Abstract

Dendritic cells (DCs) are a heterogeneous fraction of rare hematopoietic cells that coevolved with the formation of the adaptive immune system. DCs efficiently process and present antigen, move from sites of antigen uptake to sites of cellular interactions, and are critical in the initiation of immune responses as well as in the maintenance of self-tolerance. DCs are distributed throughout the body and are enriched in lymphoid organs and environmental contact sites. Steady-state DC half-lives account for days to up to a few weeks, and they need to be replaced via proliferating hematopoietic progenitors, monocytes, or tissue resident cells. In this review, we integrate recent knowledge on DC progenitors, cytokines, and transcription factor usage to an emerging concept of in vivo DC homeostasis in steady-state and inflammatory conditions. We furthermore highlight how knowledge of these maintenance mechanisms might impact on understanding of DC malignancies as well as posttransplant immune reactions and their respective therapies.

Introduction

Dendritic cells (DCs) are hematopoietic cells that belong to the antigen-presenting cell (APC) family, which also includes B cells and macrophages. Although Langerhans cells (LCs) in the skin were described in 1868, the role of DCs as APCs was not appreciated until 1973, when Steinman and Cohn first identified DCs in mouse spleen as potent stimulators of the primary immune response.1 Shortly thereafter, several groups reported the presence of DCs in nonlymphoid tissues of rodents and humans and demonstrated early evidence that these cells contribute to heart and kidney transplantation rejection.2 However, the low number of DCs in vivo, the paucity of markers that distinguish them from monocytes/macrophages, and the problems in purifying these cells made for slow progress. In the 1990s, the development of methods to isolate and generate DCs from blood and bone marrow (BM) led to explosive growth of the DC field.3–5 Studies in the last decade have established the critical role of DCs in the maintenance of immunologic integrity and their importance in the development and potential treatment of human disease, leading in 2007 to the attribution of the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Research to Dr Ralph Steinman (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) in recognition of his discovery of DCs.

Heterogeneity, localization, and life cycle of DC populations

DCs are a heterogeneous population of cells that can be divided into 2 major populations: (1) nonlymphoid tissue migratory and lymphoid tissue–resident DCs and (2) plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs, also called natural interferon-producing cells). The term “classic” or “conventional” DCs (cDCs) has recently been used to oppose lymphoid organ–resident DCs to pDCs. Nonlymphoid organ DCs, on the other hand, are mainly called tissue DCs. Although the term cDC is helpful in some respect, it also might be confusing as nonlymphoid tissue DCs are also different from pDCs, and primary nonlymphoid tissue DCs can be found in lymph nodes (LNs) on migration but are not cDCs. Thus, throughout this review, the term DCs will refer to all non-pDCs whether they are present in lymphoid or nonlymphoid tissues, and location will be appropriately specified.

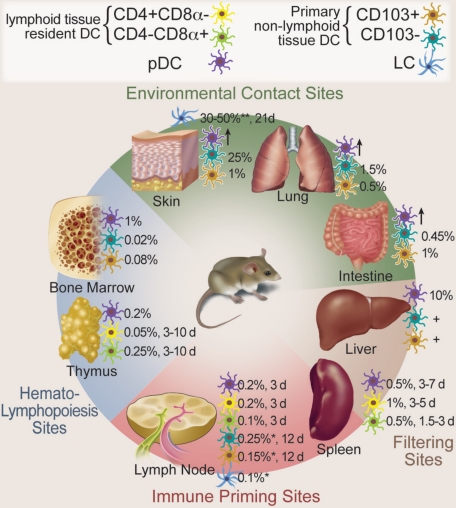

Migratory and resident DCs have 2 main functions: the maintenance of self-tolerance and the induction of specific immune responses against invading pathogens,1,6 whereas the main function of pDCs is to secrete paramount amounts of interferon-α in response to viral infections and to prime T cells against viral antigens.7 Figure 1 and Table S1 (available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article) show different DC populations, their frequencies, locations, and turnover in various lympoid and nonlymphoid tissues.

Figure 1.

Mouse DC populations, location, and turnover in steady state. DCs are distributed throughout the body. The major DC subpopulations at hematopoietic sites, environmental contact sites, filtering sites, and immune priming sites are depicted. Frequencies are given as percentage of total nucleated hematopoietic cells. Time to approximately 50% renewal in steady state is given in days (d). *Skin-draining LN; **epidermis; +present, but exact numbers not known; ↑, present in inflammation. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

DCs in nonlymphoid tissues

Nonlymphoid tissue DCs can be distinguished between those present in sterile tissues, such as the pancreas and the heart, DCs present in filtering sites, such as the liver and the kidney, and DCs present at environmental interfaces as lung, gut, and skin. Among interface DCs, epidermal DCs, also called LCs, are the most studied. LCs constitutively express major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II and high levels of the lectin langerin, forming the intracytoplasmic birbeck granule. Human LCs express CD1a, a MHC class I homolog that is often used to identify human LCs. Recent data established that langerin expression is not specific for LCs. In mice, langerin is expressed at low levels, on CD8α+ DCs in lymphoid organs, and on a population of DCs present in the lung and the dermis.8,9 These langerin+ interstitial DCs express low levels of the integrin CD11b and coexpress αEβ7 (CD103), a ligand of the cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin expressed by most epithelial cells. CD103+ DCs negative for langerin have also been identified in the gut. In addition to CD103+ DCs, tissues also contain another major DC population that is characterized as MHC class II+CD11c+CD11bhiCD103−langerin−. The exact contribution of each of these populations to tissue immunity is currently being examined.

Tissue DCs sample antigens and migrate constantly through afferent lymphatics to the T-cell areas of LN, a process that increases manyfold in response to inflammatory signals.10 Although DC efflux from tissues to the tissue-draining LN is difficult to accurately quantify,11 it is clear that tissue-DC homeostasis requires constant replacement with new cells. BM chimera studies in mice established that kidney and heart DCs are replaced in 2 to 4 weeks after lethal irradiation and BM transplantation, whereas DC repopulation in the vagina,12 airway epithelia,13 and the gut is more rapid and occurs in 7 to 13 days (M. Bogunovic and M.M., unpublished data, January 2009). In the thoracic duct from mesenteric lymphadenectomized rats, the first DCs were detected at 24 hours and peaked at 3 days after labeling, suggesting that the turnover time of gut DCs is very rapid.14

In contrast, epidermal LC life span differs fundamentally from that of other DCs.15 Approximately 2% to 3% LCs are constantly cycling, and LCs resist lethal dose of irradiation and remain of host origin in BM chimeric animals more than 18 months after transplantation.16 It is therefore possible that both local hematopoietic precursor cells and differentiated LCs through self-renewal could contribute to LC steady-state homeostasis, depending on physiologic needs, as has been shown for skin stem cells.

Although not representative for steady-state turnover, it is interesting that, in patients who received allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (allo-HCT), recipient LCs can be identified unequivocally in the epidermis more than 1 year after allo-HCT.17 Donor LCs have also been shown to persist for years in a recipient of a human limb graft,18 suggesting that human LCs as their murine counterparts repopulate locally in steady state.

DCs in lymphoid tissues

Lymphoid tissue–resident DCs are the most studied DC populations in mice, but little information is available on their human counterparts.

The spleen is populated via blood. In mice, splenic DCs constitutively express MHC class II and the integrin CD11c. They are further classified into 2 major subsets that include CD4+CD8α−CD11b+ DCs that localize mostly in the marginal zone and CD8α+CD4−CD11b− DCs localized mostly in the T-cell zone.19 CD4−CD8α−CD11b+ DCs have also been identified and are called double-negative DCs. CD8α+ DCs are specialized in MHC class I presentation, whereas CD4+ DC subset is specialized in MHC class II presentation. CD8α+ DCs have also been shown to cross-present cell-associated antigens, whereas CD4+ DCs are unable to do so.20 CD8α is not expressed on human DCs, but recent data from 2 separate groups identified in human blood a DC subset that resembles the mouse CD8α+ DCs (discussed in “Blood DCs”). In vivo bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) labeling studies in mice revealed that 5% lymphoid organ DCs or their immediate progenitors are actively cycling at any given time.21 Results from parabiotic mice that share the same blood circulation for prolonged periods of time showed that, 3 weeks after parabiosis, 30% spleen DCs derive from parabiont partners. On separation, partner-derived DCs are entirely replaced by endogenous-derived cells in 10 to 14 days. These data prove that, although DC progenitors proliferate locally with small burst size, they do not self-renew and are continuously replaced by blood-borne precursors.22–24

LN DCs are more heterogeneous as they include blood-derived lymphoid tissue–resident CD8α+, CD4+, and double-negative spleen equivalent DCs, and migratory DCs entering via the afferent lymphatics that vary according to the LN draining site.10 For example, migratory epidermal LCs and dermal DCs are present in skin-draining LNs but are absent from mesenteric LNs. Blood-derived DCs or their local progenitors have similar turnover rates as spleen DCs, whereas the life span of tissue-derived DC varies as discussed in “DCs in nonlymphoid tissues.”

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues include lymphoid tissue in the nasopharynx, Peyer patches and isolated lymphoid follicles in the small intestine, and isolated follicles and the appendix in the large intestines. These tissues are mostly populated by blood-derived cells, and the phenotype and probably also turnover resemble those of spleen DCs.25

Thymic DCs localize mostly in the medulla. The majority of mouse thymic DCs are CD8α+ and are thought to be generated locally from early thymocyte progenitors. A minority of DCs is CD8α− and is best characterized by the expression of signal regulatory protein-α and is thought to derive independently of thymic progenitors.26 Thymic DCs play a major role in negative selection of T cells.27 A recent study suggests that circulating DCs can enter the thymus and are involved in both establishment of central tolerance and the induction of antigen specific T-regulatory cells28 (Li Wu, XIIth International DC Meeting, Kobe, Japan, 2008). Thymic CD8α+ and CD8α− DCs incorporate BrdU in a biphasic pattern with a rapid uptake in the first 3 days followed by a lag period giving rise to 80% labeled DCs in 10 days.29 Data from the parabiotic model have also identified 2 separate homeostatic patterns among thymic DCs.30 One DC population fails to equilibrate among parabionts, reaching similarly to thymocytes, less than 10% chimerism after 5 weeks of parabiosis, suggesting that this DC population derives from an intrathymic progenitor.26 In contrast, a second thymic DC population rapidly exchanged among parabionts, reaching 50% chimerism in 5 weeks probably representing the blood-borne thymic DCs discussed in this section.

Plasmacytoid DCs in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues

Similarly to DCs, pDCs constitutively express MHC class II molecules and lack most lineage markers. Murine pDCs lack CD11b and express low levels of the integrin CD11c and the lineage markers CD45RA/B220+ and ly6C /GR-1+, and express PDCA1 and siglec-H, a member of the sialic acid binding Ig-like lectin (Siglec) family and recently identified as a specific surface marker for mouse pDCs.7,19,31 Human pDCs express very low to no level of CD11c, they express CD4 and CD45RA antigens, the c-type lectin receptor BDCA2, and the molecule BDCA4, a neuronal receptor often used to isolate pDCs, and high levels of the interleukin-3 (IL-3) receptor (CD123). pDCs circulate in blood and are found in steady-state BM, spleen, thymus, LN, and the liver. Human and mice pDCs enter the LN through the high endothelial venule and accumulate in the paracortical T cell–rich areas.32 In contrast to DCs, pDCs do not efficiently migrate to peripheral tissue in the steady state with the exception of the liver. pDC proliferation rate in lymphoid organs is very low, and less than 0.3% pDCs are in cell cycle. On continuous BrdU labeling over 14 days in vivo, 90% of pDCs were positive,33 and on separation of parabiotic mice, donor-derived pDCs are replaced in 3 days.22 Thus, the lifespan of differentiated pDCs in the spleen and LN is very short and continuous replacement via blood is essential.

Blood DCs

Blood DCs have been mostly studied in humans where both DCs and pDCs can be found. In patients who received allo-HCT, blood DCs and pDCs are replaced by donor-derived cells in less than a week after transplantation.17 Recent data from 2 separate groups identified a potential counterpart of the mouse lymphoid organ CD8α+ DCs in human blood,34,35 providing a unique opportunity to examine whether human DCs share the functional specialization of the CD8α+ DC system. Mouse blood DCs are less well characterized. The majority of circulating MHC class II+CD11c+ are pDCs, but low numbers of MHC class II+CD11c+ DCs and MHC class II−CD11c+ DC progenitors shown to give rise to CD8α+ and CD8α− DCs in lymphoid organs can also be detected.36

Cytokines in DC development

The discovery that granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a key cytokine for the differentiation of mouse and human hematopoietic progenitors3,4 and human monocytes5 into DCs in vitro marked the acceleration of DC research. It then came as a surprise that DCs develop normally in mice that lack GM-CSF or its receptor.37 Similarly, mice injected with GM-CSF or transgenic mice overexpressing GM-CSF have only moderate changes in DC numbers37,38 (Table S2 summarizes cytokine effects on in vivo DC homeostasis). It is only when mice are injected with GM-CSF–expressing adenovirus or with GM-CSF with engineered long half-life that massive expansion of CD8α− DCs secreting “inflammatory” cytokines tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), IL-6, and inducible nitric oxide was observed. GM-CSF is produced by tissue stromal cells, and by activated T cells and NK cells. Although GM-CSF is not detectable in steady-state serum, it increases during inflammation.39 Thus, although GM-CSF is dispensable for steady-state DC development, it can play a role in DC differentiation in inflammatory situations. Consistent with these data, injection of GM-CSF is used in clinical studies to attract or generate DCs at disease sites.40 In vivo GM-CSF–driven DC differentiation may resemble the in vitro GM-CSF cultures involving GM-CSFR-expressing monocytes.

In contrast, genetic deletion of Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (Flt3L) or treatment with Flt3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors in mice leads to 10-fold reduction of pDCs and DCs in lymphoid organs,41,42 whereas LCs are largely unaffected (M.M. and M.G.M., unpublished data, January 2009). Injection or conditional expression of Flt3L leads to massive expansion of both pDCs and DCs in all lymphoid and nonlymphoid organs, including the large and small intestine and the liver, with up to 30% of mouse spleen cells expressing CD11c.38,43,44 Consistently, Flt3L as a single cytokine can drive differentiation of mouse BM progenitors into all DC subtypes in vitro, including pDC differentiation, which cannot be generated in GM-CSF–supplemented cultures.45,46 Similarly, Flt3L supports in vitro development of pDCs and DCs from human hematopoietic progenitors,47–49 and Flt3L injection in humans leads to massive expansion of blood pDCs and DCs.50 Thus, in contrast to GM-CSF, Flt3L is both sufficient and essential for the development of blood and lymphoid organ DCs and pDCs. Flt3L exists in both a soluble and membrane-bound form and is expressed by multiple tissue stroma cells and by activated T cells.51 Bioactive levels of Flt3L are measurable in serum in steady state and increase on inflammation and hematopoietic stress, such as irradiation-induced cytopenia. In addition, mice that lack Flt3 receptor, mice treated with Flt3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and mice with targeted DC depletion show 10- to 20-fold increased levels of serum Flt3L42,52 (M. Schmid and M.G.M., unpublished data, January 2009). Together, these data show that Flt3L plays a key and nonredundant role in DC development in BM and peripheral lymphoid organs, and Flt3L levels are adjusted via a regulatory loop tailored to ensure sufficient DC production in steady state and on demand.

CSF-1 (M-CSF) is a key cytokine for macrophage development. Mice that lack CSF-1 or its receptor (CSF-1R) lack several macrophage populations and develop osteopetrosis because of the absence of osteoclasts.53,54 Although initially thought to be dispensable for DC development,55 data from our laboratory established that CSF-1R is required for LC development.56 CSF-1 reporter mice revealed that Csf-1r mRNA is expressed by most lymphoid organ DCs, but the exact correlation of Csf-1r mRNA levels and the protein expression in these mice remains unclear.57 CSF-1 can also enhance DC numbers in cultures, and injection of CSF-1 increases both lymphoid organ pDCs and DCs in mice.58,59 CSF-1 is expressed by endothelia, stroma cells, osteoblasts, and macrophages, and, as Flt3L, is detectable in steady-state serum and increases on inflammation39 (M. Schmid and M.G.M., unpublished data, January 2009). Consistently, we found that monocytes repopulate LCs in inflamed skin in a CSF-1R–dependent manner.56 CSF-1R might also be involved in other nonlymphoid tissue DC development, but its exact role in DC differentiation remains to be examined.

In addition to CSF-1, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is a nonredundant cytokine for LC development in vivo in mice,60 and similarly supports LC development in vitro from human hematopoietic progenitors.61 In the skin, keratinocytes are a large source of TGF-β1, and it has been assumed that exogenous TGF-β1 was critical for LC development. Recent data, however, have challenged this view as mice in which absence of TGF-β1 secretion is restricted to LCs cannot develop epidermal LCs,62 suggesting that LCs might control their development in an autocrine fashion.

Whereas Flt3L, GM-CSF, CSF-1, and TGF-β1 are major known cytokines for in vivo DC development, other cytokines, such as IL-4, TNF-α, LTβ, and G-CSF, probably have more subtle effects within steady-state and inflammatory DC homeostasis. The complex interaction of cytokines required for optimal DC differentiation should be addressed by investigating combined cytokine effects in vivo but also by in vivo imaging via labeling of cytokine-producing cells and cytokine receptor–expressing DC progenitors.

Transcription factors in DC development

Environmental stimuli, as cytokines, need to be translated on the subcellular level. The use of knockout mouse models revealed key roles of several transcription factors in DC development, some of which are required for global DC development, whereas others are restricted to specific DC subsets. We here discuss those that are currently understood in the context of signaling networks and provide a more complete list in Table 1.

Table 1.

Transcription factor effects on in vivo DC homeostasis

| Transcription factor | Bone marrow DC progenitor | Spleen pDC | Spleen DC CD8a−/+ | Langerhans cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stat3−/− | NA | NA | 0.1/0.1 | NA | 63 |

| Gfi-1−/− | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.5/0.5 | 2 | 65 |

| Stat5−/− | NA | 0.4 | 0.4/0.3 | NA | 66 |

| Ikaros−/− | NA | NA | Absent/0.15 | NA | 122 |

| Ikaros DN−/− | NA | NA | Absent | NA | 122 |

| Ikaros IkL/L | NA | < 0.1 | 0.8/1.1 | NA | 123 |

| Xbp-1−/− | NA | 0.3 | 0.6 | NA | 124 |

| RelB−/− | NA | NA | Absent/1 | 1 | 68 |

| Pu.1−/− | NA | NA | < 0.1/1 | NA | 70,71 |

| Irf-2−/− | NA | NA | 0.25/1 | 0.7 | 73 |

| Irf-4−/− | NA | 0.5-1 | 0.3/1 | NA | 74,75 |

| Irf-8−/− | 1 | 0.1 | 1/0.1 | 0.5 | 76,77 |

| Id2−/− | NA | 1.5 | 1/< 01 | Absent | 78 |

| Runx3−/− | NA | NA | 0.8/2 | Absent | 81 |

| E2-2−/− | NA | < 0.1 | 1/1 | NA | 79 |

| Batf3−/− | NA | 1 | 1/< 0.1 | NA | 80 |

Values are given as approximate fold of wild type.

NA indicates not available.

Transcription factors affecting all DC-type development

Hematopoietic deletion of STAT3, a transcription factor in downstream Flt3 signaling, leads to reduced lymphoid organ DC development,63 whereas overexpression and activation of STAT3 in flt3-negative hematopoietic progenitors rescued both pDC and DC differentiation potential.64 Consistently, deletion of the transcriptional repressor Gfi-1, which is involved in regulating STAT3 activation, leads, besides many other hematopoietic developmental deficiencies, to the reduction of all lymphoid tissue DCs, whereas LC numbers were increased.65 Importantly, although STAT3 deficiency blocks Flt3L-mediated pDC and DC development, it does not block GM-CSF–mediated DC development.63 GM-CSF promotes DC development via STAT5 that in turn via direct suppression of Irf-8 (also called ICSBP, described in “Transcription factors affecting specific DC populations”) inhibits pDC development. GM-CSF also leads to STAT3 activation and to Irf-4 expression, a transcription factor important in DC development66 (discussed in “Transcription factors affecting specific DC populations”). Indeed, pDCs develop in vitro in GM-CSF–stimulated cultures in the absence of STAT5, possibly mediated by STAT3 activation. In addition, GM-CSF–stimulated Stat5-deficient progenitors produce fewer DCs, and hematopoietic Stat5-deficient mice have a slight reduction of lymphoid organ DCs, paralleling the findings in GM-CSF–deficient animals37,66 (D. Kingston and M.G.M., unpublished data, January 2009). Steady-state lymphoid organ pDC maintenance, however, seems not to be suppressed by GM-CSF downstream STAT5 activation, as GM-CSF–deficient mice do not show increased pDC numbers (D. Kingston and M.G.M., unpublished data, January 2009).

Transcription factors affecting specific DC populations

The NF-κB/Rel family member RelB is expressed in lymphoid organs. RelB−/− mice have an altered thymic organ structure and develop myeloid hyperplasia and multiorgan inflammation.67 RelB is expressed in DCs, with relatively higher amounts in CD8α− DCs, and RelB deficiency leads to massive reduction of CD8α− DCs.68 In line with these findings, similar alterations of the lymphoid organ cDC compartment are observed in mice deficient in TRAF6, a TNF receptor–associated factor family protein, acting upstream of the NF-κB cascade.69

The ETS family of DNA binding proteins member PU.1 is a transcription factor expressed in hematopoietic cells, and its deletion causes embryonic or neonatal death. Mice reconstituted with Pu.1-deficient hematopoietic cells, in addition to other hematopoietic defects, have strong reduction in CD8α− and CD8α+ cDCs, and GM-CSF cannot induce DC differentiation from PU-1–deficient progenitors in vitro.70,71 PU-1 is also expressed on Flt3 signaling and enforced Pu.1 expression in Flt3− megakaryocyte-erythrocyte lineage committed hematopoietic progenitors is sufficient to permit the development of both pDCs and DCs.64 In human CD34+ progenitor cells, knockdown of Pu.1 inhibits pDC development, as did the knockdown of another ETS transcription factor, Spi-B.72

The interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) 2, 4, and 8 were described as key transcription factors involved in DC subset diversification. Irf-2–deficient mice display reduced CD8α− DCs and slightly reduced LCs,73 Irf-4–deficient mice have reduced CD8α− DCs and slightly reduced pDCs,74,75 and Irf-8 knockout mice have reduced CD8α+ DCs, pDCs, and LCs.76,77 In vitro DC differentiation on GM-CSF stimulation depends preferentially on IRF-4, whereas DC differentiation on Flt3L preferentially depends on IRF-8,75 in line with the differential use of STAT5 and STAT3 in GM-CSF and Flt3L-driven DC development.66

Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors (E12, E47, HEB, E2-2) act as transcriptional activators and are inhibited by counteracting HLH Id (inhibitors of DNA binding) proteins. It has been demonstrated that Id2 is induced during GM-CSF–driven DC development in vitro, and Id2-deficient mice have moderately increased pDCs, severely reduced CD8α+ DCs, and lack LCs.78 Interestingly, Tgf-β1 delivers the upstream signal for Id2; thus, LC deficiency in TGF-β1 knockout mice can be directly linked to the LC deficiency observed in Id2-deficient mice.78 In addition, very recently, hematopoietic deletion of basic helix-loop-helix E2-2 was shown to block pDC development at an immature stage in mice, and similar, haplo-insufficiency of E2-2 in humans leads to a functional pDC defect (Pitt-Hopkins syndrome).79 Ectopic expression of Id2 and Id3 in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells causes inhibition of pDC but not DC development in vitro,48 whereas ectopic expression of the transcriptional activating HLH gene E2A (encoding E12, E47) stimulates pDC development (similar as Spi-B discussed above in this section).72

Batf3, also known as Jun dimerization protein p21SNFT, has recently been discovered using global gene expression analysis as a molecule highly expressed in DCs, with low to absent expression in other immune cells and nonimmune tissues. Strikingly, Batf3−/− mice lack specifically CD8α+ DCs in the spleen and LN. Nonlymphoid tissue DCs have not been thoroughly studied, with the exception of the skin, where specific defect of CD103+ but not CD103− DCs, has been reported. Importantly, Batf3−/− mice are unable to mount antitumor and antiviral immune response establishing a key role for Batf3+ cells in the priming of CD8+ T cells.80 It is critical to explore in details the specific DC defects in nonlymphoid tissues of Batf3−/− mice because it is probable that additional defects in the nonlymphoid tissue compartment may participate in the immune phenotype.

Runx3, a member of the runt domain family of transcription factors, mediates TGF-β responses. Lack of Runx3 in mature DCs results in loss of TGF-β–mediated inhibition of maturation, therefore leading to DC activation and inflammation. Importantly, lack of appropriate TGF-β–induced Runx3 signaling also leads to a defect in LC development.78,81

Differentiation of DCs from hematopoietic progenitor cells

Hematopoiesis is hierarchically structured. A small fraction of self-renewing hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in BM gives rise to non–self-renewing multipotent progenitors, which will give rise to proliferating progenitors with gradually restricted developmental options that finally differentiate into mature, mostly nondividing cells. Early committed progenitors as clonal common lymphoid progenitors and clonal common myeloid progenitors have been identified in mice and humans.82 In addition to these committed progenitors, more recent studies reveal overlapping and alternative graded stages of early lineage commitment.83

Early hematopoietic development

Early lymphoid and myeloid committed progenitors maintain developmental options for all DCs and pDCs in mice and humans.23,24,49,84,85 It is important to note that adoptive transfer of myeloid and lymphoid progenitors from BM into irradiated animals revealed a similar bias toward CD8α+ DC generation as observed in initial studies investigating adoptive transfer of early thymocyte progenitors. Thus, it is now accepted that both myeloid and lymphoid progenitors give rise to lymphoid organ CD8α+ and CD8α− DCs and the term “lymphoid” and “myeloid” DCs should not be used any more in this context.23,24,84,86 DC generation from early committed progenitors is transient and lasts for 2 to 4 weeks, in accordance with lack of progenitor and DC self-renewal potential. Subsequent studies revealed that maintenance of DC developmental options by hematopoietic progenitors is linked to Flt3 expression and to their ability to respond to Flt3L.43,87,88 Consistent with these data, enforced flt3 expression in early progenitor cells opens access to a DC differentiation program that can be used if no competing signals occur.64

Restriction to DC lineages

Given the fact that DC developmental options are maintained in Flt3+ early progenitors, the subsequent question was to determine whether DC-committed precursors exist in the BM. Several candidates have been recently identified that we here divide into 3 groups based on their proliferation potential (Table 2).

Table 2.

DC progenitor populations

| Group/precursor population name | Site of isolation | Ex vivo sorting immunophenotype | Frequency, percentage | Differentiation potential in vitro | Clonal potential in vitro | Differentiation potential in vivo | Conditions | Peak day of progeny and fold expansion of input in spleen | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early DC progenitors (c-Kit+, high proliferation potential) | |||||||||

| MDPs (macrophage and DC progenitor) | BM | Lin−CD117+CX3CR1+CD11b− | 0.5 | DC, Mac | DC, Mac | S, peritoneum: Mo, DC, Mac | U, RT, IF peritoneum | Day 7, 10× (RT) | 89 |

| MDPD (macrophage and DC progenitor) | BM | Lin−CD117+/−CD115+ | 0.2 | NA | NA | S:DC, Mac | RT | NA | 90 |

| CDPs (common DC progenitors) | BM | Lin−CD117intCD135+ CD115+ CD127− | 0.1 | pDC, DC | pDC, DC | S, LN: pDC, DC | U, RT | Day 10, 7-8× (RT) | 58 |

| Pro-DCs | BM | Lin−CD117intCD135+ CD16/32lo | NA | pDC, DC | pDC, DC | S: pDC, DC | U | Day 8?, 0.05×* | 91 |

| Late DC progenitors (c-Kit−, low proliferation potential) | |||||||||

| DC progenitors B220+ | BM | CD11c+MHC class II−B220+ | 0.3 | pDC, DC | NA | S: pDC, DC | RT | Day 7?, 0.01× (RT) | 92 |

| DC progenitors B220− | BM | CD11c+MHC class II−B220− | 0.2 | DC | NA | S: DC | RT | Day 7?, 0.03× (RT) | 92 |

| Preimmunocyte | BM | CD11c+CD31+Ly6C+ | 0.5-1 | pDC, DC, Mac | NA | NA | NA | NA | 93 |

| DC precursors | Blood | CD11c+MHC class II− | 5 | NA | NA | S: pDC, DC | RT | Day 14, 1× | 36† |

| Pre-cDCs | Spleen | CD11cintCD45RAlo CD43intSIRP-aint | 0.05 | DC | NA | S: DC | U | Day 5, 0.02×* | 94 |

| Monocytes (no proliferation potential) | |||||||||

| Monocytes | BM | Ly6Chi (Gr-1hi) | NA | NA | DC | IF spleen | Day 2 | 94 | |

| Monocytes | Blood | Gr-1hi | NA | NA | LC | IF skin | 56 | ||

| Monocytes | BM | Gr-1hi inflammatory | NA | NA | DC | IF intestine + lung | 97 | ||

| Monocytes | BM | Gr-1hi and Gr-1− | NA | NA | DC | IF lung | 96 | ||

| Monocytes | Blood | Gr-1hi | NA | NA | DC | IF vagina | 12 | ||

Data acquired in cellular transfer models.

U indicates unconditioned animals (ie, “steady-state” differentiation upon transfer in nonirradiated and noninflamed animals); RT, irradiation before transfer; IF, induction of inflammation before or after transfer; S, spleen; LC, Langerhans cell; and NA, not available.

Expansion in nonirradiated animals cannot be compared with expansion in irradiated animals.

Population contained DX5+ NK cells; purification of restricted blood DC precursors remains to be established.

The first group comprises “early DC progenitors” present in the BM. These progenitors have high proliferative capacity and express CD117 (c-kit, the receptor for stem cell factor) but no mature lineage marker. In clonal in vitro assays and on in vivo transfer, they generate offspring cells severalfold the progenitor input numbers. This group includes “macrophage and DC progenitors” (MDPs)89 and “MDPΔ,”90 which give rise exclusively to monocytes, macrophages, and DCs, and “common DC progenitors”58 and “pro-DCs,”91 which give rise exclusively to pDCs and DCs.

The second group consists of further differentiated “late DC progenitors” that are CD117 negative and express CD11c but not MHC class II surface molecules and have low proliferative capacity. In this group, clonal in vitro assays were not feasible with current methods, and on transfer in irradiation conditioned hosts, the recovery of progeny cells in the spleen is severalfold lower than input numbers. This group includes BM CD11c+ MHC class II−B220+ cells, which generate exclusively pDCs and DCs, CD11c+ MHC class II−B220− cells, which give rise exclusively to DCs,92 “preimmunocytes,”93 which give rise to pDCs, DCs, and macrophages, and peripheral blood “DC precursors,”36 which generate spleen pDCs and DCs, and finally spleen “pre-cDCs,”94 which generate spleen DCs, but no pDCs.

The third group consists of nonproliferating Gr-1hi monocytes with immediate DC precursor potential. DC differentiation in this group has been described mostly at inflamed sites.12,56,94–97

It will now be important to clarify whether different early and late progenitor populations are strictly distinct and multiple pathways to DC development exist, or whether, as most probably the case, some are overlapping. In particular, it will be critical to evaluate the intuitive evolutionary macrophage-DC linkage and to delineate the mechanisms regulating the differentiation and branching points of monocyte, macrophage, DC, and pDC potential. Finally, and most importantly, the relative contribution of progenitors to the DCs compartments in the steady state and during inflammation needs to be determined.

The LC exception

In contrast to most DC populations, LCs are maintained locally independently of circulating precursors in the steady state.16 This could be via true self-renewal and/or via specialized local LC precursor cells. The bulge region of the hair follicle serves as a niche for keratinocytes, melanocytes, and mast-cell progenitors, and there is evidence suggesting that, after epidermal injuries, LCs can be repopulated from the follicles alone.98 Conditional depletion of LCs and careful monitoring of their repopulation should help to resolve these issues. In contrast, in inflamed settings, LCs are replaced by circulating Gr-1hi monocytes in a M-CSFR–dependent manner.56

A DC homeostasis integrated view

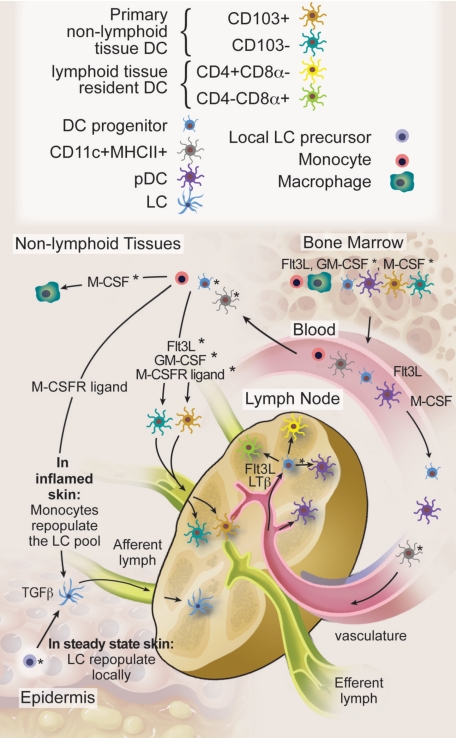

An integrated view on DC homeostasis is starting to emerge from the data discussed in previous sections (Figure 2). All current data indicate that homeostasis of short-lived lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissue DCs with the exception of the LCs relies on continuous input from blood-borne cells.22,23,84,90,99

Figure 2.

DC migration and homeostasis. HSCs produce DC progenitors, pDCs, and DCs in the BM. Flt3 ligand is a nonredundant cytokine for BM DC differentiation, although the exact role of GM-CSF and M-CSFR ligands remains to be determined. BM-derived circulating blood cells maintain, with the exception of epidermal LCs, all known steady-state DC homeostasis in lymphoid and nonlymphoid tissues. We hypothesize that progenitor cells with limited proliferation potential on Flt3 ligand and LTβ stimulation enter the LNs through high endothelial venules to maintain the majority of LN DCs in steady state. It is also possible that nonproliferating blood DCs follow the same route. In addition, nonlymphoid tissue DCs continuously enter the LNs through afferent lymphatics, but these represent only a minority of steady-state LN DCs. The specific contribution of proliferating DC progenitors, blood DCs, and monocytes to nonlymphoid tissue DCs in the steady state and the relative involvement of cytokines as Flt3 ligand, GM-CSF, and M-CSFR ligands remain to be to be addressed. In contrast to most DCs, LCs repopulate locally in the steady state either through self-renewal or through a local hematopoietic precursor that takes residence in the skin. In inflamed skin, monocytes repopulate the LC pool via a TGF-β and monocyte colony-stimulating factor receptor–dependent pathway. In the steady state, pDCs are recruited to the LN and other lymphoid organs directly from the blood and, with the exception of the liver, enter most nonlymphoid tissues only on inflammation. Whether lymphoid organ pDCs also derive from DC precursors that enter the organs remains to be determined. *Likely, but not formally proven. Professional illustration by Debra T. Dartez.

In steady-state spleen, and probably also in LN and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, DCs enter as progenitor cells (MHC class II−CD11c+) with limited proliferation potential and differentiate into all DC subtypes.94 If local, lymphoid-organ Flt3L and LTβ cause a 2- to 4-fold division of homed DC progenitors and immature DCs, this local mechanism accounts for a substantial expansion of entering cells and thus contributes importantly to respective DC numbers.21,22,90,94 Whether entering progenitors also harbor pDC differentiation potential remains to be determined.58 Indeed, pDCs are present in the BM and in the blood, suggesting that pDC and DC developmental pathways may segregate earlier and that relevant amounts of pDCs may be recruited separately. In contrast to spleen and LN, a majority of thymic DCs differentiate in situ from early thymic progenitors, and only a small fraction of DCs or their immediate progenitors are recruited from blood. Steady-state lymphoid organ DC homeostasis is primarily driven by Flt3L in BM, blood, and in lymphoid organs themselves, and corresponds to Flt3 expression on proliferative DC progenitors.41,43,58,63,87,89–91

The cellular correlates and the cytokines that maintain constant homeostatic steady-state replacement of DCs in nonlymphoid tissue that continuously travel to draining LNs is less clear. Both DC progenitors and monocytes could contribute to this process. Monocytes infiltrate nonlymphoid tissues in steady state and they express Gm-csf and M-csfr, but little or no Flt3 mRNA43 (D. Kingston and M.G.M., unpublished data, January 2009), and it is possible by analogy to in vitro findings that they require minute amounts of tissue GM-CSF and/or M-CSF to differentiate into DCs. In contrast to most DCs, LCs repopulate locally in the steady state, either through self-renewal or through a local hematopoietic precursor that takes residence in the skin.

The development of DCs in inflamed nonlymphoid tissues has been more thoroughly studied. In this setting, monocytes differentiate into DCs and several cytokines, including GM-CSF, TNF-α, and IL-4, may play a role in this process.12,56,94–97 As Flt3L is produced by activated T cells and Flt3L levels increase on systemic infection, Flt3L may also contribute to inflammatory nonlymphoid tissue monocyte to DC development by increasing monocyte numbers in peripheral blood.43 Furthermore, HSCs, known to continuously circulate in small numbers in steady-state blood,100 were identified in nonlymphoid tissues and in circulating lymph and might give rise to additional DCs at inflamed sites in emergency hematopoiesis,101 a process where early progenitor cell expressed Toll-like receptor signaling might enhance DC differentiation, short-cutting usual maturation steps.102

In contrast to DCs, pDCs locate in lymphoid tissues, BM, and liver, but are rarely found in other tissues in the steady state, whereas they are recruited in most tissue on tissue injury.7 The exact mechanisms that control pDC trafficking remain to be identified.

DCs in hematologic disease

DC neoplasms

The 3 main hematopoietic DC neoplasms include Langerhans cell histiocytosis, interdigitating DC sarcoma, and pDC leukemia/hematodermic neoplasm. Because DC neoplasms are beyond the scope of this review, we will only discuss a few aspects of these diseases in the context of DC development and homeostasis.

First, the low prevalence of DC neoplasms has been attributed to DC capacity to initiate antitumor immunity and used as an argument for tumor immunosurveillance. An alternative hypothesis is that the short DC half-life of mature DCs reduces the risk for acquiring sufficient transforming genetic mutations. Indeed, the most frequent DC neoplasm is Langerhans cell histiocytosis, a neoplasia derived from long-term locally repopulating LCs. This hypothesis would be consistent with recent understanding of the origin of cancer initiating cells or cancer stem cells from somatic tissue stem cells.103

Second, it was shown that approximately one-third of acute myeloid leukemias carry Flt3 gene mutations (internal tandem duplications and kinase domain mutations), leading to constitutive activation of Flt3 signaling.104 Given the relevance of Flt3 signaling for DC homeostasis, it is intriguing that these mutations have not been associated with or lead to DC neoplasias. This might be because, although Flt3 signaling is required for DC homeostasis, it also plays a role in early development of most hematopoietic lineages. More importantly, downstream signaling pathways of mutated, constitutively active Flt3 probably differ from wild-type stimulated Flt3. In contrast to wild-type Flt3 signaling, constitutively active signaling of Flt3-internal tandem mutations represses PU.1 and c/EBPα and activates STAT5 in a suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS)–resistant fashion, probably a result of unphysiologic subcellular compartmentalization of the mutated protein.105

Third, early pDC leukemia/lymphoma (pDCL, CD4+CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm) was recently classified in the 2005 World Health Organization/European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification of cutaneous lymphomas as a separate entity. pDCL cells coexpress pDC surface antigens and transcription factors such as IRF-8 and PU.1, produce interferon-α on viral stimulation, and can mature into DCs that efficiently prime T cells, and typically locate in organs that are infiltrated by pDCs on inflammation.106,107 Interestingly, although no activating Flt3 mutations and only 13q12 deletions leading to allelic loss of Flt3 were detected, expression of surface Flt3 was found to be elevated in pDCL.108 The biologic relevance of this, however, still needs to be determined.

DCs in allo-HCT

The immunologic activity of donor T cells in allo-HCT grafts is a critical factor in eradicating residual recipient hematopoiesis and malignancy, a process called graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) response, but can also lead to detrimental graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).109 There is ample evidence that both GVHD and GVL are dependent on remaining host APC, of which DCs are the most potent.15,110

GVL appears to occur at a lower threshold than GVHD in studies of escalated donor lymphocyte infusions (DLI) in mice and humans.109 In murine models, recipient DCs present in the spleen or the LN are in contact with donor T cells and are sufficient to prime robust GVL responses,111–113 whereas in the absence of inflammation, peripheral tissues are not infiltrated by alloreactive donor T cells,113 conferring a selective benefit in promoting GVL without GVHD.111–113 This underpins the logic of delayed T-cell add-back strategies and preemptive DLI, which allows the inflammatory insult of conditioning to subside before the infusion of donor T cells.

The importance of recipient DCs in initiating GVHD has also been clearly established. Recipient animals with defective APC show attenuation of acute CD8+ T cell–mediated GVHD114,115 and recipient DC “add-back” is sufficient to induce GVHD.116 It is possible host DC subsets that resist the transplantation conditioning such as LCs and have a sufficiently long half-life could play a role in the predilection of GVHD for certain target organs. Indeed, cutaneous host DCs are sufficient to generate cutaneous GVHD on DLI.117 In contrast to skin, other GVHD target organs have not yet been closely scrutinized. The gut and associated Peyer patches may harbor radio-resistant DC precursors, even though rapid turnover of mesenteric LN DC is apparent.16 In the liver, the bulk of parenchymal DCs rapidly equilibrate with the blood,117 but this does not exclude a niche population of cycling DCs in focal GVHD targets such as the portal triad of the liver.

The role of DCs in cutaneous GVHD in human allo-HCT is starting to be unraveled. As in mice, human LCs and dermal DCs survive conditioning therapy in significant numbers.17,118 A recent study on a limited number of allo-HCT patients treated with reduced intensity and nonmyeloablative regimen suggest that recipient cutaneous DC survival is linked to the intensity of conditioning and to GVHD.17,119 The correlations between cutaneous DC chimerism, GVHD kinetics, and risk of tumor relapse are currently investigated in a more extensive study (M. Mielcarek, M. Collin, and M.M., unpublished data, January 2009).

Future directions in research and possible clinical implementation

Thirty-five years after their discovery, DCs have now emerged as key modulators of immune processes, including antimicrobial immunity, tumor immunity, autoimmunity, atherosclerosis, and posttransplantation immune responses. These immune functions are maintained by a heterogeneous population of DCs with specialized functions. It is critical to understand the mechanisms that regulate the homeostasis of DC subsets to better use their therapeutic potential. This will require investigating the mechanisms that regulate DC development, trafficking, localization, and turnover in specialized niches in vivo, studies that will be possible with currently evolving labeling and in vivo imaging technology. Furthermore, selective targeting of DCs in vivo or ex vivo, for example, via specific antibody or small molecules, may lead to new immunomodulation strategies that will be beneficial for the treatment of several human diseases. A main challenge for the future is to translate what we have learned from the mouse into humans and better explore the diversity of human lymphoid and nonlymphoid organ DC populations. Toward this aim, improving availability of human tissue samples and establishing more relevant mouse models for the study of the human immune system will be useful.120,121

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant nos. R01CA1121100 and R01AI0086899) to M.M. and the Swiss National Science Foundation (310000-116637), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (MA 2159/2-1), and the European Commission Sixth Framework Programme Network of Excellence initiative (LSHB-CT-2004-512074 DC-THERA) to M.G.M.

Note added in proof.

C. Auffray and F. Geissman, and K. Liu and M. Nussenzweig, now demonstrate that MDP, in addition to producing monocytes/macrophages and DCs, can also produce pDCs. Using adoptive transfer experiments, K. Liu and M. Nussenzweig also found that MDP downstream development branches into monocytes/macrophages and CDPs (Auffray et al125; Liu et al126).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: M.M. and M.G.M. wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Miriam Merad, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Gene and Cell Medicine and the Department of Medicine, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, 1425 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10029; e-mail: miriam.merad@mssm.edu; or Markus G. Manz, MD, Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB), Via Vincenzo Vela 6, 6500 Bellinzona, Switzerland and Oncology Institute of Southern Switzerland (IOSI), CH-6500 Bellinzona, Switzerland; e-mail: manz@irb.unisi.ch.

References

- 1.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hart DN. Dendritic cells: unique leukocyte populations which control the primary immune response. Blood. 1997;90:3245–3287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caux C, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Schmitt D, Banchereau J. GM-CSF and TNF-alpha cooperate in the generation of dendritic Langerhans cells. Nature. 1992;360:258–261. doi: 10.1038/360258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inaba K, Inaba M, Romani N, et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1994;179:1109–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu YJ. IPC: professional type 1 interferon-producing cells and plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:275–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginhoux F, Collin MP, Bogunovic M, et al. Blood-derived dermal langerin+ dendritic cells survey the skin in the steady state. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3133–3146. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poulin LF, Henri S, de Bovis B, Devilard E, Kissenpfennig A, Malissen B. The dermis contains langerin+ dendritic cells that develop and function independently of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3119–3131. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Randolph GJ, Ochando J, Partida-Sanchez S. Migration of dendritic cell subsets and their precursors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:293–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bujdoso R, Hopkins J, Dutia BM, Young P, McConnell I. Characterization of sheep afferent lymph dendritic cells and their role in antigen carriage. J Exp Med. 1989;170:1285–1301. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iijima N, Linehan MM, Saeland S, Iwasaki A. Vaginal epithelial dendritic cells renew from bone marrow precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19061–19066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707179104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holt PG, Haining S, Nelson DJ, Sedgwick JD. Origin and steady-state turnover of class II MHC-bearing dendritic cells in the epithelium of the conducting airways. J Immunol. 1994;153:256–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugh CW, MacPherson GG, Steer HW. Characterization of nonlymphoid cells derived from rat peripheral lymph. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1758–1779. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.6.1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merad M, Ginhoux F, Collin M. Origin, homeostasis and function of Langerhans cells and other langerin-expressing dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:935–947. doi: 10.1038/nri2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merad M, Manz MG, Karsunky H, et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collin MP, Hart DN, Jackson GH, et al. The fate of human Langerhans cells in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Exp Med. 2006;203:27–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanitakis J, Petruzzo P, Dubernard JM. Turnover of epidermal Langerhans' cells. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2661–2662. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200412163512523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2002:151–161. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.den Haan JM, Lehar SM, Bevan MJ. CD8(+) but not CD8(-) dendritic cells cross-prime cytotoxic T cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1685–1696. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kabashima K, Banks TA, Ansel KM, Lu TT, Ware CF, Cyster JG. Intrinsic lymphotoxin-beta receptor requirement for homeostasis of lymphoid tissue dendritic cells. Immunity. 2005;22:439–450. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu K, Waskow C, Liu X, Yao K, Hoh J, Nussenzweig M. Origin of dendritic cells in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:578–583. doi: 10.1038/ni1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manz MG, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Dendritic cell potentials of early lymphoid and myeloid progenitors. Blood. 2001;97:3333–3341. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traver D, Akashi K, Manz M, et al. Development of CD8alpha-positive dendritic cells from a common myeloid progenitor. Science. 2000;290:2152–2154. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwasaki A. Mucosal dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:381–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu L, Shortman K. Heterogeneity of thymic dendritic cells. Semin Immunol. 2005;17:304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brocker T, Riedinger M, Karjalainen K. Targeted expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules demonstrates that dendritic cells can induce negative but not positive selection of thymocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;185:541–550. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonasio R, Scimone ML, Schaerli P, Grabie N, Lichtman AH, von Andrian UH. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamath AT, Henri S, Battye F, Tough DF, Shortman K. Developmental kinetics and lifespan of dendritic cells in mouse lymphoid organs. Blood. 2002;100:1734–1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donskoy E, Goldschneider I. Two developmentally distinct populations of dendritic cells inhabit the adult mouse thymus: demonstration by differential importation of hematogenous precursors under steady state conditions. J Immunol. 2003;170:3514–3521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Raper A, Sugita N, et al. Characterization of Siglec-H as a novel endocytic receptor expressed on murine plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors. Blood. 2006;107:3600–3608. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colonna M, Trinchieri G, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells in immunity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1219–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Keeffe M, Hochrein H, Vremec D, et al. Mouse plasmacytoid cells: long-lived cells, heterogeneous in surface phenotype and function, that differentiate into CD8(+) dendritic cells only after microbial stimulus. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1307–1319. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caminschi I, Proietto AI, Ahmet F, et al. The dendritic cell subtype-restricted C-type lectin Clec9A is a target for vaccine enhancement. Blood. 2008;112:3264–3273. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sancho D, Mourao-Sa D, Joffre OP, et al. Tumor therapy in mice via antigen targeting to a novel, DC-restricted C-type lectin. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2098–2110. doi: 10.1172/JCI34584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.del Hoyo GM, Martin P, Vargas HH, Ruiz S, Arias CF, Ardavin C. Characterization of a common precursor population for dendritic cells. Nature. 2002;415:1043–1047. doi: 10.1038/4151043a. [erratum in Nature. 2004;429:205] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vremec D, Lieschke GJ, Dunn AR, Robb L, Metcalf D, Shortman K. The influence of granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor on dendritic cell levels in mouse lymphoid organs. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:40–44. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maraskovsky E, Brasel K, Teepe M, et al. Dramatic increase in the numbers of functionally mature dendritic cells in Flt3 ligand-treated mice: multiple dendritic cell subpopulations identified. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1953–1962. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamilton JA. Colony-stimulating factors in inflammation and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:533–544. doi: 10.1038/nri2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dranoff G, Jaffee E, Lazenby A, et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3539–3543. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenna HJ, Stocking KL, Miller RE, et al. Mice lacking flt3 ligand have deficient hematopoiesis affecting hematopoietic progenitor cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer cells. Blood. 2000;95:3489–3497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tussiwand R, Onai N, Mazzucchelli L, Manz MG. Inhibition of natural type I IFN-producing and dendritic cell development by a small molecule receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor with Flt3 affinity. J Immunol. 2005;175:3674–3680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karsunky H, Merad M, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Manz MG. Flt3 ligand regulates dendritic cell development from Flt3+ lymphoid and myeloid-committed progenitors to Flt3+ dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2003;198:305–313. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bjorck P. Isolation and characterization of plasmacytoid dendritic cells from Flt3 ligand and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-treated mice. Blood. 2001;98:3520–3526. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.13.3520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brasel K, De Smedt T, Smith JL, Maliszewski CR. Generation of murine dendritic cells from flt3-ligand-supplemented bone marrow cultures. Blood. 2000;96:3029–3039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gilliet M, Boonstra A, Paturel C, et al. The development of murine plasmacytoid dendritic cell precursors is differentially regulated by FLT3-ligand and granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 2002;195:953–958. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blom B, Ho S, Antonenko S, Liu YJ. Generation of interferon alpha-producing predendritic cell (Pre-DC)2 from human CD34(+) hematopoietic stem cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1785–1796. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spits H, Couwenberg F, Bakker AQ, Weijer K, Uittenbogaart CH. Id2 and Id3 inhibit development of CD34(+) stem cells into predendritic cell (pre-DC)2 but not into pre-DC1: evidence for a lymphoid origin of pre-DC2. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1775–1784. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.12.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chicha L, Jarrossay D, Manz MG. Clonal type I interferon-producing and dendritic cell precursors are contained in both human lymphoid and myeloid progenitor populations. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1519–1524. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pulendran B, Banchereau J, Burkeholder S, et al. Flt3-ligand and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor mobilize distinct human dendritic cell subsets in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;165:566–572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lyman SD, Jacobsen SE. c-kit ligand and Flt3 ligand: stem/progenitor cell factors with overlapping yet distinct activities. Blood. 1998;91:1101–1134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birnberg T, Bar-On L, Sapoznikov A, et al. Lack of conventional dendritic cells is compatible with normal development and T cell homeostasis, but causes myeloid proliferative syndrome. Immunity. 2008;29:986–997. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshida H, Hayashi S, Kunisada T, et al. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990;345:442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dai XM, Ryan GR, Hapel AJ, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor gene results in osteopetrosis, mononuclear phagocyte deficiency, increased primitive progenitor cell frequencies, and reproductive defects. Blood. 2002;99:111–120. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Witmer-Pack MD, Hughes DA, Schuler G, et al. Identification of macrophages and dendritic cells in the osteopetrotic (op/op) mouse. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:1021–1029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ginhoux F, Tacke F, Angeli V, et al. Langerhans cells arise from monocytes in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:265–273. doi: 10.1038/ni1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Macdonald KP, Rowe V, Bofinger HM, et al. The colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor is expressed on dendritic cells during differentiation and regulates their expansion. J Immunol. 2005;175:1399–1405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Onai N, Obata-Onai A, Schmid MA, Ohteki T, Jarrossay D, Manz MG. Identification of clonogenic common Flt3+M-CSFR+ plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1207–1216. doi: 10.1038/ni1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fancke B, Suter M, Hochrein H, O'Keeffe M. M-CSF: a novel plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell poietin. Blood. 2008;111:150–159. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-089292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Borkowski TA, Letterio JJ, Farr AG, Udey MC. A role for endogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 in Langerhans cell biology: the skin of transforming growth factor beta 1 null mice is devoid of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2417–2422. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strobl H, Riedl E, Scheinecker C, et al. TGF-beta 1 promotes in vitro development of dendritic cells from CD34+ hemopoietic progenitors. J Immunol. 1996;157:1499–1507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaplan DH, Li MO, Jenison MC, Shlomchik WD, Flavell RA, Shlomchik MJ. Autocrine/paracrine TGFbeta1 is required for the development of epidermal Langerhans cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2545–2552. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laouar Y, Welte T, Fu XY, Flavell RA. STAT3 is required for Flt3L-dependent dendritic cell differentiation. Immunity. 2003;19:903–912. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00332-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Onai N, Obata-Onai A, Tussiwand R, Lanzavecchia A, Manz MG. Activation of the Flt3 signal transduction cascade rescues and enhances type I interferon-producing and dendritic cell development. J Exp Med. 2006;203:227–238. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rathinam C, Geffers R, Yucel R, et al. The transcriptional repressor Gfi1 controls STAT3-dependent dendritic cell development and function. Immunity. 2005;22:717–728. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esashi E, Wang YH, Perng O, Qin XF, Liu YJ, Watowich SS. The signal transducer STAT5 inhibits plasmacytoid dendritic cell development by suppressing transcription factor IRF8. Immunity. 2008;28:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burkly L, Hession C, Ogata L, et al. Expression of relB is required for the development of thymic medulla and dendritic cells. Nature. 1995;373:531–536. doi: 10.1038/373531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu L, D'Amico A, Winkel KD, Suter M, Lo D, Shortman K. RelB is essential for the development of myeloid-related CD8alpha− dendritic cells but not of lymphoid-related CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. Immunity. 1998;9:839–847. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80649-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kobayashi T, Walsh PT, Walsh MC, et al. TRAF6 is a critical factor for dendritic cell maturation and development. Immunity. 2003;19:353–363. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Anderson KL, Perkin H, Surh CD, Venturini S, Maki RA, Torbett BE. Transcription factor PU.1 is necessary for development of thymic and myeloid progenitor-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:1855–1861. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guerriero A, Langmuir PB, Spain LM, Scott EW. PU.1 is required for myeloid-derived but not lymphoid-derived dendritic cells. Blood. 2000;95:879–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schotte R, Nagasawa M, Weijer K, Spits H, Blom B. The ETS transcription factor Spi-B is required for human plasmacytoid dendritic cell development. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1503–1509. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ichikawa E, Hida S, Omatsu Y, et al. Defective development of splenic and epidermal CD4+ dendritic cells in mice deficient for IFN regulatory factor-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3909–3914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400610101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suzuki S, Honma K, Matsuyama T, et al. Critical roles of interferon regulatory factor 4 in CD11bhighCD8alpha− dendritic cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8981–8986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402139101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tamura T, Tailor P, Yamaoka K, et al. IFN regulatory factor-4 and -8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:2573–2581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Aliberti J, Schulz O, Pennington DJ, et al. Essential role for ICSBP in the in vivo development of murine CD8alpha+ dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;101:305–310. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Borghi P, et al. ICSBP is critically involved in the normal development and trafficking of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103:2221–2228. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hacker C, Kirsch RD, Ju XS, et al. Transcriptional profiling identifies Id2 function in dendritic cell development. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:380–386. doi: 10.1038/ni903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cisse B, Caton ML, Lehner M, et al. Transcription factor E2-2 is an essential and specific regulator of plasmacytoid dendritic cell development. Cell. 2008;135:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, et al. Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science. 2008;322:1097–1100. doi: 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fainaru O, Woolf E, Lotem J, et al. Runx3 regulates mouse TGF-beta-mediated dendritic cell function and its absence results in airway inflammation. EMBO J. 2004;23:969–979. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kondo M, Wagers AJ, Manz MG, et al. Biology of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors: implications for clinical application. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:759–806. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Buza-Vidas N, Luc S, Jacobsen SE. Delineation of the earliest lineage commitment steps of haematopoietic stem cells: new developments, controversies and major challenges. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:315–321. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3281de72bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wu L, D'Amico A, Hochrein H, O'Keeffe M, Shortman K, Lucas K. Development of thymic and splenic dendritic cell populations from different hemopoietic precursors. Blood. 2001;98:3376–3382. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Shigematsu H, Reizis B, Iwasaki H, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells activate lymphoid-specific genetic programs irrespective of their cellular origin. Immunity. 2004;21:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ardavin C, Wu L, Li CL, Shortman K. Thymic dendritic cells and T cells develop simultaneously in the thymus from a common precursor population. Nature. 1993;362:761–763. doi: 10.1038/362761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.D'Amico A, Wu L. The early progenitors of mouse dendritic cells and plasmacytoid predendritic cells are within the bone marrow hemopoietic precursors expressing Flt3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:293–303. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mende I, Karsunky H, Weissman IL, Engleman EG, Merad M. Flk2+ myeloid progenitors are the main source of Langerhans cells. Blood. 2006;107:1383–1390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fogg DK, Sibon C, Miled C, et al. A clonogenic bone marrow progenitor specific for macrophages and dendritic cells. Science. 2006;311:83–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1117729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Waskow C, Liu K, Darrasse-Jeze G, et al. The receptor tyrosine kinase Flt3 is required for dendritic cell development in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:676–683. doi: 10.1038/ni.1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Naik SH, Sathe P, Park HY, et al. Development of plasmacytoid and conventional dendritic cell subtypes from single precursor cells derived in vitro and in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1217–1226. doi: 10.1038/ni1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Diao J, Winter E, Chen W, Cantin C, Cattral MS. Characterization of distinct conventional and plasmacytoid dendritic cell-committed precursors in murine bone marrow. J Immunol. 2004;173:1826–1833. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bruno L, Seidl T, Lanzavecchia A. Mouse pre-immunocytes as non-proliferating multipotent precursors of macrophages, interferon-producing cells, CD8alpha(+) and CD8alpha(−) dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:3403–3412. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200111)31:11<3403::aid-immu3403>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Naik SH, Metcalf D, van Nieuwenhuijze A, et al. Intrasplenic steady-state dendritic cell precursors that are distinct from monocytes. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:663–671. doi: 10.1038/ni1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Randolph GJ, Inaba K, Robbiani DF, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 1999;11:753–761. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Landsman L, Varol C, Jung S. Distinct differentiation potential of blood monocyte subsets in the lung. J Immunol. 2007;178:2000–2007. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Varol C, Landsman L, Fogg DK, et al. Monocytes give rise to mucosal, but not splenic, conventional dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:171–180. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gilliam AC, Kremer IB, Yoshida Y, et al. The human hair follicle: a reservoir of CD40+ B7-deficient Langerhans cells that repopulate epidermis after UVB exposure. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:422–427. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Traver D, Akashi K, Manz M, et al. Development of CD8alpha-positive dendritic cells from a common myeloid progenitor. Science. 2000;290:2152–2154. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wright DE, Wagers AJ, Gulati AP, Johnson FL, Weissman IL. Physiological migration of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Science. 2001;294:1933–1936. doi: 10.1126/science.1064081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Massberg S, Schaerli P, Knezevic-Maramica I, et al. Immunosurveillance by hematopoietic progenitor cells trafficking through blood, lymph, and peripheral tissues. Cell. 2007;131:994–1008. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nagai Y, Garrett KP, Ohta S, et al. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dick JE. Stem cell concepts renew cancer research. Blood. 2008;112:4793–4807. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-077941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Small D. FLT3 mutations: biology and treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2006:178–184. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Choudhary C, Brandts C, Schwable J, et al. Activation mechanisms of STAT5 by oncogenic Flt3-ITD. Blood. 2007;110:370–374. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Marafioti T, Paterson JC, Ballabio E, et al. Novel markers of normal and neoplastic human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;111:3778–3792. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chaperot L, Bendriss N, Manches O, et al. Identification of a leukemic counterpart of the plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Blood. 2001;97:3210–3217. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Dijkman R, van Doorn R, Szuhai K, Willemze R, Vermeer MH, Tensen CP. Gene-expression profiling and array-based CGH classify CD4+CD56+ hematodermic neoplasm and cutaneous myelomonocytic leukemia as distinct disease entities. Blood. 2007;109:1720–1727. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-018143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kolb HJ. Graft-versus-leukemia effects of transplantation and donor lymphocytes. Blood. 2008;112:4371–4383. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Chakraverty R, Sykes M. The role of antigen-presenting cells in triggering graft-versus-host disease and graft-versus-leukemia. Blood. 2007;110:9–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-022038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mapara MY, Kim YM, Wang SP, Bronson R, Sachs DH, Sykes M. Donor lymphocyte infusions mediate superior graft-versus-leukemia effects in mixed compared to fully allogeneic chimeras: a critical role for host antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2002;100:1903–1909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Reddy P, Maeda Y, Liu C, Krijanovski OI, Korngold R, Ferrara JL. A crucial role for antigen-presenting cells and alloantigen expression in graft-versus-leukemia responses. Nat Med. 2005;11:1244–1249. doi: 10.1038/nm1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chakraverty R, Cote D, Buchli J, et al. An inflammatory checkpoint regulates recruitment of graft-versus-host reactive T cells to peripheral tissues. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2021–2031. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shlomchik WD, Couzens MS, Tang CB, et al. Prevention of graft versus host disease by inactivation of host antigen-presenting cells. Science. 1999;285:412–415. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5426.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang Y, Louboutin JP, Zhu J, Rivera AJ, Emerson SG. Preterminal host dendritic cells in irradiated mice prime CD8+ T cell-mediated acute graft-versus-host disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1335–1344. doi: 10.1172/JCI14989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Duffner UA, Maeda Y, Cooke KR, et al. Host dendritic cells alone are sufficient to initiate acute graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2004;172:7393–7398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Merad M, Hoffmann P, Ranheim E, et al. Depletion of host Langerhans cells before transplantation of donor alloreactive T cells prevents skin graft-versus-host disease. Nat Med. 2004;10:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nm1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fagnoni FF, Oliviero B, Giorgiani G, et al. Reconstitution dynamics of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cell precursors after allogeneic myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:281–289. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-07-2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bogunovic M, Ginhoux F, Wagers A, et al. Identification of a radio-resistant and cycling dermal dendritic cell population in mice and men. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2627–2638. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Aspord C, Pedroza-Gonzalez A, Gallegos M, et al. Breast cancer instructs dendritic cells to prime interleukin 13-secreting CD4+ T cells that facilitate tumor development. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1037–1047. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Manz MG. Human-hemato-lymphoid-system mice: opportunities and challenges. Immunity. 2007;26:537–541. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu L, Nichogiannopoulou A, Shortman K, Georgopoulos K. Cell-autonomous defects in dendritic cell populations of Ikaros mutant mice point to a developmental relationship with the lymphoid lineage. Immunity. 1997;7:483–492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Allman D, Dalod M, Asselin-Paturel C, et al. Ikaros is required for plasmacytoid dendritic cell differentiation. Blood. 2006;108:4025–4034. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-007757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Iwakoshi NN, Pypaert M, Glimcher LH. The transcription factor XBP-1 is essential for the development and survival of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2267–2275. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Auffray C, Fogg DK, Narni-Mancinelli E, et al. CX3CR1+ CD115+ CD135+ common macrophage/DC precursors and the role of CX3CR1 in their response to inflammation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:595–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]