Abstract

Type I interferons (IFNs) are cytokines with diverse biological properties, including antiviral, growth inhibitory, and immunomodulatory effects. Although several signaling pathways are activated during engagement of the type I IFN receptor and participate in the induction of IFN responses, the mechanisms of generation of specific signals for distinct biological effects remain to be elucidated. We provide evidence that a novel member of the protein kinase C (PKC) family of proteins is rapidly phosphorylated and activated during engagement of the type I IFN receptor. In contrast to other members of the PKC family that are also regulated by IFN receptors, PKCη does not regulate IFN-inducible transcription of interferon-stimulated genes or generation of antiviral responses. However, its function promotes cell cycle arrest and is essential for the generation of the suppressive effects of IFNα on normal and leukemic human myeloid (colony-forming unit-granulocyte macrophage) bone marrow progenitors. Altogether, our studies establish PKCη as a unique element in IFN signaling that plays a key and essential role in the generation of the regulatory effects of type I IFNs on normal and leukemic hematopoiesis.

Type I interferons (IFNs)2 exhibit important biological effects, including antiviral properties and regulation of normal and malignant cell growth (1–5). Inducible or constitutive production of IFNs appears to be a key component of cellular defense mechanisms against viral infections and the immunosurveillance against cancer (1–5). These cytokines exhibit important regulatory effects on cell cycle progression, gene transcription, and mRNA translation (6–11). Beyond their relevance in the regulation of innate responses, the important biological effects of IFNs have led to extensive clinical-translational work over the years that resulted in their introduction in clinical medicine as antiviral and antitumor agents, although they are also used in clinical neurology for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (4, 12, 13).

One of the most important biological activities of IFNs is their ability to act as regulators of normal hematopoietic progenitor cell growth and to control normal hematopoiesis. It has been known for the last 3 decades that type I IFNs are potent suppressors of hematopoietic progenitor cell growth in vitro (14–18), and such effects may account for the development of pancytopenias that patients receiving IFN treatment frequently develop. IFNs inhibit the growth of all different classes of normal bone marrow-derived hematopoietic precursors, including progenitors of myeloid (CFU-GM), erythroid (CFU-E and BFU-E) and megakaryocytic (CFU-MK) lineages (14–20). The effects of IFNs have been also shown to occur on cell populations that contain bone marrow cells at an early precursor stage (CD34+CD38–) (20), underscoring the ability of IFNs to regulate both early and late stages of hematopoietic development.

Over the years, the mechanisms of type I IFN signaling have been extensively studied and defined in a variety of cellular systems and backgrounds. Clearly, engagements of Jak kinases and Stat proteins are events of critical importance in the generation of the biological properties of IFNs (2–8). The activation of Jaks occurs at the receptor level, followed by direct activation of interacting Stats, providing a mechanism of rapid turnover of signals from the cell surface to the nucleus (2–8). Type I IFNs also activate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways that complement the function of Jak-Stat pathways and are required for optimal transcriptional activation of IFN-regulated genes (21–24). In addition, there is accumulating evidence that type I IFNs activate the Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin signaling pathway and its downstream effectors (25–28) and that such activation is required for the initiation of mRNA translation of interferon-stimulated genes (28). Members of the PKC family (δ, ε, and θ) have been shown previously to be activated and play roles in the generation of type I and/or type II IFN responses (29–33). However, much remains to be defined regarding the overall contribution of the PKC family to the generation of IFN responses as well as the specific roles of distinct isoforms in IFN signaling.

In this study we provide the first evidence for engagement of PKCη, a member of the novel subgroup of PKC isotypes in type I IFN signaling. Our data establish that this PKC isoform is phosphorylated/activated by IFNα or IFNβ treatment of sensitive cells. We also show that engagement of PKCη by the type I IFN receptor regulates IFNα-dependent G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and plays an essential role in the generation of the suppressive effects of type I IFNs on normal and leukemic myeloid (CFU-GM) progenitors. Altogether, our findings implicate PKCη as a novel member of the PKC family with an important role in the generation of IFN responses and define a unique and specific role for this PKC isoform in IFN-mediated control of myelopoiesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Reagents—The CML-derived lymphoblastoid crisis KT1 cell line, the multiple myeloma U266 cell line, and the acute myelomonocytic U937 cell line were grown in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. The osteosarcoma U20S cell line was grown in McCoy's media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. Primary human CD34+ progenitor cells were either purchased from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) or obtained from the bone marrow of normal donors after obtaining informed consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated using Histopaque (Sigma), and CD34+ cells were further purified using indirect positive selection (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), as in our previous studies (19, 34). Recombinant human IFNα was obtained from Hoffmann-La Roche. Recombinant IFNβ was obtained from Biogen Idec. An antibody against the phosphorylated form of PKCη on Ser-674 was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc. (Billerica, MA); an antibody against PKCη was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA), and an antibody against GAPDH was obtained from Chemicon (Billerica, MA). PKCη and PKCζ peptide inhibitors were purchased from Calbiochem. U937 cells were transfected by nucleofection following the manufacturer's protocol (Amaxa AG, Cologne, Germany). A constitutively active PKCη mutant (36) was provided by Dr. Gottfried Baier (Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria) and was used in overexpression experiments.

Cell Lysis and Immunoblotting—Cells were serum-starved, stimulated with 1 × 104 IU/ml of the indicated IFN for the indicated times, and subsequently lysed in phosphorylation buffer as described previously (19, 37). Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method were performed as in previous studies (19, 37).

Evaluation of Erythroid Differentiation—Human primary erythroid progenitor cells were enriched by in vitro culture of CD34+ cells isolated from normal bone marrows or obtained commercially from Stem Cell Technologies. After CD34+ cell isolation, differentiating erythroid progenitors were obtained by culturing cells for 4–14 days in medium with 15% fetal bovine serum, 15% human AB serum, 10 ng/ml interleukin-3, 2 units/ml erythropoietin, and 50 ng/ml stem cell factor (19, 35). At the indicated time points, an aliquot of cells was removed from culture, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, and stained with glycophorin A and CD71 or the appropriate antibody controls (BD Biosciences) prior to flow cytometric analysis.

RNA Isolation and PCR—Real time RT-PCR was performed as in our previous studies (27, 28). RNA was isolated using a standard methodology (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and used as substrate for reverse transcription reactions. Quantitative real time PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was then used to measure the relative expression of indicated mRNA transcripts with normalization to GAPDH. PCR was performed under the following conditions: 1 cycle at 50 °C for 2 min, 1 cycle at 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s followed by 1 min at 60 °C.

Hematopoietic Cell Progenitor Assays—Bone marrow from normal donors and bone marrow or peripheral blood from CML patients was collected after obtaining consent approved by the Institutional Review Board of Northwestern University. Mononuclear cells were isolated using Histopaque (Sigma) separation, and CD34+ cells were further purified using indirect positive selection (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Primary human CD34+ progenitor cells were also purchased from Stem Cell Technologies (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada). CD34+ cells were then transfected using transfection reagent purchased from Mirus (Madison, WI) with control siRNA or siRNAs targeting specific PKC isoforms. Two different siRNA targeting PKCη (Ambion ID777 and ID778), as well as siRNA targeting PKCα siRNA, PKCβ siRNA, PKCι siRNA, and control siRNA were purchased from Ambion (Foster City, CA). Growth of erythroid or myeloid progenitors was subsequently determined in clonogenic assays in methylcellulose, as in our previous studies (34, 38, 39). In some experiments progenitor colonies from methylcellulose cultures were plucked and used for RT-PCR analysis.

In Vitro Kinase Assays—Immune complex assays to detect the kinase activity of specified proteins were performed as in our previous studies (29). Briefly, cells were serum-starved, stimulated with 1 × 104 IU/ml of the indicated IFNs and then immunoprecipitated overnight with an anti-PKCη antibody or rabbit IgG as a control. Immunoprecipitates were then washed three times with phosphorylation lysis buffer and twice with kinase buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 20 μm ATP). Immunoprecipitated proteins were resuspended in 30 μl of kinase buffer to which 5 μg of histone H1 and 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP were added. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 20 min at room temperature prior to termination following the addition of SDS-sample buffer. Proteins were then analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated histone H1 was detected by autoradiography. The blot was subsequently immunoblotted with an anti-PKCη antibody.

Luciferase Assays—Cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and either an ISRE luciferase construct (22) or a luciferase reporter gene containing eight GAS elements linked to a minimal prolactin promoter (8×-GAS) (40), using the Superfect transfection reagent in accordance with the manufacturer's recommended procedure (Qiagen). The ISRE-luciferase construct was previously provided by Dr. Richard Pine (Public Health Research Institute, New York). The 8×-GAS construct was previously provided by Dr. Christopher Glass (University of California, San Diego). Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were either left untreated or treated with PKCη or PKCζ peptide inhibitors (Calbiochem) for 60 min. Following inhibitor incubation, triplicate cultures were then either left untreated or treated with 5 × 103 units/ml IFNα or IFNβ as indicated, and luciferase activity was measured as in our previous studies (22, 29). In addition, in some experiments U2OS cells were also transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector, an ISRE luciferase construct (22), and either an empty vector plasmid or a constitutively active PKCη mutant provided by Dr. Gottfried Baier (Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria) (36).

Evaluation of Apoptosis and Cell Cycle—Cells were transfected with the indicated plasmid constructs via nucleofection (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The evaluation of apoptosis was assessed by annexin V-propidium iodide staining using an apoptosis detection kit (Pharmingen), as in previous studies (41, 42). The evaluation of cell cycle was assessed by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometric analysis. Briefly, the cells were synchronized by serum starvation for 24 h, and then re-plated in media containing serum, pretreated with PKCη or PKCζ peptide inhibitor (Calbiochem) for 60 min, followed by treatment with 2500–3000 units/ml of IFNα for 24 h. Cells were then harvested, washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with ice-cold ethanol, and incubated for 20 min with propidium iodide (Sigma) prior to flow cytometric analysis.

Antiviral Assays—The antiviral effects of human IFNα and IFNβ were determined as in our previous studies (27), using EMCV as the challenge virus.

RESULTS

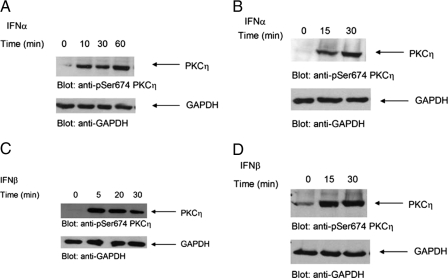

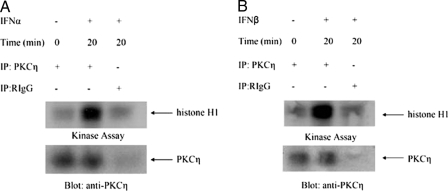

In initial studies, we sought to determine whether PKCη is phosphorylated in response to treatment of cells with different type I IFNs. We examined the effects of IFNα on the phosphorylation of PKCη in IFN-sensitive hematopoietic cell lines. KT1 or U266 cells were incubated in the presence or absence of IFNα for different times, and cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with an antibody against the phosphorylated form of PKCη against Ser-674. IFNα induced strong phosphorylation of PKCη in both cell lines studied (Fig. 1, A and B). Similarly, treatment of KT1 or U266 cells with another type I IFN, IFNβ, also resulted in strong phosphorylation of PKCη (Fig. 1, C and D). To directly determine whether the kinase domain of PKCη is activated in a type I IFN-dependent manner, experiments were performed in which lysates from IFNα- or IFNβ-treated cells were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PKCη antibody and subjected to in vitro kinase assays using histone H1 as an exogenous substrate. As shown in Fig. 2, treatment of cells with either IFNα (Fig. 2A) or IFNβ (Fig. 2B) resulted in PKCη kinase activity, indicating that the kinase domain of this PKC isoform is activated during its engagement by the type I IFN receptor.

FIGURE 1.

Type I IFN-dependent phosphorylation and activation of PKCη. A, KT1 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with IFNα for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PKCη or anti-GAPDH antibodies, as indicated. B, U266 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with IFNα for the indicated times. Cells were lysed and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PKCη or anti-GAPDH antibodies, as indicated. C, KT1 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with IFNβ for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PKCη or anti-GAPDH antibodies, as indicated. D, U266 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated with IFNβ for the indicated times. Cells were lysed, and lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PKCη or anti-GAPDH antibodies, as indicated.

FIGURE 2.

Type I IFN-dependent activation of PKCη. A, KT1 cells were serum-starved overnight, treated with IFNα for 20 min, and lysed in phosphorylation lysis buffer. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with an anti-PKCη antibody or control nonimmune rabbit immunoglobulin (RIgG) as indicated and subjected to in vitro kinase assays, using histone H1 as an exogenous substrate. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated histone H1 was detected by autoradiography. The blot from the kinase assay was subsequently immunoblotted with an anti-PKCη antibody to control for loading. B, KT1 cells were serum-starved overnight, treated with IFNβ for 20 min, and lysed in phosphorylation lysis buffer. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-PKCη antibody or control nonimmune rabbit immunoglobulin as indicated and subjected to in vitro kinase assays, using histone H1 as an exogenous substrate. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and phosphorylated histone H1 was detected by autoradiography. The blot from the kinase assay was subsequently immunoblotted with an anti-PKCη antibody to control for loading.

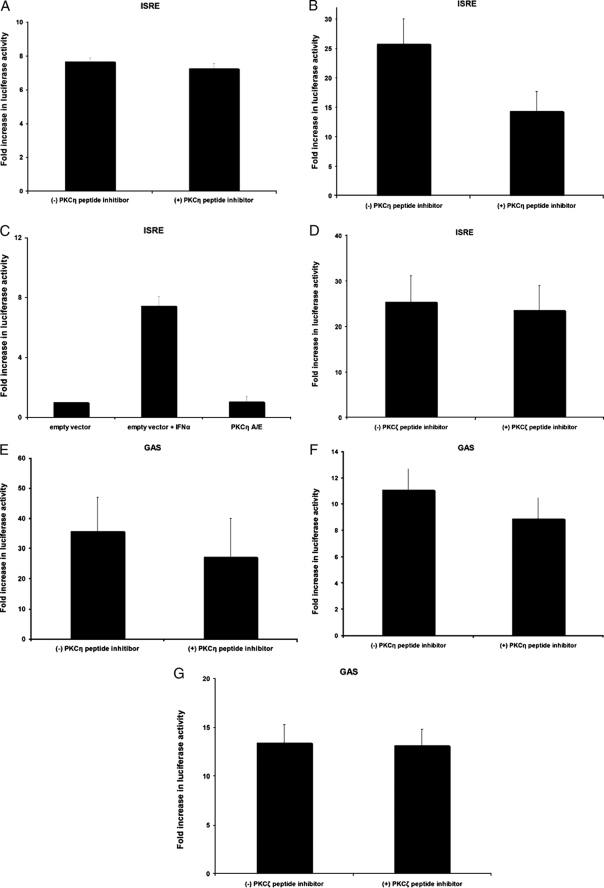

Previous work has shown that another member of the PKC family of isoforms, PKCδ, plays an important role in IFNα-dependent transcriptional regulation (20). To determine whether PKCη also regulates type IFN-dependent transcription, luciferase promoter assays were performed to determine the effects of PKCη inhibition on IFN-dependent transcriptional activity via ISRE or GAS elements. U2OS cells were transfected with either ISRE or 8×-GAS luciferase constructs and pretreated with a PKCη-specific peptide inhibitor prior to treatment with either IFNα or IFNβ. Luciferase activity was then measured and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Inhibition of PKCη activity had no significant effects on IFNα-inducible luciferase activity for ISRE elements (Fig. 3A). Similarly, although there was some minimal decrease in IFNβ-inducible luciferase activity in the presence of the PKCη peptide inhibited, there was still clear inducible IFNβ-dependent transcription (Fig. 3B), suggesting that PKCη activity is not essential for type I IFN-dependent transcriptional activation via ISRE elements. Consistent with this, overexpression of a constitutively active PKCη mutant did not result in enhanced transcription via ISRE elements (Fig. 3C). Pretreatment of cells with an inhibitor against an atypical PKC isoform, PKCζ (used as a control), had also no significant effects on type I IFN-dependent transcriptional activation via ISRE elements (Fig. 3D). Similarly, inhibition of either PKCη (Fig. 3, E and F) or PKCζ (Fig. 3G) activities had no significant effects on type I IFN-dependent transcription via GAS elements.

FIGURE 3.

Lack of regulatory effects of PKCη on type I IFN-induced gene transcription. A, U2OS cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and an ISRE-luciferase plasmid. Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absenceofa PKCη-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNα, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of three experiments. B, U2OS cells were transfected and treated with PKCη-specific peptide inhibitor as in A. Subsequently, cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNβ, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of six experiments. C, U2OS cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector, an ISRE-luciferase plasmid, and either an empty vector plasmid or a constitutively active PKCη-A/E construct. Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNα, as indicated, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control empty vector-transfected untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of three experiments. D, U2OS cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and an ISRE-luciferase plasmid. Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of a PKCζ-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNβ, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of five experiments. E, U2OS cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and an 8× GAS-luciferase plasmid. Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of a PKCη-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNα, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of three experiments. F, U2OS cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and an 8× GAS-luciferase plasmid. Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of a PKCη-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNβ, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of five experiments. G, U2OS cells were transfected with a β-galactosidase expression vector and an 8× GAS-luciferase plasmid. Forty eight hours after transfection, triplicate cultures were preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of a PKCζ-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, the cells were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of IFNβ, and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold increase in luciferase activity over control untreated cells and represent means ± S.E. of six experiments.

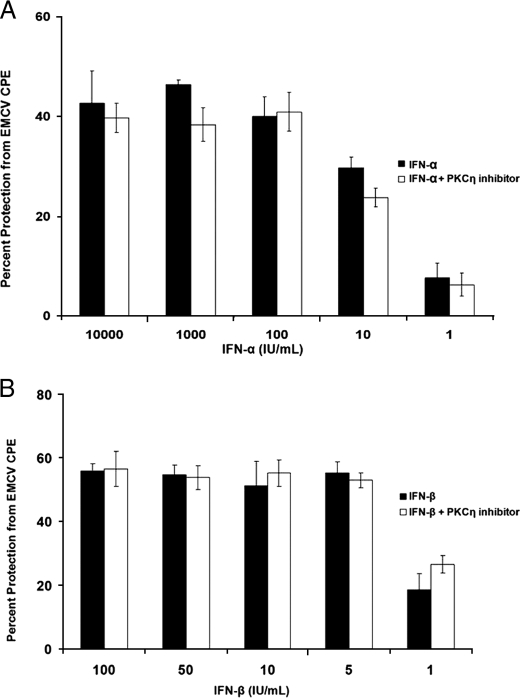

Because IFN-induced transcription is strongly associated with generation of IFN-dependent antiviral responses, we also assessed the effects of PKCη inhibition on antiviral activity. U2OS cells were pretreated with PKCη pseudo-substrate inhibitor and then challenged with EMCV. As shown in Fig. 4, both IFNα and IFNβ protected U2OS cells from the cytopathic effects of EMCV in a dose-dependent manner, but inhibition of PKCη activity did not reverse such IFN-induced antiviral protection (Fig. 4, A and B). Thus, in contrast to two other members of the group of novel PKC isoforms (δ and θ) whose activities are required for type I IFN-dependent gene transcription (29, 30), PKCη does not regulate transcriptional activation of interferon-stimulated genes or mediate induction of type I IFN-antiviral responses.

FIGURE 4.

Lack of regulatory effects of PKCη on type I IFN-induced antiviral responses. A, U20S cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the PKCη peptide inhibitor and treated with the indicated doses of IFNα, in triplicate. Cells were subsequently challenged with EMCV, and the direct cytopathic effect was quantified after 24 h. Data are expressed as the percentage of protection from the cytopathic effects of EMCV. B, U20S cells were incubated in the presence or absence of the PKCη peptide inhibitor and treated with the indicated doses of IFNβ, in triplicates. Cells were subsequently challenged with EMCV, and the direct cytopathic effect was quantified after 24 h. Data are expressed as the percentage of protection from the cytopathic effects of EMCV.

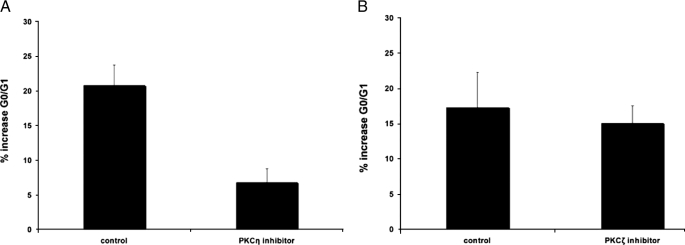

It is well established from previous work that type I IFN treatment induces G0/G1 cell cycle arrest in sensitive cells (43, 44), including KT1 cells (44), in which we demonstrated IFNα and IFNβ phosphorylation/activation of PKCη. To examine whether PKCη plays a role in the generation of type I IFN-dependent growth inhibitory responses, experiments were performed in which the requirement of PKCη in the induction of IFN-dependent G0/G1 arrest was examined. KT1 cells, synchronized by serum starvation, were treated with either a PKCη inhibitor or a PKCζ inhibitor, used as control. Both inhibitors were peptide pseudosubstrates specific for PKCη or PKCζ, respectively. The cells were then treated with IFNα for 24 h prior to flow cytometric analysis to evaluate cell cycle progression. As expected (44), IFNα treatment resulted in a substantial increase in the percentage of cells that were arrested in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle compared with control-treated cells (Fig. 5A). However, such an increase was attenuated in cells pretreated with the PKCη pseudosubstrate inhibitor (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, treatment of cells with the PKCζ pseudosubstrate inhibitor did not have any significant effects on such IFN-induced G0/G1 arrest (Fig. 5B), suggesting a specific role for PKCη in the process.

FIGURE 5.

PKCη inhibition increases G0/G1 arrest in cells treated with IFN. A, KT1 cells were synchronized by serum starvation for 24 h, re-plated in media containing serum, and preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of a PKCη-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, the cells were treated for 24 h in the presence or absence of IFNα prior to propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry analysis for cell cycle progression. The data were expressed as percent increase of cells in G0/G1 compared with untreated values, in cells treated with the PKCη peptide inhibitor versus controls. Means ± S.E. from six independent experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.000362. B, KT1 cells were synchronized by serum starvation for 24 h, re-plated in media containing serum, and preincubated for 1 h in the presence or absence of a PKCζ-specific peptide inhibitor. Subsequently, cells were incubated for 24 h in the presence or absence of IFNα prior to propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle progression. The data were expressed as percent increase of cells in G0/G1 compared with untreated values, in cells treated with the PKCζ peptide inhibitor versus controls. Means ± S.E. from four independent experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.6471.

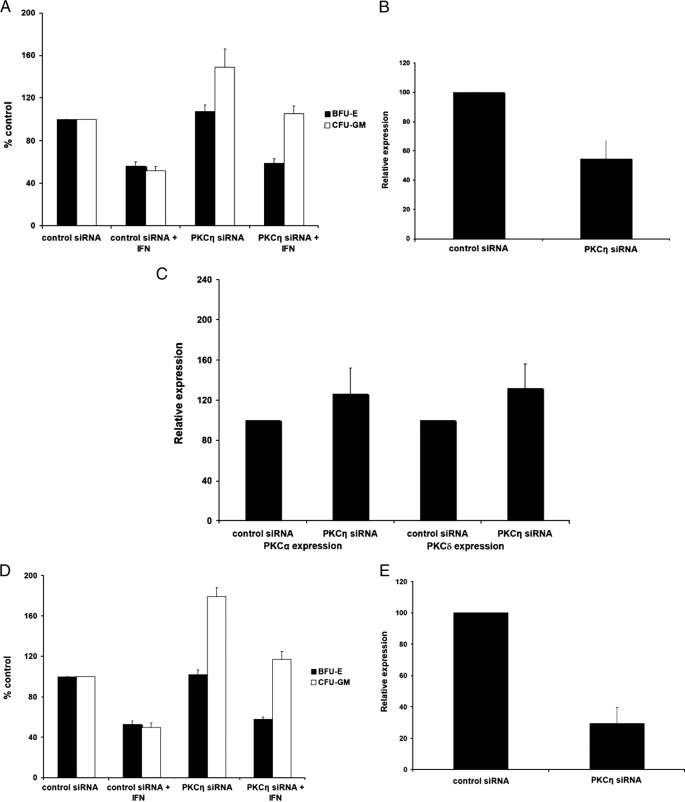

As our data suggested a selective role for PKCη in the induction of cell cycle arrest, we pursued further studies aimed to determine the role of this kinase in the generation of the regulatory effects of IFNα on normal hematopoiesis. Human bone marrow-derived CD34+ progenitors were transfected with PKCη siRNA or control siRNA, and the effects of PKCη knockdown on hematopoietic progenitor colony formation were assessed by clonogenic assays in methylcellulose (Fig. 6A). PKCη knockdown using the PKCη-specific siRNA (Fig. 6, B and C) had no significant effects on erythroid progenitor (BFU-E) colony growth and did not reverse generation of the inhibitory effects of IFNα on erythroid progenitors (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, there was a substantial and consistent increase in the number of CFU-GM colonies from bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells in which PKCη was knocked down (Fig. 6A). Importantly, PKCη knockdown reversed the growth inhibitory effects of IFNα-dependent suppression of CFU-GM colony formation. Such reversal of the effects of IFNα was complete and statistically significant, even when the base-line increase in CFU-GM colonies caused by PKCη siRNA was considered (Fig. 6A). Similar results (Fig. 6D) were obtained when a different siRNA targeting PKCη (Fig. 6E) was used.

FIGURE 6.

PKCη mediates myelosuppressive signals and its function is required for the effects of IFNα on normal myeloid (CFU-GM) progenitors. A, CD34+ progenitor cells were transfected with control siRNA or PKCη-specific siRNA and cultured in methylcellulose in the presence or absence of IFNα. After 14 days, BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data were expressed as percent colonies of control siRNA-treated cells. Means ± S.E. from five experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis comparing the IFNα-dependent percent inhibition of CFU-GM colony formation compared with untreated values in cells transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.01197. Similar statistical analysis for the effects on BFU-E colony formation showed a two-tailed p = 0.9792. B, expression of PKCη mRNA in progenitor cells derived from CD34+ cells, transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA, was examined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression compared with control siRNA-treated cells and represent means ± S.E. of three experiments. C, expression of PKCα and PKCδ mRNAs in progenitor cells derived from CD34+ cells, transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA, was examined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression compared with control siRNA-treated cells and represent means ± S.E. of four experiments. D, CD34+ progenitor cells were transfected with control siRNA or a different PKCη-specific siRNA than the one shown in A and cultured in methylcellulose in the presence or absence of IFNα. After 14 days, BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data were expressed as percent colonies of control siRNA-treated cells. Means ± S.E. from four experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis comparing the IFNα-dependent percent inhibition of CFU-GM colony formation compared with untreated values in cells transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.015279. Similar statistical analysis for the effects on BFU-E colony formation showed a two-tailed p = 0.28766. E, expression of PKCη mRNA in U937 cells transfected with control siRNA or the PKCη siRNA used in D was examined by quantitative real time RT-PCR. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression compared with control siRNA-treated cells and represent means ± S.E. of three experiments.

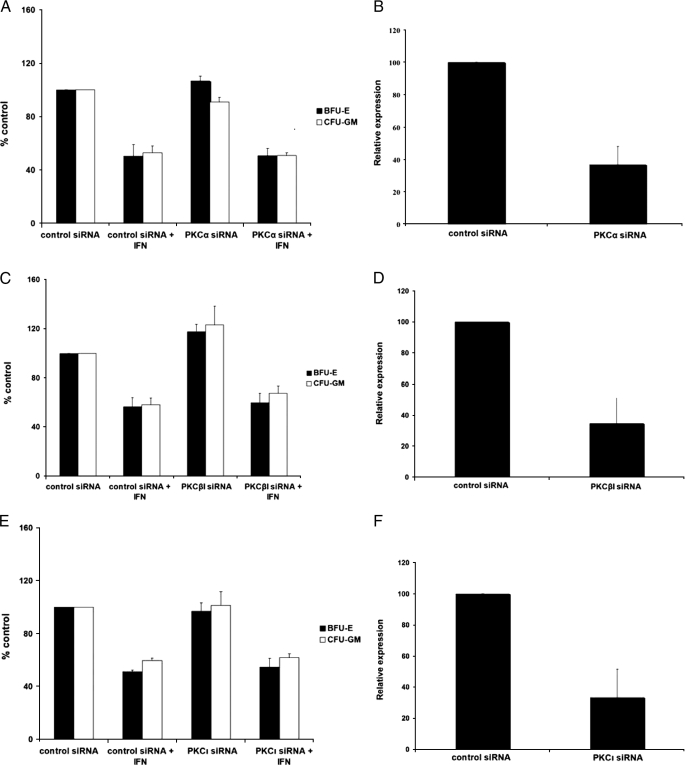

To confirm the specificity of these findings, additional experiments were performed in which different PKC isoforms (PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCι) were knocked down using specific siRNAs. In contrast to what we observed in the case of PKCη (Fig. 6, A and D), inhibition of expression of these isoforms in CD34+ progenitors did not reverse the suppressive effects of IFNα on myeloid CFU-GM colony formation (Fig. 7, A–F). Thus, in normal hematopoietic progenitor cells, inhibition of PKCη expression results in a lineage-selective attenuation of IFNα-induced colony suppression, establishing an important and specific role for this kinase in the generation of the effects of IFNα on hematopoiesis.

FIGURE 7.

Effects of PKCα, PKCβ, and PKCι knockdown on myeloid (CFU-GM) progenitor colony formation. A, CD34+ progenitor cells were transfected with control siRNA or PKCα-specific siRNA and cultured in methylcellulose in the presence or absence of IFNα. After 14 days, BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data were expressed as percent colonies of control siRNA-treated cells. Means ± S.E. from three independent experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis comparing the IFNα-dependent percent inhibition of CFU-GM colony formation compared with untreated values in cells transfected with control siRNA or PKCα siRNA, demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.2256. Similar statistical analysis for the effects on BFU-E colony formation showed a two-tailed p = 0.5373. B, expression of PKCα mRNA in progenitor cells derived from CD34+ cells, transfected with control siRNA or PKCα siRNA, was examined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression compared with control siRNA-treated cells, and represent means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. C, CD34+ progenitor cells were transfected with control siRNA or PKCβ-specific siRNA and cultured in methylcellulose in the presence or absence of IFNα. After 14 days, BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data were expressed as percent colonies of control siRNA-treated cells. Means ± S.E. from five independent experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis comparing the IFNα-dependent percent inhibition of CFU-GM colony formation with untreated values in cells transfected with control siRNA or PKCβ siRNA demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.44447. Similar statistical analysis for the effects on BFU-E colony formation showed a two-tailed p = 0.1846. D, expression of PKCβ mRNA in progenitor cells derived from CD34+ cells, transfected with control siRNA or PKCβ siRNA, was examined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression compared with control siRNA-treated cells, and represent means ± S.E. of three independent experiments. E, CD34+ progenitor cells were transfected with control siRNA or PKCι-specific siRNA and cultured in methylcellulose in the presence or absence of IFNα. After 14 days, BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data were expressed as percent colonies of control siRNA-treated cells. Means ± S.E. from three independent experiments are shown. Two-tailed paired t test analysis comparing the IFNα-dependent percent inhibition of CFU-GM colony formation with untreated values in cells transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.6517. Similar statistical analysis for the effects on BFU-E colony formation showed a two-tailed p = 0.2064. F, expression of PKCι mRNA in progenitor cells derived from CD34+ cells, transfected with control siRNA or PKCι siRNA, was examined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression compared with control siRNA-treated cells, and represent means ± S.E. of three independent experiments.

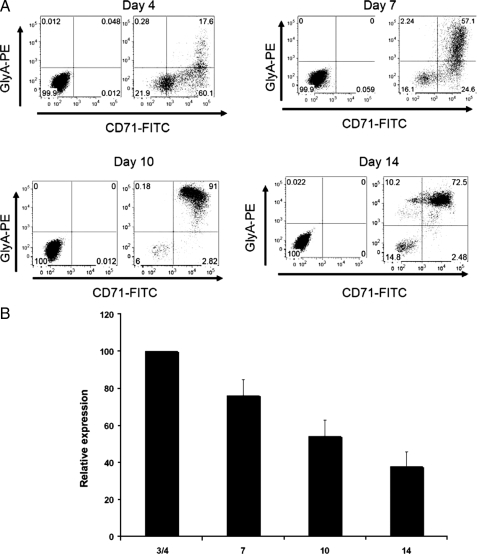

As our data demonstrated a requirement for PKCη in the generation of myelosuppressive effects of IFNα on myeloid but not erythroid progenitors, we sought to determine whether the lack of requirement for PKCη in the generation of suppressive effects on the erythroid lineage correlates with decreased expression of the kinase during erythropoiesis. Consistent with our previous studies (35), CD34+ progenitor cells cultured in vitro in the presence of a cytokine mixture (35) were driven toward erythroid differentiation, as determined by flow cytometric analysis using double labeling for glycophorin A and CD71 (Fig. 8A). Relative PKCη mRNA expression steadily decreased throughout erythroid development, and its expression in day 14 erythroid progenitors was clearly less than the expression levels seen in early erythroid progenitor cells (Fig. 8B), suggesting that relative PKCη expression is down-regulated during erythropoiesis. Thus, the specific effects of PKCη on myeloid but not erythroid progenitors correlate with down-regulation of PKCη expression during erythropoiesis, further suggesting a selective role for this kinase in the control of human myelopoiesis.

FIGURE 8.

Decreased expression of PKCη during erythroid differentiation. A, CD34+ progenitor cells were cultured for 14 days, as described under “Materials and Methods.” Glycophorin A and CD71 (transferrin receptor) levels were monitored by flow cytometry at various time points during the maturation program. The panels on the left show the isotype controls, and the panels on the right show the expression levels for GlyA and CD71. B, CD34+ progenitor cells were cultured for 14 days. mRNA was isolated at the indicated time points, and quantitative RT-PCR using PKCη-specific primers was used to determine PKCη expression at different times. All samples were normalized to GAPDH. Data are expressed as relative expression, calculated as percent expression of day 3/4 values. Data represent means ± S.E. of three experiments.

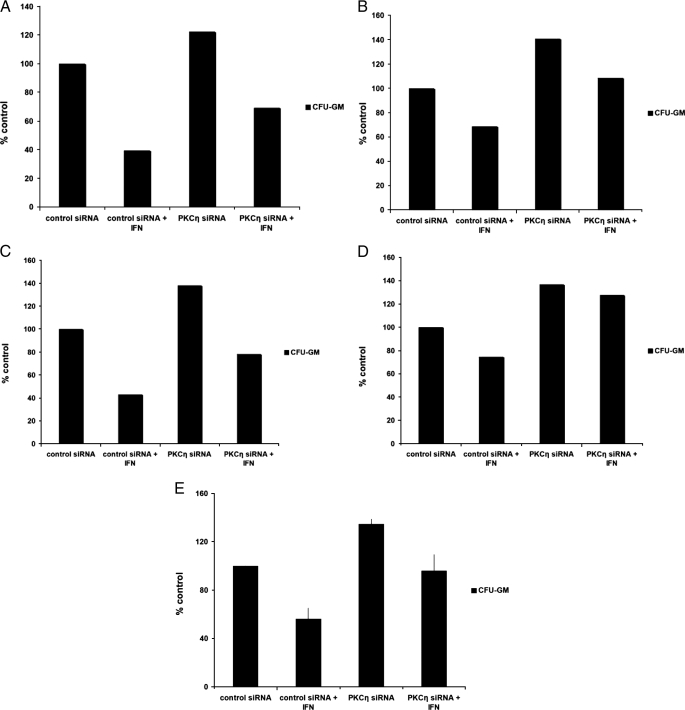

Beyond being a suppressor of normal human myeloid progenitor growth, IFNα has potent inhibitory effects against chronic myelogenous leukemia CFU-GM progenitors (4, 39) and has major clinical activity in the treatment of CML patients. To determine whether PKCη plays a role in the generation of the antileukemic effects of IFNα on leukemic CFU-GM progenitors, the effects of PKCη knockdown were examined, using samples from different CML patients. The growth-suppressive effects of IFNα on CML-derived CFU-GM colonies were attenuated in CML progenitor cells transfected with siRNA targeting PKCη but not control siRNA (Fig. 9, A–E). Thus, in addition to its regulatory effects on normal myelopoiesis and its requirement for the induction of growth suppression by IFNs, PKCη plays a critical role in the generation of antileukemic responses in chronic myeloid leukemia cells.

FIGURE 9.

Inhibition of PKCη attenuates IFN-induced myelosuppression in primary CML progenitor cells. A–D, CD34+ progenitor cells derived from either bone marrow or peripheral blood from four different patients with CML (A–D) were transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA and cultured in methylcellulose in the presence or absence of IFNα, as indicated. Leukemic CFU-GM colonies were scored on day 14 in culture. E, data from the experiments shown in A–D were combined and are expressed as means ± S.E. Two-tailed paired t test analysis comparing the IFNα-dependent percent inhibition of CFU-GM colony formation compared with untreated values in cells transfected with control siRNA or PKCη siRNA, demonstrated a two-tailed p = 0.00763.

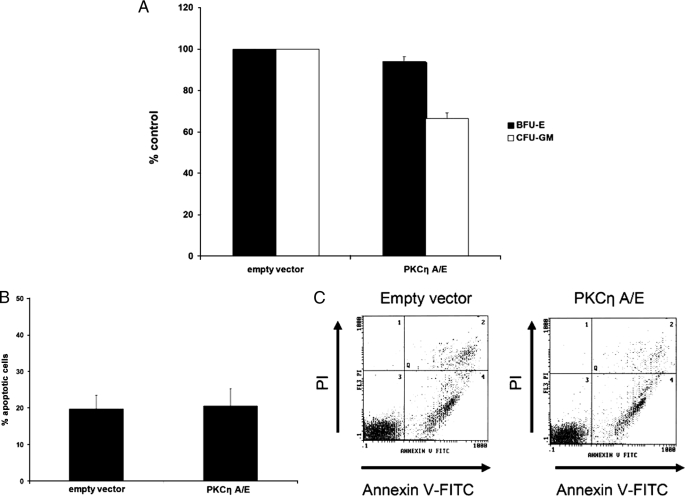

To further evaluate the mechanisms via which PKCη mediates growth inhibitory effects in hematopoietic cells, we determined the effects of overexpression of a constitutively active PKCη mutant on myeloid colony formation, as well as apoptosis. Overexpression of a constitutively active PKCη mutant resulted in a statistically significant suppression of formation of myeloid (CFU-GM) but not erythroid (BFU-E) colonies in clonogenic assays in methylcellulose (Fig. 10A). Notably, overexpression of active PKCη in a myeloid cell line did not induce apoptosis (Fig. 10, B and C), suggesting that its suppressive effects on myeloid progenitor growth result from effects on cell cycle progression and not induction of apoptosis.

FIGURE 10.

Catalytically active PKCη decreases myeloid colony growth but does not promote apoptosis. A, CD34+ progenitor cells were transfected with empty vector plasmid or a construct containing a constitutively active form of PKCη and cultured in methylcellulose. After 14 days, BFU-E and CFU-GM colonies were counted. The data were expressed as percent colonies of empty vector-treated cells. Means ± S.E. from four independent experiments are shown. Paired t test analysis for the effects on CFU-GM showed a p value = 0.0005229. B, U937 cells were either transfected with control empty vector or a constitutively active PKCη A/E construct. 24 h following transfection, apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis following annexin V/propidium iodide staining. Data are expressed as percent early and late apoptotic cells and represent means ± S.E. of five independent experiments. C, representative scatter plot of one of the experiments shown in B.

DISCUSSION

The PKC family includes at least 11 serine/threonine kinase members that regulate a wide variety of biological responses during their activation by diverse cellular signals (45–49). The members of this family are grouped in three major subfamilies, based on motifs present in their structure and their activation patterns and requirements. These include the classical (α, βI, βII, and γ), novel (δ, ε, η, μ, and θ), and atypical (ζ and ι/λ) PKC isoforms (45–49). The classical PKC isotypes possess two cysteine-rich motifs in their regulatory domains and require Ca2+ and a phospholipid for their activation (45–49). The novel isoforms (δ, ε, η, μ, and θ) are activated by diacylglycerol and phorbol esters, as are the classic isoforms. However, unlike the classic PKC isoforms, novel PKC activation is Ca2+-independent (45–49). Finally, the atypical isoforms (ζ and ι/λ) are activated independently of Ca2+, diacylglycerol, or phorbol esters and share the least homology with either the classic or novel isoforms (45–49).

Over the years there has been extensive accumulating evidence that different members of the PKC family participate in the induction of diverse functional and biochemical responses, depending on the cellular context, the triggering stimulus, and the isoform involved. Different PKC isotypes have been shown to play important roles in the regulation of cell survival and apoptosis, as well as gene transcription and differentiation (45–51). Importantly, several PKC isoforms have been implicated in the regulation of different aspects of normal hematopoiesis (reviewed in Refs. 48, 52) and have been found to be involved in signaling for various hematopoietic growth factors, including erythropoietin, thrombopoietin, and stem cell factor (48, 52–56). Beyond their roles in various signaling pathways in normal cells, it is now well established that certain members of the PKC family are abnormally activated in different types of malignant cells, including leukemic cells (45, 58–63). In fact, as the PKC family of kinases plays an important role in the pathophysiology of various solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, there are emerging efforts toward the development of new pharmacological agents or other means to target members of the PKC family in the treatment of cancer (64–66). The diversity of PKC signaling and the wide spectrum of biological functions regulated by this family of proteins underscores the need to better define the specific functions of distinct isotypes in different cellular systems. Remarkably, different PKC isoforms can regulate opposing cellular functions, depending on the context of their engagement and activation. For example, PKCδ mediates primarily pro-apoptotic responses (67, 68), but it can also mediate antiapoptotic effects (69). In contrast, PKCα mediates mitogenic signals (70–72), although generation of anti-tumor responses is positively controlled by PKCδ (68) and negatively by PKCα (73). It is likely that a balance between the function of different PKC isoforms is required for optimal control of several biological responses, but the precise contribution of different PKC isoforms in such systems remains to be defined.

There has been accumulating evidence over the last few years implicating PKCs in type I and II IFN signaling (29–33, 74, 75). A particularly interesting finding has been the identification of PKCδ as a kinase that regulates phosphorylation of Stat1 on serine 727 in response to both type I (29, 31) and type II IFNs (75). These data have established a critical role for this PKC isoform in IFN signaling, via its ability to regulate optimal transcription of IFN-sensitive genes that participate in induction of the biological effects of IFNs. Notably, the function of this PKC isoform in IFN signaling exhibits some cell type specificity, as there is evidence that at least one additional PKC isoform, PKCε (33, 75), also functions as a serine kinase for Stat1 in response to IFNγ in different cell types. Thus, it is possible that other PKC isoforms or non-PKC serine kinases (76) compensate for the serine kinase activity of PKCδ in certain cell types, highlighting the significance of the existence of the multiple distinct isoforms of the PKC family.

In this study, we examined the activation and functional relevance of PKCη, another novel member of the PKC family of proteins, in the generation of IFN responses. Our data provide the first evidence that this PKC isoform is rapidly activated in response to IFNα or IFNβ treatment of cells. Interestingly, in experiments to define its role in IFN-generated cellular responses, we found that engagement of PKCη does not regulate type I IFN-dependent transcription. Thus, in contrast to the roles that two other isoforms, PKCδ (29) and PKCθ (30), play in the regulation of type I IFN-dependent transcriptional activation via ISRE or GAS elements, PKCη does not exhibit such function in IFN signaling. Our data suggest that PKCη functions at a post-transcriptional level and has effects on IFN-dependent cell cycle arrest.

In experiments to determine the requirement of PKCη activity in the generation of the myelosuppressive effects of IFNα on normal hematopoietic progenitors, we found that PKCη activity is essential for the generation of the suppressive effects of IFNs on myeloid (CFU-GM) but not erythroid progenitors (BFU-E). Interestingly, PKCη targeting also enhanced myeloid colony formation from normal bone marrows, suggesting a regulatory role for this PKCη isoform on normal myelopoiesis but not erythropoiesis. This finding is of high interest as it relates to the cell type and context specificity of PKC-mediated biological outcomes. In hematopoietic cells, the specific functional roles of members of the PKC family remain largely unknown. There has been some evidence for selective expression of certain PKC isoforms in murine progenitor cell clones and human CD34+ progenitor cells (77). It also appears there is also some selectivity in the expression of distinct isoforms in CD34+ progenitors versus terminally differentiated hematopoietic cells (53). However, the functional implications of such expression remain to be defined. Our studies demonstrating down-regulation of PKCη during progression of erythropoiesis and selective PKCη functional responses on myeloid cells suggest a specific developmental and functional role of this isoform in normal human myelopoiesis. As it is likely that a balance between growth factors and hematopoietic suppressor cytokines is required for optimal regulation of normal hematopoiesis, the involvement of PKCη in IFNα signaling in hematopoietic precursor cells further suggests an important role for this cytokine in the regulation of normal hematopoiesis.

Our studies also provide the first evidence that this PKC isoform is involved in the generation of the antileukemic effects of IFNα in chronic myeloid leukemia cells, as evidenced by the reversal of IFNα-dependent growth inhibitory responses on CML-derived leukemic CFU-GM progenitors in vitro. Interestingly, as with several other PKC isoforms, the regulatory effects of PKCη on tumorigenesis and malignant cell growth vary depending on the cellular context, and in some cases appear to be opposing. On the one hand, PKCη-deficient mice display an exaggerated response to phorbol ester-induced tumor formation (79), suggesting that PKCη plays a key role in suppressing tumorigenesis. Similarly, via its regulatory effects on cell cycle progression, PKCη appears to promote growth inhibitory effects and/or cell differentiation in different systems (80–82). On the other hand, it has been shown that PKCη expression is associated with the development of resistance of Hodgkin lymphoma cell lines to chemotherapy-induced apoptosis (83) and promotes proliferation of glioblastoma cell lines via the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/Elk-1 pathway (57). Moreover, PKCη has been implicated in the up-regulation of multidrug-resistant associated genes in different types of tumors (78). Clarifying the determinants that account for the diversity of functional responses in response to this PKC isotype in malignant cells should provide important insights on the mechanisms of regulation of growth and survival of malignant cells. Our findings, establishing a novel and specific function for PKCη in type IFN signaling, provide the first link between this PKC isoform and IFNs, cytokines that are potent inhibitors of malignant cell growth and key agents in the immunosurveillance against cancer. Further studies to identify specific elements in normal myeloid or myeloid leukemia cells that may interact and be regulated by the IFN-activated form of PKCη may ultimately lead to the identification of novel cellular targets for the development of new translational efforts in the treatment of malignancies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gottfried Baier (Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria) for providing us the constitutively active PKCη mutant.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA77816, CA100579, and CA121192 (to L. C. P.) and CA098550 (to A. W.). This work was also supported by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs (to L. C. P.), Predoctoral National Research Service Award F30ES015668 (to A. J. R.), and a Malkin Scholars Award (to A. J. R.).

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: IFN, interferon; PKC, protein kinase C; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; siRNA, short interfering RNA; RT, reverse transcription; ISRE, interferon-stimulated response element; CFU-GM, colony-forming unit-granulocyte macrophage; BFU-E, burst-forming unit-erythroid; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; EMCV, encephalomyocarditis virus.

References

- 1.Pestka, S., Langer, J. A., Zoon, K. C., and Samuel, C. E. (1987) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56 727–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stark, G. R., Kerr, I. M., Williams, B. R., Silverman, R. H., and Schreiber, R. D. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67 227–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Platanias, L. C., and Fish, E. N. (1999) Exp. Hematol. 27 1583–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parmar, S., and Platanias, L.C. (2003) Curr. Opin. Oncol. 15 431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borden, E. C., Sen, G. C., Uze, G., Silverman, R. H., Ransohoff, R. M., Foster, G. R., and Stark, G. R. (2007) Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6 975–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darnell, J. E., Jr., Kerr, I. M., and Stark, G. R. (1994) Science 264 1415–1421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darnell, J. E., Jr. (1997) Science 277 1630–1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platanias, L. C. (2005) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5 375–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stark, G. R. (2007) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18 419–423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaur, S., Katsoulidis, E., and Platanias, L. C. (2008) Cell Cycle 7 2112–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grandér, D., Sangfelt, O., and Erickson, S. (1997) Eur. J. Haematol. 59 129–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman, R. M. (2008) Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 65 158–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moschos, S., Varanasi, S., and Kirkwood, J. M. (2005) Cancer Treat. Res. 126 207–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van't Hull, E., Schellekens, H., Löwenberg, B., and de Vries, M. J. (1978) Cancer Res. 38 911–914 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broxmeyer, H. E., Lu, L., Platzer, E., Feit, C., Juliano, L., and Rubin, B. Y. (1983) J. Immunol. 131 1300–1305 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raefsky, E. L., Platanias, L. C., Zoumbos, N. C., and Young, N. S. (1985) J. Immunol. 135 2507–2512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broxmeyer, H. E., Cooper, S., Rubin, B. S., and Taylor, M. W. (1985) J. Immunol. 135 2502–2506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Means, R. T., Jr., and Krantz, S. B. (1993) J. Clin. Investig. 91 416–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verma, A., Deb, D. K., Sassano, A., Uddin, S., Varga, J., Wickrema, A., and Platanias, L. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 7726–7735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weekx, S. F., Van Bockstaele, D. R., Plum, J., Moulijn, A., Rodrigus, I., Lardon, F., De Smedt, M., Nijs, G., Lenjou, M., Loquet, P., Berneman, Z. N., and Snoeck, H. W. (1998) Exp. Hematol. 26 1034–1039 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uddin, S., Lekmine, F., Sharma, N., Majchrzak, B., Mayer, I., Young, P. R., Bokoch, G. M., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 27634–27640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uddin, S., Majchrzak, B., Woodson, J., Arunkumar, P., Alsayed, Y., Pine, R., Young, P. R., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 30127–30131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goh, K. C., Haque, S. J., and Williams, B. R. (1999) EMBO J. 18 5601–5608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Platanias, L. C. (2003) Pharmacol. Ther. 98 129–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lekmine, F., Uddin, S., Sassano, A., Parmar, S., Brachmann, S. M., Majchrzak, B., Sonenberg, N., Hay, N., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 27772–27780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thyrell, L., Hjortsberg, L., Arulampalam, V., Panaretakis, T., Uhles, S., Dagnell, M., Zhivotovsky, B., Leibiger, I., Grandér, D., and Pokrovskaja, K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 24152–24162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaur, S., Lal, L., Sassano, A., Majchrzak-Kita, B., Srikanth, M., Baker, D. P., Petroulakis, E., Hay, N., Sonenberg, N., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 1757–1768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaur, S., Sassano, A., Dolniak, B., Joshi, S., Majchrzak-Kita, B., Baker, D. P., Hay, N., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 4808–4813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uddin, S., Sassano, A., Deb, D. K., Verma, A., Majchrzak, B., Rahman, A., Malik, A. B., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 14408–14416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srivastava, K. K., Batra, S., Sassano, A., Li, Y., Majchrzak, B., Kiyokawa, H., Altman, A., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 29911–29920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao, K. W., Li, D., Zhao, Q., Huang, Y., Silverman, R. H., Sims, P. J., and Chen, G. Q. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 42707–42714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivaska, J., Bosca, L., and Parker, P. J. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5 363–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Venkatesan, B. A., Mahimainathan, L., Ghosh-Choudhury, N., Gorin, Y., Bhandari, B., Valente, A. J., Abboud, H. E., and Choudhury, G. G. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18 508–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katsoulidis, E., Li, Y., Yoon, P., Sassano, A., Altman, J., Kannan-Thulasiraman, P., Balasubramanian, L., Parmar, S., Varga, J., Tallman, M. S., Verma, A., and Platanias, L. C. (2005) Cancer Res. 65 9029–9037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uddin, S., Ah-Kang, J., Ulaszek, J., Mahmud, D., and Wickrema, A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 147–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandlin, I., Hubner, S., Eiseler, T., Martinez-Moya, M., Horschinek, A., Hausser, A., Link, G., Rupp, S., Storz, P., Pfizenmaier, K., and Johannes, F. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 6490–6496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Uddin, S., Fish, E. N., Sher, D., Gardziola, C., Colamonici, O. R., Kellum, M., Pitha, P. M., White, M. F., and Platanias, L. C. (1997) Blood 90 2574–2582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parmar, S., Katsoulidis, E., Verma, A., Li, Y., Sassano, A., Lal, L., Majchrzak, B., Ravandi, F., Tallman, M. S., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 25345–25352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parmar, S., Smith, J., Sassano, A., Uddin, S., Katsoulidis, E., Majchrzak, B., Kambhampati, S., Eklund, E. A., Tallman, M. S., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2005) Blood 106 2436–2443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horvai, A. E., Xu, L., Korzus, E., Brard, G., Kalafus, D., Mullen, T.-M., Rose, D. W., Rosenfeld, M. G., and Glass, C. K. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 1074–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kannan-Thulasiraman, P., Katsoulidis, E., Tallman, M. S., Arthur, J. S., and Platanias, L. C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 22446–22452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giafis, N., Katsoulidis, E., Sassano, A., Tallman, M. S., Higgins, L. S., Nebreda, A. R., Davis, R. J., and Platanias, L. C. (2006) Cancer Res. 66 6763–6771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sangfelt, O., Erickson, S., and Grander, D. (2000) Front. Biosci. 1 479–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yanagisawa, K., Yamauchi, H., Kaneko, M., Kohno, H., Hasegawa, H., and Fujita, S. (1998) Blood 15 641–648 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Breitkreutz, D., Braiman-Wiksman, L., Daum, N., Denning, M. F., and Tennenbaum, T. (2007) J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 133 793–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Griner, E. M., and Kazanietz, M. G. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 281–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Larsson, C. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18 276–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Redig, A. J., and Platanias, L. C. (2007) J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 27 623–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mackay, H. J., and Twelves, C. J. (2007) Nat. Rev. Cancer 7 554–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reyland, M. E. (2007) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35 1001–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kashiwagi, M., Ohba, M., Chida, K., and Kuroki, T. (2002) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 132 853–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vitale, M., Gobbi, G., Mirandola, P., Ponti, C., Sponzilli, I., Rinaldi, L., and Manzoli, F. A. (2006) Eur. J. Histochem. 50 15–18 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oshevski, S., Le Bousse-Kerdiles, M. C., Clay, D., Levashova, Z., Debili, N., Vitral, N., Jasmin, C., and Castagna, M. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 263 603–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gobbi, G., Mirandola, P., Sponzilli, I., Micheloni, C., Malinverno, C., Cocco, L., and Vitale, M. (2007) Stem Cells (Dayton) 25 2322–2329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Di Baldassarre, A., Di Rico, M., Di Noia, A., Bonfini, T., Iacone, A., Marchisio, M., Miscia, S., Alfani, E., Migliaccio, A. R., Stamatoyannopoulos, G., and Migliaccio, G. (2007) J. Cell. Biochem. 101 411–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Myklebust, J. H., Smeland, E. B., Josefsen, D., and Sioud, M. (2000) Blood 95 510–518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Uht, R. M., Amos, S., Martin, P. M., Riggan, A. E., and Hussaini, I. M. (2007) Oncogene 26 2885–2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aziz, M. H., Manoharan, H. T., Sand, J. M., and Verma, A. K. (2007) Mol. Carcinog. 46 646–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fährmann, M. (2008) Curr. Med. Chem. 15 1175–1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Podar, K., Raab, M. S., Chauhan, D., and Anderson, K. C. (2007) Exp. Opin. Investig. Drugs 16 1693–1707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Redig, A. J., and Platanias, L. C. (2008) Leuk. Lymphoma 49 1255–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barragán, M., Campàs, C., Bellosillo, B., and Gil, J. (2003) Leuk. Lymphoma 44 1865–1870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hofmann, J. (2004) Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 4 125–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin, P. M., and Hussaini, I. M. (2005) Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 9 299–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chen, Y. B., and LaCasce, A. S. (2008) Exp. Opin. Investig. Drugs 17 939–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fields, A. P., Frederick, L. A., and Regala, R. P. (2007) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35 996–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.DeVries-Seimon, T. A., Ohm, A. M., Humphries, M. J., and Reyland, M. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 22307–22314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hampson, P., Chahal, H., Khanim, F., Hayden, R., Mulder, A., Assi, L. K., Bunce, C. M., and Lord, J. M. (2005) Blood 106 1362–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Okhrimenko, H., Lu, W., Xiang, C., Ju, D., Blumberg, P. M., Gomel, R., Kazimirsky, G., and Brodie, C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 23643–23652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Magnifico, A., Albano, L., Campaner, S., Campiglio, M., Pilotti, S., Ménard, S., and Tagliabue, E. (2007) Cancer Res. 67 5308–5317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu, T. T., Hsieh, Y. H., Hsieh, Y. S., and Liu, J. Y. (2008) J. Cell. Biochem. 103 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guertin, D. A., Stevens, D. M., Thoreen, C. C., Burds, A. A., Kalaany, N. Y., Moffat, J., Brown, M., Fitzgerald, K. J., and Sabatini, D. M. (2006) Dev. Cell 11 859–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hanauske, A. R., Sundell, K., and Lahn, M. (2004) Curr. Pharm. Des. 10 1923–1936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choudhury, G. G. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 27399–27409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Deb, D. K., Sassano, A., Lekmine, F., Majchrzak, B., Verma, A., Kambhampati, S., Uddin, S., Rahman, A., Fish, E. N., and Platanias, L. C. (2003) J. Immunol. 171 267–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nair, J. S., DaFonseca, C. J., Tjernberg, A., Sun, W., Darnell, J. E., Jr., Chait, B. T., and Zhang, J. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 5971–5976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bassini, A., Zauli, G., Migliaccio, G., Migliaccio, A. R., Pascuccio, M., Pierpaoli, S., Guidotti, L., Capitani, S., and Vitale, M. (1999) Blood 93 1178–1188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Beck, J., Bohnet, B., Brügger, D., Bader, P., Dietl, J., Scheper, R. J., Kandolf, R., Liu, C., Niethammer, D., and Gekeler, V. (1998) Br. J. Cancer 77 87–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chida, K., Hara, T., Hirai, T., Konishi, C., Nakamura, K., Nakao, K., Aiba, A., Katsuki, M., and Kuroki, T. (2003) Cancer Res. 63 2404–2408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kashiwagi, M., Ohba, M., Watanabe, H., Ishino, K., Kasahara, K., Sanai, Y., Taya, Y., and Kuroki, T. (2000) Oncogene 19 6334–6341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ohba, M., Ishino, K., Kashiwagi, M., Kawabe, S., Chida, K., Huh, N. H., and Kuroki, T. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 5199–5207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Livneh, E., Shimon, T., Bechor, E., Doki, Y., Schieren, I., and Weinstein, I. P. (1996) Oncogene 12 1545–1555 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Abu-Ghanem, S., Oberkovitz, G., Benharroch, D., Gopas, J., and Livneh, E. (2007) Cancer Biol. Ther. 6 1375–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]