Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the role of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) in the pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR).

Methods

Expression of CTGF was evaluated immunohistochemically in human PVR membranes, while the accumulation of CTGF in the vitreous was evaluated by ELISA. The effects of CTGF on type I collagen mRNA and protein expression in RPE were assayed by real time PCR and ELISA, while migration was assayed with a Boyden chamber assay. Experimental PVR was induced in rabbits using vitreous injection of RPE cells plus rhCTGF; injection of RPE cells plus platelet derived growth factor with or without rhCTGF; or by injection of RPE cells infected with an adenoviral vector expressing CTGF.

Results

CTGF was highly expressed in human PVR membranes and partially co-localized with cytokeratin-positive RPE cells. Treatment of RPE with rhCTGF stimulated migration with a peak response at 50ng/ml (P<0.05), and increased expression of type I collagen (P<0.05). There was a prominent accumulation of N-terminal half of CTGF in the vitreous of patients with PVR. Intravitreal injection of rhCTGF alone did not produce PVR, while such injections into rabbits with mild, nonfibrotic PVR promoted the development of dense, fibrotic epiretinal membranes. Similarly, intravitreal injection of RPE cells infected with adenoviral vectors overexpressing CTGF induced fibrotic PVR. Experimental PVR was associated with increased CTGF mRNA in PVR membranes and accumulation of CTGF half fragments in vitreous.

Conclusion

Our results identify CTGF as a major mediator of retinal fibrosis and potentially an effective therapeutic target for PVR.

Fibrosis plays an important role in the pathogenesis of several common blinding disorders, including proliferative diabetic retinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, age-related macular degeneration, and PVR;1–4 however, much needs to be learned about the basic pathophysiology of fibrosis in the intraocular environment.1 PVR may be viewed as a prototypical example of a protracted intraocular wound healing response that occurs when traction-generating cellular membranes develop in the vitreous and on the inner or outer surfaces of the retina following rhegmatogenous retinal detachment or major ocular trauma.5–7 RPE cells play a critical role in this epiretinal membrane formation8,9 These cells proliferate and migrate from the RPE monolayer to form sheets of dedifferentiated cells within a provisional extracellular matrix (ECM) containing fibronectin and thrombospondin.9–11 The protracted wound healing response causes the cellular membrane to become progressively more paucicellular and fibrotic.11 Experimental models of PVR have been developed to evaluate intraocular proliferation;12–16 however, these models typically exhibit cellular fibrinous strands without prominent fibrotic responses. Studies evaluating the role of those factors that elicit this fibrotic response are of particular interest.

Normal ocular wound healing involves a tightly coordinated series of events: recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells, release of cytokines and growth factors, activation, proliferation and migration of ocular cells, secretion of extracellular matrix, tissue remodeling, and repair.1, 17 CTGF is an important stimulant of fibrosis,18 but its role in intraocular wound healing or PVR has not been studied in detail.

CTGF is a secreted, cysteine-rich, heparin-binding polypeptide growth factor,19 20 that is rapidly upregulated after stimulation with serum or transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β̣). Various CTGF fragments have been shown to accumulate in tissue culture or body fluids while retaining their biologic activity.20–22 CTGF functions as a downstream mediator of TGF- β action on fibroblasts; it stimulates cell proliferation and cell matrix deposition (collagen 1 and fibronectin),18,20,23 and it may induce apoptosis.24,25 In addition to its action as a growth factor, CTGF has been implicated as an adhesive substrate in fibroblasts, mediated through α6β1 integrin.26 Importantly, CTGF is coordinately expressed with TGF-β̣ and it demonstrates increased expression in numerous fibrotic disorders, including systemic sclerosis,27,28 pulmonary, renal, and myocardial fibrosis,29–32 and atherosclerosis.33 In the present study, we examine the process by which CTGF mediates the transformation of activated RPE into a fibrotic epiretinal membrane. Our results identify CTGF as a major mediator of retinal fibrosis and potentially an effective therapeutic target.

Materials and methods

The institutional review board (IRB) of the University of Southern California approved our use of cultured human RPE cells, human PVR specimens and human vitreous samples. All procedures conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

RPE Cultures

Human RPE cells were isolated from fetal human eyes >22 wks gestation (Advanced Bioscience Resources, Inc., Alameda CA). Cells were cultured in DMEM (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA). The culture method used, a standard practice in our lab for more than 10 years, regularly yields >95% cytokeratin-positive RPE cells.34 Cells used were from passages 2 to 4.

Rabbit RPE cell cultures were obtained from pigmented adult rabbits. Briefly, the globes were opened and the cornea, lens, and vitreous humor were removed by a circumferential cut just posterior to the ora serrata. The neural retina was carefully washed out with the RPE medium. The eye cups were washed with Hanks’ balanced salt solution and digested with 0.012% (wt/vol) trypsin (Sigma) in 0.005% (wt/vol) EDTA (Sigma) for 1 h at 37°C. The trypsinization was stopped by adding excess DMEM. The dissociated RPE cells were carefully washed out without disturbing the underlying choroid. The RPE cells were first cultured with the medium in 12-well plates to near confluence and then passaged to 25 cm2 flasks.

Growth Factor and Vectors

rhCTGF, rabbit anti-CTGF polyclonal antibody, domain-specific anti-CTGF monoclonal antibodies for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and a recombinant adenovirus vector expressing human CTGF, were all gifts from FibroGen Inc. (South San Francisco, CA).

Human Vitreous Samples

Vitreous samples were obtained at the time of pars plana vitrectomy by participating ophthalmologists from patients with PVR + retinal detachment (n=6), patients with uncomplicated retinal detachment (n=5), and control patients without proliferative retinal disease (macular hole, macular pucker, or epiretinal membrane; n=12). Undiluted samples were placed on ice. Samples were promptly centrifuged at 36,000 rpm at 4°C, and the supernatants were frozen at −80°C until assayed.

Immunohistochemical Staining of PVR Membranes

Epiretinal membranes were surgically excised from 10 patients with PVR (Male: 3, Female: 7; Age range: 48–78). Tissues were snap frozen and 6 µ sections were cut with the cryostat. Thawed tissue sections were air dried, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (10 min), washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), and blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 15 min. Anti-CTGF polyclonal antibody (1: 400, Fibrogen) was applied on the tissue sections and then with secondary biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody (1:200, Vector, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min and sites of immunostaining revealed with the ABC staining methods (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). For double staining, sections were incubated with anti-CTGF antibody for 60 min and with rhodamine secondary antibody (1:200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 min; mouse anti-human pan-cytokeratin (Sigma) was added to cover the tissue, and slides were incubated for 1 h at room temperature to label the cytokeratin-positive cells. Secondary fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Vector Laboratories) was then applied for another 30 min. After each step of the incubation, sections were washed with PBS three times for 5 minutes each. Finally, the samples were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM510, Zeiss, Thornwood, NY).

Type 1 collagen expression in rabbit PVR membranes was analyzed by the application of goat anti- type 1 collagen antibody (Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA). After incubation for 60 min with primary antibodies, biotinylated secondary anti-goat antibody (1:200, Vector) and streptavidin peroxidase (Vector Laboratories) were then applied to the sections sequentially. Between each step, the sections were washed three times with PBS. Immunoreactivity was visualized using the peroxidase substrate amino ethyl carbazole (AEC kit, Zymed Laboratories, Inc. South San Francisco, CA). Slides were rinsed with tap water, counterstained with hematoxylin, and mounted with glycerin-gelatin medium.

For each of the immunostain procedures, negative controls included omission of primary antibody and use of an irrelevant polyclonal or isotype-matched monoclonal primary antibody; in all cases negative controls showed only faint, insignificant staining.

Migration Assay

Migration was measured using a modified Boyden chamber assay as previously described.35 Briefly, 5 × 104 human fetal RPE cells (passage 2–4) were seeded in the upper part of a Boyden chamber in 24-well plates, with inserts coated with fibronectin (2 µg/cm2). The lower chamber was filled with 0.4% FBS-DMEM containing 1–100 ng/ml rhCTGF. After 5 h incubation, the inserts were washed three times with PBS, fixed with cold methanol (4°C) for 10 min, and counterstained with hematoxylin for 20 min. The number of migrated cells was counted by phase-contrast microscopy (x320). Four randomly chosen fields were counted per insert. The experiment was repeated three times.

Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction for analysis of Collagen 1 gene expression

The RPE cells were treated with rhCTGF 30 ng/ml in the presence of 1% FBS for 24 to 96 h. Total RNA was extracted from RPE cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The primer sequence for type I collagen was CCTGCGTGTACCCCACTCA (forward) and CGCCATACTCGAACTGGAATC (reverse). Each polymerase chain reaction (PCR) contained equivalent amounts of total RNA. Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate with a kit used according to the manufacturer's recommendation (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The quantity of mRNA was calculated by normalizing the threshold cycle value of type I collagen to the threshold cycle value of the housekeeping gene β-actin of the same RNA sample, according to the published formula.36 Experiments were repeated three times.

Reverse Transcriptase PCR for analysis of CTGF gene expression

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was utilized to measure expression of CTGF in retinal tissues microdissected from control rabbits, retinal tissues + adherent membranes from rabbits with experimental PVR induced by intravitreal injection of RPE cells + PDGF + rhCTGF (see Rabbit PVR Models below), and from the human RPE cell line ARPE-19. Total RNA was isolated as described above. A set of oligo deoxynucleotide primers corresponding to sequences in the first and fifth exon of both human and rabbit CTGF genes was designed and synthesized for the amplification of full length CTGF cDNA. After cDNA synthesis, CTGF specific primers (forward: GTC GCC TTC GTG GTC CTC CT, and reverse: GCC GTC AGG GCA CTT GAA CT) were used for PCR amplification using a PCR kit (Qiagen). Since the complete rabbit CTGF sequence was not available, human CTGF primers were used to amplify rabbit CTGF cDNA. The rabbit CTGF amplicons were of the same size as those from human cDNA and DNA sequencing confirmed that the amplified rabbit CTGF cDNA matched the online partial rabbit CTGF sequence (accession number: AB217855). After 35 cycles of PCR, products were resolved on 1.2% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The gel was photographed under ultraviolet illumination and the appropriate product size was determined using a 100 bp DNA ladder (Gibco BRL) as a molecular weight marker. CTGF expression levels were normalized using beta-actin cDNA as an internal loading control.

Rabbit PVR Models

Forty one adult pigmented rabbits, 2.5 to 3.5 kg each, were used. All experiments were performed in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. All procedures were approved by Keck School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

A. RPE Injection with Platelet-Derived Growth Factor and rhCTGF

Subconfluent rabbit RPE cells (passage 2–3) were used for the injection. After trypsinization and two PBS washes, the cells were resuspended in PBS and kept on ice. Before the RPE cell injection, 0.2 ml of vitreous was removed from each rabbit eye, using a 25-gauge needle. For each RPE cell injection, a 27-gauge needle was attached to a tuberculin syringe. The syringe was loaded with 100 ul RPE cells (15 × 104) and 50 ng platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF-BB, R&D Systems, Inc.). The needle was inserted through the sclera under indirect ophthalmoscopic control, 3 mm posterior to the limbus. The RPE/PDGF-BB was then deposited just over the optic disc. The second group of rabbits received the same RPE cells +PDGF injection with an additional injection of 200 ng rhCTGF one week after the first surgery. The same technique was used, but the injection was given at a different entrance site. On day 14, transpupillary optical coherence tomography (Humphrey Instruments, San Leandro, CA) was performed in randomly selected rabbits from each group to confirm the clinical observations. Classification of PVR was based on clinical findings according Fastenberg. 37 Stage 0: Normal retina; Stage 1: Intravitreal membrane; Stage 2: Focal traction, localized vascular changes, hyperemia, engorgement dilation; blood vessel elevation; Stage 3: Localized detachment of medullary ray; Stage 4: Extensive retinal detachment; total medullary ray detachment; peripapillary retinal detachment; Stage 5: Total retinal detachment, retinal folds and holes.

B. Recombinant Adenovirus CTGF -infected RPE Cell Injection

Rabbit RPE cells were isolated and washed three times with serum-free DMEM. After the cells reached confluence, 1 ml DMEM containing 1% FBS and 1 × 107 E1/E3 region –deleted recombinant adenoviruses encoding CTGF (Ad CMV, CTGF), or green fluorescence protein (Ad CMV, GFP), (the kind gift of FibroGen Inc), was added to a monolayer of cultured RPE cells. After incubation for 60 min at 37°C, the medium was replaced with fresh MEM (containing 2% FBS) and incubated for an additional 48 h. Western blot revealed a weak CTGF immunoreactive band in Ad CMV, GFP supernatants; while Ad CMV, CTGF supernatants contained a prominent CTGF immunoreactive band (>10 fold increase on densitometry) (results not shown). The cells were collected using the conventional method of trypsin digestion. Cells were washed twice with PBS and then resuspended (1 × 107/ml) in PBS.

To establish the rabbit PVR model using CTGF adenovirus-infected RPE cell injection, the pigmented rabbits were divided into three groups: RPE cells only, Ad CMV, CTGF, and Ad CMV, GFP. Using the injection technique described in PVR model A, we injected the eyes of the first group of rabbits with 0.1 ml PBS with 105 normal rabbit RPE cells, the second group with 105 rabbit RPE cells infected with Ad CMV, CTGF, and the third group with 105 rabbit RPE cells infected with Ad CMV, GFP.

For all rabbits in PVR models A and B, fundus photographs were taken 1 wk and 2 wk after surgery. Eyes were enucleated at 2 wk for histologic analysis.

Western Blot Assay

Vitreous samples were obtained from rabbits with PVR at the time of sacrifice. The vitreous samples were resolved on Tris hydrochloride 10% polyacrylamide gels (Ready Gel; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) at 120 V, with 10 µg of protein added to each lane. The proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride blotting membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membranes were probed, first with polyclonal anti-CTGF antibody (FibroGen, Inc.), and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature. Images were developed with chemiluminescence detection solution (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

ELISA Methods

A. CTGF ELISA

Because CTGF can undergo proteolysis and some bioactive fragments have been reported21, assessing both CTGF content and form is important for understanding a potential role of CTGF in PVR. CTGF sandwich ELISA’s (FibroGen, Inc.) were performed to determine content of CTGF and CTGF fragments in vitreous humor. Pairs of CTGF-specific monoclonal antibodies were selected for capture and detection of full-length CTGF (W ELISA), full length CTGF + CTGF NH2-terminal half fragments (N+W ELISA), and full length CTGF + CTGF COOH-terminal half fragments (C+W ELISA). Microtiter plates were coated overnight at 4°C with capture antibody (10 µg/ml) in 100 µl of coating buffer (0.05 mol/l sodium bicarbonate, pH 9.6). The plates were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature and washed with PBS/0.05% Tween. Vitreous samples were diluted 1:15 with 0.05M sodium carbonate, and a 50 µl sample was added to each well, together with 50 µl of biotinylated monoclonal anti-human CTGF detection antibody diluted in assay buffer (0.05 mol/l Tris [pH 7.8], 0.1% BSA, 4 mmol/l MgCl2, 0.2 mol/l ZnCl2, 0.1% sodium azide, 50 mg/l sodium heparin, and 0.1% Triton X-100). The plates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, washed with the Tris assay buffer, and incubated with 100 µl of streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at room temperature. The ELISA was developed with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (1.5 mg/ml; Sigma) in diethanolamine buffer (1 mol/l diethanolamine, 0.5 mmol/l MgCl2, 0.02% sodium azide) and read at an optical density of 405 nm. Purified rhCTGF was used as the standard. Sensitivities of these assays were approximately 1.0 ng/mL. We did not find evidence for substantial presence of CTGF COOH-terminal half fragments and therefore only report results for whole CTGF and CTGF NH2-terminal half fragments. Because the ELISA’s do not have identical efficiencies, CTGF values are expressed as whole CTGF and whole CTGF + CTGF NH2-terminal half fragments.

Determination of rabbit vitreous CTGF used a separate N+W ELISA that is capable of detecting both rabbit and human CTGF’s. Affinity purified goat anti-CTGF NH2-terminal half fragment was used as capture antibody and detection was with a monoclonal antibody that also reacts with CTGF NH2-terminal half fragment. Interference of the capture and detecting antibodies was tested and found to be negligible. NH2-terminal half CTGF fragments were generated by proteolytic cleavage of rhCTGF and purified by affinity chromatography. This material was used to affinity purify the goat polyclonal antibody. The standard used in this ELISA was rhCTGF. For these determinations, total vitreous CTGF content is reported (N+W CTGF) in ng/mL.

Detailed information about the capture and detection antibodies used in each of the ELISA assays is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of anti-CTGF antibodies used in ELISA Assays. The epitope location, antibody type and antibody species of each of the capture and detection antibodies utilized in the 4 ELISA assays are listed. W: whole CTGF; N: N-terminal CTGF; C: C-terminal CTGF; mAb: monoclonal antibody.

| ELISA | ELISA detects | Capture Antibodies | Detection Antibodies | Standard Used | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epitope Location | Antibody Type | Antibody Species | Epitope Location | Antibody Type | Antibody Species | Antibody Tag | |||

| Human W CTGF | Human full length CTGF | Domain 3 | mAb | human | Domain 1* | mAb | human | AP | rhCTGF |

| Human N+W CTGF | Human full length CTGF and Human N-half CTGF | Domain 2 | mAb | human | Domain 1* | mAb | human | AP | rhCTGF |

| Human C+W CTGF | Human full length CTGF and Human C-half CTGF | Domain 3 | mAb | human | Domain 3** | mAb | human | AP | rhCTGF |

| Cross Species N+W CTGF | Human and Rabbit full length CTGFs and Human and Rabbit N-half CTGFs | CTGF N-half | affinity purified polyclonal | goat | CTGF Domain 2 | mAb | human | AP | rhCTGF |

antibody specific for human CTGF;

Different mAb than that used for capture in the human C+W ELISA (The capture and detection mAbs used in this C+W ELISA recognize separate, non-interfering epitopes in Domain 3).

B. Type I Collagen ELISA Assay

Human fetal RPE cell cultures (passages 2–4) were grown to subconfluence in normal DMEM medium and incubated in serum-free medium for 24 h. Cells were treated with TGF-β2 (R&D Systems) or with full-length rhCTGF in 0.4% FBS for the indicated time points. To determine collagen content, a Human Type I Collagen Detection Kit (Chondrex, Redmond, WA) was used. Collagen in the tested samples was first solubilized with pepsin under acidic conditions and then further digested with pancreatic elastase at neutral pH to convert polymeric collagen to monomeric collagen. Supernatants were collected after brief centrifugation and tested directly in the ELISA kit. The experiment was repeated three times.

Statistics

The data was analyzed using the Student’s t-test, and P<0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

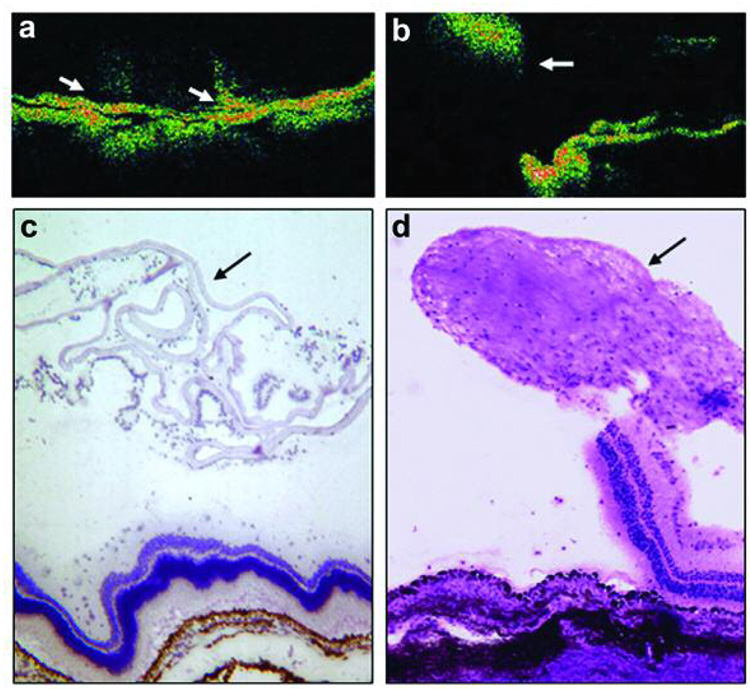

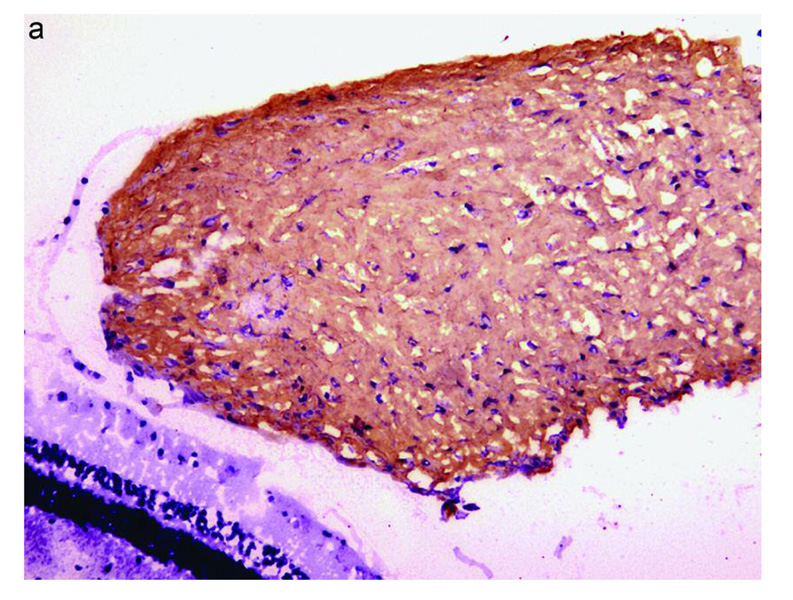

Expression of CTGF in Human PVR Membranes

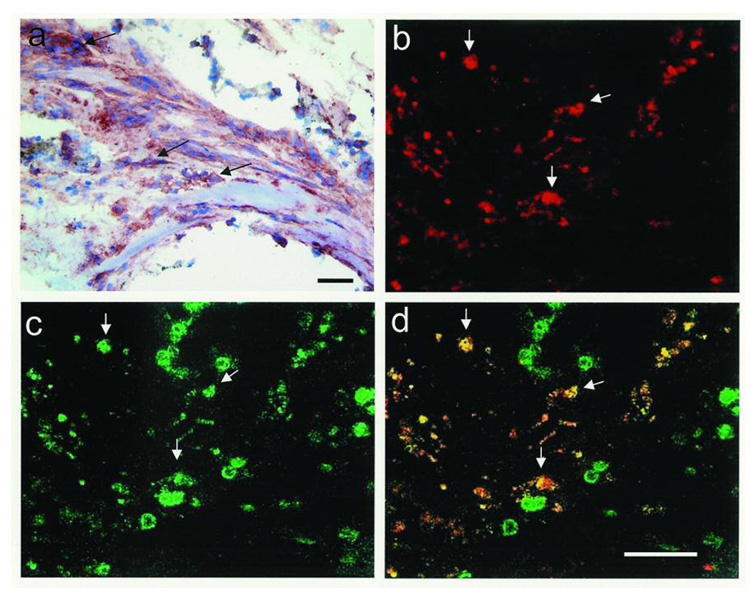

Each of the 10 human PVR membranes we examined showed extensive immunoreactivity for CTGF. CTGF staining was found in fibrotic regions of membranes; but was most predominantly localized in the stromal cells of cellular regions (Figure 1). Many of the CTGF-positive cells were also cytokeratin–positive, indicating that the cells were derived from RPE cells (Figure 1). A smaller fraction of CTGF positive cells showed co-localization with glial fibrillary acidic protein indicating derivation from retinal glial cells (results not shown).

Figure 1.

Photomicrograph of surgically excised human proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) membranes. In a), immunohistochemical stain for CTGF (red, arrows) reveals positive staining in stromal cells of PVR membrane (hematoxylin counterstain). In b–d), confocal double-stained immunofluorescent images of human PVR membrane shows stromal cells positive for CTGF (b, red, arrows) and cytokeratin (c, green, arrows). Overlay of b) and c) reveals that many of the stromal cells are positive for both CTGF and cytokeratin (d, yellow, arrows). Bar = 50 µm

CTGF Levels in Human Vitreous

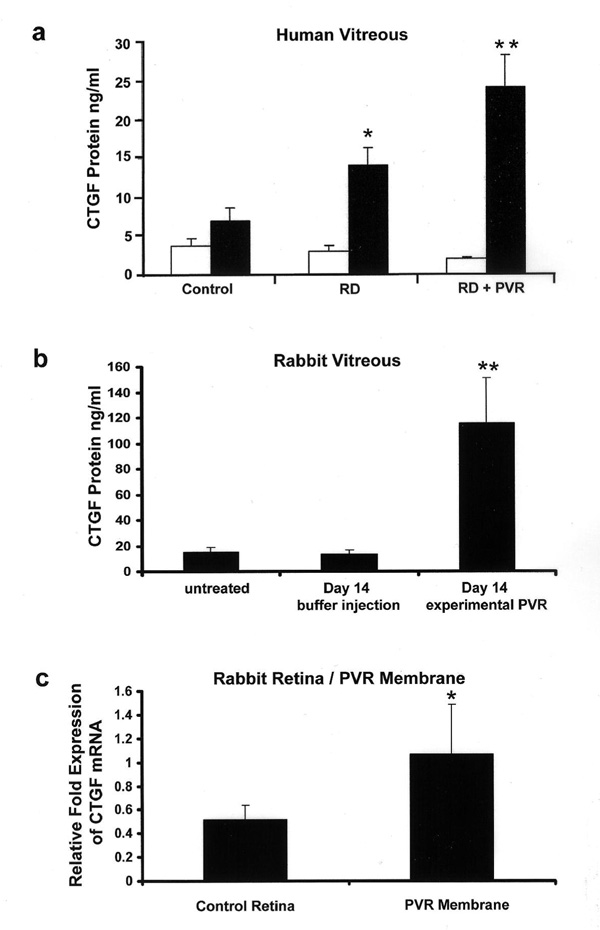

Vitreous samples were obtained from the eyes of patients with retinal detachment (RD) complicated by PVR (RD + PVR) and patients with RD but no PVR, as well as from control eyes without proliferative retinal disease (macular hole, macular pucker and epiretinal membrane). Levels of whole CTGF did not show an increase in the vitreous of patients with PVR or in the vitreous samples of patients with RD alone (Figure 2 A), however there was a prominent increase in the whole CTGF + CTGF NH2-terminal half fragments in the vitreous of patients with PVR compared to the other samples (P<0.01). RD without PVR was associated with moderate increase in whole CTGF + CTGF NH2-terminal half fragment level compared with control (P<0.05). Since the efficiencies in detecting CTGF differs in the 2 ELISA assays, the level of N-terminal half fragment CTGF can not be determined by subtracting whole CTGF from whole CTGF + CTGF NH2-terminal half fragments; however, it can be implied that the increase in whole CTGF + CTGF NH2-terminal half fragments is a result of an increase in the N-terminal half fragment. Assay for C-terminal CTGF was near or below the limits of detection in all samples, therefore [whole + N-terminal half fragment CTGF] is the best representation of total CTGF in the samples.

Figure 2.

CTGF Expression in Human and Experimental PVR. (a) Accumulation of CTGF fragments in the vitreous of human patients with retinal detachment (RD; n=5), RD complicated by PVR (n=6), or control patients with macular hole or epiretinal membrane (n=12). The level (ng/ml) of CTGF was determined by ELISA of vitreous samples. White (open bar) represents whole CTGF, while black (filled bar) represents total (whole + NH2-terminal half fragment) CTGF. C-terminal half fragment of CTGF was below limits of detection. (*, P<0.05 compared to control samples; **, P<0.01 compared to control samples). (b) Accumulation of total (whole + NH2-terminal) CTGF in rabbit vitreous in experimental PVR as assayed by ELISA. Vitreous samples were obtained from rabbits prior to injection at day 0 (untreated; n=5), from rabbits at d14 after injection of buffer only (n=12), and from rabbits with experimental PVR at d14 injected with PDGF and rhCTGF (n=5). (**, P<0.01 compared to buffer treated controls). (c). Relative fold expression of CTGF mRNA as evaluated by semi-quantitative RT-PCR in normal rabbit retina (n=4) and PVR membranes + retina of rabbits with experimental PVR at d14 injected with PDGF and rhCTGF (n=5). (*, P<0.05 compared to control retina).

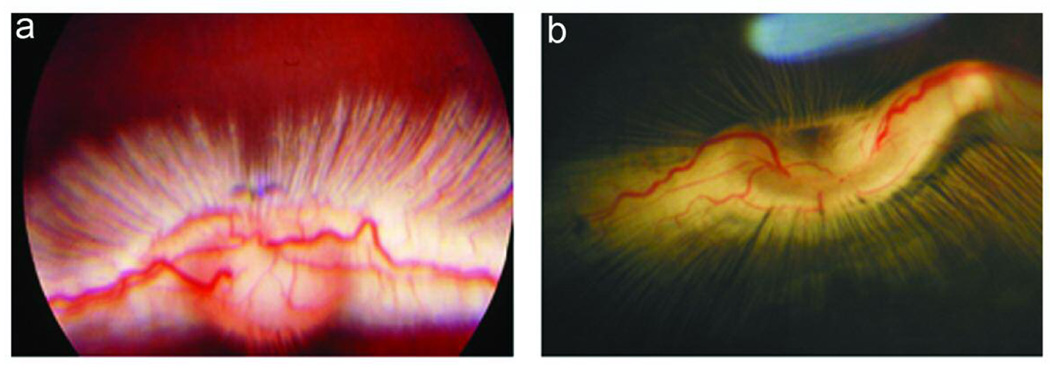

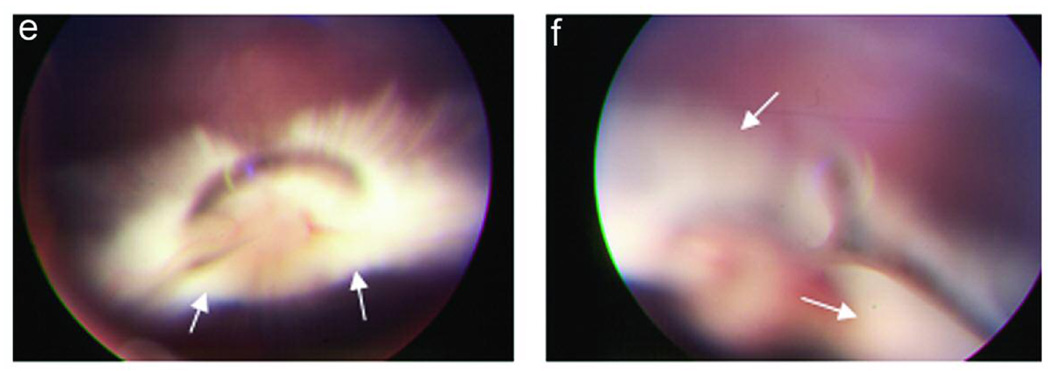

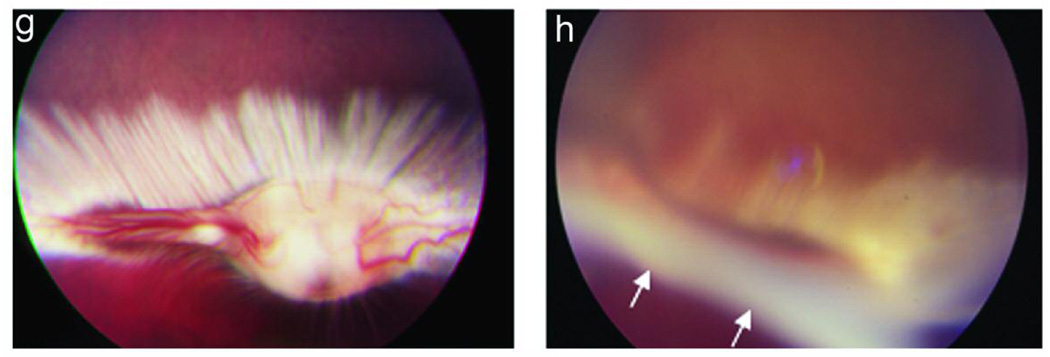

CTGF-Induced Fibrosis in Experimental Rabbit PVR

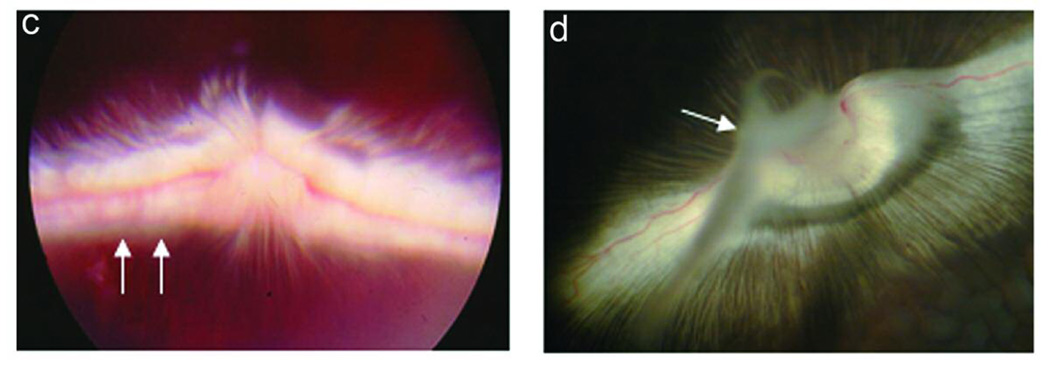

The development of PVR in 8 experimental conditions is summarized in Table 2. Intravitreous injection of rhCTGF (200ng) alone, PDGF (50ng) alone, or RPE cells alone into the rabbit eye did not induce detectable PVR in the model. Injection of cultured rabbit RPE cells along with CTGF (200 ng) induced a mild PVR (Figure 3 c and d). Injection of cultured rabbit RPE along with PDGF resulted in PVR in 90% (10/11) of rabbits within 2 wk. The PVR was mild and the membranes were paucicellular and nonfibrotic (Figure 3e). Optical coherence tomography revealed slight retinal traction in the area with an epiretinal membrane (Figure 4a). Histologic examination revealed thin epiretinal membranes with low cellularity and no significant fibrosis (Figure 4c). However injection of rhCTGF (200 ng) 1 wk after injection of RPE + PDGF BB (50 ng) produced a thick fibrotic membrane with focal traction retinal detachment after the second injection (Figure 3f), and 100% of the rabbits in the group developed PVR (10/10). Optical coherence tomography showed the combined injection of PDGF and CTGF resulted in traction from the overlying fibrotic membrane associated with RD (Figure 4b). Histologic analysis showed a densely fibrotic epiretinal membrane attached to the retina with associated RD (Figure 4d). We have previously shown that subretinal injection of Ad CMV, CTGF or Ad CMV, GFP results in preferential infection of normal RPE monolayer and does not result in retinal detachment or PVR.38 Similarly, when RPE cells infected with Ad CMV, GFP are injected into the vitreous cavity, there is no evidence of PVR (Figure 3g). However, when RPE cells infected with Ad CMV, CTGF are injected intro the vitreous, a highly fibrotic PVR with extensive retinal detachment is induced (Figure 3h). PVR was more advanced in the AdCTGF induced PVR than the PVR induced using rhCTGF (Table 2). It is likely that this is a result of increased CTGF dose in the AdCTGF experiments. RPE cells transduced with AdCTGF would show continuous, high production of CTGF, as opposed to the single pulse of CTGF provided in the CTGF injection model.

Table 2.

PVR Grade in 8 Experimental Models. Classification of PVR was based on clinical findings according Fastenberg.37 Stage 0: Normal retina; Stage 1: Intravitreal membrane; Stage 2: Focal traction, localized vascular changes, hyperemia, engorgement dilation; blood vessel elevation; Stage 3: Localized detachment of medullary ray (vascularized portion of the retina); Stage 4: Extensive retinal detachment; total medullary ray detachment; peripapillary retinal detachment; Stage 5: Total retinal detachment, retinal folds and holes.

| PVR formation (grade 0–5) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitreous injection | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| RPE cells (n=3) | 3 | |||||

| RPE +CTGF (n=5) | 5 | |||||

| CTGF (n=2) | 2 | |||||

| PDGF (n=2) | 2 | |||||

| RPE+PDGF (n=11) | 1 | 8 | 2 | |||

| RPE+PDGF+CTGF (n=10) | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | ||

| Ad CMV, CTGF (n=5) | 1 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Ad CMV, GFP (n=3) | 3 | |||||

Figure 3.

Experimental PVR in rabbits: Ocular fundus photographs at 2 week time point. Photograph of normal fundus in vivo (a), and from a normal dissected, enucleated eye (b). Note that in the rabbit eye there is a vascularized band of myelinated axons (medullary ray) on both sides of the optic disc. Injection of RPE cells + CTGF results in mild PVR with focal membrane formation (c, arrows); the thin, non-fibrotic membrane is clearly seen adjacent to the optic disc after dissection of the enucleated eye (d, arrow). Injection of RPE cells + PDGF results in a mild non-fibrotic PVR with focal retinal detachment (e, arrows). Injection of RPE cells + PDGF + CTGF results in severe, fibrotic PVR with retinal detachment (f, arrows). Intravitreal injection of RPE cells infected with Ad, CMV, GFP does not result in PVR (g); however, injection of RPE cells infected with Ad, CMV. CTGF results in thick fibrotic PVR membranes with extensive retinal detachment (h, arrows).

Figure 4.

Experimental PVR in rabbits: Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and histology at 2 week time point. PVR induced by injection of rabbit RPE cells + PDGF results in a thin epiretinal membrane on OCT (a, arrows) and on histologic analysis (c, arrow, H&E). PVR induced by injection of rabbit RPE cells + PDGF + CTGF results in a thick, optically dense epiretinal membrane on OCT (b, arrow); histology shows a fibrotic, cellular membrane attached to the retinal surface (d, arrow, H&E).

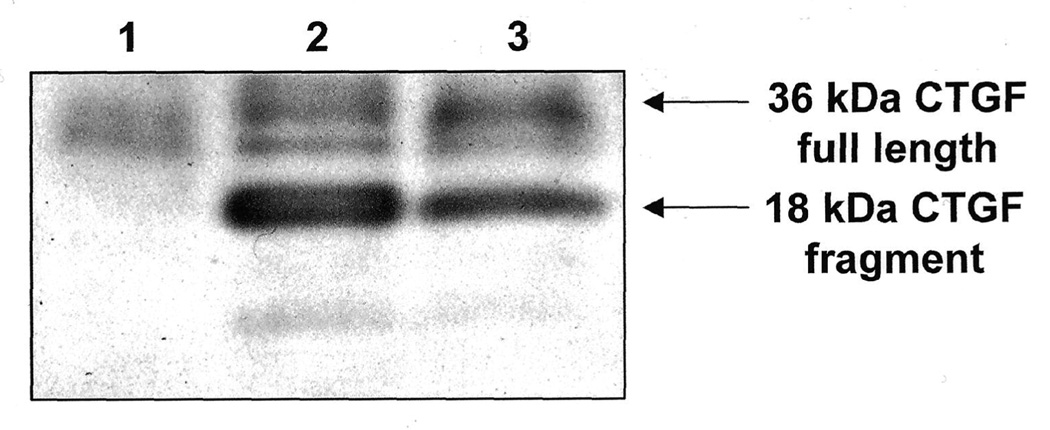

CTGF Levels in Rabbit Vitreous

Western blots of normal rabbit vitreous demonstrate that vitreous contains a low level of whole CTGF (Figure 5). However, when PVR is induced by either injection of RPE cells infected with adenovirus expressing full length human CTGF, or injection of RPE cells with PDGF and rhCTGF, there was a modest increase in whole CTGF and a much more prominent accumulation of an 18 kDa CTGF fragment in the vitrous at d14 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

CTGF Expression in Experimental PVR in Rabbit: Western blot of vitreous for CTGF at 2 week time point. Lane 1, intravitreous injection of saline; lane 2, injection of rabbit RPE infected with Ad CMV, CTGF; lane 3 injection of rabbit RPE+PDGF+CTGF. Control rabbit vitreous (lane 1) contains a low level of full-length CTGF but no CTGF fragments. Vitreous from animals with PVR (lanes 2, 3) show increased levels of full length CTGF and prominent expression of CTGF 18 kDa fragment.

CTGF was also measured at d14 in the vitreous of animals with experimental PVR injected with RPE + PDGF + rhCTGF by ELISA (Figure 2B). ELISA specific to human + rodent CTGF revealed a CTGF (N+whole) concentration of 15.15 ± 3.06 in untreated controls (n=5), 13.3 ± 3.55 in buffer-injected controls (n=12); which increased to 115.5 ± 35.21 (n=5) (P<0.01) in animals with experimental PVR. Human-specific ELISA showed that in d14 vitreous, most of the increase in CTGF level was rabbit in origin; however, the exact relative contribution is difficult to determine due to differences in antibody detection efficiencies. Plasma samples from these animals were also evaluated for CTGF (N+whole) and all samples were below level of detection (results not shown) suggesting that there was not a systemic accumulation of CTGF in these animals.

In order to confirm the local intraocular synthesis of CTGF in experimental rabbit PVR, we semi-quantitatively measured levels of CTGF mRNA in normal control retina and in retina and attached PVR membranes from rabbits with PVR induced by injection of RPE + PDGF + rhCTGF at d14. RT-PCR revealed that there was a 2 fold increased expression of CTGF mRNA in PVR retina/membrane samples compared to normal control retinas (P<0.05; Figure 2c). In order to evaluate the possibility that the accumulation of CTGF fragments in PVR was due to alternative exon splicing, oligo deoxynucleotide primers corresponding to sequences in the first and fifth exon of both human and rabbit CTGF genes were used to amplify full length CTGF cDNA. RNA isolated from normal rabbit retina, rabbit PVR retina/membranes, and a human RPE cell line (ARPE-19) were evaluated and in all cases only a single 1kb cDNA band was amplified indicating that there were no alternative splice products of the CTGF gene (results not shown).

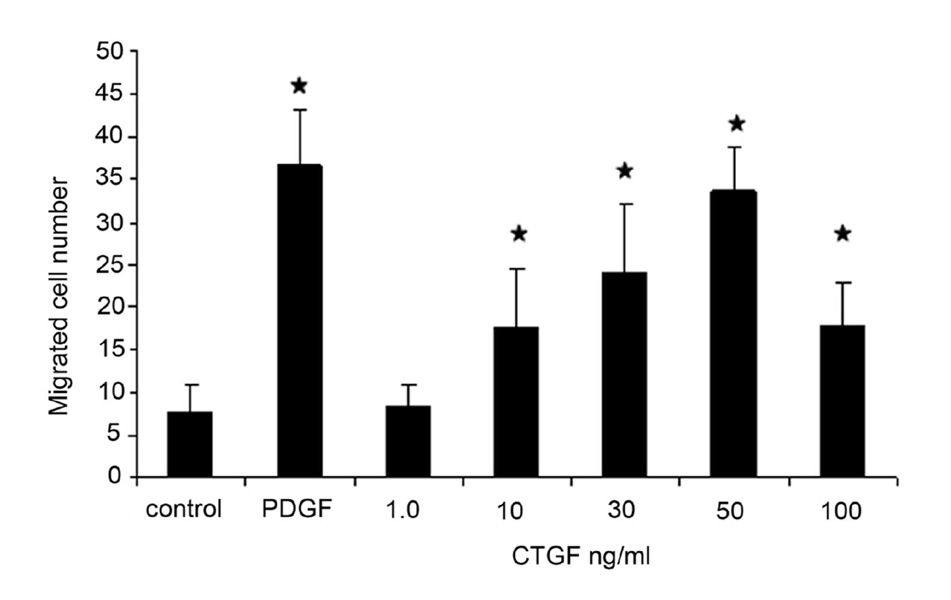

CTGF Stimulates Chemotactic Migration of RPE

Migration of human RPE in the modified Boyden chamber assay was stimulated by recombinant CTGF. The chemotactic response of RPE to whole molecular CTGF was dose-dependent over a range of 1–100 ng/ml (Figure 6). The migration response to full-length CTGF was similar to that seen for PDGF-BB (20 ng/ml). The addition of up to 10 ng/ml CTGF significantly increased cell migration (Figure 6), compared with control P<0.01.

Figure 6.

CTGF stimulates RPE cell migration. A dose-dependent increase in migrating human RPE cells was found using a modified Boyden chamber assay with a maximal effect at 50 ng/mL (asterisks, P<0.05). The maximal stimulation was similar to that found in response to PDGF-BB 20 ng/mL.

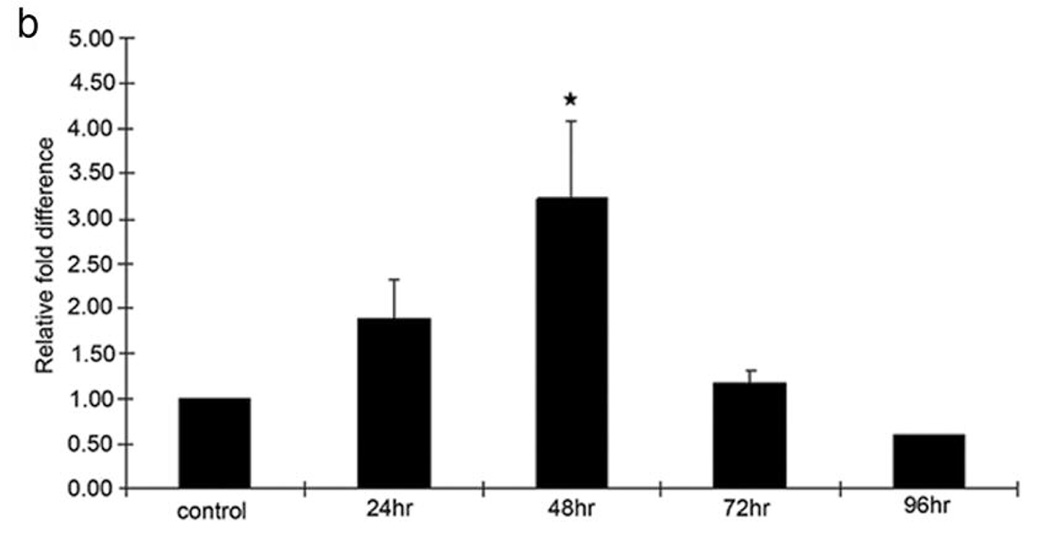

Type I Collagen Expression in Rabbit PVR Membrane and CTGF Stimulates expression of Type I Collagen mRNA and Protein in RPE Cells

Type 1 collagen expression was predominantly revealed in fibrotic rabbit PVR membranes by immunohistochemical staining (Figure 7a). A 3.5-fold increase in the expression of type I collagen mRNA was detected in CTGF-stimulated RPE cells, using quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 7b). The CTGF-induced upregulation of type I collagen mRNA in RPE cells was much higher than in controls at 48 h (P<0.01). The highest response of type I collagen protein production (2.81 ng/ml) was seen after stimulation with rhCTGF for 72 hours [compared with TGF-β 1.51ng/ml and control 0.53ng/ml (P<0.05)].

Figure 7.

Effect of CTGF on expression of type 1 Collagen. In a) immunohistochemical stain for type 1 collagen (red chromogen, hematoxylin counterstain) is shown in PVR membrane induced by intravitreal injection of RPE cells + PDGF + CTGF. Induction of type 1 collagen mRNA in cultured RPE stimulated with CTGF is shown in b) using quantitative real time PCR. Increased levels of type 1 collagen mRNA were seen after CTGF stimulation at 24 h, reaching a peak at 48 h. (*, P<0.01, compared with control)

Discussion

Retinal pigment epithelial cells play a prominant role in the pathogenesis of PVR.4,8,9 In PVR, proliferating RPE cells transdifferentiate into myofibroblasts or mesenchymal-like cells to form epiretinal membranes.4,8,37 These membranes exert a contractile force on the attached underlying retina, leading to detachment.4,8,37 Fibrosis of epiretinal membranes involves increased ECM production and accumulation in the RPE. Herein, we provide the first description of the effect of CTGF on experimental PVR. In the present study, we used human PVR specimens and a rabbit PVR model to gain further insight into the potential role of CTGF in the fibrogenesis of PVR.

We and others have shown that CTGF is prominently expressed in human PVR membranes.39, 40 Here we showed that CTGF expression is most prominent in stromal cells within the membrane. Our finding that much of the CTGF expression is localized in cells that stain positively for pan-cytokeratin, a RPE specific marker in the retina,38 further supports the idea that RPE play a central role in the pathogenesis of PVR.

We also found that CTGF accumulated in the vitreous of human patients with PVR. When compared to vitreous from patients with non-proliferative control disorders (macular hole, macular pucker and epiretinal membrane), vitreous from patients with retinal detachment with PVR showed high levels of CTGF (P<0.01), while vitreous from patients with retinal detachment without PVR showed only a moderate increase (P<0.05).41 Interestingly, it appeared that in PVR the increase in total vitreal CTGF is due to accumulation of the N-terminal half fragment of CTGF.

In order to evaluate these findings in more detail, the accumulation of CTGF in the vitreous was studied in two models of experimental rabbit PVR. Aspirates of vitreous from the PVR rabbit models were analyzed by CTGF immunoblot and ELISA to determine whether full-length CTGF or CTGF half fragments accumulate. Consistent with the human studies, we found that experimental PVR was associated with a predominant accumulation of CTGF 18 kDa half fragments.

Together, these results suggest that the N-terminal half fragments of CTGF may play an important role in fibrosis formation in vivo. These results are consistent with the findings of Grotendorst,42 who demonstrated that myofibroblast differentiation and collagen synthesis were preferentially induced by the N-terminal domain of CTGF; therefore the N-terminal half fragment of CTGF may represent a biomarker for fibrotic disease.43 C-terminal fragments were extremely rare in all our samples, suggesting that C-terminal CTGF may be rapidly degraded or bind to target cells and the ECM where it might be sequestered and serve as a persistence stimulator in fibrotic tissue. Ball et al22 presented evidence that 16-, 18- and 20-KD CTGF are intermediate forms produced by proteolysis of the 38-kDa CTGF. Steffen et al21 indicated that those soluble forms of CTGF can stimulate mitosis in fibroblasts. Further support for the contention that full length CTGF is locally expressed in experimental eyes with PVR, we evaluated expression of CTGF mRNA and found a 2 fold increase in full length CTGF mRNA expression in PVR retina/membranes when compared to normal rabbit retina. Furthermore these RT-PCR experiments showed no evidence of alternative splicing of the CTGF gene. Overall, our experiments are consistent with the idea that the accumulation of CTGF half fragments in the PVR vitreous is due to proteolysis of locally synthesized whole CTGF.

The overall tendency for vitreous CTGF levels to be higher in human eyes with RD + PVR than in those with RD alone, together with the high CTGF levels in the vitreous of rabbits with PVR, suggests that CTGF plays a critical role in the development of retinal fibrosis. We previously showed that expression of CTGF in RPE cells in vitro is stimulated by TGF-β39 suggesting that the synthesis and secretion of CTGF may depend upon stimulation from other growth factors or cytokines that are present in PVR. Experiments have shown that RPE cell transdifferentiation is modulated by soluble growth factors and cytokines.8,44 Fibroblast growth factor, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1, interleukin-6, interferon-γ, TGF-β, PDGF, and insulin-like growth factor, among others, are elevated in PVR.4,5,8,16 These polypeptides are capable of activating RPE. The RPE may then respond to CTGF stimulation to induce RPE behavior changes, including proliferation, migration, matrix synthesis, enzyme production, and contraction. In the present study, although we injected human CTGF into the rabbit vitreous, an increased amount of rabbit CTGF was also found in the vitreous. This suggests that upon stimulation by exogenous CTGF, the host cell itself is able to produce CTGF, thereby enhancing fibrosis. The induction of rabbit CTGF may also be due to the exposure of host RPE to TGF-β. The TGF-β may be released from the vitreous into the retina where it may stimulate the RPE to produce more rabbit CTGF.

Fibrosis is characterized by extracellular matrix deposition. In the present study, we investigated the effect of rhCTGF on the expression of type I collagen mRNA and protein in RPE cells and the expression of type I collagen in experimental rabbit PVR membrane as demonstrated by immunostaining. Our findings showed that the type I collagen was expressed strongly throughout the extracellular matrices of the rabbit PVR membrane. This result correlates with collagen type I expression in vitro, which showed a significant upregulation in type I collagen mRNA and protein expression in RPE cells after exposure to CTGF. Delayed collagen mRNA expression after CTGF stimulation is in accord with the results of previous experiments.45 Pre-treatment of RPE cells with TGF-β enhanced the expression of type I collagen stimulated by CTGF. The enhanced expression of interstitial type I collagen correlated with an increased accumulation of CTGF in specimens from patients with PVR, suggesting a close relationship between CTGF upregulation and ECM production. Besides CTGF, the increased ECM deposition may relate to TGF-β upregulation in PVR because it was found that high concentration of TGF-β in subretinal fluid was associated with retinal detachment in the complication of retinal strands.46

It is well accepted that TGF-β is a potent inducer of fibrosis and that it regulates CTGF expression. We found previously that TGF-β promotes CTGF protein expression in RPE,47 while Kanemoto48 recently reported that the blockade of endogenous CTGF using an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide significantly attenuated TGF-β-induced extracellular matrix synthesis in kidney cells. Interestingly, bleb failure after glaucoma filtration surgery is believed to be related to high ECM synthesis stimulated by CTGF.49 Our current study shows that type I collagen production is highly stimulated by CTGF alone without TGF-β addition. These findings support the idea that the CTGF-induced fibrosis pathway may be partially independent of TGF-β.50

Recent studies have suggested the possibility that in PVR, some of the pathologic effects of the disease may be mediated through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). While a minority patients with PVR have been reported to have vitreous levels of VEGF in the low ng/ml range, the overall levels of CTGF and VEGF in PVR patients do not correlate with each other.55 In order to determine whether VEGF was involved in the pathogenesis of our experimental PVR model (injection of RPE + PDGF + rhCTGF), VEGF levels in the vitreous were measured by ELISA in 6 rabbits in which vitreous was available on d0 as well as d7 or d14 after induction of PVR (results not shown). We found no statistically significant increase in VEGF expression in the vitreous at d7 or d14 compared to d0 controls (paired t-test; p=0.51 at d7, p=0.42 at d14), thus it is unlikely that CTGF is acting through VEGF in our model system.

RPE migration plays an important role in the pathogenesis of PVR.8,9 To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that full length CTGF promotes RPE cell migration by chemotaxis. The result is consistent with studies reporting stimulation of cell adhesion and/or migration by CTGF or related peptides in different cell types, such as endothelial cells, vascular smooth muscle cells, fibroblasts and chondrocytes.51, 52, 53, 54 Recently published studies show that CTGF stimulates metalloprotease expression in smooth muscle cells, activates phosphorylation of p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase, and simulates RPE proliferation55, 56 Taken together, these studies suggest that CTGF modulates wound healing by remodeling the microenvironment. Thus, it seems likely that CTGF has a central role in the development of fibrosis and as such may represent a useful therapeutic target.57

PVR in animals has been established by vitreous injection of RPE cells, plasma, blood, growth factors (including PDGF), and other types of cells.5–9,58–60 However, previously published studies focused on the induction of PVR rather than on the formation of PVR fibrosis. In the present animal model, injection of CTGF 1 week after injection of RPE cells and PDGF induced strong fibrosis. No significant PVR or PVR fibrosis was induced with injection of CTGF alone or CTGF combined with RPE or adenovirus transfection of resting RPE with Ad CMV, GFP. This suggests that RPE cells must first be activated to respond to the stimulation of CTGF.61

In our study, RPE activation is stimulated by addition of PDGF-BB. Although RPE cells express both alpha and beta PDGF receptors, recent studies have suggested that PDGF receptor alpha plays a more critical role in the development of experimental and human PVR.62, 63 Our use of PDGF-BB ensures activation of RPE since PDGF-BB is an agonist for both alpha and beta PDGF receptors, induces phosphorylation of p44/42 MAP kinase, and stimulates RPE chemotaxis.64

In the present study, we show that RPE cells respond chemotactically to rhCTGF and increase collagen-1 mRNA and protein expression in vitro. We then demonstrate that human PVR membranes contain CTGF and that there is a prominent accumulation of the N-terminal half fragment of CTGF in the vitreous of both humans and rabbits with PVR. Importantly, we found that when rhCTGF is injected into the vitreous of rabbits with mild PVR, the membrane becomes densely fibrotic. This is the first direct evidence, using an in vivo experimental system, that CTGF mediates pathologic intraocular fibrosis.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by grants EY02061 and EY03040 from the National Eye Institute; by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness; and by the Arnold & Mabel Beckman Foundation.

The authors would like to thank Christine Spee for culture of human and rabbit RPE, Dr. Dongxia Li, Tom Crowley, Evelene Lomongsod and Dave Gervasi for the ELISA qualification work and analyses, Susan Clarke for editing assistance, Tom Odgen, M.D., for his scientific review of the paper, and Laurie Dusin MS, for statistical assistance.

References

- 1.Friedlander M. Fibrosis and diseases of the eye. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:576–586. doi: 10.1172/JCI31030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith LE. Pathogenesis of retinopathy of prematurity. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:469–473. doi: 10.1016/S1084-2756(03)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schlingemann RO. Role of growth factors and the wound healing response in age-related macular degeneration. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:91–101. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruger EF, Nguyen QD, Ramos-Lopez M, Lashkari K. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy after trauma. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2002;42:129–143. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200207000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukherjee S, Guidry C. The insulin-like growth factor system modulates retinal pigment epithelial cell tractional force generation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:1. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cowley M, Conway BP, Campochiaro PA, Kaiser D, Gaskin H. Clinical risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1147–1151. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020213027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardillo JA, et al. Post-traumatic proliferative vitreoretinopathy. The epidemiologic profile, onset, risk factors, and visual outcome. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1166–1173. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campochiaro PA. Pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2001. pp. 2221–2227. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charteris DG. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy: pathobiology, surgical management, and adjunctive treatment. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:953–960. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.10.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weller M, Esser P, Bresgen M, Heimann K, Wiedemann P. Thrombospondin: a new attachment protein in preretinal traction membranes. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1992;2:10–14. doi: 10.1177/112067219200200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiscott PS, Grierson I, McLeod D. Natural history of fibrocellular epiretinal membranes: a quantitative, autoradiographic, and immunohistochemical study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:810–823. doi: 10.1136/bjo.69.11.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araiz JJ, Refojo MF, Arroyo MH, Leong FL, Albert DM, Tolentino FI. Antiproliferative effect of retinoic acid in intravitreous silicone oil in an animal model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Planck SR, et al. Expression of growth factor mRNA in rabbit PVR model systems. Curr Eye Res. 1992;11:1031–1039. doi: 10.3109/02713689209015074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lean JS, van Der Zee WA, Ryan SJ. Experimental model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) in the vitrectomised eye: effect of silicone oil. Br J Ophthalmol. 1984;68:332–335. doi: 10.1136/bjo.68.5.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francke M, et al. Upregulation of extracellular ATP-induced Muller cell responses in a dispase model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:870–881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agrawal RN, He S, Spee C, Cui JZ, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. In vivo models of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:67–77. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cordeiro MF, Schultz GS, Ali RR, Bhattacharya SS, Khaw PT. Molecular therapy in ocular wound healing. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1219–1224. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.11.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leask A, Abraham DJ. The role of connective tissue growth factor, a multifunctional matricellular protein, in fibroblast biology. Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;81:355–363. doi: 10.1139/o03-069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grotendorst GR. Connective tissue growth factor: a mediator of TGF-beta action on fibroblasts. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00010-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perbal B. NOV (nephroblastoma overexpressed) and the CCN family of genes: structural and functional issues. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:57–74. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steffen CL, Ball-Mirth DK, Harding PA, Bhattacharyya N, Pillai S, Brigstock DR. Characterization of cell-associated and soluble forms of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) produced by fibroblast cells in vitro. Growth Factors. 1998;15:199–213. doi: 10.3109/08977199809002117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ball DK, et al. Characterization of 16- to 20-kilodalton (kDa) connective tissue growth factors (CTGFs) and demonstration of proteolytic activity for 38-kDa CTGF in pig uterine luminal washings. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:828–835. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.4.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frazier K, Williams S, Kothapalli D, Klapper H, Grotendorst GR. Stimulation of fibroblast cell growth, matrix production, and granulation tissue formation by connective tissue growth factor. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107:404–411. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12363389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hishikawa K, Oemar BS, Tanner FC, Nakaki T, Fujii T, Luscher TF. Overexpression of connective tissue growth factor gene induces apoptosis in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Circulation. 1999;100:2108–2112. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.20.2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hishikawa K, Nakaki T, Fujii T. Connective tissue growth factor induces apoptosis via caspase 3 in cultured human aortic smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;392:19–22. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen CC, Chen N, Lau LF. The angiogenic factors Cyr61 and connective tissue growth factor induce adhesive signaling in primary human skin fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10443–10452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sato S, et al. Serum levels of connective tissue growth factor are elevated in patients with systemic sclerosis: association with extent of skin sclerosis and severity of pulmonary fibrosis. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:149–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi-Wen X, et al. Autocrine overexpression of CTGF maintains fibrosis: RDA analysis of fibrosis genes in systemic sclerosis. Exp Cell Res. 2000;259:213–224. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lasky JA, et al. Connective tissue growth factor mRNA expression is upregulated in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L365–L371. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.2.L365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito Y, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in human renal fibrosis. Kidney Int. 1998;53:853–861. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.1998.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clarkson MR, Gupta S, Murphy M, Martin F, Godson C, Brady HR. Connective tissue growth factor: a potential stimulus for glomeruloslcerosis and tubulointerstitial fibrosis in progressive renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:543–548. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199909000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen MM, Lam A, Abraham JA, Schreiner GF, Joly AH. CTGF expression is induced by TGF-beta in cardiac fibroblasts and cardiac myocytes: a potential role in heart fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1805–1819. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cicha I, Yilmaz A, Suzuki Y, Maeda N, Daniel WG, Goppelt-Struebe M, Garlichs CD. Connective tissue growth factor is released from platelets under high shear stress and is differentially expressed in endothelium along atherosclerotic plaques. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2006;35:203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He S, Wang HM, Ye J, Ogden TE, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Dexamethasone induced proliferation of cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13:257–261. doi: 10.3109/02713689408995786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He PM, He S, Garner JA, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Retinal pigment epithelial cells secrete and respond to hepatocyte growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:253–257. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang XF, Cui J, Prasad SS, Matsubara JA. Altered Gene Expression of Angiogenic Factors Induced by Calcium-Mediated Dissociation of Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1508–1515. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fastenberg DM, Diddie KR, Dorey K, Ryan SJ. The role of cellular proliferation in an experimental model of massive periretinal proliferation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93:565–572. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)77370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin M, Chen Y, He S, Ryan SJ, Hinton DR. Hepatocyte growth factor and its role in the pathogenesis of retinal detachment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:323–329. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hinton DR, He S, Jin ML, Barron E, Ryan SJ. Novel growth factors involved in the pathogenesis of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eye. 2002;16:422–428. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cui JZ, Chiu A, Maberley D, Ma P, Samad A, Matsubara JA. Stage specificity of novel growth factor expression during development of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Eye. 2007;21:200–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Setten G, Berglin L, Blalock TD, Schultz G. Detection of connective tissue growth factor in subretinal fluid following retinal detachment: possible contribution to subretinal scar formation, preliminary results. Ophthalmic Res. 2005;37:289–292. doi: 10.1159/000087698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grotendorst GR, Duncan MR. Individual domains of connective tissue growth factor regulate fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation. FASEB J. 2005;19:729–738. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3217com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roestenberg P, Van Nieuwenhoven FA, Wieten L, Boer P, Diekman T, Tiller AM, Wiersinga WM, Oliver N, Usinger W, Weitz S, Schlingemann RO, Goldschmeding R. Connective tissue growth factor is increased in plasma of type 1 diabetic patients with nephropathy. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1164–1170. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thumann G, Hinton DR. Cell biology of the retinal pigment epithelium. In: Ryan SJ, editor. Retina. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001. pp. 104–121. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paradis V, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor in experimental rat and human liver fibrosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:968–976. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirase K, Sugiyama T, Ikeda T, Sotozono C, Yasuhara T, Koizumi K, Kinoshita S. Transforming growth factor beta (2) increases in subretinal fluid in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment with subretinal strands. Ophthamologica. 2005;219:222–225. doi: 10.1159/000085731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He S, Jin ML, Worpel V, Hinton DR. A role for connective tissue growth factor in the pathogenesis of choroidal neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1283–1288. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.9.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanemoto K, et al. Connective tissue growth factor participates in scar formation of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1615–1625. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000096711.58115.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Esson DW, et al. Expression of connective tissue growth factor after glaucoma filtration surgery in a rabbit model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:485–491. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qi W, Chen X, Poronnik P, Pollock CA. Transforming growth factor-beta/connective tissue growth factor axis in the kidney. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007 Jan 20; doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Babic AM, Chen CC, Lau LF. Fisp12/mouse connective tissue growth factor mediates endothelial cell adhesion and migration through integrin alphavbeta3, promotes endothelial cell survival, and induces angiogenesis in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2958–2966. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan WH, Pech M, Karnovsky MJ. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell growth and migration in vitro. Eur J Cell Biol. 2000;79:915–923. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao R, Brigstock DR. A novel integrin alpha5beta1 binding domain in module 4 of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) promotes adhesion and migration of activated pancreatic stellate cells. Gut. 2006;55:856–862. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.079178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoshijima M, Hattori T, Inoue M, Araki D, Hanagata H, Miyauchi A, Takigawa M. CT domain of CCN2/CTGF directly interacts with fibronectin and enhances cell adhesion of chondrocytes through integrin α5 β1. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:1376–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kita T, Hata Y, Miura M, Kawahara S, Nakao S, Ishibashi T. Functional characteristics of connective tissue growth factor on vitreoretinal cells. Diabetes. 2007;56:1421–1428. doi: 10.2337/db06-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fan WH, Karnovsky MJ. Increased MMP-2 expression in connective tissue growth factor over-expression vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9800–9805. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kuiper EJ, de Smet MD, van Meurs JC, et al. Association of connective tissue growth factor with fibrosis in vitreoretinal disorders in the human eye. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1457–1462. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.10.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Frenzel EM, Neely KA, Walsh AW, Cameron JD, Gregerson DS. A new model of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2157–2164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sakamoto T, et al. Inhibition of experimental proliferative vitreoretinopathy by retroviral vector-mediated transfer of suicide gene. Can proliferative vitreoretinopathy be a target of gene therapy? Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1417–1424. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30850-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joondeph BC, Peyman GA, Khoobehi B, Yue BY. Liposome-encapsulated 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Ophthalmic Surg. 1988;19:252–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mori T, Kawara S, Shinozaki M, Hayashi N, Kakinuma T, Igarashi A, Takigawa M, Nakanishi T, Takehara K. Role and interaction of connective tissue growth factor with transforming growth factor-beta in persistent fibrosis: A mouse fibrosis model. J Cell Physiol. 1999;181:153–159. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199910)181:1<153::AID-JCP16>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lei H, Hovland P, Velez G, Haran A, Gilbertson D, Hirose T, Kazlauskas A. A potential role for PDGF-C in experimental and clinical proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:2335–2342. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ikuno Y, Leong FL, Kazlauskas A. Attenuation of experimental proliferative vitreoretinopathy by inhibiting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3107–3116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hinton DR, He S, Graf K, Yang D, Hsueh WA, Ryan SJ, Law RE. Mitogen-activated protein kinase activation mediates PDGF-directed migration of RPE cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;25:11–15. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]