Abstract

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a tick-borne viral zoonosis which occurs throughout Africa, Eastern Europe, and Asia and results in an approximately 30% fatality rate. A reverse transcription-PCR assay including a competitive internal control was developed on the basis of the most up-to-date genome information. Biotinylated amplification products were hybridized to DNA macroarrays on the surfaces of polymer supports, and hybridization events were visualized by incubation with a streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate and the formation of a visible substrate precipitate. Optimal assay conditions for the detection of as few as 6.3 genome copies per reaction were established. Eighteen geographically and historically diverse CCHF virus strains representing all clinically relevant isolates were detected. The feasibility of the assay for clinical diagnosis was validated with acute-phase patient samples from South Africa, Iran, and Pakistan. The assay provides a specific, sensitive, and rapid method for CCHF virus detection without requiring sophisticated equipment. It has usefulness for the clinical diagnosis and surveillance of CCHF infections under limited laboratory conditions in developing countries or in field situations.

Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever (CCHF) is a severe viral infection transmitted by hard ticks (Ixodidae) of the genus Hyalomma. It has a case fatality rate around 30% and can be transmitted from human to human in the nosocomial setting (14, 22). The disease is endemic in large areas of sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle and Far East, as well as in Eastern Europe. A significant increase of cases in countries such as Kosovo, Albania, Turkey, Iran, and Greece has recently been observed (1, 9, 15-18, 20, 21, 23). The causative CCHF virus is an enveloped, segmented negative-stranded RNA virus of the family Bunyaviridae, genus Nairovirus. It is classified as a biosafety level 4 agent.

Due to clinical similarity between CCHF and other diseases, proper triage and isolation of patients depends on laboratory confirmation of the diagnosis (15). Available diagnostic methods include virus culture, antigen-specific enzyme-linked immunoassay, antibody-specific enzyme-linked immunoassay, and reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (2, 4, 5, 24). Virus detection in the acute stage of disease is necessary, and RT-PCR provides the best sensitivity (8).

Conventional RT-PCR protocols take up to 8 h for cDNA synthesis, amplification, and gel analysis and in some instances a second round of nested amplification (3, 19). Sequencing of RT-PCR products is needed for strain identification. A real-time RT-PCR procedure for CCHF virus is difficult to develop due to remarkable genetic variability among virus strains (11, 25, 26). Current protocols are often not appropriate for field-based outbreak investigations and may be difficult to implement in those countries where CCHF virus is endemic. Simpler, field-compatible assays are required. Such an approach is described here.

A robust one-step RT-PCR assay with an internal control was established, using the most recent genome information. Based on our prior experiences (25), the assay was formulated for compatibility with an inexpensive and simple nonfluorescent DNA macroarray hybridization platform. Detection with the naked eye was possible by using simple and robust biotin/streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase conjugate chemistry in combination with a tetramethylbenzidine substrate, resulting in the formation of a clearly visible dark precipitate at array positions where DNA-DNA hybridizations took place. No gel analysis was necessary. The possible patterns of hybridization spots were sufficiently heterogeneous to facilitate reliable differentiation among virus strains. Validation was done with strain collections from several collaborating biosafety level 4 facilities, covering essentially the full range of global diversity of CCHF virus (see Fig. 3). Clinical evaluation utilized a comprehensive panel of original clinical samples from patients with confirmed cases of CCHF, collected over almost 20 years by a WHO reference facility.

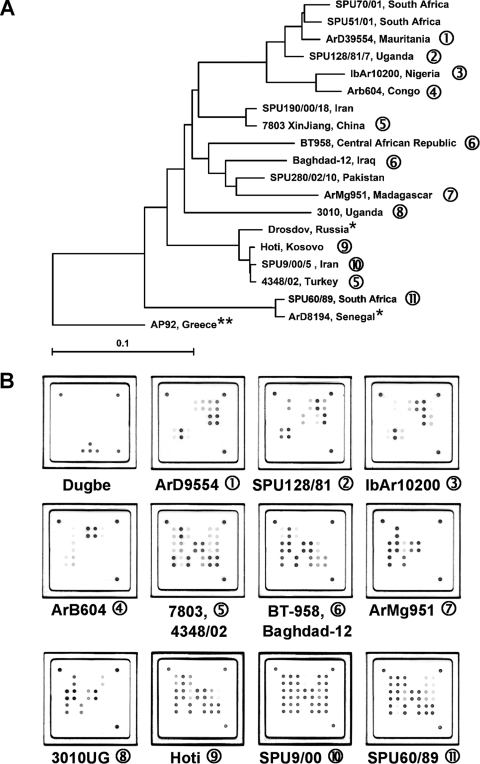

FIG. 3.

(A) Global distribution and phylogenetic relationships of CCHF virus strains selected for the design and validation of the assay. Phylogenetic analysis was based on 450-bp sequences of the CCHF virus S segment available in the NCBI database, and the phylogenetic tree was generated by the neighbor-joining method with TreeCon for Windows, version 1.3b (Yves van de Peer, University Konstanz, Germany). *, these CCHF virus strains were not available for testing with the novel universal CCHF virus quantitative RT-PCR assay, but genetically closely related isolates have been tested. **, strain AP92 has also not been available for testing. It was isolated from a Rhipicephalus bursa tick and has never been associated with human disease. (B) Representative hybridization patterns of CCHF virus strains listed in Table 2. Different strains of CCHF virus show individual hybridization patterns on the macroarray. However, these patterns are based only on sequence variability within an approximately 25-nt region of the CCHF virus S segment. Therefore, they cannot be considered unique for a specific CCHF virus strain, as shown in patterns 5 and 6. Dugbe virus, a nonpathogenic nairovirus closely related to CCHF virus, is not detected by the CCHF virus-specific array. Note that the internal control spots are not visible in the CCHF virus patterns, as the amplification of the internal control RNA is suppressed in the presence of high concentrations of CCHF virus RNA (also compare Fig. 2).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus strains.

Eighteen CCHF virus strains representing all genetic lineages described worldwide (7) were selected from the strain collections of participating laboratories (Table 1). The material was quantified by real-time RT-PCR (25) and tested by the conventional CCHF virus assay described here. RNAs from all strains were successfully amplified.

TABLE 1.

CCHF virus strains used for validation of the RT-PCR assay

| CCHF virus isolate | Origin | NCBI GenBank accession no. | Log RNA copies per ml |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7803 XinJiang | China | AF354296 | 5.2 |

| Ug3010 | Congo | U88416 | 7.1 |

| ArB604 “1976” | Congo | U15092 | 5.4 |

| SPU190/00/18 | Iran | AY905654 | 5.8 |

| SPU9/00/5 | Iran | AY905653 | 6.3 |

| Baghdad-12 | Iraq | AJ538196 | 4.5 |

| ArMg951 | Madagascar | U15024 | 9.3 |

| ArD39554 | Mauritania | U15089 | 7.9 |

| IbAr10200 | Nigeria | U88410 | 8.9 |

| SPU280/02/10 | Pakistan | AY905663 | 7.1 |

| SPU68/98 | South Africa | AY905639 | 6.5 |

| SPU60/89 | South Africa | AY905636 | 5.9 |

| SPU70/01 | South Africa | AY905650 | 6.2 |

| SPU51/01 | South Africa | AY905649 | 6.6 |

| 4348/02 | Turkey | DQ211649 | 4.0 |

| SPU128/81/7 | Uganda | DQ076415 | 5.5 |

| Hoti | Yugoslavia (Kosovo) | DQ133507 | 4.3 |

| Bangui BT-958 | Central African Republic | EF123122 | 6.9 |

Clinical samples.

Clinical material was provided by the Special Pathogens Unit of the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Sandringham, South Africa. A total of 63 serum samples from 31 patients with confirmed CCHF, received from 1986 to 2006 and stored at −70°C, were tested. Of the 31 confirmed cases of CCHF included in the study, 27 occurred in widely separated locations in South Africa and Namibia, 3 occurred in Iran, and 1 occurred in Pakistan. Serum had been collected 1 to 18 days (mean, 6 days; standard deviation [SD], 2.8 days) after the onset of disease. Viral loads of the stored samples were quantified by real-time RT-PCR (25) and ranged from 1.6 × 103 to 5 × 108 genome copies per ml (mean, 106 genome copies per ml). In addition, a panel of 128 serum samples collected from healthy individuals was also included in the study as negative controls.

RNA standards and internal control.

A synthetic RNA standard was generated by amplifying the full small (S) segment of CCHF virus strain BT-958 (EF123122) as described before (13). After TA cloning of the fragment into Escherichia coli plasmid pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Germany) and sequencing, a clone with a correct insert sequence was selected and the complete insert including a plasmid-derived T7 promoter was amplified by PCR. RNA was transcribed from the purified PCR product with the MegaScript T7 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion). The DNA template was removed by DNase I, and RNA was purified by affinity chromatography with RNeasy columns (Qiagen, Germany) before spectrophotometric quantification. A competitive internal control was constructed by overlap extension PCR as described previously (10). The resulting construct contained a 350-bp fragment of the CCHF virus S segment and 70 bp of an unrelated sequence motif. It was cloned back into pCR 2.1 and transferred into RNA as described above.

RT-PCR.

A 50-μl reaction mixture contained 1× reaction buffer from a one-step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Germany), 200 μmol/liter deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 200 nM (each) primers as listed in Table 2, 2μl of one-step RT-PCR kit enzyme mix, and 5 μl of RNA extract. For subsequent hybridization to the macroarrays, a preformulated biotinylated primer mixture from a low-cost, low-density (LCD) array kit (Chipron GmbH, Germany) was used instead of the conventional primers. Amplification in a conventional PCR cycler (Primus 25; Peqlab, Germany) comprised 50°C for 30 min, 95°C for 15 min, and 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 60 s.

TABLE 2.

Primer and probe sequences used for RT-PCR and macroarray hybridization

| Name | Sequence | Position in CCHF virus strain 10200 (U88410) |

|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||

| CC1a_for | 5′-GTGCCACTGATGATGCACAAAAGGATTCCATCT | 210-242 |

| CC1b_for | 5′-GTGCCACTGATGATGCACAAAAGGATTCTATCT | 210-242 |

| CC1c_for | 5′-GTGCCACTGATGATGCACAAAAGGACTCCATCT | 210-242 |

| CC1a_rev | 5′-GTGTTTGCATTGACACGGAAACCTATGTC | 489-461 |

| CC1b_rev | 5′-GTGTTTGCATTGACACGGAAGCCTATGTC | 489-461 |

| CC1c_rev | 5′-GTGTTTGCATTGACACGGAAACCTATATC | 489-461 |

| Probes | ||

| CCHF-01 | 5′-CAACAGGCTGCTCTCAAGTGGAG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-02 | 5′-CCAGCAGGCTGCTCTCAAGTGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-03 | 5′-CCAACAAGCTGCCTTGAAATGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-04 | 5′-CCAACAGGCTGCCTTGAAATGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-05 | 5′-CCAACAGGCTGCTCTAAAGTGGAG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-06 | 5′-CCAACAAGCTGCCTTGAAGTGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-07 | 5′-CAGCAGGCTGCTCTCAAGTGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-08 | 5′-CAGCAGGCCGCTCTCAAGTG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-09 | 5′-CAACAGGCTGCTCTCAAATGGAG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-10 | 5′-CCAACATGCTGCTCTCAAGTGGA | 434-456 |

| CCHF-11 | 5′-AGCAAGCTGCCCTCAAGTGGA | 434-456 |

| CCHF-12 | 5′-TCAACAGGCTGCTCTAAAGTGGAGA | 434-456 |

| CCHF-13 | 5′-AGCAGGCAGCCCTCAAGTGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-14 | 5′-CAACAAGCCGCCTTAAAGTGGAG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-15 | 5′-CAACAAGCCGCCTTGAAGTGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-16 | 5′-CAACAGGCTGCCTTGAAGTGGA | 434-456 |

| CCHF-17 | 5′-CAACAGGCTGCTTTGAAATGGAG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-18 | 5′-CCAGCAGGCTGCTCTGAAGTG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-19 | 5′-CCAGCAGGCTGCTCTAAAGTGG | 434-456 |

| CCHF-20 | 5′-GCAGGCCGCCCTCAAGTG | 434-456 |

Array hybridization.

LCD DNA macroarrays are based on transparent, prestructured polymer supports containing eight identical arrays in well-separated, individually addressable hybridization fields (Fig. 1A). The outer dimensions of 50 by 50 mm allowed the use of economical transmission-light film scanners to generate images with 10-μm resolution for data analysis. Arrays were manufactured by Chipron GmbH using contact-free piezo dispensing technology. Capture probes were spotted in duplicates, leading to the formation of a nine-by-nine pattern, with average spot diameters of 325 μm (Fig. 1B). Twenty different CCHF virus-specific capture probes between 16 and 25 nucleotides (nt) in length were selected (Table 2). Each probe was designed to detect a broad range of sequence diversity at its binding site; i.e., probes were not designed for specificity but for breadth of detection. Four capture probes for the competitive internal control RT-PCR product were included in each array. Additional functional control probes with an unrelated sequence motif were placed in three corners of each field, in order to visualize successful hybridization and staining steps and to provide orientation marks for signal analysis. The hybridization of biotinylated RT-PCR products, labeling, and staining were done with the LCD array detection kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Chipron, Germany). In brief, 10-μl samples of the biotinylated RT-PCR products were combined with 24-μl volumes of a formamide-based hybridization buffer. These mixtures were applied to the individual fields of the macroarrays and hybridized for 30 min at 37°C in a standard incubator. Following a 2-min washing step in the supplied wash buffer (low stringency), the arrays were dried for 10 s by an airstream from a simple compressed-air can. Dried arrays were incubated for 5 min (room temperature) with the provided labeling solution (horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin conjugate). After a final wash-and-dry step (2 min, as noted above), 30 μl of the tetramethylbenzidine substrate was added to each field for staining (3 min at room temperature). The reaction was stopped by rinsing the chip in the last wash buffer for 10 s and then subjecting the chip to a drying step.

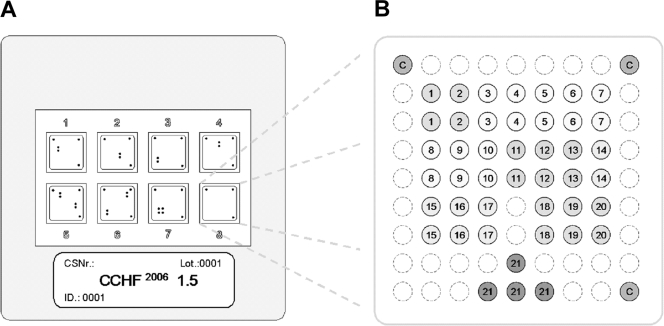

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the microarray. (A) Illustration of the 50- by 50-mm polymer support with the eight identical, individually addressable array fields. CSNr, chip specification number; ID, identification number. (B) Spotting pattern of one array field. Twenty CCHF virus-specific capture probes were spotted as vertical duplicates in a nine-by-nine pattern with average spot diameters of 325 μm (positions 1 to 20). Four capture probes for the competitive internal control RT-PCR product were included at the bottom of each array (positions 21). Additional functional control probes to visualize successful hybridization and staining were immobilized in three angles of each field (positions C).

Statistical analysis.

The Statgraphics Plus 5 software package (Umex, Germany) was used for all analyses. Probit analysis used as its input data set the cumulative hit rates in parallel reactions and their respective target RNA concentrations. It determined a continuous dose-response relationship (response rate of the assay dependent on the dose of RNA per reaction) with 95% confidence intervals (12).

RESULTS

The design of a novel broad-range CCHF virus RT-PCR was based on all 139 full or partial S gene sequences of CCHF virus available in GenBank by autumn 2007 (6, 7, 13). Three additional sequences from virus strains kept at several collaborating biosafety level 4 laboratories were determined de novo (25). Two conserved binding sites for primers, resulting in an RT-PCR amplicon of 280 bp, were identified. In designing these primers, primer 3′ ends at the third codon position were avoided. Degenerated (“wobble”) positions in primers were not used, in order to guarantee reliable resynthesis of primers. Instead, mismatched base pairings were adjusted by the mixing of defined oligonucleotides. The stable non-Watson-Crick base pairing T-G was not strictly adjusted for. For each of the two binding sites, three differential primers which covered, in summary, the observed range of sequence heterogeneity at the binding site were thus selected.

The assay was optimized for sensitivity by the titration of essential RT-PCR mix components. The assay amplified a broad range of CCHF virus strains (Table 1; data not shown). To determine the analytical sensitivity, RNAs from representative strains Bangui BT-958, Turkey 4348/02, and ArD39554 in limiting log10 dilution series were amplified. Viral loads down to 800, 1,000, and 780 genome copies per ml, respectively, could be detected.

To identify samples with RT-PCR inhibition, a synthetic internal control RNA was designed. To ensure amplification of the molecule without additional (possibly interfering) primers, an internal control that contained the same primer binding sites as CCHF virus (a competitive internal control) was chosen (10). To ensure that it did not outcompete even small amounts of virus RNA in the reaction mixture, the control was used at a low concentration (see below) and its length was extended over that of the virus, providing an inherent amplification disadvantage. The construct was 350 bp instead of 280 bp in length, through the insertion of a random sequence by overlap extension PCR.

Functionality was evaluated in cross-titration experiments with mixtures containing different amounts of CCHF virus RNA and internal control RNA. When CCHF virus RNA was absent, the internal control was amplified clearly (Fig. 2). In the presence of increasing concentrations of CCHF virus RNA, the level of amplification of the internal control was either lower or absent because of competitive inhibition by the amplification of the CCHF virus genomic target (Fig. 2). With increasing concentrations of the internal control in reaction mixtures containing constantly low levels of CCHF virus RNA (60 copies per reaction), it was demonstrated that no inhibition of virus amplification was imposed by competitive effects of the internal control. A working concentration of 200 copies of the internal control per reaction was chosen for all further assays.

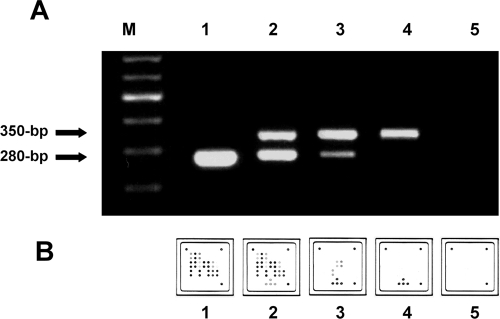

FIG. 2.

RT-PCR amplification with the CCHF virus-specific assay (280-bp amplicon) and the internal control (350-bp amplicon). (A) Conventional 1.5% agarose gel analysis of the RT-PCR products. (B) Specific hybridization patterns of the same RT-PCR products on the macroarray. Lane M, 100-bp molecular size ladder; lanes/fields 1 to 3, CCHF virus strain BT-958 in vitro-transcribed RNA; lane/field 1, 6 × 106 genome copies per reaction; lane/field 2, 6 × 104 copies per reaction; lane/field 3, 6 copies per reaction; lane/field 4, internal control RNA only; lane/field 5, control to which no RNA was added. Note that both analysis methods visualize the suppression of the internal control amplification by increasing concentrations of CCHF virus target RNA.

Primers were then used to produce ready-made reaction mixtures containing proprietary modifications which allowed the hybridization of amplification products to LCD arrays. The limit of modified RT-PCR was analyzed by testing a series of human sera spiked with synthetic full-length S segment RNA at concentrations from 100,000 to 10 copies per ml. For each concentration step, five replicate test reactions were conducted and the results were subjected to probit analysis. Statistically constant detection could be achieved with as little as 10 copies of RNA per reaction (data not shown). Sporadic detection was possible down to a single copy per reaction. Probit analysis determined a 95% detection limit of 540 copies per ml of serum, corresponding to 6.3 genome copies per reaction (95% confidence interval, 4.3 to 14.3 copies per assay; P = 0.05).

Hybridization to LCD arrays was evaluated next. All 18 virus reference strains listed in Table 1 were amplified and hybridized (Fig. 3). Signals after the hybridization and staining procedures were clearly visible to the naked eye. Repeated testing of a virus sample showed constantly identical hybridization patterns (data not shown). The whole protocol took less than 4 h, and up to 48 samples could easily be analyzed in parallel. Documentation images as shown in Fig. 3 were obtained using a standard slide scanner purchased from a department store. Array hybridization provided the same sensitivity as gel detection, as shown in Fig. 2. However, at virus concentrations below 1,000 copies per reaction, some of the capture probes which generated only weak hybridization signals at higher template concentrations were not visible. This result may limit the ability to discriminate among certain CCHF virus strains in samples with very low viral loads.

The specificity of the RT-PCR assay was verified using purified genomic nucleic acids from culture supernatant or high-titered patient samples containing pathogens that cause diseases resembling CCHF infections: Bacillus anthracis, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Coxiella burnetii, cytomegalovirus, dengue virus types 1 to 4, Dugbe virus, Ebola virus strain Gulu, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis C virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, Lassa virus strain AV, Leptospira interrogans, Listeria monocytogenes, monkeypox virus, Neisseria meningitidis, Plasmodium falciparum, poliomyelitis virus types 1, 2, and 3, rabies virus, Rickettsia prowazekii, Rickettsia rickettsii, Rift Valley fever virus, Ross River virus, Sindbis virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, West Nile virus strain Uganda, and yellow fever virus. None of these materials, including Dugbe virus (strain AF014014), a nonpathogenic nairovirus related to CCHF virus, showed any reactivity. None of the assays with these pathogens showed any random reactivity, i.e., additional nonspecific bands in gel electrophoresis or background hybridization (data not shown).

Clinical application.

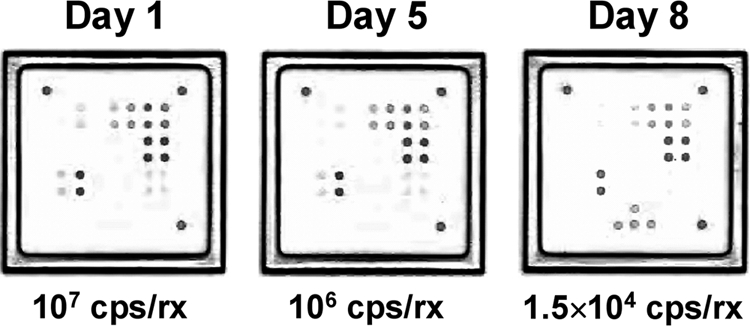

A total of 63 serum samples from 31 patients with confirmed CCHF, received from 1986 to 2006, were tested after they had been stored at −70°C for up to 20 years. Of the 31 confirmed cases of CCHF included in the study, 27 occurred in widely separated locations in South Africa and Namibia, 3 occurred in Iran, and 1 occurred in Pakistan. Serum had been collected 1 to 18 days (mean, 6 days; SD, 2.8 days) after the onset of disease. Viral loads of the stored samples were quantified by real-time RT-PCR (25) and ranged from 1.6 × 103 to 5 × 108 genome copies per ml (mean, 106 genome copies per ml; SD, 20 genome copies per ml). All samples were positive in all assays. Serial samples from the same patients showed identical hybridization patterns (Fig. 4). All tested clinical samples from different regions where CCHF is endemic could be distinguished on the basis of their hybridization patterns (compare Fig. 3A and B).

FIG. 4.

Serial samples from a patient with an acute case of CCHF. This example shows hybridization patterns obtained from serum samples on days 1, 5, and 8 after the onset of the disease. The viral loads of the samples (in genome copies per reaction [cps/rx]) were quantified by real-time RT-PCR as described before (25).

A panel of 128 serum samples collected from healthy individuals was also used as negative controls. All negative samples showed amplification of the internal control but no CCHF virus-specific signal in the hybridization assay (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The remarkable genetic variability of all known CCHF virus isolates involves a risk of human infection by divergent strains which current protocols may not detect. At the same time, even very simple versions of current assays may fail in basic laboratory settings typically encountered in countries were CCHF is endemic. Compared to current molecular assays such as nested RT-PCR or real-time RT-PCR, the identification of the amplicons by hybridization to up to 20 different capture probes gives additional sequence verification. This approach is more reliable than real-time RT-PCR for new virus strains, which may not have conserved sequences at the binding site of a single hybridization probe. The assay does not depend on expensive lab infrastructure, and therefore, it can be applied more easily in basic laboratory settings or in the field. The use of an array of short DNA capture probes (16 to 25 nt in length) gives basic genotyping capacity, even though it may not be sufficient for the final characterization of CCHF virus strains, especially those in samples with low viral loads (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, preliminary genotyping can be very helpful in a diagnostic situation when possible PCR contamination has to be ruled out, as a real positive reaction in most cases will provide a hybridization pattern different from the positive control. The assay provides an economical, rapid, and convenient method to identify CCHF virus in acute-phase human serum samples without requiring sophisticated equipment. It may prove useful for the clinical diagnosis and surveillance of CCHF under basic laboratory conditions in developing countries or in outbreak investigations.

Acknowledgments

The research described herein is part of the Medical Biological Defense Research Program of the Bundeswehr Joint Medical Service. It was sponsored in part by the European Union Framework Program 6 (EU FP6), “Viral Haemorrhagic Fevers/Variola-PCR.”

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by any governmental agency or department or other institutions.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alavi-Naini, R., A. Moghtaderi, H. R. Koohpayeh, B. Sharifi-Mood, M. Naderi, M. Metanat, and M. Izadi. 2006. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in southeast of Iran. J. Infect. 52378-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burt, F. J., P. A. Leman, J. C. Abbott, and R. Swanepoel. 1994. Serodiagnosis of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. Epidemiol. Infect. 113551-562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt, F. J., P. A. Leman, J. F. Smith, and R. Swanepoel. 1998. The use of a reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction for the detection of viral nucleic acid in the diagnosis of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever. J. Virol. Methods 70129-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burt, F. J., R. Swanepoel, and L. E. Braack. 1993. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for the detection of antibody to Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus in the sera of livestock and wild vertebrates. Epidemiol. Infect. 111547-557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casals, J., and G. H. Tignor. 1974. Neutralization and hemagglutination-inhibition tests with Crimean hemorrhagic fever-Congo virus. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 145960-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chamberlain, J., N. Cook, G. Lloyd, V. Mioulet, H. Tolley, and R. Hewson. 2005. Co-evolutionary patterns of variation in small and large RNA segments of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus. J. Gen. Virol. 863337-3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deyde, V. M., M. L. Khristova, P. E. Rollin, T. G. Ksiazek, and S. T. Nichol. 2006. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus genomics and global diversity. J. Virol. 808834-8842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drosten, C., S. Gottig, S. Schilling, M. Asper, M. Panning, H. Schmitz, and S. Gunther. 2002. Rapid detection and quantification of RNA of Ebola and Marburg viruses, Lassa virus, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus, Rift Valley fever virus, dengue virus, and yellow fever virus by real-time reverse transcription-PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 402323-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drosten, C., D. Minnak, P. Emmerich, H. Schmitz, and T. Reinicke. 2002. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Kosovo. J. Clin. Microbiol. 401122-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drosten, C., M. Weber, E. Seifried, and W. K. Roth. 2000. Evaluation of a new PCR assay with competitive internal control sequence for blood donor screening. Transfusion 40718-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duh, D., A. Saksida, M. Petrovec, I. Dedushaj, and T. Avsic-Zupanc. 2006. Novel one-step real-time RT-PCR assay for rapid and specific diagnosis of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever encountered in the Balkans. J. Virol. Methods 133175-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink, H., and G. Hund. 1965. Probit analysis with programmed computers. Arzneimittel-Forschung 15624-630. (In German.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hewson, R., J. Chamberlain, V. Mioulet, G. Lloyd, B. Jamil, R. Hasan, A. Gmyl, L. Gmyl, S. E. Smirnova, A. Lukashev, G. Karganova, and C. Clegg. 2004. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus: sequence analysis of the small RNA segments from a collection of viruses world wide. Virus Res. 102185-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoogstraal, H. 1979. The epidemiology of tick-borne Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Asia, Europe, and Africa. J. Med. Entomol. 15307-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamil, B., R. S. Hasan, A. R. Sarwari, J. Burton, R. Hewson, and C. Clegg. 2005. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: experience at a tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99577-584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karti, S. S., Z. Odabasi, V. Korten, M. Yilmaz, M. Sonmez, R. Caylan, E. Akdogan, N. Eren, I. Koksal, E. Ovali, B. R. Erickson, M. J. Vincent, S. T. Nichol, J. A. Comer, P. E. Rollin, and T. G. Ksiazek. 2004. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 101379-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papa, A., S. Bino, A. Llagami, B. Brahimaj, E. Papadimitriou, V. Pavlidou, E. Velo, G. Cahani, M. Hajdini, A. Pilaca, A. Harxhi, and A. Antoniadis. 2002. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Albania, 2001. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21603-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papa, A., I. Christova, E. Papadimitriou, and A. Antoniadis. 2004. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Bulgaria. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 101465-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez, L. L., G. O. Maupin, T. G. Ksiazek, P. E. Rollin, A. S. Khan, T. F. Schwarz, R. S. Lofts, J. F. Smith, A. M. Noor, C. J. Peters, and S. T. Nichol. 1997. Molecular investigation of a multisource outbreak of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in the United Arab Emirates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57512-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwarz, T. F., H. Nitschko, G. Jager, H. Nsanze, M. Longson, R. N. Pugh, and A. K. Abraham. 1995. Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in Oman. Lancet 3461230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz, T. F., H. Nsanze, and A. M. Ameen. 1997. Clinical features of Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever in the United Arab Emirates. Infection 25364-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swanepoel, R., D. E. Gill, A. J. Shepherd, P. A. Leman, J. H. Mynhardt, and S. Harvey. 1989. The clinical pathology of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl. 4)S794-S800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanepoel, R., J. K. Struthers, A. J. Shepherd, G. M. McGillivray, M. J. Nel, and P. G. Jupp. 1983. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in South Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 321407-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitehouse, C. A. 2004. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever. Antivir. Res. 64145-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfel, R., J. T. Paweska, N. Petersen, A. A. Grobbelaar, P. A. Leman, R. Hewson, M. C. Georges-Courbot, A. Papa, S. Gunther, and C. Drosten. 2007. Virus detection and monitoring of viral load in Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus patients. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 131097-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yapar, M., H. Aydogan, A. Pahsa, B. A. Besirbellioglu, H. Bodur, A. C. Basustaoglu, C. Guney, I. Y. Avci, K. Sener, M. H. Setteh, and A. Kubar. 2005. Rapid and quantitative detection of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus by one-step real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 58358-362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]