Introduction

This article describes three periods in Brazil's modern history when governmental action was (or was not) taken against smallpox: first, when smallpox control became a priority in the Brazilian sanitary agenda from the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century; second, when it was rendered politically invisible during decades when greater attention was given to yellow fever and malaria control; third, when it reappeared at the centre of Brazilian health policy in the 1960s until its eventual eradication in 1973. Smallpox control in the latter two periods is suffused with paradox. For example, evidence suggests that the nearly fifty-year absence or lack of policies and agencies to deal with smallpox actually favoured the mobilization of local, national and international resources once the eradication programme was launched in 1966; these new approaches were accelerated from 1969 until the completion of eradication in 1973. Equally paradoxical, it was during the specific context of the military regime after 1964 that the Brazilian health system developed the capacity to mobilize existing but dispersed resources and flexibly to innovate, incorporate, and adapt new policies. Another important element in this period was institutional learning based on other vertical programmes such as the malaria eradication campaign. Although the Brazilian smallpox eradication programme was constrained by international agencies and by bilateral co-operation with the United States, the period after 1964 offered opportunities for the realization of a new and wide-ranging national health capacity including the creation of a national system of epidemiological surveillance and a national childhood immunization programme. It also saw the empowerment of young physicians who would later come to occupy key positions in Brazilian public health and in international health organizations.

The aim of this article is to review the long history of smallpox eradication in Brazil. This history is not restricted to the institutional landmarks defined by the creation of the Smallpox Eradication Campaign (Campanha de Erradicação da Varíola or CEV) in August 1966 that culminated in the international certification of eradication in August 1973. Rather, the history of vaccination in Brazil dates back to the early nineteenth century when smallpox control through vaccination was always a priority on the country's sanitary agenda. Smallpox control maintained its primacy into the 1910s, after which yellow fever supplanted it as the infectious disease of main concern in the 1920s and 1930s. From the mid-1940s malaria control became the priority, followed in the 1950s by a greater emphasis on malaria eradication, in accordance with the international health agenda. Thus during nearly fifty years—from approximately the mid-1910s to the mid-1960s—smallpox control disappeared from Brazil's radar as a health policy priority, even though the disease, especially in its predominantly minor form, continued to be acknowledged.

This disappearance or obscuring of smallpox control in Brazil contrasted with a build-up of pressures inside the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) and the World Health Organization (WHO) for a global smallpox eradication campaign, which was formally approved by the World Health Assembly in 1959. At that time, Brazil was the only South American country that did not have a systematic national vaccination programme—this despite the fact that Brazil registered the majority of smallpox cases in the region. After 1959 the Brazilian government shifted gear again and began to move in the same direction as other countries. The context for this shift was one of notable changes in Brazil's inter-American relations as well as changes in the role of the United States in the region; these changes together led to a political and economic crisis in 1964 that culminated in a military coup. Subsequently, the country established its eradication programme in 1966 as part of the WHO's Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme.

In this article the history of smallpox eradication in Brazil is understood as a long chapter with a distinct periodization that constitutes a key period in the contemporary history of international health. Very few historians and social scientists have analysed the participation of Brazil in this history, which is most often presented from the point of view of national and international agencies and their protagonists.1 The perspective adopted here is that the relations between national health policies in developing countries and international policies are complex and not formulaically defined. As various authors have demonstrated, if there are asymmetries in the relations between international agencies, governments, public health communities and individual personalities in the field of international health, these differences do not necessarily define the format and the development of a national health programme.2 The analysis should consider the context of national-international relations, especially when these intersections produce dynamic arenas where national players and institutions, transnational professionals, and international agencies interact, circulate, shape and transform one another.

The Rise and Apogee of smallpox in the Brazilian Sanitary Agenda

From the middle of the nineteenth century until the first decades of the twentieth, smallpox and yellow fever were considered the main public health problems in Brazil.3 Although there is evidence for the presence of smallpox since the sixteenth century, only at the end of the empire period (1822–89) and during the first republican decade (1890s) did outbreaks make it clear that more effective public responses were needed. Those outbreaks often paralysed the city of Rio de Janeiro, at the time both the national capital and main port of the country, through which raw agricultural exports and imported manufactured goods moved. Smallpox also affected the flow of immigrants which increased rapidly after the abolition of slavery in 1888.4

Jennerian vaccine was introduced to Brazil in 1804 when Portuguese traders who had settled in Bahia financed the trip of seven slaves to Europe where they were inoculated with the “vaccinal pus”. This was passed from arm to arm during their return to Brazil and to others once they arrived there.5 In 1808 when the king of Portugal and the court fled Lisbon and transferred to Brazil at the time of the Napoleonic invasion, important sanitary measures began to be implemented. The economic, social and political conditions of the country and in particular of Rio de Janeiro, the new kingdom's capital, were considerably altered by the presence of the Portuguese court, which was composed of 15,000 people. A decree that opened Brazil to international commerce in 1808 resulted in closer commercial relations with Great Britain, but this required increased sanitation in the ports. A Royal Vaccination Commission (Junta Vacínica da Corte) was created in 1811 with authority over smallpox vaccination, one of a series of regulations instituting medical, curative and preventive measures to combat diseases.6 The independence of Brazil from Portugal in 1822, the imperial constitution of 1824, and subsequent legislation maintained the decentralized character of public health measures that had been adopted in 1808. This reinforced the power of landowners over their slaves, but it also motivated the creation of local-level institutions committed to smallpox vaccination.7

The first law making vaccination compulsory in the city of Rio de Janeiro dates to 1832. However, the law was ineffective; despite a limited provision of health services and vaccination to the country's capital and to some of the coastal cities in the north-east and south, it produced no positive results. In truth, sanitary authorities faced great difficulties in implementing effective and permanent measures against smallpox in such a huge country, which had large inland areas where a sparse population, including the indigenes, had no contact with public services. Because of the administrative, financial and political weakness of local governments, the various administrations failed to obey the laws, and vaccination was limited. For the general or free population the recurrent pattern until the 1840s was that the imperial and provincial governments provided only emergency responses to smallpox outbreaks; these responses were usually demobilized once the epidemic disappeared.8 On the other hand, slaves seem to have been the most likely recipients of smallpox vaccination until the middle of the 1850s.9

The 1820s and 1830s witnessed the creation of Brazil's first medical schools in Bahia and Rio de Janeiro and the emergence of medical societies.10 This motivated a debate among the medical community about procedures of variolation, animal and Jennerian vaccination, revaccination, and about the most effective additional measures to be taken to combat the disease, such as isolation, hospitalization and disinfection.11 The frequent yellow fever outbreaks, especially in 1849–50, and smallpox outbreaks in 1834, 1836 and 1844, as well as a political re-centralization of the imperial administration after 1840, favoured the creation of more permanent structures. In 1846 the Imperial Vaccination Institute (Instituto Vacínico do Império) was established; it was incorporated, together with the health service of the ports, into the Public Hygiene Central Command (Junta Central de Higiene Pública) in 1850. This was Brazil's first attempt to standardize and nationalize its sanitary administration. The centralization of the sanitary services was followed by legislation that aimed to make compulsory vaccination more efficient, and by efforts to improve the quality of the vaccine as well as the state's capacity to isolate smallpox cases. This structure continued with little change until the end of the empire in 1889.12

The main epidemic diseases in Rio de Janeiro were yellow fever and smallpox, which made the imperial capital unsafe for passengers and freighters. After a decrease in epidemics in the 1860s, the city saw almost annual outbreaks of smallpox with high rates of mortality during the 1870s.13 The 1887 epidemic, in particular, devastated Rio and stimulated the most important innovation at the end of the empire:14 animal vaccine production was at last begun in 1887. This step was one of several philanthropic initiatives by Baron de Pedro Afonso to mobilize the imperial court and the government against smallpox. During the beginning of the republican period, Pedro Afonso assumed responsibility for the new Municipal Vaccination Institute (Instituto Vacínico Municipal) in Rio de Janeiro.15

The Republic was inaugurated in November 1889. Its aim was to modernize the country and integrate it with the so-called civilized world. International commerce and the country's economic and social life had been too often paralysed by yellow fever and smallpox outbreaks. The first effective attempt to change the sanitary status quo and enhance the negative international image of Brazil and its capital involved large-scale urban reform between 1903 and 1906, inspired by Baron Haussmann's similar efforts undertaken a few decades earlier in Paris. This reform was followed by extensive campaigns against yellow fever, smallpox and bubonic plague during the presidency of Rodrigues Alves (1902–6).16 These campaigns were led by the physician Oswaldo Cruz, who was Director of Public Health from 1903 to 1909. From 1902 Cruz had also been the Director of the Federal Serum-Therapeutic Institute (Instituto Soroterápico Federal), created in 1900 to produce sera and vaccines; this establishment was renamed the Oswaldo Cruz Institute (Instituto Oswaldo Cruz) in 1907.17 Under Cruz's direction the Institute became an important centre of sera and vaccine production and of research in the fields of tropical medicine and microbiology.18

In 1904 Rio de Janeiro, the federal capital, registered almost 7,000 smallpox cases. As the combat against smallpox depended solely on vaccination, Oswaldo Cruz presented the Brazilian Congress with a proposal to re-launch compulsory vaccination and re-vaccination for the whole population—this was an existing legal obligation that until then had never been obeyed. The new law contained severe penalties, including fines for non-compliance and the requirement that a vaccination certificate be furnished as a condition for public education, and employment in the public services, as well as for marriage and travel. In addition, the new law authorized sanitary officials to enter private residences for the purpose of vaccination.19

Passage of the compulsory vaccination law in October 1904 was preceded by intense debate and strong opposition. Publication of the proposed law in the newspapers—it was widely known as called the “Torture Code”—set off a popular revolt that brought together a variety of groups with very different motivations and interests: anti-vaccinationists; military and civil monarchists (who saw the possibility of riding the vaccination revolt to re-install the empire); positivists who reacted against any sort of government compulsion and intervention in the practices of cure; trade unionists who fought for better salaries and against the high cost of living; and military and political elites who opposed the president. In addition, other sectors joined the revolt, especially the urban poor who had been most affected by earlier reforms that had destroyed a great number of their dwellings deemed unhealthy; these persons, who had been expelled from the centre of the city, resisted further measures to make it sanitized and beautiful at their expense.20 Some authors suggest that there was an element of religious resistance to vaccination in Rio because of continued popular support for variolation, which was associated with divinities worshipped by the groups of African descent that made up a considerable part of the city's poor.21 In any case, a violent episode known as “The Vaccine Revolt” (Revolta da Vacina) paralysed Rio de Janeiro from 10 to 16 November 1904, during which time a state of siege was declared by the government, which finally succeeded in controlling the city by acts of severe repression.22

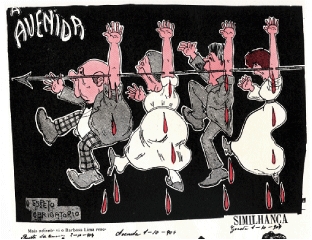

Figure 1.

‘War against the compulsory vaccination!’, published 29 October 1904, Revista O Malho, reproduced in Edgard de Cerqueira Falcão, Oswaldo Cruz monumenta histórica. A incompreensão de uma época. Oswaldo Cruz e a caricatura, vol. VI, t. I., São Paulo, s.n., 1971 (Coleção Brasiliensia Documenta), p. CXXIX.

Once the most turbulent period was over, smallpox vaccination continued to be implemented and was slowly incorporated into the daily life of the capital and in the other main cities in the country. Mortality swiftly declined, reaching almost zero in 1906. The vaccination campaigns initiated by Oswaldo Cruz in 1904 had an important role in the decrease of smallpox cases for two subsequent decades, although a few important outbreaks interrupted the trend. For example, a new epidemic paralysed the capital in 1908, only four years after the Vaccine Revolt, causing an unusually high mortality rate of 1,000 per 100,000 inhabitants; a total of 9,900 cases was registered, surpassing the epidemic outbreaks of 1887 and 1891.23 Nevertheless, there are no records of popular organized resistance to vaccination in 1908 nor in the outbreaks of 1914 nor in 1926, when the last epidemic struck Rio with over 4,140 reported smallpox cases.24

The sanitation of the country's capital directed by Oswaldo Cruz, who became a national hero, affected public opinion, which thereafter looked favourably on compulsory, state-directed vaccination. On the other hand, the dissatisfaction, interests and demands that were expressed during the 1904 revolt, many of which were contradictory, and where anti-vaccination protest was one of the elements, were no longer politically articulated. Appeals to the law courts became less frequent after the National Supreme Court reaffirmed that restraints on personal freedom for the sake of public health were justified, as long as they were prescribed by law and not by regulation.25 In 1926, newspapers in the capital criticized the fact that a federal judge in the state of Maranhão in north-east Brazil still granted habeas corpus to release a group of vaccination objectors on the grounds that they were allegedly constrained by the state's health director.26

Figure 2.

‘The compulsory lancet’, published in October 1904, Revista da Semana, Rio de Janeiro, reproduced in Edgard de Cerqueira Falcão, Oswaldo Cruz monumenta histórica. A incompreensão de uma época. Oswaldo Cruz e a caricatura, vol. VI, t. I, São Paulo, s.n., 1971 (Coleção Brasiliensia Documenta), p. CVIII.

By 1930 the number of smallpox cases in the capital reached zero, and the number remained very low throughout the decade, despite occasional outbreaks in several cities elsewhere in the country. From 1940 the predominant variety became the Variola minor or alastrim, the less severe form of the disease. Whereas smallpox mortality in Rio de Janeiro between 1926 and 1930 had amounted to 53 per cent of the cases, between 1931 and 1935 this decreased to 4.1 per cent, and thereafter to less than 3 per cent.27 Oswaldo Cruz's successful campaigns produced a basic social consensus about vaccination's importance as well as the necessity for compulsion. Nevertheless, the decrease in the number of cases and in the fatality rate, together with the financial fragility of the majority of the Brazilian states, made it difficult to maintain national and public policies of smallpox control, which increasingly depended on local and philanthropic initiatives.

The Decline and Disappearance of Smallpox from the Brazilian Agenda

From the middle of the 1910s public health physicians and directors were concerned with fighting other endemic diseases, particularly malaria, ancylostomiasis and worm infestation, and American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease). In the nationalist context of the First World War a political movement emerged in Brazil that supported sanitation and public health reform. This movement aimed at the “redemption” and incorporation of the rural sick population by means of wider actions to be taken by the national public health services.28 Up to that moment public health services had been restricted to the capital and coastal cities; public health activity was also limited by the federalist system adopted by the republican constitution of 1891. Further, during the 1920s and 1930s, in co-ordination with the International Health Division (IHD) of the Rockefeller Foundation, large investments had been made to combat yellow fever, which was eliminated from Rio de Janeiro by Oswaldo Cruz but continued to be endemic in several areas of the country.29 Leprosy was another target of great concern, and tuberculosis continued to be a significant health problem in urban areas. In 1919, as a result of a political movement for Brazil's health reform and sanitation, the National Congress approved the creation of the National Department for Public Health (Departamento Nacional de Saúde Pública) with wide assignments and priorities in rural health, tuberculosis, leprosy and what were then termed venereal diseases.30

While smallpox (together with yellow fever) had been the target of Brazilian public health actions during the first decade of the twentieth century, by the end of the oligarchic republic period (1889–1930) it was no longer a federal government priority. It was not included in any specific institution or policy, and in practical terms it had been excluded from the public health agenda. During the Getúlio Vargas government (1930–45), a period of strong political and administrative centralization that deepened into an outright dictatorship after 1937, there was an understanding that vaccine production and vaccination should remain a municipal and state government responsibility. The campaign against smallpox was not included on the agenda of the new Ministry of Education and Health, established in 1930, nor was it recognized in 1941 when national services were set up to fight those diseases considered most threatening in the country.31 Smallpox was left out of the large reforms of federal health institutions in 1937 and 1941.32 By comparison with yellow fever and tuberculosis, little investment was made in the modernization of smallpox vaccine production or in research, and no national system was developed for case reporting and surveillance. In effect, smallpox had disappeared from the country's radar.

Any effort to enlarge vaccination coverage depended entirely on the initiative of state and local governments, which usually had other priorities or lacked technical and financial means to produce or purchase vaccines and to deliver routine vaccination. The federal government co-operated technically and supported the supply of immunizers only in an insufficient and erratic manner.33 The exceptions were the BCG and yellow fever vaccines, which were solely the responsibility of the federal government.34 Although smallpox cases and epidemic outbreaks did occur and the sick were evident, the political invisibility of smallpox meant that it was not included as a topic at the First National Health Conference held in Rio de Janeiro in November 1941 where the country's main health problems and possible solutions were discussed.35

Malaria instead became the centre of attention in Brazilian public health, especially after 1939 with the beginning of the campaign to eradicate Anopheles gambiae in the north-east region directed by Fred L Soper in accordance with the IHD.36 Given Brazil's long experience in research and in prophylaxis against malaria, including the eradication efforts against A. gambiae, as well as the belief that vertical health campaigns were the most appropriate and efficient models, the government created the National Malaria Service (Serviço Nacional de Malária or SNM) in 1941.37 The SNM undertook large campaigns with the intensive use of DDT (dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane) and freely distributed anti-malarial drugs. During its fifteen years of existence (1941–56) the SNM became the largest and most complex Brazilian sanitary service. It established a research centre composed of an internationally recognized community of malariologists who also published a specialized journal.38 When in 1942 Brazil joined the Allies in the Second World War, it signed agreements with the United States government for the creation of an autonomous agency to work on sanitation and health assistance in the areas of strategic minerals and rubber extraction. This Special Public Health Service (Serviço Especial de Saúde Pública or SESP), which dealt also with malaria, was initially directed by North American physicians who were subsequently replaced by Brazilian physicians.39

The political status of smallpox did not change after the fall of Getúlio Vargas in October 1945. The dictatorship was followed by the country's re-democratization and the election of Eurico Dutra (1946–51), followed by an elected second Vargas government from 1951 to 1954. The creation of a Ministry of Health in 1953 and the partial fusion of various national services into the National Department of Rural Endemic Diseases (Departamento Nacional de Endemias Rurais or DNERu) in 1956 reinforced this centralizing tendency. Yet in the legislation creating the DNERu, smallpox was not included on the central government's list, even though the DNERu would go on to have a national reach and to work in areas where smallpox was endemic, especially in rural areas.40 The new department's concern was focused on rural endemic diseases (particularly malaria) that were considered obstacles to the country's economic development; economic development was the government's main issue (particularly during the presidency of Juscelino Kubitschek, 1956–61). The need to build infrastructure for accelerated industrialization, to modernize agriculture and to build a new capital in the geographic centre of Brazil—Brasília—these were the focuses of the president's concern.41

In his first presidential message in 1956, Kubitschek stressed the priority of what he called “mass diseases”—malaria, worm infestation, yaws, trachoma, tuberculosis, syphilis, gastrointestinal and nutritional diseases—all of which he considered “a great burden for the underdeveloped nations”. For the new president the so-called pestilent diseases such as yellow fever, plague and smallpox were under control.42 In the same message Kubitschek indicated his vision of the relation between health and development—a bounded approach that shows his acceptance of the mainstream perspective in favour of eradication.43 He thought that it would be possible to eliminate diseases with insecticides and drugs without having to make changes in political relations or socio-economic conditions. According to Kubitschek:

There is the advantageous coincidence that new therapeutic and prophylactic discoveries have been made that will permit the substantial reduction, or even the elimination, of those diseases that most strongly affect the populations of underdeveloped countries, and these can be applied without regard to problems of economic development or the high costs of a medical-sanitary apparatus.44

Two years later in 1958 the Malaria Eradication Campaign (Campanha de Erradicação da Malaria or CEM) was established. It began with the conversion of Brazil's national malaria control programmes into eradication campaigns in accordance with the recommendations of the Fourteenth Pan American Sanitary Conference (1954) and the Eighth World Health Assembly (1955). Brazil played a key role in the global malaria eradication programme, and achieved a fast reduction in the number of cases after 1947. Nevertheless, the conversion of its organizations into an eradication programme on the model proclaimed by PAHO/WHO was not put into practise until 1965. A significant amount of the Brazilian government's human and financial resources available for public health was consumed by the malaria eradication programme, which also relied on loans from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) from 1958 to 1970, when the programme ended.45 Malaria control and eradication had dominated the Brazilian public health scene during the 1940s and 1950s.

The Return of Smallpox as an Eradicable Disease

Changes in the international and national scenes in the second half of President Juscelino Kubitschek's term led to the reappearance of smallpox on the Brazilian health agenda as well to the decision to eradicate malaria. The proposal of smallpox eradication had been made in PAHO and WHO's resolutions since 1949. In 1959, the resolution of the Twelfth World Health Assembly on the urgency and necessity of a global smallpox eradication programme had an important impact.46 One year earlier, at the Fifteenth Pan American Sanitary Conference, the country had assumed the commitment to participate in the elimination of smallpox from the region.

In his message to Brazil's National Congress at the opening of the legislative year in 1958, Kubitschek indicated that it had become possible to eradicate smallpox. 47 Even though malaria continued to be his main focus, this was the first presidential speech since 1950 to explicitly mention smallpox as one of the country's main sanitary problems and to declare eradication a government goal.48 Kubitschek announced two steps to fight against the recrudescence of smallpox cases which had occurred in Brazil since 1955.49 Firstly, the country's size and dispersed population made mass immunization difficult, because the techniques of vaccine production and conservation did not preserve the immunizer effect for a long period of time. Therefore, with the support of PAHO/WHO, the government would equip the national laboratories for the production of the dried-freeze vaccine. Secondly, the municipal and state governments’ difficulties with routine vaccination campaigns had hitherto produced low vaccination coverage that did not prevent sporadic outbreaks in urban areas. This resulted in a high number of cases (by comparison with other countries in the Americas) and an uncomfortable role for Brazil as an exporter of cases to countries that no longer had endemic smallpox.50 The government's strategy would be to mobilize all federal health organizations to perform mass vaccination in support of state and municipal services.51

There was an intersection of national and international contexts that explain this change. In 1958 the Kubitschek government faced difficulties in financing any health programme because priority had been given to investment in infrastructure for economic development and for transferring the capital to Brasília—a step Kubitschek intended to take before the end of his term. The same year also saw meaningful changes in international relations. Although Brazil was already fully within the United States’ sphere of influence, there had been increasing economic divergences between the two countries since the end of the Second World War. On the one hand, Brazil continued to hope that the United States would make some sort of commitment to allocate resources to alleviate Brazil's suffering and accelerate its economic development. This seemed particularly urgent, given the devastation in other Latin American countries whose chronic economic problems had only worsened since 1945. On the other hand, Washington insisted that economic development was each country's internal responsibility and should be solved by adopting liberal economic policies and by the creation of a friendly environment for investment.52 Public resources from the United States would be concentrated instead on regions that gave priority to combating Communism, especially Europe, and Asia—which was going through an intense decolonization process. The tension between Latin America and the United States reached a critical point when the North American Vice-President Richard Nixon made a series of “good will mission” visits to Latin American countries and faced very strong popular anti-American demonstrations.53

Taking advantage of a favourable conjuncture, on 28 May 1958 Kubitschek sent a letter to President Dwight Eisenhower in which he lamented the degree of deterioration of regional relations and proposed a revision of Pan Americanism. Denominated Pan American Operation (PAO), this new diplomatic initiative proposed that the United States assume a political commitment to eradicate underdevelopment in Latin America by the allocation of public investment, thus contributing to the region's political stability and creating a barrier to Communism.54 Even though no immediate changes occurred, Eisenhower visited Brazil in February 1960 after a bilateral crisis arose in July 1959 when Brazil precipitated a rupture with the International Monetary Fund. There was also a convergence between the Brazilian and North American positions that was expressed in the Act of Bogotá, September 1960, in which specific measures were proposed for the social and economic development of the region, such as the creation of the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB).55

These changes in the North American government's approach to Latin America, which pointedly followed the success of the Cuban Revolution, resulted in the “Alliance for Progress” during John Kennedy's administration. The changes were signalled in the Charter of Punta del Este, a document signed by the member states of the Organization of American States (OAS) at a conference held in Uruguay in August 1961.56 In an appendix to the Charter called the ‘Public Health Decennial Plan of the Alliance for Progress’ reference was made to the eradication of smallpox under the auspices of the United States as part of the social reforms agenda.57

Being under pressure and perceiving an opportunity to obtain resources for the improvement of the country's public health, Brazil begun to integrate the international health agenda and the new inter-American political system. The pressure to eradicate malaria was particularly strong, because of a North American decision that grants could only be used for national eradication programmes, as announced in Eisenhower's “war on malaria” statement in 1958.58 Yet smallpox was not to be neglected: between 1958 and 1961 the DNERu of the Ministry of Health initiated a smallpox vaccination programme that reached 2,600,000 persons in eighteen of the twenty-six states of the Brazilian federation.59 Though limited, it was the first nation-wide attempt to broaden vaccine coverage using the existing structures, and it showed a strong presence in the country's inland and poorer areas. In 1961 the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz began production of the freeze-dried vaccine, and soon afterwards vaccine was being produced at other institutes in the south and the north-east regions of the country.60

The administrations following the Kubitschek era, namely those of Jânio Quadros (1961) and João Goulart (1961–64), were marked by great political and economic instability that culminated in a civil–military coup of 31 March 1964, which buried the democratic period that had been initiated in 1945. Authoritarian regimes lasted until 1985. Both the ephemeral Jânio Quadros administration and João Goulart's government tried to be more independent from the United States in terms of foreign policy and sought contact with the Non-Aligned Movement.61 In the health field, beginning in the 1960s, a view emerged in Brazil that was critical of the vertical and centralized models of disease control and of the bounded approach of the relation between health and development. These critics were health professionals who had found a voice inside the government and in the main professional associations. They were also engaged in nationalist projects of social reform, in particular agrarian reform, and they joined in the debates that were polarizing the country. They defended greater decentralization and integration of health activities. In this context the malaria eradication programme came in for severe criticism. There was thus no sympathy towards a new eradication campaign that would be similarly centralized and vertical, nor was there interest in having the United States again participate in the country's internal affairs.62

During the entire month of January 1962 the press announced the possibility of a smallpox epidemic in Brazil; the threat originated from Europe, where at that time there was an actual outbreak in England. Argentina had already imported vaccines against the possibility.63 The alarm was amplified by the fact that 60 per cent of Rio de Janeiro's infant population had not been immunized against the disease.64 In a way, the press revealed the actual state of Brazilian public opinion in the sense that the “menace” was seen to be an external one, even though smallpox was admitted by the government to be endemic. On the other hand, the press denounced the fact that the most important city in the country had not succeeded in protecting the majority of its infants from smallpox, despite the requirement to furnish a vaccine certificate for matriculation in schools.

At the end of January 1962 João Goulart's administration decided to initiate a National Campaign against Smallpox (Campanha Nacional Contra a Varíola). It was the first nation-wide organization created to co-ordinate the fight against the disease in almost sixty years. Several health units in the Ministry of Health and the representative of PAHO/WHO in Brazil were involved in its co-ordination.65 Between October 1962 and July 1966 the campaign vaccinated 23,500,000 persons. The coverage rates varied from 8.7 per cent in the southern states of the country to 41.9 per cent in the north-eastern states. Although the federal government had been highly involved, the execution of the campaign depended essentially on each state's administration, and each worked under different financial circumstances and epidemiological conditions. The federal human and financial resources devoted to the smallpox campaign were mostly allocated for planning, standardization and epidemiological work.66 Following the principle that a central government provides co-ordination while overseeing executive decentralization (a principle that would be important later for the eradication campaign), the federal government mobilized efforts to achieve the elimination of the disease, but did not back this up with sufficient investment.

Under the impact of this first effort there was a decrease in the number of reported smallpox cases from 9,600 with 160 deaths in 1962 to 3,623 cases and 20 deaths in 1966.67 Nevertheless, in the same period the incidence of the disease decreased faster in other countries of the region that eradicated the disease in the mid-1960s. In 1966 Brazil was the last frontier of smallpox in the Americas, and for this reason it was the target of increasing international pressure.68

Smallpox as an Eradicated Disease in Brazil

The Brazilian authorities faced immense challenges in organizing a smallpox eradication programme in the middle of the 1960s. At this time the national priority was malaria for which an eradication campaign was intensified after 1965, consuming part of the national resources and monopolizing international resources. Even though malaria eradication was actually being implemented, from the point of view of public health strategies the vertical and centralized models were being criticized in Brazil and abroad. In the specific case of smallpox there was no consensus among public health physicians and authorities about the importance of smallpox in relation to other vaccine-preventable diseases such as poliomyelitis, nor was there agreement about the risks of mass vaccination. Further, there was a long list of technical and administrative problems confronting an eradication programme: vaccine production was insufficient and based on technologies considered obsolete, and quality control was poor; there were no reference laboratories for confirmation of diagnosis; a storage and transportation network was needed; there was no national structure nor previous mass vaccination experience; the number of specialized technical personnel was small; detailed nation-wide health data was inadequate; there was no epidemiological surveillance system; and existing legislation was insufficient to compel vaccination and re-vaccination. A younger and more urban population was less familiar with smallpox than the previous generation, particularly in its more severe fatal form. Further, smallpox even in its minor variety was under-registered. The measures to be taken against the disease were, therefore, immense, and there were many scientific, technical and technological obstacles to be overcome, quite apart from the political and economic crisis that led to the collapse of democratic rule and the military coup of 31 March 1964.

Given the increasing pressure from other governments and international agencies, and also the commitments made and reconfirmed at the Pan American Conferences and World Health Assemblies, the new government of Marshal Castelo Branco (1964–67) inserted Brazil into the era of eradication. In 1965 the country adopted an exclusive malaria eradication programme, definitively leaving behind the goal of mere malaria controls. In August 1966 the Smallpox Eradication Campaign (CEV) was initiated with the sole aim of eliminating the disease from the country.69

The Minister of Health, Raimundo de Brito, elucidated the motives that led the government to eradicate smallpox. He stated that the disease deserved the government's special attention not only for its nosological aspect but also for its basically political importance, seeing that Brazil “lamentably is still inscribed among the most important smallpox foci in the world and the most relevant in the American continent”.70 The national and international contexts thus intersected. One third of the Smallpox Eradication Campaign budget came from the Alliance for Progress; effective support was also provided by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Canadian Government, PAHO and WHO.71 The USAID also allocated significant resources for mass vaccination in 1970 and 1971.72 On the Brazilian side, new investments in smallpox vaccination, the decrease in the number of cases, and the achievement of the initial goal in 1968 served as propaganda for the military regime. At the launch of the Smallpox Eradication Campaign the government called itself “revolutionary” and publicly advertised that in the past two years there had been twice as many vaccinations as during the previous administration deposed in 1964.73

Given the favourable national and international context, the “Brazilian deficit” in smallpox activity was in a short period of time converted to an advantage and opportunity for the military government and for a group of health professionals, particularly physicians, virologists and epidemiologists, who were not necessarily politically aligned with the regime. In fact many were opposed to it, but they engaged in smallpox eradication because it was said to be a national project. However, the eradication of smallpox could also be seen as a political response by Brazil to international coercion, one that would allow the military government to obtain recognition and legitimacy at a moment when it was increasing censorship of the press and repressing opposition movements. In 1968, during the government of General Costa e Silva (1967–69), Brazil was the only country in the Americas to have indigenous smallpox cases. On the other hand, the smallpox campaign enabled the country's health agenda to be extended beyond disease eradication and opened up professional and political spaces for those who involved themselves in it.

From the point of view of structure, the Smallpox Eradication Campaign grew from a previously small effort into a co-ordinated and planned programme with financial resources that had never before been invested in smallpox. Instead of creating a large structure that could become bureaucratized, as had been the case with malaria eradication, a decision was made to use personnel from other branches of the Ministry of Health, including the Malaria Eradication Campaign itself, along with various state and municipal health services, and the Special Public Health Services Foundation (Fundação Serviços Especiais de Saúde Pública), which was the base for the Smallpox Eradication Campaign leadership.74 Using existing trained personnel, resources and structures, and having the flexibility to allow the states to hire, train and dismiss staff, Brazil's smallpox campaign did not install the vertical and centralized model that it apparently represented.75 The new organization innovated to achieve in the later 1960s what the 1962 campaign could not; possessing sufficient funds and authority, it put most of its resources and infrastructure into the states and municipalities under federal co-ordination and planning.

Between 1966 and 1971, while mobilizing the resources of the federal, state and municipal services, the Smallpox Eradication programme involved a modest number of personnel considering the country's size; out of 3,563 staff members, 654 were vaccinators and 613 vehicle drivers. An important innovation involved the use of advanced technology for vaccination. The CDC had made successful experiments in two capitals in north-eastern states of the country in 1965,76 and the decision was taken to employ jet-injectors (in this case, the ped-o-jet) instead of needles in urban areas; these enabled vaccination teams to immunize more people per day and the population were less distrustful of them. However, in rural areas and in the house-to-house campaign, a multiple pressure needle technique was used. As a result of donations from PAHO/WHO, the eradication programme had 332 ped-o-jets to use during the attack phase, from February 1967 to November 1971.77 Further, 230 dedicated vehicles, mainly obtained from international sources, guaranteed the mobility of the vaccination teams. All of these resources were used to produce a total of 81,745,290 vaccinations corresponding to 84 per cent of the Brazilian population.78

The strategy adopted in urban areas (or wherever there were concentrations of people) was to mobilize the population for mass vaccination in public spaces; large crowds marked the arrival of the vaccinators and the attack phase of the campaign. Local political leaders were involved in the mobilization process and became allies of the CEV state co-ordinators. Popular festivities, processions, religious services, fairs, artistic performances, army premises, public schools, large enterprises—various places and occasions were used for mass vaccination. The teams often worked until dark in order to vaccinate all who attended. The strategy of vaccinating large numbers of people in public spaces included the training of new vaccinators, and these public demonstrations—made even more visible by the presence of the press—had a positive effect on the population and the authorities.79

Whatever strategy and method was used, it was considered vital “to obtain sufficient motivation in the community, working with the natural leaders and using means of publicizing and demonstration appropriate to the education standard of each community”.80 Mass gatherings for vaccination were announced through newspapers, loudspeakers, posters and films shown at schools. Well publicized demonstrations of vaccination were also made by political leaders, artists and sportsmen, and the participation of these famous people resulted in many members of the public coming forward voluntarily to be vaccinated.81 This innovation was the basis for the “National Immunization Days” or NIDs used later for the eradication of polio in Brazil and in other mass vaccination campaigns.

Tough laws were passed making it obligatory to show a vaccination certificate in order to access any public document, receive wages, matriculate in public schools and travel abroad, among other things. But the legal obligation does not seem to have been decisive. Thus sixty years after the Vaccine Revolt there is no record of resistance to vaccination in the 1960s and 1970s. On the contrary, popular gatherings in public spaces throughout the country mobilized the public and increased the perception that vaccination was a public good from the State. In this it differed from the malaria eradication campaign, which had never made use of any kind of mobilization or social negotiation. A further contrast is that a military regime that was largely opposed to popular participation in public spaces found itself organizing huge public gatherings for vaccination.

Between 1966 and 1971 Brazil produced 268,226,000 doses of freeze-dried smallpox vaccine.82 Among the obstacles to successful mass vaccination there was the matter of the outdated technology used in vaccine production, difficulties with the preservation of vaccine stocks and the ability to produce the huge amount of vaccine needed. Agreements with PAHO and WHO soon provided equipment and technology transfer for the modernization and increase of vaccine production, and the vaccine produced in Brazil's national laboratories was periodically tested by the Connaught Laboratories, Canada.83 Technical assistance was also given to equip diagnostic laboratories in Belém do Pará, Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.84 With the modernization and large-scale production of the smallpox vaccine, the foundation was laid for the creation in 1975 of the National Immunization Programme (Programa Nacional de Imunizações) that has subsequently sought national self-sufficiency in vaccine production based on Brazilian research as well as technology transfer.85

Another obstacle was the need to institute epidemiological surveillance. In the smallpox campaign's initial plan, surveillance procedures were to be implemented simultaneously with mass vaccination activities and then continue after the attack phase had been completed.86 However, as a result of financial and operational difficulties, an epidemiological surveillance system was not implemented until 1969, when the number of reported cases reached the highest level since the beginning of the smallpox campaign in 1966. The lack of good surveillance was reported to PAHO/WHO as a major barrier to eradication.87 After the creation of Epidemiological Surveillance Units (Unidades de Vigilância Epidemiológicas) and Reporting Posts (Postos de Notificação) at the end of the decade, the data problem began to recede. These new surveillance functions became the responsibility of each state in the consolidation phase of the campaign, reinforcing the link among different governmental spheres.88 By 1970 every state in Brazil had established an Epidemiological Surveillance Unit, and there were 6,074 Reporting Posts covering 90 per cent of Brazil's municipalities. These represented the embryo of the National Epidemiological Surveillance System (Sistema Nacional de Vigilância Epidemiológica) established formally in 1975.89

Figure 3.

Vaccination of seasonal rural workers, state of Maranhão, north-east of Brazil, 1969. (Claudio do Amaral papers, COC-Fiocruz.)

For some protagonists the success of the Brazilian programme resulted from the combination of mass vaccination, rigorous vaccination supervision and epidemiological surveillance.90 During 1970 there had been 1,795 reported smallpox cases. One year later, the last 19 Brazilian cases were reported in the city of Rio de Janeiro, some at the very moment when Marcolino Candau (Director-General of WHO) and Abraham Horowitz (Director-General of PAHO) were visiting the country to reaffirm the priority of smallpox eradication.91 In August 1973 an international commission presented to the Brazilian government the certificate of smallpox eradication.92 Compulsory vaccination continued to be a part of routine health services until 1975. Smallpox had finally become biologically invisible.

Figure 4.

Politicians, officers and public health staff at the opening of the Smallpox Eradication Campaign, city of Natal, state of Rio Grande do Norte, north-east of Brazil, 1970. (Claudio do Amaral papers, COC-Fiocruz.)

Concluding Remarks

The history of smallpox in Brazil is marked by changes in the government's perception of the disease's political and epidemiological importance vis-à-vis other endemic and epidemic diseases. After being very prominent on official agendas in the imperial and early republican eras, smallpox disappeared as a concern of the Brazilian government after 1920. This disappearance was unrelated to shifts between an authoritarian or democratic form of rule, and to whether officials were centralizing or diffusing state authority to the provinces or states. In the nineteenth century, smallpox vaccine institutes were created in several parts of the country. Yet the success of smallpox control campaigns in the first decades of the twentieth century (and the continued prevalence of smallpox in its benign form after 1940) produced perverse results. That is, in contrast to what was to happen in the cases of yellow fever, leprosy, malaria and tuberculosis, successful early smallpox control did not establish a tradition of research and development, nor did it penetrate medical schools as a relevant theme or lead to an organized community of specialists. Further, successful smallpox control in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did not result in new routines for the reporting, registering and surveillance of the disease. Until the 1950s, then, there was no difference between Brazil's republican and imperial response to smallpox: both types of government took emergency actions only in the face of epidemic outbreaks rather than organizing long-lasting systems at the federal level.

The return of smallpox to the national sanitary agenda in 1958 was associated with changes in Brazil's ties to the international health system in the context of the Cold War. President Kubitschek's proposal for more multilateral international relations, Brazil's increasing need for foreign investment, and the success of the Cuban Revolution were all part of the new reality. The United States in particular took a new interest in Latin America's regional politics at this time, and the result was felt in different spheres including regional health policies. The adoption of a global eradication programme by PAHO/WHO put strong pressure on Brazil, the only country in the Americas with endemic smallpox cases in the mid-1960s. The US also took a more active role in the financing of regional development programmes, culminating in the so-called Alliance for Progress. In 1964 a military coup brought Brazil much more closely into alignment with the United States, a situation that lasted into the 1970s and facilitated further steps towards smallpox eradication.

Thus the national and international context in the 1970s brought together three key factors: tangible benefits resulting from a political alignment with the United States, the WHO's eradication agenda for malaria and smallpox, and the Brazilian military government's need to produce good news. That said, the achievements of Brazil's smallpox eradication programme over seven years were also a result of national adaptation, innovation and the country's localized adaptation of international health policies. Young physicians and epidemiologists who participated and directed the campaign in Brazil, were called on later to play a part in the eradication programmes of other countries such as Ethiopia, Somalia, India and Bangladesh. In later years they rose to hold prominent positions in national and international health communities.

Smallpox eradication helped Brazil to launch a large National Immunization Programme and a National Epidemiological Surveillance System, with their respective state sub-systems. Undoubtedly poliomyelitis eradication in Brazil in the early 1990s was a direct consequence of structures that first emerged from smallpox eradication. These results had never been anticipated by the international and bilateral co-operation agencies nor imagined by the military leadership during the dictatorship. Yet they were important for the public health reforms that were implemented when Brazil returned to a democratic regime in 1985. The major unexpected result was the provision of free, government-supplied vaccines which led to the growth of strong demand from the public for further immunization.

Acknowledgments

This article is one of the results of research funded by the National Council of Research and Technological Development (CNPq). I am grateful to Medical History's anonymous referees and to Sanjoy Bhattacharya for their criticism and suggestions. I would like to thank Paul Greenhough for his generous detailed and careful review of my writing and for his comments. Any errors and omissions are entirely my responsibility.

Footnotes

1For example, Frank Fenner, D A Henderson, I Arita, Z Ježek and I D Ladnyi, Smallpox and its eradication, Geneva, World Health Organization, 1988; Donald A Henderson and G Miller, The history of smallpox eradication, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980; Bichat A Rodrigues, ‘Smallpox eradication in the Americas’, Bull. Pan Am. Health Organ., 1975, 9: 53–68; Carolina S Barreto, ‘Fragmentos da história da erradicação da varíola nos estados da Bahia e Sergipe’, Revista baiana de saúde pública, 2003, 27: 106–13. Few historians have written about the Brazilian smallpox eradication campaign; the exception is Tania Maria Fernandes, ‘Varíola: doença e erradicação’, in D R Nascimento and D M de Carvalho (eds), Uma história brasileira das doenças, Rio de Janeiro, Paralelo 15, 2004, pp. 211–28.

2Sanjoy Bhattacharya, Expunging variola: the control and eradication of smallpox in India, 1947–1977, New Delhi, Orient Longman, 2006; Steven Palmer, ‘Central American encounters with Rockefeller public health, 1914–1921’, in G M Joseph, C C LeGrand and R D Salvatore (eds), Close encounters of empire: writing the cultural history of U.S.–Latin American relations, Durham, NC, Duke University Press, 1998, pp. 311–32; Anne-Emanuelle Birn, ‘O nexo nacional-internacional na saúde pública: o Uruguai e a circulação das políticas e ideologias de saúde infantil, 1890–1940’, Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos, 2006, 13: 675–708; André L V Campos, ‘Politiques internationales (et réponses locales) de santé au Brésil: le Service Spécial de Santé Publique, 1942–1960’, Can. Bull. Med. Hist., 2008, 25, 111–36; Marcos Cueto, Cold war, deadly fevers: malaria eradication in Mexico, 1955–1975, Washington, DC, Woodrow Wilson Center Press, and Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

3Outbreaks of cholera were also important in the middle of the nineteenth century, while bubonic plague gained sanitary relevance in the second half of that century. See Donald B Cooper, ‘Brazil's long fight against epidemic disease, 1849–1917, with special emphasis on yellow fever’, Bull. N. Y. Acad. Med., 1975, 51: 672–96, pp. 673–5.

4Cooper, op. cit., note 3 above; Plácido Barbosa and Cassio B Rezende, Os serviços de saúde pública no Brasil, especialmente na cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1808–1907 (esboço histórico e legislativo), Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, 1909; Sidney Chalhoub, Cidade febril: cortiços e epidemias na corte imperial, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1996; Jaime L Benchimol, Pereira Passos: um Haussmann tropical. A renovação urbana da cidade do Rio de Janeiro no início do século XX, Rio de Janeiro, Prefeitura da Cidade do Rio de Janeiro, 1990.

5Lycurgo de Castro Santos Filho, História geral da medicina brasileira, 2 vols, São Paulo, Hucitec/Edusp, 1991, vol.1, pp. 270–1; Chalhoub, op. cit., note 4 above, p. 107.

6Tania M Fernandes, Vacina antivariólica: cie^ncia, técnica e o poder dos homens, 1808–1920, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Fiocruz, 1999, pp. 29–46; Chalhoub, op. cit., note 4 above.

7Fernandes, op. cit., note 6 above. Vaccination institutes were also created in the provinces of São Paulo, Rio Grande do Sul and Minas Gerais.

8Fernandes, op. cit., note 6 above; Tania M Fernandes, ‘Vacina antivariólica: seu primeiro século no Brasil (da vacina jenneriana à animal)’, Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos, 1999, 6: 29–51, p. 37; Massako Iyda, Cem anos de saúde pública: a cidadania negada, São Paulo, Editora Unesp, 1994, pp. 15–22.

9Some authors stress that the only obligation actually met was the vaccination of the African slaves that worked on farms; this was due to the demand from land- and slave-owners. See Fernandes, op. cit., note 8 above. Other authors also suggest that the main targets of vaccination were the newly arrived African slaves about to be sold. Chalhoub, op. cit., note 4 above; Mary C Karasch, A vida dos escravos no Rio de Janeiro (1808–1850), São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 2000, pp. 214–16. There are suggestions that outbreaks in the 1830s and 1840s coincided with the years when high numbers of slaves arrived in Brazil from Africa. Karasch, op. cit.; Dauril Alden and Joseph C Miller, ‘Out of Africa: the slave trade and the transmission of smallpox to Brazil, 1560–1831’, J. Interdiscip. Hist., 1987, 18: 195–224.

10Santos Filho, op. cit., note 5 above, in vol. 2.

11Tania M Fernandes, ‘Imunização antivariólica no século XIX no Brasil: inoculação, variolização, vacina e revacinação’, Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos, 2003, 10: 461–74, suppl. 2; idem, ‘Vacina antivariólica: visões da Academia de Medicina no Brasil imperial’, Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos, 2004, 11: 141–63, suppl. 1.

12Barbosa and Rezende, op. cit., note 4 above; Galdino do Valle, ‘Leis orgânicas de hygiene e saúde pública’, in Livro do centenário da Câmara dos Deputados, 2 vols, Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa do Brasil, 1926, vol. 1, pp. 497–518.

13Records from 1873 show 697 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants; by 1878 deaths had reached 783 per 100,000. ‘Varíola – Trabalho para a Comissão Internacional de Certificação, 1973’, box 51, fol. 3, Cláudio do Amaral papers, Casa de Oswaldo Cruz-Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (hereafter COC-Fiocruz), Rio de Janeiro, table I, p. 2. This is the best source for data relating to the history of smallpox cases and mortality.

14Ibid. Deaths rose to the impressive number of 874 per 100,000 inhabitants in the city. For the so-called “First Republic” (1889–1930), the available information about vaccination, smallpox cases and mortality relates almost exclusively to Rio de Janeiro city.

15Fernandes, op. cit., note 6 above, pp. 40–54; Fernandes, op. cit., note 8 above, pp. 42–6.

16Benchimol, op. cit., note 4 above; Jaime L Benchimol (ed.), Manguinhos do sonho à vida: a cie^ncia na belle époque, Rio de Janeiro, Casa de Oswaldo Cruz-Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, 1990, pp. 22–6; Teresa A Meade, “Civilizing” Rio: reform and resistance in a Brazilian city, 1889–1930, University Park, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997, pp. 75–101.

17For further information about Oswaldo Cruz, see Nara Britto, Oswaldo Cruz: a construção de um mito na cie^ncia brasileira, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Fiocruz, 1995; Gilberto Hochman and Nara Azevedo, ‘Oswaldo G. Cruz', in W F Bynum and H Bynum (eds), Dictionary of medical biography, 5 vols, Wesport, CT, Greenwood Press, 2007, vol. 4, pp. 378–80; Benchimol, op. cit., note 16 above; Jaime L Benchimol, Febre amarela: a doença e a vacina, uma história inacabada, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Fiocruz, 2001, pp. 41–68; Fernandes, op. cit., note 6, pp. 47–82.

18Britto, op. cit., note 17 above; Benchimol, op. cit., note 16 above; Benchimol, op. cit., note 17 above; Jaime L Benchimol and Luiz Antonio Teixeira, Cobras, lagartos & outros bichos: uma história comparada dos institutos Oswaldo Cruz e Butantan, Rio de Janeiro, Editora UFRJ, 1993; Nancy L Stepan, Beginnings of Brazilian science: Oswaldo Cruz, medical research and policy, 1890–1920, New York, Science History Publications, 1976. Oswaldo Cruz directed the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz until his death in 1917; his successor was Carlos Chagas, who discovered American trypanosomiasis or Chagas disease.

19Benchimol, op. cit., note 16 above; Chalhoub, op. cit., note 4 above, ch. 3; Fernandes, op. cit., note 6 above, pp. 54–71; Meade, op. cit., note 16 above; José Murilo de Carvalho, Os bestializados: o Rio de Janeiro e a república que não foi, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1987.

20On the revolt, see the references in Benchimol, op. cit., note 4 above; Carvalho, op. cit., note 19 above; Chalhoub, op. cit., note 4 above, ch. 3; Meade, op. cit., note 16 above; Teresa A Meade, ‘“Civilizing Rio de Janeiro”: the public health campaign and the riot of 1904’, J. Soc. Hist., 1986, 20: 301–22; Nilson do Rosário Costa, Lutas urbanas e controle sanitário: origens das políticas de saúde no Brasil, Petrópolis, Vozes/Associação Brasileira de Pós-Graduação em Saúde Coletiva, 1985; Jeffrey D Needell, ‘The Revolta contra vacina of 1904: the revolt against “modernization” in belle-epoque Rio de Janeiro’, Hisp. Am. Hist. Rev., 1987, 67: 233–69; Nicolau Sevcenko, A revolta da vacina: mentes insanas em corpos rebeldes, rev. ed., São Paulo, Brasil, Scipione, 1993.

21This argument is developed in Chalhoub, op. cit., note 4 above, pp. 134–51.

22Carvalho, op. cit., note 19 above, pp. 95–113.

23‘Varíola – Trabalho para a Comissão Internacional de Certificação, 1973’, op. cit., note 13 above, pp. 3–4.

24Ibid.; Achilles Scorzelli Jr, ‘A importância da varíola no Brasil, 1964’, Arquivos de Higiene, 1965, 21: 3–64, p. 17.

25Barbosa and Rezende, op. cit., note 4, pp. 890–901; Meade, op. cit., note 16 above, pp. 112–13; Dinis Almáquio, O estado, o direito e a saúde pública, Rio de Janeiro, n.p., 1929, pp. 9, 16.

26The State Superior Court revoked the decision. A Noite, 21 Jan. 1926, in ‘Livro de recortes de jornais’ (Newspapers clipping book), Carlos Chagas papers, COC-Fiocruz.

27‘Varíola – Trabalho para a Comissão Internacional de Certificação, 1973’, op. cit., note 13 above, p. 4.

28Luiz Antônio de Castro Santos, ‘O pensamento sanitarista na primeira república: uma ideologia de construção da nacionalidade’, Dados-Revista de Cie^ncias Sociais, 1985, 28: 237–50; Gilberto Hochman, A era do saneamento: as bases da política de saúde pública no Brasil, São Paulo, Hucitec-Anpocs, 1998, ch. 2; Nísia Trindade Lima, Um sertão chamado Brasil: intelectuais e representação geográfica da identidade nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Revan-Iuperj, 1999, ch. 4.

29Benchimol, op. cit., note 17 above; John Farley, To cast out disease: a history of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation (1913–1951), Oxford University Press, 2004; Ilana Löwy, Vírus, mosquitos e modernidade: a febre amarela no Brasil entre cie^ncia e política, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Fiocruz, 2006.

30Hochman, op. cit., note 28 above, ch. 3.

31Gilberto Hochman and Cristina O Fonseca, ‘O que há de novo? Políticas de saúde pública e previde^ncia, 1937–45’, in D Pandolfi (ed.), Repensando o Estado Novo, Rio de Janeiro, Editora FGV, 1999, pp. 73–93.

32Gilberto Hochman, ‘Cambio político y reformas de la salud pública en Brasil. El primer gobierno Vargas (1930–1945)’, Dynamis, 2005, 25: 199–226.

33João Baptista Risi Júnior, ‘A produção de vacinas é estratégica para o Brasil: entrevista com João Baptista Risi Júnior', Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos, 2003, 10: 771–83, suppl 2.

34On vaccine production during Getúlio Vargas's government, see Benchimol, op. cit., note 17 above; Dilene R do Nascimento, Fundação Ataulfo de Paiva – Liga Brasileira contra a Tuberculose, um século de luta, Rio de Janeiro, Quadratim-Faperj, 2002, pp. 89–106.

35‘Anais da I Confere^ncia Nacional de Saúde’, GC 36.05.26, Gustavo Capanema papers, Centro de Pesquisa e Documentação em História Contemporânea do Brasil/Fundação Getúlio Vargas. For analysis of the conference, see Gilberto Hochman and Cristina O Fonseca, ‘A I Confere^ncia Nacional de Saúde: reformas, políticas e saúde pública em debate no Estado Novo’, in Angela M C Gomes (ed.), Capanema: o ministro e seu ministério, Editora FGV, 2000, pp. 173–93.

36About the eradication of the Anopheles gambiae in Brazil, see Randall Packard and Paulo Gadelha, ‘A land filled with mosquitos: Fred L. Soper, the Rockefeller Foundation and the Anopheles gambiae invasion of Brazil’, Parassitologia, 1994, 36: 197–213; Farley, op. cit., note 29 above, pp. 138–41.

37At the same time other national services were created to combat diseases considered then as priorities: yellow fever, tuberculosis, leprosy, bubonic plague, mental diseases and cancer.

38Hélbio Fernandes Moraes, SUCAM: sua origem, sua história, 2 vols, Brasília, Ministério da Saúde, 1990.

39For SESP, see Campos, op. cit., note 2 above; Nilo C B Bastos, SESP/FSESP: evolução histórica, 1942–1991, 2nd ed., Brasília, Ministério da Saúde, Fundação Nacional de Saúde, 1996. SESP remained autonomous in its important preventative actions and basic health services until the 1970s and participated in the smallpox eradication campaign between 1966 and 1973.

40The new department was authorized to combat what were called “rural endemic diseases”: malaria, leishmaniasis, Chagas disease, plague, brucellosis, yellow fever, schistosomiasis, ancylostomiasis, hydatiosis, goitre, buboes and trachoma. Smallpox was never included in this category.

41Regarding Kubitschek's developmentist project and term, see Angela M C Gomes (ed.), O Brasil de JK, 2nd ed., Rio de Janeiro, Editora da FGV, 2002; Celso Lafer, JK e o programa de metas (1956–61): processo de planejamento e sistema político no Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Editora FGV, 2002. For Brazilian programmes for the control and eradication of malaria, see Gilberto Hochman, ‘From autonomy to partial alignment: national malaria programmes in the time of global eradication, Brazil, 1941–61’, Can. Bull. Med. Hist., 2008, 25: 201–32.

42Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira, Mensagem ao Congresso Nacional remetida pelo Presidente da República por ocasião da abertura da sessão legislativa de 1956, Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, 1956, pp. 185–6.

43The idea of bounded approach is taken from Randall M Packard and Peter J Brown, ‘Rethinking health, development, and malaria: historicizing a cultural model in international health’, Med. Anthropol., 1997, 17: 181–94.

44“A nosso favor está a coincide^ncia de que, exatamente para muitas destas enfermidades que mais afligem as populações dos países subdesenvolvidos, novas descobertas da terape^utica e da profilaxia tenham tornado o seu combate, e consequ¨entemente sua grande redução, ou mesmo eliminação, independente dos problemas de desenvolvimento econômico e de aparelhamento médico-sanitário de custo elevado.” Brasil. Kubitschek de Oliveira, op. cit., note 42 above, p. 187.

45AID/United States AID Mission to Brazil, ‘Audit report of Malaria Eradication under Project Agreement n.512-11-510-014 for the period 1 Nov. 1960 through 30 Sep. 1964’, Rio de Janeiro, 9 Dec. 1964, (http://dec.usaid.gov/); Enrique Villalobos, et al., ‘Evaluation of the malaria eradication programme in Brazil', USAID, 1964; Eugene P Campbell, ‘The role of the International Cooperation Administration in international health’, Arch. Environ. Health, 1960, 1: 502–11.

46Kelley Lee, ‘Intensified smallpox eradication program’, in K Lee, Historical dictionary of the World Health Organization, Lanham, MD, Scarecrow Press, 1998, pp. 131–2; Rodrigues, op. cit., note 1 above.

47Juscelino Kubitschek de Oliveira, Mensagem ao Congresso Nacional remetida pelo Presidente da República por ocasião da abertura da sessão legislativa de 1958. Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, 1958, p. 274.

48Ibid., p. 272.

49Rodrigues, op. cit., note 1 above, p. 55; Scorzelli Jr, op. cit., note 24 above, p. 15; ‘Topic 23: Status of smallpox eradication in the Americas’, XV Pan American Sanitary Conference, San Juan, Puerto Rico, Pan American Sanitary Organisation, 1958, CSP15/17 (Eng.), Cláudio do Amaral papers, COC-Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro.

50Rodrigues, op. cit., note 1 above, p. 55; Fenner, et al., op. cit., note 1 above, pp. 593–603.

51Kubitschek de Oliveira, op. cit., note 47 above.

52Alexandra de Mello Silva, ‘Desenvolvimento e multilateralismo: um estudo sobre a Operação Pan-Americana no contexto da política externa de JK’, Contexto Internacional, 1992, 14: 209–39.

53Ibid.; Paulo F Vizentini, Relações exteriores do Brasil (1945–1964): o nacionalismo e a política externa independente, Petrópolis, Vozes, 2004.

54On the ‘Discurso sobre a Operação Pan-Americana’, of 20 June 1958, see Silva, op. cit., note 52 above; ‘Operation Pan America’, in Larman C Wilson and David W Dent, Historical dictionary of Inter-American organizations, Lanham, MD, Scarecrow Press, 1998, p. 131.

55Silva, op. cit., note 52 above.

56Vizentini, op. cit., note 53 above; ‘Alliance for Progress’, in Wilson and Dent, op. cit., note 54 above, pp. 27–9.

57See ‘Información general – Reunión de Punta del Este, Uruguay’, Bol. Oficina Sanit. Panam., 1961, 51: 473–93.

58Socrates Litsios, The tomorrow of malaria, rev. ed., Karori, NZ, Pacific Press, 1997; José A Nájera, ‘Malaria control: achievements, problems and strategies’, Parassitologia, 2001, 43:1–89; Javed Siddiqi, World health and world politics: the World Health Organization and the UN system, Columbia, SC, University of South Carolina Press, 1995, pp. 141–5.

59‘Anuário estatístico do Brasil 1961’, Rio de Janeiro, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 22, 1961, table IIIB3a (CD-ROM Estatísticas do Século XX, IBGE, 2003); ‘Anuário Estatístico do Brasil 1964’, Rio de Janeiro Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 25, 1964, table IIB3 (CD-ROM Estatísticas do Século XX, IBGE, 2003).

60Benchimol, op. cit., note 17 above, pp. 310–19.

61Vizentini, op. cit., note 53 above; Leticia Pinheiro, Política externa brasileira (1889–2002), Rio de Janeiro, Jorge Zahar, 2004, pp. 33–6.

62The rise of this group was aborted by the fall of democracy; many of them were accused of being communists and were persecuted by the military regime. Maria Eliana Labra, ‘1955–1964: o sanitarismo desenvolvimentista’, in S Fleury Teixeira (ed.), Antecedentes da reforma sanitária, Rio de Janeiro, Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública-Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, 1988, pp. 9–36; Nísia Trindade Lima, Cristina O Fonseca and Gilberto Hochman, ‘A saúde na construção do estado nacional no Brasil: a reforma sanitária em perspectiva histórica’, in N T Lima, S Gerschman, F C Edler and J M Suárez, Saúde e democracia: história e perspectivas do SUS, Rio de Janeiro, Editora Fiocruz, 2005, pp. 27–58, on pp. 54–5.

63For example, the news was published in Jornal do Brasil, 18 Jan. 1962, p. 3; O Correio da Manhã, 24 Jan. 1962, p. 2.

64See O Estado de São Paulo, 16 Jan. 1962, p. 4. After the transfer of the capital from Rio de Janeiro to Brasília, the latter became the new city‐state of Guanabara. Although no longer the seat of the national government, many federal organizations and public services remained in Rio until the 1970s, and during this transition period it continued to be one of the country's most important cities and the main point of departure from the country and entry from abroad.

65Bastos, op. cit., note 39 above, pp. 270–1.

66‘Plano de operação para o Programa de Erradicação da Varíola no Brasil’, c.1966, Box 20, fol. 20, Cláudio do Amaral papers, COC-Fiocruz, tables 1 and 2, pp.13–16; ‘Varíola – Trabalho para a Comissão Internacional de Certificação, 1973’, op. cit., note 13 above, pp. 5–7; Risi Júnior, op. cit., note 33 above, p. 774.

67In retrospect, the main actors involved in the post-1966 eradication campaign are strongly critical of the 1962–66 campaign, including the alleged decrease in the number of cases. In their evaluation, the confusion about numbers was a result of the unreliable registration system. Another drawback was that critical problems such as the production of vaccine in sufficient amounts and of proper quality had not been resolved. The newspaper O Correio da Manhã of 27 Jan. 1962, stated that the campaign would have to wait until the Oswaldo Cruz Institute had sufficient freeze-dried vaccine in stock, p. 2.

68Rodrigues, op. cit., note 1 above; Donald A Henderson, ‘Smallpox eradication—the final battle’, J. Clin. Path., 1975, 28: 843–9, p. 845, fig. 1.

69Presidential Decree n.59153, 31 Aug. 1966, regulated the Smallpox Eradication Campaign (CEV). By the Presidential Decree n.61376, 18 Sep. 1967, CEV became directly subordinated to the Ministry of Health.

70“… lamentavelmente ainda se inscreve entre os mais importantes focos de varíola do mundo e o mais relevante do continente americano.” The Minister's explanations and declarations were published in daily newspapers in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo: O Correio da Manhã, 27 Aug. 1966, p. 11, and 31 Aug. 1966, p. 7; Folha de São Paulo, 27 Aug. 1966, p.7; O Globo, 27 Aug. 1966, p. 3, and 30 Aug. 1966, p. 9; O Estado de São Paulo, 31 Aug. 1966, p. 6.

71See O Globo, 27 Aug. 1966, p. 3.

72In 1970 USAID financed 30 per cent of the total budget for the programme, and in 1971 75 per cent. ‘Varíola – Trabalho para a Comissão Internacional de Certificação, 1973’, op. cit., note 13 above, Quadro XXII, p. 44.

73O Globo, 27 Aug. 1966, p. 3; O Correio da Manhã, 27 Aug. 1966, p. 11.

74For example, Oswaldo José da Silva, first director of the eradication programme, and his successor Cláudio do Amaral Jr. The SESP Foundation (FSESP), created by the Brazil-United States agreements in 1942 (see note 39) remained as an autonomous department within the Ministry of Health with rigorous training standards and higher wages than the other departments in the Ministry. Da Silva also had worked with Fred Soper in the eradication of the mosquito A. Gambiae. Other FSESP physicians had outstanding leadership roles in the campaign in the states, such as João Batista Risi Jr, coordinator of eradication in the city of Rio de Janeiro. Marcolino Candau, then OMS General Director, began at SESP and was its Director in the period 1947–50. Bastos, op. cit., note 39 above; Risi Júnior., op. cit., note 33 above; Márcio M Andrade, ‘Proposta para um resgate historiográfico: as fontes do SESP/FSESP no estudo das campanhas de imunização no Brasil’, Hist. Cienc. Saude-Manguinhos, 2003, 10: 843–8. suppl. 2.

75On the strategy of vaccination and surveillance teams creation, see ‘Plano de operação para o Programa de Erradicação da Varíola no Brasil’, c.1966, op. cit., note 66 above.

76Tests described by Ricardo Veronesi, L F Gomes, M A Soares and A Correa, ‘Importância de “jet-injector” (injeção sem agulha) em planos de imunização em massa no Brasil: resultados com as vacinas antitetanica e antivariólica’, Ver. Hosp. Clin. Fac. Med. Sao Paulo, 1966, 2: 92–5; J D Millar, T M Mack, A A Medeiros, L Morris and W Dyal, ‘Relatório à Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde sobre o emprego da injetora a pressão na Campanha Nacional Contra a Varíola’, Arquivos de Higiene, 1965, 21: 65–140; J D Millar, L Morris, A Macedo Filho, T M Mack, W Dyal and A A Medeiros, ‘The introduction of jet injection mass vaccination into the national smallpox eradication program of Brazil’, Trop. Geogr. Med., 1971, 23: 89–101.

77The eradication programmes were divided into four phases: preparatory, attack, consolidation, and surveillance and maintenance. ‘Varíola – Trabalho para a Comissão Internacional de Certificação, 1973’, op. cit., note 13 above.

78Ibid., pp. 12–71.

79This strategy was deliberate and made explicit in ‘Plano de operação para o Programa de Erradicação da Varíola no Brasil’, c.1966, op. cit., note 66 above, pp. 7–9, and appears in the ‘Manual do Vacinador’(Vaccinator Guide), Box 50, fol. 15, Cláudio do Amaral papers, COC-Fiocruz.

80“… obter suficiente motivação da comunidade, trabalhando seus líderes naturais e utilizando meios de divulgação e demonstração adequados ao nível educacional das referidas comunidades.” ‘Plano de operação para o Programa de Erradicação da Varíola no Brasil’, c. 1966, op. cit., note 66 above, p. 22.