Abstract

The reevaluation of the genus Trichosporon has led to the replacement of the old taxon Trichosporon beigelii by six new species. Sequencing of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) intergenic spacer 1 (IGS1) is currently mandatory for accurate Trichosporon identification, but it is not usually performed in routine laboratories. Here we describe Trichosporon species distribution and prevalence of Trichosporon asahii genotypes based on rDNA IGS1 sequencing as well as antifungal susceptibility profiles of 22 isolates recovered from blood cultures. The clinical isolates were identified as follows: 15 T. asahii isolates, five Trichosporon asteroides isolates, one Trichosporon coremiiforme isolate, and one Trichosporon dermatis isolate. We found a great diversity of different species causing trichosporonemia, including a high frequency of isolation of T. asteroides from blood cultures that is lower than that of T. asahii only. Regarding T. asahii genotyping, we found that the majority of our isolates belonged to genotype 1 (86.7%). We report the first T. asahii isolate belonging to genotype 4 in South America. Almost 50% of all T. asahii isolates exhibited amphotericin B MICs of ≥2 μg/ml. Caspofungin MICs obtained for all the Trichosporon sp. isolates tested were consistently high (MICs ≥ 2 μg/ml). Most isolates (87%) had high MICs for 5-flucytosine, but all of them were susceptible to triazoles, markedly to voriconazole (all MICs ≤ 0.06 μg/ml).

The incidence of invasive mycoses caused by emergent fungal pathogens has risen considerably over the last two decades. This fact is related to several factors, including the increased occurrence of degenerative and malignant diseases in different populations, as well as the higher number of patients exposed to organ transplantation, immunosuppressive therapies, chemotherapy, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and invasive medical procedures. It is important to emphasize that emergent fungal infections are usually difficult to diagnose, refractory to conventional antifungal drugs, and associated with high mortality rates (8, 10, 26, 32, 34, 47, 51).

Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon spp. are reported mostly for cancer patients that have central venous catheters (22, 50-52). Although trichosporonemia represents a small percentage of all fungal invasive infections, Trichosporon spp. have been reported as the second- or third-most-common agents of yeast fungemia (13, 21, 51).

Phenotypic methods for Trichosporon species identification usually generate inconsistent results, and none of the commercial tests available include the whole new taxonomic categories in their databases (1, 36, 37). For instance, it has been mentioned in the literature that an isolate identified by molecular methods as Trichosporon dermatis was mistakenly identified as Trichosporon mucoides when Vitek Systems 1 and 2 (BioMérieux, France) were used (16). Furthermore, Ahmad et al. (1) reported that four isolates previously identified by Vitek 2 as Trichosporon asahii were identified as Trichosporon asteroides by molecular techniques. There is a consensus that molecular methods are required for accurate identification of this genus, but they are still costly and not suitable for most routine laboratories (38, 42).

Currently, the genus Trichosporon includes the following species as potential human pathogens: Trichosporon cutaneum, T. asahii, T. asteroides, T. mucoides, Trichosporon inkin, Trichosporon jirovecii, T. dermatis, Trichosporon domesticum, Trichosporon montevideense, Trichosporon japonicum, Trichosporon coremiiforme, Trichosporon faecale, and Trichosporon loubieri (7, 34, 38). Sugita et al. (42) reported that the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region is not suitable for Trichosporon species identification. Therefore, the analysis of the rDNA intergenic spacer (IGS) region is a crucial method which should be used to distinguish phylogenetically closely related species (42-44).

Considering the limitations of routine laboratories in conducting appropriate identification of Trichosporon spp., there is a lack of data for species distribution and antifungal susceptibility of hematogenous infections caused by this particular genus. Girmenia et al. (15) published the largest retrospective clinical study of invasive trichosporonosis documented during a period of 20 years. Despite representing the largest series of invasive trichosporonosis ever published before, only 30 of 287 isolates were identified to the species level.

Several authors have attempted to evaluate the antifungal susceptibilities of Trichosporon spp. but most of them still used the old nomenclature T. beigelii (17, 35, 48, 49). Antifungal susceptibilities of bloodstream isolates belonging to this genus have not yet been largely investigated. Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (38) performed antifungal susceptibility testing for Trichosporon spp. accurately identified by rDNA IGS1 region sequencing. However, only 9 out of 49 strains were recovered from bloodstream infections (BSI). Thereafter, the same group published a paper investigating T. asahii susceptibility testing (39), but once again, only 8 out of 18 isolates were recovered from BSI. To date, only limited data are available for species distribution and antifungal susceptibilities of BSI isolates of Trichosporon spp. accurately identified by molecular tools.

In the present study, we investigated species distribution and antifungal susceptibilities of 22 bloodstream Trichosporon isolates sequentially recovered from different patients hospitalized in five medical centers between 1995 and 2007.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

We evaluated a total of 22 Trichosporon sp. bloodstream isolates sequentially obtained from different patients admitted to five tertiary care hospitals in Sao Paulo, Brazil, between January 1995 and December 2004. The isolates were stored on 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 3% glycerol at −70°C. Of note, the isolates mentioned above were collected during multicentric surveillance studies of fungemia coordinated by our group (9, 10). The isolates were identified to the species level by sequencing the rDNA IGS1 region and were subsequently submitted to antifungal susceptibility testing by standard methods. Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) and Candida krusei (ATCC 6258) were used as quality control strains for antifungal susceptibility testing. T. asahii (CBS 2479 and CBS 2530), T. mucoides (CBS 7625), T. inkin (CBS 5585), T. asteroides (CBS 2481), and T. ovoides (CBS 7556) were used as control strains for Trichosporon molecular identification. As negative controls, Candida albicans (ATCC 90028) and C. parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) were used to check for the specificity of Trichosporon-specific oligonucleotides. The isolates used in the present study are displayed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Microbiological and clinical data for 22 episodes of Trichosporon sp. bloodstream infectionsa

| Reference strain and patient | Species | GenBank accession no. | Age of patient | Gender of patient | Associated condition(s) | CVC | Antifungal therapy | Other infection(s) | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBS 2479 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU934801 | |||||||

| 1 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU934808 | 39 yr | M | Cardiac failure | Present | AMB | Bacteremia | Death |

| 2 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU934809 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU934810 | 78 yr | M | Inflammatory gastrointestinal disease | Present | AMB | Staphylococcus aureus and/or Pseudomonas aeruginosa (BSI) | Death |

| 4 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938047 | 3 yr | M | Burn | Present | AMB | Soft tissue infections | Discharged |

| 5 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU980326 | 16 days | F | Premature birth + low wt | Present | AMB | Enterobacter sp. (BSI) | Death |

| 6 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938049 | 55 yr | F | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938050 | 6 yr | M | Cancer | Present | Double-blinded randomized study | None | Discharged |

| 8 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938051 | 49 yr | M | Lung neoplasia | Present | None | None | Death |

| 9 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938052 | 17 yr | M | Prune belly syndrome + chronic renal failure | Present | FLC + AMB | Escherichia coli + Enterococcus sp. (urine) and/or Staphylococcus sp. (BSI) | Death |

| 10 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938054 | NA | M | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 11 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938055 | NA | M | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 12 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938056 | 33 yr | M | Kidney transplant | Present | FLC | Death | |

| 13 | T. asahii genotype 1 | EU938058 | 77 yr | F | Inguinal hernia + postoperative enterectomy | Present | None | Bacterial sepsis | Death |

| CBS 2530 | T. asahii genotype 3 | EU934803 | |||||||

| 14 | EU934811 | 78 yr | M | Cardiac failure | Present | None | Discharged | ||

| 15 | T. asahii genotype 4 | EU938046 | 84 days | M | Premature birth + low wt + enterectomy | Present | FLC + AMB | Escherichia coli + Klebsiella sp. (BSI) | Discharged |

| CBS 2481 | T. asteroides | EU934802 | |||||||

| 16 | T. asteroides | EU934800 | 2 mo | F | Galactosemia + congenital cytomegalovirus syndrome | Present | AMB | Bacteremia | Discharged |

| 17 | T. asteroides | EU938059 | 3 yr | M | Testicle carcinoma | Present | NA | NA | Discharged |

| 18 | T. asteroides | EU938048 | 54 yr | F | Acute arterial embolism | Present | FLC | Discharged | |

| 19 | T. asteroides | EU938053 | 15 days | F | Premature birth + low wt | Present | AMB | BCP | Discharged |

| 20 | T. asteroides | EU938057 | 43 yr | M | Gunshot wound of abdomen + splenectomy + pancreatectomy | Present | FLC + AMB | Peritonitis + sepsis | Discharged |

| 21 | T. coremiiforme | EU934807 | 10 days | F | Pulmonary emphysema + pulmonary hypertension | Present | FLC | Candida sp. (oral) + Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Discharged |

| CBS 5585 | T. inkin | EU934804 | |||||||

| CBS 7556 | T. ovoides | EU934805 | |||||||

| CBS 7625 | T. mucoides | EU934806 | |||||||

| 22 | T. dermatis | EU938060 | 53 yr | F | Diabetes mellitus + systemic arterial hypertension | Present | FLC + AMB | Candida sp. (BSI) | Death |

Clinical and epidemiological data for four patients were not available. NA, not available; BCP, bacteremia during pregnancy; CVC, central venous catheter; M, male; F, female.

Screening of Trichosporon isolates by conventional methods.

Yeast isolates were obtained from blood cultures from the referred medical centers by using either Bactec 9000 (BD) or BacT/Alert 3D (BioMérieux, France). Yeast isolates from original cultures were plated onto CHROMagar Candida (CHROMagar Microbiology, Paris, France) to check for purity and viability. All strains able to produce arthroconidia, as revealed by their micromorphology on corn meal-Tween 80 agar, and able to hydrolyze urea were considered to belong to the genus Trichosporon and were further identified by molecular techniques (http://www.cbs.knaw.nl/databases) (3, 11, 18, 23, 38, 40).

DNA extraction.

The isolates were grown in Falcon tubes containing 2 ml yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium for 16 h, 30°C at 200 rpm in a gyrator with shaking for 48 h. DNA was extracted using the fast small-scale isolation protocol described elsewhere (27). RNA was removed by treatment with RNase A (Pharmacia) for 1 h at 37°C. DNA concentration and purity were determined by optical density at 260 nm and ratio optical density at 260/280 nm, respectively.

PCR assay and IGS1 region sequencing.

To confirm the correct genus identification, the primer pair TRF (5′-AGAGGCCTACCATGGTATCA-3′) and TRR (5′-TAAGACCCAATAGAGCCCTA-3′) was used (44). The samples were amplified in a Thermocycler (model 9600; Applied Biosystems) by using the following cycling parameters: one initial cycle of 94°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C, and 1 min at 72°C and a final cycle of 5 min at 72°C. For the accurate identification of Trichosporon strains to the species level, the IGS1 region was amplified by PCR using the following primer pair: 26F (5′-ATCCTTTGCAGACGACTTGA-3′) and 5SR (5′-AGCTTGACTTCGCAGATCGG-3′) and 2× PCR Master Mix (Promega). PCR was performed with one initial cycle of 94°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 57°C, and 2 min at 72°C and a final cycle of 5 min at 72°C. PCR products were sequenced by using the dideoxynucleotide method in an ABI Prism 3100 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, CA). The sequencing reaction included the primer pair 26F and 5SR (42) and the BigDye Terminator reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, CA) and was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nucleotide sequences were submitted for BLAST analysis at the NCBI site (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) for species identification. Only sequences deposited in GenBank showing high similarities with our query sequences and an E value of lower than 10−5 were used in this study.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Sequences were aligned using BioEdit software (v7.09). Aligned sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis conducted with Mega 4.1 Beta Software (v4.1 Beta). The method used for tree constructions was the unweighted-pair group method using average linkages (UPGMA). Phylogram stability was accessed by bootstrapping with 1,000 pseudoreplications. To root the phylogenetic tree for all the Trichosporon isolates, the IGS1 sequences of Cryptococcus neoformans (GenBank accession number EF211300) and Cryptococcus gatii (GenBank accession number EF211336) were used as outgroups.

In vitro susceptibility testing.

Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed using the broth microdilution assay according to an adaptation of the methodology recommended for Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans and according to CLSI approved standard M27-A2 (31). The following antifungal drugs, supplied by the manufacturers as pure standard compounds, were tested at the indicated concentration ranges: amphotericin B (AMB), 0.015 to 8 μg/ml (Sigma Chemical Corporation, St. Louis, MO); 5-flucytosine (5FC), 0.125 to 64 μg/ml (Sigma Chemical Corporation, St. Louis, MO); itraconazole (ITC), 0.03 to 16 μg/ml (Janssen Pharmaceutical, Titusville, NJ); fluconazole (FLC), 0.125 to 64 μg/ml; voriconazole (VRC), 0.03 to 16 μg/ml (Pfizer Incorporated, New York, NY); and caspofungin (CAS), 0.03 to 16 μg/ml (Merck Research Laboratories, NJ). Briefly, the medium used was RPMI-1640 with l-glutamine, without bicarbonate, buffered at pH 7.0 with 0.165 M morpholinepropanesulfonic acid. The yeast inoculum suspension was prepared using a spectrophotometer to obtain a final yeast concentration of 0.5 × 103 to 2.5 × 103 cells/ml in each well of the microtiter plate. The assays were incubated at 35°C. Cell cultures were incubated for 48 h as suggested by Brito et al. (6). Quality control strains (C. parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and C. krusei ATCC 6258) were included on each day of the assay to check the accuracy of the drug dilutions and the reproducibility of the results. The MIC endpoint for AMB was considered the lowest tested drug concentration able to prevent any visible growth. The MIC for triazoles, CAS, and 5FC was considered the lowest tested drug concentration causing a significant reduction (approximately 50%) in growth compared to the growth of the drug-free positive control (31).

Statistical analysis.

Differences in mortality rates between adults and infants were analyzed by Fisher's test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant for all the statistics analyzed.

GenBank accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers were as follows: EU934801, EU934808, EU934809, EU934810, EU938047, EU980326, EU938049, EU938050, EU938051, EU938052, EU938054, EU938055, EU938056, EU938058, EU934803, EU934811, EU938046, EU934802, EU934800, EU938059, EU938048, EU938053, EU938057, EU934807, EU934804, EU934805, EU934806, and EU938060.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical data.

We were able to collect clinical information for 18 of 22 patients with Trichosporon invasive infections. Our series was represented by pediatric (44%) and adult patients exhibiting a large variety of underlying conditions, including premature birth, surgery, organ failures, inflammatory gastrointestinal disease, and cancer, who frequently developed systemic bacterial infections (67%) and had a central venous catheter in place at the onset of fungemia. Mortality rates of infants were significantly lower than those for adults (30% against 87.5%, respectively; P = 0.025) (Table 1).

Molecular identification of Trichosporon isolates.

To double-check for accurate identification of the genus, we performed diagnostic PCR using primers TRR and TRF (44). This pair of primers is Trichosporon specific and amplifies part of the nucleotide sequences of the rDNA small subunit (18S). DNA bands of approximately 170 bp were obtained for all the isolates tested and for Trichosporon reference strains (data not shown). In addition, there was no amplification of DNA isolated from Candida spp. (negative control). Therefore, our strains were confirmed to be Trichosporon spp.

For species identification, DNA fragments of the IGS1 region were amplified and DNA sequences obtained were sent to the GenBank genome database at the NCBI website (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) using BLAST to compare gene sequences. All the Trichosporon control strains were unambiguously identified by sequencing. This fact, together with an E value of 0 for all the BLAST matches, supported our accurate final identification. The 22 clinical isolates were identified as follows: 15 T. asahii isolates, five T. asteroides isolates, one T. coremiiforme isolate, and one T. dermatis isolate (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analysis.

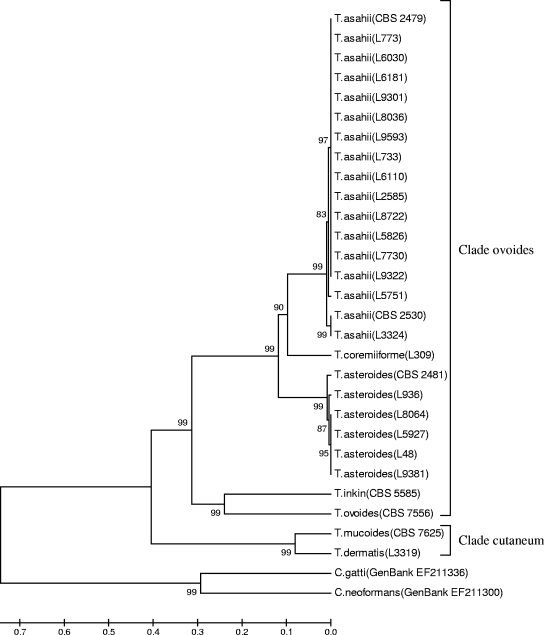

UPGMA analysis using 1,000 pseudoreplications of the IGS1 region sequences of the isolates, as well as reference strains, adequately resolved all Trichosporon species (Fig. 1). The results obtained by our phylogenetic analysis reinforce the accurate molecular identification in the present study.

FIG. 1.

Rooted phylogenetic tree of Trichosporon clinical isolates based on confidently aligned IGS1 rDNA sequences and obtained by UPGMA analysis and 1,000 bootstrap simulations.

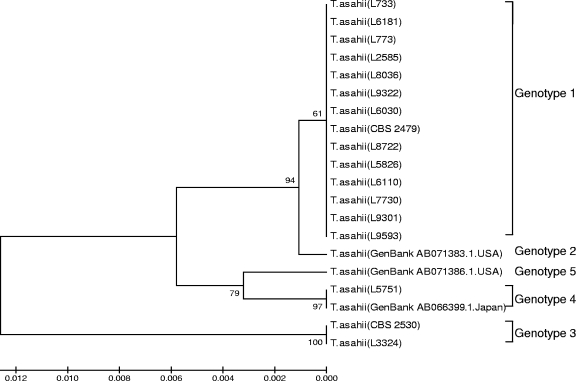

All T. asahii isolates clustered together, although minor differences were observed between isolates related to their genetic relatedness (Fig. 1). We decided to further investigate this genetic variability within the species. We constructed a phylogenetic tree using the UPGMA method including rDNA IGS1 sequences of our T. asahii isolates and a representative sequence of each T. asahii genotype described by Sugita et al. (42) and Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (39) deposited in GenBank. We found that the majority of our isolates belonged to genotype 1 (86.7%), while one isolate belonged to genotype 3 and another isolate belonged to genotype 4 (Fig. 2). Here we describe the first T. asahii isolate belonging to genotype 4 from South America. Unfortunately, we could not include genotype 6 in our analysis because IGS1 sequences for this genotype were not available from the GenBank database.

FIG. 2.

Rooted phylogenetic tree of Trichosporon asahii IGS1 genotypes based on confidently aligned sequences and obtained by UPGMA analysis and 1,000 bootstrap simulations.

Interestingly, the only T. coremiiforme isolate found in our study shares a common branch with T. asahii, with a bootstrap support higher than 90, indicating high phylogenetic relation (Fig. 1). All T. asteroides isolates clustered together and showed high genetic relatedness within the group (bootstrap ≥ 99) and share a common branch with T. asahii and T. coremiiforme (bootstrap ≥ 99). We have included in our sequencing analysis one isolate each of reference strains T. inkin and T. ovoides (CBS 5585 and 7556, respectively). The two species clustered together within the same clade (bootstrap ≥ 99), demonstrating high phylogenetic relation. Another highly related cluster was composed of T. dermatis and T. mucoides, showing a bootstrap support of ≥99 (Fig. 1).

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

MICs of the 22 strains of Trichosporon spp. tested ranged from 0.25 to 4 μg/ml for AMB, 0.125 to 8 μg/ml for FLC, 0.03 to 0.125 μg/ml for ITC, 0.03 to 0.06 μg/ml for VRC, 0.5 to >64 μg/ml for 5FC, and 2 to >16 μg/ml for CAS. Table 2 summarizes ranges and geometric means of MICs obtained for Trichosporon sp. isolates against the six antifungal drugs tested.

TABLE 2.

In vitro activity of six antifungal agents against 22 Trichosporon sp. strains tested by CLSI microdilution assay

| Trichosporon sp. (no. of isolates) | Cell incubation period (h) | MIC (μg/ml) for indicated antifungal agenta

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMB

|

FLC

|

ITC

|

VRC

|

5FC

|

CAS

|

||||||||

| Range | GM | Range | GM | Range | GM | Range | GM | Range | GM | Range | GM | ||

| T. asahii (15) | 24 | 0.5-2 | 0.9 | 0.25-2 | 0.8 | 0.03-0.125 | 0.07 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.5-32 | 12.1 | 2->16 | 14.6 |

| 48 | 0.5-4 | 1.4 | 0.25-8 | 1.3 | 0.03-0.125 | 0.08 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 4->64 | 27.9 | 16->16 | 16 | |

| T. asteroides (5) | 24 | 0.25-1 | 1 | 0.125-0.5 | 0.3 | 0.03-0.125 | 0.05 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 0.5-32 | 8 | 2->16 | 10.6 |

| 48 | 0.5-4 | 1.5 | 0.5-1 | 0.8 | 0.03-0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03-0.06 | 0.03 | 4->64 | 16 | 16->16 | 16 | |

| T. dermatis (1) | 24 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 8 | 16 | ||||||

| 48 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 16 | >16 | |||||||

| T. coremiiforme (1) | 24 | 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 2 | 8 | ||||||

| 48 | 1 | 1 | 0.125 | 0.03 | 16 | >16 | |||||||

GM, geometric mean.

Of note, 47% of all T. asahii isolates exhibited AMB MICs of ≥2 μg/ml. CAS MICs obtained for all the Trichosporon sp. isolates tested were consistently high (MIC ≥ 2 μg/ml). Most isolates (87%) had high MICs for 5FC. With regard to the azoles, the three drugs tested were active against all the species, while VRC was the most effective antifungal agent. All the isolates had MICs of ≤0.06 μg/ml.

DISCUSSION

This report represents the largest published series addressing species distribution, prevalence of T. asahii genotypes and antifungal susceptibility profiling of Trichosporon bloodstream isolates accurately identified to the species level by using rDNA IGS1 sequencing.

Surprisingly, in contrast to previously published data, cancer and neutropenia were both present in a limited number of patients (15, 26). Most of our patients were individuals with several underlying associated conditions, such as premature birth, surgery, burns, organ failure, and gastrointestinal inflammatory disease. Of note, 12 of 18 patients (67%) had an episode of systemic bacterial infection previously or concomitantly to the fungemia. As expected, all patients had a central venous catheter in place at the time of the diagnosis. This finding reinforces the concept that invasive Trichosporon infections may occur in non-cancer patients who present chronic illness and disruption of skin and mucous membranes (12). Crude mortality was significantly higher for adults than for infants.

In our study, we have found that the vast majority of the isolates were identified as T. asahii (approximately 68%) (Table 1). T. asahii has extensively been recognized as an emergent agent of fungal invasive infections worldwide (4, 5, 19, 20, 28, 30, 46, 51, 53). The largest multicentric restrospective study addressing Trichosporon invasive infections found that T. asahii accounted for 15 of 30 isolates (50%) identified to the species level (15). In the series of 49 Trichosporon isolates published by Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (38), 15 strains were identified as T. asahii by using IGS1 region sequencing, including eight of nine Trichosporon isolates recovered from BSI. Considering the difficulties for routine laboratories in correctly identifying Trichosporon spp., the true prevalence of fungemia due to T. asahii may not be accurately estimated. In terms of antifungal susceptibility, in accordance with previously published data, a significant number of T. asahii strains exhibited poor susceptibility to AMB but good in vitro susceptibility to triazoles (2, 14, 33, 49, 54).

Surprisingly, T. asteroides was found to be the second-most-common species isolated from BSI due to Trichosporon spp. in our study (approximately 23%) (Table 1), while the isolates did not originate from the same institution (therefore not being characterized as an outbreak). T. asteroides is a causative agent of superficial infections (42). The first case report of disseminated infection due to this agent was published in 2002, describing an intensive care unit female patient with multiple organ failure and T. asteroides-positive cultures of blood, urine, aspiration fluid, and catheter tip swabs (22). Ahmad et al. (1) reported the isolation of three T. asteroides strains recovered from blood and one from a catheter tip swab. However, it is important to emphasize that both studies used the rDNA ITS region for Trichosporon sp. identification, a method recently replaced by rDNA IGS1 sequencing (42). In our series, except for one strain of T. asteroides that had an AMB MIC of 4 μg/ml, all the other clinical isolates of this species were susceptible to AMB, FLC, ITC, and VRC.

There are very few published instances where T. coremiiforme is described as the cause of human diseases. Interestingly, despite the fact that Sugita et al. (42) refer to this species as nonpathogenic, the T. coremiiforme type strain (CBS 2482) was originally isolated from a patient with a fungal lesion of the head. Recently, T. coremiiforme has been isolated from subcutaneous abscesses and urine (38). To our knowledge, the present case represents the first report of a BSI caused by T. coremiiforme.

We also recovered in our series an isolate of T. dermatis from blood (Table 1). T. dermatis has been associated mostly with superficial infections (16). The series of Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (38) documented eight cases of T. dermatis causing infections. However, only one of these isolates was recovered from blood, while all the others were isolated from the skin, nails, and subcutaneous lesions of patients. A recent paper published by Gunn et al. (16) documented a case of trichosporonosis due to T. dermatis in a 13-month-old male with a history of autoimmune enteropathy under immunosuppressant therapy, maintained with total parenteral nutrition through a central venous catheter. The isolate was initially misidentified as T. mucoides after sequencing the ITS region. It is important to emphasize that T. dermatis is phylogenetically closely related to T. mucoides and cannot be distinguished when ITS sequences are used for comparison. Of note, in contrast to T. dermatis, T. mucoides has been associated mostly with invasive infection (16). Therefore, previously published data on trichosporonemia must have miscalculated the number of BSI which could have been caused by T. dermatis. This fact emphasizes the necessity of correctly identifying Trichosporon spp. by using rDNA IGS1 sequencing in order to avoid underestimation of the prevalence of a recently considered emergent species.

Sequence polymorphisms are important to characterize strains and assess their relatedness to genotypic levels, a relevant step employed in epidemiologic studies of all microorganisms (41). In the present study, we investigated sequence polymorphisms of the IGS1 region of 15 T. asahii BSI strains. In a series of 18 isolates from Spain, Argentina, and Brazil, in addition to 43 sequences deposited in GenBank, Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (39) observed that six different genotypes of T. asahii can be detected, instead of the five genotypes previously described for this species by Sugita et al. (42). Here we describe that the majority of our T. asahii isolates (approximately 87%) belonged to genotype 1 (Fig. 2). These data corroborate the findings of Sugita et al. (42). When characterizing the genotypes of 43 strains of T. asahii, the authors also reported a predominance of genotype 1 within Japanese isolates (a prevalence of 87%). In addition, Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (39) found that genotype 1 accounted for 57.3% of the isolates obtained from South and North America, China, and Japan. The prevalence of genotype 1 among Trichosporon isolates in three different series suggests a worldwide predominance of this genotype among superficial and invasive cases of trichosporonosis. Further investigations including a larger number of strains are necessary to confirm this finding.

We document the first description of T. asahii genotype 4 in South America. Until the present study, strains belonging only to genotypes 1, 3, and 6 have been described for this continent (39). Sugita et al. (42) reported that genotypes 2 and 4 were detected only in Japan. However, Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (39) inferred that all genotypes may be found in all geographic regions. Until the present moment, genotype 2 has not been described in South America. As reported by Rodriguez-Tudela et al. (39), this genotype differs from genotype 1 by only one nucleotide (thymine instead of adenine), suggesting a likely recent evolution of genotype 2 in Japan.

We found high genetic relatedness of our T. coremiiforme isolate and the T. asahii cluster (Fig. 1). Indeed, T. coremiiforme was considered for a long time to be a variety of T. asahii (45). Despite the fact that the two species are almost indistinguishable (99.7% similarity), when ITS region sequences are used for comparisons, the IGS1 regions of T. coremiiforme and T. asahii are 78.8% similar (42). Therefore, they should be considered different species.

We state here that all T. asteroides isolates were included in the same cluster, sharing a common branch with T. asahii and T. coremiiforme (Fig. 1). Of note, T. asteroides and T. asahii DNA sequences are similar by 98.7% (for the ITS region) and 75.1% (for the IGS1 region) (42). It is important to emphasize that all three species mentioned above belong to the same clade (ovoides), according to the taxonomic classification of the genus Trichosporon proposed by Middelhoven et al. (29). In addition, the two reference strains, T. inkin and T. ovoides, which clustered together and presented a high bootstrap (≥99) also belong to the clade ovoides (29).

Finally, the clinical isolates T. dermatis and T. mucoides shared the same cluster with a high bootstrap (≥99). As mentioned before, both species have undistinguishable ITS sequences and biochemical assimilation profiling (16). They belong to the clade cutaneum, according to the classification of Middelhoven et al. (29).

This paper reinforces the relevance of correctly identifying and testing Trichosporon BSI isolates with different antifungal compounds. We have documented the great diversity of different species causing fungemia and a high frequency of T. asteroides isolation from blood, a frequency lower than that of T. asahii only. The different Trichosporon species also exhibited peculiar in vitro antifungal susceptibility profiles, including a significant number of T. asahii isolates showing low susceptibility to AMB. T. asahii genotype 1 was confirmed to be the most prevalent agent of T. asahii invasive infections in Brazil, as published elsewhere. However, other genotypes can occur in South America, such as genotype 4, as described in the present study. Further investigations using a larger number of Trichosporon isolates identified by molecular methods will contribute to the understanding of the epidemiology and species distribution of the genus worldwide.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), Brazil (grant 2005/02006-0). G.M.C. and A.S.A.M. received postdoctoral fellowships from FAPESP (grant 2005/04442-1) and CAPES (PRODOC 2005), respectively. We are very greatful to T. Guimarães, D. Bergamasco, D. Santos, R. Rosas, and C. Pereira for the collection of clinical data.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, S., M. Al-Mahmeed, and Z. U. Khan. 2005. Characterization of Trichosporon species isolated from clinical specimens in Kuwait. J. Med. Microbiol. 54639-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asada, N., H. Uryu, M. Koseki, M. Takeuchi, M. Komatsu, and K. Matsue. 2006. Successful treatment of breakthrough Trichosporon asahii fungemia with voriconazole in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43e39-e41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnett, J. A., R. W. Payne, and D. Yarrow. 2000. Yeasts: characteristics and identification, 3rd ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 4.Bayramoglu, G., M. Sonmez, I. Tosun, K. Aydin, and F. Aydin. 2008. Breakthrough Trichosporon asahii fungemia in neutropenic patient with acute leukemia while receiving caspofungin. Infection 3668-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biasoli, M. S., D. Carlson, G. J. Chiganer, R. Parodi, A. Greca, M. E. Tosello, A. G. Luque, and A. Montero. 2008. Systemic infection caused by Trichosporon asahii in a patient with liver transplant. Med. Mycol. 46719-723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brito, L. R., T. Guimaraes, M. Nucci, R. C. Rosas, L. Paula Almeida, D. A. Da Matta, and A. L. Colombo. 2006. Clinical and microbiological aspects of candidemia due to Candida parapsilosis in Brazilian tertiary care hospitals. Med. Mycol. 44261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chagas-Neto, T. C., G. M. Chaves, and A. L. Colombo. 2008. Update on the genus Trichosporon. Mycopathologia 166121-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colombo, A. L., A. S. Melo, R. F. Crespo Rosas, R. Salomao, M. Briones, R. J. Hollis, S. A. Messer, and M. A. Pfaller. 2003. Outbreak of Candida rugosa candidemia: an emerging pathogen that may be refractory to amphotericin B therapy. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 46253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo, A. L., M. Nucci, B. J. Park, S. A. Nouer, B. Arthington-Skaggs, D. A. da Matta, D. Warnock, and J. Morgan. 2006. Epidemiology of candidemia in Brazil: a nationwide sentinel surveillance of candidemia in eleven medical centers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 442816-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Matta, D. A., L. P. de Almeida, A. M. Machado, A. C. Azevedo, E. J. Kusano, N. F. Travassos, R. Salomao, and A. L. Colombo. 2007. Antifungal susceptibility of 1000 Candida bloodstream isolates to 5 antifungal drugs: results of a multicenter study conducted in Sao Paulo, Brazil, 1995-2003. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 57399-404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Hoogs, G. S., J. Guarro, J. Gene, and M. J. Figueras. 2000. Atlas of clinical fungi, 2nd ed. Guanabara, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 12.Ebright, J. R., M. R. Fairfax, and J. A. Vazquez. 2001. Trichosporon asahii, a non-Candida yeast that caused fatal septic shock in a patient without cancer or neutropenia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33E28-E30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleming, R. V., T. J. Walsh, and E. J. Anaissie. 2002. Emerging and less common fungal pathogens. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 16915-933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fournier, S., W. Pavageau, M. Feuillhade, S. Deplus, A. M. Zagdanski, O. Verola, H. Dombret, and J. M. Molina. 2002. Use of voriconazole to successfully treat disseminated Trichosporon asahii infection in a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21892-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girmenia, C., L. Pagano, B. Martino, D. D'Antonio, R. Fanci, G. Specchia, L. Melillo, M. Buelli, G. Pizzarelli, M. Venditti, and P. Martino. 2005. Invasive infections caused by Trichosporon species and Geotrichum capitatum in patients with hematological malignancies: a retrospective multicenter study from Italy and review of the literature. J. Clin. Microbiol. 431818-1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunn, S. R., X. T. Reveles, J. D. Hamlington, L. C. Sadkowski, T. L. Johnson-Pais, and J. H. Jorgensen. 2006. Use of DNA sequencing analysis to confirm fungemia due to Trichosporon dermatis in a pediatric patient. J. Clin. Microbiol. 441175-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hata, K., J. Kimura, H. Miki, T. Toyosawa, T. Nakamura, and K. Katsu. 1996. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of ER-30346, a novel oral triazole with a broad antifungal spectrum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 402237-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hazen, K. C. 1995. New and emerging yeast pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 8462-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbrecht, R., J. Waller, P. Dufour, H. Koenig, B. Lioure, L. Marcellin, and F. Oberling. 1992. Rare opportunistic fungal diseases in patients with organ or bone marrow transplantation. Agressologie 3377-80. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoy, J., K. C. Hsu, K. Rolston, R. L. Hopfer, M. Luna, and G. P. Bodey. 1986. Trichosporon beigelii infection: a review. Rev. Infect. Dis. 8959-967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krcmery, V., Jr., F. Mateicka, A. Kunova, S. Spanik, J. Gyarfas, Z. Sycova, and J. Trupl. 1999. Hematogenous trichosporonosis in cancer patients: report of 12 cases including 5 during prophylaxis with itraconazol. Support Care Cancer 739-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kustimur, S., A. Kalkanci, K. Caglar, M. Dizbay, F. Aktas, and T. Sugita. 2002. Nosocomial fungemia due to Trichosporon asteroides: firstly described bloodstream infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 43167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacaz, C. S., E. Porto, J. E. C. Martins, E. M. Neins-Vaccari, and N. T. Melo (ed.). 2002. Tratado de micologia medica, 9th ed. Sarvier Publishers, São Paulo, Brazil.

- 24.Reference deleted.

- 25.Marty, F. M., D. H. Barouch, E. P. Coakley, and L. R. Baden. 2003. Disseminated trichosporonosis caused by Trichosporon loubieri. J. Clin. Microbiol. 415317-5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsue, K., H. Uryu, M. Koseki, N. Asada, and M. Takeuchi. 2006. Breakthrough trichosporonosis in patients with hematologic malignancies receiving micafungin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42753-757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Melo, A. S., L. P. de Almeida, A. L. Colombo, and M. R. Briones. 1998. Evolutionary distances and identification of Candida species in clinical isolates by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD). Mycopathologia 14257-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer, M. H., V. Letscher-Bru, J. Waller, P. Lutz, L. Marcellin, and R. Herbrecht. 2002. Chronic disseminated Trichosporon asahii infection in a leukemic child. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35e22-e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Middelhoven, W. J., G. Scorzetti, and J. W. Fell. 2004. Systematics of the anamorphic basidiomycetous yeast genus Trichosporon Behrend with the description of five novel species: Trichosporon vadense, T. smithiae, T. dehoogii, T. scarabaeorum and T. gamsii. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54975-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakajima, M., T. Sugita, and Y. Mikami. 2007. Granuloma associated with Trichosporon asahii infection in the lung: unusual pathological findings and PCR detection of Trichosporon DNA. Med. Mycol. 45641-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NCCLS/CLSI. 2002. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts, 2nd ed. Approved standard M27-A2. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, PA.

- 32.Padhye, A. A., S. Verghese, P. Ravichandran, G. Balamurugan, L. Hall, P. Padmaja, and M. C. Fernandez. 2003. Trichosporon loubieri infection in a patient with adult polycystic kidney disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41479-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paphitou, N. I., L. Ostrosky-Zeichner, V. L. Paetznick, J. R. Rodriguez, E. Chen, and J. H. Rex. 2002. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of Trichosporon species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 461144-1146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pasqualotto, A. C., T. C. Sukiennik, L. C. Severo, C. S. de Amorim, and A. L. Colombo. 2005. An outbreak of Pichia anomala fungemia in a Brazilian pediatric intensive care unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 26553-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perparim, K., H. Nagai, A. Hashimoto, Y. Goto, T. Tashiro, and M. Nasu. 1996. In vitro susceptibility of Trichosporon beigelii to antifungal agents. J. Chemother. 8445-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pincus, D. H., S. Orenga, and S. Chatellier. 2007. Yeast identification—past, present, and future methods. Med. Mycol. 4597-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramani, R., S. Gromadzki, D. H. Pincus, I. F. Salkin, and V. Chaturvedi. 1998. Efficacy of API 20C and ID 32C systems for identification of common and rare clinical yeast isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 363396-3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez-Tudela, J. L., T. M. Diaz-Guerra, E. Mellado, V. Cano, C. Tapia, A. Perkins, A. Gomez-Lopez, L. Rodero, and M. Cuenca-Estrella. 2005. Susceptibility patterns and molecular identification of Trichosporon species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 494026-4034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Tudela, J. L., A. Gomez-Lopez, A. Alastruey-Izquierdo, E. Mellado, L. Bernal-Martinez, and M. Cuenca-Estrella. 2007. Genotype distribution of clinical isolates of Trichosporon asahii based on sequencing of intergenic spacer 1. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 58435-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sidrim, J. J. C., and M. F. G. Rocha. 2004. Micologia médica à luz de autores comtemporâneos. Guanabara, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- 41.Soll, D. R. 2000. The ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 13332-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sugita, T., M. Nakajima, R. Ikeda, T. Matsushima, and T. Shinoda. 2002. Sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer 1 regions of Trichosporon species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401826-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reference deleted.

- 44.Sugita, T., A. Nishikawa, and T. Shinoda. 1998. Rapid detection of species of the opportunistic yeast Trichosporon by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 361458-1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sugita, T., A. Nishikawa, T. Shinoda, and H. Kume. 1995. Taxonomic position of deep-seated, mucosa-associated, and superficial isolates of Trichosporon cutaneum from trichosporonosis patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 331368-1370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Téllez-Castillo, C. J., M. Gil-Fortuno, I. Centelles-Sales, S. Sabater-Vidal, and F. Pardo Serrano. 2008. Trichosporon asahii fatal infection in a preterm newborn. Rev. Chilena Infectol. 25213-215. (In Spanish.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tuon, F. F., G. M. de Almeida, and S. F. Costa. 2007. Central venous catheter-associated fungemia due to Rhodotorula spp.—a systematic review. Med. Mycol. 45441-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Uchida, K., Y. Nishiyama, N. Yokota, and H. Yamaguchi. 2000. In vitro antifungal activity of a novel lipopeptide antifungal agent, FK463, against various fungal pathogens. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 531175-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uzun, O., S. Arikan, S. Kocagoz, B. Sancak, and S. Unal. 2000. Susceptibility testing of voriconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole and amphotericin B against yeast isolates in a Turkish University Hospital and effect of time of reading. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 38101-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walsh, T. J. 1990. Role of surveillance cultures in prevention and treatment of fungal infections. NCI Monogr. 943-45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walsh, T. J., A. Groll, J. Hiemenz, R. Fleming, E. Roilides, and E. Anaissie. 2004. Infections due to emerging and uncommon medically important fungal pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10(Suppl. 1)48-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Walsh, T. J., J. W. Lee, G. P. Melcher, E. Navarro, J. Bacher, D. Callender, K. D. Reed, T. Wu, G. Lopez-Berestein, and P. A. Pizzo. 1992. Experimental Trichosporon infection in persistently granulocytopenic rabbits: implications for pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of an emerging opportunistic mycosis. J. Infect. Dis. 166121-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walsh, T. J., K. R. Newman, M. Moody, R. C. Wharton, and J. C. Wade. 1986. Trichosporonosis in patients with neoplastic disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 65268-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wolf, D. G., R. Falk, M. Hacham, B. Theelen, T. Boekhout, G. Scorzetti, M. Shapiro, C. Block, I. F. Salkin, and I. Polacheck. 2001. Multidrug-resistant Trichosporon asahii infection of nongranulocytopenic patients in three intensive care units. J. Clin. Microbiol. 394420-4425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]