Abstract

Lipooligosaccharides (LOS) are highly antigenic glycolipids produced by a number of Mycobacterium species, which include “M. canettii,” a member of the M. tuberculosis complex, and the opportunistic pathogens M. marinum and M. kansasii. The various LOS share a core composed of trehalose esterified by at least 1 mole of polymethyl-branched fatty acid (PMB-FA) and differ from one another by their oligosaccharide extensions. In this study, we identified a cluster of genes, MSMEG_4727 through MSMEG_4741, likely involved in the synthesis of LOS in M. smegmatis. Disruption of MSMEG_4727 (the ortholog of pks5 of M. tuberculosis), which encodes a putative polyketide synthase, resulted in the concomitant abrogation of the production of both PMB-FA and LOS in the mutant strain. Complementation of the mutant with the wild-type gene fully restored the phenotype. We also showed that, in contrast to the case for “M. canettii” and M. marinum, LOS are located in deeper compartments of the cell envelope of M. smegmatis. The availability of two mycobacterial strains differing only in LOS production should help in defining the biological role(s) of this important glycolipid.

Within the high-G+C gram-positive Actinobacteria division, the genus Mycobacterium belongs to the suborder of Corynebacterineae, a taxon characterized by a multilayered cell envelope extremely rich in unusual lipids. M. tuberculosis is a well-adapted and very successful human pathogen, infecting one-third of the world's population (estimated up to 2 billion people) and killing a person every 10 seconds (15). In addition, nearly two-thirds of the 135 described species were reported as human or animal pathogens (37), an observation assumed to be related to the very unusual envelope of mycobacteria, one of the most impenetrable in the living word (23). This coat confers to mycobacteria a remarkable passive resistance to antibiotics, antiseptics, or disinfectants and to the bactericidal properties of phagocytic cells (11, 24). Furthermore, various lipidic components of this envelope are known to modulate the host immune system and phagocytic cell functions (1, 47).

The mycobacterial cell envelope is composed of two kinds of lipids: (i) the cell wall-bound mycolic acids, which are very-long-chain fatty acids that contribute in a large part to the cell impermeability (23), and (ii) the so-called free lipids, which originate from the plasma membrane, the outer mycomembrane, and the capsule (11) and are extractable with organic solvents. These include the ubiquitous trehalose dimycolate and phosphatidylinositol mannosides (PIM) (1, 11, 47) and the species- or type-specific lipids with a more restricted distribution, such as the sulfolipids (11), phenolglycolipids (12, 21, 31), and phthiocerol dimycocerosates (21, 31) of M. tuberculosis and the glycopeptidolipids (GPL) (1, 12, 14) and lipooligosaccharides (LOS) (12) of M. avium and M. smegmatis.

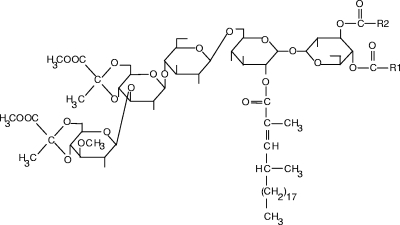

LOS are highly antigenic glycoconjugates that are exposed at the cell surface of the mycobacterial species that produce them (3, 34), but their precise role in mycobacterial virulence as well as in the colony morphotype is still a matter of debate (3, 30). Nevertheless it has been recently shown that they play an undoubted role in sliding motility, biofilm formation, and infection of murine macrophage-like cells by M. marinum (40). LOS were found first in M. kansasii (22) and M. smegmatis (43) and then in nine other mycobacterial species (12, 40), which include “M. canettii” and related strains (13), a deeply branched lineage of the M. tuberculosis complex (6). LOS (Fig. 1) share a poly-O-acylated trehalose core further glycosylated by a monosaccharidyl unit or, more frequently, an oligosaccharidyl unit (12). An additional feature is that in LOS, trehalose is invariably acylated by polymethyl-branched fatty acids (PMB-FA), a singularity shared with other trehalose-based mycobacterial glycolipids such as sulfolipids and di- or triacyltrehaloses (31). While PMB-FA could be either saturated, e.g., in “M. canettii,” or unsaturated, e.g., in M. smegmatis, their synthesis invariably requires a particular polyketide synthase (Pks) of the Mas type (for mycocerosic acid synthase) (21, 31). This type of Pks uses methylmalonyl-coenzyme A (methylmalonyl-CoA) units as elongation units instead of malonyl-CoA, resulting in the formation of a polymethyl-branched aliphatic chain (50). LOS certainly remain among the less well-known mycobacterial glycolipids (12). Their biosynthetic pathway is still poorly understood, with only three genes experimentally demonstrated to be involved in the late steps of LOS biosynthesis (7, 40). In the present work we identified a cluster of 15 genes in the genome of M. smegmatis; this cluster includes MSMEG_4727 (the ortholog of pks5 of M. tuberculosis), which encodes a putative Mas-type Pks. Disruption of the pks5-orthologous gene of M. smegmatis abolished the production of both PMB-FA and LOS in the wild-type stain ATCC 607.

FIG. 1.

Structure of major LOS (LOS-A) of M. smegmatis ATCC 356 (25). R1 and R2, octanoic acid and tetra- or hexadecanoic acid.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and medium.

Escherichia coli DH5α, used to propagate plasmids, and M. smegmatis strains were grown in LB medium (Invitrogen). When required, antibiotics and sucrose were added to the medium at the following concentrations: kanamycin (Km), 25 μg·ml−1; hygromycin (Hyg), 100 μg·ml−1 or 200 μg·ml−1 for M. smegmatis and E. coli, respectively; and sucrose, 2%.

General DNA techniques.

Molecular cloning and restriction endonuclease digestions were performed by standard procedures. Mycobacterial genomic DNA was isolated from 5-ml saturated cultures according to published methods (4).

Construction of an MSMEG_4727-disrupted mutant of M. smegmatis ATCC 607.

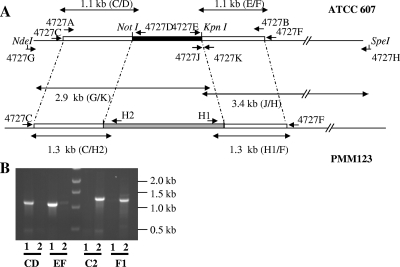

A mutant of M. smegmatis ATCC 607 containing a disrupted MSMEG_4727::hyg gene on the chromosome was constructed by allelic exchange using the ts/sacB procedure (35). A 3,086-bp DNA fragment internal to the MSMEG_4727 gene (6,336 bp in length) was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using oligonucleotides 4727A and 4727B, which contain a PmeI restriction site (Fig. 2A; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Primers 4727A and 4727B were located 682 bp and 3,759 bp, respectively, after the start codon. This fragment was cloned into the Escherichia coli pGEM-T vector (Promega), and an Hyg resistance cassette was inserted between the NotI and KpnI restriction sites (located 1,696 bp and 2,770 bp after the start codon of MSMEG_4727). A PmeI fragment carrying the substrate for the allelic exchange was then transferred into the XbaI site (made blunt with T4 DNA polymerase) of the mycobacterial thermosensitive plasmid pPR23 (35), resulting in pWM77. As M. smegmatis ATCC 607 displays a low frequency of transformation (44), mutants bearing the allelic exchange event at the MSMEG_4727 locus were constructed in two steps. First, the pWM77 plasmid was transferred by electrotransformation into M. smegmatis ATCC 607, and clones expressing the plasmid were selected on 100-μg·ml−1 Hyg at the permissive temperature (32°C). One of these clones was then propagated, and colonies in which the allelic exchange event occurred were subsequently selected on Hyg- and sucrose-containing medium incubated at the nonpermissive temperature (42°C). Several colonies were screened by PCR analysis of the genomic DNA using a set of specific primers (4727C and 4727D or 4727H2; 4727F and 4727E or 4727H1 [Fig. 2A; see Table S1 in the supplemental material]). One clone with a pattern corresponding to the disruption of MSMEG_4727 was selected and named PMM123 (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Construction, characterization, and complementation of the M. smegmatis ATCC 607 MSMEG_4727::hyg mutant strain (PMM123). (A) Schematic diagram of the MSMEG_4727 gene in the wild-type strain ATCC 607 (top) and the PMM123 mutant (bottom). The white box represents the region of the MSMEG_4727 wild-type allele targeted by allelic exchange, the black box the fragment deleted in this gene, and the gray box the Hyg resistance cassette used for the disruption. The positions of the primers are indicated by arrows, and the expected size for each PCR products is shown. (B) PCR analysis of the wild-type strain (lanes 1) and mutant strain PMM123 (lanes 2) using the following combinations of specific primers: CD, 4727C/4727D; EF, 4727E/4727F; C2, 4727C/H2; F1, 4727F/H1.

Complementation study.

To construct pWM96 for the complementation of the MSMEG_4727 mutant strain, the wild-type MSMEG_4727 gene from M. smegmatis ATCC 607 was amplified by PCR using chromosomal DNA as a template and two sets of primers. First, a 2.9-kbp fragment was amplified using primers 4727G and 4727K and cloned into pGEM-T, resulting in pWM82 (Fig. 2A; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Second, a 3.4-kbp fragment was amplified using primers 4727H and 4727J and cloned into pGEM-T, resulting in pWM83 (Fig. 2A; see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The two fragments were then recombined by cloning the KpnI/SpeI fragment of pWM83 between the KpnI and SpeI restriction sites of pWM82. The integrity of the MSMEG_4727 gene was checked by sequencing. The resulting MSMEG_4727 gene product was digested with NdeI and SpeI and inserted between the NdeI and SpeI sites of a derivative of the integrative plasmid pMV361 carrying the pBlaF* promoter from pMIP12 (29) and a Km resistance marker (29, 46). In this vector the expression of the MSMEG_4727 gene is under the control of the pBlaF* promoter. This vector was transferred into PMM123 cells, and the transformants were selected on Km.

Extraction and purification of mycobacterial lipids.

The total lipid fraction was extracted from cell pellets with a mixture of chloroform and methanol as previously described (48). The cellular and surface-exposed lipids were prepared as previously described (17). Briefly, the mycobacterial cell pellet was shaken for 1 min with 10 g glass beads (4-mm diameter) per 2 g (wet weight) cells and resuspended in distilled water, and the resulting extracellular materials were separated from the cells by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 10 min). The cellular lipid fraction and the surface-exposed lipids were then extracted from the pellet and the supernatant, respectively, with a mixture of chloroform and methanol. Methanol-soluble lipids were prepared as previously described (48). The various lipid extracts (250 μg each deposit, except when indicated) were analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on silica gel Durasil 25-precoated plates (0.25-mm thickness; Macheray-Nagel). LOS were resolved by TLC run in chloroform-methanol (90:10, vol/vol) or chloroform-methanol-water (60:16:2, vol/vol) and visualized by spraying the plates with 0.2% anthrone in concentrated sulfuric acid, followed by heating at 110°C. Other lipids were analyzed and identified by TLC as previously described, using standard controls (17). Purification of LOS was achieved by preparative TLC in which plates were developed as described above, and then LOS-containing silica bands were scraped and extracted three times with the same solvent.

Production of FAME.

The total lipid fraction and the purified LOS were de-O-acylated with 0.1 N NaOH in chloroform-methanol (50:50, vol/vol) for 60 min at 110°C. The hydrolysates were dried under a stream of N2 and solubilized in acidic chloroform, and the fatty acids were extracted five times with diethyl ether. The pooled ethereal phases were extensively washed with water and then dried under vacuum. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) were obtained by methylating the extracted fatty acids with an ethereal solution of diazomethane (28).

Analytical procedures.

Lipids were analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) as previously described (28, 45). One-dimensional 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AMX-500 spectrometer using standard pulse sequences available in the Bruker software. The chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm) relative to acetone as an internal standard (δH 2.22). Gas chromatography/MS (GC/MS) analysis of PMB-FA methyl esters was performed on a Hewlett-Packard 5890 series II gas chromatograph fitted with an OV1 fused-silica capillary column (12 m by 0.30 mm) and connected to a Hewlett-Packard 5989X mass spectrometer in electron impact mode with an ionization potential of 70 eV. The temperature program used was 100°C (delay of 3 min) to 290°C at 8°C/min.

Phenotypic tests.

Sliding motility, Congo red binding, hydrophobic index, and adhesion on PVC were assessed as previously described (16, 17, 39). Briefly, sliding motility was measured on semisolid 7H9 agar (0.3%) without any carbon source. Congo red accumulation was determined by cultivating mycobacteria for 3 days in LB broth plus 100 mg·ml−1 Congo red. After washing, the dye that remained associated with the cells was extracted with acetone, and the Congo red binding index was defined as the A488 of the acetone extract divided by the dry weight of the cell pellet. The relative cellular hydrophobicity was assessed by the hexadecane partition procedure: a single-cell suspension of each strain (optical density at 650 nm of 1) was mixed with 0.3 ml hexadecane, and the hydrophobicity index was defined as the percent reduction in the optical density at 650 nm of the aqueous phase after complete separation of the two phases. Cell adhesion on PVC petri dishes containing phosphate-buffered saline was detected by crystal violet (1%) staining after a 16-h incubation at 37°C and quantified by counting the number of adherent cells per microscopic field. MICs were determined by the agar twofold dilution method in Trypticase soy agar (bioMérieux). The drug-containing media were inoculated with about 105 CFU and incubated for 5 days at 37°C.

RESULTS

Identification of a cluster of genes putatively involved in the LOS biosynthetic pathway.

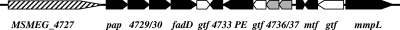

A survey of the recently reannotated genome of M. smegmatis in the TIGR-CMR database (http://cmr.tigr.org/tigr-scripts/CMR/GenomePage.cgi?database=gms) revealed the occurrence of six genes that putatively encode modular Pks (Table 1), a number considerably lower than that in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (21). We have previously assigned the functions of two of them, namely, MSMEG_0408 (Pks1), which is involved in GPL biosynthesis (45), and MSMEG_6392 (Pks13), which catalyzes the last condensation step of mycolic acid biosynthesis (36). MSMEG_4512 (MbtD) and MSMEG_4513 are postulated to participate in the synthesis of the mycobactin siderophore. The MSMEG_4727 gene is located in a region whose genomic environment suggests that it could be implicated in glycolipid biosynthesis (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Indeed, the fatty acid synthesis and attachment of the lipid moiety of glycolipids in mycobacteria generally require the concerted action of the products of genes such as pap and fadD (21, 41), members of both families being in the vicinity of MSMEG_4727. Similarly, the mmpL gene located at the 3′ end of the cluster putatively encodes a transmembrane protein belonging to the mycobacterial membrane protein large (MmpL) family, whose members were previously shown to be involved in the transport and eventually the biogenesis of mycobacterial lipids (8, 10).

TABLE 1.

pks/mas genes present in the M. smegmatis genome

| Locus | Gene name | Annotation | Metabolite synthesized | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSMEG_0408 | pks1 | Polyketide synthase | GPLa | 45 |

| MSMEG_4512 | mbtD | Polyketide synthase | Mycobactinsb | TIGR site |

| MSMEG_4513 | Polyketide synthase | Mycobactinsb | TIGR site | |

| MSMEG_4727 | pks5 | Mas-like Pks | LOSa | This work |

| MSMEG_6392 | pks13 | Condensase | Mycolic acidsa | 36 |

| MSMEG_6767 | mas | Mas-like Pks | ? |

Experimentally identified.

Putative.

TABLE 2.

ORFs of the pks5 cluster

| ORF | Gene name | No. of amino acids in product | Proposed function of product | Sequence similarity or protein familya | Identity/similarity (%) or HMM scoreb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSMEG_4727 | pks5 | 2,111 | Polyketide synthase (mas-like) | Rv1527c, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 66/78 |

| MSMEG_4728 | pap | 480 | Polyketide synthase-associated protein | Rv1528c, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 61/78 |

| MSMEG_4729 | 487 | Conserved hypothetical protein, possible acyltransferase | Mmcs_3117, Mycobacterium sp. strain MCS | 56/68 | |

| MSMEG_4730 | 468 | Conserved hypothetical protein, possible acyltransferase | Mmcs_3117, Mycobacterium sp. strain MCS | 49/61 | |

| MSMEG_4731 | fadD | 577 | Acetoacetyl-CoA synthase | Rv1521, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 57/72 |

| MSMEG_4732 | gtf | 276 | Glycosyltransferase (CAZy family GT2) | alr4493, Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5 | 27/45 |

| MSMEG_4733 | gap2 | 256 | Transmembrane protein, glycolipid translocation | Rv1517, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 38/53 |

| MSMEG_4734 | 621 | Hypothetical protein, PE-PPE-like | Mmcs_4281, Mycobacterium sp. strain MCS | 41/52 | |

| MSMEG_4735 | gtf | 294 | Possible glycosyltransferase | Galactosyltransferase PssJ, Rhizobium leguminosarum | 36/48 |

| MSMEG_4736 | 295 | Pyruvyltransferase | PF04230, polysaccharide pyruvyltransferase | −27.4 | |

| MSMEG_4737 | 296 | Pyruvyltransferase | PF04230, polysaccharide pyruvyltransferase | −13.5 | |

| MSMEG_4738 | 190 | Hypothetical protein | |||

| MSMEG_4739 | mtf | 226 | Possible O-methyltransferase | MAV_3257, M. avium 104 | 50/63 |

| MSMEG_4740 | gtf | 488 | Glycosyltransferase (CAZy family GT1) | Rv1524/Rv1526c, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 51/61-48/58 |

| MSMEG_4741 | mmpL | 1,017 | Polyketide synthase-associated protein | Rv1522c, M. tuberculosis H37Rv | 45/62 |

PF numbers indicate protein families.

Negative numbers are hidden Markov model (HMM) scores.

FIG. 3.

Genomic organization of the M. smegmatis chromosome region postulated to encode the proteins involved in LOS biosynthesis. ORFs are depicted as arrows and are drawn proportionally to their sizes. Gene names are indicated below: gtf, putative glycosyl transferase ORF (white); MSMEG_4736 and MSMEG_4737, putative pyruvyltransferase ORFs (gray).

MSMEG_4727, whose sequence is 65.6% identical to that of M. tuberculosis Mas-like Rv1527c (Pks5) (Table 2), is predicted to belong to the Mas subtype of Pks, which synthesizes PMB-FA. Examination of the peptide sequence of the putative protein using the SEARCHPKS program (49) (http://linux1.nii.res.in/∼pksdb/DBASE/pagesearchpks.html) confirmed this annotation, with the predicted extender unit and the product of MSMEG_4727 being methylmalonate and PMB-FA, respectively (49, 50). To the best of our knowledge, the only type of PMB-FA-acylated glycolipids produced by M. smegmatis is LOS (25, 43). In addition, the M. smegmatis LOS exhibit the unique characteristic among the mycobacterial lipids of being pyruvylated (5, 43) (Fig. 1), which is in agreement with the occurrence in the cluster of two genes tentatively identified as polysaccharide pyruvyltransferase (Table 2). Moreover, the fact that the M. smegmatis LOS are composed of, in addition to trehalose, three glucosyl residues, one of them being mono-O-methylated (Fig. 1), perfectly matched with the identification in the vicinity of MSMEG_4727 of genes encoding one possible O-methyltransferase (32 and 26% sequence identity with the putative mycobacterial O-methyltransferases MSMEG_5003 and Rv0187, respectively) and three putative glycosyltransferases (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Although the three putative glycosyltransferases share no significant homology, MSMEG_4740 (glycosyltransferase family protein 28) displays 50% sequence identity with each of the three glycosyltransferases identified in the GPL biosynthesis locus, MSMEG_0385, MSMEG_0389, and MSMEG_0392. Taken together, these observations strongly suggested that the cluster of genes downstream of the MSMEG_4727 locus is dedicated to the synthesis of LOS in M. smegmatis, although the role of these genes remained to be experimentally established.

Disruption of the MSMEG_4727 gene in M. smegmatis ATCC 607.

Due to the fact that mc2155 is virtually devoid of LOS, the ATCC 607 strain, which is known to produce this glycoconjugate (16), was preferred to the former strain of M. smegmatis to determine whether the MSMEG_4727 protein is involved in LOS biosynthesis. In addition, the ATCC 607 strain, at least for one of its variants (27), had the advantage of producing a very low level of GPL. Indeed, GPL share with LOS a number of physicochemical properties that could make their discrimination very laborious (16). However, the ATCC 607 strain displays a very low level of transformability (44), a feature that made necessary the construction of the disrupted mutant (Fig. 2A) in two steps (see Materials and Methods). Briefly, a 3,086-bp fragment starting 682 bp after the start codon and ending 2577 bp before the stop codon of MSGMEG_4727 was amplified by PCR. A Hyg resistance cassette was inserted between the NotI and KpnI restriction sites of this fragment (generating a 1,084-bp deletion), which was then transferred into the pPR23 thermosensitive mycobacterial vector. The resulting plasmid, named pWM77, was transferred by electroporation into the ATCC 607 strain, and transformants were selected at 32°C on LB agar plates containing Hyg. One transformant was picked up and grown for 4 days at 32°C in LB liquid medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 and Hyg. The culture was plated on LB agar containing both Hyg and sucrose (10%) and incubated at 42°C. Of the 10 clones analyzed by PCR, 5 exhibited an amplification pattern consistent with an allelic exchange at the MSMEG_4727 locus (Fig. 2B). One clone, named PMM123, was retained for further analysis.

Analysis of the PMB-FA content of the MSMEG_4727::hyg mutant strain.

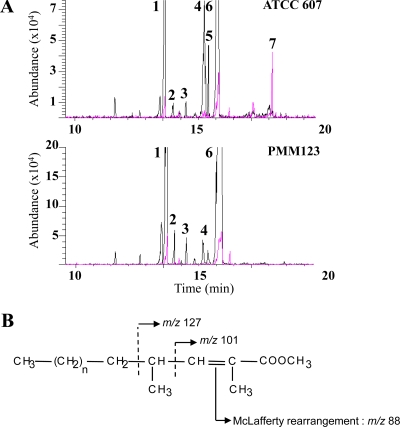

In M. smegmatis, LOS are acylated by an unsaturated PMB-FA, the 2,4-dimethyl-2-eicosenoic acid (25). To determine whether or not the MSMEG_4727 gene is involved in the biosynthesis of this polyketide, we comparatively analyzed the fatty acid contents of the ATCC 607 and PMM123 strains. The total lipid fraction from each strain was saponified and methylated, and the resulting FAME were analyzed by GC/MS. Chromatograms of the extracted ion at m/z 74, which originated from the McLafferty rearrangement of non-methyl-branched FAME (32), showed that the major FAME produced by both the wild-type and the mutant strains of M. smegmatis were, based on their retention times and molecular masses, the C16, C18:1, C18, and C19 (tuberculostearic) methyl esters (Fig. 4A). The chromatogram of the extracted ion at m/z 88, the McLafferty rearrangement of a 2-methyl-branched FAME (Fig. 4B) (2), of the lipid extract from the wild-type strain showed a major peak that was absent from the mutant strain (Fig. 4A, peak 7). The molecular mass of the eluted compound observed at m/z 352 was in agreement with an unsaturated C24 FAME. Its fragmentation pattern showed, in addition to the fragment-ion at m/z 88, peaks at m/z 101 and 127 that are characteristic of a 2-unsaturated and 4-methyl-branched FAME, respectively (Fig. 4B) (2, 32). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that the 2,4-dimethyl-2-eicosenoic acid was the polyketide whose synthesis was achieved by the MSMEG_4727 Pks.

FIG. 4.

GC/MS analysis of the FAME of MSMEG_4727::hyg mutant strain PMM123. (A) Extracted ion chromatograms of the fatty acids produced by the wild-type ATCC 607 strain and the mutant PMM123 strain: m/z 74 for the FAME (black line) and m/z 88 for the methyl-branched FAME (pink line). The major peaks are C16 (peak 1), 10-methyl-C16 (peak 2), C17 (peak 3), C18:1 (peak 4), C18 (peak 5), and 10-methyl-C18 (peak 6) fatty acid methyl esters and 2,4-dimethyl-2-eicosenoic acid (peak 7) methyl ester. (B) Characteristic major fragments of PMB-FA methyl esters occurring during MS (electron impact ionization) analysis.

Analysis of the LOS content of the MSMEG_4727::hyg mutant strain.

To check whether the disruption of the MSMEG_4727 gene affects the glycolipid profile of the mutant strain, the whole lipids of the wild-type and mutant strains were extracted, partitioned by methanol precipitation, and analyzed by TLC (Fig. 5A). One compound was clearly absent from the mutant strain, whose Rf and appearance upon anthrone revelation suggested that it could correspond to LOS and, more precisely, to the dipyruvylated LOS-A form (5, 16). Two minor bands of lower motility, both absent from the mutant lipid extract, could be related to the more polar monopyruvylated LOS-B1 and LOS-B2 (43). Importantly, the production of the three LOS-like compounds was restored in the complemented strain, although at a lower level (Fig. 5A, lane 3). The contents lipid of other lipids, e.g., trehalose mono- and dimycolate and phospholipids (phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, and PIM), in the wild-type and mutant strains were comparable (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). The synthesis of a few lipids (PIM2 and phosphatidylglycerol) which seemed to be produced in smaller amounts by the mutant strain was restored at a normal level in the complemented strain (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

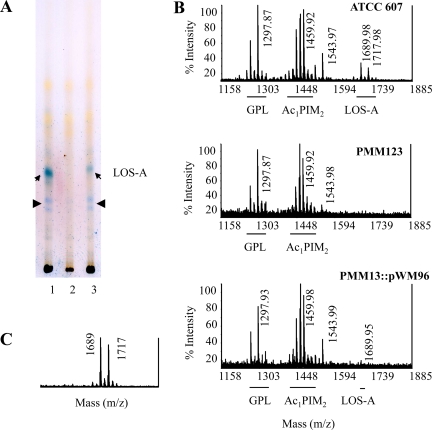

FIG. 5.

TLC and MALDI-TOF MS analysis of the MSMEG_4727::hyg PMM123 mutant strain. (A) TLC analysis (CHCl3-CH3OH, 90:10) of lipid extracts of M. smegmatis wild-type strain ATCC 607 (lane 1), strain PMM123 (lane 2), and the complemented PMM123::pWM96 strain (line 3). Methanol-soluble glycolipids, extracted from exponentially grown cultures of M. smegmatis strains, were visualized by spraying with anthrone, followed by charring. Positions of LOS-A are indicated (arrows), as are the locations of the putative LOS-B (arrowheads). The contrast of this image was improved with image processing software. (B) MALDI-TOF MS of the crude lipid extracts of the wild-type, mutant PMM123, and complemented PMM123::pWM96 strains. Major pseudomolecular ion [M + Na]+ peaks of GPL, phosphoinositolmannosides (Ac1PIM2), and LOS-A are indicated below the spectra. (C) MALDI-TOF MS of the LOS-A purified from the complemented PMM123::pWM96 strain.

Further identification of the main compound absent from the MSMEG_4727 mutant was performed by MS analysis of the methanol-soluble lipids produced by the M. smegmatis strains (Fig. 5B). The MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of the lipids from the wild-type strain ATCC 607 showed three major clusters of pseudomolecular ion [M + Na]+ peaks; the first cluster, centered at m/z 1297, corresponded to the type I GPL (16, 48), whereas the second one, at m/z 1459, was assigned to PIM2 (20). The third cluster consisted of two peaks at m/z 1689 and 1717, which perfectly matched with the calculated masses of Na adducts of LOS-A (5, 16). This cluster was absent from the methanol-soluble lipids produced by the MSMEG_4727 mutant PMM123 but was present again in the complemented strain (Fig. 5C), although it was barely detectable in the total lipid fraction (Fig. 5B). The minor [M + Na]+ peak at m/z 1543 was attributed to GPL IIIb (16, 48).

Structural analysis of the LOS from M. smegmatis ATCC 607.

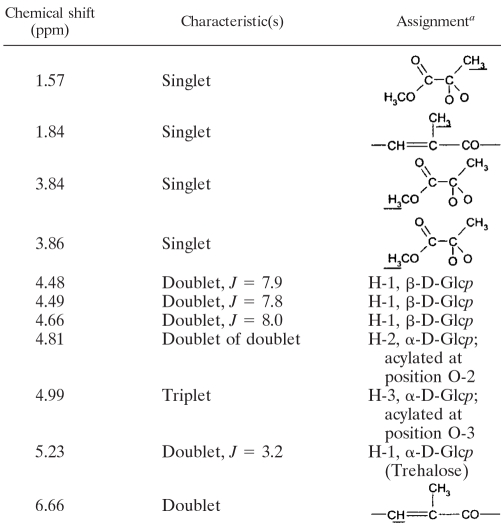

The LOS-A- and LOS-B-like compounds were purified by preparative TLC and analyzed. LOS-A-like glycolipids purified from both the wild-type and the complemented strains displayed the pair of [M + Na]+ peaks at m/z 1689 and 1717 (Fig. 5C). GC/MS analysis of the FAME prepared from the purified LOS-A gave four major peaks. Peaks corresponding to the most volatile FAME exhibited the retention times and molecular masses of C16, C18:1, and C18 FAME, whereas the largest FAME peak gave a molecular ion at m/z 352 and a fragmentation pattern corresponding to the 2,4-dimethyl-2-eicosenoic acid methyl ester (data not shown). The 1H-NMR spectrum of the purified LOS-A-like compounds from the wild-type strain showed the presence of all the characteristic features of an LOS molecule (Table 3). Specifically, resonances of three β-d-Glcp residues (δ 4.48, δ 4.49, and δ 4.66) and one α-d-Glcp residue (δ 5.23) were observed. The other anomeric proton signal of the trehalose moiety was overlapped with that of a contaminant. Interestingly, multiplets were seen at δ 4.81 and δ 4.99 and were attributable to proton resonances of H-2 and H-3 of an α-d-Glcp residue(s) acylated at O-2 and O-3, respectively (5), in agreement with the reported structure of LOS (Fig. 1). Specific signals due to the unique dipyruvylated nature of the LOS were the prominent resonances assignable to the methyl groups at δ 3.84 and δ 3.86 and that of a pyruvate ketal at δ 1.57 (Table 3). Finally, the presence of an unsaturated PMB-FA moiety in the molecule was confirmed by the presence of resonance signals attributable to the methyl group at δ 1.84 and to the singlet at δ 6.64, which corresponds to the methine proton resonance conjugated with an ester function (5).

TABLE 3.

Characteristic 1H NMR data for M. smegmatis LOS-A

a The assigned protons are underlined.

When analyzed in the same way, the purified LOS-B-like compounds from the wild-type and the complemented strains displayed a pair of [M + H]+ peaks at m/z 1515 and 1543; minor putative [M + Na]+ adducts were also detected, with an upshift of 22 atomic mass units at m/z 1537 and 1565. Based on their molecular masses, these LOS-B-like compounds were different from all the various LOS-B described so far in M. smegmatis (5, 25, 43), suggesting that the LOS-B-like compounds described here represented new LOS variants, which we named LOS-C. Although the amount of these purified compounds was not sufficient to conduct complete structural studies, the 2,4-dimethyl-2-eicosenoic acid methyl ester was identified by GC/MS analysis of the FAME from the LOS-C through its retention time and molecular ion peak at m/z 352 (data not shown). In addition, the 1H NMR spectrum revealed the presence of specific signals of the double ester methyl groups at δ 3.84 and δ 3.86, indicating the occurrence of two pyruvyl residues in the molecule (data not shown), a feature characteristic of LOS (5, 43). Taken together, these results strongly suggested that the MSMEG_4727 gene is implied in the biosynthesis of three species of LOS in M. smegmatis ATCC 607.

Cell surface properties of the M. smegmatis MSMEG_4727 mutant strain.

LOS have been recently shown to play important functions in M. marinum, being implicated in sliding motility, biofilm formation, and invasion of macrophages (40). In M. smegmatis strains producing large amounts of GPL and in one strain, mc2155, producing no LOS (16), GPL were shown to be the major determinant of cell surface properties, including colony morphology (17, 39), sliding motility (38, 39), biofilm formation (38), envelope permeability (17), and internalization by phagocytic cells (17, 48). Thanks to the construction of two strains of M. smegmatis differing only in LOS production, both being poor GPL producers, we attempted to study particular LOS functions. When the wild-type and the mutant strains were compared in various tests monitoring the surface properties, no differences in sliding motility, hydrophobicity index, or adhesion on PVC were found (Table 4). These results were unexpected in view of TLC analysis that showed that LOS were one of the major glycolipids in the wild-type ATCC 607 (Fig. 5A) and in view of published results implicating LOS in cell surface properties of M. marinum (40). The only significant difference observed between the wild-type and mutant strains was in their ability to adsorb Congo red (Table 4), a marker of cell envelope hydrophobicity (9). This prompted us to estimate the surface exposure of LOS in M. smegmatis. Indeed, LOS have been shown to be surface exposed in “M. canettii,” M. kansasii, and M. gastri (34), but no conclusion could be drawn for M. smegmatis mc2155 because this strain produces virtually no LOS (16). The surface-exposed lipids and the lipids that remained attached to the cellular residues were extracted from strain ATCC 607 and analyzed semiquantitatively by TLC. Only a tiny amount of LOS-A could be detected in the surface-exposed lipids, which was composed primarily of glycerol monomycolate (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In contrast, LOS-A were easily detected in the cellular fraction, which contained roughly 99.5% of these compounds.

TABLE 4.

Surface properties of the M. smegmatis wild-type strain ATCC 607, the mutant strain PMM123, and the complemented strain PMM123::pWM96a

| Strain | Motility (diam [cm] of halo formed) on plates:

|

Congo red binding (A488, 10−3) | Hydrophobicity index (% of cells recovered in organic phase) | Adhesion on PVC (no. of adherent cells per microscopic field) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Tween 80 | With 0.05% Tween 80 | ||||

| ATCC 607 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 33.3 ± 4.0 | 24.9 ± 4.2 | 46 ± 19 |

| PMM123 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 98.9 ± 6.1b | 29.0 ± 7.5 | 49 ± 8 |

| PMM123::pWM96 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 1.0 | 53.5 ± 8.7 | 22.0 ± 3.2 | 39 ± 7 |

All values are means ± standard deviations from at least three independent experiments.

P < 0.01 compared with control.

The inhibitory activity of antimycobacterial agents may be influenced by the permeability of the cell wall, which in turn would determine whether certain antibiotics can enter bacteria and exert their action. We therefore comparatively investigated the susceptibilities of the MSMEG_4727 mutant PMM123 and its parent strain to various compounds. The MICs of the seven antibiotics examined were unaffected by the mutation, whatever their chemical structures. The MICs of both the lipophilic compounds, i.e., rifampin (128 μg·ml−1), chloramphenicol (16 μg·ml−1), and novobiocin (16 μg·ml−1), and of the hydrophilic antibiotics, i.e., Km (2 μg·ml−1), streptomycin (2 μg·ml−1), isoniazid (0.5 μg·ml−1), and ethambutol (1 μg·ml−1), were unchanged. These data suggested that LOS have only a limited impact, if any at all, on the permeability of the mycobacterial cell wall.

DISCUSSION

We showed that M. smegmatis strain ATCC 607 with the MSMEG_4727 (pks5) gene disrupted is no longer able to synthesize LOS. Indeed, structural studies unequivocally demonstrated that the main glycolipid absent from the mutant strain was the major species-specific LOS-A species (5, 43). We also showed that the only fatty acid absent from the mutant strain was 2,4-dimethyl-2-eicosenoic acid, suggesting that it was the synthesis of this particular fatty acid which was affected in the mutant. Although the unsaturated C24 PMB-FA was not detectable in the total fatty acid extract from the complemented strain, this fatty acid was clearly identified among the constituents of the LOS-A purified from the complemented PMM123::pWM96 strain, demonstrating that the complementation experiment was successful and that Pks5 was implied in the synthesis of the PMB-FA moiety of the M. smegmatis LOS. No new glycolipid, e.g., diacylated LOS, was accumulated in the mutant. The partial complementation observed with the PMM123::pWM96 strain could be due either to poor expression of the pks gene from our construct or to a polar effect of the hyg cassette insertion on the expression of downstream genes of the cluster.

Indeed, MSMEG_4727 (pks5) is the first open reading frame (ORF) of the cluster of 15 genes identified in the present study that is likely involved in the biosynthesis of LOS. It is noteworthy that the M. tuberculosis pks gene that is the putative orthologue of MSMEG_4727 is Rv1527 (pks5); this gene lies in a cluster of genes recently postulated by analogy with M. marinum (40) to be involved in LOS biosynthesis. This observation prompted us to tentatively complement the MSMEG_4727 mutant with its putative M. tuberculosis orthologue (pks5). However, we were unable to restore LOS production in PMM123 carrying the pks5 gene from M. tuberculosis. This may be due to the low level of expression of the gene, as already discussed for the complementation with the native MSMEG_4727 gene itself. An alternative possibility that involves the nonfunctionality of the pks5 gene from the H37Rv strain of M. tuberculosis used for the complementation experiment is not supported by the literature data. It has been recently reported that an H37Rv mutant containing an insertion within the pks5 gene was affected in virulence in mice (42), suggesting that the pks5 gene is actually expressed and functional in H37Rv. As LOS are virtually not produced by strains of M. tuberculosis sensu stricto such as H37Rv (13) but are produced by the “M. canettii” species of the M. tuberculosis complex, no missing compound was detected in the pks5 mutant in comparison to the wild-type strain. This raises the possibility that Pks5 is implicated in the production of a yet-unidentified putative virulence factor of M. tuberculosis.

In the cluster identified here, other genes immediately adjacent to MSMEG_4727 are postulated to encode enzymes associated with the Pks in the synthesis of the PMB-FA and its transfer, namely, MSMEG_4731 (FadD) for the activation of the Pks substrate (18) and the putative acyltransferase MSMEG_4728 (Pap) (33), respectively. Two other genes, MSMEG_4733 (gap2) and MSMEG_4741 (mmpL), are homologues of genes previously identified in M. smegmatis and other mycobacterial species as mediating the translocation of glycolipids and their transport to the cell surface. MmpL7 is the first member of this transmembrane protein family identified in M. tuberculosis as being required for the transport and/or exposure of the polyketide phthiocerol dimycoserate at the cell surface (8). M. tuberculosis MmpL8, which is involved in the synthesis of another polyketide-containing lipid, sulfolipid-1, possibly transports a precursor of this molecule from the cytoplasm to the periplasm (10). Accordingly, we postulated that the MmpL protein putatively encoded by MSMEG_4741 would have such a function in LOS synthesis. The last stage of the envelope biogenesis would be the addressing of the glycolipids to the outer layers, a function probably carried out by Gap (for GPL-addressing protein) in GPL synthesis (45) and possibly performed by the paralogous MSMEG_4733 (45) in the case of the LOS. It is noteworthy that paralogues of these five genes (pks, pap, fadD, mmpL, and gap) are conserved in the GPL synthesis clusters of M. smegmatis (45), M. abscessus (41), M. chelonae (41), and M. avium (14) but also in the LOS biosynthetic gene cluster of M. marinum (40) and in the postulated LOS cluster of M. tuberculosis (40). This may delineate a minimum set of genes required for the synthesis and export of polyketide-containing glycolipids in mycobacteria, at least GPL and LOS. The remaining genes of the three identified or putative LOS biosynthetic clusters display less homology, if any. This observation is not unexpected since LOS share the PMB-FA-O-acylated trehalose core but largely differ from one another in the number and the nature of the sugar residues that compose the glycolipids (12).

The identification of the LOS biosynthetic gene cluster in M. smegmatis and the generation of the first pair of strains of mycobacteria differing only in LOS production gave us an ideal tool to determine the role of LOS in the physiology of M. smegmatis. For this species very little information is available on the biological properties except that they have been implicated in mycobacteriophage resistance (5). In contrast, numerous studies have been devoted to GPL, the main glycolipid of M. smegmatis and a surface-exposed constituent of this species (17). Although dispensable (39), GPL have been shown to be involved in a number of biological properties of M. smegmatis, such as colony morphology (39), surface hydrophobicity (16, 17), sliding motility (38, 39), biofilm formation (38), cell wall permeability (16, 17), mycobacteriophage adsorption (19), and phagocytosis (48). We have recently reported that, in contrast to its progeny strains mc2155 (44) and 607T (16), the original ATCC 607 wild-type strain of M. smegmatis did not produce GPL (27). This allowed us to construct a mutant strain lacking both GPL and LOS. Comparison of the mutant with its parental wild-type strain showed that LOS play only a limited role in cell surface properties of M. smegmatis, being involved neither in sliding motility nor in adhesion, in sharp contrast with what has been described for M. marinum. In the latter species LOS have been found to play an important role in sliding motility, biofilm formation, and infection of murine macrophage-like cells (40), consistent with their location at the surface of cells of several mycobacterial species (34). The apparent discrepancy between our finding and the data from M. marimum is easily explained by the demonstration that most, if not all, LOS of M. smegmatis are not located at the bacterial surface; rather, they are constituents of deeper layers of the M. smegmatis cells. This rationally explains the fact that the only difference between the wild-type and the mutant strains was in adsorption of Congo red, a hydrophobic dye that freely diffuses in the mycobacterial cell envelope (9). Accordingly, the observed difference in the Congo red binding is likely an indicator of the change in the overall lipid content of this compartment in the strains rather than their cell surface properties sensu stricto. The possibility remains, however, that LOS can be implicated in biological properties not yet tested, such as viability in stationary phase, since the pks5 gene has previously been shown to be involved in the long-term survival of M. smegmatis (26).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sophie Chumbinho for technical assistance.

The NMR spectrometers were financed by the CNRS, the University Paul Sabatier, the Région Midi-Pyrénées, and the European Structural Funds (FEDER).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 30 January 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aspinall, G. O., D. Chatterjee, and P. J. Brennan. 1995. The variable surface glycolipids of mycobacteria: structures, synthesis of epitopes, and biological properties. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 51169-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AsseIineau, J., R. Ryhage, and E. Stenhagen. 1957. Mass spectrometric studies of long chain methyl esters. Determination of the molecular weight and structure of mycocerosic acid. Acta Chem. Scand. 11196-198. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belisle, J. T., and P. J. Brennan. 1989. Chemical basis of rough and smooth variation in mycobacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1713465-3470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belisle, J. T., and M. G. Sonnenberg. 1998. Isolation of genomic DNA from mycobacteria. Methods Mol. Biol. 10131-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Besra, G. S., K.-H. Khoo, J. T. Belisle, M. R. McNeil, H. R. Morris, A. Dell, and P. J. Brennan. 1994. New pyruvylated, glycosylated acyltrehaloses from Mycobacterium smegmatis strains, and their implications for phage resistance in mycobacteria. Carbohydr Res. 25199-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosch, R., S. V. Gordon, M. Marmiesse, P. Brodin, C. Buchrieser, K. Eiglmeier, T. Garnier, C. Gutierrez, G. Hewinson, K. Kremer, L. M. Parsons, A. S. Pym, S. Samper, D. van Soolingen, and S. T. Cole. 2002. A new evolutionary scenario for the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 993684-3689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burguiere, A., P. G. Hitchen, L. G. Dover, L. Kremer, M. Ridell, D. C. Alexander, J. Liu, H. R. Morris, D. E. Minnikin, A. Dell, and G. S. Besra. 2005. LosA, a key glycosyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of a novel family of glycosylated acyltrehalose lipooligosaccharides from Mycobacterium marinum. J. Biol. Chem. 28042124-42133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camacho, L. R., P. Constant, C. Raynaud, M.-A. Lanéelle, J. A. Triccas, B. Gicquel, M. Daffé, and C. Guilhot. 2001. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J. Biol. Chem. 27619845-19854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cangelosi, G. A., C. O. Palermo, J.-P. Laurent, A. M. Hamlin, and W. H. Brabant. 1999. Colony morphotypes on Congo red agar segregate along species and drug susceptibility lines in the Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex. Microbiology 1451317-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Converse, S. E., J. D. Mougous, M. D. Leavell, J. A. Leary, C. R. Bertozzi, and J. S. Cox. 2003. MmpL8 is required for sulfolipid-1 biosynthesis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1006121-6126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daffé, M., and P. Draper. 1998. The envelope layers of mycobacteria with reference to their pathogenicity. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 39131-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daffé, M., and A. Lemassu. 2000. Glycobiology of the mycobacterial surface. Structures and biological activities of the cell envelope glycoconjugates, p. 225-273. In R. J. Doyle (ed.), Glycomicrobiology. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY.

- 13.Daffé, M., M. McNeil, and P. J. Brennan. 1991. Novel type-specific lipooligosaccharides from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biochemistry. 30378-388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshayes, C., D. Kocincova, G. Etienne, and J.-M. Reyrat. 2008. Glycopeptidolidpids: a complex pathway for small pleiotropic moecules, p. 345-366. In M. Daffé and J.-M. Reyrat (ed.), The mycobacterial cell envelope. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 15.Dye, C., S. Scheele, P. Dolin, V. Pathania, and M. C. Raviglione. 1999. Consensus statement. Global burden of tuberculosis: estimated incidence, prevalence, and mortality by country. W. H. O. Global Surveillance Monitoring Project. JAMA. 282677-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Etienne, G., F. Laval, C. Villeneuve, P. Dinadayala, A. Abouwarda, D. Zerbib, A. Galamba, and M. Daffé. 2005. The cell envelope structure and properties of Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155: is there a clue for the unique transformability of the strain? Microbiology 1512075-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etienne, G., C. Villeneuve, H. Billman-Jacobe, C. Astarie-Dequeker, M.-A. Dupont, and M. Daffé. 2002. The impact of the absence of glycopeptidolipids on the ultrastructure, cell surface and cell wall properties, and phagocytosis of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Microbiology 1483089-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzmaurice, A. M., and P. E. Kolattukudy. 1998. An acyl-CoA synthase (acoas) gene adjacent to the mycocerosic acid synthase (mas) locus is necessary for mycocerosyl lipid synthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. bovis BCG. J. Biol. Chem. 2738033-8039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furuchi, A., and T. Tokunaga. 1972. Nature of the receptor substance of Mycobacterium smegmatis for D4 bacteriophage adsorption. J. Bacteriol. 111404-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilleron, M., C. Ronet, M. Mempel, B. Monsarrat, G. Gachelin, and G. Puzo. 2001. Acylation state of the phosphatidylinositol mannosides from Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette Guerin and ability to induce granuloma and recruit natural killer T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 27634896-34904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guilhot, C., and M. Daffé. 2008. Polyketides and polyketide-containing glycolipids of M. tuberculosis: structure, biosynthesis and biological activities, p. 21-51. In S. H. E. Kaufmann and E. J. Rubin (ed.), Tuberculosis: molecular biology and biochemistry, vol. 1. Wiley-Vch Verlag GmBH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter, S. W., R. C. Murphy, K. Clay, M. B. Goren, and P. J. Brennan. 1983. Trehalose-containing lipooligosaccharides. A new class of species-specific antigens from Mycobacterium. J. Biol. Chem. 25810481-10487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1990. Permeability barrier to hydrophilic solutes in Mycobacterium chelonei. J. Bacteriol. 1721418-1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarlier, V., and H. Nikaido. 1994. Mycobacterial cell wall: structure and role in natural resistance to antibiotics. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 12311-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamisango, K., S. Saadat, A. Dell, and C. E. Ballou. 1985. Pyruvylated glycolipids from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Nature and location of the lipid components. J. Biol. Chem. 2604117-4121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keer, J., M. J. Smeulders, K. M. Gray, and H. D. Williams. 2000. Mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis impaired in stationary-phase survival. Microbiology 1462209-2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kocincova, D., A. K. Singh, J. L. Beretti, H. Ren, D. Euphrasie, J. Liu, M. Daffé, G. Etienne, and J. M. Reyrat. 2008. Spontaneous transposition of IS1096 or ISMsm3 leads to glycopeptidolipid overproduction and affects surface properties in Mycobacterium smegmatis. Tuberculosis 88390-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laval, F., M.-A. Lanéelle, C. Deon, B. Monsarrat, and M. Daffé. 2001. Accurate molecular mass determination of mycolic acids by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 734537-4544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Dantec, C., N. Winter, B. Gicquel, V. Vincent, and M. Picardeau. 2001. Genomic sequence and transcriptional analysis of a 23-kilobase mycobacterial linear plasmid: evidence for horizontal transfer and identification of plasmid maintenance systems. J. Bacteriol. 1832157-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemassu, A., V. V. Levy-Frebault, M.-A. Laneelle, and M. Daffe. 1992. Lack of correlation between colony morphology and lipooligosaccharide content in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1381535-1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minnikin, D. E., L. Kremer, L. G. Dover, and G. S. Besra. 2002. The methyl-branched fortifications of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Chem. Biol. 9545-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odham, G., and E. Stenhagen. 1972. Fatty acids, p. 211-249. In G. R. Waller (ed.), Biochemical applications of mass spectrometry. Wiley-Interscience, New York, NY.

- 33.Onwueme, K. C., J. A. Ferreras, J. Buglino, C. D. Lima, and L. E. Quadri. 2004. Mycobacterial polyketide-associated proteins are acyltransferases: proof of principle with Mycobacterium tuberculosis PapA5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1014608-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortalo-Magne, A., A. Lemassu, M.-A. Lanéelle, F. Bardou, G. Silve, P. Gounon, G. Marchal, and M. Daffé. 1996. Identification of the surface-exposed lipids on the cell envelopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacterial species. J. Bacteriol. 178456-461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelicic, V., M. Jackson, J. M. Reyrat, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., B. Gicquel, and C. Guilhot. 1997. Efficient allelic exchange and transposon mutagenesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9410955-10960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Portevin, D., C. De Sousa-D'Auria, C. Houssin, C. Grimaldi, M. Chami, M. Daffé, and C. Guilhot. 2004. A polyketide synthase catalyzes the last condensation step of mycolic acid biosynthesis in mycobacteria and related organisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101314-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Primm, T. P., C. A. Lucero, and J. O. Falkinham III. 2004. Health impacts of environmental mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1798-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Recht, J., and R. Kolter. 2001. Glycopeptidolipid acetylation affects sliding motility and biofilm formation in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 1835718-5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Recht, J., A. Martinez, S. Torello, and R. Kolter. 2000. Genetic analysis of sliding motility in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 1824348-4351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren, H., L. G. Dover, S. T. Islam, D. C. Alexander, J. M. Chen, G. S. Besra, and J. Liu. 2007. Identification of the lipooligosaccharide biosynthetic gene cluster from Mycobacterium marinum. Mol. Microbiol. 631345-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ripoll, F., C. Deshayes, S. Pasek, F. Laval, J.-L. Beretti, F. Biet, J.-L. Risler, M. Daffé, G. Etienne, J.-L. Gaillard, and J.-M. Reyrat. 2007. Genomics of glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium abscessus and M. chelonae. BMC Genomics 8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rousseau, C., T. D. Sirakova, V. S. Dubey, Y. Bordat, P. E. Kolattukudy, B. Gicquel, and M. Jackson. 2003. Virulence attenuation of two Mas-like polyketide synthase mutants of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiology 1491837-1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saadat, S., and C. E. Ballou. 1983. Pyruvylated glycolipids from Mycobacterium smegmatis. Structures of two oligosaccharide components. J. Biol. Chem. 2581813-1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snapper, S. B., R. E. Melton, S. Mustafa, T. Kieser, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1990. Isolation and characterization of efficient plasmid transformation mutants of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Mol. Microbiol. 41911-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonden, B., D. Kocincova, C. Deshayes, D. Euphrasie, L. Rhayat, F. Laval, C. Fréhel, M. Daffé, G. Etienne, and J.-M. Reyrat. 2005. Gap, a mycobacterial specific integral membrane protein, is required for glycolipid transport to the cell surface. Mol. Microbiol. 58426-440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stover, C. K., V. F. de la Cruz, T. R. Fuerst, J. E. Burlein, L. A. Benson, L. T. Bennett, G. P. Bansal, J. F. Young, M. H. Lee, G. F. Hatfull, S. B. Snapper, R. G. Barletta, W. R. Jacobs, Jr., and B. R. Bloom. 1991. New use of BCG for recombinant vaccines. Nature 351456-460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vergne, I., and M. Daffé. 1998. Interaction of mycobacterial glycolipids with host cells. Front. Biosci. 3d865-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Villeneuve, C., G. Etienne, V. Abadie, H. Montrozier, C. Bordier, F. Laval, M. Daffé, I. Maridonneau-Parini, and C. Astarie-Dequeker. 2003. Surface-exposed glycopeptidolipids of Mycobacterium smegmatis specifically inhibit the phagocytosis of mycobacteria by human macrophages. Identification of a novel family of glycopeptidolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 27851291-51300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yadav, G., R. S. Gokhale, and D. Mohanty. 2003. SEARCHPKS: a program for detection and analysis of polyketide synthase domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 313654-3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yadav, G., R. S. Gokhale, and D. Mohanty. 2003. Computational approach for prediction of domain organization and substrate specificity of modular polyketide synthases. J. Mol. Biol. 328335-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.