Abstract

Purpose

To examine the prevalence and correlates of physical activity in adult survivors of aggressive non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (NHL) and to explore the association between physical activity level and health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Patients and Methods

Physical activity and HRQOL data from 319 survivors of NHL (mean age, 59.8 years, standard deviation, ±14.8) who were diagnosed in Los Angeles County approximately 2 to 5 years before the study was analyzed.

Results

One quarter of survivors of NHL met public health guidelines of 150 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous exercise per week. More than half (53%) reported some activity but less than 150 minutes per week, whereas 20% reported no physical activity. Females, those with lower perceived health competence, and individuals with more comorbid limitations were at increased risk for inactivity. Individuals who met public health guidelines reported better HRQOL than those who were sedentary. Interestingly, our findings suggest a significant positive association between HRQOL and those who get at least some exercise.

Conclusion

The effort to promote physical activity among cancer survivors, who are at risk for poor quality of life as a result of treatment, is of great importance to the health of this growing population. As NHL, similar to other cancers, becomes a disease that people live with as opposed to one that people die as a result of, oncologists and primary care physicians will be increasingly challenged to provide evidence-based guidance for the long-term management of the patient's health. Consideration should be given to how clinicians frame exercise-promoting messages to cancer survivors, especially to those who are sedentary.

INTRODUCTION

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (NHL) is one of the fastest increasing cancers and is currently the fifth most common cancer in the United States.1,2 Approximately half of all adult patient cases of NHL are aggressive lymphomas, which grow relatively quickly and can be fatal within months without appropriate treatment.3 Aggressive NHLs are commonly treated with intense protocols that include multiagent chemotherapy regimens with or without radiation and, potentially, bone marrow/stem-cell transplantation (BMT/SCT).3 Such aggressive therapies often produce significant acute and chronic adverse effects, and it is not uncommon for survivors of NHL to report profound deficits in health-related quality of life (HRQOL) even years after completion of treatment.4–7 These findings join a larger body of research that suggests cancer survivors are at an increased risk for adverse HRQOL, secondary tumors, recurrence, and other chronic illnesses as a result of their medical treatments.8–14

Several studies have shown exercise to be effective at improving HRQOL in cancer survivors in addition to physiologic outcomes.15–23 With few exceptions,24–27 the majority of this research is limited to survivors of breast cancer or samples that represent heterogeneous cancer sites. Moreover, much of this work has focused on the utility of physical activity at improving HRQOL during active treatment or short-term recovery after treatment. Several recent reviews22,23,28 identify the need to expand research on physical activity in cancer to samples other than survivors of breast cancer and to recommend examination of the impact of exercise on health outcomes in longer-term survivors.

To our knowledge, one study has examined the association between physical activity and HRQOL among post-treatment survivors of NHL (58.2% with indolent disease).26 However, no study has exclusively examined the association between physical activity and HRQOL in survivors of aggressive NHL who tend to receive more intense treatments and who are at higher risk for adverse HRQOL. In addition, as is typically done in descriptive studies of exercise prevalence and HRQOL, this study classified each participant as having either met physical activity guidelines (150 minutes or more of moderate-to-vigorous exercise per week) or not.29 It is not clear from existing research whether engaging in some exercise, despite not meeting current public health recommendations, has any benefit in terms of improved HRQOL among survivors of NHL in particular and among cancer survivors in general.

In addition to understanding the association between exercise and HRQOL, it is important to examine demographic and psychosocial correlates so that health promotion interventions can be developed for specific at-risk groups. For instance, research has shown lower levels of exercise in survivors of breast cancer who have lower education and in African American women compared with other groups.30 Other research has shown that younger age is associated with better exercise adherence in survivors of prostate cancer.31 Additional factors that predict physical activity, besides demographics, have received limited attention in longer-term survivors, including cognitive health appraisal factors, such as perceptions of control and health competence. The inclusion of these two variables have theoretical32 and empiric support33,34 as important constructs that may help explain who is more or less likely to engage in regular exercise.

The aims of this study were to examine the level of physical activity (ie, sedentary; 1 to 149 minutes per week; or ≥ 150 minutes per week) in survivors of aggressive NHL; to examine demographic, disease-related, and cognitive factors associated with level of sedentary physical activity; and to explore the association between physical activity level and HRQOL. We hypothesized that older survivors and those who had more comorbid limitations, lower perceived control, and health competence would be less likely to meet public health exercise guidelines; and that survivors of aggressive NHL who engaged in at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise per week would report better HRQOL than those who did not. We had no a priori hypothesis regarding the relationship between survivors who engage in some exercise and those who are sedentary given the extant literature.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Participants and Procedures

Study participants were men and women enrolled in the Experience of Care and Health Outcomes of Survivors of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma (ECHOS-NHL) study, which is a population-based, cross-sectional study of adult survivors of aggressive NHL. The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of Southern California, in accord with an assurance filed with and approved by the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Details of the study design and recruitment procedures are published elsewhere.7,35 In brief, men and women were recruited from the Los Angeles Cancer Surveillance (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER]) Program. Of the 1,025 selected patient cases, 744 were eligible after those who were deceased (n = 109), were too ill (n = 36), were unable to understand English (n = 80), had another cancer (n = 36), or were otherwise ineligible (n = 13; eg, not Los Angeles county resident, prisoner, misdiagnosis) were eliminated. In total, there were 408 completed questionnaires, which provided a response rate of 54.8% of those eligible (ie, 408 of 744) and a participation rate of 72.5% on the basis of eligible patient cases located (ie, 181 of 744 were lost to follow-up). Eighty-nine of the 408 patient cases completed the survey by telephone. The method of completion (phone v mail) was not significantly associated with the patient's age, sex, ethnicity, histology, HIV status, or year of diagnosis. Respondents who chose a phone interview were not given the full set of measures (ie, excluded HRQOL and physical activity) because of the length of administration. The final sample for analyses in this study was based on the 319 respondents who completed the questionnaire by mail.

Measures

Demographic and disease characteristics.

Sociodemographic information included sex, age, ethnicity, marital status, education, and health insurance. Health-related characteristics included type of treatment, NHL grade, time since diagnosis, comorbid limitations, and body mass index (BMI; normal, 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2; overweight, 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2; obese, ≥ 30 kg/m2).

Physical activity.

Respondents completed information on the number of times per week (once, two to four, five to seven, eight to 10, or ≥ 11) and minutes per time (< 10, 10 to 19, 20 to 29, 30 to 59, or ≥ 60) that they performed moderate and/or vigorous activity. These questions and response options have been used and validated in other epidemiologic studies.37,38 Because response items included a range, we set values equal to the minimum value in the range, because individuals tend to over-report their physical activity level and intensity.39 We calculated the number of minutes of physical activity per week by multiplying the number of times per week by the number of minutes per time. We estimated total active minutes per week by combining measures of moderate and vigorous activity, irrespective of intensity. Physical activity was coded as sedentary if respondents hadn't performed any activity per week, somewhat active if they performed 1 to 149 minutes per week, and active if they performed ≥ 150 minutes per week according to current public health exercise guidelines.40

HRQOL.

Two summary scores from the Short Form-36 were used to measure HRQOL.41 These included the physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) constructed on the basis of the 1999 US population norms; these two scores had a mean value of 50 that represented the US population norms and a standard deviation of 10.41,42

Anxiety and depression.

The 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure anxiety (seven items) and depression (seven items).36,43 Questions were answered by using a four-point (ie, zero to three) response category, which had separate anxiety and depression scores that ranged from 0 to 21. Higher scores represent higher levels of depression and anxiety.

Health competence and perceived control.

We measured perceived health competence by using a four-item short form of the Perceived Health Competence (PHC) scale.44 To measure perceived control, we adapted four items from existing perceived control scales.45,46 The perceived control and health competence raw scores were linearly transformed to a 0 to 100 scale, which had higher scores to represent more of that attribute. Scores were ranked as high, medium, and low analyses.

Analytic Methods

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and health characteristics of the sample and the percentage of survivors of NHL who were meeting exercise guidelines, engaging in some exercise, or sedentary. To test our first hypothesis, we used multinomial logistic regressions to estimate odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the three-level physical activity variable (ie, sedentary; 1 to 149 minutes per week; or ≥ 150 minutes per week) on demographic, disease-related, and psychosocial variables. In the model, we compared individuals who reported sedentary behavior versus respondents who reported ≥ 150 minutes per week and those respondents who reported 1 to 149 minutes per week. Variables included in this model were associated with physical activity at the bivariate level by using χ2 tests for categoric variables and t tests for continuous variables. These variables included sex, BMI, comorbid limitations, health competence, anxiety, and depression. Other variables not found to be significant included ethnicity, marital status, education, health insurance, treatment, time since diagnosis, recurrence, disease grade, perceived control, social support, and optimism. To test our second hypothesis, general linear modeling was used to estimate adjusted mean scores and SEs for HRQOL for each level of physical activity. The following covariates were associated with at least one HRQOL indices in bivariate analysis and were therefore included to control for confounding: sex, age, marital status, health insurance coverage, and comorbid limitations.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Sociodemographic and disease-related characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 1. A comparison of study respondents and nonrespondents are listed in Table 2. Among the survivors whom we were able to contact, no significant differences were found between those who responded to the questionnaire and those who did not.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample

| Characteristic | No. | %* |

|---|---|---|

| Total No. of patients | 319 | |

| Age, years | ||

| Mean | 59.8 | |

| SD | 14.8 | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 156 | 48.9 |

| Male | 163 | 51.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 68 | 21.3 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 223 | 69.9 |

| Other | 28 | 8.8 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married† | 205 | 65.1 |

| Other | 110 | 34.9 |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 93 | 29.2 |

| Some college | 106 | 33.2 |

| College graduate or higher | 117 | 36.7 |

| Health insurance | ||

| Private | 208 | 65.2 |

| Public/none‡ | 95 | 29.8 |

| Treatment | ||

| Chemotherapy only | 156 | 48.9 |

| Chemotherapy + radiation | 108 | 33.9 |

| Transplantation§ | 34 | 10.7 |

| Comorbid limitations | ||

| Not limited | 153 | 48.0 |

| Limited some | 94 | 29.5 |

| Limited a lot | 48 | 15.0 |

| Time since diagnosis, years | ||

| 2-2.9 | 93 | 29.2 |

| 3-3.9 | 95 | 29.8 |

| 4-5.9 | 111 | 34.8 |

| NHL grade | ||

| Intermediate | 283 | 88.7 |

| High | 36 | 11.3 |

| Perceived control | ||

| Mean | 66.7 | |

| SD | 18.3 | |

| Health competence | ||

| Mean | 73.2 | |

| SD | 21.2 | |

| Mental component summary | ||

| Mean | 49.7 | |

| SD | 11.0 | |

| Physical component summary | ||

| Mean | 44.8 | |

| SD | 11.9 | |

| Anxiety | ||

| Mean | 4.7 | |

| SD | 3.7 | |

| Depression | ||

| Mean | 3.9 | |

| SD | 3.7 | |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Percentages do not always add to 100% because of missing data.

Includes individuals living with someone.

Fourteen respondents reported having no health insurance at the time of survey completion.

Includes bone marrow and/or stem-cell transplantation.

Table 2.

Comparison of Study Respondents and Nonrespondents According to Data Available in the SEER Registry

| Selected Characteristic | Respondents (%) | Refused (%) | Lost to Follow-Up (%) | P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | A v B | A v C | B v C | ||||

| Total No. of patients | 408 | 155 | 181 | ||||

| Age at diagnosis, years | |||||||

| 20-44 | 25.8 | 25.8 | 37.6 | < .01 | NS | < .001 | < .01 |

| 45-64 | 39.3 | 38.7 | 42.5 | ||||

| ≥ 65 | 34.9 | 35.5 | 19.9 | ||||

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 51.8 | 52.9 | 66.3 | < .01 | NS | .001 | .01 |

| Female | 48.2 | 47.1 | |||||

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 71.0 | 66.4 | 52.5 | < .001 | NS | < .0001 | .01 |

| Hispanic | 21.9 | 23.9 | 39.2 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.1 | 9.7 | 8.3 | ||||

| NHL grade | |||||||

| Intermediate | 89.7 | 92.3 | 85.1 | NS† | |||

| High | 10.3 | 7.7 | 14.9 | ||||

| Year of diagnosis | |||||||

| 1998 | 14.2 | 14.2 | 15.5 | NS† | |||

| 1999 | 30.2 | 20.6 | 30.4 | ||||

| 2000 | 31.9 | 43.9 | 33.2 | ||||

| 2001 | 23.6 | 21.3 | 21.0 | ||||

Abbreviations: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; A, respondents; B, refused; C, lost to follow-up; NS, nonsignificant.

P values are based on the bivariate χ2 statistic. P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant.

Follow-up subgroup comparisons (ie, A v second B, A v second C, B v second C) were not conducted if the overall effect was not significant.

Prevalence and Correlates of Exercise Behavior in Survivors of NHL

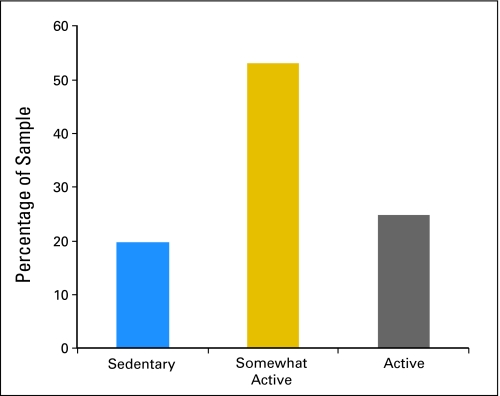

One quarter (25%) of respondents met public health guidelines of 150 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous exercise per week (active). More than half (53%) reported some activity (mean, 60 minutes; standard deviation [SD], 13.4) but less than 150 minutes per week, whereas 20% reported no physical activity (Fig 1). Results from multinomial logistic regressions (Table 3) showed that females were more than two times (odds ratio [OR], 2.26; 95% CI, 1.05 to 4.90) as likely to be in the sedentary group rather than the active group. Respondents with greater comorbid limitations were more than 3.5 times (OR, 3.71; 95% CI, 1.37 to 10.06) as likely to be in the sedentary group compared with the active group. Participants who had low health competence were more than six times (OR, 6.30; 95% CI, 1.92 to 20.68) as likely to be in the sedentary group rather than the active group. Analyses that compared the sedentary group to those who reported some exercise revealed that respondents who had low levels of health competence were more likely (OR, 4.71; 95% CI, 1.58 to 14.0) to be in the sedentary group compared with the group that reported some exercise.

Fig 1.

Proportion (%) of sample who are sedentary, somewhat active, and active. Somewhat active is defined as 1 to 149 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per week (mean, 60 minutes; standard deviation, 13.4 minutes); Active is defined as ≥ 150 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per week.

Table 3.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Models of the Relationship Between Physical Activity Level and Demographic, Health, and Psychosocial Factors Among Survivors of NHL

| Characteristic | Regression Analysis by Activity Level |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary v Active |

Sedentary v Somewhat Active |

|||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, years | ||||

| < 50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 50-64 | 0.54 | 0.25 to 1.37 | 1.15 | 0.51 to 2.62 |

| ≥ 65 | 0.79 | 0.51 to 23.7 | 1.05 | 0.51 to 2.17 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 2.26* | 1.05 to 4.90 | 1.30 | 0.67 to 2.53 |

| Male | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Married† | 0.88 | 0.40 to 1.95 | 0.77 | 0.39 to 1.50 |

| Other | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Health | ||||

| Body mass index‡ | ||||

| Normal | 0.40 | 0.14 to 1.13 | 0.97 | 0.43 to 2.20 |

| Overweight | 0.42 | 0.15 to 1.17 | 0.82 | 0.36 to 1.88 |

| Obese | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Comorbid limitation | ||||

| Not limited | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Limited some | 3.05 | 0.98 to 9.95 | 0.92 | 0.33 to 2.52 |

| Limited a lot | 3.71* | 1.37 to 10.06 | 1.52 | 0.62 to 3.68 |

| Psychosocial | ||||

| Health competence | ||||

| Low | 6.30* | 1.92 to 20.68 | 4.71* | 1.58 to 14.00 |

| Medium | 4.59* | 1.43 to 14.72 | 3.79* | 1.29 to 11.15 |

| High | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Depression | ||||

| Normal (< 8) | 0.22 | 0.05 to 0.88 | 0.51 | 0.20 to 1.32 |

| Above normal (≥ 8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Anxiety | ||||

| Normal (< 8) | 1.54 | 0.50 to 4.77 | 1.27 | 0.52 to 3.09 |

| Above normal (≥ 8) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

NOTE. All independent and dependent variables had less than 5% missing data. Analyses were based on available data and excluded the patient cases for whom data were missing.

Abbreviations: NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; OR, odds ratio.

Statistically significant.

Includes people who were living with someone.

Normal body mass index is 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; overweight is 25.0-29.9 kg/m2; and obese is ≥ 30 kg/m2.

HRQOL Differences in Survivors of NHL by Level of Exercise Behavior

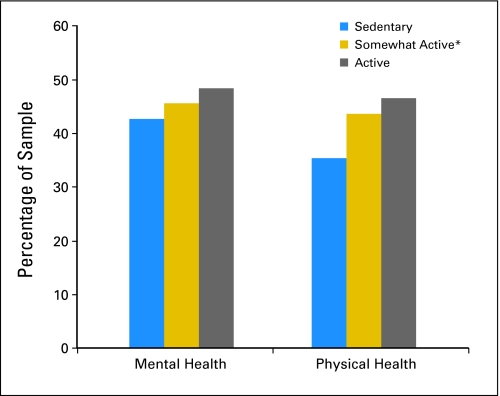

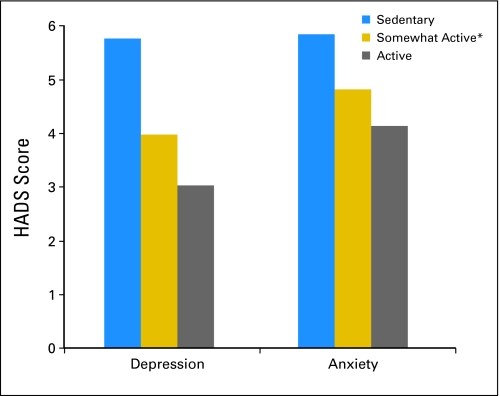

The unadjusted mean MCS and PCS scores for the sample were 49.7 and 44.8, respectively (SDs, 11.0 and 11.9, respectively). Twenty-five percent of the MCS scores were nearly one standard deviation below US population norms for MCS and were 1.5 standard deviations below the norm-based mean for the PCS. On average, scores on the depression and anxiety scales were low (depression scale: mean, 3.9; SD, 3.6; anxiety scale: mean, 4.7; SD, 3.7) and fell within normal levels. However, 16% of the sample reported greater than normal levels of depression (scores ≥ 8), and 19% reported above-normal levels of anxiety (scores ≥ 8) on the basis of clinical cutoff scores.43 Results from general linear models show that survivors of NHL who either met public health guidelines or engaged in some activity reported better mental and physical health compared with sedentary individuals (P < .001 for all; Fig 2). There was a significant dose-response pattern in which more exercise resulted in better mental and physical health. The adjusted mean scores of depression and anxiety by physical activity level showed similar dose-response patterns (P < .001 for all); more exercise resulted in lower depression and anxiety (Fig 3).

Fig 2.

General linear model for mental and physical health by exercise level and adjusted for sex, age, marital status, health insurance coverage, and comorbid limitations. (*) Creating two groups from the somewhat-active group on the basis of a mean split for that category (mean, 60 minutes) revealed no significant differences between the two groups on health-related quality of life scores. All independent and dependent variables had < 5% missing data; analyses were based on available data and excluded the patient cases for whom data were missing.

Fig. 3.

General linear model for depression and anxiety by exercise level and adjusted for sex, age, marital status, health insurance coverage, and comorbid limitations. (*) Creating two groups from the somewhat-active group on the basis of a mean split for that category (mean, 60 minutes) revealed no significant differences between the two groups on health-related quality of life scores. All independent and dependent variables had < 5% missing data; analyses were based on available data and excluded the patient cases for whom data were missing.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the prevalence and correlates of physical activity in adult survivors of aggressive NHL and the association between physical activity and HRQOL. The data indicate that the overwhelming majority of participants were not meeting public health guidelines for physical activity. Our findings provide partial support for our first hypothesis. Specifically, lower health competence and greater comorbid limitations were associated with lower levels of exercise activity, but age and perceived control were not significant. These findings support our second hypothesis, namely that survivors of NHL who met public health guidelines for physical activity reported better HRQOL than those who were sedentary. Notably, these findings, if supported by longitudinal data, might suggest a significant benefit in HRQOL among those who get at least some exercise, despite not meeting current guidelines.

Similar to previous research on exercise and survivors of NHL who had both indolent and aggressive disease25 and to a nationally representative study of cancer survivors and those without a history of cancer,29 almost three fourths of survivors in the sample did not meet public health recommendations for physical activity (compared with 36.6% of the general US population). However, more than 50% of the sample reported at least some exercise. Recognition of where individuals are in terms of their activity level is critical, because interventions to promote uptake of activity in sedentary individuals will be different than interventions to promote increasing exercise output in the somewhat-active or fully active groups. From a transtheoretical model perspective, individuals engaged in some activity or those who are fully active are already in the action stage, whereas sedentary survivors may be in the precontemplation or contemplation stage, which thus requires different intervention strategies. Although a tailored intervention approach is the most useful at an individual level, the design of a population-based approach for the majority of individuals already in the action stage would likely yield a larger impact from a public health perspective.

As NHL, similar to other cancers, becomes a disease that people live with as opposed to one that they die as a result of, oncologists will be challenged to provide evidence-based guidance for the long-term management of the patient's health. Exercise is emerging as an important area to consider within this realm. Despite the existence of several clinical trials designed to promote exercise in individuals with cancer,15,19,24 determination of the most efficacious, practical, and cost-effective approaches for longer-term survivors remains a challenge. Although more work is needed to address these issues, oncologists can make use of what we do know. Emerging observational and clinical trial data suggest that physical activity may reduce the risk of recurrence and may increase survival in certain groups of cancer survivors, and it may improve a cancer survivors physiologic and psychosocial health.16,18,28,47 This study adds to the growing body of literature that emphasizes the potential role of exercise in HRQOL of survivors of cancer.

An important aspect of these findings is the benefit in HRQOL among individuals who reported some exercise, despite not meeting current exercise guidelines. This finding is significant from both a research and practice perspective. Most of the research that examines the association between exercise and HRQOL dichotomizes exercise level into meeting public health guidelines versus not meeting public health guidelines.25 Future research should consider an examination of dose-response relationships on the basis of these findings. Additionally, there is an opportunity for health care providers to capitalize on this finding from a practice perspective. That is, even if survivors of cancer start off at lower levels of frequency and duration, this behavior can still benefit overall HRQOL. This type of counsel might not be as overwhelming and may be perceived by individuals as more obtainable compared with the broader public health exercise message. We know from the communication and psychology literature that individuals tend to avoid or ignore important information that is not consistent with their beliefs and perceived capabilities.48 Appropriate message framing might play a role in the motivation of sedentary individuals to engage in physical activity.49

Characteristics of individuals more likely to be sedentary offer investigators and health care professionals knowledge about targets for interventions. Females, those with low health competence, and individuals who have more comorbid limitations are at increased risk for inactivity. The extent to which individuals who have competing chronic health conditions can safely initiate physical activity is an important issue.50 Physicians are in the best position to educate their patients about the actual risks of physical activity in light of patient, disease, or treatment characteristics and about how to self-monitor their progress and intensity. Importantly, physical activity doesn't necessarily have to be intense for individuals to derive benefit. Many studies have found that walking at a slow pace can influence physiologic and HRQOL outcomes16,18,28 and, in fact, can be comparable to the effects of some pharmaceutical agents.51 The consequences of physical inactivity, which include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, second cancers, poor HRQOL, and reduced mortality, may far exceed the risks of a carefully planned exercise program for someone who has a coexisting health condition.

However, as these data are cross-sectional, we can make no inferences about causality. The nature of our data likely reflects the effect of exercise on HRQOL as well as the effect of HRQOL on exercise behavior. However, several well-designed studies have found a causal relationship between exercise and HRQOL.15,52 Another limitation of these data is that physical activity was measured via brief self-report, which tends to provide overestimations of actual activity level compared with objective techniques, such as accelerometers. However, we used a conservative approach to analyze the physical activity data, as outlined in the methods section. The physical activity questions used did not allow estimates of metabolic equivalents, as do other self-report measures of physical activity.53 The response rate, although consistent to similar population-based survivorship studies, can induce nonresponse bias in our estimates. For example, nonresponders might have worse health and, perhaps, might not be exercising at the same levels of responders. Lastly, the extent to which these findings would generalize to other cancer survivor populations is unknown.

Nevertheless, this study is the first to describe exercise behavior in adult survivors of aggressive NHL and to examine the dose-response relationship between this behavior and HRQOL. These findings indicate a significant benefit in HRQOL among those who get at least some exercise, despite not meeting current guidelines. Given the absence of studies that examine improvements in HRQOL as a function of exercise dose-response, coupled with existing evidence that suggests meeting public health guidelines can improve HRQOL for cancer survivors, it is likely that those clinicians who counsel their patients regarding exercise and HRQOL are providing guidance on the latter. However, if these dose-response findings are replicated in randomized control trials, consideration should be given to how clinicians frame exercise-promoting messages to cancer survivors, especially to those who are sedentary.

Footnotes

Supported in part by the California Department of Health Services as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; by National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program Contract No. N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California and Contract No. N02-PC-15105 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Program of Cancer Registries Agreement No. U55/CCR921930-02 awarded to the Public Health Institute.

The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s). Endorsement by the California Department of Health Services, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their contractors and subcontractors is not intended, nor should it be inferred.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Keith M. Bellizzi, Julia H. Rowland, Neeraj K. Arora, Noreen M. Aziz

Provision of study materials or patients: Neeraj K. Arora, Ann S. Hamilton

Collection and assembly of data: Ann S. Hamilton

Data analysis and interpretation: Keith M. Bellizzi, Neeraj K. Arora, Melissa Farmer Miller, Noreen M. Aziz

Manuscript writing: Keith M. Bellizzi, Julia H. Rowland, Neeraj K. Arora, Ann S. Hamilton, Melissa Farmer Miller, Noreen M. Aziz

Final approval of manuscript: Keith M. Bellizzi, Julia H. Rowland, Neeraj K. Arora, Ann S. Hamilton, Melissa Farmer Miller, Noreen M. Aziz

References

- 1.Fisher SG, Fisher RI. The epidemiology of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Oncogene. 2004;23:6524–6534. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sehn L, Connors J. Treatment of aggressive non-hodgkin's lymphoma: A North American perspective. Oncology. 2005;19(suppl):27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernsler J, Fanuele JS. Lymphomas: Long-term sequelae and survivorship issues. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1998;14:321–328. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(98)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jerkeman M, Kaasa S, Hjermstad M, et al. Health-related quality of life and its potential prognostic implications in patients with aggressive lymphoma: A Nordic Lymphoma Group Trial. Med Oncol. 2001;18:85–94. doi: 10.1385/MO:18:1:85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sitzia J, North C, Stanley J, et al. Side effects of CHOP in the treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Nurs. 1997;20:430–439. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199712000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellizzi KM, Miller MF, Arora NK, et al. Positive and Negative Life Changes Experienced by Survivors of non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34:188–199. doi: 10.1007/BF02872673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganz PA. Late effects of cancer and its treatment. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2001 Nov;17(4):241–248. doi: 10.1053/sonu.2001.27914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown BW, Brauner C, Minnotte MC. Noncancer deaths in white adult cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993 Jun 16;85(12):979–987. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.12.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bines J, Gradishar WJ. Primary care issues for the breast cancer survivor. Compr Ther. 1997 Sep;23(9):605–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shapiro CL, Recht A. Late effects of adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1994;16:101–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Ries LAG, et al. Multiple Cancer Prevalence: A growing challenge in long-term survivorship. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:566–571. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aziz NM. Late effects of cancer treatments. In: Ganz PA, editor. Cancer Survivorship: Today and Tomorrow. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2007. pp. 54–76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aziz NM. Cancer survivorship research: State of knowledge, challenges and opportunities. Acta Oncol. 2007;46:417–432. doi: 10.1080/02841860701367878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: Cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1600–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479–2486. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard CM, Stein KD, Baker F, et al. Association between current lifestyle behaviors and health-related quality of life in breast, colorectal and prostate cancer survivors. Psychol Health. 2004;19:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyerhardt JA, Giovanucci EL, Holmes MD, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–3534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinto BM, Frierson GM, Rabin C, et al. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3577–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Courneya KS, Keats MR, Turner AR. Physical exercise and quality of life in cancer patients following high dose chemotherapy and autologous bone marrow transplantation. Psychooncology. 2000a;9:127–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<127::aid-pon438>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dimeo FC, Fetscher S, Lange W, et al. Effects of aerobic exercise on the physical performance and incidence of treatment-related complications after high-dose chemotherapy. Blood. 1997;90:3390–3394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, et al. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Can Med Assoc J. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmitz KH, Holtzman J, Courneya KS, et al. Controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:1588–1595. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, et al. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors. Nurs Res. 2007;56:18–27. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vallance JKH, Courneya KS, Jones LW, et al. Differences in quality of life between non-Hodgkin's lymphoma survivors meeting and not meeting public health exercise guidelines. Psychooncology. 2005;14:979–991. doi: 10.1002/pon.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevinson C, Faught W, Steed H, et al. Associations between physical activity and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Robbins KT, et al. Physical activity and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:1012–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Courneya KS. Exercise in cancer survivors: An overview of research. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1846–1852. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000093622.41587.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bellizzi KM, Rowland JH, Jeffery DD, et al. Health behaviors of cancer survivors: Examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong S, Bardwell WA, Natarajan L, et al. Correlates of physical activity level in breast cancer survivors participating in the Women's Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;101:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9284-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Reid RD, et al. Three independent factors predicted adherence in a randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training among prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terry DJ, O'Leary JE. The theory of planned behaviour: The effects of perceived behavioural control and self-efficacy. Br J Soc Psychol. 1995;34:199–220. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.1995.tb01058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheung C, Wyman J, Gross C, et al. Exercise behavior in older adults: A test of the transtheoretical model. Journal Aging Phys Act. 2007;15:103–118. doi: 10.1123/japa.15.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall SJ, Biddle SJH. The transtheoretical model of behavioral change: A meta-analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23:229–246. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arora NK, Hamilton AS, Potosky AL, et al. Population-based survivorship research using cancer registries: A study of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:49–63. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reference deleted.

- 37.Hawkins SA, Cockburn MG, Hamilton AS, et al. An Estimate of Physical Activity Prevalence in a Large Population-Based Cohort. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:253–260. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000113485.06374.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aaron DJ, Kriska AM, Dearwater SR, et al. Reproducibility and validity of an epidemiologic questionnaire to assess past year physical activity in adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:191–201. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sarkin JA, Nichols JF, Sallis JF, et al. Self-report measures and scoring protocols affect prevalence estimates of meeting physical activity guidelines. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:149–156. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200001000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995 Feb 1;273(5):402–407. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ware J, Kosinski M, Dewey J. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc; 2000. How to score version 2 of the SF-36 Health Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ware JJ, Kosinski M, Gandek B. 2000. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetrics Inc; SF-36 Health survey: Manual and interpretation guide. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith M, Wallston K, Smith C. The development and validation of the Perceived Health Competence Scale. Health Educ Res. 1995;10:51–64. doi: 10.1093/her/10.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Manne S, Glassman M. Perceived control, coping efficacy, and avoidance coping as mediators between spouses' unsupportive behaviors and cancer patients' psychological distress. Health Psychol. 2000;19:155–164. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Affleck G, Tennen H, Pfeiffer C, et al. Appraisals of control and predictability in adapting to a chronic illness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:273–279. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holtzman J, Schmitz K, Babes G, et al. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. Jun, Effectiveness of Behavioral Interventions to Modify Physical Activity Behaviors in General Populations and Cancer Patients and Survivors. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 102 (Prepared by the Minnesota Evidence-based Practice Center, under Contract No. 290-02-0009.) AHRQ Publication No. 04-E027-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Case DO, Andrews JE, Johnson JD, et al. Avoiding versus seeking: The relationship of information seeking avoidance, blunting, coping, dissonance, and related concepts. J Med Libr Assoc. 2005;93:353–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones LW, Sinclair RC, Courneya KS. The effects of source credibility and message framing on exercise intentions, behaviors, and attitudes: An integration of the Elaboration Likelihood Model and Prospect Theory. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2003;33:179–196. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Courneya KS, Vallance JKH, McNeely ML, et al. Exercise issues in older cancer survivors. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2004;51:249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haskell WL. Health consequences of physical activity: Understanding and challenges regarding dose-response. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:649–660. doi: 10.1249/00005768-199406000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segar ML, Katch VL, Roth RS, et al. The effect of aerobic exercise on self-esteem and depressive and anxiety symptoms among breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25:107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A simple method to assess exercise behavior in the community. Can J Appl Sports Sci. 1985;10:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]