Abstract

Retroviruses like human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), as well as many other enveloped viruses, can efficiently produce infectious virus in the absence of their own surface glycoprotein if a suitable glycoprotein from a foreign virus is expressed in the same cell. This process of complementation, known as pseudotyping, often can occur even when the glycoprotein is from an unrelated virus. Although pseudotyping is widely used for engineering chimeric viruses, it has remained unknown whether a virus can actively recruit foreign glycoproteins to budding sites or, alternatively, if a virus obtains the glycoproteins through a passive mechanism. We have studied the specificity of glycoprotein recruitment by immunogold labeling viral glycoproteins and imaging their distribution on the host plasma membrane using scanning electron microscopy. Expressed alone, all tested viral glycoproteins were relatively randomly distributed on the plasma membrane. However, in the presence of budding HIV-1 or Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) particles, some glycoproteins, such as those encoded by murine leukemia virus and vesicular stomatitis virus, were dramatically redistributed to viral budding sites. In contrast, the RSV Env glycoprotein was robustly recruited only to the homologous RSV budding sites. These data demonstrate that viral glycoproteins are not in preformed membrane patches prior to viral assembly but rather that glycoproteins are actively recruited to certain viral assembly sites.

In order for an infectious enveloped virus particle to assemble, the viral surface glycoproteins must traffic to the precise location in the plasma membrane where viral budding occurs. If surface glycoproteins from a foreign virus are present within the virus-producing cell, these foreign proteins in some cases can traffic to the viral budding site to form a phenotypically mixed viral particle referred to as a pseudotyped virus (1, 6, 20, 30). Because the resulting chimeric viruses do not carry the genetic material to produce the foreign glycoprotein, they display the foreign phenotype only for a single round of their life cycle. Pseudotyped viruses were first described over 50 years ago (6), and researchers from numerous fields have capitalized on this knowledge to manipulate viral specificity for gene delivery to cells. Despite the widespread use of this technique, the mechanism that facilitates pseudotyping remains a mystery, and there has been no adequate explanation for why only certain viruses can complement one another.

Viruses from the Retroviridae family can produce chimeric pseudotyped viruses with some surface glycoproteins from other retroviruses as well as from viruses belonging to entirely different viral families. Retroviruses encode a single structural protein, Gag, which in most cases can assemble into viral particles and bud from the cell in the absence of all other viral proteins. The surface glycoprotein of retroviruses is a single type I transmembrane protein known as envelope (Env), which is synthesized independently of Gag and incorporated into budding virions at the plasma membrane. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) lacking its own Env has been reported to be complemented efficiently by the surface proteins from some viruses, such as murine leukemia virus (MLV) Env and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G) (12, 16); less efficiently by others, such as Rous sarcoma virus (RSV) Env (10); and almost not at all by still others, such as gibbon ape leukemia virus Env (3, 24). These glycoproteins show no obvious conserved sequence domain that might dictate these patterns. For instance, MLV Env and gibbon ape leukemia virus Env behave differently but are from the same retroviral genus and have about 50% amino acid similarity. In contrast, MLV Env and VSV-G Env behave similarly but are from different viral families and have no sequence similarity.

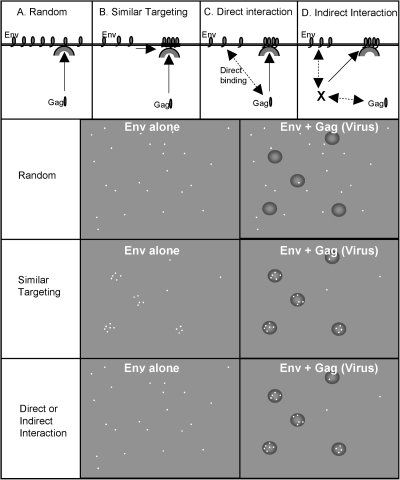

Four models have been proposed that might explain the pseudotyping phenomenon (Fig. 1). The first model, random incorporation, proposes that all cellular surface proteins that are not sterically excluded will be passively incorporated into viral particles. In support of this hypothesis, expression of cellular membrane proteins in a foreign host (such as human CD4 in quail cells) or expression of cellular membrane proteins with truncated cytoplasmic tails (such as truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor) results in increased incorporation of the protein into viral particles (7, 28). If random incorporation is responsible for viral pseudotyping, one would expect viral surface proteins to be randomly distributed on the surface of cells in the presence and absence of assembling virus (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

Four models for viral pseudotyping. Overview of the four potential mechanisms for pseudotyping. (A) Random interaction. (B) Similar targeting. (C) Direct interaction. (D) Indirect interaction. Images at the top show a cross-section of the plasma membrane for each of these models. Images in the center and right show the expected surface glycoprotein distribution in the absence and presence of assembling virus, respectively. Viral glycoproteins are depicted as white dots; viral assembly sites are depicted as darkened circles.

The second model to explain pseudotyping, similar targeting, proposes that all the viral structural and surface proteins are independently targeted to specific microdomains on the plasma membrane, such as detergent-resistant lipid microdomains, commonly called lipid rafts (Fig. 1B). It has been proposed that lipid rafts serve as assembly sites for some viruses and that this common assembly site could facilitate viral pseudotyping (1, 17, 19). In a recent report it was shown that HIV-1 assembles quantally with either HIV-1 Env or Ebola glycoprotein within a single cell but that particles with mixtures of these glycoproteins particles do not form. This was interpreted to mean that assembly occurs on a single lipid raft (9). To date, no studies have demonstrated any correlation between raft association and efficient viral Env incorporation. In fact, one of the most commonly used viral surface proteins in pseudotyping, VSV-G, is not raft associated (21). If similar targeting is responsible for viral pseudotyping, one would expect viral surface proteins to be nonrandomly distributed on the surface of cells in the presence and absence of assembling virus (Fig. 1B).

The third model, direct interaction, proposes that viral structural proteins directly contact viral glycoproteins and recruit them to assembly sites (Fig. 1C). Evidence for this model has accumulated in several systems. A well-characterized example is between HIV-1 Gag and HIV-1 Env. HIV-1 Env fusogenic activity is negatively regulated by immature Gag protein in budded virions, suggesting a direct interaction (27). Several mutations in HIV-1 Gag and HIV Env block HIV-1 Env incorporation into viruses (4, 13, 25). Further, an Env mutation that blocks incorporation can be compensated for by a mutation in Gag, suggesting a direct interaction between these proteins (15). However, this interaction probably does not play a role in the recruitment of foreign viral glycoproteins. Many mutations in HIV-1 Gag that block HIV-1 Env incorporation do not block the incorporation of foreign viral glycoproteins (4, 13, 25). Further, many viral glycoproteins, such as VSV-G, are incorporated into HIV-1 particles but contain no sequence similarity with HIV-1 Env. If direct interaction is responsible for viral pseudotyping, one would expect viral surface proteins to be randomly distributed on the surface of cells in the absence of virus but redistributed to viral budding sites in the presence of assembling virus (Fig. 1C).

The final model to explain pseudotyping, indirect interaction, proposes that the viral structural and surface proteins interact through a cellular intermediate (Fig. 1D). In support of this notion, it has recently been shown that HIV-1 Gag and HIV-1 Env interact with a cellular protein, TIP-47, and that this protein is required for efficient HIV-1 Env incorporation into viruses (11). However, TIP-47 was not required for incorporation of foreign viral glycoproteins, and so this protein is not likely to be a universal intermediate. As with direct interaction, if indirect interaction is responsible for viral pseudotyping, one would expect viral surface proteins to be randomly distributed on the surface of cells in the absence of virus but redistributed to viral budding sites in the presence of assembling virus (Fig. 1D).

This report utilizes a novel imaging technique to investigate the mechanism of recruitment of native and nonnative surface glycoproteins to viral budding sites. By imaging the plasma membrane distribution of immunogold-labeled surface glycoproteins in the presence or absence of budding retroviral particles, we demonstrate that expression of Gag results in a dramatic recruitment of certain surface glycoproteins on the plasma membrane to viral budding sites but not others. Furthermore, parallel infectivity assays suggest that this redistribution correlates with efficient pseudotyping and infectious virus production. We hypothesize that the observed active recruitment utilizes a previously unrecognized cellular component to facilitate an indirect interaction between the structural protein and the surface glycoprotein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The chicken fibroblast cell line DF1 was maintained as previously described (8). The human 293 TVA cell line (10) was generously provided by John Young and maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen). Transient transfections were performed using FuGENE (Roche Diagnostics), Optifect (Invitrogen), or Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen), per the manufacturers’ instructions.

Vectors.

The RSV Schmidt-Ruppin A Env expression vector pCB6.SR-A was generously provided by Eric Hunter and Christina Ochsenbauer-Jambor (18). The RSV Env gene was subcloned into the vector pIRES2-DsRed-Express (Clontech) to provide fluorescent expression in transfected cells. The RSV Env with the C-terminal domain-deleted (ΔCTD) construct was engineered with the last 29 amino acids of RSV Env deleted by adding a stop codon after amino acid I578 using standard cloning techniques. The yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged Friend MLV Env expression vector was generously provided by Walther Mothes (23). The VSV-G expression vector was obtained through the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program (2). The late-domain-defective RSV Gag (PPPY→AAAA) or HIV-1 Gag (PTAP→AAAA) were previously described (8). The infectious RSV proviral construct RCAS.GFP, which encodes the gene for green fluorescent protein, eGFP, in place of src, was generously provided by Stephen Hughes. The RCAS.GFP-Tomato vector was created by deleting the N-terminal half of the RSV Env gene and introducing a cytomegalovirus (CMV)-driven tdTomato gene (22) into the vector outside the proviral genome. The pNL4-3.GFP-Tomato vector was derived from an NL4-3 provirus generously provided by Vineet KewalRamani with deletions removing vpr, vpu, the C-terminal portion of vif, and the N-terminal portion of env and a gene replacement of the nef gene with eGFP. This vector was further modified by inserting the CMV-tdTomato gene into the vector outside the proviral genome (22).

SEM.

DF1 cells were plated on photoetched coverslips (Mattek) or coverslips coated with a gold pattern (finder grids) and transfected using FuGENE (Roche Diagnostics) or Optifect (Invitrogen) per the manufacturers’ instructions. Transfected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and immunolabeled with mIgG1 8C5 anti-RSV Env primary antibody generously provided by Eric Hunter and Christina Ochsenbauer-Jambor (18); anti-GFP clone GFP-20 (Sigma) primary antibody; or monoclonal anti-VSV clone P5D4 (Sigma), primary antibody, and 10 nm gold-labeled anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Fc) AuroProbe secondary antibody (Amersham). For cells transfected with VSV-G, all steps were performed in 0.1% Triton to increase access to the cytoplasmic tail of VSV-G. Following being immunolabeled, cells were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde, dehydrated in ethanol, critical point dried, and coated with carbon. Secondary and backscatter scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of transfected cells were obtained using a Hitachi S-4700 FE-SEM at 5 kV at the University of Missouri electron microscopy facility or a Keck FE-SEM at the Cornell University Center for Materials Research. Enrichment was calculated by dividing the density of gold particles at budding sites by the density of gold particles at nonbudding sties. Virus-associated density was calculated by counting the number of gold nanoparticles associated with virus and dividing it by the total viral surface area including the surface underneath the assembly site (n5πr2, where n is the number of viruses and r is 70 nm). Nonviral density was calculated by counting the number of gold nanoparticles not associated with virus and dividing it by the total nonviral surface area (total surface area = nπr2, where n is the number of viruses and r is 70 nm). For each condition, at least 10 images were quantitated.

Single-cycle infectivity assay.

DF1 or 293 TVA(10) cells were transfected with the RCAS.GFP-Tomato or pNL4-3.GFP-Tomato proviral vector with or without the glycoprotein expression vector. For HIV-1 experiments, the transfected 293 TVA cells were mixed with a ninefold excess of untransfected cells 6 h after transfection. Forty-eight hours posttransfection, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences). The gate for transfected cells was set to exclude negative cells and to include cells exhibiting fluorescence in the absence of surface glycoprotein. The gate for infected cells was set to include cells that exhibit a positive shift in the eGFP (FL1) channel. In cases where the transfected and infected gates overlapped, the overlap region was excluded from both gates.

RESULTS

To investigate whether glycoprotein incorporation into budding virus occurs via an active or passive recruitment mechanism, we imaged the change in surface glycoprotein distribution in the presence or absence of viral budding using correlative SEM with gold immunolabeling and backscatter electron detection. Correlative SEM is an imaging technique by which individual cells are imaged in tandem, first by fluorescence microscopy and then by SEM (8). Individual retroviral budding sites can be easily identified in SEM secondary electron images due to their distinct spherical appearance when release-defective (late-domain-deficient) viral constructs are utilized (8). An additional dimension is added to this process by labeling surface proteins with gold nanoparticles, which can be imaged using backscatter electron imaging. Although the gold particles can generally be seen in secondary or backscatter images, their identity is unambiguous in backscatter images.

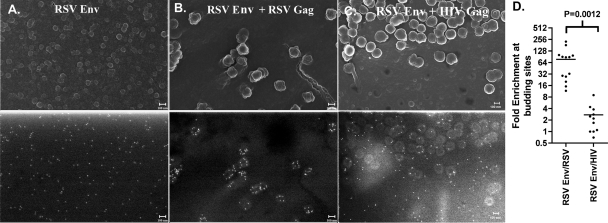

We began by observing the distribution of the surface glycoprotein from RSV (the prototypical alpharetrovirus) in the presence and absence of the budding virus particles. Cells were plated on glass coverslips containing a finder grid and transfected with combinations of vectors expressing RSV Env and retroviral Gag proteins. In all cases, a trace amount of a fluorescent protein was expressed along with the viral proteins to identify transfected cells. The location of individual transfected cells was plotted on the finder grid using fluorescent microscopy, and then the RSV Env glycoprotein was immunolabeled with 10 nm gold. Following processing for SEM, the same cells were located on the finder grid, and secondary SEM images (Fig. 2, top panels) and backscatter images (Fig. 2, bottom panels) of the cell surface were obtained. In all cases the nontransfected cells were imaged to verify the specificity of the gold label (data not shown). In cells that expressed only RSV Env, the gold-labeled protein was distributed across the plasma membrane in a nearly random pattern (Fig. 2A). However, when a vector expressing RSV Gag was included in the transfection, the distribution of RSV Env changed dramatically, with gold particles observed almost exclusively at RSV budding sites (Fig. 2B). To investigate whether RSV Env recruitment was viral species specific, we examined the distribution of RSV Env relative to HIV-1 budding sites. HIV-1 Gag and RSV Env are known to pseudotype poorly together (10). In the presence of HIV-1 Gag, we observed little if any enrichment of RSV Env from the HIV-1 Gag-derived budding sites (Fig. 2C). The distribution of Env in at least 10 images from each pairing was quantitated, and the difference in enrichments at the two types of viral budding sites was statistically significant (Fig. 2D).

FIG. 2.

RSV Env is enriched in RSV Gag budding sites but not HIV-1 Gag budding sites. DF1 chicken fibroblast cells transfected with RSV Schmidt-Ruppin A Env (A) expression vector alone (18) or cotransfected with late-domain-defective RSV Gag (B) or HIV-1 Gag (C) expression vectors (8). Top images are secondary electron images that show the surface topography, and bottom images are backscatter images that show the distribution of gold nanoparticles. The small (∼10 nm) bumps apparent in the secondary electron images of some cells are either gold particles or small coating artifacts. Scale bars indicate 100 nm. The enrichment at budding sites was calculated for at least 10 images, as described in Materials and Methods. These data are expressed as a scatter plot in which each point is the calculated enrichment in a single image (D).

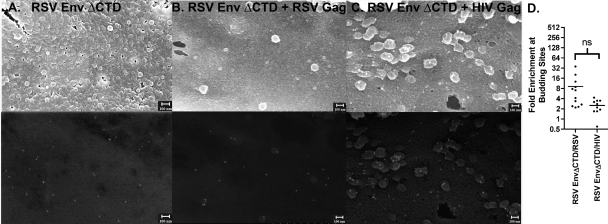

If the active recruitment of RSV Env to RSV budding sites is the result of a direction interaction, this interaction would necessarily have to be between RSV Gag and the cytoplasmic tail of RSV Env. However, it was reported previously that an RSV provirus whose Env protein lacked a cytoplasmic tail remained infectious (18a). To determine if the cytoplasmic tail of RSV Env was required for recruitment to RSV budding sites, we engineered a stop codon immediately after the membrane-spanning domain (RSV Env ΔCTD), exactly as was previously described, and confirmed that this protein could still functionally lead to the production of infectious virus (data not shown). Next we analyzed the distribution of RSV Env ΔCTD by SEM. As with the wild-type Env, RSV Env ΔCTD was randomly distributed on the plasma membrane in the absence of viral budding (Fig. 3A). In the presence of budding RSV particles there was significantly less recruitment to RSV assembly sites (P = 0.0018) (Fig. 3B). Deletion of the cytoplasmic tail did not noticeably change the distribution of RSV Env relative to HIV-1 budding sites (Fig. 3C). There was also no apparent correlation between the Env expression level and recruitment (data not shown). Although RSV Env ΔCTD appeared to maintain a modest enrichment at RSV assembly sites, this enrichment was not significantly more than that at HIV-1 assembly sites (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Deletion of the RSV Env ΔCTD reduces enrichment at RSV budding sites. DF1 chicken fibroblast cells transfected with RSV Schmidt-Ruppin A Env ΔCTD (A) expression vector alone (18) or cotransfected with late-domain-defective RSV Gag (B) or HIV-1 Gag (C) expression vectors (8). Top images are secondary electron images that show the surface topography, and bottom images are backscatter images that show the distribution of gold nanoparticles. Scale bars indicate 100 nm. The enrichment at budding sites is expressed as a scatter plot (D). ns, not statistically different.

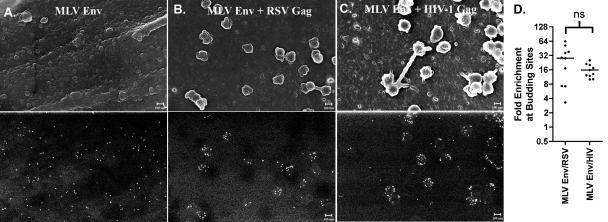

Some other retroviral glycoproteins, such as MLV Env, efficiently form pseudotypes with retroviruses of different genera (12). To ascertain whether this pseudotyping is random, we repeated the SEM assay using an MLV Env expression vector. Like RSV Env, MLV Env expressed alone displayed nearly random distribution on the plasma membrane (Fig. 4A). In contrast, MLV Env was redistributed to both RSV and HIV-1 budding sites (Fig. 4B and 4C). In both cases, the enrichment at viral budding sites was greater than 10-fold (Fig. 4D), supporting the hypothesis that at least in some cases viral pseudotyping is an active process.

FIG. 4.

RSV and HIV-1 Gag actively recruit MLV Env to budding sites during viral pseudotyping. DF1 cells were transfected with a YFP-tagged Friend MLV Env (A) expression vector alone (23) or cotransfected with late-domain-defective RSV Gag (B) or HIV-1 Gag (C) expression vectors (8). Top images are secondary electron images that show the surface topography, and bottom images are backscatter images that show the distribution of gold particles. Scale bars indicate 100 nm. The enrichment at budding sites is expressed as a scatter plot (D). ns, not statistically different.

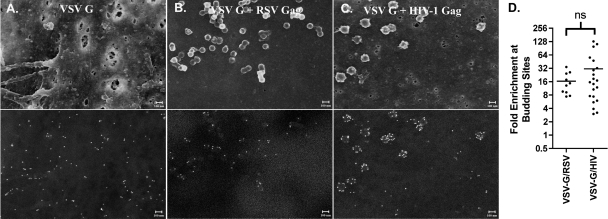

We carried out similar experiments with the nonretroviral surface glycoprotein VSV-G, which efficiently forms pseudotypes with retroviruses (16, 29). Again, the distribution of VSV-G alone was nearly random (Fig. 5A). (In rare cases, VSV-G was localized to tubular cellular structures that could be observed on the cell surface in the secondary SEM image [data not shown].) In contrast, VSV-G was found concentrated at both RSV and HIV-1 budding sites (Fig. 5B and C). This result implies active recruitment, even for this glycoprotein from a different family of viruses.

FIG. 5.

VSV-G is actively recruited to both RSV and HIV-1 Gag budding sites. DF1 cells were transfected with a VSV-G expression vector (16) alone (A) or cotransfected with late-domain-defective RSV Gag (B) or HIV-1 Gag (C) expression vectors (8). Top images are secondary electron images that show the surface topography, and bottom images are backscatter images that show the distribution of gold particles. Scale bars indicate 100 nm. The enrichment at budding sites is expressed as a scatter plot (D). ns, not statistically different.

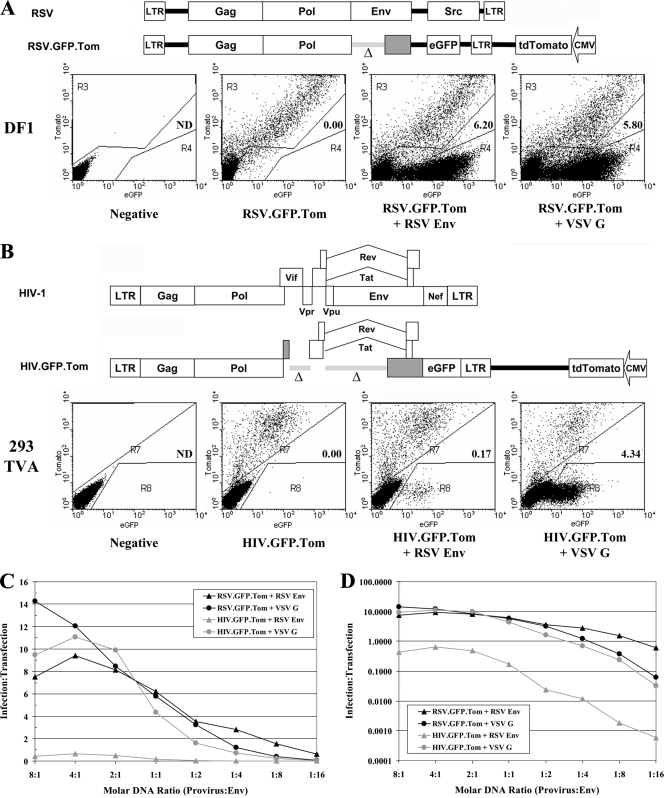

To assess the relevance of the SEM results for infectivity, we developed a parallel single-cycle infectivity assay to compare infectious virus production of HIV-1 (strain NL4-3) and RSV (strain RCAS) with different viral glycoproteins. The gene for green fluorescent protein (eGFP) was introduced in place of a nonessential gene in each provirus (src for RSV and nef for HIV-1). The gene for the red fluorescent protein tdTomato (22), under the control of a CMV promoter, was inserted into the same vectors but outside of the proviral DNA (Fig. 6). Cells that were transfected with these vectors thus appeared both red and green by flow cytometry, while any cells infected de novo with virus derived from the transfection appeared green only. In both proviruses, deletions in the Env genes ensured that de novo infections could occur only when vectors expressing pseudotype-competent viral surface proteins were introduced into the same cell. The infectivity assays were internally controlled based on the number of cells that were transfected, and the output was taken as the ratio of infected to transfected cells (I/T ratio) after 48 h.

FIG. 6.

Active recruitment of surface glycoproteins enhances viral infectivity. (A) Schematic of the RSV (RCAS) parent and modified proviruses used for single-cycle infectivity assay (top). The Δ indicates the deleted sequence, and grayed genes are no longer expressed. DF-1 cells (bottom) were transfected with the modified provirus alone or at a 1:1 ratio with the denoted glycoprotein. Transfected (gate R3) and infected (gate R4) cells were enumerated, and the I/T ratio is indicated on each dot plot. (B) Schematic is same as that shown in panel A, top, except the HIV-1 provirus pNL4-3 with the 293 TVA (10) cell line and gates R7 (transfected) and R8 (infected) are shown. (C) Modified proviruses were cotransfected with decreasing molar ratios of glycoprotein expression vectors, and the output was expressed as the number of infected/transfected cells. (D) Representation is same as that shown in panel C, except the y axis is expressed in log form.

To assess viral infectivity, the RSV or HIV-1 proviral vector was cotransfected with different viral glycoprotein genes, and the cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. In cells transfected with proviral DNA and no glycoprotein DNA, all of the fluorescent cells expressed both eGFP and tdTomato (Fig. 6A and 6B, bottom, second panels). However, when the cells were cotransfected with viral glycoprotein expression vectors, many eGFP-only cells resulting from de novo infections were also observed (Fig. 6A and 6B, bottom, third and fourth panels). De novo infections were observed with all of the virus/glycoprotein combinations assayed, but the I/T ratio was much higher among pairs that exhibited active recruitment by the SEM assay (compare HIV-1 with RSV Env to HIV-1 with VSV-G; Fig. 6B, third and fourth panels). These data suggest that active recruitment is important for viral infectivity, presumably because active recruitment leads to higher concentrations of Env in viral particles.

To further assess how the incorporation mechanism affects viral infectivity, we compared the infectivity of the proviruses in the presence of decreasing molar ratios of viral surface glycoproteins. The graphs in Fig. 4C and 4D depict the infectivity (I/T ratio) that resulted when proviruses were cotransfected with different molar ratios of viral glycoprotein expression vectors. Both linear and log infectivity curves were generated for all combinations of provirus and glycoprotein (Fig. 4C and D). The RSV provirus combined with RSV Env or VSV-G exhibited a similar curve. However, the HIV-1 provirus exhibited much lower infectivity with RSV Env than with VSV-G. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that decreased infectivity of RSV Env with HIV-1 is due to poor Env incorporation.

DISCUSSION

There are four potential mechanisms to explain how viruses achieve the incorporation of viral surface proteins into budding viral particles. Although it has been shown previously that many viral surface glycoproteins are enriched in foreign viral particles, the mechanism of how this enrichment occurs has remained a mystery. A determination of whether this enrichment is active (Env is redistributed to budding sites) or passive (Env and Gag traffic to the same microdomains) has been difficult to achieve because either mechanism could result in enrichment in viral particles. Using an imaging technique that characterizes the distribution of viral glycoproteins in the presence or absence of budding virus particles, we have been able to address how enrichment occurs. Our imaging data show conclusively that viral pseudotyping can occur by multiple mechanisms.

Random incorporation.

This model implies that the surface glycoprotein on the plasma membrane is neither recruited to nor excluded from viral particles. RSV Env appears to be randomly incorporated into HIV-1 particles, albeit inefficiently, and this incorporation can lead to infectious viral particles. RSV Env ΔCTD also appears to be randomly incorporated into HIV-1 particles. Thus, random incorporation does appear to be a mechanism that gives rise to pseudotyping in certain situations.

Similar targeting.

None of the viral glycoproteins studied displayed a distinct clustering at the plasma membrane in the absence of viral assembly, so it could be concluded that similar targeting, at least with these three glycoproteins, does not occur. However, this study did not address the distribution of surface glycoproteins in the cell relative to other membranes. It could be argued that trafficking to the plasma membrane itself is similar targeting, even if the incorporation into viral particles once it reaches the plasma membrane is passive. In single-round infectivity experiments, RSV Env ΔCTD was able to efficiently complement Env-defective RSV, despite displaying limited recruitment to RSV budding sites (Fig. 2; data not shown). It has been shown previously (10) that this deletion in RSV Env increased pseudotyping efficiency when coupled with HIV-1. These data would be consistent with the cytoplasmic tail deletion reducing active recruitment to viral budding sites while increasing the amount of random incorporation by increasing the steady-state concentration of Env at the plasma membrane. It will be interesting to determine whether cytoplasmic tail deletion mutants of other viral glycoproteins, such as those that have been described for HIV-1 Env and simian immunodeficiency virus Env (5, 14, 26), are able to be actively recruited to viral budding sites.

If similar targeting is not utilized by viruses to recruit their glycoproteins, it is difficult to explain why HIV-1 Env and Ebola GP package quantally into HIV-1 particles, as was recently demonstrated (9). It is possible that HIV-1 recruits its own glycoprotein by a direct and active mechanism and Ebola GP by an indirect mechanism, but this model would not explain why Ebola GP is excluded from HIV-1 Env-containing particles. It is possible that similar targeting does occur with these glycorproteins. Alternatively, the two glycoproteins could exist in distinct microdomains that do not mix but that can both be recruited to HIV-1 assembly sites. It will be interesting to determine if these glycoproteins exist in preformed patches on the plasma membrane.

Direct interaction.

The data presented here are consistent with a model that a direct interaction between viral structural and surface glycoproteins occurs in some situations. Because RSV Env is exclusively recruited to RSV budding sites and because this recruitment is dependent on the RSV Env cytoplasmic tail, the interaction between RSV Env and RSV Gag is likely direct. An indirect interaction cannot be excluded, but if the interaction is indirect, the intermediate would have to be an RSV-specific intermediate.

Indirect interaction.

By process of elimination, the promiscuous viral glycoproteins VSV-G and MLV Env appear to be recruited to viral budding sites by an indirect interaction. Because these surface glycoproteins are randomly distributed when expressed alone but highly clustered at viral budding sites when virus is present (Fig. 4 and 5), the incorporation must be active. However, these viral glycoproteins, which both have short cytoplasmic tails, are recruited to divergent HIV-1 and RSV budding sites, and yet there is no similarity among any of the cytoplasmic tails. It is unlikely that there are cryptic binding sites in these two cytoplasmic tails that can be recognized by these two unrelated viruses. Thus, indirect interaction does appear to be a mechanism used to facilitate pseudotyping in certain situations.

Although these data point to an indirect interaction facilitating the recruitment of MLV Env and VSV-G to viral budding sites, they do not offer a clue as to the identity of the intermediate. While a cellular trafficking protein like the ones that have been described in other situations are appealing models, the intermediate could also be an extracellular scaffolding protein, a virus-specific saccharide sequence, or a membrane microdomain which is clustered by the assembling virus. Future studies analyzing the specific domains in Gag and Env required for this recruitment should help identify the cellular intermediate.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Hunter, C. Ochsenbauer-Jambor, W. Mothes, V. KewalRamani, S. Hughes, J. Young, and the NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program for materials.

This research was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI73098 to M.C.J. and CA20081 to V.M.V. and by a grant from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation to M.C.J.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 February 2009.

REFERENCES

- 1.Briggs, J. A., T. Wilk, and S. D. Fuller. 2003. Do lipid rafts mediate virus assembly and pseudotyping? J. Gen. Virol. 84757-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang, L. J., V. Urlacher, T. Iwakuma, Y. Cui, and J. Zucali. 1999. Efficacy and safety analyses of a recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 derived vector system. Gene Ther. 6715-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christodoulopoulos, I., and P. M. Cannon. 2001. Sequences in the cytoplasmic tail of the gibbon ape leukemia virus envelope protein that prevent its incorporation into lentivirus vectors. J. Virol. 754129-4138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freed, E. O., and M. A. Martin. 1995. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J. Virol. 691984-1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabuzda, D. H., A. Lever, E. Terwilliger, and J. Sodroski. 1992. Effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain on biological functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 663306-3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granoff, A., and G. K. Hirst. 1954. Experimental production of combination forms of virus. IV. Mixed influenza A-Newcastle disease virus infections. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 8684-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henriksson, P., T. Pfeiffer, H. Zentgraf, A. Alke, and V. Bosch. 1999. Incorporation of wild-type and C-terminally truncated human epidermal growth factor receptor into human immunodeficiency virus-like particles: insight into the processes governing glycoprotein incorporation into retroviral particles. J. Virol. 739294-9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larson, D. R., M. C. Johnson, W. W. Webb, and V. M. Vogt. 2005. Visualization of retrovirus budding with correlated light and electron microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10215453-15458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung, K., J. O. Kim, L. Ganesh, J. Kabat, O. Schwartz, and G. J. Nabel. 2008. HIV-1 assembly: viral glycoproteins segregate quantally to lipid rafts that associate individually with HIV-1 capsids and virions. Cell Host Microbe 3285-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis, B. C., N. Chinnasamy, R. A. Morgan, and H. E. Varmus. 2001. Development of an avian leukosis-sarcoma virus subgroup A pseudotyped lentiviral vector. J. Virol. 759339-9344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Verges, S., G. Camus, G. Blot, R. Beauvoir, and C. Berlioz-Torrent. 2006. Tail-interacting protein TIP47 is a connector between Gag and Env and is required for Env incorporation into HIV-1 virions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10314947-14952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lusso, P., F. di Marzo Veronese, B. Ensoli, G. Franchini, C. Jemma, S. E. DeRocco, V. S. Kalyanaraman, and R. C. Gallo. 1990. Expanded HIV-1 cellular tropism by phenotypic mixing with murine endogenous retroviruses. Science 247848-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mammano, F., E. Kondo, J. Sodroski, A. Bukovsky, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1995. Rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein mutants by envelope glycoproteins with short cytoplasmic domains. J. Virol. 693824-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manrique, J. M., C. C. Celma, J. L. Affranchino, E. Hunter, and S. A. Gonzalez. 2001. Small variations in the length of the cytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein drastically affect envelope incorporation and virus entry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 171615-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami, T., and E. O. Freed. 2000. Genetic evidence for an interaction between human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and alpha-helix 2 of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 743548-3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naldini, L., U. Blomer, P. Gallay, D. Ory, R. Mulligan, F. H. Gage, I. M. Verma, and D. Trono. 1996. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science 272263-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen, D. H., and J. E. Hildreth. 2000. Evidence for budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 selectively from glycolipid-enriched membrane lipid rafts. J. Virol. 743264-3272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochsenbauer-Jambor, C., S. E. Delos, M. A. Accavitti, J. M. White, and E. Hunter. 2002. Novel monoclonal antibody directed at the receptor binding site on the avian sarcoma and leukosis virus Env complex. J. Virol. 767518-7527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18a.Perez, L. G., G. L. Davis, and E. Hunter. 1987. Mutants of the Rous sarcoma virus envelope glycoprotein that lack the transmembrane anchor and cytoplasmic domains: analysis of intracellular transport and assembly into virions. J. Virol. 612981-2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickl, W. F., F. X. Pimentel-Muinos, and B. Seed. 2001. Lipid rafts and pseudotyping. J. Virol. 757175-7183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin, H. 1965. Genetic control of cellular susceptibility to pseudotypes of Rous sarcoma virus. Virology 26270-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheiffele, P., A. Rietveld, T. Wilk, and K. Simons. 1999. Influenza viruses select ordered lipid domains during budding from the plasma membrane. J. Biol. Chem. 2742038-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaner, N. C., P. A. Steinbach, and R. Y. Tsien. 2005. A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 2905-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sherer, N. M., M. J. Lehmann, L. F. Jimenez-Soto, A. Ingmundson, S. M. Horner, G. Cicchetti, P. G. Allen, M. Pypaert, J. M. Cunningham, and W. Mothes. 2003. Visualization of retroviral replication in living cells reveals budding into multivesicular bodies. Traffic 4785-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stitz, J., C. J. Buchholz, M. Engelstadter, W. Uckert, U. Bloemer, I. Schmitt, and K. Cichutek. 2000. Lentiviral vectors pseudotyped with envelope glycoproteins derived from gibbon ape leukemia virus and murine leukemia virus 10A1. Virology 27316-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang, C. T., Y. Zhang, J. McDermott, and E. Barklis. 1993. Conditional infectivity of a human immunodeficiency virus matrix domain deletion mutant. J. Virol. 677067-7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilk, T., T. Pfeiffer, and V. Bosch. 1992. Retained in vitro infectivity and cytopathogenicity of HIV-1 despite truncation of the C-terminal tail of the env gene product. Virology 189167-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wyma, D. J., J. Jiang, J. Shi, J. Zhou, J. E. Lineberger, M. D. Miller, and C. Aiken. 2004. Coupling of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 fusion to virion maturation: a novel role of the gp41 cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 783429-3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young, J. A., P. Bates, K. Willert, and H. E. Varmus. 1990. Efficient incorporation of human CD4 protein into avian leukosis virus particles. Science 2501421-1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zavada, J. 1972. VSV pseudotype particles with the coat of avian myeloblastosis virus. Nat. New Biol. 240122-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zavada, J. 1982. The pseudotypic paradox. J. Gen. Virol. 6315-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]