Abstract

Purpose

To determine if incorporation of an additional cytotoxic agent improves overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) for women with advanced-stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) and primary peritoneal carcinoma who receive carboplatin and paclitaxel.

Patients and Methods

Women with stages III to IV disease were stratified by coordinating center, maximal diameter of residual tumor, and intent for interval cytoreduction and were then randomly assigned among five arms that incorporated gemcitabine, methoxypolyethylene glycosylated liposomal doxorubicin, or topotecan compared with carboplatin and paclitaxel. The primary end point was OS and was determined by pairwise comparison to the reference arm, with a 90% chance of detecting a true hazard ratio of 1.33 that limited type I error to 5% (two-tail) for the four comparisons.

Results

Accrual exceeded 1,200 patients per year. An event-triggered interim analysis occurred after 272 events on the reference arm, and the study closed with 4,312 women enrolled. Arms were well balanced for demographic and prognostic factors, and 79% of patients completed eight cycles of therapy. There were no improvements in either PFS or OS associated with any experimental regimen. Survival analyses of groups defined by size of residual disease also failed to show experimental benefit in any subgroup.

Conclusion

Compared with standard paclitaxel and carboplatin, addition of a third cytotoxic agent provided no benefit in PFS or OS after optimal or suboptimal cytoreduction. Dual-stage, multiarm, phase III trials can efficiently evaluate multiple experimental regimens against a single reference arm. The development of new interventions beyond surgery and conventional platinum-based chemotherapy is required to additionally improve outcomes for women with advanced EOC.

INTRODUCTION

After cytoreductive surgery, advanced-stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma (EOC) initially appears chemotherapy sensitive, as response rates to platinum-based therapy exceed 80%. However, long-term survival remains poor as a result of recurrence and emergence of drug resistance.

Although platinum-based agents (ie, cisplatin or carboplatin) and taxanes remain the core of primary treatment, clinical trials have incorporated other cytotoxic agents, including topotecan, gemcitabine, and methoxypolyethylene glycosylated liposomal doxorubicin (PLD). Each agent has well-defined activity in the setting of recurrent EOC, including in platinum-resistant populations. Both topotecan and PLD are US Food and Drug Administration–approved as single agents for management of recurrent EOC.1,2 Gemcitabine is US Food and Drug Administration–approved for management of recurrent, platinum-sensitive EOC in combination with carboplatin, but it is also utilized as a single agent.3

Multiple international, phase III trials were considered to evaluate emerging regimens that were fostered by collaborative development through the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG). A multiarm, multistage design to evaluate four different experimental arms against a single reference arm was proposed by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) in the United States and by the Medical Research Council (MRC) in the United Kingdom (MRC-UK), which represents the International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm (ICON) group. With a target accrual of 4,000 patients, GOG0182-ICON5 emerged as the largest prospective treatment trial in EOC. In addition to clinical outcomes, the study would also provide an international clinical research database, including outcomes in patients with uncommon histologies and genetic mutations associated with cancer risk.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Objectives

The primary objective was to compare the efficacy of each experimental arm against the reference arm (ie, carboplatin and paclitaxel) on the basis of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Evaluation of toxicities, complications, dose intensity, and cumulative dose delivery would also be described for each regimen.

Patient Selection

Eligible patients submitted tissue to confirm histologic diagnosis (EOC or primary peritoneal carcinoma [PPC]) and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics stage (III or IV), with either optimal (≤ 1 cm) or suboptimal residual disease. Pathology materials were reviewed by each participating regional group and were subject to routine centralized audit. Patients were also required to have a GOG performance status of ≤ 2; absolute neutrophil count ≥ 1,500/μL, platelets ≥ 100,000/μL, creatinine ≤ 1.5× institutional upper limit normal (ULN), bilirubin ≤ 1.5× ULN, AST and alkaline phosphatase ≤ 2.5× ULN, and baseline sensory or motor neuropathy grade 1 or lower according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.

Patients who had tumors of low malignant potential, with carcinosarcoma, or with nonepithelial tumors were not eligible. Patients who had personal histories of breast cancer were eligible, provided that they were disease free for at least 3 years without contraindications for protocol-based chemotherapy. Patients who had early-stage synchronous endometrial cancer were also eligible, provided there was no more than minimum invasion without high-grade features. All patients provided written informed consent consistent with government and institutional requirements, including local institutional review board approval, before receiving protocol therapy.

Participating Groups

Primary coordination was provided by GOG in collaboration with GCIG and included the Australia and New Zealand Gynecologic Oncology Group (Camperdown, Australia), MRC-UK (London, United Kingdom), and Istituto Mario Negri (Milan, Italy). Each international group utilized a regional office for registration, random assignment, data management, and quality assurance monitoring. Collaborating organizations within the United States also included the Southwest Oncology Group and five other groups managed through the Clinical Trials Support Unit of the National Cancer Institute (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participation From International Cooperative Groups

| Enrollment Data | Cooperative Group Coordinating Center |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANZGOG | GOG | IMN | MRC-UK | SWOG | NCI-Other* | |

| First enrollment date | June 22, 2002 | February 7, 2001 | October 30, 2003 | July 22, 2002 | October 23, 2001 | June 24, 2002 |

| Total No. of patients in enrollment | 184 | 3,435 | 67 | 363 | 198 | 65 |

Abbreviations: ANZGOG, Australia and New Zealand Gynecologic Oncology Group; GOG, Gynecologic Oncology Group; IMN, Istituto Mario Negri; MRC-UK, Medical Research Council in the United Kingdom; SWOG, Southwest Oncology Group; NCI, National Cancer Institute.

Includes patients enrolled from the following: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG; n = 24), North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG; n = 23), Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB; n = 12), National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP; n = 1), Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG; n = 1), Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG; n = 1), and Other (n = 3).

Treatment Plan

After registration and stratification, patients were randomly allocated to one of five arms (Table 2). Each arm included eight cycles of triplet or sequential-doublet chemotherapy, which provided a minimum of four cycles that incorporated experimental treatments while maintaining at least four cycles with carboplatin and paclitaxel.

Table 2.

CONSORT

| Variable | Treatment Arm |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (Reference) | II | III | IV | V | |

| Chemotherapy dose and schedule | |||||

| Carboplatin, C 1-4 | AUC 6 D1 | AUC 5 D1 | AUC 5 D1 | AUC 5 D3 | AUC 6 D8 |

| Paclitaxel, C 1-4 | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | — | — |

| Gemcitabine, C 1-8 | — | 800 mg/m2 D1,8 (30 minutes) | — | — | — |

| Gemcitabine, C 1-4 | — | — | — | — | 1,000 mg/m2/d D1,8 |

| PLD, C 1, 3, 5, 7 | — | — | 30 mg/m2 D1 | — | — |

| Topotecan, C 1-4 | — | — | — | 1.25 mg/m2/d D1,2,3 | — |

| Carboplatin, C 5-8 | AUC 6 D1 | AUC 5 D1 | AUC 5 D1 | AUC 6 D1 | AUC 6 D1 |

| Paclitaxel, C 5-8 | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) | 175 mg/m2 D1 (3 hours) |

| No. of patients | |||||

| Randomly assigned | 864 | 864 | 862 | 861 | 861 |

| Ineligible after review* | 45 | 49 | 39 | 39 | 40 |

| Received no treatment† | 1 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 7 |

| Discontinued | |||||

| Toxicity or refusa | 73 | 120 | 95 | 51 | 83 |

| Progression or death | 58 | 42 | 65 | 58 | 44 |

NOTE. The intent-to-treat analysis included all registered and randomly assigned patients (eligible and ineligible). Chemotherapy regimens in treatment arms were as follows: I, carboplatin + paclitaxel; II, carboplatin + paclitaxel + gemcitabine; III, carboplatin + paclitaxel + doxorubicin; IV, carboplatin + topotecan then carboplatin + paclitaxel; V, carboplatin + gemcitabine then carboplatin + paclitaxel.

Abbreviations: C, cycle; AUC, area under the concentration-time curve; D, day; PLD, methoxypolyethylene glycosylated liposomal doxorubicin.

Ineligible patients (N = 212) included 83 patients with insufficient pathology material to document eligibility, 43 with inappropriate histology, 22 with inadequate staging surgery, 22 with ineligible primary tumor site, 21 with ineligible stage, 14 with second primary site, and seven ineligible for other reasons.

Treatment information unavailable for 11 patients.

Patients with suboptimal residual disease were permitted to undergo interval cytoreductive surgery between the fourth and fifth cycles, provided that intent was declared at registration and that patients met criteria for cytoreductive surgery. Reassessment (ie, second-look) laparotomy for patients in complete clinical remission at the conclusion of chemotherapy was not permitted, because this has not been shown to provide clinical benefit, and because surgical assessment of small-volume disease could interfere with determination of PFS.4

Additional chemotherapy, including maintenance or consolidation, was not permitted until there was evidence of progressive disease. However, GCIG-based international criteria for determination of progression that used serial measurements of serum CA-125 were permitted, which allowed initiation of secondary therapies before large-volume or symptomatic recurrence.5

Regimen Selection

Dose and schedule were designed to maximize delivery of newer agents while preserving exposure to carboplatin and paclitaxel and equilibrating the risk of hematologic toxicity. Prophylactic hematopoietic growth factors were not required, and initial modifications for hematologic toxicity relied on cycle delay and/or dose reduction, with addition of growth factors for management of recurrent toxicity. These decisions were based on practical aspects of conducting an international cooperative group trial as well as on the cumulative risks of carboplatin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Gemcitabine was evaluated in two experimental arms, as a triplet combination in eight cycles, and as a sequential doublet in four cycles, administered on days 1 and 8. Multicycle feasibility of the triplet regimen was established from phase I studies among previously untreated patients.6 In the doublet regimen, to maximize dosing and to minimize the risk of hematologic toxicity, carboplatin was delayed until day 8 on the basis of evidence of sequence-dependent toxicity in patients with lung cancer.7

Topotecan was administered as part of a doublet regimen on days 1, 2, and 3, and carboplatin was delayed until day 3. This sequence was selected because of evidence of sequence-dependent hematologic toxicity in phase I trials in previously untreated patients.8 A triplet combination with topotecan, carboplatin, and paclitaxel was not feasible because of cumulative hematologic toxicity. A tolerable triplet regimen has been described with cisplatin, but this would have changed the overall trial design.9

PLD has prolonged clearance because of polyethylene glycol and liposomal encapsulation. In pilot studies, dosing every 3 weeks was associated with an unacceptable risk of mucosal, skin, and/or hematologic toxicity. Overall tolerability was improved when PLD was administered as a triplet regimen on alternate cycles.10

Statistical Design

Stratified block random assignment was used to balance treatment assignments within coordinating center, residual disease status, and intention for interval-debulking surgery. Annual accrual was estimated to be 1,000 patients, with 50% accrued from collaborating groups. The estimated median time to progression or death for women with advanced-stage EOC who were receiving carboplatin and paclitaxel was 15 months, and estimated median survival was 36 months. OS and PFS were assessed from the date of random assignment in all patients on the basis of an intent-to-treat principle, and death as a result of any cause was considered a failure event. The date of last contact was used to calculate a censored time at risk for patients without documented progression (PFS) or for those who had no reported death (OS).

An event-triggered interim analysis (IA) was scheduled to occur after 240 PFS events (ie, progression or death) in the reference arm. The purpose of the interim analysis was to eliminate regimens that demonstrated insufficient evidence of activity.11 The IA included pairwise PFS comparisons between the reference arm and each of the experimental arms (ie, four comparisons) by using a stratified log-rank test.12 A regimen was deemed worthy of second-stage accrual if the observed relative PFS event rate was at least 7% lower than the reference arm. If second-stage accrual was indicated, additional patients would be registered with random assignment to the reference arm and to each selected experimental regimen. The final analysis consisted of a pairwise comparison of OS between the reference arm and each experimental regimen and was scheduled to occur when at least 365 deaths were reported among all of the patients registered to the reference arm.12 This sample size provided a 90% chance of declaring a regimen superior if the regimen truly reduced the death rate by 25% compared with the reference arm; the type I error was limited to .0125 (.05/4; two-tail test) for each pairwise comparison.13 This effect size is comparable to an increase in the expected proportion that survives more than 3 years from 50% to 59.3%.

Adverse events considered at least possibly related to treatment were categorized, graded, and reported according to National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 2.0. Emerging adverse event and routine toxicity reports were reviewed by regional study chairs and were summarized twice yearly in conjunction with semiannual GOG meetings; minor amendments to clarify protocol therapy and supportive care were considered. In addition, international members were recruited for a study-specific data safety and monitoring committee that was charged with ongoing review of safety reports and was empowered to recommend study closure, as appropriate, on the basis of the results of the IA and other scheduled or unscheduled reports. For the purpose of this report, only patients who received at least some of their assigned treatment are included in the summaries of adverse events.

RESULTS

The study was activated in January 2001, and the first patient was enrolled in February 2001 (Table 1). The planned interim analysis of PFS occurred when there were 272 events (ie, progression or death) on the reference arm and 1,345 cumulative events among 3,836 patients (data freeze on May 2004). Deaths that were potentially treatment-related occurred in less than 1% of patients without clustering on any particular arm. None of the experimental regimens reduced the PFS event rate at least 7% relative to the reference arm. Therefore, in accordance with prespecified guidelines, the study was closed to additional accrual in September 2004. At that time, a total of 4,312 patients were enrolled, which included 212 patients who did not fulfill all eligibility criteria upon retrospective review (Table 2).

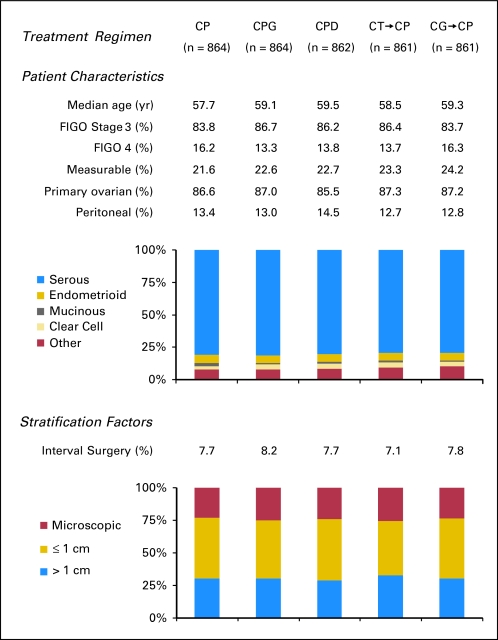

Demographic, stratification, and prognostic factors were well balanced among treatment arms (Fig 1). Of note, consistent with current surgical trends, 70% of women who were registered had optimal cytoreduction, and less than 25% of women had measurable residual disease. Overall, 79% of women completed eight cycles of the assigned therapy.

Fig 1.

Patient demographic characteristics, prognostic factors (including stage, histology, and measurable disease), and stratification parameters (including maximal residual disease and intent to perform interval cytoreductive surgery). FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; CPG, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine; CPD, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin; CT→CP, carboplatin plus topotecan, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel; CG→CP, carboplatin plus gemcitabine, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel.

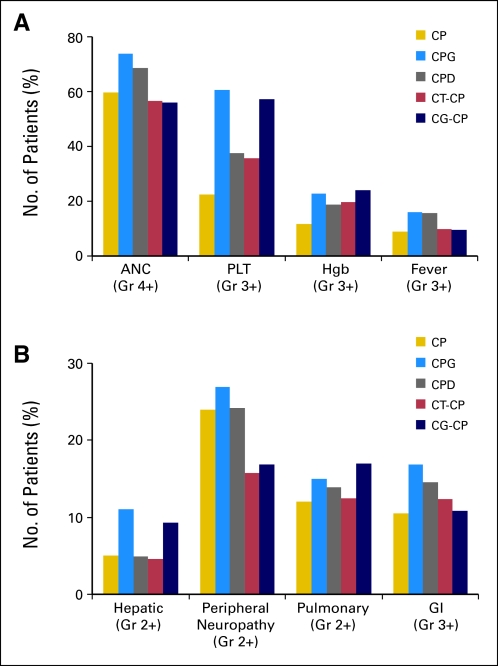

There was increased hematologic toxicity in the triplet regimens and increased thrombocytopenia in both arms with gemcitabine (Fig 2A). Neuropathy was decreased in the doublet regimens (Fig 2B), which included only four cycles of paclitaxel. Transient elevations of transaminases were more commonly observed in arms with gemcitabine, but they were generally without clinical impact. There was no significant increase in pulmonary toxicity associated with gemcitabine.

Fig 2.

Clinically important (A) hematologic and (B) nonhematologic toxicities. A Pearson χ2 test to assess the null hypothesis (ie, the probability of adverse events is independent of treatment) was statistically significant at P < .005 for grade 4 and worse neutropenia (absolute neutrophils count [ANC]) and thrombocytopenia (platelets [PLT]); grade 3 or worse hemoglobin (Hgb), infection/fever (fever), and GI toxicity; and grade 2 or worse peripheral neuropathy, pulmonary, and hepatic toxicity. CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; CPG, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine; CPD, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin; CT-CP, carboplatin plus topotecan, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel; CG-CP, carboplatin plus gemcitabine, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel.

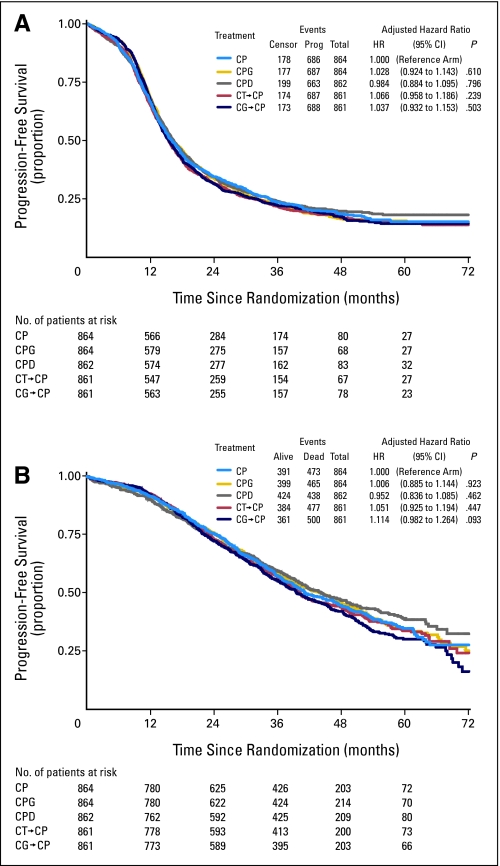

The primary analysis of OS and an updated analysis of PFS are reported here. The median duration of follow-up among those women alive at last contact is 3.7 years. Relative to the reference arm, the adjusted risk of first progression or death (PFS) ranged from 0.984 to 1.066 for the experimental regimens (Fig 3A). The adjusted relative risks of death ranged from 0.952 to 1.114 (Fig 3B). There was no statistically significant difference in either PFS or OS associated with any of the experimental regimens compared with the eight cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel, which achieved a median PFS of 16.0 months and a median OS of 44.1 months for the entire study population, including those patients with optimal and suboptimal residual disease. Incremental end points and proportion of progressions determined by CA-125 were also similar for all regimens (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Fig 3.

Estimates of (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival for each treatment arm, including the cumulative number of events, the number of patients at risk, and a summary of hazard ratios; P values were adjusted for extent of residual disease and participating cooperative group. Median progression-free survival rates varied from 15.4 to 16.4 months, and median overall survival rates varied from 39.6 to 44.2 months. CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; CPG, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine; CPD, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin; CT-CP, carboplatin plus topotecan, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel; CG-CP, carboplatin plus gemcitabine, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel.

An exploratory analysis of hazard ratios (HRs) for survival on the basis of diagnosis (EOC v PPC), age (< 65 v ≥ 65 years), stage (III v IV), histology (grade 1, 2, 3, v clear-cell), or participating group failed to disclose any evidence of differential benefit from experimental therapy in any subgroup (data not shown).

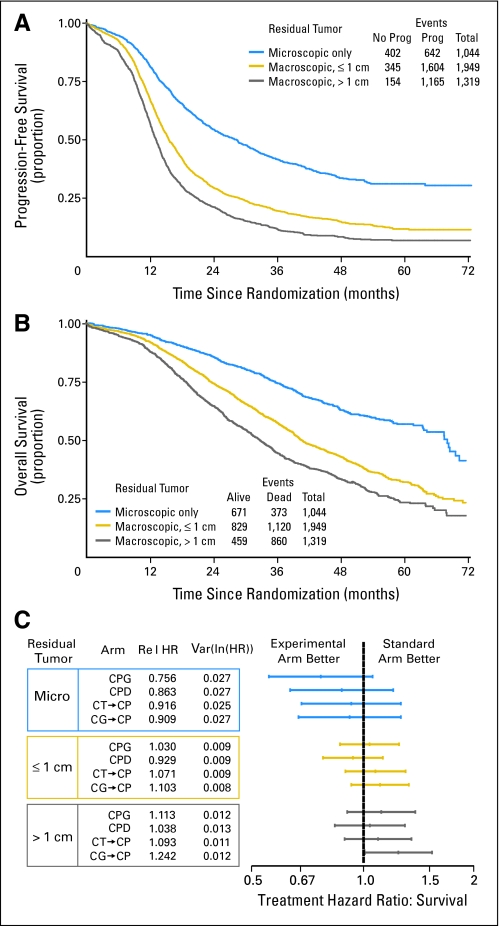

As anticipated, the extent of cytoreductive surgery remains an important prognostic factor for OS (Fig 4A), second only to stage at diagnosis. For patients with suboptimal (> 1 cm), gross-optimal (≤ 1 cm), and microscopic residual disease, the median PFS rates were 13, 16, and 29 months, respectively, and the median OS rates were 33, 40, and 68 months, respectively. It has been postulated that experimental therapy might have greater impact in patients who have small-volume residual disease, as they have more favorable prognoses. However, a planned analysis of HR for survival in relationship to the extent of residual disease also failed to show any positive benefit for experimental therapy in any subgroup (Fig 4B).

Fig 4.

(A) Estimate of overall survival and (B) progression-free survival according to the extent of residual disease, which remains a highly significant prognostic factor across all treatment regimens. (C) The potential benefit of experimental treatment regimens evaluated in subpopulations according to the extent of residual disease, illustrated by hazard ratios for survival. Prog, progression; CPG, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine; CPD, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin; CT-CP, carboplatin plus topotecan, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel; CG-CP, carboplatin plus gemcitabine, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel.

DISCUSSION

Maximal cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy remains the current global standard for management of advanced-stage EOC and PPC. Mature, phase III data14–16 and a meta-analysis17 established the superiority of cisplatin plus paclitaxel compared with cisplatin plus cyclophosphamide. Phase III trials also verified that carboplatin plus paclitaxel was at least as effective as cisplatin plus paclitaxel,18,19 which prompted the GCIG to publish consensus guidelines that favored carboplatin plus paclitaxel as the comparator arm for clinical trials.20 However, sequential therapy with platinum followed by paclitaxel at progression may achieve equivalent long-term outcomes for some patients.21,22

Although platinum-based agents remains dominant, taxanes have emerged as the second-most important class of agents in EOC, and carboplatin with paclitaxel was selected as the point of reference for this trial. Substitution of docetaxel for paclitaxel is an acceptable alternative that has a reduced risk of neuropathy and hypersensitivity, but it has an increased risk of dose-limiting hematologic toxicity, which would have complicated each experimental regimen.23

Even with these well-tolerated and effective standard therapies, most women who have advanced-stage EOC will eventually experience recurrence with chemotherapy-resistant disease, which will prompt a search for new agents to maximize the benefits of primary therapy. Several agents have emerged that have well-defined activity in the setting of recurrent disease, including topotecan, PLD, prolonged oral etoposide, and gemcitabine. Each of these agents has a unique molecular target, mechanism of action, and pattern of resistance, which lends credence to the development of multiagent combinations. In addition, each agent has the potential to accentuate the platinum response through increased formation of platinum-DNA adducts or through inhibition of DNA repair. In small, nonrandomized trials, response rates that approached 100% have been reported with combinations of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine.24,25 However, it remains to be determined from randomized trials if enhancement of platinum-mediated toxicity would be associated with improved survival.

The cooperative groups, which recognized that a large number of patients would be required for a definitive analysis of newer combinations, worked together through GCIG, which provided a framework for sharing preliminary clinical data and for the coordinated planning of international phase III trials.26,27 Although some trials ultimately had overlapping treatment regimens, the cumulative global experience provides a robust analysis of multiple platinum-based chemotherapy regimens for advanced-stage disease.

Preliminary development for GOG0182-ICON5, including phase I trials, was coordinated largely through GOG. Final protocol development was accomplished with collaboration from GCIG members. Accrual was facilitated by joint enrollment of patients who had optimal and suboptimal residual disease. International criteria were adopted to permit use of CA-125 to declare progression of disease after completion of primary therapy.5 Second-look laparotomy was not permitted, which helped to preserve PFS as a valid end point for IA.

The accrual rate reached 1,200 patients per year, which exceeded all prior combined accruals on GOG phase III trials in EOC. Strong participation within the gynecologic oncology community succeeded in enrolling approximately 6.25% of all women who had newly diagnosed advanced-stage disease in the United States during this period.

Results from GOG0182-ICON5 have matured in conjunction with other international efforts, including two trials to evaluate the addition of epirubicin and a smaller, randomized trial that incorporated topotecan (3 days) as a triplet with carboplatin and paclitaxel as well as a sequential doublet combination of cisplatin and topotecan followed by carboplatin and paclitaxel.28–31 Data are awaited from a triplet that incorporated gemcitabine (AGO-OVAR9), similar to GOG0182-ICON5.

Currently, there are not sufficient data to recommend any new two- or three-drug combination; thus, carboplatin with paclitaxel remains the standard regimen of choice. Although individual studies might be critiqued with regard to dose and/or schedule of individual drugs, each regimen was limited by practical management of toxicity in the setting of a cooperative group. More than 10,000 women are projected to have participated in these international studies, and it would be surprising if small differences in dose or schedule would have a major impact on long-term clinical outcomes.

There are several important points not directly addressed by these trials, including route of drug administration (including intraperitoneal options), molecular profiling of tumor and/or host to guide drug selection, and incorporation of molecular-targeted agents. In particular, the number and diversity of new agents identify important challenges to our conventional clinical paradigm. Compelling data have also emerged with single-agent bevacizumab in recurrent disease, which prompted the development of two international, front-line, phase III trials to address the addition of bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel.32

Large, multiarm, multistage, phase III trials are feasible with international collaboration and can promote the optimal use of limited clinical resources. However, innovative strategies are needed to efficiently select targeted agents and combinations that merit phase III evaluation, to improve outcomes beyond the current era of platinum-based therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the many women who participated in this trial and their families and physicians for support of these women, Suzanne Baskerville and Wendi Qian for expert assistance with centralized data coordination, and Mahesh K. Parmar for collaborative statistical design.

Appendix

The following institutions participated in this study:

GOG: Roswell Park Cancer Institute, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Duke University Medical Center, Abington Memorial Hospital, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, University of Minnesota Medical School, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Colorado Gynecologic Oncology Group PC, University of California at Los Angeles, University of Washington, University of Pennsylvania Cancer Center, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas, Indiana University School of Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, University of California Medical Center at Irvine, Tufts–New England Medical Center, Rush-Presbyterian–St. Luke's Medical Center, Magee Women's Hospital, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, University of Kentucky, University of New Mexico, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Southwestern Oncology Group, Washington University School of Medicine, Cooper Hospital/University Medical Center, Columbus Cancer Council, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Fox Chase Cancer Center, Women's Cancer Center, University of Oklahoma, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, University of Chicago, Tacoma General Hospital, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Mayo Clinic, Case Western Reserve University, Tampa Bay Cancer Consortium, Gynecologic Oncology Network, Ellis Fischel Cancer Center, Fletcher Allen Health Care, Yale University, University of Wisconsin Hospital, Cancer Trials Support Unit, University of Texas–Galveston, Women and Infants Hospital, Community Clinical Oncology Program, Australia New Zealand Gynaecological Oncology Group/NHMRC Clinical Trial Centre.

United Kingdom: Yeovil, Hull, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Airedale General Hospital, Bronglais General Hospital, Broomfield Hospital, Chelsea & Westminster Hospital, Cheltenham General Hospital, Christie Hospital, Churchill Hospital, City Hospital, Birmingham, Derbyshire Royal Infirmary, Derriford Hospital, Essex County Hospital, Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital, Huddersfield Royal Infirmary, Ipswich Hospital NHS Trust, James Cook University Hospital, Lincoln County Hospital, Maidstone Hospital, Manor Hospital Mount Vernon Hospital, New Cross Hospital, Newcastle General Hospital, North Devon District Hospital, Northampton General Hospital, Nottingham City Hospital Trust, Oldchurch Hospital, Pilgrim Hospital, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother's Hospital, Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Russell Hall Hospital, part of the Dudley Group of Hospitals, St Bartholomew's Hospital, St George's Hospital, St James's University Hospital, St Mary's Hospital–Portsmouth, Torbay Hospital UCLH Gynaecological Cancer Centre, Velindre Hospital NHS Trust, Weston Park Hospital, Wexham Park Hospital.

Italy: Bari, IEO, Monza San Gerardo Pavoda, Palermo Cervello Rimini, Thiene, Treviglio, Gallarate.

Table A1.

GOG0182-ICON5 Supplemental Data, Clinical Outcomes

| Outcome | Treatment Regimen |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP (n = 864) | CPG (n = 864) | CPD (n = 862) | CT→CP (n = 861) | CG→CP (n = 861) | |

| Progressions, total No.* | 686 | 687 | 663 | 687 | 688 |

| Proportion who experienced progression (CA-125)† | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| Deaths, total No. | 473 | 465 | 438 | 477 | 500 |

| Proportion PFS > 1 year | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.67 |

| Proportion PFS > 2 years | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.31 |

| Median PFS, months | 16.0 | 16.3 | 16.4 | 15.4 | 15.4 |

| Adjusted HR PFS‡ | 1.00 | 1.028 | 0.984 | 1.066 | 1.037 |

| 95% CI | 0.924 to 1.143 | 0.884 to 1.095 | 0.958 to 1.186 | 0.932 to 1.153 | |

| Proportion OS > 3 years§ | 0.57 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.55 |

| No. | 426 | 424 | 425 | 413 | 395 |

| Proportion OS > 5 years§ | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.34 | 0.30 |

| No. | 72 | 70 | 80 | 73 | 66 |

| Median OS, months | 44.1 | 44.1 | 44.2 | 40.2 | 39.6 |

| Adjusted HR OS‡ | 1.00 | 1.006 | 0.952 | 1.051 | 1.114 |

| 95% CI | 0.885 to 1.144 | 0.836 to 1.085 | 0.925 to 1.194 | 0.982 to 1.264 | |

Abbreviations: GOG, Gynecologic Oncology Group; ICON, International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm; CP, carboplatin and paclitaxel; CPG, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine; CPD, carboplatin, paclitaxel, and doxorubicin; CT→CP, carboplatin plus topotecan, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel; CG→CP, carboplatin plus gemcitabine, then carboplatin plus paclitaxel; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio.

Total number of progressions (increasing disease, new disease) or deaths.

Proportion of total progression events based on CA-125 criteria.

Treatment hazard ratios adjusted for residual disease size and coordinating center.

Kaplan-Meier estimated survival with number of patients at-risk, 3 years and 5 years.

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute Grants No. CA 27469 to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office and CA 37517 to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data Center. ICON5 was funded by the MRC and has been supported by the NCRN through Grant No. ISRCTN 41636183.

Presented in part at the 42nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, June 2-6, 2006, Atlanta, GA.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: Michael A. Bookman, Genentech Oncology (C); Ann Marie Swart, Schering-Plough (C) Consultant or Advisory Role: Michael A. Bookman, Bristol-Myers Squibb (C), GlaxoSmithKline (C), Johnson & Johnson (C), Sanofi-aventis (C), Novartis (C), Genentech Oncology (C); William P. McGuire, GlaxoSmithKline (C), Sunesis (C), Unither (C); Peter G. Harper, Roche (C), Novartis (C), Pfizer Inc (C); David G. Mutch, Eli Lilly & Co (C), GlaxoSmithKline (C) Stock Ownership: Ann Marie Swart, Schering-Plough Honoraria: Michael A. Bookman, Eli Lilly & Co; William P. McGuire, GlaxoSmithKline, Imclone, Sunesis; Peter G. Harper, Novartis; Michael Friedlander, Eli Lilly & Co, Schering-Plough; David G. Mutch, GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly & Co, Merck & Co; Robert A. Burger, Genentech Research Funding: William P. McGuire, GlaxoSmithKline; David G. Mutch, Eli Lilly & Co Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Michael A. Bookman, Mark F. Brady, William P. McGuire, Peter G. Harper, David S. Alberts, Edward L. Trimble

Financial support: Edward L. Trimble

Administrative support: Ann Marie Swart, Edward L. Trimble

Provision of study materials or patients: Michael A. Bookman, William P. McGuire, Michael Friedlander, Jeffrey M. Fowler, Peter A. Argenta, Koen De Geest, David G. Mutch, Robert A. Burger, Ann Marie Swart, Edward L. Trimble, Lawrence M. Roth

Collection and assembly of data: Michael A. Bookman, Mark F. Brady, William P. McGuire, David G. Mutch, Robert A. Burger, Ann Marie Swart, Chrisann Accario-Winslow, Lawrence M. Roth

Data analysis and interpretation: Michael A. Bookman, Mark F. Brady, William P. McGuire, Ann Marie Swart, Lawrence M. Roth

Manuscript writing: Michael A. Bookman, Mark F. Brady, William P. McGuire, Peter G. Harper, David S. Alberts, Michael Friedlander, Nicoletta Colombo, Peter A. Argenta, David G. Mutch, Robert A. Burger, Ann Marie Swart, Edward L. Trimble

Final approval of manuscript: Michael A. Bookman, Mark F. Brady, William P. McGuire, Peter G. Harper, David S. Alberts, Michael Friedlander, Nicoletta Colombo, Jeffrey M. Fowler, Koen De Geest, David G. Mutch, Robert A. Burger, Ann Marie Swart, Edward L. Trimble, Lawrence M. Roth

REFERENCES

- 1.ten Bokkel Huinink W, Lane SR, Ross GA, et al. Long-term survival in a phase III, randomised study of topotecan versus paclitaxel in advanced epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:100–103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon AN, Tonda M, Sun S, et al. Long-term survival advantage for women treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with topotecan in a phase 3 randomized study of recurrent and refractory epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;95:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfisterer J, Plante M, Vergote I, et al. Gemcitabine plus carboplatin compared with carboplatin in patients with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: An intergroup trial of the AGO-OVAR, the NCIC CTG, and the EORTC GCG. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4699–4707. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer BE, Bundy BN, Ozols RF, et al. Implications of second-look laparotomy in the context of optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: A non-randomized comparison using an explanatory analysis: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rustin GJ, Timmers P, Nelstrop A, et al. Comparison of CA-125 and standard definitions of progression of ovarian cancer in the intergroup trial of cisplatin and paclitaxel versus cisplatin and cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:45–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Look KY, Bookman MA, Schol J, et al. Phase I feasibility trial of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and gemcitabine in patients with previously untreated epithelial ovarian or primary peritoneal cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:93–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iaffaioli RV, Tortoriello A, Facchini G, et al. Phase I/II study of gemcitabine and carboplatin in stages IIIB to IV non–small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:921–926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bookman MA, McMeekin DS, Fracasso PM. Sequence dependence of hematologic toxicity using carboplatin and topotecan for primary therapy of advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: A phase I study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:473–478. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong DK, Bookman MA, McGuire W, et al. A phase I study of paclitaxel, topotecan, cisplatin and Filgrastim in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian epithelial malignancies: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:667–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose PG, Greer BE, Horowitz IR, et al. Paclitaxel, carboplatin and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in ovarian and peritoneal carcinoma: A phase I study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royston P, Parmar MKB, Qian W. Novel designs for multi-arm clinical trials with survival outcomes with an application in ovarian cancer. Stat Med. 2003;22:2239–2256. doi: 10.1002/sim.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peto R, Peto J. Asymptotically efficient rank invariant procedures. J Roy Stat Soc A. 1972;135:185–206. discussion 199-206. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenfeld D. The asymptotic properties of the nonparametric tests for comparing survival distributions. Biometika. 1981;68:316–319. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire WP, Hoskins WJ, Brady MF, et al. Cyclophosphamide and cisplatin compared with paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with stage III and stage IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601043340101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, James K, et al. Randomized intergroup trial of cisplatin-paclitaxel versus cisplatin-cyclophosphamide in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: Three-year results. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:699–708. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.9.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccart MJ, Bertelsen K, Stuart G, et al. Long-term follow-up confirms a survival advantage of the paclitaxel-cisplatin regimen over the cyclophosphamide-cisplatin combination in advanced ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13(suppl 2):144–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2003.13357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kyrgiou M, Salanti G, Pavlidis N, et al. Survival benefits with diverse chemotherapy regimens for ovarian cancer: Meta-analysis of multiple treatments. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1655–1663. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–3200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.du Bois A, Luck HJ, Meier W, et al. Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynakologische Onkologie Ovarian Cancer Study Group: A randomized clinical trial of cisplatin/paclitaxel versus carboplatin/paclitaxel as first-line treatment of ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95:1320–1329. [Google Scholar]

- 20.du Bois A, Quinn M, Thigpen T, et al. Final document of the 3rd International Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Ovarian Cancer Consensus Conference (GCIG OCCC 2004). Ann Oncol. 2005;16(suppl 8):viii7–viii12. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muggia FM, Braly PS, Brady MF, et al. Phase III randomized study of cisplatin versus paclitaxel versus cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with suboptimal stage III or IV ovarian cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:106–115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm (ICON) Group. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard chemotherapy with either single-agent carboplatin or cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in women with ovarian cancer: The ICON3 randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:505–515. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vasey PA, Jayson GC, Gordon A, et al. Phase III randomized trial of docetaxel-carboplatin versus paclitaxel-carboplatin as first-line chemotherapy for ovarian carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1682–1691. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.du Bois A, Belau A, Wagner U, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel, carboplatin, and gemcitabine in previously untreated patients with epithelial ovarian cancer FIGO stage IC-IV (AGO-OVAR protocol OVAR-8). Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96:444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hansen SW. Gemcitabine, platinum, and paclitaxel regimens in patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma. Semin Oncol. 2002;29(suppl 1):17–19. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.31593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trimble EL, Davis J, DiSaia P, et al. Clinical trials in gynecological cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:547–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vermorken JB, Avall-Lundqvist E, Pfisterer J, Bacon M. The Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG): history and current status. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(suppl 8):viii39–viii42. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.du Bois A, Weber B, Rochon J, et al. Addition of epirubicin as a third drug to carboplatin-paclitaxel in first-line treatment of advanced ovarian cancer: A prospectively randomized gynecologic cancer intergroup trial by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Ovarian Cancer Study Group and the Groupe d'Investigateurs Nationaux pour l'Etude des Cancers Ovariens. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1127–1135. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kristensen GB, Vergote I, Stuart G, et al. First-line treatment of ovarian cancer FIGO stages IIb-IV with paclitaxel/epirubicin/carboplatin versus paclitaxel/carboplatin. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13(suppl 2):172–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2003.13363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scarfone G, Scambia G, Raspagliesi F, et al. A multicenter, randomized, phase III study comparing paclitaxel/carboplatin (PC) versus topotecan/paclitaxel/carboplatin (TPC) in patients with stage III (residual tumor > 1 cm after primary surgery) and IV ovarian cancer (OC). J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(suppl 18S):5003. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoskins PJ, Vergote I, Stuart G, et al. A phase III trial of cisplatin plus topotecan followed by paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus standard carboplatin plus paclitaxel as first-line chemotherapy in women with newly diagnosed advanced epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) (OV. 16): A Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup Study of the NCIC CTG, EORTC GCG, and GEICO. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(suppl):294s. abstr LBA5505. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burger RA, Sill M, Monk BJ, et al. Phase II trial of bevacizumab in persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer or primary peritoneal cancer: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5165–5171. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.