Abstract

Objectives. We examined the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health risk behaviors, and we explored whether adult health risk behaviors or mental health problems mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health problems and health care utilization.

Methods. We used logistic regression to analyze data from the Mental Health Supplement of the Ontario Health Survey, a representative population sample (N = 8116) of respondents aged 15 to 64 years.

Results. We found relationships between childhood sexual abuse and smoking (odds ratio [OR] = 1.52; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.16, 1.99), alcohol problems (OR = 2.44; 95% CI = 1.74, 3.44), obesity (OR = 1.61; 95% CI = 1.14, 2.27), having more than 1 sexual partner in the previous year (OR = 2.34; 95% CI = 1.44, 3.80), and mental health problems (OR = 2.26; 95% CI = 1.78. 2.87). We also found relationships between these factors (with the exception of obesity) and childhood physical abuse. Mediation analysis suggested that health risk behaviors and particularly mental health problems are partial mediators of the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health.

Conclusions. Public health approaches that aim to decrease child abuse by supporting positive parent–child relationships, reducing the development of health risk behaviors, and addressing children's mental health are likely to improve long-term population health.

Recent studies have suggested a link between childhood abuse and adult health. Researchers have reported associations between childhood abuse and higher rates of medical problems, poor self-rated health, pain symptoms, and functional disability.1–6 A history of childhood maltreatment is also associated with higher health care utilization (more physician visits, surgeries, and hospitalizations, as well as higher annual health costs) in adulthood.7–9

There is limited understanding of the mechanisms linking childhood abuse and adult health. Childhood maltreatment may have an adverse effect on adult health as a result of biological and psychosocial factors. Physiological research demonstrates that childhood maltreatment can have negative effects on the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems.10–13 Kuh et al. suggest that children's environments can influence their attitudes, beliefs, academic achievements, and development of health behaviors.14 Parents can inadvertently promote poor health habits and lack of autonomy in children by failing to teach important skills, by communicating poor attitudes, and by providing negative role models.

Health risk behaviors and mental health problems may be mediators in the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health. Considerable evidence supports an association between childhood abuse and health risk behaviors such as smoking, poor nutrition, sedentary lifestyle, high alcohol consumption, and higher-risk sexual practices.6,15–18 Childhood abuse appears to have negative effects on self-esteem and is associated with high levels of anxiety, depression, and anger.19–21 These mental health problems may play a role in the development of health risk behaviors22,23 and may also influence long-term health by causing troubled relationships, poor school achievement, premature parenthood, and unemployment.24 The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study, based on data from health maintenance organizations, reported that health risk behaviors and depression mediated the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and ischemic heart disease25 and liver disease,26 providing evidence that health risk behaviors and mental health problems may be part of a causal chain linking childhood abuse to adult health problems.

Given the high prevalence rates of childhood abuse and its long-term effects on health, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms connecting one to the other, to facilitate the development of public health strategies to address these problems. To the best of our knowledge, no previous population-based studies have examined whether health risk behaviors and mental health problems may be mediating factors in the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health. Population studies are important because clinical samples are not representative of the population and are prone to selection biases that may give inaccurate estimates. In addition, studying a broader scope of health indicators may be more informative for population health applications.

Our goal was to use population-based cross-sectional data to examine the association between childhood physical and sexual abuse and adult health risk behaviors (smoking, alcohol problems, physical inactivity, obesity, and risky sexual behaviors). We also explored whether health risk behaviors or mental health problems mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health problems and health care utilization.

METHODS

Data Source

The Ontario Health Survey (OHS) is a cross-sectional population health survey of Ontario residents 15 years or older. The Ontario Ministry of Health commissioned the survey to provide information for health planning and policy development. The OHS Mental Health Supplement (N = 9953) was subsequently collected between November 1990 and March 1991 from the second half of the sample of OHS respondents (n = 13 002) to study the prevalence, severity, and risk factors of psychiatric disorders and to gather data on mental health services. We limited our sample to respondents aged 15 to 64 years (n = 8116), because older participants were not questioned on all the variables we included in our study. A small proportion of residents were excluded: foreign service personnel, homeless people, people living in institutions (e.g., hospitals and prisons), First Nations people living on reserves, and residents of extremely remote locations.27

Boyle et al.27 provide a comprehensive description of the OHS, which used a multistage design with stratification and clustering to ensure representation and feasibility. The survey was conducted in 2 stages. First, a probability sample averaging 46 enumeration areas was selected from each of the province's 42 public health units. Enumeration areas are the smallest geographical units for which census counts can be retrieved by automatic means. These areas were sorted into urban and rural strata to ensure proper representation. Second, probability samples of 15 households from urban enumeration areas and 20 households from rural enumeration areas were selected. The 15- to 24-year-old age group was oversampled to increase statistical reliability at this age level.

Study Variables

Childhood abuse and health variables are described in Table 1. Good reliability and validity were found for the conflict tactics scale28 in assessing childhood physical abuse and for a subset of questions from the National Population Survey of Canada29 in assessing childhood sexual abuse. We examined self-rated health, number of medical conditions, pain that restricts daily activity, disability because of physical health, and health care utilization (frequency of emergency department and health professional use).30 Alcohol abuse and dependence and lifetime history of mental health problems were assessed with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview,27 a structured interview based on the criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition.31 Structured face-to-face interviews and self-administered questionnaires were used to collect data for these study variables, as indicated in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Description of Child Abuse and Health Variables: Ontario Health Survey Mental Health Supplement, 1990–1991

| Study Variables | Description | Prevalence in Sample (N = 8116),a % | Missing Data, No. |

| Childhood Abuse | |||

| Childhood physical abuse (asked retrospectively)b | On the basis of an abridged 7-question version of the conflict tactics scale,28 wording was, “When you were growing up, how often did any adult do any of the things on this list to you—often, sometimes, rarely, or never?”c | 26.1 | 311 |

| Childhood sexual abuse (asked retrospectively)b | On the basis of 4 items from the National Population Survey of Canada,54 wording was, “When you were growing up, did any adult ever do any of these things to you against your will?”d | 9.0 | 325 |

| Health indicators | |||

| Multiple health problemse | Reported more than 2 medical conditions in response to 10 open-ended questions. For example, “What was the health problem responsible for staying in bed?” | 16.1 | 0 |

| Poor self-rated healthf | Answered “fair” or “poor” to the question, “In general, compared with other people your age, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” | 6.8 | 1194 |

| Painf | Answered “pain interferes with some or most activities” to the question, “Which of the following sentences best describes the effect of pain or discomfort you usually experience?” | 7.7 | 1249 |

| Disabilitye | Rated on the basis of answers to 44 questions about the degree of disability currently experienced. Example: “Are you limited at all in your ability to do this kind of work around the house because of a physical health problem?” | 10.1 | 68 |

| Health utilization | |||

| High emergency department usee | Answered “2 or more visits” to the question, “During the past 12 months, did you use an emergency room at a hospital? How many times?” | 6.0 | 24 |

| High health professional usee | Answered “25 or more visits” to a series of questions about family doctor, specialist, nurse, dentist, pharmacist, and psychologist visits. Example: “How many times did you go see a specialist about your health during the past 12 months?” | 9.3 | 24 |

| Health risk behaviors | |||

| Smokingf | Currently smoking any amount of cigarettes or cigars on a daily basis. | 28.5 | 1301 |

| Alcohol abusee | Met DSM-III-R criteria for alcohol abuse and dependence in the previous 12 months. | 12.0 | 53 |

| Low exercisef | Reported less than 30 minutes of participation in physical activities per day on average over the previous month. | 70.5 | 1537 |

| Obesityf | Body mass indexg ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 13.3 | 1659 |

| More than 1 sexual partnerf | Answered “more than 1 partner” to the question,“In the last year, how many sexual partners did you have?” | 8.0 | 1884 |

| Mental health problemse | Met lifetime DSM-III-R criteria for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, or bulimia. | 25.5 | 2 |

Note. DSM-III-R = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition.31

Weighted data.

Variable from self-administered questionnaire that was returned directly to interviewer in sealed envelope.

Physical abuse was defined as often or sometimes being pushed, grabbed, or shoved, having something thrown at the respondent, or being hit with something. It also included often, sometimes, or rarely being kicked, bitten, punched, choked, burned or scalded, or physically attacked in some other way. Being slapped or spanked was not included in the definition because of the high prevalence of corporal punishment in this population.

Sexual abuse was defined as an adult exposing himself or herself to the respondent more than once, an adult threatening the respondent in an attempt to have sex with the respondent, being touched in a private area by an adult, having an adult attempt to have sex with the respondent, or being sexually attacked.

Variable from face-to-face interview.

Variable from self-administered questionnaire left with the respondents, 1160 of which were not returned.

Body mass index is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Data Analysis

We used SPSS for Windows version 10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) to conduct all data analyses. The respondents' sociodemographic characteristics were described using weighted data. We used logistic regression to test 2 sets of associations: (1) the associations between childhood abuse and adult health risk behaviors and mental health problems and (2) the associations between abuse and health indicators in childhood and the potential mediators in the model. Covariates in all models included age at interview, gender, high school education, and marital status. Adjustments were made in variance estimates to account for design effects (stratification and clustering). We also used sampling weights (probability weights or relative weights) to adjust for sampling techniques and nonresponders.

To decrease the percentage of missing cases and minimize the bias of key variable estimates, we created a dummy variable adjustment for health risk behaviors with substantial amounts of missing data (smoking, obesity, and more than 1 sexual partner) and added it to the regression model. We assigned a dummy variable to each of the 3 health risk behavior variables, in which the variable was coded 1 if a value in the health risk behavior was missing and 0 if a value was present.32 Missing values for the 3 health risk behaviors were replaced by 0. This method preserved cases in which a data point was missing in one variable and not the other and controlled for the effects of the missing data.

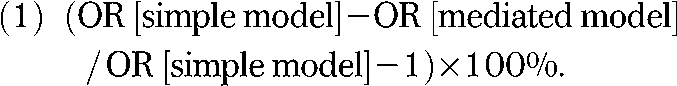

The mediation analyses were intended to test the hypothesis that the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health is mediated by health risk behaviors and mental health problems. According to Baron and Kenny's approach,33 a variable is said to function as a mediator when the following conditions hold for 3 regression equations: (1) the predictor variable (in our study, abuse) must account for variation in the outcome variable (health); (2) the predictor variable (abuse) must account for variation in the presumed mediator (health risk behavior or mental health problems); and (3) when the mediator is added to the model, its presence reduces the strength of a previously significant relationship between the predictor variable and the outcome variable, and it accounts for variation in the outcome variable. We used the odds ratios (ORs) from the logistic regressions in the following formula to calculate the percentage reduction in the strength of this relationship:

|

Baron and Kenny state that perfect mediation holds if the predictor variable has no effect on the outcome variable when the mediator variable is controlled for.33 Because many factors affect health, a more realistic goal in evaluating a mediator is to consider whether the mediator significantly attenuates the relationship (partial mediation).

RESULTS

The study population was almost evenly divided between men (49.8%) and women (50.2%). Sixty percent of the respondents were aged 15 to 39 years, 40% were aged 40 to 64 years, 70% had at least a high school education, and 73% reported that they were currently married or living as a common-law couple. Respondents reported high rates of childhood abuse: 26% reported physical abuse, and 9% reported sexual abuse. Prevalence rates of health risk behaviors, mental health problems, health indicators, and health care utilization indicators for the total sample are found in Table 1.

Childhood Abuse and Adult Health and Health Care Utilization

We have described the first step in our mediation analysis—evaluating the relationship between abuse and health—elsewhere.1 We reported finding a relationship of moderate strength between childhood abuse and most health and health care utilization indicators, after we controlled for demographic characteristics. We found no relationship between childhood sexual abuse and pain in adulthood; therefore, we conducted no mediation analyses for this relationship.

Childhood Abuse, Health Risk Behaviors, and Mental Health Problems

Illustrating the second step in our mediation analysis, Table 2 shows that rates of health risk behaviors (with the exception of low exercise) were higher among respondents who reported childhood abuse than among those who did not. The rates of adequate exercise as defined in this study were generally low, consistent with rates reported in the United States.34 These differences were statistically significant, with the exception of the relationships between childhood physical and sexual abuse and low exercise and between childhood physical abuse and obesity. For example, respondents who reported childhood physical abuse were 1.42 times more likely to smoke than were respondents who did not report abuse. We also found a strong relationship between childhood abuse and a lifetime history of mental health problems, similar to results that MacMillan et al. obtained when studying OHS data.35

TABLE 2.

Relationship of Childhood Physical and Sexual Abuse With Adult Health Risk Behaviors and Mental Health Problems: Ontario Health Survey Mental Health Supplement, 1990–1991

| Without Abuse, Weighted No. (%) | With Abuse, Weighted No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Relationship between childhood physical abuse and | |||

| Smoking | 1267 (26.2) | 582 (34.0) | 1.42* (1.19, 1.71) |

| Alcohol problems | 607 (10.2) | 410 (19.3) | 1.87* (1.52, 2.31) |

| Low exercise | 3263 (70.0) | 1163 (70.6) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.26) |

| Obesity | 567 (12.5) | 245 (15.0) | 1.18 (0.92, 1.51) |

| More than 1 sexual partner | 324 (7.4) | 148 (9.4) | 1.49* (1.06, 2.09) |

| Mental health problems | 1360 (22.7) | 735 (34.7) | 2.04* (1.73, 2.41) |

| Relationship between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Smoking | 1638 (27.8) | 217 (35.7) | 1.52* (1.16, 1.99) |

| Alcohol problems | 890 (12.1) | 117 (16.2) | 2.44* (1.74, 3.44) |

| Low exercise | 3965 (69.7) | 431 (73.3) | 0.99 (0.74, 1.33) |

| Obesity | 687 (12.3) | 106 (18.2) | 1.61* (1.14, 2.27) |

| More than 1 sexual partner | 411 (7.6) | 64 (11.5) | 2.34* (1.44, 3.80) |

| Mental health problems | 1768 (24.1) | 323 (44.4) | 2.26* (1.78, 2.87) |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. The ORs are for the relationship between childhood abuse and health risk behaviors or mental health problems. Covariates included age, gender, low education, and marital status.

P ≤ .05.

Health Risk Behaviors and Mental Health Problems as Mediators

Tables 3 and 4 show the final step in testing the mediating effects of health risk behaviors and mental health problems for the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health and health care utilization. The ORs for the relationship between childhood abuse and health were compared when the potential mediator was not included in the model (simple model) and again when it was included (mediated model). To illustrate with an example, Table 4 shows that respondents with childhood physical abuse were 1.44 times more likely to report multiple health problems than were respondents with no childhood physical abuse. In the mediated model, when all health risk behaviors and mental health problems are added, the OR decreases from 1.44 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.18, 1.75) to 1.22 (95% CI = 0.99, 1.50), a 50% reduction.

TABLE 3.

Logistic Regression Models for Health Risk Behaviors as Mediators Between Childhood Abuse and Adult Health Problems and Health Care Utilization: Ontario Health Survey Mental Health Supplement, 1990–1991

| Predictor and Outcome Variables | Simple Model,a OR (95 %CI) | Mediated Model,b OR (95% CI) | % Changec |

| Smoking as mediator between childhood physical abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.43 (1.17, 1.74) | 1.39 (1.14, 1.70) | −9 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.36 (0.99, 1.88) | 1.33 (0.96, 1.83) | −8 |

| Pain | 1.90 (1.42, 2.54) | 1.84 (1.38, 2.47) | −7 |

| Disability | 1.83 (1.45, 2.32) | 1.82 (1.43, 2.30) | −1 |

| High emergency department use | 1.94 (1.46, 2.58) | 1.89 (1.42, 2.52) | −5 |

| High health professional use | 1.60 (1.25, 2.04) | 1.59 (1.24, 2.04) | −2 |

| Smoking as mediator between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.81 (1.38, 2.37) | 1.76 (1.34, 2.32) | −6 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.75 (1.14, 2.38) | 1.68 (1.09, 2.59) | −9 |

| Disability | 1.70 (1.21, 2.38) | 1.69 (1.20, 2.38) | −1 |

| High emergency department use | 1.93 (1.28, 2.92) | 1.85 (1.22, 2.80) | −9 |

| High health professional use | 1.74 (1.25, 2.42) | 1.73 (1.24, 2.41) | −1 |

| Alcohol abuse as mediator between childhood physical abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.45 (1.19, 1.76) | 1.39 (1.14, 1.69) | −13 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.34 (0.97, 1.84) | 1.27 (0.92, 1.77) | −21 |

| Pain | 1.91 (1.43, 2.55) | 1.93 (1.44, 2.58) | +2 |

| Disability | 1.82 (1.44, 2.30) | 1.73 (1.37, 2.20) | −11 |

| High emergency department use | 1.95 (1.47, 2.60) | 1.93 (1.45, 2.56) | −2 |

| High health professional use | 1.60 (1.25, 2.05) | 1.57 (1.23, 2.01) | −5 |

| Alcohol abuse as mediator between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.81 (1.38, 2.38) | 1.73 (1.32, 2.28) | −10 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.69 (1.10, 2.60) | 1.61 (1.04, 2.48) | −12 |

| Disability | 1.65 (1.18, 2.33) | 1.56 (1.11, 2.20) | −14 |

| High emergency department use | 1.95 (1.29, 2.94) | 1.90 (1.25, 2.87) | −5 |

| High health professional use | 1.74 (1.25, 2.42) | 1.71 (1.22, 2.38) | −4 |

| Obesity as mediator between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.81 (1.38, 2.37) | 1.75 (1.33, 2.31) | −7 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.69 (1.14, 2.69) | 1.63 (1.06, 2.54) | −9 |

| Disability | 1.65 (1.21, 2.38) | 1.65 (1.17, 2.32) | −7 |

| High emergency department use | 1.95 (1.28, 2.92) | 1.91 (1.27, 2.89) | −4 |

| High health professional use | 1.74 (1.25, 2.42) | 1.73 (1.24, 2.41) | −1 |

| More than 1 sexual partner as mediator between childhood physical abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.43 (1.17, 1.74) | 1.41 (1.16, 1.72) | −5 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.36 (0.99, 1.88) | 1.37 (0.99, 1.89) | +3 |

| Pain | 1.90 (1.42, 2.54) | 1.89 (1.42, 2.53) | −1 |

| Disability | 1.83 (1.45, 2.32) | 1.83 (1.44, 2.31) | 0 |

| High emergency department use | 1.94 (1.46, 2.58) | 1.93 (1.45, 2.56) | −1 |

| High health professional use | 1.60 (1.25, 2.04) | 1.58 (1.23, 2.02) | −3 |

| More than 1 sexual partner as mediator between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.81 (1.38, 2.37) | 1.77 (1.35, 2.33) | −5 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.75 (1.14, 2.69) | 1.76 (1.14, 2.71) | +1 |

| Disability | 1.70 (1.21, 2.38) | 1.69 (1.20, 2.38) | −1 |

| High emergency department use | 1.93 (1.28, 2.92) | 1.90 (1.25, 2.87) | −3 |

| High health professional use | 1.73 (1.24, 2.42) | 1.68 (1.20, 2.34) | −7 |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. The ORs are for the relationship between childhood abuse and health risk behaviors or mental health problems.

The simple model includes childhood abuse as the predictor variable and health indicators as the outcome variable. Age, gender, low education, and marital status are covariates.

The mediated model includes health risk behaviors as the mediator variable, childhood abuse as the predictor variable, and health indicators as the outcome variable. Age, gender, low education, and marital status are covariates.

To calculate how much the the OR for abuse was attenuated when the mediator variable was added, we used the following formula: (OR [simple model] – OR [mediated model] / OR [simple model] – 1) × 100%.

TABLE 4.

Logistic Regression Models for Health Risk Behaviors and Mental Health Problems as Mediators Between Childhood Abuse and Adult Health Problems and Health Care Utilization: Ontario Health Survey, Mental Health Supplement, 1990–1991

| Predictor and Outcome Variables | Simple Model,a OR (95% CI) | Mediated Model,b OR (95% CI) | % Changec |

| At least 1 mental health problem in lifetime as mediator between childhood physical abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.43 (1.17, 1.74) | 1.29 (1.05, 1.57) | −33 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.37 (0.99, 1.89) | 1.23 (0.88, 1.70) | −38 |

| Pain | 1.91 (1.43, 2.55) | 1.70 (1.27, 2.28) | −23 |

| Disability | 1.83 (1.45, 2.31) | 1.69 (1.33, 2.15) | −17 |

| High emergency department use | 1.94 (1.47, 2.58) | 1.83 (1.37, 2.44) | −12 |

| High health professional use | 1.60 (1.25, 2.05) | 1.48 (1.15, 1.90) | −20 |

| At least 1 mental health problem in lifetime as mediator between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.81 (1.38, 2.37) | 1.59 (1.20, 2.10) | −27 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.75 (1.14, 2.69) | 1.48 (0.95, 2.30) | −36 |

| Disability | 1.70 (1.21, 2.38) | 1.50 (1.06, 2.12) | −29 |

| High emergency department use | 1.93 (1.27, 2.92) | 1.77 (1.17, 2.69) | −17 |

| High health professional use | 1.74 (1.25, 2.42) | 1.58 (1.13, 2.21) | −22 |

| Mental health problems and all health risk behaviors as mediators between childhood physical abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.44 (1.18, 1.75) | 1.22 (0.99, 1.50) | −50 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.37 (0.99, 1.90) | 1.16 (0.83, 1.63) | −57 |

| Pain | 1.92 (1.43, 2.56) | 1.69 (1.25, 2.28) | −25 |

| Disability | 1.81 (1.43, 2.29) | 1.61 (1.26, 2.05) | −25 |

| High emergency department use | 1.95 (1.47, 2.59) | 1.78 (1.33, 2.38) | −18 |

| High health professional use | 1.60 (1.25, 2.05) | 1.45 (1.13, 1.87) | −25 |

| Mental health problems and all health risk behaviors as mediators between childhood sexual abuse and | |||

| Multiple health problems | 1.82 (1.38, 2.39) | 1.48 (1.12, 1.97) | −41 |

| Poor self-rated health | 1.72 (1.11, 2.65) | 1.30 (0.83, 2.05) | −58 |

| Disability | 1.65 (1.17, 2.32) | 1.39 (0.97, 1.97) | −42 |

| High emergency department use | 1.93 (1.28, 2.92) | 1.69 (1.11, 2.59) | −26 |

| High health professional use | 1.73 (1.24, 2.42) | 1.52 (1.08, 2.14) | −29 |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. The ORs are for the relationship between childhood abuse and health risk behaviors or mental health problems.

The simple model includes childhood abuse as the predictor variable and health indicators as the outcome variable. Age, gender, low education, and marital status are covariates.

The mediated model includes health risk behaviors as the mediator variable, childhood abuse as the predictor variable and health indicators as the outcome variable. Age, gender, low education, and marital status are covariates.

To calculate how much the the OR for abuse was attenuated when the mediator variable was added, we used the following formula: (OR [simple model] – OR [mediated model] / OR [simple model] – 1) × 100%.

Individually, OR reductions for health risk behaviors (ranging from no reduction to a 21% reduction) were modest, suggesting the partial mediating effects of health risk behaviors in the relationship between childhood abuse and adult physical health. These effects appear to be strongest for alcohol abuse and negligible for having more than 1 sexual partner in the previous year. Mental health problems appear to be a strong mediator between childhood abuse and physical health indicators, because all of the ORs for this relationship decreased significantly when mental health problems were entered in the model (12% to 38%). These mediation effects appear to be stronger for health indicators than for health care utilization indicators. The analyses shown in the second part of Table 4 suggest that, taken together, all the health risk behaviors and mental health problems examined in this study strongly mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and adult physical health (reductions of 18% to 58%). The mediation effects of all the factors combined are stronger than the individual effects of the health risk behaviors or mental health problems.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study of the relationship between childhood abuse and health risk behaviors. We found relationships of moderate strength between childhood physical abuse and smoking, alcohol problems, and having more than 1 sexual partner in the previous year. The relationships between childhood sexual abuse and smoking, alcohol problems, obesity, and having more than 1 sexual partner in the previous year appeared to be somewhat stronger. These relationships are important, because although health risk behaviors may have a limited influence on current health (especially for young people), they often have a dramatic effect on health over the long term.

A number of studies have reported that individuals with childhood abuse more frequently engage in health risk behaviors, results that are consistent with our findings. Nelson et al. found that students who had experienced sexual abuse were about 3 times more likely to smoke and 2 times more likely to have used alcohol than were students with no sexual abuse.36 Bensley et al. reported that the OR for the relationship between childhood physical abuse and heavy drinking was 3.2 for men and not significant for women and that the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and heavy drinking was significant for males (OR = 2.0) and not significant for females.18 The marked differences between Bensley's study and the present study with regard to ORs for females may be caused by the low number of females in Bensley's sample who reported heavy drinking, which could have made Bensley's estimate less reliable. Young and Katz did not calculate ORs, but their prevalence tables indicated that women who had experienced sexual abuse were about 3 times more likely to have multiple sexual partners than were women who had not experienced sexual abuse, which is similar to the OR of 2.9 that we found in our study.21

In our study, smoking, alcohol problems, and obesity were partial mediators of the relationship between childhood abuse and health indicators. Reduction in the strength of the abuse–health relationship ranged from negligible to 21% when the model was adjusted for these health risk behaviors. Our finding of partial mediation as opposed to complete mediation indicates that these important health risk behaviors are not the sole mechanisms linking childhood abuse and adult health.

Evidence from our study supports the hypothesis that having a history of mental health problems strongly mediates the relationship between childhood abuse and adult physical health. All ORs were attenuated when mental health problems were entered into the model. The relationship between childhood abuse and mental health problems has been observed in numerous studies.37–39 Our findings are also consistent with previous research on the relationship between mental health and physical health. Anxiety and depression in young people are associated with higher levels of health risk behaviors (e.g., smoking, excessive alcohol use, excessive use of street drugs, and reduced level of physical activity). A New Zealand study found that girls who had an anxiety disorder at age 15 had more medical problems at age 21 than did girls who did not have an anxiety disorder at age 15.40 Mental health problems may exacerbate chronic health conditions through a number of mechanisms, including decreased adherence to treatment recommendations, suppressed immune system functioning, and increased autonomic nervous system or hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity.41

Few previous studies have explored whether health risk behaviors and mental health problems might be mediators of the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health. Using the ACE data, Dong et al. found that the risk of liver disease increased with each adverse childhood experience reported.26 When health risk behaviors such as alcohol consumption and sexual promiscuity were added to the model, the strength of the association between liver disease and adverse childhood experiences was reduced by 38% to 50%. In a similar study, Dong et al. found that health risk behaviors and depression mediated the relationship between childhood adversities and ischemic heart disease (50% to 100% reduction).25 We found that ORs decreased by up to 58% when these factors were included in the model.

Given that changing health habits is difficult, it is important to understand how unhealthful habits are developed and maintained.42 In explaining the relationship between childhood abuse and smoking, Anda et al. suggest that smokers use nicotine's psychoactive effects to cope with negative emotional, neurobiological, and social effects of adverse experiences.43 They also note that individuals with adverse childhood experiences suffer from problems with affect, socialization, and self-esteem. These problems may increase their susceptibility to peer pressure and tobacco marketing. McKay found that negative emotional states, cravings, cognitive factors, interpersonal problems, and lack of coping effort prior to relapse played a role in relapse to use of alcohol, drugs, and nicotine.44

Childhood abuse is the third most common public health concern for children (following asthma and allergies).45 A recent report from the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect indicates that the number of reported child abuse cases (except for child sexual abuse) has increased.46 An estimated 217 319 child investigations were conducted in Canada during 2003 (excluding the province of Quebec), and nearly half of these cases were substantiated, resulting in an incident rate of 21.71 cases of maltreatment per 1000 children. Prevalence rates of child abuse from retrospective studies indicate that reported cases represent a small proportion of the actual number of children experiencing abuse. Fergusson et al. examined data from the Christchurch Health and Development Study and found that 17.3% of girls and 3.4% of boys reported experiencing childhood sexual abuse before the age of 16.47

Our results suggest that population health strategies aimed at decreasing child maltreatment are crucial to improving long-term health outcomes. Strategies can include a continuum of supports for families such as improving early childhood learning, home visiting, and parenting programs. As an example, the Positive Parenting Program has been shown to reduce coercive and inconsistent parenting practices.48 Efforts could be targeted to populations with increased risk of abuse and other factors (e.g., economic disadvantage) that predispose them to mental health problems or to developing poor health habits. Targeting high-risk families with infants for a nurse home-visitation intervention has been shown to be effective in decreasing health risk behaviors when these infants reach adolescence.49 A recent Canadian study found that universal screening at birth for risk factors associated with child abuse was effective in identifying children who required future services from child protection agencies. This screening process served to direct families to appropriate resources such as child care, parenting programs, financial assistance, and home visitation programs.50

Strengths and Limitations

The cross-sectional design of this study and of many large community surveys limits the conclusions that can be made about the causal nature of associations. Although longitudinal designs have advantages in clarifying temporal and causal relationships, few examples of longitudinal designs exist in child-abuse research. Practical and ethical barriers have limited the study of children who have experienced abuse. Another limitation is that the OHS did not include items assessing childhood neglect or psychological abuse, which have also been linked to adult health.3,6

Strengths of the OHS are its extensive evaluations of abuse and health. Broad dimensions of health were explored, rather than specific medical conditions found in previous research. Clear, specific questions based on abridged versions of well-known instruments were used to assess childhood abuse. Studies using retrospective reports of abuse have been criticized because of concerns about recall bias, but to put these concerns into perspective, Hardt and Rutter concluded in their review that retrospective reports are sufficiently valid to be used for research purposes.51 They also found that underreporting of childhood abuse, which would attenuate the relationship between childhood abuse and health risk behaviors, is more common than overreporting.

A few comments should be made regarding interpretation of our results. To evaluate mediation, we made 2 assumptions: (1) abuse preceded health risk behaviors and mental health problems and (2) all of the previous factors preceded the current health indicator. However, the study's cross-sectional design prevented us from evaluating the temporal relationships among these variables. Although we acknowledge that this order of events may not be true for a minority of respondents, we believe that our assumptions regarding the temporal relationships among these variables is realistic. The analyses in this study can determine that a relationship is consistent with what we might expect if there were a mediating relationship, but they cannot establish causality.

Although we used appropriate methods to adjust for missing data, differences between respondents with and without missing data could have influenced our results. Younger single men with lower education were overrepresented among those who did not return the questionnaire. Sensitivity analyses (not shown) suggest that mediation effects are stronger among younger respondents but weaker among male respondents.

Conclusions

Our results support the hypotheses that childhood abuse is associated with higher rates of health risk behaviors and mental health problems and that these factors partially mediate the relationship between childhood abuse and adult health. These results should be considered when developing public health strategies to improve long-term health. Interventions that support families with young children have shown important gains in decreasing child abuse, decreasing the development of health risk behaviors and mental health problems in children, and improving the well-being of parents.48,52–55

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by a Canadian Institute of Health Research scholarship.

The authors are grateful to Elizabeth Lin, Robert Murray, and Robert Tate for their thoughtful review of earlier versions of this article.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study.

References

- 1.Chartier MJ, Walker JR, Naimark B. Childhood abuse, adult health and health care utilization: results from a representative community sample. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1031–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis DA, Luecken LJ, Zautra AJ. Are reports of childhood abuse related to the experience of chronic pain in adulthood? A meta-analytic review of the literature. Clin J Pain 2005;21:398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction of many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14:245–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sachs-Ericsson N, Blazer D, Plant EA, Arnow B. Childhood sexual and physical abuse and the one-year prevalence of medical problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. Health Psychol 2005;24:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson MP, Aria I, Basile KC, Desai S. The association between childhood physical and sexual victimization and health problems in adulthood in a nationally representative sample of women. J Interpers Violence 2002;17:1115–1129 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walker EA, Gelfand A, Katon WJ, et al. Adult health status of women with histories of childhood abuse and neglect. Am J Med 1999;107:332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Newman MG, Clayton L, Zuellig A, et al. The relationship of childhood sexual abuse and depression with somatic symptoms and medical utilization. Psychol Med 2000;30:1063–1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finestone HM, Stenn P, Davies F, Stalker C, Fry R, Koumanis J. Chronic pain and health care utilization in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:547–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker EA, Unutzer J, Rutter C, et al. Costs of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:609–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glaser D. Child abuse and neglect and the brain: a review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000;41:97–116 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunnar MR. Integrating neuroscience and psychological approaches in the study of early experiences. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003;1008:238–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEwen BS, Seeman T. Protective and damaging effects of mediators of stress: elaborating and testing the concepts of allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:30–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sapolsky RM. Social subordinance as a marker of hypercortisolism: some unexpected subtleties. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1996:626–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuh D, Power C, Blane D, Bartley M. Social pathways between childhood and adult health. In: Kuh D, Ben-Shlomo Y, eds A Life Course Approach to Chronic Disease Epidemiology New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1997:169–199 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bensley LS, Van Eenwyk J, Simmons KW. Self-reported childhood sexual and physical abuse and adult HIV-risk behaviors and heavy drinking. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards VJ, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Dube SR. Adverse childhood experiences and health-related quality of life as an adult. In: Kendall-Tackett KA, eds Health Consequences of Abuse in the Family: A Clinical Guide for Evidence-Based Practice Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004:81–94 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mullings JL, Marquart JW, Brewer VE. Assessing the relationship between child sexual abuse and marginal living conditions on HIV/AIDS-related risk behavior among women prisoners. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:677–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young TK, Katz A. Survivors of sexual abuse: clinical, lifestyle and reproductive consequences. CMAJ 1998;159:329–334 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1995;34:541–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan SJ, Pelcovitz D, Labruna V. Child and adolescent abuse and neglect research: a review of the past 10 years. Part I: physical and emotional abuse and neglect. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:1214–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutter ML. Psychosocial adversity and child psychopathology. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:480–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, Mast EE, Giovino GA, Remington P. Depression and the dynamics of smoking. JAMA 1990;264:1541–1545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeWit DJ, MacDonald K, Offord DR. Childhood stress and symptoms of drug dependence in adolescence and early adulthood. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1999;69:61–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hazell P. Does the treatment of mental disorders in childhood lead to healthier adulthood? Curr Opin Psychiatry 2007;20(4):315–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong M, Giles WH, Felitti VJ, et al. Insights into causal pathways for ischemic heart disease. Circulation 2004;110:1761–1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong M, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Giles WH, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and self-reported liver disease: new insights into causal pathways. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1949–1956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyle MH, Offord DR, Campbell D, et al. Mental health supplement to the Ontario Health Survey: methodology. Can J Psychiatry 1996;41:549–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straus MA. The Conflict Tactics Scales and its critics: an evaluation and new data on validity and reliability. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, eds Physical Violence in American Families New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers; 1990:49–73 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leserman J, Drossman DA. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med 1996;21:141–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ontario Ministry of Health Ontario Health Survey 1990: Mental Health Supplement Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Revised Third Edition Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analyses for Behavioral Sciences Hilldale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1983 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;51:1173–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE, Dsewltowski DA. Physical activity promotion through primary care. JAMA 2003;289:2913–2916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, et al. Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1878–1883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson DE, Higginson EK, Grant-Worley JA. Using the youth risk behavior survey to estimate prevalence of sexual abuse among Oregon high school students. J Sch Health 1994;64:413–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fergusson DM, Horwood J, Lynskey MT. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: II. Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;34:1365–1374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med 1997;27:1101–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widom CS. Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1223–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bardone AM, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Dickson N, Stanton WR, Silva PA. Adult physical health outcomes of adolescent girls with conduct disorder, depression, and anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37:594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Husain A, Triadafilopoutos G. Communicating with patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004;10:444–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis JL, Combs-Lane AM, Smith DW. Victimization and health risk behaviors: implications for prevention programs. In: Kendall-Tackett KA, eds Health Consequences of Abuse in the Family: A Clinical Guide for Evidence-Based Practice Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anda RF, Croft JB, Felitti VJ, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and adulthood. JAMA 1999;282(17):1652–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKay J. Studies of factors in relapse to alcohol, drug and nicotine use: a critical review of methodologies and findings. J Stud Alcohol 1999;60:566–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Palusci VJ. The role of health care professionals in the response to child victimization. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma 2003;8(1–2):133–171 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trocmé N, Fallon B, MacLaurin B, et al. Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect–Major Findings–2003. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.07.003. Ottawa, Ontario: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada; 2005. Available at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cm-vee/csca-ecve/pdf/childabuse_final_e.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT, Horwood LJ. Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric disorder in young adulthood: I. Prevalence of sexual abuse and factors associated with sexual abuse. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35(10):1355–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Turner KMT, Ralph A. Using Triple P System of Intervention to prevent behavioral problems in children and adolescents. In: Barrett PM, Ollendick TH. Handbook of Interventions that Work with Children and Adolescents: Treatment and Prevention Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 2004:489–451 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olds DL, Henderson CR, Cole R, et al. Long-term effects of nurse home visitation on children's criminal and antisocial behavior: 15-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280:1238–1244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brownell M, Santos R, Kozyrskyj A, et al. Next Steps in the Provincial Evaluation of the BabyFirst Program: Measuring Early Impacts on Outcomes Associated with Child Maltreatment. Available at: http://www.umanitoba.ca/centres/mchp/report.htm. Accessed January 14, 2008.

- 51.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of childhood experiences: review of the evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:260–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berrueta-Clement JR, Schweinhart LJ, Barnett WS, Epstein AS, Weikart DP. Changed Lives: The Effects of the Perry Preschool Program on Youths through Age 19 Ypsilanti, MI: High Scope Press; 1984. High/Scope Educational Research Foundation Monograph 8 [Google Scholar]

- 53.MacLeod J, Nelson G. Programs for the promotion of family wellness and the prevention of child maltreatment: a meta-analytic review. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:1127–1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olds DL, Eckenrode J, Henderson CR, et al. Long-term effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized trial. JAMA 1997;278:637–643 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Badgley CR. Report of the Committee on Sexual Offenses Against Children and Youths Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Government Publishing Centre; 1984 [Google Scholar]