diacylglycerol/Ca2+-dependent and cAMP-dependent pathways (Dartt, 1994). A constant traffic of transcytotic vesicles enriched in immunoglobulins, such as dimeric IgA is also accelerated by secretagogues (Schechter et al., 2002). The influx of transcytotic vesicles and the additional fusion of large mature SVs to the small area constituting the apical plasma membrane (APM) require a robust rate of apical endocytosis in resting and stimulated acini. Little is known about the molecular effectors responsible for this process in lacrimal acini or other acinar epithelial cells.

Several different processes are known to mediate internalization of plasma membrane and extracellular materials. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, the best characterized of these processes, occurs through a series of sequential events (reviewed in Brodsky et al., 2001). Very simply, clathrin coats are recruited to specific regions of the plasma membrane by adapter protein 2 complexes, which recognize internalization signals present on membrane proteins. Recruitment and clathrin cage assembly results in membrane deformation and invagination to form a clathrin-coated pit. Although the precise mechanisms remain unclear, the GTPase dynamin is thought to assemble in rings around the neck of the coated pit (Hinshaw and Schmid, 1995), facilitating separation of the pit from the membrane (reviewed in Danino and Hinshaw, 2001).

This simple view of clathrin-mediated endocytosis has recently undergone major modifications, due to the identification of a host of new so-called accessory proteins that seem to further orchestrate these endocytic events (Qualmann et al., 2000; Slepnev and De Camilli, 2000; Schafer 2002). Among these are the phosphoinositide phosphatase synaptojanin (McPherson et al., 1996) and syndapins (Qualmann et al., 1999). Synaptojanin modulates levels of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2), which in turn regulates a host of trafficking events, including recruitment of adapters and cargo to membranes and the pinching off and the uncoating of clathrin-coated vesicles (Cremona et al., 1999; reviewed in Toker, 1998; Martin, 2001). Additionally, synaptojanin and PIP2 have been implicated in endocytosis by regulation of actin-dependent dynamics and rearrangement in mammalian cells through their binding to proteins that control actin dynamics (Sakisaka et al., 1997; Sechi and Wehland, 2000). Syndapins belong to a small group of proteins thought to link endocytosis to the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in Qualmann and Kessels, 2002) and include syndapin I, which is highly enriched in brain (Qualmann et al., 1999), and the ubiquitously expressed syndapin II (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). Syndapins interact with the proline-rich domain (PRD) of dynamin via their C-terminal src homology 3 (SH3) domains; consequently, the syndapin SH3 domains can be used as powerful dominant-negative tools for blocking receptor-mediated endocytosis in vivo. Syndapins also have known interactions with the actin cytoskeleton through their demonstrated association with synaptojanins and the neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome Protein (N-WASP) (Qualmann et al., 1999; Qualmann and Kelly, 2000), a ubiquitously expressed protein and a potent activator of the Arp2/3 complex actin polymerization machinery (Higgs and Pollard, 2001; Machesky and Insall, 1999).

Here, we present data obtained by functional and morphological studies that apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis in secretory epithelial cells from rabbit lacrimal gland is dependent upon normal apical actin dynamics. Our data further suggest that control of dynamin-mediated vesicle fission and transient activation of Arp2/3 complex-dependent actin polymerization via N-WASP play important roles in apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis in lacrimal acini, with these two molecular machineries likely being functionally linked and coordinated by their common interaction partner, syndapin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials and Supplies

Carbachol (CCH), ionomycin, rhodamine-phalloidin, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary antibodies, mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb) to α-adaptin, rabbit polyclonal antibody to glutathione S-transferase (GST), protease inhibitors (Yang et al., 1999), and 14C-methylated dextran (mol. wt. 10,000; specific activity 2–3.1 mCi/g) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cytochalasin D (CD) was obtained from Alexis Biochemicals (Carlsbad, CA). Mouse mAb to dynamin was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, KY). The X-22 anti-clathrin antibody used for immunofluorescence was purified from the hybridoma (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA) by using Gamma-Bind Sepharose (Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ). The mouse monoclonal clathrin heavy chain antibody used for Western blotting was obtained from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Rabbit polyclonal antibody to rab3D was generated against recombinant mouse rab3D (Antibodies, Davis CA) and purified using protein A/G agarose. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to syndapins I and II were generated and affinity purified as described previously (Qualmann et al., 1999; Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). Polyclonal anti-N-WASP antibodies were raised in rabbit (Alpha Diagnostic, San Antonio, TX) against a purified GST-fusion protein of amino acid residues 118–273 of rat N-WASP. Antibodies were depleted against GST and subsequently affinity purified on GST-N-WASP (118–273) blotted to nitrocellulose membranes. FITC-dextran and mounting medium were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Goat anti-rabbit and anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ). Matrigel was from Collaborative Research (Bedford, MA). The mouse mAb to synaptojanin I was provided by Dr. Pietro De Camilli (Yale University, New Haven, CT). Mouse epidermal growth factor (EGF) (Sigma-Aldrich) was iodinated by incubation with 125I-NaI, glucose, and glucose oxidase for 1 min in the presence of lactoperoxidase. The iodinated product was isolated by chromatography over BioGel 60 and stored at -20°C. Recovery rates exceeded 95%, and the specific activity was 35–40 μCi/μg.

Cell Culture

Female New Zealand White rabbits were obtained from Irish Farms (Norco, CA), and lacrimal gland acinar cells were isolated and cultured for 2–3 d as described previously (Hamm-Alvarez et al., 1997; da Costa et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2003). All animal studies were in accordance with the Guiding Principles for Use of Animals in Research. Treatments included CD (5 μM, 60 min, 37°C) with and without carbachol (CCH) (100 μM, 5–15 min) or ionomycin (1 μM, 5–15 min). Electron microscopy (EM) analysis of apical actin used lacrimal acini reconstituted on Matrigel rafts as described previously (Schechter et al., 2002).

Confocal Fluorescence and Electron Microscopy

For detection of α-adaptin, dynamin, syndapin II, synaptojanin-I, and N-WASP, lacrimal acini cultured on Matrigel-coated coverslips were rinsed in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS), fixed, and permeabilized with ice-cold ethanol (-20°C, 5 min) and blocked with 1% bovine serum in DPBS as described previously (Wang et al., 2003). For detection of clathrin, lacrimal acini were extracted with 0.02% saponin before fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde and processing as described previously (da Costa et al., 1998). All samples were then exposed to appropriate primary and secondary FITC-conjugated antibodies or affinity label. Samples were imaged using a Nikon PCM confocal system equipped with Argon ion and green HeNe lasers attached to a Nikon TE300 Quantum inverted microscope and acquired using Simple PCI software.

For quantitation of F-actin labeling intensity, acini of comparable size and thickness labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin were selected for confocal microscopy z-scanning. Images were acquired at equal gain and contrast intensities, pinhole size, image section thickness (0.6 μm), and zoom (2× zoom magnification, 60× objective). Initial gain and contrast levels were established using control and electroporated samples to ensure that fluorescence levels were not saturated. Ten z-plane sections, per acinus, were acquired, with intervals representing ∼1 μm. Image fluorescence, measured by pixel intensity, was analyzed using MetaMorph data analysis software as follows: of the 10 acquired z-plane sections, the first and last sections were discarded to avoid imaging very small surface areas of the acinus (top) and/or stress fibers (bottom). The total pixel intensity of the remaining individual z-section images was quantified and normalized to the area of the acinus (determined by drawing a line around the perimeter as shown in Figure 9). The final fluorescence intensity value per acinus was determined by summation of each of the eight z-section images (the eight z-section images ( F.I./area).

F.I./area).

Figure 9.

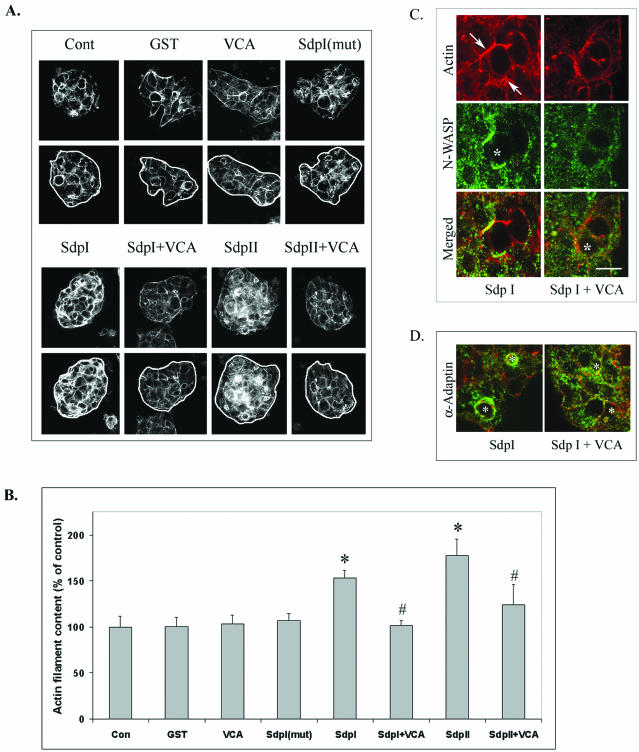

Analysis of F-actin content in acini electroporated with GST fusion proteins. (A) Representative serial sections of acini electroporated without (control) or with GST fusion proteins as indicated and then fixed and labeled with rhodamine-phalloidin. Sections depicted for each treatment were acquired at ≅1-μm intervals and are representative of the serial sectioning used for quantitative analysis (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). (B) Quantitation of the intensity of actin filament labeling under each condition was obtained using MetaMorph Quantitation Software as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS (10 images/acinus, four acini, and 160 images total/treatment, n = 3–6 separate preparations; *p ≤ 0.05, Bar, ∼10 μm). Distribution of N-WASP (green) in parallel with actin filaments (red) (C) and distribution of α-adaptin (green) in parallel with actin filaments (red) (D) as detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy in resting acini electroporated with syndapin I SH3 domains without (left) or with (right) the GST-VCA fusion protein. Apical/lumenal regions are identified in each panel by *. Arrows depict the accumulation of N-WASP with additional F-actin structures formed in acini electroporated with the syndapin I SH3 domain. Bars, ∼10 μm.

A similar method was used to quantify the fluorescence intensity associated with α-adaptin accumulation beneath the APM in confocal fluorescence microscopy images acquired at equal gain and contrast intensities from control and treated acini. Each image (of a section within an acinus) contained approximately four to eight lumens. After identification of the lumen using rhodamine-phalloidin to label the underlying actin filaments, the subapical cytoplasm was outlined, including a region ∼1–2 μm from the border delineated by apical actin. Pixel intensity within that region was quantified by MetaMorph imaging software and the total pixel intensity was normalized to lumenal perimeter. All lumena contained in acquired images were assayed. Normalized values of α-adaptin labeling in treated acini were expressed as a percentage of the labeling detected in controls.

For EM, acini cultured on Matrigel-coated Biocoat Transwell plates (BD Biosciences) or in raft cultures were processed as described previously (Schechter et al., 2002). Samples were analyzed using a 1200 EX transmission electron microscope (JOEL, Tokyo, Japan). Quantitation of coated pits and vesicles in EM images was as follows: APM regions were chosen at random and acquired at equal magnification. Clathrin-coated pits or vesicles in each image were identified based on their characteristic electron dense appearance: pits were defined as electron dense structures in apparent continuum with the APM, whereas vesicles were defined as electron-dense structures within ∼150–200 nm of the APM. The total number of coated pits and/or vesicles in each image was quantified, summed, and normalized to the total length of APM determined using MetaMorph Image quantitation software. Confocal and EM panels were compiled using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View CA).

Subcellular Fractionation Analysis

Subcellular fractionation analyses on isopycnic sorbitol density gradients to identify membrane compartment distributions of 125I-EGF (200 ng/ml, 35–40 μCi/μg) and [14C]dextran (1.1–1.5 mg/ml, 2.0–3.1 mCi/g) were performed in lacrimal acini treated with and without CD (5 μM, 60 min) and, for [14C]dextran only, with and without CCH (100 μM, 15 min) as described previously (Gierow et al., 1996; Hamm-Alvarez et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003). The gradient contents were collected in 12 fractions, diluted with sorbitol cell lysis buffer, and centrifuged at 250,000 × g for 90 min at 4°. Resulting pellets, as well as the pellets forming beneath the density gradients, were resuspended in 0.5-ml aliquots of the sorbitol cell lysis buffer and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before storage at -80°C. Enzymatic markers and protein were determined as described previously (Gierow et al., 1996; Hamm-Alvarez et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003). Contents of individual density gradient fractions were expressed as percentages of the totals summed >13 fractions.

A fraction enriched in APM was isolated from rabbit lacrimal glands based on established procedures with MgSO4 to aggregate APM (Aronson, 1978; Mircheff and Lu, 1984). After isolation of the aggregates by centrifugation at 30,000 × g, 4°C for 30 min, the enriched APM fraction was resuspended in 5% sorbitol buffer and further analyzed by centrifugation over isopycnic sorbitol density gradients.

Generation and Use of Recombinant Proteins

Plasmids encoding the SH3 domains of syndapins I (residues 376–441) and II (residues 419–488) and a mutated form of the SH3 domain of syndapin I (P434L) as fusion proteins with GST were generated as described previously (Qualmann et al., 1999; Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). GST for additional control experiments was expressed from plasmid pGEX-2T. GST and GST-fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells and purified using glutathione agarose or Sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) as described previously (Qualmann et al., 1999; Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). A construct encoding a GST-fusion protein of the C-terminal part of rat N-WASP (residues 391–501, N-WASP-VCA) was generated by polymerase chain reaction with rat N-WASP cDNA as a template. The polymerase chain reaction-product was cloned into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of the pGEX-5 × 1 vector (Pharmacia).

For isolation of lacrimal acinar proteins with binding affinity for syndapin SH3 domains, acini (3.0 × 107 cells/sample) were resuspended in binding buffer, lysed by freeze/thaw and processed to obtain a high-speed supernatant by low-speed (14,000 rpm, 10 min, 4°C) and then high-speed (100,000 × g, 15 min, 4°C) centrifugation. Preloading of glutathione-uniflow resin with 75 μg of either GST or GST-fusion proteins was for 5 h at 4°C (with end-over-end rotation) followed by extensive rinsing in DPBS and binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100 plus protease inhibitor cocktail). High-speed acinar supernatant was then incubated with glutathione-uniflow resin (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) preloaded without or with GST or GST fusion proteins overnight with end-over-end rotation at 4°C. Proteins were eluted from beads into sample buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and proteins of interest analyzed by Western blotting.

Electroporation of Rabbit Lacrimal Acini

Cultured lacrimal acini were gently pelleted and resuspended in fresh medium at a concentration of 3.0–4.5 × 107 cells/0.5 ml medium and placed into a cuvette for electroporation (Gene Pulser Cuvette, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA; 0.4-cm electrode gap, 50–250 V, 600- to 960-μF capacitance). Pulse lengths ranged from 11 to 20 ms. Electroporation efficiency (>90% in each assay) was confirmed in each experiment by electroporation with β-galactosidase and phase microscopy to detect colorimetric production with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactoside as substrate. The concentration of GST and GST fusion proteins during electroporation was 10 μM. After electroporation, cells were kept on ice for 5–10 min before seeding onto Matrigel-coated coverslips or Transwell dishes, incubation for 3 h at 37°C, and analysis by fluorescence microscopy or EM.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t tests assuming equal variances were used for analysis of biochemical data from density gradient analyses. Paired Student's t tests were used for comparison of actin filament content using data obtained by MetaMorph analysis. Values of p ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

CD Promotes Accumulation of Clathrin and Accessory Proteins to Actin-enriched Regions Beneath the APM

To begin to probe the mechanisms responsible for retrieval of APM in lacrimal acini, we investigated the changes in the enrichment of clathrin, α-adaptin, and dynamin at the APM under different experimental conditions. As shown in Figure 1 (red), the apical enrichment of actin filaments associated with the dense subapical actin network and apical microvilli resulted in a dense accumulation of lumenal F-actin (*, top left), enabling easy identification of apical/lumenal regions within the reconstituted lacrimal acini. Fainter labeling was associated with actin filaments at basolateral membranes (large arrow, top left). The paired image indicates the α-adaptin distribution (green) in a punctate pattern in resting acini with traces detected with apical and basolateral membranes.

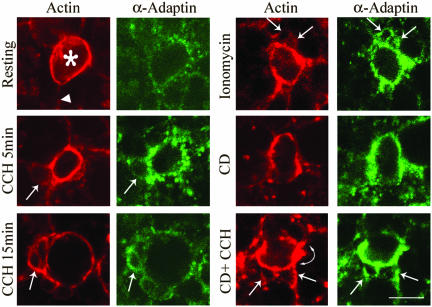

Figure 1.

CD promotes accumulation of α-adaptin at the APM of lacrimal acini. The intracellular distribution of α-adaptin (green) in control and stimulated acini with and without CD was investigated using anti-α-adaptin primary and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies and detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy. F-Actin organization (red) was probed in parallel in each sample using rhodamine-phalloidin. Top left, representative lumenal region (*) surrounded by APM underlaid with abundant apical actin filaments and fainter labeling indicative of basolateral actin (large arrow). Treatments included 100 μM CCH for either 5 or 15 min without or with CD (5 μM, 60 min) or 1 μM ionomycin for 5 min. Small arrows in paired images denote sites of accumulation of actin-coated SVs and α-adaptin. Arrowhead indicates basolateral actin and curved arrow denotes regions of apparent actin accumulation. Bar, ∼10 μm.

CCH stimulation (100 μM, 5 min) resulted in a dramatic increase in the intensity of α-adaptin labeling beneath the actin-enriched APM and actin-coated invaginations formed in response to stimulation (Figure 1, small arrows), which was verified by quantitative image analysis of multiple confocal images (Table 1). These invaginations likely represent fusing actin-coated SVs. Our observations suggest that clathrin-mediated endocytosis is enhanced in regions undergoing exocytosis. Ionomycin, which directly elevates intracellular calcium, elicited a comparable accumulation of α-adaptin beneath the actin-enriched APM and actin-coated SVs (Figure 1, small arrows), again verified by quantitative analysis of multiple confocal images (Table 1). Comparable stimulation-induced accumulation beneath the APM was noted for clathrin and dynamin (Figure 2, small arrows).

Table 1.

Quantitation of the intensity of α-adaptin labeling beneath the apical plasma membrane of lacrimal acini

| Treatment | % of Control | Lumens |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 100 | 207 (n = 2—6) |

| CCH 5 min | 147 ± 6 | 51 (n = 6) |

| CCH 15 min | 101 ± 4 | 32 (n = 3) |

| Ionomycin 5 min | 145 ± 3 | 111 (n = 2) |

| Ionomycin 15 min | 105 ± 1 | 96 (n = 2) |

| CD | 156 ± 4 | 78 (n = 4) |

| EPO Control | 100 | 48 (n = 3) |

| EPO Sdp I (mut) | 128 ± 6 | 27 (n = 3) |

| EPO Sdp I | 200 ± 1 | 55 (n = 3) |

| EPO Sdp II | 194 ± 11 | 36 (n = 3) |

EPO, electroporated.

Fluorescence pixel intensity associated with α-adaptin immunofluorescence beneath the APM region of lacrimal acini was quantified by MetaMorph Image analysis software, and pixel intensity was normalized to the lumenal perimeter (see MATERIALS AND METHODS). Experimental treatments are expressed as a percentage of values obtained for controls ± SEM. n values for lumena counted in control and EPO control represent the total lumena counted across all treatments or electroporation samples. The specific number of control preparations quantified with each experimental treatment varied, because controls and treatments were matched.

Figure 2.

CD promotes accumulation of clathrin and dynamin at the APM of lacrimal acini. The intracellular distributions of clathrin or dynamin (green) in control and CCH-stimulated acini with and without CD were investigated using appropriate primary and FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies and detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy. F-Actin organization (red) was probed in parallel in each sample by using rhodamine-phalloidin. Apical/lumenal regions are identified by the enrichment of F-actin, denoted by (*) in the top left image. Treatments included 100 μM CCH for either 5 or 15 min without or with CD (5 μM, 60 min). Small arrows indicate apparent accumulation of clathrin or dynamin beneath apparent actin-coated SVs, arrowheads denote regions of apparent actin fragmentation associated with CD, and curved arrow denotes regions of apparent actin accumulation. Bar, ∼10 μm.

Although these proteins were also detected with basolateral membranes after CCH treatment, confocal Z-sectioning failed to reveal enrichment comparable with that seen at the APM (our unpublished data). This observation is consistent with previous reports that basolateral endocytosis in lacrimal acini is maximally accelerated at lower doses of CCH (Gierow et al., 1995). Analysis of the time course of CCH stimulation revealed that by 15 min, the labeling patterns for clathrin, α-adaptin, and dynamin resembled the resting state (Figures 1 and 2 and Table 1), with a similar recovery noted for ionomycin (Table 1). The pattern of apical recruitment of clathrin and clathrin-associated proteins at early time points and retrieval after 15 min correlates with previous studies showing rapid (5–10 min) CCH-induced release of secretory products followed by slower release from 10 to 60 min (da Costa et al., 1998).

The fungal metabolite CD has been shown to cap the ends of actin filaments and to participate in monomer sequestration and actin filament severing, resulting in filament shortening and fragmentation (Cooper, 1987). Confocal fluorescence microscopy revealed that CD treatment caused fragmentation of basolateral actin filaments into phalloidinstainable punctate structures as well as discontinuities in apical actin filaments (Figures 1 and 2, arrowheads). Interestingly, the remaining apical actin filaments seemed more intensely labeled (Figures 1 and 2, curved arrows), suggesting possible CD-induced accumulation of F-actin at some apical sites.

CD treatment without CCH caused a pronounced accumulation of α-adaptin (Figure 1 and Table 1), clathrin (Figure 2) and dynamin (Figure 2) at the APM that seemed just as intense as in CCH-stimulated acini and was localized beneath apical actin accumulations. In contrast to the normal retrieval of these proteins from the APM after 15 min of CCH stimulation, pretreatment with CD before CCH prevented the retrieval of clathrin, α-adaptin and dynamin from the apical membrane, as indicated by their continued intense apical localization (Figures 1 and 2).

CD-induced Increases in Apical Actin Are Associated with Accumulation of Coated Pits and Vesicles at the APM

We used EM to further examine the distribution of coated pits and coated vesicles at the APM of lacrimal acini under different experimental conditions. EM analysis of control samples revealed that the apical cytoplasm of lacrimal acini frequently included clusters of pleomorphic large SVs (Figure 3, A and C). Actin filaments could be detected periodically beneath the APM and in some cases, around large mature SVs (Figure 3A, arrows). Interestingly, CD treatment resulted in a notable increase in apparent actin bundles (Figure 3, C and C′, arrows) in regions beneath the APM. Further analysis of subcellular actin pools in resting and CD-treated acini by using selective detergent extraction (Wang et al., 2003) showed that CD did not significantly reduce the filamentous actin pool: filamentous actin constituted 57 ± 2 and 50 ± 4% of the total actin pool in untreated and CD-treated acini, respectively (n = 4). Collectively, these findings suggest that CD elicits accumulation or bundling of apical actin, while concomitantly decreasing basolateral actin.

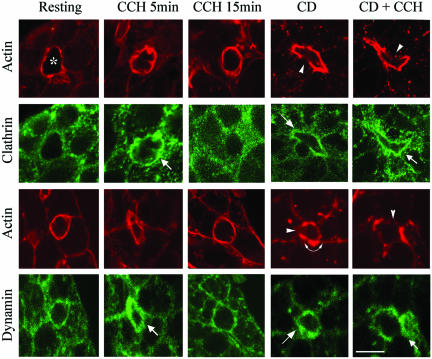

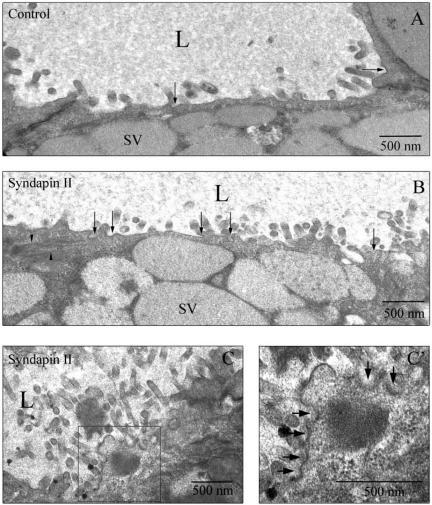

Figure 3.

CD increases coated pits at the APM of lacrimal acini while also bundling some apical actin filaments. Resting acini (A) and acini exposed to CD (5 μM, 60 min) with (B) or without (C) CCH stimulation (100 μM, 15 min). Acini were cultured on Matrigel rafts and processed for EM as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Lumena (L) are enriched in mature SVs and filamentous structures (arrows), which are likely to be actin filaments. Apparent coated pits and coated vesicles (arrowheads) are detected in trace amounts in resting acini (A, A′) acini but are increased dramatically in CD-treated acini (C and C′). Exposure of CD-treated acini to CCH also resulted in accumulation of coated pits and vesicles (arrowheads) in regions apparently undergoing exocytosis and enriched in actin filaments (arrows) (B).

Analysis of regions of APM from control and CD-treated lacrimal acini imaged at higher magnification revealed a relatively sparse complement of coated pits and vesicles in resting acini (Figure 3A′); one apparent coated pit or vesicle is shown here (arrowhead) at the base of a microvillus. In contrast, CD treatment elicited a striking increase in coated pits and vesicles at the APM (Figure 3C′, arrowheads). In acini exposed to CD then stimulated with CCH, accumulations of coated pit intermediates (Figure 3B, arrowheads) were detected in deep invaginations of the APM, which were likely formed at sites of CCH-induced fusion of large mature SVs. These sites were likewise enriched in actin filaments (Figure 3B, arrows). Accumulations of coated pits were also detected in more continuous regions of the APM in acini exposed to CD + CCH (our unpublished data). These data verify that the CD-induced accumulation of clathrin, α-adaptin, and dynamin is associated with trapping of coated pit intermediates at the APM, an effect correlated with the accumulation of apical actin filaments.

CD Traps [14C]Dextran with APM Fractions

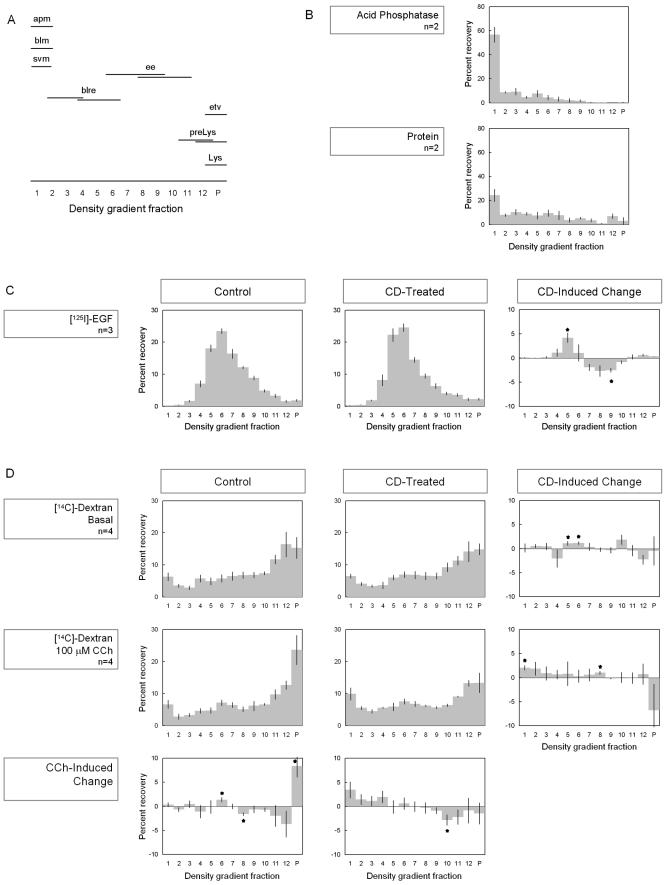

Little is known about the identity of the proteins retrieved by apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis in lacrimal acini. Lacking a specific marker, we analyzed the subcellular membrane distribution of [14C]dextran, which is internalized through adsorption to bulk membranes at apical and basolateral surfaces. Some bulk membrane internalization occurs via clathrin-mediated processes, so a component of [14C]dextran internalization at apical and basolateral membranes occurs through clathrin-mediated endocytosis. We have previously characterized other trafficking events between membrane compartments by using isopycnic separation of acinar membrane compartments over sorbitol density gradients (Gierow et al., 1996; Hamm-Alvarez et al., 1997; Yang et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2003); Figure 4A presents our working model for the density gradient locations of compartments involved in endocytosis from APM and basolateral membranes.

Figure 4.

CD increases association of [14C]dextran with APM fractions. (A) Working model for isolation of acinar plasma membrane and endocytic membrane compartments over sorbitol density gradients (apm, apical plasma membrane; blm, basolateral membrane; svm, SV membrane; blre, basolateral recycling endosome; ee, early endosome; etv, endocytic transport vesicle; preLys, prelysosome; Lys, lysosome). (B) Lacrimal glands were homogenized and subjected to Mg2+ precipitation of APM, and the resulting membrane sample was processed by isopycnic centrifugation on sorbitol density gradients and fractions analyzed for protein and acid phosphatase activity. (C) 125I-EGF content of membrane fractions isolated by isopycnic centrifugation on sorbitol density gradients from resting acini or acini exposed to CD (5 μM, 60 min). The right column shows the CD-induced change. (D) [14C]Dextran content of membrane fractions isolated by isopycnic centrifugation on sorbitol density gradients from resting and CCH-stimulated acini (100 μm, 15 min) with and without CD (5 μM, 60 min). The right column shows the CD-induced change, whereas the bottom row shows the CCH-induced change. n = 2–4 preparations as indicated; error bars represent SEM; *p ≤ 0.05.

To determine the density gradient location of the APM compartment, APM fractions were first isolated by Mg2+ precipitation and then analyzed by centrifugation over sorbitol density gradients (Aronson, 1978; Mircheff and Lu, 1984). Figure 4B illustrates the resulting distributions of protein and acid phosphatase. In lacrimal acinar cells, acid phosphatase is associated with a series of compartments related to plasma membrane recycling. Components of the acid activity have been recognized to be present in the basolateral plasma membrane, early endosome, recycling endosome, and late endosome; additionally, relatively small components are associated with the Golgi complex, trans-Golgi Network, and lysosome (Qian et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2003). The results in Figure 4B demonstrate that the Mg2+ precipitation procedure substantially removes the endosomal, Golgi, trans-Golgi network, and lysosomal compartments and that acid phosphatase is highly enriched in the apical plasma membrane, located in density gradient fraction 1. When total microsomal fractions are analyzed on the same sorbitol density gradients, gradient fraction 1 also contains the basolateral membrane compartment (Gierow et al., 1996) and rab3D-enriched SV membrane fragments (Wang et al., 2003). We examined the effects of CD on uptake of 125I-EGF, a ligand internalized primarily by clathrin-mediated endocytosis at the basolateral membrane of lacrimal acini (Xie et al., 2002). CD did not alter the total uptake of 125I-EGF (Table 2). Figure 4C shows the distribution of internalized 125I-EGF in membrane compartments isolated by centrifugation over sorbitol density gradients in the presence and absence of CD. We have established that lacrimal acinar cells internalize EGF to an early endosome located in fractions 7–9 and accumulate it in a basolateral recycling endosome located in fractions 5–7, consistent with the major peak of 125I-EGF in this region (Xie et al., 2003). The changes elicited by CD are easily seen in the difference plot, showing significant CD-induced accumulation of 125I-EGF in fractions 5–7 and depletion in fractions 7–9; these findings suggest that CD alters the way internalized 125I-EGF partitions between the early endosome and the basolateral recycling endosome without affecting total amount taken up. We did not examine EGF uptake in acini stimulated with maximal (100 μM) CCH because 1) clathrin-mediated basolateral endocytosis of EGF is already accelerated by EGF binding to its receptor and 2) the CCH dose for maximal basolateral endocytosis is much <100 μM (Gierow et al., 1995).

Table 2.

Uptake of 125I-EGF and [14C]dextran in rabbit lacrimal acini

| Treatments | EGF (% of resting control) | Dextran (% of resting control) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 100 | 100 |

| Cytochalasin D | 102 ± 15 | 114 ± 26 |

| CCH | 244 ± 81 | |

| Cytochalasin D + CCH | 229 ± 50 |

For measurement of EGF uptake, control acini, and acini exposed to cytochalasin D (5 μM, 60 min) were exposed to 125I-EGF (200 ng/ml) and then rinsed and processed for scintillation counting. For measurement of [14C]dextran uptake, control acini, and acini exposed to cytochalasin D (5 μM, 60 min) were exposed to [14C]dextran (1.25 mg/ml) in the presence and absence of carbachol (100 μM, 15 min) and then rinsed and processed for scintillation counting. n = 3—4 experiments.

Because only a fraction of total [14C]dextran uptake was expected to occur by apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis, it was not surprising to find that CD did not significantly reduce total [14C]dextran uptake in lacrimal acini with or without CCH (Table 2). However, analysis of [14C]dextran enrichment with membrane compartments isolated by centrifugation over sorbitol density gradients revealed evidence for selective inhibition of CCH-stimulated apical endocytosis (Figure 4D). In contrast to 125I-EGF, which accumulates in the basolateral recycling endosome through a receptor-mediated process, [14C]dextran internalized in control acini was recovered across the density gradient and concentrated in higher density fractions enriched in prelysosomes and lysosomes. Apart from the small peak in fraction 1, the [14C]dextran distribution resembled that of endocytosed 125I-bovine serum albumin (our unpublished data). The disparity between [14C]dextran traffic and 125I-bovine serum albumin is consistent with parallel routes of uptake of both markers from both the apical and the basolateral surfaces, with the apical endocytosis of [14C]dextran preferentially enhanced by adsorption to APM glycoproteins and glycolipids. CCH stimulation caused a significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase of [14C]dextran accumulation in fraction P, suggesting that CCH induced production of a population of high-density endocytic transport vesicles. CD treatment prevented the CCH-induced accumulation of [14C]dextran in fraction P and instead caused a significant increase of [14C]dextran accumulation in fraction 1, the fraction enriched in APM (Figure 4B). These effects were not seen for 125I-EGF, which is preferentially internalized from the basolateral membranes. However, in unstimulated acini, CD caused a small but significant decrease of [14C]dextran accumulation in fractions 8 and 9, similar to the trend observed for EGF. These effects suggest that although CD does not alter [14C]dextran internalization from the basolateral surface, it does cause a subtle change in the organization of the recycling endosome that communicates with the basolateral surface. However, the effect of CD on endocytosis from the plasma membrane seems to be selective for apical endocytosis. CD-induced changes in membrane-associated actin did not cause nonspecific changes in sedimentation of membrane compartments over the density gradients, because the distribution of general membrane compartment markers was not altered in membranes from CD-treated acini (our unpublished data).

Evaluation of Syndapins I and II Abundance and Distribution

The accumulation of coated pits in CD-treated acini suggested that disruption of actin might affect vesicle formation. Budding and scission of coated pits into coated vesicles involves the GTPase dynamin. Several SH3-domain–containing proteins are known to interact both with dynamin's PRD and actin filaments, including syndapins (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000), Abp1 (Kessels et al., 2000) and cortactin (McNiven et al., 2000).

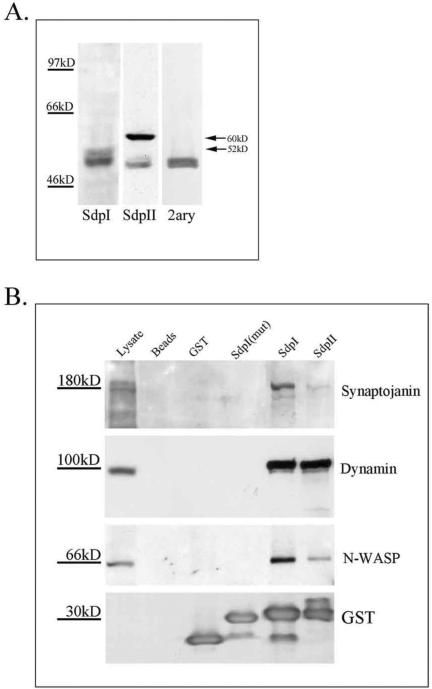

We detected both the brain-enriched syndapin I (Qualmann et al., 1999) and the ubiquitously expressed syndapin II (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000) in homogenates of rabbit acini by using isoform-specific polyclonal rabbit anti-syndapin antibodies (Figure 5A), although the analysis of the 52-kDa protein syndapin I was complicated by the fact that the secondary anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase conjugate additionally detected a 50-kDa band that may represent heavy chains of rabbit immunoglobulins present in the acinar homogenates. Comparison of the relative signal intensities suggested that syndapin II was more abundant in lacrimal acini than syndapin I.

Figure 5.

Syndapin I and II abundance and binding partners in acini. (A) SDS-PAGE of lacrimal gland acinar lysates (150 μg of protein/lane) and subsequent Western blotting with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies as indicated revealed bands at 5 and 60 kDa consistent with the presence of syndapins I and II, respectively, in lacrimal acini. The goat-anti rabbit secondary antibody (2ary) used for these Western blots reacts with a 50-kDa protein present in rabbit acinar lysates. (B) Affinity purifications of proteins interacting with the SH3 domains of syndapins I and II, the mutated SH3 domain of syndapin I, GST, and glutathione-agarose beads alone. Equal amounts of fusion proteins (75 μg of fusion protein/sample) and lacrimal acinar lysate (≅4.3 mg protein/sample) were used for each pull-down sample. Beads were resuspended in 150 μl of sample buffer, which also solubilized the GST fusion proteins associated with the beads, and 35 μl of sample was loaded in each case. Starting material (91 μg) was loaded for comparison. Western blots were probed with appropriate primary antibodies against synaptojanin, dynamin, N-WASP, and GST.

We asked whether the syndapin interaction partners dynamin, synaptojanin, and N-WASP were expressed in lacrimal acinar cells and would bind to syndapin I and II. As shown in Figure 5B, lacrimal acinar dynamin was affinity purified strongly in pull-down experiments by using GST-fusion proteins of the syndapin I and II SH3 domains, but not with an inactive mutated SH3 domain (P434L) from syndapin I (Qualmann et al., 1999), GST, or beads alone. Likewise, lacrimal acinar synaptojanin and N-WASP exhibited binding to syndapin I and II SH3 domains, but not with the mutated SH3 domain, GST, or beads alone. The content of recombinant protein eluted from the beads in the same sample is shown in the GST blot.

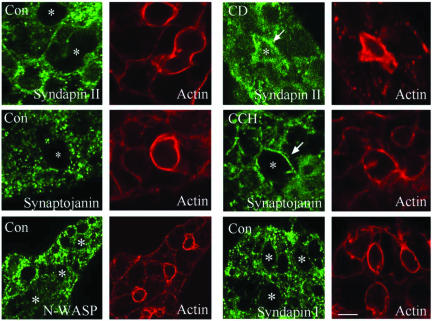

The distribution of syndapins, synaptojanin, and N-WASP in acini was evaluated by confocal fluorescence microscopy to see whether they were enriched in endocytic zones by CCH or CD, similar to clathrin and accessory proteins. Each protein could be detected in a punctate distribution throughout the cytoplasm of resting acini without any particular enrichment at apical or basolateral membranes (Figure 6, left and bottom right). Exposure of lacrimal acini to CD (5 μM, 60 min) increased the intensity of syndapin II labeling at the APM (Figure 6, arrow, top right); a similar enrichment was noted after 5 min CCH stimulation (our unpublished data). Synaptojanin was also enriched at the APM after 5 min CCH stimulation (Figure 6, arrow, mid-right) or CD treatment (our unpublished data). No detectable changes in syndapin I or N-WASP distributions accompanied CCH or CD (our unpublished data). The observation that syndapin II rather than syndapin I is recruited to the APM under conditions associated with accumulation of clathrin and accessory proteins suggests that this isoform may preferentially participate in apical endocytosis, consistent with previous suggestions that syndapins I and II play different roles within cells (Lanzetti et al., 2001).

Figure 6.

Distributions of syndapins I and II, synaptojanin-I, and N-WASP in acini. The distributions of syndapins I and II, synaptojanin, and N-WASP (green) were investigated using appropriate primary and fluorophoreconjugated secondary antibodies and detected by confocal fluorescence microscopy. F-actin organization (red, matched image) was probed in parallel in each sample by using rhodamine-phalloidin. The distribution of each of these proteins is shown in resting acini (Con), whereas the distribution of syndapin II in CD-treated acini (5 μM, 60 min) and the distribution of synaptojanin in CCH-treated acini (100 μM, 5 min) are also indicated. Enrichment of these proteins at the APM is indicated by arrows. Apical/lumenal regions are identified in each panel by *. Bar, ∼10 μm.

Syndapin I and II SH3 Domains Promote Accumulation of Clathrin and Accessory Proteins at the APM

The SH3 domains of syndapins I and II retain dynamin and N-WASP binding capabilities. We anticipated that introduction of these recombinant proteins would have dominant negative effects on endocytosis and/or actin filament organization, if in fact syndapins facilitated apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis in lacrimal acini. Fusion proteins of syndapin I and II SH3 domains with GST, as well as appropriate controls, were introduced into lacrimal acini by electroporation. Parallel electroporation of lacrimal acini with β-galactosidase revealed an electroporation efficiency >90% with no major losses in cell viability (our unpublished data). Confocal fluorescence microscopy of electroporated acini labeled with primary anti-GST antibodies and appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies revealed increased fluorescence intensity in acini electroporated with GST fusion proteins (our unpublished data). Introduction of GST-fusion proteins into lacrimal acini was also confirmed by washing of electroporated cells, preparation of lysates, and analysis by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting (our unpublished data).

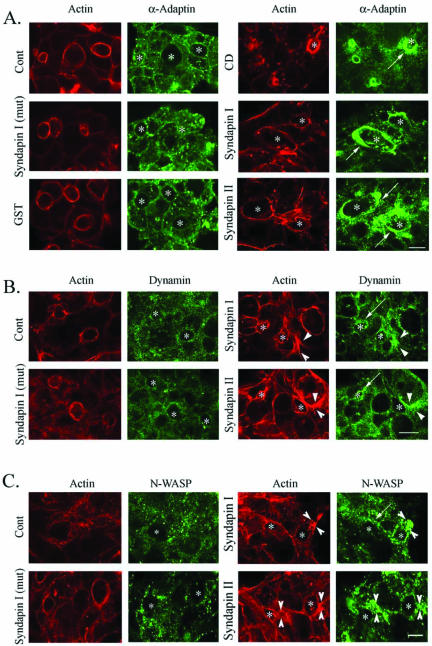

Introduction of the syndapin SH3 domains elicited a profound accumulation of α-adaptin (Figure 7A, arrows) at the APM, even in the absence of CCH stimulation and comparable with the effect of CD. No accumulation of α-adaptin was elicited in unstimulated acini electroporated with the mutated SH3 domain of syndapin I or with GST, suggesting that this effect was specific for the active SH3 domains of syndapins. Neither the mutated SH3 domain nor GST prevented CCH-induced recruitment of α-adaptin or clathrin to the APM (our unpublished data). These observations were verified by quantitative image analysis of subapical α-adaptin labeling intensity (Table 1). Clathrin labeling paralleled that of α-adaptin under these conditions (our unpublished data). Given the intense apical accumulation of these proteins in unstimulated acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains, we were unable to detect additional accumulation in CCH-stimulated acini, similar to the effects of CD treatment (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 7.

Syndapin SH3 domains elicit specific accumulation of α-adaptin and dynamin at the APM of acini. The distributions of α-adaptin (green, A), dynamin (green, B) and N-WASP (green, C) in parallel with actin filaments (red, all panels) in resting acini electroporated with GST fusion proteins were probed using appropriate primary and fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies and rhodamine-phalloidin. The apical accumulation of α-adaptin elicited by CD treatment (5 μM, 60 min) is also shown for comparison. Apical/lumenal regions are identified by *. Arrows depict the accumulation of α-adaptin, dynamin, or N-WASP, respectively, at the APM associated with CD treatment or introduction of syndapin SH3 domains. Arrowheads depict the accumulation of dynamin or N-WASP in parallel with additional F-actin structures elicited by electroporation with syndapin SH3 domains. Bar, ∼10 μm.

Confocal microscopy also suggested that introduction of syndapin I or II SH3 domains induced F-actin structures. This F-actin accumulated at sites both proximal and distal from the APM (Figure 7, B and C, arrowheads). Interestingly, although a large component of the dynamin labeling in acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains was recruited to the APM (Figure 7B, arrows), additional stores of dynamin also seemed to associate with the F-actin structures formed throughout the cytoplasm (Figure 7B, arrowheads). Surprisingly, although N-WASP was not noticeably enriched at the APM of lacrimal acini exposed to CD or CCH (Figure 6), we did observe traces of N-WASP at the APM (Figure 7C, arrows) and large increases in N-WASP association with the F-actin structures (Figure 7C, arrowheads) in lacrimal acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains. These effects were specific for the active syndapin SH3 domains, because neither the mutated SH3 nor GST seemed to increase F-actin structures (Figure 7). As well, the increase in F-actin was equivalent either in the absence (Figure 7) or presence (our unpublished data) of CCH stimulation. Synaptojanin was not enriched at the APM after electroporation with syndapin SH3 domains (our unpublished data); moreover, its recruitment to this region after CCH stimulation occurred normally in acini containing syndapin SH3 domains (our unpublished data). Subsequent analyses of the mechanisms of the syndapin SH3 domain effects in Figures 8, 9, 10 feature either syndapin I or syndapin II SH3 domains, because their effects in acini were indistinguishable.

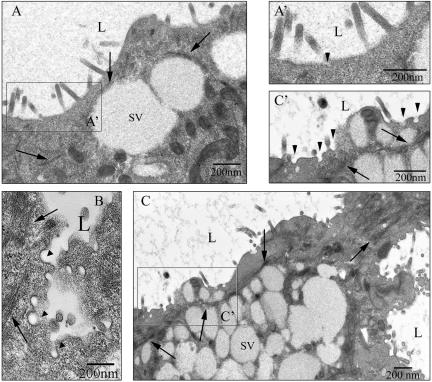

Figure 8.

EM images of coated pits and vesicles at the APM of resting acini electroporated with GST fusion proteins. (A) APM-enriched in microvilli facing a lumen (L) in an acinus electroporated without fusion proteins. Occasional clathrin-coated pits or vesicles (arrows) are seen at the APM. (B) Introduction of the syndapin II SH3 domain increased the number of clathrin-coated pits or vesicles (arrows) detected at the APM as well as actin bundles (arrowheads) (C) Acini electroporated in the presence of syndapin II SH3 domains also exhibited regions of the APM that seemed to be densely coated, possibly indicating nascent coated pits in early stages of formation (C′, arrows).

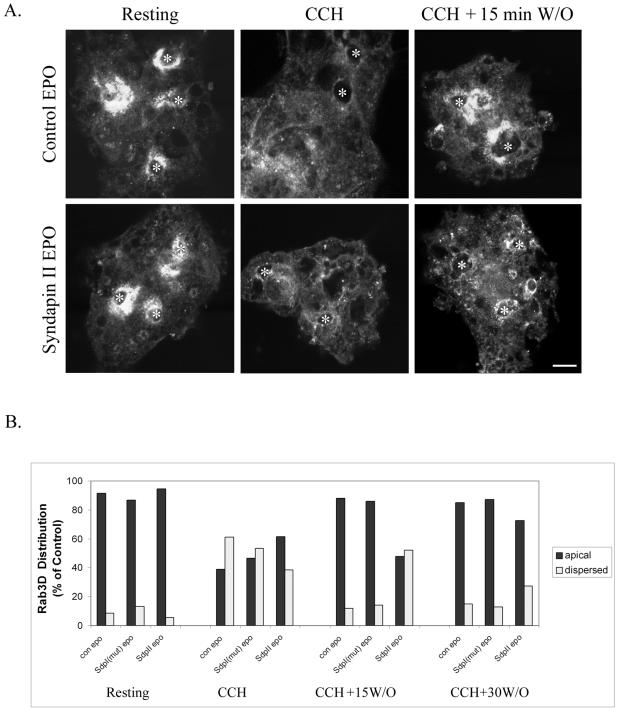

Figure 10.

Introduction of the syndapin II SH3 domain delays apical recovery of rab3D after CCH stimulation. Lacrimal acini electroporated in the absence (control EPO) or presence of syndapin I (mut) or syndapin II SH3 fusion proteins as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS were treated without or with CCH followed by washout of CCH for either 15 or 30 min. (A) Rab3D immunofluorescence in representative images of control electroporated (control EPO) and syndapin II electroporated (syndapin II EPO) lacrimal acini under the following conditions: resting, CCH (15 min, 100 μM) and CCH stimulation (15 min, 100 μM) followed by washout and recovery for 15 min (CCH + 15 min W/O). *, lumenal regions and bar, 10 μm. (B) Quantitation of rab3D labeling from resting acini, acini stimulated with CCH (15 min, 100 μM), and acini stimulated with CCH followed by washout and recovery for either 15 or 30 min. Labeling was designated within one of two categories: apical or dispersed. Rab3D content was scored in 60–98 acini/treatment from two separate preparations.

Syndapin I and II SH3 Domains Promote Accumulation of Coated Pits and Vesicles at the APM

We used EM to further examine the nature of the intermediates formed in acini electroporated with syndapin I and II SH3 domains. As shown in Figure 8A, electroporation alone did not perturb acinar morphology as mature SVs, grouped around a lumenal region enriched in microvilli, could readily be detected. Occasional coated pits and vesicles (arrows) could also be detected, comparable with the levels detected in resting acini (Figure 3). Introduction of either the mutated SH3 domain of syndapin I or GST alone (our unpublished data) revealed comparable lumenal morphology and comparable numbers of coated pits and vesicles relative to control (Figure 3) and control electroporated samples (Figure 8A). Introduction of the SH3 domains of either syndapin I (our unpublished data) or II (Figure 8, B and C), however, revealed increased numbers of coated pits and vesicles (arrows) at the APM as well as detectable accumulations of actin filaments (arrowheads).

These observations were verified by quantitation of the density of coated pits and vesicles at the APM (pits + vesicles/μm of APM) in randomly acquired images of lumena under each condition (Table 3), which revealed increases in acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains. Because it was difficult to determine whether an apparent coated vesicle might actually be a grazing section of a deeply invaginated pit, we grouped pits and apparent vesicles together in this analysis. However, >75% of the total structures detected in the acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains were clearly coated pits; because these values were substantially increased relative those from control acini or acini electroporated with the mutated SH3 domain or GST alone, these findings suggest an increase in coated pits with introduction of SH3 domains. Additional regions representing an apparent accumulation of electron dense material in what seemed to be the initial stages of coated pit formation were also seen at the APM of acini electroporated with the SH3 domains of syndapin II (Figure 8C′, arrows), and syndapin I (our unpublished data).

Table 3.

Coated pit and vesicle density at the apical plasma membrane of lacrimal acini electroporated with GST fusion proteins

| Con (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | GST (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | SdpI(mut) (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | SdpI (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | SdpII (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | SdpI + VCA (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | SdpII + VCA (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) | VCA (pits plus vesicles/μm membrane) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.33 ± 0.12 | 0.65 ± 0.16 | 0.68 ± 0.14 | 0.26 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.29 ± 0.05 |

Con, resting acini.

Quantitation of coated pits and vesicles of randomly acquired EM images of lumena within electroporated acini in the presence and absence of fusion proteins. Clathrin-coated pits and/or coated vesicles in each image were identified based on the characteristic electron dense appearance of the clathrin coat. Clathrin-coated pits were defined as structures apparently contiguous with the apical plasma membrane. Clathrin-coated vesicles were defined as electron-dense structures within ∼150 μm of the apical membrane. The total number of coated pits and/or vesicles in each image was quantitated, summed, and normalized to the length of apical membrane analyzed. Apical membrane length was determined using MetaMorph Image quantitation software. Values represent coated pits plus vesicles per micrometer membrane from 10 to 14 randomly acquired lumenal regions from a representative experiment.

Accumulation of F-Actin Caused by Syndapin SH3 Domains Requires Arp2/3 and Contributes to the Accumulation of Clathrin and Associated Proteins at the APM

Figure 7 suggested that introduction of syndapin I or II SH3 domains increased F-actin. To verify this observation, we used MetaMorph image quantitation software to quantify the intensity of F-actin labeling in serial sections from multiple acini. Two representative serial images (acquired at ∼1 μm intervals) under each condition are shown in Figure 9A, whereas the composite results from multiple acini from separate preparations are depicted graphically in Figure 9B. Introduction of the SH3 domains of syndapins I and II but not the mutated SH3 domain or GST alone caused a significant (p ≤ 0.05) 46–51% increase in total F-actin content.

GST pull-down assays (Figure 5B) revealed syndapin SH3 domain binding to N-WASP in lacrimal acini. N-WASP has been shown, in vitro and in vivo, to drive actin polymerization via activation of the Arp2/3 complex. Moreover, N-WASP seemed to be associated with the increased F-actin bundles seen in acini electroporated with syndapin I and II SH3 domains (Figure 7C). We were consequently interested in determining whether the significant accumulation of F-actin seen in acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains (Figure 9B) occurred via an Arp2/3-dependent pathway. N-WASP binding to Arp2/3 occurs via N-WASP's acidic domain. The isolated C-terminal VCA-domain of N-WASP has been shown to prevent cortical activation of the Arp2/3 complex. GST-fusion protein containing the VCA domain was introduced into lacrimal acini by electroporation, in the absence or presence of the SH3 domains of syndapins I and II. VCA domain introduction alone had no effects on F-actin content, but prevented the significant accumulation of F-actin associated with introduction of either syndapin I or II SH3 domains alone (Figure 9, A and B). Coelectroporation with the VCA domain also prevented the accumulation of N-WASP with actin filaments elicited in the presence of the syndapin I SH3 domain (Figure 9C, arrows) or the syndapin II SH3 domain (our unpublished data). Intriguingly, the reversal of F-actin accumulation elicited by coelectroporation with the VCA domain was paralleled by a reversal of the α-adaptin accumulation (Figure 9D) and coated pit accumulation (Table 3) at the APM.

Syndapin SH3 Domains Delay the Apical Recovery of rab3D-enriched Mature SVs after CCH Stimulation

We investigated whether the syndapin SH3 domain-induced accumulation of clathrin and accessory proteins and coated pits and vesicles at the APM revealed by confocal fluorescence microscopy (Figure 7) and EM (Figures 8 and 3), respectively, affected acinar secretion. As shown in Table 4, treatment of acini with CD or electroporation with syndapin SH3 domains did not significantly alter either basal or CCH-stimulated release of bulk protein or the secretory protein, β-hexosaminidase, after a single dose of CCH. However, differences in the repletion of mature rab3D-enriched SVs after CCH stimulation were detected under these conditions. Mature SVs enriched in rab3D are clustered around the APM, and CCH stimulation results in a rapid loss of rab3D immunoreactivity consistent with its release during SV exocytosis (Wang et al., 2003). Washout of CCH results in a rapid restoration of apical rab3D-enriched mature SVs, which is complete within 15 min. This characteristic pattern of dispersal and repletion is illustrated in Figure 10A in lacrimal acini electroporated without fusion protein. Figure 10A also reveals that although rab3D labeling is dispersed normally by CCH treatment of acini electroporated with syndapin II SH3 domains, recovery of apical labeling after CCH washout at 15 min is delayed relative to acini electroporated in the absence of protein. This response was scored across multiple acini as the percentage of rab3D immunoreactivity localized in an apical or dispersed labeling pattern under each condition. As shown in Figure 10B, addition of the syndapin II SH3 domain but not the syndapin I (mut) SH3 domain doubles the recovery time required for repletion of rab3D-enriched mature SVs in lacrimal acini, an effect presumably associated with impaired retrieval of apical membrane by the syndapin SH3 domains. A similar delay in repletion of rab3D-enriched SVs was seen in CD-treated acini stimulated with CCH (our unpublished data).

Table 4.

Resting and CCH-stimulated secretion of β-hexosaminidase and bulk protein in lacrimal acini

| β-Hexosaminidase (mg/ml protein)

|

Protein (mg/ml protein)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatments | Resting | Stimulated | Resting | Stimulated |

| Control | 100 | 197.45 ± 16.75 | 100 | 232.32 ± 22.63 |

| CD | 131.55 ± 13.02 | 174.95 ± 15.39 | 106.90 ± 6.62 | 225.92 ± 25.72 |

| EPO Control | 100 | 195.31 ± 17.75 | 100 | 181.67 ± 24.81 |

| EPO GST | 103.96 ± 22.35 | 179.20 ± 19.27 | 94.55 ± 7.71 | 172.01 ± 35.52 |

| EPO Sdp I (mut) | 89.76 ± 13.90 | 178.21 ± 4.81 | 85.90 ± 5.20 | 190.45 ± 32.02 |

| EPO SdpI | 92.76 ± 19.82 | 209.09 ± 35.68 | 78.89 ± 9.09 | 203.61 ± 37.47 |

| EPO Sdp II | 92.65 ± 21.51 | 202.79 ± 18.17 | 82.90 ± 8.79 | 194.70 ± 33.28 |

EPO, electroporation.

β-Hexosaminidase and bulk protein release were calculated in AU/μl and micrograms per microliter of culture medium, respectively, normalized to milligrams of total protein and then each of the individual values was normalized to basal release (100%) in untreated acini. Analyses CD treatment (5 μM, 60 min) and EPO with different fusion proteins. Values in italics indicate significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase over unstimulated controls and n = 4—8 experiments.

DISCUSSION

Lacrimal acini release a variety of tear proteins into ocular fluid, a process accelerated by secretagogues. Several studies (Hamm-Alvarez et al., 1997; da Costa et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2003) have investigated the trafficking events involved in tear protein exocytosis, but little is known about the compensatory retrieval of APM. Our findings suggest that CCH stimulation results in a rapid (5 min), transient recruitment of clathrin and accessory proteins to the APM, which is restored to resting conditions by 15 min, suggesting these proteins are rapidly internalized after accumulation immediately after the exocytic burst.

The actin cytoskeleton is implicated in clathrin-mediated endocytosis in many cells (reviewed in Apodaca, 2001), although results have in part been conflicting. Actin filaments are hypothesized to participate in various capacities in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, including membrane invagination, scaffolding for assembly of accessory/regulatory proteins, and/or force generation during dynamin-mediated vesicle detachment from the membrane (reviewed in Qualmann et al., 2000). Our investigations revealed that CD treatment elicited a major accumulation of clathrin, α-adaptin, and dynamin at the APM that was not reversible (Figures 1 and 2 and Table 1). This accumulation was associated with an increase in clathrin-coated pits and vesicles (Figure 3). Evidence that the accumulation of clathrin and accessory proteins (Figures 1 and 2) and coated pits (Figure 3) with the APM was associated with functional inhibition of apical endocytosis was provided by density gradient analysis of subcellular membranes in acini incubated with [14C]dextran. As shown in Figure 4D, CD blocked the CCH-induced accumulation of [14C]dextran into a high-density transport intermediate recovered in fraction P, resulting in the significant accumulation of [14C]dextran in fraction 1, a fraction enriched in APM (Figure 4B). No such effects were caused by CD on a marker of basolateral endocytosis, EGF (Figure 4C). The observed accumulations of endocytic machinery were associated with CD-induced bundling and accumulation of apical actin. Although CD elicited apical coated pit and vesicle accumulation in unstimulated acini, it signifi-cantly impaired apical endocytosis of [14C]dextran only in CCH-stimulated acini, suggesting the rate of apical endocytosis in resting cells accounts for too small a component of the total to be detectable with the methods we used.

To discern the identity and role of effector proteins that might link actin filaments to apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis, we investigated the role of syndapins in apical endocytosis in lacrimal acini. Evidence supporting a role for syndapins in this process in lacrimal acini includes 1) the association of acinar dynamin, N-WASP, and synaptojanin with syndapin I and II SH3 domains (Figure 5B); 2) the accumulation of syndapin II and its interaction partners at the APM of acini upon CCH-induced stimulation of endocytosis (Figure 6); and 3) the accumulation of clathrin, F-actin and the syndapin interaction partners (Figure 7) and the increase in coated pit and vesicle content (Figure 8 and Table 3) at the APM of acini electroporated with syndapin I and II SH3 domains, respectively. Previous studies using permeabilized cells to investigate clathrin-coated vesicle formation at a biochemical level have implicated syndapin I in late events involving membrane fission (Simpson et al., 1999). Our data showing that most intermediates detected at the APM of acini electroporated with SH3 domains were at the coated pit stage (Figure 8) are consistent with their observations.

The introduction of syndapin I and II SH3 domains led to an increase in F-actin structures at the APM and within the cytoplasm. As strong evidence that this syndapin-induced actin polymerization was mediated by Arp2/3, we observed that this effect was suppressed by coelectroporation with the N-WASP VCA domain (Figure 9), which is reminiscent of the actin polymerization triggered at the surface of fibroblast cells overexpressing syndapin constructs (Qualmann and Kelly, 2000). N-WASP, once activated by interacting molecules such as Cdc42 but also PIP2 and SH3 domain proteins (reviewed in Higgs and Pollard, 2001; Takenawa and Miki, 2001), regulates actin dynamics through binding and activation of the Arp2/3 complex. Association of WASP proteins with SH3 domain proteins is thought to occur via its extensive PRD. Recently, the syndapin binding site on the N-WASP molecule was identified to be the N-WASP PRD (Kessels and Qualmann, 2002).

Qualmann and Kelly (2000) demonstrated that overexpression of epitope-tagged full-length syndapins, but not N-terminal or SH3 domains alone, induced filopodial formation. In lacrimal acini, however, syndapin SH3 domain fusion proteins were sufficient to modulate actin dynamics. Confocal microscopy and EM analysis (Figures 7, 8, 9) clearly revealed significant increases in F-actin content, largely associated with F-actin structures enriched at the APM in acini electroporated with syndapin I and II SH3 domains but not with the mutated SH3 domain or GST alone. Lacrimal acini differ markedly from fibroblastic cells in their F-actin organization; their APM regions contain actin-enriched microvilli and an abundant cortical apical actin array. Apical actin is particularly dynamic in acinar epithelial cells, with stimulation associated with substantial depolymerization and reassembly of F-actin concomitant with secretagogue-induced fusion of SVs in pancreas and parotid acini (Muallem et al., 1995; Valentijn et al., 1999; Torgerson and McNiven, 2000; Rosado et al., 2002). Although we do not see comparable depolymerization of F-actin in CCH-stimulated lacrimal acini by using biochemical methods (da Costa et al., 1998), we have noted that the apical actin network becomes less prominent during CCH stimulation, indicative of transient actin disassembly and/or redistribution. Syndapins may differently influence actin dynamics in lacrimal acini and other secretory epithelial cells relative to nonpolarized cell types, due to the altered signaling environment, abundance of different effector proteins, and the additional contributions of the actin cytoskeleton to other membrane-trafficking events within proximity.

The F-actin structures observed at the APM of lacrimal acini electroporated with syndapin SH3 domains seemed to be enriched in both syndapin binding partners, N-WASP, and dynamin (Figure 7). Although the presence of N-WASP most likely represents the fact that the F-actin structures were built by activation of N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex, because they were suppressible by the N-WASP VCA domain, the presence of dynamin suggests that this GTPase also exhibits physical and functional connections to the apical actin cytoskeleton in lacrimal acini. Dynamin family members have recently been localized to special F-actin structures within different cells (reviewed in Qualmann and Kessels, 2002). Importantly, dynamin recruitment to actin tails was dependent on the PRD and overexpression of dynamin ΔPRD mutants disrupted actin tail formation (Lee and De Camilli, 2002; Orth et al., 2002), suggesting a linkage of dynamin to the actin cytoskeleton via PRD binding partners. Syndapins are ideal candidates for such a functional linkage of the GTPase dynamin controlling the fission reaction and control of actin polymerization via N-WASP and the Arp2/3 complex.

Our data suggest that regions of the APM destined for internalization attract adapter proteins, acquire a clathrin coat, invaginate, and recruit additional endocytic machinery, including dynamin, syndapin II, and synaptojanin. Syndapins are thought to associate through their SH3 domains with the PRD domain of dynamin and to transiently coaccumulate at clathrin-coated pits. A switch of syndapin interactions or the formation of larger complexes may allow syndapins to associate with the PRD of N-WASP, subsequently eliciting a burst of Arp2/3 complex-mediated actin polymerization at sites of endocytosis. Under normal conditions, N-WASP would initiate a locally restricted and transient actin polymerization in the vicinity of the coated pit, explaining the lack of apical enrichment of N-WASP under physiological conditions associated with accumulation of clathrin and accessory proteins. Syndapin II recruitment to the acinar APM must be independent of the N-terminal SH3 domain because the effects of introduction of SH3 domains from either syndapin I or II were indistinguishable in terms of inhibiting apical clathrin-mediated endocytosis. It is likely that syndapin II-specific binding partners exist that interact with regions besides the SH3 domain and that these interactions mediate its targeting.

We propose that the transient increase in actin polymerization promoted by N-WASP facilitates maturation of the coated pit. In the absence of an appropriate association/stabilization by F-actin, the constituents of the coated pit may diffuse away from the site. A stabilizing effect of F-actin on coated pit stabilization/maturation is supported by the increase in clathrin and accessory proteins and the increase in coated pits detected at the APM of lacrimal acini under conditions where apical actin is selectively increased (CD treatment and/or syndapin SH3 domains), but endocytosis is not stimulated (absence of CCH stimulation).

The trapping of coated pit intermediates under conditions associated with increased F-actin is consistent with the requirement for subsequent remodeling of actin at the site of the mature coated pit into a form that can mediate subsequent detachment and/or propulsion of the coated vesicle. A burst of local actin polymerization has previously been suggested to support vesicle fission, detachment, and/or movement (Qualmann et al., 2000). Merrifield et al. (2002) recently observed actin polymerization where and when clathrin-coated vesicles departed from the plasma membrane by evanescent field microscopy, and Taunton et al. (2000) reported N-WASP localization at the interface of vesicle membranes and actin tails formed in cell extracts. Our data strongly suggest that failure to remodel or recycle the excess F-actin elicited by either CD treatment or syndapin SH3 domain introduction prevents the detachment of coated pits while delaying the repletion of mature SVs. Excess syndapin SH3 domains seem to disrupt the coordination of actin dynamics and endocytosis. Because these effects were suppressible by VCA it seems that the observed endocytosis impairment was caused by actin polymerization elicited through Arp2/3. This finding is in line with the recent discovery that the Arp2/3 complex activator, N-WASP, plays a role in receptor-mediated endocytosis and that it performs this function by interacting with the syndapin SH3 domain. In conclusion, our findings suggest that the ability of actin to form a series of diverse structures or scaffolds, some regulated by syndapin interactions, is essential for the appropriate stabilization, maturation, and budding of clathrin-coated pits at the APM of these specialized secretory epithelial cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michelle MacVeigh for expert assistance with EM sample preparation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant EY-11386 to S.H.A., EY-10550 to J.S., and EU-05081 to A.K.M., and by National Institutes of Health grant 1 P30 DK48522 (Confocal Microscopy Subcore, USC Center for Liver Diseases, Los Angeles, CA). Additional salary support to S.H.A. was from National Institutes of Health grants NS-38246, DK-56040, and GM-59297. S.D. was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health minority fellowship (EY-07037) and by a postdoctoral grant PD/6281/2001 (from the Portuguese Ministry of Science and Technology, Lisbon, Portugal). This study was also supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschat to B.Q. and M.M.K. (QU 116/2-3 and KE 685/2-1, respectively) as well as by grants from the Kultusministerium of the Bundesland Sachsen-Anhalt (3199A/0020G and 3451A/0502M) to B.Q.

Abbreviations used: APM, apical plasma membrane; CCH, carbachol; CD, cytochalasin D; DPBS, Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline; EM, electron microscopy; GST, glutathione S-transferase; N-WASP, neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein; PRD, proline-rich domain; SH3, src homology 3 domain; SV, secretory vesicle.

References

- Apodaca, G. (2001). Endocytic traffic in polarized epithelial cells: role of the actin and microtubule cytoskeleton. Traffic 2, 149-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, P.S. (1978). Energy-dependence of phlorizin binding to isolated renal microvillus membranes. Evidence concerning the mechanism of coupling between the electrochemical Na+ gradient and sugar transport. J. Membr. Biol. 42, 81-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky, F.M., Chen, C-Y., Knuehl, C., Towler, M.C., and Wakeham, D.E. (2001). Biological basket-weaving: formation and function of clathrin-coated vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17, 517-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J.A. (1987). Effects of cytochalasin and phalloidin on actin. J. Cell Biol. 105, 1473-1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona, O., et al. (1999). Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell 99, 179-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa, S.R., Yarber, F.A., Zhang, L., Sonee, M., and Hamm-Alvarez, S.F. (1998). Microtubules facilitate the stimulated secretion of β-hexosaminidase in lacrimal acinar cells. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1267-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danino, D., and Hinshaw, J.E. (2001). Dynamin family of mechanoenzymes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 454-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartt, D.A. (1994). Signal transduction and activation of the lacrimal gland. In: Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology, 2nd ed., ed. D.M. Albert and F.A. Jacobiec, Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company, 458-465.

- Fullard, R. (1994). Tear proteins arising from lacrimal tissue. In: Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology, 2nd ed., ed. D.M. Albert and F.A. Jacobiec, Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company, 473-479.

- Gierow, J.P., Lambert, R.W., and Mircheff, A.K. (1995). Fluid phase endocytosis by isolated rabbit lacrimal gland acinar cells. Exp. Eye Res. 60, 511-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierow, J.P., et al. (1996). Na, K-ATPase in lacrimal gland acinar cell endosomal system. Correcting a case of mistaken identity. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C1685-C1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm-Alvarez, S.F., da Costa, S., Yang, T., Wei, X-H., Gierow, P., and Mircheff, A.K. (1997). Cholinergic stimulation of lacrimal acinar cells promotes redistribution of membrane-associated kinesin and the secretory protein, β-hexosaminidase, and increases kinesin motor activity. Exp. Eye Res. 64, 141-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs, H.N., and Pollard, T.D. (2001). Regulation of actin filament network formation through ARP2/3 complex: activation by a diverse array of proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 649-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw, J.E., and Schmid, S.L. (1995). Dynamin self-assembles into rings suggesting a mechanism for coated vesicle budding. Nature 374, 190-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, M.M., Engqvist-Goldstein, A.E., and Drubin, D.G. (2000). Association of mouse actin-binding protein 1 (mAbp1/SH3P7), an Src kinase target, with dynamic regions of the cortical actin cytoskeleton in response to Rac1 activation. Mol. Biol. Cell 11, 393-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, M.M., and Qualmann, B. (2002). Syndapins integrate N-WASP in receptor-mediated endocytosis. EMBO J. 21, 6083-6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzetti, L., Di Fiore, P.P., and Scite, G. (2001). Pathways linking endocytosis and actin cytoskeleton in mammalian cells. Exp. Cell Res. 271, 45-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E., and De Camilli, P. (2002). Dynamin at actin tails. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 161-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machesky, L.M., and Insall, R.H. (1999). Signaling to actin dynamics. J. Cell Biol. 146, 267-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, T.F. (2001). PI(4, 5)P(2) regulation of surface membrane traffic. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 493-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNiven, M.A., Kim, L., Krueger, E.W., Orth, J.D., Cao, H., and Wong, T.W. (2000). Regulated interactions between dynamin and the actin-binding protein cortactin modulate cell shape. J. Cell Biol. 151, 187-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, P.S., Garcia, E.P., Slepnev, V.I., David, C., Zhang, X., Grabs, D., Sossin, W.S., Bauerfeind, R., Nemoto, Y., and De Camilli, P. (1996). A presynaptic inositol-5-phosphatase. Nature 379, 353-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrifield, C.J., Feldman, M.E., Wan, L., and Almers, W. (2002). Imaging actin and dynamin recruitment during invagination of single clathrin-coated pits. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 691-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mircheff, A.K., and Lu, C.C. (1984). A map of membrane populations isolated from rat exorbital gland. Am. J. Physiol. 247, G651-G661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muallem, S., Kwiatkowska, K., Xu, X., and Yin, H.L. (1995). Actin filament disassembly is a sufficient final trigger for exocytosis in nonexcitable cells. J. Cell Biol. 128, 589-598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth, J.D., Krueger, E.W., Cao, H., and McNiven, M.A. (2002). The large GTPase dynamin regulates actin comet formation and movement in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 167-172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L., Yang, T., Chen, H., Xie, J., Zeng, H., Warren, D.W., MacVeigh, M., Meneray, M.A., Hamm-Alvarez, S.F., and Mircheff, A.K. (2002). Heterotrimeric GTP-binding proteins in the lacrimal acinar cell endomembrane system. Exp. Eye Res. 74, 7-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann, B., Roos, J., DiGregorio, P.J., and Kelly, R.B. (1999). Syndapin I, a synaptic dynamin-binding protein that associates with the Neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 501-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann, B., and Kelly, R.B. (2000). Syndapin isoforms participate in receptor-mediated endocytosis and actin organization. J. Cell Biol. 148, 1047-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann, B., Kessels, M.M., and Kelly, R.B. (2000). Molecular links between endocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton. J. Cell Biol. 150, F111-F116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualmann, B., and Kessels, M.M. (2002). Endocytosis and the Cytoskeleton. Int. Rev. Cytol. 220, 93-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado, J.A., Gonzalez, A., Salido, G.M., and Pariente, J.A. (2002). Effects of reactive oxygen species on actin filament polymerisation and amylase secretion in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Cell. Signal. 14, 547-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakisaka, T., Itoh, T., Miura, K., and Takenawa, T. (1997). Phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate phosphatase regulates the rearrangement of actin filaments. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 3841-3849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, D.A. (2002). Coupling actin dynamics and membrane dynamics during endocytosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 76-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, J.E., Stevenson, D., Chang, D., Chang, N., Pidgeon, M., Nakamura, T., Okamoto, C.T., Mircheff, A.K., and Trousdale, M.D. (2002). Growth of purified lacrimal acinar cells in Matrigel® raft cultures. Exp. Eye Res. 74, 349-360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sechi, A.S., and Wehland, J. (2000). The actin cytoskeleton and plasma membrane connection: PtdIns(4,5)P(2) influences cytoskeletal protein activity at the plasma membrane. J. Cell Sci. 113, 3685-3695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, F., Hussain, N.K., Qualmann, B., Kelly, R.B., Kay, B.K., McPherson, P.S., and Schmid, S.L. (1999). SH3-domain-containing proteins function at distinct steps in clathrin-coated vesicle formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepnev, V.I., and De Camilli, P. (2000). Accessory factors in clathrin-dependent synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 161-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takenawa, T., and Miki, H. (2001). WASP and WAVE family proteins: key molecules for rapid rearrangement of cortical actin filaments and cell movement. J. Cell Sci. 114, 1801-1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taunton, J., Rowning, B.A., Coughlin, M.L., Wu, M., Moon, R.T., Mitchison, T.J., and Larabell, C.A. (2000). Actin-dependent propulsion of endosomes and lysosomes by recruitment of N-WASP. J. Cell Biol. 148, 519-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toker, A. (1998). The synthesis and cellular roles of phosphatidylinositol 4,5 bisphosphate. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 10, 254-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]