Abstract

The BRCA2 gene is involved in recombinational DNA repair and cytokinesis. BRCA2 defects are associated with chromosomal abnormalities, which is a hallmark of genomic instability that contributes to tumorigenesis. Here, we show that downregulation of a BRCA2 interacting protein (BCCIP) in HT1080 cells leads to chromosomal polyploidization, centrosome amplification and abnormal mitotic spindle formation. The BCCIP knockdown cells can enter mitosis and retain spindle checkpoint, but fail to complete cytokinesis. Our data suggest an essential role of BCCIP in the maintenance of genomic integrity.

Keywords: cytokinesis, chromosome instability, BRCA2, BCCIP, polyploidy

Introduction

Human cancers are characteristic of numerical and structural chromosomal instability. Structural chromosome instability, including reciprocal and nonreciprocal translocations, regional chromosomal amplifications/insertions/deletions, may arise from defects in cell cycle checkpoints, DNA recombination, DNA repair and telomere maintenance. Numerical chromosomal instability (gain or loss of chromosomes) arises from chromosome segregation errors during mitosis, or failure to complete cell separation at the end of mitosis (cytokinesis). Aneuploidy generally results from chromosome segregation errors, which may be a consequence of misregulation of microtubule dynamics, centrosome replication, chromosome condensation, kinetochore assembly, chromosome cohesion and spindle checkpoint control (Lengauer et al., 1998). A second type of numerical chromosomal abnormality is polyploidization, which may result from failed completion of mitosis followed by a failure of the immediate G1/S checkpoint activation (or tetraploid checkpoint) (Margolis et al., 2003).

The tumor suppressor gene BRCA2 is involved in homologous recombinational DNA repair that contributes to structural chromosome stability (Moynahan et al., 2001; Venkitaraman, 2002; Powell and Kachnic, 2003). BRCA2 also participates in the regulation of mitosis and cytokinesis that contribute to numerical chromosomal stability (Daniels et al., 2004; Rudkin and Foulkes, 2005). BRCA2 interacting protein α (BCCIPα) is a BRCA2 and CDKN1A (p21, Waf1 and Cip1) Interacting Protein (Ono et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2001). Owing to alternative splicing, a second isoform BCCIPβ is expressed in human cells (Meng et al., 2003). BCCIPα and BCCIPβ share identical N-terminal 258 amino acids, but each has a unique C-terminal sequence (Meng et al., 2003). Additional studies have shown that BCCIPβ interacts with BRCA2 and p21 (Meng et al., 2004a; Lu et al., 2005). The chromatin-bound fraction of BCCIPα/β colocalizes with BRCA2 and contributes to BRCA2 and RAD51 nuclear focus formation (Lu et al., 2005). A moderate knockdown (∼50% of downregulation) of both or either BCCIP isoform significantly reduces DNA double-strand break-induced homologous recombination, impairs G1/S checkpoint activation, abrogates p53 transactivation activities and downregulates p21 expression (Meng et al., 2004a, b, 2007; Lu et al., 2005). In this sudy, we show that severely downregulated BCCIP expression results in mitosis defect and chromosome instability in HT1080 cells, suggesting BCCIP as a critical player in maintaining chromosome stability.

Results

BCCIP knockdown causes chromosome instability

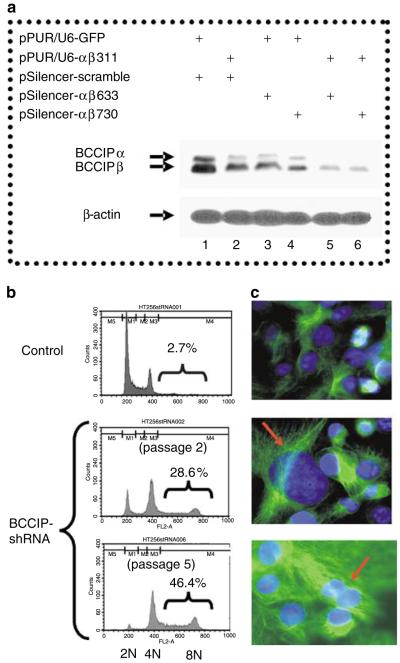

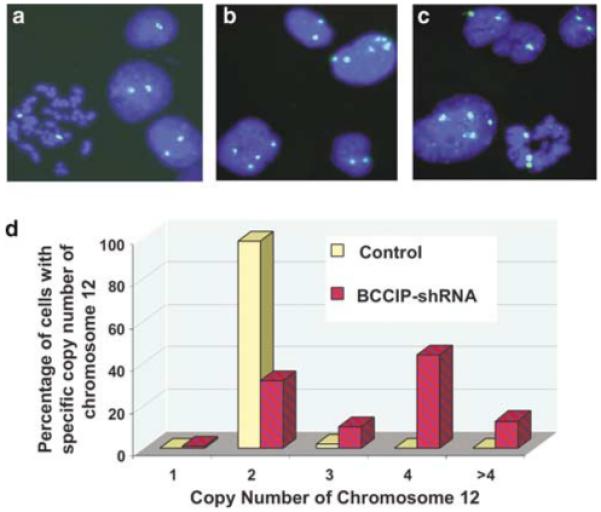

In a study when BCCIPα and/or BCCIPβ were partially downregulated by RNAi, we observed an increase in polyploid cells after an extended culture of cells with moderate BCCIP knockdown (Supplementary Figure S1), suggesting a potential role of BCCIP in chromosomal instability. To investigate this, we established cell lines with severe BCCIPα/β knockdown (>95% downregulation) in HT1080 cells by combining two short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeted at two independent regions of the BCCIPα/β mRNA (Figure 1a). Although the growths of these cells are compromised in later stage of culture, the cells can be maintained in culture for a few passages. In these cells, we observed an increase in polyploid cells between passages 2 and 5 (Figure 1b). Consistent with this observation, severe BCCIP knockdown induces cells with large or multiple nuclei (Figure 1c). In addition, we used a chromosome 12-specific centromeric DNA probe to quantify chromosome numbers by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). As shown in Figure 2a and d, control HT1080 cells are mostly diploid. However, the BCCIP knockdown cells displayed a significant increase in cells with more than two copies of chromosome 12 (Figure 2b-d). These data strongly suggest chromosome instability in cells with severely downregulated BCCIP.

Figure 1.

BCCIP knockdown by shRNA induces polyploidization of HT1080 cells. (a) Knockdown of BCCIP by shRNA. Three common regions between BCCIPα and BCCIPβ mRNA at locations αβ311 bp, αβ 633 bp and αβ 730 bp were selected for shRNA targeting, because they have no significant homology with any other human expressed sequence tags (EST) sequences based on a basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) search (see Materials and methods section for the details of nucleotide sequences and vector construction). The efficacy of combining two shRNAs to severely knockdown BCCIP expression is shown. Combining two shRNAs is feasible, because pPUR/U6 and pSilencer use different selection markers (see Materials and methods section for details). Cells transfected with indicated shRNA vectors were selected with puromycin and hygromycin. Immunoblots of whole cell extract were carried out with anti-BCCIP (top panel), or anti-β-actin blot (lower panel). As shown here (lanes 2-4), targeting by a single BCCIP shRNA creates a moderate knockdown (∼50%) condition for BCCIP. By combining two shRNAs (lanes 5 and 6), shRNA-αβ311/shRNA-αβ633 or shRNA-αβ311/shRNA-αβ730, a severe knockdown condition with ∼95% BCCIPα/β downregulation was created. These two cell lines (lanes 5 and 6) have identical phenotypes and were used for subsequent experiments unless stated otherwise. (b) Polyploidization in BCCIP knockdown cells measured by DNA content analysis. The DNA content of BCCIP knockdown cells were analysed by flow cytometry at passages 2 and 5. The percentages of cells with more than 4N DNA content are indicated. (c) Formation of cells with large nucleus after BCCIP knockdown. Representative cell morphology after the cells were stained with anti-α-tubulin and DAPI to contrast the nuclei from the cytoplasm. Arrows indicate BCCIP knockdown cells with large or multiple nuclei.

Figure 2.

Chromosome number abnormality in BCCIP knockdown cells. A chromosome 12-specific centromeric DNA probe was used for FISH analysis and to index chromosomal stability of control and BCCIP knockdown cells (passage 5) as reported by others (Jallepalli et al., 2001). DNA was stained with DAPI (blue). (a) represents control cells, (b and c) represent BCCIP knockdown cells and (d) illustrates the distribution of cells with different number of chromosome 12. More than 300 cells were scored for each group.

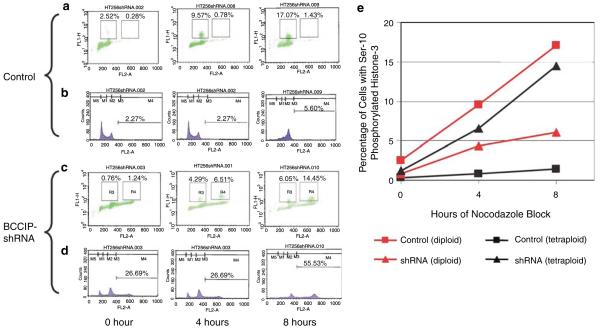

Knockdown of BCCIP does not prevent the entry of G2 cells into M phase

Polyploidy can be induced by endoreduplication, by which the cells do not enter mitosis but reenter S-phase after the previous round of DNA replication. Polyploidy can also result from reentry into interphase (and subsequent DNA replication) after a failed cell division in mitosis. To distinguish the potential mechanisms by which BCCIP knockdown induces polyploidization, HT1080 cells were incubated with nocodazole to be blocked at metaphase, and then stained with an antibody to Serine-10 phosphorylated histone H3, ph(Ser10)H3, which marks mitotic cells (Hans and Dimitrov, 2001). The specificity of this antibody to mitotic cells was confirmed by immunostaining of HT1080 cells (Supplementary Figure S2). After the DNA was co-stained with propidium iodide, the ph(Ser10)H3 positive cells were scored by flow cytometry. In control cells, ph(Ser10)H3 positive cells accumulate in diploid population but little in tetraploid after nocodazole block (Figure 3a, b and e). However, in BCCIP knockdown cells, ph(Ser10)H3 positive cells accumulate in both the diploid and tetraploid populations after nocodazole block (Figure 3c-e). The accumulation kinetics of ph(Ser10)H3 positive tetraploid BCCIP knockdown cells is approximately the same as that of the diploid control cells. These data suggest that the BCCIP knockdown cells indeed enter mitosis. They also suggest that BCCIP knockdown cells have normal spindle checkpoint activation as nocodazole effectively blocks cells at metaphase. Therefore, the polyploidization in BCCIP knockdown cells is likely due to a failure of cell division after passing the metaphase (see below), but unlikely due to an endoreduplication of DNA in S phase.

Figure 3.

BCCIP knockdown does not affect the entry into mitosis. Control or BCCIP knockdown HT1080 cells (passage 3) were incubated with nocodazole for 4 or 8 h to block cells at metaphase. After being fixed with ethanol, cells were double stained with Serine-10 phosphorylated histone-3 antibody (ph(Ser10)H3) (green) to mark mitotic cells and propidium iodide for DNA (red). In (a-d), the horizontal axis represents the DNA content. In (b and d), the vertical axis represents the number of cells. In (a and c), the vertical axis represents the ph(Ser10)H3 level, and regions R3 and R4 represent the diploid and tetraploid mitotic cells, respectively. (e) shows the percentage of ph(Ser10)H3 positive diploid and tetraploid cells in control and BCCIP knockdown HT1080 cells.

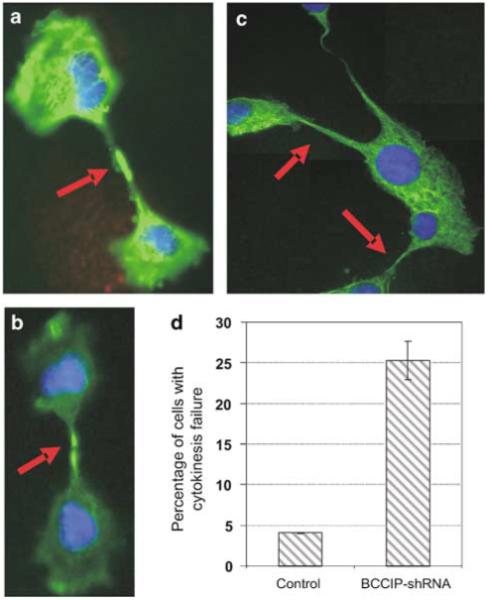

BCCIP knockdown causes cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification

BRCA2 is involved in cytokinesis (Daniels et al., 2004), and interacts with BCCIP. Because BCCIP knockdown causes polyploidization, which has likely caused a failure of a critical step after the cells have passed the metaphase (Figure 3), we investigated whether BCCIP is involved in cytokinesis. We found that BCCIP knockdown significantly increased the percentage of cells with failed cytokinesis (Figure 4), suggesting that BCCIP knockdown induces chromosomal polyploidization by impairing cytokinesis, although we cannot exclude the possibility that a small portion of the cells may adopt endoreduplication or abort mitosis at a stage earlier than cytokinesis.

Figure 4.

BCCIP knockdown induces cytokinesis failure. Cells were stained with anti-α-tubulin. (a-c) represent typical BCCIP knockdown cells with cytokinesis failure. (d) shows the percentage of cells with morphology consistent with cytokinesis failure. Shown are the average results of two cell lines at passage 5 (lanes 5 and 6 in Figure 1a). A minimum of 300 cells was scored in each cell line.

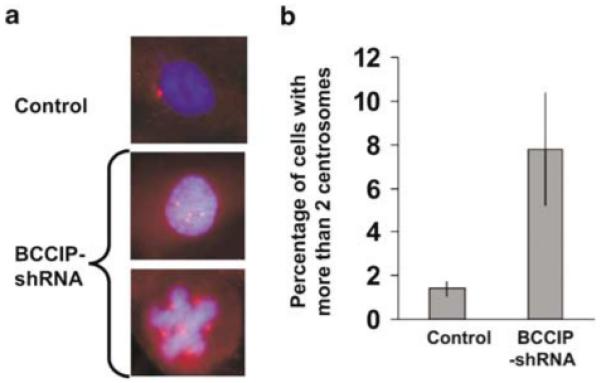

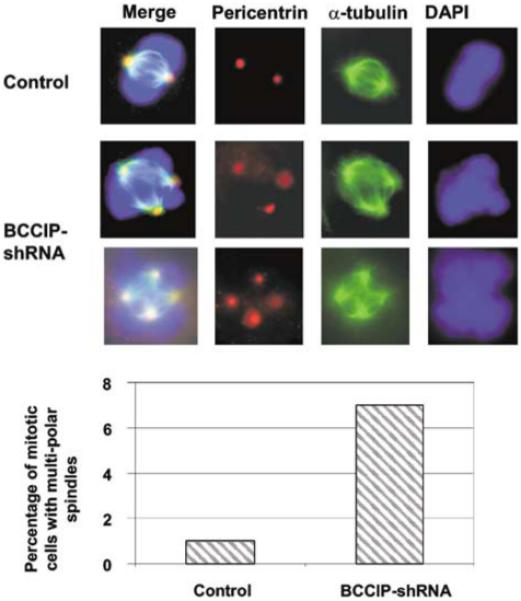

It has been suggested that polyploidization may cause centrosome amplification in p53-deficient cells (Meraldi et al., 2002). We further investigated whether the knockdown of BCCIP can affect centrosomes. As shown in Figure 5a, we indeed observed an increase of cells with abnormal number of centrosomes in BCCIP knockdown cells. In control cells, about 1.2% cells have more than two centrosomes. However, we observed ∼8% of the BCCIP knockdown cells with more than two centrosomes (Figures 5b). Centrosome amplification was also observed in cells with single BCCIP isoform knockdown (Supplementary Figure S3). In addition, downregulation of BCCIP induces formation of multipolar mitotic spindles (Figure 6). Centrosome amplification and multipolar mitotic spindles are further evidence of genome instability in BCCIP knockdown cells.

Figure 5.

Centrosome amplification in BCCIP knockdown cells. (a) shows centrosome staining in control cells and in BCCIP knockdown cells (passage 5) with more than two centrosomes (bottom two panels). Centrosomes (red) were stained with anti-pericentrin, and nuclei with DAPI (blue). (b) shows the percentage of cells with more than two centrosomes per nucleus. Presented are averages of two independent cell lines (lanes 5 and 6 in Figure 1a). More than 300 cells were scored from each cell line.

Figure 6.

Multipolar spindle formations in BCCIP knockdown cells. Centrosomes were stained with anti-pericentrin (red), mitotic spindle (green) with anti-α-tubulin and DNA (blue) with DAPI. (a) shows normal spindle in control and multiple polar spindles in BCCIP knockdown cells. (b) shows the percentage of mitotic cells with multipolar spindles, which was obtained by counting 100 mitotic cells from two independent BCCIP knockdown cell lines at passage 5 (lanes 5 and 6 of Figure 1a).

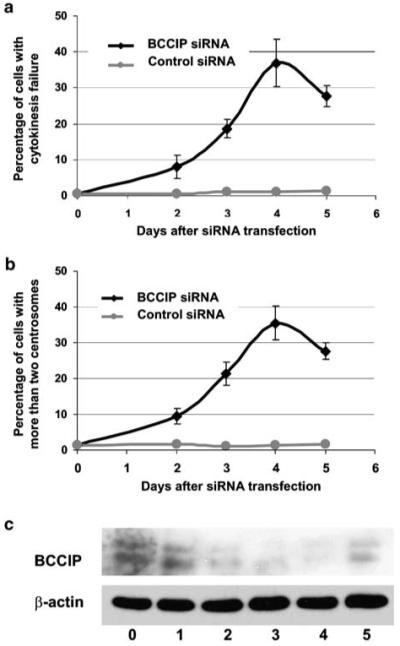

Cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification are immediate events following BCCIP knockdown

To determine whether cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification are the primary consequences of BCCIP knockdown, we transfected a mixture of two independent small interference RNAs (siRNAs) targeted at regions αβ311 and αβ633 into the cells. The level of BCCIP starts to decline 24 h after transfection, and reaches the lowest level by day 4. However, at day 5 after the transient transfection, the BCCIP level starts to recover (Figure 7c), which is common when siRNA is transiently transfected into the cells. This may be due to the transient nature of transfected siRNA, or due to a potential fast growth of a non-transfected subpopulation of cells. In these cells with acute BCCIP knockdown, we observed an increase of cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification as early as 2 days after transfection of BCCIP siRNA (Figure 7a and b), suggesting that the cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification are early effects of BCCIP downregulation. These data also show that the kinetics of centrosome amplification and cytokinesis failure (thus tetraploidization) are almost identical in HT1080. Among the cells with more than two centrosomes, about 48% have three or five centrosomes, and 52% have four or six centrosomes, suggesting that the centrosome amplification may also be caused by unbalanced mitotic division.

Figure 7.

Induction of cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification after acute BCCIP knockdown with siRNA. Various times after HT1080 cells transfected with control luciferase siRNA or a mixture of BCCIP siRNA αβ311 and αβ633 siRNA, cells were stained with anti-α-tubulin to score cytokinesis failure and with anti-pericentrin to score centrosome amplification. For the purpose of counting centrosomes, cells with cytokinesis failure but more than one nucleus were counted as a single cell. The percentages of cells with cytokinesis failure (a) or with more than two centrosomes (b), and the average and standard deviation from three independent experiments are shown. (c) shows the reduced expression of BCCIP in BCCIP knockdown cells used in (a) and (b), and anti-actin blot was used as a loading control.

In addition, the method described by Fukasawa et al. (1996) was modified to identify whether centrosome amplification and cytokinesis failure occur during the first cycle of cell division following release from G0 arrest. Briefly, 1 day after BCCIP siRNA transfection, cell cycle progression was arrested by 0.5% serum starvation for 60 h and then released by changing medium back with 10% serum. Sixteen hours after the release from the G0 arrest, we observed 0.5% of control cells and 8.9% of BCCIP knockdown cells with cytokinesis failure, and 0.7% of control cells and 7.7% of BCCIP knockdown cells with more than two centrosomes. These data suggest that the observed cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification occur during the immediate round of cell cycle after release from G0 phase.

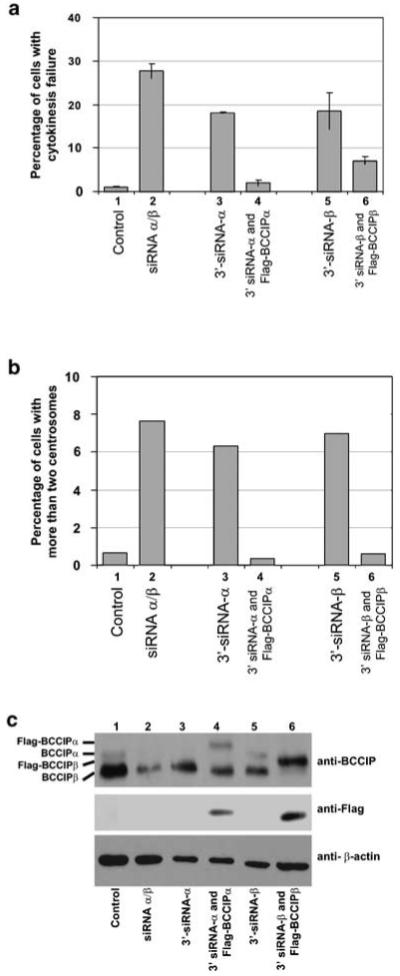

Centrosome amplification and cytokinesis failure caused by BCCIP knockdown can be prevented with expression of exogenous BCCIP

To further support the role of BCCIP in cytokinesis and centrosome amplification, and to rule out the possibility that the cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification in BCCIP knockdown cells are caused by off-target effects, exogenous flag-BCCIPα or flag-BCCIPβ were constitutively expressed in HT1080 cells. Then the expressions of endogenous BCCIPα or BCCIPβ were downregulated by siRNAs targeted at the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTR) of BCCIPα or BCCIPβ mRNA (3′-BCCIP siRNA). Expressions of the exogenous flag-BCCIPα or flag-BCCIPβ were not affected by the 3′-BCCIP siRNA (Figure 8c) because the flag-BCCIP vectors contain no 3′-UTR. As shown in Figure 8a and b (columns 3 and 5), targeting BCCIPα or BCCIPβ 3′-untranslated regions alone increased the percentage of cells with cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification. However, expression of flag-BCCIPα or flag-BCCIPβ in these cells significantly reduced cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification (columns 4 and 6, Figure 8a and b). These data further support the role of BCCIP in cytokinesis and centrosome amplification and ruled out off-target effect of BCCIP RNAi on centrosome amplification and cytokinesis failure.

Figure 8.

Prevention of cytokinesis failure and centrosome amplification in BCCIP knockdown cells by exogenous BCCIP expression. Flag-BCCIPα or flag-BCCIPβ was expressed in HT1080 cells. Control cells were transfected with an empty vector. Then these cells were transfected with various siRNAs as defined: lane (1) control cells transfected with luciferase siRNA; lane (2) control cells transfected with BCCIP siRNA targeted at common regions 311 and 633; lane (3) control cells tranfected with 3′-siRNA against BCCIPα (3′-siRNA-α); lane (4) flag-BCCIPα expressing cells transfected with siRNA targeted at the 3′ untranslated region of BCCIPα mRNA (3′-siRNA-α); lane (5) control cells transfected with siRNA targeted at the 3′untranslated region of BCCIPβ mRNA (3′-siRNA-β) and lane (6) flag-BCCIPβ expressing cells transfected with siRNA targeted at the 3′-untranslated region of BCCIPβ mRNA (3′-siRNA-β). After the siRNA transfections, cells with cytokinesis failure or more than two centrosomes per nucleus were counted. (a) shows the percentage of cells with cytokinesis failure, (b) shows the percentage of cells with centrosome amplification, (c) shows the expression of BCCIP as blotted by anti-BCCIP, anti-flag and anti-actin in these cells.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a functional role of BCCIP in numerical chromosome stability in HT1080 cells. We show that BCCIP downregulation causes failure of cytokinesis, centrosome amplification and abnormal spindle formation. These data strongly support a role of BCCIP in the maintenance of genome stability. Because chromosome instability is associated with tumor progression, these findings indicate that loss of BCCIP may be associated with tumor aggression. The human BCCIP gene is located at 10q26 (Liu et al., 2001), which has been implicated in many forms of human tumors, including astrocytic brain tumors (Rasheed et al., 1992; Maier et al., 1998; Merlo, 2003; Ohgaki et al., 2004). We have previously shown that BCCIP expression is downregulated in kidney cancer (Meng et al., 2003), BCCIPα expression was not detectable in astrocytic brain cancer cell line A172 (Liu et al., 2001), and BCCIP deletion has been suggested in a brain tumor cell line (Roversi et al., 2005). Recently, we found loss of BCCIP expression in a significant portion of aggressive astrocytic brain tumors (manuscript in preparation), further supporting the role of BCCIP in genomic instability and tumor aggression.

Cells that prematurely exit mitosis must bypass the subsequent G1/S checkpoint (sometimes referred as tetraploidy G1/S checkpoint) before the next DNA replication to become polyploidy (Margolis et al., 2003). It has been suggested that this G1/S tetraploidy checkpoint is dependent on p53 function (Andreassen et al., 2001). Thus, the p53 functions may have also been impaired in BCCIP knockdown HT1080 cells. We previously reported that BCCIP knockdown inactivates the G1/S checkpoint (Meng et al., 2004a, b). Recently, we have shown that the transactivation activity of wild-type p53 is ablated by BCCIP downregulation (Meng et al., 2007). Therefore, the BCCIP knockdown cells would be able to silence the tetraploidy checkpoint after failed cytokinesis, to bypass G1/S checkpoint and to become susceptible for the next round of DNA replication, all of which leads to polyploidization.

Both aneuploidy and polyploidy are forms of chromosomal instability. The mechanisms by which aneuploidy and polyploidy occur are subtly different. Aneuploidy often results from chromosome segregation errors during mitosis, while polyploidy may be a consequence of failed cytokinesis, DNA endoreduplication or endomitosis as in megakaryocyte differentiation (Geddis and Kaushansky, 2004). Our data have shown that cytokinesis failure is the major consequence of BCCIP knockdown, which is accompanied by centrosome amplification in the first cell cycle after BCCIP knockdown (Figure 7). We also observed that some BCCIP knockdown cells have three copies of chromosome (Figure 2d), suggesting aneuploidy. Although we cannot rule out that the modest-level aneuploidy is a result of chromosome segregation errors, it is unlikely caused by spindle checkpoint defect as nocodazole effectively blocked BCCIP knockdown cells at metaphase (Figure 3). It is possible that the aneuploidy is a result of abnormal mitotic spindle formations, which are consequence of the centrosome amplification and cytokinesis failure. In addition, some BCCIP knockdown cells have more than two and unpaired (such as three or five) centrosomes. This would add further mechanism for aneuploidy formation.

BRCA2 is involved in cytokinesis and homologous recombination (Moynahan et al., 2001; Venkitaraman, 2002; Powell and Kachnic, 2003; Daniels et al., 2004). We have previously reported that chromatin-bound fraction of BCCIP colocalizes with BRCA2, and a modest knockdown of BCCIP (∼50% of BCCIP reduction) reduces DNA double-strand break-induced homologous recombination (Lu et al., 2005). In this study, we show that BCCIP is involved in cytokinesis and chromosomal stability. Therefore, BCCIP may regulate the maintenance of genome stability through multiple pathways: homologous recombinational repair (Lu et al., 2005), G1/S checkpoint (Meng et al., 2004a, b) and cytokinesis. It remains to be determined whether the interaction between BRCA2 and BCCIP plays a direct role in cytokinesis. In addition, it has been reported that p53 protein has both transcription-dependent and -independent role in preventing centrosome amplification (Tarapore et al., 2001; Tarapore and Fukasawa, 2002; Shinmura et al., 2006), and the transcriptional-dependent function of p53 in centrosome amplification is likely mediated by p21 (Tarapore et al., 2001) and BCCIP interacts with p21 (Meng et al., 2004a, b) and BCCIP down-regulation abrogates the transcriptional activity of p53 (Meng et al., 2007). It is possible that BCCIP may regulate centrosome stability through p53 and p21 functions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

HT1080 cells were cultured in αMEM (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biowhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA), 20 mm glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco BRL). Plasmids were transfected into cells using the Geneporter transfection kit (Gene Therapy Systems Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Flag-BCCIP expression in HT1080 cells were mediated by the pLXSP vector-based retrovirus infection as reported previously (Liu et al., 2001).

Antibodies and Western blot

Rabbit anti-BCCIPα/β antibodies were reported previously (Liu et al., 2001). Other antibodies were purchased as: anti-Ser-10 phosphorylated histone H3 (ph(Ser10)H3) antibodies from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY, USA); anti-β-actin and anti-α-tubulin antibodies from Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA); and anti-pericentrin antibody from Covance Research Products Inc. (Berkeley, CA, USA). Protein extracts were prepared from cells lysed with 50 mm 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethane-sulfonic acid, pH 7.6, 250 mm NaCl, 5 mm ethylenediaminete-traacetic acid and 0.1% Nonidet P-40. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and Western blotting was performed as described (Meng et al., 2004a, b). Anti-flag antibody was purchased from Sigma.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells grown on coverslips were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with methanol. The fixed cells were washed with Tris buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBS-T) (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) three times and blocked for 30 min with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS-T. Cells were incubated in rabbit anti-pericentrin (1:300), or mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:300) primary antibody diluted in 3% BSA blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. After washing three times with TBS-T, cells on coverslips were incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with fluorescein (FITC) or Texas Red (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, washed and mounted using mounting medium containing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The images were recorded using a Zeiss fluorescence microscopy with an Axioskop digital camera.

Knockdown of BCCIP expression by shRNA

We used two vectors to express shRNA to knockdown BCCIP expression. The plasmid pPUR/U6 uses a puromycin resistance cassette, while the pSilencer2.1Hyg (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX, USA) uses hygromycin B as the selection marker. The control vectors express either a scrambled sequence 5′-ACT ACC GTT GTT ATA GGT G-3′ (Ambion Inc.) in pSilencer2.1Hygomycin or a GFP cDNA target sequences 5′-GGT TAT GTA CAG GAA CGC A-3′ in pPUR/U6.

The isoform specific BCCIP silencing has been reported (Lu et al., 2005). Briefly, isoform-specific sequences targeting BCCIPα (5′-GGG AAC CTT CAT GAC TGT TGG) or BCCIPβ (5′-GGG AAG CAA ATG GTC TTT TGA) were inserted into pPUR/U6. To knockdown both BCCIPα and BCCIPβ isoforms, several shRNA sequences targeted at the shared region of BCCIPα and BCCIPβ were used, including: shRNA-αβ311 (5′-GTG TGA TTA AGC AAA CGG AT G-3′), shRNA-αβ633 (5′-GCC ATG TGG GAA GTG CTA C-3′), and shRNA-αβ730 (5′-GCT GCG TTA ATG TTT GCA AAT-3′). We found that application of a single shRNA can only cause ∼50% downregulation of BCCIP (Figure 1a), which is referred as ‘moderate knockdown’ in this study. To knockdown BCCIPα/β further, we combined two shRNAs: αβ311 and αβ633 or αβ311 and αβ730, creating ∼95% downregulation of BCCIP (Figure 1a), referred as ‘severe knockdown’ condition in this study. Briefly, HT1080 cells were transfected with pPUR/U6 (with puromycin as selection marker) vectors expressing either control or BCCIP shRNA-αβ311, and then selected in puromycin for 2 weeks. The puromycin-resistant cells were further transfected with pSilencer2.1 (with hygomycin as the selection marker) control or BCCIP shRNA-αβ633 or shRNA-αβ730 vectors and selected by hygromycin B. After 2 weeks’ selection, puromycin and hygromycin double-resistant HT1080 cells with BCCIP severe knockdown were established and designated as passage 1. Cells were passed every 3 days and cultured in the medium containing both puromycin and hygromycin.

Acute knockdown of BCCIP expression by siRNA

The siRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Ambion Inc.). The firefly luciferase control siRNA 5′-CTT ACG CTG AGT ACT TCG A-3′ was used as negative control. The BCCIPα 3′-terminus-untranslated region-specific siRNA is 5′-AAC ATC TCG GCA CCT AGT AAT-3′. The BCCIPβ 3′-terminus untranslated region specific siRNA is 5′-AAC TCA GAC TTT ATT CAG ATT AA-3′. siRNA was transfected by lipofectamine (Gibco BRL, Rockville, MD, USA).

Flow cytometry analysis

DNA content analysis by flow cytometry has been described previously (Meng et al., 2004a, b, c). Cells were fixed with 70% ethanol overnight, washed with PBS and incubated with mouse anti-ph(Ser10)H3 antibody (1:200 dilution). After washing, these cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin before analysed by flow cytometry to score ph(Ser10)H3 positive cells.

FISH analysis of chromosomes

A chromosome 12-specific centromeric FISH probe (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, IL, USA) was used to hybridize HT1080 cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol with high stringent washing condition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute of Health grants CA115488 and ES08353 and by the US Army Medical Research and Materiel Command grants DAMD17-02-1-0515 and DAMD17-03-1-0317. We thank the technical support from the flow cytometry and the fluorescence microscopy facility of UNM Cancer Research and Treatment Center.

References

- Andreassen PR, Lohez OD, Lacroix FB, Margolis RL. Tetraploid state induces p53-dependent arrest of nontransformed mammalian cells in G1. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:1315–1328. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.5.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels MJ, Wang Y, Lee M, Venkitaraman AR. Abnormal cytokinesis in cells deficient in the breast cancer susceptibility protein BRCA2. Science. 2004;306:876–8769. doi: 10.1126/science.1102574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukasawa K, Choi T, Kuriyama R, Rulong S, Vande Woude GF. Abnormal centrosome amplification in the absence of p53. Science. 1996;271:1744–1747. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geddis AE, Kaushansky K. Megakaryocytes express functional Aurora-B kinase in endomitosis. Blood. 2004;104:1017–1024. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans F, Dimitrov S. Histone H3 phosphorylation and cell division. Oncogene. 2001;20:3021–3027. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jallepalli PV, Waizenegger IC, Bunz F, Langer S, Speicher MR, Peters JM, et al. Securin is required for chromosomal stability in human cells. Cell. 2001;105:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Yuan Y, Huan J, Shen Z. Inhibition of breast and brain cancer cell growth by BCCIPalpha, an evolutionarily conserved nuclear protein that interacts with BRCA2. Oncogene. 2001;20:336–345. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Guo X, Meng X, Liu J, Allen C, Wray J, et al. The BRCA2-interacting protein BCCIP functions in RAD51 and BRCA2 focus formation and homologous recombinational repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:1949–1957. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.5.1949-1957.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier D, Zhang Z, Taylor E, Hamou MF, Gratzl O, Van Meir EG, et al. Somatic deletion mapping on chromosome 10 and sequence analysis of PTEN/MMAC1 point to the 10q25-26 region as the primary target in low-grade and high-grade gliomas. Oncogene. 1998;16:3331–3335. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis RL, Lohez OD, Andreassen PR. G1 tetraploidy checkpoint and the suppression of tumorigenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2003;88:673–683. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Liu J, Shen Z. Genomic structure of the human BCCIP gene and its expression in cancer. Gene. 2003;302:139–146. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Liu J, Shen Z. Inhibition of G1 to S cell cycle progression by BCCIP beta. Cell Cycle. 2004a;3:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Lu H, Shen Z. BCCIP functions through p53 to regulate the expression of p21Waf1/Cip1. Cell Cycle. 2004b;3:1457–1462. doi: 10.4161/cc.3.11.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Yuan Y, Maestas A, Shen Z. Recovery from DNA damage-induced G2 arrest requires actin-binding protein filamin-A/actin-binding protein 280. J Biol Chem. 2004c;279:6098–6105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306794200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Yue J, Liu Z, Shen Z. Abrogation of the transactivation activity of p53 by BCCIP down-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:1570–1576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meraldi P, Honda R, Nigg EA. Aurora-A overexpression reveals tetraploidization as a major route to centrosome amplification in p53-/- cells. Embo J. 2002;21:483–492. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo A. Genes and pathways driving glioblastomas in humans and murine disease models. Neurosurg Rev. 2003;26:145–158. doi: 10.1007/s10143-003-0267-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynahan ME, Pierce AJ, Jasin M. BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol Cell. 2001;7:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgaki H, Dessen P, Jourde B, Horstmann S, Nishikawa T, Di Patre PL, et al. Genetic pathways to glioblastoma: a population-based study. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6892–6899. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Kitaura H, Ugai H, Murata T, Yokoyama KK, Iguchi-Ariga SM, et al. TOK-1, a novel p21Cip1-binding protein that cooperatively enhances p21-dependent inhibitory activity toward CDK2 kinase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31145–31154. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell SN, Kachnic LA. Roles of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in homologous recombination, DNA replication fidelity and the cellular response to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5784–5791. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasheed BK, Fuller GN, Friedman AH, Bigner DD, Bigner SH. Loss of heterozygosity for 10q loci in human gliomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1992;5:75–82. doi: 10.1002/gcc.2870050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roversi G, Pfundt R, Moroni RF, Magnani I, van Reijmersdal S, Pollo B, et al. Identification of novel genomic markers related to progression to glioblastoma through genomic profiling of 25 primary glioma cell lines. Oncogene. 2005;25:1571–1583. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudkin TM, Foulkes WD. BRCA2: breaks, mistakes and failed separations. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinmura K, Bennett RA, Tarapore P, Fukasawa K. Direct evidence for the role of centrosomally localized p53 in the regulation of centrosome duplication. Oncogene. 2006 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210085. E-pub 30 Oct 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarapore P, Fukasawa K. Loss of p53 and centrosome hyperamplification. Oncogene. 2002;21:6234–6240. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarapore P, Horn HF, Tokuyama Y, Fukasawa K. Direct regulation of the centrosome duplication cycle by the p53-p21Waf1/Cip1 pathway. Oncogene. 2001;20:3173–3184. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkitaraman AR. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell. 2002;108:171–182. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.