Abstract

Live attenuated vaccine vectors based on recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses (rVSVs) expressing foreign antigens are highly effective vaccines in animal models. In this study, we report that an rVSV expressing influenza nucleoprotein (VSV NP) from the first position of the VSV genome induces robust anti-NP CD8 T cells in immunized mice. These CD8 T cells are phenotypically similar to those induced by natural influenza infection and are cytotoxic in vivo. Animals immunized with an rVSV expressing the influenza hemagglutinin (rVSV HA) were protected but still exhibited considerable morbidity after challenge. Animals receiving a cocktail vaccine of rVSV NP and rVSV HA had reduced pulmonary viral loads, less weight loss, and reduced clinical signs of illness after influenza virus challenge, relative to those vaccinated with rVSV HA alone. Influenza NP is a highly conserved antigen, and induction of protective anti-NP responses may be a productive strategy for generating heterologous protection against divergent influenza strains.

Human influenza A and B viruses cause influenza, which kills an estimated 50,000 people per year in the United States. The vaccines currently available for the prevention of seasonal influenza induce antibodies against the influenza hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) present in the vaccine preparation but leave vaccinees susceptible to infection with divergent viruses. During the resolution of natural influenza infection, the humoral immune response is assisted by the action of cytolytic CD8 T cells (CTLs), which facilitate viral clearance via perforin and granzyme-mediated killing of infected respiratory epithelial cells (20). The CTL response is primarily directed against the conserved influenza nucleoprotein (NP) (2, 20) and matrix protein (M1) (11, 12, 20). These antigens are present in inactivated vaccine formulations administered to humans but appear not to induce protective T-cell responses in vaccinees, most likely because of the reduced immunogenicity of the inactivated vaccine. The optimal induction of cross-reactive memory T-cell responses to conserved antigens such as the NP theoretically would enhance the breadth of vaccine-induced protection and increase resistance of the vaccinee to divergent strains, but this strategy has been difficult to implement. To date, many vaccines based on influenza NP have not been protective in animal models (17, 24) or have required multiple boosts, often with heterologous vectors, to achieve protection (8, 16, 26). Despite this, the development of a vaccine inducing cross-reactive T-cell responses remains an important goal, especially with the emergence of highly pathogenic avian influenzas, against which it has been difficult to raise protective levels of antibody in human vaccinees (1, 19, 21, 28). A CD8 T-cell-based vaccine should mimic a successful immune response to natural influenza infection in terms of breadth, durability, and anatomic site(s) at which the T-cell responses are generated. The ideal vaccine would also induce protective antibody responses to influenza HA, thereby providing “bivalent” protection. It has been shown previously that immunization with recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (rVSV) expressing HA from the WSN strain can protect mice from homologous low-dose challenge (23) and that rVSV expressing HA from avian influenza virus (H5) induced cross-neutralizing antibody (Ab) to unmatched strains (27). We tested whether a novel rVSV expressing the HA of the highly pathogenic A/PR/8/34 influenza virus could protect mice from lethal challenge and whether the addition of a novel rVSV NP to the rVSV HA vaccine would decrease morbidity and enhance recovery after challenge. We report here that the “cocktail” vaccine of rVSVs expressing influenza HA and NP protects mice from lethal challenge with influenza virus A/PR/8/34. rVSV NP and rVSV HA induced robust T-cell and neutralizing Ab responses, respectively, and the addition of NP to the vaccine cocktail enhanced the protection provided by rVSV HA alone, with cocktail-immunized mice having lower viral loads, less clinical signs of infection, and reduced weight loss after challenge versus the levels in those immunized with rVSV HA alone. The CD8 T cells induced by immunization with rVSV NP were similar in number, function, and anatomic location to those generated by sublethal natural influenza infection, and they expanded rapidly upon rechallenge in vivo. These results demonstrate that immunization with a live “flu-like” viral vector induces T-cell responses capable of contributing to protection from influenza challenge and may represent a strategy for improving heterologous protection against divergent influenza virus strains in the immunized host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of plasmids and recovery of recombinant viruses.

To obtain plasmids that could be used to recover rVSV expressing influenza genes from the first or fifth position in the VSV genome, influenza gene sequences (influenza virus strain A/PR/8/34) were PCR amplified from plasmids generously provided by Peter Palese (Mt. Sinai School of Medicine). The forward primer introduced either an XhoI site (NP construct) or a SalI site (HA construct) upstream of the coding sequence, and the reverse primer introduced an NheI site. PCR products were digested with XhoI and NheI, purified, and ligated into the pVSVFXN or pVSVXN2 vector that had been digested with the same enzymes (VSV cloning vectors provided by John Rose, Yale University). pVSVFXN and pVSVXN2 allow insertion of the foreign gene in the first and fifth position of the VSV genome, respectively. Plasmids were recovered after transformation of Escherichia coli and purified using a Maxi kit (Qiagen), and the insert sequences were verified (Duke Sequencing Facility). Recombinant viruses were recovered from these plasmids as described previously (18). Briefly, BHK-21 cells were grown to 50% confluence and infected at a multiplicity of infection of 10 with vTF7-3, a vaccinia virus expressing T7 RNA polymerase. One hour after infection, cells were transfected with 10 μg of the plasmid encoding the full-length VSV genome plus the foreign gene of interest, along with 3 μg of pBluescript-N (pBS-N), 5 μg of pBS-P, 1 μg of pBS-L, and 4 μg of pBS-G. While pBS-G is not required for recovery of recombinants, it was included to enhance efficiency. After 48 h, cell supernatants were passaged onto BHK-21 cells through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter, and medium containing virus was collected about 24 h after cytopathic effect was seen. Virus grown from individual plaques was used to prepare stocks that were grown on BHK-21 cells and was stored at −80°C. Priming vectors were constructed using plasmids encoding the VSV G from the Indiana strain. Boosting vectors were constructed using plasmids encoding the VSV G from the New Jersey strain.

Metabolic labeling and SDS-PAGE of cells infected with recombinants.

BHK cells (106) were infected at a multiplicity of infection of 20 with VSV recombinants. After 5 h, the medium was removed and cells were washed twice with methionine-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM). Methionine-free DMEM (1 ml) containing 100 μCi of [35S]methionine was added to each plate for two additional hours. The medium was removed, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), lysed with 500 μl of detergent solution (1% Nonidet P-40, 0.4% deoxycholate, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 62.5 mM EDTA) on ice for 5 min, and collected into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. The protein extracts were centrifuged for 2 min at 16,000 × g to remove the nuclei and stored at −20°C. Protein extracts were fractionated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE; 15% acrylamide), and proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Inoculation of mice.

Eight- to ten-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories and housed for at least 1 week before the experiments were initiated. Mice were housed in microisolator cages in a biosafety level 2-equipped animal facility. Viral stocks were diluted to the appropriate titers in serum-free DMEM. For intramuscular vaccination, mice were injected with the indicated amount of virus(es) in 50 μl total volume. For intranasal vaccination, mice were lightly anesthetized with isoflurane using a vaporizer and were administered the indicated amount of virus in 40 μl total volume. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Duke University approved all animal experiments. After influenza challenge, mice were monitored daily for weight loss and changes in body temperature (Physitemp rodent thermometer; Physitemp Inc., Clifton, NJ).

Tetramer assay.

Splenocytes were obtained by disrupting spleens between the frosted ends of two microscope slides. Red blood cells were removed using red blood cell lysing buffer (Sigma). To obtain lymphocytes from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (lungs), mice were sacrificed using an overdose of isoflurane and an incision made to expose the trachea. The trachea was cannulated using a blunt-ended needle (tied in place with an unwaxed suture) to which a 1-ml syringe was attached. The lung was gently washed with 1 ml sterile PBS, and the liquid (containing cells) was decanted. Cells were spun down, washed, and stained. To obtain peripheral blood lymphocytes, blood was collected into medium containing heparin. Blood was layered onto a Ficoll gradient and spun, after which lymphocytes were collected from the interface. Cells were washed and resuspended in DMEM containing 5% fetal calf serum. Staining was performed on freshly isolated lymphocytes as previously described (14). Briefly, approximately 5 × 106 cells were added to the wells of a 96-well, V-bottom plate and were blocked with unconjugated streptavidin (Molecular Probes) and Fc block (Pharmingen) for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Following a 5-min centrifugation at 500 × g, splenocytes were labeled with a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD62L Ab (Pharmingen), an allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-CD8 Ab (Pharmingen), and tetramer for 30 min at RT. The tetramer was a phycoerythrin-conjugated major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I Db tetramer (NIH Tetramer Facility) containing the NP366-374 peptide (N-ASNENMETM-C). Animals vaccinated with empty rVSV were used to determine background levels of tetramer binding. The background was routinely less than 0.1% and was subtracted from all reported percentages.

Cytotoxicity assay in vivo.

This assay was performed as described previously (5) using the influenza NP peptide NP366-374 (N-ASNENMETM-C; Invitrogen). On day 21 postimmunization, splenocytes were obtained as described above from an uninfected mouse and resuspended in 1 ml of 5% fetal bovine serum-DMEM. The donor (target) cells were split into two populations. NP peptide was added to one population (+peptide) to a final concentration of 10−6 M, and to the other population no peptide was added (−peptide). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 45 min with occasional mixing. Cells were washed and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. One milliliter of 10 μM 5,6-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) was added to +peptide cells (final concentration, 5 μM) to generate a CFSEhi group, and 1 ml of 1 μM CFSE was added to −peptide cells (final concentration, 0.5 μM) to generate a CFSElo group. Cells were vortexed as the CFSE was added and then incubated for 5 min at RT. Cells were then washed three times in PBS and resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 108 cells/ml. Ten million cells (100 μl) were injected intravenously into vaccinated or control (immunized with wild-type rVSV [rVSV wt]) mice. After 4 h, the recipient mice were euthanized and spleens were obtained and prepared as described above. CFSEhi and CFSElo populations were identified by flow cytometry. Percent specific lysis was calculated by using the following formula: percent specific lysis = [1/(ratio for vaccinated mice/ratio for control mice)] × 100, where “ratio” = (percent CFSElo/percent CFSEhi).

Microneutralization assay for anti-influenza Ab.

A microneutralization assay was performed as described in reference 29. Heat-inactivated serum from immunized or control animals was serially diluted and incubated with virus for one hour at RT. Residual infectivity was detected on MDCK cells after a 4-day culture period. The neutralizing titer was defined as the highest dilution of serum that completely neutralized the infectivity of 50 TCID50 (50% tissue culture infective doses) of PR8 influenza virus. Infectivity was defined by the presence of cytopathic effect on day four postinfection.

Determination of viral titers by plaque assay on MDCK cells.

Mice were sacrificed via anesthetic overdose, and lungs were perfused with sterile saline to remove peripheral blood. The lungs were dissected, weighed, and homogenized in sterile buffer (100 μl buffer per 0.1 g organ weight). Titers of the homogenates were determined by standard plaque assay on MDCK cells in the presence of 1 μg/ml tosylamido-2-phenylethylchloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-trypsin (Sigma) and using a solid agar overlay. After 72 h, the overlay was removed and the cell layer was stained with crystal violet to visualize plaques.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical tests were performed using Graph Pad Prism statistical analysis software. Results were considered significant when P of <0.05 was reached.

RESULTS

Expression of influenza virus genes from rVSV.

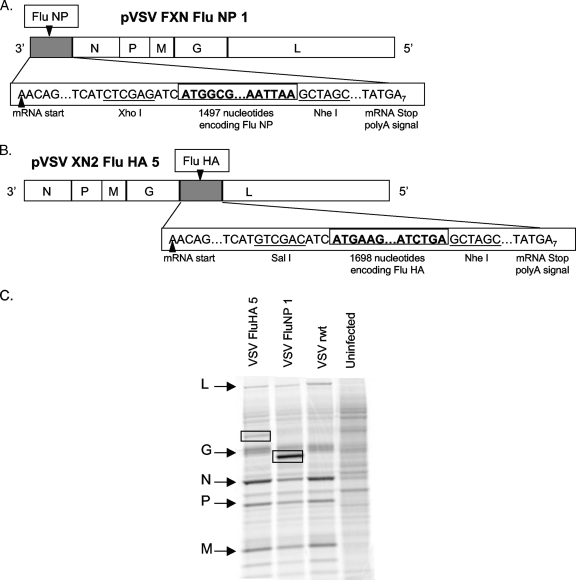

To obtain rVSV expressing influenza HA and NP, we inserted DNA encoding the influenza virus genes (provided by Peter Palese) into plasmid vector pVSVFXN (NP) or pVSVXN2 (HA). This allowed the recovery of rVSV expressing influenza virus genes from the first (pVSVFXN) or fifth (pVSVXN2) transcribed gene in the genome (diagrammed in Fig. 1A and B). An rVSV expressing influenza HA in position 1 was cloned but could not be recovered successfully. Downstream gene transcription in VSV is attenuated ∼30% at each subsequent gene junction during the sequential transcription process (15). Because of this, genes expressed from a more 3′ location in the VSV genome are transcribed in greater quantity, which may lead to better immune responses to the foreign antigen. For the experiments described in this work, we used rVSV NP in which NP was expressed from position 1 of the VSV genome and rVSV HA in which HA was expressed from position 5. Expression of influenza virus genes in cells infected with the rVSVs was verified by metabolic labeling with [35S]methionine, SDS-PAGE, and autoradiography (Fig. 1C). In cells infected with the VSV recombinants, we detected the indicated VSV proteins as well as new protein bands with the mobility (size) expected for the influenza virus genes.

FIG. 1.

rVSV genome and protein expression. Panels A and B are diagrams showing the insertion of influenza virus genes at positions 1 and 5, respectively. The gene order is shown in the 3′ to 5′ direction of transcription on the negative-strand RNA genome. The influenza virus gene insertion sites and flanking nucleotides, including the transcription and translation start and stop sites, are indicated. Restriction enzyme sites used for cloning the influenza virus genes at the DNA stage are also indicated. All sequences are shown in the positive (antigenome) sense for clarity. Panel C shows SDS-PAGE (10% acrylamide) of lysates of BHK cells infected with the indicated recombinant viruses and labeled with [35S]methionine. The gel image was collected on a phosphorimager. Positions of VSV proteins are indicated by arrows on the left side of the gel image. Positions of influenza virus proteins are indicated by boxes on the gel image.

Mice immunized with a single dose of rVSV HA are partially protected from lethal influenza challenge.

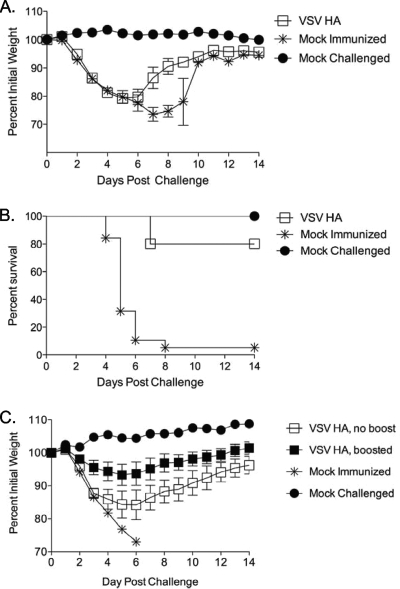

It has been demonstrated previously that mice immunized with an rVSV expressing the HA from the mildly pathogenic WSN strain of influenza virus are protected from challenge with that virus (23). Our first goal was to determine whether mice immunized with rVSV expressing the HA of the highly pathogenic PR8 strain could survive a lethal challenge with PR8 influenza virus. To test this, we immunized mice with 5 × 106 PFU of VSV HA intranasally. Eight weeks after immunization with rVSV HA, all vaccinees were challenged with a lethal dose (100 MLD50 [50% minimal lethal doses]) of influenza virus A/PR/8/34. Vaccinees (n = 5) exhibited significant pathology after challenge, losing an average of 20% preinfection body weight by day five postchallenge (Fig. 2A). One rVSV HA-vaccinated mouse died on day seven after challenge (Fig. 2B), but all other vaccinees recovered their preinfection weight by two weeks after challenge. All mock immunized control animals (n = 19) lost weight rapidly, and all but one animal was dead by day 8 postchallenge. The experiment was repeated a total of three times with consistent results. Protection from challenge correlated with the development of a neutralizing Ab titer of at least 1:20 against PR8 influenza virus in vaccinated animals, as measured by microneutralization assay performed using sera collected at the time of challenge (8 weeks postvaccination). The neutralizing titer was defined as the highest dilution of serum that completely neutralized the infectivity of 50 TCID50 of PR8 influenza virus. Infectivity was defined by the presence of cytopathic effect on day four postinfection.

FIG. 2.

Immunization with rVSV influenza HA partially protects vaccinees from lethal influenza challenge. Eight- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally with 5 × 106 PFU rVSV HA. Graphs show average percent prechallenge body weight (panel A) and survival proportions (panel B) for animals vaccinated with rVSV HA (n = 5) or mock immunized (n = 19) and challenged with 100 MLD50 PR8 influenza virus eight weeks after immunization. Data shown are from a single experiment, which has been repeated a total of three times with consistent results. In panel C, mice were primed intranasally with 2.5 × 106 PFU VSV (Indiana strain) HA and boosted with either 1 × 106 PFU VSV (New Jersey strain) HA (filled squares) or sham inoculum (open squares) four weeks after the primary immunization. Five weeks after the boost, all mice were challenged with 100 MLD50 PR8 influenza virus. Panel C shows weight loss after challenge for each group.

Mice boosted with glycoprotein exchange vectors are better protected from lethal influenza virus challenge.

Mice immunized with a single dose of rVSV HA were not completely protected from lethal challenge and lost a substantial amount of weight after infection with influenza virus (Fig. 2A and B). We predicted that boosting the animals prior to challenge might reduce pathology (weight loss) after challenge and enhance the speed of recovery. To test this, we made rVSV glycoprotein exchange vectors expressing the New Jersey serotype VSV G and the PR8 influenza HA. This boosting strategy has been shown to boost Ab and T-cell responses in the context of human immunodeficiency virus immunization (25). Mice (n = 15) were immunized intranasally with 2.5 × 106 PFU of VSV HA (Indiana strain). After four weeks, all mice received a single booster immunization of 1 × 106 PFU VSV HA (New Jersey strain). Five weeks after the boost, all animals were challenged with 100 MLD50 PR8 influenza virus. All boosted mice survived the challenge, and as shown in Fig. 2C, mice primed and boosted with rVSV HA lost significantly less weight after the challenge than did mice receiving a single immunization, although even primed and boosted mice still lost weight. Protection induced by rVSV HA is likely mediated primarily by anti-influenza humoral responses. We hypothesized that the addition of an antigen inducing cellular responses to the vaccine cocktail might eliminate the need for boosting and further reduce pathology after challenge. To test this, we generated an rVSV expressing the influenza NP and tested it in combination with the rVSV HA.

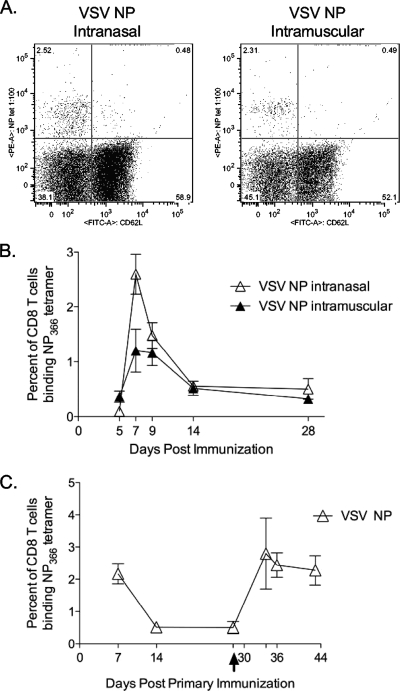

rVSV NP induces primary T-cell responses in the peripheral blood of immunized mice.

Prior to beginning the challenge experiments, we verified that rVSV NP could induce immune responses to the influenza NP. We immunized mice with rVSV NP and monitored the immune response to the immunodominant NP366-374 epitope using an MHC class I tetramer recognizing CD8 T cells specific for NP366-374. Anti-NP-specific CD8 T cells were detected in the peripheral blood of immunized animals (5 to 15 mice per group analyzed at each time point) after primary intranasal or intramuscular immunization (Fig. 3A) with VSV NP. Tetramer-positive cells were detectable in the peripheral blood by five days postimmunization and peaked in number by seven days postimmunization (Fig. 3B). Anti-NP-specific CD8 T cells were still detectable at two weeks postinfection and had returned to resting levels by four weeks postimmunization. The number of NP-specific CD8 T cells generally did not differ by route of immunization. On day 7 postimmunization, mice immunized intranasally had a significantly greater percentage of NP-specific T cells than did mice immunized intramuscularly (2.60% ± 0.36% versus 1.20% ± 0.39%, P = 0.037; Mann-Whitney test), but this difference was not maintained at later time points. After priming intranasally with the original (Indiana) serotype vectors and boosting intranasally with the New Jersey serotype boosting vectors, the anti-NP CD8 T-cell response expanded significantly (Fig. 3C). For mice vaccinated with rVSV NP alone, anti-NP CD8 T cells were maintained at a significantly higher resting level 14 days after the boost (3.06% ± 0.87%) versus 14 days after the primary immunization (0.56% ± 0.07%), indicating that the boost was effective (P = 0.028; Student t test).

FIG. 3.

Immunization with rVSV induces influenza-specific CD8 T-cell responses in the peripheral blood. Eight- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally or intramuscularly (n of 5 to 15 mice per group per time point) with 2.5 × 106 PFU of rVSV NP. Panel A shows representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots of tetramer staining of peripheral blood lymphocytes isolated 7 days after intranasal (left panel) or intramuscular (right panel) immunization. Panel B shows a time course of anti-NP CD8 T-cell responses in the peripheral blood of vaccinated animals. Points on the graph represent average percent tetramer-positive cells ± standard errors of the means for each immunization group. On day 7, mice immunized intranasally had significantly more NP-specific cells than did mice immunized intramuscularly (P = 0.037; Mann-Whitney test). The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant at any other time point tested. In panel C, 8- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally with 2.5 ×106 PFU of the indicated Indiana serotype rVSV (n of 10 per group). Four weeks after primary immunization, all vaccinated animals were boosted with 2.5 × 106 PFU of the corresponding rVSV (New Jersey serotype), as indicated by the arrow on the x axis. The graph represents the average percent peripheral blood CD8 T cells binding the NP366 tetramer ± standard errors of the means.

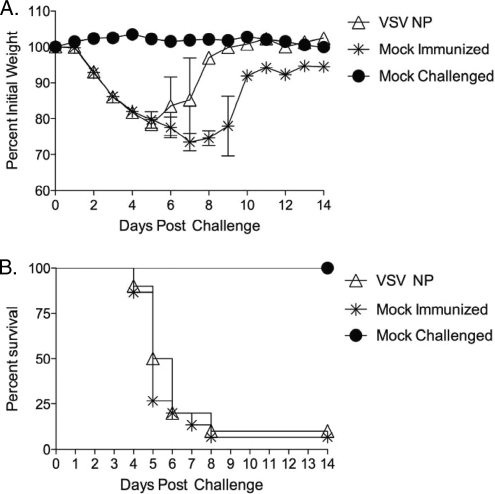

Mice immunized with rVSV NP alone are not protected from lethal influenza challenge.

To determine whether immunization with rVSV expressing influenza NP was sufficient to protect against influenza challenge, we immunized mice (n of 10 per group) intranasally with 2.5 × 106 PFU rVSV NP (Indiana strain). Four weeks after the primary immunization, all mice were boosted with 1 × 106 PFU rVSV NP (New Jersey strain). Five weeks after the booster immunization, all mice were challenged with 100 MLD50 PR8 influenza virus. All vaccinated (n = 10) mice, and all but one of the control mock-immunized (n = 15) mice, lost weight rapidly (Fig. 4A) and had succumbed to infection by seven days after the challenge (Fig. 4B). There was no statistically significant difference in weight loss or rate of survival between rVSV-vaccinated and sham-immunized control mice. These data show that despite the fact that rVSV vectors induced robust cellular responses to influenza NP, these responses were not sufficient to protect against lethal influenza infection in the absence of a protective Ab response.

FIG. 4.

Immunization with rVSV NP alone does not protect animals from lethal challenge. Female 8- to 10-week-old C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally with 2.5 × 106 PFU of rVSV NP (n = 10) or mock immunized with saline (n = 15). Five weeks after immunization, all vaccinated and mock-immunized control animals were challenged intranasally with 100 MLD50 PR8 influenza virus. Graphs show average percent initial weight ± standard errors of the means (panel A) and survival (panel B) for each group. There was no statistically significant difference between weight loss and rate of survival when the vaccinated animals were compared to mock-immunized controls.

CD8 T cells generated by rVSV immunization augment Ab-mediated protection from lethal challenge.

Despite the fact that rVSV NP did not protect on its own, it remained possible that the robust T-cell responses generated by rVSV NP immunization would enhance protection induced by rVSV HA immunization. To test this, we immunized mice with a cocktail vaccine of rVSV HA and rVSV NP (2.5 × 106 PFU of each virus, delivered intranasally; n of 10 to 15 mice per group). Mice vaccinated with rVSV HA received 2.5 × 106 PFU of rVSV HA and 2.5 × 106 PFU of rVSV wt (empty vector). Five weeks after the primary immunization, mice were challenged with 100 LD50 PR8 influenza virus. All mice vaccinated with rVSV HA or with rVSV HA and rVSV NP survived, and mice immunized with the cocktail vaccine of rVSV HA and rVSV NP (n = 15) had significantly enhanced recovery, beginning on day five after infection, versus those vaccinated with rVSV HA (n = 10) alone (Fig. 5A), with the difference in weight loss between the two groups being statistically significant from days 7 to 11 after challenge. This demonstrated that the addition of rVSV NP to the vaccine cocktail could enhance recovery after challenge and suggested that the expansion of vaccine-induced, NP-specific CD8 T cells might be mediating that effect. To determine the mechanism by which immune responses generated by VSV NP contributed to protection, we immunized a second cohort of mice (n of 20 per group) with either VSV HA alone, VSV HA and NP, or with VSV wt (empty vector) and measured the temperature change (Fig. 5B), the viral loads in the lung (Fig. 5C), and the cellular and humoral responses (Fig. 5D and E) over a time course after lethal challenge with influenza virus. In combination with measuring weight loss, changes in body temperature provide a sensitive indication of the extent of pathology after influenza virus challenge (33). The body temperature of sham-immunized mice typically decreases by 1 to 2°C between the first and second day after lethal influenza challenge (Fig. 5B). A decrease in the magnitude of temperature loss indicates better control of infection and an enhanced likelihood of survival. The body temperatures of mice immunized with the rVSV cocktail vaccine decreased an average of 0.18°C ± 0.12°C, which was significantly less than the decrease in mice immunized with rVSV HA (0.7°C ± 0.13°C, P = 0.0046; Student t test). When we measured infectious virus titers in the lungs of vaccinees (four to five mice per group per time point) from two to nine days postchallenge, we found high titers of virus in the rVSV empty mock-immunized mice at all time points (Fig. 5C). None of the mice immunized with the cocktail vaccine had detectable virus in the lung at any time point, while three out of four mice receiving rVSV HA alone and measured at 48 h had detectable virus. The difference in viral loads between mice immunized with rVSV HA alone versus those immunized with the cocktail vaccine was not due to differences in the amount of neutralizing Ab present in the vaccinees, since neutralizing titers did not differ between the two groups either before or at any time point after challenge (Fig. 5D). In contrast, from the third day after challenge onward, all mice immunized with the cocktail vaccine had detectable levels of NP-specific CD8 T cells in their blood, whereas mice immunized with rVSV HA alone did not have detectable levels of NP-specific cells until 6 days after challenge (Fig. 5E) (n of 3 to 4 mice per group per time point). On days in which both groups had detectable levels of anti-NP-specific T cells, mice immunized with the cocktail had more from day 6 (0.77% ± 0.28% versus 0.06% ± 0.03%) through day 7 (1.68% ± 0.67% versus 0.84% ± 0.33%) postchallenge than did mice immunized with rVSV HA alone. The expansion of NP-specific CD8 T cells is consistent with the control of pulmonary viral loads in the cocktail-immunized mice, and it suggests that NP-specific T cells induced by rVSV NP immunization are able to contribute to the elimination of infected cells in vivo.

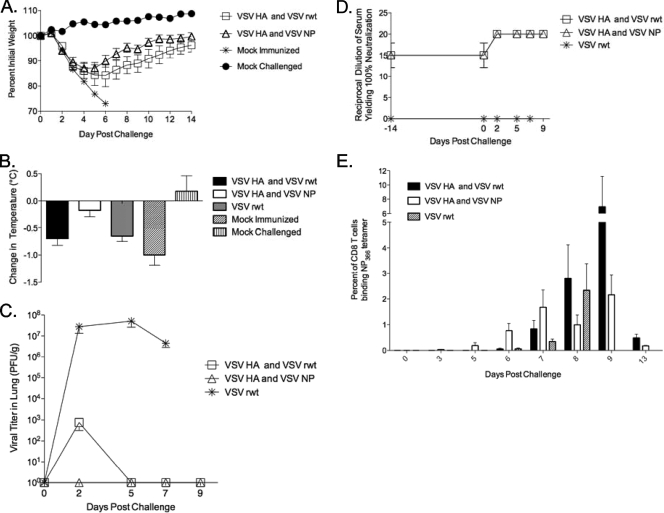

FIG. 5.

Addition of rVSV NP to the rVSV HA vaccine cocktail enhances recovery after challenge in 8- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice immunized with 2.5 × 106 PFU of the indicated rVSV (n of 10 to 15 mice per group) or 5 × 106 PFU (the rVSV wt-only group). Five weeks later, mice were challenged intranasally with 100 MLD50 of PR8 influenza virus. The graph (panel A) represents daily average percent initial weight ± standard errors of the means for each group after challenge. For panels B to E, we immunized a second cohort of mice (n of 20 per group), as for panel A, and measured the temperature change (panel B), the viral loads in the lung (panel C), and the humoral and cellular responses (panels D and E) over a time course after challenge. Bars on the graph (panel B) represent the average decrease in body temperature ± standard errors of the means between days 1 and 2 after challenge for each group. Panel C shows the average titers of infectious virus in the lungs of vaccinated and control mice in PFU/g. By day 8, all rVSV empty vector and PBS mock-immunized control mice were all dead. Panel D shows serum-neutralizing titers measured by microneutralization assay using pooled serum samples from at least five vaccinated or control animals for each time point. Panel E shows the average levels of NP-specific T cells detected via NP tetramer in the peripheral blood (n of 3 to 4 mice per group per time point) of vaccinated and mock-immunized mice.

Anti-NP-specific T cells generated by rVSV immunization are similar in number and function to those generated by natural influenza infection.

These data demonstrate that the anti-NP-specific T cells make a partial contribution to protection but cannot protect on their own. CD8 T cells generated by natural influenza infection can mediate protection from challenge in murine challenge models. Specifically, mice immunized with the relatively less pathogenic HKx31 (H3N2) influenza virus are protected from subsequent lethal challenge with PR8 (H1N1) influenza virus (6, 9, 34). Cytotoxic CD8 T cells raised by the HKx31 immunization expand upon the PR8 challenge, killing infected respiratory epithelial cells and reducing viral loads in infected mice (31). To determine why the CD8 T cells generated by rVSV immunization did not function in the same way, we undertook a series of mechanistic experiments. One possibility was that the CD8 T cells induced by rVSV immunization were different in number or function from those induced by sublethal influenza infection. rVSV immunization may have failed to protect mice from challenge because it did not generate enough CD8 T cells to mediate protection in this manner, or because the cells generated by rVSV immunization were not able to kill infected cells in vivo. In order to test this, we immunized mice with 2.5 × 106 PFU rVSV NP and compared the magnitude of their T-cell responses to that of mice immunized with a sublethal dose of live influenza virus (2 × 103 PFU live PR8 influenza virus, delivered intranasally) that produced no clinical symptoms but was sufficient to confer immunity upon rechallenge with a lethal dose (2 × 106 PFU live PR8 influenza virus, delivered intranasally). The peak number of NP-specific CD8 T cells generated by rVSV immunization was not significantly different than the peak number generated by sublethal influenza infection (Fig. 6A), indicating that rVSV NP immunization is as immunogenic as natural infection for the induction of acute anti-NP CD8 T-cell responses.

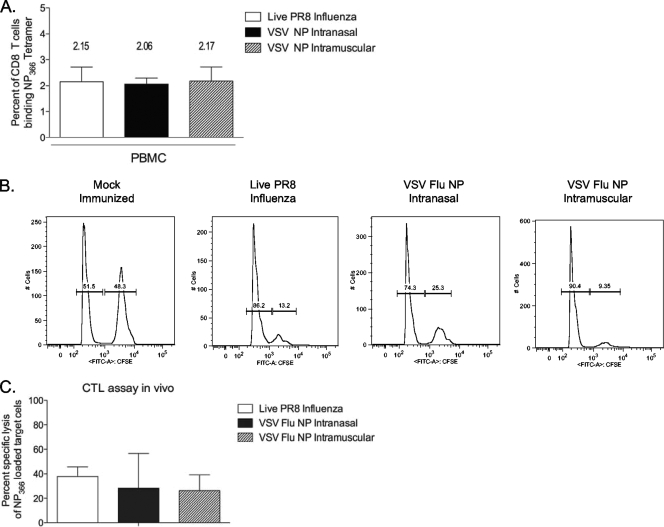

FIG. 6.

Immunization with rVSV NP induces peak anti-NP CD8 T-cell responses equivalent to those induced by sublethal influenza infection. Eight- to 10-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were immunized intranasally (n = 18) or intramuscularly (n = 10) with 2.5 × 106 PFU rVSV NP or intranasally with a sublethal dose (2.0 × 103 PFU) of live PR8 influenza virus (n = 8). Seven (rVSV) or nine (influenza virus) days postimmunization, lymphocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood and stained for NP-specific CD8 T cells. The graph (panel A) represents the average percent ± standard errors of the means of CD8+/CD62Llo cells binding the NP tetramer for each group. Four mock-immunized control animals were analyzed, and average tetramer binding (0.015%) has been subtracted from the numbers reported for vaccinees. There were no significant differences in the numbers of NP-specific T cells generated by the three different immunizations. Panels B and C show a cytotoxicity assay in vivo. Mice (n of 3 to 5 per group) were immunized as in panel A with the indicated viruses. Three weeks after immunization, all mice were injected intravenously with 1 × 107 differentially labeled autologous splenocytes. Four hours after transfer, all recipient animals were sacrificed and splenocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative histogram plots for mock- and VSV NP-immunized animals are shown in panel B, and the average percent specific lysis ± standard errors of the means per group are shown in panel C. There were no significant differences in the percent specific lysis between the groups.

Anti-NP CD8 T cells generated by rVSV immunization have cytotoxic activity in vivo.

To determine whether NP-specific T cells generated by rVSV immunization were able to kill NP-labeled target cells, we performed a CTL assay in vivo. As shown in Fig. 6B and C, cytotoxic activity in mice immunized intranasally (n = 3) or intramuscularly (n = 3) with 2.5 × 106 PFU rVSV NP was not significantly different than the cytotoxic activity detected in mice immunized with the sublethal dose of live influenza virus (n = 5) when in vivo CTL activity against the immunodominant NP366-374 epitope was measured 21 days after immunization. These data demonstrate that CD8 T cells primed by rVSV NP immunization are able to kill target cells presenting influenza NP peptide and suggest that these cells could limit viral replication in vivo in the same way that CD8 T cells generated by naturally acquired influenza infection do.

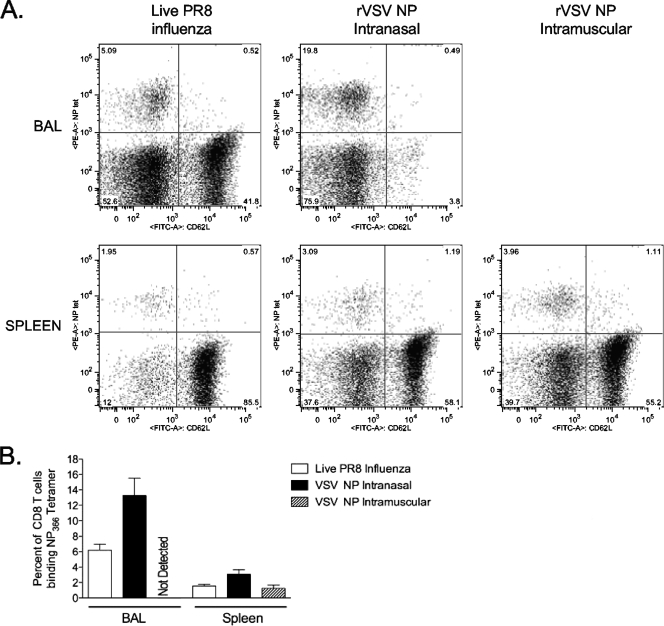

Intranasal immunization with live influenza virus or rVSV NP induces anti-NP T-cell responses in the lung.

It has been shown that the induction of immune responses in the lung is required for protection from influenza challenge (4). To test whether rVSV induced T-cell responses in the same anatomic compartments as sublethal influenza infection, we immunized mice with 2.5 × 106 PFU rVSV NP or a sublethal dose of PR8 influenza virus and measured anti-NP CD8 T-cell responses in the lung (bronchoalveolar lavage fluid) and spleen. We show in Fig. 7 that natural infection with influenza virus and intranasal immunization with rVSV NP, but not intramuscular immunization with rVSV NP, induced CD8 T-cell responses in the lung. The response induced by intranasal immunization with rVSV NP was significantly greater than that induced by live influenza virus (13.3% ± 2.2% versus 6.2% ± 0.7%, P = 0.03; Student t test) (Fig. 7B). No NP-specific CD8 T cells were detected in the lungs of mice immunized intramuscularly with rVSV NP (n of 5 mice tested). Intranasal immunization with rVSV NP and with live influenza virus induced robust anti-NP responses in the spleen (3.1% ± 0.6% and 1.6% ± 0.2%, respectively), which were not significantly different (P = 0.07; Student t test). Responses induced by intramuscular immunization with rVSV NP (1.2% ± 0.4%) were lower than those induced by intranasal immunization with rVSV NP (3.1% ± 0.6%), but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06) (Fig. 7B). The absolute numbers of CD8 T cells isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and spleen did not differ between VSV- and influenza-infected mice, suggesting that differences in protection cannot be attributed to a reduced number of antigen-specific cells in VSV-immunized mice.

FIG. 7.

Intranasal rVSV NP immunization induces pulmonary and splenic CD8 T-cell responses equivalent to those induced by live influenza virus. Four to six mice per group were immunized intramuscularly or intranasally with 2.5 × 106 PFU of rVSV NP or intranasally with 2 × 103 PFU live PR8 influenza virus as indicated. Seven (rVSV) or nine (influenza virus) days after immunization, lymphocytes were isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and spleen, and NP-specific T cells were detected as described for Fig. 3A. Representative fluorescence-activated cell sorter plots for each organ/group are shown. The graph represents the average percent ± standard errors of the means of CD8+/CD62Llo cells binding the NP tetramer for each group. Three mock-immunized control mice were analyzed, and average tetramer binding (0.00% BAL and 0.015% spleen) has been subtracted from the numbers reported here.

DISCUSSION

We undertook this study to determine whether immunization with rVSV expressing the conserved influenza NP could induce cellular responses capable of contributing to protection from lethal influenza virus challenge. We found that vaccination with rVSV NP did not protect on its own but that the addition of rVSV NP to a cocktail vaccine including rVSV HA enhanced protection and reduced morbidity and recovery time after challenge. rVSV NP induced robust CD8 T-cell responses in vaccinees that were rapidly recalled after challenge. One question arising from these results is why the anti-NP responses raised by rVSV NP immunization were not sufficient to protect from lethal challenge and why they did not ameliorate postchallenge pathology to a greater extent. Although a protective influenza vaccine based solely on cellular responses has never been developed for human use, animal studies have demonstrated that protection in the absence of humoral responses is possible. Specifically, mice which lack the ability to produce immunoglobulin (Ig) via deletion of the heavy chain locus (IgH−/−) can survive influenza challenge, albeit with a 50 to 100× reduced rate of survival relative to that of intact mice (3, 10, 13, 22, 32). B-cell-deficient animals primed with a sublethal dose of influenza virus develop cellular responses that enhance immunity upon rechallenge (versus naive IgH−/− mice) (13), and the depletion of cellular responses, via depletion of CD8 T cells, abrogates protection (30). Similarly, infection of mice (6, 9, 34) or humans (7) with one influenza virus strain can confer protection against heterologous strains. Since anti-HA and -NA Abs induced by the first infection are not active against the second infection, heterologous protection in this model is most likely mediated at least in part by cellular responses to conserved antigens such as NP. In view of these data, it is important to determine why rVSV vaccine-induced cellular responses to conserved antigens did not protect in the same way that cross-reactive responses to natural infection do. It is possible that the CD8 T cells generated by rVSV vaccination were fundamentally different in terms of function than those generated by cross-protective natural infection. However, when we compared the number of anti-NP-specific CD8 T cells generated, the cytotoxic capacity in vivo, and the anatomic locations of the T cells we did not find significant differences between vaccine-induced cells and those raised in response to sublethal infection with influenza virus. In view of this, it is possible that the cellular responses to conserved antigens raised by rVSV NP immunization are functional but that they may not act quickly enough to halt viral infection in the absence of protective Ab. Consistent with this idea, the NA inhibitor Tamiflu (oseltamivir), which is used to blunt the pathology of influenza infection, must be administered in the first 48 h after infection in order to be effective. This suggests that once influenza infection is established, “augmenting” therapies that reduce viral loads (e.g., anti-NP cytotoxic responses and NA inhibitors) must act within a narrow window. If augmenting therapies do not act within this window, then the course of infection is set, and such therapies are no longer effective. Anti-NP CD8 T cells raised by rVSV NP immunization were detectable in the peripheral blood by three days after rechallenge with influenza virus. In animals with preexisting neutralizing Ab to HA (rVSV HA immunized), the NP responses correlated with lower viral loads and enhanced recovery. In mice immunized only with rVSV NP, however, it is likely that expansion of these cells on day three was too late to effect protection and that the virus overwhelmed the ability of cellular responses to control it. Another possibility is that cellular responses induced by rVSV NP were of insufficient breadth to confer full protection from challenge. Natural infection would be expected to induce responses to NP but also to other conserved antigens such as PB1, M1, and NS1. Our data do not exclude the possibility that the breadth of responses to NP are inadequate for protection, and adding additional conserved antigens (e.g., PB1 and M2) to the vaccine cocktail could enhance protection and might allow us to protect animals without the use of vectors encoding HA. The addition of vector-encoded immunomodulatory factors might also enhance protection via cellular responses, by decreasing the amount of time necessary for secondary expansion of vaccine-induced cytotoxic T cells. Finally, it is possible that natural infection with influenza virus triggers innate immune responses which lead to the development of better protection against rechallenge than vaccination does. Further experiments to elucidate differences in the immune response to rVSV vaccination versus natural infection are necessary, and they will further not only vaccine design but our understanding of the fine differences between the host response to viral antigens in their natural, versus “almost-natural,” context. In the interim, as we demonstrated here, the addition of conserved influenza antigens to a vaccine which protects primarily via induction of immune responses to HA can improve protection and ameliorate morbidity. This is an important strategy for broadening the efficacy of influenza vaccines and may be a way to achieve protection against highly pathogenic and newly emerging viruses.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant number AI51445. The work was conducted in the Global Health Research Building at Duke University, which receives support from grant number UC6 AI058607.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 25 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atmar, R. L., W. A. Keitel, S. M. Patel, J. M. Katz, D. She, H. El Sahly, J. Pompey, T. R. Cate, and R. B. Couch. 2006. Safety and immunogenicity of nonadjuvanted and MF59-adjuvanted influenza A/H9N2 vaccine preparations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 431135-1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brett, S. J., J. Blau, C. M. Hughes-Jenkins, J. Rhodes, F. Y. Liew, and J. P. Tite. 1991. Human T cell recognition of influenza A nucleoprotein. Specificity and genetic restriction of immunodominant T helper cell epitopes. J. Immunol. 147984-991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, D. M., A. M. Dilzer, D. L. Meents, and S. L. Swain. 2006. CD4 T cell-mediated protection from lethal influenza: perforin and antibody-mediated mechanisms give a one-two punch. J. Immunol. 1772888-2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerwenka, A., T. M. Morgan, and R. W. Dutton. 1999. Naive, effector, and memory CD8 T cells in protection against pulmonary influenza virus infection: homing properties rather than initial frequencies are crucial. J. Immunol. 1635535-5543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coles, R. M., S. N. Mueller, W. R. Heath, F. R. Carbone, and A. G. Brooks. 2002. Progression of armed CTL from draining lymph node to spleen shortly after localized infection with herpes simplex virus 1. J. Immunol. 168834-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Effros, R. B., P. C. Doherty, W. Gerhard, and J. Bennink. 1977. Generation of both cross-reactive and virus-specific T-cell populations after immunization with serologically distinct influenza A viruses. J. Exp. Med. 145557-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein, S. L. 2006. Prior H1N1 influenza infection and susceptibility of Cleveland Family Study participants during the H2N2 pandemic of 1957: an experiment of nature. J. Infect. Dis. 19349-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Epstein, S. L., W. P. Kong, J. A. Misplon, C. Y. Lo, T. M. Tumpey, L. Xu, and G. J. Nabel. 2005. Protection against multiple influenza A subtypes by vaccination with highly conserved nucleoprotein. Vaccine 235404-5410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flynn, K. J., G. T. Belz, J. D. Altman, R. Ahmed, D. L. Woodland, and P. C. Doherty. 1998. Virus-specific CD8+ T cells in primary and secondary influenza pneumonia. Immunity 8683-691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerhard, W., K. Mozdzanowska, M. Furchner, G. Washko, and K. Maiese. 1997. Role of the B-cell response in recovery of mice from primary influenza virus infection. Immunol. Rev. 15995-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gotch, F., A. McMichael, and J. Rothbard. 1988. Recognition of influenza A matrix protein by HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Use of analogues to orientate the matrix peptide in the HLA-A2 binding site. J. Exp. Med. 1682045-2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gotch, F., J. Rothbard, K. Howland, A. Townsend, and A. McMichael. 1987. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes recognize a fragment of influenza virus matrix protein in association with HLA-A2. Nature 326881-882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham, M. B., and T. J. Braciale. 1997. Resistance to and recovery from lethal influenza virus infection in B lymphocyte-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 1862063-2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haglund, K., I. Leiner, K. Kerksiek, L. Buonocore, E. Pamer, and J. K. Rose. 2002. High-level primary CD8+ T-cell response to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag and Env generated by vaccination with recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses. J. Virol. 762730-2738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iverson, L. E., and J. K. Rose. 1981. Localized attenuation and discontinuous synthesis during vesicular stomatitis virus transcription. Cell 23477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laddy, D. J., J. Yan, M. Kutzler, D. Kobasa, G. P. Kobinger, A. S. Khan, J. Greenhouse, N. Y. Sardesai, R. Draghia-Akli, and D. B. Weiner. 2008. Heterosubtypic protection against pathogenic human and avian influenza viruses via in vivo electroporation of synthetic consensus DNA antigens. PLoS ONE 3e2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawson, C. M., J. R. Bennink, N. P. Restifo, J. W. Yewdell, and B. R. Murphy. 1994. Primary pulmonary cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced by immunization with a vaccinia virus recombinant expressing influenza A virus nucleoprotein peptide do not protect mice against challenge. J. Virol. 683505-3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawson, N. D., E. A. Stillman, M. A. Whitt, and J. K. Rose. 1995. Recombinant vesicular stomatitis viruses from DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 924477-4481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin, J., J. Zhang, X. Dong, H. Fang, J. Chen, N. Su, Q. Gao, Z. Zhang, Y. Liu, Z. Wang, M. Yang, R. Sun, C. Li, S. Lin, M. Ji, Y. Liu, X. Wang, J. Wood, Z. Feng, Y. Wang, and W. Yin. 2006. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated adjuvanted whole-virion influenza A (H5N1) vaccine: a phase I randomised controlled trial. Lancet 368991-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMichael, A. J., C. A. Michie, F. M. Gotch, G. L. Smith, and B. Moss. 1986. Recognition of influenza A virus nucleoprotein by human cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Gen. Virol. 67719-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicholson, K. G., A. E. Colegate, A. Podda, I. Stephenson, J. Wood, E. Ypma, and M. C. Zambon. 2001. Safety and antigenicity of non-adjuvanted and MF59-adjuvanted influenza A/Duck/Singapore/97 (H5N3) vaccine: a randomised trial of two potential vaccines against H5N1 influenza. Lancet 3571937-1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riberdy, J. M., J. P. Christensen, K. Branum, and P. C. Doherty. 2000. Diminished primary and secondary influenza virus-specific CD8+ T-cell responses in CD4-depleted Ig−/− mice. J. Virol. 749762-9765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts, A., E. Kretzschmar, A. S. Perkins, J. Forman, R. Price, L. Buonocore, Y. Kawaoka, and J. K. Rose. 1998. Vaccination with a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus expressing an influenza virus hemagglutinin provides complete protection from influenza virus challenge. J. Virol. 724704-4711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson, H. L., C. A. Boyle, D. M. Feltquate, M. J. Morin, J. C. Santoro, and R. G. Webster. 1997. DNA immunization for influenza virus: studies using hemagglutinin- and nucleoprotein-expressing DNAs. J. Infect. Dis. 176S50-S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose, N. F., P. A. Marx, A. Luckay, D. F. Nixon, W. J. Moretto, S. M. Donahoe, D. Montefiori, A. Roberts, L. Buonocore, and J. K. Rose. 2001. An effective AIDS vaccine based on live attenuated vesicular stomatitis virus recombinants. Cell 106539-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saha, S., S. Yoshida, K. Ohba, K. Matsui, T. Matsuda, F. Takeshita, K. Umeda, Y. Tamura, K. Okuda, D. Klinman, K. Q. Xin, and K. Okuda. 2006. A fused gene of nucleoprotein (NP) and herpes simplex virus genes (VP22) induces highly protective immunity against different subtypes of influenza virus. Virology 35448-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwartz, J. A., L. Buonocore, A. Roberts, A. Suguitan, Jr., D. Kobasa, G. Kobinger, H. Feldmann, K. Subbarao, and J. K. Rose. 2007. Vesicular stomatitis virus vectors expressing avian influenza H5 HA induce cross-neutralizing antibodies and long-term protection. Virology 366166-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stephenson, I., K. G. Nicholson, A. Colegate, A. Podda, J. Wood, E. Ypma, and M. Zambon. 2003. Boosting immunity to influenza H5N1 with MF59-adjuvanted H5N3 A/Duck/Singapore/97 vaccine in a primed human population. Vaccine 211687-1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suguitan, A. L., Jr., J. McAuliffe, K. L. Mills, H. Jin, G. Duke, B. Lu, C. J. Luke, B. Murphy, D. E. Swayne, G. Kemble, and K. Subbarao. 2006. Live, attenuated influenza A H5N1 candidate vaccines provide broad cross-protection in mice and ferrets. PLoS Med. 3e360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Topham, D. J., and P. C. Doherty. 1998. Clearance of an influenza A virus by CD4+ T cells is inefficient in the absence of B cells. J. Virol. 72882-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Topham, D. J., R. A. Tripp, and P. C. Doherty. 1997. CD8+ T cells clear influenza virus by perforin or Fas-dependent processes. J. Immunol. 1595197-5200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Topham, D. J., R. A. Tripp, A. M. Hamilton-Easton, S. R. Sarawar, and P. C. Doherty. 1996. Quantitative analysis of the influenza virus-specific CD4+ T cell memory in the absence of B cells and Ig. J. Immunol. 1572947-2952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toth, L. A., J. E. Rehg, and R. G. Webster. 1995. Strain differences in sleep and other pathophysiological sequelae of influenza virus infection in naive and immunized mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 5889-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zweerink, H. J., S. A. Courtneidge, J. J. Skehel, M. J. Crumpton, and B. A. Askonas. 1977. Cytotoxic T cells kill influenza virus infected cells but do not distinguish between serologically distinct type A viruses. Nature 267354-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]