Abstract

One of the hallmarks of drug addiction is a limitation of the temporal horizon of events that affect the behavior of drug users. The purpose of this experiment was to examine the time period over which smoking was influenced by an earlier opportunity to smoke. Baseline sessions measured how much was smoked in a current opportunity when it was preceded by a two-hour wait time in which no smoking was allowed. Following the baseline phase, we examined the effects of temporal distance when an earlier opportunity to smoke (upon completion of a FR100) preceded current smoking (upon completion of a PR). Temporal distance between these two opportunities to smoke was varied from 0 min to 120 min. We found that current smoking for the group was reduced from baseline levels when the temporal distance was 0 min. At temporal distances ranging from 30 min to 90 min, the individual's smoking returned to levels that were similar to baseline. Breakpoints were also a function of previous smoking, and latencies to first puff of the session followed a similar trend. These findings provide evidence of the limited temporal horizons related to smoking bouts of smokers and may provide a useful measure for metabolism differences across populations. In addition, we suggest that the quantitative description of satiety provided by our procedures may validate drug replacement therapies involved in cessation treatments.

Keywords: Smoking, Progressive Ratio schedule, Breakpoint, Temporal Horizons, Satiety, Regulation, human

Introduction

The term `temporal horizon' describes the window of time over which experiences in the past and the expectation of events in the future affect current behavior. One hallmark of addiction is the distinctive tendency of drug users to exhibit limited temporal horizons. For instance, heavy smokers tend to highly value immediately available cigarettes, while discounting the value of cigarettes available in the future at high rates (i.e., temporal discounting; e.g., Bickel et al., 1999). Similarly, over short time periods past smoking has a strong impact on current smoking; however, as time passes the effects of past smoking are quickly reduced (e.g., Griffiths & Henningfield, 1982; Zacny & Stitzer, 1985). Importantly, while previous studies do offer some guidance as to the broad limits (e.g., fewer than 300 minutes; Experiment 1, Zacny & Stitzer, 1985) of temporal horizons among smokers they do not help to determine the time point past which further increases in time cease having observable effects on an individual's smoking behavior. The current investigation sought to provide a more fine grained examination in order to define the time frame over which past smoking affects current smoking by quantifying individual smokers' temporal horizons.

Studies of temporal horizons in animals define the window of time over which the effects of past or future food reinforcers are integrated by manipulating the time between two feeding opportunities. For instance, Timberlake et al (1987) found that expectation of eating in the immediate future (i.e., after a 16-minute delay) reduced rats' current consumption of food; however, the availability of food further in the future (i.e., after a 32-minute delay) had no effect on current eating. Interestingly, in a related study, Timberlake (1984) observed that an initial consumption opportunity provided a short time (i.e., 1-8 hours) before the next feeding opportunity reduced rats' consumption of food in the second consumption opportunity. Conversely, Timberlake observed that when food in the first consumption opportunity was eaten more than 8 hours in the past, then it had no effect on eating in the second consumption opportunity. Thus, Timberlake's procedures suggest a straightforward approach to measure temporal horizon in individual smokers, by manipulating the time between two consumption opportunities and determining the window of time over which past consumption affects current consumption.

Several previous human studies have compared the effects of prior smoking on how much work smokers are willing to do in order to earn opportunities to smoke (e.g., Tidey et al., 1999; Rusted et al., 1998; Willner et al., 1995; Perkins et al, 1994; Epstein et al., 1991; c.f., Bickel et al., 1997). For instance, Tidey et al (1999) compared the number of smoking opportunities earned on progressive ratio (PR) schedules, in which participants completed a work requirement (pulling on a plunger) to earn cigarette puffs after 5-6 hours of not smoking, with the number of smoking opportunities earned after unrestricted smoking. The results of Tidey's study showed a decrease in the number of smoking opportunities earned following unrestricted smoking compared to the number of reinforcers (i.e., bouts of cigarette puffs) earned following 5-6 hours of not smoking. Importantly, a common thread among previous studies of human smoking behavior is the wide difference in prior smoking times between conditions (e.g., 0 hours vs. 5-6 hours in Tidey's study). These wide ranges in prior times do not allow for a fine grained definition of temporal horizon or for the identification of individual differences in temporal horizon among smokers.

In order to make the results of the current study comparable to previous results from studies of smokers and to those of Timberlake's studies with non-human animals, we elected to use a progressive ratio (PR) schedule and three common outcome measures of PR schedules (i.e., breakpoint, number of smoking reinforcers earned, and latency to the first cigarette puff of the session) as our primary dependent variables. To make the current results more interpretable in the context of Timberlake's temporal horizon studies we used fixed ratio (FR) access to smoking at a small price (FR 100) before each PR session to provide participants with their pre-session access to smoking.

The purpose of the current investigation was to measure temporal horizons of cigarette satiety in smokers. We measured the effect of prior smoking on current smoking by providing smokers with two opportunities to smoke, a satiation session (FR 100 for 1 hour) followed by an experimental session (PR for 1 hour), separated by a wait time which we manipulated. We hypothesized that when the two opportunities to smoke were separated by a minimal wait time, then smoking would be reduced in the experimental session due to previous smoking. Failure to find reductions in smoking would suggest that the satiation session failed to influence smoking. Finding a reduction in smoking would suggest that the satiation session decreased motivation to smoke in experimental sessions. We also hypothesized that when wait times were increased beyond a certain temporal threshold (i.e., each participant's temporal horizon) previous smoking would no longer reduce smoking in the experimental session. If smoking increases following an increase in wait time, then this would provide evidence of temporal horizons of cigarette satiety. Failure to find increases in smoking with increases in wait time would suggest that prior smoking, over the time frames examined in the current study, is not systematically related to current smoking.

Method

Participants

Seven nicotine dependent smokers with no self-reported plans to quit in the next year voluntarily participated. Participants were required to be at least 18 years of age, smoke at least 20 cigarettes a day (verified with a carbon monoxide [CO] breath level of 15 parts per million or greater; measured with a handheld monitor, Bedfont Scientific Ltd, Kent England), score at least five on the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ), a test of nicotine dependence (Fagerström & Schneider, 1989), and meet DSM-IV criteria for dependence on cigarettes (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Table 1 presents individual values for these participant characteristics. Participants gave their written informed consent before beginning the study, which was approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Participant |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Avg. |

| Age | 50 | 51 | 51 | 25 | 42 | 40 | 43 | 43.14 |

| EDU | 12 | 17 | 14.5 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 13.21 |

| FTQ | 8 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 7.43 |

| DSM | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 4.14 |

| CPD | 25 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 26.71 |

| CO | 23 | 29 | 37 | 18 | 54 | 40 | 17 | 31.14 |

Key: EDU = years of education, FTQ = Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire score, DSM = number of criteria reached on DSM-IV for cigarettes, CPD = Self-reported number of cigarettes smoked per day, CO = Carbon Monoxide breath level collected following consent.

***** please replace `avg' with `mean' *********

A screening interview, which was conducted following informed consent, was used to ensure that participants did not have a current history of drug abuse or psychological problems that could have interfered with the study. For instance, questions related to psychological problems probed for bipolar disorder and symptoms of psychosis. Participants were compensated $7.50 per hour plus an additional $7.50 per hour as a bonus upon completion of the study. The bonus money was delivered at the end of the study and all other payments were given immediately following the completion of each visit.

Apparatus

Sessions were conducted in a small room equipped with its own ventilation system. A PC running visual basic software (Rayfield Equipment, Waitsfield, Vermont) controlled and obtained data from a response console (approx. 60 cm × 30 cm × 45) that contained three Lindsey plungers (Med Associates Inc., Georgia, Vermont), which required approximately 20 N of force to produce a response. Also instrumented to the computer was a pressure sensor (Rayfield Equipment) that was used to measure puff volume. Approximately 3-feet of plastic tubing were used to connect the breath sensor to a restricted cigarette holder. Changes in pressure, caused by puffing, were detected by the pressure sensor and then processed by an A-D card (PCI - DAS08 using InstaCal software, Measurement Computing Corp., Norton, Massachusetts) within the computer. The computer integrated flow rates over the duration of the puff to provide the puff volume measure. Located on top of the response console was a 16” computer monitor, which monitor displayed the time left in the session and feedback information concerning puff volumes. Participants' preferred brand of cigarettes was provided by the experimenter. A daily newspaper, magazines, and a radio were available for the participant during the session.

Pre-session Procedures

Each participant began his or her own session at approximately the same time each day. Participants were instructed to refrain from smoking for 5 to 6 hours before each visit. In the beginning of each visit, CO levels had to be less than or equal to 50% of the initial CO level (i.e., the CO measured obtained at the beginning of the study). When participants failed to reach desired CO levels, the session was rescheduled. We have previously demonstrated that abstinence procedure occasions responding for cigarette puffs (see Madden & Bickel, 1999).

Reinforcer Administrations

When a fixed-ratio work requirement was completed, the participant smoked two standardized puffs. A new cigarette was provided for each bout of puffs to avoid the difficulty of rod filtration producing greater nicotine doses in the last vs. first puffs. A uniform smoke delivery procedure, established and validated by Zacny et al (1987), was used. A computer-based monitoring system measured puff volume in real-time and generated feedback. The importance of this procedure was that 1) consistent quantities of smoke can be reliably administered (i.e., a puff volume of approximately 70 ml and a breath hold of 5 seconds); 2) this can be accomplished in a safe and efficient manner; and, 3) smoking approximates naturalistic smoking to a greater extent than other delivery systems (Pomerleau et al., 1989).

Each bout of puffing (i.e., 2 puffs) occurred during a 120-s time during which the participant smoked through the holder, according to computer-generated signals. The computer signaled the start of the puff with the message “begin puffing.” Once the puff volume of 70 ml of smoke was reached, the message, “hold smoke in” indicated to the participant that they should stop inhaling and start breath holding. The third message, 5 s later, indicated to the participant that they should “exhale”. Thirty seconds after each puff the next puff was delivered. After the last puff, a variable length inter-trial interval (ITI) was introduced to maintain a total delivery time of 120-s for the bout of two puffs.

Experimental Design

The purpose was to determine the effect of previous smoking that occurred in satiation sessions on smoking during experimental sessions. The design consisted of three phases; an initial baseline phase, a systematic manipulation phase, and a recovery of baseline phase. During both baseline phases each visit consisted of two components: a wait time (always 2 hours) followed by a single experimental session. Importantly, during the systematic manipulation phase participants only attended 1 visit per day and each visit consisted of three components: a satiation session, a wait time, and an experimental session.

As described above, the initial baseline phase required visits that consisted solely of a wait time and an experimental session, to determine levels of smoking during experimental sessions that were not preceded by satiation sessions. At the beginning of each visit during the initial baseline phase, participants had a 2-hour wait time before engaging in an experimental session. Experimental sessions consisted of a 1-hour opportunity to earn cigarette puffs. The cost (i.e., number of plunger pulls necessary to earn 2 puffs) was increased following completion of each response requirement (i.e., PR plunger pulls for 2 puffs; the FR requirement was incremented in the following series: FR 2, FR 20, FR 40, FR 66, FR 200, FR 400, FR 666, FR 1200, FR 2000, FR 4000, FR 6666). The number of cigarette puffs earned during the initial baseline phase was operationally defined as the initial baseline level of smoking during experimental sessions.

Following the initial baseline phase, participants began the systematic manipulation phase during which each visit to the lab consisted of two sessions separated by a variable wait time. The first session was a satiation session, in which puffs on a cigarette could be earned at a minimal cost (i.e., FR 100 plunger pulls for 2 puffs). The second session was an experimental session, in which the cost was increased following the completion of each response requirement (i.e., PR plunger pulls for 2 puffs, as described above). The wait time between the satiation session and the experimental session was always 0 min for the first visit of this phase. If the level of smoking during this experimental session was lower than the initial baseline level of smoking during experimental sessions, then the wait time was increased by 30 minutes (e.g., from 0 min to 30 min) during the next visit. For each successive visit, wait times increased by an additional 30 min (e.g., 30 min to 60 min, 60 min to 90 min, etc.) if levels of smoking during experimental sessions continued to be lower than the initial baseline level of smoking. Participation in this phase of the experiment was completed when smoking during experimental sessions: 1) reached the initial baseline level of smoking during experimental sessions, 2) did not increase across three consecutive increases in wait time, 3) or decreased following an increase in wait time.

The final phase of the study was the recovery of baseline phase. Participant visits during the recovery of baseline phase were procedurally that same as those in the initial baseline phase; consisting of a 2-hour wait time followed by an experimental session. Participants also engaged in other experimental manipulations that are not reported here. The number of reinforcers (i.e., 2 puffs each reinforcer) earned during each experimental session was the primary dependent variable (c.f., Tidey et al., 1999). We also measured breakpoints (i.e., the final completed fixed ratio in a progressive ratio sequence; see Tidey et al., 1999) during experimental sessions and latency to the first puff of each experimental session (see Griffiths & Henningfield, 1982).

Results

Baseline Results

A paired t-test of smoking (i.e., number of reinforcers) in initial baseline and baseline recovery experimental sessions (baseline mean = 7.29, SD = 1.70 and recovery of baseline mean = 6.86, SD = 1.68) indicated that the difference in means was not statistically significant (t [6] = 1.44, NS). Mean values from the dependent variables collected in baseline and baseline recovery sessions were used for subsequent comparisons.

Individual Participant Results: Maximum Recovery of Baseline

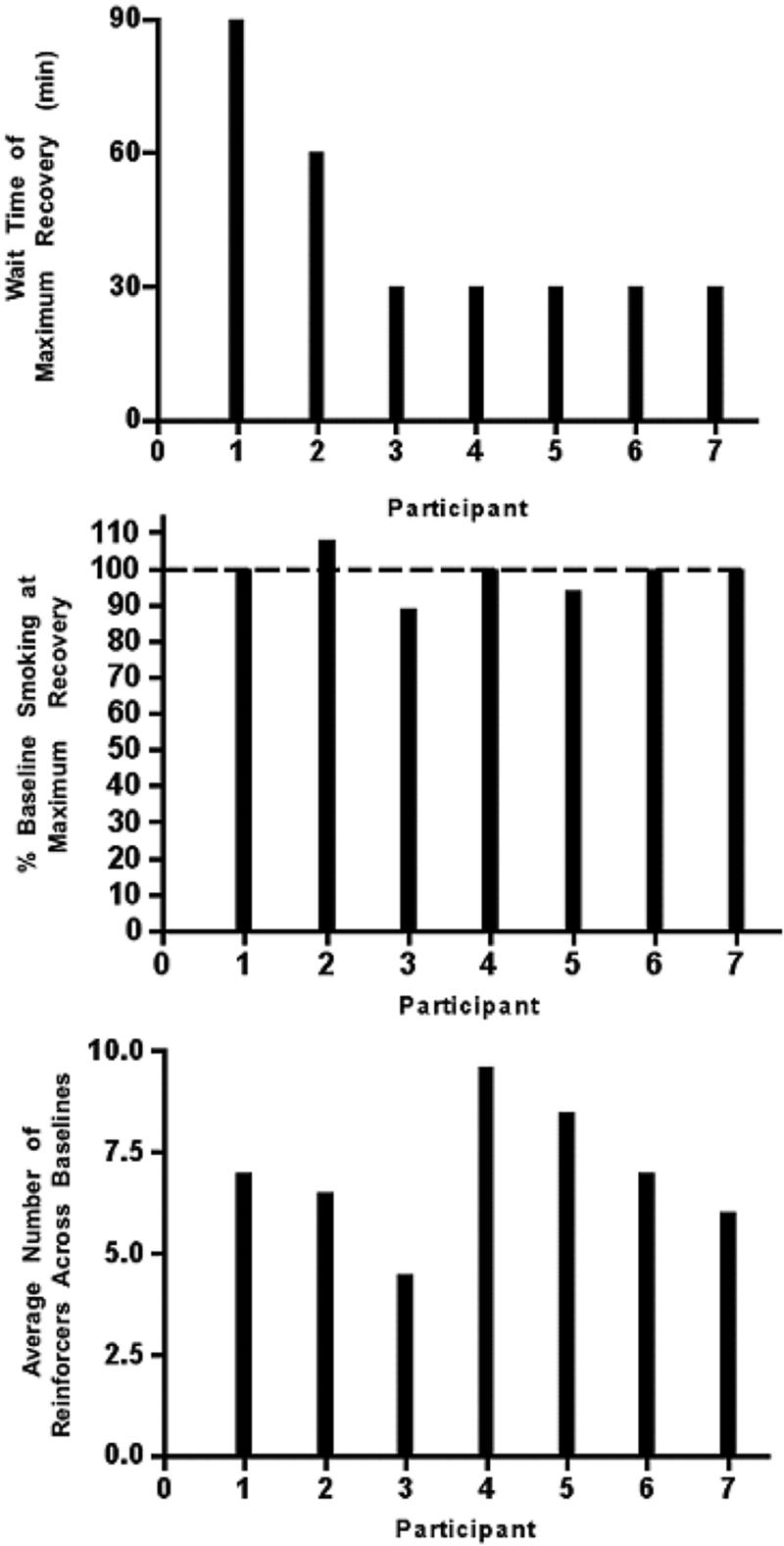

First, we investigated the duration of time between the end of a satiation session and the beginning of the experimental session (i.e. wait time) that produced the amount of smoking that was the most similar to baseline levels (i.e., maximum recovery of baseline). The top panel of Figure 1 presents the wait time that occasioned the maximum recovery of baseline levels of smoking for each individual participant.

Figure 1.

The top panel presents the wait time, in minutes, associated with the maximum recovery of baseline for individual participants. The middle panel presents the percentage of baseline smoking associated with the session when individual participants reached their maximum recovery of baseline. The dotted line indicates 100% recovery of baseline. The bottom panel presents the average number of opportunities to smoke earned during baseline and recovery of baseline experimental sessions for individual participants.

Smoking during experimental sessions was greatest for five of the seven participants when a 30-minute wait time was presented between the end of the satiation session and the beginning of an experimental session. Two participants (i.e., participant 1 and participant 2) exhibited the greatest amount of smoking when wait times were 90 and 60 minutes (respectively).

Next, we investigated whether individual participants smoked similarly during baseline sessions and during maximum recovery of baseline sessions (i.e., earned a similar number of reinforcers). The middle panel of Figure 1 presents the percentage of baseline smoking that occurred during the sessions associated with maximum recovery of baseline smoking (i.e., [maximum recovery of baseline smoking/baseline smoking] * 100) for individual participants. For this figure, 100% would indicate that baseline and maximum recovery sessions produced equivalent levels of smoking, less than 100% would indicate a reduction from baseline smoking, and greater than 100% would indicate an increase from baseline smoking. This figure shows that smoking was very similar to baseline levels across individual participants.

In addition, we investigated how much individual participants smoked during baseline sessions (i.e.,. the number of reinforcers earned). The bottom panel of Figure 1 presents the average number of reinforcers earned during baseline sessions for each individual participant. For this panel of Figure 1, 6 reinforcers would be equivalent to 12 cigarette puffs. Comparison of the top and bottom panel of this figure shows that, across individuals, smoking levels during the baseline sessions (bottom panel) did not appear to be related to the duration of wait times associated with maximum recovery.

Change from Baseline: Smoking

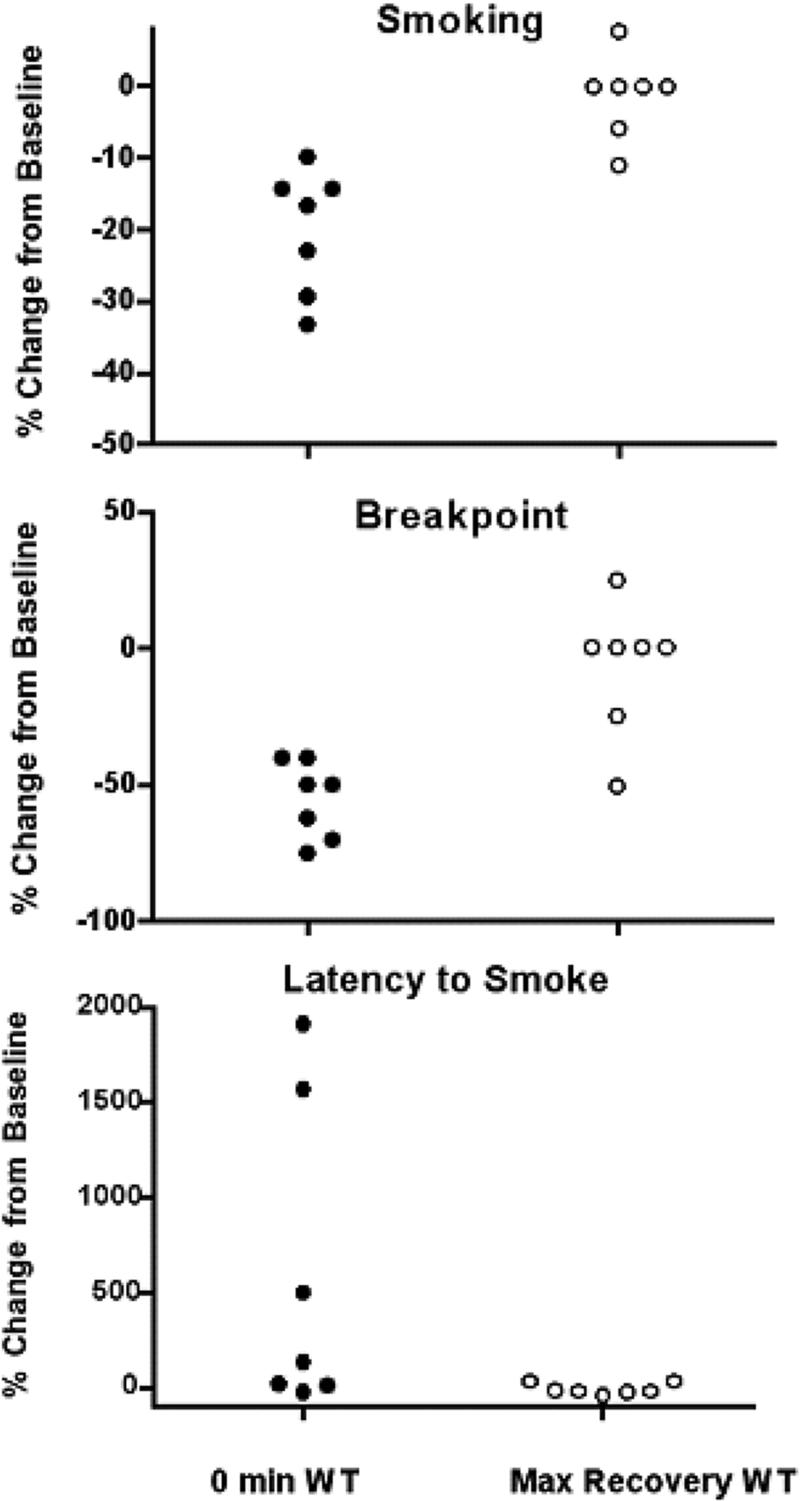

We next investigated the change from baseline smoking for sessions with a minimal wait time (0 min) and with the wait time associated with each individual participant's maximum recovery of baseline. Figure 2 (top panel) presents the percentage change from baseline smoking for individual participants. Importantly, for this figure: zero percentage change means the amounts of smoking were identical in baseline sessions, a negative percentage change means smoking was reduced compared to baseline levels, and a positive percentage change means smoking was increased compared to baseline levels. Visual inspection of the top panel of Figure 2 suggests smoking levels were reduced during the 0 min wait time experimental sessions. Smoking reached levels that appeared to be similar to baseline levels (i.e., percentage change approached zero) with wait times that produced the maximum recovery of baseline.

Figure 2.

The average percentage change from baseline smoking for individual participants (vertical axes) during sessions associated with zero minute wait times and during the sessions associated with maximum recovery of baseline (horizontal axes). The top panel presents data for smoking (i.e., number of opportunities to smoke that were earned during each session). The middle panel presents data for breakpoints. The bottom panel presents data for latency to smoke (i.e., the time from the beginning of an experimental session to the first puff).

On average, participants made 1.42 [CI: 0.87 - 1.97] fewer self-administrations at the 0 min wait time experimental session than for baseline. Defining equivalence as being within 90% to 111% of baseline levels, the mean number of self-administrations at maximum recovery sessions was equivalent to baseline levels (see Berger and Hsu, 1996). Baseline and maximum recovery means were 7.13 and 6.97, respectively. With 95% confidence, the maximum recovery mean was between 0.45 more and 0.19 fewer self-administrations of 90% and 111% of the baseline mean, respectively.

Change from Baseline: Breakpoint

We next investigated the change from baseline breakpoints for sessions with a minimal wait time (0 min) and with the wait time associated with each individual participant's maximum recovery of baseline (as described above). Figure 2 (middle panel) presents the average percentage change from baseline breakpoints for the individual participants. Importantly, for this figure: zero percentage change means breakpoints were identical to baseline sessions, a negative percentage change means breakpoints were reduced compared to baseline, and a positive percentage change means breakpoints increased compared to baseline.

Visual inspection of the middle panel of Figure 2 suggests breakpoints were reduced during the 0 min wait time experimental sessions. Breakpoints appeared to be similar to baseline (i.e., percentage change approached zero) with wait times that produced the maximum recovery of baseline. Visual inspection of Figure 2 confirms that breakpoints and smoking (see above) followed similar trends. Further statistical analysis of breakpoint results is not reported here because breakpoints, as defined in the current study, corresponded directly with smoking (Spearman's rho = 1.00).

Change from Baseline: Latency to First Puff

Next we investigated the change from baseline latency to the first puff of the session for the 0 min wait time sessions and the maximum recovery of baseline sessions. Figure 2 (bottom panel) presents the average percentage change from baseline latencies for the individual participants. For the bottom panel of Figure 2: zero percentage change means the latencies were identical to those found in baseline sessions, a negative percentage change means latencies were shorter in duration compared to baseline latencies, and a positive percentage change means latencies were longer in duration compared to baseline levels. Visual inspection of the bottom panel of Figure 2 suggests that latencies to smoke were longer than baseline in duration when previous smoking immediately preceded experimental sessions. Latencies during the maximum recovery of baseline sessions appeared to be similar to baseline latencies.

On average, participants waited 242.12 seconds [CI: 78.38 - 405.86] longer before taking their first puff during the 0 min wait time experimental session compared to baseline. Defining equivalence as being within 90% to 111% of baseline levels, the mean latency to the first puff of maximum recovery sessions was not found to be statistically equivalent to baseline levels. However, baseline and maximum recovery means were very similar (46.31 s & 45.45 s, respectively) suggesting that the large standard errors for these estimates (46.67 & 57.85, respectively) compromised the ability to reject the null hypotheses used to calculate the statistical significance for the equivalency tests.

Discussion

The window of time over which past smoking affected current smoking was variable across participants, extending from as short as 30 minutes to as long as 90 minutes. Statistics verified that past smoking substantially reduced current smoking over short wait times (e.g., 0 min), and that with longer wait times (e.g., 30-90 min) current smoking was equivalent to when past smoking had not occurred. Latencies to smoke and breakpoints for smoking showed changes due to time without smoking that were similar to those reported in previous studies (for latencies see Griffiths & Henningfield, 1982; Zacny & Stitzer, 1985; for breakpoints see Tidey et al., 1999; Rusted et al., 1998; Willner et al., 1995; Perkins et al., 1994; Epstein et al., 1991). Procedures that measured temporal horizons among animals foraging for food (e.g., Timberlake et al., 1987) were useful in designing a novel measure of temporal horizons among smokers seeking cigarette puffs. Similar to other reinforcers (e.g., food), the effects of smoking were integrated over short time periods; however, with longer time periods smokers behaved as if only the current opportunity to smoke was available.

The current study provides support for a behavioral measure that is complimentary to questionnaires used to measure temporal horizons (e.g., Wallace, 1956; Rachlin et al., 1991). While the current procedure provides information about temporal horizons of cigarette satiety, questionnaires typically reflect on temporal horizons for cigarettes available in the future (e.g., Bickel et al., 1999; although, see also Yi et al., 2006). Temporal horizons for cigarettes available in the future have been of interest to researchers because the way individuals think about the future reflects differences between addicts and non-addicts (e.g., Petry et al., 1998; for reviews see Bickel and Marsch, 2001; Bickel et al., 2006; Reynolds, 2006) as well as severity of addiction among addicts. For example, temporal horizons for cigarettes available in the future are correlated with smoking frequency (see Johnson et al., 2007). Unfortunately, our sample size (7) precluded a rigorous statistical analysis of relationships between temporal horizons of cigarette satiety and smoking frequency or addiction severity.

While the current procedures and methods provided a more fine-grained analysis of temporal horizons of cigarettes satiety than previously available in the literature (e.g., Griffiths & Henningfield, 1982; Zacny & Stitzer, 1985), some limitations are worthy of consideration. One limitation of the current study was that our sample of smokers may not represent the general population of smokers because our participants were exclusively heavy smokers. Future studies could more fully address the possibility of a relationship between smoking frequency and measures of temporal horizon using a larger and more diverse sample of smokers (e.g., heavy and light smokers). Another limitation of the current study was that although the current procedure did find a large absolute difference in the size of recovery times from past smoking among participants, future studies may want to consider using smaller wait time intervals (e.g., 15 minutes) that could potentially detect a greater number of individual differences between participants. Ultimately, the size of the wait-time intervals that researchers choose to use should be selected in order to detect individual differences that they anticipate are meaningful in the context of the experiments they are conducting. The results of the current experiment indicate that 30 minute wait-time intervals are small enough to detect individual differences in temporal horizons among heavy smokers and thus provide a useful guide to selecting wait time intervals in future studies..

Patterns of drug self-administration reported here join previous results indicating that both drug-seeking and food-foraging behavior show regulation (i.e., the maintenance of a homeostatic balance; for an important caveat at high cost benefit ratios see DeGrandpre et al., 1992). In the current investigation, as in studies of the regulation of food consumption (e.g., Collier et al., 2002), smokers adjusted their smoking patterns to compensate or “make up” for time spent not smoking (c.f., DeGrandpre et al., 1992). Reports of regulation in drug self-administration are often cited in studies examining an animal's change in consumption due to changes in dose rather than time since last drug exposure (i.e., “As the experimenter alters meal size [dose per injection] the animal adjusts meal frequency to compensate”; Wise, 1997, pp. 2; e.g., Lynch and Carroll, 1999; Baron et al., 1992). Together, these observations provide support for the idea that there is a functional equivalence between manipulations that reduce the frequency of access to a reinforcer (e.g., drugs or food) and manipulations that reduce the size of the reinforcer (see DeGrandpre et al, 1993). Although regulation does not serve as an explanatory mechanism to account for the individual differences observed in the current results it does provide a framework for such an account based on metabolism.

One possibility is that temporal horizons of cigarette satiety provide a phenotypic marker for individual differences in nicotine metabolism (c.f., Benowitz et al., 2003). Presumably, the satiety for cigarettes we observed in this study was at least in part due to accumulation of nicotine in the blood following repeated smoking bouts. With the passage of time from the end of satiation sessions to the beginning of experimental sessions, we can infer that nicotine levels were falling due to metabolic processes, and thus reducing satiety for cigarettes. The rate of nicotine metabolism (i.e., the enzymatic driven conversion of nicotine to cotinine which reduces blood levels of nicotine) is known to be variable among individuals and between groups (e.g, Pianezza et al., 1998); therefore, variation in temporal horizons of cigarette satiety between individuals may be explained by differences in rates of nicotine metabolism. Given the possibility that metabolism and temporal horizons of cigarette satiety are related, we would predict that the window of time over which past smoking affects current smoking should be longer among ethnic groups with slower rates of nicotine metabolism than among groups with faster nicotine metabolism (e.g., African Americans and Asians compared to Whites and Hispanics; Kandel et al., 2007; however, see also Nakajima et al., 2006). Confirmation of this prediction would support the suggestion that temporal horizons of cigarette satiety provide a phenotypic marker for differences in rates of nicotine metabolism.

Cessation treatments can also be informed from consideration of addiction through the lens of temporal horizon. For instance, temporal horizons may provide an explanation for the success of drug replacement therapies. Addictive drugs often produce quick and powerful effects and limited durations of satiety (i.e., short temporal horizons of satiety). Drugs that are successful in replacement therapies produce less potent effects (e.g., using the nicotine patch to replace cigarettes) with extended periods of satiety (i.e., extended temporal horizons of satiety). The success of drug replacement therapy may come, at least in part, from users having more time to engage in rewarding activities they otherwise would have forgone while spending time pursuing or using drugs. In addition, we suggest that the development of future drug replacement therapies could benefit from consideration of the procedures used in this study to measure temporal horizon. Alternative approaches to addiction may also dictate that replacement drugs, which produce extended satiety, make for desirable alternatives to addictive analogues that produce shorter periods of satiety. At least one distinctive advantage of the methods used in temporal horizons studies is the use of a quantifiable behavioral approach to duration of satiety that does not rely on subjective methods such as self-report.

The current study examined a behavioral measure of temporal horizons of cigarette satiety among smokers that was adapted from studies of animals foraging for food. Participants showed a limited span of time (i.e., from 30-90 minutes) over which past smoking affected current motivation to smoke. Results were compared to previous studies examining questionnaires of temporal horizons and regulation of food/drug intake. We suggest that the results are consistent with the argument that there is a functional equivalence of manipulations that reduce frequency of access to reinforcers and manipulations that reduce the magnitude of reinforcers. Future experiments were proposed to further examine the ability of temporal horizons of cigarette satiety to characterize differences in nicotine metabolism and dependency between participants or groups. Applied considerations for using temporal horizons to inform cessation treatments involving drug replacement therapy were also discussed.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by NIDA grant #RA37DA006526. Several individuals made additional contributions to this research. We would like to formally thank Richard Yi, who performed informed consents when needed and provided superb supervision and guidance in general lab activities through the duration of the study. In addition, Renee Steed graciously helped us with participant payments and procurement.

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Resarch Grant R37DA006526, Tobacco Settlement Funds, and the Wilbur Mills Endowment

References

- Baron A, Mikorski J, Schlund M. Reinforcement magnitude and pausing on progressive-ratio schedules. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1992;58:377–388. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1992.58-377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS, Jacob P., III Nicotine metabolite ratio as a predictor of cigarette consumption. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2003;5:621–624. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger RL, Hsu JC. Bioequivalence trials, intersection-union tests and equivalence confidence sets. Statistical Science. 1996;11:283–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA. Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug addiction: delay discounting processes. Addiction. 2001;96:73–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Madden GJ, DeGrandpre RJ. Modeling the effects of combined behavioral and pharmacological treatment on cigarette smoking: behavioral-economic analyses. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1997;5:334–343. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.4.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Kowal BP, Gatchalian KM. Understanding addiction as a pathology of temporal horizon. The Behavior Analyst Today. 2006;7:32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Collier G, Johnson DF, Mathis C. The currency of procurement cost. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 2002;78:31–61. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.78-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Higgins ST. Behavioral economics of drug self-administration. III. A reanalysis of the nicotine regulation hypothesis. Psychopharmacology. 1992;108:1–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02245277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrandpre RJ, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Layng MP, Badger G. Unit price as a useful measure in analyzing effects of reinforcer magnitude. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1993;60:641–666. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1993.60-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein LH, Bulik CM, Perkins KA, Caggiula AR, Rodefer J. Behavioural economic analysis of smoking: money and food as alternatives. Pharmacology Biochemistry Behavior. 1991;38:715–721. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90232-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: A review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1989;12:159–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00846549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RR, Henningfield JE. Experimental analysis of human cigarette smoking behavior. Federation Proceedings. 1982;41:234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F. Moderate drug use and delay discounting: a comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:187–194. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Hu M, Schaffran C, Udry JR, Benowitz NL. Urine nicotine metabolites and smoking behavior in a multiracial/multiethnic national sample of young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2007;165:901–910. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Carroll ME. Regulation of intravenously self-administered nicotine in rats. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:198–207. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Bickel WK. Abstinence and price effects on demand for cigarettes: a behavioral-economic analysis. Addiction. 1999;94:577–588. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94457712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Fukami T, Yamanaka H, Higashi E, Sakai H, Yoshida R, Kwon J, McLeod HL, Yokoi T. Comprehensive evaluation of variability in nicotine metabolism and CYP2A6 polymorphic alleles in four ethnic populations. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;80:282–297. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Epstein LH, Grobe J, Fonte C. Tobacco abstinence, smoking cues, and the reinforcing value of smoking. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1994;47:107–112. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM, Bickel WK, Arnett M. Shortened time horizons and insensitivity to future consequences in heroin addicts. Addiction. 1998;93:729–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9357298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianezza ML, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. Nicotine metabolism defect reduces smoking. Nature. 1998;393:750. doi: 10.1038/31623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Majchrzak MJ, Pomerleau OF. Paced puffing as a method for administering fixed doses of nicotine. Addictive Behavior. 1989;15:571–575. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(89)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachlin H, Raineri A, Cross D. Subjective probability and delay. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1991;55:233–244. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1991.55-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B. A review of delay-discounting research with humans: relations to drug use and gambling. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2006;17:651–667. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3280115f99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusted JM, Mackee A, Williams R, Willner P. Deprivation state but not nicotine content of the cigarette affect responding by smokers on a progressive ratio task. Psychopharmacology. 1998;140:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s002130050783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidey JW, O'Neill SC, Higgins ST. Effects of abstinence on cigarette smoking among outpatients with schizophrenia. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1999;7:347–353. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.7.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake W. A temporal limit on the effect of future food on current performance in an analogue of foraging and welfare. 1984;41:117–124. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1984.41-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timberlake W, Gawley DJ, Lucas GA. Time horizons in rats foraging for food in temporally separated patches. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1987;13:302–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M. Future time perspective in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology. 1956;52:240–245. doi: 10.1037/h0039899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willner P, Hardman S, Eaton G. Subjective and behavioural evaluation of cigarette cravings. Psychopharmacology. 1995;118:171–177. doi: 10.1007/BF02245836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Drug self-administration viewed as ingestive behaviour. Appetite. 1997;28:1–5. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Gatchalian KM, Bickel WK. Discounting of past outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:311–317. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Stitzer ML. Effects of smoke deprivation interval on puff topography. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1985;38:109–115. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1985.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Stitzer ML, Brown FJ, Yingling JE, Griffiths RR. Human cigarette smoking: effects of puff and inhalation parameters on smoke exposure. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1987;240:554–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]