Abstract

Clostridium perfringens is the third most frequent cause of bacterial food poisoning annually in the United States. Ingested C. perfringens vegetative cells sporulate in the intestinal tract and produce an enterotoxin (CPE) that is responsible for the symptoms of acute food poisoning. Studies of Bacillus subtilis have shown that gene expression during sporulation is compartmentalized, with different genes expressed in the mother cell and the forespore. The cell-specific RNA polymerase sigma factors σF, σE, σG, and σK coordinate much of the developmental process. The C. perfringens cpe gene, encoding CPE, is transcribed from three promoters, where P1 was proposed to be σK dependent, while P2 and P3 were proposed to be σE dependent based on consensus promoter recognition sequences. In this study, mutations were introduced into the sigE and sigK genes of C. perfringens. With the sigE and sigK mutants, gusA fusion assays indicated that there was no expression of cpe in either mutant. Results from gusA fusion assays and immunoblotting experiments indicate that σE-associated RNA polymerase and σK-associated RNA polymerase coregulate each other's expression. Transcription and translation of the spoIIID gene in C. perfringens were not affected by mutations in sigE and sigK, which differs from B. subtilis, in which spoIIID transcription requires σE-associated RNA polymerase. The results presented here show that the regulation of developmental events in the mother cell compartment of C. perfringens is not the same as that in B. subtilis and Clostridium acetobutylicum.

Clostridium perfringens is a common cause of food poisoning, responsible for approximately 250,000 cases in the United States each year (47). After the ingestion of vegetative cells in contaminated food, an enterotoxin, CPE, is produced by sporulating cells in the gastrointestinal tract (11, 13). The enterotoxin binds to receptors on the surface of intestinal epithelial cells to form a pore and interacts with tight junction proteins, claudins (46). This triggers the loss of fluids and electrolytes, leading to the symptoms of diarrhea and intestinal cramping (12, 18).

CPE is produced only in the cytoplasm of the mother cell during sporulation of C. perfringens (10, 44). After sporulation is completed, the mother cell lyses to release the mature spore and CPE (9). In laboratory conditions, extracellular enterotoxin is first detected 9 to 10 h after inoculation into sporulation media and increases during the next 14 h as more CPE is released (9). C. perfringens strains that do not sporulate do not produce the enterotoxin (48).

Analysis of C. perfringens strains containing the cpe promoters fused to the Escherichia coli reporter gene gusA on a plasmid indicated that cpe is transcribed in very early stationary phase, about the same time that CPE protein levels were detected (49). It has been shown that only sporulating cells and not vegetative cells produce cpe mRNA (8, 49). These results demonstrate that CPE expression is controlled at the transcriptional level during sporulation. Zhao and Melville (73) found that there are three promoters that regulate the transcription of cpe. The P1 promoter has sequences similar to σK consensus recognition sequences, and the P2 and P3 promoters are similar to σE promoters (73).

The molecular regulation of sporulation in C. perfringens has not been studied in detail, as it has in Bacillus subtilis, which serves as a model for sporulation in gram-positive organisms. Spore formation in B. subtilis involves the formation of an asymmetric septum that divides the cell into the forespore and the mother cell after the organism reaches a nutrient-starved state (57). It has been observed that in C. perfringens the morphological events, which are divided into seven stages (I to VII), during the formation of the spore are similar to those of B. subtilis (26). In B. subtilis four sporulation-specific sigma factors, σF, σE, σG, and σK, are the major regulators of the sporulation process (23, 26, 38, 45). Homologues of these proteins have been found in C. perfringens (60).

In B. subtilis, σF and σG regulate gene expression in the forespore, while σE and σK control gene expression in the mother cell. These sigma factors are activated in an ordered fashion, with σF active first, followed by σE, σG, and σK last (45). In B. subtilis, the σF-encoding gene, spoIIAC, is transcribed by σH-associated RNA polymerase during initiation of sporulation (20, 70). The σE-encoding gene, spoIIGB, is the second gene in an operon with spoIIGA (which encodes a protease that activates pro-σE) and is also transcribed before asymmetric septation (30, 36), but transcription continues only in the mother cell after septum formation (19). spoIIGB is transcribed by σA-associated RNA polymerase, a sigma factor associated mainly with the transcription of housekeeping genes (3, 23). Transcription of spoIIIG, the gene encoding σG, involves both σF- and σG-associated RNA polymerase (64), while sigK, the structural gene encoding σK, is transcribed by σE- and σK-associated RNA polymerase (39, 43, 63). While the sigK gene in B. subtilis is interrupted by a DNA element called skin (63) and another skin element is found in the Clostridium difficile sigK gene (24), these are not present in the sigK genes in the C. perfringens genomes that have been sequenced thus far (data not shown). In B. subtilis, the activation of sigK transcription is also regulated by the DNA-binding protein SpoIIID (39, 43). spoIIID is transcribed in the mother cell by σE-associated RNA polymerase (42, 66).

In B. subtilis, each of the four sporulation sigma factors is regulated posttranslationally. σF is held inactive by the anti-sigma factor SpoIIAB (14, 50), and inhibition is relieved upon formation of the asymmetrical septum early in sporulation (28, 40). SpoIIAB and another anti-sigma factor, CsfB, can also act as anti-sigma factors to suppress low levels of inappropriate σG activity, but the mechanism of σG activation to completion of forespore engulfment remains speculative (6, 7, 34, 35). σE and σK are first translated as inactive proproteins that become active only after proteases cleave amino acid residues from their N-terminal ends, and the pro-σE and pro-σK cleavage events in the mother cell depend on signals generated by σF and σG in the forespore, respectively (38, 45).

The genes encoding the four sporulation-specific sigma factors are present in C. perfringens and seem to be present in all of the Clostridium species for which the complete genome sequence is known (62). The role of clostridial sporulation-specific sigma factors in endospore development has been studied most thoroughly in Clostridium acetobutylicum, a solventogenic Clostridium species (15, 32). For C. acetobutylicum, the pattern of sigma factor expression during sporulation and solventogenesis for spoIIGA-sigE, sigG, and sigK matched that seen with B. subtilis (15), although it was spread out over a much longer time (35 h) than that seen with B. subtilis expression (∼8 h). In the last several years, Papoutsakis and colleagues have used complete genomic microarrays and quantitative reverse transcription (RT)-PCR to characterize the expression levels of sporulation-specific sigma factors and the sporulation transcriptional regulator Spo0A and to identify the transcriptomes specific to each factor in C. acetobutylicum (1, 2, 32, 52, 53, 67). They also found that sigF, sigE, and sigG transcription increased ∼50- to 200-fold during sporulation, but sigK expression was weak and not strongly induced during sporulation (32). Although the transcriptomes associated with each sigma factor in C. acetobutylicum are now being elucidated, the underlying mechanisms responsible for regulation of expression of the sigma factors themselves are still unknown for any species of Clostridium. Spo0A mutants have been constructed in several clostridia, they are usually blocked in sporulation at an early stage, and sporulation-specific sigma factors are not synthesized (2, 15, 25, 27). Since we have proposed that sporulation-specific sigma factors SigE and SigK play a major role in regulating CPE synthesis (73), we tested this hypothesis by constructing mutants in sigE and sigK and measuring CPE expression. We also examined expression of key mother cell genes (sigE, spoIIID, and sigK) in the mutants and characterized their sporulation phenotypes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

All bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (10 g tryptone, 10 g NaCl, 5 g yeast extract, and 15 g agar as needed per liter) at 37°C on plates or in broths with shaking. As needed, 300 μg/ml erythromycin and 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol were added to the medium.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| DH10B | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS mcrBC) φ80dlacZ ΔM15 lacX74 deoR recA1 araD139 Δ(ara, leu)7697 galU galK Δ-rpsL endA1 nupG | Gibco/BRL |

| JM107 | F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/e14− (McrA)Δ(lac-proAB) thi gyrA96(Nalr) endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) relA1 glnV44 | 72 |

| C. perfringens | ||

| SM101 | High efficiency of electroporation derivative of NCTC 8798 | 73 |

| KM1 | sigK mutant of SM101 | This study |

| KM2 | sigE mutant of SM101 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pSM240 | E. coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector containing the E. coli gusA gene; chloramphenicol resistance | This study |

| pKM4 | spoIIG promoter region fused to pSM240 | This study |

| pSM242 | sigK promoter region fused to pSM240 | This study |

| pSM300 | E. coli origin of replication; erythromycin resistance | 68 |

| pNLDK | pSM300 with the sigK gene internal fragment | This study |

| pNLDE | pSM300 with the sigE gene internal fragment | This study |

| pJV5 | E. coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector; chloramphenicol and kanamycin resistance | 69 |

| pSM305 | pBluescript SK− with a 3-kb HindIII insert containing complete sigK and pilT genes and gene fragments of CPR_1739 and ftsA from C. perfringens strain 8798, the parent strain of SM101 | 69 |

| pKM2 | pJV5 with complete sigK gene from plasmid pSM305 | This study |

| pKM3 | pJV5 with complete spoIIG operon | This study |

| pJIR750 | E. coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector; chloramphenicol resistance | 4 |

| pSM100 | pBluescript SK− with the NCTC 10240 cpe promoter | 49 |

| pSM104 | pJIR750 with Φ(cpeNCTC 10240-gusA) (P1, P2, and P3) | 49 |

| pSM127 | pSM104 with Φ(cpeNCTC10240-gusA) (P1 and P2) | 73 |

| pSM170 | pSM104 with Φ(cpeNCTC10240-gusA) (P3) | 73 |

C. perfringens strains were grown anaerobically in PGY medium (30 g proteose peptone no. 3, 20 g glucose, 10 g yeast extract, 1 g of sodium thioglycolate per liter) or brain heart infusion (Difco) at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products, Inc.), with 30 μg/ml erythromycin and 20 μg/ml chloramphenicol added as needed.

Construction of sigK and sigE mutants.

To create the sigK mutant, KM1, an internal 382-bp gene fragment of sigK was PCR amplified from the C. perfringens SM101 chromosomal DNA template using oligonucleotide primers OSM172 and OSM173. The sequences for all oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. OSM172 had a SacI restriction site, and OSM173 had a KpnI restriction site designed into the primer sequence. The resulting PCR product was then digested with SacI and KpnI and ligated into the C. perfringens suicide vector pSM300 (68), resulting in pNLDK.

To create the sigE mutant, KM2, a C. perfringens suicide vector containing a 433-bp internal fragment of the sigE gene was constructed. This fragment was PCR amplified using the oligonucleotides OSM168 and OSM169. OSM168 has a SacI restriction site, and OSM169 has a KpnI restriction site designed into the primer sequence. The resulting PCR product was digested with SacI and KpnI and ligated into pSM300, resulting in the plasmid pNLDE.

pNLDK and pNLDE were transformed into E. coli strain JM107 (recA+) by electroporation in order to produce a multimeric form of the plasmid. Multimeric plasmids have been found to insert into the chromosome via homologous recombination in C. perfringens more efficiently than monomeric forms (69). After passage through JM107, the plasmids were purified via a cesium chloride gradient. Sixteen micrograms of purified pNLDK and 24 μg of purified pNLDE were transformed into C. perfringens strain SM101 by electroporation as previously described (73) and then plated on brain heart infusion with 30 μg/ml erythromycin.

Southern blot analysis.

To confirm the insertion of the multimeric pNLDE and pNLDK plasmids into the sigE or sigK gene, Southern blotting was performed on the erythromycin-resistant transformants. Chromosomal DNA of C. perfringens strain KM1 (sigK mutant) was digested with PstI and EcoRI, and the digested DNA separated by electrophoresis on a 0.8% agarose gel and transferred to nitrocellulose by blotting. Hybridization with a biotinylated probe specific to the internal fragment of sigK was used to detect the sigK gene in C. perfringens SM101 and in C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant). A shift from 2 kb to >10 kb indicated the recombination of pNLDK into the sigK gene (data not shown). A similar procedure was performed to confirm the sigE mutant, except that chromosomal DNA from the erythromycin-resistant transformant, C. perfringens strain KM2 (sigE mutant), was digested with XbaI. A shift from a wild-type size of 2.1 kb to >10 kb indicated the recombination of pNLDE into the sigE gene (data not shown).

Construction of complementation plasmids for C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) and C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant).

Complementation of C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) was attempted by first digesting pSM305 with PstI and HincII to produce a fragment spanning the complete sigK gene and its promoter. This fragment was then ligated into the E. coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector, pJV5, which had been digested with SmaI and PstI, to produce the plasmid pKM2 (Table 1).

Complementation of C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) was attempted by first PCR amplifying the entire operon, consisting of spoIIGA, sigE, and 400 bp upstream of spoIIGA, from the C. perfringens SM101 chromosome using the oligonucleotide primers OKM9, which had a BamHI restriction site designed into the primer, and OKM11, which had an EcoRI restriction site designed into the primer. The PCR product was then digested with BamHI and EcoRI and ligated into pJV5, which had been digested with BamHI and EcoRI, resulting in the plasmid pKM3 (Table 1).

Sporulation assays.

C. perfringens strains were grown 14 to 16 h in 5 ml fluid thioglycolate medium (FTG) (Difco) with the appropriate antibiotic if needed. Two hundred fifty microliters of cell suspension was subcultured into 5 ml prewarmed sporulation medium, DSSM (15 g proteose peptone no. 3, 10 g sodium phosphate, 4 g raffinose, 4 g yeast extract, 1 g of sodium thioglycolate per liter, pH adjusted to 7.8) and grown anaerobically for 24 h at 37°C. Samples were diluted and plated in duplicate on PGY agar in the absence of antibiotics to determine the number of viable cells per milliliter of culture. Three hundred fifty microliters of samples were heated at 75°C for 15 min, diluted, and plated in duplicate on PGY agar to determine the number of spores per milliliter of culture. All assays were performed in triplicate. The following formula was used to determine the sporulation efficiency: sporulation efficiency (%) = [number of CFU in heated culture/(number of CFU in heated culture + number of CFU in unheated culture)] × 100.

Transmission EM.

C. perfringens strains were grown 14 to 16 h in 5 ml FTG with the appropriate antibiotic, and then 750 μl was inoculated into 75 ml of DSSM. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was measured every hour for 8 h using a Genesys 10 UV scanning spectrophotometer. One-milliliter samples were obtained at 3, 5, and 8 h postinoculation into DSSM, corresponding to mid-log phase, early stationary phase, and stationary phase, respectively. Samples were centrifuged, and the pellet was suspended in 84 μl of 0.5 M NaPO4, pH 7, and 5 μl of 25% electron microscopy (EM)-grade glutaraldehyde by gentle vortexing and then stored at 4°C overnight. The samples were washed four times with ice-cold 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.7, suspended in 1% osmium in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.7), and stored at 4°C overnight. The samples were then washed in 0.5 M NH4Cl, suspended in 2% melted, warm agar and immediately centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 3 to 5 min at 4°C. A standard ethanol dehydration was performed, and the samples were embedded in Spurr's resin. Samples were sectioned, collected on grids, and stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 5 min and Reynold's lead for 1 min.

The phenotypes of C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) in mid-log phase, early stationary phase, and stationary phase after inoculation into DSSM, as well as those of C. perfringens KM1(pKM2) (complemented sigK mutant) and C. perfringens KM2(pKM3) (complemented sigE mutant) in stationary phase after inoculation into DSSM, were quantified by determining the stage of development present in a population of sporulating cells. Only complete longitudinal sections of cells were assessed. The number of cells examined for each sample ranged from 17 to 49, except for C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) at 3 h, in which six cells were counted.

Extraction of RNA, primer extension, and RT-PCR.

C. perfringens SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) strains were grown 14 to 16 h in FTG, with erythromycin if needed. A 1% inoculum was transferred to prewarmed DSSM, and growth of the culture was measured at an OD600. Fifty milliliters of culture was collected at an OD600 of 0.1 and 1.0, representing early log and early stationary phases of growth, respectively. Cells were concentrated and stored at −80°C. RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), and contaminating DNA was removed with RQ1 DNase (Promega), according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was stored in liquid nitrogen until use.

Primer extension for spoIIGA-sigE and sigK was done using 1 μg of RNA extracted from cells grown to mid-log phase for spoIIGA-sigE or early stationary phase for sigK. The extension reaction was done according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega) and included primers OKM19 (spoIIGA) and OKM22 (sigK), each tagged with 6-carboxy fluorescein on the 5′ end. The primer extension product was separated by capillary electrophoresis and compared to defined size standards to determine the length of the primer extension product.

To determine the transcriptional activity of genes in the sigK region, primers were designed to amplify an internal fragment of pilT and the intergenic regions between sigK, pilT, and ftsA. A primer was designed 57 bp upstream of the CPR_1739 stop codon (OKM12) and 502 bp downstream of the sigK start codon (OJV13) to determine if sigK is cotranscribed with CPR_1739, which is annotated as a penicillin binding protein with a transpeptidase domain (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=genomeprj&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=12521). To determine if there is a transcript extending between sigK and pilT, a primer was designed 113 bp upstream of the sigK stop codon (OJV12) and 626 bp downstream of the pilT start codon (OJV22). To determine if pilT is transcribed during sporulation in C. perfringens SM101 and if its transcription is affected by a mutation in the sigK gene, primers were designed internal to pilT (OJV11 and OJV22). In order to determine if pilT and ftsA are cotranscribed and if a mutation in sigK blocks this transcription, OJV11 (942 bp upstream of the pilT stop codon) was used with a primer designed 53 bp downstream of the ftsA start codon (OJV18).

For RT-PCR measurements of the transcriptional activity of sporulation sigma factor-encoding genes, oligonucleotide primers were designed internal to the genes. Oligonucleotide primers OSM166 and OSM167 were used to amplify a 487-bp region of sigF, OSM168 and OSM169 to amplify a 433-bp fragment of sigE, OSM170 and OSM171 to amplify a 431-bp fragment of sigG, and OSM172 and OSM173 to amplify a 382-bp fragment of sigK. OSM168 and OSM169 were used in the mutagenesis of the sigE gene in C. perfringens SM101 to create C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant), and OSM172 and OSM173 were used in the mutagenesis of the sigK gene to create C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant).

To determine if spoIIID was cotranscribed with the upstream gene CPR_2157, the oligonucleotide primer OKM34 was designed to anneal 248 bp upstream of the stop codon in the CPR_2157 gene and OKM23 was designed to anneal 49 bp downstream of the start codon in spoIIID.

cDNA synthesis was performed by reverse transcription of 2 μg RNA with 50 pmol of each primer using the Access RT-PCR kit (Promega), following the manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCRs set up without reverse transcriptase made it possible to verify the absence of contaminating DNA. All RT-PCRs were performed in duplicate.

Construction of fusions to the spoIIG and sigK promoter regions.

To determine if the region upstream of spoIIGA, the promoter-proximal gene in the spoIIG operon, can function as a promoter, a PCR product containing 199 bp upstream of spoIIGA and the first 39 bp of the spoIIGA gene was ligated upstream of the β-glucuronidase-encoding gene, gusA, in the E. coli-C. perfringens shuttle vector pSM240, to create a translational fusion in pKM4 (Table 1). The region was amplified by PCR using the oligonucleotide primers OKM14 and OKM15.

To determine if there was a promoter located upstream of sigK, oligonucleotide primers OSM125 and OSM139 were used to amplify a 105-bp region upstream of the sigK gene. OSM125 had a PstI restriction site designed into the primer, and OSM139 had a SalI restriction site designed into the primer. This product was then digested and ligated into pSM240, resulting in the plasmid pSM242 (Table 1).

Western blots.

C. perfringens strains were grown overnight at 37°C in 5 ml FTG medium. Cells were then subcultured by inoculating 750 μl into 75 ml prewarmed DSSM. Over a time period beginning 1 h after inoculation into DSSM, 1 ml of culture was collected and the OD600 was measured. One-milliliter samples were also collected at these time points and centrifuged, and cell pellets were stored at −80°C. Extracts were prepared as described previously (74), except with lysis buffer at pH 8.0. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (41), except the antibodies used to detect pro-σK and σK were used at a 1:5,000 dilution. These and other antibodies made against B. subtilis proteins were used to detect the corresponding C. perfringens proteins. Antibodies used to detect SpoIIID have been described (21) and were used at a 1:10,000 dilution. Monoclonal antibody against σE (a gift from W. Haldenwang) was used at a 1:1,000 dilution to detect pro-σE and σE, with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Promega) at a 1:1,000 dilution serving as the secondary antibodies.

RESULTS

The C. perfringens sigK mutant and sigE mutant are severely defective in their ability to sporulate.

Both C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant) formed less than 10 heat-resistant spores per ml after incubation in DSSM for 24 h, whereas the wild-type strain, SM101, formed an average of 4 × 107 spores/ml. The sporulation efficiencies of KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant) were 0.0003% and 0.0006%, respectively, while SM101 had a sporulation efficiency of 80% (Fig. 1). These results suggest that σE and σK are essential for formation of heat-resistant spores.

FIG. 1.

Sporulation efficiencies of C. perfringens SM101 and the sigma factor mutants with and without complementing plasmids. Sporulation efficiencies of wild-type strain SM101 and mutants KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant) were measured with no plasmid or with complementing plasmid. pKM2, wild-type sigK gene; pKM3, wild-type sigE gene; bar, standard deviation.

Complementation of C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant).

To complement KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant), the entire spoIIGA-sigE operon and the upstream promoter (plasmid pKM3) and the sigK gene and the upstream promoter (plasmid pKM2) were transformed into KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant), respectively, by electroporation. KM2(pKM3) produced an average of 3.1 × 105 spores/ml, and its sporulation efficiency was 1.7%, which was about 3,000-fold higher than that of its KM2 parent (Fig. 1). Similarly, KM1(pKM2) (the complemented sigK mutant strain) produced an average of 2.6 × 105 spores/ml, and its sporulation efficiency was 1.3%, which was about 4,000-fold higher than that of its KM1 parent (Fig. 1). However, neither complemented strain showed a sporulation efficiency equal to that of strain SM101 (80%).

To determine if the increased spoIIGA-sigE and sigK gene copy numbers would have an effect on sporulation efficiency in the wild-type strain, pKM3 and pKM2 were also transformed into C. perfringens SM101. These are multicopy plasmids with an estimated 20 to 25 copies/cell, based on the characteristics of the parent plasmid, pIP404 (58). SM101(pKM3) had a sporulation efficiency of about 23%, producing an average of 6.3 × 106 spores/ml, while SM101(pKM2) had a sporulation efficiency of about 60%, producing an average of 2.3 × 107 spores/ml (Fig. 1). Because the sporulation efficiencies of SM101 with the complementing plasmids were not lowered to 1 or 2%, we determined that the increased copy numbers of the complementing genes contribute to but are not solely responsible for the lack of full complementation in KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant).

Because we could not achieve full complementation and because C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) was blocked unexpectedly (based on the B. subtilis paradigm) early in sporulation (see below), we remade multiple sigK mutant strains using pNLDK and attempted to complement each of them with pKM2. Nine sigK mutants were isolated from two separate electroporation experiments, and each mutant produced less than 10 spores/ml (data not shown). When complemented with pKM2, the mutants had an average sporulation efficiency of 2.8% (data not shown), which was similar to that observed in the original sigK mutant, KM1. These results indicate that KM1 exhibited typical complementation behavior, so the observed partial complementation is not likely due to a second-site mutation. Possible explanations for the observed partial complementation are presented below and in Discussion.

C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) is blocked earlier in sporulation than KM2 (sigE mutant).

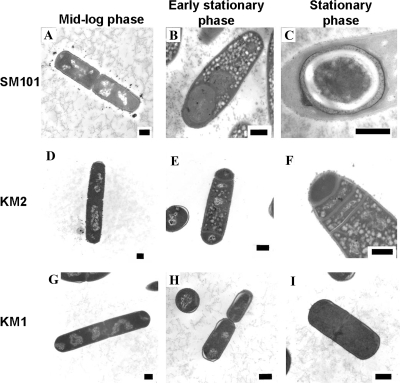

Samples of C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) were analyzed by transmission EM to determine how mutations in the sigK and sigE genes affected the development of spores. Representative images of cells observed at mid-log phase (3 h postinoculation), early stationary phase (5 h postinoculation), and middle stationary phase (8 h postinoculation) are shown in Fig. 2. The cell morphology phenotypes observed in electron micrographs were quantified, and the results are shown in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs comparing sporulation in C. perfringens strains SM101, KM2 (sigE mutant), and KM1 (sigK mutant). Samples of sporulating cultures of strains SM101 (A to C), KM2 (D to F), and KM1 (G to I) were analyzed during mid-log phase (3 h after inoculation into DSSM) (A, D, and G), early stationary phase (5 h after inoculation into DSSM) (B, E, and H), and stationary phase (8 h after inoculation into DSSM) (C, F, and I) of growth. Bars in bottom right corners of electron micrographs represent 500 nm.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of cell morphologies of C. perfringens wild-type SM101 and the mutant strains KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant)a

| Strain | Hours after inoculation | Granules (%) | Vegetative (%) | Asymmetric septum (%) | Engulfment (%) | Disporic (%) | Multiseptate at one pole (%) | Stage IV/free spores (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM101 (wild type) | 3 | 15 | 90 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 80 | 37 | 0 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 74 | |

| KM2 (sigE mutant) | 3 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 32 | 71 | 15 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0 | |

| 8 | 35 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 35 | 0 | |

| KM1 (sigK mutant) | 3 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8 | 0 | 76 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

The phenotypes noted were quantified by observing only cells in which complete longitudinal sections were present.

For wild-type strain SM101 in mid-log phase, the large majority of cells were vegetative rods (Fig. 2A), although a few cells had begun the sporulation process by forming an asymmetric septum (stage II) or initiating engulfment (stage III) (Table 2). In early stationary phase, most cells were undergoing the process of engulfment (Fig. 2B); however, some remained in the vegetative state. By middle stationary phase, the majority of cells had formed mature endospores (stage VI) (Fig. 2C) or existed as free spores. In mid-log and especially in early stationary phase, granules, which we believe are either starch granules or polyhydroxybutyrate inclusions, were present in the mother cell (Fig. 2B). Similar granules have been reported in other sporulating organisms and serve as an energy source for the cell during sporulation (16, 37, 61).

C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) cells never developed beyond the stage of asymmetric septum formation. During mid-log phase, all of the cells viewed were vegetative rods (Fig. 2D and Table 2). In the early stationary phase, cells were forming asymmetric septa and some had a disporic phenotype (Fig. 2E) characteristic of sigE mutants in B. subtilis (29). By middle stationary phase, many cells had formed multiple asymmetric septa (Fig. 2F), which is another characteristic of mutants lacking σE in B. subtilis. Cells in early stationary and middle stationary phases also had granules (Fig. 2E and F), in contrast to the wild-type strain, in which granules were present only in early-stationary-phase cells.

In B. subtilis, a mutation in sigK blocks sporulation at stage IV, when phase-gray forespores have formed (17). Surprisingly, C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) appeared to be blocked early in development. During mid-log phase and early stationary phase, all of the cells were in the vegetative state (Fig. 2G and H and Table 2). Most of the cells were still vegetative at middle stationary phase (Fig. 2I); however, a low number of cells had formed an asymmetric septum (stage II), were disporic, or had completed engulfment (stage III) (Table 2). None of the cells that were characterized had granules (Table 2). Considering the absence of granules and the low number of cells with asymmetric septa, we propose that the sigK mutant is blocked at an earlier stage of development than the sigE mutant, which is different than what occurs in B. subtilis.

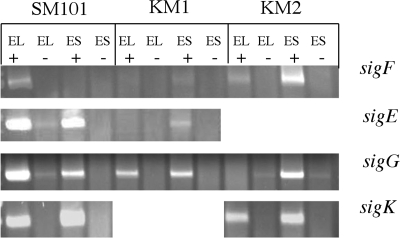

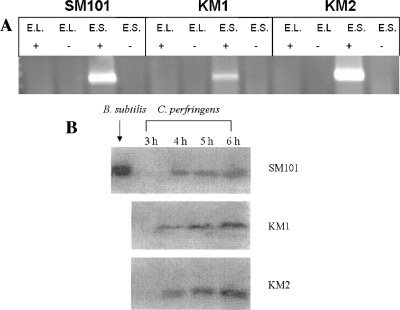

Transcription of sporulation sigma factor-encoding genes during early log and early stationary phases in C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant).

RT-PCR was utilized to determine if and when sigF, sigE, sigG, and sigK transcripts accumulate in C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant). RT-PCR amplification of sigE, sigG, and sigK in SM101 determined that transcripts from these three genes accumulate during early log (OD600 of 0.1) and early stationary phases (OD600 of 1.0), while sigF transcripts accumulated only during the early log phase (Fig. 3). The early-log-phase transcription of all the sporulation sigma factor-encoding genes was unexpected, because the orthologous genes in B. subtilis and C. acetobutylicum are not highly expressed during logarithmic growth but are induced during transition into sporulation (15, 32).

FIG. 3.

Transcription of sporulation sigma factor genes in C. perfringens SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) strains. RT-PCR of the four sporulation sigma factor genes in strains SM101, KM1, and KM2. Samples were collected during early log phase (EL) (OD600 of 0.1) and early stationary phase (ES) (OD600 of 1.0). + indicates reactions in which reverse transcriptase was added to the reaction. − indicates those reactions in which reverse transcriptase was not included in the reaction (negative control). Products were viewed on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel.

RT-PCR analysis of C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) indicated that σK-associated RNA polymerase is necessary for normal accumulation of sigF and sigE transcripts, but not sigG transcripts, although there appeared to be a reduced level of sigG transcripts in early log phase in strain KM1 compared to SM101 (Fig. 3). While there was no accumulation of sigF or sigE transcripts in early log phase, there appeared to be very low levels of these transcripts in early stationary phase. The dependence of sigF and sigE transcript accumulation on σK-associated RNA polymerase was unexpected, on the basis of the B. subtilis model (σK is last in the cascade) but could in part account for the early developmental block observed for KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 2G to I and Table 2).

For the sporulation sigma factor encoding-genes in C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant), accumulation of all sig transcripts was affected (Fig. 3). The sigF transcript accumulated in early stationary phase (unlike in SM101). There was no accumulation of the sigG transcript during early log phase (unlike SM101), but this transcript did accumulate in early stationary phase (comparable to SM101). The sigK transcript was present during early log and early stationary phase, but in slightly reduced amounts compared to SM101. In B. subtilis, sigK is not transcribed in the absence of σE-associated RNA polymerase, so the presence of the sigK transcript in KM2 (sigE mutant) was surprising and was investigated further as described below.

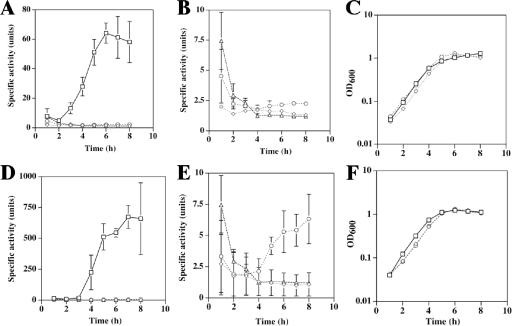

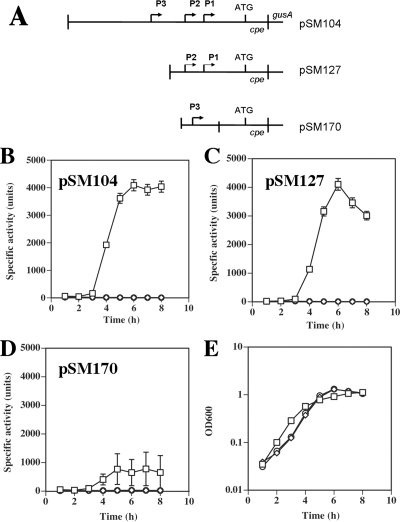

Expression from the spoIIGA and sigK promoter regions is eliminated in C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant).

Since the results shown in Fig. 3 indicated that mutations in the sigE and sigK genes have effects on sigK and sigE transcript levels, respectively, we decided to obtain a more quantitative analysis of expression by using translational fusions of the spoIIGA (the spoIIGA promoter drives transcription of the spoIIGA-sigE operon in B. subtilis) and sigK promoter regions (i.e., the promoter immediately upstream of the sigK gene) to a promoterless version of the E. coli gusA gene, which encodes the enzyme β-glucuronidase. However, we first needed to identify potential promoters upstream of the spoIIGA and sigK genes by primer extension experiments (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). For spoIIGA, a 5′ end at −15 relative to the ATG initiator codon was seen, and for sigK, 5′ ends at −68 and −117 were seen relative to the ATG initiator codon (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). Using this information, we constructed the fusion to contain sequences that include ∼200 bp upstream of the open reading frame for spoIIGA and for sigK to include the promoter located at −68 and upstream sequences (see Materials and Methods).

Strains were induced to sporulate by inoculation into DSSM, and samples were removed to measure β-glucuronidase activity. The activities of the spoIIGA-gusA fusion in C. perfringens strains SM101, KM2 (sigE mutant), and KM1 (sigK mutant) are shown in Fig. 4A. In SM101, the specific activity increased considerably between 2 and 3 h, which correlates with early or mid-log growth phase (Fig. 4C). This result is consistent with early-log sigE transcript accumulation (Fig. 3). The activity of the spoIIGA-gusA fusion was not above background levels of pSM240 (vector control with no promoter upstream of gusA) in KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 4B), indicating that both σE- and σK-associated RNA polymerase are directly or indirectly necessary for expression from the spoIIGA-gusA fusion. The dependence of expression on σK-associated RNA polymerase is consistent with the greatly reduced sigE transcript level that we observed with KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 3). Although we cannot be certain that the spoIIGA promoter is the source of the small amount of sigE transcript detected by RT-PCR in KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 3) or that the spoIIGA promoter fragment fused to gusA functions completely normally (Fig. 4), the small difference in the results could indicate that RT-PCR is more sensitive than the gusA fusion. The dependence of spoIIGA-gusA activity on σE-associated RNA polymerase suggests direct or indirect autoregulation, a feature not found with B. subtilis (phosphorylated Spo0A stimulates transcription from the spoIIGA promoter by σA-associated RNA polymerase) (23).

FIG. 4.

Expression of the spoIIGA-gusA and sigK-gusA translational fusions in C. perfringens wild-type SM101 and mutants KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant). (A) β-Glucuronidase activities of the spoIIGA-gusA fusion in C. perfringens strains SM101 (squares), KM2 (diamonds), KM1 (circles), and SM101 with the plasmid backbone pSM240 (triangles). (B) β-Glucuronidase activities shown in panel A are shown on a different scale. (C) Representative growth curves of strains SM101 (squares), KM2 (diamonds), and KM1 (circles) containing the spoIIGA-gusA fusion. (D) β-Glucuronidase activities of the sigK-gusA fusion in strains SM101 (squares), KM2 (diamonds), KM1 (circles), and the SM101(pSM240) control (triangles). (E) β-Glucuronidase activities shown in panel D are shown on a different scale. (F) Representative growth curves of strains SM101 (squares), KM2 (diamonds), and KM1 (circles) containing the sigK-gusA fusion.

The activity of the sigK-gusA fusion in C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) was also examined. SM101 showed induction of activity between 3 and 4 h after inoculation into sporulation media (Fig. 4D), corresponding to the late log or early stationary phase of growth (Fig. 4F). The absence of activity in the early log phase suggested that a different promoter was responsible for the sigK transcript detected by RT-PCR of RNA from early-log-phase cells (Fig. 3) (see below). Expression from the sigK-gusA fusion was significantly reduced during sporulation, but above the background level of activity seen with plasmid pSM240, in KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 4E), indicating that σK-associated RNA polymerase is needed for most, but not all, of the expression. However, sigK-gusA fusion activity was not above background levels in KM2 (sigE mutant) during sporulation (Fig. 4E), indicating that σE-associated RNA polymerase is absolutely necessary for expression. Absolute dependence of the sigK promoter on σE-associated RNA polymerase and partial dependence on σK-associated RNA polymerase (i.e., autoregulation) are features of the sigK promoter in B. subtilis (43).

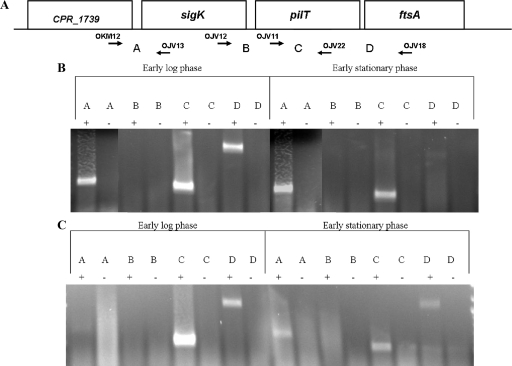

sigK is transcribed by readthrough from an upstream gene, and the sigK mutation does not prevent transcription of downstream genes.

The results shown in Fig. 4E, in which there was no transcription from the sigK promoter in the sigE mutant (KM2), seemed to contradict the results that we obtained by RT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3), in which there was appreciable sigK transcription in the sigE mutant. One possible explanation that could account for these results was that a transcript originating from the gene (CPR_1739) upstream of the sigK gene was reading through into the sigK gene. To determine if this was occurring and also to determine if the mutation we constructed in sigK affects transcription of downstream genes, we characterized transcripts from the region surrounding sigK using RT-PCR (Fig. 5A). RNA was extracted from C. perfringens SM101 and KM1 cultures during early log phase and early stationary phase in sporulation medium. We found that in SM101 there is a transcript that extends from CPR_1739 into sigK in both early-log and early-stationary-phase cells (Fig. 5B). As shown in Fig. 5A, the upstream primer, OKM12, lies in the coding region of CPR_1739. It hybridizes to DNA upstream of the region that was amplified during RT-PCR analysis of the sigK transcript (Fig. 3). This result provided an explanation for the RT-PCR product seen with the sigE mutant: it was actually derived from readthrough transcription from CPR_1739 into sigK and did not originate from the sigK promoter.

FIG. 5.

Transcription of genes in the sigK region in C. perfringens SM101 and KM1 (sigK mutant). (A) The location of genes surrounding the sigK gene. The letter “A” indicates the region between primers OKM12 and OJV13, “B” between OJV12 and OJV22, “C” between OJV11 and OJV22, and “D” between OJV11 and OJV18. Arrows indicate the locations where primers anneal in relation to the respective genes. RNA from C. perfringens SM101 (B) and KM1 (sigK mutant) (C) was harvested during early log (OD600 of 0.1) and early stationary phase (OD600 of 1.0), after inoculation into DSSM sporulation medium. Letters indicate which primer pairs were used in the reaction. + indicates reactions in which reverse transcriptase was added to the reaction, while − indicates negative controls in which reverse transcriptase was omitted. Products were viewed on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel.

There was no transcript detected by RT-PCR between the sigK and pilT genes (Fig. 5B), indicating that pilT is under the control of its own promoter. However, pilT, whose gene product is an ATPase necessary for type IV pilus-dependent motility in C. perfringens (69), is transcribed in early-log and stationary-phase cells of SM101 (Fig. 5B). It also seems that pilT and the downstream gene, ftsA, are cotranscribed in SM101, especially in early-log-phase cells. ftsA is upstream of ftsZ in strain SM101, and the two genes are located in an operon in B. subtilis (5).

RNA was extracted from cultures of C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) grown in sporulation medium during early log phase and early stationary phase, and transcripts of genes in the sigK region were analyzed (Fig. 5C). There was a very low level of a transcript spanning from CPR_1739 to sigK in early log phase and a somewhat higher level in early stationary phase, but less than in that of wild-type cells (Fig. 5B). As in C. perfringens SM101, no transcript was observed between sigK and pilT. Also, as in SM101, transcripts from pilT and spanning from pilT to ftsA were detected in early-log and stationary-phase cells, indicating that the mutation in the sigK gene does not prevent transcription of downstream genes and that σK-associated RNA polymerase is not required for transcription of pilT and ftsA.

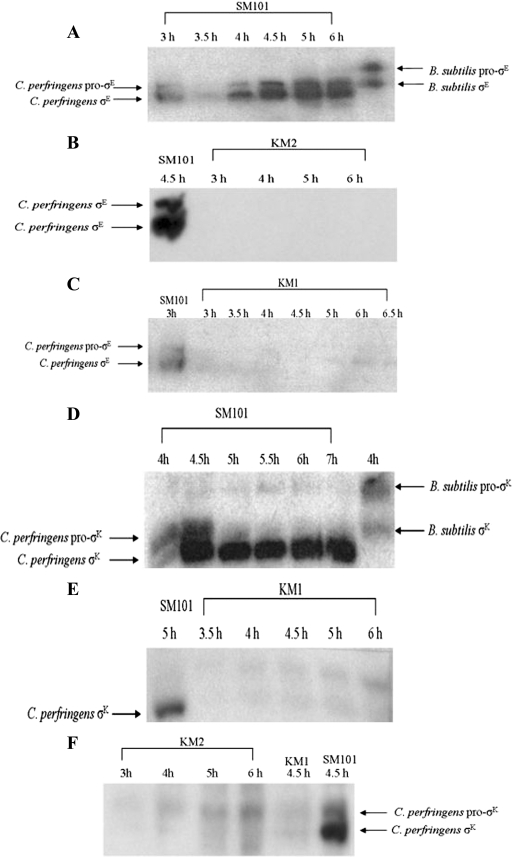

Pro-σE/σE and pro-σK/σK were not detected in C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant), and only a low level of pro-σK was observed with KM2 (sigE mutant).

In order to determine if mutations in the sigE and sigK genes abolished production of these proteins, samples were taken from cultures after inoculation into DSSM sporulation medium, and Western blot analyses were performed. Antibodies generated against B. subtilis pro-σE/σE were found to detect C. perfringens pro-σE/σE in strain SM101 at 3 h postinoculation (Fig. 6A), correlating with the mid-log phase of growth (data not shown). There was no pro-σE/σE detected in KM2 (sigE mutant) (Fig. 6B) or KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 6C). These results were expected, since no activity was detected from the spoIIGA promoter in KM2 (sigE mutant) or KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 4B) and very little sigE transcript was detected by RT-PCR (Fig. 3), which might be more sensitive than the gusA fusion or the immunoblotting.

FIG. 6.

Western blots of σE and σK in C. perfringens wild-type and mutant strains. Wild-type strain SM101 and mutant strains KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant) were inoculated into sporulation medium, and samples were collected over an 8-h time course. (A to C) Western blot analyses using anti-σE antibodies generated against B. subtilis σE were performed on the indicated strains. A B. subtilis sample served as a positive control when analyzing the C. perfringens SM101 blot. C. perfringens SM101 samples served as positive controls in blots analyzing σE in the mutant strains. (D to F) Western blot analyses using anti-σK antibodies generated against B. subtilis pro-σK were performed on the indicated strains. A B. subtilis sample served as a positive control when analyzing the C. perfringens SM101 blot. C. perfringens SM101 samples served as positive controls in blots when analyzing mutant strains. C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) was a negative control on the C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) blot.

Antibodies generated against B. subtilis pro-σK/σK were found to detect C. perfringens SM101 pro-σK/σK at 4 h postinoculation (Fig. 6D), correlating with the late log phase of growth (data not shown). By 5 h, almost all of the pro-σK had been processed to σK. There was no pro-σK/σK detected in KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 6E), but a very low level of pro-σK was observed in KM2 (sigE mutant) (Fig. 6F), consistent with our finding that the sigK transcript is present, albeit at a reduced level compared with that in strain SM101 (Fig. 3), presumably due to readthrough transcription from CPR_1739 (Fig. 5B). In agreement with the suggestion above that RT-PCR is more sensitive than immunoblotting, we note that the sigK transcript was readily detected in the sigE mutant strain (Fig. 3), but pro-σK was barely detectable in this strain (Fig. 6F).

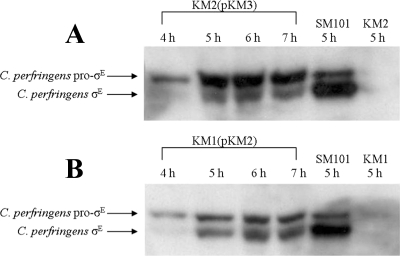

Pro-σE/σE is partially restored, but pro-σK/σK is not detectable in the complemented sigE mutant and sigK mutant strains.

In the complemented C. perfringens strains, KM2(pKM3) (complemented sigE mutant) and KM1(pKM2) (complemented sigK mutant), pro-σE was present at 4 h, with processing of pro-σE to active σE starting at 5 h after inoculation into sporulation media, but processing to σE and total σE levels were reduced in comparison to that seen in C. perfringens SM101 (Fig. 7). There was no pro-σK/σK detected in KM1(pKM2) or KM2(pKM3) (data not shown). Although σK was not restored to a detectable level in KM1(pKM2) or KM2(pKM3), presumably both strains make a very low level of σK, which allows the partial complementation of sporulation that we observed (Fig. 1). The failure to fully restore σE and σK synthesis may explain the observed partial complementation (see Discussion).

FIG. 7.

Western blots of pro-σE and σE in the complemented C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant) strains. C. perfringens strains KM2(pKM3) (complemented sigE mutant) and KM1(pKM2) (complemented sigK mutant) were inoculated into sporulation medium, and samples were collected over an 8-h time period. (A and B) Western blot analyses using anti-σE antibodies generated against B. subtilis σE were performed on the indicated strains. A C. perfringens SM101 sample served as a positive control. A C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) sample served as a negative control when analyzing the KM2(pKM3) (complemented sigE mutant) blot, while C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) served as a negative control on the KM1(pKM2) (complemented sigK mutant) blot.

SpoIIID is not regulated in C. perfringens in the same manner as it is in B. subtilis.

In the B. subtilis mother cell, in addition to σE and σK, SpoIIID is essential for gene regulation during sporulation, as it is a DNA-binding protein that activates transcription of the sigK gene (39). In B. subtilis, the transcription of spoIIID is directed by σE-associated RNA polymerase (31).

A SpoIIID ortholog, the CPR_2156 protein, exhibiting 62% identity to the SpoIIID protein of B. subtilis, was detected in the genomic sequence of C. perfringens strain SM101 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=genomeprj&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=12521). RT-PCR was performed to determine if the C. perfringens spoIIID gene is part of an operon with the upstream gene, CPR_2157, which codes for a putative peptidase. Primers were designed to hybridize to sequences in spoIIID and CPR_2157. An amplification product indicated that an RNA transcript was present, suggesting that spoIIID is transcribed from a promoter upstream of CPR_2157, sometime after early log phase (Fig. 8A). The spoIIID transcript was also detected in C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) and therefore is not under σE-associated RNA polymerase control (Fig. 8A), as it is in B. subtilis (31). The spoIIID transcript was also observed in the sigK mutant strain KM1 (Fig. 8A).

FIG. 8.

Analysis of spoIIID transcript and SpoIIID protein levels in C. perfringens wild-type and mutant strains. (A) After inoculation into sporulation medium, samples of the wild-type strain SM101 and mutant strains KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant) were collected during early log phase (E.L.) (OD600 of 0.1) and early stationary phase (E.S.) (OD600 of 1.0) and analyzed for the spoIIID transcript by RT-PCR. + indicated a reaction in which reverse transcriptase was added to the reaction, − indicates a negative control reaction in which reverse transcriptase was omitted. Products were viewed on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel. (B) C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) were inoculated into sporulation medium, and samples were collected over an 8-h time course. Western blot analysis using anti-SpoIIID antibodies generated against B. subtilis SpoIIID was performed on the samples. B. subtilis SpoIIID was used as a positive control.

Western blot analysis using antibodies directed against the B. subtilis SpoIIID protein indicated that SpoIIID in C. perfringens is expressed during sporulation of strains SM101, KM2 (sigE mutant), and KM1 (sigK mutant) during late log phase (Fig. 8B). We conclude that in C. perfringens SpoIIID is not under σE control, as it is in B. subtilis.

Both σE and σK are necessary for expression of the cpe gene.

In previous studies, Zhao and Melville (73) found that there are three promoters for cpe, and based on consensus recognition sequences for σE- and σK-associated RNA polymerase in B. subtilis, they are possibly σE- and σK-dependent in C. perfringens. Plasmids containing different segments spanning the cpe promoter region fused to the E. coli reporter gene gusA were described previously (Fig. 9A) (49, 73). These plasmids were transformed into C. perfringens strains SM101, KM1 (sigK mutant), and KM2 (sigE mutant) by electroporation, sporulation was induced by growing the cells in DSSM, and samples were removed to measure β-glucuronidase activity. The construct containing all three cpe promoters (pSM104) and the construct containing P1 and P2 (pSM127) produced similar levels of β-glucuronidase activity in SM101 (Fig. 9B and C). The construct containing only P3 (pSM170) exhibited 19% as much activity as the other two constructs (Fig. 9D). For all three cpe-gusA constructs, induction of β-glucuronidase activity occurred between 3 h and 4 h after inoculation into sporulation medium, when cells were between the mid-log and early stationary phases of growth (Fig. 9E). These results are similar to those reported previously (73) and suggest that most cpe transcription is derived from P1 and P2. However, there was no β-glucuronidase activity detected for pSM104, pSM127, or pSM170 in C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) or KM2 (sigE mutant) (Fig. 9B to D), indicating that σE and σK are needed for expression from all three cpe promoters.

FIG. 9.

Expression of cpe-gusA fusions in C. perfringens wild-type and mutant strains. (A) Schematic diagram of the C. perfringens cpe translational fusions to E. coli gusA. (B to D) Expression from the cpe promoters in the indicated plasmids was measured by the specific activity of β-glucuronidase in samples collected during an 8-h time period after inoculation of wild-type SM101 (squares) and mutants KM1 (sigK mutant) (diamonds) and KM2 (sigE mutant) (circles) into sporulation medium. (E) Representative growth curves of strains SM101 (squares), KM1 (sigK mutant) (diamonds), and KM2 (sigE mutant) (circles) containing pSM104 in sporulation medium (growth patterns with strains containing the other plasmids were very similar).

DISCUSSION

By making mutations in the C. perfringens sigE and sigK genes, we not only confirmed the hypothesis that cpe expression would depend on these sigma factors (73), we discovered that expression and function of these sigma factors are quite different than in B. subtilis. First, a sigK mutant is blocked earlier during the sporulation process than a sigE mutant in C. perfringens (Fig. 2), whereas the opposite is observed for B. subtilis (57). Consistent with the early block in the C. perfringens sigK mutant, sigF and sigE transcripts fail to accumulate normally (Fig. 3). Also, consistent with an early role of σK, we discovered that sigK is cotranscribed with an upstream gene during the early log phase of growth (Fig. 5). Moreover, sigF, sigE, and sigG transcripts also accumulate in the early log phase in C. perfringens, a second major difference from B. subtilis. A third important difference between the regulatory networks is that expression of a key mother cell transcription factor, SpoIIID, depends on σE-associated RNA polymerase in B. subtilis (31), but not in C. perfringens (Fig. 8). We speculate that these differences reflect different signals for initiation of sporulation by the two bacteria and the need for C. perfringens to rapidly produce spores in its ecological niches.

The sigE and sigK genes were mutagenized by insertion of a multimeric plasmid into the chromosomal copy of each gene. We found that KM2 (sigE mutant) and KM1 (sigK mutant) strains of C. perfringens produce less than 10 spores/ml. When complemented with wild-type copies of the spoIIGA-sigE and sigK genes, sporulation increased dramatically, 3,000- to 4,000-fold, but was not fully restored (1 to 2% efficiency compared with 80% efficiency for the wild-type strain) (Fig. 1). Repeated attempts were made to mutagenize the sigE and sigK genes by using transformation with monomeric forms of the plasmids and also transforming with large quantities (∼20 μg) of linearized DNA to enhance the frequency of allele replacement, but none of these experiments resulted in antibiotic-resistant colonies (data not shown). In the past, our group has constructed mutations in strain SM101 using allele replacement by homologous recombination methods (68), so the lack of transformants with anything except the multimeric form of the plasmids indicates that the sigE and sigK genes are relatively resistant to recombination events.

The similar complementation efficiencies of the C. perfringens sigE and sigK mutants (Fig. 1) were accompanied by partial rescue of σE production in both mutants (Fig. 7), but neither pro-σK nor σK was detected (data not shown). In the case of C. perfringens KM2(pKM3) (the complemented sigE mutant), the spoIIGA-sigE genes in pKM3 restored production of pro-σE, but processing of pro-σE to σE was delayed and reduced (Fig. 7A) compared with that seen with the wild-type strain (Fig. 6A). This may have been due to aberrant levels of expression of the putative protease, SpoIIGA, and its substrate, pro-σE, and the decreased level of σE may be insufficient for detectable production of pro-σK/σK, resulting in a lack of full complementation. For C. perfringens KM1(pKM2) (the complemented sigK mutant), pKM2 did not include the upstream gene CPR_1739, from which transcription reads through into sigK during the early log and early stationary phases (Fig. 5B). We attempted to clone both the CPR_1739 gene and sigK together in the vector used for complementation, but for unknown reasons, we were unable to obtain any such plasmids in E. coli. We hypothesize that the lack of sigK transcription from the upstream promoter accounts for the observed partial complementation of KM1 by pKM2 (Fig. 1). Specifically, production of σE was compromised (Fig. 7B). The decreased level of σE may be insufficient for detectable production of pro-σK/σK from pKM2, just as we propose it is insufficient for production of detectable pro-σK/σK from the chromosome in KM2(pKM3), resulting in a similar lack of full complementation (Fig. 1). Presumably, although σK was undetectable by immunoblotting, a small amount was made in these strains, allowing sporulation at low efficiency. While we favor this explanation and note that incomplete complementation of mutants made by plasmid insertion has been reported in several C. perfringens studies (54, 55, 59, 68), we cannot rule out the possibility that our results are due to an unknown secondary mutation.

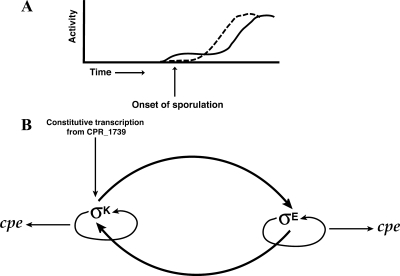

A mutation in the gene encoding σE in B. subtilis results in a disporic phenotype, in which asymmetric septa form at both cell poles (29). Our results demonstrate that a C. perfringens sigE mutant is blocked at a similar stage of development as a B. subtilis sigE mutant, stage II, as revealed by EM (Fig. 2 and Table 2). A mutation in the B. subtilis σK-encoding gene is characterized by the completion of engulfment, but spore development stops before spore cortex and spore coat can be added (57). Unexpectedly, a C. perfringens sigK mutant appeared to be blocked in sporulation at an earlier stage of development (stage 0) than the sigE mutant (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The block in sporulation appears to be earlier because of the lack of asymmetric septa and granules in the sigK mutant strain. How could σK be active before σE if the sigK promoter is dependent on a functional sigE gene (Fig. 4)? A model that can explain our results is shown in Fig. 10. We hypothesize that sigK expression is biphasic, with transcription from a promoter within or upstream of CPR_1739 (Fig. 5), providing in log and early stationary phases a low level of σK that is needed at an unknown early step in the sporulation process (Fig. 10A). After this early σK-dependent step, sigE is expressed in a σK-dependent step, and σE is then responsible for transcription of the sigK gene from the sigK promoter (Fig. 4), resulting in a high level of σK (Fig. 10A). However, because σE synthesis is dependent on σK activity and σE then directs a high level of both σK and σE synthesis later in sporulation, σE production and σK production are depicted as being codependent on each other, as shown in Fig. 10B.

FIG. 10.

Activity and regulation of σE and σK in C. perfringens. (A) Diagram of the proposed activity profile of σE (dashed line) and σK (solid line) during growth and sporulation of C. perfringens. (B) Model illustrating proposed regulation of σE, σK, and cpe in the mother cell compartment of C. perfringens. Arrows indicate positive regulation, which may be direct or indirect.

It is likely that in its early phase of activity at the onset of sporulation, σK is needed for functions other than just positively regulating transcription of the spoIIGA-sigE operon, since the sigK mutant has a different phenotype than does the sigE mutant (Fig. 2). The effect of σK on transcription of the spoIIGA-sigE operon may be indirect since our evidence suggests this operon is transcribed by σA-associated RNA polymerase with activation by (presumably phosphorylated) Spo0A.

Additional evidence in support of a role for σK early in sporulation comes from analysis of the transcript levels for sigF in C. perfringens. In B. subtilis, sigF is transcribed prior to asymmetric septum formation by σH-associated RNA polymerase, with activation by phosphorylated Spo0A (71). The phenotype of a B. subtilis sigF mutant is a disporic cell (57). C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) appears to be blocked in sporulation mostly at stage 0 (Fig. 2 and Table 2), indicating an early block at the morphological level, and the RT-PCR results show that accumulation of sigF transcripts is nearly eliminated in KM1 (Fig. 3), suggesting that σK acts prior to σF in the regulatory network that governs sporulation.

Interestingly, sigG transcripts accumulated in C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant), albeit accumulation was reduced and delayed, respectively (Fig. 3). The finding that sigG transcripts accumulated at all is somewhat surprising, since in B. subtilis the transcription of sigG depends on σF (33, 65) and σE (56), and we expect very little σF to be present in C. perfringens KM1 (given the low sigF transcript level), and no σE was detected in KM1 or KM2 (Fig. 6). The lack of stronger dependence of sigG transcription on σE in C. perfringens is clearly different from the B. subtilis paradigm, and another difference may be that sigG transcription does not depend on σF, although we cannot rule out the possibility that a small amount of σF in KM1 accounts for initial sigG transcription, which is followed by autoregulation (i.e., σG-directed transcription of sigG), which is observed in B. subtilis (64).

In B. subtilis, σA-associated RNA polymerase transcribes the spoIIGA-sigE operon, with activation by phosphorylated Spo0A (3, 20). Surprisingly, our gusA fusion results indicated that in C. perfringens, σE- and σK-associated RNA polymerase are both necessary for expression of the spoIIGA-sigE operon (Fig. 4). As additional evidence for this effect, Western blot analyses showed that pro-σE and σE were not detected in C. perfringens KM2 (sigE mutant) or KM1 (sigK mutant) (Fig. 6B and C). A very low level of sigE transcript was detected in KM1 (Fig. 3) but apparently is insufficient to produce a detectable level of pro-σE or σE (Fig. 6C). As depicted in our model (Fig. 10B), σE production depends on both σK and σE, but we do not know whether these directly recognize the spoIIGA-sigE promoter or indirectly affect σA-associated RNA polymerase or Spo0A.

The β-glucuronidase assays indicated that in C. perfringens, σE-associated RNA polymerase is necessary for expression from the sigK promoter (Fig. 4D and E), which is consistent with genetic analysis in B. subtilis (43, 51). The B. subtilis σE-associated RNA polymerase has been shown to transcribe from the sigK promoter in vitro, with activation by SpoIIID (22). We also observed that σK-associated RNA polymerase is necessary for the vast majority of transcription from the sigK promoter (Fig. 4D and E). While it appears from genetic studies that σK-associated RNA polymerase is responsible for about two-thirds of the sigK transcription in B. subtilis (43) and while in vitro studies demonstrate that σK-associated RNA polymerase can recognize the sigK promoter (39), expression of sigK in C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) was 100-fold lower than that in SM101 (Fig. 4D and E). Western blot analyses indicated that pro-σK and σK were not detectable in C. perfringens strains KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant) (Fig. 6E and F). The fact that pro-σK and σK were not detected in KM2 indicates that readthrough transcription from the CPR_1739 gene (Fig. 3 and 5) is insufficient to produce detectable levels of these proteins. Like production of σE, the production of a detectable level of σK depends on both σK and σE (Fig. 10B), and we do not know whether these directly recognize the sigK promoter, but readthrough transcription from the CPR_1739 gene presumably produces a small amount of σK that catalyzes codependent production of σE and σK at higher levels. Processing of pro-σK to σK presumably relies on the C. perfringens ortholog of B. subtilis spoIVFB, which in C. perfringens would need to be expressed during growth, unless another mechanism exists to generate a small amount of σK from the pro-σK produced by readthrough transcription from the CPR_1739 gene.

Another difference between the regulation of sporulation in B. subtilis and C. perfringens is the regulation of spoIIID. In B. subtilis, spoIIID transcription is absolutely dependent on σE-associated RNA polymerase (31, 42, 66). We found that in C. perfringens, the transcription of spoIIID is independent of σE-associated RNA polymerase and that spoIIID is cotranscribed with the upstream gene CPR_2157 (Fig. 8A). In B. subtilis, SpoIIID functions as an activator of sigK transcription (39, 43). Since we did not mutagenize the spoIIID gene in C. perfringens, we do not know if it regulates sigK transcription, but the lack of regulation of spoIIID by σE in C. perfringens suggests that SpoIIID plays a somewhat different role in this bacterium.

Results from the cpe promoter fusions to gusA in pSM240 indicate that expression of cpe is dependent on σE and σK (Fig. 9). This coincides with the fact that there was no sporulation detected in C. perfringens KM1 (sigK mutant) and KM2 (sigE mutant) and that enterotoxin production is always associated with sporulation (48). Although we have not provided direct biochemical evidence that σE- and σK-associated RNA polymerases are responsible for transcription of the three cpe promoters, our results support the hypothesis that this toxin gene is under direct control of these sigma factors.

The regulation of sporulation in B. subtilis has been well characterized. The evidence reported here indicates that the regulatory network is different in C. perfringens, both in the timing of sporulation and in the regulation of sporulation-specific sigma factors. Sporulation in B. subtilis does not occur until the cells have exhausted their nutrient supplies and entered stationary phase (57). Our results suggest that C. perfringens initiates sporulation as soon as early log phase, as seen by the presence of sigF, sigE, sigG, and sigK transcripts (Fig. 3) and by activation of the spoIIGA-sigE operon promoter (Fig. 4). Pro-σE is processed almost as soon as it is translated (Fig. 6A). Activation of the sigK promoter occurs during late log or early stationary phase (Fig. 4), about an hour later than that of the spoIIGA-sigE promoter, and the majority of pro-σK processing occurs during early stationary phase (Fig. 6D). These results show that σE becomes abundant before σK during sporulation; however, as discussed above, analyses of the phenotypes of the sigE and sigK mutants indicate that σK is actually active before σE, and this early σK activity is likely due to transcription originating from the upstream gene CPR_1739 (Fig. 5). Our findings support a model of codependent σE and σK production (Fig. 10B), and we hypothesize that C. perfringens sporulation is not regulated by levels of nutrients as much as it is by the environmental conditions that the bacterium finds itself in while still in exponential growth. It has been proposed that C. acetobutylicum initiates sporulation to survive the acidifying effects of its own fermentative metabolism (15), but this does not appear to be the case in C. perfringens. Clearly, C. perfringens has evolved a sporulation cycle that is characterized by the ability to rapidly produce a heat-resistant endospore, which likely plays an important role in the ability of the bacterium to be one of the most ubiquitous bacteria in all of nature (58).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge John Varga and Yuling Zhao for constructing some of the vectors used in this study and Kathy Lowe for assistance with the EM. We are grateful for the gift of monoclonal antibody against σE from William G. Haldenwang (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio).

This work was supported by grants 98-02844, 2000-02621, and 2003-35201-13580 from NRICGP/USDA awarded to S.B.M. and by grant GM43585 from the National Institutes of Health awarded to L.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 6 February 2009.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alsaker, K. V., and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2005. Transcriptional program of early sporulation and stationary-phase events in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 1877103-7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsaker, K. V., T. R. Spitzer, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2004. Transcriptional analysis of spo0A overexpression in Clostridium acetobutylicum and its effect on the cell's response to butanol stress. J. Bacteriol. 1861959-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldus, J. M., B. D. Green, P. Youngman, and C. P. Moran. 1994. Phosphorylation of Bacillus subtilis transcription factor Spo0A stimulates transcription from the spoIIG promoter by enhancing binding to weak 0A boxes. J. Bacteriol. 176296-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannam, T. L., and J. I. Rood. 1993. Clostridium perfringens-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors that carry single antibiotic resistance determinants. Plasmid 29233-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beall, B., and J. Lutkenhaus. 1991. FtsZ in Bacillus subtilis is required for vegetative and for asymmetric septation during sporulation. Genes Dev. 5447-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camp, A. H., and R. Losick. 2008. A novel pathway of intercellular signalling in Bacillus subtilis involves a protein with similarity to a component of type III secretion channels. Mol. Microbiol. 69402-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chary, V. K., P. Xenopoulos, and P. J. Piggot. 2007. Expression of the σF-directed csfB locus prevents premature appearance of σG activity during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1898754-8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czeczulin, J. R., R. C. Collie, and B. A. McClane. 1996. Regulated expression of Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin in naturally cpe-negative type A, B, and C isolates of C. perfringens. Infect. Immun. 643301-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duncan, C. L. 1973. Time of enterotoxin formation and release during sporulation of Clostridium perfringens type A. J. Bacteriol. 113932-936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan, C. L., G. J. King, and W. R. Frieben. 1973. A paracrystalline inclusion formed during sporulation of enterotoxin-producing strains of Clostridium perfringens type A. J. Bacteriol. 114845-859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan, C. L., and D. H. Strong. 1969. Experimental production of diarrhea in rabbits with Clostridium perfringens. Can. J. Microbiol. 15765-770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncan, C. L., and D. H. Strong. 1969. Ileal loop fluid accumulation and production of diarrhea in rabbits by cell-free products of Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 10086-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan, C. L., D. H. Strong, and M. Sebald. 1972. Sporulation and enterotoxin production by mutants of Clostridium perfringens. J. Bacteriol. 110378-391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duncan, L., and R. Losick. 1993. SpoIIAB is an anti-σ factor that binds to and inhibits transcription by regulatory protein σF from Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 902325-2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durre, P., and C. Hollergschwandner. 2004. Initiation of endospore formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum. Anaerobe 1069-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emeruwa, A. C., and R. Z. Hawirko. 1973. Poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate metabolism during growth and sporulation of Clostridium botulinum. J. Bacteriol. 116989-993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farquhar, R., and M. D. Yudkin. 1988. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of mutations in the spoIVC locus of Bacillus subtilis. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1349-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernández Miyakawa, M. E., V. Pistone Creydt, F. A. Uzal, B. A. McClane, and C. Ibarra. 2005. Clostridium perfringens enterotoxin damages the human intestine in vitro. Infect. Immun. 738407-8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujita, M., and R. Losick. 2002. An investigation into the compartmentalization of the sporulation transcription factor σE in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 4327-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gholamhoseinian, A., and P. J. Piggot. 1989. Timing of spoII gene expression relative to septum formation during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1715747-5749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halberg, R., and L. Kroos. 1992. Fate of the SpoIIID switch protein during Bacillus subtilis sporulation depends on the mother-cell sigma factor, σK. J. Mol. Biol. 228840-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halberg, R., and L. Kroos. 1994. Sporulation regulatory protein SpoIIID from Bacillus subtilis activates and represses transcription by both mother-cell-specific forms of RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 243425-436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haldenwang, W. G. 1995. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol. Rev. 591-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haraldsen, J. D., and A. L. Sonenshein. 2003. Efficient sporulation in Clostridium difficile requires disruption of the σK gene. Mol. Microbiol. 48811-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harris, L. M., N. E. Welker, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2002. Northern, morphological, and fermentation analysis of spo0A inactivation and overexpression in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. J. Bacteriol. 1843586-3597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilbert, D. W., and P. J. Piggot. 2004. Compartmentalization of gene expression during Bacillus subtilis spore formation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68234-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, I. H., and M. R. Sarker. 2006. Complementation of a Clostridium perfringens spo0A mutant with wild-type spo0A from other Clostridium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 726388-6393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iber, J. Clarkson, M. D. Yudkin, and I. D. Campbell. 2006. The mechanism of cell differentiation in Bacillus subtilis. Nature 441371-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Illing, N., and J. Errington. 1991. Genetic regulation of morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis: roles of σE and σF in prespore engulfment. J. Bacteriol. 1733159-3169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jonas, R. M., E. A. Weaver, T. J. Kenney, C. P. Moran, Jr., and W. G. Haldenwang. 1988. The Bacillus subtilis spoIIG operon encodes both σE and a gene necessary for σE activation. J. Bacteriol. 170507-511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones, C. H., and C. P. Moran. 1992. Mutant σ factor blocks transition between promoter binding and initiation of transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 891958-1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jones, S. W., C. J. Paredes, B. Tracy, N. Cheng, R. Sillers, R. S. Senger, and E. T. Papoutsakis. 2008. The transcriptional program underlying the physiology of clostridial sporulation. Genome Biol. 9R114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karmazyn-Campelli, C., C. Bonamy, B. Savelli, and P. Stragier. 1989. Tandem genes encoding σ-factors for consecutive steps of development in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 3150-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karmazyn-Campelli, C., L. Rhayat, R. Carballido-Lopez, S. Duperrier, N. Frandsen, and P. Stragier. 2008. How the early sporulation sigma factor σF delays the switch to late development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 671169-1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kellner, E. M., A. Decatur, and C. P. Moran, Jr. 1996. Two-stage regulation of an anti-sigma factor determines developmental fate during bacterial endospore formation. Mol. Microbiol. 21913-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kenney, T. J., and C. P. Moran. 1987. Organization and regulation of an operon that encodes a sporulation-essential sigma factor in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1693329-3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kominek, L. A., and H. O. Halvorson. 1965. Metabolism of poly-beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoin in Bacillus cereus. J. Bacteriol. 901251-1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroos, L. 2007. The Bacillus and Myxococcus developmental networks and their transcriptional regulators. Annu. Rev. Genet. 4113-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kroos, L., B. Kunkel, and R. Losick. 1989. Switch protein alters specificity of RNA polymerase containing a compartment-specific sigma factor. Science 243526-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroos, L., P. Piggot, and C. P. J. Moran. 2008. Bacillus subtilis sporulation and other multicellular behaviors, p. 363-383. In D. E. Whitworth (ed.), Myxobacteria: multicellularity and differentiation. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 41.Kroos, L., Y. T. Yu, D. Mills, and S. Ferguson-Miller. 2002. Forespore signaling is necessary for pro-σK processing during Bacillus subtilis sporulation despite the loss of SpoIVFA upon translational arrest. J. Bacteriol. 1845393-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kunkel, B., L. Kroos, H. Poth, P. Youngman, and R. Losick. 1989. Temporal and spatial control of the mother-cell regulatory gene spoIIID of Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 31735-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunkel, B., K. Sandman, S. Panzer, P. Youngman, and R. Losick. 1988. The promoter for a sporulation gene in the spoIVC locus of Bacillus subtilis and its use in studies of temporal and spatial control of gene expression. J. Bacteriol. 1703513-3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Löffler, A., and R. Labbe. 1986. Characterization of a parasporal inclusion body from sporulating, enterotoxin-positive Clostridium perfringens type A. J. Bacteriol. 165542-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Losick, R., and P. Stragier. 1992. Crisscross regulation of cell-type-specific gene expression during development in B. subtilis. Nature 355601-604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McClane, B. 2005. Clostridial enterotoxins. In P. Durre (ed.), Handbook on clostridia. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- 47.Mead, P. S., L. Slutsker, V. Dietz, L. F. McCaig, J. S. Bresee, C. Shapiro, P. M. Griffin, and R. V. Tauxe. 1999. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5607-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]