Abstract

This study was designed to investigate if the kappa opioid system regulates the locomotor response to cocaine in the female rat and to determine if the effect is dependent on estradiol treatment. Adult rats were ovariectomized (OVX) and half received an estradiol (OVX-EB) implant. After a week, rats were injected for 5 consecutive days with vehicle or with the KOPr agonist U-69593 (0.16 mg/kg, 0.32 mg/kg, 0.64 mg/kg) 15 min prior to cocaine injection (15 mg/kg). Following a 7 day drug free period, rats were challenged with cocaine (Day 13). The locomotor response to cocaine was measured on days 1, 5 and 13.

U-69593 (0.32 mg/kg) decreased cocaine-induced locomotor activity in drug naïve OVX and OVX-EB rats. These results indicate that the acute effects of U-69593 are independent of estradiol treatment. Repeated exposure to U-69593 (0.32 mg/kg) prior to cocaine decreased the development of behavioral sensitization in OVX-EB rats. This decrease in cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion persisted after one week of cocaine withdrawal. These data indicate that the KOPr system participates in estradiol modulation of cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in the female rat.

Keywords: Cocaine, Behavioral Sensitization, Female Rats, Estrogen, Estradiol, Kappa Opioid Receptors

Introduction

In the female, the gonadal hormone estrogen modulates many behaviors and physiological processes besides those associated with reproduction (Segarra & Lee, 2004). One of these is the locomotor response to psychostimulants such as amphetamine and cocaine (Peris et al., 1991; Pittman & Fibiger, 1983; Sell et al., 2000; Sircar & Kim, 1999). Repeated administration of psychostimulants results in a progressive increase in locomotion, referred to as sensitization. Sensitization can persist for months after the cessation of drug administration and it has been implicated in drug-craving and relapse to addiction (Spanagel & Weiss, 1999); (Robinson & Berridge, 2003). Ovariectomy decreases behavioral sensitization to cocaine and amphetamine (Haney et al., 1994; Robinson, 1984; Sell et al., 2000) whereas ovariectomized (OVX) rats primed with estradiol (OVX-EB) show higher behavioral sensitization than OVX rats (Febo et al., 2003; Hu & Becker, 2003). The mechanism by which estrogen modulates the locomotor response to cocaine has been the subject of several studies.

Evidence shows that estrogen modulates the activity of many neurotransmitter systems associated with addictive behavior such as the dopaminergic (Thompson & Moss, 1997; Kuppers et al., 2000), serotonergic (Abizaid et al., 2005), GABAergic (Febo & Segarra, 2004) and opioid systems (Febo et al., 2002). Recent data with fMRI demonstrate that estradiol-treated female rats sensitized to cocaine show enhanced BOLD activity in brain areas of the reward pathway (Febo et al., 2005), suggesting that estradiol alters the activity of neurotransmitter and/or neuropeptide systems of the reward pathway, which may enhance the behavioral response to cocaine.

The endogenous opioid system modulates the response to psychostimulants. Studies with male rodents show that administration of the non-selective opioid antagonist naloxone attenuates cocaine self-administration and conditioned place preference (Kuzmin et al., 1997; Kiyatkin & Brown, 2003), and delays initiation of cocaine self-administration (Kiyatkin & Brown, 2003). Several studies indicate that mu opioid receptor agonists enhance the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine and this is attenuated by administration of kappa receptor agonists (Spealman & Bergman, 1992; Shippenberg et al., 2001; Chefer et al., 2005).

Estrogen modulates the endogenous opioid system in a sex specific manner in several hypothalamic (Segarra et al., 1998; Romano et al., 1990; Hammer, Jr. et al., 1994) and mesolimbic brain areas that are associated with behavioral reinforcement, such as the striatum (Xiao et al., 2003), cingulate cortex (Jezierski & Sohrabji, 2003) and VTA (Kritzer, 1997). Previous studies show that estrogen increases preproenkephalin (Segarra et al., 1998; Quinones-Jenab et al., 1997) and pro-opiomelanocortin (Hammer et al., 1994) mRNA levels in the forebrain and mesolimbic system of adult rodents. In contrast, estrogen decreases preprodynorphin mRNA levels in tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons (Wagner et al., 1994). These data suggest that estrogen may interact with the endogenous opioid system to regulate addictive behavior in females. Studies from our laboratory have shown that, in OVX-EB rats, naloxone increases the locomotor response to a single cocaine injection, an effect not observed in OVX rats (Febo et al., 2002).

In male rats, administration of a kappa opioid receptor (KOPr) agonist blocks cocaine-self-administration (Schenk et al., 2001) as well as behavioral sensitization to cocaine (Shippenberg & Rea, 1997). However, the role of KOPrs in locomotor sensitization to cocaine in female rodents has not been examined. This study was designed to investigate if the kappa opioid system regulates the locomotor response to cocaine in the female rat and to determine if the effect is dependent on estradiol treatment. The selective KOPr agonist, U-69593, was administered to ovariectomized female rats with and without estradiol replacement and the locomotor response to cocaine was recorded. We report here that U-69593 diminished the development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine in female rats, and its effects are dependent on estradiol treatment.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (180-220g) were purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY, USA). Animals were housed in groups of 2 or 3 in a temperature and humidity controlled room, maintained on a 12L:12D light-dark cycle with lights off at 5 PM. Water and Harlan Tek rat chow were provided ad libitum. Animals were allowed a 5 day acclimation period before any experimental manipulation. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus and adhere to USDA, NIH and AAALAC guidelines.

Drugs and chemicals

The anesthetics used for surgery were ketamine (56mg/kg) and xylaxine (7mg/kg) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Cocaine-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected at a dose of 15 mg/kg at a concentration of 1.5 mg per 0.1ml. These drugs were injected intraperitoneally and prepared in 0.9% sterile saline. The selective kappa opioid receptor agonist, U-69593 (Sigma-Aldrich), was administered subcutaneously (0.16 mg/kg, 0.32 mg/kg and 0.64 mg/kg), and prepared in 25% propylene glycol (Sigma-Aldrich), which served as our vehicle control.

Surgical procedures

Animals underwent bilateral ovariectomy under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. A 5-mm Silastic tubing implant (inner diameter 1.47 mm, outer diameter 1.97 mm, Dow Corning) was prepared (Legan et al., 1975) and placed subcutaneously in the midscapular region. Half of the animals received empty implants (OVX group) and the others received implants packed with crystalline estradiol benzoate (OVX-EB group). Plasma estradiol levels produced by these implants approximate 140 pg/ml (Febo et al., 2002), and are in the high range of those observed during proestrous. After 7 days of recovery, animals were submitted to behavioral testing.

Behavioral Apparatus

Horizontal and rearing activity were measured with an automated animal activity cage system (Versamax™ system) purchased from AccuScan Instruments (Columbus, Ohio, USA). The system consisted of ten activity cages made from clear acrylic (42 cm × 42 cm × 30 cm) with 16 equally spaced (2.5 cm) infrared beams across the length and width of the cage at a height of 2 cm from the cage floor (horizontal beams). An additional set of 16 infrared beams were located at a height of 10 cm from the cage floor (rearing activity). The beam information is sent to a computer that displays beam data through a Windows based program (Versadat™). Animal activity was classified as rest, horizontal or rearing. The Versamax™ system differentiates between horizontal, stereotyped or rearing activity based on sequential breaking of different horizontal beams, the same beams or vertical beams respectively.

Behavioral Tests

From days 1-5, rats received a daily injection of saline, U-69593, or cocaine at the same time each day. Locomotor activity was recorded on days 1, 5 and 13. The locomotor response to cocaine was measured in an isolated room with low illumination. The day prior to cocaine injections, animals were habituated to the activity cages for 60 min and locomotor activity recorded (day 0). On days 1 and 5, rats were placed for 30 min in the activity cages and locomotor activity was recorded. This served to reduce novelty-induced activity and to determine basal locomotor activity. Rats were then injected with vehicle (25% propylene glycol) or U-69593 (0.16 mg/kg, 0.32 mg/kg or 64 mg/kg) and locomotor activity recorded. After 15 min, rats were injected with saline or cocaine and locomotor activity recorded for 60 additional min. To summarize, on days 1 and 5, locomotor activity was recorded for 105 min: 30 min of habituation, 15 min post vehicle or U-69593 injection, and 60 min post saline or cocaine injection. Previous studies have shown that 15 min are sufficient to allow for kappa opioid receptor occupation by the agonist (Heidbreder et al.,1993; Shippenberg et al., 2001). This injection regime was repeated for 5 consecutive days (days 1-5), although behavior was recorded only on days 1 and 5. During the following 7 days, rats were maintained in their home cages with no further injections (days 6-12). This time frame is the minimum necessary to study the persistent neurochemical changes produced by repeated cocaine administration (Pierce & Kalivas, 1997). On day 13, rats were habituated to the activity cage for 30 min, challenged with either a saline or cocaine injection, and their locomotor response was measured for the following 60 min. During the challenge, rats did not receive an injection of the KOPr opioid agonist. Each session of behavioral testing consisted of at least one animal from each OVX and OVX-EB injection groups: VEHICLE, U-69593, COCAINE and U-69593/COCAINE. This design minimizes intergroup variation that may result from differences in time of testing and/or injections.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis used varied according to the behavior and the groups to be compared. A “Repeated measures ANOVA” was used to compare differences among a single repeated measure (horizontal or rearing activity at different time points) using hormone (OVX vs OVX-EB; Fig 1), or treatment (saline, cocaine, U-69593 or cocaine+U-69593; Figs. 4, 5, and 6) as categorical predictors. A one-way ANOVA was used to determine the effect of a single grouping variable (cocaine; Fig. 2 and Fig 7) on a dependent variable (mean horizontal or rearing activity). Main effects ANOVA was used to determine the effect of multiple dosages (0, 0.16, 0.32 and 0.64 mg/kg) of a single independent variable (dose of U-69593) (Fig. 3) on a dependent variable (mean horizontal activity). Least Significance DifferenceTest (LSD) was used for post-hoc comparisons accordingly. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica© software (Stat-Soft Inc; Tulsa, OK). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

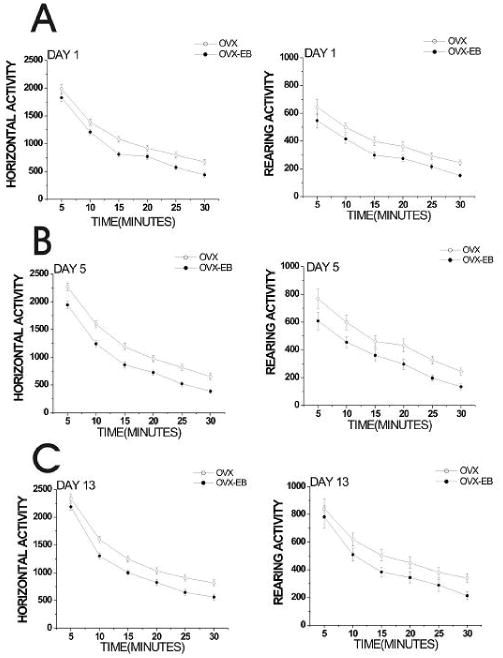

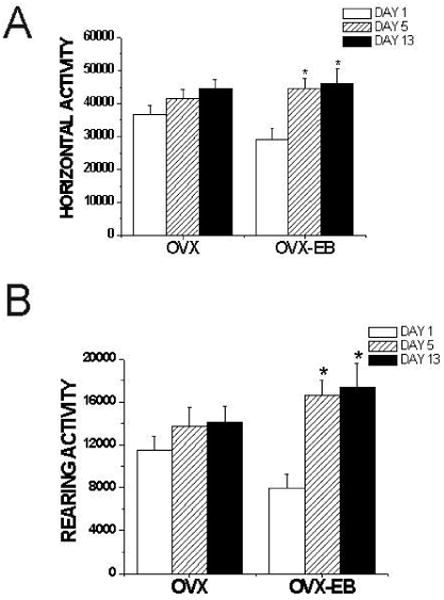

Figure 1. Basal locomotor activity displayed by OVX and OVX-EB rats.

Horizontal and rearing activity of rats was recorded for 30 min on days 1, 5 and 13, prior to drug administration. OVX-EB rats (n=89) showed lower horizontal and rearing activity than OVX rats (n=96). Data was analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA with estradiol treatment (OVX vs OVX-EB) as the independent variable and Horizontal or Rearing activity (in 5 minute intervals) as the dependent variable. Data is presented as the mean ± S.E.M. (Horizontal activity: Day 1: F(6,178)=3.81, p=0.001; Day 5: F(6,164)=4.88, p=0.0001; Day 13: F(6,172)= 4.11, p=0.0007; Rearing activity: Day 1: F(6,176)=3.00, p=0.008; Day 5: F(6,172)=3.53, p=0.003, Day 13: F(6,172)=3.89, p=0.001).

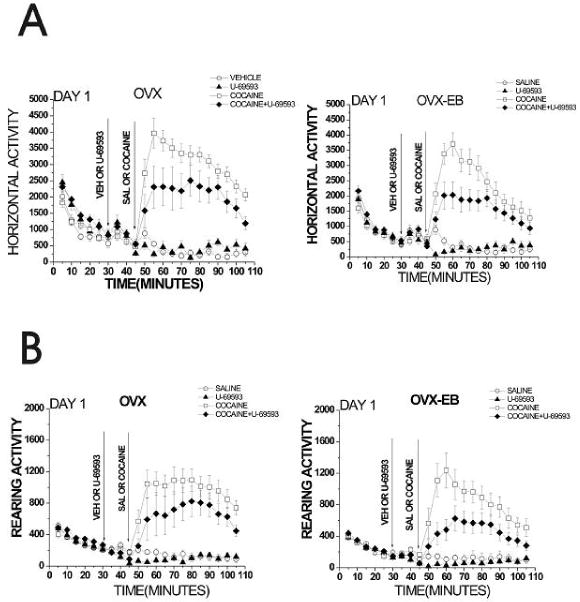

Figure 4. Horizontal and rearing activity of female rats pretreated with U-69593 that received a single cocaine injection.

Rats were habituated to activity cages for 30 min, and received an injection of vehicle (25% propylene glycol) or U-69593(0.32 mg/kg) followed 15 min later by a saline or cocaine injection (15 mg/kg). Horizontal and rearing activity was recorded for 105 min. An interaction of cocaine vs estradiol treatment was observed, with OVX rats showing a greater response to cocaine on day 1 than OVX-EB rats (F(12,86)=2.01, p=0.04). U-69593 decreased cocaine-induced horizontal activity independently of estrogen plasma levels, whereas rearing activity decreased only in OVX-EB rats. A Repeated Measures ANOVA was used to analyze data, using treatment (saline, U-69593, cocaine and cocaine+U-69593) as the independent variables and horizontal or rearing activity after cocaine injection (min 50-105) as the dependent variable. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (Horizontal activity: OVX: F(12,41)= 2.18, p=0.03; OVX-EB: F(12,40)= 2.99, p=0.01. Rearing activity: OVX: F(12,41)= 1.86 p=0.07; OVX-EB: F(12,35)= 3.73, p=0.001).

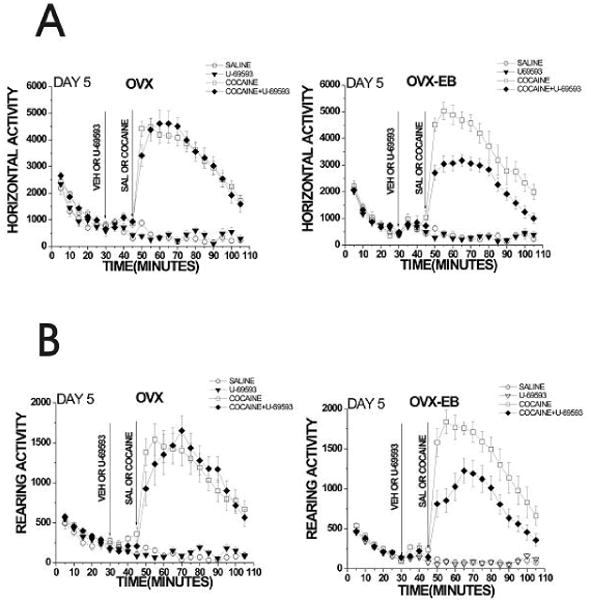

Figure 5. A daily injection of U-69593 (0.32mg/kg), for five consecutive days decreases cocaine-induced hyperactivity in OVX-EB rats.

Rats were injected for five consecutive days with U-69593 (0.32mg/kg) or its vehicle (25% propylene glycol) and after 15 minutes injected either with saline or cocaine (15mg/kg). Horizontal and rearing activity was recorded for 105 min). U-69593 decreased cocaine-induced locomotor activity only in OVX-EB rats. A Repeated Measures ANOVA was used to analyze data, using treatment (saline, U-69593, cocaine and cocaine+U-69593) as the independent variables and horizontal or rearing activity after cocaine injection (min 50-105) as the dependent variable. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (Horizontal activity: OVX: F(12,41)= 1.51, p=0.17; OVX-EB: F(12,30)= 2.64, p=0.01. Rearing activity: OVX: F(12,41)= 1.85 p=0.10; OVX-EB: F(12,32)= 2.26, p=0.03).

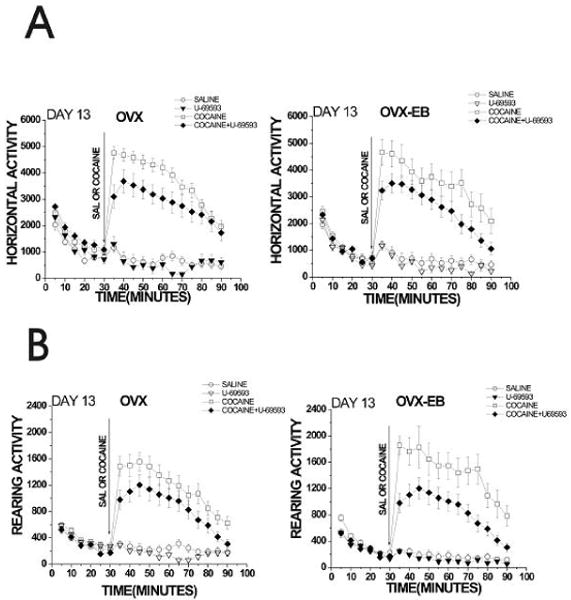

Figure 6. Pretreatment with U-69593 (0.32mg/kg), decreased locomotor response to a cocaine challenge after one week of drug-free period in OVX and OVX-EB rats.

After 1 week of drug free period, rats were habituated to the activity cages for 30 minutes and then injected with either saline or cocaine (15mg/kg). Animals previously treated with U-69593(0.32mg/kg) show lower cocaine-induced locomotor activity than animals that received vehicle. This decrease in locomotor activity on Day 13 is observed in both OVX and OVX-EB rats. A Repeated Measures ANOVA was used to analyze data, using treatment (saline, U-69593, cocaine and cocaine+U-69593) as the independent variables and horizontal or rearing activity after cocaine injection (min 50-105) as the dependent variable. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. (Horizontal activity: OVX: F(12,40)= 2.28, p=0.03; OVX-EB: F(12,31)= 2.74, p=0.01. Rearing activity: OVX: F(12,40)= 2.28 p=0.02; OVX-EB: F(12,35)= 3.68, p=0.001).

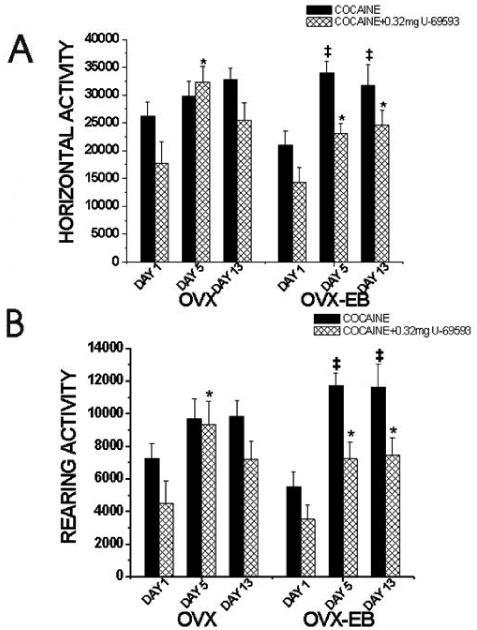

Figure 2. Cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in OVX and OVX-EB rats.

Animals were injected for 5 consecutive days with cocaine (15mg/kg). After one week, they were challenged with a cocaine injection (15mg/kg) and locomotor activity recorded. Only ovariectomized rats treated with estradiol (OVX-EB) became sensitized to cocaine. Data was analyzed using a One-way ANOVA with Time (Day 1, 5 and 13) as the independent variable and Horizontal or Rearing activity as the dependent variable. Data is presented as the mean ± S.E.M. (Horizontal activity: OVX: F(2,56)= 2.24, p=0.116 OVX-EB F(2,27)=7.13, p=0.003; Rearing activity: OVX: F(2,39)= 0.811, p=0.451, OVX-EB: F(2,21)=6.67, p=0.006). Asterisk (*) indicates this value is significantly different from Day 1.

Figure 7. U-69593 diminished the development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine in OVX-EB rats.

Only OVX-EB rats show development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine after five consecutive days of cocaine injections. Data were analyzed separately (OVX or OVX-EB) using a One-way ANOVA with DAY as the independent variable and horizontal or rearing activity as dependent variable. (‡) mean significantly different from animals that received cocaine on Day 1. OVX rats do not show behavioral sensitization to cocaine. (OVX: HACTV: F(2,41)=1.84, p=0.17; RACTV: F(2,41)=2.14 p=0.131). Only OVX-EB rats show behavioral sensitization. (OVX-EB: HACTV: F(2,21)=6.65, p=0.006; RACTV: F(2,21)=12.59 p=0.0002). (*) mean significantly different from animals that received U-69593+Cocaine on Day 1. OVX rats that received U-69593+Cocaine for five consecutive days (Day 5) show a higher locomotor than animals that received U-69593+Cocaine on Day 1. (OVX: HACTV: F(2,39)=5.00, p=0.008; RACTV: F(2,39)=3.36, p=0.04). OVX-EB rats treated with U-69593+Cocaine for five consecutive days (Day 5) exhibited higher activity than animals that received U-69593+Cocaine on Day 1. (OVX-EB: HACTV: F(2,45)=5.26, p=0.01; RACTV: F(2,45)=5.01, p=0.02). The behavioral sensitization exhibited by OVX-EB rats that received U-69593+Cocaine is lower than animals that received cocaine. Each bar represents mean ± S.E.M.

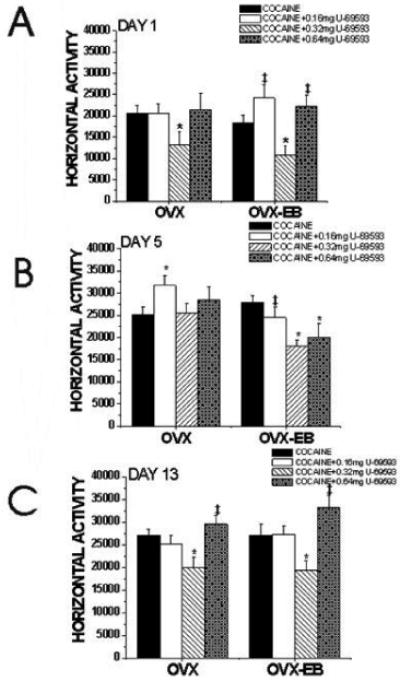

Figure 3. Effective dose of the selective kappa opioid receptor agonist, U-69593, on cocaine-induced locomotor activity and behavioral sensitization in female rats.

OVX and OVX-EB rats were injected for five consecutive with vehicle (25% propylene glycol) or U-69593(0.16mg/kg, 0.32mg/kg, 0.64mg/kg). After 15 minutes, all animals received a cocaine injection (15mg/kg). After 1 week, rats received an injection of cocaine (15mg/kg). Horizontal activity was recorded on days 1, 5 and 13 during the first 30 minutes following the cocaine injection. 0.32mg/kg U-69593 was effective in diminishing cocaine-induced locomotor activity in OVX-EB rats at all days tested, indicating that is diminished behavioral sensitization to cocaine. The dose of 0.64mg/kg U-69593 diminished cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion only on day 5, suggesting that it is effective in diminishing development of behavioral sensitization. In OVX rats, 0.32mg/kg U-69593 diminished cocaine-induced horizontal activity on day 1 and day 13. OVX and OVX-EB data were analyzed separately using a One-way ANOVA using U-69593 dose as the independent variable and Horizontal Activity as the dependent variable. A Two-way ANOVA using estradiol (OVX vs OVX-EB) and U-69593 dose (0 mg/kg (vehicle), 0.16 mg/kg, 0.32mg/kg or 0.64mg/kg) as the independent variables indicate that there is no interaction between estradiol treatment and dose of U-69593(F(3,99)= 0.608, p=0.611). Least Significance Difference test (LSD) was used for post-hoc comparisons. Data is presented as the mean ± S.E.M. (OVX: Day 1: F(3,53) = 2.17, p=0.102 Day 5: F(3,50) = 2.00, p=0.125, Day 13: F(3,50) = 4.58, p=0.006. OVX-EB: Day 1: F(3,46)= 6.48, p=0.0009; Day 5: F(3,43)= 4.34, p=0.009; Day 13: F(3,43)= 6.93, p=0.0007). (*) indicates a significant difference from animals that only received cocaine. (‡) indicates a significant difference from animals that received 0.32mg/kg U-69593.

Results

Estradiol and basal locomotor activity

Comparisons of horizontal and rearing activity show that OVX-EB rats display less horizontal and rearing activity during the first 30 min prior to drug injection than OVX rats at all days tested (Fig. 1). This difference in basal locomotor activity was observed in drug naïve rats (day 1) and was maintained after receiving cocaine or saline injections (days 5 and 13) (Fig 1).

Estradiol and cocaine-induced locomotor activity

Repeated cocaine administration induced behavioral sensitization to cocaine only in ovariectomized females treated with estradiol (Fig. 2 and 7). This was evident by the increased horizontal and rearing activity displayed by OVX-EB rats on days 5 and 13, compared to day 1. Although horizontal and rearing activity of OVX rats was higher on days 5 and 13, this increase was not significantly different from that of day 1 (Fig. 2 and 7). These data confirm previous results that estradiol potentiates behavioral sensitization to cocaine.

U-69593 dose and behavioral sensitization to cocaine

A dose response experiment was conducted to determine the dose of U-69593 that would modulate the locomotor response to cocaine in female rats. Figure 3 shows a U-shaped dose response of OVX and OVX-EB rats, especially on days 1 and 13. The dose of 0.32 mg/kg was effective in diminishing the locomotor response to cocaine in OVX-EB rats at all days tested (Fig. 3). In OVX rats, U-69593 diminished cocaine-induced locomotor activity at days 1 and 13. Intriguingly, the dose of 0.16 mg/kg increased the locomotor response to cocaine of OVX rats on day 5; a similar trend was observed in OVX-EB rats on day 1 (Fig. 3).

U-69593 and behavioral sensitization to cocaine

A single cocaine injection increased horizontal and rearing activity of all female rats tested (Fig. 4). An interaction of cocaine vs hormone treatment was observed, with OVX rats showing a greater locomotor response to cocaine on day 1 than OVX-EB rats (Figure 4). Administration of U-69593 decreased cocaine-induced horizontal activity in OVX and OVX-EB rats (Fig. 4 and 7). Rearing behavior was decreased; however, this decrease was significant only in OVX-EB rats (Fig. 4).

OVX-EB rats that were injected with U-69593 and cocaine for 5 consecutive days displayed lower cocaine-induced horizontal and rearing activity than rats treated only with cocaine (Fig. 5). These data show that in OVX-EB rats, U-69593 diminished cocaine-induced hyperactivity. In contrast, OVX rats that received U-69593 prior to cocaine displayed the same horizontal and rearing activity than those that received only cocaine. OVX-EB rats treated with U-69593+Cocaine also showed an increase in cocaine-induced hyperactivity when compared to that displayed on day 1 (Figure 7). Curiously, OVX rats that received U-69593 prior to cocaine show an increase in cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion compared to day 1, but no difference was observed if you compare these animals to those that received only cocaine.

This same pattern was maintained in OVX-EB rats following a 7 day drug free period and challenged with cocaine on day 13 (Fig. 6 and 7). Horizontal activity in response to cocaine was much higher in OVX-EB rats on day 13 than on day 1 (Fig. 2 and 7). OVX-EB rats that received U-69593 during days 1-5 and were challenged with cocaine on day 13 showed a lower response to cocaine on day 13 than rats that received only cocaine during days 1-5 (Fig. 6). It is important to notice that U-69593 was not administered to the animals on day 13, thus this experiment only tested the effect of U-69593 on the development of behavioral sensitization.

If we compare cocaine-induced horizontal and rearing activity between OVX and OVX-EB rats on days 1, 5 and 13 (Fig. 7), it is evident that U-69593 decreases the locomotor response to cocaine at all days tested in OVX-EB rats. In OVX rats, however, the effect is limited to day 1 (to drug naïve rats) and day 13 (after 1 week of drug-free period) (Figs. 4, 6 and 7).

Discussion

In this study we show that the effect of the selective KOPr agonist, U-69593, on cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion varies with dose, estradiol treatment and with exposure, i.e. if the drug is administered acutely or repeatedly for 5 days. The U-69593 dose of 0.32 mg/kg was effective in decreasing cocaine-induced hyperactivity of rats that received estradiol replacement at all time points (day 1, 5 and 13) tested. U-69593 induced a downward shift in the response to cocaine, indicating that it curtails the maximal locomotor response to cocaine in females that received estradiol. However, in OVX rats, the reduction of cocaine-induced hyperlocomotion occurs on days 1 and 13. In summary, administration of the KOPr agonist diminished cocaine-induced locomotor activity on day 1 and day 13 independent of estradiol treatment. In addition, U-69593 was effective in diminishing behavioral sensitization to cocaine in OVX-EB rats. These data show that in females, KOPr agonists are effective in blocking estradiol potentiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine.

In males, administration of a KOPr agonist prior to cocaine injection attenuates behavioral sensitization to cocaine (Shippenberg & Rea, 1997); (Shippenberg et al., 2001), conditioned place preference (Shippenberg et al., 1996), compulsive cocaine seeking (Schenk et al., 1999) and curtails the increase in dopamine produced by repeated cocaine administration (Heidbreder & Shippenberg, 1994., Chefer et al., 2005). The mesolimbic dopaminergic circuit is one of the major systems associated with the increase in locomotor activity induced by cocaine (Anderson & Pierce, 2005; Schmidt et al., 2005). Cocaine binds to the dopamine transporter (DAT) and blocks dopamine reuptake by midbrain dopaminergic terminals, resulting in increased dopamine levels in the NAc. These higher DA levels are responsible for the increase in locomotor activity associated with psychostimulant administration, which are important for the development of behavioral sensitization, and with cocaine's rewarding effects (Koob et al., 1998).

KOPrs are located on VTA dopaminergic neurons as well as on dopaminergic terminals in the NAc, and may be adjacent to DAT (Svingos et al., 2001). It is well documented that the KOPr system regulates DA levels in the NAc (Thompson et al., 2000; Chefer et al., 2005). These findings are supported by studies showing that systemic administration of KOPr agonists (Spanagel et al., 1992) and of dynorphin into the NAc (Shippenberg & Rea, 1997), reduce DA levels. In addition, experiments with KOPr knockout mice show enhanced basal and cocaine-induced DA levels compared to wild types (Chefer et al., 2005).

In male rats, a U-69593 dose range of 0.04mg/kg to 0.32mg/kg decreases cocaine induced place preference and behavioral sensitization (Shippenberg et al 1996., 1998; Heidbreder et al 1995, Vanderschuren et al 2000). However, in this study we observed that the intermediate dose of 0.32mg/kg was most effective in reducing cocaine-induced locomotor activity in females at all days tested (On day 1 and 13 for OVX and OVX-EB rats; and days 1, 5 and 13 for OVX-EB rats).

Injection of 0.16 mg/kg, 0.32 mg/kg and 0.64 mg/kg produced a U-shaped pattern of horizontal activity, particularly at days 1 and 13. Biphasic effects of kappa ligands have been reported previously for cocaine-induced locomotor activity (Heidbreder et al., 1995) and extracellular DA in the NAc (Spanagel et al., 1992).These results may reflect changes in receptor sensitivity, binding to other receptors (such as sigma receptors) desensitization of receptors, among others. Heidbreder et al (1995) showed that higher doses of U-69593 (0.32mg/kg vs 0.16mg/kg) were less effective than lower doses in reducing cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization. It is interesting that in female rats only 0.32 mg/kg of U-69593 was effective in reducing cocaine-induced locomotor activity at all day tested. It is noteworthy that on day 13, animals did not receive the KOPr agonist.

Recent studies show that administration of 0.6mg/kg of U-69593 attenuated seizures induced by acute or repeated administration of the GABA-A receptor antagonist, PTZ, but not of seizures induced by cocaine (Kaminski et al 2007). The authors suggest that the anticonvulsant effects of KOPr may decrease depolarization and thus reduce bursting activity induced by GABA-A inhibition (Kaminski et al 2007), suggesting interactions with other receptors. Further neurochemical studies are necessary to elucidate KOPr mechanisms in modulating the response to cocaine.

One could argue that the decrease in cocaine-induced locomotor activity induced by 0.32 mg/kg of U-69593 is an effect of the agonist on basal dopamine and/or basal locomotor activity. Indeed, we observed that U-69593 (0.32 mg/kg) decreased basal locomotor activity in OVX and OVX-EB drug naïve rats (Fig. 4). Studies in males show that acute blockade of KOPr increased DA levels in the NAc (Spanagel et al., 1992). However, in the current study, U-69593 was effective in diminishing cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization only in OVX-EB rats, i.e. those that became sensitized after repeated cocaine injection, suggesting that U-69593 prevents the further increase in locomotor activity that is observed after repeated cocaine injection.

The initial response to cocaine of OVX-EB rats decreases more abruptly than in OVX rats (Figures 4, 5, and 6). Cocaine-induced horizontal activity is sustained for a longer time period in OVX rats, thus overall basal horizontal activity is slightly higher than that of OVX-EB rats on day 1 (Figures 2 and 7). Although there is an increase in locomotor activity at day 5 and day 13, there is no significant difference from day 1. In fact, cocaine-induced horizontal activity on days 5 and 13 is very similar between OVX and OVX-EB rats. What is strikingly different is that in OVX-EB rats, U-69593 decreased the locomotor response to cocaine on days 1, 5 and 13 (Fig 7). However, even OVX-EB rats that received U-69593 prior to cocaine showed an increase in the behavioral response to cocaine over time (Fig. 7). Thus, comparing U-69593 rats among themselves, these rats become sensitized to cocaine although their response to cocaine is approximately 30% lower than that of rats treated with cocaine.

Sex differences in opioid antinoception have been reported (Negus & Mello, 1999; Craft, 2003). Several studies indicate that women show greater opioid analgesia than men (Fillingim & Gear, 2004), whereas studies in rodents tend to indicate greater opioid analgesia in males (Stoffel et al., 2005). Other studies have observed that in female rodents, gonadectomy tends to increase opioid antinociception whereas estradiol treatment decreases opioid antinociception (Craft et al., 2004); (Stoffel et al., 2005), decreases inhibition of mu opioid agonists and increases inhibition of kappa opioid agonists in response to noxious somatic stimuli (Ratka & Simpkins, 1991; Dawson-Basoa & Gintzler, 1996). Clearly these data show that sex steroids alter the expression of opioid peptides and receptors and in this way modulate opioid response (Schwarz & Pohl, 1994; Hammer, Jr. et al., 1994; Segarra et al., 1998). For example, estrogen decreases pre-prodynorphin in the anterior pituitary of adult female rats, an effect blocked by concomitant administration of tamoxifen (Spampinato et al., 1995), indicating that the decrease in pre-prodynorphin may be a direct effect of estrogen on transcriptional mechanisms of this opioid peptide. It is possible that the differential effect of U-69593 in OVX and OVX-EB rats may be attributed to differences in kappa opioid receptor and/or peptide levels induced by a week of estradiol treatment. Our laboratory is currently designing experiments to explore such a possibility.

Chronic cocaine administration alters the mRNA of opioid peptides and receptors. Cocaine increases expression of preprodynorphin in the striatum (Hurd & Herkenham, 1992; Spangler et al., 1993; Daunais et al., 1993; Adams et al., 2000) and of dynorphin in other limbic brain structures (Spangler et al., 1997); (Sivam, 1989). Other authors report that binge cocaine administration increases kappa and mu opioid receptor density in several structures of the reward system (Unterwald et al., 1992; Unterwald et al., 1994). Several laboratories propose that this increase in KOPr function induced by repeated cocaine administration is a homeostatic mechanism to compensate for changes brought about by repeated cocaine administration (Chefer et al., 2005). Indeed, loss of an endogenous KOPr system, as found in KOPr knockout mice, results in chronically sensitized animals (Chefer et al., 2005). In our studies we find that females without estradiol do not become sensitized to cocaine. It is possible that in OVX rats, this homeostatic compensatory mechanism does not need to be activated, thus U-69593 is without effect. However, this possibility needs to be further explored.

To summarize, U-69593 decreases the response to a single cocaine injection, independent of estradiol treatment. However, it is effective in decreasing the locomotor response to repeated cocaine administration only in OVX-EB rats. It is possible that in females, as previously suggested in males, activation of the KOPr system may be a homeostatic mechanism that may attenuate the development of addictive behavior in OVX-EB rats.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/bne/

Reference List

- Abizaid A, Mezei G, Thanarajasingam G, Horvath TL. Estrogen enhances light-induced activation of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1536–1546. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams DH, Hanson GR, Keefe KA. Cocaine and methamphetamine differentially affect opioid peptide mRNA expression in the striatum. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2061–2070. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SM, Pierce RC. Cocaine-induced alterations in dopamine receptor signaling: implications for reinforcement and reinstatement. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chefer VI, Czyzyk T, Bolan EA, Moron J, Pintar JE, Shippenberg TS. Endogenous kappa-opioid receptor systems regulate mesoaccumbal dopamine dynamics and vulnerability to cocaine. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5029–5037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: “from mouse to man”. Clin J Pain. 2003;19:175–186. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft RM, Mogil JS, Aloisi AM. Sex differences in pain and analgesia: the role of gonadal hormones. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daunais JB, Roberts DC, McGinty JF. Cocaine self-administration increases preprodynorphin, but not c-fos, mRNA in rat striatum. Neuroreport. 1993;4:543–546. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199305000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Basoa ME, Gintzler AR. Estrogen and progesterone activate spinal kappa-opiate receptor analgesic mechanisms. Pain. 1996;64:608–615. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)87175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febo M, Ferris CF, Segarra AC. Estrogen influences cocaine-induced blood oxygen level-dependent signal changes in female rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1132–1136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3801-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febo M, Gonzalez-Rodriguez LA, Capo-Ramos DE, Gonzalez-Segarra NY, Segarra AC. Estrogen-dependent alterations in D2/D3-induced G protein activation in cocaine-sensitized female rats. J Neurochem. 2003;86:405–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febo M, Jimenez-Rivera CA, Segarra AC. Estrogen and opioids interact to modulate the locomotor response to cocaine in the female rat. Brain Res. 2002;943:151–161. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02748-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Febo M, Segarra AC. Cocaine alters GABA(B)-mediated G-protein activation in the ventral tegmental area of female rats: modulation by estrogen. Synapse. 2004;54:30–36. doi: 10.1002/syn.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Gear RW. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: clinical and experimental findings. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer RP, Jr, Zhou L, Cheung S. Gonadal steroid hormones and hypothalamic opioid circuitry. Horm Behav. 1994;28:431–437. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Castanon N, Cador M, Le MM, Mormede P. Cocaine sensitivity in Roman High and Low Avoidance rats is modulated by sex and gonadal hormone status. Brain Res. 1994;645:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)91651-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Shoaib M, Shippenberg TS. Development of behavioral sensitization to cocaine: influence of kappa opioid receptor agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:150–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Goldberg SR, Shippenberg TS. The kappa-opioid receptor agonist U-69593 attenuates cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in the rat. Brain Res. 1993;616:335–338. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90228-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Shippenberg TS. U-69593 prevents cocaine sensitization by normalizing basal accumbens dopamine. Neuroreport. 1994;5:1797–1800. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199409080-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Becker JB. Effects of sex and estrogen on behavioral sensitization to cocaine in rats. J Neurosci. 2003;23:693–699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00693.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd YL, Herkenham M. Influence of a single injection of cocaine, amphetamine or GBR 12909 on mRNA expression of striatal neuropeptides. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;16:97–104. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90198-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jezierski MK, Sohrabji F. Estrogen enhances retrograde transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the rodent forebrain. Endocrinology. 2003;144:5022–5029. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski RM, Witkin JM, Shippenberg TS. Pharmacological and genetic manipulation of kappa opioid receptors: effects on cocaine and pentylenetetrazol-induced convulsions and seizure kindling. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52(3):895–903. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyatkin EA, Brown PL. Naloxone depresses cocaine self-administration and delays its initiation on the following day. Neuroreport. 2003a;14:251–255. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200302100-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzer MF. Selective colocalization of immunoreactivity for intracellular gonadal hormone receptors and tyrosine hydroxylase in the ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra, and retrorubral fields in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1997;379:247–260. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970310)379:2<247::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppers E, Ivanova T, Karolczak M, Beyer C. Estrogen: a multifunctional messenger to nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. J Neurocytol. 2000;29:375–385. doi: 10.1023/a:1007165307652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin AV, Semenova S, Gerrits MA, Zvartau EE, van Ree JM. Kappa-opioid receptor agonist U50,488H modulates cocaine and morphine self-administration in drug-naive rats and mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;321:265–271. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00961-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legan SJ, Coon GA, Karsch FJ. Role of estrogen as initiator of daily LH surges in the ovariectomized rat. Endocrinology. 1975;96:50–56. doi: 10.1210/endo-96-1-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus SS, Mello NK. Opioid antinociception in ovariectomized monkeys: comparison with antinociception in males and effects of estradiol replacement. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1132–1140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris J, Decambre N, Coleman-Hardee ML, Simpkins JW. Estradiol enhances behavioral sensitization to cocaine and amphetamine-stimulated striatal [3H]dopamine release. Brain Res. 1991;566:255–264. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Kalivas PW. A circuitry model of the expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine-like psychostimulants. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:192–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman KJ, Fibiger HC. The effects of estrogen on apomorphine-induced hypothermia and stereotypy in the rat. Neuropharmacology. 1983;22:587–592. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(83)90149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Jenab V, Jenab S, Ogawa S, Inturrisi C, Pfaff DW. Estrogen regulation of mu-opioid receptor mRNA in the forebrain of female rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratka A, Simpkins JW. Effects of estradiol and progesterone on the sensitivity to pain and on morphine-induced antinociception in female rats. Horm Behav. 1991;25:217–228. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(91)90052-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE. Behavioral sensitization: characterization of enduring changes in rotational behavior produced by intermittent injections of amphetamine in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1984;84:466–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00431451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, Berridge KC. Addiction. Annu Rev Psychol. 2003;54:25–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano GJ, Mobbs CV, Lauber A, Howells RD, Pfaff DW. Differential regulation of proenkephalin gene expression by estrogen in the ventromedial hypothalamus of male and female rats: implications for the molecular basis of a sexually differentiated behavior. Brain Res. 1990;536:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)90009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Partridge B, Shippenberg TS. U69593, a kappa-opioid agonist, decreases cocaine self-administration and decreases cocaine-produced drug-seeking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;144:339–346. doi: 10.1007/s002130051016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk S, Partridge B, Shippenberg TS. Effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist, U69593, on the development of sensitization and on the maintenance of cocaine self-administration. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:441–450. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt HD, Anderson SM, Famous KR, Kumaresan V, Pierce RC. Anatomy and pharmacology of cocaine priming-induced reinstatement of drug seeking. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz S, Pohl P. Steroids and opioid receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994;48:391–402. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra AC, Acosta AM, Gonzalez JL, Angulo JA, McEwen BS. Sex differences in estrogenic regulation of preproenkephalin mRNA levels in the medial preoptic area of prepubertal rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;60:133–139. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(98)00160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segarra AC, Lee SJ. Neuroprotective effects of estrogen. In: Legato MJ, editor. Principles of Gender Specific Medicine. Vol. 1. 2004. pp. 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Sell SL, Scalzitti JM, Thomas ML, Cunningham KA. Influence of ovarian hormones and estrous cycle on the behavioral response to cocaine in female rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293:879–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Chefer VI, Zapata A, Heidbreder CA. Modulation of the behavioral and neurochemical effects of psychostimulants by kappa-opioid receptor systems. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;937:50–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, LeFevour A, Heidbreder C. kappa-Opioid receptor agonists prevent sensitization to the conditioned rewarding effects of cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;276:545–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Rea W. Sensitization to the behavioral effects of cocaine: modulation by dynorphin and kappa-opioid receptor agonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57:449–455. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, Le Favour A, Thompson AC. Sensitization to the conditioned rewarding effects of morphine and cocaine: differential effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist U69593. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;345(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01614-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sircar R, Kim D. Female gonadal hormones differentially modulate cocaine-induced behavioral sensitization in Fischer, Lewis, and Sprague-Dawley rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:54–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivam SP. Cocaine selectively increases striatonigral dynorphin levels by a dopaminergic mechanism. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;250:818–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spampinato S, Canossa M, Campana G, Carboni L, Bachetti T. Estrogen regulation of prodynorphin gene expression in the rat adenohypophysis: effect of the antiestrogen tamoxifen. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1589–1594. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.4.7895668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Herz A, Shippenberg TS. Opposing tonically active endogenous opioid systems modulate the mesolimbic dopaminergic pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:2046–2050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanagel R, Weiss F. The dopamine hypothesis of reward: past and current status. Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:521–527. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler R, Unterwald EM, Kreek MJ. ‘Binge’ cocaine administration induces a sustained increase of prodynorphin mRNA in rat caudate-putamen. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;19:323–327. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90133-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler R, Zhou Y, Maggos CE, Schlussman SD, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Prodynorphin, proenkephalin and kappa opioid receptor mRNA responses to acute “binge” cocaine. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;44:139–142. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spealman RD, Bergman J. Modulation of the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine by mu and kappa opioids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffel EC, Ulibarri CM, Folk JE, Rice KC, Craft RM. Gonadal hormone modulation of mu, kappa, and delta opioid antinociception in male and female rats. J Pain. 2005;6:261–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingos AL, Chavkin C, Colago EE, Pickel VM. Major coexpression of kappa-opioid receptors and the dopamine transporter in nucleus accumbens axonal profiles. Synapse. 2001;42:185–192. doi: 10.1002/syn.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AC, Zapata A, Justice JB, Jr, Vaughan RA, Sharpe LG, Shippenberg TS. Kappa-opioid receptor activation modifies dopamine uptake in the nucleus accumbens and opposes the effects of cocaine. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9333–9340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson TL, Moss RL. Modulation of mesolimbic dopaminergic activity over the rat estrous cycle. Neurosci Lett. 1997;229:145–148. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterwald EM, Ho A, Rubenfeld JM, Kreek MJ. Time course of the development of behavioral sensitization and dopamine receptor up-regulation during binge cocaine administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;270:1387–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterwald EM, Horne-King J, Kreek MJ. Chronic cocaine alters brain mu opioid receptors. Brain Res. 1992;584:314–318. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90912-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderschuren LJ, Schoffelmeer AN, Wardeh, De Vries TJ. Dissociable effects of the kappa-opioid receptor agonists bremazocine, U69593, and U50488H on locomotor activity and long-term behavioral sensitization induced by amphetamine and cocaine. Psychopharmacology. 2000;150(1):35–44. doi: 10.1007/s002130000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EJ, Manzanares J, Moore KE, Lookingland KJ. Neurochemical evidence that estrogen-induced suppression of kappa-opioid-receptor-mediated regulation of tuberoinfundibular dopaminergic neurons is prolactin-independent. Neuroendocrinology. 1994;59:197–201. doi: 10.1159/000126659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Jackson LR, Becker JB. The effect of estradiol in the striatum is blocked by ICI 182,780 but not tamoxifen: pharmacological and behavioral evidence. Neuroendocrinology. 2003;77:239–245. doi: 10.1159/000070279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]