Abstract

BACKGROUND

To identify the factors that contribute to poorer colon carcinoma survival rates for African Americans compared with Caucasians, the authors evaluated survival differences based on the histologic grade (differentiation) of the tumor.

METHODS

All 169 African Americans and 229 randomly selected non-Hispanic Caucasians who underwent surgery during 1981–1993 for first primary sporadic colon carcinoma at the University of Alabama at Birmingham or its affiliated Veterans Affairs hospital were included in the current study. None of these patients received presurgery or postsurgery therapies. Recently, the authors reported an increased risk of colon carcinoma death for African Americans in this patient population, after adjustment for stage and other clinicodemographic features. The authors generated Kaplan–Meier survival probabilities according to race and tumor differentiation and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

RESULTS

There were no differences in the distribution of pathologic tumor stage between racial groups after stratifying by histologic tumor grade. Among patients with high-grade tumors, 54% of African Americans and 21% of Caucasians died within the first year after surgery (P = 0.007). African Americans with high-grade tumors were 3 times (HR = 3.05; 95% CI, 1.32–7.05) more likely to die of colon carcinoma within 5 years postsurgery, compared with Caucasians with high-grade tumors. There were no survival differences by race among patients with low-grade tumors.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings suggested that poorer survival among African-American patients with adenocarcinomas of the colon may not be attributable to an advanced pathologic stage of disease at diagnosis, but instead may be due to aggressive biologic features like high tumor grades.

Keywords: African Americans, Caucasians, colon carcinoma, high-grade tumor differentiation

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the third most common malignancy and second most common cause of cancer mortality among men and women in the United States. In 2004, it is estimated that there will have been 106,370 new cases of colon carcinoma and 40,570 new cases of rectal carcinoma with 56,730 deaths due to colon and rectal carcinoma combined.1 In the United States, there are racial differences (African American compared with Caucasian) in CRC incidence, mortality, and survival, and the highest CRC incidence and mortality rates and the lowest survival rates occur among African Americans.1–4 Based on updated Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program data, over the past 25 years, mortality rates among Caucasians have slowly, but steadily declined. Specifically, there has been an incremental decrease in age-adjusted mortality rates for each year, beginning in 1984 (27.3 per 100,000) and ending in 2001 (19.5 per 100,000).5 In contrast, the trend in mortality rates among African Americans has been inconsistent, as rates generally increased beginning in 1975 (26.8 per 100,000), peaked in 1990 (30.8 per 100,000), and sporadically decreased through 2001 (27.6 per 100,000).5 The divergence in mortality rates between African Americans and Caucasians is a reflection of racial disparities in CRC survival.

Overall and stage-specific CRC survival rates at 5 years postsurgery are greater for Caucasians compared with African Americans.1–4 Jemal et al.2 reported trends in 5-year relative survival rates among African-American and Caucasian patients with colon carcinoma across 3 diagnostic periods (1974–1976, 1983–1985, 1992–1999) based on SEER data. Among Caucasians, relative survival rates increased from 51% to 63% (a 12% change). The survival rate increase was less pronounced among African Americans as relative survival rates increased from 46% to 53% (a 7% change). There have been several hypothesized reasons for the CRC racial disparities in survival.6–8 Previous studies have suggested that socioeconomic differences and variability in clinicopathologic characteristics are the two primary factors that contribute to survival differences by race.3,6–8 Differential opportunities for treatment, varying degrees of quality of care, and aspects of comorbid conditions are among the socioeconomic dissimilarities.3,6–8 Clinicopathologic variability includes an advanced stage of disease at diagnosis and tumor-specific biologic disparities between African Americans and Caucasians.8–16 However, a recent study from our group reported stage-independent racial differences in survival, and suggested that African-American patients with colon adenocarcinomas who underwent surgery alone as a therapeutic intervention had decreased colon carcinoma-specific survival at 5 and 10 years postsurgery.17 Also, this same study suggested that the increased risk of colon carcinoma mortality among African Americans was not due to advanced-stage disease at diagnosis or treatment dissimilarities, but may have been due to differences in other biologic features that may contribute to aggressive tumor behavior, specifically in African Americans.

The pathologic stage of tumors after surgical resection in patients with CRC is the most powerful indicator of prognosis.18 In addition, previous studies have observed that the histologic grade (differentiation) of the tumor was a stage-independent prognostic factor in patients with CRC.12,13,17,19,20 Several previous studies have relied on state tumor registry or other administrative data sources for tumor characteristics to evaluate colon carcinoma survival disparities by race. These data sources often lack detailed and specific clinical and tumor characteristics and are prone to variable misclassification due to coding errors.14,15,21–23 Thus, previous disparities based on race may be confounded by factors related to tumor biology, such as tumor differentiation.

African Americans are diagnosed with colon carcinoma at a younger age than Caucasians,24 and a high frequency of poorly differentiated CRC among young patients has been shown to contribute to poor patient prognosis.25–27 To evaluate the prognostic importance of tumor differentiation, we conducted a retrospective follow-up study of patients who received surgery as their only therapeutic intervention, to evaluate racial (African American vs. Caucasian) differences in colon carcinoma survival after stratifying by histologic tumor grade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The tumor registries of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and its affiliated Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital provided the medical records of 819 (595 Caucasians, 224 African Americans) patients who were surgically treated for CRC between 1981 and 1993. From this group, we selected all 224 African-American and 350 randomly selected non-Hispanic Caucasian patients with colon adenocarcinomas. We extracted patient demographic and clinicopathologic data from the medical records and surgical pathology reports. This information was further validated by trained reviewers (CC, UM). We excluded patients with unspecified tumor location, with multiple primary tumors within the colorectum, with multiple malignancies, or with inheritable colon carcinoma syndromes. Therefore, only patients with first primary sporadic colon tumors were included in our study sample. Because adenocarcinomas are the predominant (> 95%) histologic type of colon carcinoma in the U.S. general population,28 we excluded patients with nonadenocarcinomas. Surgical resection is the most effective curative therapy for CRC, and we included all patients who were surgically treated and excluded those who received presurgical or postsurgical adjuvant therapy to minimize differential treatment bias. Patients who died within 1 week of their surgery were excluded form the analyses. Therefore, our current study sample consisted of 169 African-American and 229 Caucasian patients diagnosed with first primary Stage I–IV colon adenocarcinomas.

The UAB and VA tumor registries were used to gather follow-up information related to patient vital status. We used a dynamic study follow-up period beginning at the date of surgery and extending to the date of death or the date of last documented living contact. The tumor registries ascertained outcome (mortality) information directly from patients (or living relatives) and from the physicians of the patients through telephone and mail contacts. This information was further validated by state death lists. The tumor registries update follow-up information every 6 months and follow-up of our cohort ended in March 2004.

We ascertained demographic and clinicopathologic information including pathologic stage and the anatomic location of tumors from patient medical records and surgical pathology reports. Pathologic tumor staging was performed according to the criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer using Stages I, II, III, and IV.29 The International Classification of Diseases for Oncology codes were used to specify the anatomic location of the tumor.30 Tumor anatomic subsites within the colon were grouped as proximal colon (cecum, ascending and first two-thirds of the transverse colon) or distal colon (last one-third of the transverse colon, splenic flexure, descending colon, and the sigmoid colon).31,32

Several tumor grading systems have been suggested during the past few decades. However, no system has been widely accepted. Compton et al.33,34 recommend a two-tiered grading system consisting of high-grade (poorly and undifferentiated) and low-grade (well and moderately differentiated) tumors. This approach to the grading of tumors of the colon may reduce interobserver variation and retain or improve prognostic significance.34 In our study, three pathologists (NJ, JS, WEG) independently evaluated the histologic tumor grade for all patients by reviewing the hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)–stained slides. After pathologic assessment, tumors were graded as well, moderate, poor, or undifferentiated. Subsequently, we collapsed well and moderately differentiated tumors into a low-grade category and poor and undifferentiated tumors into a high-grade category. This reduces interobserver variability, particularly between well and moderately differentiated tumors.18,33–35

The primary outcome (event) of interest in our study was death due to colon carcinoma. Time at risk was calculated in months from the date of surgery to either the date of death or the date of last living contact within the study follow-up period. Patients were right censored at the time of death of a cause other than colon carcinoma, at the time of lost to follow-up, or at the end of the specified analysis period if alive.

Baseline characteristic differences between African Americans and Caucasians were evaluated using the chi-square test.36 Race and differentiation-specific Kaplan–Meier survival curves were estimated for a 10-year follow-up period and survival differences were evaluated using the log-rank test.37 Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of death due to colon carcinoma for African Americans compared with Caucasians.38 We generated models for the main effects as well as a model that included an interaction term for race and tumor differentiation. In addition, we generated separate Cox regression models that were stratified by tumor grade. In the stratified models, we categorized stage as local, regional, and distant to ensure model stability. All Cox regression analyses were adjusted for race, age, gender, treatment hospital, tumor anatomic subsite, pathologic tumor stage, tumor grade, and a race × grade interaction term, where applicable. We performed all of our analyses using SAS statistical software version 9.0 (SAS, Cary, NC).39,40 We validated the proportional hazards assumption by using influence statistics and graphical interpretations of residual plots.

RESULTS

The distribution of demographic and tumor characteristics is presented in Table 1 by race separately for low and high-grade tumors. The incidence of tumors in different grade categories was similarly distributed between the racial groups (P = 0.66). As shown in Table 1, there was a small gender difference by race within tumor grade. However, no differences were observed in age, hospital, tumor stage, or colon anatomic subsite. Over the entire follow-up period, there was a statistically significant difference (P = 0.02) in vital status by race among patients with high-grade tumors as 81% of the African-American patients died of colon carcinoma, compared with 49% of the Caucasian patients. However, there were no statistically significant racial differences in vital status among patients with low-grade tumors. Table 2 displays the crude colon carcinoma mortality risks by race and tumor grade. Fifty-four percent of the African-American patients with high-grade tumors died of colon carcinoma within 1 year of surgery, whereas 21% of the Caucasian patients with high-grade tumors died (P = 0.007). This significant racial disparity in mortality continued throughout the 5 years of follow-up. After 5 years postsurgery, 81% of the African-American patients with high-grade tumors died of colon carcinoma, compared with 47% of the Caucasian patients (P = 0.007). There were no events (deaths due to colon carcinoma) for African Americans and 1 event for Caucasians after 5 years of postsurgical follow-up.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Tumor Characteristics of 398 Caucasian and AA Patients with Colon Adenocarcinomas Based on Race and Tumor Grade

| Low grade (n = 333) |

High grade (n = 65) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian (n = 190) | AA (n = 143) | Caucasian (n = 39) | AA (n = 26) | |||

| Variables grade (n = 65) | No. (%) | No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | No. (%) | P value |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 120 (63.2) | 74 (51.8) | 0.04 | 29 (74.4) | 14 (53.9) | 0.09 |

| Female | 70 (36.8) | 69 (48.2) | 10 (25.6) | 12 (46.2) | ||

| Age (yrs) | ||||||

| 0–49 | 19 (10.0) | 11 (7.7) | 0.43 | 9 (23.1) | 2 (7.7) | 0.09 |

| 50–64 | 70 (36.8) | 46 (32.2) | 6 (15.4) | 9 (34.6) | ||

| ≥65 | 101 (53.2) | 86 (60.1) | 24 (61.5) | 15 (57.7) | ||

| Hospital | ||||||

| University | 123 (64.7) | 103 (72.0) | 0.16 | 31 (79.5) | 16 (61.5) | 0.11 |

| Veteran’s | 67 (35.3) | 40 (28.0) | 8 (20.5) | 10 (38.5) | ||

| Stage | ||||||

| I | 38 (20.0) | 30 (21.0) | 0.97 | 3 (7.7) | 2 (7.7) | 0.56 |

| II | 74 (39.0) | 52 (36.4) | 9 (23.1) | 9 (34.6) | ||

| III | 52 (27.4) | 40 (28.0) | 17 (43.6) | 7 (26.9) | ||

| IV | 26 (13.7) | 21 (14.7) | 10 (25.6) | 8 (30.8) | ||

| Colon site | ||||||

| Proximal | 86 (45.3) | 77 (53.9) | 0.12 | 25 (64.1) | 19 (73.1) | 0.45 |

| Distal | 104 (54.7) | 66 (46.2) | 14 (35.9) | 7 (26.9) | ||

| Vital status (end of follow-up)a | ||||||

| Alive | 55 (29.0) | 29 (20.3) | 0.20 | 10 (25.6) | 1 (3.9) | 0.02 |

| Death due to colon carcinoma | 84 (44.2) | 70 (49.0) | 19 (48.7) | 21 (80.8) | ||

| Death due to other causes | 51 (26.8) | 44 (30.8) | 10 (25.6) | 4 (15.4) | ||

AA: African American.

Patients were accrued between 1981 and 1993 and were followed until March 2004.

TABLE 2.

Crude Colon Carcinoma Mortality Risks by Race and Tumor Grade for 1-Year, 3-Year, and 5-Year Follow-Up Periods

| 1-Year |

3-Year |

5-Year |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | No. (%)a | P value | No. (%)a | P value | No. (%)a | P value |

| Caucasians | 33 (14.9) | 0.01 | 61 (27.6) | 0.002 | 79 (35.8) | 0.01 |

| African Americans | 41 (25.2) | 70 (42.9) | 79 (48.8) | |||

| Patients with low-grade tumors | 52 (16.3) | < 0.001 | 96 (30.0) | < 0.001 | 119 (37.2) | < 0.001 |

| Patients with high-grade tumors | 22 (34.4) | 35 (54.7) | 39 (60.9) | |||

| Caucasians with low-grade tumors | 25 (13.7) | 0.15 | 46 (25.1) | 0.03 | 61 (33.3) | 0.10 |

| African Americans with low-grade tumors | 27 (19.7) | 50 (36.5) | 58 (42.3) | |||

| Caucasians with high-grade tumors | 8 (21.1) | 0.007 | 15 (39.5) | 0.003 | 18 (47.4) | 0.007 |

| African Americans with high-grade tumors | 14 (53.9) | 20 (76.9) | 21 (80.8) | |||

Number of deaths in each strata; (%) represents the proportion of colon carcinoma deaths.

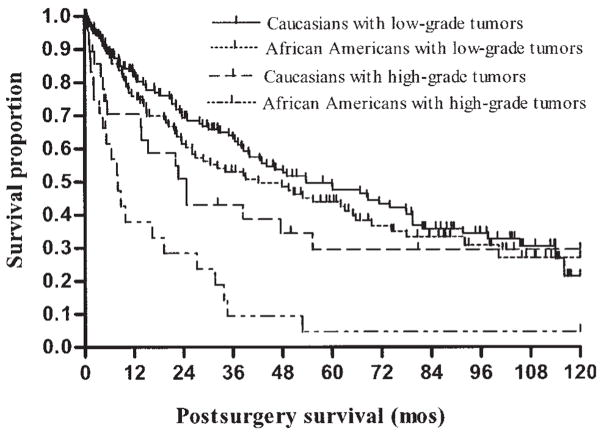

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for race by tumor grade classifications are displayed in Figure 1. African Americans with high-grade tumors had poorer survival within 10 years of postsurgical follow up compared with Caucasians with high-grade tumors (log-rank test: P = 0.004) and all other race × grade interaction groups. Survival by race was not significantly different among patients with low-grade tumors (log-rank test: P = 0.19). Within 5 years of post-surgical follow-up, 8% (n = 2) of the African-American and 16% (n = 6) of the Caucasian patients with high-grade tumors were censored. Among those with low-grade tumors, 12% (n = 17) of the African-American and 16% (n = 29) of the Caucasian patients were censored.

FIGURE 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis of African-American and Caucasian patients with colon adenocarcinomas, based on tumor grade. Survival differences among groups were observed (log-rank test: P = 0.004), and African Americans with high-grade tumors exhibited the shortest survival probability within 10 years of the postsurgical follow-up period.

Using a Cox regression model, we tested for a race × tumor grade interaction, which was statistically significant (P = 0.003). Therefore, we generated tumor grade-stratified Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the HR of colon carcinoma death for African Americans compared with Caucasians (Table 3). All Cox regression models were adjusted for race, gender, age, hospital, tumor stage, and tumor site within the colon. African Americans with high-grade tumors were 3 (HR = 3.05; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.32–7.05) times more likely to die of colon carcinoma within 5 years postsurgery compared with Caucasians with high-grade tumors. In contrast, there was not a statistically significant racial difference among patients with low-grade tumors. As expected, tumor stage was an independent prognostic indicator in both stratified models. Age, gender, tumor subsite, and treatment hospital were not independent predictors of mortality in either model (data not shown). When the 26 African-American patients with high-grade tumors were removed from the analysis, there was no difference in clinical outcome between African Americans and Caucasians (HR = 1.25; 95% CI, 0.81–1.81) (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate Cox Regression HR for Colon Carcinoma Mortality Stratified by Tumor Grade, Based on 5-Year Postsurgical Follow-Up

| Variable | Low gradea HR (95% CI) | High gradea HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| Caucasian (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| African American | 1.27 (0.87–1.83) | 3.05 (1.32–7.05) |

| Stage | ||

| Localized (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Regional | 2.72 (1.74–4.25) | 4.74 (1.74–12.74) |

| Distant | 11.61 (7.21–18.70) | 8.35 (3.21–21.76) |

HR: hazard ratio; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

Model adjusted for race, gender, age, hospital, tumor stage, and tumor site (race × tumor grade interaction term: P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

We conducted a retrospective follow-up study to elucidate differences in postsurgical mortality between African Americans and Caucasians with colon adenocarcinomas. Our findings revealed that African Americans with high-grade tumors had significantly greater mortality after surgical resection for colon carcinoma. The disparity in mortality by race was markedly increased for African Americans (vs. Caucasians) within the first year of surgery, and this difference continued throughout ≥ 5 years of follow-up. More than one-half of all African-American patients who were diagnosed with a high-grade adenocarcinoma of the colon died within 1 year of surgical resection, and > 80% of these patients died within 5 years of surgery. In contrast, 20% of Caucasian patients with high-grade tumors died within the first year of surgery, and less than one-half of these patients died within 5 years. Results from multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that African Americans with high-grade tumors were > 3 times as likely to die within 5 years of postsurgical follow-up, compared with Caucasians with high-grade tumors. There were no statistically significant racial differences present among patients with low-grade tumors. Furthermore, there was not a difference in mortality when comparing Caucasians with high-grade tumors with Caucasians with low-grade tumors (data not shown). Thus, the racial disparity in survival after surgical resection for colon adenocarcinomas may be largely attributable to aggressive tumor behavior in African-American patients with high-grade colon tumors.

In our previous report, we observed a > 50% statistically significant increased risk of colon carcinoma death after surgical resection for African Americans compared with Caucasians,17 after controlling for the effects of demographic and clinical characteristics, including tumor stage. Our previous study, like many others, reported tumor grade to be an independent prognostic predictor of colon carcinoma, even after adjusting for the effects of stage of disease at the time of diagnosis.12,13,17,19,20 However, previous studies have not specifically evaluated the prognostic value of tumor grade among patients with colon adenocarcinomas, while adjusting for demographic and other clinical characteristics. Because we observed a statistically significant interaction between race and tumor grade in our initial proportional hazards model, our subsequent models evaluated the risk of death due to colon adenocarcinoma among patients with both low and high-grade tumors while controlling for the effects of other demographic and clinical variables, such as tumor stage.

In the current study, there was a similar proportion of African-American (15%) and Caucasian (17%) patients with high-grade tumors at diagnosis, which is consistent with findings reported in previous studies.41 In contrast, Chen et al.42 evaluated the incidence of pathologic grades in tumors of the colon in African-American and Caucasian patients and found that after adjustment, African Americans had a tendency to have more favorable differentiated tumors (low-grade tumors). However, in these studies, the prognostic impact of tumor grade was not analyzed in a stratified proportional hazards model. Recently, several other studies have suggested that colorectal tumors with high-frequency microsatellite instability (MSI-H) are more likely to be poorly differentiated compared with microsatellite-stable or low-frequency MSI tumors.43–46 However, this trend was not observed in a recent study.47 It is unclear whether there is an association between race and pathologic grade within MSI-H tumors. Larger studies that will allow the stratification of race and tumor grade within tumors exhibiting MSI may elucidate an association.

The degree of differentiation refers to the extent to which neoplastic cells continue to resemble, both morphologically and functionally, the normal cells of the tissue within which a neoplasm develops.48 The hallmark of malignant transformation is the lack of differentiation, or anaplasia.49 Well differentiated tumors evolve from maturation of undifferentiated cells as they proliferate. These tumor cells are morphologically similar to cells found in the tissue of origin, and maintain many of the functions of normal cells. In contrast, poorly differentiated or undifferentiated tumors proliferate without maturation of the transformed cells.48,49 Several morphologic and functional cellular changes characterize a lack of differentiation including cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, or variation in size and shape, and large hyperchromatic (dark staining with hematoxylin) nuclei with nuclear membrane irregularity.

In many malignancies including CRC, several co-morbid health conditions such as diabetes mellitus (DM) are associated with increased risks of colon carcinoma50 and have been reported to impact patient survival.51 However, in our study population, there was a similar proportion of African Americans (15%) and Caucasians (13%) with prevalent DM. Furthermore, we did not find a significant difference by race in the overall prevalence (65% among African Americans vs. 72% among Caucasians) (data not shown) of patients with comorbid conditions. Also, we previously reported that death due to other causes was similar between African-American and Caucasian patients.17 Specifically, 25% of the Caucasian patients and 26% of the African-American patients died due to causes other than colon or rectal carcinoma, and this may be a reflection of similar comorbidity in our study populations. Furthermore, the proportions of patients that were censored at selected time points throughout the follow-up period were similar between racial groups and differential loss to follow-up by race was minimal.

It has been suggested that studies using administrative data are prone to misclassification errors and may lack detailed clinicopathologic information.14,21,22 Several previous studies relied solely on the acquisition of patient data from state cancer and tumor registries, Medicare files, and VA administrative records. Therefore, detailed clinocopathologic data were not available for analyses. This may severely confound observed findings by race because pathologic tumor stage is the strongest and most important indicator of CRC prognosis.18 Moreover, tumor differentiation and the anatomic locations of tumors are important prognostic indicators, and may contribute to the understanding of CRC survival differences by race. In our study, we used objective sources of data (medical records and surgical pathology reports) and did not rely on tumor registry or other forms of administrative data except for patient outcome. We were able to ascertain detailed demographic and tumor-specific information, which allowed us to control the effects of clinically relevant prognostic variables such as tumor stage, grade, and location. The classification of tumors based on differentiation was performed independently by three pathologists (NJ, JS, WEG), by reviewing the H&E-stained slides of all patients.

During our data abstraction process, we selected only patients who underwent surgical resection, and excluded those who received presurgical or postsurgical adjuvant therapy. This minimized systematic biases involved with differential opportunities for treatment based on race, as well as ethnic or cultural variations in the compliance of treatment. The effect of uniform treatment was previously illustrated by two large clinical studies that evaluated disease-free and overall survival differences between African Americans and Caucasians with Stage II/III colon carcinoma who received adjuvant chemotherapy.52, 53 These studies found that when patients were treated with uniform therapeutic regimens, survival differences were attenuated compared with population-based studies, suggesting that African Americans with Stage II/III colon carcinoma may benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Furthermore, survival studies that do not account for treatment differences between racial groups may be confounded.

Previous studies have suggested that differential understaging between racial groups or degrees of specialization among surgeons at different hospitals may be contributing factors to the survival discrepancy observed between African Americans and Caucasians.13,54 However, in our study, we had a homogenous group of physicians (clinical oncologists, surgeons, and pathologists) who diagnosed, treated, and staged all patients at both the UAB and VA hospitals. Therefore, biases in treatment, diagnosis, and staging between African Americans and Caucasians should be minimal. Thus, it is unlikely that these key characteristics contributed to the racial disparity in survival observed in our study.

Using a case accrual period from 1981 to 1993 and a study follow-up period from 1981 to 2004, we were able to utilize a retrospective follow-up design with a dynamic cohort of patients. This allowed us to evaluate 5 and 10-year survival patterns for our study population without losing data by early right censoring. In addition, our long follow-up period generated a high proportion of events (colon carcinoma deaths) that provided ample statistical power in our survival analysis. However, we were unable to perform stage-specific analyses stratifying by tumor grade and race because only 65 patients had high-grade tumors. Future studies with a larger proportion of patients with high-grade tumors are required to confirm this type of stratified analysis.

In summary, more than one-half of all African-American patients diagnosed with a high-grade tumor died within 1 year of surgical resection, and > 80% of these patients died within 5 years of surgery. Furthermore, African-American patients with high-grade tumors have a > 3 times increased risk of death from colon carcinoma within 5 years of surgery, compared with Caucasians. Our findings suggest that high-grade tumors in African Americans may be more aggressive compared with both low and high-grade tumors in Caucasians. African Americans with high-grade colon adenocarcinomas may benefit from a more aggressive therapeutic treatment and follow-up regimen.

Acknowledgments

Supported, in part, by grants R01-CA98932-01 and R03-CA097542-01 from the National Cancer Institute, which are funded by the National Institute of Health.

The authors thank Vanita Jain, M.D., and Venkat Ramakrishna Neelagiri, M.D., M.P.H., for their help in extracting the clinicopathologic and follow-up information for the patients included in the study.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2003. pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Tiwari RC, Murray T, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8–29. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101:3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer. 2000;88:2398–2424. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000515)88:10<2398::aid-cncr26>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ries LAG, Eisner MP, Kosary CL, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975-2001. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [accessed June 2004]. Available from URL: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciccone G, Prastaro C, Ivaldi C, et al. Access to hospital care, clinical stage and survival from colorectal cancer according to socio-economic status. Ann Oncol. 2000;11:1201–1204. doi: 10.1023/a:1008352119907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jepson C, Kessler LG, Portnoy B, et al. Black-white differences in cancer prevention knowledge and behavior. Am J Public Health. 1991;81:501–504. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandelblatt J, Andrews H, Kao R, et al. The late-stage diagnosis of colorectal cancer: demographic and socioeconomic factors. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1794–1797. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.12.1794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabeneck L, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, et al. Outcomes of colorectal cancer in the United States: no change in survival (1986–1997) Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:471–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, et al. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1985–1993. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.17.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merrill RM, Henson DE, Ries LA. Conditional survival estimates in 34,963 patients with invasive carcinoma of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1097–1106. doi: 10.1007/BF02239430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcella S, Miller JE. Racial differences in colorectal cancer mortality. The importance of stage and socioeconomic status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayberry RM, Coates RJ, Hill HA, et al. Determinants of black/white differences in colon cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1686–1693. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.22.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabeneck L, Souchek J, El-Serag HB. Survival of colorectal cancer patients hospitalized in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1186–1192. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wudel LJ, Jr, Chapman WC, Shyr Y, et al. Disparate outcomes in patients with colorectal cancer: effect of race on long-term survival. Arch Surg. 2002;137:550–554. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.5.550. discussion 554–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Govindarajan R, Shah RV, Erkman LG, et al. Racial differences in the outcome of patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:493–498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander D, Chatla C, Funkhouser E, et al. Postsurgical disparity in survival between African Americans and Caucasians with colonic adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2004;101:66–76. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett C. Cancer of the lower gastrointestinal tract, atlas of clinical oncology. Hamilton, Ontario: B.C. Decker Inc; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris GJ, Senagore AJ, Lavery IC, et al. Factors affecting survival after palliative resection of colorectal carcinoma. Colorectal Dis. 2002;4:31–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1318.2002.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samowitz WS, Curtin K, Ma KN, et al. Microsatellite instability in sporadic colon cancer is associated with an improved prognosis at the population level. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:917–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabeneck L, Davila JA, Thompson M, et al. Surgical volume and long-term survival following surgery for colorectal cancer in the Veterans Affairs Health-Care System. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:668– 675. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dominitz JA, Samsa GP, Landsman P, et al. Race, treatment, and survival among colorectal carcinoma patients in an equal-access medical system. Cancer. 1998;82:2312–2320. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980615)82:12<2312::aid-cncr3>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Rimm AA. Racial disparity in the incidence and case-fatality of colorectal cancer: analysis of 329 United States counties. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:283–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ries LA, Kosary CL, Hankey BF, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1973–1994. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, NIH; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weaver P, Harrison B, Eskander G, et al. Colon cancer in African-Americans: a disease with a worsening prognosis. JAMA. 1991;83:133–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Myers MH. Survival from cancer by blacks and whites. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1981;53:151–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagel S, Chung EB, DeWitty RL, Jr, et al. Colorectal cancer in young black patients. JAMA. 1988;80:37–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Cancer Society (ACS) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NCCN Aa, colon and rectal cancer treatment guidelines for patients. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2003. Version III. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Green FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health organization. International classification of diseases for oncology. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grizzle WE, Manne U, Jhala N, et al. The molecular characterization of colorectal neoplasia in translational research. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:91–98. doi: 10.5858/2001-125-0091-MCOCNI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grizzle WE, Manne U, Weiss HL, et al. Molecular staging of colorectal cancer in African-American and Caucasian patients using phenotypic expression of p53, Bcl-2, MUC-1 AND p27(kip-1) Int J Cancer. 2002;97:403–409. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Compton C, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Pettigrew N, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer prognostic factors consensus conference: colorectal working group. Cancer. 2000;88:1739–1757. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000401)88:7<1739::aid-cncr30>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:979–994. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0979-PFICC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blenkinsopp WK, Stewart-Brown S, Blesovsky L, et al. Histopathology reporting in large bowel cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1981;34:509–513. doi: 10.1136/jcp.34.5.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fleiss J. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaplan E, Meier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Roy Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allison P. Survival analysis using the SAS system: a practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kleinbaum D. Survival analysis: a self learning text. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mostafa G, Matthews BD, Norton HJ, et al. Influence of demographics on colorectal cancer. Am Surg. 2004;70:259–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen VW, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Wu XC, et al. Aggressiveness of colon carcinoma in blacks and whites. National Cancer Institute Black/White Cancer Survival Study Group. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, et al. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:247–257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, et al. Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:69–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rigau V, Sebbagh N, Olschwang S, et al. Microsatellite instability in colorectal carcinoma. The comparison of immunohistochemistry and molecular biology suggests a role for hMSH6 [correction of hMLH6] immunostaining. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:694–700. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-694-MIICC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim SB, Jeong SY, Lee MR, et al. Prognostic significance of microsatellite instability in sporadic colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:533–537. doi: 10.1007/s00384-004-0596-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carethers JM, Smith EJ, Behling CA, et al. Use of 5-fluorouracil and survival in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:394– 401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nasca PPH. Fundamentals of cancer epidemiology. 1. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robbins SCR, Kumar V. Pathologic basis of disease. 5. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyerhardt JA, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on outcomes in patients with colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:433–440. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: a population-based study. Cancer. 1998;82:2123–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dignam JJ, Colangelo L, Tian W, et al. Outcomes among African-Americans and Caucasians in colon cancer adjuvant therapy trials: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1933–1940. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.22.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCollum AD, Catalano PJ, Haller DG, et al. Outcomes and toxicity in African-American and Caucasian patients in a randomized adjuvant chemotherapy trial for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1160–1167. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dayal H, Polissar L, Yang CY, et al. Race, socioeconomic status, and other prognostic factors for survival from colorectal cancer. J Chron Dis. 1987;40:857–864. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90185-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]