Abstract

Purpose

To develop an evidence-based guideline on the use of 5-α-reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs) for prostate cancer chemoprevention.

Methods

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Health Services Committee (HSC), ASCO Cancer Prevention Committee, and the American Urological Association Practice Guidelines Committee jointly convened a Panel of experts, who used the results from a systematic review of the literature to develop evidence-based recommendations on the use of 5-ARIs for prostate cancer chemoprevention.

Results

The systematic review completed for this guideline identified 15 randomized clinical trials that met the inclusion criteria, nine of which reported prostate cancer period prevalence.

Conclusion

Asymptomatic men with a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) ≤ 3.0 ng/mL who are regularly screened with PSA or are anticipating undergoing annual PSA screening for early detection of prostate cancer may benefit from a discussion of both the benefits of 5-ARIs for 7 years for the prevention of prostate cancer and the potential risks (including the possibility of high-grade prostate cancer). Men who are taking 5-ARIs for benign conditions such as lower urinary tract [obstructive] symptoms (LUTS) may benefit from a similar discussion, understanding that the improvement of LUTS relief should be weighed with the potential risks of high-grade prostate cancer from 5-ARIs (although the majority of the Panel members judged the latter risk to be unlikely). A reduction of approximately 50% in PSA by 12 months is expected in men taking a 5-ARI; however, because these changes in PSA may vary across men, and within individual men over time, the Panel cannot recommend a specific cut point to trigger a biopsy for men taking a 5-ARI. No specific cut point or change in PSA has been prospectively validated in men taking a 5-ARI.

INTRODUCTION

Surveys1,2 of American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) members have shown strong interest in cancer prevention interventions applicable to clinical practice, and most respondents envision increased utilization of prevention in their practices. Chemoprevention, a strong area of research, is particularly relevant to practicing oncologists and urologists because its application is well suited to the clinical setting in which shared decision making takes place between health professionals and individual patients. To date, the strongest evidence of efficacy in the field of chemoprevention has come from the hormonally responsive tumors: breast cancer with tamoxifen and raloxifene3,4 and prostate cancer with the 5-α-reductase inhibitor (5-ARI) finasteride.5 Unlike most other chemopreventive agents under study, such as cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors and retinoids, tamoxifen and finasteride have been shown definitively in randomized clinical trials to decrease the incidence of invasive cancers—not just surrogate end points—in healthy people.3–6 Nevertheless, these agents have adverse effects that require careful discussion with patients considering whether or not to take the agent.

Although substantial data are available on the use of 5-ARIs in other settings—primarily, treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)7–10—the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) is the only completed randomized trial prospectively designed to show a reduction in period-prevalence of prostate cancer.5 The PCPT investigators reported a decrease in cumulative incidence of prostate cancer from 24.4% in the placebo arm to 18.4% in the finasteride arm during the 7 years of the trial. Nevertheless, an observed increase of Gleason scores 7 to 10 in the finasteride study arm (37%, or 280 of 757 tumors) compared with the placebo arm (22.2%, or 237 of 1,068 tumors), noted in a secondary analysis, triggered concern about harm.

These issues complicate informed decision making by patients who are considering finasteride for prostate cancer chemoprevention, and are important to the many men taking finasteride for the management of BPH or for male pattern baldness. Published proposals discuss the balance of risks and benefits of finasteride for the prevention of prostate cancer,11 although some have questioned the assumptions used in the calculation as overly favorable.12 Because of the importance of the issue to both clinical oncologists and urologists, ASCO has collaborated with the American Urological Association (AUA) to develop a clinical practice guideline on the benefits and harms of 5-ARIs for the prevention of prostate cancer. New information will likely become available from ongoing analyses in the PCPT and the results of the REDUCE (Reduction by Dutasteride of Prostate Cancer Events) trial,13 a prevention trial testing dutasteride, which inhibits both isoforms (types 1 and 2) of 5-α-reductase. This guideline, sponsored by ASCO and AUA, aims to provide a useful tool for clinicians and their patients in making an informed decision about the potential harms and benefits of taking 5-ARIs for preventing prostate cancer. As part of its deliberations, the Panel also evaluated the outcomes of the PLESS (Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study) and MTOPS (Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms) trials, which examined 5-ARIs for the relief of urinary tract obstruction, because reduced incidence of urinary tract obstruction is one of the potential benefits of 5-ARI use. The charge to the Panel was to judge the balance of benefits and harms.

GUIDELINE QUESTIONS

This guideline addresses the use of 5-ARIs in preventing prostate cancer. The overarching question was should men routinely be offered a 5-ARI for the chemoprevention of prostate cancer? To address this question, the committee identified important components likely to influence assessments of the balance of risks and benefits and decision making that required evaluation:

What is the impact of 5-ARIs on the risk of incident prostate cancer, prostate cancer mortality, and overall mortality? Do benefits and harms of 5-ARIs vary among identifiable subpopulations (eg, age, race/ethnicity, family history, baseline risk for prostate cancer) and by type of 5-ARI?

Do 5-ARIs have a differential effect on the development of different histologic grades or stages of prostate cancer? Are any such differences likely to modify the curability of prostate cancer when diagnosed? Is the Gleason histologic grading system for prostate cancer applicable to men who are receiving 5-ARIs or other interventions that target the androgen pathway?

What is the impact of 5-ARIs on the need for treatment of benign prostatic disease?

What is the impact of 5-ARIs on quality of life? What are other potential harms and adverse effects of 5-ARIs? What are other potential benefits of, and indications for, 5-ARI use (eg, benign prostatic hyperplasia, male baldness)?

How long should treatment continue for the best outcome (period v lifelong)?

What are the future directions of research regarding 5-ARIs for the prevention of prostate cancer?

PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Practice guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist practitioners and patients in making decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances. Attributes of good guidelines include validity, reliability, reproducibility, clinical applicability, clinical flexibility, clarity, multidisciplinary process, review of evidence, and documentation. Guidelines may be useful in producing better care and decreasing cost. Specifically, utilization of clinical guidelines may provide the following:

Improvement in outcomes

Improvement in medical practice

Means for minimizing inappropriate practice variation

Decision support tools for practitioners

Points of reference for medical orientation and education

Criteria for self-evaluation

Indicators and criteria for external quality review

Assistance with reimbursement and coverage decisions

Criteria for use in credentialing decisions

Identification of areas where further research is needed.

In formulating recommendations for the use of 5-ARIs for prostate cancer prevention, ASCO and AUA have considered these tenets of guideline development, emphasizing review of data from appropriately conducted and analyzed clinical trials. These same tenets can be utilized and applied to formulation of prevention guidelines. However, it is important to note that guidelines cannot always account for individual variation among patients. Guidelines are not intended to supplant physician judgment with respect to particular patients or special clinical situations and cannot be considered inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other treatments reasonably directed at obtaining the same result.

ASCO and AUA's practice guidelines and technology assessments reflect expert consensus based on clinical evidence and literature available at the time they are written, and are intended to assist physicians in clinical decision making and identify questions and settings for further research. Due to the rapid flow of scientific information in oncology, new evidence may have emerged since the time a guideline or assessment was submitted for publication. Guidelines and assessments are not continually updated and may not reflect the most recent evidence. Guidelines and assessments cannot account for individual variation among patients, and cannot be considered inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other treatments. It is the responsibility of the treating physician or other health care provider, relying on independent experience and knowledge of the patient, to determine the best course of treatment for the patient. Accordingly, adherence to any guideline or assessment is voluntary, with the ultimate determination regarding its application to be made by the physician in light of each patient's individual circumstances. ASCO and AUA guidelines and assessments describe the use of procedures and therapies in clinical practice and cannot be assumed to apply to the use of these interventions in the context of clinical trials. ASCO and AUA assume no responsibility for any injury or damage to persons or property arising out of or related to any use of ASCO and AUA's guidelines or assessments, or for any errors or omissions.

METHODS

Panel Composition

The ASCO Health Services Committee (HSC) and the AUA Practice Guidelines Committee jointly convened an Expert Panel (hereafter referred to as the Panel) consisting of experts in clinical medicine and research methods relevant to chemoprevention for prostate cancer. The experts' fields included medical oncology, urology, pathology, epidemiology, statistics, and health services research. The Panel included academic and community practitioners as well as a patient representative. The Panel members are listed in Appendix Table A1.

Literature Review and Analysis

Wilt et al systematic review.

The AUA commissioned a systematic review of the literature on the role of 5-ARIs in the chemoprevention of prostate cancer. That review, which is published in the Cochrane Library,14 served as the primary source of evidence for this guideline. Articles were selected for inclusion in the systematic review if they met the following prospective criteria: (1) a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that examined a 5-ARI versus a control; (2) treatment period that was at least 1 year; (3) study population that consisted of men age 45 years or older; (4) period prevalence of prostate cancer was one of the reported outcomes; and (5) the study was published after 1984. For nonprostate cancer outcomes, randomized trials were selected for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) treatment period was at least 6 months; (2) an RCT compared a 5-ARI to a nonactive control or to another active treatment; (3) study population consisted of men age 45 years or older; (4) at least one of the secondary outcomes of interest chosen by the Panel were reported; and (5) the study was published after 1999. This date was chosen because the AUA guideline on the management of BPH included studies published through 1999.7 PCPT authors provided unpublished information at the request of the panel. Additional details of the literature search strategy and meta-analyses are provided elsewhere.14

ASCO/AUA Expert Panel literature review and analysis.

The Panel reviewed all data from the primary studies contained in the systematic review; subsequently, the Panel considered the results of the meta-analyses contained in the systematic review.

Consensus Development Based on Evidence

A steering committee met in October 2005. The steering committee was charged with identifying potential Panel members and with drafting the clinical questions the Panel was to address. In August 2006 the entire Panel met; the Panel completed its additional work through teleconferences. The purposes of the Panel meeting were to refine the questions addressed by the guideline and to make writing assignments for the respective sections. All members of the Panel participated in the preparation of the draft guideline, which was then disseminated for review by the entire Panel. Feedback from external reviewers was also solicited. The ASCO HSC and the AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, as well as the Board of Directors of both organizations, reviewed and approved the content of the guideline and the manuscript before dissemination.

Guideline and Conflicts of Interest

All members of the Expert Panel complied with the ASCO and AUA policies on conflicts of interest, which require disclosure of any financial or other interest that might be construed as constituting an actual, potential, or apparent conflict. Members of the Expert Panel completed disclosure forms and were asked to identify ties to companies developing products that promulgation of the guideline might affect. Information was requested regarding employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria, research funding, expert testimony, and membership on company advisory committees. The Panel made decisions on a case-by-case basis as to whether an individual's role should be limited as a result of a conflict. No limiting conflict was identified.

Revision Dates

At biannual intervals, the Panel Co-Chairs and two Panel members designated by the Co-Chairs will examine current literature to determine if there is a need for revisions to the guideline. If necessary, the entire Panel will reconvene to discuss potential changes. When appropriate, the Panel will recommend revision of the guideline to the ASCO HSC, the ASCO Board, the AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, and the AUA Board for review and approval.

Definition of Terms

Period prevalence: the proportion of the randomized population identified as having prostate cancer over the trial period.

5-α-reductase: an enzyme that converts testosterone into the more potent dihydrotestosterone (DHT). 5-α-Reductase has two isoenzymes (isoforms): types 1 and 2. Finasteride inhibits the type 2 isoenzyme, whereas dutasteride inhibits both the type 1 and type 2 isoenzymes.

Primary prevention: Intervention for relatively healthy individuals with no invasive cancer and an average risk for developing cancer.15

Chemoprevention: the use of chemical compounds to reduce the risk of development of a specific disease (as used here, specifically for the reduction in risk of developing prostate cancer).

LUTS: Lower urinary tract [obstructive] symptoms.

AUA Symptom Index/International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS): a symptom index for BPH, developed by the AUA. The IPSS consists of seven questions, with scores ranging from 0 to 35. A score between 0 and 7 is considered to represent mild symptoms; 8 to 19, moderate; and 20 to 35, severe. A change in score by 2 to 3 points is generally accepted as clinically meaningful (ie, morbid and/or life threatening).

Summary of Outcomes Assessed

The primary outcome assessed was either prostate cancer incidence or period prevalence, in prostate cancers detected “for cause.” For-cause cancers were defined as those that (1) were suspected clinically during the course of the trial because of symptoms, abnormal digital rectal exam, or abnormal PSA (ie, a PSA that exceeded a certain value or rate of increase over time) and were confirmed on biopsy; or (2) during the trial, a recommendation was made for biopsy according to the study protocol (eg, due to increasing PSA) which was never done, and end-of-study biopsy showed prostate cancer; or (3) end-of-study biopsy in the setting of a PSA more than 4 or a suspicious digital rectal examination (DRE) showed prostate cancer.

Other primary outcomes assessed were distribution of stage of prostate cancer, Gleason scores, and incidence or period prevalence of prostate cancer by age, race, baseline PSA, and family history.

Secondary outcomes included prostate cancer detected purely for reasons dictated by study protocol, rather than by clinical indication (eg, an end-of-study biopsy was required per protocol despite a PSA ≤ 4 ng/mL, and DRE not suggestive of cancer), and overall incidence or period prevalence of prostate cancer (ie, cancers detected for cause plus cancers detected by study protocol). Other secondary outcomes included quality of life; change in validated urinary symptom scale scores (IPSS/AUA); BPH progression (development of acute urinary retention, interventions for treatment of LUTS, medications and herbal therapies to treat LUTS, surgical interventions); overall mortality; prostate cancer–specific mortality; adverse events (impotence, retrograde ejaculation, decreased ejaculate volume, decreased libido, gynecomastia); and cost effectiveness. Neither formal cost effectiveness nor decision analysis was planned for the guideline, although the Panel considered available reports.

RESULTS

Literature Search

Wilt et al14 identified 15 RCTs that met the inclusion criteria; nine of these trials reported prostate cancer period-prevalence.

Previous Guidelines and Consensus Statements

Updated in 2003,7 the 1999 AUA guideline on the management of benign prostate hyperplasia can be summarized as follows:

Finasteride, a 5-ARI, demonstrates both efficacy and acceptable safety for treatment of LUTS due to BPH. Finasteride can reduce the size of the prostate, can increase peak urinary flow rate, and can reduce BPH symptoms. With finasteride, the average patient experiences a 3-point improvement in the AUA Symptom Index. In general, patients perceive this level of symptom improvement as a meaningful change. Finasteride is ineffective for relief of lower urinary tract obstructive symptoms in patients who do not have enlarged prostates. Reported adverse events are primarily sexually related; they include decreased libido, ejaculatory dysfunction, and erectile dysfunction, which are reversible and therefore uncommon after the first year of therapy. Symptom score improvement is not substantially greater among men with very large versus only moderately enlarged prostates; however, because of the more progressive nature of the disease in men with larger glands or higher PSA values, such patients conservatively treated (watchful or placebo groups) face an increasingly higher risk of complication, thereby enhancing the difference over time in outcomes between finasteride and no treatment or placebo groups.

In summary, finasteride reduces the risk of subsequent acute urinary retention and the need for BPH-related surgery with the absolute benefit increasing with rising prostate volume or serum PSA. Finasteride is not appropriate treatment for men with LUTS who do not have any prostatic enlargement.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Should Men Routinely Be Offered a 5-ARI for the Chemoprevention of Prostate Cancer?

Asymptomatic men with a PSA ≤ 3.0 who are regularly screened with PSA or are anticipating undergoing annual PSA screening for early detection of prostate cancer may benefit from a discussion of the benefits of 5-ARIs for 7 years for the prevention of prostate cancer and the potential risks (including the possibility of high-grade prostate cancer) to be able to make a better-informed decision. Men who are taking 5-ARIs for benign conditions such as LUTS would benefit from a similar discussion.

Of note, one Panel member believed that the explanation of decreased prostate cancer period prevalence in the finasteride arm of the PCPT is attributable to differential biopsy rates between the two trial arms. The 25% risk reduction is based primarily on the PCPT and the risk reduction of a prostate diagnosis accrued primarily as a result of the lower rates of biopsy among men on finasteride. For those men who underwent a biopsy, the risk reduction was a statistically nonsignificant 10%. By contrast, the principal investigator of the PCPT has published a commentary stating that differential biopsy rate is not likely to account for a substantial proportion of the observed difference. He argues that critics of the PCPT “…ignore the effects of PSA, DRE, and biopsy detecting the cancer in the finasteride group, which would be expected to further reduce the risk of cancer overall.”

Evidence Summary

The summary of evidence of the effect of 5-ARIs on prostate cancer period prevalence is based on nine RCTs in which administration of the 5-ARI ranged from 1 to 7 years.14 Two additional trials lasting at least 6 months provided data on BPH-related outcomes and adverse effects. Most of the trials were placebo controlled and double-blinded (Appendix Table A2). The results of all trials were generally consistent. The most salient end point chosen by the Panel was the comparison in trials of at least 1 year duration of period prevalence of for-cause prostate cancers between study arms, as defined in the Methods section and glossary, using an intent-to-treat analysis (five studies). This end point comes closest to addressing prevention of those cancers that are considered most important in clinical decision making—those diagnosed because of symptoms, DRE that is clinically suggestive, or a PSA that triggers a biopsy. Only one of the randomized trials, the placebo-controlled PCPT, was specifically designed to assess the period prevalence of prostate cancer in generally healthy men without underlying moderate or severe lower urinary track symptoms. The PCPT was the largest trial in the literature, with 18,882 of the total 33,403 participants in trials receiving at least 1 year of active therapy. The PCPT also contributed approximately 85% (1,006 of 1,188) of the for-cause cancers in the systematic review.14 Men in all of the trials were screened regularly for prostate cancer with PSA and DRE. Therefore, the literature reviewed does not allow assessment of the impact of 5-ARIs on the period prevalence of prostate cancer among men who are not being actively screened for prostate cancer.

Review of Relevant Literature

What is the impact of 5-ARIs on the risk of incident prostate cancer, prostate cancer mortality, and overall mortality? Do benefits and harms of 5-ARIs vary among identifiable subpopulations (eg, age, race/ethnicity, family history, baseline risk for prostate cancer) and by type of 5-ARI?

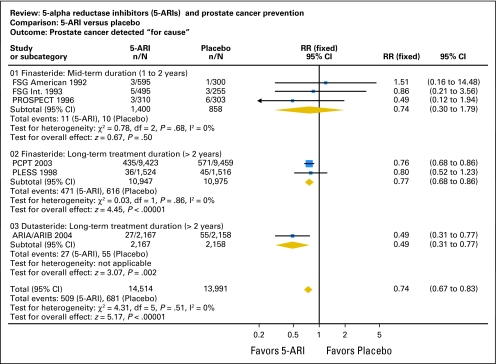

5-ARIs decrease the period prevalence of for-cause prostate cancer by approximately 26% (relative risk = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.83; Fig 1). The absolute risk reduction is about 1.4% (4.9% in controls v 3.5% in 5-ARI arms), although this may vary with the age of the treated population. (For comparison, the data from the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial3 suggest that about 100 women with a 2% baseline risk of breast cancer would have to be treated for approximately 6 years with tamoxifen to prevent one case of invasive breast cancer.) The relative risk of any prostate cancer with 5-ARI treatment versus controls was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.56 to 0.98), for an absolute risk reduction of 2.9% (9.2% v 6.3%; Fig 2).

Fig 1.

Prostate cancer detected for cause.5-ARI, 5-α-reductase inhibitor; RR, relative risk; FSG, Finasteride Study Group; PROSPECT, Proscar Safety Plus Efficacy Canadian Two-Year study; PCPT, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; PLESS, Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study. Adapted with permission from the Cochrane Collaboration.

Fig 2.

Prostate cancer detected overall. 5-ARI, 5-α-reductase inhibitor; RR, relative risk; FSG, Finasteride Study Group; PROSPECT, Proscar Safety Plus Efficacy Canadian Two-Year study; PCPT, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; PLESS, Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study. Adapted with permission from the Cochrane Collaboration.

The PCPT is the most relevant of the trials considered because its target population was men with at most mild lower urinary track symptoms who had a normal DRE and PSA less than 3 ng/mL at study entry. This population is probably closest to a true primary prevention population. In the PCPT, the relative risk of for-cause prostate cancers among those receiving finasteride versus placebo was 0.76 (95% CI, 0.68 to 0.86). This reduction corresponds to the need to treat approximately 71 healthy men for approximately 7 years to prevent one case of prostate cancer (95% CI, 50 to 100).

Only the PCPT reported subgroup results by race/ethnicity, age, and family history of prostate cancer. The data showed no apparent difference in efficacy of finasteride within any of these subgroups (Appendix Table A3), but estimates are necessarily imprecise, especially with regard to race/ethnicity, because approximately 92% of the participants in the PCPT were non-Hispanic whites.

Importantly, the participants in all the trials were being actively screened for prostate cancer. This study design issue affects the interpretation of the potential effect of 5-ARIs on the risk of developing prostate cancer. For example, regular screening with PSA is known to double the incidence of diagnosed prostate cancer.16 The relative reduction in risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer of approximately 26% must be interpreted in this context, yielding a net increase in prostate cancer diagnoses of approximately 48% for the combined strategy of screening plus chemoprevention. The studies provide no information as to whether the magnitude of risk reduction for the diagnosis of prostate cancer achieved by 5-ARIs would be the same, or considerably less, in men who are not being actively screened for prostate cancer.

None of the trials was large enough to detect clinically important differences in either prostate cancer–specific mortality or overall mortality, and no difference was noted. The summary relative risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality from the randomized trials was 1.00, with wide 95% CIs (0.29 to 3.47). Likewise, the relative risk for all-cause mortality for 5-ARIs versus controls was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.95 to 1.18). Absolute rates of prostate cancer mortality and overall mortality were 0.5% and 5.0%, respectively. Nevertheless, the Panel judged that even if 5-ARI treatment never translates into reduced overall or prostate cancer–specific mortality, reduction in risk of prostate cancer diagnosis with the consequent morbidity of treatment is a clinically beneficial end point in and of itself.

Do 5-ARIs have a differential effect on the development of different histologic grades or stages of prostate cancer? Are any such differences likely to modify the curability of prostate cancer when diagnosed? Is the Gleason histologic grading system for prostate cancer applicable to men who are receiving 5-ARIs or other interventions that target the androgen pathway?

The original publication and analysis of the PCPT screening trial5 reported a statistically significant reduction in the 7-year period prevalence of prostate cancer when finasteride was compared with placebo. A secondary analysis showed an unexpected statistically significant greater number of high Gleason grade cancers in the finasteride treatment arm. For every thousand men, finasteride reduced the number of prostate cancers from 60 to 45; however, if the observations represent a true finding, the number of high-grade cancers would increase from 18 to 21 in this cohort.14 The concern of paramount importance was the potential causal relationship of finasteride to high-grade cancer. The PCPT investigators, practicing physicians, and the Panel all struggled with the question of whether the increase in high-grade cancers reflected a real risk of finasteride or merely confounding factors.

Several subsequent analyses of the data from the trial have addressed this question. An initial concern centered about the morphologic and histopathologic alterations that might be attributed to a hormonal agent or an agent, such as finasteride, which alters the hormonal milieu. Might morphologic changes caused by finasteride mimic high-grade cancer, and therefore artifactually produce a higher Gleason reading? A detailed pathologic review eliminated the questions of morphologic artifact as a reason for the higher number of Gleason grade tumors in the finasteride arm.17

A second question that was addressed by the PCPT investigators was the degree of sampling error induced by the established effect of 5-ARIs on reduction in prostate volume. Finasteride reduces prostate volume by approximately 25% to 30%.5,9,10,18 The smaller the prostate volume, the less likely the sampling error using the PCPT's protocol-prescribed systematic sextant needle biopsies. Biopsies of the smaller prostates increase the likelihood of detection of prostate cancer of all grades. If finasteride is more effective in preventing low-grade tumors than high-grade tumors, it is possible to observe a reduction in overall period prevalence of cancers, a reduction in low- and moderate-grade cancers, but an absolute increase in high-grade cancers as a consequence of less sampling error in the finasteride arm. Indeed, modeling incorporating prostate volume suggests that the increase in high-grade cancers seen in the PCPT may be nearly completely explained by enhanced detection and not tumor transformation or induction, and would not be expected to translate into an increase in prostate cancer mortality.18

A series of multivariable logistic regression models was used to predict the incidence of high-grade cancer in the finasteride and placebo arms.19 A model that did not incorporate grading information from radical prostatectomies showed a nonsignificant 14% increase in high-grade cancer (P =.12) in the finasteride group; however, incorporating information on grading led to a 27% lower (P = .02) bias-adjusted estimated rate of high-grade cancer in the finasteride arm (6.0%) than in the placebo arm (8.2%). Although subject to the uncertainty of modeling assumptions outcomes, this analysis lends additional support against high-grade disease induction by finasteride.

A third question of potential bias revolves around the possibility of differences between the finasteride and placebo study arms of the PCPT in the operating characteristics of PSA and DRE. Analysis by receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrate heightened sensitivity of both PSA and DRE in the finasteride arm relative to the placebo arm, suggesting an enhanced suspicion for (and detection of) prostate cancer in the finasteride arm.20 It is reassuring that despite the greater proportion of patients with biopsy Gleason scores of ≥ 7 in the finasteride group relative to placebo, patients from the two groups who subsequently were treated with radical prostatectomy showed no difference in pathologic stage, nodal involvement, or margin status. This observation, however, was possibly driven by differential choices in the decision to undergo radical prostatectomy.

In summary, the Panel judged that plausible reasons could have led to a spurious increase in high-grade cancers. The Panel believed that it was unlikely for an agent to increase the incidence of high-grade tumors and simultaneously decrease the incidence of low-grade tumors. Furthermore, at this time there is no known pathologic adjustment factor for men diagnosed with prostate cancer while taking a 5-ARI versus men not taking a 5-ARI. Nor is there information on the long-term outcomes for a given histologic grade for men taking a 5-ARI versus men not having received a 5-ARI. Therefore, until this information is known, decisions regarding the natural history of the disease and decisions regarding treatment interventions should be based on the histologic information obtained on biopsy, regardless of 5-ARI status. Such an effect would be difficult to explain on the basis of known biologic mechanisms. Nevertheless, none of the observations provides proof that finasteride would not increase the true incidence of high-grade cancers. Therefore, men should be fully apprised of the remaining uncertainty surrounding high-grade cancers with finasteride.

Lastly, a detailed analysis of core biopsy specimens compared standard prognostic findings for cancers detected in the finasteride and placebo arms and made the following observations. For cancers assigned Gleason score ≤ 6, the mean number of cores positive was 1.4 in the finasteride arm and 1.55 in the placebo arm (P = .024); the mean percentage of cores positive for Gleason score 7 was 31.2 and 36.7 (P = .009); and for cancers assigned Gleason score ≥ 8, bilateral core positivity was 28.6% in the finasteride arm and 44.6% in the placebo arm (P = .047). These data suggest that men taking finasteride had smaller, less aggressive tumors versus men taking placebo.21

Apart from chemoprevention for prostate cancer, many men take a 5-ARI for indications such as lower urinary tract obstructive symptoms or male pattern baldness. The observed increase in high-grade prostate cancers in men receiving finasteride in the PCPT, and the theoretical possibility of increased risk of prostate cancer mortality, should be discussed with these men. The considerations mentioned above provide some reassurance that the increase in diagnosis of high-grade tumors is more likely to be due to artifact than to an actual increase in aggressive cancers. In such cases, observed benefits must be weighed against theoretical harms in men who are being treated for symptomatic or bothersome conditions.

What is the impact of 5-ARIs on the need for treatment for benign prostatic disease?

5-ARIs are established, US Food and Drug Administration–approved treatments for symptomatic BPH. The systematic review of trials in men with established BPH confirmed the efficacy of this class of drugs for this condition. To date, only the PCPT provides information that directly addresses the impact of 5-ARIs in relatively asymptomatic men who do not require treatment of urinary tract symptoms. In the PCPT, the incidence of acute urinary retention was decreased by about one third in the finasteride arm (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.59 to 0.76; absolute rates, 6.3% v 4.2%). Consistent with this observation, the incidence of transurethral resection of the prostate was 1.9% in the placebo arm and 1.0% in the finasteride arm, a statistically significant decrease in the risk for surgical interventions.

What is the impact of 5-ARIs on quality of life? What are other potential harms and adverse effects of 5-ARIs? What are other potential benefits of, and indications for, 5-ARI use (eg, benign prostatic hyperplasia, male baldness)?

Benefits of 5-ARI.

The question of the impact of 5-ARIs on global quality of life is difficult to answer based on the available data. Studies of 5-ARIs have not assessed global or general health-related quality of life using traditional quality-of-life measures; rather, most studies have included measures of urinary symptoms (eg, urinary retention), sexual functioning (eg, erectile dysfunction), and/or endocrine effects (eg, gynecomastia). Mid- and long-term studies (6 months or beyond) with finasteride and dutasteride individually and in meta-analysis of studies that included men with underlying LUTS demonstrated a reduction in risk in acute urinary retention (from 5.6% to 3.3%; absolute risk difference, 2.3%) as well as a reduction in the need for surgical intervention (from 3.3% to 1.7%; absolute risk difference, 1.6%). The largest benefits were observed in men with a baseline PSA greater than 4 ng/mL (larger prostates). In addition, one RCT showed a statistically significant reduction in hematuria with finasteride compared with placebo.22

Adverse events.

5-ARIs are associated with a consistently higher frequency of adverse events than placebo, albeit of small absolute magnitude (Table 1). Virtually all RCTs show a 2% to 4% increase in reported erectile dysfunction and gynecomastia, and decreases in ejaculate volume and libido for the treatment arm. When all studies, mid- and long-term, were combined, the overall discontinuation or loss to follow-up rates for both the 5-ARI and placebo arms were approximately 15%. The combined discontinuation and loss to follow-up rate specifically secondary to adverse events was approximately 6% to 7% in studies in both the 5-ARI and placebo patients. When the PCPT specifically evaluated adverse events, there were more adverse effects causing temporary discontinuation in the finasteride arm (the investigators do not specifically define temporary in this setting). Sexual function and endocrine effects, which were more common in the 5-ARI arm (statistically significant), included decreased libido, decreased ejaculate volume, and gynecomastia. The sexual dysfunction associated with finasteride decreased over time, although it remained statistically significant. The magnitude of effect was smaller than natural sources of variability in the study population23; on a scale of 0 to 100 (a higher score indicates more sexual dysfunction), the largest effect of finasteride on sexual functioning was a difference (mean) of 3.21 points, compared with a difference of 1.26 points for each year of older age.

Table 1.

Adverse Effects

| Subgroup/Reference | 5-α-Reductase Inhibitor |

Placebo |

Relative Risk | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./Total No. | % | No./Total No. | % | |||

| Impotence/erectile dysfunction | ||||||

| Mid-term treatment duration (1 to 2 years) | ||||||

| ARIA/ARIB8 | 13/1,605 | 0.81 | 14/1,555 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.42 to 1.91 |

| FSG-American47 | 25/595 | 4.2 | 5/300 | 1.7 | 2.52 | 0.97 to 6.52 |

| FSG-International48 | 22/495 | 4.4 | 1/255 | 0.4 | 11.33 | 1.54 to 83.60 |

| PREDICT24 | 13/264 | 4.9 | 9/269 | 3.3 | 1.47 | 0.64 to 3.38 |

| PROSPECT41 | 49/310 | 15.8 | 19/303 | 6.2 | 2.52 | 1.52 to 4.18 |

| VA COOP25 | 29/310 | 9.4 | 14/305 | 4.6 | 2.04 | 1.10 to 3.78 |

| Long-term treatment duration (> 2 years) | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 6,349/9,423 | 67.4 | 5,816/9,457 | 61.5 | 1.10 | 1.07 to 1.12 |

| Total | 6,500/13,002 | 50.0 | 5,878/12,444 | 47.2 | 1.71 | 1.11 to 2.65 |

| Decreased/abnormal ejaculate volume | ||||||

| Mid-term treatment duration (1 to 2 years) | ||||||

| FSG-American47 | 26/595 | 4.4 | 5/300 | 1.7 | 2.62 | 1.02 to 6.76 |

| VA COOP25 | 6/310 | 1.9 | 4/305 | 1.3 | 1.48 | 0.42 to 5.18 |

| Long-term treatment duration (> 2 years) | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 5,690/9,423 | 60.4 | 4,473/9,457 | 47.3 | 1.28 | 1.24 to 1.31 |

| Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group36 | 23/1,524 | 1.5 | 8/1,516 | 0.53 | 2.86 | 1.28 to 6.37 |

| Total | 5,745/11,852 | 48.5 | 4,490/11,578 | 38.8 | 1.75 | 1.07 to 2.85 |

| Decreased libido | ||||||

| Mid-term treatment duration (1 to 2 years) | ||||||

| ARIA/ARIB8 | 91/2,167 | 4.2 | 46/2,158 | 2.1 | 1.97 | 1.39 to 2.79 |

| FSG-American47 | 32/595 | 5.4 | 4/300 | 1.3 | 4.03 | 1.44 to 11.30 |

| PREDICT24 | 9/264 | 3.4 | 5/269 | 1.9 | 1.83 | 0.62 to 5.40 |

| PROSPECT41 | 31/310 | 10.0 | 19/303 | 6.2 | 1.59 | 0.92 to 2.76 |

| VA COOP25 | 14/310 | 4.5 | 4/305 | 1.3 | 3.44 | 1.15 to 10.34 |

| Long-term treatment duration (> 2 years) | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 6,163/9,423 | 65.4 | 5,635/9,457 | 59.6 | 1.10 | 1.07 to 1.12 |

| Total | 6,340/13,069 | 48.5 | 5,713/12,792 | 44.7 | 1.83 | 1.19 to 2.81 |

| Gynecomastia | ||||||

| Mid-term treatment duration (1 to 2 years) | ||||||

| ARIA/ARIB8 | 50/2167 | 2.3 | 16/2158 | 0.74 | 3.11 | 1.78 to 5.45 |

| Long-term treatment duration (> 2 years) | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 426/9,423 | 4.5 | 261/9,457 | 2.8 | 1.64 | 1.41 to 1.91 |

| Total | 476/11,590 | 4.1 | 277/11,615 | 2.4 | 2.13 | 1.15 to 3.95 |

| Incontinence | ||||||

| Long-term treatment duration (> 2 years) | ||||||

| MTOPS trial10 | 7/768 | 0.91 | 6/737 | 0.81 | 1.12 | 0.38 to 3.32 |

| PCPT5 | 183/9,423 | 1.9 | 208/9,457 | 2.2 | 0.88 | 0.73 to 1.07 |

| Total | 190/10,191 | 1.9 | 214/10,194 | 2.1 | 0.89 | 0.73 to 1.08 |

| Increased urinary frequency/urgency | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 1,214/9,423 | 12.9 | 1,474/9,457 | 15.6 | 0.83 | 0.77 to 0.89 |

Abbreviations: FSG, Finasteride Study Group; PREDICT, Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy trial; PROSPECT, Proscar Safety Plus Efficacy Canadian Two-Year study; VA COOP, Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies BPH Study Group; PCPT, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; MTOPS, Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms trial.

Adapted with permission from the Cochrane Collaboration.

In trials comparing 5-ARIs to an alpha blocker for the management of LUTS, discontinuation rates were similar in the two groups. Dizziness and postural hypertension were statistically more frequent among patients receiving 5-α blocker therapy.10,24,25

5-ARIs effect on PSA.

The decrease in PSA levels by 5-ARIs must be taken into account when judging the significance of a PSA level. In the PCPT, finasteride lowered the PSA by 50% after 12 months of therapy, and therefore a multiplier of 2 was used as a criterion for biopsy. The effects of 5-ARIs on PSA before 12 months are variable. In the PCPT, the decline at 3 years was greater than 50% which was adjusted by changing the 2 multiplier in the finasteride arm to 2.3.

A single study has investigated the changes in PSA level caused by a 1-mg dose, as is used in treatment of male pattern baldness.26 For men age 50 years and older, 1 mg of finasteride had an effect similar to 5 mg (50% decrease) at the 1-year follow-up date. Information beyond 1 year is not available.

Dutasteride inhibits both the type 1 and type 2 isoforms of 5-α reductase and causes a greater and more consistent decrease in DHT. The amount of PSA suppression with long-term dutasteride treatment has not been reported.

In conclusion, a consistently uniform scale multiplier is currently unavailable because of inter- and intraindividual variability of PSA levels, laboratory variables, variable compliance of patients with regard to drug schedule, and a paucity of data relating change of PSA to duration of therapy. No specific cut point or change in PSA has been prospectively validated in men taking a 5-ARI.

What is the treatment duration required for best outcome (period versus lifelong)?

No trial has directly compared different durations of 5-ARIs for the prevention of prostate cancer. The PCPT was the only reported trial designed to test the efficacy of a 5-ARI (finasteride) for preventing prostate cancer. It is also the most reliable trial for directly comparing the benefits and harms of finasteride in the most likely target population for interventions to prevent prostate cancer. Given that finasteride was administered for a planned 7 years, the Panel judged that until additional information is available, finasteride should be given for 7 years if used for primary prevention. One ongoing trial13 compares dutasteride with placebo for preventing prostate cancer. Dutasteride is administered for 4 years in that trial, so the results of the trial should help address the question of whether a shorter duration of a 5-ARI prevents prostate cancer.

What are the future directions of research regarding 5-ARIs for the prevention of prostate cancer?

The goal of developing a chemopreventive agent that can reduce the risk of prostate cancer has been achieved. Nevertheless, despite the availability of one large and well-designed trial (PCPT) and an ongoing large trial (REDUCE) to test the efficacy of finasteride and dutasteride, respectively, for the primary prevention of prostate cancer, important questions and directions for research remain. The critical question regarding the effect of 5-ARIs on prostate cancer morbidity and mortality is yet to be answered: is the observed increase in higher grade prostate cancers in men receiving finasteride in the PCPT real or artifactual? Additional investigation is necessary, and the results of REDUCE will aid in this assessment.

The dose of finasteride currently being used to treat male pattern baldness is 1 mg per day rather than the 5 mg per day used in the PCPT. It is unknown if a 1-mg dose is as effective as 5 mg in reducing the risk of prostate cancer. If the lower dose is just as effective, the balance of benefits and harms would be more favorable. All of this information would be critical to making more reliable estimates of cost effectiveness of 5-ARIs for preventing prostate cancer. It would also be important to know whether 5-ARIs reduce the incidence of clinically detected cancer among men who are not being actively screened. This would be especially pertinent should the ongoing randomized trials of prostate cancer screening (Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, Ovary [PLCO] Screening Study; European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer [ERSPC]) show that prostate cancer screening does not decrease prostate cancer mortality or that the harms of screening outweigh the benefits. In addition, as mentioned above, men taking a 5-ARI are expected to experience a roughly 50% reduction in PSA by 12 months; however, because these changes in PSA may vary across men, and within individual men over time, the Panel cannot recommend a specific cut point to trigger a biopsy for men taking a 5-ARI. This is an important topic for future research.

Behavioral and communication research is needed on the type and effectiveness of information for men considering the use of a 5-ARI for prevention of prostate cancer and for men who are already taking a 5-ARI for other indications. More generally, as models incorporating molecular data evolve, risk-stratification models may be developed to tailor individual preventive therapy. Such models may include individuals with germline susceptibility at heightened risk for developing prostate cancer, especially earlier onset disease or as a second malignancy.

PHYSICIAN-PATIENT COMMUNICATION

Although the decision to embark on a preventive 5-ARI regimen belongs in the final analysis to the individual, the physician has an important role. For the man who is considering the use of these agents for prostate cancer prevention, it is essential that the physician present the available data and highlight the remaining uncertainty.

5-ARIs do not eliminate the risk of developing prostate cancer; they reduce its clinical incidence. This distinction should be made clear. The advisability of the drug as a chemopreventive agent depends on an estimate of probabilities—of risk. As yet, there is no widely established decision model or aid that can help a man of age 50 or 60 years determine if he is well advised to take a 5-ARI. Thompson et al27,28 have developed a prostate cancer risk calculator based on risk equations generated from the PCPT data that may have clinical applications. The risk calculator is applicable to men who are similar to those who participated in the PCPT: at least 50 years of age, no prior prostate cancer diagnosis, and PSA and DRE results that are less than 1 year old. The calculator provides a preliminary assessment of prostate cancer risk and the risk of high-grade prostate cancer if a prostate biopsy is performed, and was recently validated in a more ethnically diverse and a younger population than that studied in the PCPT.29 The calculator is accessible at http://www.compass.fhcrc.org/edrnnci/bin/calculator/main.asp?tx=prostate&subx=disclaimer&vx=prostate&mx=&x=Prostate%20Cancer.

It is uncertain whether the findings of increased high-grade cancers on the finasteride arm of the PCPT are actually an artifact of the methodology of the PCPT itself, as many believe. Until that risk is better elucidated, physicians should be explicit about the uncertainties. In addition, it is important to point out that the impact of 5-ARIs on prostate cancer mortality is unknown, given that the PCPT was not designed to address this question. Nevertheless, it is clear that a 5-ARI does convey benefits to some men, as it decreases the overall incidence of prostate cancer and also prevents urinary tract obstruction in some men.

In communicating the present state of knowledge about the risks and benefits of 5-ARIs, it may be helpful to use the model of a cohort of 1,000 men taking 5-ARIs for 7 years. Based on the systematic review by Wilt et al,14 it is estimated that 5-ARIs will result in a reduction of 15 prostate cancer cases in this group of 1,000 men, and in a possible increase of three cases of high-grade cancer after approximately 7 years of therapy.

Men also should be informed that no information on the long-term effects of 5-ARIs exists beyond approximately 7 years, and that whether or not the reduction in prostate cancer incidence will translate into a reduction in prostate cancer mortality or longer life expectancy remains unknown.

Physicians should inform men who are considering a 5-ARI about the incidence of sexual adverse effects. Such adverse effects as lowered libido associated with a 5-ARI have been reported consistently, but they are also reversible. The benefits of a 5-ARI in reducing BPH are also appreciable and unequivocal. It has been suggested that the ideal candidate for a 5-ARI regimen would be an individual who is “concerned about the development of prostate cancer, has a higher-than-average risk of the disease, has urinary symptoms that may be relieved by finasteride, and is not sexually active.”30

In summary, it is recommended that the physician:

inform the man who is considering a 5-ARI that these agents reduce the incidence of prostate cancer, and be sure to be clear that these agents do not reduce the risk of prostate cancer to zero;

discuss the elevated rate of high-grade cancer observed in the PCPT and inform men of the potential explanations;

make it known to men that no information on the long-term effects of 5-ARIs on prostate cancer incidence exists beyond approximately 7 years, and that whether or not a 5-ARI reduces prostate cancer mortality or increases life expectancy remains unknown;

inform men of possible but reversible sexual adverse effects; and

inform men of the likely improvement in lower urinary tract symptoms.

LIMITATIONS OF THE LITERATURE

Despite high-quality evidence from randomized trials, the data have limitations. Only one trial reported to date (PCPT) was specifically designed to measure the effect of a 5-ARI on the incidence of prostate cancer; it was not designed with sufficient power to assess the effect of 5-ARIs on the risk of prostate cancer death. To develop a complete assessment of the benefit of 5-ARIs, one would need to know the proportion of cancers finasteride prevents that are truly clinically meaningful. The current literature cannot provide an estimate of this proportion; in particular, data are lacking on clinically meaningful cancers in the age group under consideration (men older than 50 years). A recent analysis of PCPT characterized 34% of cancers as clinically insignificant by histologic criteria, a rate similar to contemporary series of men who undergo treatment.21 Many cancers prevented by finasteride might never have caused harm, as suggested by the fact that screening leads to substantial overdiagnosis of nonlethal cancers. Overdiagnosis can increase substantially with a lowering of the PSA threshold for prostatic biopsy or an increase in the number of systematic biopsies of the prostate. Overdiagnosis is likely to decrease if ongoing randomized prostate cancer screening trials show a net harm from screening. Therefore, the clinical importance of the prostate cancers diagnosed in existing and ongoing chemoprevention trials is difficult to interpret. The Panel attempted to focus on cancers that were most likely to be of clinical importance (for-cause cancers as described in Methods). One of the most serious limitations in the current literature is the changes that occur in standards for PSA thresholds, criteria for biopsy, and biopsy methods. Continuing changes may alter all evaluations of outcomes.

Although not specifically within the scope of this document, the Panel did review studies on cost effectiveness. Two analyses31,32 have been published on the cost effectiveness of finasteride for prostate cancer prevention using the period prevalence observed in the PCPT and making a variety of unverifiable assumptions about the impact of the diagnosed cancers on prostate cancer mortality and the tumor grade–specific lethality of the cancers detected. The results of the cost-effectiveness analyses were highly dependent on assumptions regarding whether the observed increase in high-grade tumors was real or artifactual, and on the cost of drug. As extensively discussed above, the first assumption cannot be tested. Therefore, the Panel concluded that any assessment of cost effectiveness at this point is unreliable and impossible to incorporate into the decision of whether or not to take 5-ARIs for lowering the risk of prostate cancer.

SUMMARY OF DESIRED OUTCOMES AND INTERPRETIVE SUMMARY

For the man who wishes periodic monitoring (opportunistic or organized screening), 5-ARI therapy during a 7-year period reduces the period prevalence of for-cause cancer diagnoses by approximately 25% (relative risk reduction) for an absolute risk reduction of about 1.4%. Although the majority of the Panel judged that the observed higher incidence of high-grade (Gleason score 8 to 10) cancer in the finasteride group is likely due to confounding factors, the increased incidence of high-grade cancer as a result of induction by the drug cannot be excluded with certainty. Additional benefits accruing from the drug are reduction of the risk of urinary retention and need for surgical intervention. Harms include sexual adverse effects, which usually diminish with time.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The Expert Panel thanks Erik Busby, MD, William Dahut, MD, Bernard Levin, MD, Ethan Basch, MD, J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, MD, Dean F. Bajorin, MD, Bruce J. Roth, MD, the ASCO Health Services Committee and Board of Directors and the AUA Practice Guidelines Committee, Board of Directors and staff, Edie Budd, and Heddy Hubbard, PhD.

Appendix

Table A1.

5-α-Reductase Inhibitors Panel Members

| Panel Member | Institution |

|---|---|

| Barnett Kramer, MD, Co-Chair | National Institutes of Health |

| Paul Schellhammer, MD, Co-Chair | Eastern Virginia Medical School |

| Stewart Justman, PhD, Patient Representative | University of Montana Liberal Studies |

| Peter C. Albertsen, MD | University of Connecticut Health Center |

| William J. Blot, PhD | International Epidemiology Institute, Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center |

| H. Ballentine Carter, MD | Johns Hopkins University |

| Joseph P. Costantino, PhD | National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project |

| Jonathan I. Epstein, MD | Johns Hopkins University |

| Paul A.Godley, MD, PhD | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Russell P. Harris, MD, MPH | University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

| Timothy J. Wilt, MD, MPH | Minneapolis VA Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes Research |

| Janet Wittes, PhD | Statistics Collaborative |

| Robin Zon, MD | Michiana Hematology Oncology |

Table A2.

Characteristics for 5-ARI Studies

| Study (references) and Interventions (dose/d) | No. of Randomly Assigned Patients | Treatment Duration (years) | Baseline Demographic Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term trials (> 2 years) | ||||

| PCPT5 | 7 (± 90 days) | American men enrolled onto a prostate cancer prevention trial | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 9,423 | Age, 45-64 years, 62%; ≥ 65 years, 38% | ||

| Placebo | 9,459 | Race/ethnicity: white, 92%; black, 3.8%; Hispanic, 2.6%; other, 1.5% | ||

| PSA (ng/mL), ≤ 3: 100% | ||||

| Family history of PCa (first-degree relative): 15.4% | ||||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 6.7 (SD, 4.8) | ||||

| MTOPS10,33 | 4.5 | American men, mean age 62.6 (SD, 7.3), with LUTS secondary to BPH | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 768 | Race/ethnicity: white, 82.3%; black, 8.9%; Hispanic, 7.3%; other, 1.5% | ||

| Doxazosin, 4-8 mg | 756 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 2.4 (SD, 2.1) | ||

| Combination finasteride and doxazosin | 786 | Mean prostate volume (mL): 36.3 (SD, 20.1) | ||

| Placebo | 737 | Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 16.9 (SD, 5.9) | ||

| PLESS9,34–37 | 4.0 | American men, mean age 64 years (SD, 6.4), with LUTS secondary to BPH | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 1,524 | Race: white 95.5% | ||

| Placebo | 1,516 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 2.8 (SD, 2.1). | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 15 (SD, 5.7). | ||||

| History of sexual dysfunction: 46% of men in each group at screening | ||||

| Moderate-term trials (1-2 years) | ||||

| ARIA/ARIB 3001, 3002, 30038,38–40 | 2.0 | Multinational men, mean age 66.3 years, with LUTS secondary to BPH (all participants had IPSS ≥ 12) | ||

| Dutasteride, 0.5 mg | 2,167 | Race/ethnicity: white, 92%; black, 4%; Hispanic, 7.3%; Asian, 1%; other, 1.5% | ||

| Placebo | 2,158 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 4.0 (SD, 2.1) | ||

| Mean prostate volume (cm3): 54.5 | ||||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 17.05 | ||||

| PROSPECT41 | 2.0 | Canadian men in good health, mean age, 63.3 years (range, 46 to 80 years) with LUTS secondary to BPH | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 310 | Race: NR | ||

| Placebo | 303 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): NR | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 16.2 | ||||

| PREDICT24 | 1.0 | European men, mean age, 64 years (range, 50 to 80 years), with LUTS secondary to BPH (all participants had IPSS ≥ 12) | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 264 | Race: NR | ||

| Doxazosin, 4-8 mg | 275 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 2.6 | ||

| Combination finasteride and doxazosin | 286 | Mean prostate volume (g): 36 | ||

| Placebo | 270 | Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 17.2 | ||

| VA Coop (Johnson, 2003; a subset of subjects from Lepor 1996)25,42 | 1.0 | American men, mean age 65 years, with symptomatic BPH | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 252 | Race: white 80% | ||

| Terazosin, 10 mg | 262 | Race/ethnicity (from Lepor): white, 87%; black, 11%; Asian, 1%; Native American, 0.5% | ||

| Combination finasteride and terazosin | 272 | Mean PSA (from Lepor; ng/mL): 2.3 | ||

| Placebo | 254 | Mean prostate volume (g): 37.6 | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 16.1 | ||||

| Foley, 200022 | 1.0 | British men, mean age, 77.5 years (range, 55 to 89 years), with hematuria associated with BPH | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 29 | Race: NR | ||

| Watchful waiting | 28 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): NR | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: NR | ||||

| Cote, 199843 | 1.0 | American men age ≥ 50 years (mean, 68 years) with elevated PSA (> 4.0 ng/mL); study objective was to examine effect of finasteride on prostate cellular proliferation and high-grade PIN | ||

| Observation (watchful waiting) | 29 | Race: NR | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 29 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 9.8 | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: NR | ||||

| Pre-existing high-grade PIN: observation, 5 men; Finasteride, 8 men | ||||

| FSG44–48 | American and international men; mean age, 64.9 years (range, 40 to 83 years) with BPH | |||

| Finasteride, 1 mg | 547 | Race/ethnicity: white, 95.8%; black, 1.6%; other, 2.6%. | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 543 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 4.7 | ||

| Placebo | 555 | Mean prostate volume (cm3): 55.0 | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: NR | ||||

| Short-term trials (< 1 year) | ||||

| ARIA 200149 | 0.5 | American and Canadian men age ≥ 50 years (mean, 62.6 to 65.5 years across groups), with LUTS secondary to BPH; study objective was to examine effect of dutasteride on serum dihydrotestosterone levels | ||

| Dutasteride, 0.01, 0.05, 0.5, 2.5, and 5 mg | 285 | Race: NR | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 55 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): NR | ||

| Placebo | 59 | Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: NR | ||

| MICTUS50 | 0.5 | Italian men, mean age, 63 years (SD, 7.1 years), with LUTS secondary to BPH (all participants had IPSS ≥ 13) | ||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 204 | Race: NR | ||

| Tamsulosin, 0.4 mg | 199 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): NR | ||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: NR | ||||

| Lee, 200251 | Korean men, mean age, 64.7 years, with LUTS secondary to BPH (all participants had Korean IPSS > 8) | |||

| Finasteride, 5 mg | 102 | Race: Asian, 100% | ||

| Tamsulosin, 0.2 mg | 103 | Mean PSA (ng/mL): 2.0 | ||

| Mean prostate volume (cm3): 29.8 | ||||

| Mean baseline AUA/IPSS score: 19.5 |

Abbreviations: 5-ARI, 5-α-reductase inhibitor; PCPT, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PCa, prostate cancer; AUA/IPSS, American Urological Association/International Prostate Symptom Score; SD, standard deviation; NR, not reported; MTOPS, Medical Therapy of Prostatic Symptoms; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; PLESS, Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study; SD, standard deviation; NR, not reported; PREDICT, Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy; PIN, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia; FSG, Finasteride Study Group; MICTUS, Multicentre Investigation to Characterise the Effect of Tamsulosin on Urinary Symptoms.

Table A3.

Period Prevalence of Prostate Cancer According to Subgroup

| Subgroup/Reference | 5-α-Reductase Inhibitor |

Placebo |

Relative Risk | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No./Total No. of Patients | % | No./Total No. of Patients | % | |||

| PSA at study entry: 0.0 to < 4.0 ng/mL | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 803/9,423 | 8.5 | 1,147/9,456 | 12.1 | 0.70 | 0.64 to 0.77 |

| PLESS 36 | 28/1,149 | 2.4 | 32/1,154 | 2.8 | 0.88 | 0.53 to 1.45 |

| Total | 831/10,572 | 7.9 | 1,179/10,610 | 11.1 | 0.71 | 0.65 to 0.77 |

| PSA at study entry: ≥ 4.0 ng/mL | ||||||

| Cote43 | 8/27 | 29.6 | 1/25 | 4.0 | 7.41 | 1.00 to 55.09 |

| PLESS36 | 44/374 | 11.8 | 45/357 | 12.6 | 0.93 | 0.63 to 1.38 |

| Total | 52/401 | 13.0 | 46/382 | 12.0 | 2.08 | 0.28 to 15.43 |

| Gleason score 7 | ||||||

| PCPT5 | 190/9,423 | 2.0 | 184/9,459 | 1.9 | 1.04 | 0.85 to 1.27 |

| PLESS36 (estimated from graph) | 11/1,524 | 0.72 | 12/1,516 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.40 to 2.06 |

| Total | 201/10,947 | 1.8 | 196/10,975 | 1.9 | 1.03 | 0.85 to 1.25 |

| Gleason score 7: PCPT5 | ||||||

| PCa overall/number randomized | 190/9,423 | 2.0 | 184/9,459 | 1.9 | 1.04 | 0.85 to 1.27 |

| PCa overall/included in analysis | 190/4,368 | 4.3 | 184/4,692 | 3.9 | 1.11 | 0.91 to 1.35 |

| PCa detected for cause/number randomized | 118/9,423 | 12.5 | 103/9,459 | 10.9 | 1.15 | 0.88 to 1.50 |

| PCa detected for cause/biopsy performed for cause | 118/1,639 | 7.2 | 103/1,934 | 5.3 | 1.35 | 1.05 to 1.75 |

| Gleason scores 8 to 10 | ||||||

| PCPT(5) | 90/9,423 | 0.96 | 53/9,459 | 0.56 | 1.70 | 1.22 to 2.39 |

| PLESS36 (estimated from graph) | 1/1,524 | 0.07 | 7/1,516 | 0.46 | 0.14 | 0.02 to 1.15 |

| Gleason scores 8 to 10: PCPT5 | ||||||

| PCa overall/No. randomly assigned | 90/9,423 | 0.96 | 53/9,459 | 0.56 | 1.70 | 1.22 to 2.39 |

| PCa overall/No. included in analysis | 90/4,368 | 2.1 | 53/4,692 | 1.1 | 1.82 | 1.30 to 2.55 |

| PCa detected for cause/No. randomly assigned | 70/9,423 | 0.74 | 45/9,459 | 0.48 | 1.56 | 1.07 to 2.27 |

| PCa detected for cause/No. with biopsy performed for cause | 70/1,639 | 4.3 | 45/1,934 | 2.3 | 1.84 | 1.27 to 2.65 |

| Age, years: PCPT5 | ||||||

| 55 to 59 | 205/2,954 | 6.9 | 309/2,954 | 10.5 | 0.66 | 0.56 to 0.79 |

| 60 to 64 | 254/2,970 | 8.6 | 357/2,825 | 12.6 | 0.68 | 0.58 to 0.79 |

| ≥ 65 | 344/3,498 | 9.8 | 481/3,677 | 13.1 | 0.75 | 0.66 to 0.86 |

| Race/ethnicity: PCPT5 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 739/8,667 | 8.5 | 1067/8,713 | 12.2 | 0.70 | 0.64 to 0.76 |

| African-American | 41/356 | 11.5 | 50/353 | 14.2 | 0.81 | 0.55 to 1.20 |

| Hispanic | 19/262 | 7.3 | 23/237 | 9.7 | 0.75 | 0.42 to 1.34 |

| Family history of PCa in first-degree relative: PCPT5 | ||||||

| Yes | 176/1,458 | 12.1 | 241/1,455 | 16.6 | 0.73 | 0.61 to 0.87 |

| No | 627/7,965 | 7.9 | 906/8,002 | 11.3 | 0.70 | 0.63 to 0.77 |

Abbreviations: PSA, prostate-specific antigen; PCPT, Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial; PLESS, Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study; PCa, prostate cancer.

Footnotes

Approved by the American Society of Clinical Oncology Board on July 21, 2008, and by the American Urological Association Board on October 17, 2008.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Peter C. Albertsen, GlaxoSmithKline (C); Paul A. Godley, GlaxoSmithKline (C); Janet Wittes, Merck (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Barnett S. Kramer, Timothy J. Wilt, Robin Zon, Paul Schellhammer

Administrative support: Karen L. Hagerty, Mark R. Somerfield

Collection and assembly of data: Barnett S. Kramer, Karen L. Hagerty, Mark R. Somerfield, Timothy J. Wilt, Paul Schellhammer

Data analysis and interpretation: Barnett S. Kramer, Karen L. Hagerty, Stewart Justman, Peter C. Albertsen, H. Ballentine Carter, Joseph P. Costantino, Jonathan I. Epstein, Paul A. Godley, Timothy J. Wilt, Janet Wittes, Paul Schellhammer

Manuscript writing: Barnett S. Kramer, Karen L. Hagerty, Stewart Justman, Mark R. Somerfield, Peter C. Albertsen, Joseph P. Costantino, Jonathan I. Epstein, Timothy J. Wilt, Janet Wittes, Robin Zon, Paul Schellhammer

Final approval of manuscript: Barnett S. Kramer, Stewart Justman, Peter C. Albertsen, William J. Blot, H. Ballentine Carter, Joseph P. Costantino, Jonathan I. Epstein, Paul A. Godley, Russell P. Harris, Timothy J. Wilt, Janet Wittes, Robin Zon, Paul Schellhammer

REFERENCES

- 1.Chlebowski RT, Sayre J, Frank-Stromborg M, et al. Current attitudes and practice of American Society of Clinical Oncology-member clinical oncologists regarding cancer prevention and control. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:164–168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ganz PA, Kwan L, Somerfield MR, et al. The role of prevention in oncology practice: Results from a 2004 survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2948–2957. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: Report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for the prevention of breast cancer: Current status of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1652–1662. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thompson IM, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, et al. The influence of finasteride on the development of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:215–224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–2741. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AUA guideline on management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Chapter 1: Diagnosis and treatment recommendations. J Urol. 2003;170:530–547. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000078083.38675.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, Nickel JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2002;60:434–441. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)01905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan S, Garvin D, Gilhooly P, et al. Impact of baseline symptom severity on future risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia-related outcomes and long-term response to finasteride: The Pless Study Group. Urology. 2000;56:610–616. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00724-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein EA, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, et al. Assessing benefit and risk in the prevention of prostate cancer: The prostate cancer prevention trial revisited. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7460–7466. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talcott JA. Rebalancing ratios and improving impressions: Later thoughts from the prostate cancer prevention trial investigators. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7388–7390. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andriole G, Bostwick D, Brawley O, et al. Chemoprevention of prostate cancer in men at high risk: Rationale and design of the reduction by dutasteride of prostate cancer events (REDUCE) trial. J Urol. 2004;172:1314–1317. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000139320.78673.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilt T, MacDonald R, Hagerty K, et al. 5-α-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(issue 2) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007091. art. No. CD007091. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lippman SM, Levin B, Brenner DE, et al. Cancer prevention and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3848–3851. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welch HG. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2004. Should I Be Tested for Cancer? Maybe Not and Here's Why. pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucia MS, Epstein JI, Goodman PJ, et al. Finasteride and high-grade prostate cancer in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1375–1383. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen YC, Liu KS, Heyden NL, et al. Detection bias due to the effect of finasteride on prostate volume: A modeling approach for analysis of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1366–1374. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redman MW, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, et al. Finasteride does not increase the risk of high-grade prostate cancer: A bias-adjusted modeling approach. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:174–181. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson IM, Chi C, Ankerst DP, et al. Effect of finasteride on the sensitivity of PSA for detecting prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1128–1133. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucia MS, Darke AK, Goodman PJ, et al. Pathologic characteristics of cancers detected in the prostate cancer prevention trial: implications for prostate cancer detection and chemoprevention. Cancer Prev Res. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0078. [epub ahead of print on May 18, 2008] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foley SJ, Soloman LZ, Wedderburn AW, et al. A prospective study of the natural history of hematuria associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia and the effect of finasteride. J Urol. 2000;163:496–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moinpour CM, Darke AK, Donaldson GW, et al. Longitudinal analysis of sexual function reported by men in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1025–1035. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirby RS, Roehrborn C, Boyle P, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of doxazosin and finasteride, alone or in combination, in treatment of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: The Prospective European Doxazosin and Combination Therapy (PREDICT) trial. Urology. 2003;61:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lepor H, Williford WO, Barry MJ, et al. The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia: Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:533–539. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Amico AV, Roehrborn CG. Effect of 1 mg/day finasteride on concentrations of serum prostate-specific antigen in men with androgenic alopecia: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:21–25. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70981-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, et al. Assessing prostate cancer risk: Results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–534. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson IM, Pauler Ankerst D, Chi C, et al. Prediction of prostate cancer for patients receiving finasteride: Results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3076–3081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.6836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parekh DJ, Ankerst DP, Higgins BA, et al. External validation of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial risk calculator in a screened population. Urology. 2006;68:1152–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zuger A. A big study yields big questions. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:213–214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svatek RS, Lee JJ, Roehrborn CG, et al. The cost of prostate cancer chemoprevention: A decision analysis model. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1485–1489. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeliadt SB, Etzioni RD, Penson DF, et al. Lifetime implications and cost-effectiveness of using finasteride to prevent prostate cancer. Am J Med. 2005;118:850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan SA, McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, et al. Combination therapy with doxazosin and finasteride for benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and a baseline total prostate volume of 25 ml or greater. J Urol. 2006;175:217–220. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00041-8. discussion 220-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paick SH, Meehan A, Lee M, et al. The relationship among lower urinary tract symptoms, prostate specific antigen and erectile dysfunction in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results from the Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study. J Urol. 2005;173:903–907. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152088.00361.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wessells H, Roy J, Bannow J, et al. Incidence and severity of sexual adverse experiences in finasteride and placebo-treated men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2003;61:579–584. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02401-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andriole GL, Guess HA, Epstein JI, et al. Treatment with finasteride preserves usefulness of prostate-specific antigen in the detection of prostate cancer: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. PLESS Study Group—Proscar Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study. Urology. 1998;52:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00184-8. discussion 201-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McConnell JD, Bruskewitz R, Walsh P, et al. The effect of finasteride on the risk of acute urinary retention and the need for surgical treatment among men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: Finasteride Long-Term Efficacy and Safety Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:557–563. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802263380901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andriole GL, Roehrborn C, Schulman C, et al. Effect of dutasteride on the detection of prostate cancer in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2004;64:537–541. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.04.084. discussion 542-543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andriole GL, Kirby R. Safety and tolerability of the dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor dutasteride in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 2003;44:82–88. doi: 10.1016/s0302-2838(03)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Leary MP, Roehrborn C, Andriole G, et al. Improvements in benign prostatic hyperplasia-specific quality of life with dutasteride, the novel dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor. BJU Int. 2003;92:262–266. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nickel JC, Fradet Y, Boake RC, et al. Efficacy and safety of finasteride therapy for benign prostatic hyperplasia: Results of a 2-year randomized controlled trial (the PROSPECT study)—PROscar Safety Plus Efficacy Canadian Two year Study. CMAJ. 1996;155:1251–1259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]