Abstract

The persistent inflammatory response induced by a severe burn increases patient susceptibility to infections and sepsis, potentially leading to multi-organ failure and death. In order to use murine models to develop interventions that modulate the post-burn inflammatory response, the response in mice and the similarities to the human response must first be determined. Here we present the temporal serum cytokine expression profiles in burned in comparison to sham mice and human burn patients. Male C57BL/6 mice were randomized to control (n=47) or subjected to a 35% TBSA scald burn (n=89). Mice were sacrificed 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 48 hours and 7, 10, and 14 days post-burn; cytokines were measured by multi-plex array. Following the burn injury, IL-6, IL-1β, KC, G-CSF, TNF, IL-17, MIP-1α, RANTES, and GM-CSF were increased, p<0.05. IL-2, IL-3, and IL-5 were decreased, p<0.05. IL-10, IFN-γ, and IL-12p70 were expressed in a biphasic manner, p<0.05. This temporal cytokine expression pattern elucidates the pathogenesis of the inflammatory response in burned mice. Expression of 11 cytokines were similar in mice and children, returning to lowest levels by post-burn day 14, confirming the utility of the burned mouse model for development of therapeutic interventions to attenuate the post-burn inflammatory response.

Introduction

Following a severe burn injury, the systemic inflammatory response encompasses the release of large quantities of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), or tumor necrosis factor (TNF) [1–4]. Anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-4 (IL-4), or interleukin-10 (IL-10), are then released in an attempt to counter-regulate the effects of the pro-inflammatory cytokines [4]. Perturbations of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine expression result in altered immune function and protein metabolism, potentially leading to compromised structure or function of the immune system, liver, skin, or muscle [3;5–8]. In addition, hypermetabolism leads to futile protein utilization resulting in induction of a dynamic hypercatabolic state concurrent with altered cytokine expression [3;8]. Because the changes in cytokine levels occur immediately following burn and prior to the changes in metabolism [9], it may be possible to modulate the hypermetabolic response following burn by altering the cytokine cascade.

We have recently shown that a burn causes a distinct inflammatory cytokine expression profile in severely burned patients [9] and that the cytokine profile at the time of admission can predict which burned patients will develop infectious complications and sepsis during the hospital course [10]. Although these studies enhance our understanding of the post-burn inflammatory response and allow prediction of patient outcome, effective therapies for altering patient outcome do not exist. In order to develop new drugs or interventions that will modulate post-burn hypermetabolism and hyperinflammation, genetically modified mice with either altered protein expression (knock-out or enhanced protein production) or immune-compromisation (nude or scid) may be used. Therefore characterization of the murine inflammatory response to burn is essential to not only allow modulation of the response, but also to allow comparison to the human response to determine the appropriateness of using mice to study the human post-burn response. Here we present expression profiles for 17 cytokines in burned mice. Comparison of post burn cytokine expression of 11 cytokines in mice and children is included to demonstrate the utility of the burned mouse model in studying the human response to burn.

Materials and Methods

Male mice (C57BL/6), 6 to 8 weeks old, were allowed to acclimate for one week prior to the beginning of the experiment. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Texas Medical Branch Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals.

A full-thickness scald burn was induced using the method described by Toliver-Kinsky [11]. In brief, the mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane in air, the dorsal and lateral surfaces were shaved with clippers, and 1 ml of normal saline was injected subcutaneously along the spinal column to protect the spinal cord during the burn. The mice were placed into a mold exposing 35% of the total body surface area (TBSA), which was then immersed in 97°C water for 10 seconds. Animals were resuscitated by intraperitoneal administration of 2 mL of lactated Ringers solution immediately after the burn. Buprenorphine was administered once subcutaneously for pain at the same time. Mice were then housed singly in cages in our institutional animal care facility. The unburned sham animals receive the same treatment excluding the scald burn. Eight to eleven animals were burned per time point; 47 sham mice were included for comparison. Animals were sacrificed by decapitation under isoflurane anesthesia 3, 6, 9, 12, 24, 48 hours or 7, 10, or 14 days following the burn injury. Blood was collected and the serum was separated by centrifugation and stored at −70°C until analysis. The mouse Bio-Plex suspension array (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) was used to measure 18 cytokines: IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-17, IFN-γ, TNF, MIP-α, KC, RANTES, G-CSF, and GM-CSF. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol as previously published [9;10;12].

Statistical analysis was performed by comparing all burn values to the sham values using Kruskal-Wallis One Way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s Method for multiple comparisons versus a control group using SigmaStat 3.11 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Data are expressed as means±SEM. Significance was accepted at p<0.05.

Expression profiles for 11 cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, GM-CSF, IFN-γ, TNF, IL-5, IL-12p70, IL-17, and G-CSF) in pediatric burn patients are included for comparison to the mouse cytokine profiles. The full data set has been published previously [9], but only the cytokines that are the same as those detected with the mouse panel are included here for presentation purposes. Time periods for cytokine profiles in these patients included the following post burn days: 0–3 (average 2), 4–7 (avg. 5.5), and 8–14 (avg. 10.5).

Results

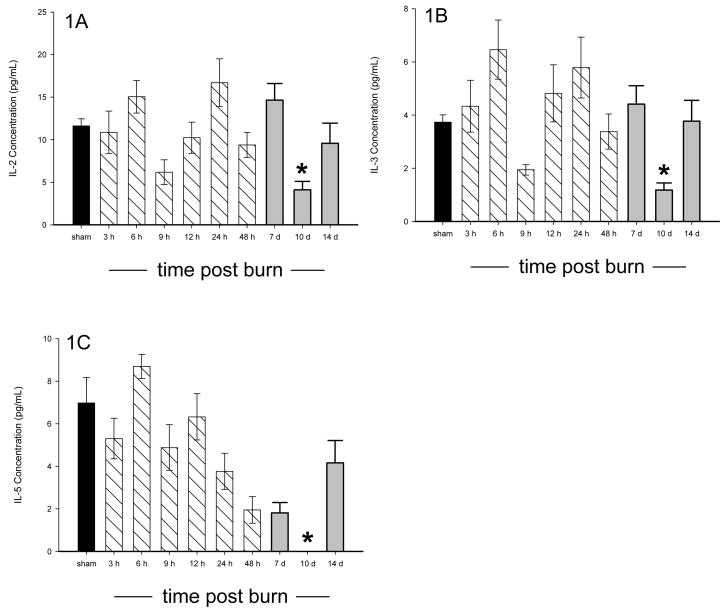

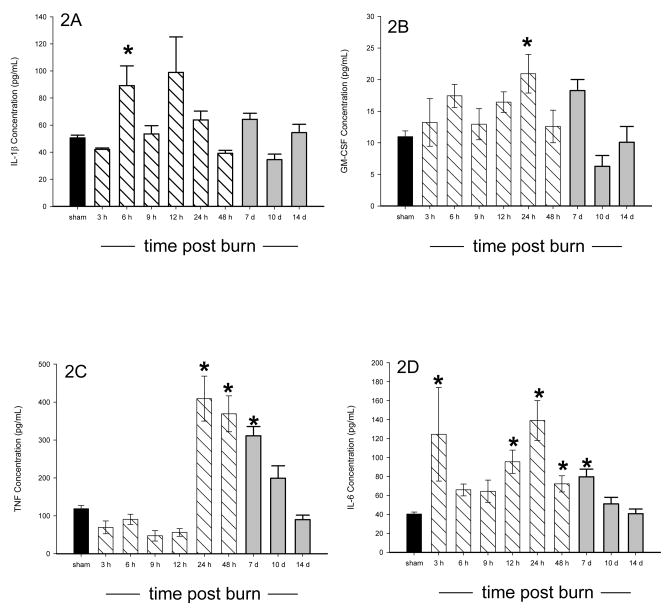

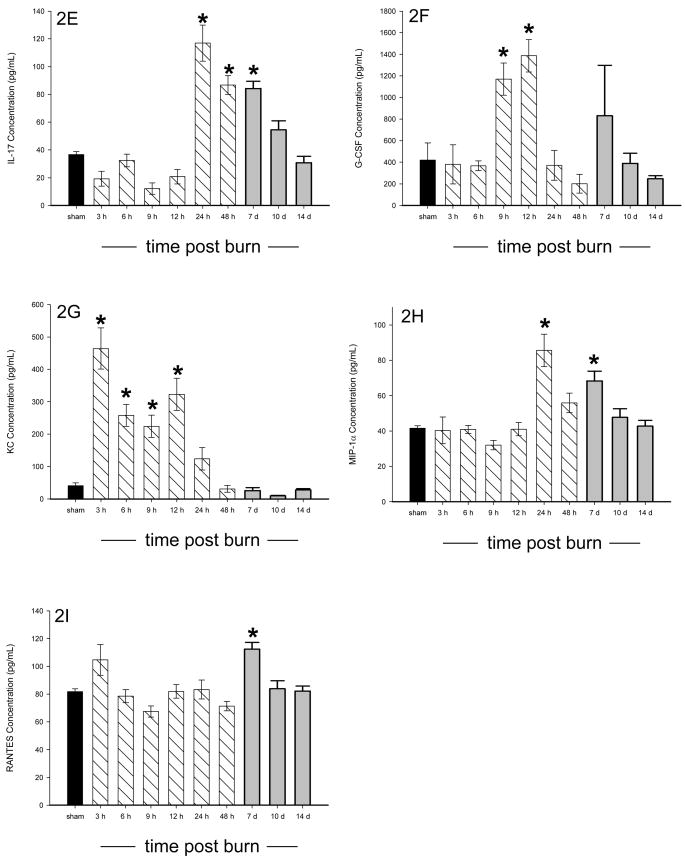

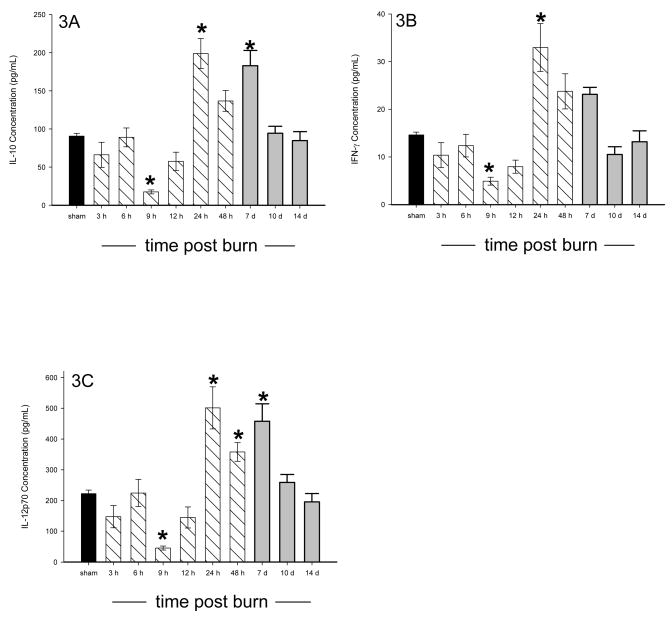

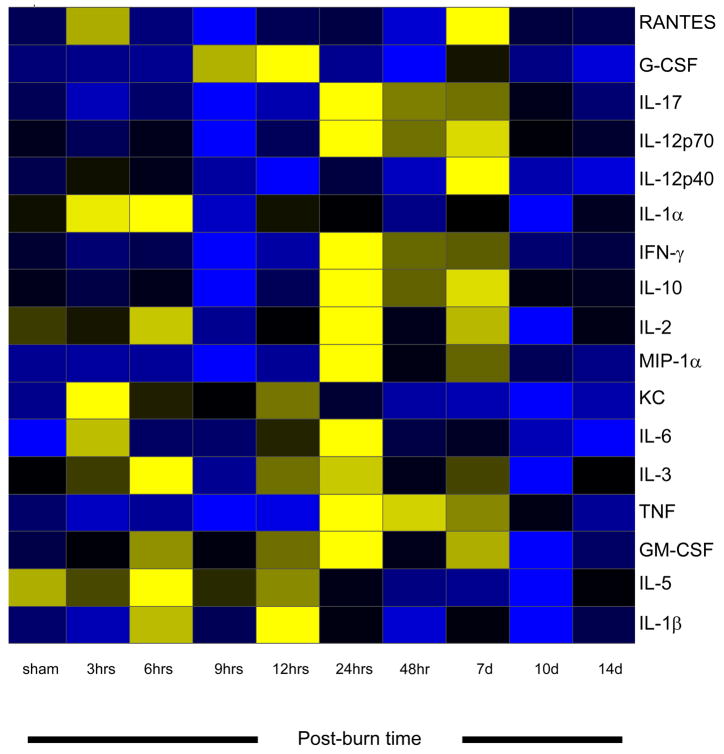

All of the animals survived the burn injury. Of the 18 cytokines measured, 15 were significantly altered in burned mice as compared to sham mice, p<0.05, and all cytokines returned to normal (sham) concentrations by 14 days post burn. Three cytokines (IL-2, IL-3, and IL-5) were significantly decreased in burned mice as compared to sham animals 10 days after burn, p<0.05 (Figure 1A–C). Significant elevations were found in IL-1β, GM-CSF, TNF, IL-6, IL-17, G-CSF, KC, MIP-1α, and RANTES following burn injury, p<0.05 (Figure 2A–I). Biphasic modulation of three immuno-modulatory cytokines (IL-10, IFN-γ, and IL-12p70) occurred in the burned mice with significant decreases at 9 hours post burn followed by significant elevations beginning at 24 hours and returning to normal by 10 days post burn, p<0.05 (Figure 3A–C). No difference in expression between burn and sham mice was detected for IL-1α and IL-12p40 while IL-4 was below the detection limit. A heatmap depicting the changes in the cytokine profile over time following the burn shows that expression returns to normal by 14 days post burn (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

A–D: Serum IL-2 (A), IL-3 (B), and IL-5 (C) were all significantly depressed in burn versus sham mice at 10 days post burn. * significant difference between burn and sham, p<0.05. Data presented as mean±SEM. A dark bar was used for sham data, hatched bars were used for 3 hours – 48 hours, and grey bars were used for 7, 10, and 14 days.

Figure 2.

A–I: Serum IL-1β (A), GM-CSF (B), TNF (C), IL-6 (D), IL-17 (E), G-CSF (F), KC (G), MIP-1α (H), and RANTES (I) were all significantly elevated during a minimum of at least one time point following burn. * significant difference between burn and sham, p<0.05. Data presented as mean±SEM. A dark bar was used for sham data, hatched bars were used for 3 hours – 48 hours, and grey bars were used for 7, 10, and 14 days.

Figure 3.

A–C: Serum IL-10 (A), IFN- γ (B), and IL-12p70 (C) were significantly decreased prior to 24 hours following burn before increasing at 24 hours or later following burn. * significant difference between burn and sham, p<0.05. Data presented as mean±SEM. A dark bar was used for sham data, hatched bars were used for 3 hours – 48 hours, and grey bars were used for 7, 10, and 14 days.

Figure 4.

Heat map comparing sham and burn mouse serum cytokine expression profiles. Hours (hrs) and days (d) are post burn times. Cytokines are grouped as pro-inflammatory or immuno-modulatory. Values are Log10 (average cytokine concentration, pg/ml), with blue indicating lowest levels, yellow indicating highest levels, and black indicating median levels.

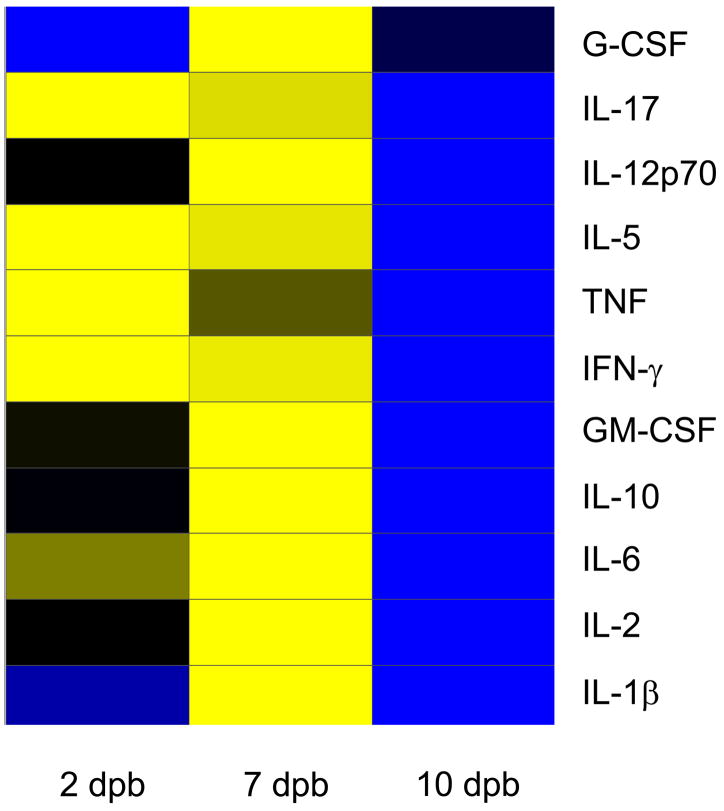

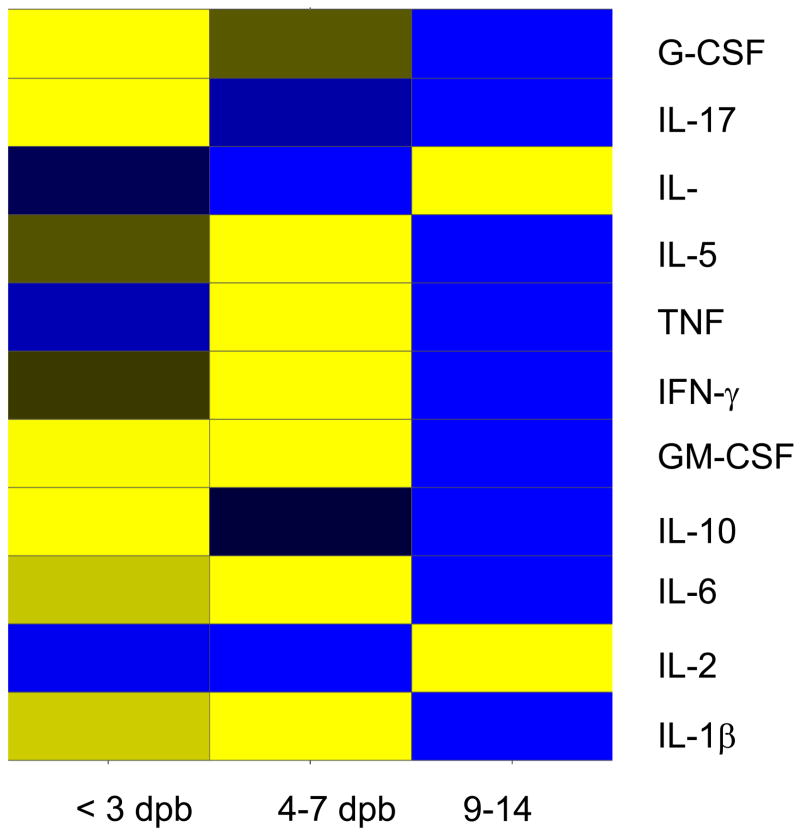

Comparison of the cytokine profiles for the eleven cytokines that are included in both the mouse and human Bio-plex assay kits shows commonalities in the inflammatory response following burn (Figure 5a Murine, 5b Pediatric). Cytokines with similar post-burn temporal expression patterns between the two species included: IL-6, IL-10, IL-17, IL-1β, IL-5, TNF, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF. Three cytokines, however, had distinctly divergent expression patterns: IL-2, G-CSF, and IL-12p70.

Figure 5.

A Murine –B Pediatric: Heat map comparing cytokine expression profiles following burn in mice (A: Murine) as compared to children (B: Pediatric). Time periods were similar in each species [days post burn (DPB)]. Values are Log10 (average cytokine concentration, pg/ml), with blue indicating lowest levels, yellow indicating highest levels, and black indicating median levels.

Discussion

The systemic inflammatory response after a severe burn injury induces the hypermetabolic response, thereby activating protein degradation and catabolism [13]. This uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory mediators also exacerbates protein wasting and organ dysfunction [14;15]. Breakdown of organ function increases the incidence of infection and sepsis, ultimately resulting in multi organ failure and death [16;17]. This circulus vitiosus is poorly understood and has proven difficult to break; therapeutic agents that alter the post burn systemic inflammatory response, hypermetabolism, or organ dysfunction have yet to be brought into the clinical arena. Although we have shown the temporal cytokine expression pattern for pediatric burn patients [9], little is known about the duration or magnitude of the cytokine cascade after a severe thermal injury in the animal models that are used to study burn pathophysiology.

The widespread availability of knock-out, over-expressing, severe combined immunodeficiency (scid), and nude mice will enable dissection of the roles that individual cytokines play in determining post burn survival makes the murine burn model useful. However, the inflammatory response to burn is incomplete and not well characterized in mice. Additionally, there is a dearth of information of plasma or serum cytokine expression in burned, non-infected rodents; following a burn injury in mice, the typical cytokines that are measured are IL-1, IL-6, or TNF, and the literature is replete with conflicting evidence regarding the expression of these factors. In one study, serum IL-6 and IL-1β were elevated 24 hours following burn in mice [18]. A second study, however, found that at post burn days 1 and 7 TNFα, IL-6, and IL-10 were not detected in burned or sham mice [19]. We, on the other hand, detected all three cytokines on post burn days 1 and 7. One major difference between these 2 studies and ours is the burn size; these studies were performed on mice burned over 25% [19], 30% [18], and here 35% of TBSA. Variation of the inflammatory response with burn size has been reported in patients [20], thus we might attribute the apparent discrepancy in the data to these differences in burn size. Additional studies performed on rats burned over 20% of TBSA confirm the trends that we present for mice. Elevation of IL-1, TNF, and IL-6 concentrations was reported at time points less than 72 hours following burn [21]; we found similar elevations in burned mice. Gauglitz et al showed elevation of IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 within hours of burn injury in rats burned over 60% of TBSA, but no change in TNF [22]. Many of the other cytokines that we measured, however, are not typically measured in burned mice and so their modulation following burn has not been previously published.

The aims of the present study, therefore, were two-fold 1) to measure serum cytokine expression in burned mice for comparison to normal non-burned, non-infected mice; and 2) to compare the burn mouse cytokine profile to the pediatric burn cytokine profile at similar post burn time periods. Fifteen of the eighteen cytokines were modulated in response to burn in mice; significant elevations were found in IL-1β, GM-CSF, TNF, IL-6, IL-17, G-CSF, KC, MIP-1α, and RANTES. Interleukins 2, 3, 4, and 5 were significantly decreased 10 days post burn. Three immuno-modulatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-12p70, and IFN-γ) exhibited biphasic modulation. No significant alterations were found in IL-1α or IL-12p40. Many of the cytokines that undergo altered expression following a burn injury are important modulators of immune cell proliferation, differentiation, and clonal expansion of lymphocyte sub-populations. These cytokines also attract immune cells to the site of injury. The systemic effects of the massive upregulation of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, however, may result in non-specific inflammation instead of a carefully orchestrated systemic inflammatory response where the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines modulate each other. We found that the concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-2, IL-3, IL-5, IL-6, IL-12p70, IL-17, GM-CSF, KC, MIP-1α, RANTES, and TNF are significantly different following a severe burn in mice, but the same is true for anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, G-CSF, and IFN-γ at the same post burn time points. Our study shows, for the first time, the simultaneous involvement of a plethora of cytokines in the murine post burn response. We also demonstrate for the first time that the inflammatory response to burn as characterized by cytokine expression in humans and mice is similar for 8 of 11 cytokines. Factors such as species differences and burn size or severity variation can account for the variation between the profiles of the post burn mouse and human inflammatory response. We also show that the magnitude and duration of the inflammatory response to burn in mice is similar to that in humans.

While the alterations in cytokine concentrations are dramatic, we cannot interpret this data to address whether these mediators are induced directly by burn, if they are induced as secondary mediators, or whether they are merely markers of systemic inflammation. Regardless of the cause of this inflammatory response, the aftermath is still the same – an exaggerated inflammatory response that can be detrimental to the burn patient’s health [7]. This persistent inflammatory response results in suppression of host immunity that predisposes patients to additional infections or sepsis and subsequent development of multi-organ failure and death. We propose that it is not the expression of an individual cytokine that indicates clinical outcome, but rather the expression profile showing the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines that may be indicative of clinical outcome. Through the development of a mouse model with a similar inflammatory response as is seen in humans, we can now test our hypothesis that an alteration of cytokine expression early after burn may improve outcome. By establishing the cytokine expression profile we now can compare the cytokine profiles of burned mice to burned mice receiving drug treatment.

In the present study we showed the expression profile of 17 cytokines in burned mice as compared to sham mice as well as the similarities between the murine and human post burn inflammatory responses. By determining the cytokine expression pattern in burned mice, we now have a tool to study whether differences in cytokine expression are associated with outcomes and to test our hypothesis that the elevations in serum cytokine levels during the first week post burn offer a potential window of opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM60338 and Shriners Hospital for Children grants 8740, 8660 and 8640. C.C. Finnerty was supported by NIH grant 5 T32 GM08256. The authors thank Amanda Sheaffer for her technical assistance.

This study was supported by NIH grant GM60338-05, and grant #8660 from the Shriners Hospital for Children. CC Finnerty was supported by NIH grant 5 T32 GM08256-15.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Fassbender K, Pargger H, Muller W, Zimmerli W. Interleukin-6 and acute-phase protein concentrations in surgical intensive care unit patients: diagnostic signs in nosocomial infection. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1175–1180. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199308000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Butler J, Chong GL, Baigrie RJ, Pillai R, Westaby S, Rocker GM. Cytokine responses to cardiopulmonary bypass with membrane and bubble oxygenation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;53:833–838. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(92)91446-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Debandt JP, Cholletmartin S, Hernvann A, Lioret N, Duroure LD, Lim SK, Vaubourdolle M, Guechot J, Saizy R, Giboudeau J, Cynober L. Cytokine Response to Burn Injury - Relationship with Protein-Metabolism. Journal of Trauma-Injury Infection and Critical Care. 1994;36:624–628. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199405000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Despond O, Proulx F, Carcillo JA, Lacroix J. Pediatric sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:247–253. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200106000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwacha MG. Macrophages and post-burn immune dysfunction. Burns. 2003;29:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00187-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vindenes HA, Bjerknes R. Impaired actin polymerization and depolymerization in neutrophils from patients with thermal injury. Burns. 1997;23:131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(96)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herndon DN. Total Burn Care. W.B. Saunders; London: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wray CJ, Mammen JM, Hasselgren PO. Catabolic response to stress and potential benefits of nutrition support. Nutrition. 2002;18:971–977. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(02)00985-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Przkora R, Pereira CT, Oliveira HM, Queiroz DM, Rocha AM, Jeschke MG. Cytokine expression profile over time in severely burned pediatric patients. Shock. 2006;26:13–19. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000223120.26394.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Chinkes DL, Jeschke MG. Serum cytokine differences in severely burned children with and without sepsis. Shock. 2007;27:4–9. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235138.20775.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toliver-Kinsky TE, Cui W, Murphey ED, Lin C, Sherwood ER. Enhancement of dendritic cell production by fms-like tyrosine kinase-3 ligand increases the resistance of mice to a burn wound infection. J Immunol. 2005;174:404–410. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finnerty CC, Herndon DN, Jeschke MG. Inhalation injury in severely burned children does not augment the systemic inflammatory response. Crit Care. 2007;11:R22. doi: 10.1186/cc5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeschke M, Chinkes D, Finnerty CC, Kulp MS, Suman OE, Norbury WB, Branski LK, Gauglitz GG, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. The pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Annals of Surgery. 2008 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeh FL, Shen HD, Fang RH. Deficient transforming growth factor beta and interleukin-10 responses contribute to the septic death of burned patients. Burns. 2002;28:631–637. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeschke MG, Einspanier R, Klein D, Jauch KW. Insulin attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to thermal trauma. Mol Med. 2002;8:443–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rennie MJ. Muscle protein turnover and the wasting due to injury and disease. Br Med Bull. 1985;41:257–264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnold J, Campbell IT, Samuels TA, Devlin JC, Green CJ, Hipkin LJ, MacDonald IA, Scrimgeour CM, Smith K, Rennie MJ. Increased whole body protein breakdown predominates over increased whole body protein synthesis in multiple organ failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 1993;84:655–661. doi: 10.1042/cs0840655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ipaktchi K, Mattar A, Niederbichler AD, Hoesel LM, Vollmannshauser S, Hemmila MR, Su GL, Remick DG, Wang SC, Arbabi S. Attenuating burn wound inflammatory signaling reduces systemic inflammation and acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2006;177:8065–8071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.8065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy TJ, Paterson HM, Kriynovich S, Zang Y, Kurt-Jones EA, Mannick JA, Lederer JA. Linking the “two-hit” response following injury to enhanced TLR4 reactivity. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:16–23. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0704382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeschke MG, Mlcak RP, Finnerty CC, Norbury WB, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, Herndon DN. Burn size determines the inflammatory and hypermetabolic response. Crit Care. 2007;11:R90. doi: 10.1186/cc6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kataranovski M, Magic Z, Pejnovic N. Early inflammatory cytokine and acute phase protein response under the stress of thermal injury in rats. Physiol Res. 1999;48:473–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauglitz GG, Song J, Herndon DN, Finnerty CC, Boehning DF, Barral JM, Jeschke MG. Characterization of the inflammatory response during acute and postacute phases after severe burn. Shock. 2008 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31816e3373. April 2008 Epub ahead of print: PMID: 18391855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]