Abstract

Membrane proteins fold, assemble and function within their native fluid lipid environment. Structural studies of fluid lipid bilayers are thus critically important for understanding processes in membranes. Here we propose a simple approach to visualize the hydrocarbon core using neutron diffraction and deuterated lipids that are commercially available. This method should have broad utility in structural studies of bilayer response to protein insertion and folding in membranes.

INTRODUCTION

Membrane proteins require a lipid environment for their folding, assembly, and activity (1–4). The structure of the lipid bilayer is an important determinant of the structure, and hence the function, of the embedded membrane proteins, and thus many studies have been aimed at structural characterization of fluid bilayers (5–7). Furthermore, the bilayer plays an active role during the processes of folding, insertion, and translocation of proteins, and therefore studies have also focused on the effect of the embedded proteins on bilayer structure (8–11). Structural studies of fluid bilayers, however, are challenging due to the very high thermal disorder that is intrinsic to the native membrane state (12). This thermal disorder challenges the traditional views of structure and requires novel approaches for structure determination.

One of the popular bilayer structure characterization methods is diffraction of multilayers, which gives the transbilayer scattering density distribution (10;13;14). More than 15 years ago White and colleagues proposed that since atomic positions in fluid bilayers cannot be resolved, diffraction experiments can be used to obtain the transbilayer distributions of different lipid structural groups, such as carbonyls, phosphate, choline, etc. (15), and showed experimentally that these distributions are well described by Gaussians (16;17). Based on this concept, Wiener and White then determined the complete structure of the DOPC bilayer at 66% RH, as given by the full set of such distributions (18).

Solving complete bilayer structures is a labor-intensive and time consuming task, requiring acquisition of both X-ray and neutron data and utilizing multiple specifically labeled lipid analogues (18). Thus, 15 years after the accomplishment of Wiener and White, the DOPC structure at 66% RH remains the only complete bilayer structure that has been solved. Questions therefore arise as to how the complete structures of other bilayers compare to the DOPC structure at 66%RH, and how the incorporation of proteins will alter these structures. Since it is not feasible to determine complete bilayer structures for every incorporated protein of interest, an alternative approach is to monitor the effect of peptide incorporation on the distribution of a particular lipid moiety. For instance, the effect of hydration and peptide incorporation on the hydrocarbon core has been studied by monitoring the changes in the transbilayer distribution of the double-bonds in X-ray experiments (8;9;19). This approach, however, requires bromine atom derivatization of the double bonds, and in some cases the bulky bromine atoms can perturb the bilayer structure (as we have observed for DOPC bilayers with 4 mole% melittin, unpublished results).

Here we propose a different approach to monitor changes in the hydrocarbon core using neutron diffraction and deuterated lipids that are commercially available. The lipid we use is 1-Palmitoyl (D31)-2-Oleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine, a POPC derivative with the palmitoyl chain deuterated. The comparison of scattering profiles of POPC bilayers with different concentrations of the deuterated POPC analog allows a straightforward determination of the HC distribution via contrast variation, and an easy calculation of the hydrocarbon core thickness. We demonstrate the feasibility of this approach for pure POPC bilayers, and we also determine the hydrocarbon core distribution in the presence of a peptide corresponding to the sequence of the TM domain of a human receptor tyrosine kinase.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample preparation

1-Palmitoyl-2-Oleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (POPC) and 1-Palmitoyl (D31)-2-Oleoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine (POPCD, with the palmitoyl chain deuterated) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and D2O was obtained from Cambridge Isotope labs (Andover, MA). The peptide corresponding to the FGFR3 TM domain sequence, RRAGSVYAGILSYGVGFFLFILVVAAVTLCRLR was synthesized as reported previously (20). Four multilayer POPC/POPCD samples and two multilayer POPC/POPCD samples containing peptides were prepared and characterized using neutron diffraction. The four lipid multilayer samples were (1) 100 mole% POPC, (2) 95 mole% POPC+5 mole% POPCD, (3) 90 mole% POPC+10 mole% POPCD, and (4) 80 mole% POPC+20 mole% POPCD. The two lipid/peptide samples were (1) 96 mole% POPC+4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain and (2) 96 mole% (80 mole% POPC and 20 mole% POPCD) + 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain. The pure lipid multilayers were prepared by mixing POPC and POPCD in chloroform. The lipid/peptide samples were prepared by dissolving the peptides in a mixture of trifluoroethanol and hexafluoroisopropanol (1:2 ratio) and the lipids in chloroform (21;22). The organic solutions were mixed in the appropriate ratios and deposited drop-wise on a thin glass slide. The organic solvents were evaporated, and the samples were hydrated as described below. The size of each multilayer sample was about 15mm × 17mm × 5μm.

Neutron diffraction experiments, data collection and analysis

Neutron diffraction experiments were performed at the Advanced Neutron Diffractometer/Reflectometer (AND/R) at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) center for Neutron Research, Gaithersburg, MD. The wavelength of the neutron beam was 5Å. Each multilayer sample was hydrated using H2O mixed with 0%, 20% and 50% D2O. Relative humidity (RH) of 76% was achieved using a saturated NaCl solution, as previously described (19;23). The solution was placed next to the sample in a sealed aluminum container, and diffraction pattern changes were recorded during sample equilibration. Typically, 6~7 hours were needed for complete equilibration.

The diffraction intensity of each multilayer sample was measured during a Θ - 2Θ scan using a He-3 gas-filled 25.4 mm wide pencil detector (GE Reuter-Stokes, Twinsburg, OH). Initial data processing was performed using Reflred, a software written for AND/R. Further data processing, yielding the structure factors, was done with the commercially available package Origin.

The observed structure factors were calculated as:

| (1) |

where I(h) is the intensity of the h-th peak, A(h) is the absorption correction and sin(2Θ) is the Lorentz factor. The absorption correction is given by (24):

| (2) |

where Θ is the Bragg angle, t is the sample thickness, and μ is the linear absorption coefficient of the sample.

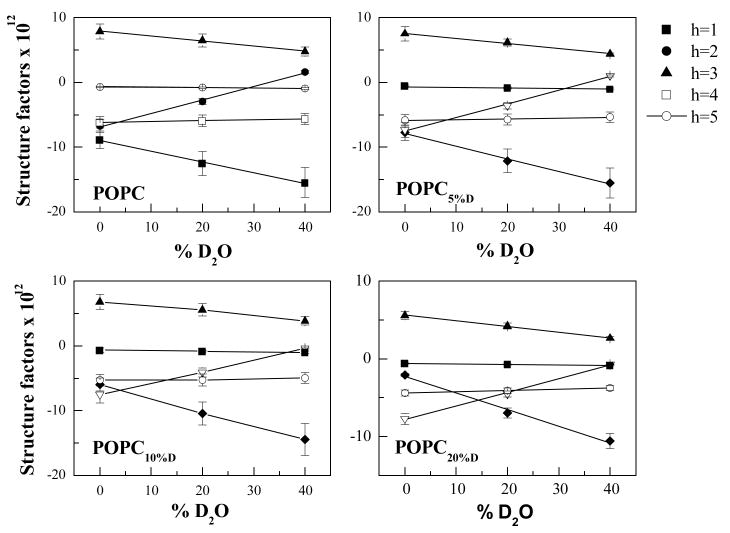

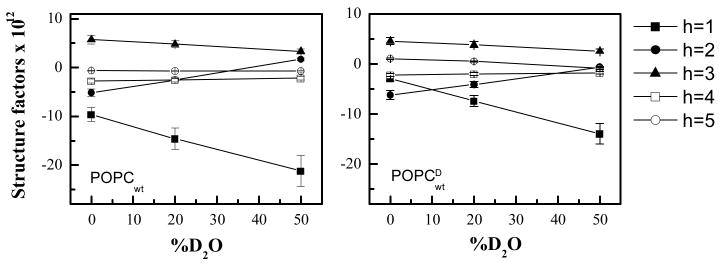

Experimental uncertainties in the structure factors were determined as described below and in (8;19). The random errors in the experimental structure factors were minimized by placing the structure factors for each peptide on a self-consistent arbitrary scale and linearizing them with D2O concentration, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 (16;19). This linear relationship was used to find the “best” statistical estimates of the observed structure factors from parameters of the best-fit straight lines passing through the experimental structure factors (see further details in (16;19)). The best structure factors calculated for 100% H2O were used for structural characterization as described below.

Figure 1.

Absolute structure factors of POPC bilayers with 0, 5%, 10% and 20% POPCD, as a function of D2O mole percent. The experimental uncertainties were calculated as described previously (9). The solid lines are the linear fit to the data. For a given D2O mole percent, a point on the line is the best estimate of the structure factor.

Figure 2.

Absolute structure factors of POPC bilayers with 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain in the absence and presence of 20% POPCD as a function of D2O mole percent.

Absolute scaling: overview

The absolute scattering length density ρ*(z) is the scattering length density per one lipid molecule, given by (25):

| (3) |

where ρ0* is the average scattering length density of the unit cell, f(h) are the measured structure factors on an arbitrary scale, k̄ is the instrumental constant, d is the Bragg spacing, and hobs is the highest observed diffraction order. F(h)=f(h)/k̄ are the absolute structure factors, which are determined solely by the structure and the scattering of the unit cell (16;19).

As discussed previously (26), the instrumental constant k̄ and the absolute structure factors F(h)=f(h)/k̄ can be determined for two samples, with unit cells which are identical except for a few atoms that have large differences in scattering lengths (i.e isomorphous unit cells). Here the absolute structure factors were determined by comparing scattering length density profiles for POPC bilayers, with and without 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain, in the presence and absence of 20% POPCD. Thus, the deuterium in the palmitoyl chain of POPCD served as a “label” that allowed us to both scale the data and determine the probability of finding the palmitoyl chain (i.e. the distribution of the palmitoyl chain) across the bilayer.

Two methods can be used to scale the structure factors: the “real space scaling method” (16) and the “reciprocal space” scaling method (19). The reciprocal space method works for label distributions which are Gaussian. Since we cannot expect that the acyl chain distribution is described by a single Gaussian (in fact, it is known that the DOPC CH2 distribution is described by three Gaussians at 66% RH (18)), the real space scaling method was adopted in this study. This method, first used by Wiener and White to scale DOPC profiles at 66% RH (16), is based on the assumption that the profiles of the isomorphous unit cells are identical in a region that is never visited by the labeled moiety. Two points within this region, z1 and z2, are used in equations describing the profile overlap to determine the instrumental constants for the two isomorphous samples. Since the “label” used in this study was the deuterated palmitoyl chain, z1 and z2 were chosen close to the edge of the unit cell, in the water region of the bilayer. Thus, for the scaling it was assumed that the HC distribution does not reach the edge of the unit cell. This assumption is validated in the results section below.

Because the two profiles are assumed to overlap at z1 and z2, the following two equations hold (16):

| (4) |

| (5) |

In these equations, fA and fB are the structure factors for bilayers with different concentrations of POPCD and kA and kB are the corresponding scale factors. The parameter Δρ* is the scattering contrast introduced by the deuterated POPCD chain. The instrumental constants kA and kB are the unknowns, which are determined from eq. (4) and eq. (5).

Protocol for absolute scaling and for calculation of hydrocarbon core (HC) thickness

The absolute scaling protocol uses the deuterium of the palmitoyl chain in POPCD as the “scaling label” and gives directly the transbilayer distribution of deuterated chain in POPC/POPCD bilayers. This protocol consists of four steps:

Neutron diffraction data are collected for POPC multilayers with various concentrations of POPCD (0, 5, 10, 20%). The structure factors are calculated from the diffraction intensities using equation (1).

The structure factors are placed on the absolute scale using “the real space protocol” overviewed above. Pairs of profiles corresponding to different POPCD concentrations are scaled using equations (4) and (5). The values of z1 and z2 are chosen as 25 and 26 Å from the bilayer center, close to the edge of the unit cell.

The difference between the absolute profiles obtained in Step 2 is calculated. The difference profiles report the transbilayer distribution of the palmitoyl chain in the bilayer.

The width of the HC distribution is calculated as the width of the difference profiles at 1/e of the maximum amplitude (see Figure 4).

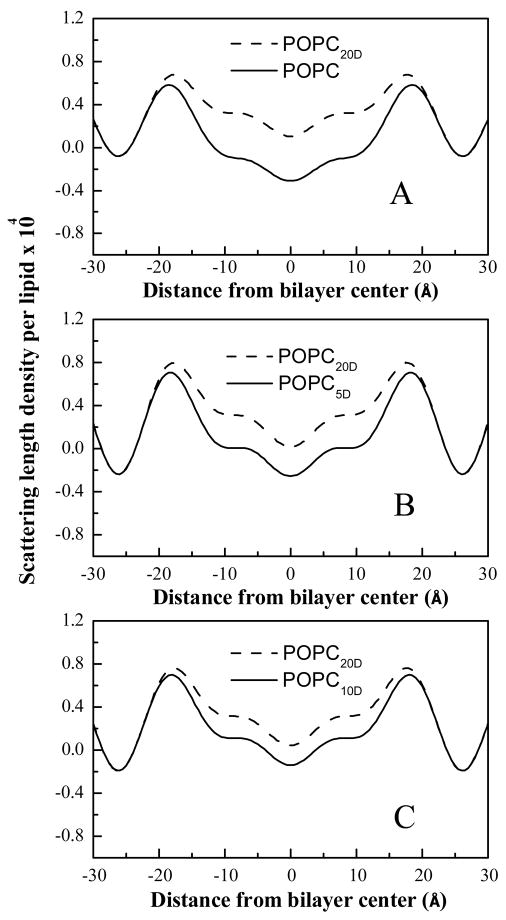

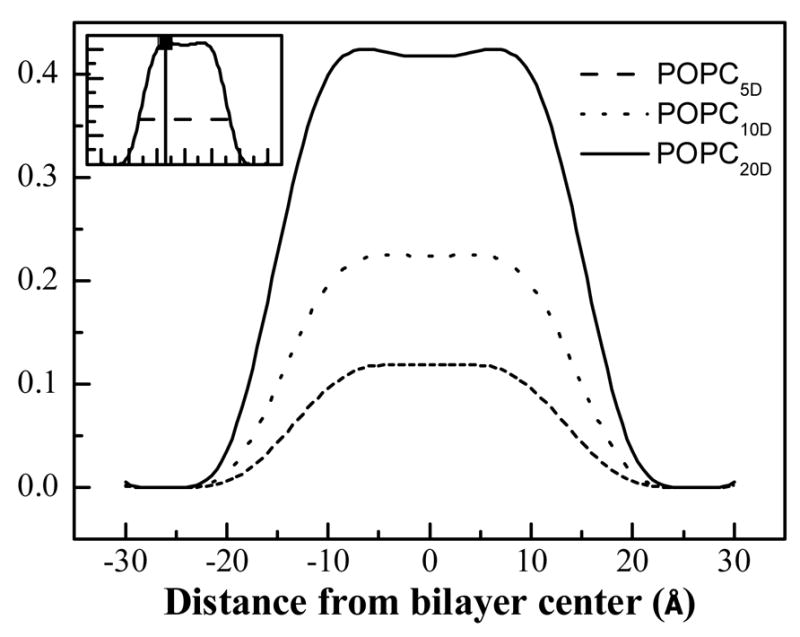

Figure 4.

Difference profiles, obtained via direct subtraction between the pairs of profiles shown in Figure 3. These difference profiles report the palmitoyl chain distribution of POPC. The hydrocarbon core width is defined as the width at 1/e of the maximal amplitude in the difference profiles (inset).

Error analysis

The absolute structure factor uncertainties depend on the uncertainties in the experimental structure factors σ(h) and on the error associated with calculating the scale factors k. The experimental uncertainties σ(h) are determined from the square roots of the integrated peak areas and the background below the peaks, as described previously (8;19).

The error in k can be determined based on the uncertainties σ(h), using the Monte Carlo method of Wiener and White (1992) (We will refer to this method as method I). Noise on the order of σ(h) is added to the structure factors f(h) to create sets of mock structure factors f(h)j. Then the scaling procedure (as described above) is carried out to obtain different estimates of the scale factor, kj, and mock absolute structure factors are calculated as F(h)j =kj f(h)j. Their standard deviation provides one estimate of the absolute structure factor uncertainties.

Alternatively, uncertainties can be calculated if structure factors f(h) are available for more than two POPCD concentrations, as in the case of lipid bilayers here (we will refer to this method as method II). In this case, multiple instrumental constants kl can be obtained for a single set of experimental structure factors f(h). As shown in Figure 3, three instrumental constants kl can be obtained for bilayers composed of 80% POPC and 20% POPCD, by comparing this profile with profiles of POPC bilayers with 0, 5 and 10% POPCD. As a result, three estimates of the absolute structure factors F(h)l = kl f(h) can be obtained and their standard deviation is also a measure of the absolute structure factor uncertainties.

Figure 3.

Absolute scattering length density profiles for POPC bilayers with various POPCD concentrations. (A) 0 and 20 % POPCD (B) 5 and 20 % POPCD (C) 10 and 20 % POPCD. The obvious difference between each pair of profiles is due to the isomorphous replacement of 31 hydrogens with 31 deuterons in the palmitoyl chain of POPCD, giving the palmitoyl chain distribution across the bilayer.

Absolute structure factor uncertainties, calculated using methods I and II, were very similar.

RESULTS

Direct views of the POPC hydrocarbon core distribution

To determine the HC transbilayer distribution in POPC bilayers, multilayers containing different concentrations of POPC and POPCD (with the palmitoyl chain deuterated) were prepared and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. Neutron diffraction experiments were carried out at the AND/R at NIST, and structure factors were calculated using equation (1). Absolute scattering length density profiles were calculated using equation (3). Structure factors and scattering length density profiles were placed on the absolute scale as described in Materials and Methods, by choosing z1 and z2 as 25 and 26 Å from the bilayer center, close to the edge of the unit cell. Figures 1 and 2 shows the plots of the absolute structure factors as a function of D2O content, and Table 1 reports the “best” absolute structure factors for 100% H2O. Figure 3 compares the absolute scattering length density profiles for POPC bilayers with 0, 5, 10 and 20 mole% POPCD. The difference between the profiles is due to the substitution of a fraction of POPC with POPCD (i.e., the isomorphous replacement of 31 hydrogens with 31 deuterons in the palmitoyl chain). Thus, the difference between the profiles, shown in Figure 4, gives the transbilayer distribution of the palmitoyl chain. The amplitudes of the three difference profiles in Figure 4, which reflect the scattering difference due to the addition of 5, 10, and 20% POPCD, scale with the difference in POPCD concentration.

Table 1.

The “best” absolute structure factors and their experimental uncertainties for POPC multilayers with 0%, 5%, 10% and 20% POPCD. Structure factors were calculated as described in Materials and Methods, by comparing the scattering profiles of multiple pairs of samples with different concentrations of POPCD. The reported values are the average of 3 independent calculations of the absolute structure factors along with the standard deviation. For example, three scale factors were obtained for POPC bilayers, by comparing the pure POPC profile with profiles in the presence of 5%, 10% and 20% POPCD,

| ha | POPC | 5% POPCD | 10% POPCD | 20% POPCD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −8.99±1.35 | −7.91 ±1.18 | −6.03 ± 1.02 | −2.24± 0.17 |

| 2 | −6.85±1.02 | −7.50 ±1.12 | −7.54 ± 1.28 | −7.70± 0.62 |

| 3 | 7.91±1.19 | 7.59 ±1.14 | 6.87 ± 1.16 | 5.54± 0.44 |

| 4 | −6.17±0.92 | −5.89 ±0.88 | −5.34 ± 0.90 | −4.33± 0.35 |

| 5 | −0.64±0.10 | −0.72 ±0.11 | −0.66±0.11 | −0.59 ± 0.05 |

|

| ||||

| d (Å)b | 52.4 ± 0.3 | 52.7 ± 0.3 | 52.3 ± 0.3 | 52.3 ± 0.3 |

The widths of the difference profiles shown in Figure 4 were calculated as the widths at 1/e of the maximum amplitude of the profiles (see inset). These widths were obtained by comparing pairs of POPC profiles in the presence of different POPCD concentrations. As seen in Table 3, the six independent calculations of the HC width of POPC fall within ± 2 Å around the average value of 33 Å.

Table 3.

Hydrocarbon core widths obtained by comparing pairs of profiles of POPC bilayers with either 0, 5, 10 or 20 mole% POPCD. The HC width is defined as the width at 1/e of the hydrocarbon core profile maximum. Also shown is the width in the presence of 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain, which falls within the range observed for pure lipid bilayers. Thus, no change in HC width can be detected upon peptide incorporation.

| Width(Å) | 0–5% | 0–10% | 0–20% | 5–10% | 5–20% | 10–20% | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POPC | 30.0±1.7 | 31.6±2.2 | 33.2±2.0 | 34.6±2.1 | 34.8±1.8 | 34.8±1.8 | 33±2 |

| POPC+FGFR3 | 31.4±1.9 |

The scaling procedure presented in Materials and Methods is based on the assumption that the edge of the unit cell is not visited by the palmytic methylene moieties of POPC. All the results shown are for z1 = 25 Å and z2 = 26 Å from the bilayer center. However, we also varied these values between 26.2 and 22.0 Å and obtained very similar results (instrumental constants within 5%, data not shown). Thus, the results of the scaling are not sensitive to the choice of z1 and z2 within 4 Å from the edge of the unit cell. Furthermore, the profiles virtually overlap (i.e. the difference profiles are practically zero) within 7 Å from the edge of the unit cell (see Figure 4, not all results shown). These results demonstrate the validity of the scaling procedure given in Materials and Methods, as well as the validity of the underlying assumption that the HC distribution vanishes close to the edge of the unit cell.

The hydrocarbon core (HC) distribution in the presence of FGFR3 TM domain

Next we calculate the HC distribution along the bilayer normal in the presence of FGFR3 TM domain using the scaling protocol given in Materials and Methods.

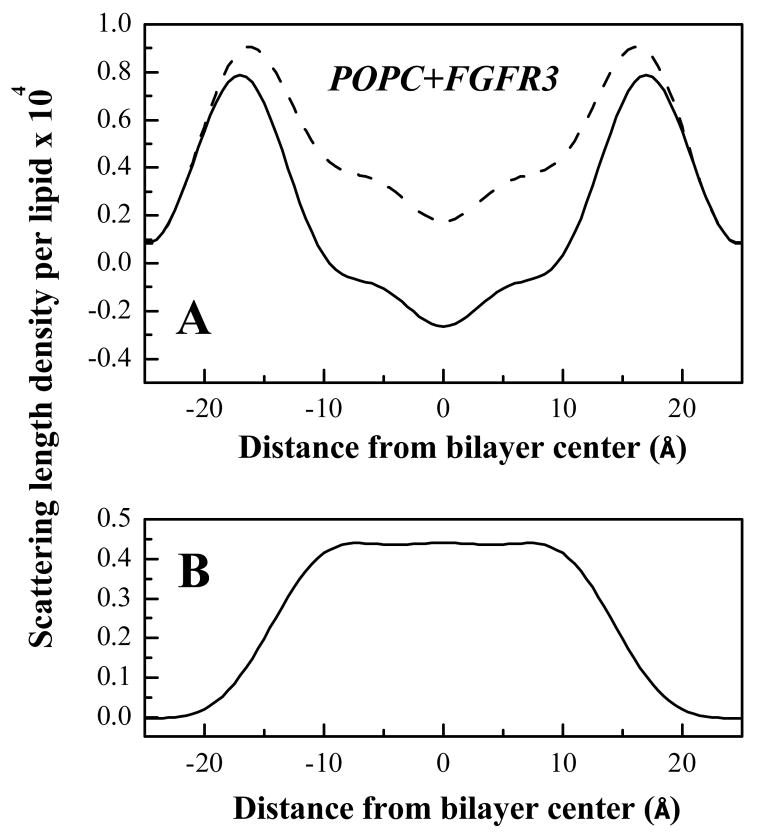

Two multilayer samples were characterized: (1) 96 mole% POPC+4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain and (2) 96 mole% (80 mole% POPC and 20 mole% POPCD) + 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain. Structure factors (Table 2) and profiles (Figure 5) were placed on the absolute scale as described in Materials and Methods.

Table 2.

The “best” absolute structure factors of POPC multilayers with 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain in the absence and presence of 20% POPCD. Structure factors and their experimental uncertainties were calculated using the protocol described in Materials and Methods.

| ha | POPC+FGFR3c | POPC+FGFR3 | 20% POPCD +FGFR3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −10.13±1.50 | −10.43±1.53 | −3.02± 0.45 |

| 2 | −5.40±0.81 | −5.59±0.82 | −6.36± 0.95 |

| 3 | 6.03±0.91 | 6.17±0.93 | 4.70 ± 0.71 |

| 4 | −2.87±0.43 | −2.95±0.45 | −2.22 ± 0.27 |

| 5 | −0.66±0.61 | −0.67±0.62 | 0± 0.35 |

|

| |||

| d(Å)b | 49.5± 0.3 | 49.5± 0.3 | 49.3 ± 0.3 |

Diffraction order.

Bragg spacing.

Structure factors, scaled in a previous study (9) using the reciprocal space method and deuterated amino acids as the “scaling label”. The new scaling method gives similar results.

Figure 5.

(A) Absolute scattering length density profiles for POPC bilayers with 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain in the presence (dashed line) and absence (solid line) of 20 mole% POPCD. (B) Difference profile showing the palmitoyl chain distribution in the presence of 4 mole% FGFR3 TM domain.

In our previous work (26), structure factors for POPC multilayers with 4 mole % FGFR3 TM domain were scaled using specifically deuterated amino acids and the reciprocal space scaling method (results shown in Table 2, column 1). Here, the structure factors were scaled using the deuterated palmitoyl chain as the “label” and the real space scaling method (Table 2, column 2 and 3). The comparison between columns 1 and 2 in Table 2 demonstrates that the two scaling methods give very similar results, further confirming that the scaling procedure described in Materials and Methods is robust. This procedure also gives directly the distribution of the palmytoyl chain of POPCD.

Figure 5 shows the absolute neutron scattering length density profiles for POPC bilayers with 4% mole % FGFR3 TM domain in the presence and absence of 20 mole% POPCD. The difference profile, obtained by simple subtraction, shows the palmitoyl chain distribution. The 1/e width of the palmitoyl chain distribution, giving the HC thickness, is ~31.4 Å (see Table 3). This value is similar to the 33 ± 2 Å value obtained in the absence of the peptide.

DISCUSSION

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange combined with neutron scattering is a powerful tool in structural biology (27;28). This exchange does not introduce structural perturbations and allows precise determination of the spatial distribution of the deuterium label. This technique is used with both small angle neutron scattering (SANS) (29), to gain structural information about macromolecular structure and assembly in solution (30), and with diffraction/reflectivity, to elucidate structures within multilayers (31;32). In bilayers or lipid multilayers, specific deuteration of amino acids can provide valuable insights into protein disposition in the bilayer (33–36). Specific deuteration of chosen amino acids is easy to implement if the peptides are produced via solid phase peptide synthesis, where any Fmoc amino acid can be substituted with its deuterated version during production. In such experiments, the transbilayer distribution of a deuterated amino acids is given by a Gaussian distribution, and the center of the Gaussain points to the position of the amino acid within the bilayer thickness. Work from several laboratories has revealed that this approach to structure determination is feasible (33–36), and can be successfully used to test predictions for membrane embedded segments based on hydrophobicity scales (26) and to evaluate various contributions to protein folding in membrane environments (23).

Since membrane protein folding occurs within the context of the native bilayer, structural studies of bilayers with and without proteins have proven invaluable in deciphering the physical principles behind membrane protein stability (1;2;37). Yet, complete structures of bilayers are difficult to obtain. An obvious question that arises is whether an approach that is similar to using deuterated amino acids, that is, using specifically deuterated lipids, would be a useful tool to study bilayer structures. There are commercially available lipids that are either fully deuterated or have deuterated acyl chains. Such lipids are widely used in NMR studies, but are not yet fully utilized in neutron diffraction studies. Here we use POPC lipids with one deuterated acyl chain to obtain the distribution of the hydrocarbon core, and ultimately the thickness of the hydrocarbon core at 76% RH. The data can be compared to previous measurements of fully hydrated POPC bilayers, such as the ones of Kucerka et. al. (38). These measurements, based on less direct structural characterization of the hydrocarbon core of POPC, have yielded a thickness value of 27.1 Å. The hydrocarbon core thickness is known to decrease when the hydration is increased, by at least 3 Å (19), and thus the measurements at low and high hydration appear consistent with each other. Furthermore, our result for the POPC hydrocarbon core thickness at 76% RH is similar to the hydrocarbon thickness of DOPC bilayers at 66% RH, 32 Å (18), obtained within the context of the complete DOPC structure.

Here we use deuterated lipids to monitor the HC in the presence of a TM peptide corresponding to the TM domain of a human receptor tyrosine kinase, the TM domain of FGFR3, and we see no change in the HC thickness upon peptide incorporation (Table 3). The peptide disposition inside the bilayer has been previously characterized using oriented circular dichroism and neutron diffraction (26). It is highly helical and transmembrane, and the helix tilt with respect to the bilayer normal does not exceed 20 degrees. The hydrophobic length of the helix can be calculated as the number of consecutive hydrophobic amino acids in the sequence (24) times the rise per residue 1.5 Å, i.e., 24 × 1.5 Å = 36 Å, similar to the measured value of 33 ± 2 Å. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first such study of the effect of a human TM sequence on bilayer structure, which underscores the need for simple structural methods that are applicable for fluid bilayer environments. We believe that the simple experimental approach presented here will aid future structural studies of proteins incorporated into lipid bilayers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. M. Mihailescu and D. Worcester for their help with neutron data collection and processing, and for useful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grant GM068619 (K.H.). We acknowledge the support of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, U.S. Department of Commerce, and the Cold Neutrons for Biology and Technology (CNBT) program funded by the National Institutes of Health under grant RR14812- and the Regents of the University of California, for providing the neutron research facilities used in this work.

Reference List

- 1.White SH, Wimley WC, Ladokhin AS, Hristova K. Protein folding in membranes: Pondering the nature of the bilayer milieu. Biol Skr Dan Selsk. 1998;49:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 2.White SH, Ladokhin AS, Jayasinghe S, Hristova K. How membranes shape protein structure. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32395–32398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White SH, Wimley WC. Membrane protein folding and stability: Physical principles. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struc. 1999;28:319–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacKenzie KR. Folding and stability of alpha-helical integral membrane proteins. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1931–1977. doi: 10.1021/cr0404388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nagle JF, Tristram-Nagle S. Structure of lipid bilayers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1469:159–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00016-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiener MC, Suter RM, Nagle JF. Structure of the fully hydrated gel phase of dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine. Biophys J. 1989;55:315–325. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82807-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gandhavadi M, Allende D, Vidal A, Simon SA, McIntosh TJ. Structure, composition, and peptide binding properties of detergent soluble bilayers and detergent resistant rafts. Biophys J. 2002;82:1469–1482. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75501-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hristova K, Wimley WC, Mishra VK, Anantharamaiah GM, Segrest JP, White SH. An amphipathic α-helix at a membrane interface: A structural study using a novel x-ray diffraction method. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:99–117. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hristova K, Dempsey CE, White SH. Structure, location, and lipid perturbations of melittin at the membrane interface. Biophys J. 2001;80:801–811. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heller WT, Waring AJ, Lehrer RI, Harroun TA, Weiss TM, Yang L, Huang HW. Membrane thinning effect of the β-sheet antimicrobial protegrin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:139–145. doi: 10.1021/bi991892m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harroun TA, Heller WT, Weiss TM, Yang L, Huang HW. Experimental evidence for hydrophobic matching and membrane-mediated interactions in lipid bilayers containing gramicidin. Biophys J. 1999;76:937–945. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77257-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wiener MC, White SH. Fluid bilayer structure determination by the combined use of X-ray and neutron diffraction. I. Fluid bilayer models and the limits of resolution. Biophys J. 1991;59:162–173. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82208-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagle JF, Wiener MC. Structure of fully hydrated bilayer dispersions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;942:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(88)90268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsaras J, Stinson RH, Davis JH, Kendall EJ. Location of Two Antioxidants in Oriented Model Membranes - Small- Angle X-Ray Diffraction Study. Biophys J. 1991;59:645–653. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82280-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wiener MC, White SH. Fluid bilayer structure determination by the combined use of X-ray and neutron diffraction. II. “Composition-space” refinement method. Biophys J. 1991;59:174–185. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82209-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiener MC, White SH. Transbilayer distribution of bromine in fluid bilayers containing a specifically brominated analog of dioleoylphosphatidylcholine. Biochemistry. 1991;30:6997–7008. doi: 10.1021/bi00242a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiener MC, King GI, White SH. Structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer determined by joint refinement of x-ray and neutron diffraction data. I. Scaling of neutron data and the distribution of double-bonds and water. Biophys J. 1991;60:568–576. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82086-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiener MC, White SH. Structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer determined by joint refinement of x-ray and neutron diffraction data. III. Complete structure. Biophys J. 1992;61:434–447. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81849-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hristova K, White SH. Determination of the hydrocarbon core structure of fluid dioleoylphosphocholine (DOPC) bilayers by x-ray diffraction using specific bromination of the double-bonds: Effect of hydration. Biophys J. 1998;74:2419–2433. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77950-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwamoto T, You M, Li E, Spangler J, Tomich JM, Hristova K. Synthesis and initial characterization of FGFR3 transmembrane domain: Consequences of sequence modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1668:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li E, Hristova K. Imaging FRET Measurements of Transmembrane Helix Interactions in Lipid Bilayers on a Solid Support. Langmuir. 2004;20:9053–9060. doi: 10.1021/la048676l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.You M, Li E, Wimley WC, Hristova K. FRET in liposomes: measurements of TM helix dimerization in the native bilayer environment. Analytical Biochemistry. 2005;340:154–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han X, Hristova K, Wimley WC. Protein folding in membranes: Insights from neutron diffraction studies of a membrane beta-sheet oligomer. Biophys J. 2008;94:492–505. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Worcester DL, Franks NP. Structural analysis of hydrated egg lecithin and cholesterol bilayers. II. Neutron diffraction. J Mol Biol. 1976;100:359–378. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(76)80068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobs RE, White SH. The nature of the hydrophobic binding of small peptides at the bilayer interface: Implications for the insertion of transbilayer helices. Biochemistry. 1989;28:3421–3437. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han X, Mihailescu M, Hristova K. Neutron diffraction studies of fluid bilayers with transmembrane proteins: Structural consequences of the achondroplasia mutation. Biophys J. 2006;91:3736–3747. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.092247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaccai G. Moist and soft, dry and stiff: a review of neutron experiments on hydration-dynamics-activity relations in the purple membrane of Halobacterium salinarum. Biophys Chem. 2000;86:249–257. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(00)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trewhella J, Gallagher SC, Krueger JK, Zhao J. Neutron and X-ray solution scattering provide insights into biomolecular structure and function. Science Progress. 1998;81:101–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petoukhov MV, Svergun DI. Analysis of X-ray and neutron scattering from biomacromolecular solutions. Cur Opinion Struc Biol. 2007;17:562–571. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pencer J, Krueger S, Epand R, Katsaras J. Detection of submicron-sized domains or so-called “rafts” in membranes by small-angle neutron scattering. Biophysical Journal. 2005;88:76A. doi: 10.1140/epje/e2005-00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meuse CW, Krueger S, Majkrzak CF, Dura JA, Fu J, Connor JT, Plant AL. Hybrid bilayer membranes in air and water: Infrared spectroscopy and neutron reflectivity studies. Biophys J. 1998;74:1388–1398. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77851-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krueger S, Meuse CW, Majkrzak CF, Dura JA, Berk NF, Tarek M, Plant AL. Investigation of hybrid bilayer membranes with neutron reflectometry: Probing the interactions of melittin. Langmuir. 2001;17:511–521. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradshaw JP, Darkes MJM, Harroun TA, Katsaras J, Epand RM. Oblique membrane insertion of viral fusion peptide probed by neutron diffraction. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6581–6585. doi: 10.1021/bi000224u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dante S, Hauss T, Dencher NA. beta-amyloid 25 to 35 is intercalated in anionic and zwitterionic lipid membranes to different extents. Biophys J. 2002;83:2610–2616. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75271-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hauss T, Dante S, Haines TH, Dencher NA. Localization of coenzyme Q(10) in the center of a deuterated lipid membrane by neutron diffraction. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Bioenergetics. 2005;1710:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradshaw JP, Darkes MJM, Katsaras J, Epand RM. Neutron diffraction studies of viral fusion peptides. Physica B. 2000;276:495–498. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li E, Hristova K. Role of receptor tyrosine kinase transmembrane domains in cell signaling and human pathologies. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6241–6251. doi: 10.1021/bi060609y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kucerka N, Tristram-Nagle S, Nagle JF. Structure of fully hydrated fluid phase lipid bilayers with monounsaturated chains. J Membr Biol. 2006;208:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00232-005-7006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]