Abstract

The aim of this work is to study the role of pore residues on drug binding in the NaV1.8 channel. Alanine mutations were made in the S6 segments, chosen on the basis of their roles in other NaV subtypes; whole cell patch clamp recordings were made from mammalian ND7/23 cells. Mutations of some residues caused shifts in voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, and gave faster time course of inactivation, indicating that the residues mutated play important roles in both activation and inactivation in the NaV1.8 channel. The resting and inactivated state affinities of tetracaine for the channel were reduced by mutations I381A, F1710A, and Y1717A (for the latter only inactivated state affinity was measured), and by mutation F1710A for the NaV1.8-selective compound A-803467, showing the involvement of these residues for each compound, respectively. For both compounds, mutation L1410A caused the unexpected appearance of a complete resting block even at extremely low concentrations. Resting block of native channels by compound A-803467 could be partially removed (“disinhibition”) by repetitive stimulation or by a test pulse after recovery from inactivation; the magnitude of the latter effect was increased for all the mutants studied. Tetracaine did not show this effect for native channels, but disinhibition was seen particularly for mutants L1410A and F1710A. The data suggest differing, but partially overlapping, areas of binding of A-803467 and tetracaine. Docking of the ligands into a three-dimensional model of the NaV1.8 channel gave interesting insight as to how the ligands may interact with pore residues.

Voltage-gated Na+ channels are essential for the initiation and propagation of action potentials in excitable cells and are the molecular targets for local anesthetics and other compounds (1, 2). The major structural component of voltage-gated Na+ channels is a large (230–270kDa) α-subunit, which is alone sufficient to form a functional Na+ conducting channel. This subunit contains four homologous domains (I–IV), each containing six membrane-spanning segments (S1–S6) (3). In response to membrane depolarization, an outward movement of the positively charged S4 segments induces the conformational changes in the pore leading to the conducting activated state (4). The channels then enter inactivated states within a few milliseconds of channel opening.

To date, nine distinct α-subunit subtypes (NaV1.1 to NaV1.9) have been identified that differ in their primary structure, ionic permeation, tissue distribution, functional properties, and pharmacology (5). The NaV1.8 channel is responsible for the slowly-inactivating tetrodotoxin-insensitive Na+ current of small diameter neurons of dorsal root ganglion cells (6–8), and is a promising target for the development of anti-nociceptive drugs (9). The NaV1.8 channel plays a clear role in pain signaling following noxious mechanical and cold stimulation, and particularly in inflammation-induced thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia (10–14), although the role of this channel in neuropathic pain is less certain (10, 15–18). The NaV1.7 channel also plays a role in pain signaling; indeed lack of function of the NaV1.7 channel in congenital disorders leads to insensitivity to certain types of pain (19).

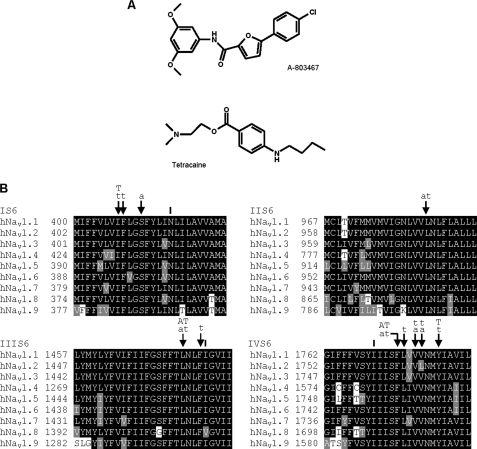

Local anesthetics and other chemically related agents bind selectively to the open or inactivated state of sodium channels, leading to use-dependent block during periods of repetitive firing or sustained depolarization (20). Using site-directed mutagenesis, the molecular determinants for drug block in NaV1.2 to NaV1.5 sodium channels were identified as a number of key pore-lining amino acid residues of the IS6, IIIS6, and IVS6 segments (21, 22). These S6 residues correspond to NaV1.8 amino acids Ile381, Asn390 in domain I, Leu1410, Asn1411, Val1414 in domain III, and Ile1706, Phe1710, Tyr1717 in domain IV (Fig. 1). These mutations also produced appreciable shifts in the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation, supporting the role of S6 segment amino acid residues in the gating mechanisms. Thus, the transmembrane S6 segments appear to be important for both the functional properties and drug binding in a number of NaV subtypes.

FIGURE 1.

A, the structures of the compounds tetracaine and A-803467. B, alignments of the S6 segments of different human NaV subtypes. The figure also summarizes results from this study. The residues indicated are shown in this study to be important for the affinity of tetracaine (T) and A-803467 (A) using mutagenesis, or tetracaine (t) and A-803467 (a) using computational modeling. The residues indicated (|) did not appear to be important for the binding of tetracaine or A-803467 by mutagenesis or by computational modeling.

The NaV1.8 channel shows both slower kinetics and more depolarized voltage-dependent activation and inactivation than other NaV subtypes (6–8), although the voltage dependence of inactivation of human NaV1.8 occurs at less depolarized potentials (23). Furthermore, despite highly homologous S6 segments between NaV1.8 and the other subtypes, differences in drug action from the other subtypes have been observed. For example, compared with tetrodotoxin-sensitive channels, use-dependent block by lidocaine is more pronounced for NaV1.8 (24, 25) and remarkably, inactivated state block by compound A-803467 is more than 100-fold more selective for NaV1.8 (9). The latter compound also showed greater inactivated state block of the human NaV1.8 channel than the rat channel (9). These properties have led to the speculation that compound A-803467 may not bind to the usual local anesthetic binding site (26). Furthermore, compound A-803467 showed an unusual removal of resting block (“disinhibition”) for the human NaV1.8 channel during repetitive stimulation.2

Whereas the role of the S6 transmembrane segments in voltage-gated Na+ channel functional properties and drug binding is well established for other subtypes, and the key residues have been identified (see above), the corresponding residues for the NaV1.8 subtype are yet to be investigated. Here we have used whole-cell patch clamp to study the functional properties of mutant NaV1.8 channels containing alanine substitutions at the corresponding key positions in the S6 segments. The effect of these mutations on the action of compound A-803467 (Fig. 1) on the NaV1.8 channel was investigated, and compared with the actions of tetracaine (Fig. 1), to further understand the action of this compound, which selectively acts on this promising therapeutic target for anti-nociceptive drugs. In this study for the first time the drug binding sites of the NaV1.8 channel have been addressed, and furthermore, we have investigated the human channel in an appropriate mammalian host background more like the native situation, rather than in oocytes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutagenesis of Human Nav1.8 Channels—The human NaV1.8 α-subunit (Swiss-Prot accession Q9Y5Y9, polymorph 1073V, Ref. 7) in the pFastBacMam1 vector (27) was used in this study. Mutant channels I381A, N390A, L1410A, V1414A, I1706A, F1710A, and Y1717A were generated using the QuikChange XL Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) together with appropriate mutagenic primers. All mutations were validated by restriction mapping and sequencing of the entire channel cDNA.

ND7/23 cells (ECACC, Salisbury, UK) were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 2 mm l-glutamine, 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 1× non-essential amino acids. Cells were seeded at 60% confluence and co-transfected with 3.0 μg of wild type or mutant NaV1.8 α-subunit cDNA and 0.3 μg of EBO-pCD-Leu2 cDNA (for CD8 marker) or pEGFP-N1 cDNA (for fluorescence marker) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Transfection-positive cells were identified 2–4 days after transfection with Immunobeads (anti-CD8 Dynabeads; Invitrogen) or green fluorescence.

Electrophysiological Recording and Data Analysis—Whole-cell patch clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (20–22 °C) using patch pipettes pulled from thin-walled borosilicate glass capillaries and coated with Sigmacote (Sigma). Pipettes (tip resistances 1.5–2.5 MΩ) were filled with solution containing (mm): CsF, 120; HEPES, 10; EGTA, 10; and NaCl, 15 adjusted to pH 7.2 with CsOH. Cells were continuously perfused with an external solution containing (mm): NaCl, 140; HEPES, 5; MgCl2, 1.3; CaCl2, 1; glucose, 11; and KCl, 4.7, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. Tetrodotoxin (200 nm, Tocris) was used to block endogenous Na+ channel currents.

Cells were allowed to equilibrate for 10 min in the whole-cell configuration before currents were acquired using an Axopatch-1C or Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices) filtered at 5 kHz, and sampled at 10 kHz using pClamp8 or pClamp9 software (Clampex; Molecular Devices). The online P/4 subtraction procedure was used to subtract linear leak and capacitance currents where appropriate. Clampfit versions 9 or 10 (Molecular Devices) and Origin version 5.0 (MicroCal Inc.) were used for offline data analysis.

Conductance-voltage curves were determined from the peak sodium current (INa), using the equation: GNa = INa/(V - ENa), where V is the membrane potential and ENa is the reversal potential obtained from the I–V curve for each cell. These curves were fit with the Boltzmann equation: G = Gmax/(1 + exp((V½ - V)/k)), where Gmax is maximum conductance, V½ is the potential for half-maximal activation, and k is the slope factor. Voltage-dependence of inactivation curves were fit with the Boltzmann equation: I = A +(B - A)/(1 + exp((V - V½)/k)), where B is the maximum current, A is the amplitude of a non-inactivating component, V½ is the potential for half-maximal inactivation.

Inactivation time constants were obtained by fitting the decay phase of individual currents with double exponential fits. Recovery from inactivation was studied in twin pulse experiments, and the time course of recovery was fit with double exponentials; in the presence of some drugs used, a third exponential was required.

All test compounds were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide and diluted to the desired concentration in the external solution giving a final concentration of ≤1% dimethyl sulfoxide. Control test currents were recorded before the application of compounds. Compounds were applied during a 3–4-min incubation period after which currents were recorded in the continual presence of test compound. The dissociation constants for resting channels (Kr) and inactivated channels (Ki) were determined using the model of Kuo and Bean (28) as described by Liu et al. (29) and Yarov-Yarovoy et al. (30). The resting state drug dissociation constant was calculated using a test pulse before and after drug application from a resting potential of -120 mV, at which channels are in the resting state. The dissociation constants were determined using Kr = [D]/((1/IDr) - 1), where D is the concentration of test compound and IDr is the peak test current amplitude in the presence of drug expressed as a fraction of the peak test current amplitude in the absence of drug. The protocol for obtaining inactivated state dissociation constants is shown in Fig. 5C, where a 4-s depolarizing pulse was used to inactivate currents, and a test pulse before and after drug application was used to measure the extent of inactivated current block. The inactivated state dissociation constants were calculated using Ki = [D](1 - h)/((1/IDi) - 1), where D is the concentration of test compound, h is the fraction of non-inactivated sodium current (in the absence of the compound) following the 4-s depolarization, and IDi is the peak test current amplitude in the presence of drug expressed as a fraction of the peak test current amplitude in the absence of drug (Fig. 5C). The voltage of the 4-s depolarizing pulse was chosen to always give approximately the same (60–80%) inactivation in wild type and mutant channels; the measurement of the Ki value should therefore only represent the effect of the mutation on drug binding rather than any effect of the mutation on inactivation itself. Indeed, in previous work the effects of mutations on inactivation and on the Ki value were not found to correlate (29, 30). Statistics are presented as mean ± S.E., and the Student's t test was used to test significance.

FIGURE 5.

Dissociation constants for resting and inactivated states of mutant NaV1.8 channels. A, bar diagrams are shown representing mutant NaV1.8 channel resting state dissociation constants (Kr) for tetracaine. Values were calculated for tetracaine at 10 μm for wild type NaV1.8 (n = 6) and mutations I381A (n = 7), N390A (n = 8), V1414A (n = 5), I1706A (n = 6), and F1710A (n = 4). B, bar diagrams are shown representing resting state dissociation constants (Kr) for compound A-803467. Values were calculated for A-803467 at 100 nm for wild type NaV1.8 (n = 5) and mutations I381A (n = 4), N390A (n = 9), V1414A (n = 6), I1706A (n = 2), and F1710A (n = 7). It was not possible to determine the resting state dissociation constant for mutation Y1717A under the conditions used here, because a large proportion (23%) of channels are inactivated at a holding potential of -120 mV as a consequence of the strong negative shift in the inactivation curve. C, the figure shows the twin pulse protocol used to determine the inactivated state affinities (Ki). This was used before and after test compound application; the depicted 4-s depolarizing pulse was to potentials such that 60–80% inactivation was observed. In the case of mutant Y1717A, the resting level of inactivation at -120 mV (as above) was taken into account in obtaining the parameter h. D, the figure shows example current traces elicited by the pulse protocol in C, where currents in bold are before test compound application and fine traces are after test compound application; the currents larger in magnitude correspond to the control pulses and currents smaller in magnitude correspond to the test pulse following a 4-s depolarization. E, bar diagrams are shown representing mutant NaV1.8 channel-inactivated state dissociation constants (Ki) for tetracaine. Values were calculated for tetracaine at 1–10 μm for wild type NaV1.8 (n = 7) and mutations I381A (n = 6), N390A (n = 6), V1414A (n = 6), I1706A (n = 5), F1710A (n = 7), and Y1717A (n = 7). F, bar diagrams are shown representing mutant NaV1.8 channel-inactivated state dissociation constants (Ki) for compound A-803467. Values were calculated for A-803467 at 10–100 nm for wild type NaV1.8 (n = 7) and mutations I381A (n = 6), N390A (n = 7), V1414A (n = 5), I1706A (n = 6), F1710A (n = 7), and Y1717A (n = 7). *, p < 0.05.

Computational Modeling of the Human Nav1.8 Channel and Docking of Drugs—Previous models of sodium channels described in the literature have been based on bacterial potassium channel structures. More recently, however, a structure of the rat KV1.2 potassium channel has been solved (31). It was considered that this would be closer in structure to human NaV1.8, and our model was therefore based on its homology with this structure (PDB code 2A79). Our model consisted of the S5 helices, P-loop, and S6 helices (along with the short linker between the P-loop and the S6 helix in the first domain). Whereas sequence alignments between the rat KV1.2 channel and NaV1.8 domains were unsuccessful; Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy plots (32) were used to identify the S5-P-loop-S6 region of each domain. Alignment of the loops was made so as to form a good filter geometry with the DEKA residues. Alignment of the S6 regions was straightforward and was based on the conserved glycine (serine in domain IV). The alignment of the S5 helices was not obvious so use was made of the conservation moment method using the HELANAL program (33). The starting structure was constructed manually using the homology tools within the Quanta program (Wavefunction Inc.). This was subsequently refined by energy minimization with CHARMm (34). Initially the backbone was held fixed but this was subsequently relaxed and the helices were maintained by using distance (“nuclear Overhauser effect”) constraints between the backbone amide bonds. 500 steps of Steepest Descent followed by 5000 steps of Adopted Basis Newton-Rhaphson were used for the minimization phases. The Karplus rotamer library (35) was used to set the side chain dihedral angles at standard values. The two ligands were constructed with the Spartan program using HF-3–21G* charges (accelrys.com). They were docked manually into the protein in multiple poses, ensuring each time that initial side chain dihedral angles were set at the rotamer library values. Each pose was minimized as above and ranked according to interaction energy.

RESULTS

Effects of S6 Segment Mutations on the Functional Properties of the NaV1.8 Channel—Mutations were chosen at positions in the S6 segments of domains I, III, and IV of the NaV1.8 channel, corresponding to the positions found in other NaV channel subtypes where a number of drugs have been found to act (21, 22). Example current traces for each human NaV1.8 channel mutation are shown in Fig. 2. The voltage dependence of activation (Fig. 3A) was measured at a holding potential of -120 mV. Conductance-voltage relationships for some of the mutant NaV1.8 channels showed shifts in the curves as compared with wild type channels (Fig. 3A); a 9-mV shift to more positive potentials was observed for mutations N390A and V1414A (Fig. 3B), and negative shifts of ∼6 mV were observed for mutations I381A and F1710A. The V½ for activation was unaffected by mutations L1410A, I1706A, and Y1717A. The k values were not affected by most of the mutations, although there were small but significant reductions for two of the mutants (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 2.

Example current traces for human NaV1.8 channels. Current traces are shown for ND7/23 cells transfected with wild type or mutant hNaV1.8 channel cDNA in the presence of 200 nm tetrodotoxin. Currents were elicited for voltage steps to -100 to +60 mV (in 10-mV increments) from a holding potential of -120 mV. The peak current amplitudes were -79 ± 7 pA/pF (n = 79) for wild type NaV1.8, -53 ± 5 pA/pF (n = 50) for mutant I381A, -112 ± 21 pA/pF (n = 52) for mutant N390A, -32 ± 5 pA/pF (n = 31) for mutant L1410A, -64 ± 6 pA/pF (n = 58) for mutant V1414A, -35 ± 4 pA/pF (n = 38) for mutant I1706A, -69 ± 7 pA/pF (n = 45) for mutant F1710A, and -40 ± 3 pA/pF (n = 54) for mutant Y1717A.

FIGURE 3.

Effects of S6 mutations on Na+ channel activation and inactivation. A, conductance-voltage curves are shown for wild type NaV1.8 (▪, n = 79), and mutations I381A (•, n = 50), N390A (▴, n = 52), L1410A (▾, n = 31), V1414A (□, n = 58), I1706A (○, n = 38), F1710A (Δ, n = 45), and Y1717A (▿, n = 54). Curves were fit with the Boltzmann equation and normalized to maximum conductance. The pulse protocol is shown in the inset. B, bar diagrams show the voltage for half-maximal activation (V½) and the slope factor (k) for wild type and mutant channels (same experiments as in A). C, curves are shown for the voltage dependence of inactivation for wild type NaV1.8 (▪, n = 84), and mutations I381A (•, n = 13), N390A (▴, n = 14), L1410A (▾, n = 6), V1414A (□, n = 25), I1706A (○, n = 12), F1710A (Δ, n = 18), and Y1717A (▿, n = 14). The curves were fit with the Boltzmann equation and normalized to the maximum current. The pulse protocol is shown in the inset. D, bar diagrams (same experiments as C) showing the voltage for half-maximal inactivation (V½), and the amplitude of the non-inactivated component normalized to the maximum current (A/B, see “Experimental Procedures”). *, p < 0.05. E, the inset shows example currents for wild type and mutant (V1414A) NaV1.8 channels elicited by a voltage step to 0 mV from a holding potential of -120 mV. Current traces were normalized and superimposed. The time constant, τ, obtained from the inactivation time course is shown for wild type NaV1.8 (▪, n = 56), and mutations I381A (•, n = 35), N390A (▴, n = 34), L1410A (▾, n = 32), V1414A (□, n = 36), I1706A (○, n = 32), F1710A (Δ, n = 37), and Y1717A (▿, n = 38), for the test potentials shown. F, bar diagrams are shown for the mean values of the time constant of inactivation, τ, for each mutant at -10 mV test potential (same experiments as in E). *, p < 0.05.

To study the effects of the mutations on the voltage dependence of inactivation (Fig. 3C), a 4-s prepulse to various potentials was used to inactivate channels followed by a test pulse to 0 mV (holding potential -120 mV). The steady-state inactivation curves show that all the mutations except F1710A showed shifts to more negative potentials (Fig. 3, C and D). The k values were not significantly affected as compared with wild type (10.5 ± 0.4 mV, n = 84), except for mutations L1410A (decrease in k to 6.4 ± 0.4 mV, n = 6) and Y1717A (increase in k to 15.6 ± 1.2 mV, n = 14). For wild type channels, inactivation was not complete even at very positive inactivating potentials (A/B parameter in Fig. 3D, see “Experimental Procedures”); mutations I1706A, F1710A, and Y1717A (all located in the IVS6 segment) showed even less complete inactivation at positive potentials.

During depolarizing pulses, inactivation kinetics were faster than wild type for the mutations. An example current trace for V1414A, and the voltage dependence of the inactivation time constant are shown in Fig. 3E for all the mutants. It can be seen that the time constants were generally reduced for the mutants, particularly at the -10 mV test potential (Fig. 3F). Thus the mutations studied here enter inactivated states from open states faster than the wild type NaV1.8 channel.

Binding Sites for Tetracaine and A-803467 at Inactivated Wild Type Channels—Tetracaine and A-803467 have been shown to bind preferentially to inactivated rather than resting wild type NaV1.8 channels (9, 36). Drugs that preferentially act on the inactivated state rather than on the resting state show a hyperpolarizing shift in the steady-state inactivation curve (ΔV) without altering the slope (k) (37). The magnitude of the shift in the inactivation curve may be used to determine whether tetracaine and A-803467 act on the same binding site. Inactivation curves were obtained in the presence and absence of 10 μm tetracaine (Fig. 4A), 150 nm A-803467 (Fig. 4B). The values obtained for these shifts agree with the predictions calculated from a model with single binding sites (37) (Fig. 4D). For both drugs applied together (at concentrations of 5 μm tetracaine and 75 nm A-803467, Fig. 4C), the shift clearly agrees with the predicted value for overlapping binding sites, rather than separate binding sites for each drug, again using the models in Ref. 37 (Fig. 4D). Details of the formula used in these models are given in Fig. 4, legend.

FIGURE 4.

Binding sites for tetracaine and A-803467 on the wild type NaV1.8 channel. The figure shows steady-state inactivation curves for (A) tetracaine (10 μm, ○, n = 4), (B) A-803467 (150 nm, ○, n = 4), and (C) tetracaine (5 μm) plus A-803467 (75 nm)(○, n = 8). Control curves in the absence of drug are shown (•, paired values in each case). The protocol used was as in Fig. 3C, and Boltzmann curves fit as before. The shifts in the inactivation curves (ΔV½) were determined and are shown in D. Predicted values of the shifts are shown for separate binding sites and for overlapping binding sites using the model of Kuo (37). Briefly, in this model, in the presence of a single drug of concentration ([D]), and affinity Ki, the shift is given by ΔV = k(ln(1 + ([D]/Ki))). For both drugs applied together, if the two drugs act on an overlapping site, the shift of the inactivation curve is given by ΔV = k(ln(1 + ([D1]/Ki1) + ([D2]/Ki2))), where [D1] and [D2] are the concentrations of each drug with the respective Ki values Ki1 and Ki2. In contrast, if the two drugs act on separate sites, then the shift in the inactivation curve is given by ΔV = k(ln(1 + ([D1]/Ki1) + ([D2]/Ki2) + ([D1]/Ki1)([D2]/Ki2))). For the predictions in D, values of Ki are as indicated in Fig. 5, and values of k for each drug application were obtained from the above inactivation curves, taking mean values in each case.

Affinity of Tetracaine and A-803467 for Resting and Inactivated Mutant NaV1.8 Channels—To determine the site of action for tetracaine and A-803467 on the NaV1.8 channel, here we have studied the effects of S6 mutations on both the resting and inactivated state affinities.

In the resting state (holding potential -120 mV), the extent of block of a test pulse current by the compounds was used to measure the affinity of compounds for the resting state (more precisely, dissociation constant, Kr, see “Experimental Procedures”). For tetracaine, the resting state affinity was significantly reduced (i.e. dissociation constants were increased) for mutations I381A and F1710A as compared with wild type channels (Fig. 5A). For compound A-803467, an appreciable decrease in the resting state affinity was only observed for mutation F1710A (Fig. 5B). Thus residues Ile381 and Phe1710 are involved in the resting state binding of tetracaine, whereas residue Phe1710 is involved in resting state binding of compound A-803467.

To calculate the inactivated state affinity of test compounds for mutant NaV1.8 channels, a twin pulse protocol (Fig. 5C) was used before and after application of tetracaine or A-803467. Before compound application, the fractional amount of non-inactivated current during the test pulse after a 4-s depolarization (h, see “Experimental Procedures”) was obtained from the ratio of test to control pulse peak amplitude. After compound application, the fraction of test current not blocked by the compounds (IDi, see “Experimental Procedures”) was measured and the inactivated state dissociation constant, Ki, calculated from h and IDi. Example currents are shown in Fig. 5D. Mutations I381A, F1710A, and Y1717A showed marked decreases in affinity for tetracaine (Fig. 5E). For compound A-803467, only mutation F1710A caused a decrease in the inactivated state affinity (Fig. 5F). Thus residue Phe1710 is important in determining both resting and inactivated state affinities for both tetracaine and A-803467, whereas residues Ile381 and Tyr1717 are also important for tetracaine binding. The effects of test compounds on mutant L1410A channels are considered separately in the next section.

Tetracaine and A-803467 Drug Block of NaV1.8 Mutation L1410A—Data for the affinity of mutant L1410A channels could not readily be obtained using the above protocols because even concentrations 1000 times smaller than used in the previous section still gave almost complete resting block (Fig. 6A) (indicating very high resting state affinities of >10 nm for tetracaine, and >100 pm for A-803467), and also because of unusual behaviors under repetitive stimulation (Fig. 6B). As can be seen in the latter figure, in the presence of tetracaine or A-803467, during repetitive stimulation at 10 Hz, currents surprisingly increased from almost zero to values comparable with currents before test compound, as if stimulation removed the unusually high affinity resting block of the compounds (disinhibition).

FIGURE 6.

Disinhibition of resting block for mutation L1410A. A, the figure shows example L1410A mutant currents in the absence and presence of very low concentrations (indicated) of tetracaine and A-803467. The current traces were elicited by a test pulse to 0 mV from a holding potential of -120 mV. B, currents, Inorm, for mutant L1410A NaV1.8 channels are shown during a 10-Hz train of pulses (10-ms duration to 0 mV from a holding potential of -120 mV), plotted against pulse number and normalized to the first pulse of the untreated cell. The currents are shown before the application of tetracaine (▪, n = 6) or A-803467 (•, n = 8) and after tetracaine (10 nm, □) or A-803467 (100 pm, ○) in paired cells. C, as shown in the protocol, current amplitude was measured at a test pulse following a 600-ms depolarizing pulse to 0 mV and a 100-ms recovery period. D, the bar diagrams show the mean currents using the protocol in C, before (filled bars) and after (unfilled bars) the application of tetracaine (10 nm, n = 5) or compound A-803467 (100 pm, n = 6) in paired cells.

To determine whether sustained depolarization would show a similar effect, a 600-ms conditioning depolarizing pulse was first applied, followed 100 ms later (to allow for recovery from inactivation) by a test pulse (Fig. 6C). The 600-ms pulse is comparable with the 60 10-ms pulses used during repetitive stimulation. Although current during the conditioning pulse was almost completely blocked by tetracaine or A-803467, the test current was comparable with that in the absence of the compounds (Fig. 6D). Thus it appears that depolarization removes the high-affinity resting block of the compounds, underlying the process of disinhibition.

The Effect of A-803467 and Tetracaine on the Recovery from Inactivation of S6 Segment Mutations—The effects of A-803467 and tetracaine on the recovery from inactivation (in the continual presence of the compound) were investigated using the protocol shown in the inset in Fig. 7C. Following the application of A-803467, the time course for recovery involved not simply the removal of inactivation, but also an additional component with increased current above resting control values (disinhibition), apparently due to partial removal of the resting block by stimulation in the presence of the compound. This effect, although small for wild type, can be seen from example current traces (Fig. 7A). The effect can also be seen for mean current values in Fig. 7C, where all currents have been normalized to control pulse amplitude in the absence of the compound. Recovery from disinhibition followed a very slow time course (1.7 ± 0.2 s, Fig. 7F).

FIGURE 7.

The effect of A-803467 on the recovery from inactivation. Example NaV1.8 channel currents are shown for wild type (A) and V1414A mutant (B) in the presence or absence of A-803467 (100 nm). Currents were elicited by an initial control pulse (to 0 mV), followed by test pulses (to 0 mV) at the indicated times during recovery (protocol shown in the inset of C). The graphs show the test pulse amplitude normalized to control pulse during the recovery from inactivation for wild type (C), and example mutations, V1414A (D) and L1410A (E), using the protocol shown in the inset. Time courses of recovery from inactivation are shown before (▪) and after (•) the application of A-803467 (100 nm, except 100 pm for L1410A) in paired cells. F, bar diagrams are shown for the amplitude (Idis, normalized to extent of resting current block) and time course (τ) of the slowest component of the three-exponential fit to the time course of recovery of inactivation for wild type (n = 5), and mutants I381A (n = 7), N390A (n = 7), L1410A (n = 5), V1414A (n = 6), I1706A (n = 2), and F1710A (n = 7). The dotted line in C–E represents the level of resting block.

For the mutants in the presence of compound A-803467 (100 nm), this disinhibitory component was larger than for wild type. For instance, example current traces for V1414A clearly show the effect (Fig. 7B), as do the mean current values for V1414A and L1410A (Fig. 7, D and E). For the latter mutant (with almost zero current in the resting state in the presence of the compound at 100 pm), marked disinhibitory current was seen, corresponding to extensive removal of resting block during stimulation (Fig. 7E). Data for all the mutants are summarized in Fig. 7F, where it can be seen that the disinhibitory component (expressed as a fraction of the current blocked at rest by the compound) is greater for all the mutants considered than for wild type. For mutant Y1717A (not shown in the figure), currents were too small to be measured in the presence of 100 nm A-803467; however, even at 10 nm, disinhibition was much greater than for wild type at 10 nm. All mutants (except for I1706A) showed a similar time constant for the recovery of this disinhibitory component (Fig. 7F).

For tetracaine (10 μm), by contrast, the wild type channel showed no component of disinhibition, as can been seen from the example of current traces (Fig. 8A), and the currents during recovery shown in Fig. 8C. On the other hand, mutant L1410A showed a striking disinhibitory component in the presence of tetracaine (Fig. 8D). For mutant F1710A, a clear disinhibitory component was observed in the presence of tetracaine (Fig. 8, B and E); this component was relatively large when expressed as a fraction of the resting block (Fig. 8F). For the other mutants, disinhibitory components were observed in detailed fits to the time course but their amplitudes relative to extent of resting block were small (Fig. 8F). Time constants of recovery were in the range 0.8 to 1.8 s (Fig. 8F). Taken together the data show that for tetracaine, mutations L1410A and F1710A clearly induced the disinhibitory component, whereas for compound A-803467, all the mutations considered led to more pronounced disinhibitory components. The time course of recovery of this component appears to be simply a reflection of the time course of reinstatement of the resting block. It is also noteworthy that the extent of disinhibition (Figs. 7F and 8F) for each mutant did not correlate with the effects of the mutations themselves on inactivation (Fig. 3), suggesting that disinhibition is not the result of altered channel function per se.

FIGURE 8.

The effect of tetracaine on the recovery from inactivation. Example NaV1.8 channel currents are shown for wild type (A) and F1710A mutant (B) in the presence or absence of tetracaine (10 μm). Currents were elicited by an initial control pulse (to 0 mV), followed by test pulses (to 0 mV) at the indicated times during recovery (protocol shown in the inset of C). The graphs show the test pulse amplitude normalized to control pulse during the recovery from inactivation for wild type (C), and example mutations, L1410A (D) and F1710A (E), using the protocol shown in the inset. Time courses of recovery from inactivation are shown before (▪) and after (•) the application of tetracaine (10 μm, except 10 nm for L1410A) in paired cells. F, bar diagrams are shown for the amplitude (Idis, which is the disinihibitory component I3 expressed as a fraction of resting current block) and time course (τ) of the slowest component of the three-exponential fit to the time course of recovery of inactivation for mutants N390A (n = 4), L1410A (n = 7), V1414A (n = 3), I1706A (n = 3), F1710A (n = 4), and Y1717A (n = 6), whereas wild type (n = 6) and mutant I381A (n = 6) did not show disinhibition. The dotted line in C–E represents the level of resting block.

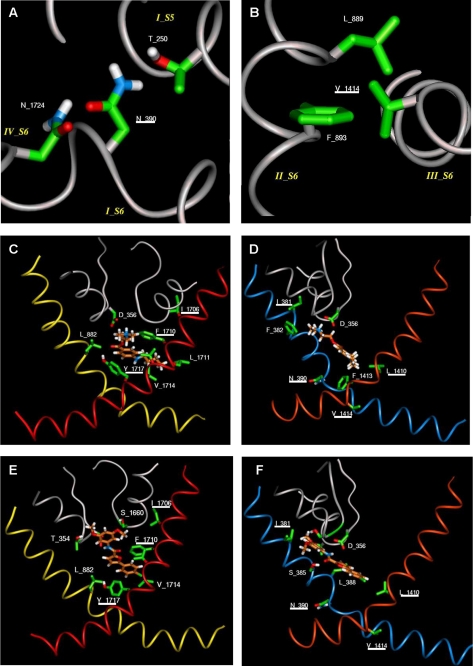

Molecular Modeling—A model was constructed for the S6 and P loop regions of the NaV1.8 channel, using the alignment shown in Fig. 9 (see “Experimental Procedures”) with the rat KV1.2 channel in the open state. The model suggests that, unlike the other S6 residues mutated in this study, Asn390 and Val1414 do not face into the pore but rather form interhelical interactions with adjacent helices. Thus Asn390 in domain I forms hydrogen bonds with Asn1724 in S6 of domain IV and Thr250 in S5 of domain I, whereas Val1414 in domain III makes hydrophobic contacts with Leu889 and Phe893 in S6 of domain II (Fig. 10, A and B). These residues are all located in the cytoplasmic side of the transmembrane bundle.

FIGURE 9.

Sequence alignments used in the model. The S5 helices, P-loops, and S6 helices are aligned with the rat KV1.2 channel (31). The DEKA motif in the filter and the glycines in S6 are shown shaded.

FIGURE 10.

Modeling of the pore region of NaV1.8. A, local environment around Asn390, with hydrogen bonds between this residue and Asn1724 on S6 of domain IV and Thr250 on S5 of domain I. B, local environment around Val1414, with hydrophobic interactions with Leu889 and Phe893 on S6 of domain II. These interactions occur at the cytoplasmic side of the bundle in the open state model. C, the figure shows docking of tetracaine to IIS6, IVS6, and P-loops, with π-π stacking Phe1710 (in IVS6) and Tyr1717 (in IVS6), whereas the latter residue also forms a hydrogen bond with the ester carbonyl group of tetracaine. Hydrophobic interactions are also observed between tetracaine and Leu882 (in IIS6) and Leu1711 (IVS6). D, docking is shown for tetracaine to IS6, IIIS6, and P-loops, with the protonated amino group of the compound forming a salt bridge with Asp356 (in the P-loop), whereas the amino-methyl groups have hydrophobic interactions with Ile381 (in IS6) and Phe382 (in IS6). The butyl group of tetracaine also forms hydrophobic interactions with Leu1410 (in IIIS6) and Phe1413 (in IIIS6). E, docking of A-803467 is shown to IIS6, IVS6, and P-loops, with P-loop residues Thr354 and Ser1660 hydrogen bonding to the two methoxy groups of the compound. There is π-π stacking between the ligand and Phe1710 (in IVS6) and additional hydrophobic interaction with Leu882 (in IIS6) and Val1714 (in IVS6). F, the figure shows docking of A-803467 to IS6, IIIS6, and P-loops, with primary interaction with Asp356 (in the P-loop) and Leu1410 (in IIIS6) in the proximity of the chlorophenyl ring of the compound. There is also a hydrogen bond between the amide carbonyl group of the compound and Ser385 (in IS6). Residues Asn390 (in IS6) and Val1414 (in IIIS6) do not interact with the ligand. The figures in C–F show P-loops for domains I and IV and S6 helices for all four domains. The α-carbon ribbons are color-coded as follows: gray, pore loops; blue, IS6; yellow, IIS6; orange, IIIS6; red, IVS6. The underlined residues were mutated.

Using the model, docking studies were performed with tetracaine and compound A-803467 (Fig. 10, C–F). The lack of any acidic residues in the S6 helices suggested that binding of the protonated nitrogen of tetracaine and the amide NH of A-803467 might occur with the aspartate, Asp356 in the P loop of domain I (i.e. the Asp of the DEKA motif). This allowed the ligands to adopt poses where all the observed mutation results could be explained. Residue Phe1710 forms π-π stacking with an aromatic ring in both ligands, whereas Leu1410 forms good hydrophobic interactions with both drugs, consistent with the experimental finding that its mutation altered the drug action. However, compound A-803467 extends further into the P loop of the channel where the two methoxy groups of the compound can form hydrogen bonds with Thr354 and Ser1660 in P loops. These hydrogen bonds effectively lock A-803467 in this position so that the substituted ring cannot form a favorable hydrophobic interaction with Ile381 in S6. The dimethyl amino group of tetracaine, however, is able to interact favorably with Ile381. The tyrosine residue, Tyr1717 in S6, can form a good hydrogen bond to the ester carbonyl of tetracaine, but it is relatively far from the biaryl rings of A-803467, so cannot interact favorably with it. The experimental results for affinities of the compounds found in our mutational study support the model.

DISCUSSION

Functional Properties of NaV1.8 S6 Mutants—Mutations in Asn390 and Val1414 gave positive shifts in steady-state activation, suggesting that the corresponding native residues stabilize open states relative to closed states. This seems to be consistent with our molecular model in the open state, because these two residues and those that interact with them are all located in the cytoplasmic side of the transmembrane bundle, and interactions are probably more likely to be found in the open state, so that these residues may indeed stabilize open states. At residues corresponding to these positions in rNaV1.2 and rNaV1.4, similar positive shifts were observed in previous work (30, 38, 39).

Other mutations in NaV1.8 gave negative shifts in activation (I381A and F1710A), indicating relative stabilization of corresponding native closed states. However, for residues corresponding to these, negative shifts were not observed for mutations in the rNaV1.2 channel (30, 40). Furthermore, in contrast to our results showing lack of shift for mutations L1410A and I1706A in NaV1.8, homologous rNaV1.2 mutations showed positive shifts (41). Thus, the S6 segment residues play an important role in voltage dependence of activation but this role in activation appears to be different for the NaV1.8 channel from other subtypes.

For the voltage dependence of steady-state inactivation in NaV1.8, all mutations studied here (except F1710A) caused strong negative shifts. One possibility might be that shifts in inactivation curves might simply be the result of shifts in the activation curves. However, because NaV1.8 activation showed both negative and positive shifts depending on the mutation studied, this suggests that inactivation gating is not simply linked to activation, as already noted for NaV1.4 (42). These curves represent mainly inactivation from closed states (41). Thus, for NaV1.8, closed-state inactivation is less favored for the native channel than for the mutants. We also showed that the time course of inactivation of NaV1.8 was faster for all the mutants considered here. Because this represents open-state inactivation (41), the data show that open-state inactivation is also less favorable for the native channel than for the mutants. The mutational data shows that all the S6 residues studied here are involved in inactivation processes in the native channel.

As for activation, the effects of mutations on inactivation appear to be subtype-specific. For closed-state inactivation, shifts for N390A, V1414A, and I381A in NaV1.8 were in the opposite direction to those for corresponding mutations in NaV1.2; there was no shift for F1710A in NaV1.8, whereas corresponding mutations in NaV1.2 and NaV1.5 gave positive shifts (30, 40, 41, 43). For open state inactivation (observed from the time course of decay of currents), all the mutations in NaV1.8 caused a faster time course, whereas the corresponding mutations in NaV1.2 did not affect it (nor did mutations in NaV1.4 corresponding to I1706A and Y1717A in NaV1.8). Also the mutation corresponding to F1710A in NaV1.8 was slower for NaV1.4 (30, 40–42). The underlying reason at the molecular level for these differences is not known, but may be related to the property of slower inactivation observed in native NaV1.8 than in other NaV subtypes.

For the IVS6 segment mutations I1706A, F1710A, and Y1717A, but not for the other mutations considered here, there was incomplete inactivation, even at very positive potentials. A similar phenomenon of incomplete inactivation has also been reported for NaV1.2 for the mutations homologous to F1710A and Y1717A in NaV1.8, and for NaV1.4 mutation homologous to N390A in NaV1.8 (40, 44). Thus, as for the other subtypes, for NaV1.8 these residues play an important role in inactivation. Mutation Y1717A gave the largest effect in NaV1.8; as this mutation is located at the intracellular mouth of the pore where the inactivation domain III–IV linker acts, it may be that this residue is somehow involved in the receptor site for fast inactivation (40).

Effects of S6 Segment Mutations on Drug Action on the NaV1.8 Channel—Tetracaine and A-803467 have been previously shown to preferentially bind to inactivated rather than resting wild type NaV1.8 channels (9, 36). Here we have analyzed the actions of tetracaine and compound A-803467 on the human channel using an appropriate mammalian expression system. Similar magnitude shifts in the steady-state inactivation curve were observed following the application of either tetracaine (10 μm) or compound A-803467 (150 nm) separately, or following the application of both drugs together (at half the above concentrations). This finding indicates that one drug precludes the binding of the other. The observed shifts were all of a similar magnitude to the value predicted by a model with a single binding site, rather than a model with separate binding sites for each compound. Thus, tetracaine and A-803467 appear to bind to overlapping, or partially overlapping, binding sites on the NaV1.8 channel.

To determine more precisely the site of action of tetracaine and A-803467 on the NaV1.8 channel, residues were chosen for mutation in the S6 regions guided by their role in drug binding for other NaV subtypes (21, 22). We have shown that residues Ile381, Leu1410, Phe1710, and Tyr1717 are involved for tetracaine affinity, but only residues Leu1410 and Phe1710 for A-803467. The roles of these residues in binding of the respective compounds was fully supported in our docking study using the molecular model for NaV1.8 (Fig. 10, C–F). In addition, the model implicates binding of other residues in the pore region of the channel. The S6 residues implicated in binding to NaV1.8 by molecular modeling and by our mutational studies are summarized in Fig. 1B.

The increased resting affinity observed with the L1410A mutant is difficult to explain in our molecular model; one possibility would be that the compounds are being trapped in the bound state, although it is difficult to understand how the alanine mutation would enhance trapping. As the mutation did not show unusual functional properties in the absence of drugs (see above), it is unlikely that the mutation causes severe distortion of the molecular structure.

In previous studies with a range of drugs and NaV subtypes, the residue corresponding to Phe1710 in NaV1.8 has generally been found to be most important in determining inactivated state affinity (36). We have indeed found this residue to be important in the present study for NaV1.8, both for binding of tetracaine and for A-803467. For tetracaine the F1710A mutation reduced the inactivated state affinity far more than the resting affinity, and so this residue has a key role in contributing to the preferential inactivated state block of tetracaine. A similar result for tetracaine was found for NaV1.3 channels (36). For compound A-803467, no previous mutagenesis work has been carried out, and as mentioned in the Introduction, it was speculated that this drug does not bind to the local anesthetic binding site (26). However, our results for mutation of the local anesthetic binding site Phe1710 indeed further suggests binding of this compound to at least part of the established local anesthetic binding site. Although this residue is indeed important for binding of compound A-803467, by contrast with tetracaine other residues not mutated here must also be important for binding. The reason for this is that mutation of this residue in NaV1.8 affected both resting and inactivated state affinities for A-803467 by similar proportional amounts, and because affinity of this compound for inactivated native channels is much greater than for resting native channels, other residues must also be involved. Our modeling leads us to suggest that other residues in S6 regions of all four domains and the P-loop may also be important for A-803467 binding (Fig. 10, C–F), and it would be interesting to investigate the role of these residues in future mutational studies.

Although the residues considered here have been shown to be involved for a range of NaV subtypes and compounds, tetracaine has so far only been examined for NaV1.3 where residues corresponding to Phe1710 (as above) and Tyr1717 are involved, although the interaction with the latter residue was suggested to be indirect (36). For NaV1.2 channels, the local anesthetic etidocaine also has important interactions with these residues (45). The key role for residue Phe1710 in drug binding has also been generally shown for NaV1.3, NaV1.4, and NaV1.5 (22). This residue is proposed to directly bind to local anesthetics by a cation-π interaction (46), although our model for NaV1.8 suggests a π-π stacking interaction. Overall it is surprising that compound A-803467 is selective for NaV1.8, whereas the sequence alignments with other human NaV subtypes (Fig. 1B) show that the residues that we have implicated in drug binding (whether by the mutational study or by modeling) are almost completely identical between NaV subtypes. Of the residues mutated here, only the Val1414 residue is different in other subtypes; the isoleucine present in other subtypes at this position may contribute to subtype differences, although it is remote to the ligand binding site. However, the other regions of the channel may indirectly involve drug binding; indeed slow inactivation processes and their conformational implications for the whole channel have been suggested to play a role in selectivity of compounds (24). Another possible explanation of the reported selectivity may lie in the presence of a double glycine motif in the S6 helix of domain III. The glycine at 1406 is a serine in other NaV channels. This double glycine greatly increases the flexibility in the helix and indeed a brief molecular dynamics simulation of 200 ps3 showed that Leu1410 moved closer to the chlorophenyl ring of A-803467, thus further stabilizing the interaction. A more extensive mutational study of other residues coupled with more extensive molecular dynamics simulations in other NaV channel models would be required in the future to establish the reason for the selectivity of A-803467 for the NaV1.8 channel.

For native NaV1.8 channels, in the continual presence of compound A-803467, depolarization and subsequent repolarization leads not only to inactivation and recovery but also to partial removal of resting block by the compound. The latter mechanism involves a component with an increase in current (disinhibition), an entirely distinct process from removal of inactivation during recovery. All the mutations considered here increased this disinhibitory current for A-803467. An extremely interesting example of this was for mutant L1410A, where resting block by the compound was almost complete. For this mutant, stimulation in the presence of the compound gave an appreciable current corresponding to marked removal of the resting block. This phenomenon was observed whether stimulation was applied repetitively (Fig. 6B), or after long (600 ms, Fig. 6D) or short (50 ms, Fig. 7E) depolarizations. For the other mutations considered here, whereas resting block was generally not substantially affected, all mutations showed greater disinhibition than for the wild type channel. Thus all the residues mutated here appear to be involved in this disinhibitory effect of A-803467.

Tetracaine did not show the disinhibitory effect for native NaV1.8 channels. However, mutations caused the appearance of disinhibitory components after stimulation in the presence of tetracaine. As for compound A-803467, tetracaine almost completely blocked resting channels with high affinity for mutant L1410A, and yet stimulation in the presence of tetracaine again showed a disinhibitory component, whether for repetitive stimulation or for long or short pulses (Figs. 6 and 8). Of the remaining mutants considered here, clear disinhibitory currents were seen for F1710A, although smaller effects were seen for most of the other mutants. Taken together, the data suggest that for tetracaine, residues Leu1410 and Phe1710 contribute to the mechanism underlying the main disinhibitory component on the NaV1.8 channel.

The phenomenon of disinhibition is not easy to understand by the molecular model. One may speculate that disinhibition may be the result of weakened ligand binding to the pore region (and the DEKA filter) caused by channel opening and the compound moving away from the pore loop region, so allowing increased channel currents. With tetracaine, the salt bridge with Asp356 of the DEKA filter is stronger than the hydrogen bonds formed with A-803467, and so less disinhibition would occur for tetracaine. The hydrogen bonds from the P-loop residues Thr354 and Ser1660 to A-803467 hold the ligand to the side of the P loop and would then perhaps allow partial flow of ions through the channel, perhaps allowing disinhibition for the native channel in the case of A-803467, although not for tetracaine.

Although it seems reasonable to interpret the disinhibitory component as due to removal of resting block by stimulation in the presence of the compounds, another possible mechanism may be the induction of a new single channel state with a higher conductance. Thus it would be interesting to test this in the future using single channel recordings. Either way, during recovery from disinhibition there is reinstatement of the resting equilibrium state in the presence of the drug. Although the detailed mechanism for this process is not understood, because the time course of removal of the disinhibitory component is very slow (order of seconds), that would imply that the process does not involve simply unbinding and rebinding of the drug (which would be much quicker). One may perhaps hypothesize that depolarization in the presence of the drug induces a new type of state with slow recovery back to equilibrium.

In summary, our mutational study has indicated that various residues in the S6 region play important roles in the activation and inactivation properties of the NaV1.8 channel. We have identified residues in S6 involved in the resting and inactivating state block by tetracaine and A-803467. We also identified residues involved in the phenomenon of removal of resting block (disinhibition) by stimulation in the presence of these compounds. The data suggest differing but partially overlapping areas of binding for tetracaine and compound A-803467.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew Powell and Tim Dale for continuing expert technical assistance and advice. We are grateful to Dr. Lin-Hua Jiang for help with initial experiments in his laboratory and for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and GlaxoSmithKline.

Footnotes

Browne, L. E., Clare, J. J., and Wray, D. (2009) Neuropharmacology 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.01.018.

F. E. Blaney, unpublished data.

References

- 1.Catterall, W. A., Goldin, A. L., and Waxman, S. G. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57 397-409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hille, B. (2001) Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes, Sinauer, Sunderland, MA

- 3.Catterall, W. A. (2000) Neuron 26 13-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang, N., George, A. L., Jr., and Horn, R. (1996) Neuron 16 113-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldin, A. L., Barchi, R. L., Caldwell, J. H., Hofmann, F., Howe, J. R., Hunter, J. C., Kallen, R. G., Mandel, G., Meisler, M. H., Netter, Y. B., Noda, M., Tamkun, M. M., Waxman, S. G., Wood, J. N., and Catterall, W. A. (2000) Neuron 28 365-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akopian, A. N., Sivilotti, L., and Wood, J. N. (1996) Nature 379 257-262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rabert, D. K., Koch, B. D., Ilnicka, M., Obernolte, R. A., Naylor, S. L., Herman, R. C., Eglen, R. M., Hunter, J. C., and Sangameswaran, L. (1998) Pain 78 107-114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sangameswaran, L., Delgado, S. G., Fish, L. M., Koch, B. D., Jakeman, L. B., Stewart, G. R., Sze, P., Hunter, J. C., Eglen, R. M., and Herman, R. C. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 5953-5956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarvis, M. F., Honore, P., Shieh, C. C., Chapman, M., Joshi, S., Zhang, X. F., Kort, M., Carroll, W., Marron, B., Atkinson, R., Thomas, J., Liu, D., Krambis, M., Liu, Y., McGaraughty, S., Chu, K., Roeloffs, R., Zhong, C., Mikusa, J. P., Hernandez, G., Gauvin, D., Wade, C., Zhu, C., Pai, M., Scanio, M., Shi, L., Drizin, I., Gregg, R., Matulenko, M., Hakeem, A., Gross, M., Johnson, M., Marsh, K., Wagoner, P. K., Sullivan, J. P., Faltynek, C. R., and Krafte, D. S. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 8520-8525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abrahamsen, B., Zhao, J., Asante, C. O., Cendan, C. M., Marsh, S., Martinez-Barbera, J. P., Nassar, M. A., Dickenson, A. H., and Wood, J. N. (2008) Science 321 702-705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akopian, A. N., Souslova, V., England, S., Okuse, K., Ogata, N., Ure, J., Smith, A., Kerr, B. J., McMahon, S. B., Boyce, S., Hill, R., Stanfa, L. C., Dickenson, A. H., and Wood, J. N. (1999) Nat. Neurosci. 2 541-548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr, B. J., Souslova, V., McMahon, S. B., and Wood, J. N. (2001) Neuroreport 12 3077-3080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laird, J. M., Souslova, V., Wood, J. N., and Cervero, F. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22 8352-8356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nassar, M. A., Levato, A., Stirling, L. C., and Wood, J. N. (2005) Mol. Pain 1 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshi, S. K., Mikusa, J. P., Hernandez, G., Baker, S., Shieh, C. C., Neelands, T., Zhang, X. F., Niforatos, W., Kage, K., Han, P., Krafte, D., Faltynek, C., Sullivan, J. P., Jarvis, M. F., and Honore, P. (2006) Pain 123 75-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai, J., Gold, M. S., Kim, C. S., Bian, D., Ossipov, M. H., Hunter, J. C., and Porreca, F. (2002) Pain 95 143-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Porreca, F., Lai, J., Bian, D., Wegert, S., Ossipov, M. H., Eglen, R. M., Kassotakis, L., Novakovic, S., Rabert, D. K., Sangameswaran, L., and Hunter, J. C. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 7640-7644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dong, X. W., Goregoaker, S., Engler, H., Zhou, X., Mark, L., Crona, J., Terry, R., Hunter, J., and Priestley, T. (2007) Neuroscience 146 812-821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox, J. J., Reimann, F., Nicholas, A. K., Thornton, G., Roberts, E., Springell, K., Karbani, G., Jafri, H., Mannan, J., Raashid, Y., Al-Gazali, L., Hamamy, H., Valente, E. M., Gorman, S., Williams, R., McHale, D. P., Wood, J. N., Gribble, F. M., and Woods, C. G. (2006) Nature 444 894-898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hille, B. (1977) J. Gen. Physiol. 69 497-515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Catterall, W. A. (2002) Novartis Found. Symp. 241 206-218; Discussion 218–232 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nau, C., and Wang, G. K. (2004) J. Membr. Biol. 201 1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akiba, I., Seki, T., Mori, M., Iizuka, M., Nishimura, S., Sasaki, S., Imoto, K., and Barsoumian, E. L. (2003) Receptors Channels 9 291-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leffler, A., Reiprich, A., Mohapatra, D. P., and Nau, C. (2007) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 320 354-364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy, M. L., and Narahashi, T. (1992) J. Neurosci. 12 2104-2111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cummins, T. R., and Rush, A. M. (2007) Exp. Rev. Neurother. 7 1597-1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Condreay, J. P., Witherspoon, S. M., Clay, W. C., and Kost, T. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 127-132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo, C. C., and Bean, B. P. (1994) Mol. Pharmacol. 46 716-725 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu, G., Yarov-Yarovoy, V., Nobbs, M., Clare, J. J., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (2003) Neuropharmacology 44 413-422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yarov-Yarovoy, V., McPhee, J. C., Idsvoog, D., Pate, C., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 35393-35401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long, S. B., Campbell, E. B., and Mackinnon, R. (2005) Science 309 897-903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kyte, J., and Doolittle, R. F. (1982) J. Mol. Biol. 157 105-132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blaney, F. E., and Tennant, M. (1996) in Membrane Protein Models (Findlay, J. B. C., ed) pp. 161-176, Bios Scientific Publishers Ltd., Oxford

- 34.Brooks, B. R., Bruccoleri, R. E., Olafson, B. D., States, D. J., Swaminathan, S., and Karplus, M. (1983) J. Comput. Chem. 4 187-217 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunbrack, R. L., Jr., and Karplus, M. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 230 543-574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li, H. L., Galue, A., Meadows, L., and Ragsdale, D. S. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 55 134-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo, C. C. (1998) Mol. Pharmacol. 54 712-721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nau, C., Wang, S. Y., Strichartz, G. R., and Wang, G. K. (1999) Mol. Pharmacol. 56 404-413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang, S. Y., and Wang, G. K. (1997) Biophys. J. 72 1633-1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McPhee, J. C., Ragsdale, D. S., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 12025-12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yarov-Yarovoy, V., Brown, J., Sharp, E. M., Clare, J. J., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 20-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kondratiev, A., and Tomaselli, G. F. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 64 741-752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carboni, M., Zhang, Z. S., Neplioueva, V., Starmer, C. F., and Grant, A. O. (2005) J. Membr. Biol. 207 107-117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nau, C., Wang, S. Y., and Wang, G. K. (2003) Mol. Pharmacol. 63 1398-1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ragsdale, D. S., McPhee, J. C., Scheuer, T., and Catterall, W. A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 9270-9275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahern, C. A., Eastwood, A. L., Dougherty, D. A., and Horn, R. (2008) Circ. Res. 102 86-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]