Abstract

Introduction

Blood leukocytes play a major role in mediating local and systemic inflammation during acute pancreatitis. We hypothesize that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in circulation exhibit unique changes in gene expression, and could provide a “reporter” function that reflects the inflammatory response in pancreas of acute pancreatitis.

Methods

To determine specific changes in blood leukocytes during acute pancreatitis, we studied gene transcription profile of in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in a rat model of experimental pancreatitis (sodium taurocholate). Normal rats, saline controls and a model of septic shock were used as a controls. cRNA obtained from PBMC of each group (n = 3) were applied to Affymetrix rat genome DNA Gene Chip Arrays.

Results

From the 8,799 rat genes analyzed, 140 genes showed unique significant changes in their expression in PBMC during the acute phase of pancreatitis, but not in sepsis. Among the 140 genes, 57 were upregulated, while 69 were downregulated. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor, prostaglandin E2 receptor and phospholipase D1 are among the top upregulated genes. Others include genes involved in G protein-coupled receptor and TGF-β-mediated signaling pathways, while genes associated with apoptosis, glucocorticoid receptors and even the cholecystokinin receptor are downregulated.

Conclusions

Microarray analysis in transcriptional profiling of PBMC showed that genes that are uniquely related to molecular and pancreatic function display differential expression in acute pancreatitis. Profiling genes obtained from an easily accessible source during severe pancreatitis may identify surrogate markers for disease severity.

Keywords: Acute pancreatitis, oligonucleotide microarray, abdominal sepsis, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, PBMC

Introduction

Acute pancreatitis is a severe inflammatory disease frequently diagnosed by acute abdominal pain associated with a concomitant rise of serum amylase and lipase concentration. There are over 180,000 new cases per year in the United States (1). While the injury and systemic manifestations are typically mild, up to 20% of the patients will exhibit a severe reaction-typified by pancreatic necrosis- and among them, the morbidity can be over 80%, and mortality about 25% (2). The pathophysiology of the disease includes the activation and release of pancreatic enzymes within the ductal system (3-5), the autodigestion of the pancreas (6) and multiple organ dysfunction following their release into the systemic circulation. A major challenge has been to identify markers of disease severity.

It likely that the synthesis and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are responsible for progression of the local injury to the pancreas and retroperitoneum (7). Also, inflammatory mediators produced within the gland increase the pancreatic injury and spread to distant organs (8-10), transforming a local inflammation into a severe systemic disease. The mediators involved in this systemic inflammation are similar to those encountered during sepsis.

Because it is important to predict the severity of the disease as early as possible in order to optimize the therapy and to prevent organ dysfunction and local complications, several scores such as Ranson, Glasgow and the Acute Physiology Anad Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) (11-15) scores have been used. New serum markers have emerged and their ability to provide additional information on the severity of the disease has been evaluated (15).

The current prognostic indicators available for acute pancreatitis rely heavily on clinical markers combined with an increase in serum levels of proteins such as C reactive protein & trypsinogen-activation peptide. Newer proteins such as PAP (16) have not reached clinical utility as originally hoped.

Since pancreatitis is an immunologic response to the injury, we explored the possibility that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) would harbor specific markers of progression of disease. We employed gene chip microarray technology to study genetic expression patterns of PBMCs obtained from rats with pancreatitis. While typically one compares these patterns to normal controls, we further compared them to PBMCs obtained from rats with intra-abdominal bacterial sepsis, to elucidate unique patterns of expression in acute pancreatitis.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments in this study were performed with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC) of SUNY Downstate Medical Center and in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) weighing from 225-250 g were used for experiments. Animals were allowed ad libitum exposure to food and water before study, and randomly assigned to control or experimental groups.

Experimental acute pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis was induced using retrograde infusion of 4% sodium taurocholate (NaT) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) into the pancreatic duct as previously described (17). Briefly, under pentobarbital (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) anesthesia (50 mg/kg given intraperitoneally), a midline incision was performed. The common bile duct was identified and cannulated in an antegrade direction with PE-10 tubing (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) such that the proximal end of the tube was beyond the ampulla of Vater in the duodenum. The bile duct was then ligated to prevent the flow of bile and 4% NaT in sterile saline was infused into the pancreatic duct at a rate of 1 ml/kg over 10 min.

Experimental septic shock

Sepsis was induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) as described by previously described (18). Briefly, under pentobarbital anesthesia, a laparotomy was performed (the size of the incision was 2.5 cm), and the cecum was ligated just below the ileocecal valve with a 3-0 silk ligature and the antimesentric cecal surface was punctured once with a 16-gauge needle proximal to the ligature. The cecum was then returned to the peritoneal cavity and fecal content in the ligated segment was allowed to extruded through the puncture to the peritoneum. The peritoneum and abdominal muscles were closed with silk sutures. After CLP, rats were returned to cages and allowed ad libitum access to food and water. For both experimental model of acute pancreatitis or sepsis, control rats were anesthetized and sham operated with a laparotomy. Pancreas or cecum was manipulated but neither pancreatitis induction nor CLP procedure was performed.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) isolation

Twenty-four hr after pancreatitis, septic shock induction, sham operation with saline infusion or in fasted untouched, normal control animals (n =3 each group, n=12 total), approximately 8-10 mL whole blood were collected via inferior vena cava (IVC) from each rat under pentobarbital anesthesia. PBMC were isolated from rat whole blood by centrifugation through Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia, Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden) (19).

Preparationi of cRNA and GeneChip hybridization

Preparation of cRNA, hybridization, and scanning of high-density oligonucleotide microarray were performed according to manufactures's protocol (Affymetryix, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from PBMC using TRIzol (GIBCO BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and eluted using a RNeasy spin column (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia CA). Ten micrograms of total RNA was converted into double-stranded cDNA by reverse transcription using SuperScript Choice System (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) with the T7-(dT)24 primer [5′-GGC CAG TGA ATT GTA ATA CGA CTC ACT ATA GGG AGG CGG (dT24)]. The double-strand cDNA product was extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol using phase lock gels (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY). Double-strand cDNA was in vitro transcribed into cRNA and nucleotides were biotinylated using the Enzo BioArray HighYield RNA Treanscrip Labeling Kit (Affymetrix). The in vitro transcription product was further purified using RNeasy mini columns (Qiagen) and fragmented as previously described (20). Fragmented in vitro transcription product was hybridized onto the rat genome U34A DNA GeneChip Array (Affymetrix) which contains approximately 7,000 full-length sequences and 1,000 EST clusters. The sequences were selected from from the UniGene database. All 12 PBMC samples were subjected to RNA extraction and transcript profiling.

Data and statistical Analysis

An absolute expression analysis was performed using Affymetrix MAS 5.0, and the data from genes were imported into GeneSpring software version 5.1 (Silicon Genetics, Redwood City, CA) for further analyses. Differentially expressed genes were selected. Differential expression was defined as a change of at least two fold versus respective controls. Non-parametric test was used, assuming non-equal means, specifically the Welch t-test and Welch ANOVA. Significance level was set at > 2-fold change between groups, P < .05.

Results

Rats treated with NaT showed pancreatic edema and necrosis, as we have previously observed (17, 21). Those treated with CLP were not autopsied. Adequate numbers of PBMCs were obtained from each animal studied for gene array analysis.

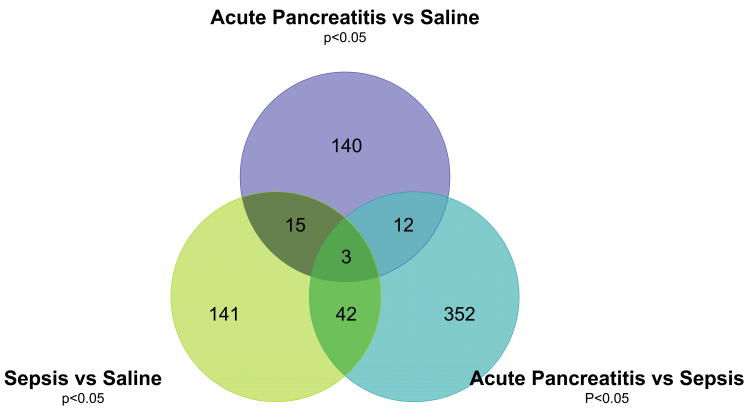

We compared gene transcription profiles of PBMCs in normal, untouched control animals, to those with acute pancreatitis, to identify those genes induced in pancreatitis (Figure 1). From the 8,799 rat gene analyzed on the chip, we identified 947 genes significantly changed by 2-fold in pancreatitis.

Figure 1.

Scatter plot of the differentially express genes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolated from rats with acute pancreatitis compared to those from normal, control, unoperated animals. The axes are arbitrary fold changes. The red points above the line are up-regulated genes, the blue ones below are down-regulated genes. 947 genes were identified and subjected to further analysis (see Figure 2).

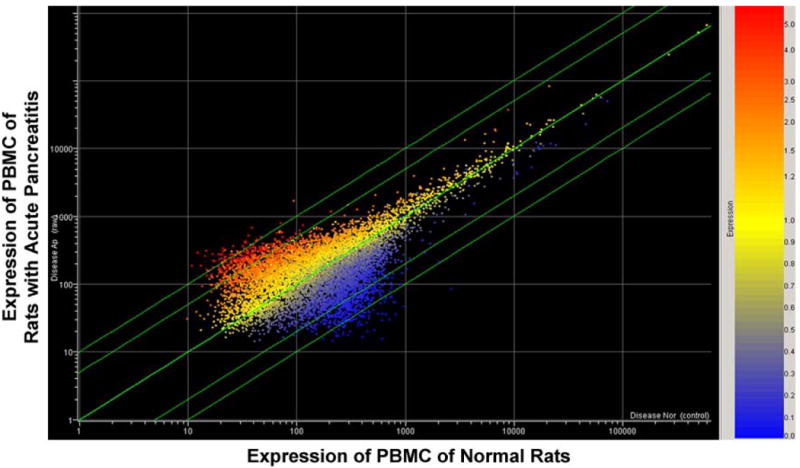

These 947 genes were then subjected to comparison between animals with acute pancreatitis and saline controls, and identified 170 genes which changed expression (Figure 2). Similarly, 201 unique genes were identified between between rats with cecal ligation and puncture (abdominal sepsis) and saline controls, and 409 differentially expressed genes were identified between animals with acute pancreatitis and intra-abdominal sepsis.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of differential expression of the 947 genes (identified in Figure 1) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Expression was compared from rats who underwent laparotomy and ductal infusion with saline, to those undergoing infusion with sodium taurocholate to induce with acute pancreatitis, to those with intra-abdominal sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture. 140 genes induced specifically during sodium taurocholate acute pancreatitis were identified, the most induced and inhibited are depicted in Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

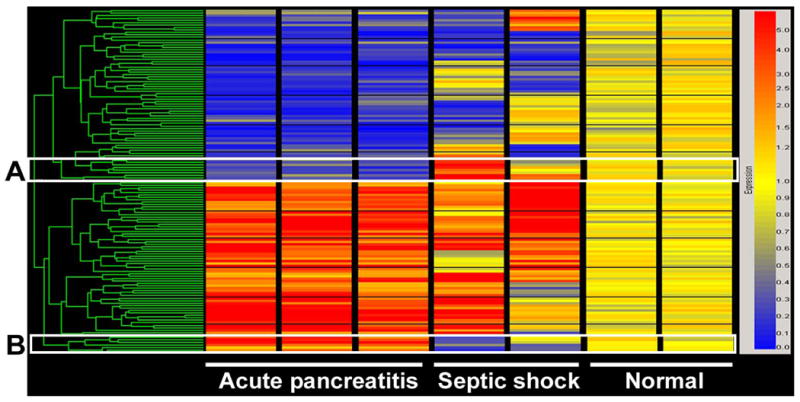

As shown in Figure 2, of the 170 genes changed between pancreatitis and saline controls, 15 overlapped when compared to septic/pancreatitic animals, and another 18 overlapped with sepsis/normal animals. In total, 140 genes were unique to PBMCs in animals with pancreatitis. Figure 3 shows a cluster analysis of the genes from the three groups analyzed in Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Cluster view of genes differentially expressed in PBMC isolated from rats with acute pancreatitis. (A.) Genes downregulated in acute pancreatitis, but upregulated in abdominal sepsis. (B.) Genes upregulated in acute pancreatitis, but downregulated in abdominal sepsis. The ‘normal’ column is RNA from saline-infused control animals.

Among the 140 genes whose expression changed in pancreatitis alone, 57 were upregulated, while 69 were downregulated; 25% corresponded to ESTs. Table 1 and 2 shows the most significantly (greater than threefold) up-regulated (n=14) and down-regulated genes (n=33), respectively, and their known functions.

Table 1.

Upregulated genes, which are differentially expressed in PBMC in acute pancreatitis, but not in septic shock or normal conditions (3×over controls, n=14).

| Fold Change | P | Genbank | Name | Description | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U11.9 | 0.02 | AF017251 | Pld1 | Phospholipase D gene 1 | intracellular signaling cascade, phospholipase D |

| U10.7 | 0.03 | AI232379 | Pdgfra | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha | protein amino acid phosphorylation, transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase |

| U6.1 | 0.03 | Y07903 | Adam3 | a disintegrin and metalloprotease domain 3 (cyritestin) | Pep_M12B_propep;metalloendopeptidase |

| U5.5 | 0.03 | U94708 | Ptger2 | prostaglandin E receptor EP2 subtype | GPCRs Class A Rhodopsin-like; Small ligand GPCRs rhodopsin-like receptor |

| U5.5 | 0.03 | U08976 | Ech1 | enoyl coenzyme A hydratase 1 | Enzyme |

| U5.0 | 0.01 | Z22867 | Pde3b | phosphodiesterase 3B | signal transduction |

| U4.6 | 0.01 | Z21935 | Mapk4 | Rat protein kinase rMNK2. | protein amino acid phosphorylation ATP binding; protein serine/threonine kinase |

| U4.3 | 0.03 | L09653 | Tgfbr2 | transforming growth factor, beta receptor 2 | TGF Beta Signaling Pathway |

| U4.3 | 0.03 | L09653 | Tgfbr2 | transforming growth factor, beta receptor 2 | pkinase;protein kinase, proteolysis and peptidolysis, subtilase |

| U3.8 | 0.03 | L07736 | Cpt1a | carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 | Fatty Acid Degradation; Mitochondrial fatty acid Betaoxidation, fatty acid metabolism, mitochondrion; membrane fraction Carn_acyltransf;acyltransferase |

| U3.5 | 0.04 | U52948 | C9 | complement component 9 | Complement Activation Classical |

| U3.4 | 0.02 | L26986 | Adcy8 | adenylyl cyclase 8 | G Protein Signaling;intracellular signaling cascade |

| U3.4 | 0.02 | J04486 | Igfbp2 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 | insulin-like growth factor binding |

| U3.4 | 0.02 | L26986 | Adcy8 | adenylyl cyclase 8 | guanylate cyclase |

Table 2.

Down-regulated genes, which are differentially expressed in PBMC in acute pancreatitis, but not in septic shock or normal conditions (3× under control, n=33).

| Fold Change | P | Genbank | Name | Description | Biological Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D10.7 | 0.04 | J00758 | Ngfg | rat pancreatic preprokallikrein | serine-type endopeptidase |

| D9.3 | 0.00 | AB017044 | Hnf3g | rat hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 gamma | regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent |

| D9.8 | 0.04 | U14647 | Casp1 | caspase 1 | proteolysis and peptidolysis |

| D9.6 | 0.05 | AA851223 | Eno3 | enolase 3, beta, muscle | Glycolysis, gluconeogenesis phosphopyruvate hydratase complex |

| D9.3 | 0.00 | AB017044 | Hnf3g | rat hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 gamma | nucleus |

| D8.8 | 0.03 | AA925846 | Bid3 | BH3 interacting domain 3 | apoptosis;inferred from mutant phenotype protein binding |

| D8.5 | 0.05 | AA874784 | Lipa | lipase A, lysosomal acid | sterol esterase |

| D7.6 | 0.02 | Y00156 | UDPGT | UDP-glucuronosyltrans ferase 2B3 precursor, microsomal | UDPGT;transferase, transferring hexosyl groups |

| D7.5 | 0.01 | L15079 | Pgy3 | P-glycoprotein 3/multidrug resistance 2 | ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter Membrane transport |

| D7.2 | 0.04 | AI137538 | Grl | glucocorticoid receptor | regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent, nuclear receptors |

| D7.2 | 0.04 | L32591 | Gadd45a | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha | Cell cycle |

| D7.2 | 0.04 | M99418 | Cckbr | Cholecystokinin B receptor | rhodopsin-like receptor |

| D7.2 | 0.04 | L32591 | Gadd45a | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha | Ribosomal_L7Ae;structural constituent of ribosome |

| D7.1 | 0.00 | AB003478 | B3galt4 | UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAc beta 1,3-galactosyltransferase | Galactosyl_T;galactosyltransferase |

| D6.6 | 0.05 | U28938 | Ptpro | protein tyrosine phosphatase, receptor type, O | transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase signaling pathway |

| D6.2 | 0.01 | S49400 | Ptpn5 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 5 | protein tyrosine phosphatase, protein amino acid dephosphorylation |

| D5.9 | 0.03 | L09120 | Capn | calpain 2 | calpain; calcium ion binding, proteolysis and peptidolysis |

| D5.6 | 0.02 | S74898 | Ptgfr | prostaglandin F2 alpha receptor | membrane |

| D5.3 | 0.01 | D16349 | Oprm1 | Opioid receptor, mu 1 | immune response, GPCRs Class A Rhodopsin-like; Peptide GPCRs, plasma membrane |

| D5.3 | 0.01 | Z22867 | Pde3b | phosphodiesterase 3B | 3′,5′-cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase |

| D4.7 | 0.03 | AA997614 | Cyp51 | Cytochrom P450 Lanosterol 14 alpha-demethylase | Monooxygenase, electron transport |

| D4.7 | 0.04 | D29766 | Crkas | v-crk-associated tyrosine kinase substrate | cell adhesion |

| D4.5 | 0.04 | AF012347 | Madh9 | MAD homolog 9 (Drosophila) | TGF Beta Signaling Pathway, MH1 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent |

| D4.5 | 0.05 | AA945583 | Hsd17b10 | hydroxysteroid (17-beta) dehydrogenase 10 | adh_short;oxidoreductase |

| D4.4 | 0.00 | M85299 | Slc9a1 | Solute carrier family 9, antiporter, Na+/H+ | G Protein Signaling, sodium transport integral plasma membrane protein, Na_H_Exchanger; solute:hydrogen antiporter |

| D4.4 | 0.00 | U33287 | Casq2 | calsequestrin 2 | calcium ion storage |

| D3.6 | 0.01 | L26110 | Tgfbr1 | transforming growth factor, beta receptor 1 | TGF Beta Signaling Pathway |

| D3.5 | 0.04 | X06564 | Ncam | neural cell adhesion molecule | cell adhesion; post-translational membrane targeting |

| D3.3 | 0.04 | X72757 | Cox6a1 | rat cox Via gene (liver). | electron transport |

| D3.3 | 0.01 | U22296 | Csnk1g1 | casein kinase 1 gamma 1 | pkinase;protein kinase |

| D3.3 | 0.04 | X72757 | Cox6a1 | R.norvegicus cox Via gene (liver). | cytochrome c oxidase |

| D3.2 | 0.02 | M64780 | Agrn | Agrin | serine protease inhibitor plasma membrane organization and biogenesis |

| D3.1 | 0.05 | U24150 | Tsc2 | Tuberous sclerosis 2, (renal carcinoma) | GTPase activator, cell growth and/or maintenance |

Discussion

Acute pancreatitis is a disease which begins with an insult followed by autodigestion of pancreatic tissue. Inflammatory cells are recruited into the organ, an inflammatory cascade is induced, and this leads to local and systemic sequelae, which can include the respiratory, immunologic and cardiac systems. 10-20% of patients will develop severe disease, and of those, up to 50% can die. While patients can die from overwhelming sepsis as a result of bacterial translocation (22,23), most patients are not infected in the first few weeks of the disease (24). Therefore, disease severity and prognostic indicators are not initially associated with bacterial infection.

The early immunologic response leads to the severe systemic reaction, and likely the subsequent morbidity. The immunologic response in acute pancreatitis is different from abdominal sepsis, since the pancreas is not invaded by bacteria at the early stages; no abscesses are seen until late, and the time lines are very different.

Predicting which patients are going to progress to severe disease has been a challenge for physicians. To date, very few serum markers have been shown to be effective predictors, and the best prognostic indicators are still the clinical parameters (2, 11-15, 24, 25). Our lab has been interested in identification of new potential markers.

One method to identify new potential markers is to map out those genes which are uniquely expressed during the disease process. To date, no one has actually studied the role of blood derived inflammatory cells as markers for pancreatic inflammation. We postulate that the response to pancreatitis, and potentially the prognostic indicator of disease severity, rests in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. These are the cells which mediate the immunologic reaction to pancreatitis. While investigators have measured gene expression of the pancreas in experimental pancreatitis (26), and others have studies changes in the population of leukocytes in pancreatitis (27), no one has studied the genetic map of PBMC during disease.

We postulated that peripheral blood mononuclear cells can serve a “reporter function” as biomarkers of acute pancreatitis, and as such would express unique genes during pancreatitis. Further, PBMC represent an easily accessible, non-invasive source of material. We employed microarray technology to asses the gene transcription profile of PBMCs in a rat model of sodium taurocholate-induced acute necrotizing pancreatitis. We first compared the profile of pancreatitic animals with pancreata from normal, unoperated controls. This identified 947 genes induced during pancreatitis. In order to determine which of these genes were uniquely expressed during pancreatitis, we compared the PBMC RNA obtained from rats induced with pancreatitis with PMBC RNA obtained from rats who underwent saline infusion alone, and with rats with intra-abdominal sepsis.

We identified 140 unique genes which were induced or inhibited in PBMCs during NaT-induced (necrotizing) pancreatic disease. Not surprisingly, some of the genes highly induced are of cytokines previously implicated in pancreatitis, such as receptors for platelet-derived factor, transforming growth factor-beta, and a variety of G-protein related signal transduction genes. The role of phospholipase D gene 1 is involved in the intracellular modulation of cellular mitogenesis and even pancreatic organ regeneration (28, 29). The prostaglandin E2 receptor is induced, which is interesting since inhibition of PGE2 by cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors improves survival (30)

Interestingly, genes associated with cell death, such as caspase 1 and BH3 interacting domain 3, and cell membrane integrity were uniquely downregulated in PBMCs of rats with acute pancreatitis. Caspase 1, associated with cellular apoptosis, has been studied in acute pancreatitis (31), its activation within the pancreas is associated with severe necrosis (32), but its inhibition may be protective in sepsis (33). BH3 domain proteins, also involved in mitochondrial-mediated cell death (34) via BCL-2 mediate apoptosis (35). How these PBMC-associated apoptosis processes relate to pancreatic necrosis remains to be studied.

What is striking is that some genes associated with the disease of pancreatitis, namely glucocorticoid receptor, cholecystokinin receptor and lipase are significantly inhibited, each by 7-fold. We have shown that glucocorticoid treatment can improve survival in animal models of pancreatitis (36), and others have described a relationship between glucocorticoids and the cholecystokinin receptor in the disease process (37). Use of either compound after the induction of the disease has not been studied.

Our data show that in acute pancreatitis, PBMCs express genes which are related to pancreatic illness and not intra-abdominal sepsis. This observation, that pancreatitis-related genes are induced in cells outside the pancreas -in peripheral blood mononuclear cells- during necrotizing pancreatitis, has not been previously described. It should not be surprising that such genes are induced- these genes were originally identified from inflamed pancreatic tissue which likely already had similar PBMCs infiltrating them. But, since the PBMCs are involved in the systemic inflammatory response to pancreatitis, following their expression/activation during the evolution of pancreatitis should be illuminating. The ability of easily accessible blood leukocytes to provide a reporter function for solid organ disease will likely prove useful in pancreatitis as we have shown in other diseases (38). Mapping the expression pattern of these genes in the clinical arena might help differentiate the patients who are suffering from mild, moderate and severe pancreatitis, including necrosis and systemic complications. Future studies will establish a panel of these genes to differentiate between sepsis, pancreatitis and severe, necrotizing pancreatitis and determine if serum concentration of these new molecular markers - obtained from cells within the blood which modulate the inflammatory response to pancreatitis - correlate to the severity of pancreatitis. If they predict occurrence of multiple organ dysfunction, it is then conceivable that these markers will predict the outcome of the disease.

References

- 1.Baron T, Morgan D. Acute Necrotizing Pancreatitis. N Eng J Med. 1999;340:1412–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley EL. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Arch Surg; Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis; Atlanta, Ga. September 11 through 13, 1992; pp. 586–901993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foitzik T, Lewandrowski KB, Fernández-del Castillo C, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL. Evidence for extraluminal trypsinogen activation in three different models of acute pancreatitis. Surgery. 1994;115:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lerch MM, Hernández CA, Adler G. Gallstones and acute pancreatitis--mechanisms and mechanics. Dig Dis. 1994;12:242–7. doi: 10.1159/000171458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senninger N, Moody FG, Coelho JC, Van Buren DH. The role of biliary obstruction in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis in the opossum. Surgery. 1986;99:688–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The cell biology of experimental pancreatitis Steer ML, Meldolesi J. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:144–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198701153160306.

- 7.De Campos T, Deree J, Coimbra R. From acute pancreatitis to end-organ injury: mechanisms of acute lung injury. Surg Infect. 2007;8:107–20. doi: 10.1089/sur.2006.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang H, Patel SA, Kandil E, Mueller CM, Lin YY, Zenilman ME. Pancreatic elastase is proven to be a mannose-binding protein--implications for the systemic response to pancreatitis. Surgery. 2003;133:678–88. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaffray C, Mendez C, Denham W, Carter G, Norman J. Specific pancreatic enzymes activate macrophages to produce tumor necrosis factor-alpha: role of nuclear factor kappa B and inhibitory kappa B proteins. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:370–7. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaffray C, Yang J, Carter G, Mendez C, Norman J. Pancreatic elastase activates pulmonary nuclear factor kappa B and inhibitory kappa B, mimicking pancreatitis-associated adult respiratory distress syndrome. Surgery. 2000;128:225–31. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranson JHC, Rifkind KM, et al. Prognostic signs and the role of operative management in acute pancreatitis. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1974;139:69–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agarwal N, Pitchumoni CS. Assessment of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:1385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corfield AP, Williamson RCN, et al. Predicition of severity in acute pancreatitis: prospective comparison of three prognostic indices. Lancet. 1985;2:403–07. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92733-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Triester SL, Kowdley KV. Prognostic factors in acute pancreatits. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:167–76. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200202000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papachristou GI, Clermont G, Sharma A, Yadav D, Whitcomb DC. Risk and markers of severe acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36:277–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iovanna JL, Keim V, Nordback I, Montalto G, Camarena J, Letoublon C, Lévy P, Berthézène P, Dagorn JC. Serum levels of pancreatitis-associated protein as indicators of the course of acute pancreatitis. Multicentric Study Group on Acute Pancreatitis. Gastroenterol. 1994;106:728–34. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zenilman ME, Tuchman D, Zheng Q, Levine J, Delany H. Comparison of reg I and reg III levels during acute pancreatitis in the rat. Ann Surg. 2000;232:646–652. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200011000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bluth MH, Kandil E, Mueller CM, Shah V, Lin YY, Zhang H, Dresner L, Lempert L, Nowakowski M, Gross R, Schulze R, Zenilman ME. Sophorolipids block lethal effects of septic shock in rats in a cecal ligation and puncture model of experimental sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:188–95. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000196212.56885.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bluth MH, Norowitz KB, Chice S, Shah VN, Nowakowski M, Durkin HG, Smith-Norowitz TA. IgE, CD8(+)CD60+ T cells and IFN-alpha in human immunity to parvovirus B19 in selective IgA deficiency. Hum Immunol. 2005;66:1029–38. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wodicka L, Dong H, Mittmann M, Ho MH, Lockhart DJ. Genome-wide expression monitoring in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:1359–1367. doi: 10.1038/nbt1297-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Kandil E, Lin YY, Levi G, Zenilman ME. Targeted inhibition of gene expression of pancreatitis-associated proteins exacerbates the severity of acute pancreatitis in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:870–81. doi: 10.1080/00365520410006477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beger HG, Rau B, et al. Natural course of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1997;21:130–5. doi: 10.1007/s002689900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ammori BJ. Role of the gut in the course of severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2003;26:122–9. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhl W, Warshaw A, Imrie C, Bassi C, McKay CJ, Lankisch PG, Carter R, Di Magno E, Banks PA, Whitcomb DC, Dervenis C, Ulrich CD, Satake K, Ghaneh P, Hartwig W, Werner J, McEntee G, Neoptolemos JP, Büchler MW International Association of Pancreatology. Guidelines for the Surgical Management of Acute Pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2002;2:565–73. doi: 10.1159/000071269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor SL, Morgan DL, Denson KD, Lane MM, Pennington LR. A comparison of the Ranson, Glasgow, and APACHE II scoring systems to a multiple organ system score in predicting patient outcome in pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2005;189:219. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ji B, Chen XQ, Misek DE, Kuick R, Hanash S, Ernst S, Najarian R, Logsdon CD. Pancreatic gene expression during the initiation of acute pancreatitis: identification of EGR-1 as a key regulator. Physiol Genomics. 2003;14:59–72. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00174.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pezzilli R, Billi P, Beltrandi E, Maldini M, Mancini R, Morselli Labate AM, Miglioli M. Circulating lymphocyte subsets in human acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1995;11:95–100. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199507000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rydzewska G, Rivard N, Morisset J. Dynamics of pancreatic tyrosine kinase and phospholipase D activities in the course of cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis and during regeneration. 1995;10:382–8. doi: 10.1097/00006676-199505000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang P, Frohman MA. The potential for phospholipase D as a new therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:707–16. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.5.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foitzik T, Hotz HG, Hotz B, Wittig F, Buhr HJ. Selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) reduces prostaglandin E2 production and attenuates systemic disease sequelae in experimental pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1159–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paszkowski AS, Rau B, Mayer JM, Moller P, Beger HG. Therapeutic application of caspase 1/interleukin-1beta-converting enzyme inhibitor decreases the death rate in severe acute experimental pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2002;235:68–76. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baumgart K, Paszkowski AS, Mayer JM, Beger HG. Clinical relevance of caspase-1 activated cytokines in acute pancreatitis: high correlation of serum interleukin-18 with pancreatic necrosis and systemic complications. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:1556–62. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar A, Hall MW, Exline M, Hart J, Knatz N, Gatson NT, Wewers MD. Caspase-1 regulates Escherichia coli sepsis and splenic B cell apoptosis independently of interleukin-1beta and interleukin-18. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1003–10. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-546OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Webster KA, Graham RM, Thompson JW, Spiga MG, Frazier DP, Wilson A, Bishopric NH. Redox stress and the contributions of BH3-only proteins to infarction. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1667–76. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green DR. Life, death, BH3 profiles, and the salmon mousse. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:97–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kandil E, Lin YY, Bluth MH, Zhang H, Levi G, Zenilman ME. Dexamethasone mediates protection against acute pancreatitis via upregulation of pancreatitis-associated proteins. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6806–11. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i42.6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomez G, Townsend CM, Jr, Green D, Rajaraman S, Uchida T, Thompson JC. Involvement of cholecystokinin receptors in the adverse effect of glucocorticoids on diet-induced necrotizing pancreatitis. Surgery. 1989;106:230–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bluth MH, Bluth MJ, Johns C, Kahn S, Lin YY, Zenilman ME, Cheung WW. Peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene array profiles in patients with overactive bladder. J Immunol. 2007;178:132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]