Abstract

The pars tuberalis is a distinct subdivision of the pituitary gland but its function remains poorly understood. Suprasellar tumors in this pars tuberalis region are frequently accompanied by hyperprolactinemia. As these tumors do not immunoreact for any of the established pituitary hormones, they are classified as non-secretory. It has been postulated that these suprasellar tumors induce hyperprolactinemia by compressing the pituitary stalk, resulting in impaired dopamine delivery to the pituitary and, consequently, disinhibition of the lactotropes. An alternative hypothesis proposed is that suprasellar tumors secrete a specific pars tuberalis factor that stimulates prolactin secretion. Hypothesized candidates are the preprotachykinin A derived tachykinins, substance P and/or neurokinin A.

Keywords: substance P, neurokinin, tachykinin, prolactin

Background

Prolactin is an adenohypophyseal hormone that has been implicated in an array of physiological functions, including a critical role in reproduction. A specific prolactin-releasing factor has not been identified. Hyperprolactinemia is commonly associated with reproductive dysfunction in both women and men: it is estimated that 9% of women with amenorrhea, 25% with galactorrhea and up to 70% with both amenorrhea and galactorrhea have hyperprolactinemia [1]. The prevalence is about 5% of men that present with impotence or infertility [1]. As a consequence of the tumor-induced gonadal dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia is also associated with osteoporosis [2]. Pituitary tumors are a major cause of hyperprolactinemia [3]. In most cases of tumor-dependent hyperprolactinemia, prolactin is secreted by the tumor. However, tumors in the region of the adenohypophyseal stalk (suprasellar tumors) cause hyperprolactinemia but are not classic prolactinomas and do not immunoreact for the classic pituitary hormones. Thus, these tumors have been classified as non-secretory. The current hypothesis as to how these tumors result in hyperprolactinemia, without secreting prolactin, has been term the “stalk effect” or “pituitary stalk compression syndrome”. According to this hypothesis, these tumors squeeze the pituitary stalk and physically compress the infundibular stalk dopaminergic neurons or disrupt hypophyseal portal blood flow, which delivers dopamine to the lactotropes. Dopamine is an established prolactin-inhibiting factor [4]. Thus, this tumor-mediated physical compaction results in reduced dopamine release and a commensurate increase in prolactin output.

Presentation of an alternative hypothesis

The pars tuberalis is a distinct, but largely unstudied, subdivision of the adenohypophysis that corresponds to the stalk region. The pars tuberalis surrounds the neural tissue projecting to the posterior pituitary and extends ventrally down the anterior face of the adenohypophysis as the zona tuberalis [5]. It is now known that the pars tuberalis secretes a specific factor that drives seasonal prolactin rhythms in mammals [6]. Thus, an alternative hypothesis proposed is that suprasellar tumors release a factor, which stimulates prolactin release. The identity of this specific pars tuberalis factor, called “tuberalin” in the interim, is not known. From preliminary evidence we hypothesize that this factor may be substance P and/or neurokinin A. Both these tachykinins have been shown to stimulate prolactin release in mammals [7].

Testing the hypothesis

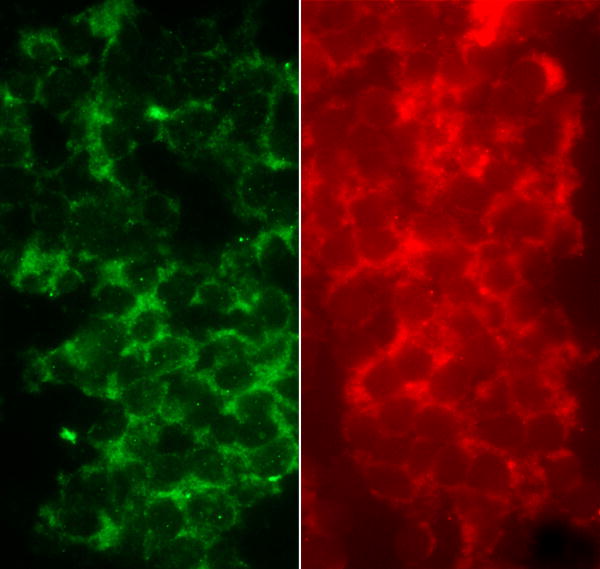

If physical compression of the infundibular stalk is responsible for elevated prolactin then it is reasonable to postulate that the extent of hyperprolactinemia may correspond with the size of the adenoma. Kruse et al [3] could find no correlation between tumor size and prolactin levels and also no difference in intrasellar pressure between patients with or without hyperprolactinemia. There are no substantive studies simultaneously investigating tachykinins and prolactin in pituitary tumors. However, it is noteworthy that one patient (G.H.) with a non-secreting tumor but increased prolactin levels, was also found to have elevated levels of substance P in this tumor, relative to normal controls [8]. Future prospective studies should investigate the relationship between tachykinins, either in the circulation or the tumor, and prolactin concentrations. In this context, and in preliminary support of our hypothesis that this specific factor may be a tachykinin, a biopsy from a single “stalk” tumor (64 year-old male) revealed clear evidence of an abundance of tachykinins. Cells were packed together in the tumor and cytoplasmic immunolabeling for both substance P and NKA was clearly evident (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Photomicrographs of substance P (green; antibody # T-5019; Peninsula Laboratories, San Carlos, CA) and neurokinin A (red; antibody # PA-623-9; Austral Biologicals, San Ramon, CA) immunolabeling in a suprasellar tumor obtained from a 64 year-old male. The nucleus was devoid of labeling for both tachykinins.

Implications of the hypothesis

The “stalk effect” hypothesis arose primarily due to an inability to demonstrate a known pituitary hormone in the pars tuberalis and these tumors have been classified as chromophobic or non-secreting. Identification of a pars tuberalis factor(s) that drives prolactin release may lead to novel therapeutic interventions in hyperprolactinemia. Here we hypothesize that one candidate may be a tachykinin.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NSF grant #0745084 and P20RR015640 from the National Center for research Resources (NCRR). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF, NCRR or NIH. The Brain Tumour Tissue Bank (London, Ontario, Canada) is thanked for the suprasellar tumor biopsy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Josimovich JB, Lavenhar MA, Devanesan MM, Sesta HJ, Wilchins SA, Smith AC. Heterogeneous distribution of serum prolactin values in apparently healthy young women, and the effects of oral contraceptive medication. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:785–791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biller BM, Baum HB, Rosenthal DI, Saxe VC, Charpie PM, Klibanski A. Progressive trabecular osteopenia in women with hyperprolactinemic amenorrhea. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:692–697. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.3.1517356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kruse A, Astrup J, Gyldensted C, Cold GE. Hyperprolactinaemia in patients with pituitary adenomas. The pituitary stalk compression syndrome. Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:453–457. doi: 10.1080/02688699550041089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Jonathan N, Hnasko R. Dopamine as a prolactin (PRL) inhibitor. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:724–763. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.6.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skinner DC, Robinson JE. Melatonin-binding sites in the gonadotroph-enriched zona tuberalis of ewes. J Reprod Fertil. 1995;104:243–250. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1040243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgan PJ. The pars tuberalis: the missing link in the photoperiodic regulation of prolactin secretion? J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:287–295. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debeljuk L, Lasaga M. Tachykinins and the control of prolactin secretion. Peptides. 2006;27:3007–3019. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desiderio DM, Kusmierz JJ, Zhu X, Dass C, Hilton D, Robertson JT. Mass spectrometric analysis of opioid and tachykinin neuropeptides in non-secreting and ACTH-secreting human pituitary adenomas. Biol Mass Spec. 1993;22:89–97. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200220112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]