Abstract

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) and juvenile retinitis pigmentosa (RP) are the most common hereditary causes of visual impairment in infants and children. Using homozygosity mapping, we narrowed down the critical region of the LCA3 locus to 3.8 Mb between markers D14S1022 and D14S1005. By direct Sanger sequencing of all genes within this region, we found a homozygous nonsense mutation in the SPATA7 gene in Saudi Arabian family KKESH-060. Three other loss-of-function mutations were subsequently discovered in patients with LCA or juvenile RP from distinct populations. Furthermore, we determined that Spata7 is expressed in the mature mouse retina. Our findings reveal another human visual-disease gene that causes LCA and juvenile RP.

Introduction

Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA [MIM 204000]) is a set of inherited, early-onset retinal dystrophies that affect approximately 1:50,000 people in the general U.S. population and account for more than 5% of all retinal dystrophies.1,2 The clinical phenotypes of LCA are characterized by severe visual loss at birth, nystagmus, a variety of fundus changes, and minimal or absent recordable responses on the electroretinogram (ERG), usually with an autosomal-recessive pattern of inheritance.3 Consistent with this clinical variability, the molecular basis for LCA is also heterogeneous, with mutations described in fourteen genes. Functional studies of previously identified genes indicate that they act in strikingly diverse functional pathways underlying the disease, including retina development (CRB1 [MIM 604210],4 CRX [MIM 602225]5–7), phototransduction (GUCY2D [MIM 600179],8 AIPL1 [MIM 604392]9), vitamin A metabolism (RPE65 [MIM 180069],10,11 LRAT [MIM 604863],12 RDH12 [MIM 608830]13), and cilium formation and function (CEP290 [MIM 610142],14 TULP1 [MIM 602280],15 RPGRIP1 [MIM 605446],16,17 LCA5 [MIM 611408]18). In addition, the function of RD3 remains unclear.19 Because of these profound differences in the underlying mechanisms of LCA, accurate molecular diagnosis of the disease is essential for the proper management of LCA patients. Therefore, identifying new genes and pathways and ascertaining the full complement of genes responsible for LCA are fundamental steps toward developing appropriate treatments for this devastating disease.

Knowledge obtained from LCA studies also offers insights into the pathogenesis and the molecular mechanisms underlying other retinal dystrophies, which are often shared.20 LCA shares several important clinical features with other retinal dystrophies, such as retinitis pigmentosa (RP [MIM 500004]). In fact, LCA was first described as an “intrauterine” form of RP.1 Juvenile RP, unlike LCA, initially has a milder phenotype. It is often characterized by the onset of nyctalopia (night blindness), visual-field narrowing, and eventual visual-acuity loss, with or without nystagmus. Given the substantial clinical overlap with juvenile RP, it is expected that these two diseases might be caused by mutations in the same gene.21 Indeed, at least seven of the known LCA disease genes, including CRX, CRB1, RPE65, RDH12, LRAT, MERTK, and TULP1, have also been linked to the clinical appearance of juvenile RP in other families.22 Similarly, mutations in LCA genes may also be associated with other retinal diseases, such as cone-rod dystrophy (CRX,5 AIPL1,23 and GUCY2D8,9), and even systemic diseases, such as Joubert syndrome, Meckel syndrome, and Bardet-Biedl syndrome (CEP29024–26).

In addition to these 14 LCA genes, two genetic loci (LCA3 at 14q24 and LCA9 at 1p36) have been identified, but the underlying genes remain unknown.27,28 The exclusion of RDH12 as an LCA3 disease gene suggests that another retinal dystrophy disease gene is responsible for the LCA3 phenotype.29 In this report, we identified five new families that we mapped to the LCA3 locus, utilizing fine mapping of the critical region through homozygosity mapping and single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray technology.21 We identified homozygous nonsense and frameshift mutations in a positional candidate gene, SPATA7 (spermatogenesis associated protein 7 [MIM 609868]) by direct Sanger sequencing. SPATA7 encodes a highly conserved protein containing a single transmembrane domain. To better understand its normal function in the retina, we examined the expression pattern of Spata7 in the developing and mature mouse retina, and we found that it is expressed in multiple retinal layers in the adult mouse retina.

Subjects and Methods

Study Subjects

We obtained blood samples and pedigrees after receiving informed consent from all individuals. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the participating centers. LCA families KKESH-019 and KKESH-060 were obtained by R.A.L. through the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital (KKESH) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Blood samples were collected from all available family members, and DNA was extracted with the QIAGEN blood genomic DNA extraction kit, in accordance with the protocol provided by the manufacturer. Other LCA and juvenile RP samples were collected at the McGill University Health Center in Montreal or at the Department of Ophthalmology at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre in Nijmegen.

STR and SNP Genotyping and Sequencing

A list of microsatellite markers between D14S61 and D14S1015 were selected from the UCSC Human Genome Browser. For genotyping, primers specific for each marker were obtained from the human genome, and a universal tail was added to the 5′ primer (5′-CTCGGTGCAGAGCATCATGC). PCR reactions were performed according to a standard protocol,30 and products were size fractionated on an ABI 3700 capillary electrophoresis system and analyzed with the ABI GeneMapping software. A genome-wide scan of >318,000 tag SNPs was conducted on one affected member from the KKESH-060 and KKESH-019 families with the Illumina Hap300-Duo Bead Arrays, in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. Homozygous regions were visualized and identified with the Bead Studio software package.

For identification of mutations in candidate genes, a direct PCR-sequencing approach was used. All exons and their splice junctions for each candidate gene (total of 9) in the critical LCA3 region were amplified by PCR. The completeness and quality of the sequence was ensured by the design of primers from intron sequences so that the entire exon and at least 50 bp of intron DNA on each side of each exon were amplified for detection of potential mutations. For large exons, more than one pair of primers amplified overlapping regions spanning both the exon and its splice sites. Sequences for the primers of the 12 exons and splice junctions of SPATA7 are included in Table S1 (available online).

Homozygosity Mapping with SNP Arrays for Identification of LCA and Juvenile RP Patients Whose Disease Region Overlaps with LCA3

We previously performed homozygosity mapping in 33 consanguineous and 60 nonconsanguineous individuals with LCA or juvenile RP from various ethnic origins with 10K, 100K, or 250K Affymetrix SNP microarrays,21 and we recently added 50 patients to this analysis (A.I.d.H., unpublished data). Five patients were found to be homozygous at the LCA3 locus, with homozygous regions ranging in size from 1.6 to 29 Mb.

RNA In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry

An RNA in situ probe specific to Spata7 (exons 8–12) was prepared according to a previously published protocol31 (probe 5′-primer: 5′-CTAATTACACGAGAAATGGTGCTG; probe 3′-primer: 5′-AGTGATGTGCTCAGACAACAGAGT). Total RNA was extracted from freshly isolated C57 wild-type (WT) eyes homogenized in Trizol (Invitrogen) and purified according to the manufacturer's instructions. A Spata7 cDNA fragment was cloned into the EcoRI site of the TOPO cloning vector (Invitrogen). Antisense riboprobe constructs were linearized with XhoI and transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase (DIG RNA Labeling Kit, Roche).

RNA in situ hybridization (ISH) and antibody staining was conducted on WT E16.5, P4, and P21 and C57Bl/6 129SvEv F1 hybrid eye sections. WT eyes were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, dehydrated in ethanol, and paraffin embedded. For ISH, 5 μm eye sections were cut, dewaxed in xylene, then rehydrated and treated with proteinase K. Hybridization incubations were carried out in hybridization buffer (50% formamide, 5XSSC [pH 4.5–5.0], 1% SDS, 50 mg/ml yeast tRNA, 50 mg/ml heparin) at 65°C overnight, followed by three 30-min washes with prewarmed washing buffer (50% formamide, 1XSSC [pH 4.5–5.0], 1% SDS) at 65°C. The slides were then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-DIG (Roche) in 1× MABT (100 mM maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.5), 2% BRB (Roche) and 10% goat serum overnight at room temperature. After five washes (30 min each) with MABT buffer and one wash with NTMT (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.5], 100 mM NaCl, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20, and 0.048% levamisole), hybridization signals were visualized by incubation with BM Purple (Roche) at room temperature for the desired time.

For immunohistochemistry (IHC), antigen retrieval was performed by boiling of 10 μm sections in 0.01 M citrate buffer twice for 2 min, followed by cooling for 40 min at room temperature. Slides were washed in PBS, incubated for 1 hr at room temperature in hybridization buffer (10% normal goat serum, 0.1% Triton X-100, PBS), then incubated overnight in primary antibody diluted in hybridization buffer. Slides were then washed in PBS, incubated with secondary antibody diluted in hybridization buffer at room temperature for 2 hr, washed in PBS, and coverslipped. For testing the specificity of the Spata7 antibody, a blocking experiment was performed. A GST-Spata7 fusion protein was constructed by insertion of a mouse Spata7 open reading frame into the multiple cloning site of the pGEX-4T-1 vector. The fusion protein was induced in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG at 26°C for 8 hr and purified with the use of Glutathione Sepharose 4B as described in manufacturers' instructions (Amersham Bioscience). The in vitro antibody-depletion experiments were performed with purified GST or GST-Spata7 fusion proteins bound to Glutathione Sepharose 4B. Spata7 antibody was incubated with 50 μl of GST beads, containing either GST-Spata7 or GST, at 4°C overnight, then the depleted antibody was used for IHC as described above.

Dilutions and sources of antibodies were: mouse anti-rhodopsin (B6-30N) (1:100, a generous gift from W. Clay Smith), rabbit anti-Spata7 (1:7.5, Proteintech Group), Alexa anti-mouse (1:400, Molecular Probes), Cy5 anti-rabbit (1:400, Jackson Immunochemicals). Fluorescent images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope and processed with Image J and Adobe Photoshop software.

Results

Fine Mapping of the LCA3 Locus

Previously, the LCA3 locus was mapped to chromosome 14q24 in a large, consanguineous LCA family (KKESH-019) from Saudi Arabia with 15 affected and 42 unaffected members.27 The critical region was initially identified by homozygosity mapping with STR markers. However, the distal boundary of the critical region was not well mapped, because there was no genotyping within a 10 Mb segment between D14S74 and D14S68. More importantly, at least four recombinants have been reported for marker D14S68, indicating that the critical region could be greatly reduced by genotyping of additional markers within the distal region.

We therefore conducted fine mapping of the distal boundary of the critical region with additional STR markers between D14S74 and D14S68 (Table S1). On the basis of these genotyping results, all affected members of KKESH-019 were found to be homozygous between markers D14S1022 and D14S1005 (Figure S1). We then used these STR markers to scan additional LCA patient cohorts for new LCA families that may map to the LCA3 region. In this manner, the KKESH-060 family from Saudi Arabia was also identified as an LCA3 family29 (Figure S2). All three affected members from the KKESH-060 family are homozygous from markers D14S61 to D14S1066. To further confirm the homozygous region, DNA from one affected subject from each of these two families was genotyped by whole-genome SNP analysis with the Illumina SNP array. The new SNP genotyping results are consistent with the previous STR genotyping data, and affected subjects from these two families are homozygous for the LCA3 locus at Chromosome 14q24 (Figure S3). Intersection of the homozygous region from these two LCA families defines a critical region of 3.8 Mb between markers D14S1022 and D14S1005.

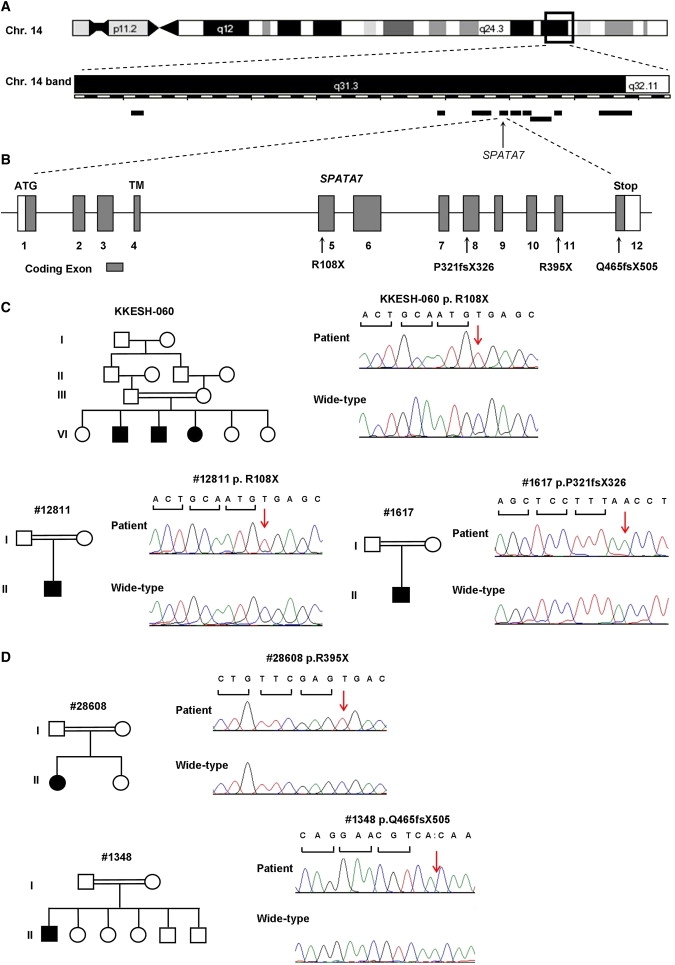

SPATA7 Is Another LCA and Juvenile RP Gene

A total of nine annotated genes are included within the newly defined LCA3 critical region based on NCBI Build 36.1 (Figure 1A). Direct Sanger sequencing of all exons of all nine candidate genes from both LCA3 families identified a nonsense mutation in SPATA7, a conserved gene containing 12 exons, in the KKESH-060 family (Figure 1C). All three affected members of KKESH-060 are homozygous for a nonsense mutation in the fifth exon (c.322C→T; p.R108X). The mutation segregates with the disease in this family, given that the three affected individuals are homozygous for the same mutation whereas the unaffected members are either heterozygous or do not carry the mutation (Figure 1C and Figure S2). Furthermore, the nonsense mutation is not a common SNP, because it is not recorded in the dbSNP database. Consistent with the above information, the mutation was not detected in 150 normal control samples, including 50 Saudi Arabian and 100 European samples, through direct sequencing of all exons of SPATA7 (data not shown). No exonic mutation was found in KKESH-019 (see Discussion for details). To further confirm that SPATA7 is an LCA disease gene, we sought to identify additional LCA patients with SPATA7 mutations. By homozygosity mapping with genome-wide SNP microarrays, five additional patients with LCA or juvenile RP were recently found to be homozygous at the LCA3 locus (21 and unpublished data). Mutation analysis of SPATA7 revealed the same R108X nonsense mutation (found in the KKESH-060 family) in a Dutch LCA patient (no. 12811) (Figure 1C). On the basis of the STR genotyping result, the mutation analysis suggests that patient no. 12811 does not share the same haplotype with the patients from KKESH-060 (data not shown). This may be caused by a rapid decay of CpG sites, given that the 5-methylcytosine at CpG sites mutates unidirectionally to thymine by spontaneous deamination at a much higher transition rate compared to non-CpG dinucleotides.32 Finally, a homozygous frameshift mutation (c.961dupA; p.P321TfsX326) in exon 8 of SPATA7 was found in an LCA patient (no. 1617) of Middle Eastern origin (Figure 1C). In addition, a Portuguese patient (no. 28608) with juvenile RP was found to be homozygous for a nonsense mutation (c.1183C→T; p.R395X) in exon 11 of SPATA7 (Figure 1D). Finally, a homozygous frameshift mutation in exon 12 (c.1546delA; p.Q465fsX505) was identified in a French Canadian patient (no. 1348) with juvenile RP (Figure 1D). All mutations segregated with the disease in the affected families were not found in the 150 normal controls or in the SNP databases. In contrast to the two SPATA7 mutations identified in LCA patients (p.R108X and p.P321TfsX326), the two juvenile RP mutations are close to the C-terminal part of the SPATA7 protein.

Figure 1.

Mutations in SPATA7 Cause LCA

(A) The LCA3 critical interval at 14q31. Nine candidate genes within the region are indicated as black bars. SPATA7 is indicated by a black arrow. The chromosome band is modified on the basis of the Ensemble ContigView.

(B) Exon-intron structure of the SPATA7 gene is shown. Open boxes represent 5′ and 3′ UTRs, and solid boxes represent coding exons. A transmembrane domain (TM) is predicted to be encoded in exon 4. Mutations are indicated with arrows.

(C) Pedigrees and sequences of mutations of LCA families. Two different mutations were identified in these three families: all three patients from the KKESH-060 family, c.322C→T (p.R108X); patient no. 12811 from the Dutch family, c.322C→T (p.R108X); patient no. 1617 from the family with mid Eastern origin, c.961dupA (p.P321TfsX326).

(D) Pedigrees and sequences of mutations of juvenile RP families. Two different mutations were identified: patient no. 28608, c.1183C→T (p.R395X); patient no. 1348, c.1546delA (p.Q465fsX505).

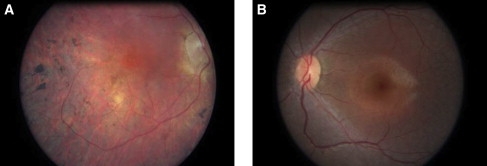

Although carrying mutations in the same gene, the two juvenile RP patients present a clinical phenotype that is less severe than that of LCA patients. All three LCA patients from the KKESH-060 family showed poor visual fixation and function from birth and subsequently developed nystagmus, hyperopic astigmatism, and a nondetectable electroretinogram. A Dutch patient (no. 12811) was first seen in our clinic at age 6. She has had visual problems since birth, showing rotating nystagmus, peripheral chorio-retinal atrophy, and bone spicules pigmentation. In contrast, a 7-year-old Portuguese girl (no. 28608, diagnosed with juvenile RP) has excellent visual acuity (20/20), and nystagmus is absent. She developed early-onset nyctalopia before age 2 and has 5° visual fields (Goldmann) and nondetectable ERGs (Figure 2A). Similarly, a juvenile RP patient (no. 1348) from a French Canadian family was found to have hand-motion vision at age 55. He reported seeing normally as a child and then declining, developing night blindness and nystagmus. This patient was found to have advanced retinal pigmentary degeneration, with narrow arterioles, optic disc pallor, and a small maculopathy on exam at age 55 years (Figure 2B). The ERG was nondetectable, and the visual fields were reduced to 5° with the V4e target.

Figure 2.

Color Photographs of the Retinas of Two RP Patients with SPATA7 Mutations

(A) Retinal image of the right eye of a 55-year-old male with juvenile RP and a homozygous c.1546delA p.Q465fsX505 frameshift mutation in SPATA7.

(B) Retinal photograph of the left eye of a 9-year-old female with 20/20 acuities, 5° visual fields, and a homozygous p.R395X nonsense mutation in SPATA7. The retinal appearance shows narrow arterioles but normal-caliber veins, normal color of the optic disc, a subtle grayish discoloration of the retina, and a faint hypopigmented diffuse perifoveal annulus. There were no pigmentary changes.

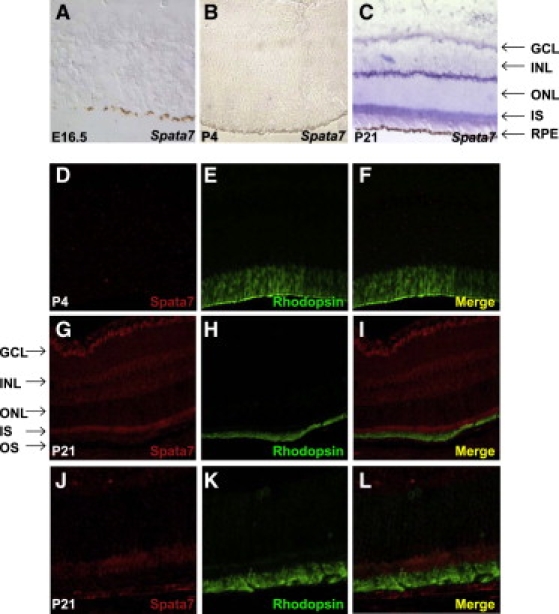

Spata7 Is a Highly Conserved, Vertebrate-Specific Protein Expressed in the Mature Retina

Human SPATA7 comprises 12 exons (Figure 1B) that encode a protein of 599 amino acids. SPATA7 is conserved from sea urchin to human but is absent in lower eukaryotes, such as insects and fungi (Figure S4). A single-pass transmembrane domain is predicted by the PSIPred program (Figure 1B). However, no previously known functional domains have been identified.

Studies of gene-expression profiles, including the use of microarrays and databases of expressed sequence tags, indicate that SPATA7 is expressed in the human retina. We examined the expression pattern of Spata7 in the mouse retina at several developmental stages, using both mRNA ISH and IHC. Mouse retinas were stained at three developmental time points, E16.5, P4, and P21, corresponding to early, middle, and fully developed retinas. On the basis of the ISH results, Spata7 is not detectable in the E16.5 or P4 mouse retina (Figures 3A and 3B), suggesting that Spata7 is not required for early retinal development. In contrast, expression is observed in the P21 mature mouse retina, suggesting that Spata7 may be involved in normal retinal function rather than development (Figure 3C). Consistent with ISH results, little Spata7 protein is detected in the P4 mouse retina by IHC (Figures 3D–3F). In contrast, expression of Spata7 protein is observed in multiple layers of the P21 retina, including the ganglion cell and inner nuclear layers, and inner segments of photoreceptors (Figures 3G–3L).

Figure 3.

Spata7 Is Expressed in the Adult Mouse Retina

(A–C) Section ISH with Spata7 riboprobes. (A) Spata7 is absent in all layers of the E16.5 mouse eye. (B) Spata7 is absent in all layers of the P4 mouse eye. (C) At P21, Spata7 is present in the ganglion cell layer, the inner nuclear layer, and the inner segment of the photoreceptors.

(D–F) Double immunostaining of Spata7 (red) and Rhodopsin (green) shows that Spata7 is not expressed in the P4 mouse retina.

(G–I) Double immunostaining of Spata7 (red) and Rhodopsin (green) in the P21 mouse retina demonstrates that Spata7 protein is expressed in multiple cell layers of the retina.

(J–L) High-magnification images of photoreceptors reveals that Spata7 expression is prominent in the inner segment and sparse in the Rhodopsin-labeled outer segment. Abbreviations are as follows: ONL, outer nuclear layer; IS, inner segment; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; OS, outer segment.

Discussion

It is interesting to note that mutations in SPATA7 cause LCA and RP, two overlapping but distinct human retinal diseases. A fascinating aspect of human retinal diseases is the enormous heterogeneity in terms of both clinical phenotypes and their underlying molecular mechanisms. Undoubtedly complex genetic inheritance contributes to this heterogeneity. For example, digenic triallelic inheritance has been observed in some families segregating the Bardet-Biedl phenotype, in which inheritance of a mutation in a second gene is required for an individual who has two mutations in the first gene to exhibit a clinical phenotype or to modify the severity of the primary phenotype.33 Another major cause for heterogeneity is differential severity of mutant alleles at a single locus, as is likely in our study. We have isolated multiple loss-of-function mutations in SPATA7 that cause either LCA or juvenile RP. Consistent with the observation that LCA has a more severe clinical phenotype than juvenile RP, the mutant alleles associated with LCA are likely to be more severe loss-of-function alleles than those associated with juvenile RP. The two alleles found in our LCA patients are nonsense mutations located in the middle of the SPATA7 coding region (exons 5 and 8; Figure 1B). These two mutations will probably cause relatively early protein truncations and therefore are likely to be severe loss-of-function alleles because of nonsense-mediated decay and destruction of message.34,35 In contrast, the two mutations that we identified in the juvenile RP patients are located in the last two exons of SPATA7. Because these two mutations are very close to the C terminus of the protein, they will probably cause only truncation of a small portion of the protein product, although it is possible that the mutation in the second-to-last exon could cause a reduction of SPATA7 mRNA levels as a result of nonsense-mediated decay.34,35 Therefore, our findings provide suggestive evidence of a correlation between the severity of mutant alleles in SPATA7 and the resulting clinical phenotype.

It is conceivable that many human diseases are caused not only by coding mutations but by noncoding-region mutations that may affect gene expression. For example, the most prominent mutation in the LCA gene CEP290 is an intron mutation that causes aberrant splicing of the transcript.14 Our data suggest that the initial LCA3 family, KKESH-019, probably carries a mutation outside of the coding region of the SPATA7 gene rather than in other genes in this locus. All genes within the critical region defined by the KKESH-019 family alone have been sequenced, and no mutations were identified within exonic sequences in the KKESH-019 family. To identify a disease-causing mutation in the KKESH-019 family, we first sequenced the 5′ and 3′ UTR regions of SPATA7, but we found no change. Furthermore, to test for possible chromosome rearrangements at the SPATA7 locus in this family, we used tiling of 3 kb PCR amplicons to analyze the entire SPATA7 locus, including about 50 kb beyond the transcription unit, from an affected KKESH-019 patient, but we found no obvious changes compared to WT. This result suggests that no major chromosomal rearrangements, insertions, or deletions are present at the SPATA7 locus in the KKESH-019 family. However, sequencing of these PCR products did identify several changes, including single-nucleotide substitutions and small insertions and deletions in the promoter region and introns of SPATA7. Because RNA samples from the KKESH-019 family are not available, we are not able to test whether these changes can indeed affect SPATA7 expression in the patients. Additional experiments will need to be carried to determine whether any of these noncoding changes cause defects in normal SPATA7 expression.

SPATA7 is a gene that was first identified in human spermatocytes. On the basis of its expression pattern, SPATA7 may be involved in preparing chromatin in early meiotic prophase nuclei for the initiation of meiotic recombination.36 We found that in addition to its expression in testis, Spata7 is expressed in multiple layers of the mature mouse retina. On the basis of its expression pattern in the retina, it would seem that SPATA7 is not a typical cilium protein, despite its potential function in both sperm and retina. Close examination of SPATA7 expression in the retina indicates that the protein is not enriched at the junction between the inner and outer segments of photoreceptor cells, where the cilium is located. Rather, the protein shows a uniform distribution in the cytoplasm of the inner segment. Given this information, together with the relatively late onset of SPATA7 expression in the retina, we speculate that SPATA7 may be involved a novel pathway. Additional studies need to be carried out to reveal the function of SPATA7.

In summary, we report the cloning of another LCA disease gene, SPATA7. The LCA3 locus was first mapped to chromosome 14 more than 10 years ago, but the causal gene had not been identified. Through the combination of homozygosity mapping by SNP arrays and direct Sanger sequencing of all positional candidate genes within the LCA3 critical region, we identified SPATA7 as the disease-causing gene. Given that we identified multiple mutations in distinct ethnic groups, this gene appears to be an important player in LCA and in other retinal diseases, such as juvenile RP. As a gene that is linked to multiple human diseases, SPATA7 offers opportunities for uncovering novel insights into human pathogenesis.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Data include four figures and two tables and can be found with this article online at http://www.ajhg.org/.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/

PSIPred program, http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/

Retinal Information Network, http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet/

UCSC Human Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/index.html?org=Human&db=hg18&hgsid=120774634

Acknowledgments

We thank Huawei Xin for his help throughout this project and for his useful comments during the preparation of the manuscript. We are indebted to John Cavender, the Research Director of King Khalid Eye Specialist Hospital at the time of these studies, to the Research Council of KKESH for its financial support, and to the staff of its Research Department for their diligent commitment to this program. In addition, we thank the families reported here for their willing cooperation with these studies. R.A.L. is a Senior Scientific Investigator of Research to Prevent Blindness, New York. We also thank Frans Cremers for his valuable discussions and Lara Bou-Khzam for her technical assistance. This work is supported by grants from the Retinal Research Foundation and the National Eye Institute (R01EY018571) to R.C. R.K.K. is supported by the Foundation Fighting Blindness Canada and the Fonds de la Recherche en Santee du Quebec (FRSQ). A.I.d.H. is supported by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (916.56.160) and the Foundation Fighting Blindness USA (BR-GE-0606-0349-RAD).

References

- 1.Leber T. Uber retinitis pigmentosa und angeborene amaurose. Albrecht Von Graefes Arch. Ophthalmol. 1869;15:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dharmaraj S.R., Silva E.R., Pina A.L., Li Y.Y., Yang J.M., Carter C.R., Loyer M.K., El-Hilali H.K., Traboulsi E.K., Sundin O.K. Mutational analysis and clinical correlation in Leber congenital amaurosis. Ophthalmic Genet. 2000;21:135–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis R.A. Retinal Dystrophies and Degenerations. Raven Press; New York: 1988. Juvenile Hereditary Macular Dystrophies. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- 4.den Hollander A.I., Heckenlively J.R., van den Born L.I., de Kok Y.J., van der Velde-Visser S.D., Kellner U., Jurklies B., van Schooneveld M.J., Blankenagel A., Rohrschneider K. Leber congenital amaurosis and retinitis pigmentosa with Coats-like exudative vasculopathy are associated with mutations in the crumbs homologue 1 (CRB1) gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:198–203. doi: 10.1086/321263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freund C.L., Wang Q.L., Chen S., Muskat B.L., Wiles C.D., Sheffield V.C., Jacobson S.G., McInnes R.R., Zack D.J., Stone E.M. De novo mutations in the CRX homeobox gene associated with Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:311–312. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swaroop A., Wang Q.L., Wu W., Cook J., Coats C., Xu S., Chen S., Zack D.J., Sieving P.A. Leber congenital amaurosis caused by a homozygous mutation (R90W) in the homeodomain of the retinal transcription factor CRX: direct evidence for the involvement of CRX in the development of photoreceptor function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:299–305. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobson S.G., Cideciyan A.V., Huang Y., Hanna D.B., Freund C.L., Affatigato L.M., Carr R.E., Zack D.J., Stone E.M., McInnes R.R. Retinal degenerations with truncation mutations in the cone-rod homeobox (CRX) gene. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:2417–2426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perrault I., Rozet J.M., Calvas P., Gerber S., Camuzat A., Dollfus H., Chatelin S., Souied E., Ghazi I., Leowski C. Retinal-specific guanylate cyclase gene mutations in Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:461–464. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohocki M.M., Bowne S.J., Sullivan L.S., Blackshaw S., Cepko C.L., Payne A.M., Bhattacharya S.S., Khaliq S., Qasim Mehdi S., Birch D.G. Mutations in a new photoreceptor-pineal gene on 17p cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 2000;24:79–83. doi: 10.1038/71732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marlhens F., Bareil C., Griffoin J.M., Zrenner E., Amalric P., Eliaou C., Liu S.Y., Harris E., Redmond T.M., Arnaud B. Mutations in RPE65 cause Leber's congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 1997;17:139–141. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perrault I., Rozet J.M., Ghazi I., Leowski C., Bonnemaison M., Gerber S., Ducroq D., Cabot A., Souied E., Dufier J.L. Different functional outcome of RetGC1 and RPE65 gene mutations in Leber congenital amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:1225–1228. doi: 10.1086/302335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson D.A., Li Y., McHenry C.L., Carlson T.J., Ding X., Sieving P.A., Apfelstedt-Sylla E., Gal A. Mutations in the gene encoding lecithin retinol acyltransferase are associated with early-onset severe retinal dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2001;28:123–124. doi: 10.1038/88828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janecke A.R., Thompson D.A., Utermann G., Becker C., Hubner C.A., Schmid E., McHenry C.L., Nair A.R., Ruschendorf F., Heckenlively J. Mutations in RDH12 encoding a photoreceptor cell retinol dehydrogenase cause childhood-onset severe retinal dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:850–854. doi: 10.1038/ng1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Hollander A.I., Koenekoop R.K., Yzer S., Lopez I., Arends M.L., Voesenek K.E., Zonneveld M.N., Strom T.M., Meitinger T., Brunner H.G. Mutations in the CEP290 (NPHP6) gene are a frequent cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:556–561. doi: 10.1086/507318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagstrom S.A., North M.A., Nishina P.L., Berson E.L., Dryja T.P. Recessive mutations in the gene encoding the tubby-like protein TULP1 in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:174–176. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerber S., Perrault I., Hanein S., Barbet F., Ducroq D., Ghazi I., Martin-Coignard D., Leowski C., Homfray T., Dufier J.L. Complete exon-intron structure of the RPGR-interacting protein (RPGRIP1) gene allows the identification of mutations underlying Leber congenital amaurosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;9:561–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dryja T.P., Adams S.M., Grimsby J.L., McGee T.L., Hong D.H., Li T., Andreasson S., Berson E.L. Null RPGRIP1 alleles in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;68:1295–1298. doi: 10.1086/320113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.den Hollander A.I., Koenekoop R.K., Mohamed M.D., Arts H.H., Boldt K., Towns K.V., Sedmak T., Beer M., Nagel-Wolfrum K., McKibbin M. Mutations in LCA5, encoding the ciliary protein lebercilin, cause Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:889–895. doi: 10.1038/ng2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Friedman J.S., Chang B., Kannabiran C., Chakarova C., Singh H.P., Jalali S., Hawes N.L., Branham K., Othman M., Filippova E. Premature truncation of a novel protein, RD3, exhibiting subnuclear localization is associated with retinal degeneration. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:1059–1070. doi: 10.1086/510021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis R.A., Allikmets R., Lupski J.R. Inherited macular dystrophies and susceptibility to degeneration. In: Scriver C.R., Beaudet A.L., Sly W.S., Valle D., Childs B., Vogelstein B., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. Eighth Edition. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 6077–6096. [Google Scholar]

- 21.den Hollander A.I., Lopez I., Yzer S., Zonneveld M.N., Janssen I.M., Strom T.M., Hehir-Kwa J.Y., Veltman J.A., Arends M.L., Meitinger T. Identification of novel mutations in patients with Leber congenital amaurosis and juvenile RP by genome-wide homozygosity mapping with SNP microarrays. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2007;48:5690–5698. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.den Hollander A.I., Roepman R., Koenekoop R.K., Cremers F.P. Leber congenital amaurosis: genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2008;27:391–419. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohocki M.M., Perrault I., Leroy B.P., Payne A.M., Dharmaraj S., Bhattacharya S.S., Kaplan J., Maumenee I.H., Koenekoop R., Meire F.M. Prevalence of AIPL1 mutations in inherited retinal degenerative disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2000;70:142–150. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valente E.M., Silhavy J.L., Brancati F., Barrano G., Krishnaswami S.R., Castori M., Lancaster M.A., Boltshauser E., Boccone L., Al-Gazali L. Mutations in CEP290, which encodes a centrosomal protein, cause pleiotropic forms of Joubert syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:623–625. doi: 10.1038/ng1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baala L., Audollent S., Martinovic J., Ozilou C., Babron M.C., Sivanandamoorthy S., Saunier S., Salomon R., Gonzales M., Rattenberry E. Pleiotropic effects of CEP290 (NPHP6) mutations extend to Meckel syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:170–179. doi: 10.1086/519494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leitch C.C., Zaghloul N.A., Davis E.E., Stoetzel C., Diaz-Font A., Rix S., Alfadhel M., Lewis R.A., Eyaid W., Banin E. Hypomorphic mutations in syndromic encephalocele genes are associated with Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:443–448. doi: 10.1038/ng.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stockton D.W., Lewis R.A., Abboud E.B., Al-Rajhi A., Jabak M., Anderson K.L., Lupski J.R. A novel locus for Leber congenital amaurosis on chromosome 14q24. Hum. Genet. 1998;103:328–333. doi: 10.1007/s004390050825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keen T.J., Mohamed M.D., McKibbin M., Rashid Y., Jafri H., Maumenee I.H., Inglehearn C.F. Identification of a locus (LCA9) for Leber's congenital amaurosis on chromosome 1p36. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;11:420–423. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y., Wang H., Peng J., Gibbs R.A., Lewis R.A., Lupski J.R., Mardon G., Chen R. Mutation survey of known LCA genes and loci in the Saudi Arabian population. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2589. Published online October 20, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo D.C., Milewicz D.M. Methodology for using a universal primer to label amplified DNA segments for molecular analysis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2003;25:2079–2083. doi: 10.1023/b:bile.0000007075.24434.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkinson D.G., Nieto M.A. Detection of messenger RNA by in situ hybridization to tissue sections and whole mounts. Methods Enzymol. 1993;225:361–373. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(93)25025-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coulondre C., Miller J.H., Farabaugh P.J., Gilbert W. Molecular basis of base substitution hotspots in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1978;274:775–780. doi: 10.1038/274775a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsanis N., Eichers E.R., Ansley S.J., Lewis R.A., Kayserili H., Hoskins B.E., Scambler P.J., Beales P.L., Lupski J.R. BBS4 is a minor contributor to Bardet-Biedl syndrome and may also participate in triallelic inheritance. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:22–29. doi: 10.1086/341031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inoue K., Khajavi M., Ohyama T., Hirabayashi S., Wilson J., Reggin J.D., Mancias P., Butler I.J., Wilkinson M.F., Wegner M. Molecular mechanism for distinct neurological phenotypes conveyed by allelic truncating mutations. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:361–369. doi: 10.1038/ng1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khajavi M., Inoue K., Lupski J.R. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay modulates clinical outcome of genetic disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;14:1074–1081. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X., Liu H., Zhang Y., Qiao Y., Miao S., Wang L., Zhang J., Zong S., Koide S.S. A novel gene, RSD-3/HSD-3.1, encodes a meiotic-related protein expressed in rat and human testis. J. Mol. Med. 2003;81:380–387. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0434-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.