Abstract

Genome sequence information suggests that B12-dependent mutases are present in a number of bacteria, including members of the suborder Corynebacterineae like Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Corynebacterium glutamicum. We here functionally identify a methylmalonyl coenzyme A (CoA) mutase in C. glutamicum that is retained in all of the members of the suborder Corynebacterineae and is encoded by NCgl1471, NCgl1472, and NCgl1470. In addition, we observe the presence of methylmalonate in C. glutamicum, reaching concentrations of up to 757 nmol g (dry weight)−1 in propionate-grown cells, whereas in Escherichia coli no methylmalonate was detectable. As demonstrated with a mutase deletion mutant, the presence of methylmalonate in C. glutamicum is independent of mutase activity but possibly due to propionyl-CoA carboxylase activity. During growth on propionate, increased mutase activity has severe cellular consequences, resulting in growth arrest and excretion of succinate. The physiological context of the mutase present in members of the suborder Corynebacterineae is discussed.

Mutases catalyze carbon skeleton rearrangements involving a reversible conversion of a methylene into a methyl group via a methylene radical, and these enzymes use adenosylcobalamin as the cofactor for stabilization of the highly reactive radical intermediate (1). The enzyme is present in Sorangium cellulosum and Streptomyces species, for instance, and has attracted much attention to provide methylmalonyl coenzyme A (CoA) as an extender unit for polyketide synthesis (6). Methylmalonyl-CoA mutase is also present in humans, and its mutation, or mutations related to mutase activity, such as adenosylcobalamin synthesis or its transport, leads to methylmalonic aciduria, a rare disease that is fatal in the first year of life (2). Recently, a role for mutase activity in propionate utilization by Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been described. When propionate utilization via the methylcitrate cycle is impaired but cobalamin is added, then growth is dependent on mutAB encoding the β and α subunits of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (9). This route requires carboxylation of propionyl-CoA to yield succinyl-CoA via methylmalonyl-CoA mutase activity. M. tuberculosis belongs to the suborder Corynebacterineae, as does Corynebacterium glutamicum. The latter bacterium is apathogenic, is used for amino acid production (3), and also has genes suggesting the presence of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase activity (7). Since methylmalonyl-CoA mutase catalyzes an interesting carbon skeleton rearrangement reaction, we wanted to assess its activity and study possible physiological consequences of its presence.

To achieve this, a 5.148-kb chromosomal region of C. glutamicum containing predicted mutase α and β subunits (NCgl1471, NCgl1472), as well as a MeaB-encoding subunit (NCgl1470) overlapping the β subunit by 4 bp, was amplified via PCR with primers 5′-CGGTCGACAAGGAGATATAGATATGACTGATCTCACAAAGACTGC-3′ and 5′-CGGTCGACTTAGGCTTTGTCGAACGCCTCC-3′ and cloned as an EcoRI fragment to yield pEKExMut. The recombinant C. glutamicum pEKExMut and a control were grown on LB with 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) added. The mutase activity determined with crude extracts in assay mixtures consisting of 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 30 μM adenosylcobalamin, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.2 mM methylmalonyl-CoA was monitored by direct quantification of the succinyl-CoA formed via high-performance liquid chromatography (9). With C. glutamicum pEKExMut, this yielded a specific activity of 0.59 ± 0.16 μmol min−1 mg protein−1. Interestingly, even with the control, C. glutamicum pEKEx, a considerable activity of 0.19 ± 0.08 μmol min−1 mg protein−1 was present. By using plasmid pK19sacB-Δmut and two rounds of homologous recombination (10), the chromosomal region encompassing NCgl1470 to NCgl1472 was deleted to create C. glutamicum Δmut. With this strain, no mutase activity could be detected and also no growth phenotype was observed for this deletion mutant either in minimal medium with different carbon sources or in complex medium (data not shown).

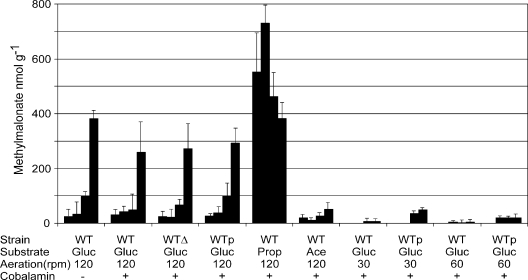

In a complementary approach, the presence of the branched carbon molecule of methylmalonyl-CoA was quantified as methylmalonate with an isotope dilution assay (6). In contrast to Escherichia coli, in which no methylmalonate could be detected (cells were grown on LB, and the detection limit was 5 nmol g [dry weight]−1), methylmalonate is present in C. glutamicum even during growth on salt medium CGXII with 4% glucose, notably in cells in the stationary phase, in which concentrations of 385 nmol g (dry weight)−1 are reached (Fig. 1). However, this was also the case with isogenic C. glutamicum strains Δmut and pEKExMut and this was also independent of adenosylcobalamin addition. Cells grown on CGXII with 2% acetate contained a lower concentration of 52 nmol methylmalonate g (dry weight)−1, whereas in cells grown on CGXII with 1% Na-propionate, considerably higher concentrations of up to 757 nmol g (dry weight)−1 were detected. Almost identical concentrations were obtained with C. glutamicum Δmut and pEKExMut when no cobalamin was added on either substrate (data not shown). When examined under conditions of diminished aeration, the methylmalonate content was greatly reduced to ≤20 nmol g (dry weight)−1 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, overexpression of the mutase genes resulted in significantly increased methylmalonate levels under conditions of reduced aeration. This might reflect a different citric acid cycle flux and formation of methylmalonyl-CoA from succinyl-CoA. This is consistent with the finding that succinate accumulated in the medium to 12 mM at 60 rpm and to 20 mM at 30 rpm, whereas it was absent at 120 rpm (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Methylmalonate contents of C. glutamicum grown under different conditions. Each set of four bars represents methylmalonate quantification from early-exponential, exponential, end-exponential, and stationary-phase cultures, respectively. The strains used were the wild type (WT) and the wild type with the three mutase genes deleted (WTΔ) or overexpressing them (WTp). The substrates used were glucose (Gluc), acetate (Ace), and propionate (Prop). Aeration of the cultivation flasks was as indicated (in revolutions per minute), and a plus sign indicates the addition of 0.1 mM cobalamin.

A possible source of methylmalonyl-CoA would be carboxylation of propionyl-CoA. We therefore directly assayed for propionyl- and acetyl-CoA activities (4). Significant activity was present in cells grown on propionate, acetate, or glucose, with rates of propionyl-CoA-related activities always higher than those assayed with acetyl-CoA (Table 1). Since the acetyl-CoA carboxylase enzyme of C. glutamicum exhibits the highest activity with acetyl-CoA (5), at least part of the activity might be due to the second acyl-CoA carboxylase present in all of the members of the suborder Corynebacterineae, which is specific for mycolic acid synthesis and which might also accept propionyl-CoA (4). The high concentration of methylmalonate in propionate-grown cells is expected to be due to a high propionyl-CoA concentration present during growth on this substrate, whereas the origin of propionyl-CoA or methylmalonyl-CoA, respectively, on acetate or glucose is unclear, since propionyl-CoA is not an intermediate during the utilization of these carbon sources.

TABLE 1.

Carboxylase activities in C. glutamicum grown on different substrates

| Carbon source | Mean sp act (μmol min−1 mg protein−1) ± SEM with following substrate:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA | Propionyl-CoA | |

| Glucose | 0.037 ± 0.003 | 0.066 ± 0.001 |

| Acetate | 0.012 ± 0.004 | 0.032 ± 0.003 |

| Propionate | 0.013 ± 0.004 | 0.016 ± 0.005 |

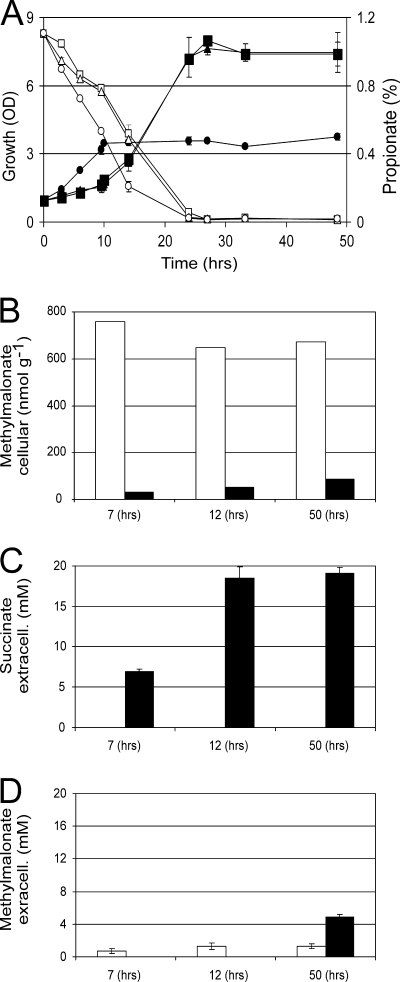

During the growth of C. glutamicum pEKExMut on 1% Na-propionate and with adenosylcobalamin present, we observed that initial growth and propionate consumption were faster than without vitamin addition (Fig. 2). However, after about 10 h, growth stopped, which was not the case for the control, suggesting severe consequences of mutase activity during propionate metabolism. Determination of methylmalonate content revealed a drastic reduction from 750 nmol g (dry weight)−1 to less than 35 nmol g (dry weight)−1 at 7 h when mutase was overexpressed and adenosylcobalamin was present (black bar in Fig. 2B). At the same time, succinate was accumulating in the medium, which was not the case without vitamin addition (black bar in Fig. 2B and C) or with the strain with the mutase gene deleted. It can thus be concluded that methylmalonyl-CoA is converted to succinyl-CoA, which is the favored direction of mutase activity (8). This supports the hypothesis that at the initial stages of propionate utilization succinyl-CoA is limiting, whereas at later growth stages a strong disbalance of metabolism due to the presence of methylmalonate and the presence of mutase activity exists. At all growth stages, significant concentrations of up to 5 mM methylmalonate were also observed in the medium.

FIG. 2.

Consequences of mutase activity during growth on propionate. Panels: A, growth of C. glutamicum pEKExMut without (▪) and with (•) 0.1 mM cobalamin and, as a control, growth of C. glutamicum Δmut with 0.1 mM cobalamin (▴); B, cellular methylmalonate; C, extracellular succinate; D, extracellular methylmalonate. The values in panels B, C, and D were derived from C. glutamicum pEKExMut without (open bars) and with (closed bars) 0.1 mM cobalamin at three different time points during cultivation. OD, optical density.

The methylmalonyl-CoA mutase gene locus in all of the members of the suborder Corynebacterineae, including Mycobacterium leprae, with its decayed genome, is strictly retained and largely syntenic. Despite the influence of mutase activity on propionate metabolism in C. glutamicum and M. tuberculosis (9), its major function is probably not known. It could well be related to the high concentration of methylmalonate found in C. glutamicum, which was not observed before in any other bacterium.

Acknowledgments

We thank Evonik and A. Marx and M. Pötter for support of L.B., as well as R. Müller and M. W. Ring from the Universität des Saarlandes, Germany, for methylmalonate quantifications.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 20 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buckel, W., C. Kratky, and B. T. Golding. 2005. Stabilisation of methylene radicals by cob(II)alamin in coenzyme B12 dependent mutases. Chemistry 12352-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deodato, F., S. Boenzi, F. M. Santorelli, and C. Dionisi-Vici. 2006. Methylmalonic and propionic aciduria. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 142C104-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eggeling, L., and M. Bott (ed.). 2005. Handbook of Corynebacterium glutamicum. CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL.

- 4.Gande, R., K. J. Gibson, A. K. Brown, K. Krumbach, L. G. Dover, H. Sahm, S. Shioyama, T. Oikawa, G. S. Besra, and L. Eggeling. 2004. Acyl-CoA carboxylases (accD2 and accD3), together with a unique polyketide synthase (Cg-pks), are key to mycolic acid biosynthesis in Corynebacterianeae such as Corynebacterium glutamicum and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 27944847-44857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gande, R., L. G. Dover, K. Krumbach, G. S. Besra, H. Sahm, T. Oikawa, and L. Eggeling. 2007. The two carboxylases of Corynebacterium glutamicum essential for fatty acid and mycolic acid synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1895257-5264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross, F., M. W. Ring, O. Perlova, J. Fu, S. Schneider, K. Gerth, S. Kuhlmann, A. F. Stewart, Y. Zhang, and R. Müller. 2006. Metabolic engineering of Pseudomonas putida for methylmalonyl-CoA biosynthesis to enable complex heterologous secondary metabolite formation. Chem. Biol. 131253-1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalinowski, J., B. Bathe, D. Bartels, N. Bischoff, M. Bott, A. Burkovski, N. Dusch, L. Eggeling, B. J. Eikmanns, L. Gaigalat, A. Goesmann, M. Hartmann, K. Huthmacher, R. Kramer, B. Linke, A. C. McHardy, F. Meyer, B. Mockel, W. Pfefferle, A. Puhler, D. A. Rey, C. Ruckert, O. Rupp, H. Sahm, V. F. Wendisch, I. Wiegrabe, and A. Tauch. 2003. The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of l-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J. Biotechnol. 1045-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michenfelder, M., W. E. Hull, and J. Rétey. 1987. Quantitative measurement of the error in the cryptic stereospecificity of methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. Eur. J. Biochem. 168659-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savvi, S., D. F. Warner, B. D. Kana, J. D. McKinney, V. Mizrahi, and S. S. Dawes. 2008. Functional characterization of a cobalamin-dependent methylmalonyl pathway in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for propionate metabolism during growth on fatty acids. J. Bacteriol. 1903886-3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schäfer, A., A. Tauch, W. Jäger, J. Kalinowski, G. Thierbach, and A. Pühler. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 14569-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]