Summary

Although many proteins can misfold into a self-seeding amyloid-like conformation1, only six are known to be infectious, i.e. prions; [PSI+], [PIN+], [URE3], [SWI+] and [HET-s] cause distinct heritable physiological changes in fungi2–4, while PrPSc causes infectious encephalopathies in mammals5. It is unknown if “protein-only” inheritance is limited to these exceptional cases, or represents a widespread mechanism of epigenetic control. Towards this goal, we now describe a new prion formed by the Cyc8 (Ssn6) protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Analogous to other yeast prions, transient over-production of a glutamine-rich region of Cyc8 induced a heritable dominant cyc8− phenotype that is transmitted cytoplasmically and dependent on the chaperone Hsp104 and the continued presence of the Cyc8 protein. The evolutionarily conserved Cyc8-Tup1 global transcriptional repressor complex6 forms one of the largest gene regulatory circuits, controlling the expression of over 7% of yeast genes7. Our finding that Cyc8 can propagate as a prion, together with a recent report that Swi1 of the Swi-Snf global transcriptional regulatory complex also has a prion form4, shows that prionization can lead to mass activation or repression of yeast genes and is suggestive of a link between the epigenetic phenomena of chromatin remodeling and prion formation.

We previously identified 11 yeast proteins whose over-expression facilitated the de novo appearance of the [PSI+] prion in an unbiased screen: Cyc8, Lsm4, New1, Nup116, Pin2, Pin3, Pin4, Ste18, Swi1, Ure2, Yck18. As the appearance of [PSI+] was also facilitated by the presence of the established prions [PIN+] or [URE3], and the protein determinant of [URE3] was among the 11 proteins identified, we hypothesized that some of the other 10 proteins could also form prions8. This was further supported by the observation that all 11 proteins contained domains with an unusually high glutamine and asparagine (QN) content. Such QN-rich domains are found in all known yeast prions as part of the “prion-domain” required for prion formation and propagation3,4. Here we show that one of these proteins, Cyc8 can indeed form a prion.

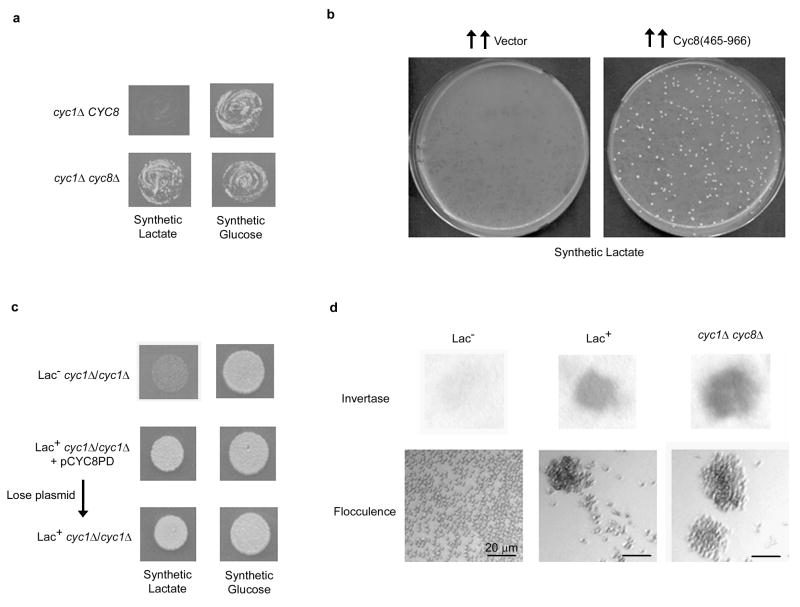

Mutations in CYC8 cause slow growth, defects in sporulation and mating, high iso-2-cytochrome c, flocculation and invertase de-repression6,9,10. Since inactivation of Cyc8 either by mutation or prion formation should manifest as a loss-of-function phenotype2, we used the cyc8 mutant phenotype of increased levels of iso-2-cytochrome c9 to initially select for the prion. Yeast needs cytochrome c to grow on the non-fermentable carbon source lactate9. As 95% of a cell’s cytochrome c (iso-1) is encoded by CYC1, cyc1 mutants cannot grow if lactate is the only carbon source. However, a cyc1 mutant can grow on lactate if the level of iso-2-cytochrome c, encoded by CYC7, is increased by inactivating the Cyc8-Tup1 repressor complex that represses synthesis of iso-2-cytochrome7,9 (Figure 1a). Thus, to screen for cells propagating a Cyc8 prion, we selected for cyc1Δ yeast cells that grew well on lactate.

Figure 1. Over-expression of Cyc8’s prion-like domain induces a cyc8 mutant phenotype.

(a) As expected9, the double cyc1Δ cyc8Δ mutant (L-3045) grows better on lactate than a single cyc1Δ CYC8 mutant (L-2762). (b) Following over-expression of Cyc8’s prion-like QN-rich domain (aa: 465–966) in L-2729 (MATa/MATa cyc1-363/cyc1::kan) from pCYC8PD (2μ URA3 leu2d) on synthetic glucose-Leu medium29, ~107 cells per plate were spread on synthetic lactate (right) along with similarly treated controls with the empty vector, pHR81 (left). Plates were incubated for 15 days. (c) Even after Lac+ derivatives of pCYC8PD transformants of L-2729 obtained as in (a) were cured of pCYC8PD on 5-fluoroorotic acid medium30, they grew on lactate and (d) exhibited constitutive invertase activity and higher flocculation than Lac− L-2729 derivatives.

The de novo appearance of a prion is generally a rare event, but the transient overproduction of the protein’s prion domain greatly enhances its chance of misfolding into a prion2,3. Thus, we over-expressed the C-domain of Cyc8 (aa: 465–966) which is not essential for Cyc8 function and contains a highly Q-rich segment (52% of aa: 491–668 are Q)11,12. This domain organization is reminiscent of the known yeast prion proteins, where the functional and QN-rich prion domains are separate and distinct3. While lactate+ (Lac+) colonies appeared spontaneously in a cyc1Δ haploid strain presumably due to recessive spontaneous Lac+ mutations e.g. cyc8 mutations9, we found that overproduction of Cyc8(465–966) enhanced the appearance of Lac+ derivatives by more than 100-fold (data not shown). When the screen was repeated in a cyc1Δ/cyc1Δ diploid, Lac+ derivatives appeared at a frequency of 1.7 ± 0.4 × 10−5 (n=3), while virtually no Lac+ derivatives were seen in control plates without Cyc8 over-expression (Figure 1b) because recessive spontaneous Lac+ mutations were hidden in the diploid. We call the proposed, Lac+, prion form of Cyc8, [OCT+]. Since inactivation of Cyc8, either by mutation or prion formation, would inhibit sporulation of MATa/MATα diploid cells6 and compromise the ability of MATα/MATα cells to mate6, we isolated [OCT+] candidates from a cyc1Δ/cyc1Δ MATa/MATa diploid, which can mate and thus allow genetic manipulations to examine prion propagation. We examined three independent [OCT+] isolates from MATa/MATa cells and even after loss of the Cyc8(465–966) encoding plasmid, these [OCT+] candidates remained Lac+ (Figure 1c) and exhibited additional phenotypes previously associated with Cyc8’s loss-of-function6,10: higher levels of invertase activity even under glucose-repressed conditions (constitutive expression) and increased flocculence compared to Lac− cells (Figure 1d), thereby indicating de-repression of SUC2 and FLO1 genes respectively. All subsequent analyses were done with one of these [OCT+] derivatives following loss of the Cyc8(465–966) encoding plasmid.

While the Mendelian mutations in cyc8, documented so far, are recessive9,10, an [OCT+] prion should be dominant over an [oct−] state since the [OCT+] Cyc8 in the zygote should convert the [oct−] Cyc8 into the prion form. Indeed, when MATa/MATa [OCT+] candidates were crossed to an [oct−] cyc1Δ haploid the resulting triploids were [OCT+]: they grew on lactate and showed constitutive invertase activity (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. [OCT+] phenotypes are dominant.

(a) [OCT+] phenotypes are retained when crossed to [oct−]. Subclones of [OCT+] or [oct−] L-2729 (MATa/MATa cyc1Δ/cyc1Δ) derivatives were crossed to L-899 (MATα his1 trp5 cyc1Δ CYC8 [oct−]). All triploids made with an [OCT+] L-2729 parent but none made with the [oct−] derivatives behaved like [OCT+]: they were Lac+ and had constitutive invertase activity. (b) Full-length Cyc8 protein fails to complement [OCT+] whereas, a Cyc8 fragment (aa: 1–453) lacking its QN-rich domain does. [OCT+] cells transformed with pRT8111 or pCYC8(1–453) plasmids, respectively expressing the complete Cyc8 protein or a Cyc8 fragment (aa: 1–453), were tested for restoration of Cyc8’s function (upper) by lactate growth assay or invertase activity. [OCT+] transformants with pCYC8(1–453) regained invertase activity after the plasmid was eliminated showing a masking of the phenotype and not a spontaneous loss. pRT81 expressed a functional Cyc8 since it successfully repressed invertase activity in L-3043 (cyc8Δ) and as opposed to the empty vector control pHR81(lower).

Furthermore, when [OCT+] candidates were transformed with a plasmid expressing functional Cyc8 (kind gift of R. Trumbly), all transformants remained [OCT+]: they had Lac+, high invertase phenotypes (Figure 2b). This observed lack of restoration of Cyc8 function in [OCT+] cells is consistent with the expected inactivation of the plasmid encoded Cyc8 by sequestration into prion aggregates. In controls, the same plasmid restored function to a cyc8 deletion (Figure 2b). In contrast, when [OCT+] cells were transformed with a plasmid expressing the N-terminal functional fragment (aa: 1–453) of Cyc812 lacking the QN-rich carboxyl terminal region, Cyc8 function was successfully restored, as revealed by the invertase assay (Figure 2b). These data are consistent with the QN-rich region of Cyc8 being its prion determining domain which predicts that a Cyc8 functional fragment lacking the QN-rich region would fail to join the prion aggregates in [OCT+] and consequently restore Cyc8 function.

As the Hsp104 chaperone that dissolves non-specific protein aggregates, is indispensable for the heritability of all known yeast prions3,4,13, we tested if it is required for the maintenance of [OCT+]. We transiently inhibited Hsp104 by growing [OCT+] cells on medium containing 4 mM guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl)3,14. Indeed, the [OCT+] cells lost their ability to utilize lactate and ferment sucrose after growth on GuHCl but not when grown for similar generations without GuHCl (Figure 3a). These [oct−] cells, obtained after GuHCl treatment of [OCT+], remained [oct−], even when subcloned for several passages on GuHCl-less glucose-rich medium, as they did not spontaneously give rise to Lac+ colonies when spread on synthetic lactate plates (Supplementary Figure S1 left). Furthermore, as expected of a prion phenotype2, but unlike viruses or other nucleic acid elements, [OCT+] could be induced to re-appear in the cured [oct−] cells (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 3. Inheritance of [OCT+] depends on Hsp104.

(a) [OCT+] is cured by growth on guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl). Twenty-one subclones of L-2729 [OCT+] were transferred three times in a patch on complex media (YPD) + 4 mM GuHCl or for control on just YPD. Subsequently patches were tested for growth on synthetic lactate (and glucose for control) and invertase activity to score for [OCT+]. Growth on complex glycerol medium showed that they retained mitochondria. (b) Expression of dominant negative HSP104-KT cures cells of [OCT+]. Transformants of [OCT+] L-2729 with pGAL-HSP104-KT, encoding HSP104-KT under a GAL promoter, or with an empty vector control (pRS316) were transferred twice as patches on plasmid selective 2% galactose medium (+) to induce the expression of HSP104-KT, or on plasmid selective 2% glucose (−) for a no expression control. They were then grown on glucose to turn-off HSP104-KT expression and were finally tested for their [OCT+] status by measuring growth on synthetic lactate (and control glucose) medium and invertase activity.

We also blocked Hsp104’s activity in [OCT+] cells for a few generations by expressing a dominant negative HSP104-KT allele13. [OCT+] cells lost their ability to utilize lactate and ferment sucrose following transient expression of HSP104-KT, while controls in which HSP104-KT was never expressed remained [OCT+] (Figure 3b). Thus, sustained Hsp104 activity is essential for propagation of [OCT+], strongly suggesting that its inheritance is protein-based.

While over-expression of Hsp104 cures cells of [PSI+]13, it did not cure cells of [OCT+]: 14 transformants of an [OCT+] strain with plasmid pES5 (a kind gift of S. Lindquist) encoding Hsp104 from a GAL promoter remained [OCT+] even after Hsp104 was over-produced by growth on 2% galactose medium (data not shown). Possibly, the [OCT+] prion aggregates are similar to the [URE3], [PIN+] and [SWI+] aggregates that are also not cured by elevated Hsp104 levels3,4.

Since prions are infectious proteins, the transfer of cytoplasm without genetic material (cytoduction) from a prionbearing donor cell can infect a recipient that expresses the corresponding protein. To ask if [OCT+] could be transmitted by cytoduction, [OCT+] and control isogenic [oct−] cells were crossed to an [oct−] recipient that contained the kar1-Δ15 mutation that inhibits karyogamy15 but permits cell fusion and cytoplasmic mixing. Cells that budded off from these heterokaryons and contained only the recipient haploid nucleus (i.e. cytoductants) were selected and tested for the ability to grow on lactate: 24 of 57 vs. 0 of 63 cytoductants tested from the [OCT+] and [oct−] crosses respectively grew on lactate. The Lac+ phenotype in these cytoductants was associated with constitutive invertase activity, was dominant and was cured by growth on 4 mM GuHCl (data not shown), indicating that [OCT+] had been transmitted via cytoduction. Since the CYC8 allele in the recipient was tagged with GFP we had hoped to score for [OCT+] cytoductants directly by observing fluorescent foci (dots) in [OCT+] but not [oct−] cells, but the low intensity of the GFP fluorescence thwarted such differentiation.

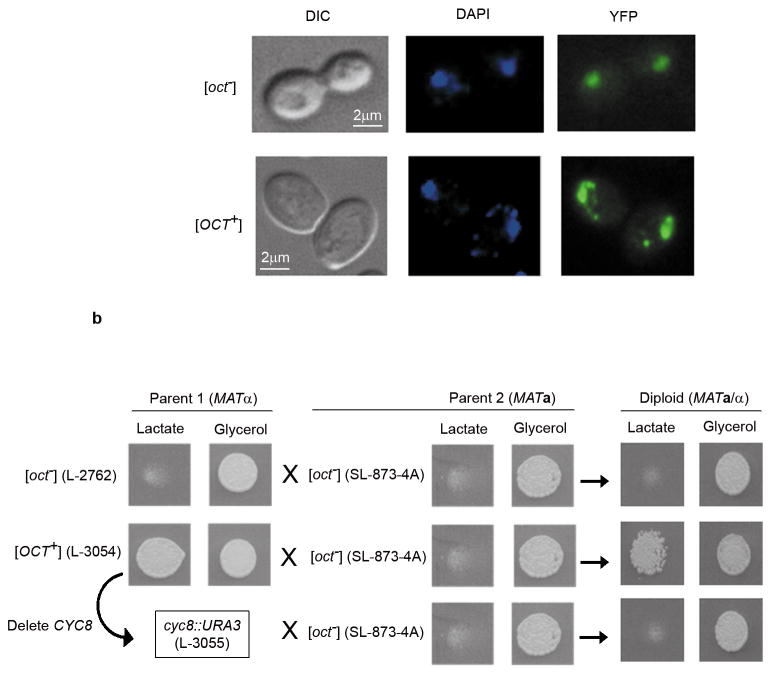

However, when a Cyc8-YFP fusion protein16 was over-expressed at a modest level from a copper inducible plasmid pCUP-CYC8YFP (a kind gift of S. Lindquist), in addition to the diffuse nuclear fluorescence in both [OCT+] and [oct−] cells, punctate fluorescent dots appeared in the cytoplasms of [OCT+] but not [oct−] cells (Figure 4a). This is suggestive of a prion-like decoration of pre-formed Cyc8 aggregates by Cyc8-YFP in the cytoplasms of the [OCT+] cells and is analogous to results seen with other yeast prions3,4,17. However, since even in [oct−] cells, Cyc8 is part of large detergent resistant protein complexes, we were unable to identify detergent resistant [OCT+]-specific prion aggregates (data not shown).

Figure 4. [OCT+] is a prion form of the Cyc8 protein.

(a) Cyc8-YFP aggregates as cytoplasmic punctate dots in [OCT+] cells. [OCT+] and [oct−] derivatives of L-2729 transformed with pCUP-CYC8YFP were grown for 5 h in plasmid inducing 20 μM Cu2+ medium. Diffuse Cyc8-YFP fluorescence was seen in both [OCT+] and [oct−] cell’s nuclei as visualized by DAPI counter-staining. Punctate fluorescent foci appeared in the cytoplasms of ~10–20% of the [OCT+] cells but not in the [oct−] controls. However, increased Cyc8-YFP induction eventually caused cytoplasmic and nuclear fluorescent aggregates to also appear in [oct−] cells (data not shown). Analogous de novo appearance of fluorescent aggregates has been observed for other prions following prolonged over-expression of the prion-domain fused to GFP in cells lacking the prion3,17. (b) Transient loss of Cyc8 protein eliminates [OCT+]. CYC8 was first replaced with URA3 in an [OCT+] haploid (L-3054) and retention of [OCT+] was tested by assaying growth on lactate after restoring CYC8 by crossing to cyc1Δ CYC8 (SL873- 4A). Nine such individual cyc8::URA3 replacements that we tested had all lost [OCT+]. Diploids from crosses of SL873-4A to isogenic [OCT+] (L-3054) and [oct−] (L-2762) strains were used as positive and negative controls. The possibility that transformation itself cured [OCT+] was eliminated because 40 Ura+ transformants of [OCT+] (L-3054) with pRAA9, a lys2 URA3 integration plasmid linearized by BstEII to direct its integration into LYS226, all retained [OCT+] (data not shown).

Next, we tested if [OCT+] cell-lysates could infect an [oct−] cell. Pre-cleared cell-lysate obtained from an [OCT+] strain was introduced into [oct−] cells by co-transformation with a centromeric LEU2 plasmid (pRS315) as described previously for other prions19,20. Leu+ transformants were assayed for growth on lactate. When the cell extracts were respectively made from [OCT+] and [oct−] cells, 7 out of 170 vs 0 out of 160 Leu+ transformants became Lac+. These Lac+ transformants also exhibited high invertase activity and both phenotypes were cured on GuHCl (data not shown). The observed transformation efficiency of 4% for [OCT+], which is within the range of 3–11% infection previously observed for variants of [PIN+]18, indicates infection.

If [OCT+] is indeed a prion form of the Cyc8 protein, then transient loss of the Cyc8 protein should cure cells of [OCT+]. As predicted, when we replaced CYC8 with URA3 in an [OCT+] strain, 9 of 9 independent deletions, but 0 of 40 controls, lost [OCT+]. Deletions were scored for [OCT+] after restoring Cyc8 protein by crossing them to an [oct−] CYC8cyc1Δ strain (Figure 4b).

As the Cyc8 protein represses transcription of numerous yeast genes6,7, its inactivation by prion formation is expected to de-repress these genes. Indeed, lacZ fusions showed that expression of two Cyc8 regulated genes, CYC7 and ANB1 is de-repressed in [OCT+] cells (Figure 5a). Furthermore, as measured with real-time PCR, the mRNA levels of five Cyc8-repressed genes7, CYC7, RNR3, FLO1, ANB1, and SUC2, were elevated in [OCT+] cells but less than a cyc8Δ control suggesting a partial loss-of Cyc8’s function in [OCT+] cells (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. [OCT+] cells exhibit de-repression of genes repressed by the Cyc8-Tup1 complex.

(a) [OCT+] cells express lacZ fused to CYC7 or ANB1 promoters. Patches from triploid yeast obtained by crosses of MATα cells containing either CYC7-lacZ (strain: i182-248) or ANB1-lacZ (strain: MZ12-17) chimeras (kind gifts of R. Zitomer) to MATaa L-2729 derivatives ([oct−], [OCT+] or [oct−] obtained by GuHCl curing of [OCT+]) were tested for β-galactosidase activity at 30 °C by overlaying grown up plates with 5 mg ml−1 melted agarose containing the substrate X-Gal (0.25 mg ml−1), 6% dimethyl formamide, and 0.1% SDS. Positive β-galactosidase activity, as scored by appearance of blue color due to X-gal hydrolysis, indicated de-repression of the corresponding gene promoter. (b) [OCT+] cells show higher mRNA levels of Cyc8-repressed genes. mRNA levels of five Cyc8-repressed genes CYC7, RNR3, FLO1, ANB1, and SUC2 were estimated with real-time PCR using equal amounts of cDNA reverse transcribed from isolated total RNA. Results show data from an [OCT+] L-2729 strain, an [oct−] derivative of this strain obtained by growth of the [OCT+] strain on 4 mM GuHCl (GuHCl cured [oct−]) and a cyc8Δ strain (L3043). The actin gene ACT1, which is not regulated by the Cyc8-Tup1 complex, was used to normalize mRNA levels and the results are expressed as fold change in the mRNA levels compared to the original [oct−] L-2729 control. Note the [oct−] control is the [oct−] strain in which [OCT+] was induced. The error bars indicate standard deviation (n=3).

Our data establishes that the global transcriptional repressor Cyc8 can form and propagate a prion. This together with the recent evidence that another global transcriptional regulator, Swi1 also enters a prion state4, raises the possibility that prionization of these proteins may have a functional role. Interplay of the Cyc8-Tup1 repressor and the Swi-Snf activator-repressor complexes determines the expression fate of many genes by remodeling chromatin in promoter and upstream regions21,22. Thus prionization of Cyc8 and Swi1 may provide an additional level of control over the dynamics of chromatin remodeling. Furthermore, since heterologous prions appear to cross-talk in vivo either facilitating prionization8 or causing prion-loss23, interactions between [OCT+] and [SWI+], could generate a novel regulatory mechanism for repression and de-repression of target genes.

Methods

Yeast culture and Media

Standard yeast media were used24. Yeast cells were grown at 30 °C. YPD is complex glucose rich medium24. Synthetic glucose-Ura, -Leu etc. are synthetic complete glucose medium respectively lacking uracil and leucine etc. Lactate-Ura is synthetic lactate medium9 lacking uracil. Expression of plasmid pGAL-HSP104KT was induced on synthetic complete medium containing 2% galactose and 1% raffinose but lacking glucose and uracil. Since [OCT+] can be lost spontaneously, and under repeated selection homozygous genetic mutations that confer the Lac+ phenotype will appear, we propagated [OCT+] cells on glucose.

Chemicals

5-fluoroorotic acid was from Toronto Research Chemicals, Canada. Galactose, sucrose, raffinose, sorbitol, guanidine hydrochloride (GuHCl), 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TPC) were from Sigma Chemicals, USA. X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-galactopyranoside) was procured from DD Diagnostic Chemicals Limited, Canada.

Strains and plasmids

L-2729, MATa/MATa [PIN+] cyc1::kan/cyc1-363 his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2-3,12/leu2Δ0 LYS2/lys2Δ0 ura3Δ0/ura3-52 TRP1/trp1-289 CAN1/can1-100 CYH2/cyh2 (see Supplementary Information Methods for origin); L-2762, MATα leu2Δ0 ura3Δ0 his3Δ1 cyc1::kan CYC8-GFP; L-3045, URA3 replacement of CYC8 in L-2762; L-899, MATα cyc1Δ trp5 his1 rad52-1; L-2814, [rho−] kar1-Δ15 L-2762; L-3054, cytoductant of L-2814 with an [OCT+]L-2729; L-3055, URA3 replacement of CYC8 L-3054; L-3043, MATa his3Δ0 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cyc8::kan (from Yeast deletion library); SL873-4A, MATa ura3-52 lys2 cyc1-1. The strains MZ12-17, MATα trp1 leu2 ura3::ANB1-lacZ and i182-242, MATα ura3 his3 trp1 cyc1-anb1::CYC7-lacZ were kind gifts of R. Zitomer.

pCYC8PD is a URA3 leu2-d 2μ plasmid encoding aa: 465–966 of Cyc8 (see Supplementary Information methods for construction). pCYC8(1–453) is a URA3 leu2-d 2μ plasmid encoding an N-terminal functional fragment (aa:1–453) of Cyc8 and lacking the QN-rich C-terminus (see Supplementary Information Methods for source). pGAL-HSP104-KT encoding URA3 GAL1p-HSP104K218TK620T25 and pCUP-CYC8YFP encoding CUP1p-CYC8-YFP16 are pRS316 based plasmids. pRT81 is YEP24 based 2μ URA3 CYC811 (a kind gift of R. Trumbly). pRAA9 is YIp5 based URA3 lys2Δ2.6kb26. pES5 is pRS313 based HIS3 GAL1p-HSP104 (a kind gift of S. Lindquist).

Assays for [OCT+]

Lactate assay

~2000 cells in 10 μL H2O were spotted on synthetic lactate and control synthetic glucose plates. Growth on lactate was examined after 7 days at 30 °C.

Flocculation Assay

Flocculation was assayed as described previously27 with minor modifications. Yeast were grown to log phase and washed with 2 mM EDTA in 10 mM TrisHCl pH 8.0 and then re-suspended in the same buffer to an OD600nm of 1. Next, 100 mM CaCl2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM and the cell suspension was agitated to promote cell aggregation and then observed under a light microscope for cell-clumping.

Invertase Assay

Invertase was assayed following glucose repression as described previously28 with minor modifications. Cells grown in YPD were washed twice to remove any traces of glucose and re-suspended in water to normalized cell concentrations. A 10 μL aliquot from each was spotted on Whatman No.3 filter paper that was pre-soaked in 5% sucrose in 10 mM pH 4.6 sodium acetate. The filter paper was allowed to ferment sucrose for 10 min at room temperature. Then, the petri-plate containing the filter was transferred to a 50 °C water bath. 1 ml of 0.1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TPC) dissolved in 0.5 M NaOH, which turns red when it reacts with glucose, was spread evenly on the filter. When the red color appeared in positive controls, the filter was blotted dry to stop the reaction and photographed. Strains being compared were always assayed simultaneously and with controls. The darkness of the red color reflects the level of invertase secreted from the cells assayed.

Cytoduction

L-2729[OCT+] or L-2729[oct-] were donors and L-2814 [oct−] [rho−] which contains the kar1-Δ15 mutation15 was the recipient. After mating, cells were spread on synthetic glucose-His medium to select for single colonies and transferred to glycerol medium to score for non-petites. A non-petite His+ colony could either be a cytoductant or a triploid. These were distinguished by the ability of the MATα cytoductant, but not the triploid, to mate with a MATa tester. Although [OCT+] inhibited the ability of the MATα cytoductants to mate efficiently, they still mated more efficiently than the triploids. Cytoductants scored by this mating method were all verified to be cytoductants by genomic PCR amplification of the KAR1 allele(s) using the primers-FWD: 5′CGGCGAATGTAACTTCTCCAAAAGATGGGAATCAC3′ and REV: 5′CGGCGTGCGGTGGAAATACAAATTGTCCATAAGAAAT3′. A true cytoductant showed a unique PCR product of ~1.02 Kb corresponding to the kar1-Δ15 allele. A triploid showed two products of ~1.27 Kb and ~1.02 Kb corresponding respectively to the wild-type KAR1 and kar1-Δ15 alleles. Cytoductants were then assayed for growth on synthetic lactate and for invertase activity to assess the inheritance of [OCT+].

Transformation with cell lysates

Cells from L-2729 [OCT+] or L-2729 [oct−] were grown in YPD and lysed by agitation with 0.5 mm glass beads at 4 °C in STC buffer (1 M sorbitol, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM TrisHCl pH 7.5) containing a protease inhibitor cock-tail (Sigma Chemicals). Lysates were cleared of debris by centrifugation at 1000 × g and then co-transformed with LEU2 plasmid pRS315 into spheroplasts made from L-2729 [oct−] using PEG3350 buffer18. Leu+ transformants were then examined for the gain of [OCT+] by a spot test on synthetic lactate plates. For control, the inability of the plasmid to transform cell lysates in the absence of recipient cells was confirmed.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from [oct−] L-2729, [OCT+] L-2729, [oct−] obtained by GuHCl treatment of [OCT+] L-2729 and cyc8Δ L3043 yeast cells, pre-grown to log phase under glucose-repressed conditions, using Ribopure™ yeast reagent (Ambion) according to the manufacturers instructions. Quality of RNA was checked by A260/A280 and equal amounts of RNA were reverse-transcribed using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions using Oligo(dT)12–18 primers. Equal amounts of reverse-transcribed RNA (cDNA) were used with the following primers: ACT1: forward-5′TGGCCGGTAGAGATTTGACTGACT3′, reverse-5′TCGAAGTCCAAGGCGACGTAACAT3′; ANB1: forward-5′GTCACGCCAAGGTCCATTTGGTTA3′, reverse-5′AGCTTGCATGCTGTCACCCAATTC3′ ; CYC7: forward-5′AGTACGGGATTCAAACCAGGCTCT3′, reverse 5′TGGGTTCGTCAAGTACTCGGACA3′; FLO1: forward-5′ACTGCTTCACCTGCCATTGTTTCG3′, reverse-5′TGTTGTCTCACCGGTAGCACTGTT3′; RNR3: forward-5′CGCAAAGAGCCCGTTCAATTCGAT3′, reverse -5′ATCAGGGTGCACAGTGGTCATGTA3′; SUC2: forward-5′TGGGCTTCAAACTGGGAGTACAGT3′, reverse-5′AAACGAGACCAGGGACCAGCATTA3′. Real-time PCR was performed on DNA Engine2 (Opticon) qPCR machine and data were analyzed using the provided software. The PCR mixture (50 μl total) contained 25 μl of 2x SyberGreen PCR mastermix (Invitrogen), 5 μl of cDNA, 5 μl of 4 μM forward primer, 5 μl of 4 μM reverse primer and 10 μl DEPC-treated water. The protocol for PCR consisted of one denaturation at 95 °C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 sec, annealing at 62 °C for 30 sec, and extension at 72 °C for 15 sec. The efficiency of PCR was 100% and R2 value was between 0.992 and 0.995. A standard curve was generated using a linear plasmid DNA containing yeast ACT1 allele. For each sample, ACT1 was used as an endogenous control to normalize mRNA levels. Experiments were done in triplicate and data are expressed as fold change in mRNA levels compared to that of an [oct−] yeast.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Sherman and R. Zitomer for yeast strains and R. Trumbly, H. Ronne, Y. Chernoff, S. Lindquist, M. Duennwald, M.D. Rose, S. Ruby, H. van Vuuren, I. Derkatch and M. Carlson for plasmids and S.Y.R. Dent for anti-cyc8 and anti-Tup1 antibodies. We also thank K. Kirkland, V. Mathur, J. Hong and O. Appelebe for help with experiments and A. O’Dell for helpful suggestions and S-K. Park, A. Manogaran, and N. Vishveshwara for commenting on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant (GM-56350) to SWL. The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH.

References

- 1.Stefani M, Dobson CM. Protein aggregation and aggregate toxicity: new insights into protein folding, misfolding diseases and biological evolution. J Mol Med. 2003;81:678–99. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wickner RB. [URE3] as an altered URE2 protein: evidence for a prion analog in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Science. 1994;264:566–9. doi: 10.1126/science.7909170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wickner RB, Liebman SW, Saupe SJ. Prions of yeast and filamentous fungi: [URE3], [PSI+], [PIN+], and [Het-s] In: Prusiner SB, editor. Prion Biology and Diseases. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du Z, Park KW, Yu H, Fan Q, Li L. Newly identified prion linked to the chromatin-remodeling factor Swi1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Genet. 2008;40:460–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–44. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith RL, Johnson AD. Turning genes off by Ssn6-Tup1: a conserved system of transcriptional repression in eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:325–30. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01592-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green SR, Johnson AD. Promoter-dependent roles for the Srb10 cyclin-dependent kinase and the Hda1 deacetylase in Tup1-mediated repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4191–202. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Derkatch IL, Bradley ME, Hong JY, Liebman SW. Prions affect the appearance of other prions: the story of [PIN+] Cell. 2001;106:171–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rothstein RJ, Sherman F. Genes affecting the expression of cytochrome c in yeast: genetic mapping and genetic interactions. Genetics. 1980;94:871–89. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.4.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson M, Osmond BC, Neigeborn L, Botstein D. A suppressor of SNF1 mutations causes constitutive high-level invertase synthesis in yeast. Genetics. 1984;107:19–32. doi: 10.1093/genetics/107.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trumbly RJ. Cloning and characterization of the CYC8 gene mediating glucose repression in yeast. Gene. 1988;73:97–111. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schultz J, Marshall-Carlson L, Carlson M. The N-terminal TPR region is the functional domain of SSN6, a nuclear phosphoprotein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4744–56. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.9.4744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [PSI+] Science. 1995;268:880–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuite MF, Mundy CR, Cox BS. Agents that cause a high frequency of genetic change from [PSI+] to [psi−] in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1981;98:691–711. doi: 10.1093/genetics/98.4.691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conde J, Fink GR. A mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae defective for nuclear fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:3651–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duennwald ML, Jagadish S, Giorgini F, Muchowski PJ, Lindquist S. A network of protein interactions determines polyglutamine toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11051–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604548103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patino MM, Liu JJ, Glover JR, Lindquist S. Support for the prion hypothesis for inheritance of a phenotypic trait in yeast. Science. 1996;273:622–6. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5275.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel BK, Liebman SW. Prion-proof” for [PIN+]: Infection with in vitro-made amyloid aggregates of Rnq1p-(132–405) induces [PIN+] J Mol Biol. 2007;365:773–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King CY, Diaz-Avalos R. Protein-only transmission of three yeast prion strains. Nature. 2004;428:319–23. doi: 10.1038/nature02391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka M, Chien P, Naber N, Cooke R, Weissman JS. Conformational variations in an infectious protein determine prion strain differences. Nature. 2004;428:323–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavin IM, Simpson RT. Interplay of yeast global transcriptional regulators Ssn6p-Tup1p and Swi-Snf and their effect on chromatin structure. EMBO J. 1997;16:6263–71. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming AB, Pennings S. Antagonistic remodelling by Swi-Snf and Tup1-Ssn6 of an extensive chromatin region forms the background for FLO1 gene regulation. EMBO J. 2001;20:5219–31. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley ME, Liebman SW. Destabilizing interactions among [PSI+] and [PIN+] yeast prion variants. Genetics. 2003;165:1675–85. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.4.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherman F, Fink GR, Hicks JB. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York, USA: 1986. Methods in Yeast Genetics. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wegrzyn RD, Bapat K, Newnam GP, Zink AD, Chernoff YO. Mechanism of prion loss after Hsp104 inactivation in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:4656–69. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4656-4669.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alksne LE, Anthony RA, Liebman SW, Warner JR. An accuracy center in the ribosome conserved over 2 billion years. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9538–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miki BL, Poon NH, James AP, Seligy VL. Possible mechanism for flocculation interactions governed by gene FLO1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1982;150:878–89. doi: 10.1128/jb.150.2.878-889.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trumbly RJ. Isolation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants constitutive for invertase synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1986;166:1123–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.166.3.1123-1127.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erhart E, Hollenberg CP. The presence of a defective LEU2 gene on 2μ DNA recombinant plasmids of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is responsible for curing and high copy number. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:625–35. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.625-635.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boeke JD, Trueheart J, Natsoulis G, Fink GR. 5-Fluoroorotic acid as a selective agent in yeast molecular genetics. Methods Enzymol. 1987;154:164–75. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)54076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.